-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elizabeth Barr, Ronna Popkin, Erik Roodzant, Beth Jaworski, Sarah M Temkin, Gender as a social and structural variable: research perspectives from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Translational Behavioral Medicine, Volume 14, Issue 1, January 2024, Pages 13–22, https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibad014

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gender is a social and structural variable that encompasses multiple domains, each of which influences health: gender identity and expression, gender roles and norms, gendered power relations, and gender equality and equity. As such, gender has far-reaching impacts on health. Additional research is needed to continue delineating and untangling the effects of gender from the effects of sex and other biological variables. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) vision for women’s health is a world in which the influence of sex and/or gender are integrated into the health research enterprise. However, much of the NIH-supported research on gender and health has, to date, been limited to a small number of conditions (e.g., HIV, mental health, pregnancy) and locations (e.g., sub-Saharan Africa; India). Opportunities exist to support transdisciplinary knowledge transfer and interdisciplinary knowledge building by advancing health-related social science research that incorporates best practices from disciplines that have well-established methods, theories, and frameworks for examining the health impacts of gender and other social, cultural, and structural variables.

Lay Summary

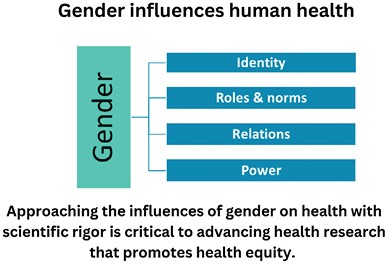

Gender encompasses multiple domains, each of which influences health: identity and expression; roles and norms; relations; and power. This commentary focuses on gender-related research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH); identifies areas of opportunity for future health research efforts on gender; and articulates a vision for the robust, transdisciplinary incorporation of gender as a social, cultural, and structural variable into the NIH research agenda. The NIH vision for women’s health is a world in which the influence of sex and/or gender are integrated into the health research enterprise. However, much of the NIH-supported research on gender and health has, to date, been limited to a small number of conditions (e.g., HIV, mental health, pregnancy) and locations (e.g., sub-Saharan Africa; India). Approaching the influences of gender on health with scientific rigor is critical to advancing health research that promotes health equity.

INTRODUCTION

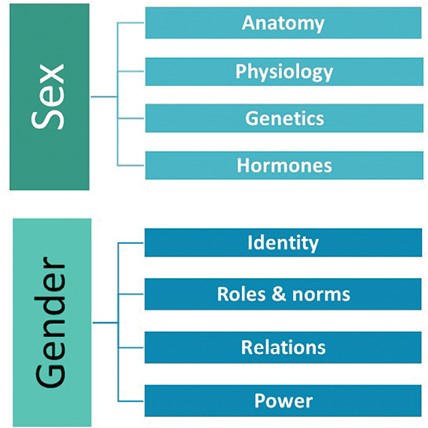

Gender is a multidimensional construct with multiple domains that influence human health: identity and expression; roles and norms; relations; and power (Fig. 1) [1–4]. Gender identity refers to a core element of a person’s individual sense of self and gender expression describes how a person communicates their gender to others through their behavior and appearance. Gender roles and norms are social domains reflecting cultural expectations and perceptions about how a person should behave, act, or express themselves based on their perceived or attributed gender. Gendered relations are interpersonal and intergroup interactions and dynamics, embedded in social structures, and larger systems of power. Power describes the structures and systems of inequity based upon gender that reproduce, shape, and constrain opportunities and experiences for individuals and groups. Other sociodemographic variables, such as race [5] and ethnicity [6]; socioeconomic status [7]; and structural factors, such as state [8] or federal policies [9], interact with gender, highlighting the importance of considering intersectionality [10] in the design, conduct, and analysis of health research [11].

In scientific literature, policy documents, media, and general conversation, gender is frequently conflated with the separate and distinct concept of sex. Sex is a multidimensional biological construct based on traits (sex traits) that include anatomy, physiology, genetics, and hormonal milieu [1]. Foundational work by social epidemiologist Nancy Krieger articulates that, “The relevance of gender relations and sex-linked biology to a given health outcome is an empirical question, not a philosophical principle; depending on the health outcome under study, both, neither, one, or the other may be relevant—as sole, independent, or synergistic determinants” [12]. In other words, sex (a biological variable) and gender (a social, cultural, and structural variable) act both independently of each other and in ways that can complement, enhance, diminish, or negate the other’s influence on health. Well-established bodies of literature in gender and women’s studies, public health, sociology, psychology, demography, epidemiology, and other fields explore the far-reaching effects of gender as a social, cultural, and structural variable. To understand how social systems influence health, the civil, political, economic, and cultural factors that lead to differences in the basic determinants of health—such as access to nutritious food, clean air and water, housing, and safe living conditions—they must be identified, measured, and included in research. Indeed, approaching the influences of gender on health with scientific rigor is critical to advancing health research that promotes health equity. This commentary focuses on gender-related research at NIH; identifies areas of opportunity for future health research efforts on gender; and articulates a vision for the robust, transdisciplinary incorporation of gender as a social and structural variable into the NIH research agenda.

THE INFLUENCE OF GENDER ON HEALTH [NEW AND REORGANIZED SECTION]

As a multidimensional and multi-level construct, gender links individual identity to social and cultural expectations about status, characteristics, and behavior as they are associated with certain sex traits [1]. Each domain of gender has significant impacts on people’s day-to-day lives, career opportunities, family dynamics, and health. Assumptions about gender permeate human interactions, social norms, and structural systems, making a multi-level framework useful for understanding how gender influences health [13].

Gender identity and expression influence individuals’ health. A growing body of research on gender identity and health has focused on transgender and non-binary individuals, but gender identity is also relevant to the health of cisgender individuals. Exogenous hormone therapies—whether used as part for treatment of menopausal symptoms, gender-affirming care [14] or other reasons—as well as with post-mastectomy breast reconstructions [15] are examples of gender identity influencing the health of women. Gender expression can affect musculoskeletal health: women are often encouraged or required to wear and walk in high-heeled shoes which contribute to the increased risk for women of developing osteoarthritis later in life due to excess stress on knee joints [16].

Gender roles can limit girls’ and women’s access to health services [2, 17] and shape patient-provider interactions. Gender bias has demonstrated associations with diagnostic delays among women for diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease [18, 19]. Symptoms that are typical for women have historically been labeled atypical in defining the clinical presentation of serious events, such as myocardial infarction (MI); instead, these events have historically been defined by symptoms more common in men [3]. Gender bias—reflected in part through the centering of men’s symptoms in medical training and textbooks—contributes to misdiagnosis of MI and lower survival for women compared to men for a variety of conditions [20]. In other health contexts, gendered power relations affect the dismissal of physical pain symptoms as emotional, psychological, or even as hysterical when reported by women [21], and intersectional analyses reveal stark race- and gender-based differences in pain management [22]. Norms of masculinity also shape men’s and boys’ health, healthcare seeking, relationships, and exposure to violence [23–27].

Gendered power relations can exacerbate health risks [28], particularly for multiply-marginalized women [5, 29], and structural sexism [4] interacts with other structural determinants [30] to perpetuate gendered health inequities [31]. On a global scale, pervasive gender inequality negatively impacts the health of women [32, 33]. In addition to the influence of gender on the social determinants of health and access to healthcare, gender roles, relations, and power dynamics influence healthcare delivery and practices, with gender inequality contributing to disparities in healthcare for women [2]. For women, exposure to structural sexism is associated with the diagnosis of chronic conditions, worse self-rated health, and worse physical functioning [34].

Structural sexism not only influences health, but also impacts who provides healthcare for women and participates in research on women’s health. The healthcare workforce is predominantly made up of women, and clinicians who are women are more likely to provide healthcare to women [35]. Yet clinicians who are women face inequities that include discrimination, lower compensation, and fewer opportunities for advancement and leadership [36, 37]. Lower reimbursement rates for many female-specific procedures also perpetuate a lower status for clinicians who provide care to women [37–39]. Similarly, women’s health research is also more often performed by women than men and has been shown to be less publishable—and when published, less impactful—than research focused on men [40]. While in medicine, women’s health has traditionally been equated with reproductive health, persistent stigma around female-specific conditions and events such as menstruation and menopause contributes to inadequate treatments and limited research investment in these domains [41]. Moreover, although approximately half of participants in NIH-supported clinical trials are women [42], female participants remain underrepresented in clinical trials for several health conditions that cause substantial morbidity in women, including HIV disease, kidney diseases, and cardiovascular diseases [43].

NIH ACTIVITIES RELATED TO GENDER AND HEALTH

The Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) was established in response to concerns about women’s underrepresentation in NIH-supported clinical and biomedical research in the early 1990s. The historical exclusion of women from clinical research rested on the gendered construction of a “normal” study participant as a 70 kg male, concerns that the normal hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycles might interfere with study results, and fears that enrollment of subjects capable of pregnancy might potentially lead to a teratogenic fetal exposure. The requirement that NIH-funded researchers enroll racial and ethnic minorities and women, including women of childbearing age, into clinical research trials was codified into Federal law in the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 [44].

As the legislatively mandated focal point for coordinating research on the health of women at NIH, ORWH collaborates with the NIH Institutes, Centers, and Offices (ICOs) and the broader scientific community to advance research on the health of women. ORWH supports research aligned with the NIH vision for women’s health research, detailed in the Advancing Science for the Health of Women: 2019–2023 Trans-NIH Strategic Plan for Women’s Health Research, in which the influence of sex and/or gender are integrated into the health research enterprise; every woman receives evidence-based disease prevention and treatment tailored to her own needs, circumstances, and goals; and women in science careers reach their full potential [45]. This Strategic Plan promotes coordination of efforts related to women’s health research across NIH ICOs and to develop methods and leverage data sources to consider sex and gender influences that enhance research for the health of women [45,46].

In addition to the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2021–2025 that outlines NIH’s highest priorities and vision for biomedical research direction, capacity, and stewardship, each ICO develops an individual strategic plan specific to the ICO’s mission and fields of study [47]. Many of these ICO Strategic Plans incorporate goals and objectives related to gender, and gender-related themes emerge across them. These themes include understanding gender influences on disease processes and outcomes, developing interventions specific to women’s health needs, improving the representation of women in clinical research studies, and eliminating health disparities for women. Multiple ICO strategic plans and the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan also highlight training, infrastructure, and capacity-building as strategies to enhance diversity in the health research workforce.

Partnered with other NIH ICOs, ORWH supports several signature programs that incorporate research related to gender, including an administrative supplement program for research on sex and gender influences on health and an administrative supplement that supports interdisciplinary research on populations of women that are understudied, under-represented, and under-reported (U3) in biomedical research. In addition, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) program is a mentored career development program supporting women’s health researchers. Additional current and recent NIH funding opportunities that specify an interest in research related to gender are listed in Table 1. Potential applicants are encouraged to reach out to the scientific contacts for these programs to discuss potential submissions, and to consult the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts (https://grants.nih.gov/funding/searchguide/index.html#/) regularly as new funding opportunities and notices are posted daily.

| Funding opportunity/notice . | Participating ICOs . |

|---|---|

| A new research education program from ORWH, Galvanizing Health Equity through Novel and Diverse Educational Resources (GENDER) R25 (RFA-OD-22-015) will support the development of courses, curricula, or methods focused on how health is influenced by gender, as an identity, social, cultural, or structural variable, and/or sex, as a biological variable | ORWH; NIA; NIAMS; NIDA; NIMHD; NLM; NIDCR; OBSSR; OAR; SGMRO |

| ORWH’s U3 program (Understudied, Underrepresented, and Underreported) includes administrative supplements (NOT-OD-22-208) targeting interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary research focused on the effects of sex and/or gender influences at the intersection of several social determinants—including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education, health literacy, gender identity, and urban or rural residence—in human health and illness | ORWH; NEI; NHLBI; NIA; NIAAA; NIAID; NIAMS; NIBIB; NICHD; NIDCD; NIDCR; NIDDK; NIDA; NIEHS; NIGMS; NIMH; NINDS; NINR; NCCIH; NCI; SGMRO; ONR |

| NIAID’s Transgender People: Immunity, Prevention, and Treatment of HIV and STIs R21 (PAR-22-186) will support short duration, high-risk and innovative, hypothesis-generating research focused on describing the systemic and mucosal impact of the drugs, hormones and surgical interventions used for gender reassignment and their impact on susceptibility to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) in transgender people | NIAID |

| NIAID’s American Women: Assessing Risk Epidemiologically (AWARE) R01 (RFA-AI-21-058) will support research that combines epidemiologic methods, digital technology, and data science approaches to better understand HIV prevention, transmission, and early care-cascade points for women living in the USA | NIAID; NIAAA; NICHD; NIDA; NIMH; OBSSR; ORWH |

| NICHD’s Multipurpose Prevention Technology: Novel Systemic Options for Young Adults R43/R44 (PAR-21-297) and NIAID’s Next Generation Multipurpose Prevention Technologies (NGM) R01 (PAR-22-222) will support development of multipurpose technologies that prevent HIV infection and pregnancy (hormonal and non-hormonal methods) in adolescent and young women, and encourages bio-behavioural and behavioural/social studies to identify MPT end user preferences factors (look, feel, effectiveness, safety and duration of action) and other behavioral/social factors that could promote increased MPT use in adolescent and young women | NICHD; NIAID; NIMH |

| NIA’s Sex and Gender Differences in AD/ADRD (NOT-AG-21-050) Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) promotes multidisciplinary research to clarify sex and gender differences in the risk, development, progression, diagnosis, and clinical presentation of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias (ADRD). It includes social level factors (e.g., history of maltreatment or adversity, parenthood, marital status, educational attainment, socioeconomic and employment status) and healthcare system-level (e.g., access to care) factors and processes that separately, or together, may drive observed differences by sex and gender and/or may operate differently by sex and gender | NIA |

| NIMH’s Notice of Information on High Priority Research Areas for Sex and Gender Influences on the Adolescent Brain and Mental Health of Girls and Young Women (Ages 12-24) (NOT-MH-22-245) outlines NIMH priorities in the field of women’s mental health research, including research projects that examine biological, social, cultural, and behavioural contributions of sex and gender influences on mental illnesses (e.g., anxiety, depression, psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, trauma-related disorders, eating disorders, etc.) autism spectrum disorder and suicide in adolescent girls and young women | NIMH |

| NIDA’s Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) on Mechanistic studies on the impact of substance use in sex and gender differences in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (NOT-DA-22-047) communicates NIDA’s special interest in understanding the neurobiological bases for sex or gender-specific differences in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders | NIDA |

| Funding opportunity/notice . | Participating ICOs . |

|---|---|

| A new research education program from ORWH, Galvanizing Health Equity through Novel and Diverse Educational Resources (GENDER) R25 (RFA-OD-22-015) will support the development of courses, curricula, or methods focused on how health is influenced by gender, as an identity, social, cultural, or structural variable, and/or sex, as a biological variable | ORWH; NIA; NIAMS; NIDA; NIMHD; NLM; NIDCR; OBSSR; OAR; SGMRO |

| ORWH’s U3 program (Understudied, Underrepresented, and Underreported) includes administrative supplements (NOT-OD-22-208) targeting interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary research focused on the effects of sex and/or gender influences at the intersection of several social determinants—including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education, health literacy, gender identity, and urban or rural residence—in human health and illness | ORWH; NEI; NHLBI; NIA; NIAAA; NIAID; NIAMS; NIBIB; NICHD; NIDCD; NIDCR; NIDDK; NIDA; NIEHS; NIGMS; NIMH; NINDS; NINR; NCCIH; NCI; SGMRO; ONR |

| NIAID’s Transgender People: Immunity, Prevention, and Treatment of HIV and STIs R21 (PAR-22-186) will support short duration, high-risk and innovative, hypothesis-generating research focused on describing the systemic and mucosal impact of the drugs, hormones and surgical interventions used for gender reassignment and their impact on susceptibility to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) in transgender people | NIAID |

| NIAID’s American Women: Assessing Risk Epidemiologically (AWARE) R01 (RFA-AI-21-058) will support research that combines epidemiologic methods, digital technology, and data science approaches to better understand HIV prevention, transmission, and early care-cascade points for women living in the USA | NIAID; NIAAA; NICHD; NIDA; NIMH; OBSSR; ORWH |

| NICHD’s Multipurpose Prevention Technology: Novel Systemic Options for Young Adults R43/R44 (PAR-21-297) and NIAID’s Next Generation Multipurpose Prevention Technologies (NGM) R01 (PAR-22-222) will support development of multipurpose technologies that prevent HIV infection and pregnancy (hormonal and non-hormonal methods) in adolescent and young women, and encourages bio-behavioural and behavioural/social studies to identify MPT end user preferences factors (look, feel, effectiveness, safety and duration of action) and other behavioral/social factors that could promote increased MPT use in adolescent and young women | NICHD; NIAID; NIMH |

| NIA’s Sex and Gender Differences in AD/ADRD (NOT-AG-21-050) Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) promotes multidisciplinary research to clarify sex and gender differences in the risk, development, progression, diagnosis, and clinical presentation of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias (ADRD). It includes social level factors (e.g., history of maltreatment or adversity, parenthood, marital status, educational attainment, socioeconomic and employment status) and healthcare system-level (e.g., access to care) factors and processes that separately, or together, may drive observed differences by sex and gender and/or may operate differently by sex and gender | NIA |

| NIMH’s Notice of Information on High Priority Research Areas for Sex and Gender Influences on the Adolescent Brain and Mental Health of Girls and Young Women (Ages 12-24) (NOT-MH-22-245) outlines NIMH priorities in the field of women’s mental health research, including research projects that examine biological, social, cultural, and behavioural contributions of sex and gender influences on mental illnesses (e.g., anxiety, depression, psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, trauma-related disorders, eating disorders, etc.) autism spectrum disorder and suicide in adolescent girls and young women | NIMH |

| NIDA’s Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) on Mechanistic studies on the impact of substance use in sex and gender differences in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (NOT-DA-22-047) communicates NIDA’s special interest in understanding the neurobiological bases for sex or gender-specific differences in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders | NIDA |

| Funding opportunity/notice . | Participating ICOs . |

|---|---|

| A new research education program from ORWH, Galvanizing Health Equity through Novel and Diverse Educational Resources (GENDER) R25 (RFA-OD-22-015) will support the development of courses, curricula, or methods focused on how health is influenced by gender, as an identity, social, cultural, or structural variable, and/or sex, as a biological variable | ORWH; NIA; NIAMS; NIDA; NIMHD; NLM; NIDCR; OBSSR; OAR; SGMRO |

| ORWH’s U3 program (Understudied, Underrepresented, and Underreported) includes administrative supplements (NOT-OD-22-208) targeting interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary research focused on the effects of sex and/or gender influences at the intersection of several social determinants—including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education, health literacy, gender identity, and urban or rural residence—in human health and illness | ORWH; NEI; NHLBI; NIA; NIAAA; NIAID; NIAMS; NIBIB; NICHD; NIDCD; NIDCR; NIDDK; NIDA; NIEHS; NIGMS; NIMH; NINDS; NINR; NCCIH; NCI; SGMRO; ONR |

| NIAID’s Transgender People: Immunity, Prevention, and Treatment of HIV and STIs R21 (PAR-22-186) will support short duration, high-risk and innovative, hypothesis-generating research focused on describing the systemic and mucosal impact of the drugs, hormones and surgical interventions used for gender reassignment and their impact on susceptibility to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) in transgender people | NIAID |

| NIAID’s American Women: Assessing Risk Epidemiologically (AWARE) R01 (RFA-AI-21-058) will support research that combines epidemiologic methods, digital technology, and data science approaches to better understand HIV prevention, transmission, and early care-cascade points for women living in the USA | NIAID; NIAAA; NICHD; NIDA; NIMH; OBSSR; ORWH |

| NICHD’s Multipurpose Prevention Technology: Novel Systemic Options for Young Adults R43/R44 (PAR-21-297) and NIAID’s Next Generation Multipurpose Prevention Technologies (NGM) R01 (PAR-22-222) will support development of multipurpose technologies that prevent HIV infection and pregnancy (hormonal and non-hormonal methods) in adolescent and young women, and encourages bio-behavioural and behavioural/social studies to identify MPT end user preferences factors (look, feel, effectiveness, safety and duration of action) and other behavioral/social factors that could promote increased MPT use in adolescent and young women | NICHD; NIAID; NIMH |

| NIA’s Sex and Gender Differences in AD/ADRD (NOT-AG-21-050) Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) promotes multidisciplinary research to clarify sex and gender differences in the risk, development, progression, diagnosis, and clinical presentation of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias (ADRD). It includes social level factors (e.g., history of maltreatment or adversity, parenthood, marital status, educational attainment, socioeconomic and employment status) and healthcare system-level (e.g., access to care) factors and processes that separately, or together, may drive observed differences by sex and gender and/or may operate differently by sex and gender | NIA |

| NIMH’s Notice of Information on High Priority Research Areas for Sex and Gender Influences on the Adolescent Brain and Mental Health of Girls and Young Women (Ages 12-24) (NOT-MH-22-245) outlines NIMH priorities in the field of women’s mental health research, including research projects that examine biological, social, cultural, and behavioural contributions of sex and gender influences on mental illnesses (e.g., anxiety, depression, psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, trauma-related disorders, eating disorders, etc.) autism spectrum disorder and suicide in adolescent girls and young women | NIMH |

| NIDA’s Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) on Mechanistic studies on the impact of substance use in sex and gender differences in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (NOT-DA-22-047) communicates NIDA’s special interest in understanding the neurobiological bases for sex or gender-specific differences in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders | NIDA |

| Funding opportunity/notice . | Participating ICOs . |

|---|---|

| A new research education program from ORWH, Galvanizing Health Equity through Novel and Diverse Educational Resources (GENDER) R25 (RFA-OD-22-015) will support the development of courses, curricula, or methods focused on how health is influenced by gender, as an identity, social, cultural, or structural variable, and/or sex, as a biological variable | ORWH; NIA; NIAMS; NIDA; NIMHD; NLM; NIDCR; OBSSR; OAR; SGMRO |

| ORWH’s U3 program (Understudied, Underrepresented, and Underreported) includes administrative supplements (NOT-OD-22-208) targeting interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary research focused on the effects of sex and/or gender influences at the intersection of several social determinants—including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education, health literacy, gender identity, and urban or rural residence—in human health and illness | ORWH; NEI; NHLBI; NIA; NIAAA; NIAID; NIAMS; NIBIB; NICHD; NIDCD; NIDCR; NIDDK; NIDA; NIEHS; NIGMS; NIMH; NINDS; NINR; NCCIH; NCI; SGMRO; ONR |

| NIAID’s Transgender People: Immunity, Prevention, and Treatment of HIV and STIs R21 (PAR-22-186) will support short duration, high-risk and innovative, hypothesis-generating research focused on describing the systemic and mucosal impact of the drugs, hormones and surgical interventions used for gender reassignment and their impact on susceptibility to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) in transgender people | NIAID |

| NIAID’s American Women: Assessing Risk Epidemiologically (AWARE) R01 (RFA-AI-21-058) will support research that combines epidemiologic methods, digital technology, and data science approaches to better understand HIV prevention, transmission, and early care-cascade points for women living in the USA | NIAID; NIAAA; NICHD; NIDA; NIMH; OBSSR; ORWH |

| NICHD’s Multipurpose Prevention Technology: Novel Systemic Options for Young Adults R43/R44 (PAR-21-297) and NIAID’s Next Generation Multipurpose Prevention Technologies (NGM) R01 (PAR-22-222) will support development of multipurpose technologies that prevent HIV infection and pregnancy (hormonal and non-hormonal methods) in adolescent and young women, and encourages bio-behavioural and behavioural/social studies to identify MPT end user preferences factors (look, feel, effectiveness, safety and duration of action) and other behavioral/social factors that could promote increased MPT use in adolescent and young women | NICHD; NIAID; NIMH |

| NIA’s Sex and Gender Differences in AD/ADRD (NOT-AG-21-050) Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) promotes multidisciplinary research to clarify sex and gender differences in the risk, development, progression, diagnosis, and clinical presentation of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias (ADRD). It includes social level factors (e.g., history of maltreatment or adversity, parenthood, marital status, educational attainment, socioeconomic and employment status) and healthcare system-level (e.g., access to care) factors and processes that separately, or together, may drive observed differences by sex and gender and/or may operate differently by sex and gender | NIA |

| NIMH’s Notice of Information on High Priority Research Areas for Sex and Gender Influences on the Adolescent Brain and Mental Health of Girls and Young Women (Ages 12-24) (NOT-MH-22-245) outlines NIMH priorities in the field of women’s mental health research, including research projects that examine biological, social, cultural, and behavioural contributions of sex and gender influences on mental illnesses (e.g., anxiety, depression, psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, trauma-related disorders, eating disorders, etc.) autism spectrum disorder and suicide in adolescent girls and young women | NIMH |

| NIDA’s Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) on Mechanistic studies on the impact of substance use in sex and gender differences in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (NOT-DA-22-047) communicates NIDA’s special interest in understanding the neurobiological bases for sex or gender-specific differences in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders | NIDA |

NIH is committed to fostering a culture of scientific stewardship and encourages broad and diverse input from the research community, public forums through consultation with advocacy groups, professional societies, and research participants. Aligned with this commitment and to inform a congressionally-requested conference on key issues in women’s health (Advancing NIH Research on the Health of Women: A 2021 Conference) [48], in 2021 ORWH published a Request for Information (RFI) in the Federal Register (86 FR 35099). Themes in the public comments related to gender were of particular concern in responses to the RFI including: intimate partner violence (IPV), sexual violence, and gender-based violence; intersectional stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings; and gender inequity.

Internal NIH roundtables

In recognition of the significant health impacts of gender as a social and cultural variable, ORWH and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) convened a series of roundtable discussions for NIH staff in fall 2021. These roundtables brought together scientific and program staff from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Fogarty International Center (FIC), NICHD, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR), Office of Disease Prevention (ODP), ORWH, and the Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office (SGMRO). Participants discussed how research on gender and health aligned with their ICO priorities; the landscape of research on gender roles, gender norms, and gender inequity; and gaps and opportunities in this domain. Themes that emerged included the key roles of intersectionality and a life course perspective in research on gender and health, gaps in the scientific literature on the mechanisms through which gender influences health, and the need for improved methods for studying and measuring gender equity and discrimination. The development of NIH-focused resources on gender and health for study section reviewers and NIH program staff was also identified as an area of opportunity.

Portfolio analysis

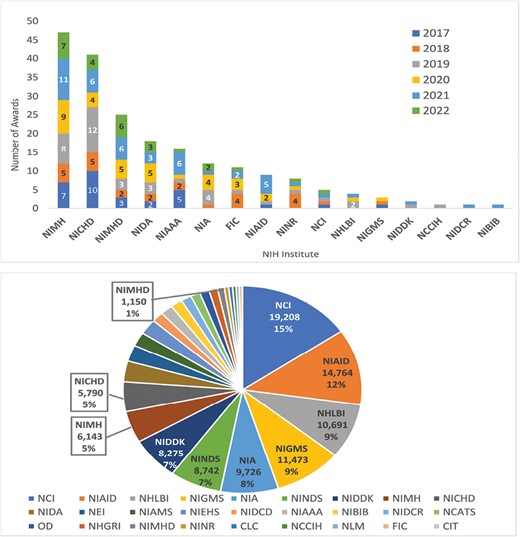

In follow-up to the internal roundtable discussions, a portfolio analysis was performed to clarify areas of strength and gaps in NIH-supported science on gender and health. The analysis included competing (Type 1 and Type 2) NIH awards issued from FY2017 through FY20221 that focused on the relationships between gender roles, relations, power dynamics, or (in)equity and health. The specific aims of awarded projects that included gender-related terms in the title or specific aims were reviewed for relevance, and projects were included if they explicitly addressed structural sexism, gender norms, gender power dynamics, or inequities. Across the six fiscal years, 204 competing awards were focused on gender and health, with sixteen of the 27 NIH institutes and centers (ICs) issuing at least one new gender-related award. Over half of the awards (55%, N = 113) were supported by three Institutes: NIMH, NICHD, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD)—comparatively small Institutes that together account for 11% of the NIH portfolio (Fig. 2). The concentration of gender-related research in this small proportion of ICOs suggests that gender has not been integrated across the breadth of the NIH portfolio. Further, gender-related awards constituted fewer than 1% of the overall competing awards NIMH, NICHD, and NIMHD issued across the same time period, suggesting opportunities for greater integration of gender-related research even within the ICs that have the largest gender and health portfolios.

NIH portfolio of gender-related research, FY2017–FY22. Top: number of gender-related competing grant awards, by Institute, Center, and Office (ICO) and fiscal year; bottom: all NIH competing grant awards, FY2017–FY2022, by ICO (total N = 124,364 grant awards).

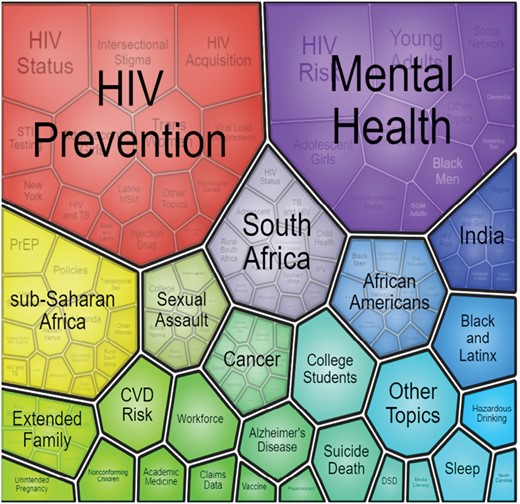

Over 80% of the competing awards on gender and health are within one of five activity code categories: Major Research Project Grants (28%, N = 57), Exploratory/Developmental Research Grants (20%, N = 40), Career Development Awards (16%, N = 32), Predoctoral Fellowships (10%, N = 20), and Small Research Grants (8%, N = 16). The remaining awards were primarily clinical trial planning grants; small business awards; or other fellowship, mentored research, or training awards. Among the recent gender-related awards, HIV prevention and mental health were the most common topics addressed, followed by sexual assault, cancer, and unintended pregnancy (Fig. 3). Many awards in the portfolio were focused on non-U.S. populations in areas where HIV prevalence remains high, such as countries in Africa or South Asia. Similarly, among the gender-related projects based in the USA, many focused on Black and/or Latinx populations, who disproportionately bear the burden of new HIV infections.

Major topics of gender-related awards, FY2017–FY2022. This visualization was prepared using the NIH Office of Portfolio Analysis iSearch technology and Visualize Results feature. Visualize Results uses a clustering algorithm (lingo3g) which takes words and phrases from the Chemicals and Drugs, Targets, and MeSH fields. The clusters displayed are scaled to the number of publications. Words are clustered based on how often they occur together in the same document. Before clustering, documents are preprocessed using stemming, stop words, and synonym normalization. CVD cardiovascular disease; DSD differences in sex development; PrEP pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Scientific workshop: “Gender and health: impacts of structural sexism, gender norms, relational power dynamics, and gender inequities”

Building on the findings in the portfolio analysis and the generative conversations from the internal NIH roundtables, ORWH and NICHD convened a scientific workshop titled Gender and Health: Impacts of structural sexism, gender norms, relational power dynamics, and gender inequities. The virtual workshop convened on October 26, 2022, in partnership with NIA, NIAID, NCI, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), NIMH, the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), and OBSSR. The workshop convened NIH staff, members of the external scientific community, and the public to discuss methods, measurement, interventions, and best practices in health research on gender as a social and cultural variable.

The overarching goal of the workshop was to identify opportunities to advance research on the health impacts of structural sexism, gender norms, relational power dynamics, and gender inequities. Specific workshop objectives included addressing issues in measurement and methods, identifying modifiable factors and points of intervention, highlighting interventions that target different levels of the relationships between gender and health, and fostering collaborations among scientists conducting research on gender and health. The morning session included plenary talks on gender norms, relational power dynamics, and gender inequity (Nancy Krieger, Ph.D.), structural sexism and policy considerations (Patricia Homan, Ph.D.), and intersectionality in research on gender and health (Typhanye Dyer, Ph.D., M.P.H.). The afternoon featured three concurrent sessions with a total of twelve presentations on measurement and methods of gender and structural sexism and modifiable social and clinical factors related to gender-related health disparities. A virtual poster hall exhibited research from new and established investigators in a broad range of scientific disciplines. The full day of presentations and posters are available for viewing on the ORWH website.

GAPS AND OPPORTUNITIES

The well-documented and far-reaching health impacts of gender as a social and structural variable demonstrate the alignment of gender-related health research with the NIH mission to seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and apply knowledge to enhance health. Yet, much of the NIH-supported research on gender and health has, to date, been limited to a discrete set of conditions (e.g., HIV, mental health, pregnancy) and locations (e.g., sub-Saharan Africa; India). Support for broader research on gender and health will promote rigorous health research and advance the health of women.

Healthcare and biomedical research has historically been centered around men and male bodies because of larger patriarchal social and cultural norms. Hence, the intersectional study of gender is a critical component of women’s health research, as the consequences of gender inequality affect women more acutely than men and historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups more than White individuals [2, 11, 49–51]. Women’s health research, as measured by the Manual Categorization System-Women’s Health (MCS-WH) reporting module, represented 10.8% of the NIH budget in FY 2020 ($4,446 million) [52]. NIH funding for conditions that predominantly affect women is lower than expected amounts based on the burdens of these diseases in the total U.S. population [53]. Although there is an association between burden of disease and NIH funding, historic funding for a condition or disease is the factor most strongly associated with continued funding, thereby perpetuating male bias in biomedical research [54].

Disaggregation of research data on sex and gender allows identification of and responses to how sex differences and gender inequalities affect health. In 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114–255) required that applicable NIH-defined Phase III clinical trials report results by sex/gender, [sic] race, and ethnicity on ClinicalTrials.gov. A 2018 analysis demonstrated, however, that fewer than one third of NIH-supported phase III clinical trials report disaggregated results by sex or gender [42]. Reporting “sex/gender” of clinical research participants using “either/or” categories is the current standard, which limits the ability for researchers to understand and delineate the distinct influences of gender on health. Just as consistent collection of age and sex data is essential to better understanding of the health impacts of these biological variables, routine and consistent collection of gender data could significantly enhance our understanding of this social and structural variable, as well as its interactions with other drivers of inequalities such as age, ethnicity, poverty level or geographic location to influence health outcomes. Work is underway to establish standards for measuring sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity [1], but there is—as of yet—no consensus on how to measure other gendered phenomena in health research, and additional research to validate instruments in the collection of information about gender is needed [55–58]. At minimum, researchers are encouraged to use the term sex when reporting biological factors and gender when reporting gender identity or psychosocial or cultural factors; disaggregate demographic data and all outcome data by sex, gender, or both; report the methods used to obtain information on sex, gender, or both; and note all limitations of these methods [59].

Behavioral and social sciences research (BSSR) plays an important role in understanding health. At NIH, BSSR is defined as the systematic study of behavioral, mental, and social phenomena. Behavioral phenomena are the observable actions of individuals or groups, and mental phenomena include knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, motivations, perceptions, cognitions, and emotions. Social phenomena include interactions between and among individuals and responses to the characteristics, structures, and functions of social groups and institutions (e.g., families, communities, schools, and workplaces) and the physical, economic, cultural, and policy environments in which social and behavioral phenomena occur [60]. Increasingly, the NIH has focused its attention on research designed to better understand and address the impact of structural factors on health, with particular attention to the role of BSSR [61]. For example, following the police killing of George Floyd in May of 2020, the NIH made a public commitment to ending structural racism [62]. Centering the social and structural dimensions of gender in health-related BSSR can help researchers address complex challenges, particularly those stemming from social inequities.

Both BSSR and gender studies draw on multiple scientific disciplines, theories, and methodological approaches to better understand how complex, multi-level factors (e.g., individual behaviors, social relationships, environment, policy) interact with one another and influence health. The diversity and complexity of approaches in BSSR affords the formulation of novel questions and methodologies to address systems of power and oppression and create interventions that target the root causes of health and illness. Exploring the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and institutional impacts of gender and its intersection with other socio-demographic factors, such as race, class, age, sexual orientation, rurality, and immigration status, may contribute to knowledge of when, how, and under what conditions attitudinal and structural oppression contribute to health disparities, which in turn could lead to the design of more impactful interventions for improving health. In sum, focusing on the multi-level and intersectional impacts of gender across the continuum of health is critical to expanding BSSR approaches and methods and advancing science to promote health equity.

Despite barriers to gender-related research, opportunities exist to support transdisciplinary knowledge transfer and interdisciplinary knowledge building by advancing health-related social science research that incorporates best practices from multiple disciplines (e.g., gender and women’s studies, sociology, psychology, medical humanities, and the population sciences) that have well-established methods, theories, and frameworks for examining the health impacts of gender and other social, cultural, and structural variables. A key opportunity is enhancing gender-related education and training for the health workforce. ORWH maintains a suite of E-Learning courses, including an introductory course titled Introduction to Sex and Gender: Core Concepts for Health-Related Research that explores sex, gender, and intersectionality as health-related variables, as well as the complexity within those domains. A new research education program from ORWH, Galvanizing Health Equity through Novel and Diverse Educational Resources (GENDER) R25 (RFA-OD-22-015) will support the development of courses, curricula, or methods focused on how health is influenced by gender, as an identity, social, cultural, or structural variable, and/or sex, as a biological variable.

A second critical opportunity is continued and expanded support for research that considers the multiple social, structural, biological, and behavioral factors that influence the health of women and individuals assigned female at birth, and the intersections of these factors. Gender is embedded in a complex milieu of social, structural, biological, and behavioral factors, and rigorous investigation of this complexity is essential to developing actionable interventions, addressing disparities, and advancing equity.

CONCLUSION

Recent NIH efforts on sexual harassment, structural racism, and maternal morbidity and mortality [63] demonstrate the NIH commitment to addressing complex social and structural factors that shape scientific culture and research and impact health. We are optimistic that, in partnership with the extramural community, NIH will continue advancing robust, transdisciplinary research on gender as a social, cultural, and structural variable across the NIH portfolio, building on successes in BSSR, HIV research, mental health, and global health.

Changing the culture to more rigorously consider gender and health is an ambitious, but achievable goal. Evidence from the successful implementation of NIH programs and policies such as UNITE [62], Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society (ComPASS), and Sex as a Biological Variable (SABV) demonstrates that historical imbalances can be corrected through a combination of policy, education, and scientific will [64–66]. The robust NIH portfolio of research related to sexual and gender minority health following the establishment of SGMRO in 2015 demonstrates that gender-related research is a priority at NIH—the challenge now is to expand this portfolio to (i) include all domains of gender (identity and expression, roles and norms, gendered power relations, and gender equality and equity) and (ii) continue delineating and untangling the effects of gender on health from the effects of sex and other biological variables. Meeting this challenge will require precise and accurate terminology; changes in health research design, data collection, and reporting; expanded training and educational opportunities for NIH staff and the extramural community; and potential shifts in NIH policies to encourage these practices. Precedent at funding agencies like the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the European Commission suggests that policies on integration of gender as a social, cultural, and structural variable in health research can be instrumental in advancing research of relevance to all [67]. NIH envisions a world where every woman receives evidence-based disease prevention and treatment tailored to her circumstances, needs, and goals; catalyzing gender-related research can enhance and further this vision.

Acknowledgements

The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views, official policy, or position of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Funding

This commentary was not funded by any grants.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This manuscript is a commentary and does not involve original data collection, therefore informed consent was not required.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Transparency Statement: This manuscript is a commentary and does not involve original data and thus no transparency statement is needed.

REFERENCES

Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. BSSR Definition. https://obssr.od.nih.gov/about/bssr-definition. Accessed February 27, 2023.

Footnotes

FY2022 data were incomplete at the time of the analysis, so Ns for FY2022 are partial.