-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paige Mewton, Amy Dawel, Elizabeth J Miller, Yiyun Shou, Bruce K Christensen, Meta-analysis of Face Perception in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: Evidence for Differential Impairment in Emotion Face Perception, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Volume 51, Issue 1, January 2025, Pages 17–36, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbae130

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSD) are associated with face perception impairments. It is unclear whether impairments are equal across aspects of face perception or larger—indicating a differential impairment—for perceiving emotions relative to other characteristics (eg, identity, age). While many studies have attempted to compare emotion and non-emotion face perception in SSD, they have varied in design and produced conflicting findings. Additionally, prior meta-analyses on this topic were not designed to disentangle differential emotion impairments from broader impairments in face perception or cognition. We hypothesize that SSD-related impairments are larger for emotion than non-emotion face perception, but study characteristics moderate this differential impairment.

We meta-analyzed 313 effect sizes from 104 articles to investigate if SSD-related impairments are significantly greater for emotion than non-emotion face perception. We tested whether key study characteristics moderated these impairments, including SSD severity, sample intelligence matching, task difficulty, and task memory dependency.

We found significantly greater impairments for emotion (Cohen’s d = 0.74) than non-emotion face perception (d = 0.55) in SSD relative to control samples, regardless of SSD severity, intelligence matching, or task difficulty. Importantly, this effect was obscured when non-emotion tasks used a memory-dependent design.

This is the first meta-analysis to demonstrate a differential emotion impairment in SSD that cannot be explained by broader impairments in face perception or cognition. The findings also underscore the critical role of task matching in studies of face perception impairments; to prevent confounding influences from memory-dependent task designs.

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSD) are associated with face perception impairments.1–7 However, it is unclear whether these impairments are specific to (or larger for) face emotion perception or reflect global impairments in all facial judgments, including face identity, age, and gender.1 Studies have produced conflicting results which have been attributed to variations in study design.1,8 Although meta-analyses have attempted to quantify face perception impairments and how they are impacted by study features,2,3 they have omitted critical design components required to distinguish differential impairments from general cognitive-perceptual difficulties in SSD.9,10 Therefore, a refined meta-analysis is needed to determine whether impairments are larger for emotion than non-emotion face perception and identify study features that moderate the difference in impairments. Social cognitive and social functioning difficulties contribute substantially to the burden of illness in SSD11–13 and are associated with impairments in emotion face perception tasks.14–16 Thus, it is critical to determine whether emotion impairments are a specific characteristic of SSD or a secondary consequence of general cognitive-perceptual impairments, to better understand the mechanisms underlying SSD-related social cognitive difficulties and identify targets for treatment.

Individual studies measuring SSD-related face perception impairments have produced conflicting findings. The term “SSD-related impairments” throughout this article refers to lower task performance relative to community samples, which largely comprise of individuals without psychiatric diagnoses. While it is critical to identify areas where SSD samples perform statistically worse than community samples, we acknowledge that this approach does not capture instances where SSD samples demonstrate strengths or heightened functioning relative to community samples. The latter line of research is of equal importance, although outside of the scope of this paper. For example, impairments were found for both emotion and non-emotion tasks by Loughland et al17; for emotion but not non-emotion tasks by Bediou et al18,19; and for non-emotion but not emotion tasks by Bellack et al20. On balance, however, emotion impairments are observed more frequently (approximately 80% of studies2) than non-emotion impairments (approximately 30% of studies21). This pattern may reflect a larger emotion impairment7 or variation and limitations in study design.

A primary concern regarding prior meta-analyses and many individual studies is that they fail to directly compare the size of SSD-related impairments on emotion tasks with that of appropriate comparison tasks. This is crucial since people with SSD show general cognitive impairments9 and perform poorly relative to non-clinical samples across many cognitive tasks.22–24 This general cognitive impairment implies that SSD samples will likely perform worse than comparison samples on most tasks due to the cognitive processes involved. Therefore, to identify a differential emotion impairment, it is necessary to demonstrate significantly greater impairment on emotion tasks compared to non-emotion tasks with similar cognitive demands (see Chapman and Chapman9,10,25 for the differential deficit challenge). For example, Kohler’s2 meta-analysis found an SSD-related impairment in emotion perception but did not include a comparison task, so it cannot rule out the influence of global face perception or general cognition. In contrast, Chan et al’s3 meta-analysis assessed emotion and non-emotion face perception, and found SSD-related impairments for both task types (Cohen’s d for emotion tasks = −0.85; non-emotion tasks = −0.70). However, Chan et al did not test whether the impairment for emotion tasks was significantly larger than for non-emotion tasks, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn from their results. Additionally, prior meta-analyses have not adequately addressed key moderating factors, such as the demands or difficulty of experimental tasks.

Key Sources of Study Design Variation

Inconsistent results in the literature are unsurprising given the substantial variability in study designs.8 Our second aim was to determine if differences in the size of emotion and non-emotion impairments are moderated by the key study characteristics reviewed below.

SSD Severity

Studies vary in the SSD diagnostic samples they recruit, leading to differences in symptom severity and community dysfunction.26 Dimensional conceptualizations suggest SSD exists on a spectrum,27 with symptoms varying in magnitude rather than quality across diagnostic subcategories. Symptoms are most prominent in severe presentations (e.g., schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder) and attenuated in milder presentations that are often without active psychosis symptoms (e.g., high trait schizotypy). Emotion perception impairments also appear to be dimensionally distributed in SSD, correlating with symptom severity,1 and being larger in samples with schizophrenia (e.g., Cohen’s d = 0.853 to 0.912) than milder SSD presentations (e.g., d = 0.4828). For non-emotion face perception, people with schizophrenia have moderate to large impairments which also correlate with symptom severity.3 However, evidence for non-emotion impairments in milder SSD presentations is lacking, with studies finding performance comparable to community samples.29–31 This lack of evidence for non-emotion impairments in milder SSD presentations may reflect under-powering of studies due to small effect sizes and small samples (e.g., Gee et al32 and Seiferth et al33).

Our meta-analysis included studies sampling the full range of SSD diagnoses to optimize power and investigate impairment profiles across the SSD spectrum. Consistent with a dimensional conceptualization,27 we hypothesized that the face perception impairment profile would be similar across SSD samples, but impairments would be smaller in milder SSD presentations (e.g., high schizotypy, early psychosis) compared to more severe presentations (i.e., schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder). Consistent with smaller impairments, we hypothesized that the difference between emotion and non-emotion impairments would also be smaller in studies sampling low-severity compared to high-severity SSD.

Intelligence Matching

SSD and comparison samples are often matched on measures of global intelligence (or years of education as a proxy) to control for SSD-related general cognitive impairments.34,35 However, this matching reduces meaningful variability between samples36–38 and may inadvertently recruit SSD or comparison samples with above- or below-average intelligence, respectively. This sampling bias, known as the matching fallacy, can dilute critical differences that would emerge with representative SSD and comparison samples, potentially misrepresenting true effects. Moreover, SSD symptom severity is negatively correlated with years of education38; as such, matching SSD and comparison samples on years of education would likely result in SSD samples with milder symptoms. Our meta-analysis tested whether intelligence matching moderates the difference between emotion and non-emotion face perception impairments, hypothesizing that the difference would be reduced when SSD and comparison samples were matched compared to unmatched for intelligence.

Memory Dependency

Some face perception tasks call on non-face skills for successful completion. For example, face identification tasks often rely on memory. Typically, participants learn some target faces and are then asked to differentiate the targets from unlearned distractor faces (e.g., Warrington Recognition Memory Test39). The memory impairments associated with SSD40 may contribute to impaired performance on such tasks, irrespective of any impairment in face perception. Consistent with this, SSD-related impairments are more common in identity perception tasks that rely on memory.21 Our meta-analysis further interrogated if memory dependency moderates the difference between emotion and non-emotion face perception impairments, hypothesizing that the difference would be reduced when non-emotion tasks were memory-dependent compared to memory-independent.

Task Difficulty

The difficulty of a task influences its sensitivity to reveal differences in ability between groups, potentially altering the apparent presence or size of group-related impairments.9,10 The impact of task difficulty is clearest in floor- and ceiling-effects. If a task is too easy or difficult, the score distributions of different samples will be compressed together, making it harder to distinguish true differences in the groups’ underlying abilities.9,10 Moreover, if emotion and non-emotion tasks are unequally difficult, differential impairments (e.g., for emotion perception) could be mistaken for global impairments (e.g., equal impairment for all face perception tasks).10 For example, comparing a close-to-ceiling emotion task with a more difficult non-emotion task may cause an emotion impairment to appear falsely small and equivalent to that for the non-emotion task. Indeed, commonly used emotion tasks are often criticized for producing close-to-ceiling accuracy in community samples.41 In contrast, identity perception is often measured by the Benton Test of Facial Recognition,42 which is routinely harder than the emotion face tasks used for comparison.8,21 Regrettably, the relative difficulty of tasks is rarely considered when measuring SSD-related face perception.8 In the present meta-analysis, we tested if task difficulty moderates the difference between emotion and non-emotion face perception impairments, hypothesizing that the difference would be reduced when tasks approached the ceiling.

The Present Study

The present meta-analysis aimed to provide a direct and aggregated statistical comparison between emotion and non-emotion face perception impairments in SSD, previously missing from the literature. Our primary focus was on whether SSD-related impairments differed across task type (emotion vs non-emotion). We also investigated if several critical design variables might account for contradictory findings concerning a greater (differential) impairment for emotion tasks. In summary, these moderator variables were SSD severity, intelligence matching of samples, task memory dependency, and task difficulty.

We chose not to control for these variables via covariate analysis as this approach can obscure main effects by removing meaningful shared variance between main effects and covariates.43

The meta-analysis also provided a timely update in synthesizing this literature, with prior meta-analyses on the topic now over a decade old.2,3 We hypothesized that:

H1: SSD-related impairments would be significantly larger for emotion than non-emotion face perception tasks (i.e., a differential impairment).

H2: The differential emotion impairment would be moderated by:

a. SSD severity: the differential impairment would be smaller in low- compared to high-severity SSD samples.

b. intelligence matching: the differential impairment would be smaller when samples are matched compared to unmatched for intelligence.

c. memory dependency: the differential impairment would be smaller when non-emotion tasks are memory-dependent compared to memory-independent.

d. task difficulty: the differential impairment would be smaller when tasks were close-to-ceiling compared to not.

Method

Search Strategy

PubMed, PsychINFO, and Scopus databases were searched in January 2024 using terms relating to SSD, faces, and emotion (supplementary material S1). Eligibility criteria (supplementary material S2) required that articles:

included a sample with SSD and a control sample that were not a clinical group or relatives of people with SSD.

included a behavioral measure of accuracy for emotion and non-emotion face perception.

included stimuli that were static, whole images of human faces.

were published as a peer-reviewed full-text article in English.

Screening and Data Extraction

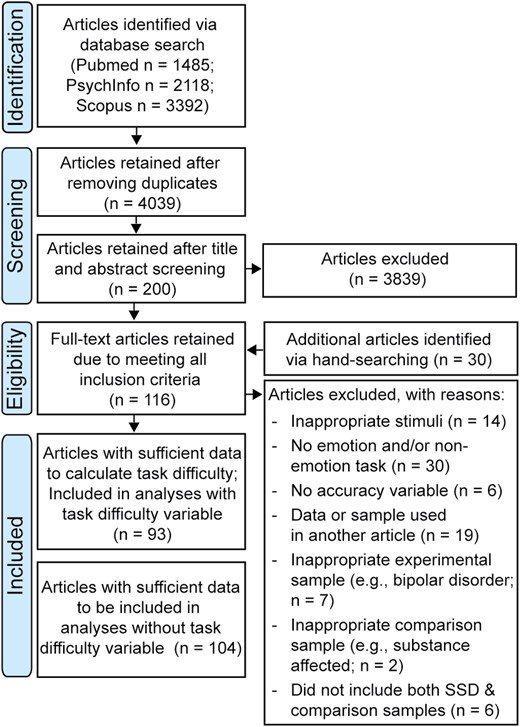

Figure 1 illustrates the eligibility screening process. Data were extracted by PM using Qualtrics (supplementary material S3). Web Plot Digitizer44 was used to extract numerical data from graphs. Authors were contacted at least twice to request critical data omitted from papers. To assess inter-coder reliability, 10% of articles were randomly selected and independently coded by EJM. Agreement between coders was high (M = 91.1%, SD = 6.3%, range = 78.7%–98.2%). Differences between coders were discussed and resolved.

Standardized mean differences between SSD and community sample task performance were calculated to quantify the size of SSD-related impairments. Cohen’s d45 was used as it is common in psychology and consistent with Chan et al’s3 approach. Where possible, means and SDs were extracted; otherwise, Cohen’s d was calculated from F- or t-values46 or extracted directly from articles. Larger Cohen’s d effect sizes indicated larger SSD-related impairments. Evidence of a differential impairment in emotion perception was indicated when there was a significantly larger effect size for emotion than non-emotion tasks.

If multiple papers reported overlapping samples (eg, Calkins et al47 and Pinkham et al34), the study with the largest sample size was included for analysis. Articles often included multiple emotion and/or non-emotion tasks, or provided data separately for different emotion categories within each task. Where possible (98% of data), effect sizes were extracted separately for separate tasks. When data was provided separately per emotion and a total task score was not available, a total score was estimated by combining the mean scores of individual emotions. Primary analyses test all emotions combined. Additionally, supplementary materials S4–S5 present the analysis of H1 across different emotion categories.

Coding Moderator Variables

Table 1 lists the included articles14,18–20,29,30,32,34,35,40,47–138 and their moderator variables. Categorical moderators were coded at 2 levels. SSD severity was coded as high-severity (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders) and low-severity. The low-severity subset included all other diagnostic categories, which may increase heterogeneity but was necessary to achieve sufficient power for moderation analyses. Some articles reported combined high- and low-severity samples; these cases were conservatively coded as high-severity SSD to ensure low-severity group impairments were not amplified by a minority of high-severity participants (supplementary materials S6).

| Article . | Task Type Effect Size Count . | SSD sample . | IQ matching . | Memory-dependant non-emotion task used? . | Close-to-ceiling task used? . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion . | Identity . | Gender . | Age . | Other . | |||||

| Addington & Addington, 1998 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Both types | No |

| Andric et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | No |

| Archer et al., 1992 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Barkhof et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Baudouin et al., 2002 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Bediou et al., 2005 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Bediou et al., 2007 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Belge et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Age, Emotion, Gender, Other) |

| Bellack et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Bigelow et al., 2006 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Brief Psychotic Disorder | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Borod et al., 1993 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Caldiroli et al., 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Calkins et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Campanella et al., 2006 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Chen et al., 2012 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | No |

| de Achaval, 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Derntl et al., 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Dickey et al., 2011 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Doop & Park, 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Other) |

| Drusch et al., 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Drusch et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Edwards et al., 2001 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Other | Partial | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Erol et al., 2013 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Other | Yes | No | No |

| Evangeli & Broks, 2000 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Identity, Other) |

| Exner et al., 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Fakra et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Feinberg et al., 1986 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Frommann et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Gee et al., 2012 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Substance Induced Psychosis | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Germine & Hooker, 2011 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | No | No | No |

| Gessler et al., 1989 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Goghari et al., 2011 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Goghari et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Goghari, & Sponheim, 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Goldenberg et al., 2012 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Gur et al., 2002 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Habel et al., 2000 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Partial | No | Yes (Age, Emotion) |

| Habel et al., 2006 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, High Schizotypy, Other | Yes | No | No |

| Habel, Chechko et al., 2010 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Habel, Koch et al., 2010 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hall et al., 2004 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hall et al., 2008 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Heimberg et al., 1992 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hooker & Park 2002 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Identity) |

| Horan et al., 2003 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Johnston et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Kerr & Neale, 1993 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Kosmidis et al., 2007 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Kucharska-Pietura et al., 2005 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Kucharska-Pietura, Mortimer et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Kucharska-Pietura, Tylec et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Kuo et al., 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Lee et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Li et al., 2010 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Linden et al., 2010 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Maat et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Mamah et al., 2021 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Martin et al., 2005 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Martinez-Dominguez et al., 2015 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Meijer et al., 2012 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Brief Psychotic Disorder, Other | No | No | No |

| Mier et al., 2010 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Mier et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Modinos et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | No | No | No |

| Mueser et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | No |

| Novic et al., 1984 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Okada et al., 2015 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Penn et al., 2000 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Pinkham et al., 2008 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Pinkham et al., 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | No |

| Pomarol-Clotet et al., 2010 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | No |

| Poreh et al., 1994 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | Yes | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Priyesh et al., 2021 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Punchaichira et al., 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Quintana et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Ramos-Loyo et al., 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| Ramos-Loyo et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| Randers et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | No | No |

| Rocca et al., 2009 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Sachse et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Salem et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Schneider et al., 1998 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Age, Emotion) |

| Schneider et al., 2006 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Both types | No |

| Schwartz et al., 2002 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Partial | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| She et al., 2017 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Silver et al., 2003 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Silver et al., 2005 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | No |

| Silver et al., 2009 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Soria Bauser et al., 2012 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Spilka & Goghari, 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Tripoli et al., 2022 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | First Episode Psychosis | No | No | No |

| Tylec et al., 2017 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| van Rijn et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | No | Yes (Identity) |

| van 't Wout et al., 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Villalta-Gil et al., 2013 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity, Gender) |

| Walker, 1984 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Watanuki et al., 2016 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Whittaker et al., 2001 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Wickline et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Williams et al., 2007 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | No | No | No |

| Wynn et al., 2008 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Wynn et al., 2013 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Wynn et al., 2023 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusion Disorder, Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified | Partial | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Yagci et al., 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Yamada et al., 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Article . | Task Type Effect Size Count . | SSD sample . | IQ matching . | Memory-dependant non-emotion task used? . | Close-to-ceiling task used? . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion . | Identity . | Gender . | Age . | Other . | |||||

| Addington & Addington, 1998 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Both types | No |

| Andric et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | No |

| Archer et al., 1992 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Barkhof et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Baudouin et al., 2002 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Bediou et al., 2005 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Bediou et al., 2007 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Belge et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Age, Emotion, Gender, Other) |

| Bellack et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Bigelow et al., 2006 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Brief Psychotic Disorder | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Borod et al., 1993 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Caldiroli et al., 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Calkins et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Campanella et al., 2006 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Chen et al., 2012 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | No |

| de Achaval, 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Derntl et al., 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Dickey et al., 2011 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Doop & Park, 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Other) |

| Drusch et al., 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Drusch et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Edwards et al., 2001 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Other | Partial | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Erol et al., 2013 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Other | Yes | No | No |

| Evangeli & Broks, 2000 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Identity, Other) |

| Exner et al., 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Fakra et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Feinberg et al., 1986 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Frommann et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Gee et al., 2012 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Substance Induced Psychosis | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Germine & Hooker, 2011 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | No | No | No |

| Gessler et al., 1989 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Goghari et al., 2011 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Goghari et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Goghari, & Sponheim, 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Goldenberg et al., 2012 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Gur et al., 2002 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Habel et al., 2000 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Partial | No | Yes (Age, Emotion) |

| Habel et al., 2006 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, High Schizotypy, Other | Yes | No | No |

| Habel, Chechko et al., 2010 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Habel, Koch et al., 2010 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hall et al., 2004 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hall et al., 2008 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Heimberg et al., 1992 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hooker & Park 2002 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Identity) |

| Horan et al., 2003 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Johnston et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Kerr & Neale, 1993 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Kosmidis et al., 2007 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Kucharska-Pietura et al., 2005 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Kucharska-Pietura, Mortimer et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Kucharska-Pietura, Tylec et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Kuo et al., 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Lee et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Li et al., 2010 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Linden et al., 2010 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Maat et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Mamah et al., 2021 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Martin et al., 2005 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Martinez-Dominguez et al., 2015 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Meijer et al., 2012 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Brief Psychotic Disorder, Other | No | No | No |

| Mier et al., 2010 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Mier et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Modinos et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | No | No | No |

| Mueser et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | No |

| Novic et al., 1984 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Okada et al., 2015 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Penn et al., 2000 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Pinkham et al., 2008 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Pinkham et al., 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | No |

| Pomarol-Clotet et al., 2010 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | No |

| Poreh et al., 1994 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | Yes | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Priyesh et al., 2021 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Punchaichira et al., 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Quintana et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Ramos-Loyo et al., 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| Ramos-Loyo et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| Randers et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | No | No |

| Rocca et al., 2009 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Sachse et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Salem et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Schneider et al., 1998 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Age, Emotion) |

| Schneider et al., 2006 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Both types | No |

| Schwartz et al., 2002 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Partial | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| She et al., 2017 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Silver et al., 2003 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Silver et al., 2005 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | No |

| Silver et al., 2009 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Soria Bauser et al., 2012 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Spilka & Goghari, 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Tripoli et al., 2022 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | First Episode Psychosis | No | No | No |

| Tylec et al., 2017 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| van Rijn et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | No | Yes (Identity) |

| van 't Wout et al., 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Villalta-Gil et al., 2013 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity, Gender) |

| Walker, 1984 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Watanuki et al., 2016 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Whittaker et al., 2001 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Wickline et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Williams et al., 2007 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | No | No | No |

| Wynn et al., 2008 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Wynn et al., 2013 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Wynn et al., 2023 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusion Disorder, Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified | Partial | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Yagci et al., 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Yamada et al., 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

Note. The Task Type Effect Size Count columns count the number of effect sizes for each task type, which may include different tasks, different samples completing each task, or a combination of the two. The IQ Matching column is labelled as “Partial” if some samples were matched for intelligence and others were not. If a close-to-ceiling task was used, the task type is listed in parentheses.

| Article . | Task Type Effect Size Count . | SSD sample . | IQ matching . | Memory-dependant non-emotion task used? . | Close-to-ceiling task used? . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion . | Identity . | Gender . | Age . | Other . | |||||

| Addington & Addington, 1998 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Both types | No |

| Andric et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | No |

| Archer et al., 1992 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Barkhof et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Baudouin et al., 2002 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Bediou et al., 2005 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Bediou et al., 2007 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Belge et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Age, Emotion, Gender, Other) |

| Bellack et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Bigelow et al., 2006 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Brief Psychotic Disorder | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Borod et al., 1993 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Caldiroli et al., 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Calkins et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Campanella et al., 2006 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Chen et al., 2012 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | No |

| de Achaval, 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Derntl et al., 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Dickey et al., 2011 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Doop & Park, 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Other) |

| Drusch et al., 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Drusch et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Edwards et al., 2001 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Other | Partial | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Erol et al., 2013 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Other | Yes | No | No |

| Evangeli & Broks, 2000 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Identity, Other) |

| Exner et al., 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Fakra et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Feinberg et al., 1986 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Frommann et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Gee et al., 2012 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Substance Induced Psychosis | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Germine & Hooker, 2011 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | No | No | No |

| Gessler et al., 1989 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Goghari et al., 2011 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Goghari et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Goghari, & Sponheim, 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Goldenberg et al., 2012 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Gur et al., 2002 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Habel et al., 2000 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Partial | No | Yes (Age, Emotion) |

| Habel et al., 2006 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, High Schizotypy, Other | Yes | No | No |

| Habel, Chechko et al., 2010 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Habel, Koch et al., 2010 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hall et al., 2004 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hall et al., 2008 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Heimberg et al., 1992 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hooker & Park 2002 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Identity) |

| Horan et al., 2003 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Johnston et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Kerr & Neale, 1993 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Kosmidis et al., 2007 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Kucharska-Pietura et al., 2005 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Kucharska-Pietura, Mortimer et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Kucharska-Pietura, Tylec et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Kuo et al., 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Lee et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Li et al., 2010 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Linden et al., 2010 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Maat et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Mamah et al., 2021 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Martin et al., 2005 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Martinez-Dominguez et al., 2015 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Meijer et al., 2012 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Brief Psychotic Disorder, Other | No | No | No |

| Mier et al., 2010 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Mier et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Modinos et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | No | No | No |

| Mueser et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | No |

| Novic et al., 1984 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Okada et al., 2015 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Penn et al., 2000 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Pinkham et al., 2008 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Pinkham et al., 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | No |

| Pomarol-Clotet et al., 2010 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | No |

| Poreh et al., 1994 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | Yes | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Priyesh et al., 2021 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Punchaichira et al., 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Quintana et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Ramos-Loyo et al., 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| Ramos-Loyo et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| Randers et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | No | No |

| Rocca et al., 2009 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Sachse et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Salem et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Schneider et al., 1998 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Age, Emotion) |

| Schneider et al., 2006 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Both types | No |

| Schwartz et al., 2002 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Partial | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| She et al., 2017 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Silver et al., 2003 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Silver et al., 2005 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | No |

| Silver et al., 2009 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Soria Bauser et al., 2012 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Spilka & Goghari, 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Tripoli et al., 2022 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | First Episode Psychosis | No | No | No |

| Tylec et al., 2017 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| van Rijn et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | No | Yes (Identity) |

| van 't Wout et al., 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Villalta-Gil et al., 2013 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity, Gender) |

| Walker, 1984 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Watanuki et al., 2016 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Whittaker et al., 2001 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Wickline et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Williams et al., 2007 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | No | No | No |

| Wynn et al., 2008 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Wynn et al., 2013 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Wynn et al., 2023 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusion Disorder, Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified | Partial | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Yagci et al., 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Yamada et al., 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Article . | Task Type Effect Size Count . | SSD sample . | IQ matching . | Memory-dependant non-emotion task used? . | Close-to-ceiling task used? . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion . | Identity . | Gender . | Age . | Other . | |||||

| Addington & Addington, 1998 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Both types | No |

| Andric et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | No |

| Archer et al., 1992 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Barkhof et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Baudouin et al., 2002 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Bediou et al., 2005 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Bediou et al., 2007 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Belge et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Age, Emotion, Gender, Other) |

| Bellack et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Bigelow et al., 2006 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Brief Psychotic Disorder | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Borod et al., 1993 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Caldiroli et al., 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Calkins et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Campanella et al., 2006 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Chen et al., 2012 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | No |

| de Achaval, 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Derntl et al., 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Dickey et al., 2011 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Doop & Park, 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Other) |

| Drusch et al., 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Drusch et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Edwards et al., 2001 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Other | Partial | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Erol et al., 2013 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Other | Yes | No | No |

| Evangeli & Broks, 2000 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Identity, Other) |

| Exner et al., 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Fakra et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Feinberg et al., 1986 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Frommann et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Gee et al., 2012 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Substance Induced Psychosis | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Germine & Hooker, 2011 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | No | No | No |

| Gessler et al., 1989 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Goghari et al., 2011 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Goghari et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Goghari, & Sponheim, 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Goldenberg et al., 2012 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Gur et al., 2002 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Habel et al., 2000 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Partial | No | Yes (Age, Emotion) |

| Habel et al., 2006 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, High Schizotypy, Other | Yes | No | No |

| Habel, Chechko et al., 2010 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Habel, Koch et al., 2010 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hall et al., 2004 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hall et al., 2008 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Heimberg et al., 1992 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Hooker & Park 2002 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Identity) |

| Horan et al., 2003 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Johnston et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Kerr & Neale, 1993 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Kosmidis et al., 2007 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Kucharska-Pietura et al., 2005 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Kucharska-Pietura, Mortimer et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Kucharska-Pietura, Tylec et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Kuo et al., 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Lee et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Li et al., 2010 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Identity) |

| Linden et al., 2010 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Maat et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Mamah et al., 2021 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Martin et al., 2005 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Martinez-Dominguez et al., 2015 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Meijer et al., 2012 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Brief Psychotic Disorder, Other | No | No | No |

| Mier et al., 2010 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Mier et al., 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Modinos et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | No | No | No |

| Mueser et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | No |

| Novic et al., 1984 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Okada et al., 2015 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | No |

| Penn et al., 2000 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Pinkham et al., 2008 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Pinkham et al., 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | No | No |

| Pomarol-Clotet et al., 2010 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | No |

| Poreh et al., 1994 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | Yes | Yes | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Priyesh et al., 2021 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Punchaichira et al., 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Quintana et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Ramos-Loyo et al., 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| Ramos-Loyo et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| Randers et al., 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | No | No |

| Rocca et al., 2009 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Sachse et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Salem et al., 1996 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Schneider et al., 1998 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Age, Emotion) |

| Schneider et al., 2006 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Both types | No |

| Schwartz et al., 2002 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Partial | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| She et al., 2017 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion) |

| Silver et al., 2003 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | Yes | No |

| Silver et al., 2005 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | Yes | No |

| Silver et al., 2009 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Soria Bauser et al., 2012 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Spilka & Goghari, 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Tripoli et al., 2022 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | First Episode Psychosis | No | No | No |

| Tylec et al., 2017 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder | No | Yes | Yes (Identity) |

| van Rijn et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ultra/clinical high risk of psychosis | Yes | No | Yes (Identity) |

| van 't Wout et al., 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Villalta-Gil et al., 2013 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Other | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Identity, Gender) |

| Walker, 1984 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Watanuki et al., 2016 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Whittaker et al., 2001 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | Both types | Yes (Emotion, Identity) |

| Wickline et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizotypal Personality Disorder | Yes | No | No |

| Williams et al., 2007 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High Schizotypy | No | No | No |

| Wynn et al., 2008 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Wynn et al., 2013 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | No | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Wynn et al., 2023 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, Schizophreniform Disorder, Delusion Disorder, Psychotic Disorder Not Otherwise Specified | Partial | No | Yes (Emotion, Gender) |

| Yagci et al., 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

| Yamada et al., 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Schizophrenia | Yes | No | No |

Note. The Task Type Effect Size Count columns count the number of effect sizes for each task type, which may include different tasks, different samples completing each task, or a combination of the two. The IQ Matching column is labelled as “Partial” if some samples were matched for intelligence and others were not. If a close-to-ceiling task was used, the task type is listed in parentheses.

Intelligence matching was coded as matched or unmatched on a measure of global intelligence (or years of education as a proxy). Articles were coded as matched if the mean scores of SSD and community samples were not significantly different, regardless of whether matching was deliberate or incidental. Articles were coded as unmatched when samples’ scores differed significantly or if no intelligence/education measure was reported.

Tasks were coded as memory-dependent if they required participants to retain and recall previously learned information. Tasks were coded as memory-independent if they did not require memory for their completion. Memory-dependent tasks included primarily identity recognition tasks that required participants to memorize new faces, as well as tasks involving the recognition of famous faces from popular culture. Note, memory-dependent tasks always involved identity perception.

Task difficulty was coded as close-to-ceiling if the community sample scored ≥90% or not-at-ceiling if they scored below this criterion.

We defined ceiling tasks as those with ≥90% accuracy using the criteria that: (1) tasks must have high accuracy that is close to ceiling; and (2) accuracy threshold must retain enough studies to give no less than a 10:1 ratio between not-at-ceiling and close-to-ceiling effect sizes, as required for moderation analysis.139

We intended to code tasks as close-to-floor if the community sample scored ≤10% above chance performance; however, no tasks met this criterion. Task difficulty was also measured as a continuous variable via community sample accuracy (i.e., percentage of correct responses). Analyses including task difficulty were conducted on a subset of effect sizes as some articles provided insufficient data to calculate task difficulty (e.g., accuracy presented as raw scores without a total item number).

Meta-analyses

Multilevel meta-regressions were conducted using mixed linear models in the Metafor package in R.140 Effect sizes were estimated using Restricted Maximum Likelihood models. Robust Variance Estimation141 was used to account for dependency among effect sizes caused by each article contributing multiple effects. Main and interaction effects were tested via Q-tests (comparable to χ² tests of association in general linear models) which identified whether significant variability among effect sizes could be explained by main or interaction effects.142 Study procedures followed PRISMA guidelines,143 although hypotheses and analysis plans were not preregistered. Data and analysis files are available at OSF (https://osf.io/jybqr/).144 Note, supplementary material S15 includes detailed descriptions of the tasks and samples, as well as all effect size and moderator data.

To test whether SSD-related impairments were significantly larger for emotion than non-emotion tasks (H1), we examined the main effect of task type. Most moderation effects were tested via interactions between task type and the relevant moderator variable (H2a: SSD severity; H2b: intelligence matching; H2d: task difficulty). The interaction between memory dependency and task type (H2c) could not be tested since emotion tasks were never memory dependent. Instead, articles were split into subsets that used memory-dependent vs memory-independent non-emotion tasks. When articles included both, memory-independent tasks were excluded from analyses so that no sample was included in both subsets. This approach aimed to balance the number of effect sizes provided by the 2 subsets. We then tested whether SSD-related impairments were larger for emotion than non-emotion tasks in the memory-dependent and memory-independent subsets separately.

Analyses were run twice: first as simple models including only the effects and interactions of interest and then as combined models including all possible predictor variables. Combined models tested whether the effect of interest accounted for a unique portion of variance not accounted for by other predictors. Combined models could not include both task type and memory dependency due to multicollinearity between them. There were no other multicollinearity issues among predictor variables. Combined models included fewer effect sizes due to missing data for task difficulty. Most often, simple and combined models produced the same results, so simple models are reported to optimize power. When simple and combined models produced conflicting results, both are reported.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by rerunning analyses with influential outliers removed. Studentized residuals, Cook’s Distance, DFBETA values, and hat values140 were used to identify effect size and article level outliers that substantially influenced the models’ parameters (1%–7% of total cases in each model). In 1 instance, trend level results (P value = .05 to .10) became non-significant when outliers were removed so both findings are reported in text. Otherwise, results remained stable when outliers were removed, so we report models with outliers retained.

Results

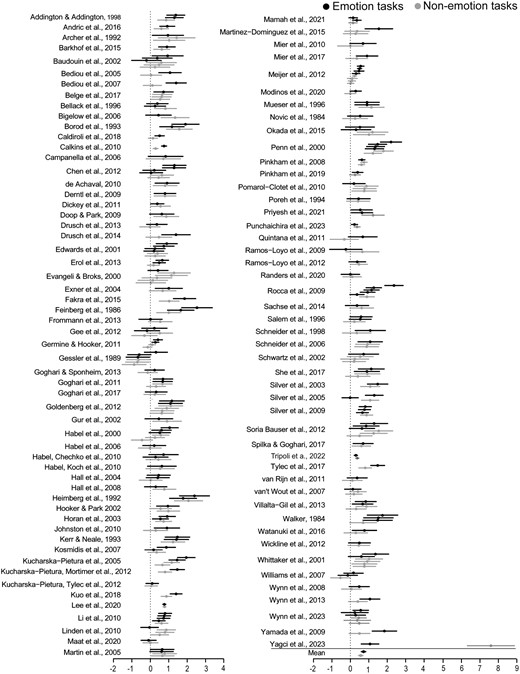

Table 2 shows the number of effect sizes, papers, and participants in each analysis and predictor variable category. Figure 2 shows effect sizes by article, for emotion and non-emotion impairments. Analyses revealed a moderate SSD-related impairment for all face tasks combined (d = 0.65, p < .001, 95% CI [0.56, 0. 74]). Effect sizes were significant for both emotion and non-emotion tasks at all levels of moderator variables, indicating there were SSD-related impairments regardless of task or study characteristics. This pattern is typical of SSD performance across cognitive tasks22–24 and demonstrates why significantly lower scores in SSD samples (relative to comparison samples) alone should not be interpreted as evidence for differential impairments. Therefore, we focus on the relative size of SSD-related impairments across task types, not the presence/absence of them. We found considerable heterogeneity among effect sizes (I2 range: 71%–85%, p ≤ .001) indicating SSD-related impairments vary substantially across tasks. This heterogeneity warrants moderation analysis145 to determine which task features impact the size of impairments.

Number of articles, effect sizes and participants in analyses and variable levels

| Variable . | N articles . | N effect sizes . | N SSD participants . | N comparison participants . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Analyses Total | 103 | 313 | 8036 | 6951 |

| Task Type | ||||

| Emotion | 103 | 163 | 7940 | 6883 |

| Control | 103 | 150 | 7973 | 6904 |

| Identity | 75 | 107 | 7128 | 6077 |

| Age | 14 | 20 | 450 | 408 |

| Gender | 15 | 18 | 623 | 605 |

| Face Orientation | 1 | 1 | 22 | 16 |

| Eye Gaze Direction | 2 | 2 | 42 | 42 |

| Mixed | 2 | 2 | 38 | 38 |

| SSD Severity | ||||

| High-severity | 90 | 272 | 5613 | 6245 |

| Schizophrenia | 69 | 204 | 3285 | 2982 |

| Schizoaffective Disorder | 3 | 7 | 69 | 616 |

| Mixed Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective Disorder | 18 | 48 | 2038 | 2740 |

| Combined High- and Low-severity | 5 | 12 | 157 | 150 |

| Low-severity | 15 | 41 | 1080 | 1978 |

| High schizotypy | 3 | 9 | 252 | 276 |

| Schizotypal Personality Disorder | 2 | 4 | 75 | 93 |

| Early psychosis | 4 | 10 | 134 | 734 |

| High risk for psychosis | 4 | 10 | 408 | 249 |

| Substance-induced psychosis | 1 | 4 | 20 | 14 |

| Mixed | 2 | 4 | 176 | 627 |

| Intelligence Matching | ||||

| Matched | 58 | 163 | 1730 | 1667 |

| Not matched | 49 | 150 | 6346 | 5353 |

| Task Difficulty | ||||

| Task Difficulty Analyses Total | 93 | 282 | 699 | 6863 |

| Close-to-ceiling | 42 | 87 | 1272 | 1144 |

| Not-at-ceiling | 81 | 195 | 6564 | 5870 |

| Memory Dependency | ||||

| Memory-dependent subgroup | 32 | 96 | 3535 | 2735 |

| Memory-independent subgroup | 72 | 207 | 4539 | 4211 |

| Variable . | N articles . | N effect sizes . | N SSD participants . | N comparison participants . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Analyses Total | 103 | 313 | 8036 | 6951 |

| Task Type | ||||

| Emotion | 103 | 163 | 7940 | 6883 |

| Control | 103 | 150 | 7973 | 6904 |

| Identity | 75 | 107 | 7128 | 6077 |

| Age | 14 | 20 | 450 | 408 |

| Gender | 15 | 18 | 623 | 605 |

| Face Orientation | 1 | 1 | 22 | 16 |

| Eye Gaze Direction | 2 | 2 | 42 | 42 |

| Mixed | 2 | 2 | 38 | 38 |

| SSD Severity | ||||

| High-severity | 90 | 272 | 5613 | 6245 |

| Schizophrenia | 69 | 204 | 3285 | 2982 |

| Schizoaffective Disorder | 3 | 7 | 69 | 616 |

| Mixed Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective Disorder | 18 | 48 | 2038 | 2740 |

| Combined High- and Low-severity | 5 | 12 | 157 | 150 |

| Low-severity | 15 | 41 | 1080 | 1978 |

| High schizotypy | 3 | 9 | 252 | 276 |

| Schizotypal Personality Disorder | 2 | 4 | 75 | 93 |

| Early psychosis | 4 | 10 | 134 | 734 |

| High risk for psychosis | 4 | 10 | 408 | 249 |

| Substance-induced psychosis | 1 | 4 | 20 | 14 |

| Mixed | 2 | 4 | 176 | 627 |

| Intelligence Matching | ||||

| Matched | 58 | 163 | 1730 | 1667 |

| Not matched | 49 | 150 | 6346 | 5353 |

| Task Difficulty | ||||

| Task Difficulty Analyses Total | 93 | 282 | 699 | 6863 |

| Close-to-ceiling | 42 | 87 | 1272 | 1144 |

| Not-at-ceiling | 81 | 195 | 6564 | 5870 |

| Memory Dependency | ||||

| Memory-dependent subgroup | 32 | 96 | 3535 | 2735 |

| Memory-independent subgroup | 72 | 207 | 4539 | 4211 |

Note. The number of articles and participants across moderator categories does not sum to the total number of articles or participants in the meta-analyses as articles and participants contributed to multiple categories. There are fewer effect sizes within the task difficulty analyses as some articles included insufficient detail to calculate task difficulty. The primary analyses total reflects the number of articles included in the primary analyses, not the number of articles extracted (n=104) as one article was included in task difficulty analyses and not the primary analyses due to overlapping participant groups across articles. The early psychosis SSD sample group includes samples defined as having schizophreniform disorder, attenuated psychosis syndrome and first-episode psychosis.

Number of articles, effect sizes and participants in analyses and variable levels

| Variable . | N articles . | N effect sizes . | N SSD participants . | N comparison participants . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Analyses Total | 103 | 313 | 8036 | 6951 |

| Task Type | ||||

| Emotion | 103 | 163 | 7940 | 6883 |

| Control | 103 | 150 | 7973 | 6904 |

| Identity | 75 | 107 | 7128 | 6077 |

| Age | 14 | 20 | 450 | 408 |

| Gender | 15 | 18 | 623 | 605 |

| Face Orientation | 1 | 1 | 22 | 16 |

| Eye Gaze Direction | 2 | 2 | 42 | 42 |

| Mixed | 2 | 2 | 38 | 38 |

| SSD Severity | ||||

| High-severity | 90 | 272 | 5613 | 6245 |

| Schizophrenia | 69 | 204 | 3285 | 2982 |

| Schizoaffective Disorder | 3 | 7 | 69 | 616 |

| Mixed Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective Disorder | 18 | 48 | 2038 | 2740 |

| Combined High- and Low-severity | 5 | 12 | 157 | 150 |

| Low-severity | 15 | 41 | 1080 | 1978 |

| High schizotypy | 3 | 9 | 252 | 276 |

| Schizotypal Personality Disorder | 2 | 4 | 75 | 93 |

| Early psychosis | 4 | 10 | 134 | 734 |

| High risk for psychosis | 4 | 10 | 408 | 249 |

| Substance-induced psychosis | 1 | 4 | 20 | 14 |

| Mixed | 2 | 4 | 176 | 627 |

| Intelligence Matching | ||||

| Matched | 58 | 163 | 1730 | 1667 |

| Not matched | 49 | 150 | 6346 | 5353 |

| Task Difficulty | ||||

| Task Difficulty Analyses Total | 93 | 282 | 699 | 6863 |

| Close-to-ceiling | 42 | 87 | 1272 | 1144 |

| Not-at-ceiling | 81 | 195 | 6564 | 5870 |

| Memory Dependency | ||||

| Memory-dependent subgroup | 32 | 96 | 3535 | 2735 |

| Memory-independent subgroup | 72 | 207 | 4539 | 4211 |

| Variable . | N articles . | N effect sizes . | N SSD participants . | N comparison participants . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Analyses Total | 103 | 313 | 8036 | 6951 |

| Task Type | ||||

| Emotion | 103 | 163 | 7940 | 6883 |

| Control | 103 | 150 | 7973 | 6904 |

| Identity | 75 | 107 | 7128 | 6077 |

| Age | 14 | 20 | 450 | 408 |

| Gender | 15 | 18 | 623 | 605 |

| Face Orientation | 1 | 1 | 22 | 16 |

| Eye Gaze Direction | 2 | 2 | 42 | 42 |

| Mixed | 2 | 2 | 38 | 38 |

| SSD Severity | ||||

| High-severity | 90 | 272 | 5613 | 6245 |

| Schizophrenia | 69 | 204 | 3285 | 2982 |

| Schizoaffective Disorder | 3 | 7 | 69 | 616 |

| Mixed Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective Disorder | 18 | 48 | 2038 | 2740 |

| Combined High- and Low-severity | 5 | 12 | 157 | 150 |

| Low-severity | 15 | 41 | 1080 | 1978 |

| High schizotypy | 3 | 9 | 252 | 276 |

| Schizotypal Personality Disorder | 2 | 4 | 75 | 93 |

| Early psychosis | 4 | 10 | 134 | 734 |

| High risk for psychosis | 4 | 10 | 408 | 249 |

| Substance-induced psychosis | 1 | 4 | 20 | 14 |

| Mixed | 2 | 4 | 176 | 627 |

| Intelligence Matching | ||||

| Matched | 58 | 163 | 1730 | 1667 |

| Not matched | 49 | 150 | 6346 | 5353 |

| Task Difficulty | ||||

| Task Difficulty Analyses Total | 93 | 282 | 699 | 6863 |

| Close-to-ceiling | 42 | 87 | 1272 | 1144 |

| Not-at-ceiling | 81 | 195 | 6564 | 5870 |

| Memory Dependency | ||||

| Memory-dependent subgroup | 32 | 96 | 3535 | 2735 |

| Memory-independent subgroup | 72 | 207 | 4539 | 4211 |

Note. The number of articles and participants across moderator categories does not sum to the total number of articles or participants in the meta-analyses as articles and participants contributed to multiple categories. There are fewer effect sizes within the task difficulty analyses as some articles included insufficient detail to calculate task difficulty. The primary analyses total reflects the number of articles included in the primary analyses, not the number of articles extracted (n=104) as one article was included in task difficulty analyses and not the primary analyses due to overlapping participant groups across articles. The early psychosis SSD sample group includes samples defined as having schizophreniform disorder, attenuated psychosis syndrome and first-episode psychosis.

Forest plot. Note. Effect sizes are presented for each task and are grouped by article. Effects within each article may sample the same or different participants, or a mix of both. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

H1: Are SSD-related Impairments Larger for Emotion vs Non-emotion Face Perception Tasks?

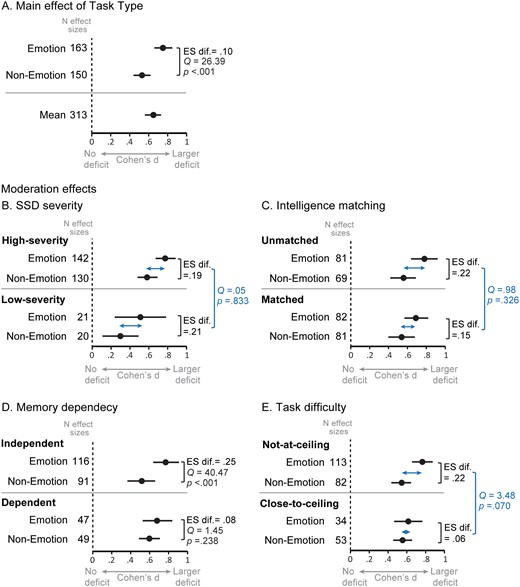

Critically, we found SSD-related impairments were significantly larger for emotion (d = 0.74, p < .001, 95% CI [0.64, 0.83]) than non-emotion tasks (d = 0.55, P < .001, 95% CI [0.45, 0.64]), as demonstrated by a significant main effect of task type (Q = 26.39, p < .001, k = 313; figure 3A). This pattern indicates that people with SSD have a differential impairment in emotion face perception.

Effects of task type and moderator variables on SSD-related impairments. Note. All effect sizes are significantly different from zero. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. The large confidence intervals in low-severity SSD samples reflect the small sample size and varied magnitude of deficits found across studies, likely due to sample diversity. In Fig 3A and 3D. the Q statistic tests the difference in effect size between emotion and non-emotion tasks. In Figs 3B., 3C., and 3E. the Q statistic tests the interaction between the moderator variable and task type.

H2a: Does SSD Severity Moderate the Size of the Differential Emotion Impairment?

When emotion and non-emotion tasks were combined, high-severity SSD samples showed significantly larger face perception impairments (d = 0.69, p < .001, 95% CI [0.59, 0.78]) than low-severity samples (d = 0.39, p = .001, 95% CI [0.20, 0.59]; Q = 8.16, p = .020, k = 313). Note, this difference approached significance in the combined model (Q = 5.25, p = .060, k = 282), indicating shared variance with other moderators. Critically however, there was no significant interaction between SSD severity and task type (Q = 0.046, p = .833, k = 313), indicating that the difference in magnitude between the emotion and non-emotion impairments was comparable for high-severity (d difference = 0.19) and low-severity SSD (d difference = 0.21; figure 3B). This finding demonstrates that the differential emotion impairment is a feature of SSD populations regardless of symptom severity.

H2b: Does Intelligence Matching Moderate the Size of the Differential Emotion Impairment?

While face perception impairments were numerically smaller when SSD and comparison samples were matched for intelligence (d = 0.62, p < .001, 95% CI [0.51, 0.74]) than when they were not (d = 0.68, p < .001, 95% CI [0.54, 0.81]), this difference was not statistically significant (Q = 0.38, p = .539, k = 313). This pattern indicates that matching samples for intelligence may not substantially influence the magnitude of SSD-related face perception impairments.