-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sharon L Manne, Carolyn J Heckman, Deborah A Kashy, Lee M Ritterband, Frances P Thorndike, Carolina Lozada, Elliot J Coups, Randomized controlled trial of the mySmartSkin web-based intervention to promote skin self-examination and sun protection among individuals diagnosed with melanoma, Translational Behavioral Medicine, Volume 11, Issue 7, July 2021, Pages 1461–1472, https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibaa103

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Adherence to regular, thorough skin self-examination (SSE) and consistent sun protection behaviors among melanoma survivors is relatively low. This study reports on the impact of an online intervention, called mySmartSkin (MSS), on engagement in SSE and sun protection behaviors among melanoma survivors, as well as the mediators of the intervention effects. The intervention was compared with usual care (UC), and primary outcomes were assessed at 24 and 48 weeks. Short-term outcomes were also evaluated at 8 weeks postbaseline. Results demonstrate a significant effect on SSE and sun protection. At all three follow-up assessments, the proportion of participants reporting conducting a thorough SSE in the time since the previous assessment was significantly greater in MSS than in UC. In addition, both multivariate and univariate analyses indicated that engagement in sun protection behaviors was significantly higher in MSS than UC at 24 weeks, but the effect on sun protection at 48 weeks was significant only in multivariate analyses. Beneficial effects of MSS were significantly mediated by knowledge about melanoma and characteristics of suspicious lesions, as well as self-efficacy. Participant engagement in MSS was satisfactory, with approximately two-thirds of participants completing at least two of the three core components. Content was rated as highly trusted, easy to understand, easy to navigate, and helpful. In conclusion, MSS illustrated significant and durable effects on SSE and mixed results on sun protection. Future studies should consider ways to further enhance treatment effects and engagement in MSS.

Practice: Providing their melanoma survivors with a fully automated, interactive online behavioral intervention may improve their patients’ adherence to recommended surveillance and preventive practices.

Policy: Online programs for improving skin cancer surveillance and sun protection should be made available to health care providers working with melanoma survivors.

Research: Fully automated, interactive online interventions can increase knowledge about and confidence in engaging in recommended skin cancer surveillance and prevention practices and ultimately improve engagement in these practices among melanoma survivors.

INTRODUCTION

Melanoma is the fifth most common malignancy in the USA, and its incidence has been steadily increasing over the last four decades. The more than 1.2 million persons in the USA who are survivors of melanoma [1] are at elevated risk for disease recurrence, second primary melanomas, and keratinocyte carcinomas. To reduce these risks, dermatologists and oncologists conduct regular total cutaneous examinations after treatment is completed [2]. In addition to this follow-up surveillance, regular skin self-examination (SSE) and sun protection behaviors are recommended. As SSE is associated with reduced risk of advanced disease and research suggests that greater skin awareness is associated with improved survival [3, 4], professional organizations such as the American Cancer Society [5] and the American Academy of Dermatology [6] recommend regular SSE for these survivors. Engagement in regular sun protection behavior is also recommended to reduce the risk of subsequent skin cancers, because ultraviolet radiation from the sun is a contributing factor for melanoma and other skin cancers [7].

Although most melanoma survivors report conducting SSE [8–10], reported rates of regular, thorough SSEs range from 7% to 17% [8–12]. Similarly, survivors report engaging in higher levels of sun protection behaviors than the general population [13], but their sun protection behavior does not meet recommended practice [10, 12, 14].

There have been a limited number of interventions evaluated to improve SSE and sun protection behaviors among melanoma survivors [15–19]. Each has illustrated improvements in SSE [15–19]. However, only one of these studies targeted and evaluated sun protection and reported significant improvements in some behaviors [15]. To address this important survivorship surveillance and prevention concern, we developed an online intervention, called mySmartSkin (MSS), to improve SSE and sun protection behaviors among melanoma survivors. MSS is a behaviorally based program which is delivered via the Internet, tailored to the user, and fully automated with no human clinical support. The development and refinement of MSS has been previously published [20]. The conceptual framework guiding MSS was the Preventive Health Model (PHM) [21] and prior work evaluating factors associated with skin cancer surveillance and sun protection behaviors among melanoma survivors [8, 10–12, 22]. In addition to the impact of MSS on behaviors, this study evaluated possible mediators. Understanding the mechanisms through which the effects of a behavioral intervention occur fosters an understanding of possible active ingredients, clarifies underlying models of health behaviors that form the basis of these interventions, and suggests potential enhancements to the behavioral interventions themselves. There has been little attention paid to identifying mechanisms for behavioral interventions to improve SSE and sun protection among melanoma survivors. One prior study focusing on relatives of melanoma survivors compared a tailored print and telephone counseling intervention with a generic print and telephone counseling intervention on total cutaneous examinations, SSE, and sun protection behaviors [23] and evaluated intentions, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy as putative mediators for intervention effects on all three behaviors. Results suggested that increases in intentions to have a total cutaneous examination mediated the tailored intervention’s effects on total cutaneous examination uptake. Sun protection intentions, sun protection benefits, and sunscreen self-efficacy mediated the effects of the tailored intervention on sun protection behaviors.

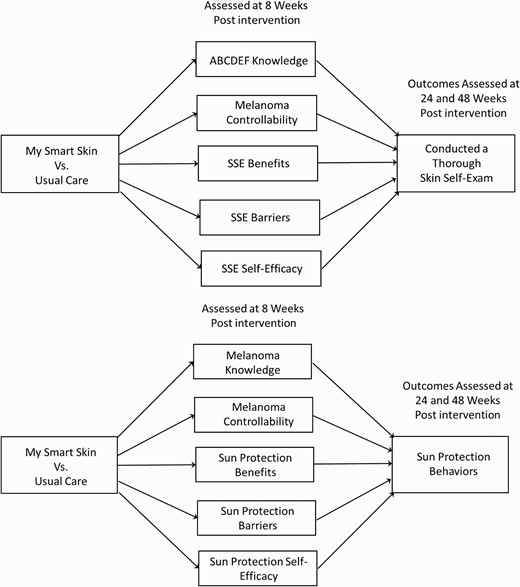

The current study had two aims. The first aim was to examine the impact of MSS on the primary study outcomes, which were engagement in thorough SSE and sun protection behavior, in a randomized controlled trial. MSS was compared with usual care (UC), which consisted of participants’ usual clinical follow-up care. We hypothesized that survivors assigned to MSS would report higher engagement in thorough SSE and report more sun protection behaviors than those assigned to UC at all time points. The second aim was to evaluate mediators of MSS’s effects. We focused on five constructs included in the PHM as our primary intervention mediators: knowledge, self-efficacy, benefits, barriers, and controllability. We examined these constructs as mediators of MSS’s effects on comprehensive SSE and sun protection behaviors at the 24 and 48 week time points. We proposed that intervention effects on SSE would be mediated by increased knowledge of suspicious lesions, increased self-efficacy for conducting SSE, increased perceived benefits of conducting SSE, decreased perceived barriers to SSE, and increased perceived controllability of melanoma, assessed at the 8 and 24 week follow-up time points (see the top model in Fig. 1). We proposed that intervention effects on sun protection would be mediated by increased melanoma knowledge, increased self-efficacy for sun protection behaviors, increased perceived benefits of sun protection behaviors, decreased barriers to sun protection behaviors, and increased perceived controllability of melanoma (see the bottom model in Fig. 1).

| Multiple mediator models for the mySmartSkin intervention predicting skin self-examinations (SSEs) (top model) and sun protection behaviors (bottom model) assessed at 24 or 48 week postintervention as a function of mediators assessed at 8 week postintervention. Although not included in the figures, stage at diagnosis, months since surgery, age, sex, and baseline outcome (either thorough skin self-examination or sun protection) were treated as covariates in the mediational analyses.

METHODS

Intervention development and core content, eligibility and recruitment methods, randomization procedures, measures, and sample size considerations are described in detail elsewhere [20]. Briefly, potentially eligible participants were recruited from Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, dermatology practices associated with Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, and Saint Barnabas Medical Center, and the New Jersey State Cancer Registry. There were variations in recruitment methods between the study sites, which are described in more detail in Coups et al. [20]. All participants provided informed consent prior to their enrollment in the study. The study received approval from the Rutgers Health Sciences and the Saint Barnabas Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

MSS consisted of an orientation section, three Cores, and a body mole map. Core 1 outlined the goals of the intervention, provided information about melanoma and risks of recurrence, skin cancer risk factors, how to do a thorough SSE, and an overview of sun protection behaviors. Core 2 assessed prior experience with SSE, benefits and barriers to SSE, confidence in conducting skin self-check, and strategies for doing a skin self-check. An online body mole map was provided to record and track moles and other skin growths over time. Core 3 assessed participants’ current sun-safe behaviors, guided them to set sun-safety goals, and provided a sun-safety action plan. There was also a section of the program where users could access printable documents from each core section and a summary of the most recent SSE and sun-safe action plan. Tailored activities included selecting reasons why conducting SSE (and engaging in sun protection) is important to the participant, assessing barriers to engaging in SSE (and engaging in sun protection), and completing action plans for SSE and sun protection. Participants could also log in to use the program to help them complete their monthly SSE. Participants assigned to the UC condition received no additional intervention aside from their usual nonstudy clinical care, which consisted of scheduled total cutaneous skin examinations by their physician.

Individuals diagnosed with stage 0–III melanoma who were 3–24 months postsurgery, had not completed a thorough SSE in the past 2 months, and/or were not adherent to sun protection recommendations, were ≥18 years of age, able to speak and read English, and had access to a computer connected to the Internet, participated in the study. Randomization was stratified by disease stage and the number of months since surgery and was implemented by the study’s biostatistician.

MEASURES

Outcome measures

Performance of thorough SSE

Participants reported if they had checked each part of their body for signs of skin cancer in the last 12 months (baseline survey), 2 months (for the 8 week survey), 4 months (for the 24 week survey), and 6 months (for the 48 week survey). Performance of a thorough SSE was defined as examining every area of the body during the most recent SSE (yes/no).

Sun protection behaviors

Participants rated how often they engaged in four behaviors when outside on a sunny day: wearing sunscreen with an Sun Protection Factor ≥30, wearing a long-sleeved shirt, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, and staying in the shade [24]. Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always).

Covariates

Covariates included the number of months since the melanoma surgery was performed, stage of disease (both collected from medical charts), age, sex, and baseline SSE or sun protection.

SSE mediators (8 and 24 weeks)

Knowledge about characteristics of abnormal lesions (ABCDEF)

Six multiple choice items assessed knowledge of the ABCDEFs of SSE [8, 25]. The ABCDEFs refer to characteristics of abnormal lesions: asymmetrical, irregular border, inconsistent color, large diameter, evolving or changing, and funny looking. The f criteria, usually referred to as the “ugly duckling sign,” has been developed to address the limits with ABCD rule, specifically the tendency for each patient’s nevi to have a similar pattern and a nevus that does not fit with this pattern should be considered with suspicion even if it does not fulfill the ABCD criteria [26]. We included the f criteria because work has indicated that overall patterns in nevi may enhance recognition of abnormal growths [27, 28]. The score reflected the number of correct answers. Internal consistency, as evaluated by coefficient alpha, was .80 at the 8 week and .79 at 24 week follow-up.

Perceived controllability of melanoma

Four Likert-rated items assessed controllability (sample item, “I have the power to influence my melanoma.”; 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) and were averaged [29]. Internal consistency, as evaluated by coefficient alpha, was .65 at the 8 week and .64 at 24 week follow-up.

SSE benefits

Eight Likert-rated items assessed perceived benefits of SSE (e.g., “Doing regular skin self-examination would provide me with peace of mind about my health”; 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) [10, 30]. A mean was calculated. Internal consistency, as evaluated by coefficient alpha, was .85 at the 8 week and .72 at 24 week follow-up.

SSE barriers

Eleven Likert-rated items assessed perceived barriers to conducting SSE (e.g., “Doing skin self-examination would be very embarrassing”; 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) [10, 30]. A mean was calculated. Internal consistency, as evaluated by coefficient alpha, was .80 at both the 8 and 24 week follow-ups.

Self-efficacy for SSE

A 12-item measure assessed confidence in examining different parts of the body for signs of skin cancer as well as confidence in telling the difference between a normal mole or skin growth and a melanoma based on shape, border, color, size, changes, and compared with other moles or skin growths (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) [8]. A mean was calculated. Internal consistency, as evaluated by coefficient alpha, was .96 at both the 8 and 24 week follow-ups.

Sun protection mediators (8 and 24 weeks)

Melanoma knowledge

Thirteen true–false items assessed knowledge about melanoma [10] (sample item: “Melanoma is the most common form of skin cancer.”). The score reflected the number of correct answers. Internal consistency, as evaluated by coefficient alpha, was .52 at the 8 week and .53 at the 24 week follow-up.

Perceived controllability of melanoma

The same measure described above was used [29].

Sun protection benefits

Twelve Likert-rated items evaluated benefits of sun protection behaviors (e.g., “Wearing a long-sleeved shirt when I am outside on a sunny day is an effective way to avoid getting a sunburn”; 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) [31]. A mean was calculated. Internal consistency, as evaluated by coefficient alpha, was .91 at the 8 week and .93 at the 24 week follow-up.

Sun protection barriers

Twenty-three items evaluated barriers to wearing sunscreen (eight items), wearing a long-sleeve shirt (six items), wearing a wide-brimmed hat (five items), and staying in the shade (four items) when outside on a sunny day (e.g., “Is inconvenient”) [31]. Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Internal consistency, as evaluated by coefficient alpha, was .90 at both the 8 and 24 week follow-ups.

Sun protection self-efficacy

Four Likert-rated items examined confidence in being able to engage in four sun protection practices (e.g., sunscreen, stay in the shade, or under an umbrella; 1 = not at all confident, 5 = very confident) [32]. A mean was calculated. Internal consistency, as evaluated by coefficient alpha, was .65 at the 8 week and .64 at the 24 week follow-up.

Intervention evaluation

At the 8 week follow-up, participants enrolled in the MSS intervention completed three evaluation surveys: (a) a 20-item Impact and Effectiveness measure assessing the degree to which MSS helped the participant learn how to be prepared to conduct SSE and engage in sun protection behaviors as well as feel in control of his/her health and feel less worried about melanoma (1 = not at all, 5 = very); (b) a 22-item intervention barriers measure, which evaluated technological barriers (4 items), personal barriers to use (6 items), general barriers to use (6 items), and intervention specific barriers (5 items; 0 = not a problem, 1 = a little problem, and 2 = a major problem); and (c) a 15-item Evaluation and Utility survey, which assessed program characteristics, including usefulness, convenience, ease of use, worry about privacy, ease of navigation, and satisfaction with the program (1 = not at all, 5 = very).

Data analytic approach

Descriptive analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 25. Tests of the intervention effects on SSE and sun protection, as well as mediation analyses, used Mplus Version 8.4 with full information maximum likelihood [33]. Logistic regression was used to predict SSE, and standard regression was used to predict sun protection. Both types of analyses controlled for stage, months since diagnosis, age, sex, and baseline score on the outcome (SSE or sun protection) as covariates. Separate models were used to predict SSE and sun protection behaviors at each wave of data collection. (The missing data approach specified in our protocol paper [20] stated that we would use multiple imputation and sensitivity analyses. However, because a main focus of the analyses in this paper were the estimates and tests of mediation using MPLUS, we used full information maximum likelihood as our missing data approach. Thus, we performed tests of the treatment on outcomes, as well as mediational analyses using FIML. Estimates and statistical significance values were virtually identical across the different approaches. The protocol paper also stated that covariates would be cancer stage at diagnosis and months since surgery. Age and patient sex were included at the recommendation of reviewers, and baseline score on the outcome was included because this is a standard control variable in longitudinal intervention research. Including these additional covariates resulted in one difference in results: Without the new covariates, the intervention effect on sun protection at 48 weeks was b = .13 and had p = .092 but with the new covariates the intervention effect at 48 weeks was b = .16 and had p = .005. All other tests resulted in similar conclusions across the two approaches.)

The mediation model predicting SSE (assessed 24 and 48 weeks) used a logistic regression approach with 1,000 bootstrapped samples. That model examined the indirect effects of treatment condition on SSE via mediators assessed at the 8 week follow-up. That is, the models assessed treatment effects on SSE at 24 week (or 48 week) follow-up via ABCDEF knowledge, perceived melanoma controllability, and SSE benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy. The mediation model predicting sun protection behaviors at the 24 week (or 48 week) follow-up used a standard regression approach, 1,000 bootstrapped samples, and included mediators assessed at 8 weeks. That is, treatment effects on sun protection at 24 and 48 week follow-ups were modeled to occur via melanoma knowledge, perceived controllability, and sun protection benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy. All mediation models also controlled for stage, months since surgery, age, sex, and baseline score on the outcome. Finally, in addition to examining the indirect effects of 8 week process variables on 48 week outcomes, we also tested whether the proposed mediator variables measured at 24 weeks mediated the effects of the intervention on 48 week outcomes.

RESULTS

Enrollment and retention

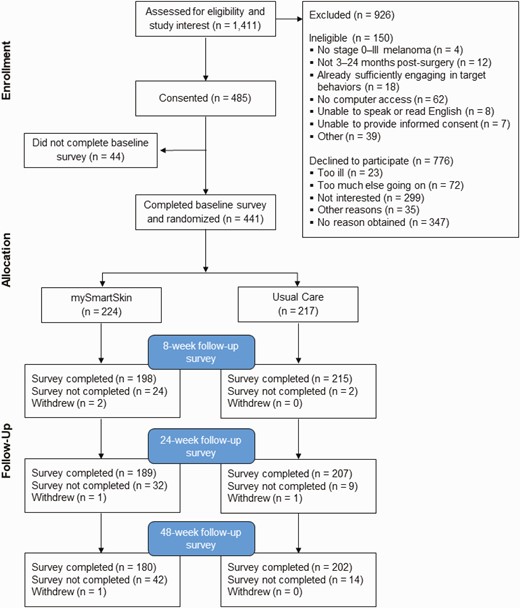

A total of 1,411 individuals were approached and assessed for eligibility and interest (see Fig. 2 with CONSORT diagram). Of the 485 individuals who consented to the study, 441 (90.9%) completed a baseline survey and were randomized to MSS (n = 224) or the UC condition (n = 217). Following established guidelines for estimating the proportion of individuals of unknown eligibility status who were in fact eligible for the study, the participant response rate was 40.9% [34]. Overall, the follow-up survey completion rates were high, although they were slightly lower among MSS participants than for UC participants at 8 weeks (88.3% and 99.1%, respectively), 24 weeks (84.4% and 96.3%, respectively), and 48 weeks (79.9% and 93.1%, respectively). Independent groups t-tests were used to compare participants who dropped out after the 8 and 24 week follow-ups with those who continued on all of the study variables. There were two significant differences, both on sun protection behavior. At both the 8 week, t(411) = 2.55, p = .011, and the 24 week follow-up, t(394) = 1.99, p = .047, individuals who dropped out had significantly lower sun protection compared with those who completed the study.

Background characteristics

More detailed description is available in the protocol paper published by Coups et al. [20]. Briefly, participants were primarily non-Hispanic white, 51% male, relatively well-educated, and primarily diagnosed with early stage melanoma. Comparisons between participants and study refusers revealed only one difference: study refusers were more likely to be male (58%) compared with study participants (51%; chi-square = 5.48, p = .019).

Utilization and evaluation of MSS

Use of MSS was calculated as the number of cores completed, the number of SSEs completed using the skin self-check mole map program, the number of sun-safe action plans completed using the online tool, and views of the program after the cores were completed that did not include completing a survey, the skin self-check mole map, or a sun-safe action plan. One hundred forty-eight of the 224 participants (66.1%) completed the orientation and all three cores, 25 (11.2%) completed the orientation and two cores, 10 (4.5%) completed the orientation and one core, 19 (8.5%) only completed the orientation core, and 22 (9.8%) did not complete any of the intervention. Almost 38% of participants did not use the Skin Self-check Program to complete SSE, 26.8% used it once, 15.2% used it twice, 7.1% used it three times, and the remaining 12.8% used it between 4 and 12 times over the follow-up. There was less use of the online Sun Safe Action Plan program, with almost 88% not using it and only 4.5% using it more than once. The average number of views that did not involve completing a core module, sun-safe action plan, or skin self-check mole map program was 5.2 (SD = 4.2). We compared participants who completed all three core modules with participants who did not on demographic (age, sex, marital status, education), medical (family history of melanoma, time since surgery), and baseline outcome and mediator variables in separate t-tests. There was one significant predictor, age (t(222) = 2.23, p < .05) Participants who completed all three cores were significantly older (M = 63.4, SD = 11.9) than those who did not (M = 59.3, SD = 14.4).

In terms of MSS evaluation, the average score on Intervention Impact and Effectiveness scale corresponded with “moderately” (M = 4.1, SD = .72, 5 = a lot), and average ratings on the Intervention Barriers scale ranged from .22 (technical) to 1.09 (personal; 0 = not a problem, 1 = a little problem). The average Intervention Evaluation and Utility score was 4.3 (SD = .65, 4 = mostly, 5 = very).

Impact of MSS on thorough SSE and sun protection behaviors

Table 1 presents the frequencies and percentages of participants who conducted a thorough SSE in the past 2 months (baseline) or since the last assessment (8, 24, and 48 weeks) by intervention group. Chi-square analyses indicated that although there were no differences at baseline, significantly more MSS participants reported conducting a thorough SSE relative to those in UC at each of the follow-ups. At the 24 week assessment, 29% of individuals in MSS conducted a thorough SSE, relative to only 11.6% of individuals in UC, and at 48 weeks similar percentages occurred (i.e., 30.9% vs. 13.3%). As indicated by the final column in Table 1, effect sizes were small to moderate. Table 2 presents corresponding logistic regression results predicting SSE at each wave as a function of the treatment, controlling for stage at diagnosis, months since surgery, age, sex, and baseline SSE. As with the univariate test results, at each follow-up participants in MSS were considerably more likely than participants in UC to conduct a thorough SSE.

| Descriptive statistics and univariate tests for thorough skin self-examination and sun protection outcomes at baseline, 8, 24, and 48 weeks

| . | mySmartSkin . | . | . | . | Usual care . | . | . | . | Univariate test of intervention effect . | . | Effect size . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thorough skin self-examination . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | N Yes . | % Yes . | N No . | % No . | N Yes . | % Yes . | N No . | % No . | χ 2 . | p . | r . |

| Baseline | 12 | 5.4 | 211 | 94.6 | 21 | 9.8 | 194 | 90.2 | 3.02 | .082 | .083 |

| 8 weeks | 59 | 29.8 | 139 | 70.2 | 16 | 7.4 | 199 | 92.6 | 34.66 | .001 | .290 |

| 24 weeks | 54 | 29.0 | 132 | 71.0 | 24 | 11.6 | 182 | 88.4 | 18.53 | .001 | .217 |

| 48 weeks | 54 | 30.9 | 121 | 69.1 | 26 | 13.3 | 169 | 86.7 | 16.71 | .001 | .212 |

| Sun protection behaviors | |||||||||||

| M | SD | N | M | SD | N | t | p | d | |||

| Baseline | 3.25 | .75 | 224 | 3.29 | .76 | 217 | −0.59 | .553 | −.053 | ||

| 8 weeks | 3.40 | .78 | 198 | 3.31 | .81 | 215 | 1.04 | .301 | .113 | ||

| 24 weeks | 3.54 | .74 | 189 | 3.37 | .84 | 207 | 2.15 | .031 | .215 | ||

| 48 weeks | 3.65 | .72 | 179 | 3.52 | .79 | 202 | 1.68 | .095 | .172 |

| . | mySmartSkin . | . | . | . | Usual care . | . | . | . | Univariate test of intervention effect . | . | Effect size . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thorough skin self-examination . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | N Yes . | % Yes . | N No . | % No . | N Yes . | % Yes . | N No . | % No . | χ 2 . | p . | r . |

| Baseline | 12 | 5.4 | 211 | 94.6 | 21 | 9.8 | 194 | 90.2 | 3.02 | .082 | .083 |

| 8 weeks | 59 | 29.8 | 139 | 70.2 | 16 | 7.4 | 199 | 92.6 | 34.66 | .001 | .290 |

| 24 weeks | 54 | 29.0 | 132 | 71.0 | 24 | 11.6 | 182 | 88.4 | 18.53 | .001 | .217 |

| 48 weeks | 54 | 30.9 | 121 | 69.1 | 26 | 13.3 | 169 | 86.7 | 16.71 | .001 | .212 |

| Sun protection behaviors | |||||||||||

| M | SD | N | M | SD | N | t | p | d | |||

| Baseline | 3.25 | .75 | 224 | 3.29 | .76 | 217 | −0.59 | .553 | −.053 | ||

| 8 weeks | 3.40 | .78 | 198 | 3.31 | .81 | 215 | 1.04 | .301 | .113 | ||

| 24 weeks | 3.54 | .74 | 189 | 3.37 | .84 | 207 | 2.15 | .031 | .215 | ||

| 48 weeks | 3.65 | .72 | 179 | 3.52 | .79 | 202 | 1.68 | .095 | .172 |

| Descriptive statistics and univariate tests for thorough skin self-examination and sun protection outcomes at baseline, 8, 24, and 48 weeks

| . | mySmartSkin . | . | . | . | Usual care . | . | . | . | Univariate test of intervention effect . | . | Effect size . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thorough skin self-examination . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | N Yes . | % Yes . | N No . | % No . | N Yes . | % Yes . | N No . | % No . | χ 2 . | p . | r . |

| Baseline | 12 | 5.4 | 211 | 94.6 | 21 | 9.8 | 194 | 90.2 | 3.02 | .082 | .083 |

| 8 weeks | 59 | 29.8 | 139 | 70.2 | 16 | 7.4 | 199 | 92.6 | 34.66 | .001 | .290 |

| 24 weeks | 54 | 29.0 | 132 | 71.0 | 24 | 11.6 | 182 | 88.4 | 18.53 | .001 | .217 |

| 48 weeks | 54 | 30.9 | 121 | 69.1 | 26 | 13.3 | 169 | 86.7 | 16.71 | .001 | .212 |

| Sun protection behaviors | |||||||||||

| M | SD | N | M | SD | N | t | p | d | |||

| Baseline | 3.25 | .75 | 224 | 3.29 | .76 | 217 | −0.59 | .553 | −.053 | ||

| 8 weeks | 3.40 | .78 | 198 | 3.31 | .81 | 215 | 1.04 | .301 | .113 | ||

| 24 weeks | 3.54 | .74 | 189 | 3.37 | .84 | 207 | 2.15 | .031 | .215 | ||

| 48 weeks | 3.65 | .72 | 179 | 3.52 | .79 | 202 | 1.68 | .095 | .172 |

| . | mySmartSkin . | . | . | . | Usual care . | . | . | . | Univariate test of intervention effect . | . | Effect size . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thorough skin self-examination . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | N Yes . | % Yes . | N No . | % No . | N Yes . | % Yes . | N No . | % No . | χ 2 . | p . | r . |

| Baseline | 12 | 5.4 | 211 | 94.6 | 21 | 9.8 | 194 | 90.2 | 3.02 | .082 | .083 |

| 8 weeks | 59 | 29.8 | 139 | 70.2 | 16 | 7.4 | 199 | 92.6 | 34.66 | .001 | .290 |

| 24 weeks | 54 | 29.0 | 132 | 71.0 | 24 | 11.6 | 182 | 88.4 | 18.53 | .001 | .217 |

| 48 weeks | 54 | 30.9 | 121 | 69.1 | 26 | 13.3 | 169 | 86.7 | 16.71 | .001 | .212 |

| Sun protection behaviors | |||||||||||

| M | SD | N | M | SD | N | t | p | d | |||

| Baseline | 3.25 | .75 | 224 | 3.29 | .76 | 217 | −0.59 | .553 | −.053 | ||

| 8 weeks | 3.40 | .78 | 198 | 3.31 | .81 | 215 | 1.04 | .301 | .113 | ||

| 24 weeks | 3.54 | .74 | 189 | 3.37 | .84 | 207 | 2.15 | .031 | .215 | ||

| 48 weeks | 3.65 | .72 | 179 | 3.52 | .79 | 202 | 1.68 | .095 | .172 |

| Regression results predicting whether an individual conducted a thorough skin self-examination (logistic regression) and degree of engagement in sun protection behaviors (standard regression) at baseline, 8, 24, and 48 week follow-up

| . | Logistic regression models predicting thorough skin self-examination . | . | . | . | . | Standard regression models predicting sun protection behaviors . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | b . | se . | p . | 95% CI for b . | OR . | b . | se . | p . | 95% CI for b . |

| 8 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 2.23 | .38 | <.001 | 1.48 to 2.97 | 9.26 | .11 | .06 | .062 | −.01 to .23 |

| Disease stage | .16 | .18 | .367 | −.19 to .52 | 1.18 | −.03 | .04 | .471 | −.11 to .05 |

| Months since surgery | −.02 | .03 | .487 | −.08 to .04 | .98 | .01 | .01 | −.353 | −.01 to .02 |

| Age | .01 | .01 | .445 | −.01 to .03 | 1.01 | .00 | .00 | .196 | −.00 to .01 |

| Sex | −.15 | .15 | .304 | −.45 to .14 | .86 | −.01 | .03 | .662 | −.08 to .05 |

| Baseline outcomea | 2.89 | .49 | <.001 | 1.93 to 3.85 | 17.97 | .66 | .04 | <.001 | .58 to .74 |

| 24 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 1.40 | .30 | <.001 | .81 to 2.00 | 4.08 | .19 | .06 | .001 | .08 to .31 |

| Disease stage | .19 | .17 | .267 | −.15 to .53 | 1.21 | .00 | .04 | .991 | −.08 to .08 |

| Months since surgery | −.02 | .03 | .528 | −.07 to .04 | .98 | −.00 | .01 | .824 | −.01 to .01 |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | .505 | −.03 to .01 | .99 | .00 | .00 | .140 | −.00 to.01 |

| Sex | .09 | .15 | .544 | −.20 to .38 | 1.09 | −.01 | .03 | .754 | −.07 to.05 |

| Baseline outcomea | 2.25 | .44 | <.001 | 1.39 to 3.11 | 9.50 | .69 | .04 | <.001 | .61 to.77 |

| 48 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 1.27 | .29 | <.001 | .70 to 1.84 | 3.56 | .16 | .06 | .005 | .05 to .28 |

| Disease stage | .08 | .17 | .662 | −.26 to .41 | 1.08 | .03 | .04 | .509 | −.05 to .10 |

| Months since surgery | −.03 | .03 | .197 | −.09 to .02 | .97 | −.00 | .01 | .747 | −.01 to .01 |

| Age | .00 | .01 | .947 | −.02 to .02 | 1.00 | .01 | .00 | .016 | .00 to .01 |

| Sex | .14 | .14 | .316 | −.14 to .42 | 1.15 | −.04 | .03 | .244 | −.10 to .02 |

| Baseline outcomea | 1.88 | .46 | <.001 | .97 to 2.78 | 6.52 | .65 | .04 | <.001 | .57 to .73 |

| . | Logistic regression models predicting thorough skin self-examination . | . | . | . | . | Standard regression models predicting sun protection behaviors . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | b . | se . | p . | 95% CI for b . | OR . | b . | se . | p . | 95% CI for b . |

| 8 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 2.23 | .38 | <.001 | 1.48 to 2.97 | 9.26 | .11 | .06 | .062 | −.01 to .23 |

| Disease stage | .16 | .18 | .367 | −.19 to .52 | 1.18 | −.03 | .04 | .471 | −.11 to .05 |

| Months since surgery | −.02 | .03 | .487 | −.08 to .04 | .98 | .01 | .01 | −.353 | −.01 to .02 |

| Age | .01 | .01 | .445 | −.01 to .03 | 1.01 | .00 | .00 | .196 | −.00 to .01 |

| Sex | −.15 | .15 | .304 | −.45 to .14 | .86 | −.01 | .03 | .662 | −.08 to .05 |

| Baseline outcomea | 2.89 | .49 | <.001 | 1.93 to 3.85 | 17.97 | .66 | .04 | <.001 | .58 to .74 |

| 24 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 1.40 | .30 | <.001 | .81 to 2.00 | 4.08 | .19 | .06 | .001 | .08 to .31 |

| Disease stage | .19 | .17 | .267 | −.15 to .53 | 1.21 | .00 | .04 | .991 | −.08 to .08 |

| Months since surgery | −.02 | .03 | .528 | −.07 to .04 | .98 | −.00 | .01 | .824 | −.01 to .01 |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | .505 | −.03 to .01 | .99 | .00 | .00 | .140 | −.00 to.01 |

| Sex | .09 | .15 | .544 | −.20 to .38 | 1.09 | −.01 | .03 | .754 | −.07 to.05 |

| Baseline outcomea | 2.25 | .44 | <.001 | 1.39 to 3.11 | 9.50 | .69 | .04 | <.001 | .61 to.77 |

| 48 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 1.27 | .29 | <.001 | .70 to 1.84 | 3.56 | .16 | .06 | .005 | .05 to .28 |

| Disease stage | .08 | .17 | .662 | −.26 to .41 | 1.08 | .03 | .04 | .509 | −.05 to .10 |

| Months since surgery | −.03 | .03 | .197 | −.09 to .02 | .97 | −.00 | .01 | .747 | −.01 to .01 |

| Age | .00 | .01 | .947 | −.02 to .02 | 1.00 | .01 | .00 | .016 | .00 to .01 |

| Sex | .14 | .14 | .316 | −.14 to .42 | 1.15 | −.04 | .03 | .244 | −.10 to .02 |

| Baseline outcomea | 1.88 | .46 | <.001 | .97 to 2.78 | 6.52 | .65 | .04 | <.001 | .57 to .73 |

CI confidence interval; OR odds ratio; SSE skin self-examination.

aBaseline outcome is baseline score on SSE for models predicting thorough SSE and it is baseline score on sun protection for models predicting sun protection. Sex is coded men = 1, women = −1.

| Regression results predicting whether an individual conducted a thorough skin self-examination (logistic regression) and degree of engagement in sun protection behaviors (standard regression) at baseline, 8, 24, and 48 week follow-up

| . | Logistic regression models predicting thorough skin self-examination . | . | . | . | . | Standard regression models predicting sun protection behaviors . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | b . | se . | p . | 95% CI for b . | OR . | b . | se . | p . | 95% CI for b . |

| 8 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 2.23 | .38 | <.001 | 1.48 to 2.97 | 9.26 | .11 | .06 | .062 | −.01 to .23 |

| Disease stage | .16 | .18 | .367 | −.19 to .52 | 1.18 | −.03 | .04 | .471 | −.11 to .05 |

| Months since surgery | −.02 | .03 | .487 | −.08 to .04 | .98 | .01 | .01 | −.353 | −.01 to .02 |

| Age | .01 | .01 | .445 | −.01 to .03 | 1.01 | .00 | .00 | .196 | −.00 to .01 |

| Sex | −.15 | .15 | .304 | −.45 to .14 | .86 | −.01 | .03 | .662 | −.08 to .05 |

| Baseline outcomea | 2.89 | .49 | <.001 | 1.93 to 3.85 | 17.97 | .66 | .04 | <.001 | .58 to .74 |

| 24 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 1.40 | .30 | <.001 | .81 to 2.00 | 4.08 | .19 | .06 | .001 | .08 to .31 |

| Disease stage | .19 | .17 | .267 | −.15 to .53 | 1.21 | .00 | .04 | .991 | −.08 to .08 |

| Months since surgery | −.02 | .03 | .528 | −.07 to .04 | .98 | −.00 | .01 | .824 | −.01 to .01 |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | .505 | −.03 to .01 | .99 | .00 | .00 | .140 | −.00 to.01 |

| Sex | .09 | .15 | .544 | −.20 to .38 | 1.09 | −.01 | .03 | .754 | −.07 to.05 |

| Baseline outcomea | 2.25 | .44 | <.001 | 1.39 to 3.11 | 9.50 | .69 | .04 | <.001 | .61 to.77 |

| 48 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 1.27 | .29 | <.001 | .70 to 1.84 | 3.56 | .16 | .06 | .005 | .05 to .28 |

| Disease stage | .08 | .17 | .662 | −.26 to .41 | 1.08 | .03 | .04 | .509 | −.05 to .10 |

| Months since surgery | −.03 | .03 | .197 | −.09 to .02 | .97 | −.00 | .01 | .747 | −.01 to .01 |

| Age | .00 | .01 | .947 | −.02 to .02 | 1.00 | .01 | .00 | .016 | .00 to .01 |

| Sex | .14 | .14 | .316 | −.14 to .42 | 1.15 | −.04 | .03 | .244 | −.10 to .02 |

| Baseline outcomea | 1.88 | .46 | <.001 | .97 to 2.78 | 6.52 | .65 | .04 | <.001 | .57 to .73 |

| . | Logistic regression models predicting thorough skin self-examination . | . | . | . | . | Standard regression models predicting sun protection behaviors . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | b . | se . | p . | 95% CI for b . | OR . | b . | se . | p . | 95% CI for b . |

| 8 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 2.23 | .38 | <.001 | 1.48 to 2.97 | 9.26 | .11 | .06 | .062 | −.01 to .23 |

| Disease stage | .16 | .18 | .367 | −.19 to .52 | 1.18 | −.03 | .04 | .471 | −.11 to .05 |

| Months since surgery | −.02 | .03 | .487 | −.08 to .04 | .98 | .01 | .01 | −.353 | −.01 to .02 |

| Age | .01 | .01 | .445 | −.01 to .03 | 1.01 | .00 | .00 | .196 | −.00 to .01 |

| Sex | −.15 | .15 | .304 | −.45 to .14 | .86 | −.01 | .03 | .662 | −.08 to .05 |

| Baseline outcomea | 2.89 | .49 | <.001 | 1.93 to 3.85 | 17.97 | .66 | .04 | <.001 | .58 to .74 |

| 24 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 1.40 | .30 | <.001 | .81 to 2.00 | 4.08 | .19 | .06 | .001 | .08 to .31 |

| Disease stage | .19 | .17 | .267 | −.15 to .53 | 1.21 | .00 | .04 | .991 | −.08 to .08 |

| Months since surgery | −.02 | .03 | .528 | −.07 to .04 | .98 | −.00 | .01 | .824 | −.01 to .01 |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | .505 | −.03 to .01 | .99 | .00 | .00 | .140 | −.00 to.01 |

| Sex | .09 | .15 | .544 | −.20 to .38 | 1.09 | −.01 | .03 | .754 | −.07 to.05 |

| Baseline outcomea | 2.25 | .44 | <.001 | 1.39 to 3.11 | 9.50 | .69 | .04 | <.001 | .61 to.77 |

| 48 weeks | |||||||||

| Intervention condition | 1.27 | .29 | <.001 | .70 to 1.84 | 3.56 | .16 | .06 | .005 | .05 to .28 |

| Disease stage | .08 | .17 | .662 | −.26 to .41 | 1.08 | .03 | .04 | .509 | −.05 to .10 |

| Months since surgery | −.03 | .03 | .197 | −.09 to .02 | .97 | −.00 | .01 | .747 | −.01 to .01 |

| Age | .00 | .01 | .947 | −.02 to .02 | 1.00 | .01 | .00 | .016 | .00 to .01 |

| Sex | .14 | .14 | .316 | −.14 to .42 | 1.15 | −.04 | .03 | .244 | −.10 to .02 |

| Baseline outcomea | 1.88 | .46 | <.001 | .97 to 2.78 | 6.52 | .65 | .04 | <.001 | .57 to .73 |

CI confidence interval; OR odds ratio; SSE skin self-examination.

aBaseline outcome is baseline score on SSE for models predicting thorough SSE and it is baseline score on sun protection for models predicting sun protection. Sex is coded men = 1, women = −1.

Table 1 also shows the means, standard deviations, and t-tests for the sun protection behaviors outcome. The only statistically significant mean difference occurred at 24 weeks such that individuals in MSS reported engaging in more sun protection behaviors at 24 weeks relative to UC. Similar results emerged in multiple regression models that tested the intervention effect controlling for the covariates, although in the multiple regression analyses the intervention effect was significant at both 24 and 48 weeks (see Table 2).

Mediation of the effects of the MSS intervention on SSE at the 24 and 48 week follow-ups

Mediation results predicting SSE at the 24 and 48 weeks are presented in Table 3. (Supplementary Table S1 presents the correlations, means, and standard deviations for the SSE outcomes at 24 and 48 weeks, the SSE mediators measured at 8 weeks, and the five covariates. The t-tests for the SSE mediators indicate that there were significant differences by condition for four of the five mediators assessed at the 8 week follow-up. Specifically, knowledge of suspicious lesions, controllability of melanoma, SSE benefits, and SSE self-efficacy were significantly higher in MSS relative to UC. There were no significant mean differences found for SSE barriers.) The total effect of treatment condition on 24 week SSE was b = 1.624, se = .400, p < .001, odds ratio (OR) = 5.073, 95% confidence interval (CI) .753 to 2.322. The total indirect effect of treatment was b = 1.09, indicating that 67% of the effect of the treatment on SSE was mediated through the five mediators together. Two mediators yielded significant specific indirect effects: knowledge of suspicious lesions (mediating 17% of the total effect) and SSE self-efficacy (mediating 46% of the total effect). These results indicate that the MSS intervention was effective for increasing the likelihood that participants conducted a thorough SSE because it increased knowledge about the characteristics of abnormal lesions and increased self-efficacy for conducting a thorough SSE.

| Logistic regression coefficients, standard errors, odds ratios, and confidence intervals for direct, and indirect effects of the mySmartSkin (MSS) intervention on 24 and 48 week postintervention thorough skin self-examination as mediated by process variables assessed at the 8 week follow-up

| . | Predicting 24 weeks thorough skin examination . | . | . | . | Predicting 48 weeks thorough skin examination . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Direct effects . | . | Indirect effects . | . | Direct effects . | . | Indirect effects . | . |

| . | b (se) . | OR . | b (se) . | 95% CI . | b (se) . | OR . | b (se) . | 95% CI . |

| Treatment (MSS vs. UC) | .53 (.38) | 1.70 | .77 (.42) | 2.16 | ||||

| Mediators (8 weeks) | ||||||||

| Knowledge of S.L. | .27 (.11)* | 1.31 | .42 (.18)* | .08 to .76 | −.09 (.11) | .91 | −.14 (.16) | −.47 to .19 |

| Controllability | .17 (.25) | 1.19 | .03 (.05) | −.04 to .14 | .14 (.27) | 1.15 | .02 (.05) | −.06 to .16 |

| SSE benefits | .39 (.43) | 1.48 | .07 (.08) | −.04 to .29 | .75 (.49) | 2.19 | .14 (.12) | −.00 to .43 |

| SSE barriers | −.49 (.30) | .61 | .06 (.06) | −.00 to .21 | −.80 (.31)** | .45 | .10 (.07) | .01 to .26 |

| SSE self-efficacy | .75 (.26)** | 2.13 | .52 (.20)** | .18 to .97 | .66 (.24)** | 1.93 | .46 (.18)* | .11 to .83 |

| Total indirect | 1.09 (.26)** | .58 to 1.54 | .58 (.24)* | .16 to 1.04 | ||||

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Cancer stage | .24 (.22) | 1.27 | .06 (.22) | 1.07 | ||||

| Months since surgery | −.00 (.03 | 1.00 | −.02 (.03) | .98 | ||||

| Age | .00 (.01) | 1.01 | .00 (.01) | 1.00 | ||||

| Sex | .13 (.19) | 1.04 | .15 (.17) | 1.16 | ||||

| Baseline thorough SSE | 1.79 (.58)** | 5.98 | 1.26 (.53)* | 3.52 |

| . | Predicting 24 weeks thorough skin examination . | . | . | . | Predicting 48 weeks thorough skin examination . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Direct effects . | . | Indirect effects . | . | Direct effects . | . | Indirect effects . | . |

| . | b (se) . | OR . | b (se) . | 95% CI . | b (se) . | OR . | b (se) . | 95% CI . |

| Treatment (MSS vs. UC) | .53 (.38) | 1.70 | .77 (.42) | 2.16 | ||||

| Mediators (8 weeks) | ||||||||

| Knowledge of S.L. | .27 (.11)* | 1.31 | .42 (.18)* | .08 to .76 | −.09 (.11) | .91 | −.14 (.16) | −.47 to .19 |

| Controllability | .17 (.25) | 1.19 | .03 (.05) | −.04 to .14 | .14 (.27) | 1.15 | .02 (.05) | −.06 to .16 |

| SSE benefits | .39 (.43) | 1.48 | .07 (.08) | −.04 to .29 | .75 (.49) | 2.19 | .14 (.12) | −.00 to .43 |

| SSE barriers | −.49 (.30) | .61 | .06 (.06) | −.00 to .21 | −.80 (.31)** | .45 | .10 (.07) | .01 to .26 |

| SSE self-efficacy | .75 (.26)** | 2.13 | .52 (.20)** | .18 to .97 | .66 (.24)** | 1.93 | .46 (.18)* | .11 to .83 |

| Total indirect | 1.09 (.26)** | .58 to 1.54 | .58 (.24)* | .16 to 1.04 | ||||

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Cancer stage | .24 (.22) | 1.27 | .06 (.22) | 1.07 | ||||

| Months since surgery | −.00 (.03 | 1.00 | −.02 (.03) | .98 | ||||

| Age | .00 (.01) | 1.01 | .00 (.01) | 1.00 | ||||

| Sex | .13 (.19) | 1.04 | .15 (.17) | 1.16 | ||||

| Baseline thorough SSE | 1.79 (.58)** | 5.98 | 1.26 (.53)* | 3.52 |

Note. *p < .05, **p ≤ .01. CI confidence interval; Knowledge of S.L. knowledge of suspicious lesions; OR odds ratio or exp(b); SSE skin self-examination; UC usual care. Sex is coded men = 1, women = −1.

| Logistic regression coefficients, standard errors, odds ratios, and confidence intervals for direct, and indirect effects of the mySmartSkin (MSS) intervention on 24 and 48 week postintervention thorough skin self-examination as mediated by process variables assessed at the 8 week follow-up

| . | Predicting 24 weeks thorough skin examination . | . | . | . | Predicting 48 weeks thorough skin examination . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Direct effects . | . | Indirect effects . | . | Direct effects . | . | Indirect effects . | . |

| . | b (se) . | OR . | b (se) . | 95% CI . | b (se) . | OR . | b (se) . | 95% CI . |

| Treatment (MSS vs. UC) | .53 (.38) | 1.70 | .77 (.42) | 2.16 | ||||

| Mediators (8 weeks) | ||||||||

| Knowledge of S.L. | .27 (.11)* | 1.31 | .42 (.18)* | .08 to .76 | −.09 (.11) | .91 | −.14 (.16) | −.47 to .19 |

| Controllability | .17 (.25) | 1.19 | .03 (.05) | −.04 to .14 | .14 (.27) | 1.15 | .02 (.05) | −.06 to .16 |

| SSE benefits | .39 (.43) | 1.48 | .07 (.08) | −.04 to .29 | .75 (.49) | 2.19 | .14 (.12) | −.00 to .43 |

| SSE barriers | −.49 (.30) | .61 | .06 (.06) | −.00 to .21 | −.80 (.31)** | .45 | .10 (.07) | .01 to .26 |

| SSE self-efficacy | .75 (.26)** | 2.13 | .52 (.20)** | .18 to .97 | .66 (.24)** | 1.93 | .46 (.18)* | .11 to .83 |

| Total indirect | 1.09 (.26)** | .58 to 1.54 | .58 (.24)* | .16 to 1.04 | ||||

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Cancer stage | .24 (.22) | 1.27 | .06 (.22) | 1.07 | ||||

| Months since surgery | −.00 (.03 | 1.00 | −.02 (.03) | .98 | ||||

| Age | .00 (.01) | 1.01 | .00 (.01) | 1.00 | ||||

| Sex | .13 (.19) | 1.04 | .15 (.17) | 1.16 | ||||

| Baseline thorough SSE | 1.79 (.58)** | 5.98 | 1.26 (.53)* | 3.52 |

| . | Predicting 24 weeks thorough skin examination . | . | . | . | Predicting 48 weeks thorough skin examination . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Direct effects . | . | Indirect effects . | . | Direct effects . | . | Indirect effects . | . |

| . | b (se) . | OR . | b (se) . | 95% CI . | b (se) . | OR . | b (se) . | 95% CI . |

| Treatment (MSS vs. UC) | .53 (.38) | 1.70 | .77 (.42) | 2.16 | ||||

| Mediators (8 weeks) | ||||||||

| Knowledge of S.L. | .27 (.11)* | 1.31 | .42 (.18)* | .08 to .76 | −.09 (.11) | .91 | −.14 (.16) | −.47 to .19 |

| Controllability | .17 (.25) | 1.19 | .03 (.05) | −.04 to .14 | .14 (.27) | 1.15 | .02 (.05) | −.06 to .16 |

| SSE benefits | .39 (.43) | 1.48 | .07 (.08) | −.04 to .29 | .75 (.49) | 2.19 | .14 (.12) | −.00 to .43 |

| SSE barriers | −.49 (.30) | .61 | .06 (.06) | −.00 to .21 | −.80 (.31)** | .45 | .10 (.07) | .01 to .26 |

| SSE self-efficacy | .75 (.26)** | 2.13 | .52 (.20)** | .18 to .97 | .66 (.24)** | 1.93 | .46 (.18)* | .11 to .83 |

| Total indirect | 1.09 (.26)** | .58 to 1.54 | .58 (.24)* | .16 to 1.04 | ||||

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Cancer stage | .24 (.22) | 1.27 | .06 (.22) | 1.07 | ||||

| Months since surgery | −.00 (.03 | 1.00 | −.02 (.03) | .98 | ||||

| Age | .00 (.01) | 1.01 | .00 (.01) | 1.00 | ||||

| Sex | .13 (.19) | 1.04 | .15 (.17) | 1.16 | ||||

| Baseline thorough SSE | 1.79 (.58)** | 5.98 | 1.26 (.53)* | 3.52 |

Note. *p < .05, **p ≤ .01. CI confidence interval; Knowledge of S.L. knowledge of suspicious lesions; OR odds ratio or exp(b); SSE skin self-examination; UC usual care. Sex is coded men = 1, women = −1.

The total effect of treatment condition on SSE at the 48 week follow-up was b = 1.350, se = .391, p = .001, 95% CI .653 to 2.026, OR = 3.857. The total indirect effect of the 8 week mediators was b = .58, indicating that 43% of the total effect of treatment condition on 48 week SSE was mediated by the five mediators together. In this case, the only specific indirect effect that attained statistical significance was SSE self-efficacy (accounting for 34% of the total effect), such that MSS participants were more likely to conduct a SSE because their self-efficacy for conducting SSE was higher at 8 weeks. Although the test of SSE barriers indirect effect was not statistically significant, the bootstrapped 95% CI did not contain zero and so there is some evidence based on this more powerful test of the indirect effect that the intervention increased SSE in part because it reduced SSE barriers.

Finally, although the results are not presented in the tables, we examined the extent to which the process variables assessed at 24 weeks mediated the effect of the treatment on SSE at 48 weeks. Results were very similar to those for the 8 week process variables in that the total effect was b = 1.340, se = .395, p = .001, 95% CI .585 to 2.031, OR = 3.819, the total indirect effect was b = .585, se = .207, p = .005, 95% CI .224 to .981, and the only statistically significant specific indirect effect was for self-efficacy with b = .382, se = .193, p = .048, 95% CI .048 to .820, although again the 95% CI for SSE barriers did not contain zero with b = .184, se = .110, p = .094, 95% CI .045 to .451.

Mediation of the effects of the MSS intervention on sun protection behaviors at the 24 and 48 week follow-ups

Table 4 presents the direct and indirect effects for the mediation models predicting sun protection. (Descriptive statistics for sun protection behaviors at the 24 and 48 week follow-ups, the five mediators assessed at 8 weeks, and the covariates are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The independent groups t-tests indicate that participants in MSS had significantly higher melanoma knowledge scores, perceived melanoma as more controllable, and perceived more benefits of sun protection behaviors at the 8 week time point.) The total effect of the intervention on sun protection behaviors at the 24 week follow-up was b = .194, se = .060, p = .001, 95% CI .078 to .311. Approximately 60% of this total effect of the intervention on sun protection was accounted for by the five mediators together. As with SSE at 24 weeks, there were two statistically significant specific indirect effects: knowledge (22% of the total effect) and sun protection self-efficacy (29% of the total effect). Thus, MSS participants reported higher knowledge and self-efficacy for sun protection behaviors at 8 weeks, and they reported engaging in more sun protection behaviors at 24 weeks.

| Regression coefficients, standard errors, and confidence intervals for direct, and indirect effects of the mySmartSkin (MSS) intervention on 24 and 48 week postintervention sun protection behaviors, as mediated by variables assessed at 8 week follow-up

| . | Predicting 24 week sun protection . | . | . | Predicting 48 week sun protection . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Direct effects . | Indirect effects . | . | Direct effects . | Indirect effects . | . |

| . | b (se) . | b (se) . | 95% CI . | b (se) . | b (se) . | 95% CI . |

| Treatment arm (MSS vs. UC) | .079 (.054) | .066 (.052) | ||||

| Mediators (8 weeks) | ||||||

| Melanoma knowledge | .043 (.017)* | .042 (.019)* | .009 to .089 | .032 (.016)* | .031 (.016) | .004 to .074 |

| Controllability | −.017 (.047) | −.003 (.009) | −.023 to .013 | −.033 (.046) | −.006 (.008) | −.027 to .008 |

| Sun protection benefits | .038 (.048) | .006 (.009) | −.008 to .029 | .026 (.048) | .004 (.009) | −.010 to .025 |

| Sun protection barriers | −.157 (.044)** | .013 (.011) | −.005 to .041 | −.159 (.045)** | .013 (.012) | −.004 to .042 |

| Sun protection self-efficacy | .308 (.042)** | .057 (.025)* | .019 to .124 | .309 (.046)** | .059 (.024)* | .021 to .120 |

| Total indirect | .115 (.038)** | .050 to .200 | .102 (.036)** | .040 to .181 | ||

| Covariates | ||||||

| Disease stage | −.007 (.034) | .006 (.031) | ||||

| Time since surgery | .003 (.005) | .003 (.005) | ||||

| Age | .002 (.002) | .004 (.002) | ||||

| Sex | .002 (.030) | −.025 (.031) | ||||

| Baseline sun protection | .406 (.051)** | .354 (.050)** |

| . | Predicting 24 week sun protection . | . | . | Predicting 48 week sun protection . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Direct effects . | Indirect effects . | . | Direct effects . | Indirect effects . | . |

| . | b (se) . | b (se) . | 95% CI . | b (se) . | b (se) . | 95% CI . |

| Treatment arm (MSS vs. UC) | .079 (.054) | .066 (.052) | ||||

| Mediators (8 weeks) | ||||||

| Melanoma knowledge | .043 (.017)* | .042 (.019)* | .009 to .089 | .032 (.016)* | .031 (.016) | .004 to .074 |

| Controllability | −.017 (.047) | −.003 (.009) | −.023 to .013 | −.033 (.046) | −.006 (.008) | −.027 to .008 |

| Sun protection benefits | .038 (.048) | .006 (.009) | −.008 to .029 | .026 (.048) | .004 (.009) | −.010 to .025 |

| Sun protection barriers | −.157 (.044)** | .013 (.011) | −.005 to .041 | −.159 (.045)** | .013 (.012) | −.004 to .042 |

| Sun protection self-efficacy | .308 (.042)** | .057 (.025)* | .019 to .124 | .309 (.046)** | .059 (.024)* | .021 to .120 |

| Total indirect | .115 (.038)** | .050 to .200 | .102 (.036)** | .040 to .181 | ||

| Covariates | ||||||

| Disease stage | −.007 (.034) | .006 (.031) | ||||

| Time since surgery | .003 (.005) | .003 (.005) | ||||

| Age | .002 (.002) | .004 (.002) | ||||

| Sex | .002 (.030) | −.025 (.031) | ||||

| Baseline sun protection | .406 (.051)** | .354 (.050)** |

Note. *p < .05, **p ≤ .01. Sex is coded men = 1, women = −1. Controllability is controllability of melanoma. CI confidence interval; UC usual care.

| Regression coefficients, standard errors, and confidence intervals for direct, and indirect effects of the mySmartSkin (MSS) intervention on 24 and 48 week postintervention sun protection behaviors, as mediated by variables assessed at 8 week follow-up

| . | Predicting 24 week sun protection . | . | . | Predicting 48 week sun protection . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Direct effects . | Indirect effects . | . | Direct effects . | Indirect effects . | . |

| . | b (se) . | b (se) . | 95% CI . | b (se) . | b (se) . | 95% CI . |

| Treatment arm (MSS vs. UC) | .079 (.054) | .066 (.052) | ||||

| Mediators (8 weeks) | ||||||

| Melanoma knowledge | .043 (.017)* | .042 (.019)* | .009 to .089 | .032 (.016)* | .031 (.016) | .004 to .074 |

| Controllability | −.017 (.047) | −.003 (.009) | −.023 to .013 | −.033 (.046) | −.006 (.008) | −.027 to .008 |

| Sun protection benefits | .038 (.048) | .006 (.009) | −.008 to .029 | .026 (.048) | .004 (.009) | −.010 to .025 |

| Sun protection barriers | −.157 (.044)** | .013 (.011) | −.005 to .041 | −.159 (.045)** | .013 (.012) | −.004 to .042 |

| Sun protection self-efficacy | .308 (.042)** | .057 (.025)* | .019 to .124 | .309 (.046)** | .059 (.024)* | .021 to .120 |

| Total indirect | .115 (.038)** | .050 to .200 | .102 (.036)** | .040 to .181 | ||

| Covariates | ||||||

| Disease stage | −.007 (.034) | .006 (.031) | ||||

| Time since surgery | .003 (.005) | .003 (.005) | ||||

| Age | .002 (.002) | .004 (.002) | ||||

| Sex | .002 (.030) | −.025 (.031) | ||||

| Baseline sun protection | .406 (.051)** | .354 (.050)** |

| . | Predicting 24 week sun protection . | . | . | Predicting 48 week sun protection . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Direct effects . | Indirect effects . | . | Direct effects . | Indirect effects . | . |

| . | b (se) . | b (se) . | 95% CI . | b (se) . | b (se) . | 95% CI . |

| Treatment arm (MSS vs. UC) | .079 (.054) | .066 (.052) | ||||

| Mediators (8 weeks) | ||||||

| Melanoma knowledge | .043 (.017)* | .042 (.019)* | .009 to .089 | .032 (.016)* | .031 (.016) | .004 to .074 |

| Controllability | −.017 (.047) | −.003 (.009) | −.023 to .013 | −.033 (.046) | −.006 (.008) | −.027 to .008 |

| Sun protection benefits | .038 (.048) | .006 (.009) | −.008 to .029 | .026 (.048) | .004 (.009) | −.010 to .025 |

| Sun protection barriers | −.157 (.044)** | .013 (.011) | −.005 to .041 | −.159 (.045)** | .013 (.012) | −.004 to .042 |

| Sun protection self-efficacy | .308 (.042)** | .057 (.025)* | .019 to .124 | .309 (.046)** | .059 (.024)* | .021 to .120 |

| Total indirect | .115 (.038)** | .050 to .200 | .102 (.036)** | .040 to .181 | ||

| Covariates | ||||||

| Disease stage | −.007 (.034) | .006 (.031) | ||||

| Time since surgery | .003 (.005) | .003 (.005) | ||||

| Age | .002 (.002) | .004 (.002) | ||||

| Sex | .002 (.030) | −.025 (.031) | ||||

| Baseline sun protection | .406 (.051)** | .354 (.050)** |

Note. *p < .05, **p ≤ .01. Sex is coded men = 1, women = −1. Controllability is controllability of melanoma. CI confidence interval; UC usual care.

The total effect of treatment condition on sun protection behavior at 48 weeks was statistically significant with b = .168, se = .059, p = .005, 95% CI .058 to .296. The total indirect effect was b = .102, accounting for 61% of the total effect. Sun protection self-efficacy accounted for most of the indirect effect (35% of the total effect). In addition, although the indirect effect for melanoma knowledge was not significant, its 95% CI did not contain zero suggesting that the effect of the intervention on sun protection was partially mediated by knowledge.

Finally, we tested whether the 24 week process variables mediated the effect of the treatment on 48 week sun protection. The total effect was statistically significant with b = .163, se = .059, p = .006, as was the total indirect effect (b = .122, se = .032, p < .001). The significant specific indirect effects were for self-efficacy, b = .072, se = .023, p = .002, 95% CI .031 to .128, and for sun protection barriers, b = .030, se = .015, p = .050, 95% CI .008 to .068.

Discussion

The results of this randomized controlled trial of a web-based fully automated intervention to promote thorough SSE and sun protection behaviors among melanoma survivors suggest that MSS had a significant and beneficial impact on both outcomes at the 24 and 48 week follow-ups. The impact on SSE was apparent at 8 weeks and was sustained over time, with nearly 30% of participants enrolled in MSS reporting conducting a thorough SSE at each follow-up. Comparisons with the limited existing intervention literature are difficult. There are few studies and each differs with regard to inclusion criteria, measurement approaches, intervention targets (patient and partner), delivery (e.g., print material vs. online), and experimental design (e.g., comparison groups). For example, thorough SSE rates at the 1-year follow-up reported by Bowen et al. [15] were similar (37%) to the current study, but the baseline SSE rate in the intervention group in the Bowen et al.’s study [15] was higher (26.1%) than the baseline rate in the intervention group in the current study (5.4%), likely due to varying study eligibility criteria. Robinson et al. [18] reported SSE rates at 4-month follow-up of 30.7% and 64.6% for participants receiving a solo learning versus a dyadic learning intervention, respectively. Of note, however, is the fact that these rates are for having conducted any SSE and do not take into account SSE thoroughness. Loescher et al. [16] reported an increase of 29 percentage points in SSE performance (from 39% to 68%) in their noncontrolled trial of a video intervention for SSE. This study also did not consider the thoroughness of the SSE performed.

Effects of MSS on sun protection behaviors were only present at the 24 week follow-up in analyses that did not control for baseline sun protection and the other covariates. Participants enrolled in MSS reported statistically significant increases in sun protection behaviors compared with UC participant at this time point, but the effect was small. No differences were seen at 8 weeks, and the intervention effect emerged for 48 weeks only when covariates were included in the analysis. The one prior trial that targeted and measured the impact of an intervention on sun protection behaviors found increases in sun protection [15]. However, in that study, each sun protection behavior was analyzed separately and was calculated as an “adherence” score.

MSS had its intended impact on key components targeted in the intervention content: Increasing knowledge about melanoma and characteristics of suspicious lesions, perceived controllability of melanoma, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy (results shown in Supplementary Tables). Mediation effects of SSE self-efficacy on SSE were most consistent. Although the intervention effects were small to moderate, the mediation effect of self-efficacy was large, indicating that much of the behavior change that occurred was accounted for my a change in self-efficacy. There was initial evidence that improved knowledge mediated the 24 week SSE outcomes and that reduced barriers partially mediated the effects of MSS on SSE. Mediation effects of self-efficacy on sun protection were also most consistent. There was also some evidence that improved knowledge mediated the 24 week outcomes, and barriers mediated the 48 week outcomes.

Although there is no prior research documenting mechanisms for behavioral interventions to enhance SSE and sun protection among melanoma survivors, our findings highlight the importance of self-efficacy. Our work extends prior intervention studies by demonstrating that increasing SSE self-efficacy is one mechanism by which this behavioral intervention can improve thorough SSE. Improvements in SSE self-efficacy have been documented in intervention studies of melanoma survivors [18], and self-efficacy is a known correlate of engagement in comprehensive SSE among melanoma survivors [8]. Mediational effects for sunscreen self-efficacy have been demonstrated in a study evaluating the effects of a tailored print and counseling intervention on sun protection among close relatives of melanoma survivors [23], as well as in behavioral interventions to improve sun protection in the general population [35–38]. Our findings extend prior work by assessing self-efficacy for sun protection behaviors other than sunscreen, and illustrate that improving confidence in engaging in other sun protection behaviors, such as wearing hats and shirts and shade-seeking, also appears important. In addition to self-efficacy, results bolster the premise that improving knowledge about what to look for when conducting an SSE and reducing perceived SSE barriers may be important components in behavioral interventions to improve SSE for survivors. Knowledge about what suspicious lesions look like and barriers to performing SSE are documented correlates of SSE [8, 10], but have not been examined as intervention mechanisms in prior work. Although previous work has not suggested that knowledge is associated with engagement in sun protection among melanoma survivors [10, 39],our study provides evidence that this is the case.

It is interesting to discuss putative mediators that did not have significant specific indirect effects: SSE and sun protection benefits and melanoma controllability. Benefits and controllability are known correlates of SSE and sun protection among melanoma survivors [8, 10], and it is surprising that they were not impacted by the intervention (results in Supplementary Tables). Intervention content did not emphasize the role of SSE as way of controlling melanoma. Highlighting the beneficial impact of surveillance on disease controllability may enhance treatment effects.

There are some important strengths and limitations of this study. One key strength is the use of an interactive online intervention targeting both SSE and sun protection behaviors. A second notable strength is the fact that MSS is fully automated, which brings considerable potential to scale it for dissemination. The positive and sustained impact on SSE is particularly impressive given the autonomous nature of this intervention. The sample size is large, and the study included a 48 week follow-up that evaluated the durability of the effects. At almost 41%, the acceptance rate was similar to [40, 41] or higher than [42] acceptance rates reported in other online survivor-focused intervention studies. However, acceptance was lower than other online survivor-focused intervention studies [43–45]. Overall, the follow-up survey completion was high. It should be noted that those who dropped out reported lower levels of sun protection at earlier assessments than those who completed, suggesting that our findings may be less generalizable to survivors with low sun protection behavior. Engagement in MSS was relatively impressive for a fully automated online behavioral intervention, with more than two-thirds of participants completing at least two of the three intervention cores. We found that those who completed the cores were older, suggesting that future enhancements should focus on methods of engaging younger survivors. Evaluations were quite positive, with the information considered highly trusted, useful, well-liked, interesting, easy to understand, easy to navigate, and easy to use, and the online delivery platform was considered appropriate by participants. In terms of weaknesses, the sample was recruited from one state and may not represent the U.S. population. In addition, SSE and sun protection were assessed using self-report, although this is a standard approach in behavioral intervention studies. Finally, the main sun protection content was presented in the final core module, which was only reviewed by 66% of the sample. This limited engagement may have contributed to MSS’ weak effect on sun protection behaviors. Finally, our sample was primarily non-Hispanic white, which is similar to the demographics of melanoma survivors, but not representative of the U.S. population [46].

In summary, the fully automated intervention, MSS, illustrated consistent and durable effects on SSE among melanoma survivors, demonstrated high utilization, and received positive evaluations. Our results suggest that improved self-efficacy was a key active ingredient and provides partial support for the PHM model underpinning the MSS intervention, in that knowledge, barriers, and self-efficacy served as mechanisms for effects. Future studies will benefit from enhanced and earlier presentation of sun safety material, engaging younger survivors, and evaluating how to implement this intervention into survivorship care for melanoma survivors. Our findings have some potential clinical implications in that it may be important to bolster survivors’ knowledge about melanoma and how to identify suspicious lesions, their confidence in what to look for when conducting a SSE, and their confidence in using sun protection in challenging situations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Translational Behavioral Medicine online.

Supplementary Table S1. Descriptive statistics for outcomes, mediators, and covariates for mediational models predicting thorough skin self-examinations within the past 2 months at 24 and 48 week postintervention.

Supplementary Table S2. Descriptive statistics for outcomes, mediators, and covariates for mediational models predicting sun protection behaviors at 24 and 48 week postintervention.

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge the following individuals for their valuable contributions to this project: Pamela Ohman-Strickland, Michelle Hilgart, James Goydos, Paola Chamorro, Babar Rao, Moira Davis, Franz Smith, Ashley Day, Kristina Tatum, Carolina Lozada, Megan Novak, Joseph Gallo, Adrienne Viola, Hope Barone, Sarah Scharf, Kevin Criswell, Michelle Moscato, Evelyn Blas, Cynthia Nunez, Sara Ghauri, Jie Li, Lisa Paddock, Kirsten MacDonnell, Sarah Adams, Gabe Heath, Steve Johnson, Nicole Le, Grace Young, Sara Frederick, and Morgan Pesanelli.

Funding: This research was supported by the Population Science Research Support Shared Resource at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey. This research was facilitated by the New Jersey State Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology Services, New Jersey Department of Health, which is funded by the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute under contract HHSN261201300021I and control no. N01-PC-2013-00021, the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under grant NU5U58DP006279-02-00 as well as the State of New Jersey and the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Authors’ Contributions: Sharon Manne PhD drafted the final manuscript and all authors with the exception of Dr. Coups (deceased) reviewed the manuscript and provided input for its finalization.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rutgers University. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

Author notes

Dr. Coups is deceased.