-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David Chiavacci, Dam break in Japan’s immigration policy: the 2018 reform in a long-term perspective, Social Science Japan Journal, Volume 28, Issue 1, Winter 2025, jyae033, https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyae033

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The 2018 reform is a dam break in Japan’s immigration policy. Previously, for decades, the opening of the Japanese labour market for lower-qualified foreign workers was discussed without any comprehensive reform despite far-reaching proposals. This article discusses this change from a persistent standstill to comprehensive reform by analysing comparatively the frames and institutional setting in earlier immigration debates around 1970, around 1990, and around 2005 with the debate in the late 2010s. It argues that the persistent stalemate on the most hotly debated issue of immigration policy was due to the diversity of frames with very different policy implications and an institutional fragmentation in policy-making without any pivotal policy entrepreneur. The comprehensive reform of 2018 is the result of a window of opportunity by the conjuncture of a declining security frame as the main counterargument and by the centralization of decision-making in the core executive in the later years of the second term of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō (2012–20) on the level of institutional setting. Abe and his entourage were reluctant policy entrepreneurs who only realized the 2018 reform because of pressure and the absence of any other policy option. Still, they fundamentally changed the framework in Japanese immigration policy.

1. Introduction

In 2018, a new reform in Japan’s immigration policy introduced two new visa categories and a quota system for lower-qualified foreign workers. It also established the Immigration Services Agency (ISA) as a new government organization in charge of Japan’s admission and integration policy. The scope and speed of this reform is remarkable. While the Japanese immigration policy regarding lower-qualified foreign workers was marked for decades by a persistent standstill despite far-reaching proposals, the developments of the late 2010s comprised a fundamental reform that the government rushed through from first announcement to parliamentary adoption in less than a year. How can this transformation of Japan’s admission policy from a persistent standstill to comprehensive and sudden reform be explained? This article analyses this question by comparing the frames and institutional setting of the reform debate of the late 2010s to the three policy debates that took place around 1970, 1990, and 2005. By doing so, this paper elucidates the continuities and changes in immigration policy that have taken place during the past fifty years as well as the specifics of the window of opportunity in the late 2010s.

Conceptually, this article differentiates highly qualified versus lower-qualified foreign workers. This distinction is based on Japan’s Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (Shutsunyūkoku kanri oyobi nanmin nintei hō; hereafter immigration law), which specifies a ‘positive list’ (Kondo 2002: 432) of job fields, for which foreign workers can get a working visa. All other foreign workers who do not satisfy these strict requirements of highly qualified workers are not eligible for a working visa status. This positive list system was for decades the central reference point in the immigration debates, and the official and oft-repeated mantra of the conservative establishment that Japan only accepts highly qualified foreign workers.1

This explains why the 2018 reform is the ‘most significant change in Japan’s post-war migration history’ (Oishi 2021: 2259). According to well-established estimates (Bungei Shunjū 2008: 295), already before the reform and in clear contradiction to the valid immigration law, about 80 per cent of foreign labour working in Japan did not meet the requirements of the immigration law. Side doors for lower-qualified foreign workers resulted in a clear gap between Japan’s official immigration policy and its real immigration policy. By introducing the two new visa categories and a quote system, Japan’s front door for lower-qualified foreign workers has finally been opened and the fundamentals of its admission policy reformulated (Takaya 2023).

Throughout the reform, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō (2012–20) repeatedly maintained that this reform ‘is not an immigration policy’ (imin seisaku de wa nai) in the meaning of permanent settlement (Strausz 2021: 269). In fact, the new programme for lower-qualified foreign workers is mainly a guest worker programme that limits their stay to a maximum of five years and grants them no right to bring their families to Japan. However, contrary to Abe’s statement, through the 2018 reform lower-qualified foreign workers in construction and shipbuilding can unlimitedly renew their visas, which opens for them a path for permanent settlement and family reunification.

The establishment of the ISA in the 2018 reform shows the increasing strategic importance attributed to the admission and integration policy. It has the duty of planning and drafting basic and comprehensive policies, to directly assist the cabinet, and to coordinate among ministries and agencies in the immigration policy field. With a more autonomous ISA as an external agency, the defensive influence of the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) might be reduced in immigration policy (for a detailed discussion, see Akashi 2020: 72–75).

Finally, the 2018 reform of the immigration law has handed much more decision-making power to the executive. In June 2023, the path for permanent settlement and family reunification has been expanded to nine additional industries (building cleaning, automobile maintenance, aviation, lodging, agriculture, fishing, food, and beverage manufacturing, restaurant business as well as materials, industrial machinery, electrical and electronic information-related manufacturing) (ISA 2023b). This important step towards a much broader permanent immigration policy for lower-qualified foreign workers is based on a cabinet decision without consultation and approval in the parliament. The executive branch also decides future quotas for lower-qualified foreign workers. In fact, in March 2024, it decided to more than double the entry cap of lower-qualified foreign workers to 820.000 in the next five years, 2024–8, and to add four new industries (ground transportation, rail, forestry, and lumber) to the programme (Yuasa 2024).

To sum up, the 2018 reform is not the ‘big bang’ in immigration policy in Japan. Japan has been for decades an immigration country and accepted, in contradiction to its immigration law and official immigration policy, well before the reform of 2018 lower-qualified foreign workers through side doors. Still, the 2018 reform is a dam break in immigration policy that not only opened the front door for lower-qualified foreign workers but has also established a path for their permanent settlement. It has also changed the institutional setting of immigration policy by establishing the ISA and handing much more power to the executive, which has already been used to significantly expand the new path to permanent settlement of lower-qualified foreign workers. The cabinet also introduced much larger quotas for them.

What is the contribution of this article to the state of research? Japanese immigration policy and its change over time have been examined in several comprehensive studies (Shimada 1993; Iguchi 2001; Akashi 2010; Chiavacci 2011; Strausz 2019), but none of them covers the 2018 reform. Scholarly analyses that discuss the 2018 reform from a long-term perspective of immigration policy development focus on the content of the reform and elaborate issues that have not yet or not sufficiently been addressed by the reform, hence not analysing the policy process in detail (Endoh 2019; Takaya 2019; Akashi 2020; Burgess 2020; Hamaguchi 2020; Strausz 2021). A few papers have addressed the actual policy process. Oishi (2021) discusses the discourses behind the 2018 reform and argues that the Abe government used the ambiguous meaning of skill for redefining foreign workers, which had before been categorized as unskilled, as work-ready and possessing certain expertise in reaction to national and regional demands. According to Shilipova (2021), the 2018 reform and other steps to liberalize the immigration policy under Abe can be explained as being part of his growth strategy (Abenomics) in the context of demographic decline and rising labour market shortages. Similarly, Song (2020) maintained that Japan’s demographic crisis and increasing demand for foreign workers by businesses are important, but also stresses that the leadership of Abe was another key factor for the 2018 reform. Still, all these contributions focus on the policy-making of the 2018 reform in its current context and do not analyse it from a long-term perspective. This paper addresses this research gap. It discusses and compares the frames and institutional setting of immigration policy during four phases of intensive labour immigration debates in the last fifty years. It will show the major changes on a discursive and institutional level and explain why in the late 2010s the decade-long deadlock was overcome and the front door for lower-qualified foreign workers was finally opened.

The analytical framework of this paper draws on the multiple streams approach of John W. Kingdon and his concept of ‘window of opportunity’ (Kingdon 1984; see also Zahariadis 2007). According to the multiple streams approach, windows of opportunity arise when policy entrepreneurs successfully couple three independent streams (problems, policies, and politics) in a public policy field (see also Cohen et al. 1972 for the original garbage can model on organizational decision-making). Without coupling, policy reform is not possible. However, the theoretical model developed for the analysis in this article differs fundamentally from Kingdon’s original approach for two reasons. First, Kingdon’s (1984) model is based on his analysis of transportation and health policy in the USA over a short period of four years (1976–9). Immigration policy is a more complex and controversial policy field than health or transportation policy and, as will be discussed in more detail below, is characterized by a fundamental disagreement on its objectives. There is no consent on a solution because there is no common understanding of what the problem actually is that needs to be solved. Therefore, the two streams of problems and solutions (or policies) have been combined into a first level of immigration frames. Second, Kingdon (1984) does not pay any attention to institutional changes in the policy fields due to the short period under investigation in his study. In this paper, Japanese immigration policy is analysed over half a century. The immigration policy field and its main actors have changed considerably over this long period. Therefore, the stream of policy (or policy-makers) and the policy field have been combined into a second level of institutional setting. Thus, this paper analyses Japan’s immigration policy over its four debates on two levels of analysis: (1) frames on immigration and (2) institutional setting of immigration policy. It argues that immigration policy was marked for decades by a discursive diversity of contradictory frames and an institutional segmentation that led to the deadlock in the admission policy. The frame diversity and the institutional fragmentation reinforced each other. However, in the late 2010s, a window of opportunity developed thanks to the decline of the security frame as the main counter argument to immigration reform in conjuncture with the institutional centralization through the establishment of a powerful core executive. Abe and his entourage were very reluctant and even unwilling policy entrepreneurs. They did not actively create the coupling but used the window of opportunity once they realized that no other policy options were available.

On a methodological level, this article is based on academic literature, mass media publications, opinion surveys, and qualitative analyses of primary sources like policy documents and statistics. For identifying the salience of the immigration issue in public debate and among policy-makers, it utilizes quantitative analyses of newspaper articles in Japan’s four major national dailies and the number of substantial policy proposals.

2. Immigration debates: five decades and four debates

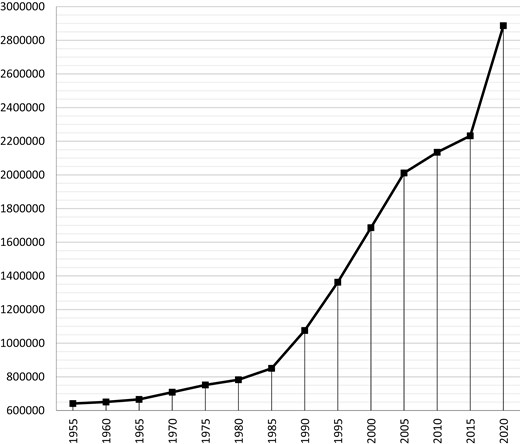

In the second half of the 1980s, Japan was transformed into an immigration country (see Fig. 1). Before this, the slow growth of registered foreign residents between 1945 and 1985 was due to the demographic expansion of Korean and Chinese old comers who had moved to Japan’s main territories (naichi) from its outer territories (gaichi) during the colonial period and their descendants. Then, during the bubble economy years, new immigration started, and the rise of foreign residents gained a completely new dynamic. In fact, Japan has been among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) top ten destination countries (according to net migration inflow) for decades (OECD 2016: 320).

Registered foreign residents in Japan, 1955–2020. Source: ISA (2023a: 22).

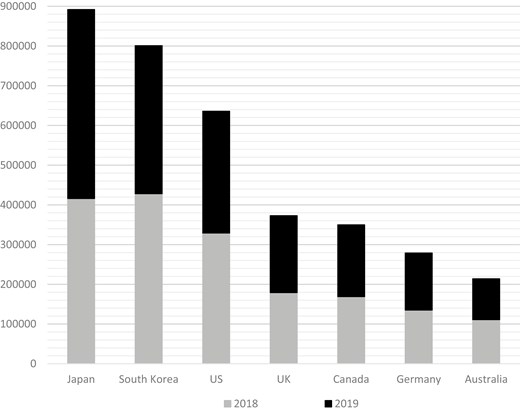

Regarding Asian migrants, in the two years before the implementation of the reform, Japan was already the main destination among advanced industrialized countries (see Fig. 2). Leaving aside the Great Recession of 2007–9, which led to a temporary slowdown in immigration, the growth of foreign residents has been continuous between 1985 and 2020 (see Fig. 1). This is an indicator that Japan is a country of immigration whose economy has a structural dependence on foreign workers beyond business cycles.

Main destinations among advanced industrialized countries for Asian migration, 2018–2019. Source: ADBI et al. (2021: 23).

As said above, most of these new foreign workers are active in job fields not included in immigration law for working visas and came to Japan through three well-established side doors for lower-qualified workers: foreign students including language students, foreign interns, and foreigners of Japanese descendants (nikkeijin). The common saying in migration studies that ‘nothing is as permanent as temporary migration’ also holds true for Japan. Although new immigrants enter Japan with temporary visas, new inflows have resulted in an increase in long-term foreign residents, including many lower-qualified foreign workers.

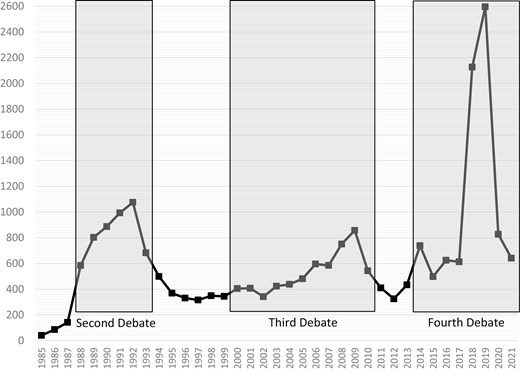

In contrast to the nearly linear increase of foreign residents, public and political debate has been characterized by three periods of high intensity in the era of Japan as a new immigration country (see Fig. 3 and Table 1). When also including the discussions in the final years of Japan’s high growth period (1960–73), four policy debates can be identified as having occurred during the last fifty years.

| Period . | Proposals . | Proposals per year . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate phase | 1984–8 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Second debate | 1989–93 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Intermediate phase | 1994–8 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Third debate | 1999–2003 | 19 | 3.8 |

| 2004–8 | 34 | 6.4 | |

| Intermediate phase | 2009–13 | 8 | 1.6 |

| Fourth debate | 2014–8 | 21 | 4.2 |

| Period . | Proposals . | Proposals per year . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate phase | 1984–8 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Second debate | 1989–93 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Intermediate phase | 1994–8 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Third debate | 1999–2003 | 19 | 3.8 |

| 2004–8 | 34 | 6.4 | |

| Intermediate phase | 2009–13 | 8 | 1.6 |

| Fourth debate | 2014–8 | 21 | 4.2 |

Note: The data from 1984 to September 2007 is based on the list of substantial proposals in the research material prepared by the National Diet Library (NDL 2008). This list does not include all immigration policy proposals. For example, Shimada (1993) lists 36 reform proposals from 1989 to March 1993, but only eleven of those are in the NDL list. The criteria for identifying the substantial reform proposals are not explained in NDL (2008), but the authors seem to have weighted three criteria for their selection: (1) the political influence of the actors producing the report; (2) innovative content of the proposal; (3) size of the report. Based on these criteria, the substantial reform proposals from October 2007 to 2018 have been identified and included in the list.

Source: NDL (2008) and own compilation.

| Period . | Proposals . | Proposals per year . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate phase | 1984–8 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Second debate | 1989–93 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Intermediate phase | 1994–8 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Third debate | 1999–2003 | 19 | 3.8 |

| 2004–8 | 34 | 6.4 | |

| Intermediate phase | 2009–13 | 8 | 1.6 |

| Fourth debate | 2014–8 | 21 | 4.2 |

| Period . | Proposals . | Proposals per year . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate phase | 1984–8 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Second debate | 1989–93 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Intermediate phase | 1994–8 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Third debate | 1999–2003 | 19 | 3.8 |

| 2004–8 | 34 | 6.4 | |

| Intermediate phase | 2009–13 | 8 | 1.6 |

| Fourth debate | 2014–8 | 21 | 4.2 |

Note: The data from 1984 to September 2007 is based on the list of substantial proposals in the research material prepared by the National Diet Library (NDL 2008). This list does not include all immigration policy proposals. For example, Shimada (1993) lists 36 reform proposals from 1989 to March 1993, but only eleven of those are in the NDL list. The criteria for identifying the substantial reform proposals are not explained in NDL (2008), but the authors seem to have weighted three criteria for their selection: (1) the political influence of the actors producing the report; (2) innovative content of the proposal; (3) size of the report. Based on these criteria, the substantial reform proposals from October 2007 to 2018 have been identified and included in the list.

Source: NDL (2008) and own compilation.

Salience of immigration issue in public debate, 1985–2021. Note: The measurement of the immigration issue salience covers both admission and integration policy. ‘Foreign workers’ (gaikokujin rōdōsha) is utilized as a key phrase for admission policy and ‘multicultural society’ (tabunka kyōsei) as a key phrase for integration policy. These two key phrases are selected instead of other possible key phrases like ‘gaikoku jinza’ (foreign human resources) or ‘tōgō’ (integration) because they have been prominent and constantly used in public immigration debate over the whole period of over 35 years covered in the analysis. Both parts of immigration policy (admission and integration policy) are covered because they are in general merged in public debate. Source: Own full-text research in the electronic databases Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search (Asahi Shinbun), Maisaku (Mainichi Shinbun), Nikkei Telekom 21 (Nihon Keizai Shinbun), and Yomidas Rekishitan (Yomiuri Shinbun).

The first debate started in the late 1960s and ended with the first oil price crisis and economic recession of 1973. As this debate was clearly smaller in scale and intensity compared to the three later ones, it is also called the ‘small debate’ (Chiavacci 2011: 78). In the later 1970s, refugee policy became an important topic in Japanese politics in view of the Indochinese refugee crisis, and in 1982, Japan joined the Refugee Convention and Refugee Protocol. The admission of foreign workers did not return to the national policy agenda for fifteen years, however.

In the second half of the 1980s, the beginning of new immigration led to a second debate about immigration and its desirability, which was on a completely new scale. The average number of articles on immigration issues per year in the four largest newspapers skyrocketed more than 10-fold, from about eighty per year in 1985–7 to about 840 in 1988–93 (see Fig. 3). A similar but less pronounced development happened on the policy-making level, with the number of substantial policy proposals per year more than doubling from the 1984–8 period to the 1989–93 period (see Table 1).

From 1994 to the late 1990s, the public debate on immigration did not completely disappear or fall back to the level it was before 1988, but a decline is clearly visible (see Fig. 3). The average number of yearly newspaper articles fell by more than half to about 370 in 1994–9. At the policy-making level, the drop was even more remarkable, with only one substantial reform proposal published in 1994–8 (see Table 1).

The turn of the millennium marked the beginning of the third immigration debate, which covered a long period of nearly ten years and can be divided into two phases. In the first, preliminary phase, the increase in public discussions on immigration was rather limited (see Fig. 3). The number of newspaper articles on immigration grew by only 30 per cent to about 400 articles per year in 2000–5. The second, more intensive, main phase saw an additional two-thirds increase to about 670 articles in 2006–10.

When comparing public debate and policy-making, the third immigration debate was much more intensive on a policy level than in the public sphere. While public discussions did not return to the levels of the second debate, the number of substantial policy proposals strongly increased and reached a new peak (see Table 1). Indeed, the latter grew exponentially during the preliminary phase in 1999–2003 compared to the period before and further increased during the main phase in 2004–8, attaining a level that was nearly three times as high as during the second debate. During the main phase of the third debate, a substantial reform proposal was published every second month. While the second debate was primarily a public debate, the third debate was more intensive among policy-makers.

In the following years of the early 2010s, the immigration debate remained at a certain level, even more so than in the 1990s. Still, in comparison to the period of the third debate, there was a clear drop in intensity, and newspaper articles on immigration fell by over 40 per cent to about 390 articles per year in 2011–3 (see Fig. 3). The reduction in policy-making was even more pronounced, with the number of substantial policy proposals in 2009–13 dropping to one-fourth of those in the period before (see Table 1). This interphase only lasted a few years, however, and from 2014 onwards, the fourth immigration debate began to take place. Even when leaving aside the two exceptional years of 2018 and 2019, the number of newspaper articles on immigration reached a yearly average of about 660 articles in 2014–7 and 2020–1 (see Fig. 3).

The years of 2018 (over 2,100 articles) and 2019 (nearly 2,600 articles) were on a different scale. Even in comparison to public discussion during the second debate, this was a 3-fold increase. The intensity of public debate during these two years is a good indicator of the scope and speed of the 2018 immigration reform that obviously caused very big waves in public discussions.

On a policy-making level, the number of reform proposals substantially increased during the five-year period of 2014–8 to 4.2 per year on average. This was still substantially lower than the main phase of the third debate a decade earlier, however, which had an average of 6.4 proposals per year (see Table 1). This discrepancy between the public and political debates is a good indicator of the substantially different characteristics of the third and fourth debates. The main phase of the third debate was very intensive on a policy level and marked by many proposals, some of which were far-reaching. None of them were realized, however.

In contrast, the fourth immigration debate was primarily characterized by the culmination of one fundamental policy proposal, which was formulated and implemented very quickly. This shows how the policy-making process changed between the third and fourth debates, something we return to when discussing the institutional setting of Japan’s immigration policy in the fourth section of this article. First, the frames in immigration policy are discussed in the next section.

3. Diverse and moving frames of immigration: from deadlock to prioritization

Ethnonationalism (minzokushugi) is generally identified as the ideational basis of Japan’s restrictive immigration policy, and especially of the preferential treatment of nikkeijin (e.g. Mosk 2005: 153–154; Burgess 2020). In academic publications, Japan is regarded in this dominant ethnonationalist perspective as a nation defined by its ethnic homogeneity and principle of descent or ‘right of blood’ (jus sanguinis). Such a perspective is much too simple, however, and does no justice to the complex immigration debates in Japan (see also Kalicki 2021). Ethnonationalism plays an important role in Japan’s immigration policy, but like in all other advanced industrial societies, immigration is a thorny issue debated hotly from very different and often contradictory perspectives. It is this diversity in frames of immigration rather than a predominance of ethnonationalism that is the main characteristic of Japan’s immigration policy on a discursive level.2

As Boswell (2007) argued so elegantly in her seminal paper, modern nation-states, including Japan, are confronted with the task of fulfilling different functional imperatives in migration to retain legitimacy.3 This functional diversity of states leads to contradictory frames of immigration and an imminent tension in the field of immigration policy. In the case of Japan’s immigration policy, we can identify four main frames.

The first frame is national identity and cultural self-definition. In this identity frame, ethnic homogeneity (tan’itsu minzoku) and ethnonationalism are the dominant ideas. Still, ethnonationalism is only one perspective on identity and nation among others in Japan’s nation-building process and modernity (Oguma 1995; Doak 2007). It became the dominant perspective in national identity and self-understanding from the 1970s onwards, especially among the conservative establishment (Aoki 1990; Oguma 1995: 339–361; Lie 2001: 130–136). Ethnic homogeneity was not only regarded as unique for Japan but was also stressed as a central factor explaining Japan’s economic success story based on closing ranks and the absence of ethnic tensions. Obviously, immigration and the incorporation of foreign residents into society is a challenge for a nation with such a mono-ethnic self-definition.

A second frame, and arguably the most important frame in the case of Japan, is economic development and the resulting social cohesion. In fact, this growth frame was and is the dominant frame in the self-understanding of the Japanese nation that unites as a social contract the conservative establishment and the population. After the defeat and destruction of World War II and the delegitimization of the former drive for military hegemony, Japan prioritized economic growth over military power in its reinvention and rebuilding (Yoshida doctrine) and tried to realize this target through continuity of industrial policy and state guidance from war years (Johnson 1982; Pyle 1992).

In 1960, this developmental path experienced a crucial redirection when the then Prime Minister, Hayato Ikeda (1960–4), introduced the principle of shared growth, a socially embedded variant of the Yoshida doctrine, with the Income Doubling Plan (shotoku baizō keikaku) in reaction to the rampant conflicts of the Mi’ike strike and the Anpo protest (Chiavacci 2022). Growth was no longer an instrument to restore Japan’s power but a tool for achieving general wellbeing and social cohesion. The conservative establishment and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) became the guarantors of economic growth, in which the hard work of the population would be translated into mass consumerism and general upward mobility.

After the bubble economy burst in the early 1990s, maintaining this social contract became much more complex in view of the increasing signs of social disintegration. Shared growth remains the most important pillar of the Japanese nation, however. For example, the economic strategy of Abenomics under former Prime Minister Abe was basically an attempt to return to the good old times of full shared growth (Ido 2017; Shibata 2017; Chiavacci 2021a). This social contract of shared economic growth, and not ethnic nationalism, is the most influential frame in immigration policy that led to Japan’s dual and restrictive immigration policy. Highly qualified foreign workers are welcome because they are believed to contribute to economic growth, raise productivity, and even produce additional jobs for Japanese workers, whereas lower-qualified foreign workers are said to become a welfare burden, deteriorate the working conditions of the native workforce, and even be a drag on increasing productivity. Especially through their negative effects on lower-qualified Japanese workers, they would undermine the social contract of shared growth and social cohesion.

National and public security is the third frame in Japan’s immigration policy. After 9/11, many studies identified a securitization of migration in Western advanced industrial societies (Faist 2006; Bourbeau 2011). In the case of Japan, however, security issues and public order played a central role in immigration policy much earlier. In the early postwar era, the ruling conservatives were confronted with a Korean minority that mainly identified with communist forces in Korea, and later with North Korea. During the early years of the Cold War, which was anything but cold in East Asia, Japan’s police repeatedly clashed violently with Korean residents who wanted to establish their own school system to maintain their cultural and political identity (Takemae 2002: 462–464). The conservative government at the time regarded them as a security risk and possible fifth column and denied them Japanese citizenship. Then Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru (1946–7 and 1948–54) made this view clear in Diet deliberation in October 1951: ‘There are not a few [Korean residents in Japan] who, whenever there is a protest, are involved and participate in local disturbances and so on’ (House of Councillors 1951; see also Tanaka 1995: 72–74).

In August 1952, the government moved the migration bureau from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) to the MOJ with the goal of increasing state control of irregular immigration and foreign residents (Ikuta 1992: 24). As the ministry in charge, the MOJ retained a security perspective on immigration, and during the 1960s and early 1970s, it tried several times to reinforce immigration regulations to gain even stricter control over immigration and foreign residents (Akashi 2010: 69–72). In recent decades, the security frame remained of crucial importance, and fully controlling immigration to guarantee national security and public order continues to be a central goal in Japanese immigration policy.

The fourth frame in Japan’s immigration policy is foreign policy and international prestige. In the 1970s, Japan’s conservative establishment not only started to stress Japan’s unique ethnic homogeneity as a defining element of its identity and economic success story, but in a second and somehow contradictory turn, the same elite also envisioned a much more leading role for Japan in international relations in accordance with its increasing economic might (Gurowitz 1999; Chiavacci and Soboleva 2023).

To establish itself as a leading nation in the international community, however, Japan also needed to redeem itself as a model citizen complying with international norms including human rights in view of its past as an expansive and brutal military power. An exemplary person taking this international standing frame inside the conservative establishment was Sonoda Sunao, who served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs (1977–9 and 1981) and the Minister of Health and Welfare (1980–1) and had a leading role in Japan joining the Refugee Convention (Suefuji 1984). Although Japan’s foreign policy considerations and international standing is now less present, they continue to play a significant role in immigration policy-making.

Over the past fifty years, the relative importance of these four frames has changed, and the growth framework in particular has been reconceptualized fundamentally over time. The diversity of frames represents a continuity in the four debates. Nevertheless, the focus of the debate has moved from diametrically opposed arguments within the growth framework (first debate around 1970) to a very pronounced degree of diversity of all four frames (second debate around 1990) to contrast between pro-arguments based on the growth frame and contra-arguments based on the security frame (main phase third debate around 2005) to a prioritization of a reconceptualized growth framework over a weakened security framework (fourth debate in the late 2010s).

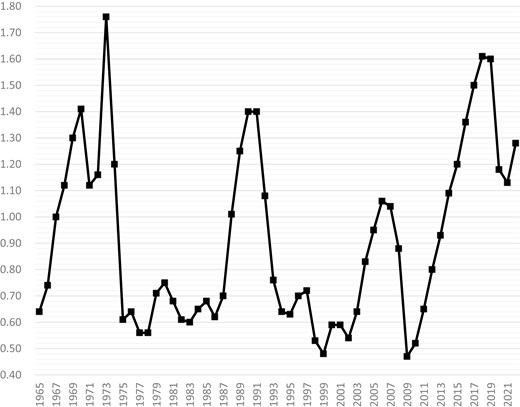

During the first immigration debate around 1970, the growth frame prevailed, but based on this frame, different actors developed diametrically opposed arguments (Akashi 2010: 72–76; Chiavacci 2011: 75–83). In the late phase of its high growth, Japan experienced an increasingly acute labour shortage, as indicated by the increasing ratio of job openings per applicant (see Fig. 4). It reached its Lewis turning point, and its former rural surplus labour was absorbed into the urban economy (Watanabe 1994).

Job openings-to-applicant ratio, 1965–2022. Source: JILPT (2023).

After the normalization of the bilateral relations in 1965, South Korea proposed that Japan accept more Korean interns for skills transfer and development assistance. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Japan, which were forced to substantially increase salaries because of the labour shortage, were very open to this request (Ochiai 1974: 239–240; Yoshimura 2004: 227). Japan’s employer association (Nikkeiren) also called for an expansion of the foreign intern system as a measure against the acute labour shortage (Yoshimura 2004: 228–229). Other influential players of the conservative establishment like the Japan Productivity Center even started to float the idea of guest worker programmes to be able to maintain high growth following the successful example of the Western economies (JPC 1970).

However, labour unions were strictly against opening the labour market to foreign workers, and the Ministry of Labour (MOL) also strongly opposed such ideas (Utsumi 1988: 170). They all argued that the introduction of foreign workers would worsen the working conditions and salaries of Japanese workers and, hence, undermine the painstakingly built social contract of shared growth. Even more pronounced was the criticism by the New Left and its social movements at the time. For example, these activists denounced the plan to introduce more Korean health workers as interns in Japan as a form of forced labour, like the forcibly recruited Korean workers during the war years (KDSYK 1974; OISR 1989).

Since guest worker programmes had a positive image and seemed to be strictly controllable at the time, there was not much concern that an influx of foreign guest workers might impact national security or public order. Furthermore, around 1970, Japan experienced not only high growth and labour shortages, but it went through a high point in its postwar protest cycle with strong environmental movements against rampant pollution, a large national anti-Vietnam War movement (Beheiren), and an increasingly radicalized student movement from which violent terrorist groups emerged (Kajita 1990; Nishikido 2012; Chiavacci and Obinger 2018). In short, Japanese society was by no means seen as a haven of public safety and order at the time, as during later immigration debates. In view of the pronounced level of unrest and violence, how could foreign guest workers or foreign interns have undermined ‘public order?’

As discussed above, neither the identity frame of ethnic homogeneity nor the international standing frame was fully established around 1970. Hence, such perspectives were hardly mentioned during the first debate. Nevertheless, the conservative establishment was well aware that anti-Japanese resentments were growing in many Southeast Asian countries in the late 1960s. In view of Japan’s rising exports and direct investments, it was increasingly perceived once again as an aggressive power that wanted to dominate Southeast Asia, only this time economically and no longer with military force as in the war years. This criticism also included denouncing Japan’s foreign intern system as an instrument to exploit foreign workers as cheap labour. In 1974, these anti-Japanese feelings culminated in violent demonstrations and massive riots in Bangkok and Jakarta during the state visit of the then-Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei (Avenell 2018: 52). Japan was therefore in a delicate diplomatic situation during these years, which could only worsen with a massive expansion of the foreign intern system or an introduction of guest worker programmes.

The first oil price shock of 1973 led to a short but sharp recession and a sudden end of the labour bottleneck (see Fig. 4). The first immigration debate was over before it really began. Ideas of introducing a guest worker programme or expanding the foreign intern system vanished into thin air. In view of the strong international and national criticism, the MOL, the MOJ, and the Ministry of Health made the joint decision in 1974 not to accept foreign nursing staff as interns until further notice.

In 1983, before the second immigration debate had begun, an enhanced foreign student acceptance policy introduced under Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro (1982–7) unintentionally opened the first side door for lower-qualified foreign workers. One of Nakasone’s pet policies was the ‘internationalization’ (kokusaika) of Japan. Its aim was to enable Japan to assume a leading role in the international community in line with its economic strength.

As part of this goal, a plan for 100,000 foreign students was introduced to increase the number of self-financed foreign students. After finishing their studies and returning to their home countries, it was thought that they would function as a bridge for Japanese investment and bilateral relations (Tanaka 1995: 181–191; Akashi 2010: 83–86; Chiavacci 2011: 98–101). In accordance with this plan, the number of foreign students and Japanese language students increased, but many of these ‘students’ were much more interested in earning money than in getting educational degrees in Japan. Hence, a policy that should have increased Japan’s international outreach and influence, resulted in an internationalization of Japan’s labour market. Moreover, in the late 1980s, the bubble economy with its excess investments brought the labour shortages back (see Fig. 4). Although the manpower bottleneck did not reach the same level as in the early 1970s, the rising labour demand was not met by foreign students. In comparison to around 1970, Japan was now much more regionally integrated, foreign worker demand in the oil-exporting countries in the Middle East had fallen, and international migration had been re-established as a behavioural pattern in East Asia (Chiavacci 2021b). This resulted in a rapidly increasing number of irregular immigrants (see Fig. 5).

Recorded irregular immigrants, 1988–2023. Source: ISA (2023a: 48) and Tanaka (1995: 221).

This sudden inflow of foreign workers and apparent loss of state control over immigration led to the second immigration debate.4 This debate was clearly reactive in character (Hachiya 1992), asking the question: How should Japan respond to the inflow of foreign workers? Should Japan open itself and its labour market more to foreigners as part of the internationalization drive introduced by Nakasone? Most importantly, should Japan start to accept lower-qualified foreign workers (called ‘simple workers’, tanjun rōdōsha at the time)?

In comparison to the first debate around 1970 but also the later debates, this second debate around 1990 was more diverse and all four frames were strongly present and influential in the controversial public and political discussions. The two clear lines of argument against accepting lower-qualified foreign workers were based on the security and identity frames. From the very beginning of the debate, an increase in foreign residents and especially the uncontrolled inflow of irregular workers was seen as a security problem. As early as 1987, the National Police Agency (NPA) started to devote a separate chapter in its police white book to foreigner crime, in which it established a link between the rising number of foreigners and increasing criminality (NPA 1987). The NPA created a narrative that foreigners, especially irregular immigrants, have a higher propensity to commit crimes including violent ones. Although these claims are not supported by careful analysis (Yamamoto 2004), the narrative became soon common knowledge.

From an ethnonationalist perspective, the inflow of immigrants was described as potentially disruptive to Japan’s cultural and social homogeneity. In view of the side door established for nikkeijin during the second debate, it is often assumed that this identity frame played a dominant role. However, an exemption rule for nikkeijin was absent in public discussions. Up to the 1990 immigration law reform, not one single article mentions nikkeijin as a possible solution to the high demand in the labour market in the over 1,500 newspaper articles on immigration published in the four leading national dailies. Only during the implementation of the law, nikkeijin became a topic inside the LDP and was presented as the solution to the immigration issue from an ethnonationalism perspective (Nojima 1989: 98):

The plan to actively absorb the nikkeijin as workers will certainly and quickly have an effect on solving the labour shortage. One important reason against opening Japan’s labour market is that admitting large numbers of Asians with a different culture and behavioural patterns could easily lead to discrimination and conflict and destroy the population structure of Japan as an ethnically almost homogeneous nation. But if they are nikkeijin, even if some among them do not know Japanese well, then this is unlikely to become a big problem.

The line of argument clearest in favour of opening the labour market to lower-qualified workers was related to foreign policy consideration. To fulfil its leadership role in the international community, and especially vis-à-vis developing countries in East and Southeast Asia, Japan should be like other advanced industrial societies and accept the inflow of foreign workers: ‘It is also necessary to consider Japan within the context of Asia. […] The time when Japan only needs to think about its own country is over. As an economic superpower, Japan also has responsibilities’ (Nihon Keizai Shinbun 1988a; see also MOFA 1989). This line of argument as part of the international standing frame represented a continuity with the debate on human rights and refugee policy in the 1970s and early 1980s that had led to Japan’s accession to the most important international human rights treaties and the Refugee Convention (Tsutsui 2018; Chiavacci and Soboleva 2023).

The most influential frame remained arguably the growth frame, which, however, was again like in the first debate marked by opposite positions and contradiction arguments. SMEs and their political supporters argued that the time was ripe for opening the labour market (Hachiya 1992: 44). In view of the labour shortage, lower-qualified foreign workers were needed to keep the Japanese economy running. The economic advantages of an active immigration policy would outstrip the disadvantages. However, the perception of an active immigration policy had turned much more negative than in the first debate. Many feared that Japan could lose control over immigration like in the case of the guest worker programmes in Western advanced industrialized countries after the first oil price shock. This would have a negative impact on the native workforce and would undermine the social contract of shared growth. Not only the labour unions (Nimura 1992) and the MOL (1988), but also most large companies and Nikkeiren (1990: 38) took such a position:

The most important aspect of the foreign labour problem is that it should not be viewed solely from a labour supply and demand perspective. If we look at the experience of all other countries, it becomes clear that recruiting foreign labour because of a labour shortage is a fundamental mistake.

Employers were relatively clearly divided by size. For example, in the construction industry, which was suffering from severe labour shortages at the time, the SMEs pushed for the opening of the labour market, but the large construction companies voted against accepting foreign workers (Nihon Keizai Shinbun 1988b). They argued that an inflow of foreign workers into construction would negatively impact working conditions in the sector and further increase recruitment problems by discouraging young Japanese workers from going into construction.

In the early 1990s, the controversy over immigration based on the growth frame became even more heated. The 1990 reform of the immigration law had no dampening effect on irregular immigration as had been hoped. On the contrary, in only two years, visa overstayers almost tripled from about 100,000 in 1990 to nearly 300,000 in 1992 (see Fig. 5). SMEs and their political supporters, especially inside the LDP, renewed and heightened their demands and political pressure for a more open admission policy for lower-qualified foreign workers. Proponents also argued with the security frame. In their view, Japan was no longer able to control the immigration pressure from outside with the existing policy framework. This loss of control over immigration let not only to worsening labour conditions but also undermined public order and security.

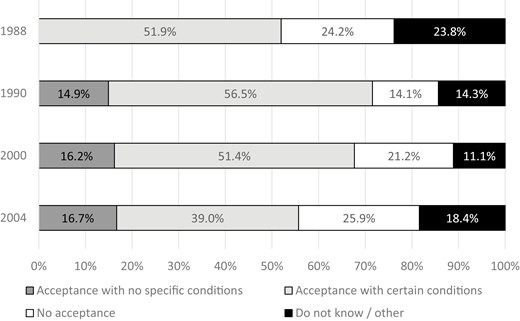

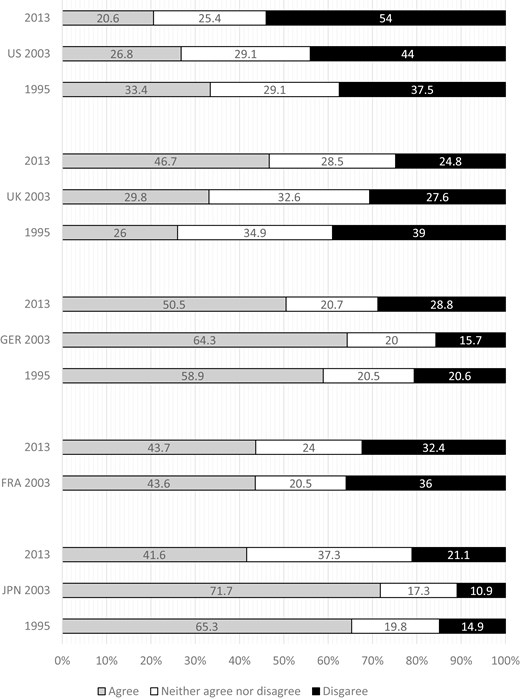

The large-scale surveys of the Cabinet Office (CAO) on the foreign worker issue provide insight into public opinion and the relevance of the four frames in the public eye. When respondents were asked in the first survey in 1988 about their attitudes to accepting unskilled workers, about half said they should be accepted under certain conditions, while about a quarter were against accepting them, and the remaining quarter expressed no clear preferences (see Fig. 6). In the next survey two years later, an additional response category (acceptance with no specific conditions) was introduced. The result shows that public opinion was now even more strongly in favour of a controlled opening of the Japanese labour market to lower-qualified foreign workers. About 70 per cent of the respondents were in favour of such a move. This increase is probably due to the worsening labour shortage and the sharp increase in irregular migrants.

Acceptance of simple workers (tanjun rōdōsha), 1988, 1990, 2000, and 2004. Note: The answer category ‘Acceptance with no specific conditions’ was not included in the first survey of 1988. Regarding the category ‘Acceptance with certain conditions’, in the first three surveys of 1988, 1990, and 2000 the statement ‘Allow simple labourers to work with certain conditions and restrictions’ was used. In the fourth survey of 2004, the wording was modified into ‘Prioritize the use of domestic labour force, including women and the elderly, and accept simple workers in areas where labour is still in short supply’. Source: CAO (1988, 1991, 2001, 2004b).

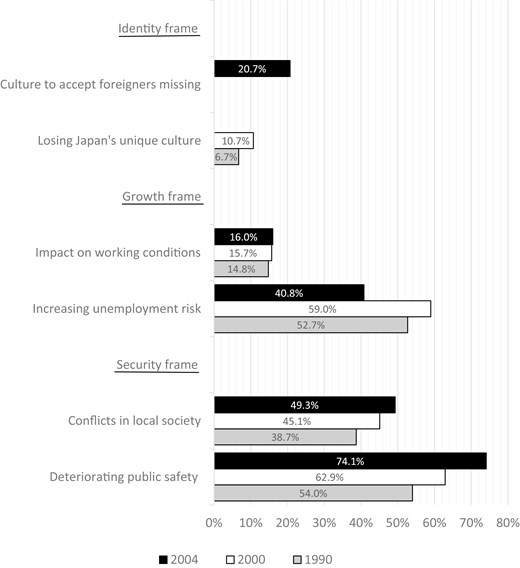

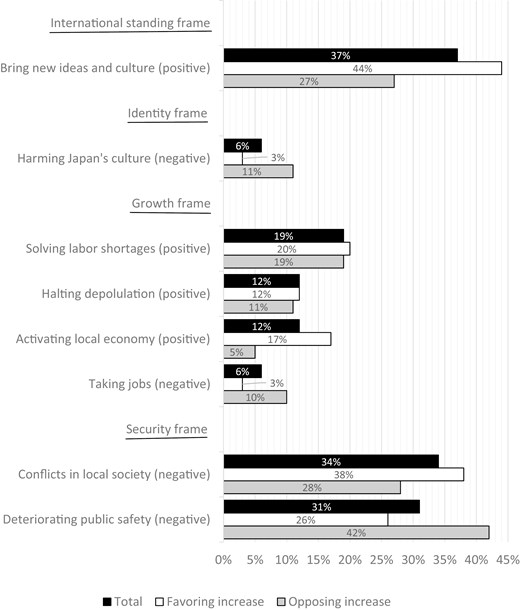

Respondents who were of the opinion that unskilled workers should not be accepted were asked why. They were given a series of possible reasons from which they could choose as many as they wished. The reasons given can be assigned to the identity, growth, and security frame (see Fig. 7). In both surveys of 1988 and 1990, the security and growth frame were strongly on the mind of those opposed to lower-qualified foreign workers. Over half cited the risk of rising unemployment among the Japanese workforce and of deteriorating public security. While potential conflicts between foreign and Japanese residents on the local level were also a significantly shared reason, only a minority of about 15 per cent feared a negative impact on the working conditions of the Japanese workforce. The impact of the identity frame was much weaker for a negative view. Only a small minority of about 7 per cent (1988) and 11 per cent (1990) worried about the impact on Japan’s unique culture.

Reasons for no acceptance of simple workers (multiple answers), 1990, 2000, and 2004. Note: This question was not included in the first survey of 1988. While the answer category ‘Losing Japan’s unique culture’ was included in the surveys of 1990 and 2000, the answer category ‘Culture to accept foreigners missing’ was inserted instead in the 2004 survey. Source: CAO (1991, 2001, 2004b).

In the 1990 survey, those in favour of accepting lower-qualified foreign workers without any specific conditions were also asked about the reasons for their opinion. The growth and international standing frame played equally important roles with about half of the respondents hoping that the inflow of lower-qualified foreign workers would mitigate the labour shortage or be a form of support for foreign workers (see Fig. 8). In comparison to the first immigration debate, the perception of labour immigration had fundamentally changed among the progressive population from exploiting to helping foreign workers. Enhancing Japan’s internationalization and supporting developing countries were additional reasons that were mentioned by a substantial share of the respondents. Overall, the CAO surveys show that the growth, international standing, and security frames were more influential in shaping public opinion. Nevertheless, public statements and decisions, such as the exceptional treatment of the nikkeijin, suggest that the identity frame has received much more attention within the conservative establishment and the LDP than it has among the general population.

The collapse of the investment bubble led to a major downturn in the labour market (see Fig. 4), and the second policy debate ended rather abruptly (see Fig. 3 and Table 1). For some years, immigration and foreign workers were no longer pressing issues on the national political agenda or in public debate.

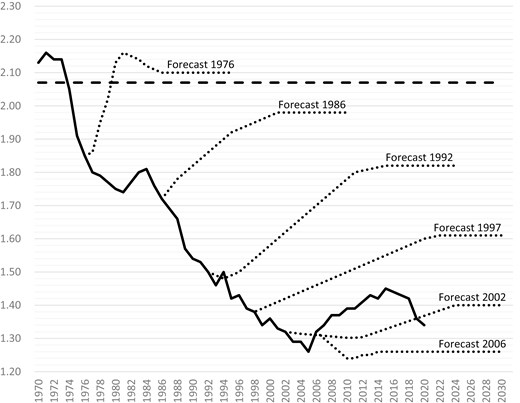

In the late 1990s, the topic of immigration returned, and the third policy debate started. This time, the trigger was not a labour shortage as the debate started at a very low point in labour market demand (see Fig. 4). Instead, the catalyst was a new forecast by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (IPSS) regarding Japan’s future demographic development. Over time, the IPSS downgraded the long-term total fertility rate (TFR) in every forecast because of an increasing gap between the intended reproduction behaviour of the population in the IPSS’s national surveys and actual reproduction behaviour (see Fig. 9). In 1997, the new IPSS forecast predicted that the TFR would remain below 1.6 in the long term, which meant that Japan would eventually struggle to finance its social security systems and run into a severe shortage of workers, especially young workers (Schoppa 2006: 152–153).

Revisions of Japan’s total fertility rate forecasts, 1976–2006. Source: Katagiri et al. (2020: 3).

In contrast to the second debate, this time the debate turned proactive (Hirowatari 2005). In the late 1990s, when the third debate began, immigration was not an urgent current problem that had to be solved. Japan’s population was not yet decreasing and there was no labour shortage, but the labour market was deteriorating. Still in view of the new demographic predictions, policy entrepreneurs like Sakaiya Taichi started a new debate about a more open immigration policy, which they regarded as indispensable for Japan’s future. The third debate was dominated by the growth and security frames and was less complex than the second debate.

In an economic growth perspective, it was argued that due to its demographic transformation, Japan needed many more immigrants, including lower-qualified workers, to maintain its economic size, international weight, and level of wellbeing. Sakanaka (2004), for example, put it bluntly: Japan had to decide if it wanted to remain a big and important global player through immigration or to become a small and irrelevant country without immigration. With the renewed labour shortage in the new millennium (see Fig. 4), the debate gained further momentum, and far-reaching proposals were made by those arguing for a more open immigration policy, for example, for a new middle category of mid-qualified foreign workers to be accepted (HFPC 2006), for the introduction of a guest worker programme (LDP 2008a), or even for the transformation of Japan into a fully-fledged immigration nation (LDP 2008b). The growth frame had now a dominant narrative of needed immigration. While some, notably labour unions (Rengō 2004; IMF-JC 2006) and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) as the successor to MOL (MHLW 2004, 2006), continued to oppose the admission of lower-qualified foreign workers on the grounds that it would lead to a deterioration in the working and living conditions of Japanese workers, the arguments of the proponents became much stronger, describing them as an irreplaceable building block for the future of Japan’s economy and population (Sakanaka and Asakawa 2007). In contrast to the second debate, not only SME’s interest organizations (JCCI 2003) but also Japan’s leading business organizations dominated by its large companies demanded a more open immigration policy (Nikkeiren 2000; Nippon Keidanren 2004, 2007).

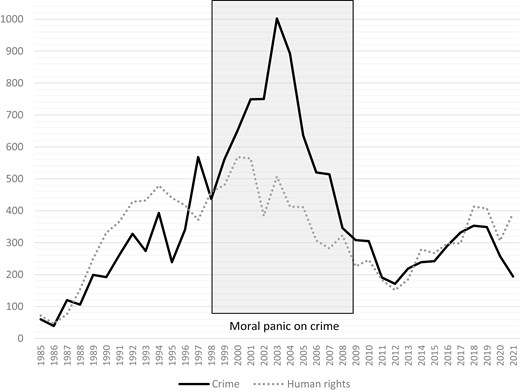

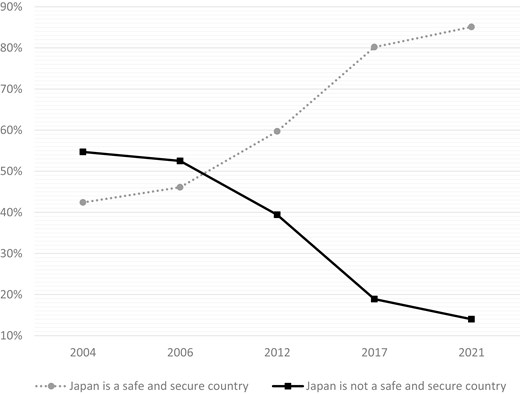

During the same years, however, a ‘moral panic’ (Cohen 1972) on crime developed in Japan. According to the detailed analysis of Hamai and Ellis (2006, 2008; see also Hamai 2004), a series of police scandals in the late 1990s let to media criticism and prompted the police to report crime in their statistics much more comprehensively than in the past. These new methods in crime recording resulted in a huge increase in official crime rates, which was picked up by Japanese mass media who started to publish much more on crime and its increase. As a result, the public perception of public security changed profoundly. While Japan was considered one of the safest societies in the world, the public perception was that a crime wave was sweeping the country. As part of this new general feeling of insecurity, victims’ support groups gained much more public and political attention. Politicians started to denounce the implosion of public security and introduced new legislation to counter the ‘rampant expansion’ of crime. Criminal justice policies took a turn toward punitiveness.

However, in sharp contrast to the public and political discourse, more reliable crime data like the International Crime Victims Survey (ICVS) showed that Japanese victimization rates remain very low in international comparison and reported even falling rates for most crimes.5 As Kawai (2004: 70–71) sums up: ‘The more one studies it, the clearer it becomes that the cause of the large increase in reported robbery is ... changes in the way the police have defined it’ (see also Johnson 2007; Miyazawa 2008). Public sentiments and political debates about crime have become completely out of touch with real development. From the late 1990s to the late 2000s, Japan was a textbook case of a moral panic (on crime), during which ‘reactions of the media, law enforcement, politicians, action groups, and the general public are out of proportion to the real and present danger a given threat poses to the society’ (Goode and Ben-Yehuda 1994: 156).

This moral panic on crime became very influential in immigration policy. In public and political debate, foreign residents, especially irregular foreign workers, were identified as one main culprit for the collapse of public security and increasing crime rates. As described above, the security frame had played a central role in immigration policy from the very early postwar period. At the very beginning of Japan’s new immigration, the NPA had established a link between immigration and increasing criminality, but during the third debate, its language became much stronger. The 1999 police white book denounced for example irregular immigration (NPA 1999: 17):

Among the undocumented immigrants who originally came to Japan for work purposes, many get involved in criminal activities, which are more profitable than illegal work. The large number of undocumented immigrants becomes a hotbed of crime by foreigners.

The security discourse became even more influential and deteriorating public security was the main argument against letting lower-qualified foreign workers into the country. In mass media reporting, foreigners were depicted as threats and potential criminals (Yamamoto 2010, 2013). The decade of moral panic on crime can clearly be identified in the mass media as the number of articles reporting on foreigners’ criminality increased and became much more common than articles discussing foreigners’ human rights (see Fig. 10).

Mass media reporting on foreigner crime and foreigner’s human rights, 1985–2021. Source: Own full-text research using the keywords ‘foreigner’ (gaikokujin) and ‘crime’ (hanzai), as well as ‘foreigner’ (gaikokujin) and ‘human rights’ (jinken), in the electronic databases Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search (Asahi Shinbun), Nikkei Telekom 21 (Nihon Keizai Shinbun), Maisaku (Mainichi Shinbun), and Yomidas Rekishitan (Yomiuri Shinbun).

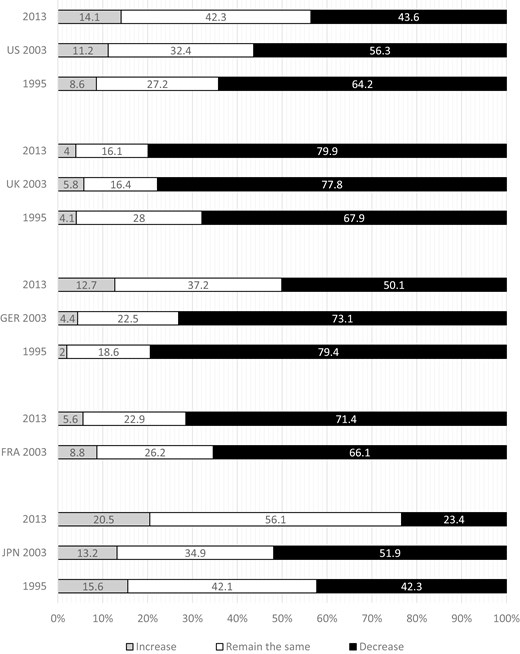

The public perception of foreign workers as potential criminals was documented in several surveys (e.g. CAO 2004a, 2006), and the 2003 ISSP survey showed that it was especially pronounced in Japan compared to other countries (see Fig. 11). This perception also led to a more negative view regarding the inflow of foreign workers, which can be seen when comparing ISSP surveys of 1995 and 2003 and the CAO immigration survey of 2004 with the previous ones (see Figs. 6 and 15). The CAO immigration surveys also show a shift in public perception of the immigration issue (see Figs. 7 and 8). While the security frame and especially the perception of foreigners as a public security risk became much stronger in the 2000 and 2004 surveys, the potentially positive and negative view of immigration as part of the growth frame lost importance in the public perception in the third debate. At the time of the 2000 survey, there were no severe labour shortages, so respondents who favoured an open immigration policy were much less likely to see it as necessary from a labour market perspective (see Fig. 8). In the same survey, unemployment rose sharply, foreign workers were more likely to be perceived as a threat to the domestic workforce among those who did not want to admit low-skilled foreign workers, but by the 2004 survey, when the unemployment peak of those years had passed, the share of respondents who held this view had fallen sharply again (see Fig. 7). In the 2000 survey the share of respondents giving an identity frame reason had moderately increased among those rejecting lower-qualified workers, but they still remained a small minority. The influence of the identity frame is difficult to assess in the 2004 survey, as a completely new statement was used. However, even this much more open statement was only supported by one-fifth of those opposing a more open immigration policy. Nonetheless, the right wing of the LDP had not changed its negative view of opening the Japanese labour market based on an identity frame.

Opinions regarding the statement ‘Foreigners increase crime rates’ in 1995, 2003, and 2013. Source: International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), National Identity Survey 1995, 2003, and 2013.

Overall, the security arguments prevailed. Despite intensive political discussions and far-reaching proposals, the front door was not opened for lower-qualified workers. On the contrary, border controls were increased, and new measures were introduced to reduce the number of irregular foreign residents in accordance with demands made through a security frame. Although ethnic nationalism played a subordinate role in the third immigration debate, it may have indirectly reinforced the perception of non-Japanese people as a security threat. The international standing frame retained a strong role in the second debate among those of the population in favour of an open immigration policy (see Fig. 8), but among policy-makers Japan’s international standing was almost completely absent during the third debate, due in part to the greatly diminished influence of MOFA that did no longer provide the director of the immigration office from 1999 onwards. However, the two minor reforms in immigration policy introduced during the third debate—measures against human trafficking and inclusion of foreign workers in Japan’s Free Trade Agreements/Economic Partnership Agreements (FTAs/EPAs)—were realized due to foreign policy considerations (Akashi 2010: 260–264; Chiavacci 2011: 237–264; Strausz 2019: 77–81).

The economic downturn after the Great Recession (2007–9) led to a fall in demand in the labour market (see Fig. 4), and the immigration issue was ousted from the political and public agendas (see Fig. 3 and Table 1). The extent to which Japan’s immigration policy debates are driven by the issue of lower-qualified foreign workers is discernible by the fact that at the low point of public attention to the immigration issue between the third and fourth debates in 2012, a new points system for highly qualified workers was introduced (Wakisaka 2022). As this reform was not controversial and generally accepted, it was not accompanied by much public or political discussion.

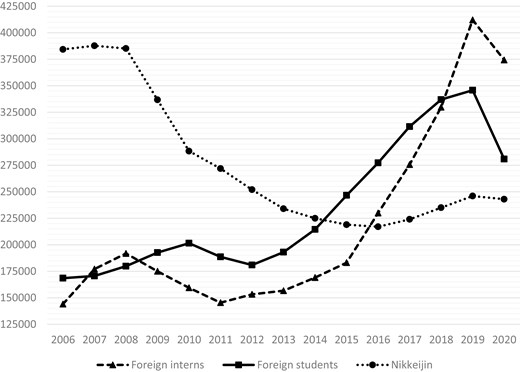

The constant economic growth of the 2010s led to an increase in labour demand and produced a labour shortage that reached a higher level than during the bubble economy (see Fig. 4); however, it was not only economic growth that drove this shortage but also demographic changes. Japan’s total population and its working-age population had begun to decline, and labour losses grew every year. A labour shortage due to demographic changes was no longer a future projection but a current reality. The increase in foreign students and interns and the stagnation of nikkeijin were good indicators of this new structural reality (see Fig. 12).

Trends in foreign trainees, foreign students and nikkeijin, 2006–20. Note: No official statistics are available for the number of nikkeijin. As a proxy indicator, the number of Brazilian and Peruvian residents has been used for nikkeijin. Not all Brazilian and Peruvian residents are nikkejin, but the overwhelming majority are. Moreover, Japan has also a smaller number of nikkeijin residents from other South American countries, which should balance the overall number. The proxy indicator is enough exact to show the trend of nikkeijin. Source: Own calculations based on ISA (2023a).

Although the government expanded the special rule for the nikkeijin to the fourth generation in the summer of 2018, the number of nikkeijin in Japan, which had strongly fallen during the Great Recession of 2007–9, continued to stagnate and never returned to its former levels. One important reason for this stagnation was that nikkeijin were primarily hired as a flexible industrial workforce indirectly through private work agencies, and as Japan’s export industries stagnated due to investment abroad, demand did not expand significantly. Foreign students (in the urban service sector) and foreign interns (in rural areas) are a much less flexible workforce that fills structural labour gaps, and their increase reflects the demographic changes. Forecasts for rural Japan became bleak, and the Masuda Report of 2014 made stark predictions about rural depopulation and extinction (Masuda and NSK 2014). This triggered intense public debates about the demographic situations and prospects of rural Japan.

In view of this new demographic reality, arguments for a more active immigration policy gained new urgency and led to the fourth immigration policy debate (see Fig. 3; Table 1). Business interests vehemently demanded an opening of the Japanese labour market in sectors with a workforce shortage (Nippon Keidanren 2016, 2018; JCCI and TCCI 2017). Nevertheless, the divide in the growth frame did not completely disappear, as the trade unions remained very sceptical about the admission of lower-qualified foreign workers (Rengō 2017: 4):

The easy and planless acceptance of foreign labour has a negative impact on domestic employment and working conditions due to the influx of low-wage workers and is also problematic from the perspective of ensuring the rights of foreign labourers. Therefore, it should not be carried out.

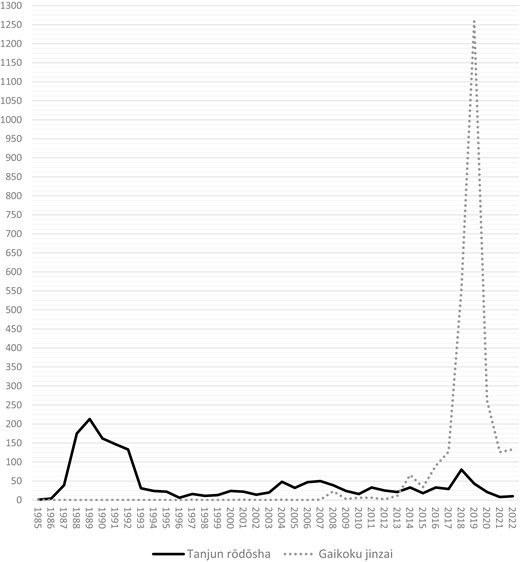

To weaken this divide, LDP forces in favour of accepting lower-qualified foreign workers streamlined the growth frame by creating a new conception of foreign worker admission policy within the LDP and the public (Higuchi 2023). The terminology for lower-qualified foreign workers had to be reconceptualized more positively (Kimura 2022: 13). In 2016, the policy paper of the Special LDP Committee for Securing Workers clearly demanded such a change (LDP 2016: 1): ‘When discussing the acceptance of foreign workers in the future, it is inappropriate to use the term “simple workers”. We should develop our ideas without using this terminology’. The more positive term ‘gaikoku jinzai’ (foreign human resources), which had been completely absent in the first and second debates, was introduced in the late years of the third debate and became dominant in a short time (see Fig. 13). ‘Simple workers’ did not completely disappear,6 but ‘foreign human resources’ was much more frequently used in public debate as well as LDP and governmental publications in the later years of the fourth debate, especially during the 2018 immigration reform itself.

Terms used in public debate for lower-qualified foreign workers, 1985–2022. Source: Own full-text research using the keywords ‘simple worker’ (tanjun rōdōsha) and ‘gaikoku jinzai’ (foreign human resources) in the electronic databases Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search (Asahi Shinbun), Nikkei Telekom 21 (Nihon Keizai Shinbun), Maisaku (Mainichi Shinbun), and Yomidas Rekishitan (Yomiuri Shinbun).

This reframing of admission policy also included a redefinition of ‘immigration’ to weaken the opposition based on an identity frame as elaborated by Kimura Yoshio, one of the leading LDP politicians in favour of opening the Japanese labour market (Kimura 2022: 10):

Within the LDP to which I belong, there are people on the right, liberals, and those in the centre. However, when the term ‘immigrant’ is used, it commonly creates a huge commotion. Especially those on the right side get excited and take off their jackets. I established a special committee for foreign labour in the LDP about twenty years ago. However, as soon as the term ‘immigrant’ was used, people rushed in, and intense debates ensued. Engaging in this debate often deviated from the original purpose, which was honestly ‘securing labour’. (…)

(…) Therefore, we defined in a kind of non-definition ‘“Immigrants” as someone who possess permanent residency at the time of entry. Acceptance based on a residence qualification for employment purposes does not fall under the definition of “immigrants”’ [in May 2016].

This particular definition deviates fundamentally from the standard definition of an immigrant as someone who changes the country of residence for one year or longer, which is generally used by governments, scholars, and international organizations. Obviously, the main aim of the new definition was to eliminate the ‘immigration issue’ from the discussions about foreign workers.

Arguably even more important, the fourth debate was not only marked by reframed and reinvigorated arguments for opening the Japanese labour market to lower-qualified foreign workers but also by a substantial decline in the main counter argument during the third debate. In the late 2000s, the moral panic on crime ended in Japan, and the perception of public security became positive again and continued to improve (see Fig. 14). In parallel, reporting on foreigners became more balanced again (see Fig. 10), and the view of foreigners as criminals and a threat to public security weakened (CAO 2012). In international comparison, one might say that the perception of foreigners as potential lawbreakers normalized (see Fig. 11). Security being seen as less of an issue by the public made substantial immigration reform far less politically costly.

Public perception of security in Japan, 2004–21. Source: CAO (2022: 3).

An expansion of the foreign intern programme as an alternative to opening the front door to lower-qualified foreign workers was not really feasible in the international standing and security frames. National and international criticism of the foreign intern system had continued, especially from the US government in its yearly reports on human trafficking, due to its connection to dept-forced migration and human rights infringements. The number of foreign interns had strongly increased in the late 2010s, but a further enhancement of the foreign intern system would have damaged Japan’s international reputation. Moreover, the programme was plagued by the disappearance of foreign interns who became irregular foreign workers. Expanding the foreign intern programme would have meant risking higher criminality, according to the conservative establishment’s narrative of irregular foreign workers as potential criminals.

As the CAO surveys on foreign worker issues were discontinued, a direct comparison of the relative prominence of the four frames in public perception during the fourth immigration debate with the three earlier debates is not possible. Still, a large survey of the national Japan Broadcasting Corporation (Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai, NHK) in March 2020 provided us with an understanding of public opinion at the end of the debate after the reform. In the survey, both groups of respondents favouring and opposing increasing foreign residents in their residential area were asked about their most important positive expectations and negative concern regarding such an increase (see Fig. 15). Despite the end of the moral panic on crime, the results show that the security frame remained the strongest factor for a negative view of increasing foreign residents. The security frame was far more important than the identity frame or the negative impact on Japanese workers as part of the growth frame. The internationalization of Japan through the inflow of new ideas and culture was an important positive expectation, but the share of respondents identifying foremost a positive impact on one aspect of the growth frame was cumulatively higher. The survey also documents the shifts within the growth frame in public opinion, which coincide with the new emphases in the political debate. Little attention is paid to the risk of a negative impact on Japanese workers. By contrast, foreign workers are now also seen as a structural factor in halting population decline and reactivating the local economy.

Most important positive expectation and negative concern regarding an increase of foreign residents in own residential area (one answer each), 2020. Source: Okada (2020: 81–82).

Despite the new definition of immigration, ethnic nationalism remained relevant inside the LDP, and not all LDP parliamentarians welcomed the proposed introduction of a guest worker programme as they regarded it as the end, or at least the beginning of the end, of a socially and ethnically homogeneous Japan. Still, Abe and his administration had their party under control, and the reform proposal was pushed through internal LDP deliberation with minimal adjustments and tightening. To fully understand this development, we now need to turn to the institutional setting of immigration policy.

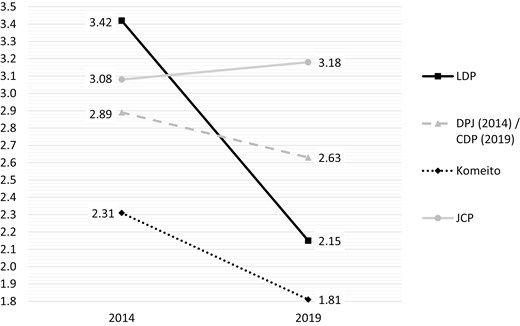

4. Changing institutional setting: from fragmentation to centralization

An analysis of the institutional setting in immigration policy over the last half-century shows discontinuities in the main actors as well as in the decision-making processes and their location in the polity. Just as the frames and their relevance have changed over time, the institutional setting has gone through fundamental transformations that are of crucial importance for understanding the policy field of immigration. In a nutshell, the arena of immigration policy-making in Japan has moved over five decades from the streets and social movements (first debate around 1970) to the administration and inter-ministerial conflicts (second debate around 1990) to the internally divided LDP (main period third debate around 2005) to the core executive and its top-down decision-making (fourth debate in the late 2010s).

During the first small debate around 1970, SME interest groups and some other actors in the conservative establishment were supportive of opening the labour market to foreign workers and tried to prepare the field for expanding the foreign intern system and introducing a guest worker programme. However, many in the conservative establishment remained sceptical of such ideas and had good reasons in view of the strong national and international opposition. The powerful labour unions, the MOL and progressive opposition parties categorically opposed any proposal of an active immigration policy. The social movements of the New Left criticized it even more vehemently as Japan’s abuse of power against its East Asian neighbours and staged disruptive protests. Similar views and allegations were also expressed abroad, particularly in Southeast Asia.

Given the shaky power base at the time, it hardly seemed like a good idea for the conservative establishment to embark on such a political experiment as recruiting foreign workers. As in other policy fields (e.g. environmental policy), the conservative establishment’s room for manoeuvre was limited by strong progressive forces and a forceful extra-parliamentary opposition on the streets. The first immigration debate ended with the economic recession without really gaining momentum, and we can only speculate how things would have developed without the oil price shock. Nevertheless, it is hard to imagine that a comprehensive opening of the Japanese labour market could have prevailed against such strong opposition forces. However, Japan’s postwar protest cycle ended in the mid-1970s (Kajita 1990; Nishikido 2012; Chiavacci and Obinger 2018). Social movements no longer played such a central role in later immigration debates. Labour unions remained a voice in subsequent immigration policy debates, but increasingly lost membership and influence, particularly during the third and fourth debates.

In the second debate, the locus of immigration policy moved from the street to the state apparatus. Institutionally, this second debate that took place around 1990 was marked by ‘bureaucratic sectionalism’ (Imamura 2006), and the irrelevance and even absence of many important players in the conservative establishment. In fact, the LDP, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), and Keidanren, allegedly the three most powerful actors of the conservative establishment (Stockwin 2003), played no leading roles in the second debate. The LDP had several working groups on the immigration issue at the time, but they only produced very general statements, like the importance of building a national consensus without a clear positioning of the party regarding the acceptance of lower-qualified foreign workers. For example, an internal strategy committee summarized as follows the basic LDP policy (quoted after Yomiuri Shinbun 1988): ‘Foreigners with specialized skills and abilities should be accepted as much as possible, but the pros and cons and problems of accepting simple workers should be fully and carefully considered’. Obviously, the LDP was unable to overcome the internal differences between its pro-acceptance SME wing and its anti-acceptance ethnonationalist wing. Moreover, the LDP was in disarray during this period, marked by political scandals and internal reform debates.

Keidanren, the most influential business association representing mainly large companies, was only conspicuous by its absence from the debate. It hardly spoke out on immigration issues, and if so, only very cautiously and with a wait-and-see attitude: ‘Simple workers should be carefully considered’ (Nihon Keizai Shinbun 1989). At the very end of the second debate in May 1992, it finally published a position paper on this crucial economic question that, however, did not present any strong demands (Keidanren 1992). Similar to the LDP, this was a sign of a fundamental internal disagreement regarding immigration in Japan’s most important business interest group. Meanwhile, the MITI, supposedly the most powerful ministry in economic matters (Johnson 1982), was also at best a supplementary player that exerted no significant influence on the immigration policy-making process.