-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Leonardo E Lopes, Luiz P Gonzaga, Marcos Rodrigues, José Maria C da Silva, Distinct taxonomic practices impact patterns of bird endemism in the South American Cerrado savannas, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 203, Issue 1, January 2025, zlae019, https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlae019

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Identifying endemic species and the areas of endemism delimited by them is central to biogeography. However, the impact of distinct taxonomic approaches on these patterns is often neglected. We investigated how three different taxonomic approaches impact the patterns of bird endemism in the Cerrado. The first two approaches (at species and subspecies levels) were based on traditional taxonomy based on the biological species concept. The third approach was based on a revised alternative taxonomy that sought to identify evolutionarily significant units (ESUs). In this third approach, after identifying the endemic taxa using traditional taxonomy, we revised their validity, removing biologically meaningless entities. We then detected the areas of endemism delimited by these endemic taxa under the three taxonomic approaches. We found that traditional taxonomy at the species level underestimated bird endemism by ignoring some ESUs that were considered subspecies. In contrast, traditional taxonomy at the subspecies level overestimated bird endemism, leading to the recognition of spurious areas of endemism because several of the purported endemic subspecies were taxonomic artefacts. The revised taxonomy provided a more refined picture of patterns of avian endemism in the Cerrado, suggesting that the use of ESUs improves the results of biogeographical analysis.

Introduction

Identifying areas of endemism, the fundamental units in biogeography (Hausdorf 2002), is the first step towards understanding the historical or current factors that explain modern patterns of speciation and range restriction (Slatyer et al. 2007). Different biological groups living in the same biogeographical region usually exhibit distinct patterns of endemism owing to differences in their traits, habitat preferences, and evolutionary histories (Kessler et al. 2001, González-Orozco et al. 2015). However, taxonomists dealing with those groups generally follow different taxonomic practices (Winston 1999), which, in turn, can also affect endemicity patterns.

In biogeographical analyses, species are the most basic taxonomic units, but they are identified and delimited differently across major biological groups (Stankowski and Ravinet 2021). For example, the number of polytypic species (i.e. composed of two or more subspecies) relative to the total number of species varies substantially between biological groups, with much higher rates among vertebrates than invertebrates (Vinarski 2015). Consequently, in highly polytypic biological groups, any biogeographical analyses conducted at the species level can potentially lose significant taxonomic resolution (O’Hara 1993) because many ‘evolutionarily significant units’ (ESUs) (Moritz 1994) treated as subspecies would not be included in the analyses.

The impact of ignoring important ESUs in biogeographical analyses might be particularly detrimental in ornithology, where the biological species concept (BSC) (Mayr 1963, Johnson et al. 1999) has been highly influential since the first half of the 20th century (Haffer 1992). From 1910 to 1960, for instance, the number of recognized bird species dropped from ~19 000 monotypic species to ~9000 polytypic species (Mayr 1969). The logical result was that the wide use of polytypic species ended up underestimating the number of ESUs in birds (Milá et al. 2012). For example, a recent estimate of avian evolutionary diversity suggested that there are currently ~18 000 ESUs (‘phylogenetic species’) of birds (Barrowclough et al. 2016), which represents a surplus of 62% in the number of currently recognized bird species (Gill et al. 2023).

In contrast, bird subspecies, as currently recognized, are often not ESUs (Burbrink et al. 2022) and, therefore, cannot be used to improve the taxonomic resolution of biogeographical studies (Zink 2004). That is probably why ‘trinomial nomenclature survives primarily as a tool of convenience that cannot be viewed as strict science and should not be called on to establish or resolve crucial policy issues such as endangered species listings’ (Fitzpatrick 2010). This is because most bird subspecies have been described in a pre-statistical era, often from small samples and with limited geographical coverage, never receiving modern, quantitative scrutiny (Haig and Winker 2010, Remsen 2010). Consequently, many of the ~20 000 bird subspecies currently recognized (Gill et al. 2023) represent arbitrary subdivisions of cline or hybrid populations (Zink 2004, Aleixo 2007, Barrowclough et al. 2016).

In recent years, new technologies have led to frequent changes in bird taxonomy owing to rearrangements of entire genera, families, and even orders, accompanied by repeated nomenclatural changes (David and Gosselin 2011, Burns et al. 2016). However, this apparent taxonomic dynamism is misleading because even the most up-to-date taxonomic bird databases (e.g. Clements et al. 2022, Gill et al. 2023, Remsen et al. 2023), as discussed above, still rely primarily on the subspecific arrangements presented decades ago by Peters et al. (1931–1987) and, for the Neotropical region, also by Hellmayr et al. (1918–1949) and Zimmer (1931–1953). Therefore, it is unsurprising that few studies that used revised alternative taxonomic arrangements have identified patterns of bird endemism that differ from those using the traditional taxonomy (Peterson and Navarro-Singüenza 1999, Peterson 2006). Such differences, in turn, can impact biogeographical interpretations and conservation planning (Clements et al. 2008, Huang et al. 2016).

In this paper, we describe how different taxonomic traditions and practices for identifying ESUs in birds can impact the recognition of patterns of endemism in the Cerrado, which is the largest and most biodiverse tropical savanna in the world (Oliveira and Marquis 2002, Silva and Bates 2002). We hypothesized that using the traditionally recognized biological species and subspecies as taxonomic units in biogeographical analyses can underestimate and overestimate, respectively, regional endemism levels and affect the number and location of areas of endemism. For that, we adopted the following approach: (i) we used different sources to organize a list of endemic birds of the Cerrado that recognizes both species and subspecies using a traditional taxonomic arrangement; (ii) we conducted detailed taxonomic revisions to identify ESUs endemic to the Cerrado using an alternative taxonomy; (iii) we detected and mapped the areas of endemism for birds in the Cerrado using these distinct taxonomic approaches; and (iv) we discussed the implications of our findings for future biogeographical studies and conservation efforts.

Materials and methods

Study area

The Cerrado is a biogeographical region mainly distributed across central Brazil, with minor extensions into eastern Bolivia and Paraguay (Silva and Bates 2002, Klink and Machado 2005, Villarroel et al. 2016). It harbours several vegetation physiognomies, ranging from pure grasslands to evergreen forests (Walter 2006), but savanna-like vegetation dominates the landscape (Walter et al. 2008). Although the intensive economic exploration of the Cerrado dates back only ~70 years, when modern agricultural techniques and road systems were developed (Ratter et al. 1997, Klink and Machado 2005), ~50% of its original vegetation has already been lost, with only 8.3% of its area protected in reserves (Françoso et al. 2015, Vieira et al. 2022).

In this paper, we determined the geographical limits of the Cerrado by combining the maps proposed by IBGE (2019) for Brazil and the one presented by Dinerstein et al. (2017) for Bolivia and Paraguay. Consequently, the limits of the Cerrado adopted here (Fig. 1) include part of the ‘Campo Rupestre’, a montane fire-prone vegetation type restricted to above 900 m of elevation on shallow and nutrient-poor sandy soils with rocky outcrops (Giulietti et al. 1997, Silveira et al. 2016). The Campo Rupestre is composed of an herbaceous stratum interspersed with evergreen shrubs and subshrubs, harbouring many endemic plant species (Giulietti et al. 1997, Silveira et al. 2016). Previous authors have highlighted the distinctiveness of the Campo Rupestre, considering it a biogeographical region independent from the Cerrado (Vasconcelos 2011, Colli‐Silva et al. 2019). However, given the open nature and patchy distribution of the Campo Rupestre within a matrix dominated by other vegetation types, we preferred to include part of it in the Cerrado (Ribeiro and Walter 2008).

Major blocks of tropical savanna found in South America. These blocks are delimited by their geographical position and floristic and abiotic features (Gottsberger and Silberbauer-Gottsberger 2006, Ratter et al. 2006, Dinerstein et al. 2017, Borghetti et al. 2019).

Identifying and mapping species and subspecies potentially endemic to the Cerrado

To identify and map the bird species and subspecies potentially endemic to the Cerrado, we followed a series of steps summarized in the flowchart represented in the Supporting Information (Supporting Information, Fig. S1). We first reviewed the literature and listed all taxonomic units (species or subspecies) considered endemic to the Cerrado by previous authors using the traditional taxonomy based on the BSC. In addition, we also inspected the range maps and textual range descriptions (del Hoyo et al. 1992–2012, Dickinson 2003, Clements 2007, Ridgely and Tudor 2009) of all bird taxa ever recorded in the Cerrado (Silva 1995b, Silva and Santos 2005) to identify overlooked endemic species and subspecies. Next, we checked the range of every species or subspecies, consulting general catalogues (Hellmayr et al. 1918–1949, Pinto 1938, 1944, 1964, 1978), and excluded those taxa with ranges extending considerably into other biogeographical regions.

To map the range of the taxa that remained after this initial filtering process, we used data from four sources: (i) unpublished field observations gathered by L.E.L. during 20 years of ornithological exploration of the Cerrado; (ii) records collected during an exhaustive literature review, which had as starting point the bibliographic compilations of the ornithological literature for Brazil (Oniki and Willis 2002), Paraguay (Hayes 1995), and Bolivia (Remsen and Traylor 1989), in addition to research on two online searching engines (Google Scholar and Web of Science), using as keywords the current scientific names of the target species and their junior synonyms; (iii) specimens of ornithological collections: 11 of them in Brazil (Fundação Museu de Ornitologia, Goiânia; Museu de Biologia Professor Mello Leitão, Santa Teresa; Museu de Ciências Naturais da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte; Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo; Museu de Zoologia José Hidasi, Porto Nacional; Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro; Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém; Reserva Ecológica do IBGE, Brasília; Coleção Ornitológica Marcelo Bagno da Universidade de Brasília, Brasília; Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá; and Centro de Coleções Taxonômicas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte), 6 in North America (Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Philadelphia; American Museum of Natural History, New York; Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh; Field Museum, Chicago; Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science, Baton Rouge; and National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC), and 7 in Europe (Natural History Museum, Tring, UK; Muséum National D’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France; Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Austria; Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet Stockholm, Sweden; Senckenberg Naturmuseum, Frankfurt, Germany; Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany; and Zoologische Staatssammlungen Museum, Munich, Germany) [in some of these collections, owing to time constraints, it was not possible to examine records of all available specimens, especially subspecies]; and (iv) records obtained from two online databases of biological collections, namely: VertNet (http://vertnet.org) and SpeciesLink (http://splink.cria.org.br). All these records were georeferenced using three sources: (i) ornithological gazetteers (Paynter 1989, 1992, Paynter and Traylor 1991, Vanzolini 1992); (ii) Google Earth (http://earth.google.com); and (iii) Global Gazetteer (http://www.fallingrain.com/world).

We did not use data from some biodiversity and citizen science platforms in this study, such as GBIF (https://www.gbif.org), eBird (https://ebird.org), and WikiAves (https://www.wikiaves.com). Although these databases contain a vast amount of useful data, we did not consider them suitable for this study for several reasons. Firstly, identification mistakes of ‘unvouchered’ records (see Daru and Rodriguez 2023) were common, especially in eBird. Secondly, precise geographical coordinates of records were often not available, especially in WikiAves. Thirdly, the non-citizen science data provided by GBIF are highly redundant to the data we collected directly from museum specimens. Lastly, records from these databases were mostly at the species level, which made it difficult to compare the taxonomic approaches adopted here at different resolutions.

Defining criteria to recognize birds endemic to the Cerrado

A set of criteria was required to confirm that the species and subspecies identified in the first coarse filtering were endemic to the Cerrado. The main reason is that recognizing endemism at the regional level can sometimes be controversial owing to a lack of consensus on the boundaries of the region or criteria for identifying an endemic taxon. In the Cerrado, there are three main challenges. Firstly, Cerrado maps are rough at the local level (Lopes 2008), and small patches of disjunct Cerrado in adjacent biogeographical regions are often inadequately mapped (Ratter 1982, Ribeiro et al. 2009, Mereles 2013, Marques et al. 2020). Therefore, there are controversies about whether taxa occurring in these disjunct patches should be considered endemic to the Cerrado. Secondly, boundaries between neighbouring biogeographical regions everywhere are not sharp. Instead, complex transitions and interdigitations between them usually exist, providing suitable habitats for endemic species. In the Cerrado, for instance, the transitional belt separating it from neighbouring biogeographical regions can reach up to 200 km (Eiten 1972, Ackerly et al. 1989, Marques et al. 2020). Thirdly, endemic taxa can dwell in adjacent biogeographical regions. For example, Silva (1996) demonstrated that the distributions of many Amazonian and Atlantic Forest birds extend considerably into the gallery forests of the Cerrado, some of them for >500 km. Likewise, the opposite is true for some Cerrado species, which extend their ranges dozens of kilometres within adjacent biogeographical regions. Some of these marginal populations can eventually be maintained by high immigration rates from high-quality habitats found in the core of the species distribution (Pinho et al. 2016) in a source–sink population structure (Kawecki 2008).

Given these challenges, we established two clear-cut criteria that a taxon must meet to be considered endemic to the Cerrado. Firstly, ≥90% of the taxon geographical range should fall within the limits of the Cerrado. This threshold is based on previous studies about regional endemism (Médail and Baumel 2018, Lima et al. 2020). Secondly, the few occurrences into adjacent biogeographical regions (which should represent <10% of the range of the species) ought to fall within a buffer of 100 km around the limits of the Cerrado. This value is based on the mean width of the transition zones between the Cerrado and adjacent biogeographical regions (Eiten 1972, Ackerly et al. 1989).

To measure the degree of overlap between the range of a taxon and the Cerrado biogeographical region, we created a grid of 0.25° × 0.25° cells (~27 km × 27 km) in QGIS (QGIS Development Team 2021) and overlayed it with the Cerrado map. To check whether a given taxon range met the first criterion established here, we used the ‘Join attributes by location’ tool in QGIS to estimate the proportion of cells with occurrences that fell within the limits of the Cerrado. To check whether the second criterion was met, we inspected the maps visually to see whether any record fell beyond the 100 km buffer around the limits of the Cerrado. We then used the ‘Measure line’ tool in QGIS to measure manually how far each taxon extended its range into other biogeographical regions.

Detecting areas of endemism

Some endemic taxa are widespread within a biogeographical region. They are the ones that can be used to set apart large biogeographical regions, such as the Cerrado. However, areas of endemism are nested systems, with less inclusive areas fitting within a more inclusive one (Crother and Murray 2011). Thus, if some endemic taxa occupy only part of the region and their ranges overlap, it would be possible to identify the smallest areas of endemism within large biogeographical regions. Therefore, we considered an area of endemism as an area of non-random distributional congruence among two or more taxa, which requires extensive sympatry but not complete agreement in range (Morrone 1994). To detect areas of endemism, we used the geographical interpolation of endemism analysis, a method based on the overlap between the distribution of those species of interest through a kernel interpolation of the centroids of their distributions and the areas of their ranges (Oliveira et al. 2015). This analysis was conducted in ArcGIS v.10.6 (ESRI 2017) using the toolbox ‘GIE’ developed by Oliveira et al. (2015).

Taxonomic approaches

To compare how different taxonomic approaches influence the number of endemic taxa in the Cerrado and the location of areas of endemism within this large region, we organized all species and subspecies considered endemic to the Cerrado into three groups of taxonomic units: (i) species as traditionally recognized under the BSC; (ii) subspecies as traditionally recognized under the BSC; and (iii) species as recognized in our revised alternative taxonomy. For that, we recognized only monotypic species under the general lineage concept of species (GLCS) (de Queiroz 1998). According to the GLCS, biological properties, such as intrinsic reproductive isolation and reciprocal monophyly, are only operational criteria to apply the concept in practice, not being requirements to delimit species (de Queiroz 1999, 2007, Aleixo 2023). We recognized only monotypic species because we share the view that, according to the GLCS, ‘subspecies are incompletely separated lineages within a more inclusive lineage’ and should not be given a taxonomic rank (de Queiroz 2020).

We used the checklist of Dickinson (2003) as a taxonomic reference to identify the taxa endemic to the Cerrado using traditional taxonomy at the species level (BSC-species) and the subspecies level (BSC-subspecies). This checklist relies on the BSC and encompasses all species and subspecies of the world as traditionally recognized. To identify the monotypic species endemic to the Cerrado using a revised alternative taxonomy, L.E.L. carried out detailed taxonomic revisions based on plumage and morphometric features of museum specimens. To this end, almost 3000 museum specimens were examined to assess plumage colour, patterns, and morphometric characters (such as wing, tail, tarsus, and culmen length). More details about the methods used in these taxonomic revisions can be found in the papers by Lopes and Gonzaga (2014, 2016a, b) and Lopes et al. (2017), among others.

Results

Levels of endemicity

Using the traditional taxonomy at the species level as taxonomic units (BSC-species), we identified 60 species as potentially endemic to the Cerrado (Supporting Information, Table S1). After an exhaustive review of the geographical range of these species, we found that 49 of those 60 species could not be considered Cerrado endemics (Supporting Information Table S1; Appendix S1) because their ranges extend beyond the thresholds established here. Therefore, only 11 species fulfilled all criteria to be endemic to the Cerrado (Table 1; Supporting Information, Appendix S3). When considering the traditional taxonomy at the subspecies level as taxonomic units (BSC-subspecies), 108 bird taxa were identified as potentially endemic to the Cerrado (Supporting Information, Tables S1 and S2). After checking their ranges, we found that only 31 of those 108 taxa fulfilled all criteria to be Cerrado endemics (Supporting Information, Appendix S4). Finally, when using only those species recognized under the revised alternative taxonomy, we identified 19 Cerrado endemics (Tables 1 and 2).

Species and subspecies of birds considered potentially endemic to the Cerrado. All the taxa included in this table had their geographical range revised in detail and, if necessary, their taxonomic status revised. The traditional taxonomy is based on the work of Dickinson (2003) and the revised alternative taxonomy on the taxonomic studies summarized in the Supporting Information (Appendix S2).

| Traditional taxonomy . | Revised alternative taxonomy . | Number of grid cells (0.25° × 0.25°) with occurrence . | . | . | Endemicity status . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species . | Subspecies . | Species . | Cerrado . | Non-Cerrado . | Total . | Percentage of range in Cerrado . | Furthest record from the limits of the Cerrado (km) . | Traditional taxonomy . | Revised taxonomy . |

| Crypturellus undulatus vermiculatus | Not revised | 60 | 6 | 66 | 0.91 | 240 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Nothura minor | Nothura minor | 36 | 2 | 38 | 0.95 | 70 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Nothura maculosa major | Invalid | 21 | 1 | 22 | 0.95 | 70 | Endemic | ||

| Taoniscus nanus | Taoniscus nanus | 31 | 3 | 34 | 0.91 | 420 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Penelope ochrogaster | Penelope ochrogaster | 52 | 12 | 64 | 0.81 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Chordeilles pusillus pusillus | Not revised | 16 | 2 | 18 | 0.89 | 440 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Nyctiprogne vielliardi | Nyctiprogne vielliardi | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0.88 | 20 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Eleothreptus candicans | Eleothreptus candicans | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0.57 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Phaethornis nattereria | 34 | 16 | 50 | 0.68 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis nattereri | 16 | 11 | 27 | 0.59 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis maranhaoensisb | 18 | 5 | 23 | 0.78 | 100 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis pretrei schwartib | Invalid | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 115 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes scutatus† | Augastes scutatus | 33 | 3 | 36 | 0.92 | 50 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Augastes s. scutatus | Monotypic | 24 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 5 | Endemic | ||

| Augates s. soaresi | Invalid | 6 | 2 | 8 | 0.75 | 50 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes s. ilseae | Invalid | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.75 | 25 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes lumachella | Augastes lumachella | 1 | 20 | 21 | 0.05 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Colibri delphinae grenwaltib | Invalid | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 130 | Non-endemic | ||

| Heliactin bilophus | Heliactin bilophus | 118 | 20 | 138 | 0.86 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Campylopterus largipennis diamantinensis | 23 | 2 | 25 | 0.92 | 30 | Endemic | |||

| Campylopterus diamantinensis | 12 | 1 | 13 | 0.92 | 30 | Endemic | |||

| Campylopterus calcirupicolac | 11 | 1 | 12 | 0.92 | 15 | Endemic | |||

| Piaya cayana cabanisi | Invalid | 26 | 6 | 32 | 0.81 | 190 | Non-endemic | ||

| Patagioenas plumbea baeri | Not revised | 12 | 1 | 13 | 0.92 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Columbina cyanopis | Columbina cyanopis | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Uropelia campestris† | Uropelia campestris | 74 | 28 | 102 | 0.73 | 840 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Uropelia c. campestris | Monotypic | 56 | 9 | 65 | 0.86 | 840 | Non-endemic | ||

| Uropelia c. figginsi | Invalid | 18 | 19 | 37 | 0.49 | 550 | Non-endemic | ||

| Micropygia schomburgkii† | Micropygia schomburgkii | 35 | 59 | 94 | 0.63 | 4200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Micropygia schomburgkii schomburgkii | 0 | 41 | 41 | 0 | 4200 | Non-endemic | |||

| Micropygia schomburgkii chapmani | Invalid | 35 | 18 | 53 | 0.66 | 620 | Non-endemic | ||

| Laterallus xenopterus | Laterallus xenopterus | 10 | 9 | 19 | 0.53 | 610 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Malacoptila striata minor | Malacoptila minor | 11 | 0 | 11 | 100% | 20 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Picumnus albosquamatus | Not revised | 222 | 59 | 281 | 0.79 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus a. albosquamatus | Not revised | 11 | 32 | 43 | 0.26 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus a. guttifer | Not revised | 211 | 27 | 238 | 0.89 | 270 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus fuscus | Picumnus fuscus | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 280 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Celeus spectabilis obrieni | Celeus obrieni | 45 | 1 | 46 | 0.98 | 55 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Alipiopsitta xanthops | Alipiopsitta xanthops | 128 | 16 | 144 | 0.89 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Pyrrhura pfrimeri | Pyrrhura pfrimeri | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Geositta poeciloptera | Geositta poeciloptera | 52 | 3 | 54 | 0.96 | 95 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Sittasomus griseicapillus transitivus | Not revised | 8 | 13 | 21 | 0.38 | 660 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Xiphocolaptes falcirostris franciscanus | Not revised | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.83 | 15 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Lepidocolaptes squamatus wagleri | Lepidocolaptes wagleri | 16 | 2 | 18 | 0.89 | 25 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Furnarius leucopus araguaiae | Invalid | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Cinclodes pabsti | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |||||||

| Cinclodes espinhacensisd | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | |||

| Syndactyla dimidiata† | Syndactyla dimidiata | 42 | 5 | 46 | 0.91 | 75 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Syndactyla d. dimidiata | Monotypic | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Syndactyla d. baeri | Invalid | 37 | 4 | 41 | 0.9 | 75 | Endemic | ||

| Dendroma rufa chapadensis | Invalid | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Clibanornis rectirostris | Clibanornis rectirostris | 139 | 18 | 157 | 0.89 | 110 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Asthenes luizae | Asthenes luizae | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Synalaxis albilora† | 43 | 34 | 77 | 0.55 | 230 | Non-endemic | |||

| Synallaxis a. albilora | Synallaxis albilora | 27 | 34 | 61 | 0.44 | 230 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Synallaxis a. simoni | Synallaxis simoni | 16 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Formicivora grantsaui | Formicivora grantsaui | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 150 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Herpsilochmus longirostris | Herpsilochmus longirostris | 140 | 21 | 161 | 0.87 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Dysithamnus mentalis affinis | Not revised | 42 | 5 | 47 | 0.89 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Thamnophilus doliatus difficilis | Invalid | 38 | 2 | 40 | 0.95 | 75 | Endemic | ||

| Thamnophilus caerulescens ochraceiventer | Invalid | 10 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Thamnophilus torquatus | Thamnophilus torquatus | 111 | 46 | 157 | 0.71 | 750 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sakesphorus luctuosus araguayae | Invalid | 10 | 1 | 11 | 0.91 | 40 | Endemic | ||

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | Cercomacra ferdinandi | 33 | 2 | 35 | 0.94 | 65 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Scytalopus diamantinensis | Scytalopus diamantinensis | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 190 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Scytalopus novacapitalis | Scytalopus novacapitalis | 13 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Melanopareia torquata† | 142 | 23 | 165 | 0.86 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Melanopareia t. torquata | Melanopareia torquata | 59 | 11 | 70 | 0.84 | 370 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Melanopareia t. rufescens | Invalid | 74 | 3 | 77 | 0.96 | 95 | Endemic | ||

| Melanopareia t. bitorquata | Melanopareia bitorquata | 9 | 9 | 18 | 0.5 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Phyllomyias reiseri | Phyllomyias reiseri | 21 | 3 | 24 | 0.88 | 70 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Suiriri suiriri burmeisteri | Not revised | 88 | 25 | 113 | 0.78 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Polystictus superciliaris | Polystictus superciliaris | 34 | 15 | 49 | 0.69 | 175 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Euscarthmus rufomarginatus† | Euscarthmus rufomarginatus | 41 | 12 | 53 | 0.77 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Euscarthmus r. rufomarginatus | Monotypic | 41 | 11 | 52 | 0.79 | 440 | Non-endemic | ||

| Euscarthmus r. savannophilus | Invalid | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1200 | Non-endemic | ||

| Phylloscartes roquettei | Phylloscartes roquettei | 19 | 3 | 22 | 0.86 | 120 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Guyramemua affine | Guyramemua affine | 40 | 4 | 44 | 0.91 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Poecilotriccus latirostris ochropterus | Not revised | 30 | 9 | 39 | 0.77 | 570 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Platyrinchus mystaceus bifasciatus | Not revised | 15 | 7 | 22 | 0.68 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Knipolegus nigerrimus hoflingae | Invalid | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 170 | Non-endemic | ||

| Knipolegus aterrimus franciscanus | Knipolegus franciscanus | 21 | 5 | 26 | 0.81 | 40 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sirystes sibilator atimastus | Invalid | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Antilophia galeata | Antilophia galeata | 282 | 20 | 302 | 0.93 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cyanocorax cristatellus | Cyanocorax cristatellus | 331 | 80 | 411 | 0.81 | 370 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Pheugopedius genibarbis intercedens | Not revised | 41 | 15 | 56 | 0.73 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Arremon franciscanus | Arremon franciscanus | 6 | 8 | 14 | 0.43 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Arremon flavirostris flavirostris | Arremon flavirostris | 113 | 11 | 124 | 0.91 | 55 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Icterus cayanensis valenciobuenoi | Invalid | 38 | 3 | 41 | 0.93 | 70 | Endemic | ||

| Myiothlypis leucophrys | Myiothlypis leucophrys | 84 | 2 | 86 | 0.98 | 15 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Basileuterus culicivorus hypoleucus | Not revised | 138 | 30 | 168 | 0.82 | 200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Charitospiza eucosma | Charitospiza eucosma | 124 | 6 | 130 | 0.95 | 640 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Embernagra longicauda | Embernagra longicauda | 44 | 17 | 62 | 0.71 | 170 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Porphyrospiza caerulescens | Porphyrospiza caerulescens | 112 | 13 | 126 | 0.89 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Saltatricula atricollis | Saltatricula atricollis | 289 | 69 | 358 | 0.81 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Coereba flaveola alleni | Invalid | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Conothraupis mesoleuca | Conothraupis mesoleuca | 8 | 1 | 9 | 0.89 | 320 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Loriotus cristatus nattereri | Invalid | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Ramphocelus carbo centralis | Not revised | 79 | 26 | 105 | 0.75 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sporophila melanops | Invalid | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Sporophila nigrorufa | Sporophila nigrorufa | 7 | 10 | 17 | 0.41 | 340 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra hirundinacea† | C. hirundinacea | 133 | 43 | 176 | 0.76 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra h. hirundinacea | Not revised | 92 | 11 | 103 | 0.89 | 170 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra h. pallidigula | Not revised | 41 | 32 | 73 | 0.56 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Microspingus cinereus | Microspingus cinereus | 58 | 7 | 65 | 0.89 | 280 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sicalis citrina citrina | Not revised | 65 | 17 | 82 | 0.79 | 440 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Neothraupis fasciata | Neothraupis fasciata | 155 | 16 | 171 | 0.91 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Schistochlamys ruficapillus sicki | Invalid | 12 | 6 | 18 | 0.67 | 660 | Non-endemic | ||

| Paroaria baeri† | 19 | 2 | 21 | 0.95 | 140 | Non-endemic | |||

| Paroaria b. baeri | Paroaria baeri | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Paroaria b. xinguensis | Paroaria xinguensis | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Stilpnia cyanicollis albotibialis | Stilpnia albotibialis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Stilpnia cayana margaritae | Invalid | 7 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Stilpnia cayana sincipitalis | Invalid | 31 | 2 | 33 | 0.94 | 120 | Non-endemic | ||

| Traditional taxonomy . | Revised alternative taxonomy . | Number of grid cells (0.25° × 0.25°) with occurrence . | . | . | Endemicity status . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species . | Subspecies . | Species . | Cerrado . | Non-Cerrado . | Total . | Percentage of range in Cerrado . | Furthest record from the limits of the Cerrado (km) . | Traditional taxonomy . | Revised taxonomy . |

| Crypturellus undulatus vermiculatus | Not revised | 60 | 6 | 66 | 0.91 | 240 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Nothura minor | Nothura minor | 36 | 2 | 38 | 0.95 | 70 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Nothura maculosa major | Invalid | 21 | 1 | 22 | 0.95 | 70 | Endemic | ||

| Taoniscus nanus | Taoniscus nanus | 31 | 3 | 34 | 0.91 | 420 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Penelope ochrogaster | Penelope ochrogaster | 52 | 12 | 64 | 0.81 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Chordeilles pusillus pusillus | Not revised | 16 | 2 | 18 | 0.89 | 440 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Nyctiprogne vielliardi | Nyctiprogne vielliardi | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0.88 | 20 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Eleothreptus candicans | Eleothreptus candicans | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0.57 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Phaethornis nattereria | 34 | 16 | 50 | 0.68 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis nattereri | 16 | 11 | 27 | 0.59 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis maranhaoensisb | 18 | 5 | 23 | 0.78 | 100 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis pretrei schwartib | Invalid | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 115 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes scutatus† | Augastes scutatus | 33 | 3 | 36 | 0.92 | 50 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Augastes s. scutatus | Monotypic | 24 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 5 | Endemic | ||

| Augates s. soaresi | Invalid | 6 | 2 | 8 | 0.75 | 50 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes s. ilseae | Invalid | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.75 | 25 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes lumachella | Augastes lumachella | 1 | 20 | 21 | 0.05 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Colibri delphinae grenwaltib | Invalid | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 130 | Non-endemic | ||

| Heliactin bilophus | Heliactin bilophus | 118 | 20 | 138 | 0.86 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Campylopterus largipennis diamantinensis | 23 | 2 | 25 | 0.92 | 30 | Endemic | |||

| Campylopterus diamantinensis | 12 | 1 | 13 | 0.92 | 30 | Endemic | |||

| Campylopterus calcirupicolac | 11 | 1 | 12 | 0.92 | 15 | Endemic | |||

| Piaya cayana cabanisi | Invalid | 26 | 6 | 32 | 0.81 | 190 | Non-endemic | ||

| Patagioenas plumbea baeri | Not revised | 12 | 1 | 13 | 0.92 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Columbina cyanopis | Columbina cyanopis | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Uropelia campestris† | Uropelia campestris | 74 | 28 | 102 | 0.73 | 840 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Uropelia c. campestris | Monotypic | 56 | 9 | 65 | 0.86 | 840 | Non-endemic | ||

| Uropelia c. figginsi | Invalid | 18 | 19 | 37 | 0.49 | 550 | Non-endemic | ||

| Micropygia schomburgkii† | Micropygia schomburgkii | 35 | 59 | 94 | 0.63 | 4200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Micropygia schomburgkii schomburgkii | 0 | 41 | 41 | 0 | 4200 | Non-endemic | |||

| Micropygia schomburgkii chapmani | Invalid | 35 | 18 | 53 | 0.66 | 620 | Non-endemic | ||

| Laterallus xenopterus | Laterallus xenopterus | 10 | 9 | 19 | 0.53 | 610 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Malacoptila striata minor | Malacoptila minor | 11 | 0 | 11 | 100% | 20 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Picumnus albosquamatus | Not revised | 222 | 59 | 281 | 0.79 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus a. albosquamatus | Not revised | 11 | 32 | 43 | 0.26 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus a. guttifer | Not revised | 211 | 27 | 238 | 0.89 | 270 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus fuscus | Picumnus fuscus | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 280 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Celeus spectabilis obrieni | Celeus obrieni | 45 | 1 | 46 | 0.98 | 55 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Alipiopsitta xanthops | Alipiopsitta xanthops | 128 | 16 | 144 | 0.89 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Pyrrhura pfrimeri | Pyrrhura pfrimeri | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Geositta poeciloptera | Geositta poeciloptera | 52 | 3 | 54 | 0.96 | 95 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Sittasomus griseicapillus transitivus | Not revised | 8 | 13 | 21 | 0.38 | 660 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Xiphocolaptes falcirostris franciscanus | Not revised | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.83 | 15 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Lepidocolaptes squamatus wagleri | Lepidocolaptes wagleri | 16 | 2 | 18 | 0.89 | 25 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Furnarius leucopus araguaiae | Invalid | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Cinclodes pabsti | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |||||||

| Cinclodes espinhacensisd | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | |||

| Syndactyla dimidiata† | Syndactyla dimidiata | 42 | 5 | 46 | 0.91 | 75 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Syndactyla d. dimidiata | Monotypic | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Syndactyla d. baeri | Invalid | 37 | 4 | 41 | 0.9 | 75 | Endemic | ||

| Dendroma rufa chapadensis | Invalid | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Clibanornis rectirostris | Clibanornis rectirostris | 139 | 18 | 157 | 0.89 | 110 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Asthenes luizae | Asthenes luizae | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Synalaxis albilora† | 43 | 34 | 77 | 0.55 | 230 | Non-endemic | |||

| Synallaxis a. albilora | Synallaxis albilora | 27 | 34 | 61 | 0.44 | 230 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Synallaxis a. simoni | Synallaxis simoni | 16 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Formicivora grantsaui | Formicivora grantsaui | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 150 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Herpsilochmus longirostris | Herpsilochmus longirostris | 140 | 21 | 161 | 0.87 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Dysithamnus mentalis affinis | Not revised | 42 | 5 | 47 | 0.89 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Thamnophilus doliatus difficilis | Invalid | 38 | 2 | 40 | 0.95 | 75 | Endemic | ||

| Thamnophilus caerulescens ochraceiventer | Invalid | 10 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Thamnophilus torquatus | Thamnophilus torquatus | 111 | 46 | 157 | 0.71 | 750 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sakesphorus luctuosus araguayae | Invalid | 10 | 1 | 11 | 0.91 | 40 | Endemic | ||

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | Cercomacra ferdinandi | 33 | 2 | 35 | 0.94 | 65 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Scytalopus diamantinensis | Scytalopus diamantinensis | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 190 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Scytalopus novacapitalis | Scytalopus novacapitalis | 13 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Melanopareia torquata† | 142 | 23 | 165 | 0.86 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Melanopareia t. torquata | Melanopareia torquata | 59 | 11 | 70 | 0.84 | 370 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Melanopareia t. rufescens | Invalid | 74 | 3 | 77 | 0.96 | 95 | Endemic | ||

| Melanopareia t. bitorquata | Melanopareia bitorquata | 9 | 9 | 18 | 0.5 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Phyllomyias reiseri | Phyllomyias reiseri | 21 | 3 | 24 | 0.88 | 70 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Suiriri suiriri burmeisteri | Not revised | 88 | 25 | 113 | 0.78 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Polystictus superciliaris | Polystictus superciliaris | 34 | 15 | 49 | 0.69 | 175 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Euscarthmus rufomarginatus† | Euscarthmus rufomarginatus | 41 | 12 | 53 | 0.77 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Euscarthmus r. rufomarginatus | Monotypic | 41 | 11 | 52 | 0.79 | 440 | Non-endemic | ||

| Euscarthmus r. savannophilus | Invalid | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1200 | Non-endemic | ||

| Phylloscartes roquettei | Phylloscartes roquettei | 19 | 3 | 22 | 0.86 | 120 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Guyramemua affine | Guyramemua affine | 40 | 4 | 44 | 0.91 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Poecilotriccus latirostris ochropterus | Not revised | 30 | 9 | 39 | 0.77 | 570 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Platyrinchus mystaceus bifasciatus | Not revised | 15 | 7 | 22 | 0.68 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Knipolegus nigerrimus hoflingae | Invalid | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 170 | Non-endemic | ||

| Knipolegus aterrimus franciscanus | Knipolegus franciscanus | 21 | 5 | 26 | 0.81 | 40 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sirystes sibilator atimastus | Invalid | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Antilophia galeata | Antilophia galeata | 282 | 20 | 302 | 0.93 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cyanocorax cristatellus | Cyanocorax cristatellus | 331 | 80 | 411 | 0.81 | 370 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Pheugopedius genibarbis intercedens | Not revised | 41 | 15 | 56 | 0.73 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Arremon franciscanus | Arremon franciscanus | 6 | 8 | 14 | 0.43 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Arremon flavirostris flavirostris | Arremon flavirostris | 113 | 11 | 124 | 0.91 | 55 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Icterus cayanensis valenciobuenoi | Invalid | 38 | 3 | 41 | 0.93 | 70 | Endemic | ||

| Myiothlypis leucophrys | Myiothlypis leucophrys | 84 | 2 | 86 | 0.98 | 15 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Basileuterus culicivorus hypoleucus | Not revised | 138 | 30 | 168 | 0.82 | 200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Charitospiza eucosma | Charitospiza eucosma | 124 | 6 | 130 | 0.95 | 640 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Embernagra longicauda | Embernagra longicauda | 44 | 17 | 62 | 0.71 | 170 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Porphyrospiza caerulescens | Porphyrospiza caerulescens | 112 | 13 | 126 | 0.89 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Saltatricula atricollis | Saltatricula atricollis | 289 | 69 | 358 | 0.81 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Coereba flaveola alleni | Invalid | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Conothraupis mesoleuca | Conothraupis mesoleuca | 8 | 1 | 9 | 0.89 | 320 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Loriotus cristatus nattereri | Invalid | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Ramphocelus carbo centralis | Not revised | 79 | 26 | 105 | 0.75 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sporophila melanops | Invalid | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Sporophila nigrorufa | Sporophila nigrorufa | 7 | 10 | 17 | 0.41 | 340 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra hirundinacea† | C. hirundinacea | 133 | 43 | 176 | 0.76 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra h. hirundinacea | Not revised | 92 | 11 | 103 | 0.89 | 170 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra h. pallidigula | Not revised | 41 | 32 | 73 | 0.56 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Microspingus cinereus | Microspingus cinereus | 58 | 7 | 65 | 0.89 | 280 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sicalis citrina citrina | Not revised | 65 | 17 | 82 | 0.79 | 440 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Neothraupis fasciata | Neothraupis fasciata | 155 | 16 | 171 | 0.91 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Schistochlamys ruficapillus sicki | Invalid | 12 | 6 | 18 | 0.67 | 660 | Non-endemic | ||

| Paroaria baeri† | 19 | 2 | 21 | 0.95 | 140 | Non-endemic | |||

| Paroaria b. baeri | Paroaria baeri | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Paroaria b. xinguensis | Paroaria xinguensis | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Stilpnia cyanicollis albotibialis | Stilpnia albotibialis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Stilpnia cayana margaritae | Invalid | 7 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Stilpnia cayana sincipitalis | Invalid | 31 | 2 | 33 | 0.94 | 120 | Non-endemic | ||

†Polytypic species according to the traditional taxonomy.

aThe taxonomy of the Phaethornis nattereri complex is problematic, with some authors considering P. maranhaoensis as a subspecies of P. nattereri or as inseparable from P. nattereri (Hinkelmann 1988, Piacentini 2011).

bTaxon not recognized by Dickinson (2003).

cCampylopterus calcirupicola is a recently described species whose populations have been, until recently, identified as belonging to Campylopterus largipennis diamantinensis (Silva 1990).

dCinclodes espinhacensis is a recently described species whose populations have been, until recently, identified as belonging to Cinclodes pabsti (Freitas et al. 2008).

Species and subspecies of birds considered potentially endemic to the Cerrado. All the taxa included in this table had their geographical range revised in detail and, if necessary, their taxonomic status revised. The traditional taxonomy is based on the work of Dickinson (2003) and the revised alternative taxonomy on the taxonomic studies summarized in the Supporting Information (Appendix S2).

| Traditional taxonomy . | Revised alternative taxonomy . | Number of grid cells (0.25° × 0.25°) with occurrence . | . | . | Endemicity status . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species . | Subspecies . | Species . | Cerrado . | Non-Cerrado . | Total . | Percentage of range in Cerrado . | Furthest record from the limits of the Cerrado (km) . | Traditional taxonomy . | Revised taxonomy . |

| Crypturellus undulatus vermiculatus | Not revised | 60 | 6 | 66 | 0.91 | 240 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Nothura minor | Nothura minor | 36 | 2 | 38 | 0.95 | 70 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Nothura maculosa major | Invalid | 21 | 1 | 22 | 0.95 | 70 | Endemic | ||

| Taoniscus nanus | Taoniscus nanus | 31 | 3 | 34 | 0.91 | 420 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Penelope ochrogaster | Penelope ochrogaster | 52 | 12 | 64 | 0.81 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Chordeilles pusillus pusillus | Not revised | 16 | 2 | 18 | 0.89 | 440 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Nyctiprogne vielliardi | Nyctiprogne vielliardi | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0.88 | 20 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Eleothreptus candicans | Eleothreptus candicans | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0.57 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Phaethornis nattereria | 34 | 16 | 50 | 0.68 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis nattereri | 16 | 11 | 27 | 0.59 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis maranhaoensisb | 18 | 5 | 23 | 0.78 | 100 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis pretrei schwartib | Invalid | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 115 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes scutatus† | Augastes scutatus | 33 | 3 | 36 | 0.92 | 50 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Augastes s. scutatus | Monotypic | 24 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 5 | Endemic | ||

| Augates s. soaresi | Invalid | 6 | 2 | 8 | 0.75 | 50 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes s. ilseae | Invalid | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.75 | 25 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes lumachella | Augastes lumachella | 1 | 20 | 21 | 0.05 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Colibri delphinae grenwaltib | Invalid | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 130 | Non-endemic | ||

| Heliactin bilophus | Heliactin bilophus | 118 | 20 | 138 | 0.86 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Campylopterus largipennis diamantinensis | 23 | 2 | 25 | 0.92 | 30 | Endemic | |||

| Campylopterus diamantinensis | 12 | 1 | 13 | 0.92 | 30 | Endemic | |||

| Campylopterus calcirupicolac | 11 | 1 | 12 | 0.92 | 15 | Endemic | |||

| Piaya cayana cabanisi | Invalid | 26 | 6 | 32 | 0.81 | 190 | Non-endemic | ||

| Patagioenas plumbea baeri | Not revised | 12 | 1 | 13 | 0.92 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Columbina cyanopis | Columbina cyanopis | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Uropelia campestris† | Uropelia campestris | 74 | 28 | 102 | 0.73 | 840 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Uropelia c. campestris | Monotypic | 56 | 9 | 65 | 0.86 | 840 | Non-endemic | ||

| Uropelia c. figginsi | Invalid | 18 | 19 | 37 | 0.49 | 550 | Non-endemic | ||

| Micropygia schomburgkii† | Micropygia schomburgkii | 35 | 59 | 94 | 0.63 | 4200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Micropygia schomburgkii schomburgkii | 0 | 41 | 41 | 0 | 4200 | Non-endemic | |||

| Micropygia schomburgkii chapmani | Invalid | 35 | 18 | 53 | 0.66 | 620 | Non-endemic | ||

| Laterallus xenopterus | Laterallus xenopterus | 10 | 9 | 19 | 0.53 | 610 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Malacoptila striata minor | Malacoptila minor | 11 | 0 | 11 | 100% | 20 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Picumnus albosquamatus | Not revised | 222 | 59 | 281 | 0.79 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus a. albosquamatus | Not revised | 11 | 32 | 43 | 0.26 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus a. guttifer | Not revised | 211 | 27 | 238 | 0.89 | 270 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus fuscus | Picumnus fuscus | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 280 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Celeus spectabilis obrieni | Celeus obrieni | 45 | 1 | 46 | 0.98 | 55 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Alipiopsitta xanthops | Alipiopsitta xanthops | 128 | 16 | 144 | 0.89 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Pyrrhura pfrimeri | Pyrrhura pfrimeri | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Geositta poeciloptera | Geositta poeciloptera | 52 | 3 | 54 | 0.96 | 95 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Sittasomus griseicapillus transitivus | Not revised | 8 | 13 | 21 | 0.38 | 660 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Xiphocolaptes falcirostris franciscanus | Not revised | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.83 | 15 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Lepidocolaptes squamatus wagleri | Lepidocolaptes wagleri | 16 | 2 | 18 | 0.89 | 25 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Furnarius leucopus araguaiae | Invalid | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Cinclodes pabsti | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |||||||

| Cinclodes espinhacensisd | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | |||

| Syndactyla dimidiata† | Syndactyla dimidiata | 42 | 5 | 46 | 0.91 | 75 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Syndactyla d. dimidiata | Monotypic | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Syndactyla d. baeri | Invalid | 37 | 4 | 41 | 0.9 | 75 | Endemic | ||

| Dendroma rufa chapadensis | Invalid | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Clibanornis rectirostris | Clibanornis rectirostris | 139 | 18 | 157 | 0.89 | 110 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Asthenes luizae | Asthenes luizae | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Synalaxis albilora† | 43 | 34 | 77 | 0.55 | 230 | Non-endemic | |||

| Synallaxis a. albilora | Synallaxis albilora | 27 | 34 | 61 | 0.44 | 230 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Synallaxis a. simoni | Synallaxis simoni | 16 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Formicivora grantsaui | Formicivora grantsaui | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 150 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Herpsilochmus longirostris | Herpsilochmus longirostris | 140 | 21 | 161 | 0.87 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Dysithamnus mentalis affinis | Not revised | 42 | 5 | 47 | 0.89 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Thamnophilus doliatus difficilis | Invalid | 38 | 2 | 40 | 0.95 | 75 | Endemic | ||

| Thamnophilus caerulescens ochraceiventer | Invalid | 10 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Thamnophilus torquatus | Thamnophilus torquatus | 111 | 46 | 157 | 0.71 | 750 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sakesphorus luctuosus araguayae | Invalid | 10 | 1 | 11 | 0.91 | 40 | Endemic | ||

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | Cercomacra ferdinandi | 33 | 2 | 35 | 0.94 | 65 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Scytalopus diamantinensis | Scytalopus diamantinensis | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 190 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Scytalopus novacapitalis | Scytalopus novacapitalis | 13 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Melanopareia torquata† | 142 | 23 | 165 | 0.86 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Melanopareia t. torquata | Melanopareia torquata | 59 | 11 | 70 | 0.84 | 370 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Melanopareia t. rufescens | Invalid | 74 | 3 | 77 | 0.96 | 95 | Endemic | ||

| Melanopareia t. bitorquata | Melanopareia bitorquata | 9 | 9 | 18 | 0.5 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Phyllomyias reiseri | Phyllomyias reiseri | 21 | 3 | 24 | 0.88 | 70 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Suiriri suiriri burmeisteri | Not revised | 88 | 25 | 113 | 0.78 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Polystictus superciliaris | Polystictus superciliaris | 34 | 15 | 49 | 0.69 | 175 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Euscarthmus rufomarginatus† | Euscarthmus rufomarginatus | 41 | 12 | 53 | 0.77 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Euscarthmus r. rufomarginatus | Monotypic | 41 | 11 | 52 | 0.79 | 440 | Non-endemic | ||

| Euscarthmus r. savannophilus | Invalid | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1200 | Non-endemic | ||

| Phylloscartes roquettei | Phylloscartes roquettei | 19 | 3 | 22 | 0.86 | 120 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Guyramemua affine | Guyramemua affine | 40 | 4 | 44 | 0.91 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Poecilotriccus latirostris ochropterus | Not revised | 30 | 9 | 39 | 0.77 | 570 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Platyrinchus mystaceus bifasciatus | Not revised | 15 | 7 | 22 | 0.68 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Knipolegus nigerrimus hoflingae | Invalid | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 170 | Non-endemic | ||

| Knipolegus aterrimus franciscanus | Knipolegus franciscanus | 21 | 5 | 26 | 0.81 | 40 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sirystes sibilator atimastus | Invalid | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Antilophia galeata | Antilophia galeata | 282 | 20 | 302 | 0.93 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cyanocorax cristatellus | Cyanocorax cristatellus | 331 | 80 | 411 | 0.81 | 370 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Pheugopedius genibarbis intercedens | Not revised | 41 | 15 | 56 | 0.73 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Arremon franciscanus | Arremon franciscanus | 6 | 8 | 14 | 0.43 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Arremon flavirostris flavirostris | Arremon flavirostris | 113 | 11 | 124 | 0.91 | 55 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Icterus cayanensis valenciobuenoi | Invalid | 38 | 3 | 41 | 0.93 | 70 | Endemic | ||

| Myiothlypis leucophrys | Myiothlypis leucophrys | 84 | 2 | 86 | 0.98 | 15 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Basileuterus culicivorus hypoleucus | Not revised | 138 | 30 | 168 | 0.82 | 200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Charitospiza eucosma | Charitospiza eucosma | 124 | 6 | 130 | 0.95 | 640 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Embernagra longicauda | Embernagra longicauda | 44 | 17 | 62 | 0.71 | 170 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Porphyrospiza caerulescens | Porphyrospiza caerulescens | 112 | 13 | 126 | 0.89 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Saltatricula atricollis | Saltatricula atricollis | 289 | 69 | 358 | 0.81 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Coereba flaveola alleni | Invalid | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Conothraupis mesoleuca | Conothraupis mesoleuca | 8 | 1 | 9 | 0.89 | 320 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Loriotus cristatus nattereri | Invalid | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Ramphocelus carbo centralis | Not revised | 79 | 26 | 105 | 0.75 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sporophila melanops | Invalid | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Sporophila nigrorufa | Sporophila nigrorufa | 7 | 10 | 17 | 0.41 | 340 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra hirundinacea† | C. hirundinacea | 133 | 43 | 176 | 0.76 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra h. hirundinacea | Not revised | 92 | 11 | 103 | 0.89 | 170 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra h. pallidigula | Not revised | 41 | 32 | 73 | 0.56 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Microspingus cinereus | Microspingus cinereus | 58 | 7 | 65 | 0.89 | 280 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sicalis citrina citrina | Not revised | 65 | 17 | 82 | 0.79 | 440 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Neothraupis fasciata | Neothraupis fasciata | 155 | 16 | 171 | 0.91 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Schistochlamys ruficapillus sicki | Invalid | 12 | 6 | 18 | 0.67 | 660 | Non-endemic | ||

| Paroaria baeri† | 19 | 2 | 21 | 0.95 | 140 | Non-endemic | |||

| Paroaria b. baeri | Paroaria baeri | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Paroaria b. xinguensis | Paroaria xinguensis | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Stilpnia cyanicollis albotibialis | Stilpnia albotibialis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Stilpnia cayana margaritae | Invalid | 7 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Stilpnia cayana sincipitalis | Invalid | 31 | 2 | 33 | 0.94 | 120 | Non-endemic | ||

| Traditional taxonomy . | Revised alternative taxonomy . | Number of grid cells (0.25° × 0.25°) with occurrence . | . | . | Endemicity status . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species . | Subspecies . | Species . | Cerrado . | Non-Cerrado . | Total . | Percentage of range in Cerrado . | Furthest record from the limits of the Cerrado (km) . | Traditional taxonomy . | Revised taxonomy . |

| Crypturellus undulatus vermiculatus | Not revised | 60 | 6 | 66 | 0.91 | 240 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Nothura minor | Nothura minor | 36 | 2 | 38 | 0.95 | 70 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Nothura maculosa major | Invalid | 21 | 1 | 22 | 0.95 | 70 | Endemic | ||

| Taoniscus nanus | Taoniscus nanus | 31 | 3 | 34 | 0.91 | 420 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Penelope ochrogaster | Penelope ochrogaster | 52 | 12 | 64 | 0.81 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Chordeilles pusillus pusillus | Not revised | 16 | 2 | 18 | 0.89 | 440 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Nyctiprogne vielliardi | Nyctiprogne vielliardi | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0.88 | 20 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Eleothreptus candicans | Eleothreptus candicans | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0.57 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Phaethornis nattereria | 34 | 16 | 50 | 0.68 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis nattereri | 16 | 11 | 27 | 0.59 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis maranhaoensisb | 18 | 5 | 23 | 0.78 | 100 | Non-endemic | |||

| Phaethornis pretrei schwartib | Invalid | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 115 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes scutatus† | Augastes scutatus | 33 | 3 | 36 | 0.92 | 50 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Augastes s. scutatus | Monotypic | 24 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 5 | Endemic | ||

| Augates s. soaresi | Invalid | 6 | 2 | 8 | 0.75 | 50 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes s. ilseae | Invalid | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.75 | 25 | Non-endemic | ||

| Augastes lumachella | Augastes lumachella | 1 | 20 | 21 | 0.05 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Colibri delphinae grenwaltib | Invalid | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 130 | Non-endemic | ||

| Heliactin bilophus | Heliactin bilophus | 118 | 20 | 138 | 0.86 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Campylopterus largipennis diamantinensis | 23 | 2 | 25 | 0.92 | 30 | Endemic | |||

| Campylopterus diamantinensis | 12 | 1 | 13 | 0.92 | 30 | Endemic | |||

| Campylopterus calcirupicolac | 11 | 1 | 12 | 0.92 | 15 | Endemic | |||

| Piaya cayana cabanisi | Invalid | 26 | 6 | 32 | 0.81 | 190 | Non-endemic | ||

| Patagioenas plumbea baeri | Not revised | 12 | 1 | 13 | 0.92 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Columbina cyanopis | Columbina cyanopis | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Uropelia campestris† | Uropelia campestris | 74 | 28 | 102 | 0.73 | 840 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Uropelia c. campestris | Monotypic | 56 | 9 | 65 | 0.86 | 840 | Non-endemic | ||

| Uropelia c. figginsi | Invalid | 18 | 19 | 37 | 0.49 | 550 | Non-endemic | ||

| Micropygia schomburgkii† | Micropygia schomburgkii | 35 | 59 | 94 | 0.63 | 4200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Micropygia schomburgkii schomburgkii | 0 | 41 | 41 | 0 | 4200 | Non-endemic | |||

| Micropygia schomburgkii chapmani | Invalid | 35 | 18 | 53 | 0.66 | 620 | Non-endemic | ||

| Laterallus xenopterus | Laterallus xenopterus | 10 | 9 | 19 | 0.53 | 610 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Malacoptila striata minor | Malacoptila minor | 11 | 0 | 11 | 100% | 20 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Picumnus albosquamatus | Not revised | 222 | 59 | 281 | 0.79 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus a. albosquamatus | Not revised | 11 | 32 | 43 | 0.26 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus a. guttifer | Not revised | 211 | 27 | 238 | 0.89 | 270 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Picumnus fuscus | Picumnus fuscus | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 280 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Celeus spectabilis obrieni | Celeus obrieni | 45 | 1 | 46 | 0.98 | 55 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Alipiopsitta xanthops | Alipiopsitta xanthops | 128 | 16 | 144 | 0.89 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Pyrrhura pfrimeri | Pyrrhura pfrimeri | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Geositta poeciloptera | Geositta poeciloptera | 52 | 3 | 54 | 0.96 | 95 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Sittasomus griseicapillus transitivus | Not revised | 8 | 13 | 21 | 0.38 | 660 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Xiphocolaptes falcirostris franciscanus | Not revised | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.83 | 15 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Lepidocolaptes squamatus wagleri | Lepidocolaptes wagleri | 16 | 2 | 18 | 0.89 | 25 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Furnarius leucopus araguaiae | Invalid | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Cinclodes pabsti | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |||||||

| Cinclodes espinhacensisd | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | |||

| Syndactyla dimidiata† | Syndactyla dimidiata | 42 | 5 | 46 | 0.91 | 75 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Syndactyla d. dimidiata | Monotypic | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Syndactyla d. baeri | Invalid | 37 | 4 | 41 | 0.9 | 75 | Endemic | ||

| Dendroma rufa chapadensis | Invalid | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Clibanornis rectirostris | Clibanornis rectirostris | 139 | 18 | 157 | 0.89 | 110 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Asthenes luizae | Asthenes luizae | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Synalaxis albilora† | 43 | 34 | 77 | 0.55 | 230 | Non-endemic | |||

| Synallaxis a. albilora | Synallaxis albilora | 27 | 34 | 61 | 0.44 | 230 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Synallaxis a. simoni | Synallaxis simoni | 16 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Formicivora grantsaui | Formicivora grantsaui | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 150 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Herpsilochmus longirostris | Herpsilochmus longirostris | 140 | 21 | 161 | 0.87 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Dysithamnus mentalis affinis | Not revised | 42 | 5 | 47 | 0.89 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Thamnophilus doliatus difficilis | Invalid | 38 | 2 | 40 | 0.95 | 75 | Endemic | ||

| Thamnophilus caerulescens ochraceiventer | Invalid | 10 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Thamnophilus torquatus | Thamnophilus torquatus | 111 | 46 | 157 | 0.71 | 750 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sakesphorus luctuosus araguayae | Invalid | 10 | 1 | 11 | 0.91 | 40 | Endemic | ||

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | Cercomacra ferdinandi | 33 | 2 | 35 | 0.94 | 65 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Scytalopus diamantinensis | Scytalopus diamantinensis | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 190 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Scytalopus novacapitalis | Scytalopus novacapitalis | 13 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Melanopareia torquata† | 142 | 23 | 165 | 0.86 | 370 | Non-endemic | |||

| Melanopareia t. torquata | Melanopareia torquata | 59 | 11 | 70 | 0.84 | 370 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Melanopareia t. rufescens | Invalid | 74 | 3 | 77 | 0.96 | 95 | Endemic | ||

| Melanopareia t. bitorquata | Melanopareia bitorquata | 9 | 9 | 18 | 0.5 | 250 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Phyllomyias reiseri | Phyllomyias reiseri | 21 | 3 | 24 | 0.88 | 70 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Suiriri suiriri burmeisteri | Not revised | 88 | 25 | 113 | 0.78 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Polystictus superciliaris | Polystictus superciliaris | 34 | 15 | 49 | 0.69 | 175 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Euscarthmus rufomarginatus† | Euscarthmus rufomarginatus | 41 | 12 | 53 | 0.77 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Euscarthmus r. rufomarginatus | Monotypic | 41 | 11 | 52 | 0.79 | 440 | Non-endemic | ||

| Euscarthmus r. savannophilus | Invalid | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1200 | Non-endemic | ||

| Phylloscartes roquettei | Phylloscartes roquettei | 19 | 3 | 22 | 0.86 | 120 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Guyramemua affine | Guyramemua affine | 40 | 4 | 44 | 0.91 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Poecilotriccus latirostris ochropterus | Not revised | 30 | 9 | 39 | 0.77 | 570 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Platyrinchus mystaceus bifasciatus | Not revised | 15 | 7 | 22 | 0.68 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Knipolegus nigerrimus hoflingae | Invalid | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 170 | Non-endemic | ||

| Knipolegus aterrimus franciscanus | Knipolegus franciscanus | 21 | 5 | 26 | 0.81 | 40 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sirystes sibilator atimastus | Invalid | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Antilophia galeata | Antilophia galeata | 282 | 20 | 302 | 0.93 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cyanocorax cristatellus | Cyanocorax cristatellus | 331 | 80 | 411 | 0.81 | 370 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Pheugopedius genibarbis intercedens | Not revised | 41 | 15 | 56 | 0.73 | 450 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Arremon franciscanus | Arremon franciscanus | 6 | 8 | 14 | 0.43 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Arremon flavirostris flavirostris | Arremon flavirostris | 113 | 11 | 124 | 0.91 | 55 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Icterus cayanensis valenciobuenoi | Invalid | 38 | 3 | 41 | 0.93 | 70 | Endemic | ||

| Myiothlypis leucophrys | Myiothlypis leucophrys | 84 | 2 | 86 | 0.98 | 15 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Basileuterus culicivorus hypoleucus | Not revised | 138 | 30 | 168 | 0.82 | 200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Charitospiza eucosma | Charitospiza eucosma | 124 | 6 | 130 | 0.95 | 640 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Embernagra longicauda | Embernagra longicauda | 44 | 17 | 62 | 0.71 | 170 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Porphyrospiza caerulescens | Porphyrospiza caerulescens | 112 | 13 | 126 | 0.89 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Saltatricula atricollis | Saltatricula atricollis | 289 | 69 | 358 | 0.81 | 650 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Coereba flaveola alleni | Invalid | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Conothraupis mesoleuca | Conothraupis mesoleuca | 8 | 1 | 9 | 0.89 | 320 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Loriotus cristatus nattereri | Invalid | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Ramphocelus carbo centralis | Not revised | 79 | 26 | 105 | 0.75 | 130 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sporophila melanops | Invalid | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Sporophila nigrorufa | Sporophila nigrorufa | 7 | 10 | 17 | 0.41 | 340 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra hirundinacea† | C. hirundinacea | 133 | 43 | 176 | 0.76 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra h. hirundinacea | Not revised | 92 | 11 | 103 | 0.89 | 170 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Cypsnagra h. pallidigula | Not revised | 41 | 32 | 73 | 0.56 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Microspingus cinereus | Microspingus cinereus | 58 | 7 | 65 | 0.89 | 280 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Sicalis citrina citrina | Not revised | 65 | 17 | 82 | 0.79 | 440 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Neothraupis fasciata | Neothraupis fasciata | 155 | 16 | 171 | 0.91 | 1200 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Schistochlamys ruficapillus sicki | Invalid | 12 | 6 | 18 | 0.67 | 660 | Non-endemic | ||

| Paroaria baeri† | 19 | 2 | 21 | 0.95 | 140 | Non-endemic | |||

| Paroaria b. baeri | Paroaria baeri | 19 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Paroaria b. xinguensis | Paroaria xinguensis | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 140 | Non-endemic | Non-endemic | |

| Stilpnia cyanicollis albotibialis | Stilpnia albotibialis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | Endemic | |

| Stilpnia cayana margaritae | Invalid | 7 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | Endemic | ||

| Stilpnia cayana sincipitalis | Invalid | 31 | 2 | 33 | 0.94 | 120 | Non-endemic | ||

†Polytypic species according to the traditional taxonomy.

aThe taxonomy of the Phaethornis nattereri complex is problematic, with some authors considering P. maranhaoensis as a subspecies of P. nattereri or as inseparable from P. nattereri (Hinkelmann 1988, Piacentini 2011).

bTaxon not recognized by Dickinson (2003).

cCampylopterus calcirupicola is a recently described species whose populations have been, until recently, identified as belonging to Campylopterus largipennis diamantinensis (Silva 1990).

dCinclodes espinhacensis is a recently described species whose populations have been, until recently, identified as belonging to Cinclodes pabsti (Freitas et al. 2008).

List of the bird species endemic to the Cerrado after reviewing their geographical range and taxonomy. We also indicate the sub-areas of endemism to which they are associated and present data on their main habitat and micro-habitat.

| Species . | Area of endemism . | Habitat . | Micro-habitat . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nothura minor | Grassland | ||

| Augastes scutatus | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Campylopterus calcirupicola | Bambuí Karst | Seasonally dry forest | Limestone outcrops |

| Campylopterus diamantinensis | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Columbina cyanopis | Savanna | White sand shrubland | |

| Malacoptila minor | Semideciduous forest | ||

| Celeus obrieni | Semideciduous forest | Bamboo thickets | |

| Pyrrhura pfrimeri | Bambuí Karst | Seasonally dry forest | |

| Geositta poeciloptera | Grassland | ||

| Cinclodes espinhacensis | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Syndactyla dimidiate | Riparian forest | ||

| Asthenes luizae | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | Rock outcrops |

| Synallaxis simoni | Araguaia Floodplains | Riparian forest | River created habitats |

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | Riparian forest | River created habitats | |

| Scytalopus novacapitalis | Riparian forest | ||

| Arremon flavirostris | Semideciduous forest | ||

| Myiothlypis leucophrys | Riparian forest | ||

| Paroaria baeri | Araguaia Floodplains | Riparian forest | River created habitats |

| Stilpnia albotibialis | Riparian forest |

| Species . | Area of endemism . | Habitat . | Micro-habitat . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nothura minor | Grassland | ||

| Augastes scutatus | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Campylopterus calcirupicola | Bambuí Karst | Seasonally dry forest | Limestone outcrops |

| Campylopterus diamantinensis | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Columbina cyanopis | Savanna | White sand shrubland | |

| Malacoptila minor | Semideciduous forest | ||

| Celeus obrieni | Semideciduous forest | Bamboo thickets | |

| Pyrrhura pfrimeri | Bambuí Karst | Seasonally dry forest | |

| Geositta poeciloptera | Grassland | ||

| Cinclodes espinhacensis | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Syndactyla dimidiate | Riparian forest | ||

| Asthenes luizae | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | Rock outcrops |

| Synallaxis simoni | Araguaia Floodplains | Riparian forest | River created habitats |

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | Riparian forest | River created habitats | |

| Scytalopus novacapitalis | Riparian forest | ||

| Arremon flavirostris | Semideciduous forest | ||

| Myiothlypis leucophrys | Riparian forest | ||

| Paroaria baeri | Araguaia Floodplains | Riparian forest | River created habitats |

| Stilpnia albotibialis | Riparian forest |

List of the bird species endemic to the Cerrado after reviewing their geographical range and taxonomy. We also indicate the sub-areas of endemism to which they are associated and present data on their main habitat and micro-habitat.

| Species . | Area of endemism . | Habitat . | Micro-habitat . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nothura minor | Grassland | ||

| Augastes scutatus | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Campylopterus calcirupicola | Bambuí Karst | Seasonally dry forest | Limestone outcrops |

| Campylopterus diamantinensis | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Columbina cyanopis | Savanna | White sand shrubland | |

| Malacoptila minor | Semideciduous forest | ||

| Celeus obrieni | Semideciduous forest | Bamboo thickets | |

| Pyrrhura pfrimeri | Bambuí Karst | Seasonally dry forest | |

| Geositta poeciloptera | Grassland | ||

| Cinclodes espinhacensis | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Syndactyla dimidiate | Riparian forest | ||

| Asthenes luizae | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | Rock outcrops |

| Synallaxis simoni | Araguaia Floodplains | Riparian forest | River created habitats |

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | Riparian forest | River created habitats | |

| Scytalopus novacapitalis | Riparian forest | ||

| Arremon flavirostris | Semideciduous forest | ||

| Myiothlypis leucophrys | Riparian forest | ||

| Paroaria baeri | Araguaia Floodplains | Riparian forest | River created habitats |

| Stilpnia albotibialis | Riparian forest |

| Species . | Area of endemism . | Habitat . | Micro-habitat . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nothura minor | Grassland | ||

| Augastes scutatus | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Campylopterus calcirupicola | Bambuí Karst | Seasonally dry forest | Limestone outcrops |

| Campylopterus diamantinensis | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Columbina cyanopis | Savanna | White sand shrubland | |

| Malacoptila minor | Semideciduous forest | ||

| Celeus obrieni | Semideciduous forest | Bamboo thickets | |

| Pyrrhura pfrimeri | Bambuí Karst | Seasonally dry forest | |

| Geositta poeciloptera | Grassland | ||

| Cinclodes espinhacensis | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | |

| Syndactyla dimidiate | Riparian forest | ||

| Asthenes luizae | Southern Espinhaço | Campo Rupestre | Rock outcrops |

| Synallaxis simoni | Araguaia Floodplains | Riparian forest | River created habitats |

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | Riparian forest | River created habitats | |

| Scytalopus novacapitalis | Riparian forest | ||

| Arremon flavirostris | Semideciduous forest | ||

| Myiothlypis leucophrys | Riparian forest | ||

| Paroaria baeri | Araguaia Floodplains | Riparian forest | River created habitats |

| Stilpnia albotibialis | Riparian forest |

Using the revised alternative taxonomy identified more species endemic to the Cerrado than using the BSC at the species level because several taxa considered subspecies under the second concept are ranked as independent species under the first concept (for details and references, see Supporting Information, Appendix S2). In contrast, using BSC-subspecies as taxonomic units identified more endemic taxa to the Cerrado than using the revised alternative taxonomy because several currently accepted subspecies were not considered ESUs after revisions. Examples include extremes of individual variation [e.g. Syndactyla dimidiata baeri (Hellmayr, 1911)], arbitrary breaks of a cline [e.g. Nothura maculosa major (Spix, 1825) and Sakesphorus luctuosus araguayae (Hellmayr, 1908)], or hybrid specimens [e.g. Loriotus cristatus nattereri (Pelzeln, 1870)] (Table 1; Supporting Information, Appendices S2 and S4).

Areas of endemism

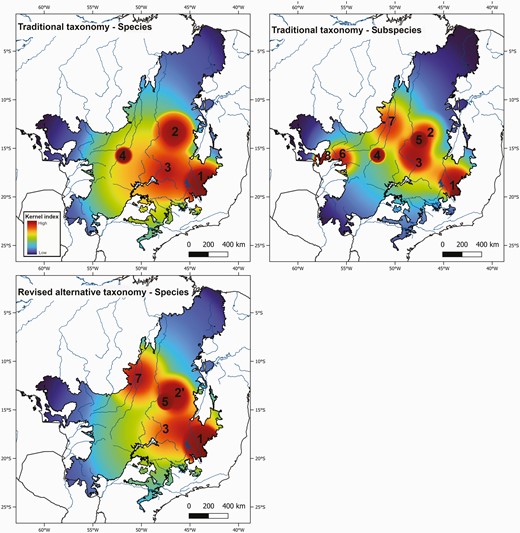

The number of areas of endemism within a region depends on the type of taxonomic units used in the analysis (Fig. 2). Using BSC-species (our database contained 461 occurrences of 11 species), we detected only one area of endemism, the Southern Espinhaço (with the following synendemic species: Augastes scutatus (Temminck, 1824) and Asthenes luizae Vielliard, 1990). We have also identified other areas that harbour only one endemic species. However, these areas cannot be considered areas of endemism because they do not show ‘distributional congruence among two or more taxa’, as required by the definition of an area of endemism adopted here. These areas were the Paranã Valley (Pyrrhura pfrimeri Miranda-Ribeiro, 1920), the Central Brazilian Plateau (Scytalopus novacapitalis Sick, 1958), and the Upper Araguaia River [Sporophila melanops (Pelzeln, 1870)].

Areas of endemism for birds detected in the Cerrado by adopting a geographical interpolation of endemism approach. Note that some of these areas are delimited by only one species and, therefore, cannot be considered an area of endemism as defined in this study. The areas detected were as follows: 1, Southern Espinhaço; 2, Paranã Valley; 2ʹ, Bambuí Karst; 3, Central Brazilian Plateau; 4, Upper Araguaia; 5, Veadeiros Plateau; 6, Mato Grosso; 7, Araguaia Floodplains; and 8, Cáceres.