-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Stephan A Boehm, Heike Schröder, Matthijs Bal, Age-Related Human Resource Management Policies and Practices: Antecedents, Outcomes, and Conceptualizations, Work, Aging and Retirement, Volume 7, Issue 4, October 2021, Pages 257–272, https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waab024

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Due to the demographic change in age, societies, firms, and individuals struggle with the need to postpone retirement while keeping up motivation, performance, and health throughout employees’ working life. Organizations, and specifically the Human Resource Management (HRM) practices they design and implement, take a central role in this process. Being influenced by macro-level trends such as new legislation, organizational HRM practices affect outcomes such as productivity and employability both at the firm and individual level of analysis. This editorial introduces the Special Issue on “Age-related Human Resource Management Policies and Practices” by conducting an interdisciplinary literature review. We offer an organizing framework that spans the macro-, meso-, and individual level and discusses major antecedents, boundary conditions, and outcomes of age-related HRM practices. Further, we propose a typology of HRM practices and discuss the role of individual HRM dimensions versus bundles of HRM practices in dealing with an aging and more age-diverse workforce. Building on these considerations, we introduce the eight articles included in this special issue. Finally, taking stock of our review and the new studies presented here, we deduct some recommendations for future research in the field of age-related HRM.

Demographic change is affecting the size and age composition of the workforce in most industrialized countries, and there is ample evidence that this will cause societal and economic challenges for nation-states, organizations, and individuals alike (Kulik et al., 2014; OECD 2021). These challenges include but are not limited to the sustainability of social security and health care systems, changes to labor productivity and the availability of skilled labor as well as changes to patterns of individual consumption and savings (Bloom et al., 2015). There are significant interdependencies in how actors at different levels respond to and deal with such challenges. For example, nation-states are already adapting welfare systems and are creating incentive structures to compel individuals to postpone retirement and to extend their working lives. This is in order to create personal wealth to finance increased longevity as well as to continue paying into social security systems. As individuals are compelled, or sometimes forced, to postpone retirement (Hofäcker et al., 2016), this also impacts organizations that employ them to satisfy work demands and to stay competitive. Employer practices therefore effectively take the center stage in facilitating or hindering an extended working life agenda. However, as recently argued in this journal, there is a dearth of research that investigates how employer practices help individuals cope with extended working lives and how this changes depending on national social welfare and financial incentive structures (Henkens, 2021).

This special issue addresses this growing scholarly interest to investigate more fully the need for, design, implementation, and effects of age-related Human Resource Management (HRM) policies and practices that allow individuals to extend their working lives. There is already an indication that age-focused HR bundles are instrumental in fostering older workers’ employability and motivation, and hence influence workers’ work-retirement transition decisions (Loretto & White, 2006; Naegele & Walker, 2011). In addition, age-specific HR practices have been proposed as being beneficial for the management of an aging and more age-diverse workforce (Boehm & Dwertmann, 2015; Boehm et al., 2014). However, more clarity is needed on the potential dimensions of age-related HR practices (Kooij et al., 2010, 2014), and how they compare to other forms of HR bundles such as high-performance work systems (Combs et al., 2006) or to individualized HRM systems in predicting important outcomes such as employee engagement, productivity or well-being (Bal et al., 2013; Bal et al., 2015; Kooij & Boon, 2018). This special issue aims to expand on this knowledge.

This introductory article to the special issue offers a narrative review of the age-related HRM literature to date and, in line with Henkens (2021), situates this discussion within a multi-level framework to evaluate whether and how age-related HR practices are designed based on macro-, meso- and/or micro-level influences. This is relevant because firm-level policies might follow institutional change pressures, including those related to welfare state and pension regimes, and can therefore be considered path-dependent (Muller-Camen et al., 2011). However, firm-level actors might have a certain level of liberty to navigate such institutional pressures and implement HR policies that diverge from the institutional path (Schröder et al., 2014). We, therefore, suggest that meso-organizational-level factors, including strategy, structure and organizational culture, and competitive pressures shape the design of HRM as well (Farndale & Paauwe, 2007).

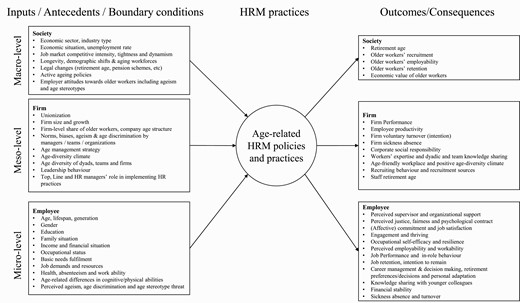

We start our paper by reviewing the literature. This review is organized using a multi-level framework as outlined in Figure 1 below. We then proceed by discussing dimensions and conceptualizations of age-related HRM policies and practices focusing on individualized age-related HRM policies and practices as well as bundles of age-related HR policies and practices. We then introduce the articles contained in this special issue and situate them in our multi-level framework. Lastly, based on our narrative literature review and the articles included here, we identify research gaps in the literature and suggest areas of further research.

An organizing framework for age-related HRM policies and practices own illustration.

An organizing framework for age-related human resource management policies and practices

In the following three sections, we develop and present an organizing framework, summarizing and integrating major antecedents and boundary conditions of age-related HRM policies and practices on the one hand, while also shedding light on the most important outcomes of these practices on the other hand. Figure 1 displays this framework and offers a summary of exemplary sub-topics and constructs studied regarding the antecedents and outcomes of age-related HRM.

Macro-level antecedents and outcomes of age-related HRM practices

Macro-level antecedents of age-related HRM are based on national and international political, societal, social welfare, and economic policies and processes. Using economic incentive structures, the state has influenced organizational policy and, by extension, HRM. For example, during times of persistent unemployment in Europe between the 1970s and 1990s, nation-states incentivized the use of early retirement schemes to externalize older workers from the labor market and to create jobs for younger unemployed individuals (Blossfeld et al., 2006), a rationale whose validity and effectiveness remains contested (Böheim 2014). This early retirement trend was actively supported and promoted by social partners (Flynn et al., 2013), and allowed organizations to externalize presumably underperforming, under-skilled, and/or expensive human resources (Hofäcker et al., 2016) and to manage job attrition caused by industrial transformation (Walker, 1998). Furthermore, societal stereotypes held about older workers have been found to affect organizational HRM (Posthuma & Campion, 2009) including hiring decisions (Abrams et al., 2016).

However, it is now widely recognized that demographic change and population aging will cause significant economic and societal challenges for states, organizations, and individuals (Harper, 2014; Kulik et al., 2014). These include implications for the long-term sustainability of national social security schemes such as pension and health care systems (Bloom et al., 2015). To maintain the financial viability of welfare systems, policymakers have attempted to counter negative (financial) implications due to population aging and early retirement. For example, the European Union set targets for the labor market participation of those aged 55 to 64 and to postpone retirement timing by five years by 2010 (von Nordheim, 2004). Furthermore, national governments started to abolish state-financed early retirement pathways, for example in Germany and Austria (Schmidthuber et al., 2021), and now increasingly aim to extend individuals’ working lives by postponing or by abolishing the compulsory national retirement age, for example in the United Kingdom (Flynn & Schröder, 2018). Also, European Union members transposed EU-initiated anti-age discrimination legislation into national law in order to make it unlawful to discriminate against individuals in employment because of their biological age (Sargeant, 2008). These changes to public and social policy have affected organizational HRM, which often had to comply to be more inclusive for the older workforce (Schröder et al., 2014).

Meso-level antecedents and outcomes of age-related HRM practices

Based on these changes and developments at the macro level (i.e., societal level), organizations have reacted at the meso-level. While doing so, a number of important triggers and boundary conditions have affected firms’ decisions and actions and particularly the design and implementation of age-related HRM practices. The first cluster concerns firm-level demographic factors such as organizational size, level of unionization, or the age structure of the company. For instance, Segel-Karpas et al. (2015) as well as Mulders and Henkens (2019) assessed the prevalence of age-related HR practices in the United States and in the Netherlands and found evidence that factors such as organization size, anticipated growth, focus on internal labor markets, as well as the degree of unionization, all make it more likely that firms employ an active-aging strategy including related HRM practices.

Another important line of research investigates the effects that existent age norms, age biases, and age discrimination play for the establishment of age-related HRM at the firm level. Most of these studies find that ageism of managers, teams, and organizations makes it more likely that firms engage in retirement-or demotion-oriented practices while not perceiving older workers as promising targets of recruitment, training, or further career development (e.g., Goldberg et al., 2013; Lazazzara & Bombelli, 2011; Mulders et al., 2017; van Dalen & Henkens, 2018). A related, yet distinct stream of studies sheds light on the role of supportive climates (e.g., age diversity climate) for the implementation of age-related HRM in firms (e.g., Boehm & Dwertmann, 2015; Burmeister et al., 2018; van Dam et al., 2017; van Solinge & Henkens, 2014). In contrast to the aforementioned studies on the role of ageism and stereotypes, this line of research typically identifies positive relationships with age-related HRM, either as antecedents, moderators, or outcomes of age-friendly or age-inclusive HRM practices.

Finally, another body of theoretical and empirical work studied the role of top, line, and HR managers for the design, implementation, and effectiveness of age-related HRM. Examples of this stream are studies by Furunes et al. (2011) who found the decision latitude of managers to be an important predictor of age management or by Principi et al. (2015) as well as Lazazzara et al. (2013) who both showed that HR managers’ own age plays a role for attitudes towards older workers as well as the implementation of early retirement versus age management initiatives.

Firm-level outcomes of age-related HRM typically include performance-related constructs such as firm performance (e.g., Bieling et al., 2015; Kunze et al., 2013), employee productivity (e.g., Göbel & Zwick, 2013), return on assets (e.g., Ali & French, 2019), turnover (intention) (e.g., Boehm et al., 2014; Stirpe et al., 2018) and firm-level sickness absence (e.g., Ybema et al., 2020). In addition, various studies investigated knowledge-oriented constructs such as workers’ expertise (Calzavara et al., 2019) or dyadic and team knowledge sharing (e.g., Burmeister et al., 2018; Sammarra et al., 2017) as well as aspects of an age-friendly workplace (e.g., Eppler Hattab et al., 2020). In sum, most of the studies hypothesize and find that age-related HR practices contribute towards desirable outcomes while attenuating negative ones.

Micro-level antecedents and outcomes of age-related HRM practices

Finally, we turn to the micro-level of analysis, mainly investigating the role of employees in the implementation of age-related HRM. Here, comparable to the firm level, a first cluster of studies focuses on employees’ demographic characteristics and their role for age-related HRM. The first, and by far most investigated dimension is employees’ own age. These studies typically explore employees’ age, life stage, or generational membership as a moderator of HRM-outcome relationships. Building on theories such as work adjustment (Baltes et al., 1999), fit with one’s work (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005), conservation of resources (Hobfoll, 1989, 2011), socioemotional selectivity (Carstensen, 1991, 1995), regulatory focus (Higgins, 1997), or successful aging (Schulz & Heckhausen, 1996; Zacher, 2015), authors usually argue that certain HRM practices are more relevant for one age group compared to its effects on other age groups. For instance, Bal and de Lange (2015) showed that flexibility practices enhance work engagement for younger employees, while they contribute to job performance for older employees. Drabe et al. (2015) found that older employees’ job satisfaction is mainly driven by good relationships with colleagues, while for younger employees, income, advancement opportunities, job security, and having an interesting job seem to matter more. In addition, using SHARE data from 12 European countries, Barslund et al. (2019) showed that older employees’ level of job satisfaction is generally so high that HR policies can hardly foster it further. Another example is the work by Kooij and her colleagues (e.g., Kooij et al., 2010; Kooij et al., 2013) who repeatedly showed both meta-analytically and in field studies that the association between maintenance HR practices and work-related attitudes (e.g., well-being, commitment, job satisfaction, and performance) strengthens with age while the association between development HR practices and work-related attitudes weakens with age.

Gender, as a second demographic characteristic of employees, was mainly investigated as a control variable, however, certain studies put a focus on it, exploring the role of age-related HRM particularly for older female workers (e.g., Earl & Taylor, 2015). Further studies explored age together with further employee characteristics such as education, position, tenure, or job status (e.g., Hennekam & Herrbach, 2013; Shen, 2010; Sobral et al., 2020) with the goal to either investigate how these characteristics impact employees’ satisfaction with age-related HRM or how age-related HRM practices take effect in the different groups.

Moreover, an important line of research shed light on the role of employees’ health (e.g., Furunes et al., 2015; Winkelmann-Gleed, 2012), work ability (Lazazzara et al., 2013) as well as potential differences in cognitive and physical abilities (e.g., Fisher et al., 2017). One sub-stream of these studies took an employee perspective and focused on retirement decisions as the central outcome. Clearly, good health makes it more likely that employees postpone retirement, yet also those with less positive health perceptions seem to benefit from age-related HRM which can partly make up for or protect remaining levels of work ability (e.g., Furunes et al., 2015). The other sub-stream investigated which role employees’ health plays for the application of HRM practices (i.e., whether older employees with poor health have a diminished chance to get access to training and further career development, which often seems to be the case; e.g., Lazarra et al., 2013).

Dimensions and conceptualizations of age-related hrm policies practices

Besides antecedents and outcomes of age-related HRM, a main focus of research has naturally been on the practices and policies themselves. When studying the relevant literature in more detail, different scholarly and practical approaches become apparent which we strive to organize into a theoretical framework.

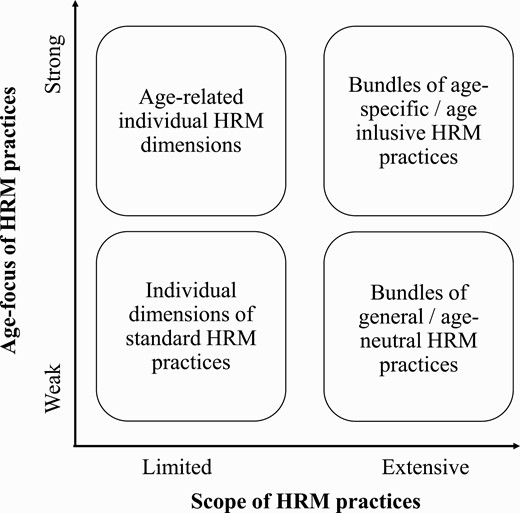

We propose a two-dimensional framework which is displayed in Figure 2. The first axis describes if HRM practices are studied regarding limited, individual dimensions (e.g., recruiting; rewards and compensation; career development, etc.) or in an extensive, integrated manner, proposing and testing bundles of HR practices. The second axis describes if the respective HR practices are either age-neutral (i.e., designed and implemented without referring to age) or age-specific and have a strong focus on age in the design of a practice (i.e., targeted to actively manage age as a diversity characteristic in an organization). Such age-specific practices can be further differentiated into practices targeting specifically older employees and those which are designed as age-inclusive (i.e., targeting all age groups with specific offerings for younger, middle-aged, and older employees). We will review and offer examples of studies taking these perspectives in the following paragraphs.

A typology of age-related HRM policies and practices own illustration.

At this point, we acknowledge that further dimensions exist to cluster and describe HR practices, such as a differentiation between the employee and employer perspective (i.e., the role of informants about the presence of HRM practices; Gerhart et al., 2000; Gerhart et al., 2000), or a differentiation regarding espoused and actually implemented HR and diversity practices (Nishii et al., 2018; Nishii & Paluch, 2018). Such dimensions can and should be used to further refine the model we offer here.

Individual dimensions of age-related HRM practices

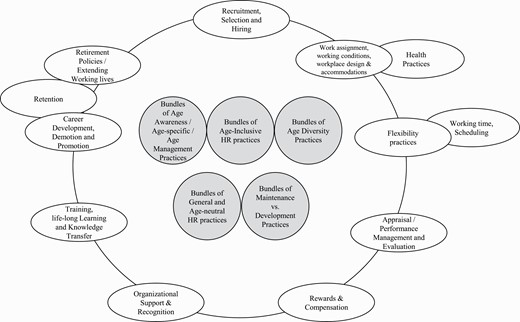

We start by reviewing studies that focused on one or multiple of such individual HR practices and explored their potential to positively impact employees’ performance, job attitudes, and work ability. Figure 3 displays both the individual practices in the outer circle and the various bundles in the center.

Dimensions and bundles of age-related HRM policies and practices own illustration.

Following a typical employee life-cycle, we start with recruitment, selection, and hiring (see top of Figure 3). For many years, organizations were used to recruit primarily younger employees, often due to age bias and stereotypes regarding the skills, motivation, and work ability of older employees (Loretto & White, 2006; Posthuma & Campion, 2009; Riach, 2009). Recently, however, triggered by factors such as a potential lack of younger job candidates and the retirement of large cohorts of older generations (Michaels et al., 2001; Bal et al., 2015), more organizations seem open to widen their search focus and redefine talent (Armstrong-Stassen & Templer, 2005). Fisher et al. (2017) study on the selection of older employees offers an important contribution in this regard as it integrates the bias/stereotyping and recruitment literatures and offers a framework explaining how age-related differences in cognitive and physical abilities as well as changes in personality and work motivation across the life span might impact selection procedures. For organizations, this knowledge is essential if they intend to set up inclusive, bias-free recruiting strategies that provide equal opportunities for all age groups. Another interesting example for this line of research stems from Mulders et al. (2017) who studied the moderating role of top managers’ age-related workplace norms for the recruitment and retention practices of older workers and found nuanced effects for different stages in the employee life cycle (i.e., before and after the normal retirement age). This study points to the need to study relevant boundary conditions for the planning and implementation of HRM practices for an aging workforce.

Following Figure 3 clockwise, we turn to the field of work assignment, working conditions, workplace design, and potential accommodations. It is a well-known fact that employees’ health and work ability typically change over the lifespan. For instance, there is evidence that persons’ sensory (auditory and visual senses), motor (e.g., physical strength), and cardiorespiratory functions tend to decline with age (Ilmarinen, 1994, 2001; Kemper, 1994; Robertson & Tracy, 1998; Robinson, 1986; Spirduso & MacRae, 1990). Consequently, the majority of impairments and disabilities develop over the course of a lifetime (Freedman et al., 2002; Ilmarinen, 1994, 2001; Vita et al., 1998). These, in turn, are a main predictor of older workers’ early retirement decisions (Mein et al., 2000) and a source of performance differences between younger and older workers (McCann & Giles, 2002). Therefore, to accommodate chronic illnesses and disabilities is an important dimension of an age-specific HRM strategy (Boehm & Dwertmann, 2015; Brzykcy et al., 2019). Most of such practices strive to ultimately improve the person-job fit between the aging employees’ skills and remaining abilities and the demands of the respective role (Kensbock et al., 2017; Mulders & Henkens, 2019; Truxillo et al., 2012). An example of a study pursuing this research is Göbel and Zwick (2012) who showed that the relative productivity of older workers is significantly higher in organizations that provide either specific equipment of workplaces or age-specific jobs for older employees. More recently, Fasbender and Gerpott (2021) showed that accommodation practices strengthen the positive relationship between older workers’ occupational self-efficacy and knowledge sharing with younger colleagues.

Moreover, we want to turn to an HRM dimension closely related to accommodations, namely, health practices for an aging workforce. As Mulders and Henkens (2019) showed with data from 1,296 Dutch employers, health practices such as promoting a healthy work-life balance, providing healthy working conditions and supporting a healthy lifestyle are today more common in medium and large organizations compared to small firms. Clearly, for small organizations this is an important area of future development as the challenges related to health (including psychological health) are likely to increase in the future, calling for an active role of organizations and leadership (Brzykcy et al., 2019; Kensbock & Boehm, 2016).

Next, we turn to the fields of flexibility practices and working time and scheduling in particular. While the importance of flexible work practices for employees has been discussed long before the worldwide Corona pandemic, it has become the “new normal” for a large share of office workers in the past year (Rofcanin & Anand, 2020). For an increasingly age-diverse workforce, flexibility practices might be particularly beneficial as they align with the idea of “aged heterogeneity” (Nelson & Dannefer, 1992) which argues that when people become older, they become more heterogeneous. This should also be the case with regard to workplace preferences and behaviors (Bal & Boehm, 2019; Kooij et al., 2008), including the management and use of temporal and spatial flexibility. Firms that manage to address these needs through dedicated flexibility practices should have an advantage in securing the long-term motivation, performance, and work ability of all age groups. An illustrative example for this dimension is Bal and de Lange’s (2015) work on the interplay of flexibility HRM and employee age and their effects on employee engagement and job performance. Using a longitudinal design and collecting data in 11 countries, they found that flexibility HRM was important for younger workers to increase engagement, while for older workers it enhanced their job performance. In addition, Cahill et al. (2015) demonstrated in a randomized field experiment that newly introduced workplace flexibility arrangements positively influenced employees’ intention to remain with the organization until retirement.

Job appraisal, performance management, and evaluation is another important HR dimension to be discussed here. For organizations, this seems to be a particularly challenging dimension as wide-spread age stereotypes about older workers (e.g., regarding their inferior performance or increased resistance to change; Cadizet al., 2017; Posthuma & Campion, 2009) can directly affect their performance evaluation, even though most of these stereotypes lack factual bases (Kunze et al., 2013; Ng & Feldman, 2008). Prior research indicated that specific forms of performance management, such as forced ranking systems, might be particularly detrimental for older employees as they might trigger social comparison processes that again rely on stereotypes (Osborne & McCann, 2004). Organizations are therefore challenged to come up with fair performance appraisal systems, particularly for older employees that do not solely rely on the perception of the supervisor (Waldman & Avolio, 1986). Lee and Kim (2020) presented such a system in the form of multisource feedback (i.e., 360-degree feedback) from various stakeholders such as subordinates, peers, supervisors, and customers and showed that this approach helps to improve (i.e., moderates) the age diversity-relational coordination link, which in turn, relates positively to firm performance.

Rewards and compensation are to be considered next as a fair performance evaluation is a necessary, yet not sufficient step towards fair rewards and compensation for all age groups. Based on theories such as social exchange (Blau, 1964) and the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), researchers and practitioners are well aware that in order to secure employees’ long-term motivation, they have to be rewarded and compensated according to their performance. By doing so, organizations can contribute towards establishing a sustainable employee-employer relationship (Eisenberger et al., 2001) and prevent attrition and turnover. As an example of this line of investigation, we point to Bieling et al. (2015) who showed that HR managers implement both age-specific appraisal and compensation practices as a response to competitive job markets which, in turn, contribute to organizational performance. In addition to this firm-level approach, Smit et al. (2015) studied the potentially different preferences that various age groups have in the workplace and found that older employees above 47 regarded overall compensation as the most important factor while younger and middle-aged workers rated performance management and development and career opportunities as significantly more important.

Further, practices related to organizational support and recognition should be mentioned as these complement the aforementioned “hard” and “exchange-oriented” factors of rewards and compensation. For instance, Mountford (2013) highlighted that offering a supportive work environment in which older employees’ skill and abilities are recognized is a key strategy in retaining older workers, even under the conditions of physically demanding and poorly paid work. Similar results were obtained by Hennekam and Herrbach (2013) who showed that HRM practices related to recognition and respect are a key driver of older employees’ affective commitment and job performance.

Next, we turn to the dimension of training, life-long learning, and knowledge transfer. Historically, training in organizations was often targeted at young employees in their early career stages, as firms expected a longer period of amortization (Van Yoder & Goldberg, 2002). In addition, widespread stereotypes existed that older employees had less potential for development (Duncan, 2001; Wrenn & Maurer, 2004) and were less trainable than their younger colleagues (Brooke & Taylor, 2005; Rosen & Jerdee, 1989). Consequently, in the past, older employees had less access to training (Barth et al., 1993; Rix 1996; Taylor & Urwin, 2001). In the past decade, however, a comparably rich body of literature focused on training as a specific measure to manage an aging workforce. Examples of this work are studies by Furunes et al. (2015), Hermansen and Midtsundstad (2015); Lazazzara and Bombelli (2011); Lazazzara et al., 2013), Martin et al. (2014), and Naegele and Walker (2011). Some of the main findings of this research are that stereotypes regarding the training potential of older employees still exist, yet that fostering life-long learning and training older employees appropriately is key to keep up their motivation and performance and postpone their retirement. In addition, certain modifications of training practices and methods have been proposed by the literature, for instance, the use of modeling (where learners observe another person executing a behavior) and active participation (where learners perform the focal task themselves) instead of traditional lecturing. In a meta-analysis including 41 studies, Callahan et al. (2003) found that all three lecturing types, as well as two instructional factors (pacing and group size), explained unique variance in observed training performance for older participants. Consequently, an effective training for older employees might use a multi-method approach, combining all three types of knowledge transfer. This, however, seems advisable for younger learners as well.

Last, we turn to three related fields—practices related to career development, demotion, and promotion, practices related to retention, as well as practices focusing onretirement policies vs. extending employees’ working lives. All of these practices have in common that they try to actively manage employees’ careers over their lifespan including the transition to retirement for older employees. For an active aging strategy at both the societal and meso-level of analysis, career management is of utmost importance as it can directly contribute to extending employees’ working life and achieving a higher factual retirement age—two primary goals for most governments these days (Flynn, 2010). Various studies have shed light on the complex interplay of age, career self-management, as well as organizational career management and found that both synergistic and compensatory effects can be present, yet an active career management seems important for every age group (Jung & Takeuchi, 2017). A further interesting study stems from Dello Russo et al. (2020) who focused on the role of developmental practices for employees’ external employability over the work-life span. They shed particular light on the interplay of HR developmental measures with age norms, age stereotypes, and age meta-stereotypes and found that developmental HR practices could buffer these negative relationships. Further work on this dimension, particularly on the role of developmental practices, was conducted by authors such as Bal and Dorenbosch (2015) and Innocenti et al. (2013). In line with frameworks such as socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, 1991, 1995), they found that such practices are often more appreciated by younger employees as these might have more pronounced career ambitions. Further building on this assumption, the practice of demotion of older employees was investigated by scholars such as Mulders et al. (2015) and van Dalen and Henkens (2018). Although managers believe that demotion could be a fair reaction in the case of older employees’ missing motivation and related performance drops, they typically shy away from this practice due to potentially negative staff reactions (van Dalen & Henkens, 2018). They are probably right with this assumption as Visser et al. (2021) demonstrated that demotion shows a negative relationship with older employees’ job satisfaction while this is not the case for phasing-out arrangements. Finally, we want to turn to organizational policies fostering retention and work-life extension versus offering exit policies. In this respect, van Dalen et al. (2015) showed in a study including 3,638 organizations from six European countries that employers often use dual approaches, moving “older workers either upwards (e.g., by encouraging career development and training) or outwards (by promoting early retirement)” (p. 814). While both strategies are used, organizations seem to use exit policies far more frequently than development measures, potentially risking the overall goal of extending employees’ working lives.

Bundles of (age-related) HRM practices

In the next sections, we turn to the right side of Figure 2, and the center part of Figure 3, where we discuss bundles of both general and age-focused HRM practices. In contrast to the aforementioned individual dimensions, bundles of HR practices are intended to enfold their effect in an interrelated and internally consistent manner (Mac Duffie, 1995), such that they reinforce each other towards the accomplishment of certain organizational goals (Guest et al., 2004; Toh et al., 2008).

Age-neutral HRM practices

We first turn to work investigating the role of bundles of general, respectively age-neutral HRM practices. Such work is often rooted in research on existent HR bundles, such as high-performance work practices (HPWPs; Combs et al., 2006; Huselid, 1995) or high involvement work practices (HIWPs; Guthrie, 2001; Lawler, 1988) which both intend to foster employees’ levels of knowledge, skills, and motivation, thereby reinforcing employees’ job performance and attachment to the firm (e.g., Appelbaum et al., 2000).

Research on HPWPs or HIWPs does not typically investigate the role of employees’ age for the effectiveness of such practices but assumes that HPWPs/HIWPs are valuable for all employees due to their internal consistency and fit with the organization’s strategy (Kaufman & Miller, 2011; Youndt et al., 1996). Still, they are offered as one way to deal with an aging workforce. For instance, at the micro-level, Salminen et al. (2019) found that HIWPs were negatively related to early retirement intentions and positively correlated with intentions to continue working after retirement age. At the firm level, von Bonsdorff et al. (2018) showed that HIWPs were positively related to company work ability.

Yet, there is also research indicating that an age-specific approach to studying HPWP might be of value. For instance, Stirpe et al. (2018) explored if HPWP contribute to the retention of staff and found that this is the case for younger, yet not for older employees. For them, HPWPs seemed to even impair retention. Consequently, in the next section we turn to research that built on the notion that age might be an important moderator of the HPWP-employee well-being-link.

Maintenance versus development HRM practices

Building on lifespan theories such as the selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC) framework (Baltes et al., 1999) as well as social-psychological regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997), it was particularly Kooij et al. (2010, 2011, 2013) who proposed that as employees’ motives change over their work-life, so would their HR-related needs and preferences. Specifically, Kooij et al. built on the above-discussed frameworks of high commitment HR practices and categorized these practices into theoretically meaningful HR bundles, coined as development (promotion) versus maintenance (prevention) HR practices. They largely found support for their hypothesis that development practices (e.g., providing training) contribute more strongly to younger workers’ well-being and work motivation (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment, work engagement, etc.), while maintenance practices (e.g., providing job security) are more valued by older employees (Kooij et al., 2010, 2013). This view was also taken up by other scholars (e.g., Korff et al., 2017; Veth et al., 2015) with largely similar results.

Finally, more fine-grained conceptualizations of such practices were proposed as well (e.g., a classification into accommodative, maintenance, utilization, and development HR bundles for older employees; Kooij et al., 2014). Only recently, Pak et al. (2020) showed in a sample of more than 12,000 employees that developmental practices seem to have the most desirable effects on work ability and preferred retirement age while maintenance, accommodative, and utilization practices were negatively related with work ability. This more negative view of maintenance practices is also echoed by Veth et al. (2019) who found that maintenance practices were negatively associated with outcomes such as work engagement, independently of employees’ age. One takeaway from this research might be that every employee, independent of their age, values if the organization believes in their talents and invests in them by providing developmental opportunities instead of switching to a fading-out mode.

Age management practices

Next, we discuss HRM practices based on age awareness, also labeled as age management practices. The core idea of such bundles is to adapt general HR practices in a way to accommodate both the needs of the individual aging worker as well as of an aging workforce in firms or whole countries (e.g., by conducting age assessments, fostering adaptations of the recruiting practices, offering special trainings to older employees, etc.).

Early and influential work on such age-specific bundles of HRM stems from Naegele and Walker (2011) who recommended a combination of various dimensions of age management including adaptations related to job recruitment, learning, training, and life-long learning, career development, flexible working practices, health protection/promotion and workplace design, redeployment as well as employment exit and transition to retirement. This approach is largely consistent with the work of Armstrong-Stassen (2008), Armstrong-Stassen and Lee (2009), Armstrong-Stassen and Templer (2006), and Armstrong-Stassen and Ursel (2009), who focused on the Canadian context and proposed flexible working options, training and development, job design, recognition and respect, performance evaluation, compensation, and pre/postretirement options as typical components of age management practices. Other scholarly work, such as Patrickson and Hartmann’s (1995) study of the Australian context identified and built upon similar clusters. Further work following this approach stems from Fuertes et al. (2013) who studied age management in small- and medium-sized enterprises and found that negative age stereotypes can be a stumbling block in implementing age management. Moreover, Furunes et al. (2011), Principi et al. (2015), and Tonelli et al. (2020) studied age management in the Norwegian, Italian, and Brazilian contexts and found that (HR) managers’ attitudes are a key factor for implementing age management and fostering older workers’ retention.

In addition, important studies on this topic were conducted by Hennekam and Herrbach (2015) as well as Ollier-Malaterre et al. (2013). Both author teams compared the emergence and potential effects of age-neutral versus age-related HRM. More specifically, Ollier-Malaterre et al. (2013) explored the institutional logics behind the selection of an age-neutral versus an age-awareness strategy and found that in a sample of 420 US organizations, a strong compliance logic was associated with higher density of age-specific practices while a strong strategic logic is associated with a greater prevalence of age-neutral HRM. Hennekam and Herrbach (2015) focused on outcomes of such practices and found that HRM practices designed for aging employees can be perceived as a social stigma by older workers which threatens a positive social identity. At the same time, older workers did appreciate that these practices took care of their specific needs.

Taken together, an active age management that adapts HR practices to the needs of aging employees seems to bring advantages to both firms and individuals. In contrast to just adapting individual HR dimensions, such a holistic and integrated approach seems better suited to successfully respond to the needs of aging employees in the workplace (Naegele and Walker, 2011; Walker, 1999). At the same time, however, these positive aspects of age-specific HRM do not come for free. In fact, not only “standard HRM practices are firmly […] grounded in ageist assumptions concerning the capacities, potentiality, and contributions of both younger and older workers” (Taylor & Earl 2016, p. 14), but also age-specific HRM practices might be based upon and fuel age stereotypes. Therefore, organizations seem well advised to critically check which age-related HR practices they design and how they communicate the need to do so together with the implementation of such practices.

Bundles of age-diversity practices

Another, yet smaller line of research has shed light to age-diversity practices (i.e., HRM practices that are intended to foster a smooth collaboration between different age groups in the workplace). As research on age-diversity has shown (De Meulenaere et al., 2016; De Meulenaere & Kunze, 2020; Kunze et al., 2011, 2013, 2021), age is no exception from other diversity categories in its potential to cause conflicts between perceived in- and out-groups in the workplace (Boehm & Dwertmann 2015; Van Knippenberg & Schippers 2007). Building on this notion, Ali and French (2019) showed that age-diversity practices in firms are positively related to CSR. Bieling et al. (2015) found a significant link from age-diversity practices to employee welfare, which in turn related to perceived organizational performance and objective employee productivity. Further, Kulik et al. (2016) studied the effects of stereotype threats (e.g., having a young manager or working in a young workgroup) on older workers’ engagement and found that both diversity conscious mature-age practices, as well as diversity blind high performance practices, can help to buffer such negative stereotype threat effects. In sum, we have some preliminary evidence to believe that age-diversity practices can indeed be helpful in managing raising levels of age-diversity in the workplace.

Bundles of age-inclusive HRM practices

Finally, we want to turn to age-inclusive HRM practices, a term coined by Boehm et al. (2014). They argued that companies should introduce bundles of HRM practices and policies that do not focus solely on older employees but equally foster all age groups’ (1) knowledge, skills, and abilities, (2) motivation and effort, as well as (3) opportunities to contribute. As dimensions of these practices, they proposed age-neutral recruiting policies, equal access to training for all age groups, age-neutral career and promotion systems, initiatives to educate managers about leading age-diversity in the workplace, as well as the promotion of an age-inclusive corporate culture. As shown in a sample of 93 German companies, such age-inclusive HR practices contribute to the development of an organization-wide age-diversity climate, which in turn was directly related to increased perceptions of social exchange and indirectly to firm performance and employees’ aggregated turnover intentions. In the meantime, various studies followed this conceptualization and further explored the potential of age-inclusive HRM. For instance, Burmeister et al. (2018) studied 159 age-diverse co-worker dyads from China and Germany and found that perceived age-inclusive human resource practices were positively associated with knowledge sharing and receiving through age-diversity climate. Kunze et al. (2015) operationalized it on the firm-level and showed that there is an interplay between age-inclusive HR practices and work-related meaning as predictors of employees feeling subjectively younger than they are, which in turn, contributes to higher goal accomplishment and company performance. Taken together, age-inclusive HR practices might be a promising tool to manage aging workforces, both at the dyadic/team-level as well as on the firm-level.

Overview of the special issue

The eight articles published in this special issue span the macro-, meso- and micro-level of analysis and investigate the emergence and effects of both individual practices and bundles of age-related HRM practices.

The first article of this special issue (i.e., Ball & Flynn, 2021) investigates the role of unions in the UK in extending the working life of older employees. Using qualitative data from focus group discussions with union representatives, the study argues that unions engage in a double strategy of collaborating with inclined employers to realize age-friendly workplaces while lobbying with its members to secure existent pension and retirement rights. The study further explores which different emphases the unions put regarding the advancement of an active aging strategy including the assessment of workforce demography, promotion of health and safety, skills and competence management, work organization as well as inter-generational approaches. Following the logic of our organizing framework, this work is a nice example of a macro-level study that helps to understand how unions as actors at the societal level react to demographic trends and related changes in legislation by making sense of and contributing to active aging policies. These union responses turn out as antecedents and boundary conditions of the implementation of age-related HRM practices at the lower levels of analyses (i.e., the firm (meso-) and employee (micro-) levels of analysis).

The next six studies of the special issue can be located at the meso- (i.e., firm-) level of analysis. The first of those is van Selm and van den Heijkant (2021) who concentrate on the recruitment of older workers as an individual HR practice. Specifically, they integrate literatures on stereotypes and communication and investigate via an automated content analysis if job advertisements reflect the stereotypes regarding older workers as being warm but less competent. Conducting additional interviews with recruiters, the authors largely find support for their hypothesis that job advertisements targeting older job seekers reflect the assumptions regarding aging employees as being good in soft skills and performing less well on hard skills. On the positive side, the expert interviews suggest that older workers can contribute to firms’ need for a social and responsible workforce. This study at the firm level of analysis illustrates that HR practices are not developed in a vacuum but are often shaped and affected by norms and stereotypes held by top management, supervisors, and HR personnel. Clearly, such biases are a challenge for implementing inclusive HR practices that do not discriminate on the basis of age or other demographic factors.

The second study at the meso-level of analysis is Visser et al. (2021). These authors are also interested in the role of individual HR-practices for older workers, particularly phasing out (e.g., lighter workload or semi-retirement), demotion and training. They use linked organization-department-employee data from the European Sustainable Workforce Survey (ESWS) to study the relationships of these three practices with older workers’ job satisfaction. The study finds that demotion is negatively related to job satisfaction, while phasing out is unrelated and training positively related to this important job attitude. Further, the study sheds light to co-workers’ use of these HR practices as a boundary condition at the firm-level of analysis and finds that co-workers’ use of training is positive for employees’ job satisfaction while co-workers’ demotion and phasing out seem not to matter for employees. Again, these results illustrate that the successful implementation of age-related HRM practices is dependent upon a magnitude of potential moderating variables and it is a particular strength of this study to focus on the role of co-workers which to date have hardly received attention in this respect.

The next study of this special issue takes us into the world of schools and the public sector as a context where early retirement is still practiced rather often. In their comparative mixed-methods case study conducted in two Belgian schools, Brouhier et al. (2021) explored how remedial and developmental HR practices are used by schools to manage older teachers’ careers. Through means of an additional network analysis, the authors find that older teachers hold central positions in their schools and have limited but strong bounds with colleagues. Further, in line with a strength use perspective, older teachers’ knowledge seems to be actively utilized by school principals, however, remedial measures for career management still seem to dominate over developmental practices for this age group.

In contrast to the aforementioned studies that concentrated on one or several individual dimensions of age-related HRM practices, the next three studies investigate bundles of HRM practices and test their potential to help managing the demographic change on the firm level of analysis. The first of those is Garavaglia et al. (2021) who adopted an action research approach to study and facilitate the implementation of age management practices in 31 Italian and Spanish organizations. Their Quality of Aging at Work model is based on a close cooperation of researchers with organizational stakeholders who mutually engage in alternating phases of action and reflection to equip firms with a tailored age management strategy and implementation plan. As the authors demonstrate, this qualitative and quantitative approach seems particularly effective to build awareness in the organization, trigger change in a democratic and holistic manner, and foster autonomy to engage in firm-level age management.

The second study was conducted by Wilckens et al. (2021) who developed and validated the Later Life Workplace Index (LLWI). To come up with their holistic index, the authors conducted three independent studies in both the U.S. and Germany. In its final form, the index consists of 80 items which span nine dimensions including an age-friendly organizational climate and leadership style, work design characteristics, health management, individual development opportunities, knowledge management, the design of the retirement transition, continued employment opportunities, as well as health and retirement coverage. Due to its scientific rigor and its practical applicability, the newly developed scale is a great tool for scholars and practitioners alike who want to assess the status quo of age management in organizations and deduce evidence-based interventions.

Third, Rudolph and Zacher (2021) contributed a study on age-inclusive HR practices to this special issue which spans the meso- and micro-level of analysis. Building on Böhm et al.’s (2014) scale as well as signaling and social exchange theory, the authors test a model linking age-inclusive HR practices to age diversity climate, which in turn is proposed to effect employees’ work ability. A particular strength of this work is the up-to-date methodological procedure, that is, the use of a random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM) which the authors employ to analyze data from 355 employees across six waves. In contrast to other longitudinal methods such as cross-lagged panels models, this new procedure allows to differentiate potential between-person effects, within-person effects, and contextual effects. The authors use this data-analytical strength to show that age diversity climate mediates the impact of age-inclusive HR practices on work ability at the between-, but not at the within-person level of analysis. In other words, employees seem to differ from each other in their perception of age-inclusive HRM and age diversity climate over time, while intraindividual developments are less likely to occur (at least in a short time period).

Finally, the last study of this special issue by Allen et al. (2021) can be located at the micro-level of analysis. Using data from 1,834 workers aged above 55 from New Zealand, the authors study the role of flexible work arrangements in the health-stereotypes-work engagement relationship. Allen et al. find that greater mental health and lower negative stereotypes predict higher work engagement. In addition, more pronounced flexible work practices showed a weak negative association with the perception of negative stereotypes about older workers and reduced the association of negative stereotypes with work engagement. Taken together, this study is a good example of work investigating the potential of a single HR dimension (i.e., flexible work arrangements) for the management of an aging workforce by addressing two age-related challenges, that is, declining health and negative age stereotypes.

Taken together, we strongly believe that these eight articles nicely complement each other and help to spur future research on age-related HRM in both theoretical and methodological ways. In addition, based on the variety of theoretical approaches, investigated practices, collected data, and employed methods, they are a vivid demonstration of the diversity of this young, yet growing and ambitious research field.

Future research directions

Based on the observations we made when reviewing the literature for our organizing framework together with the contributions that the new articles for this special issue make, some avenues for research emerge that aging and HRM scholars might want to address in the future.

First, the literature on age-related HRM practices and policies is rapidly growing in both quantity and diversity. One of the reasons for this might be that the topic of age-related HRM deals with a grand challenge to management of our time (Kulik et al., 2014) and is of relevance to a variety of disciplines including economics, sociology, social policy, gerontology, psychology/organizational behavior as well as HR and health management. Accordingly, a wide variety of theoretical and empirical approaches have been used, published in a broad range of outlets. Consequently, one of the most obvious areas for future research would be to conduct a systematic review, enabling scholars and practitioners alike to get a better overview of the field. We hope that the models and organizing framework we developed here can act as a springboard for such an endeavor. Clearly, recent best practice recommendations for conducting impactful literature reviews should be taken into account (Kunisch et al., 2018).

Second, it was our intention for this special issue to offer a multilevel-framework for age-related HRM which addresses the macro-, meso-, and micro-level of analysis. As our literature review indicates, there is indeed a comparably high number of influential studies on all of these layers. At the macro-level, sociology and social policy-oriented literature dominates, which investigates how HRM practices are shaped through institutional change pressures. Further, at the meso- and micro-level, studies from the fields of organizational behavior and psychology are prevalent which explore how HRM practices can help both firms and affected employees to stay competitive, engaged, and healthy throughout a prolonged working life. Interestingly though, hardly any study tried to fully span these levels, offering a true multilevel approach. Clearly, many studies span two of the levels and test for instance how country- or industry-level factors affect HRM policies and outcomes at the firm-level or how firm-level factors (e.g., norms, stereotypes, leadership behavior) affect outcomes at the individual-level of analysis (e.g., retirement decisions). While such studies are insightful, they still miss important pieces of the overall picture. As Henkens (2021, p. 1) noted in this respect, “organizations are a key player [… and] the crucial link between macro-level government policies and individual-level outcomes for workers”. All three levels influence each other and this is why they have to be taken into account simultaneously to really understand older employees’ workplace behavior including their retirement decisions (Phillipson et al., 2019; Riekhoff et al., 2020). For instance, the basically same age-related HRM practice at the firm-level might still have a different impact on employees’ engagement or productivity as a function of the national or cultural context. Burmeister et al. (2018) point to the role of collectivistic versus individualistic cultures (Hofstede 1980; House et al., 2002) as one example for such country-level differences. Of course, many more seem worthwhile to investigate, including factors such as the existence of a legal retirement age, the role and influence of trade unions, the economic and job market situation, age-norms and expectations, etc. Studies that manage to model in such aspects would be of great value to the field as they might equip decision-makers with a more realistic and holistic assessment of when and under which conditions certain age-related HRM practices are really effective in a specific context.

Third, we still have to better understand how age-neutral, age-specific, and age-inclusive HR practices compare to each other in terms of major antecedents, boundary conditions—and most importantly—effects. To date, most studies have focused on one of these approaches while comparisons between different HR dimensions and/or bundles are rather scarce. In fact, all of these approaches (i.e., age-neutral, age-specific, or age-inclusive) have their places in addressing an aging and age-diverse workforce. As Hennekam and Herrbach (2015) pointed out in one of the few comparative studies, older workers might like the job accommodations that they receive via age-specific HR practices, however, not at the price of being “stamped as old”. Age-inclusive HR practices might be one way to address this dilemma, yet more work is needed to ultimately judge which practices and bundles provide most value to employees and firms dealing with the demographic change in age.

Fourth, we agree with Pak et al. (2019) recent assessment that scholars doing research on age-related HRM could drive the field forward by investing in theory development, the quality of their measures, and the rigor of their empirical designs. Many of these aspects apply to basically all scientific fields, yet they seem to be particularly important for age-related HRM research. As Wilckens et al. (2021) note in their article in this special issue, many of the early studies did not use validated measures of age-related HRM practices. Their work on scale development and the resulting LLWI together with the use of further established scales (e.g., for age-inclusive HR-practices; Boehm et al., 2014) might be of value here. Furthermore, as Pak et al. (2020) note, clearly specified theoretical frameworks should be used and tested to explain the effects of age-related HRM at the various levels of analysis (e.g., the COR, JD-R, SOC, SST, or AMO-frameworks). Finally, strong empirical designs should be employed to investigate if age-related HRM really has a causal effect on the intended outcomes such as performance, health, and late retirement. For this, longitudinal research designs including appropriate statistical modeling procedures seem very valuable. Rudolph and Zacher’s (2021) random intercept cross-lagged panel procedure is a great example for such a method. In contrast to traditionally used cross-lagged panel models, this rather new procedure allows to disentangle the within-person and the between-person/contextual effects, thereby demonstrating which of these effects prevails (Antonakis et al., 2021; Hamaker et al., 2015). In addition, scholars might try to team up with organizations and design and conduct randomized field interventions on age-related HRM practices. Although such research is scarce in the field of age management, it does exist as Cahill et al. (2015) study on the role of randomly assigned workplace flexibility for retirement expectations demonstrates. While such an approach is hard to organize, it would clearly have immense potential for science and practice alike in showing the causal effects that age-related HRM might have for societies, firms, and individual employees.

Conclusion

This introductory article to the special issue offered a narrative review of the literature on age-related HRM policies and practices to date and introduced a multi-level framework to organize this literature. This multi-level framework spans three levels and provides an overview of exemplary topics studied at the societal-, firm- and individual-level of analysis. Further, we offered a conceptual overview of the various approaches taken to study HRM for an aging workforce, differentiating between age-neutral and age-focused HRM practices on the one hand, and individual practices versus integrated bundles on the other hand. After introducing the studies being part of this special issue, we concluded with four recommendations to move the field forward. These include the need to conduct full multi-level studies, comparative studies analyzing the effects of different approaches to age-related HRM, as well as the use of more sophisticated theories, measures, and empirical research designs. In sum, we hope that readers will benefit from the efforts that the special issue authors, reviewers, and editors took to move this exciting field of research forward.