-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Caitlin E Martin, Hetal Patel, Joseph M Dzierzewski, F Gerard Moeller, Laura J Bierut, Richard A Grucza, Kevin Y Xu, Benzodiazepine, Z-drug, and sleep medication prescriptions in male and female people with opioid use disorder on buprenorphine and comorbid insomnia: an analysis of multistate insurance claims, Sleep, Volume 46, Issue 6, June 2023, zsad083, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsad083

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

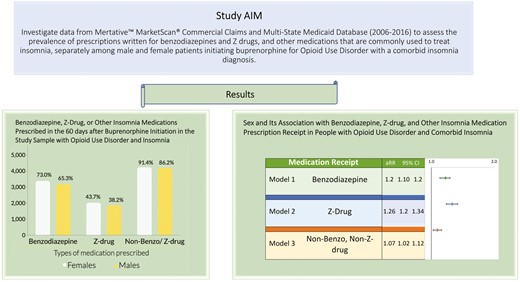

In adult populations, women are more likely than men to be prescribed benzodiazepines. However, such disparities have not been investigated in people with opioid use disorder (OUD) and insomnia receiving buprenorphine, a population with particularly high sedative/hypnotic receipt. This retrospective cohort study used administrative claims data from Merative MarketScan Commercial and MultiState Medicaid Databases (2006–2016) to investigate sex differences in the receipt of insomnia medication prescriptions among patients in OUD treatment with buprenorphine.

We included people aged 12–64 years with diagnoses of insomnia and OUD-initiating buprenorphine during the study timeframe. The predictor variable was sex (female versus male). The primary outcome was receipt of insomnia medication prescription within 60 days of buprenorphine start, encompassing benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, or non-sedative/hypnotic insomnia medications (e.g. hydroxyzine, trazodone, and mirtazapine). Associations between sex and benzodiazepine, Z-drug, and other insomnia medication prescription receipt were estimated using Poisson regression models.

Our sample included 9510 individuals (female n = 4637; male n = 4873) initiating buprenorphine for OUD who also had insomnia, of whom 6569 (69.1%) received benzodiazepines, 3891 (40.9%) Z-drugs, and 8441 (88.8%) non-sedative/hypnotic medications. Poisson regression models, adjusting for sex differences in psychiatric comorbidities, found female sex to be associated with a slightly increased likelihood of prescription receipt: benzodiazepines (risk ratio [RR], RR = 1.17 [1.11–1.23]), Z-drugs (RR = 1.26 [1.18–1.34]), and non-sedative/hypnotic insomnia medication (RR = 1.07, [1.02–1.12]).

Sleep medications are commonly being prescribed to individuals with insomnia in OUD treatment with buprenorphine, with sex-based disparities indicating a higher prescribing impact among female than male OUD treatment patients.

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder among people with opioid use disorder (OUD). Emerging evidence indicates that insomnia symptoms can place patients in OUD treatment at risk of poor outcomes, including recurrence of substance use and overdose. Thus, targeting insomnia with adjunctive, evidence-based interventions within the OUD treatment setting may be an effective avenue to optimize treatment and recovery outcomes for this patient population. However, data from studies on pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic insomnia treatments conducted in this patient population is severely lacking. This study emphasizes the need for more investigation at this intersection through a sex-informed lens, illustrating very high impacts of medication prescribing (i.e. benzodiazepines) among patients in OUD treatment, especially for females.

Introduction

Since the 1960s, benzodiazepines have been heavily marketed for the treatment of insomnia and other psychiatric conditions, becoming among the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medications worldwide. From the time of their inception, benzodiazepines have also been the subject of gendered cultural connotations [1, 2] and were historically marketed via advertisements claiming to assist women with the stresses of work and parenting, vividly illustrated by diazepam (Valium )’s immortalization in the 1966 song “Mother’s Little Helper” by The Rolling Stones [2].

While higher rates of benzodiazepine prescribing [3–6] and insomnia diagnoses [7, 8] have consistently been observed among female relative to male patients in adult samples worldwide, sex-based differences in benzodiazepine and other insomnia medication prescribing have not been thoroughly studied in people with opioid use disorder (OUD). Patients with OUD, especially those in early sobriety and/or initial stages of treatment with medications for (MOUD), such as buprenorphine, constitute a vulnerable population with an especially high prevalence of insomnia [9, 10]. Furthermore, it is estimated that up to 30% of patients receiving MOUD also receive benzodiazepine prescriptions [11]. To date, effective interventions for insomnia are under investigation within OUD treatment samples, even though sleep disturbance in such individuals is associated with poor outcomes (e.g. substance use recurrence, overdose) via multiple proposed underlying mechanisms, such as persistent opioid cravings, impaired executive function, emotional dysregulation, and increased pain sensitivity [12, 13]. Altogether, many patients in OUD treatment with comorbid insomnia, especially women, may be facing compounded risks for substance use recurrence and overdose, related to the simultaneous contributions by inadequately managed insomnia symptoms [14] as well as benzodiazepine receipt [15].

Fundamental sex-based characterization of prescribing patterns for benzodiazepines and other medications for sleep among patients with insomnia in OUD treatment is presently lacking, yet this knowledge is essential to establish a foundation for the development of targeted interventions to achieve sex and gender equity in OUD clinical care. Therefore, we investigated data from the Merative MarketScan Commercial Database and the MultiState Medicaid Database (2006–2016) to assess the prevalence of prescriptions written for benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, and other medications that are commonly used to treat insomnia, separately among male and female patients initiating buprenorphine for OUD with a comorbid insomnia diagnosis. We intentionally focused our investigation on individuals in OUD treatment with buprenorphine given the urgency for expanded buprenorphine access across outpatient settings (e.g. recent elimination of the need for a provider to have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine), with the goal to optimize the clinical applicability of our findings in the ongoing overdose crisis.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a retrospective cohort study using the Merative MarketScan Commercial and MultiState Medicaid Databases, which include comprehensive longitudinal clinical, enrollment, and pharmacy data for all clinical encounters and filled prescriptions throughout the United States, as previously described [15]. The MarketScan Commercial Database includes claims for employees, spouses, and their dependents from multiple major employers and health plans. The MarketScan MultiState Medicaid Database encompasses claims from enrollees from 11 states, which are kept unknown to the public [15]. Data were available from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2016. Analyses were conducted from July 15, 2022 through September 22, 2022. This study was exempt from IRB review because no identifiable private data was used.

Participants and observation window

The sample was derived from 304 676 insured people in the United States with a diagnosis of OUD, derived from ICD-9/10 codes, who initiated OUD treatment with buprenorphine, and had a 6-month minimum of pharmacy and medical coverage prior to buprenorphine start, as this represents a standard baseline look-back period for covariate assessment [15, 16]. We included people aged 12 to 65 years of age to include both adults and adolescent populations who experience OUD [17].

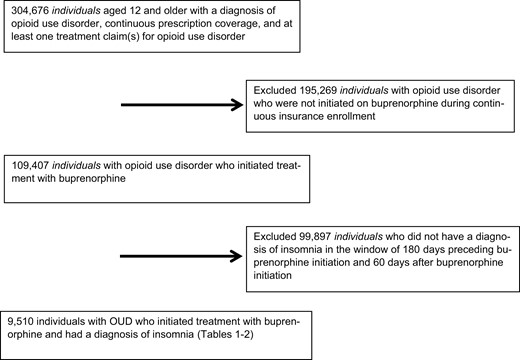

A retrospective cohort design evaluated sex-specific rates of insomnia medication prescription receipt (i.e. of filled medications). To derive the analytic sample (Figure 1), we excluded 195 269 people with OUD who were not initiated on buprenorphine during the study timeframe, as our study was focused on the population of people receiving OUD treatment with buprenorphine. This culminated in 109 407 people with OUD who initiated buprenorphine. We subsequently excluded 99 897 people who did not have a diagnosis of insomnia in the window of 180 days preceding buprenorphine initiation and up to 60 days after buprenorphine initiation. This culminated in a sample of 9510 people with OUD who were initiating buprenorphine and had a diagnosis of insomnia who we evaluated for insomnia medication prescription receipt.

Derivation of the analytic sample. The study sample consisted of individuals in the MarketScan Databases, years 2006–2016, with a diagnosis of opioid use disorder who initiated buprenorphine treatment, and who also had an additional documented diagnosis of insomnia.

We identified people initiating buprenorphine for OUD using pharmacy claims and National Drug Codes, as previously described (Supplementary Table 1) [15]. Buprenorphine initiation was defined as a new, continuous treatment episode that was not preceded by treatment claims for at least 45 days and without lapses in dispensing or fills exceeding 45 days. It was assumed that active prescriptions or procedure codes for buprenorphine connoted medication consumption [15].

Variables

The primary outcome was the binary variable of prescription receipt for medications that are commonly used to treat insomnia in the 60 days following buprenorphine initiation, including: benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and others—SSRIs, trazodone, mirtazapine, gabapentin, quetiapine, and hydroxyzine. The prevalence of prescription receipt is presented for the total sample as well as separately by sex (male/female).

We also assessed the association of the binary variable of sex (female vs. male) with the outcome of insomnia medication prescription receipt (three categories: benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and others). In doing so, covariates for the multivariable analyses included variables available in the dataset that correspond to factors known to be associated with disparities in sleep health [18], including: age at start of OUD treatment (in years), Medicaid versus commercial insurance, and ICD-9/10 diagnostic codes in a time period of 6 months preceding buprenorphine initiation and up to 60 days after buprenorphine initiation: mood disorder (depression or bipolar disorder), anxiety disorders (composite of posttraumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety, and anxiety disorder unspecified), cooccurring SUDs (alcohol, cannabis, sedative-hypnotics [benzodiazepines, Z-drugs], stimulants [methamphetamines, cocaine], tobacco), and non-psychiatric disorders (chronic pain, diabetes, epilepsy, fibromyalgia, migraine, and irritable bowel syndrome).

Statistical analyses

First, we computed descriptive statistics among female and male individuals, including for age, clinical characteristics (insurance status, race [among Medicaid enrollees], cooccurring SUDs, mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders), and insomnia medication prescriptions received in the 60 days after buprenorphine initiation (benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, others—SSRIs, trazodone, mirtazapine, gabapentin, quetiapine, hydroxyzine).

To examine the association of sex with insomnia medication prescription receipt, we used Poisson regression with robust standard errors [19]. The Poisson models are highly robust to outliers and non-linear confounders compared to the log-binomial models when estimating risk ratio (RR)s for common binary outcomes (i.e. medication receipt) [20]. Three separate models assessed the association of sex with prescription receipt, corresponding to the three medication groups: benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and others. Model covariates included the variables listed above. All reported P-values were two-sided, with a significance level of 0.05. All analyses were conducted via SAS version 9.4.

Results

Study sample characteristics

Analyses included 9510 individuals (n = 4637 [48.8%] female) initiating buprenorphine for OUD who had a cooccurring insomnia diagnosis. The mean [SD] age was 37.0 [11.7] years, and 3342 [35.1%] were Medicaid enrollees. Among Medicaid enrollees, 43 identified as Hispanic (0.5%),162 non-Hispanic Black (1.7%), 2588 non-Hispanic White (77.4%), and 133 (4.0%) identified as other race or ethnicity, including people who fell into categories other than Black, Hispanic, or White (Table 1). Within Non-Hispanic Black (70% female, 30% male) and White (69% female, 31% male) Medicaid enrollees initiating buprenorphine for OUD with insomnia, similar proportions identified as male and female (data not shown).

Characteristics of Study Sample and Receipt of Benzodiazepine, Z-Drug, and Other Insomnia Medications Among Individuals With OUD Initiating Buprenorphine With a Comorbid Insomnia Diagnosis

| . | Total sample, n = 9510 . | Females, n = 4637 . | Males, n = 4873 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years, SD) | 37.0 (11.7) | 37.0 (11.2) | 37.0 (12.2) |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Race and ethnicity (only available for Medicaid) | |||

| Hispanic | 43 (0.5) | 26 (1.2) | 17 (1.5) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2588 (77.4) | 1796 (80.4) | 792 (71.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 162 (1.7) | 113 (5.1) | 49 (4.4) |

| Other | 416 (4.4) | 230 (10.3) | 186 (16.8) |

| Missing | 133 (4.0) | 70 (3.1) | 63 (5.7) |

| Insurance type | |||

| Medicaid | 3342 (35.1) | 2235 (48.2) | 1107 (22.7) |

| Commercial | 6168 (64.9) | 2402 (51.8) | 3766 (77.3) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Comorbid stimulant use disorder | 721 (7.6) | 392 (8.5) | 329 (6.8) |

| Comorbid alcohol use disorder | 997 (10.5) | 394 (8.5) | 603 (12.4) |

| Comorbid sedative use disorder | 756 (8.0) | 378 (8.2) | 378 (7.8) |

| Mood disorder | 5810 (61.1) | 3270 (70.5) | 2540 (52.1) |

| Anxiety disorder | 8795 (92.5) | 4408 (95.1) | 4387 (90.0) |

| Chronic pain | 6358 (66.9) | 3333 (71.9) | 3025 (62.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1233 (13.0) | 566 (12.2) | 667 (13.7) |

| Epilepsy | 661 (7.0) | 408 (8.8) | 253 (5.2) |

| Fibromyalgia | 1019 (10.7) | 755 (16.3) | 264 (5.4) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 204 (2.2) | 153 (3.3) | 51 (1.1) |

| Migraine | 1354 (14.2) | 981 (21.2) | 373 (7.7) |

| . | Total sample, n = 9510 . | Females, n = 4637 . | Males, n = 4873 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years, SD) | 37.0 (11.7) | 37.0 (11.2) | 37.0 (12.2) |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Race and ethnicity (only available for Medicaid) | |||

| Hispanic | 43 (0.5) | 26 (1.2) | 17 (1.5) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2588 (77.4) | 1796 (80.4) | 792 (71.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 162 (1.7) | 113 (5.1) | 49 (4.4) |

| Other | 416 (4.4) | 230 (10.3) | 186 (16.8) |

| Missing | 133 (4.0) | 70 (3.1) | 63 (5.7) |

| Insurance type | |||

| Medicaid | 3342 (35.1) | 2235 (48.2) | 1107 (22.7) |

| Commercial | 6168 (64.9) | 2402 (51.8) | 3766 (77.3) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Comorbid stimulant use disorder | 721 (7.6) | 392 (8.5) | 329 (6.8) |

| Comorbid alcohol use disorder | 997 (10.5) | 394 (8.5) | 603 (12.4) |

| Comorbid sedative use disorder | 756 (8.0) | 378 (8.2) | 378 (7.8) |

| Mood disorder | 5810 (61.1) | 3270 (70.5) | 2540 (52.1) |

| Anxiety disorder | 8795 (92.5) | 4408 (95.1) | 4387 (90.0) |

| Chronic pain | 6358 (66.9) | 3333 (71.9) | 3025 (62.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1233 (13.0) | 566 (12.2) | 667 (13.7) |

| Epilepsy | 661 (7.0) | 408 (8.8) | 253 (5.2) |

| Fibromyalgia | 1019 (10.7) | 755 (16.3) | 264 (5.4) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 204 (2.2) | 153 (3.3) | 51 (1.1) |

| Migraine | 1354 (14.2) | 981 (21.2) | 373 (7.7) |

Characteristics of Study Sample and Receipt of Benzodiazepine, Z-Drug, and Other Insomnia Medications Among Individuals With OUD Initiating Buprenorphine With a Comorbid Insomnia Diagnosis

| . | Total sample, n = 9510 . | Females, n = 4637 . | Males, n = 4873 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years, SD) | 37.0 (11.7) | 37.0 (11.2) | 37.0 (12.2) |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Race and ethnicity (only available for Medicaid) | |||

| Hispanic | 43 (0.5) | 26 (1.2) | 17 (1.5) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2588 (77.4) | 1796 (80.4) | 792 (71.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 162 (1.7) | 113 (5.1) | 49 (4.4) |

| Other | 416 (4.4) | 230 (10.3) | 186 (16.8) |

| Missing | 133 (4.0) | 70 (3.1) | 63 (5.7) |

| Insurance type | |||

| Medicaid | 3342 (35.1) | 2235 (48.2) | 1107 (22.7) |

| Commercial | 6168 (64.9) | 2402 (51.8) | 3766 (77.3) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Comorbid stimulant use disorder | 721 (7.6) | 392 (8.5) | 329 (6.8) |

| Comorbid alcohol use disorder | 997 (10.5) | 394 (8.5) | 603 (12.4) |

| Comorbid sedative use disorder | 756 (8.0) | 378 (8.2) | 378 (7.8) |

| Mood disorder | 5810 (61.1) | 3270 (70.5) | 2540 (52.1) |

| Anxiety disorder | 8795 (92.5) | 4408 (95.1) | 4387 (90.0) |

| Chronic pain | 6358 (66.9) | 3333 (71.9) | 3025 (62.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1233 (13.0) | 566 (12.2) | 667 (13.7) |

| Epilepsy | 661 (7.0) | 408 (8.8) | 253 (5.2) |

| Fibromyalgia | 1019 (10.7) | 755 (16.3) | 264 (5.4) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 204 (2.2) | 153 (3.3) | 51 (1.1) |

| Migraine | 1354 (14.2) | 981 (21.2) | 373 (7.7) |

| . | Total sample, n = 9510 . | Females, n = 4637 . | Males, n = 4873 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years, SD) | 37.0 (11.7) | 37.0 (11.2) | 37.0 (12.2) |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Race and ethnicity (only available for Medicaid) | |||

| Hispanic | 43 (0.5) | 26 (1.2) | 17 (1.5) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2588 (77.4) | 1796 (80.4) | 792 (71.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 162 (1.7) | 113 (5.1) | 49 (4.4) |

| Other | 416 (4.4) | 230 (10.3) | 186 (16.8) |

| Missing | 133 (4.0) | 70 (3.1) | 63 (5.7) |

| Insurance type | |||

| Medicaid | 3342 (35.1) | 2235 (48.2) | 1107 (22.7) |

| Commercial | 6168 (64.9) | 2402 (51.8) | 3766 (77.3) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Comorbid stimulant use disorder | 721 (7.6) | 392 (8.5) | 329 (6.8) |

| Comorbid alcohol use disorder | 997 (10.5) | 394 (8.5) | 603 (12.4) |

| Comorbid sedative use disorder | 756 (8.0) | 378 (8.2) | 378 (7.8) |

| Mood disorder | 5810 (61.1) | 3270 (70.5) | 2540 (52.1) |

| Anxiety disorder | 8795 (92.5) | 4408 (95.1) | 4387 (90.0) |

| Chronic pain | 6358 (66.9) | 3333 (71.9) | 3025 (62.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1233 (13.0) | 566 (12.2) | 667 (13.7) |

| Epilepsy | 661 (7.0) | 408 (8.8) | 253 (5.2) |

| Fibromyalgia | 1019 (10.7) | 755 (16.3) | 264 (5.4) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 204 (2.2) | 153 (3.3) | 51 (1.1) |

| Migraine | 1354 (14.2) | 981 (21.2) | 373 (7.7) |

For cooccurring SUDs, 721 (7.6%) had a cooccurring stimulant use disorder (n = 392 [8.5%] females vs. n = 329 [6.8%] males), 997 (10.5%) alcohol use disorder (n = 394 [8.5%] females vs. n = 603 [12.4%] males), and 756 (8.0%) sedative use disorder (n = 378 [8.2%] females vs. n = 378 [7.8%] males). With regards to cooccurring mental health conditions overall, 5810 (61.1%) had a mood disorder and 8795 (92.5%) had an anxiety disorder. Whereas 2540 (52.1%) and 4387 (90%) of male patients had a mood and anxiety disorder, respectively, this figure was 3270 (70.5%) and 4408 (95.1%) among female patients. Among cooccurring medical conditions, two-thirds (n = 6358, 66.9% overall) of the sample had chronic pain diagnoses (3333 [71.9%] for females vs. 3025 [62.1%] for males).

Receipt of insomnia medication prescriptions after buprenorphine initiation

As shown in Table 2, 6569 (69.1%) patients received benzodiazepine prescriptions during the 60 days following buprenorphine initiation (3385 [73%] of females compared to 3184 [65.3%] for males), whereas 3891 (40.9%) received Z-drug prescriptions (2028 [43.7%] for females vs. 1863 [38.2%] for males). Among benzodiazepine subtypes, 5178 (54.5%) received short-acting agents (2745 [59.2%] for females vs. 2433 [49.9%] for males) and 4807 (50.6%) received long-acting agents (2505 [54.0%] for females vs. 2302 [47.2%] for males). Most of the sample received prescriptions for other medications typically used to treat insomnia (n = 8441 [88.8%]; 4239 [91.4%] for females vs. 4202 [86.2%] for males), such as SSRIs (5271 [55.4%]), trazodone (4815 [50.6%]) and gabapentin (n = 4867 [51.2%]). Most buprenorphine treatment episodes with insomnia medication receipt consisted of prescriptions for three or more different agents, especially among females (43% of females’ episodes, 33% of males’ episodes); episodes with prescriptions for two medications (18% females, 20% males) or a single medication (20% females, 23% males) were slightly more common among males (data not shown).

Benzodiazepine, Z-Drug, or Other Insomnia Medications Prescribed in the 60 Days After Buprenorphine Initiation in the Study Sample With OUD and Insomnia

| . | Total sample, n = 9510 (%) . | Females, n = 4637 (%) . | Males, n = 4873 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine | 6569 (69.1) | 3385 (73.0) | 3184 (65.3) |

| Short Acting | 5178 (54.5) | 2745 (59.2) | 2433 (49.9) |

| Long Acting | 4807 (50.6) | 2505 (54.0) | 2302 (47.2) |

| Z-drug | 3891 (40.9) | 2028 (43.7) | 1863 (38.2) |

| Non-Benzo/Z-drug | 8441 (88.8) | 4239 (91.4) | 4202 (86.2) |

| SSRI | 5271 (55.4) | 2842 (61.3) | 2429 (49.9) |

| Trazodone | 4815 (50.6) | 2496 (53.8) | 2319 (47.6) |

| Mirtazapine | 1822 (19.2) | 911 (19.7) | 911 (18.7) |

| Gabapentin | 4867 (51.2) | 2509 (54.1) | 2358 (48.4) |

| Quetiapine | 3069 (32.3) | 1534 (33.1) | 1535 (31.5) |

| Hydroxyzine | 4072 (42.8) | 2247 (48.5) | 1825 (37.5) |

| . | Total sample, n = 9510 (%) . | Females, n = 4637 (%) . | Males, n = 4873 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine | 6569 (69.1) | 3385 (73.0) | 3184 (65.3) |

| Short Acting | 5178 (54.5) | 2745 (59.2) | 2433 (49.9) |

| Long Acting | 4807 (50.6) | 2505 (54.0) | 2302 (47.2) |

| Z-drug | 3891 (40.9) | 2028 (43.7) | 1863 (38.2) |

| Non-Benzo/Z-drug | 8441 (88.8) | 4239 (91.4) | 4202 (86.2) |

| SSRI | 5271 (55.4) | 2842 (61.3) | 2429 (49.9) |

| Trazodone | 4815 (50.6) | 2496 (53.8) | 2319 (47.6) |

| Mirtazapine | 1822 (19.2) | 911 (19.7) | 911 (18.7) |

| Gabapentin | 4867 (51.2) | 2509 (54.1) | 2358 (48.4) |

| Quetiapine | 3069 (32.3) | 1534 (33.1) | 1535 (31.5) |

| Hydroxyzine | 4072 (42.8) | 2247 (48.5) | 1825 (37.5) |

Benzodiazepine, Z-Drug, or Other Insomnia Medications Prescribed in the 60 Days After Buprenorphine Initiation in the Study Sample With OUD and Insomnia

| . | Total sample, n = 9510 (%) . | Females, n = 4637 (%) . | Males, n = 4873 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine | 6569 (69.1) | 3385 (73.0) | 3184 (65.3) |

| Short Acting | 5178 (54.5) | 2745 (59.2) | 2433 (49.9) |

| Long Acting | 4807 (50.6) | 2505 (54.0) | 2302 (47.2) |

| Z-drug | 3891 (40.9) | 2028 (43.7) | 1863 (38.2) |

| Non-Benzo/Z-drug | 8441 (88.8) | 4239 (91.4) | 4202 (86.2) |

| SSRI | 5271 (55.4) | 2842 (61.3) | 2429 (49.9) |

| Trazodone | 4815 (50.6) | 2496 (53.8) | 2319 (47.6) |

| Mirtazapine | 1822 (19.2) | 911 (19.7) | 911 (18.7) |

| Gabapentin | 4867 (51.2) | 2509 (54.1) | 2358 (48.4) |

| Quetiapine | 3069 (32.3) | 1534 (33.1) | 1535 (31.5) |

| Hydroxyzine | 4072 (42.8) | 2247 (48.5) | 1825 (37.5) |

| . | Total sample, n = 9510 (%) . | Females, n = 4637 (%) . | Males, n = 4873 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine | 6569 (69.1) | 3385 (73.0) | 3184 (65.3) |

| Short Acting | 5178 (54.5) | 2745 (59.2) | 2433 (49.9) |

| Long Acting | 4807 (50.6) | 2505 (54.0) | 2302 (47.2) |

| Z-drug | 3891 (40.9) | 2028 (43.7) | 1863 (38.2) |

| Non-Benzo/Z-drug | 8441 (88.8) | 4239 (91.4) | 4202 (86.2) |

| SSRI | 5271 (55.4) | 2842 (61.3) | 2429 (49.9) |

| Trazodone | 4815 (50.6) | 2496 (53.8) | 2319 (47.6) |

| Mirtazapine | 1822 (19.2) | 911 (19.7) | 911 (18.7) |

| Gabapentin | 4867 (51.2) | 2509 (54.1) | 2358 (48.4) |

| Quetiapine | 3069 (32.3) | 1534 (33.1) | 1535 (31.5) |

| Hydroxyzine | 4072 (42.8) | 2247 (48.5) | 1825 (37.5) |

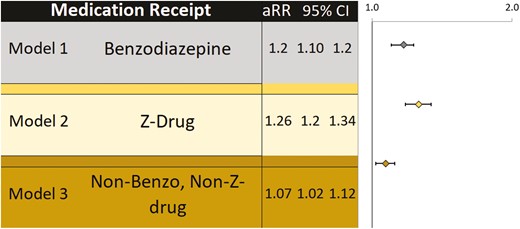

Association of sex with insomnia medication prescription receipt

Figure 2 depicts the results of multivariable Poisson regression models, which evaluated the association between sex and receipt of prescriptions for benzodiazepine, Z-drugs, and other insomnia medications after buprenorphine initiation while controlling for age, Medicaid status, and cooccurring psychiatric, substance use, and medical disorders. Female sex was associated with a slightly higher likelihood of prescription receipt for all three medication categories: benzodiazepines (RR = 1.17 [1.11–1.23]), Z-drugs (RR = 1.26 [1.18–1.34]), and others (RR = 1.07, [1.02–1.12]). Full models are shown in Supplementary Table 2. For Medicaid enrollees, this predominance for female over male prescribing persisted in analyses within non-Hispanic Black (females 55%, males 40%) and White (females 75%, males 61%) disaggregated groups when examining presence of insomnia medication prescription receipt at the buprenorphine treatment episode level (data not shown).

Sex and its association with benzodiazepine, Z-drug, and other insomnia Medication Prescription Receipt in People with Opioid Use Disorder and Comorbid Insomnia. Each model depicts the association of female sex (vs. male sex) with prescription receipt among individuals with OUD and comorbid insomnia. Models are adjusted for age, Medicaid versus commercial insurance, and cooccurring diagnoses (mood disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol use disorder, stimulant use disorder, sedative use disorder, chronic pain, diabetes, epilepsy, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and migraine).

Discussion

In a national cohort of individuals with insomnia and OUD initiating buprenorphine, we found high rates of prescriptions provided for medications commonly used for insomnia during the first 60 days of buprenorphine treatment. In particular, female patients were more likely to be initiated on benzodiazepine, Z-drug, and other insomnia medications in comparison to male peers. The FDA has a boxed warning about prescribing benzodiazepines with opioids given increased risk of harm, including fatal overdose [21–24]. Despite this, our data suggest that benzodiazepines are frequently prescribed in patients with comorbid OUD and insomnia. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing prescription receipt patterns of medications commonly used for insomnia in individuals receiving OUD treatment with buprenorphine.

Bertisch et al., in their study examining use patterns of medications commonly used for insomnia in the general US population, Z-drugs were the most prescribed class (1.23% of study population), followed by trazodone (0.97%), and benzodiazepines (0.40%) [25]. The patterns of prescriptions provided found in our study may differ from the general population for several reasons. Our study specifically looked at individuals with OUD receiving buprenorphine, who have higher rates of sleep disturbance than the general population, possibly increased severity of insomnia, and higher rates of comorbid conditions that may also affect sleep. Therefore, it is unsurprising that our study showed higher prevalence of insomnia medication prescriptions overall. Interestingly, however, the rate of diagnosed insomnia was lower in our study than in other sleep studies in this population likely due to differences in outcome definitions (i.e. ICD10 coding vs. patient-reported measures) [10]. Patients with OUD receiving buprenorphine who take benzodiazepines for insomnia have reported higher self-reported sleep duration despite lack of objectively measured improvement [26]. Others have posited that benzodiazepines may be more frequently prescribed to improve OUD treatment retention and reduce benzodiazepine misuse [22, 27, 28]. While OUD treatment retention may be improved with benzodiazepine use, overall mortality risk is increased with concurrent use of benzodiazepines [28]. More research is needed to inform how both clinicians and researchers should balance the risks and benefits associated with benzodiazepine receipt in the development of insomnia clinical guidelines and future investigations of the OUD insomnia comorbidity among patients receiving buprenorphine [22].

Findings of differences between male and female patients in the prescription of medications used for insomnia are likely being driven by a combination of sex- (biological variable) and gender- (continuum of sociocultural construct) related factors, as seen in other chronic medical conditions [29]. First, the findings are consistent with previous reports highlighting how women are more often prescribed medications for treatment of insomnia than men [25, 30]. Bertisch et al., reported women had higher likelihood (aOR = 1.32) of receiving insomnia prescriptions, which was slightly more robust than our findings [25]. Another contributing factor to this finding may be gender biases and stereotypes, with benzodiazepine use in women being normalized, in contrast, to use in men being more often recognized as problematic when used for similar reasons as women [31]. Additionally, sex-related differences in mood and anxiety disorders, with females exhibiting higher prevalence of both compared to male counterparts, likely contributed to our findings of higher rates of prescriptions across all insomnia medication categories in female compared to male patients [5, 32–35]. However, in our sample, female sex was associated with slightly higher odds of receiving prescriptions for benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and other medications even after sex differences in mood, anxiety, and other disorders were considered. While we consider this finding exploratory, nonetheless, the higher impact of benzodiazepine prescription provision among female than male patients with OUD warrants further research, especially given benzodiazepines’ risks for overdose among patients receiving buprenorphine [15]. This is particularly important as literature suggests that women with substance use disorders may be more likely than men to misuse benzodiazepines and that women are also twice as likely to have a benzodiazepine prescription as their source of first misuse [34]. Additional studies need to be conducted to better understand underlying socioecological factors contributing to these sex disparities as well as develop sex and gender-informed psychopharmacological [36] interventions for individuals with comorbid OUD and insomnia targeting these disparities.

The study had several limitations. First, the databases utilized for the analyses did not link indications for medication prescription, so some medication prescriptions may have been for treatment of non-sleep disorders. We addressed this limitation inherent to the data source by restricting the study sample to only the subsample of individuals with a clinician-provided insomnia diagnosis. Nonetheless, this limitation may have introduced misclassification bias to analyses. Furthermore, while the study was able to capture prescription and medication fill patterns, it does not necessarily translate to medication use patterns, and our findings may not accurately represent rates of insomnia medication use. We were also unable to capture race and ethnicity variables for the entire sample as this data was limited in the commercial insurance claims. Additionally, the sample with available race and ethnicity variables identified as predominantly non-Hispanic White. These limitations restrict the generalizability of findings for communities of color who experience disparities in both OUD and sleep health outcomes [37, 38], highlighting the importance of future investigations focused on these communities and that incorporate rigorous assessments of the impacts of structural racism. Similarly, gender identity was not reported, which excluded our ability to assess gender minorities among this highly vulnerable population [39]. Overall, it is critical for future OUD-insomnia studies to incorporate multi-level frameworks [40], to ensure investigations are intentional in identifying the roles that factors across individual to socioecological levels play in disparities [41, 42] and treatment responses [18, 43] related to both OUD and sleep. Next, these findings may not be representative of the current state of opioid and benzodiazepine use as the data is from prior to 2016, and synthetic opioid use has surged since, while benzodiazepine prescribing has overall declined [44, 45]. This study may not be generalizable to any individual receiving MOUD as it did not analyze individuals in methadone treatment, which may pose higher risk for overdose when co-prescribing benzodiazepines or Z-drugs. Additionally, MarketScan data only includes insured people in the United States with a minimum of 6 months of continuous insurance coverage, which is used as a standard time frame for covariate assessment. This limits the study’s generalizability, as many patients with addiction (including those who are uninsured and incarcerated) would not be included in the dataset. Lastly, the increased RRs for medication prescription receipt associated with female sex are of relatively low magnitude, and we cannot rule out the possibility of unmeasured confounding given the observational design of the study.

Despite these limitations, the study had several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report prevalence of prescriptions for different medications commonly used for insomnia in patients with OUD initiating buprenorphine using national data. Additionally, this is the first study to examine sex-related differences in prescribing patterns, while accounting for differences in prevalence of comorbid disorders, with the goal of better addressing sex- and gender-informed treatments for people with OUD and insomnia. Ultimately, further investigation is required on the efficacy of different medications for insomnia treatment in men and women with OUD to guide clinical practice.

Conclusion

In a national sample of individuals receiving buprenorphine for OUD with a comorbid insomnia diagnosis, we observed a high number of people receiving medications commonly used to treat insomnia symptoms. Female sex was associated with a slightly increased likelihood of prescription receipt for benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and non-sedative/hypnotic insomnia medications, after controlling for differences in psychiatric comorbidities between female and male patients. The field of medication development targeting insomnia among individuals with OUD is underdeveloped, leaving researchers and clinicians without efficacy data for common insomnia treatments among the growing population of people receiving buprenorphine. As this evidence base regarding insomnia therapeutics in the OUD treatment setting progresses, investigations should prioritize utilizing sex-disaggregated data and socioecological frameworks to investigate how intersecting identities impact outcomes; doing so ultimately can lead to proper elucidate sex-related variations in OUD treatments and guide equitable development of targeted interventions in the ongoing overdose crisis.

Funding

This project was funded by R21 DA044744 (Richard Grucza/Laura Bierut). Effort for some personnel was supported by grants T32 DA015035 (Kevin Xu, PI: Kathleen Bucholz, Jeremy Goldbach), R25 MH11247301 (K Xu, H Patel, PI: Nuri Farber/Ginger Nicol), K23 DA053507 (Caitlin Martin), UL1 TR002649 (F Gerard Moeller), St. Louis University Research Institute Fellowship (R Grucza), and UG1 DA050207 (F Gerard Moeller), but these grants did not fund the analyses of the Merative™ MarketScan data performed by Dr. Xu. In addition, we acknowledge Matt Keller MS, John Sahrmann MS, Dustin Stwalley MA, and the Center for Administrative Data Research (CADR) at Washington University for assistance with data acquisition, management, and storage. CADR is supported in part by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences via grant UL1 TR002345 (from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health).

Disclosure Statement

LJB is listed as an inventor on US Patent 8080371, “Markers for Addiction,” covering use of SNPs in determining the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of addiction. JMD was a consultant for Eisai prior to this study’s initiation, and all consulting duties are unrelated to this study. All other authors declare no financial interests. All authors do not have any financial or nonfinancial relationships with organizations that may have an interest in our submitted work. Preprint Repositories: None.

Author Contributions

Concept: Martin, Xu, Moeller, Dzierewski. Design: Martin, Xu, Grucza, Bierut. Analysis of data: Xu. Interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of manuscript: Martin, Patel, Xu. Obtained funding: Grucza, Bierut

Administrative, technical, or material support: Grucza, Bierut. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Dr. Kevin Xu was the only individual who had access to the data and the only one to perform analyses. All of the other authors, including Dr. Martin, did not have access to the data, although contributed to the interpretation of data.

Ethical Approval

Not required.

Data Availability

No additional data are available. We intend to provide relevant code on written reasonable request.

Dissemination Declaration

Dissemination to study participants and or patient organizations is not possible or applicable due to the de-identified nature of our data.

Transparency Declaration

The manuscript’s guarantors affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported. We affirm that no important aspects of the study have been omitted. We affirm that any discrepancies from the study as planned and registered have been explained.

Patient and Public Involvement Statement

This research was done without direct patient involvement.

Comments