-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lin Shen, Joshua F Wiley, Bei Bei, Perceived daily sleep need and sleep debt in adolescents: associations with daily affect over school and vacation periods, Sleep, Volume 44, Issue 12, December 2021, zsab190, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab190

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To describe trajectories of daily perceived sleep need and sleep debt, and examine if cumulative perceived sleep debt predicts next-day affect.

Daily sleep and affect were measured over two school weeks and two vacation weeks (N = 205, 54.1% females, M ± SDage = 16.9 ± 0.87 years). Each day, participants wore actigraphs and self-reported the amount of sleep needed to function well the next day (i.e. perceived sleep need), sleep duration, and high- and low-arousal positive and negative affect (PA, NA). Cumulative perceived sleep debt was calculated as the weighted average of the difference between perceived sleep need and sleep duration over the past 3 days. Cross-lagged, multilevel models were used to test cumulative sleep debt as a predictor of next-day affect. Lagged affect, day of the week, study day, and sociodemographics were controlled.

Perceived sleep need was lower early in the school week, before increasing in the second half of the week. Adolescents accumulated perceived sleep debt across school days and reduced it during weekends. On weekends and vacations, adolescents self-reported meeting their sleep need, sleeping the amount, or more than the amount of sleep they perceived as needing. Higher cumulative actigraphy sleep debt predicted higher next-day high arousal NA; higher cumulative diary sleep debt predicted higher NA (regardless of arousal), and lower low arousal PA the following day.

Adolescents experienced sustained, cumulative perceived sleep debt across school days. Weekends and vacations appeared to be opportunities for reducing sleep debt. Trajectories of sleep debt during vacation suggested recovery from school-related sleep restriction. Cumulative sleep debt was related to affect on a daily basis, highlighting the value of this measure for future research and interventions.

In a large, community sample of adolescents, this study examined trajectories of daily perceived sleep need and cumulative sleep debt, and their associations with daily affect during school terms and vacations. Strengths include an intensive longitudinal design, both actigraphy and self-report measures of sleep, and a novel measure of cumulative sleep debt. Findings showed that adolescents experienced cumulative sleep debt during school days. Weekends and vacations served as opportunities to reduce sleep debt. Higher cumulative sleep debt was linked to worse mood on a daily basis. Cumulative sleep debt and perceived sleep need require future research as they may serve as a therapeutic target in adolescent sleep interventions.

Introduction

On school nights, most adolescents obtain insufficient sleep [1]. Consecutive nights of sleep restriction could result in an accumulation of sleep “debt” across the school week [2, 3]. Sleep restriction is well-documented to negatively impact adolescents’ mood and affect [4, 5]. Critically, chronic sleep restriction over school terms coincides with adolescence as a developmental stage that is characterized by elevated emotional arousal and reactivity [6, 7], and high prevalence of mood disorders that predict poorer lifelong outcomes [8]. However, current understanding of the amount of sleep adolescents perceive themselves needing on a daily basis to function well the next day (perceived sleep need), and the accumulation of perceived sleep debt (i.e. the difference between perceived sleep need and actual sleep duration) on a day-to-day basis is limited. Further, the impact of consecutive days and weeks of sleep restriction on adolescents’ affect is not well understood.

Constrained versus unconstrained sleep opportunities: accumulating and “paying off” sleep debt

Sleep restriction on school nights occurs due to a mismatch between early school start times, and biological and psychosocial factors encouraging later bed- and wake-times across adolescence [1, 9]. Sleep debt refers to sustained sleep restriction over multiple consecutive days, with inadequate opportunity for recovery sleep or sleep extension [10]. Adolescents are likely to accumulate sleep debt across the school week as early school start times repeatedly restrict sleep opportunities [11]. In comparison, when sleep opportunities on weekends and vacations are relatively unconstrained, sleep and wake times are later [12], and sleep duration is significantly longer [13]. However, two consecutive nights of unconstrained sleep opportunities over the weekend may not be sufficient to pay off the accumulated sleep debt. An experimental study reported that three consecutive days of unconstrained sleep opportunities were insufficient for young adults to fully recover from naturalistic sleep debt [14]. Given that adolescents experience consecutive weeks of restricted sleep each school term (e.g. 10–12 weeks per school term in Australia), it is possible that adolescents accumulate sleep debt each school week, and two weekend nights of “catchup sleep” are insufficient to fully recover from the accumulated sleep debt.

Longer periods of unconstrained sleep opportunities are necessary to understand adolescents’ recovery from cumulative sleep debt but are rarely studied. In one of the first studies that examined adolescents’ daily sleep using actigraphy over a 2-week vacation, we found that during the first few days of school-to-vacation transition, total sleep time (TST) dramatically increased [15] in a similar manner as weekends [16]. However, it subsequently decreased and then plateaued from the second half of the first vacation week; further, sleep onset latency (i.e. time taken to fall asleep) progressively increased while sleep efficiency decreased, both plateauing during the second vacation week [15]. These trajectories suggest that recovery from school-related sleep restriction was taking place and that adolescents were likely to have recovered from school-related sleep debt toward the later part of a 2-week vacation. This, however, cannot be confirmed as no daily measures of sleep-related functional outcomes were measured.

Daily perceived sleep need and debt in naturalistic settings

Current understanding of sleep debt is largely based on experimental studies in young adults, investigating the difference between individuals’ habitual sleep duration (e.g., 2 weeks at baseline), and sleep duration obtained in laboratory under extended sleep opportunities (e.g. 16 h of sleep opportunity [12 h at night-time, 4 h at midday]) [14]. Longer sleep duration under extended sleep opportunities suggests individuals’ habitual sleep duration was not meeting their sleep need, and therefore indicates the presence of sleep debt. In adolescents, sleep need estimated using dose-response modeling under experimental settings was approximately 9 h [3]. This is longer than the habitual sleep duration which most adolescents obtain in Australia, Europe, and United States [16], indicating a substantial sleep debt in this age group. Quantifying sleep need using experimental paradigms, however, may not capture subjective experience of sleep debt in relation to functioning in adolescents’ everyday life.

In this manuscript, the term “perceived sleep debt” is used to describe the deviation between individuals’ perception of sleep need and actual sleep duration. A small number of studies in young adults measured perception of sleep need cross-sectionally, examining the deviation between individuals’ perception of how much sleep they need to function optimally and actual sleep duration. In university students averaging 6.7 h of sleep, participants reported a subjectively perceived sleep debt of 1.36 h [17].

In adolescents, participants in the National Sleep Foundation’s 2006 survey reported requiring 8.2 h of sleep [18]. More recently, in 196 adolescent athletes, most reported requiring over 9 h of sleep to “feel their best” (calculated as ideal waketime minus bedtime) [19]. These studies, however, measured perceived sleep need at a single timepoint, and did not consider day-to-day changes in perception of sleep need that may occur in the context of changing daily activities and demands. This may be particularly relevant for adolescents. For example, adolescents have been shown to delay bedtime to study, which comes at the expense of sleep [20]. This suggests that adolescents’ perception of how much sleep they need, may change from day to day, depending on events occurring on a given day, or in expectation of events occurring the next day. Further, sleep debt on a given day also may be influenced by previous days’ sleep debt, especially relevant for adolescents, who regularly experience constrained sleep opportunities.

Impact of sleep debt on affect

A large body of literature shows that chronic, partial sleep deprivation is linked to dampened positive affect (PA) and elevated negative affect (NA) in adolescents [4, 21]. Studies also suggest differential associations between sleep with positive and negative affect: longer sleep duration may be more strongly linked to higher PA, and better sleep quality may be more strongly linked to lower NA [5]. Experimental studies using sleep restriction protocols demonstrate the causal impacts of sleep loss on positive and negative affect [22, 23]. However, the cumulative impact of repeated nights and cycles of sleep restriction on adolescents’ daily affect, much like what they experience naturalistically, has not been well studied. A recent study investigated the impact of successive nights of sleep restriction on adolescents’ affect and neurobehavioral measures [24]. Simulating naturalistic constrained and unconstrained sleep opportunities, sleep restriction over five consecutive days (5-hour time in bed [TIB]) reduced adolescents’ PA, but did not increase NA. Further, affect levels were not restored by catch-up sleep over two consecutive days (9-hour TIB). Repeated exposure to the second round of sleep restriction (5-hour TIB over three nights) increased the rate at which PA decreased [24]. The cumulative impact of repeated sleep debt on adolescents’ affect has yet to be examined in naturalistic settings.

Current study

The current study aims to: (1) describe trajectories of daily perceived sleep need and sleep debt across 28 consecutive days, and (2) examine how perceived daily sleep debt predicts next-day affect in adolescents.

To address the lack of studies examining longer periods of unconstrained sleep opportunity beyond two weekend nights, sleep and affect data were collected across 2 weeks of naturally occurring constrained sleep opportunities (school term), and the subsequent 2-week unconstrained sleep opportunities (vacation). Affect was measured daily in the context of participants’ lives, using ecological momentary assessment, which maximizes ecological validity and minimizes recall bias [25].

Methods

Participants

Adolescents in Years 10, 11, and 12 of high schools in Victoria, Australia, attending the final 2 weeks of a school term, did not travel across time zones during the study, and regularly used a smartphone with internet connection were eligible for the study. There were no exclusion criteria to maximize generalizability. Assuming 75% completion rate and moderate to large intraclass coefficients (0.3–0.5), a sample of 204 participants would provide 80% power to detect a small effect size (Cohen’s f2 = .02).

Design and procedures

Reporting follows the STROBE [26] for observational and CREMAS [27] for ecological momentary assessment study guidelines. Data were collected between November 2017 and July 2019. The study spanned 28 days: the last 2 weeks of a school term, and the subsequent 2-week vacation. Adolescents were recruited through online advertisements, in-person recruitment, and posters in public areas (e.g. train stations, shopping malls). Informed consent was obtained from both participants and their parents or guardians.

Prior to study entry, participants attended a 60-minute information session, during which they were familiarized with study procedures and equipment. Demographic information was collected at baseline, before commencing daily measures. Throughout the study, a wrist-worn actigraphy device was used to estimate sleep-wake patterns, and sleep was self-reported each morning (07:00–14:30). Affect and perceived sleep need were self-reported each afternoon (15:30–19:00). Surveys were administered through a smartphone application (MetricWire Inc.), and times were set outside of typical school hours. As a token of appreciation, participants received up to $76 AUD cash, based on the number of daily surveys completed, with bonuses for weeks with complete entries. Study procedures were approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (#10005).

Equipment and measures

Sleep duration.

Objective sleep-wake patterns were estimated via wrist-worn actigraphy, using various models of the Mini Mitter Actiwatches (-L, -64, -2, Spectrum, Pro, and Plus) with comparable sleep statistics [28]. Each participant used the same actigraph device throughout the whole study period. Data were collected at 1-minute epochs and analyzed on the “medium” threshold for sleep-wake detection in Actiware 6.0.9. Participants self-reported sleep using the adapted Consensus Sleep Diary [29] to derive TST.

Perceived sleep need.

Participants self-reported overall perceived sleep need at study entry, as well as daily throughout the study. At study entry, participants reported the optimal amount of sleep they perceived needing on weekdays, and separately, on weekends/vacations. Across the study, perceived sleep need was measured daily using the question “How much sleep do you need tonight to function well tomorrow? This may be different from the actual amount of sleep you may get.” The consideration of functioning in relation to next-day daytime activities may be especially important given the study spans school term and vacation. Perceived sleep need measured daily, was used in the calculations of cumulative sleep debt.

Cumulative, perceived sleep debt.

Daily differences between TST and perceived sleep need over the previous 3 days were weighted to form a cumulative measure of sleep debt for each day. Positive values indicate the presence of sleep debt (i.e. sleeping less than perceived sleep need), and negative values indicate sleeping more than the perceived sleep need). See Statistical Analyses section for details.

Affect.

Affect was assessed using 12 items selected from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded (PANAS-X) [30]. These items chosen had low cross-loadings with other factors, and captured both high- and low- arousal affect: high arousal PA (Cheerful, Enthusiastic, Happy), low arousal PA (At Ease, Calm, Relaxed), high arousal NA (Afraid, Irritable, Nervous), and low arousal NA (Guilty, Lonely, Sad). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (Very slightly or not at all) to 4 (Extremely) based on how participants felt at the time of the survey. High- and low-arousal PA and NA were derived by averaging individual items (possible range: 0 to 4). Affect dimensions showed low to adequate reliability within individuals: high arousal NA (ω between = 0.84, ω within = 0.44), low arousal NA (ω between = 0.88, ω within = 0.59), high arousal PA (ω between = 0.97, ω within = 0.79), low arousal PA (ω between = 0.98, ω within = 0.79).

Statistical analyses

First, the difference between perceived sleep need and actual TST, both winsorized at the top and bottom 1%, was calculated for each day (separately for actigraphy and sleep diary measures). We then used an exponential decay function, , where α = 0.5 and t is the number of lag days (0 for current, 1 for yesterday, etc.) to generate, for each day, a weighted sleep debt that captures the difference between perceived sleep need and TST for the day in question, as well as days prior. Cumulative sleep debt for a given day was not calculated if the current day sleep debt was missing. Given the lack of literature on how daily sleep debt may accumulate in naturalistic settings, we took an empirical approach and compared models that took sleep debt over the previous 1 to 7 days into account. In each model, sleep debt was tested as predictors of PA and NA. Balancing Akaike Information Criterion, Bayesian Information Criterion, and missing data (refer to Supplementary Figure S1), the model which took into account the previous 3 days was chosen.

To examine the impact of cumulative sleep debt on daily affect, cross-lagged multilevel models were conducted through R v.3.6.3 [31] using lme4 v1.1-23 (to estimate models) [32] and lmerTest v3.1-2 (to estimate degrees of freedom and p-values) [33]. Models were tested at alpha of .05 and estimated using restricted maximum likelihood [34]. All available data were utilized, with the number of daily observations ranging from 3,152 to 3,399 across models due to missing data and cross lags.

Cumulative sleep debt was entered as a predictor of next-day affect. Unadjusted models controlled for previous-day affect for a stronger test of directionality; fully adjusted models controlled for previous-day affect, as well as the following covariates: school year level (10, 11, 12), sex (0 = Male, 1 = Female), body mass index (BMI; calculated from self-reported height and weight), Non-white (No = 0; Yes = 1), born in Australia (No = 0, Yes = 1), adolescents’ work status (Not working = 0, Working part-time or casual = 1), parental marital status (married or de facto = 0, other = 1), study day, and day of week.

To examine whether associations between cumulative sleep debt and affect differed between school and vacation periods, school/vacation status was added as a moderator of this association. The nonsignificant interaction term between school/vacation status and sleep debt was dropped, and school/vacation was left as a covariate, with its main effect on affect tested.

Sleep debt (actigraphy, sleep diary), and affect (separated by arousal and valence) measures were tested in separate models, where the intercept, the lagged outcome covariate, and the within-person predictor were included as random effects, and other covariates were included as fixed effects. Marginal and conditional R2 values were calculated for each model, representing the proportion of total variance explained by fixed effects, and the proportion of total variance explained by fixed and random effects, respectively [35]. Nested models were run, dropping predictors one by one. The corresponding changes in marginal and conditional R2 from each predictor were used to calculate a Cohen’s f2 type effect size: , where is the marginal R2 from the full model, and is the marginal R2 from the restricted model (i.e. after dropping the focal predictor).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Two hundred five adolescents (54.1% females, age M ± SD = 16.92 ± 0.87 years) completed the study, providing 4,868 (M ± SD = 24.4 ± 7.9 days/person) and 5,231 (M ± SD = 26.2 ± 5.4 days/person) nights of usable actigraphy-assessed and self-reported sleep data respectively. Most missing data on actigraphy-assessed sleep were from faulty hardware. Completion rates for morning and afternoon surveys were high (93.4% and 80.8% respectively).

Sociodemographic information is presented in Table 1. Most participants were born in Australia (66.3%) and were Asian (55.6%) or European (35.6%). A small percentage of participants self-reported current depressive (4.39%), anxiety (5.85%), or sleep (11.2%) disorders. Sensitivity analyses revealed minimal changes in results after excluding participants with current depressive/anxiety disorders, and/or sleep disorders (≤0.01 change for coefficients and confidence intervals). Therefore, these participants were not excluded from analyses to maintain the representativeness of a community sample.

| Participant Characteristic . | M (SD)/N % . |

|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 16.92 (0.87) |

| Female, N (%) | 111 (54.1) |

| Body Mass Index, M (SD) | 21.90 (4.42) |

| School Year, N (%) | |

| Year 10 | 51 (24.9) |

| Year 11 | 82 (40.0) |

| Year 12 | 72 (35.1) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |

| European | 73 (35.6) |

| North-East Asian | 37 (18.0) |

| Southern Asian | 36 (17.6) |

| South-East Asian | 24 (11.7) |

| Mixed Asian | 17 (8.3) |

| Others | 18 (8.8) |

| Born in Australia, N (%) | 136 (66.3) |

| Working Part-time/ Casual, N (%) | 69 (33.7) |

| Parents Married/ De Facto, N (%) | 164 (80.0) |

| Participating in Extra-Curricular Activities, N (%) | 134 (65.4) |

| Current Depressive Disorder, N (%) | 9 (4.39) |

| Current Anxiety Disorder, N (%) | 12 (5.85) |

| Current Sleep Disorders, N (%) | 23 (11.2%) |

| Days during vacation when sleep is affected by commitments, N (%) | 6.13 (2.99) |

| Participant Characteristic . | M (SD)/N % . |

|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 16.92 (0.87) |

| Female, N (%) | 111 (54.1) |

| Body Mass Index, M (SD) | 21.90 (4.42) |

| School Year, N (%) | |

| Year 10 | 51 (24.9) |

| Year 11 | 82 (40.0) |

| Year 12 | 72 (35.1) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |

| European | 73 (35.6) |

| North-East Asian | 37 (18.0) |

| Southern Asian | 36 (17.6) |

| South-East Asian | 24 (11.7) |

| Mixed Asian | 17 (8.3) |

| Others | 18 (8.8) |

| Born in Australia, N (%) | 136 (66.3) |

| Working Part-time/ Casual, N (%) | 69 (33.7) |

| Parents Married/ De Facto, N (%) | 164 (80.0) |

| Participating in Extra-Curricular Activities, N (%) | 134 (65.4) |

| Current Depressive Disorder, N (%) | 9 (4.39) |

| Current Anxiety Disorder, N (%) | 12 (5.85) |

| Current Sleep Disorders, N (%) | 23 (11.2%) |

| Days during vacation when sleep is affected by commitments, N (%) | 6.13 (2.99) |

| Participant Characteristic . | M (SD)/N % . |

|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 16.92 (0.87) |

| Female, N (%) | 111 (54.1) |

| Body Mass Index, M (SD) | 21.90 (4.42) |

| School Year, N (%) | |

| Year 10 | 51 (24.9) |

| Year 11 | 82 (40.0) |

| Year 12 | 72 (35.1) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |

| European | 73 (35.6) |

| North-East Asian | 37 (18.0) |

| Southern Asian | 36 (17.6) |

| South-East Asian | 24 (11.7) |

| Mixed Asian | 17 (8.3) |

| Others | 18 (8.8) |

| Born in Australia, N (%) | 136 (66.3) |

| Working Part-time/ Casual, N (%) | 69 (33.7) |

| Parents Married/ De Facto, N (%) | 164 (80.0) |

| Participating in Extra-Curricular Activities, N (%) | 134 (65.4) |

| Current Depressive Disorder, N (%) | 9 (4.39) |

| Current Anxiety Disorder, N (%) | 12 (5.85) |

| Current Sleep Disorders, N (%) | 23 (11.2%) |

| Days during vacation when sleep is affected by commitments, N (%) | 6.13 (2.99) |

| Participant Characteristic . | M (SD)/N % . |

|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 16.92 (0.87) |

| Female, N (%) | 111 (54.1) |

| Body Mass Index, M (SD) | 21.90 (4.42) |

| School Year, N (%) | |

| Year 10 | 51 (24.9) |

| Year 11 | 82 (40.0) |

| Year 12 | 72 (35.1) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |

| European | 73 (35.6) |

| North-East Asian | 37 (18.0) |

| Southern Asian | 36 (17.6) |

| South-East Asian | 24 (11.7) |

| Mixed Asian | 17 (8.3) |

| Others | 18 (8.8) |

| Born in Australia, N (%) | 136 (66.3) |

| Working Part-time/ Casual, N (%) | 69 (33.7) |

| Parents Married/ De Facto, N (%) | 164 (80.0) |

| Participating in Extra-Curricular Activities, N (%) | 134 (65.4) |

| Current Depressive Disorder, N (%) | 9 (4.39) |

| Current Anxiety Disorder, N (%) | 12 (5.85) |

| Current Sleep Disorders, N (%) | 23 (11.2%) |

| Days during vacation when sleep is affected by commitments, N (%) | 6.13 (2.99) |

Descriptive statistics for sleep and affect variables are in Table 2. The average of participants’ daily perceived sleep need across the study was 7.92 h (SD = 1.06). Average TST were 6.84 and 7.85 h for actigraphy and self-report, respectively. The average cumulative sleep debt over the study period were 1.08 and 0.07 h for actigraphy and self-report, respectively.

| . | M (SD) . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study variables . | Entire study period . | School term . | Vacation . |

| Affect | |||

| High arousal negative affect | 1.55 (0.67) | 1.56 (0.66) | 1.53 (0.68) |

| Low arousal negative affect | 1.44 (0.67) | 1.42 (0.63) | 1.46 (0.70) |

| High arousal positive affect | 2.56 (1.01) | 2.55 (0.98) | 2.56 (1.02) |

| Low arousal positive affect | 2.97 (1.04) | 2.94 (1.03) | 3.00 (1.05) |

| Actigraphy-assessed sleep | |||

| Total sleep time (hours) | 6.84 (1.30) | 6.53 (1.21) | 7.09 (1.32) |

| Cumulative sleep debt (hours) | 1.08 (1.25) | 1.28 (1.13) | 0.91 (1.32) |

| Self-reported sleep | |||

| Total sleep time (hours) | 7.85 (1.50) | 7.49 (1.41) | 8.16 (1.51) |

| Cumulative sleep debt (hours) | 0.07 (1.28) | 0.33 (1.13) | −0.14 (1.35) |

| Daily perceived sleep need (hours) | 7.92 (1.06) | 7.81 (1.03) | 8.01 (1.07) |

| . | M (SD) . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study variables . | Entire study period . | School term . | Vacation . |

| Affect | |||

| High arousal negative affect | 1.55 (0.67) | 1.56 (0.66) | 1.53 (0.68) |

| Low arousal negative affect | 1.44 (0.67) | 1.42 (0.63) | 1.46 (0.70) |

| High arousal positive affect | 2.56 (1.01) | 2.55 (0.98) | 2.56 (1.02) |

| Low arousal positive affect | 2.97 (1.04) | 2.94 (1.03) | 3.00 (1.05) |

| Actigraphy-assessed sleep | |||

| Total sleep time (hours) | 6.84 (1.30) | 6.53 (1.21) | 7.09 (1.32) |

| Cumulative sleep debt (hours) | 1.08 (1.25) | 1.28 (1.13) | 0.91 (1.32) |

| Self-reported sleep | |||

| Total sleep time (hours) | 7.85 (1.50) | 7.49 (1.41) | 8.16 (1.51) |

| Cumulative sleep debt (hours) | 0.07 (1.28) | 0.33 (1.13) | −0.14 (1.35) |

| Daily perceived sleep need (hours) | 7.92 (1.06) | 7.81 (1.03) | 8.01 (1.07) |

Perceived sleep need, and actigraphy and self-reported total sleep time were winsorized at 1%.

| . | M (SD) . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study variables . | Entire study period . | School term . | Vacation . |

| Affect | |||

| High arousal negative affect | 1.55 (0.67) | 1.56 (0.66) | 1.53 (0.68) |

| Low arousal negative affect | 1.44 (0.67) | 1.42 (0.63) | 1.46 (0.70) |

| High arousal positive affect | 2.56 (1.01) | 2.55 (0.98) | 2.56 (1.02) |

| Low arousal positive affect | 2.97 (1.04) | 2.94 (1.03) | 3.00 (1.05) |

| Actigraphy-assessed sleep | |||

| Total sleep time (hours) | 6.84 (1.30) | 6.53 (1.21) | 7.09 (1.32) |

| Cumulative sleep debt (hours) | 1.08 (1.25) | 1.28 (1.13) | 0.91 (1.32) |

| Self-reported sleep | |||

| Total sleep time (hours) | 7.85 (1.50) | 7.49 (1.41) | 8.16 (1.51) |

| Cumulative sleep debt (hours) | 0.07 (1.28) | 0.33 (1.13) | −0.14 (1.35) |

| Daily perceived sleep need (hours) | 7.92 (1.06) | 7.81 (1.03) | 8.01 (1.07) |

| . | M (SD) . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study variables . | Entire study period . | School term . | Vacation . |

| Affect | |||

| High arousal negative affect | 1.55 (0.67) | 1.56 (0.66) | 1.53 (0.68) |

| Low arousal negative affect | 1.44 (0.67) | 1.42 (0.63) | 1.46 (0.70) |

| High arousal positive affect | 2.56 (1.01) | 2.55 (0.98) | 2.56 (1.02) |

| Low arousal positive affect | 2.97 (1.04) | 2.94 (1.03) | 3.00 (1.05) |

| Actigraphy-assessed sleep | |||

| Total sleep time (hours) | 6.84 (1.30) | 6.53 (1.21) | 7.09 (1.32) |

| Cumulative sleep debt (hours) | 1.08 (1.25) | 1.28 (1.13) | 0.91 (1.32) |

| Self-reported sleep | |||

| Total sleep time (hours) | 7.85 (1.50) | 7.49 (1.41) | 8.16 (1.51) |

| Cumulative sleep debt (hours) | 0.07 (1.28) | 0.33 (1.13) | −0.14 (1.35) |

| Daily perceived sleep need (hours) | 7.92 (1.06) | 7.81 (1.03) | 8.01 (1.07) |

Perceived sleep need, and actigraphy and self-reported total sleep time were winsorized at 1%.

On average, participants reported low levels of high- and low-arousal NA (1.55 and 1.44 points respectively), and moderate to high levels of high- and low-arousal PA (2.56 and 2.97 points respectively) across the study. The four affect dimensions were not significantly different during school terms versus vacations (Supplementary Table S1).

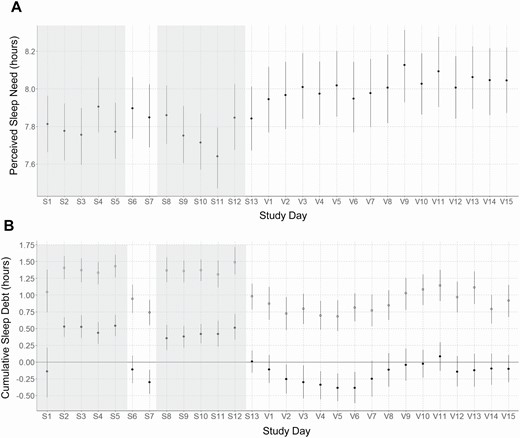

Perceived sleep need and cumulative sleep debt over school term and vacation

Figure 1 contains daily trajectories of perceived sleep need, and cumulative actigraphy and diary sleep debt. When surveyed at study entry, adolescents reported needing significantly more sleep during weekends/vacations (M ± SD = 8.35 ± 1.40 h) compared to weekdays (7.61 ± 1.08 h, p < .001). Similarly, when asked on a daily basis, adolescents’ average perceived sleep need was significantly lower during school terms (7.81 ± 1.03 h) compared to vacations (8.01 ± 1.07 h, p < .001). During the two school weeks, perceived sleep need was lower early in the week (S1–S3, S8–S11, in Figure 1A), before increasing in the second half of the week (S4–S7, S12–S13, in Figure 1A).

Means and 95% confidence intervals for daily perceived sleep need and cumulative sleep debt across the study. School terms are denoted by study days S1 to S13, and weekdays (Sunday night to Thursday night) are shaded in gray. Weekends (Friday and Saturday nights) are unshaded. Vacations are denoted by study days V1 to V15. (A) shows daily perceived sleep need across the study. (B) shows cumulative actigraphy sleep debt in open circles, and cumulative diary sleep debt in closed circles. Positive values indicate presence of sleep debt. Sleep debt of 0 indicates meeting perceived sleep need. Negative values indicate sleeping more than perceived sleep need.

Cumulative actigraphy sleep debt was higher than cumulative diary sleep debt, but trajectories were similar. During the two school weeks, cumulative sleep debt was stable on weekdays and decreased on the weekend (S6 and S7 in Figure 1B). This decrease likely reflects “catchup sleep” during two consecutive days of unconstrained sleep (Friday and Saturday nights). On these weekend nights, adolescents’ self-reported sleep duration met their perceived sleep need.

During the 2-week vacation with relatively unconstrained sleep opportunities, adolescents on average met perceived sleep need based on self-report but not actigraphy (see Figure 1B). Cumulative sleep debt over the vacation showed a polynomial trend: in the first vacation week, there was a progressive decrease in cumulative sleep debt, such that by V5 and V6, adolescents self-reported sleeping approximately 20 min more than their perceived sleep need. This direction reversed upon the start of the second vacation week, during which cumulative diary sleep debt fluctuated around 0, indicating that adolescents self-reported sleeping as much as their perceived need.

Impact of perceived sleep debt on next-day affect

School/vacation status did not significantly moderate the association between sleep debt and daily affect (all p-values > .077), therefore the interaction term was dropped and its main effect was included as a covariate in all models.

Adjusted, cross-lagged multilevel models with cumulative actigraphy and diary sleep debt predicting next-day affect are in Table 3 (refer to Supplementary Table S1 for full results of the adjusted model, including covariates). Based on actigraphy, higher cumulative sleep debt predicted higher next-day high arousal NA (b = 0.02, p = .038). This suggests that controlling for the effects of covariates and lagged outcomes, an hour increase in cumulative actigraphy sleep debt on a given day, was associated with a 0.02-point increase in high arousal NA the following day. The associations between actigraphy sleep debt and other domains of next-day affect were not statistically significant (p > .18), but showed a trend toward having a negative association with low arousal PA (p = .059).

| . | Negative affect . | . | Positive affect . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High arousal | Low arousal | High arousal | Low arousal | |

| Cumulative actigraphy sleep debt (adjusted for covariates; n = 190, # of observations = 3,152) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02* [0.00, 0.04], <0.01 | 0.01 [−0.01, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.02], <0.01 | −0.03† [−0.05, 0.00], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | — | — |

| Cumulative actigraphy sleep debt (not adjusted for covariates; n = 190, # of observations = 3,152) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02 [0.00, 0.03], <0.01† | 0.01 [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.03, 0.02], <0.01 | −0.03 [−0.05, 0.00], <0.01† |

| Within (random) | — | — | — | — |

| Cumulative diary sleep debt (adjusted for covariates; n = 199, # of observations = 3,399) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02** [0.01, 0.04], <0.01 | 0.02* [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.02 [−0.04, 0.01], <0.01 | −0.03* [−0.06, −0.01], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | 0.01* | 0.02 |

| Cumulative diary sleep debt (not adjusted for covariates; n = 199, # of observations = 3,399) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02** [0.01, 0.04], 0.01 | 0.02* [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.01], <0.01 | −0.03* [−0.06, −0.01], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | 0.02* | 0.02 |

| . | Negative affect . | . | Positive affect . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High arousal | Low arousal | High arousal | Low arousal | |

| Cumulative actigraphy sleep debt (adjusted for covariates; n = 190, # of observations = 3,152) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02* [0.00, 0.04], <0.01 | 0.01 [−0.01, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.02], <0.01 | −0.03† [−0.05, 0.00], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | — | — |

| Cumulative actigraphy sleep debt (not adjusted for covariates; n = 190, # of observations = 3,152) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02 [0.00, 0.03], <0.01† | 0.01 [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.03, 0.02], <0.01 | −0.03 [−0.05, 0.00], <0.01† |

| Within (random) | — | — | — | — |

| Cumulative diary sleep debt (adjusted for covariates; n = 199, # of observations = 3,399) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02** [0.01, 0.04], <0.01 | 0.02* [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.02 [−0.04, 0.01], <0.01 | −0.03* [−0.06, −0.01], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | 0.01* | 0.02 |

| Cumulative diary sleep debt (not adjusted for covariates; n = 199, # of observations = 3,399) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02** [0.01, 0.04], 0.01 | 0.02* [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.01], <0.01 | −0.03* [−0.06, −0.01], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | 0.02* | 0.02 |

The predictor for all models is within-person centered cumulative sleep debt. Values presented are unstandardized coefficients, [95% confidence intervals], and Cohen’s f2. Random effects for within-person level predictor and lagged outcomes were included in all initial models, and dropped if models did not converge (represented by —); Cohen’s f2 are presented for models with random effects for within-person predictor. Values for sample sizes are the number of individual participants and number of observations for models with corresponding outcomes. The following covariates were included in all models: previous day sleep (lagged outcome), body mass index, born in Australia, sex, year level, non-white, work status, parental marital status, study day, and day of week.

*p < .05, **p < .01. †p = .059 for adjusted model, p = .058 for non-adjusted models.

| . | Negative affect . | . | Positive affect . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High arousal | Low arousal | High arousal | Low arousal | |

| Cumulative actigraphy sleep debt (adjusted for covariates; n = 190, # of observations = 3,152) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02* [0.00, 0.04], <0.01 | 0.01 [−0.01, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.02], <0.01 | −0.03† [−0.05, 0.00], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | — | — |

| Cumulative actigraphy sleep debt (not adjusted for covariates; n = 190, # of observations = 3,152) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02 [0.00, 0.03], <0.01† | 0.01 [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.03, 0.02], <0.01 | −0.03 [−0.05, 0.00], <0.01† |

| Within (random) | — | — | — | — |

| Cumulative diary sleep debt (adjusted for covariates; n = 199, # of observations = 3,399) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02** [0.01, 0.04], <0.01 | 0.02* [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.02 [−0.04, 0.01], <0.01 | −0.03* [−0.06, −0.01], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | 0.01* | 0.02 |

| Cumulative diary sleep debt (not adjusted for covariates; n = 199, # of observations = 3,399) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02** [0.01, 0.04], 0.01 | 0.02* [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.01], <0.01 | −0.03* [−0.06, −0.01], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | 0.02* | 0.02 |

| . | Negative affect . | . | Positive affect . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High arousal | Low arousal | High arousal | Low arousal | |

| Cumulative actigraphy sleep debt (adjusted for covariates; n = 190, # of observations = 3,152) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02* [0.00, 0.04], <0.01 | 0.01 [−0.01, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.02], <0.01 | −0.03† [−0.05, 0.00], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | — | — |

| Cumulative actigraphy sleep debt (not adjusted for covariates; n = 190, # of observations = 3,152) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02 [0.00, 0.03], <0.01† | 0.01 [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.03, 0.02], <0.01 | −0.03 [−0.05, 0.00], <0.01† |

| Within (random) | — | — | — | — |

| Cumulative diary sleep debt (adjusted for covariates; n = 199, # of observations = 3,399) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02** [0.01, 0.04], <0.01 | 0.02* [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.02 [−0.04, 0.01], <0.01 | −0.03* [−0.06, −0.01], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | 0.01* | 0.02 |

| Cumulative diary sleep debt (not adjusted for covariates; n = 199, # of observations = 3,399) | ||||

| Within (fixed) | 0.02** [0.01, 0.04], 0.01 | 0.02* [0.00, 0.03], <0.01 | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.01], <0.01 | −0.03* [−0.06, −0.01], <0.01 |

| Within (random) | — | — | 0.02* | 0.02 |

The predictor for all models is within-person centered cumulative sleep debt. Values presented are unstandardized coefficients, [95% confidence intervals], and Cohen’s f2. Random effects for within-person level predictor and lagged outcomes were included in all initial models, and dropped if models did not converge (represented by —); Cohen’s f2 are presented for models with random effects for within-person predictor. Values for sample sizes are the number of individual participants and number of observations for models with corresponding outcomes. The following covariates were included in all models: previous day sleep (lagged outcome), body mass index, born in Australia, sex, year level, non-white, work status, parental marital status, study day, and day of week.

*p < .05, **p < .01. †p = .059 for adjusted model, p = .058 for non-adjusted models.

Based on sleep diary, higher cumulative sleep debt predicted higher next-day high- and low-arousal NA (b = 0.02, p = .004, and b = 0.02, p = .035 respectively), and lower low arousal PA (b = −0.03, p = .018). Each additional hour of cumulative diary sleep debt was associated with a 0.02 increase in high- and low-arousal NA, and a 0.03 decrease in low arousal PA the following day. The association between diary sleep debt and high arousal PA was not significant (p > .05).

Fixed and random effects were included in all models, with random effects removed in cases of non-convergence. We were able to include random effects in models examining associations between diary sleep debt and high- and low-arousal PA. Significant random effects were found for cumulative diary sleep debt predicting high arousal PA (f2 = 0.01, p = .021), indicating significant individual differences in the association.

Effects of covariates

As seen in Supplementary Table S1, higher levels of NA and PA the previous day consistently predicted higher NA and PA on a given day respectively (all p < .001). These associations differed significantly between individuals for all affect domains, as indicated by the significant random effects on within-person lagged outcome (p-values ≤ .001; see Supplementary Table S1). Being non-white was associated with significantly lower high arousal PA (all p < .021), and working part-time or casually was associated with significantly lower low arousal PA (all p < .019).

Discussion

This intensive longitudinal study examined trajectories of daily perceived sleep need and debt across school and vacation periods, and whether cumulative sleep debt on a given day predicted adolescents’ affect the following day. Findings indicated that adolescents experienced sustained sleep debt across school days. Weekends and vacations appeared to be opportunities to reduce sleep debt: during these times, cumulative sleep debt decreased, and self-reported sleep duration met adolescents’ perceived sleep need. Higher cumulative sleep debt on a given day was associated with higher NA and lower PA the next day.

Trajectories of perceived sleep need and cumulative sleep debt

Based on daily measurements, participants reported requiring about 8 h of sleep to function well. Although this is slightly lower than reported in cross-sectional studies (e.g. > 9 h in most adolescent athletes) [19], it is within the recommended 8 to 10 h of sleep for this age group [36].

Based on daily trajectories, adolescents’ perceived sleep need appeared to be lower early in the school week, before increasing in the second half of the week and the weekend. This may be related to trajectories of cumulative sleep debt across the week. During weekends, based on self-reported sleep duration, adolescents were able to fully “pay off” the sleep debt incurred across the previous weekdays. Therefore, they may feel “recharged” on sleep going into the next school week, and consequently, perceive a lower need for sleep in the immediate days to follow (early in a school week). Toward the end of the school week, however, adolescents’ perceived sleep need appeared somewhat higher, perhaps in response to the consecutive nights of restricted sleep opportunity. Higher perceived sleep need over the weekend may reflect adolescents’ awareness of the need to “make up” for the sleep loss during the preceding weekdays.

Trajectories of cumulative sleep debt during the 2-week vacation with relatively unconstrained sleep opportunities suggest recovery from school-related sleep restriction. At the start of the first vacation week, cumulative diary sleep debt quickly reduced to around 0 (i.e. perceived sleep need was met), then subsequently decreased to below 0 (i.e. perceiving sleeping more than needed) over the rest of the first vacation week. This suggests that adolescents were catching up on sleep, and recovery from school-related sleep restriction was occurring.

This trend reversed going into the second vacation week, where adolescents’ diary sleep debt stabilized around 0. Based on this, we speculate that adolescents may perceive themselves as being fully recovered from school-related sleep restriction after one vacation week, and were now sleeping approximately as much as their perceived sleep need. This is consistent with our previous findings in adolescents: TST increased dramatically when first entering the vacation, before gradually decreasing and plateauing [15].

Overall, cumulative sleep debt trajectories are consistent between actigraphy and sleep diary. However, cumulative diary sleep debt was lower than actigraphy sleep debt across the study, likely due to discrepancies between self-reported and actigraphy-assessed sleep duration (by almost an hour). This discrepancy is consistent with previous studies [37], and may be caused by actigraphy overestimating wake and underestimating sleep time with increased sleep motor activity in the adolescent population [38].

Cumulative sleep debt negatively impacts daily affect

Higher cumulative sleep debt had negative impacts on adolescents’ affect on a daily basis. Specifically, higher cumulative actigraphy sleep debt predicted higher next-day high arousal NA and showed a trend in predicting lower low arousal PA. Higher cumulative diary sleep debt predicted higher NA (regardless of arousal), and lower low arousal PA the following day.

First, consistent with previous research [39, 40], diary sleep debt (compared to actigraphy) shared somewhat stronger associations with daily affect. This may reflect the relevance of individuals’ perceptions of their own sleep, rather than objectively measured sleep, for their affect/ mood. However, findings on diary and actigraphy are more similar than different: cumulative sleep debt on both measures was associated with higher high arousal NA (e.g. nervous, irritable) and lower low arousal PA (e.g. calm, relaxed) next day; neither predicted high arousal PA (e.g. happy, enthusiastic), which may be more affected by other factors such as an exciting event, rather than sleep. These two measures diverged on low arousal NA (e.g. sad, lonely), which diary but not actigraphy sleep debt predicted. These findings are largely consistent with the few studies that have incorporated both valence and arousal when examining sleep-affect associations [41].

Second, although these findings are in line with past studies linking chronic, partial sleep deprivation with elevated NA and dampened PA [4], in this study, cumulative sleep debt (diary and actigraphy) had stronger associations with negative, compared to positive affect. In contrast, majority of past studies have found stronger associations between sleep duration with positive, rather than negative affect [5, 42]. It is possible that cumulative sleep debt may predict affect differently compared to single-day sleep duration or quality measures. Therefore, cumulative sleep debt warrants further investigation as a separate construct to sleep duration per se.

Cumulative sleep debt not only incorporates an individual’s brief sleep history (past 3 days in this study), but also individual’s perceived sleep need, in the context of adolescents’ natural lives. These considerations, together, may explain why it is a unique predictor of daily affect. First, single-day assessments of sleep duration or quality do not recognize the impact of previous days’ sleep on a given day’s sleep, and how sleep over multiple, consecutive days may have a compounding impact on mood. Second, by incorporating perceived sleep need, cumulative sleep debt examines an individual’s subjective experiences of sleep insufficiency, which may share stronger associations with mood. Relatedly, measuring perceived sleep need on a daily basis takes into consideration how perception of sleep need may change on a daily basis, depending on next-day daytime activities. This recognizes events that occur in everyday life (e.g. stress, fatigue) that impact individuals’ daily sleep and affect [9].

It is worth noting that although statistically significant, the effects of cumulative sleep debt on affect, after controlling for 10 other covariates is rather small in size. This suggests that many non-sleep-related factors, especially affect the previous day, play important roles in adolescents’ daily affect, and perceived sleep debt is one of many contributing factors. Further, in this study, the strengths of the associations between cumulative sleep debt and affect did not differ significantly between school and vacation periods. It is possible that regularly reducing cumulative sleep debt during weekends may be protective of affect.

Finally, among the models that converged, some showed significant individual differences in the degree that cumulative sleep debt was predicting next day affect. On average, cumulative diary sleep debt did not predict high arousal PA the following day. However, significant random effects indicate that this relationship differs for individuals. For example, higher cumulative sleep debt may predict lower high-arousal PA the next day in some individuals, whereas for others, this relationship may be of different magnitudes or even in the opposite direction. Future investigations identifying predictors of such individual differences are needed.

Limitations

Actigraphy may underestimate sleep and over-estimate wake in adolescent populations, which may explain the discrepancy between actigraphy-assessed and self-report sleep duration [15, 37]. Systematic bias, however, is unlikely to affect interpretations of sleep debt trajectories or its association with affect.

Only a small percentage of participants reported low current mental health conditions, and overall levels of NA were low across the study. Although sensitivity analyses revealed minimal changes after excluding participants with current mental health, and/ or sleep conditions, future studies with clinical samples are necessary to determine if findings from this community sample may generalize to adolescents with mental health and/or sleep conditions.

This study did not take into account numerous other factors that may influence findings, for example, experiences of stress and hassles [43], knowledge about age-appropriate sleep need, and sleep-related health behaviors. Finally, further investigations are needed to examine individual differences in trajectories of perceived sleep need and cumulative sleep debt, predictors of such individual differences, and how long sustained or recovered sleep debt may be relevant to functional outcomes (e.g. mood, cognition).

Conclusion and Implications

The current study utilized an intensive, longitudinal study design across school terms and vacations. Adolescents reported obtaining insufficient sleep relative to their perceived need on school days but utilized weekends and vacations as opportunities to recuperate from such sleep deprivation. Cumulative sleep debt consistently predicted daily affect and may be a unique consideration in future research and intervention.

Given early school start times in many parts of the world, it is often not feasible to remove sleep restrictions in adolescents. However, preventing consecutive days of short sleep (i.e. accumulation of sleep debt) may still provide benefits to adolescents’ mood and may be a more tangible therapeutic target.

Adolescents’ perception of sleep need may be another potential therapeutic target. Despite the increase in large school-based and targeted sleep awareness programs, the proportion of adolescents obtaining sufficient sleep is decreasing [44]. Motivating adolescents toward successful change in sleep behaviors is likely contingent on adolescents’ own perceptions of how much sleep they need, taking into consideration various activities and commitments that may occur in their daily lives. Nights with higher-than-average studying, at the expense of sleep, are associated with poorer academic performance the following day [20]; shorter-than-usual sleep has also been linked to higher anxiety and fatigue the next day [9]. However, it is unclear if adolescents perceived needing less sleep on these nights with shorter-than-usual sleep. If so, these perceptions and beliefs associated with them may be some of the important factors to address in interventions.

Finally, this study affirmed findings in the literature that weekends and vacations are crucial periods for reducing accumulated sleep debt in adolescents. While our findings support adolescents utilizing these periods to “recharge” sleep, a considered approach is needed such that large differences in weekday and weekend sleep patterns are not further exacerbated. Wherever possible, interventions that target the cause of adolescent sleep restriction (e.g. bright light therapy and light hygiene to advance circadian phase, delaying school start time) are preferred approaches.

Funding

Wiley (APP1178487) and Bei (APP1140299) are supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowships.

Acknowledgments

All authors made substantial contributions to the work presented and approved the final version of the manuscript. We thank the participants who volunteered their time toward this study, and everyone who assisted with data collection: Anthony Hand, Ashley Lam, Bronte Mathews, Cassandra Li, Cornelia Wellecke, Hannah Spring, Laura Astbury, and Svetlana Maskevich. We also gratefully acknowledge the equipment support from Monash University Sleep and Circadian Rhythms Laboratory, Dr. Christian Nicholas, Prof. Greg Murray, and Dr. Megan Spencer-Smith.

Disclosure Statement

Financial Disclosure: None.

Nonfinancial Disclosure: Preprint for this manuscript is submitted to PsyArXiv.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be available upon reasonable request made to the corresponding author.

References

Comments