-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kate Williams, What counts: Making sense of metrics of research value, Science and Public Policy, Volume 49, Issue 3, June 2022, Pages 518–531, https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scac004

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

There is no singular way of measuring the value of research. There are multiple criteria of evaluation given by different fields, including academia but also others, such as policy, media, and application. One measure of value within the academy is citations, while indications of wider value are now offered by altmetrics. This study investigates research value using a novel design focusing on the World Bank, which illuminates the complex relationship between valuations given by metrics and by peer review. Three theoretical categories, representing the most extreme examples of value, were identified: ‘exceptionals’, highest in both citations and altmetrics; ‘scholars’, highest in citations and lowest in altmetrics; and ‘influencers’, highest in altmetrics and lowest in citations. Qualitative analysis of 18 interviews using abstracts from each category revealed key differences in ascribed characteristics and judgements. This article provides a novel conception of research value across fields.

1. Introduction

There have been many academic and applied attempts to capture the value of research. This endeavour is complicated by variation in the criteria used to determine value, as well as differences in the practices through which it is attributed. The concept of value refers to what counts, what is worthy and of true relevance (Boltanski and Thévenot 2006; Stark 2016). Producing research that is deemed worthwhile is important for research organisations to attain the legitimacy and the resources necessary for existence and growth. Yet, there are always multiple principles of evaluation (Stark 2016). Specific criteria vary in strength and importance across disciplinary, organisational, and national contexts. These include clarity, quality, originality, significance, methodological sophistication (Lamont 2010), and increasingly, broader impact on society (Smith et al. 2020; Williams 2020a). Furthermore, each criterion can be operationalised through different practices of valuation (Fochler et al. 2016), such as the practice of quantifying performance (i.e. metrics) and the practice of peer review (i.e. narrative judgements). These issues are particularly salient as researchers are increasingly expected to meet the needs of a range of audiences from different fields beyond academia, such as policymakers, practitioners, or the public. Thus, increasingly, there are multiple ‘value regimes’, which flow from foundational decisions about what to count and make visible (Bigger and Robertson 2017). Two key value regimes relate to academic influence, on the one hand, and wider influence, on the other. These have been operationalised through citations (i.e. a measure of use in published academic outputs) and alternative metrics or ‘altmetrics’ (i.e. measures of use in online environments such as social media, blogs, and news), respectively. This study investigates the complex relationship between metrics and peer review around academic and wider influence. It seeks to answer the question: how can the narrative judgements of expert peers be used to make sense of categories of value given by citations and altmetrics?

Within the literature on science and expertise, value tends to take the form of ‘research influence’ (i.e. use, engagement, or impact). This is typically conceptualised as being within the academic system or external to it (Bastow et al. 2015) or, alternatively, as science-centric or user-oriented (McNie et al. 2016). Within the academic system, influence has primarily been determined through bibliometrics (i.e. publication counts, citation counts, Journal Impact Factor, and h-index). These metrics involve factors including the number of publications and citations, often accompanied by other quantitative measures (Wouters et al. 2015). For example, a researcher might look to their h-index as an indicator of their contribution to their discipline. Although not perfect, bibliometrics is widely accepted as a reasonable proxy of value within the science system (Petersohn and Heinze 2018). Yet, the widespread focus on bibliometrics has been subject to criticism, and the research profession has come to include new expectations, roles, and responsibilities oriented outside the academic system (Bastow et al. 2015). Many different types of research organisations seek to provide knowledge that speaks to a range of non-academic audiences, and even within scholarly institutions, researchers are increasingly encouraged to be more connected to wider communities and their needs. As such, many research organisations are now compelled or incentivised to understand, capture, and report on their influence beyond the academy (D’Este et al. 2018).

External influence has been studied using a range of techniques and methods, such as economic or statistical measures of income or intellectual property, or through impact case studies and testimonials (Reed et al. 2020; Rousseau et al. 2021). As research processes, discussions, and outputs increasingly occur online (Feldman et al. 2015; Veletsianos 2016), there has been an explosion of attention on ‘altmetrics’ or ‘non-traditional scholarly impact measures that are based on activity in web-based environments’ (Priem et al. 2012). These include: ‘mentions’ in policy documents, blogs, news, and Wikipedia; ‘shares’ on social media (e.g. Twitter, Facebook); and ‘bookmarks’ on online networks (e.g. Mendeley, ResearchGate). Although lacking clear meaning or credibility, there has been a great deal of interest in gathering evidence from these sources to complement citation data and established indicators of external influence. Despite the availability of these metrics, there is a strong ‘need to define the meaning of the various indicators grouped under the term ‘altmetrics’ (Haustein et al. 2016: 374). ‘Theoretical attention is required that can be used to understand value in relation to the multiple audiences that research is increasingly expected to serve.

Examining the multiple value regimes that exist in research is important because researchers must increasingly produce work within a hybrid space. As the practice of research shifts to include a wide array of policies, priorities, and expectations, researchers increasingly need to satisfy various actors and structures beyond traditional academic sites, including policymakers, practitioners, mediators, and industry (Bozeman and Youtie 2017; Sengupta and Ray 2017). To be seen as worthwhile, often the outputs of an organisation must satisfy the expectations of specific social worlds while remaining flexible enough to inhabit multiple intersecting communities (Star and Griesemer 1989). The ideas, outputs, and practices from inside and outside academia are often innovatively recombined, to the extent that the boundaries between them become weaker (Rao et al. 2005). This article seeks to examine value regimes around academic and wider influence. It draws on a case study of the World Bank, which is the primary source of intellectual authority and influence in the area of development economics (Donovan 2018). As a highly influential and well-resourced hybrid research organisation, the World Bank seeks many sources of legitimacy and actively engages multiple audiences across different fields.

This article reports the results of a novel qualitative design to explore commonalities and differences between valuations of research outputs. Rao et al. (2005) observe that defining categories in opposition to each other creates strong boundaries between them and thus provides extreme cases that make possible detailed investigation. Thus, this study uses extreme cases from two different value regimes (operationalised by citations and altmetrics) to provide strongly defined differences that allow for a qualitative investigation of the valuations that are ascribed to them. A dataset was created of World Bank outputs published in 2015 that had associated citation and altmetric data (n = 195). Three extreme-case categories were identified: ‘exceptionals’—outputs with highest scores in both citation count and altmetric attention score; ‘scholars’—top in citations and lowest in altmetrics; and ‘influencers’—top in altmetrics and lowest in citations.1 18 economists from the World Bank’s research unit representing all levels of seniority were interviewed using a novel qualitative design. Each interviewee was provided with three abstracts from each of the three categories (without author information or category grouping). Respondents were asked to narrate the value of the publications by drawing distinctions between outputs of high value and low value (Lamont 2010).

This article presents an innovative analysis, using two potential signifiers of value—citations and altmetric attention score—to determine the meanings that are tied to different value regimes. It examines whether common metrics used to give insights into value within the academic system and outside of it correspond to the value that is given by experts. The analysis revealed key differences in ascribed characteristics and judgments. Peer evaluators perceived outputs in the ‘exceptional’ category as able to balance the preferences of academic and wider audiences, thus potentially offering something of value to both. The article commences with a review of the literature on measuring and theorising research value. It then sets out the case selection and method that was employed in this study. Finally, the article presents the results and contextualises them through a discussion of the broader implications, as well as limitations of the study design. The article offers a new way of conceiving research value that takes into account potential differences in forms of valuation as practice.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1 Measuring research value

Research institutions, including university departments, think-tanks, and government research agencies, use a range of tools to measure the value of the research they produce. For example, expert peer review can be used to assess quality, narrative case studies can indicate effects on policy, and metrics can give insights into engagement. Metrics, in particular, have captured the market of ‘value’ (Espeland and Sauder 2016; Strathern 2000), with bibliometrics traditionally dominating. Foremost among these are citations, which are based on the idea that the advancement of knowledge relies on the acknowledgement of prior work (Garfield 1979). Citations have come to be synonymous with academic value and each of the most widespread bibliometric indicators rely on them as their base.2 As a whole, bibliometrics have a strong theoretical background but are influenced by the database they are derived from (López-Cózar et al. 2014), are open to manipulation such as self-citation (Seeber et al. 2019) and cannot easily be compared across disciplines because of different citation patterns in scholarly communities (Rafols et al. 2012; Link 2015). Crucially for researchers oriented to multiple audiences, bibliometrics are not able to provide insight into wider engagement with or influence on society, for example advising government policy or informing the public.

Since the term was coined in 2010, altmetrics have grown rapidly as a way of attempting to measure engagement or influence beyond the academic system. There are now several commercial providers, which offer accessible platforms that compile data from multiple sources (e.g. Twitter, Facebook, Mendeley). These platforms have been taken up by research institutions (e.g. Liu et al. 2016) to understand how their outputs are viewed, saved, discussed, or recommended by diverse audiences or in ways excluded by traditional bibliometrics. Although initially proposed as alternatives to citations, the empirical evidence suggests that they are better thought of as complements (Costas et al. 2015). Authors have suggested ‘influmetrics’ (Cronin 2005) or ‘social media metrics’ (Haustein et al. 2014) as more accurate names to emphasise the potential opportunities for measurement and evaluation given by new platforms and the contemporary online milieu. Early literature articulated a hope that altmetrics could overcome some problems of other metrics, which were seen as slow and deficient for capturing wider influence (Bornmann and Marx 2014; Thelwall et al. 2013). Yet, in practice, this expectation has not been realised. Although argued to be transparent and timely (Galligan and Dyas-Correia 2013; Piwowar 2013), altmetrics are fleeting and unstable, can easily be ‘gamed’, are strongly influenced by their commercial provider, and rely on the ‘wisdom of crowds’ (Area and Pessoa 2012). In addition, there are key differences in online activity across research areas (e.g. disciplinary differences on social media; Haustein et al. 2014b) and inequalities in social media capital of individuals, institutions, and journals that undermine their validity and reliability (Regan and Henchion 2019). Most fundamentally, however, there is often a meaning gap between what can and should be measured. This is particularly important because metrics provide an arbitrary form of precision (Espeland and Sauder 2016). They do not simply reflect an underlying social hierarchy but rather play an essential role in creating it by changing how research actors perceive and react to academic outputs and measurements.

In addition to the relative advantages and disadvantages of each, the literature on the interplay of bibliometrics and altmetrics has largely centred on the issue of correlation. Social media metrics correlate only moderately with citation counts (Costas et al. 2015). There is agreement that, with the exception of Mendeley (Zahedi et al. 2017) and tweets by researchers (Haustein et al. 2014), citation and altmetric data can be considered to measure different elements of use, engagement, or influence. Karanatsiou et al. (2017) assert that bibliometrics and altmetrics are both weak indicators fraught with disadvantages, and argue that the combination of the two is the best way to ensure safer conclusions. Costas et al. (2021) propose the concept of ‘heterogeneous couplings’ as a common framework to study the interactions between academic and non-academic actors as captured via online and social media platforms. This provides a basis for considering citations and altmetrics as two different environments of interactions. Such an approach allows the two metrics to be usefully applied to understanding research that is not anchored solely within one social world. The challenge for this article is to make sense of how research outputs that fall into theoretically derived categories representing these different environments of interaction are read differently by expert peers.

2.2 Theorising research value

To demonstrate the worth of their outputs, researchers are more and more attuned to multiple criteria of evaluation. For research organisations outside traditional academic structures, researchers often must engage expertise, ideas, and skills from policy, media, or applied spaces (Hochmüller and Müller 2014), without completely losing credibility from the academic world. For academics, credibility in the scholarly world is paramount, but increasingly, total disengagement from wider fields is discouraged. Indeed, although prestige in traditional research sites has historically followed bibliometric measures, some degree of status is now conferred by measures of societal impact (Williams and Grant 2018). Thus, researchers in many contexts are encouraged or expected to influence multiple fields, defined as sites of struggle where actors have shared conceptions, embodied habits, and tacit knowledge (Bourdieu 1990). To influence multiple fields, hybridity is the key. Researchers must be competent in scholarly expression, shaping policy, facilitating the translation of ideas into practice, broadcasting a message widely, and gaining essential resources to continue their work (Williams 2020b). These requirements arise from different fields, each with a specific language and logic, which must be negotiated to demonstrate worth and gain legitimacy. For example, a researcher who produces an academic article can combine this strategy with wide online dissemination as well as policymaker engagement. In doing so, they can gain academic credibility, social media visibility, and policy authority. It is the variations in potential combinations of these strategies, logics, and resources from different fields that become essential in demonstrating influence.

Influence in research involves the balancing of symbolic resources, and requires competence within the academy and outside of it. The weightings and mixes of different types of symbolic resources vary by organisation and research context. Within academia, although researchers are still primarily judged by their academic outputs, the ‘impact agenda’ (Lauronen 2020; Smith et al. 2020) increasingly incentivises and rewards demonstrably impactful research. For other research organisations, the goals of knowledge production are more varied, and evaluation of research occurs along multiple lines (e.g. considering a wider array of outputs, such as research notes, policy papers, news articles, as well as measures, such as download or view counts). Those who can effectively combine various symbolic resources from the fields of relevance to their context can convert this cumulative power into research funds, promotions, and other opportunities. In addition, the growing focus on wide online dissemination and the use of digital metrics potentially make new avenues of legitimacy available. For example, researchers can highlight widely shared policy reports on curriculum vitae or in a performance evaluation. Similarly, funders, publishers, and research institutions now often report usage metrics (e.g. number of downloads or views) of external reports, policy documents, and other materials. The factors that can provide legitimacy, therefore, continue to progress. This article builds on the theoretical foundations of multiple logics and symbolic resources for hybrid organisations that operate between fields (Williams 2020a). Focusing on a high-profile, hybrid research producer, the World Bank, the article considers these multiple criteria and operationalises them using citations and altmetrics, which are then given narrative conceptualisations of value by expert peers.

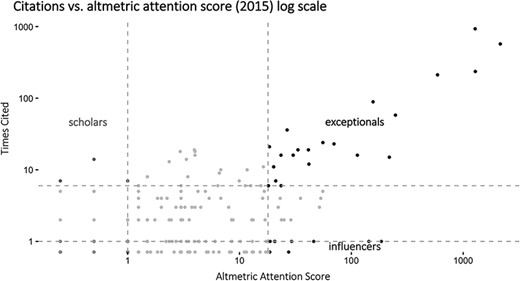

The article explores citations and altmetrics as potential signifiers of value that can be used together to understand patterns of worth in research. In this view, citations represent a measure of credibility from the scholarly field (i.e. academic influence) and altmetrics represent a collective measure of authority, utility, or visibility (i.e. wider influence) from a range of external fields, such as policy, application, or media. Figure 1 shows potential patterns of worth by grouping different clusters of the most extreme possible combined scores on bibliometric and altmetric scales. The exceptional category refers to outputs that combine strong academic and wider performance. The scholar category contains those with high academic influence, but with low external influence. The influencer category includes those that have high wider influence, but relatively low academic influence.3 This article will use this framework to provide a new way of conceptualising research value.

Using citation count and altmetric attention score to chart extreme-case categories of influence.

3. Methodology

3.1 Case selection

Case selection of the World Bank was based on its dominance in global development research amongst multiple audiences including academics, practitioners, political players, economic actors, and the public. Research produced by the World Bank comes from operational departments as well as the principal in-house research unit (DECRG), which undertakes analysis across countries and sectors. The logic of academia is held in tension with operational requirements and processes, resulting in potentially conflicting priorities (Williams 2020b). The Bank is an ideal site of study given its prominence as one of the largest development research institutions, which ensures outputs represent diverse subject matter and research activity. The disciplinary language and concepts of economics, and academia more broadly, dominate institutional materials, but Bank research also self-positions as firmly policy-oriented, often stressing its applied nature. In addition, the World Bank also features a dedicated communications office, which plays an important role in the dissemination of the Bank’s research beyond the boundaries of academia. Crucially, the evaluation of research at the World Bank reflects its hybrid knowledge production. The evaluation criteria include research outputs (academic outputs and flagship reports), research wholesaling activities (datasets, software, training courses, etc.), outreach/dissemination (academic and broader activities plus download counts), citations, and consulting to other parts of the organisation (weeks; author, forthcoming).

3.2 Data sources

The Web of Science Core Collection was chosen as the data source for citations (Birkle et al. 2020). It is a selective citation index of scientific and scholarly publishing covering journals, proceedings, books, and data compilations. Although the use of citations to indicate research influence is widespread, the limitations are that citations are typically treated equally, despite a range of different rationales and functions for citing (Zhang et al. 2013), which clouds the specific contribution of a given work to the citing work (Anderson 2006). In addition, many outputs receive no citation, which suggests that bibliometrics may not be adequate in assessing the value, or importance, of what the Bank produces. For example, it is possible that publications do not make a mark on the academic system, but do influence practitioners, policymakers, and/or broader development debate.

Altmetric.com was chosen as the data source for altmetric data. It uses unique identifiers to match research to mentions in a range of sources (including blogs, citation data, Twitter, Facebook, news and mainstream media, Mendeley, patents, policy documents, and Reddit). Indeed, at the time of the study Altmetric.com was a key tool used by the World Bank in understanding ‘the broader development impact generated as a result of [its] knowledge outputs’. (Alexander 2015). The aggregate altmetric attention score is a compound indicator that weights the different measures captured by Altmetric.com and sums them together in a single metric. The score seeks to provide a weighted count of all of the attention a research output has received, derived from three main factors: volume (the score rises as more people mention it, but only one mention per person per source is counted); sources (some sources are worth more than others, such as a blog post as opposed to a tweet); and authors (mentions from some authors are worth more than others, such as a doctor tweeting as opposed to a journal automatically pushing a link). Thus, the altmetric attention score intends to reflect both the quantity and quality of attention received by each item by applying some control to avoid gaming.4 Altmetric.com was chosen because of its relative robustness and stability and the ease and transparency of connections with the Web of Science. However, such compound indicators have been often criticised for being unreliable and arbitrary (Gumpenberger et al. 2016; Mukherjee et al. 2018), particularly given a lack of transparency in how the weighting works.5 A key problem is that the most important measure in the calculation of the altmetric attention score is the total number of tweeters that have mentioned the publication in tweets. The other sources (such as news and blogs) have a much lower incidence and each tends to correlate with the number of tweets. Another key limitation is that Altmetric.com is likely to underestimate the actual online visibility of outputs produced by the World Bank, given that social science research does not tend to use DOIs as a standard document ID to the same extent as other disciplines (Haustein et al. 2015).

Thus, the altmetric attention score offers an imperfect indicator that a publication has been engaged with, received attention from, or had some influence on audiences, or has in some way been useful, popular or visible. Given the World Bank’s priorities as a specialised research department with a distinctly practice- and policy-focused mode of production, the altmetric attention score can be taken to provide a signifier of external value (utility, visibility, and authority), and thus an interesting addition to academic value as given by citations (credibility). This design allows for an examination of the relationship between prevalent practices of evaluation: counting citations and metrics of wider influence, on the one hand, and narrative valuations given by expert peers, on the other.

3.3 Qualitative sample

The study involved selecting publications to facilitate discussion with researchers from the World Bank’s principal research unit, DECRG, during interviews. Bibliometric data on research outputs with at least one author from the World Bank were taken from the Web of Science and were merged with data from Altmetric.com using DOIs. Each data observation is thus a research output with citation and altmetric data. The sample was restricted to 2015, allowing 2 years for citations to have accumulated before the interviews in 2017 without letting outputs become outdated. This minimised the effect of time-since-publication on the distribution, while still allowing enough time to identify those publications that were cited early and often. 195 articles were identified, with a total altmetric attention score of 7969 and a total citation count of 2785. The study characteristics are shown in Table 1. The sample displays a lower average citation count and higher average altmetric attention score than would be seen in a broader sample (e.g. all outputs from 2011–2015), which is to be expected given there were only 2 years for citations to accrue and due to the growing engagement with online communication.

| Sample (n = 195) . | |

|---|---|

| Citations | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.3 (81.1) |

| Min–max | 0–931 |

| Altmetric attention score | |

| Mean (SD) | 40.9 (205.0) |

| Min–max | 0.2–2146.1 |

| External funding | |

| Funded | 100 (51.3%) |

| International author | |

| USA authors only | 70 (35.9%) |

| Subject group | |

| Business & economics | 89 (45.6%) |

| Environmental science | 14 (7.2%) |

| Health | 41 (21.0%) |

| Social sciences | 20 (10.3%) |

| Other | 31 (15.9%) |

| Publication type | |

| Article | 167 (85.6%) |

| Review | 11 (5.6%) |

| Conference | 1 (0.5%) |

| Editorial | 15 (7.7%) |

| Other | 1 (0.5%) |

| Sample (n = 195) . | |

|---|---|

| Citations | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.3 (81.1) |

| Min–max | 0–931 |

| Altmetric attention score | |

| Mean (SD) | 40.9 (205.0) |

| Min–max | 0.2–2146.1 |

| External funding | |

| Funded | 100 (51.3%) |

| International author | |

| USA authors only | 70 (35.9%) |

| Subject group | |

| Business & economics | 89 (45.6%) |

| Environmental science | 14 (7.2%) |

| Health | 41 (21.0%) |

| Social sciences | 20 (10.3%) |

| Other | 31 (15.9%) |

| Publication type | |

| Article | 167 (85.6%) |

| Review | 11 (5.6%) |

| Conference | 1 (0.5%) |

| Editorial | 15 (7.7%) |

| Other | 1 (0.5%) |

| Sample (n = 195) . | |

|---|---|

| Citations | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.3 (81.1) |

| Min–max | 0–931 |

| Altmetric attention score | |

| Mean (SD) | 40.9 (205.0) |

| Min–max | 0.2–2146.1 |

| External funding | |

| Funded | 100 (51.3%) |

| International author | |

| USA authors only | 70 (35.9%) |

| Subject group | |

| Business & economics | 89 (45.6%) |

| Environmental science | 14 (7.2%) |

| Health | 41 (21.0%) |

| Social sciences | 20 (10.3%) |

| Other | 31 (15.9%) |

| Publication type | |

| Article | 167 (85.6%) |

| Review | 11 (5.6%) |

| Conference | 1 (0.5%) |

| Editorial | 15 (7.7%) |

| Other | 1 (0.5%) |

| Sample (n = 195) . | |

|---|---|

| Citations | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.3 (81.1) |

| Min–max | 0–931 |

| Altmetric attention score | |

| Mean (SD) | 40.9 (205.0) |

| Min–max | 0.2–2146.1 |

| External funding | |

| Funded | 100 (51.3%) |

| International author | |

| USA authors only | 70 (35.9%) |

| Subject group | |

| Business & economics | 89 (45.6%) |

| Environmental science | 14 (7.2%) |

| Health | 41 (21.0%) |

| Social sciences | 20 (10.3%) |

| Other | 31 (15.9%) |

| Publication type | |

| Article | 167 (85.6%) |

| Review | 11 (5.6%) |

| Conference | 1 (0.5%) |

| Editorial | 15 (7.7%) |

| Other | 1 (0.5%) |

There was a strong positive correlation between altmetric attention score and citation count r (193) = 0.86, P < 0.001. Thus, it appears that outputs that receive a higher number of citations tend to also receive higher levels of wider engagement. There is, therefore, a meaningful relationship between the two metrics. Importantly, this wider engagement overwhelmingly takes the form of twitter mentions, as indicated by the very strong positive correlation between altmetric attention score and number of tweeters r (159) = 0.98, P < 0.001. Thus, the altmetric attention score largely reflects engagement on Twitter. A key challenge is that the meaning of Twitter mentions are among the most difficult to interpret at a large scale (see Haustein et al. 2016 for a discussion). Thus, the relative lack of insight that is provided by correlation studies suggests a need to go beyond this type of analysis towards a more nuanced understanding of worth. The study therefore examines the correspondence between patterns of value given by quantified metrics and those given by peer valuations.

3.4 Method

The study identified the research outputs that are valued by the academic community (operationalised by high citation count) and valued by wider audiences or in wider contexts (operationalised by high altmetric attention score). This was achieved by finding the most extreme outputs in terms of citation and altmetric attention scores. To do this, categories were created by finding the values for 20 per cent and 80 per cent of scores. For the citation scores, this intercepted at 0 and 6, respectively, and for altmetric attention score this intercepted at 1 and 18, respectively. Here, the lower bound for citation scores was adjusted to 1, and the categories were made more inclusive by using ‘equal or less than’ or ‘equal or greater than’ (i.e. boundary outputs were included in the exceptional categories) to allow for at least three publications in each category. Using Fig. 1 as a guide, nine categories of value were created from which three categories of theoretical interest were selected. The three extreme-case categories are: exceptionals (top 20 per cent in citations and altmetric attention scores), influencer (lowest 20 per cent in citations and top 20 per cent in altmetric attention scores), and scholars (top 20 per cent in citations and lowest 20 per cent in altmetric attention scores). Thus, for outputs published in 2015, the exceptional category contained publications with citation scores above 6 and altmetric attention scores above 18. The influencer category contained publications with altmetric attention scores equal or above 18 and citation scores of equal or below 1. The scholar category included publications with altmetric attention scores equal or below 1 and citation scores of equal or above 6. It is important to note that the dataset does not include publications with a value of zero for altmetric attention scores, and thus the ‘scholars’ condition would likely include additional highly cited publications that were ignored by Altmetric.com. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of the data into the three categories. Table 2 gives the characteristics of each category.

Log scales of citations vs altmetrics showing categories for 2015.

| . | Exceptionals (N = 21) . | Influencers (N = 9) . | Scholars (N = 3) . | Total (N = 195) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citations | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 111.7 (229.0) | 0.8 (0.4) | 9.3 (4.0) | 14.3 (81.1) |

| Min—max | 6.0–931.0 | 0.0–1.0 | 7.0–14.0 | 0.0–931.0 |

| Altmetric attention score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 307.5 (566.4) | 56.7 (62.6) | 0.6 (0.4) | 40.9 (205.0) |

| Min—max | 18.1–2146.1 | 18.6–185.5 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.2–2146.1 |

| . | Exceptionals (N = 21) . | Influencers (N = 9) . | Scholars (N = 3) . | Total (N = 195) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citations | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 111.7 (229.0) | 0.8 (0.4) | 9.3 (4.0) | 14.3 (81.1) |

| Min—max | 6.0–931.0 | 0.0–1.0 | 7.0–14.0 | 0.0–931.0 |

| Altmetric attention score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 307.5 (566.4) | 56.7 (62.6) | 0.6 (0.4) | 40.9 (205.0) |

| Min—max | 18.1–2146.1 | 18.6–185.5 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.2–2146.1 |

| . | Exceptionals (N = 21) . | Influencers (N = 9) . | Scholars (N = 3) . | Total (N = 195) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citations | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 111.7 (229.0) | 0.8 (0.4) | 9.3 (4.0) | 14.3 (81.1) |

| Min—max | 6.0–931.0 | 0.0–1.0 | 7.0–14.0 | 0.0–931.0 |

| Altmetric attention score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 307.5 (566.4) | 56.7 (62.6) | 0.6 (0.4) | 40.9 (205.0) |

| Min—max | 18.1–2146.1 | 18.6–185.5 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.2–2146.1 |

| . | Exceptionals (N = 21) . | Influencers (N = 9) . | Scholars (N = 3) . | Total (N = 195) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citations | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 111.7 (229.0) | 0.8 (0.4) | 9.3 (4.0) | 14.3 (81.1) |

| Min—max | 6.0–931.0 | 0.0–1.0 | 7.0–14.0 | 0.0–931.0 |

| Altmetric attention score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 307.5 (566.4) | 56.7 (62.6) | 0.6 (0.4) | 40.9 (205.0) |

| Min—max | 18.1–2146.1 | 18.6–185.5 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.2–2146.1 |

A total of nine publications from the exceptional, influencer, and scholar categories, three per category, were selected as stimuli for interviews. Outputs that scored both very low on citations and very low on altmetrics, as well as non-extreme-case categories, were omitted given the time constraints of interviews and given that exceptionals, influencers, and scholars represent high-performing and thus more theoretically interesting outputs. Abstracts were used as stimuli because they are typically the first section of the output viewed by readers. Eighteen interviews with development economists from DECRG were conducted, including department head, lead researcher and researcher levels. Thus, participants were expert peers, who are routinely involved in reviewing, selecting, and citing the types of publications that were presented. Interviews typically took between 15–30 minutes.

The study utilised an innovative open ended and inductive method. Each participant was given a page of three abstracts from one of the three categories as a stimulus and asked to describe the worth of the outputs. Inspired by Lamont (2010), interviewers were guided towards distinguishing what they considered high and low value outputs. The interviewees were aware that they were evaluating their colleagues’ work and were encouraged to talk through their impressions even if they found little value in a particular output. This allowed the criteria underpinning valuations to be identified. This process was repeated for each category. The abstracts were presented without details of their category or any bibliometric information; the documents only included title and abstract. Although presented without author information, some of the outputs were familiar to the interviewees given the collaborative nature of the research group. Appendix A gives the abstract sets that were used. In order to be able to identify the set of abstracts being discussed on the audio recordings, each set was given a neutral signifier (i.e. ‘tulip’, ‘rose’, and ‘orchid’). The data was analysed using directed content analysis (Mayring 2004). It allows for a description of interactions and texts as narrative in form, and allows for changing, fragmented and contextual explanations of phenomena. An initial set of expectations was developed for each category based on preliminary quantitative analysis of the data. Atlas.ti was used to review all transcripts and assign the appropriate part of the interview to the correct category. Then, all text that appeared to discuss the value or meaning of publications was coded, with reference to the initial expectations. For each category, the raw transcripts were cut into relevant fragments. These fragments were given conceptual labels, referring to the underlying value concepts. The process involved two elements: how researchers described the abstracts in each category, and the value judgements they ascribed. After coding, common valuations within categories and differences in valuations between categories were examined.

4. Results and discussion

The aim of the study was to determine how the extreme-case categories derived from metrics of academic and wider value were valued by expert peers. Coding the narrative descriptions of value given by members of the World Bank research department provides insight into the commonalities within each category and the differences between them. Identifying the shared and opposing descriptions and valuations given by researchers helps to make sense of the metrics and provides insights to different practices of valuation. Table 3 summarises the descriptions and judgements that were given to each category.

| Group . | Characteristics . | Judgments . |

|---|---|---|

| Exceptionals | Technical | Relevant |

| Jargonistic | Relatable | |

| Big picture | Easy to read | |

| Large-scale | Topical | |

| Pragmatic | Informative | |

| Descriptive | ||

| Influencers | Non-technical | Relevant |

| Big picture | Relatable | |

| Large-scale | Appealing | |

| Pragmatic | Emotional | |

| Controversial | ||

| Shareable | ||

| Scholars | Technical | Relevant |

| Jargonistic | Difficult to read | |

| Specific | Unappealing |

| Group . | Characteristics . | Judgments . |

|---|---|---|

| Exceptionals | Technical | Relevant |

| Jargonistic | Relatable | |

| Big picture | Easy to read | |

| Large-scale | Topical | |

| Pragmatic | Informative | |

| Descriptive | ||

| Influencers | Non-technical | Relevant |

| Big picture | Relatable | |

| Large-scale | Appealing | |

| Pragmatic | Emotional | |

| Controversial | ||

| Shareable | ||

| Scholars | Technical | Relevant |

| Jargonistic | Difficult to read | |

| Specific | Unappealing |

| Group . | Characteristics . | Judgments . |

|---|---|---|

| Exceptionals | Technical | Relevant |

| Jargonistic | Relatable | |

| Big picture | Easy to read | |

| Large-scale | Topical | |

| Pragmatic | Informative | |

| Descriptive | ||

| Influencers | Non-technical | Relevant |

| Big picture | Relatable | |

| Large-scale | Appealing | |

| Pragmatic | Emotional | |

| Controversial | ||

| Shareable | ||

| Scholars | Technical | Relevant |

| Jargonistic | Difficult to read | |

| Specific | Unappealing |

| Group . | Characteristics . | Judgments . |

|---|---|---|

| Exceptionals | Technical | Relevant |

| Jargonistic | Relatable | |

| Big picture | Easy to read | |

| Large-scale | Topical | |

| Pragmatic | Informative | |

| Descriptive | ||

| Influencers | Non-technical | Relevant |

| Big picture | Relatable | |

| Large-scale | Appealing | |

| Pragmatic | Emotional | |

| Controversial | ||

| Shareable | ||

| Scholars | Technical | Relevant |

| Jargonistic | Difficult to read | |

| Specific | Unappealing |

For the exceptionals, the abstracts were often described by researchers as technical and jargonistic. For example, one researcher described an article as having a: ‘very technical title with information that could interest the healthcare industry, probably the insurance industry like actuaries, something like that, seems to be very data oriented’. Another researcher noted of an abstract in this category that ‘although we do have some technical stuff, it’s the way it’s written’ that makes it clear. One researcher illustrated a tension between jargon and relevance: ‘I’m totally put off by the jargony stuff on this one, although I suppose I can see how that would resonate given certainly the debate in this country’. Abstracts in the exceptional category were also described as big picture, pragmatic (i.e. problem-focused) and descriptive. One researcher highlighted the scope of an article as providing ‘lessons learned from several countries in the region…’, while another described the set of abstracts as ‘just kind of big’. One researcher described one as presenting: ‘such a broad topic that it’s of course important but the way this is characterised is so abstracted…’ and another article as ‘a really crucial and important topic [that] seemed to be the most promising, like, rewarding my attention the most, there’s far less jargon in it…’. Another researcher summed up an article as ‘a very big descriptive exercise’. Abstracts from the exceptional category were frequently judged to be relevant, easy to read and topical. For example, a researcher described the set of abstracts by noting that they ‘read really well, and I think also the way that they’re written by having their problems set out really helps, so even if you can’t understand [the data], it’s immediately clear why they look at that, so this to me seem like they would be useful for a wider audience’. One researcher described the articles in this category as focusing on ‘appealing topics [with] the way the titles are written, very easy to comprehend… they’re topical and they’re more relevant to a wider audience’. Abstracts in the exceptional category were summed up by one researcher who noted: ‘I imagine this is valuable both in the academic community and the policy community’.

For the influencers, abstracts were described as non-technical, big picture, large-scale, and pragmatic. They were judged to be relevant and appealing. For example, one researcher described one abstract as: ‘something that anybody can understand, really important’, while another was described as ‘very interesting, like, now that you know this, what would you do differently?’ Researchers highlighted the scale of one abstract as a ‘big cross-country thing’ and a ‘big regional focus’. They also highlighted the pragmatic focus of one of the abstracts on a specific ‘topic, about what you’re getting out of the paper for this domain’. One abstract was described as starting ‘with a statement that people can relate to and then it really summarises what the problem is, you know, it’s orphans, you know that it’s Ebola, it’s trying to reach students or civil society.’ One researcher described an abstract as ‘something that people can really relate to, that would really catch people’s interest and help them see that it’s relevant’. Another researcher identified an abstract as ‘something that I would probably tweet about, because it is something that our audience would be interested in, more like there’s a story or a personal story behind it, not mostly technical so it’s more of something that they can relate to, or they can understand easily.’ Emotiveness, controversy, and relatability were also commonly mentioned. For example, one researcher noted that one abstract used ‘words that are likely to stir controversy or some sort of dilemma, to be disruptive, sort of emotionally–resonant words’. Another researcher highlighted the stakes of one of the articles: ‘we know what it’s going to be talking about and where, it’s Ebola, which conveys a message of disease and suffering and crisis and it’s specific which is orphans.’ The influencer category was summed up by researchers who noted that the abstracts were ‘kind of giving you the bottom line’ but ‘sort of underplayed the salient aspects of the debate’.

For the scholar category, articles were described as technical and jargonistic, which meant they were judged as difficult to read and unappealing. For example, one was described as ‘a lot of acronyms and then at the same time, jargon—technical jargon. I have to re-read it and then figure out, ‘Okay, what’s it trying to say?’ Another stated more forcefully: ‘I found this to be unbearable, it’s a lot of techy communication, it’s all mumbo jumbo, and even though it’s very techy, the actual method doesn’t come out very clearly. So, it’s like smoke and mirrors’. One researcher made a direct link between the characteristics of the paper and its likelihood of receiving citations, describing one abstract as ‘pretty boring and dense, so I could see why it will get cited’. Another offered a suggestion for the author of one abstract: ‘reduce this into two sentences and explain what the paper is about’. Abstracts in this category were also seen as more specific. For example, one researcher stated that one abstract was ‘more narrow in the sense that it’s not as regional or global, and more descriptive of a specific context’ while another was described as ‘more descriptive but still very intense in data and stuff’. The judgements of the abstracts in the scholar category were damming. One researcher stated: ‘I did not enjoy reading, it’s wordy, it’s really dry, and so it requires a lot of mental effort for the reader to stay with it and try to get sort of the gist.’ Another emphasised that the reader must ‘think twice to keep reading because you don’t know what’s really the problem, it’s just really hard to read, no wider audience would read this.’ Nonetheless, researchers could see the relevance of abstracts in this category. One noted that one abstract was ‘dealing with more focused issues that it’s easier to see why they’re important’, while another was described as ‘most academic in the sense it’s very precise, the study did this little thing looked at this bounded problem and found this’.

There were key differentiations between groups of abstracts, indicating that the extreme-case categories were valued in substantially different ways by expert peers. In terms of characteristics, outputs in the exceptional and influencer categories were both seen as pragmatic, large-scale, and big picture, with exceptionals seen as more descriptive, technical, and jargonistic, whereas influencers were seen as non-technical. Exceptionals and scholars were both seen as technical and jargonistic, but exceptionals were seen as big picture, large-scale, descriptive and pragmatic, and scholars were seen as specific. Scholars and influencers were opposites, with scholars seen as technical and jargonistic, and influencers as non-technical. In addition, where scholars were seen as specific, influencers were seen as large-scale and big picture. Accordingly, there were differences between groups in judgements. Exceptionals and influencers were both seen as relevant and relatable, but with exceptionals seen as easy to read, topical, and informative, while influencers were seen as controversial, emotional, appealing, and shareable. Exceptionals and scholars were both seen as relevant, although relevance for scholars was more tightly connected to what is important in the academic context. Exceptionals were seen as relatable, easy to read, topical, and informative whereas scholars were difficult to read and unappealing. Scholars and influencers were both seen as relevant, but scholars were difficult to read and unappealing, whereas influencers were relatable, emotional, appealing, controversial, and shareable. These findings are consistent with Lamont’s (2010) finding that when expert panels evaluate research proposals, significance and originality are the most important formal criteria used, followed by clarity and methods. It is crucial to remember that the outputs sampled here were all development-focused and were all written by professional economists or social scientists from the same organisation. As such, these perceived differences in characteristics and judgments might be even more pronounced if they were read by laypeople or non-subject specific experts.

Table 4 sets out the shared characteristics and judgements between categories. This overlap between multiple categories is telling. It shows that the organisation produces a range of outputs that can maintain coherence in multiple fields, which is central to the mission of the World Bank. Indeed, when publications are only technical and jargonistic they are seen as difficult to read (scholars), and when they are only big picture or pragmatic they are seen as not particularly informative (influencers), but in both contexts they are seen as relevant. However, when there is a balance of technical and jargonistic language that is also big picture and problem-focused, the publications are perceived as relevant, easy-to-read, and informative. There appears to be a delicate balancing act to successfully situating a publication as simultaneously credible, visible, useful, or authoritative. Overall, it appears that using a more jargonistic and specialised academic style can gain credibility with experts, but that strategy can backfire in wider contexts, where succinctness may be valued.

| Shared characteristics . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Technical . | Jargonistic . | Big-picture . | Large-scale . | Pragmatic . |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Shared judgements | |||||

| Relevant | Relatable | ||||

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Scholars | ✓ | ||||

| Shared characteristics . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Technical . | Jargonistic . | Big-picture . | Large-scale . | Pragmatic . |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Shared judgements | |||||

| Relevant | Relatable | ||||

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Scholars | ✓ | ||||

| Shared characteristics . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Technical . | Jargonistic . | Big-picture . | Large-scale . | Pragmatic . |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Shared judgements | |||||

| Relevant | Relatable | ||||

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Scholars | ✓ | ||||

| Shared characteristics . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Technical . | Jargonistic . | Big-picture . | Large-scale . | Pragmatic . |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Shared judgements | |||||

| Relevant | Relatable | ||||

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Scholars | ✓ | ||||

Table 5 sets out instances where categories were deemed to have opposing characteristics and judgements. This suggests that specific combinations of characteristics interact, such as the extent of technical language and assumed knowledge, which is deemed easy to read when combined with a big-picture focus, but hard to read when combined with a more specific or nuanced focus. In addition, the difficulty or ease of reading seems to capture something distinct from the appeal of the piece. Exceptionals were seen as easy to read but where not deemed especially appealing nor unappealing. This may suggest that a technical and jargonistic style can be balanced with a big-picture, large-scale, and pragmatic focus, thus rendering overall appeal less important than other features of the text. By contrast, influencers were seen as appealing, but neither particularly easy nor difficult to read. This might reflect something about their focus as big-picture, large-scale, and pragmatic, which makes relatability and relevance more salient than ease of reading.

| Opposing characteristics . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Non-technical | Specific | Big-picture | |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Opposing judgements | ||||

| Easy to read | Hard to read | Appealing | Unappealing | |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | |||

| Influencers | ✓ | |||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Opposing characteristics . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Non-technical | Specific | Big-picture | |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Opposing judgements | ||||

| Easy to read | Hard to read | Appealing | Unappealing | |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | |||

| Influencers | ✓ | |||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Opposing characteristics . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Non-technical | Specific | Big-picture | |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Opposing judgements | ||||

| Easy to read | Hard to read | Appealing | Unappealing | |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | |||

| Influencers | ✓ | |||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Opposing characteristics . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Non-technical | Specific | Big-picture | |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Influencers | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Opposing judgements | ||||

| Easy to read | Hard to read | Appealing | Unappealing | |

| Exceptionals | ✓ | |||

| Influencers | ✓ | |||

| Scholars | ✓ | ✓ | ||

These insights reflect the hybrid orientation of the World Bank. One senior leader at the Bank summed up the goals of Bank:

“I think we should be insistent that every piece of knowledge that we do is actually shared with the public. Now you can say, ‘Well, that’s what we know, the access to information is already in our rules and regulations.’ But in practice … there is still a tension from time to time. Not always, but there can be a tension between the government and the Bank around this idea of disseminating this knowledge work to the general public… To me it’s a moral issue. I feel an obligation to do that. But then finally on a pragmatic basis, we have to get this information, this research, these indicators in a manner that’s accessible to those people that matter.”

Indeed, the Bank seems adept at meeting the varied criteria of knowledge production. Bank researchers speak to academic audiences using jargon and technical details, and they endeavour to make these insights relevant by focusing on the overall context, applying the knowledge to large populations, and focusing on real-world problems to be solved. Yet, it is not straightforward to balance these requirements to produce scholarly outputs that are appealing, accessible, and pertinent to everyday audiences. Thus, the results show the varied orientations of those who are tasked with producing knowledge at the World Bank.

Crucially, this analysis provides key insights into the metrics of citations and altmetrics, demonstrating that there is something qualitatively different about those that fall within the boundaries of each extreme-case category. The study suggests that verbose, academically contextualised publications are valued differently to pithy, direct, and less academically grounded outputs. Thus, the narrative interviews provide a consistent but more nuanced picture than can be simply derived from metrics alone. Crucially, by considering the categories as an expression of expert valuations, it is clear that there are different possible combinations of credibility, utility, visibility and authority that manifest as sets of characteristics and accompanying judgements.

5. Conclusion

This article provides a new way of understanding research value by examining how expert peers evaluate categories of research outputs derived from metrics of academic and wider influence. The analysis suggests that there are meaningful differences between the outputs in each theoretically derived category, and provides insight into the complex relationship between different practices of valuation. When looking at extreme-case categories as an expression of value (e.g. exceptionals are highly valued both inside and outside the academic system, while influencers are more highly valued outside the academic system), it is clear that organisations can negotiate different possible combinations of symbolic resources from different fields. The analysis supports the idea that those outputs that score highly on both citations and altmetrics are able to balance the preferences of academic and wider audiences, and thus gain a mix of symbolic resources from a range of relevant fields. Overall, using citations and altmetrics in combination, it is possible to broadly determine what kinds of outputs gain credibility on the one hand, and other symbolic resources, such as visibility, utility, authority, on the other.

The World Bank seeks to influence a range of audiences, including academia, politics, practice, media, and business. It thus successfully straddles a range of fields, producing research that is valued by multiple audiences and different contexts. By holding multiple evaluative principles in play, the World Bank fosters a ‘generative friction’ that makes new combinations of symbolic resources possible (Stark 2016). To varying degrees, the publications in the extreme-case categories inhabit multiple overlapping social worlds and establish and sustain coherence across them. By situating the extreme-case categories and demonstrating what is specific about them, it is clear that they are not purely theoretical categories. There are substantially different types of valuations given by expert peers. This type of analysis could be useful for researchers thinking about where and what type of outputs they want to publish, but also for management to reflect on reward and incentive systems, or for communications staff to explore the outputs that are likely to be popular and those that could benefit from more active dissemination. Indeed, examining the exceptional category in more detail might be a useful starting point for devising strategies for producing outputs that are simultaneously valued by academic and wider audiences.

Although this approach provides a novel way of examining the operationalisation of research value through citations and altmetric attention scores, there are a number of limitations to this strategy. One limitation is that when selecting the three key theoretical categories, there are very few publications with high citations and low altmetrics, and thus the scholars’ category is very small. As noted above, if zero values for altmetric attention scores were included, the ‘scholars’ condition would likely include additional publications of relevance to the study. This reduces the insights that can be gained from comparing categories. Another key limitation is the reliance on unique identifiers (mainly DOI), which excludes many publication types that are published by the World Bank (e.g. flagship reports) that are not indexed in the Web of Science. These outputs would likely fall into the influencer category, receiving a high degree of online influence without receiving citations. In addition, the dataset includes outputs published with at least one author at the Bank, which may be influenced by how the Web of Science attributes to the World Bank, potentially excluding relevant outputs. Future research might address these issues via analysis of a much broader range of outputs in each category, ideally looking at publications over a range of years and from different organisations. Most crucially, a key limitation is that this article did not consider the constituent parts of altmetrics in their own right. The relationship between the altmetric attention score and sources other than Twitter were not unpacked, and thus the underlying meanings behind other ‘mentions’, ‘shares’, and ‘likes’ that might be more relevant than Twitter engagement are left unaddressed. Future work might focus on the relationship between citations and specific key areas of interest (i.e. mentions in news media or policy mentions) to address the limitation of the compound metric and to understand different elements of external value. These elements deserve deeper inquiry in future research.

Much of the existing literature focuses on the relationship between altmetrics and citations, working from the idea that the two metrics measure related but separate things. Although this analysis confirms the expectation that outputs that receive a higher number of citations tend to also receive higher altmetric attention scores, it builds on existing theoretical work (Haustein et al. 2016) to make sense of this picture. This article went beyond correlation analysis to explore how the value regimes around academic influence and wider engagement come together. It shows that metrics flatten the crucial elements of how multiple fields are negotiated and, thus, need to be consciously examined. It provides an important step in developing more reflexive bibliometric and altmetric analysis, where an overarching theoretical framework can be used to combine qualitative and quantitative insights. Despite a strong correlation between citations and altmetrics (and more specifically, Twitter mentions), the article provides further evidence that bibliometrics and altmetrics conform to different areas of influence, combining important differences and similarities. Furthermore, it provides a novel way of understanding the shared value of research outputs that brings together the valuation practices of metrics and peer review. This type of holistic analysis is important because it addresses the issue of the ability of metrics to appropriately represent value. This is a key question not only for individual researchers balancing multiple goals and logics across fields, but also for research managers seeking to improve research production and evaluation processes, in addition to furthering general understanding and improvement of existing measures. Further research is required to explore how the findings observed in this article play out across organisational, disciplinary, and national boundaries.

Funding

This work was supported by two ESRC (UK) grants: ES/N016319/1 and ES/V004123/1.

Conflict of interest statement.

None declared.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dr Kobe De Keere, Dr Stefan Beljean, and Dr Jonathan Mijs who reviewed a previous version of this article and to Dr Stephan Gauch who provided valuable insights into the design and methodology.

Footnotes

Those outputs lowest in both citations and altmetrics, and those other outputs not included in the exceptional, scholar or influencer categories were not examined in this study, given the theoretical interest in high performing outputs.

Specifically, the JIF (a measure that considers a journal’s influence on a specific scientific field), the Eigen factor (i.e. a measure of a journal’s prestige across fields, which takes into account the journals that citations come from) and the h-index (i.e. a measure of productivity and scientific recognition that depends on the specific scientific field) each rely on citation counts.

These labels are intended to evocatively capture something about the most extreme-case outputs; however, these categories could also feasibly include other papers (e.g. the notion of influencer could also be attributed to other papers that have high altmetric attention scores but moderate number of citations).

More information about how the attention score is calculated can be found here: https://help.altmetric.com/support/solutions/articles/6000233311-how-is-the-altmetric-attention-score-calculated-.

See https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2021/08/24/unpacking-the-altmetric-black-box/ for further discussion.

References

—— et al. (

—— (

TULIP SET [EXCEPTIONALS]

| Title . | Abstract . |

|---|---|

| Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 | Up-to-date evidence about levels and trends in disease and injury incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability (YLDs) is an essential input into global, regional, and national health policies. In the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 (GBD 2013), we estimated these quantities for acute and chronic diseases and injuries for 188 countries between 1990 and 2013. Estimates were calculated for disease and injury incidence, prevalence, and YLDs using GBD 2010 methods with some important refinements. Results for incidence of acute disorders and prevalence of chronic disorders are new additions to the analysis. Key improvements include expansion to the cause and sequelae list, updated systematic reviews, use of detailed injury codes, improvements to the Bayesian meta-regression method (DisMod-MR), and use of severity splits for various causes. An index of data representativeness, showing data availability, was calculated for each cause and impairment during three periods globally and at the country level for 2013. In total, 35 620 distinct sources of data were used and documented to calculated estimates for 301 diseases and injuries & 2337 sequelae… Ageing of the world’s population is leading to a substantial increase in the numbers of individuals with sequelae of diseases and injuries. Rates of YLDs are declining much more slowly than mortality rates. The non-fatal dimensions of disease and injury will require more and more attention from health systems The transition to non-fatal outcomes as the dominant source of burden of disease is occurring rapidly outside of sub-Saharan Africa. Our results can guide future health initiatives through examination of epidemiological trends and a better understanding of variation across countries. |

| Systems integration for global sustainability | Global sustainability challenges, from maintaining biodiversity to providing clean air and water, are closely interconnected yet often separately studied and managed. Systems integration—holistic approaches to integrating various components of coupled human and natural systems—is critical to understand socioeconomic and environmental interconnections and to create sustainability solutions. Recent advances include the development and quantification of integrated frameworks that incorporate ecosystem services, environmental footprints, planetary boundaries, human-nature nexuses, and telecoupling. Although systems integration has led to fundamental discoveries and practical applications, further efforts are needed to incorporate more human and natural components simultaneously, quantify spillover systems and feedbacks, integrate multiple spatial and temporal scales, develop new tools, and translate findings into policy and practice. Such efforts can help address important knowledge gaps, link seemingly unconnected challenges, and inform policy and management decisions. |

| Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America | Starting in the late 1980s, many Latin American countries began social sector reforms to alleviate poverty, reduce socioeconomic inequalities, improve health outcomes, and provide financial risk protection. In particular, starting in the 1990s, reforms aimed at strengthening health systems to reduce inequalities in health access and outcomes focused on expansion of universal health coverage, especially for poor citizens. In Latin America, health-system reforms have produced a distinct approach to universal health coverage, underpinned by the principles of equity, solidarity, and collective action to overcome social inequalities. In most of the countries studied, government financing enabled the introduction of supply-side interventions to expand insurance coverage for uninsured citizens—with defined and enlarged benefits packages—and to scale up delivery of health services. Countries such as Brazil and Cuba introduced tax-financed universal health systems. These changes were combined with demand-side interventions aimed at alleviating poverty (targeting many social determinants of health) and improving access of the most disadvantaged populations. Hence, the distinguishing features of health-system strengthening for universal health coverage and lessons from the Latin American experience are relevant for countries advancing universal health coverage. |

| Title . | Abstract . |

|---|---|

| Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 | Up-to-date evidence about levels and trends in disease and injury incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability (YLDs) is an essential input into global, regional, and national health policies. In the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 (GBD 2013), we estimated these quantities for acute and chronic diseases and injuries for 188 countries between 1990 and 2013. Estimates were calculated for disease and injury incidence, prevalence, and YLDs using GBD 2010 methods with some important refinements. Results for incidence of acute disorders and prevalence of chronic disorders are new additions to the analysis. Key improvements include expansion to the cause and sequelae list, updated systematic reviews, use of detailed injury codes, improvements to the Bayesian meta-regression method (DisMod-MR), and use of severity splits for various causes. An index of data representativeness, showing data availability, was calculated for each cause and impairment during three periods globally and at the country level for 2013. In total, 35 620 distinct sources of data were used and documented to calculated estimates for 301 diseases and injuries & 2337 sequelae… Ageing of the world’s population is leading to a substantial increase in the numbers of individuals with sequelae of diseases and injuries. Rates of YLDs are declining much more slowly than mortality rates. The non-fatal dimensions of disease and injury will require more and more attention from health systems The transition to non-fatal outcomes as the dominant source of burden of disease is occurring rapidly outside of sub-Saharan Africa. Our results can guide future health initiatives through examination of epidemiological trends and a better understanding of variation across countries. |

| Systems integration for global sustainability | Global sustainability challenges, from maintaining biodiversity to providing clean air and water, are closely interconnected yet often separately studied and managed. Systems integration—holistic approaches to integrating various components of coupled human and natural systems—is critical to understand socioeconomic and environmental interconnections and to create sustainability solutions. Recent advances include the development and quantification of integrated frameworks that incorporate ecosystem services, environmental footprints, planetary boundaries, human-nature nexuses, and telecoupling. Although systems integration has led to fundamental discoveries and practical applications, further efforts are needed to incorporate more human and natural components simultaneously, quantify spillover systems and feedbacks, integrate multiple spatial and temporal scales, develop new tools, and translate findings into policy and practice. Such efforts can help address important knowledge gaps, link seemingly unconnected challenges, and inform policy and management decisions. |

| Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America | Starting in the late 1980s, many Latin American countries began social sector reforms to alleviate poverty, reduce socioeconomic inequalities, improve health outcomes, and provide financial risk protection. In particular, starting in the 1990s, reforms aimed at strengthening health systems to reduce inequalities in health access and outcomes focused on expansion of universal health coverage, especially for poor citizens. In Latin America, health-system reforms have produced a distinct approach to universal health coverage, underpinned by the principles of equity, solidarity, and collective action to overcome social inequalities. In most of the countries studied, government financing enabled the introduction of supply-side interventions to expand insurance coverage for uninsured citizens—with defined and enlarged benefits packages—and to scale up delivery of health services. Countries such as Brazil and Cuba introduced tax-financed universal health systems. These changes were combined with demand-side interventions aimed at alleviating poverty (targeting many social determinants of health) and improving access of the most disadvantaged populations. Hence, the distinguishing features of health-system strengthening for universal health coverage and lessons from the Latin American experience are relevant for countries advancing universal health coverage. |

TULIP SET [EXCEPTIONALS]

| Title . | Abstract . |

|---|---|

| Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 | Up-to-date evidence about levels and trends in disease and injury incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability (YLDs) is an essential input into global, regional, and national health policies. In the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 (GBD 2013), we estimated these quantities for acute and chronic diseases and injuries for 188 countries between 1990 and 2013. Estimates were calculated for disease and injury incidence, prevalence, and YLDs using GBD 2010 methods with some important refinements. Results for incidence of acute disorders and prevalence of chronic disorders are new additions to the analysis. Key improvements include expansion to the cause and sequelae list, updated systematic reviews, use of detailed injury codes, improvements to the Bayesian meta-regression method (DisMod-MR), and use of severity splits for various causes. An index of data representativeness, showing data availability, was calculated for each cause and impairment during three periods globally and at the country level for 2013. In total, 35 620 distinct sources of data were used and documented to calculated estimates for 301 diseases and injuries & 2337 sequelae… Ageing of the world’s population is leading to a substantial increase in the numbers of individuals with sequelae of diseases and injuries. Rates of YLDs are declining much more slowly than mortality rates. The non-fatal dimensions of disease and injury will require more and more attention from health systems The transition to non-fatal outcomes as the dominant source of burden of disease is occurring rapidly outside of sub-Saharan Africa. Our results can guide future health initiatives through examination of epidemiological trends and a better understanding of variation across countries. |

| Systems integration for global sustainability | Global sustainability challenges, from maintaining biodiversity to providing clean air and water, are closely interconnected yet often separately studied and managed. Systems integration—holistic approaches to integrating various components of coupled human and natural systems—is critical to understand socioeconomic and environmental interconnections and to create sustainability solutions. Recent advances include the development and quantification of integrated frameworks that incorporate ecosystem services, environmental footprints, planetary boundaries, human-nature nexuses, and telecoupling. Although systems integration has led to fundamental discoveries and practical applications, further efforts are needed to incorporate more human and natural components simultaneously, quantify spillover systems and feedbacks, integrate multiple spatial and temporal scales, develop new tools, and translate findings into policy and practice. Such efforts can help address important knowledge gaps, link seemingly unconnected challenges, and inform policy and management decisions. |

| Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America | Starting in the late 1980s, many Latin American countries began social sector reforms to alleviate poverty, reduce socioeconomic inequalities, improve health outcomes, and provide financial risk protection. In particular, starting in the 1990s, reforms aimed at strengthening health systems to reduce inequalities in health access and outcomes focused on expansion of universal health coverage, especially for poor citizens. In Latin America, health-system reforms have produced a distinct approach to universal health coverage, underpinned by the principles of equity, solidarity, and collective action to overcome social inequalities. In most of the countries studied, government financing enabled the introduction of supply-side interventions to expand insurance coverage for uninsured citizens—with defined and enlarged benefits packages—and to scale up delivery of health services. Countries such as Brazil and Cuba introduced tax-financed universal health systems. These changes were combined with demand-side interventions aimed at alleviating poverty (targeting many social determinants of health) and improving access of the most disadvantaged populations. Hence, the distinguishing features of health-system strengthening for universal health coverage and lessons from the Latin American experience are relevant for countries advancing universal health coverage. |

| Title . | Abstract . |

|---|---|