-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Liron Saporta-Wiesel, Ruth Feldman, Linda Levi, Michael Davidson, Shimon Burshtein, Ruben Gur, Orna Zagoory-Sharon, Revital Amiaz, Jinyoung Park, John M Davis, Mark Weiser, Intranasal Oxytocin Combined With Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia: An Add-on Randomized Controlled Trial, Schizophrenia Bulletin Open, Volume 5, Issue 1, January 2024, sgae022, https://doi.org/10.1093/schizbullopen/sgae022

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Some but not other studies on oxytocin for schizophrenia, particularly those using a higher dose, indicate that oxytocin improves negative symptoms of schizophrenia. We performed an add-on randomized controlled trial to examine the effect of high-dose oxytocin, social skills training, and their combination in the treatment of negative symptoms and social dysfunction in schizophrenia. Fifty-one subjects with schizophrenia were randomized, employing a two-by-two design: intranasal oxytocin (24 IU X3/day) or placebo, and social skills training or supportive psychotherapy, for 3 weeks. The primary outcome was the difference in the total score from baseline to end-of-study of a semi-structured interview which assessed patients’ social interactions in 3 scenarios: sharing a positive experience, sharing a conflict, and giving support when the experimenter shared a conflict. The interactions were scored using the Coding Interactive Behavior Manual (CIB), clinical symptoms were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). No significant difference was found between groups in the total CIB or PANSS scores. The majority of comparisons in the different social interactions between oxytocin and placebo, and between social skills training vs supportive psychotherapy, were also nonsignificant. Social skills training reduced blunted affect and gaze. In post-hoc analyses of the support interaction, oxytocin improved synchrony and decreased tension, while in the positive interaction it improved positive affect and avoidance. None of these findings remained significant when controlling for multiple comparisons. In conclusion, oxytocin did not influence participants’ social behavior, and was not effective in improving the symptoms of schizophrenia.

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01598623

Introduction

Social disability is a hallmark of schizophrenia and considered part of the negative symptoms of the illness. Many patients have social abnormalities in early childhood,1 years before their first episode, which are predictive of the course and outcome of the illness.2,3 There are no effective pharmacological treatments for negative symptoms or social dysfunction.4–6

Oxytocin is a 9 amino-acid peptide synthesized in the hypothalamus, which acts both peripherally as a hormone and as a neurotransmitter in the brain. As a neurotransmitter, it has been found to play a key role in regulating mammalian, including human, social affiliation, such as sexual behavior and mother-infant and adult-adult pair-bond formation.7–10 Research in healthy humans has shown that intranasal administration of oxytocin impacts multiple social and emotional behaviors in a prosocial, pro-affiliative way, leading to an increase in trust, empathy, and eye contact.11–17 Studies on autism, a neurodevelopment disorder particularly linked with social dysfunction, have been equivocal.18–23

These observations suggest that oxytocin has the potential to be an effective prosocial intervention for schizophrenia as well. Initially, a few studies showed improvement in schizophrenia patients who received oxytocin,24–28 but subsequent studies failed to replicated these findings,29–35 meta-analyzed in Martins et al and Zheng et al.22,36 Those studies which found the clearest evidence for efficacy used a high dose of oxytocin, above 50 IU/day24,26; consequently our study evaluated oxytocin at 72 IU/day.

Some authors have hypothesized that combining medications with psychosocial intervention might help in the treatment of schizophrenia. Similar notions have been expressed regarding the use of cognition-enhancing medication, suggesting that patients who receive compounds that putatively enhance cognition should be treated with cognitive remediation at the same time.37–41 Ford and Young note that oxytocin increases the salience of social stimuli, increasing the signal-to-noise ratio of social information, and have specifically recommended that trials of oxytocin in autism be carried out combining behavioral therapy with oxytocin.42

Based on this concept, we administered oxytocin combined with social skills training focused on the key domains of social behavior impaired in schizophrenia, which are postulated to be improved by oxytocin. We used placebo as a control for the oxytocin and supportive psychotherapy as a control for the social skills training, and performed an add-on, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to examine the effects of intranasal oxytocin combined with social skills training in patients with schizophrenia patients.

Three main hypotheses guided the current study: (1) intranasal oxytocin at a high dose would be more beneficial compared to placebo in improving schizophrenia patients’ prosocial behavior and psychopathology; (2) social skills training would be more beneficial compared to supportive psychotherapy; (3) the combined effects of intranasal oxytocin together with the social skills training will be synergetic and will exceed the effects of each intervention on its own in improving prosocial behavior and negative symptoms.

Methods

Study Subjects

Participants were outpatients recruited from the Zachai Division of Psychiatry in the Sheba Medical Center in Ramat Gan, Israel and by advertisements in rehabilitation centers, notice boards, and the internet.

The inclusion criteria were current DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders43; 18–65 years of age; Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score greater than 55; social dysfunction as defined by a score of 4 (moderate) or higher on at least 1 or more of the following PANSS negative items: emotional withdrawal, poor rapport, or passive-apathetic social withdrawal. Subjects had to be on the same antipsychotic medication for 2 weeks before randomization. Adjunctive treatment with other psychotropics was allowed, provided that patients had been on the medication for at least 2 weeks prior to entry into the screening phase of the study. Changes in concomitant medications, both psychiatric and other, were allowed and recorded.

The study was approved by the local IRB, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01598623).

Study Design

This study utilized a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel, 2 × 2, double-blind, add-on design. Social skills training or supportive psychological therapy was administered by BA-level psychologists, 3 times a week, for the 3-week study period, for a total of 9 sessions. At baseline, a videotaped interview assessing the interaction between the subject and the experimenter was performed. Subjects were assessed once a week using the PANSS.44 At this weekly visit, and study medication inhalers were replaced. At the end of the 3 week period, subjects participated in a final, end-of-study visit during which all assessments were repeated.

Study Medication

Subjects received daily intranasal oxytocin (Syntocinon Spray, Novartis) or intranasal placebo (matching vials containing saline) for a period of 3 weeks. Based on the previous studies showing efficacy,24,27 oxytocin was dosed at 24 IU 3 times a day. Subjects received 2 inhalers of study medication during their weekly visit and returned the used inhalers. Due to the potential for loss of drug dripping out through the nares if not properly administered, subjects were instructed how to self-administer the medication, spraying six 0.1 ml insufflations while tilting the head slightly back. Subjects were instructed to administer study medication 3 times a day: morning, noon, and evening, before meals. The daily dose was divided into 3 times a day since the literature shows that oxytocin’s levels go down back to baseline levels after approximately 7 h,45,46 thus the need to take repeated doses throughout the day.

On days when social skills training or psychotherapy was given, subjects were given 1 oxytocin dose 30 min prior to the session.

Psychological Intervention

The social skills training was comprised of 9 sessions. The first 5 sessions were based on the relevant sessions from the Social Cognition and Interaction Training,47 which focus on understanding emotions. In these sessions, subjects were taught to define their emotions, and to link facial expressions to the emotions they portray. The last 4 sessions were from the Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia,48 focusing on starting conversation, listening to others, expressing positive as well as negative feelings. The training was administered individually rather than in a group format because different subjects were recruited at different times.

Supportive psychotherapy was administered as a control condition for the social skills training, to account for the nonspecific effects of therapist contact and interest, social interaction, and support. In these supportive psychotherapy sessions, subjects were encouraged to bring any particular topic to therapy, however, socially relevant topics were not addressed. Subjects underwent social skills training or supportive psychotherapy 3 times a week during the in-person clinical visits throughout the 3-week trial period. Subjects were instructed to administer study medication (oxytocin/placebo) 30 min before the session started. The psychological intervention was performed by 3 trained therapists, who followed a study-specific protocol for the social skills training. No formal training was performed.

Social Interaction Measures

Before and after the 3-week oxytocin/placebo administration subjects were videotaped in 3 interaction paradigms developed for the adult version of the Coding Interactive Behavior (CIB),49 consistent with prior research on the CIB in adolescents and adults.50–56 These included: (1) a “positive interaction” in which subjects were asked to recall a positive event or experience that occurred in their lives; (2) a “conflict interaction” in which subjects were asked to talk about a conflict that occurred in their lives; (3) a “support interaction” in which the experimenter shared an incident that occurred in her life (conflict at work or with a family member). Subjects were asked to share their feelings and opinions in light of that story. Interactions were coded off-line by blinded raters, using the CIB,49 a well-validated system for coding dyadic interactions. The CIB is a global rating system of dyadic interactions that includes multiple scales, each coded from 1 (low) to 5 (high) and with versions for newborns, infants, children, adolescents, and adults. The system has shown good psychometric qualities on multiple studies across a wide range of ages, cultures, normative, and psychiatric conditions.57 The adult version of the CIB contains multiple scales that address the individual’s behavior (eg, gaze, expressed affect, and anxiety) and scales addressing the nature of the dialogue between patient and experimenter (eg, reciprocity, synchrony, and fluency). The parameters were rated on a scale of 1 (low) to 5 (high), with 0.5-point intervals. Reliability, rated as agreement of both raters on 10 paradigms averaged 91.74%.

Data Analysis

The primary outcome measure was the change from baseline in the total score of the structured assessment of social interaction (CIB) in oxytocin, compared with placebo on all patients. Total score was the sum of all prosocial item, minus the sum of items that were not prosocial. Secondary outcome measures included change from baseline in the CIB total score in the oxytocin vs placebo groups, with and without social skills training, and social skills training vs supportive psychotherapy, with or without oxytocin. Changes from baseline in the total PANSS and PANSS subscales in all groups were additional secondary outcome measures.

A mixed-effect model with repeated measures (MMRM) was performed with participants as a random effect. The main effect and the interaction effect of medication (oxytocin = 1 vs placebo = 0) and psychological treatment (social skills training = 1 vs supportive psychotherapy = 0) were tested for every outcome. Specifically, (1) the medication effect (oxytocin vs placebo), (2) the psychological treatment effect (social skills training vs supportive psychotherapy), and (3) the effect of the combinations of oxytocin and psychological therapy (oxytocin/social skills training, oxytocin/supportive psychotherapy, placebo/social skills training, placebo/supportive psychotherapy) were examined. To prevent spurious associations from multiple comparisons, the P values were adjusted using Bonferroni correction.

Separate analyses were performed for the CIB variables individually. An exploratory factor analysis with the principal axis factoring method was used to identify the underlying dimensions of CIB items. A 5-factor structure was selected, explaining 67% of the total variance. Factor scores were calculated using regression-based weights for each factor and used in the MMRM as outcome variables. The factor analysis was done on the CIB for all the subjects to identify its dimensions. We used a MMRM to analyze the direct effect of oxytocin, the direct effect of social skills training, or their interactions. Similar analyses were performed for all secondary measures, including PANSS total score, PANSS subscales, and PANSS factor scores.58 R version 4.1.0 was used for the analysis.

Results

There were no significant differences between the 4 groups on baseline demographic and clinical variables (table 1).

| Measure . | Oxytocin/Social Cognitive and Skills Training . | Oxytocin/Supportive Psychotherapy . | Placebo/Social Cognitive and Skills Training . | Placebo/Supportive Psychotherapy . | Overall . | Statistic . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 10/1 | 11/0 | 8/4 | 10/3 | 39/8 | χ² (3) = 5.34 P = .14 |

| Age (years ± SD) | 39.45 ± 11.51 | 33.09 ± 9.72 | 37.83 ± 11.91 | 36.3 ± 8.33 | 36.68 ± 10.33 | F(3,43) = 0.75 P = .52 |

| Marital status (single/married/divorced) | 9/2/0 | 8/2/1 | 10/0/2 | 13/0/0 | 40/4/3 | χ² (6) = 8.74 P = .18 |

| Education in years (mean ± SD) | 10.45 ± 5.59 | 11.55 ± 4.15 | 11.67 ± 2.27 | 12 ± 3.91 | 11.45 ± 4.01 | F(3,43) = 0.3 P = .82 |

| Diagnosis (Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective) | 10/1 | 10/1 | 12/0 | 9/4 | 41/6 | χ² (3) = 5.8 P = .12 |

| Age of onset | 24 ± 8.79 | 22.5 ± 6.54 | 24.67 ± 7.11 | 23.85 ± 4.94 | 23.78 ± 6.72 | F(3,43) = 0.19 P = .89 |

| Duration of illness (mean ± SD) | 15.45 ± 6.23 | 10.59 ± 10.28 | 13.16 ± 11.18 | 12.46 ± 7.63 | 12.9 ± 8.91 | F(3,43) = 0.54 P = .65 |

| PANSS Total at Baseline | 64 ± 14.62 | 69.73 + 16.96 | 66.17 + 10.86 | 63.92 + 10.35 | 65.87 ± 13.06 | F(3,43) = 0.47 P = .7 |

| PANSS Positive at Baseline | 12.73 ± 5.12 | 13.09 ± 4.94 | 12 ± 3.51 | 12.62 ± 3.15 | 12.6 ± 4.09 | F(3,43) = 0.13 P = .93 |

| PANSS Negative at Baseline | 19.55 ± 5.64 | 22.73 ± 6.95 | 23 ± 4.11 | 20.54 ± 3.97 | 21.45 ± 5.26 | F(3,43) = 1.18 P = .32 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology at Baseline | 31.73 ± 6.98 | 33.91 ± 9.02 | 31.17 ± 6.74 | 29.77 ± 5.38 | 31.55 ± 7 | F(3,43) = 0.69 P = .55 |

| Measure . | Oxytocin/Social Cognitive and Skills Training . | Oxytocin/Supportive Psychotherapy . | Placebo/Social Cognitive and Skills Training . | Placebo/Supportive Psychotherapy . | Overall . | Statistic . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 10/1 | 11/0 | 8/4 | 10/3 | 39/8 | χ² (3) = 5.34 P = .14 |

| Age (years ± SD) | 39.45 ± 11.51 | 33.09 ± 9.72 | 37.83 ± 11.91 | 36.3 ± 8.33 | 36.68 ± 10.33 | F(3,43) = 0.75 P = .52 |

| Marital status (single/married/divorced) | 9/2/0 | 8/2/1 | 10/0/2 | 13/0/0 | 40/4/3 | χ² (6) = 8.74 P = .18 |

| Education in years (mean ± SD) | 10.45 ± 5.59 | 11.55 ± 4.15 | 11.67 ± 2.27 | 12 ± 3.91 | 11.45 ± 4.01 | F(3,43) = 0.3 P = .82 |

| Diagnosis (Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective) | 10/1 | 10/1 | 12/0 | 9/4 | 41/6 | χ² (3) = 5.8 P = .12 |

| Age of onset | 24 ± 8.79 | 22.5 ± 6.54 | 24.67 ± 7.11 | 23.85 ± 4.94 | 23.78 ± 6.72 | F(3,43) = 0.19 P = .89 |

| Duration of illness (mean ± SD) | 15.45 ± 6.23 | 10.59 ± 10.28 | 13.16 ± 11.18 | 12.46 ± 7.63 | 12.9 ± 8.91 | F(3,43) = 0.54 P = .65 |

| PANSS Total at Baseline | 64 ± 14.62 | 69.73 + 16.96 | 66.17 + 10.86 | 63.92 + 10.35 | 65.87 ± 13.06 | F(3,43) = 0.47 P = .7 |

| PANSS Positive at Baseline | 12.73 ± 5.12 | 13.09 ± 4.94 | 12 ± 3.51 | 12.62 ± 3.15 | 12.6 ± 4.09 | F(3,43) = 0.13 P = .93 |

| PANSS Negative at Baseline | 19.55 ± 5.64 | 22.73 ± 6.95 | 23 ± 4.11 | 20.54 ± 3.97 | 21.45 ± 5.26 | F(3,43) = 1.18 P = .32 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology at Baseline | 31.73 ± 6.98 | 33.91 ± 9.02 | 31.17 ± 6.74 | 29.77 ± 5.38 | 31.55 ± 7 | F(3,43) = 0.69 P = .55 |

| Measure . | Oxytocin/Social Cognitive and Skills Training . | Oxytocin/Supportive Psychotherapy . | Placebo/Social Cognitive and Skills Training . | Placebo/Supportive Psychotherapy . | Overall . | Statistic . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 10/1 | 11/0 | 8/4 | 10/3 | 39/8 | χ² (3) = 5.34 P = .14 |

| Age (years ± SD) | 39.45 ± 11.51 | 33.09 ± 9.72 | 37.83 ± 11.91 | 36.3 ± 8.33 | 36.68 ± 10.33 | F(3,43) = 0.75 P = .52 |

| Marital status (single/married/divorced) | 9/2/0 | 8/2/1 | 10/0/2 | 13/0/0 | 40/4/3 | χ² (6) = 8.74 P = .18 |

| Education in years (mean ± SD) | 10.45 ± 5.59 | 11.55 ± 4.15 | 11.67 ± 2.27 | 12 ± 3.91 | 11.45 ± 4.01 | F(3,43) = 0.3 P = .82 |

| Diagnosis (Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective) | 10/1 | 10/1 | 12/0 | 9/4 | 41/6 | χ² (3) = 5.8 P = .12 |

| Age of onset | 24 ± 8.79 | 22.5 ± 6.54 | 24.67 ± 7.11 | 23.85 ± 4.94 | 23.78 ± 6.72 | F(3,43) = 0.19 P = .89 |

| Duration of illness (mean ± SD) | 15.45 ± 6.23 | 10.59 ± 10.28 | 13.16 ± 11.18 | 12.46 ± 7.63 | 12.9 ± 8.91 | F(3,43) = 0.54 P = .65 |

| PANSS Total at Baseline | 64 ± 14.62 | 69.73 + 16.96 | 66.17 + 10.86 | 63.92 + 10.35 | 65.87 ± 13.06 | F(3,43) = 0.47 P = .7 |

| PANSS Positive at Baseline | 12.73 ± 5.12 | 13.09 ± 4.94 | 12 ± 3.51 | 12.62 ± 3.15 | 12.6 ± 4.09 | F(3,43) = 0.13 P = .93 |

| PANSS Negative at Baseline | 19.55 ± 5.64 | 22.73 ± 6.95 | 23 ± 4.11 | 20.54 ± 3.97 | 21.45 ± 5.26 | F(3,43) = 1.18 P = .32 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology at Baseline | 31.73 ± 6.98 | 33.91 ± 9.02 | 31.17 ± 6.74 | 29.77 ± 5.38 | 31.55 ± 7 | F(3,43) = 0.69 P = .55 |

| Measure . | Oxytocin/Social Cognitive and Skills Training . | Oxytocin/Supportive Psychotherapy . | Placebo/Social Cognitive and Skills Training . | Placebo/Supportive Psychotherapy . | Overall . | Statistic . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 10/1 | 11/0 | 8/4 | 10/3 | 39/8 | χ² (3) = 5.34 P = .14 |

| Age (years ± SD) | 39.45 ± 11.51 | 33.09 ± 9.72 | 37.83 ± 11.91 | 36.3 ± 8.33 | 36.68 ± 10.33 | F(3,43) = 0.75 P = .52 |

| Marital status (single/married/divorced) | 9/2/0 | 8/2/1 | 10/0/2 | 13/0/0 | 40/4/3 | χ² (6) = 8.74 P = .18 |

| Education in years (mean ± SD) | 10.45 ± 5.59 | 11.55 ± 4.15 | 11.67 ± 2.27 | 12 ± 3.91 | 11.45 ± 4.01 | F(3,43) = 0.3 P = .82 |

| Diagnosis (Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective) | 10/1 | 10/1 | 12/0 | 9/4 | 41/6 | χ² (3) = 5.8 P = .12 |

| Age of onset | 24 ± 8.79 | 22.5 ± 6.54 | 24.67 ± 7.11 | 23.85 ± 4.94 | 23.78 ± 6.72 | F(3,43) = 0.19 P = .89 |

| Duration of illness (mean ± SD) | 15.45 ± 6.23 | 10.59 ± 10.28 | 13.16 ± 11.18 | 12.46 ± 7.63 | 12.9 ± 8.91 | F(3,43) = 0.54 P = .65 |

| PANSS Total at Baseline | 64 ± 14.62 | 69.73 + 16.96 | 66.17 + 10.86 | 63.92 + 10.35 | 65.87 ± 13.06 | F(3,43) = 0.47 P = .7 |

| PANSS Positive at Baseline | 12.73 ± 5.12 | 13.09 ± 4.94 | 12 ± 3.51 | 12.62 ± 3.15 | 12.6 ± 4.09 | F(3,43) = 0.13 P = .93 |

| PANSS Negative at Baseline | 19.55 ± 5.64 | 22.73 ± 6.95 | 23 ± 4.11 | 20.54 ± 3.97 | 21.45 ± 5.26 | F(3,43) = 1.18 P = .32 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology at Baseline | 31.73 ± 6.98 | 33.91 ± 9.02 | 31.17 ± 6.74 | 29.77 ± 5.38 | 31.55 ± 7 | F(3,43) = 0.69 P = .55 |

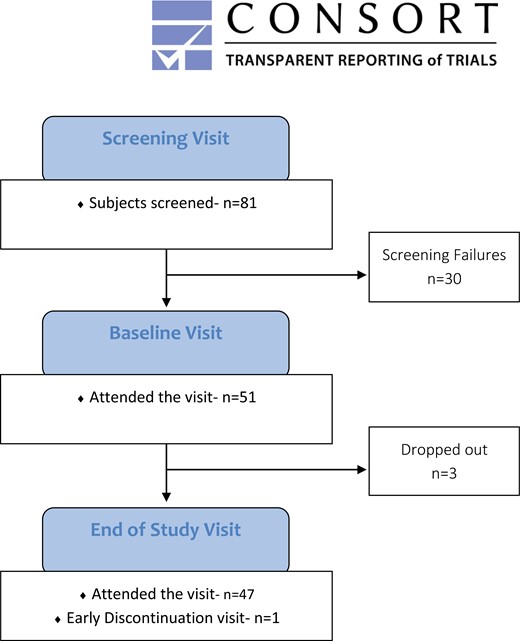

Eighty-one subjects with schizophrenia were screened, 51 were randomized, and 47 completed the 3-week study. One of the subjects who dropped out agreed to arrive for an early discontinuation visit. Since she completed 16 days of the study, these visits were included in the analysis, leaving 3 dropouts (see CONSORT diagram, figure 1).

Factor analysis of the CIB revealed 2 major factor and 3 minor factors (see web supplement—Section 2.1): Factor 1 (Synergy) had high loading with higher scores on synchrony (factor loading = 0.91), persistence (0.83), reciprocity (0.72), fluency (0.66), acknowledgment (0.64), and motivation (0.44), together with negative scores for constriction (0.73) and withdrawal (−0.42). This factor reflects the main prosocial dimension of the CIB. Factor 2 (Elaboration) had high loading on initiative (0.77), elaboration (0.79), alertness (0.59), patient leading the conversation (0.64), and motivation (0.32), with negative scores for blunted affect (−0.59) and the experimenter leading the conversation (−0.69). Factor 3 (Tension) had high loading on tension (0.86), as well as lower loading on anxiety (0.39), criticism (0.32), negative affect (0.34), and persistence (0.43), with less gaze (−0.45) and less reciprocity (−0.33). Factor 4 (Withdrawal) had high loading on withdrawal (0.55) and silence (0.42), and decreased intrusiveness (−0.67). Factor 5 (Positive affect and mismatch of affect) had high loading on positive (0.85) or mismatched affect (0.77).

The Effect of Oxytocin and Social Skills Training on Total CIB Score

A mixed-effect model was performed to test the effect of oxytocin, social skills training, or the combination of both treatments on the change of the total CIB score over time, our primary hypothesis. Although oxytocin alone (coefficient 0.59, P = .39), and social skills training alone (coefficient 0.46, P = .5) directionally increased total score, this difference was not statistically significant. Oxytocin increased CIB Total in the supportive psychotherapy group (coefficient −1.11, P = .43) but this was not significant. See figure 2, table 2, and web supplement.

Two-way Complete Model for Oxytocin, Social Skills Training or Both for CIB and PANSS Outcomes

| . | 1. Two-way Complete Model . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors (Interaction With Time) . | Effect of Oxytocin . | Effect of Social Treatment . | Interaction Effect of Oxytocin and Social Treatment . | ||||||

| Outcomes . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . |

| CIB Total Score | |||||||||

| Individual items | |||||||||

| Acknowledgment | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.35) | .31 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.19, 0.24) | .82 | 1.00 | −0.08 (−0.40, 0.25) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Alertness | 0.15 (−0.07, 0.37) | .20 | 1.00 | 0.17 (−0.04, 0.38) | .13 | 1.00 | −0.33 (−0.64, −0.01) | .06 | 1.00 |

| Anger | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.08) | .80 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.05, 0.09) | .56 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.16 , 0.05) | .36 | 1.00 |

| Anxiety | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.16) | .42 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.17) | .27 | 1.00 | −0.17 (−0.33, −0.01) | .05 | 1.00 |

| Avoidance | 0.07 (0.00, 0.14) | .05 | 1.00 | 0.07 (0.00, 0.13) | .05 | 1.00 | −0.14 (−0.24, −0.05) | .01 | .18 |

| Blunt Affect | −0.04 (−0.16, 0.08) | .55 | 1.00 | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.01) | .04 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.13, 0.22) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Constriction | −0.13 (−0.30, 0.04) | .16 | 1.00 | −0.08 (−0.24, 0.08) | .35 | 1.00 | 0.12 (−0.12, 0.36) | .36 | 1.00 |

| Criticism | −0.08 (−0.18, 0.02) | .16 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.16, 0.03) | .21 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.06, 0.23) | .28 | 1.00 |

| Detachment | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.06) | .26 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | .43 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | .72 | 1.00 |

| Elaboration | 0.09 (−0.11, 0.30) | .40 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.20, 0.19) | .96 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.34, 0.24) | .75 | 1.00 |

| Fluency | 0.15 (−0.01, 0.31) | .08 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.06, 0.24) | .24 | 1.00 | −0.15 (−0.37, 0.08) | .23 | 1.00 |

| Gaze | −0.05 (−0.27, 0.16) | .63 | 1.00 | 0.19 (−0.01, 0.39) | .08 | 1.00 | 0.07 (−0.24, 0.37) | .67 | 1.00 |

| Hostility | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.06) | .18 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.03, 0.03) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.01) | .11 | 1.00 |

| Initiation | 0.24 (−0.06, 0.54) | .14 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.19, 0.38) | .54 | 1.00 | −0.27 (−0.70, 0.16) | .23 | 1.00 |

| Instrusiveness | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.04) | .31 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.08) | .88 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.07, 0.15) | .52 | 1.00 |

| Therapist leads | −0.01 (−0.17, 0.16) | .93 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.16, 0.15) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.07 (−0.30, 0.16) | .58 | 1.00 |

| Patient leads | 0.05 (−0.09, 0.20) | .47 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.12, 0.16) | .78 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.21, 0.20) | .96 | 1.00 |

| Mismatch Affect | 0.03 (−0.05, 0.11) | .44 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.11) | .42 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.06) | .34 | 1.00 |

| Motivation | 0.05 (−0.13, 0.24) | .58 | 1.00 | 0.15 (−0.02, 0.32) | .11 | 1.00 | −0.25 (−0.51, 0.01) | .08 | 1.00 |

| Negative Affect | −0.19 (−0.39, 0.00) | .06 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.16, 0.21) | .80 | 1.00 | 0.13 (−0.15, 0.40) | .39 | 1.00 |

| Positive Affect | 0.13 (0.00, 0.26) | .06 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.06, 0.19) | .33 | 1.00 | −0.18 (−0.37, 0.01) | .07 | 1.00 |

| Persistence | −0.05 (−0.20, 0.09) | .49 | 1.00 | −0.10 (−0.24, 0.04) | .19 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.18, 0.25) | .75 | 1.00 |

| Reciprocity | 0.05 (−0.10, 0.20) | .51 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.10, 0.18) | .62 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.26, 0.16) | .63 | 1.00 |

| Silence | 0.00 (−0.10, 0.10) | .93 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.11) | .73 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.11, 0.18) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Synchrony | 0.10 (−0.06, 0.27) | .25 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.09, 0.22) | .44 | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.36, 0.11) | .32 | 1.00 |

| Tension | −0.11 (−0.24, 0.01) | .10 | 1.00 | −0.10 (−0.22, 0.02) | .13 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.11, 0.26) | .43 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal | 0.00 (−0.14, 0.14) | .99 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.14 , 0.12) | .89 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.19, 0.21) | .95 | 1.00 |

| Factors | |||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.11 (−0.15, 0.37) | .41 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.15, 0.33) | .49 | 1.00 | −0.15 (−0.52, 0.21) | .43 | 1.00 |

| Initiation | 0.14 (−0.09, 0.37) | .25 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.17, 0.26) | .70 | 1.00 | −0.02 (−0.35, 0.31) | .90 | 1.00 |

| Tension | −0.21 (−0.47, 0.04) | .12 | .60 | −0.15 (−0.40, 0.09) | .23 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.27, 0.46) | .63 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal | 0.01 (−0.26, 0.28) | .95 | 1.00 | −0.13 (−0.38, 0.13) | .35 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.30, 0.47) | .69 | 1.00 |

| Positive Affect | 0.28 (0.08, 0.49) | .01 | .06 | 0.19 (−0.00, 0.39) | .07 | .33 | −0.36 (−0.66, −0.07) | .02 | .11 |

| . | 1. Two-way Complete Model . | ||||||||

| Predictors (Interaction With Time) . | Oxytocin . | Social Treatment . | Social Treatment × Oxytocin . | ||||||

| Outcomes . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . |

| PANSS Total | 0.55 (−1.71, 2.80) | .63 | 1.00 | −0.45 (−2.66, 1.75) | .69 | 1.00 | 0.25 (−2.93, 3.44) | .88 | 1.00 |

| PANSS Positive Score | 0.64 (−0.11, 1.39) | .10 | .87 | −0.04 (−0.77, 0.70) | .92 | 1.00 | −0.14 (−1.20, 0.92) | .79 | 1.00 |

| PANSS Negative Score | −0.21 (−1.22, 0.80) | .69 | 1.00 | −0.64 (−1.63, 0.35) | .21 | 1.00 | 1.33 (−0.10, 2.76) | .07 | .66 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology Score | 0.08 (−1.22, 1.37) | .91 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−1.33, 1.21) | .93 | 1.00 | −0.64 (−2.47, 1.19) | .50 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal Factor | −0.04 (−0.21, 0.12) | .61 | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.29, 0.04) | .14 | 1.00 | 0.23 (−0.00, 0.47) | .06 | .52 |

| Delusion Factor | 0.09 (−0.02, 0.21) | .11 | .99 | 0.02 (−0.09, 0.13) | .69 | 1.00 | −0.04 (−0.20, 0.12) | .60 | 1.00 |

| Anxiety Factor | −0.02 (−0.21, 0.17) | .82 | 1.00 | 0.00 (−0.19, 0.19) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.09 (−0.36, 0.18) | .53 | 1.00 |

| Disorganization Factor | −0.00 (−0.13, 0.12) | .95 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.09, 0.16) | .61 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.23, 0.13) | .55 | 1.00 |

| Poor Control Factor | 0.01 (−0.10, 0.12) | .84 | 1.00 | −0.03 (−0.14, 0.08) | .64 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.16, 0.16) | .99 | 1.00 |

| . | 1. Two-way Complete Model . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors (Interaction With Time) . | Effect of Oxytocin . | Effect of Social Treatment . | Interaction Effect of Oxytocin and Social Treatment . | ||||||

| Outcomes . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . |

| CIB Total Score | |||||||||

| Individual items | |||||||||

| Acknowledgment | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.35) | .31 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.19, 0.24) | .82 | 1.00 | −0.08 (−0.40, 0.25) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Alertness | 0.15 (−0.07, 0.37) | .20 | 1.00 | 0.17 (−0.04, 0.38) | .13 | 1.00 | −0.33 (−0.64, −0.01) | .06 | 1.00 |

| Anger | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.08) | .80 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.05, 0.09) | .56 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.16 , 0.05) | .36 | 1.00 |

| Anxiety | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.16) | .42 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.17) | .27 | 1.00 | −0.17 (−0.33, −0.01) | .05 | 1.00 |

| Avoidance | 0.07 (0.00, 0.14) | .05 | 1.00 | 0.07 (0.00, 0.13) | .05 | 1.00 | −0.14 (−0.24, −0.05) | .01 | .18 |

| Blunt Affect | −0.04 (−0.16, 0.08) | .55 | 1.00 | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.01) | .04 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.13, 0.22) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Constriction | −0.13 (−0.30, 0.04) | .16 | 1.00 | −0.08 (−0.24, 0.08) | .35 | 1.00 | 0.12 (−0.12, 0.36) | .36 | 1.00 |

| Criticism | −0.08 (−0.18, 0.02) | .16 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.16, 0.03) | .21 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.06, 0.23) | .28 | 1.00 |

| Detachment | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.06) | .26 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | .43 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | .72 | 1.00 |

| Elaboration | 0.09 (−0.11, 0.30) | .40 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.20, 0.19) | .96 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.34, 0.24) | .75 | 1.00 |

| Fluency | 0.15 (−0.01, 0.31) | .08 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.06, 0.24) | .24 | 1.00 | −0.15 (−0.37, 0.08) | .23 | 1.00 |

| Gaze | −0.05 (−0.27, 0.16) | .63 | 1.00 | 0.19 (−0.01, 0.39) | .08 | 1.00 | 0.07 (−0.24, 0.37) | .67 | 1.00 |

| Hostility | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.06) | .18 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.03, 0.03) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.01) | .11 | 1.00 |

| Initiation | 0.24 (−0.06, 0.54) | .14 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.19, 0.38) | .54 | 1.00 | −0.27 (−0.70, 0.16) | .23 | 1.00 |

| Instrusiveness | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.04) | .31 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.08) | .88 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.07, 0.15) | .52 | 1.00 |

| Therapist leads | −0.01 (−0.17, 0.16) | .93 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.16, 0.15) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.07 (−0.30, 0.16) | .58 | 1.00 |

| Patient leads | 0.05 (−0.09, 0.20) | .47 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.12, 0.16) | .78 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.21, 0.20) | .96 | 1.00 |

| Mismatch Affect | 0.03 (−0.05, 0.11) | .44 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.11) | .42 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.06) | .34 | 1.00 |

| Motivation | 0.05 (−0.13, 0.24) | .58 | 1.00 | 0.15 (−0.02, 0.32) | .11 | 1.00 | −0.25 (−0.51, 0.01) | .08 | 1.00 |

| Negative Affect | −0.19 (−0.39, 0.00) | .06 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.16, 0.21) | .80 | 1.00 | 0.13 (−0.15, 0.40) | .39 | 1.00 |

| Positive Affect | 0.13 (0.00, 0.26) | .06 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.06, 0.19) | .33 | 1.00 | −0.18 (−0.37, 0.01) | .07 | 1.00 |

| Persistence | −0.05 (−0.20, 0.09) | .49 | 1.00 | −0.10 (−0.24, 0.04) | .19 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.18, 0.25) | .75 | 1.00 |

| Reciprocity | 0.05 (−0.10, 0.20) | .51 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.10, 0.18) | .62 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.26, 0.16) | .63 | 1.00 |

| Silence | 0.00 (−0.10, 0.10) | .93 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.11) | .73 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.11, 0.18) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Synchrony | 0.10 (−0.06, 0.27) | .25 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.09, 0.22) | .44 | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.36, 0.11) | .32 | 1.00 |

| Tension | −0.11 (−0.24, 0.01) | .10 | 1.00 | −0.10 (−0.22, 0.02) | .13 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.11, 0.26) | .43 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal | 0.00 (−0.14, 0.14) | .99 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.14 , 0.12) | .89 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.19, 0.21) | .95 | 1.00 |

| Factors | |||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.11 (−0.15, 0.37) | .41 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.15, 0.33) | .49 | 1.00 | −0.15 (−0.52, 0.21) | .43 | 1.00 |

| Initiation | 0.14 (−0.09, 0.37) | .25 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.17, 0.26) | .70 | 1.00 | −0.02 (−0.35, 0.31) | .90 | 1.00 |

| Tension | −0.21 (−0.47, 0.04) | .12 | .60 | −0.15 (−0.40, 0.09) | .23 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.27, 0.46) | .63 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal | 0.01 (−0.26, 0.28) | .95 | 1.00 | −0.13 (−0.38, 0.13) | .35 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.30, 0.47) | .69 | 1.00 |

| Positive Affect | 0.28 (0.08, 0.49) | .01 | .06 | 0.19 (−0.00, 0.39) | .07 | .33 | −0.36 (−0.66, −0.07) | .02 | .11 |

| . | 1. Two-way Complete Model . | ||||||||

| Predictors (Interaction With Time) . | Oxytocin . | Social Treatment . | Social Treatment × Oxytocin . | ||||||

| Outcomes . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . |

| PANSS Total | 0.55 (−1.71, 2.80) | .63 | 1.00 | −0.45 (−2.66, 1.75) | .69 | 1.00 | 0.25 (−2.93, 3.44) | .88 | 1.00 |

| PANSS Positive Score | 0.64 (−0.11, 1.39) | .10 | .87 | −0.04 (−0.77, 0.70) | .92 | 1.00 | −0.14 (−1.20, 0.92) | .79 | 1.00 |

| PANSS Negative Score | −0.21 (−1.22, 0.80) | .69 | 1.00 | −0.64 (−1.63, 0.35) | .21 | 1.00 | 1.33 (−0.10, 2.76) | .07 | .66 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology Score | 0.08 (−1.22, 1.37) | .91 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−1.33, 1.21) | .93 | 1.00 | −0.64 (−2.47, 1.19) | .50 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal Factor | −0.04 (−0.21, 0.12) | .61 | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.29, 0.04) | .14 | 1.00 | 0.23 (−0.00, 0.47) | .06 | .52 |

| Delusion Factor | 0.09 (−0.02, 0.21) | .11 | .99 | 0.02 (−0.09, 0.13) | .69 | 1.00 | −0.04 (−0.20, 0.12) | .60 | 1.00 |

| Anxiety Factor | −0.02 (−0.21, 0.17) | .82 | 1.00 | 0.00 (−0.19, 0.19) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.09 (−0.36, 0.18) | .53 | 1.00 |

| Disorganization Factor | −0.00 (−0.13, 0.12) | .95 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.09, 0.16) | .61 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.23, 0.13) | .55 | 1.00 |

| Poor Control Factor | 0.01 (−0.10, 0.12) | .84 | 1.00 | −0.03 (−0.14, 0.08) | .64 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.16, 0.16) | .99 | 1.00 |

(1. Two-way complete model: Outcome ~ Oxytocin * Social Treatment * Time).

Two-way Complete Model for Oxytocin, Social Skills Training or Both for CIB and PANSS Outcomes

| . | 1. Two-way Complete Model . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors (Interaction With Time) . | Effect of Oxytocin . | Effect of Social Treatment . | Interaction Effect of Oxytocin and Social Treatment . | ||||||

| Outcomes . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . |

| CIB Total Score | |||||||||

| Individual items | |||||||||

| Acknowledgment | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.35) | .31 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.19, 0.24) | .82 | 1.00 | −0.08 (−0.40, 0.25) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Alertness | 0.15 (−0.07, 0.37) | .20 | 1.00 | 0.17 (−0.04, 0.38) | .13 | 1.00 | −0.33 (−0.64, −0.01) | .06 | 1.00 |

| Anger | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.08) | .80 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.05, 0.09) | .56 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.16 , 0.05) | .36 | 1.00 |

| Anxiety | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.16) | .42 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.17) | .27 | 1.00 | −0.17 (−0.33, −0.01) | .05 | 1.00 |

| Avoidance | 0.07 (0.00, 0.14) | .05 | 1.00 | 0.07 (0.00, 0.13) | .05 | 1.00 | −0.14 (−0.24, −0.05) | .01 | .18 |

| Blunt Affect | −0.04 (−0.16, 0.08) | .55 | 1.00 | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.01) | .04 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.13, 0.22) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Constriction | −0.13 (−0.30, 0.04) | .16 | 1.00 | −0.08 (−0.24, 0.08) | .35 | 1.00 | 0.12 (−0.12, 0.36) | .36 | 1.00 |

| Criticism | −0.08 (−0.18, 0.02) | .16 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.16, 0.03) | .21 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.06, 0.23) | .28 | 1.00 |

| Detachment | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.06) | .26 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | .43 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | .72 | 1.00 |

| Elaboration | 0.09 (−0.11, 0.30) | .40 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.20, 0.19) | .96 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.34, 0.24) | .75 | 1.00 |

| Fluency | 0.15 (−0.01, 0.31) | .08 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.06, 0.24) | .24 | 1.00 | −0.15 (−0.37, 0.08) | .23 | 1.00 |

| Gaze | −0.05 (−0.27, 0.16) | .63 | 1.00 | 0.19 (−0.01, 0.39) | .08 | 1.00 | 0.07 (−0.24, 0.37) | .67 | 1.00 |

| Hostility | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.06) | .18 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.03, 0.03) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.01) | .11 | 1.00 |

| Initiation | 0.24 (−0.06, 0.54) | .14 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.19, 0.38) | .54 | 1.00 | −0.27 (−0.70, 0.16) | .23 | 1.00 |

| Instrusiveness | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.04) | .31 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.08) | .88 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.07, 0.15) | .52 | 1.00 |

| Therapist leads | −0.01 (−0.17, 0.16) | .93 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.16, 0.15) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.07 (−0.30, 0.16) | .58 | 1.00 |

| Patient leads | 0.05 (−0.09, 0.20) | .47 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.12, 0.16) | .78 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.21, 0.20) | .96 | 1.00 |

| Mismatch Affect | 0.03 (−0.05, 0.11) | .44 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.11) | .42 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.06) | .34 | 1.00 |

| Motivation | 0.05 (−0.13, 0.24) | .58 | 1.00 | 0.15 (−0.02, 0.32) | .11 | 1.00 | −0.25 (−0.51, 0.01) | .08 | 1.00 |

| Negative Affect | −0.19 (−0.39, 0.00) | .06 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.16, 0.21) | .80 | 1.00 | 0.13 (−0.15, 0.40) | .39 | 1.00 |

| Positive Affect | 0.13 (0.00, 0.26) | .06 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.06, 0.19) | .33 | 1.00 | −0.18 (−0.37, 0.01) | .07 | 1.00 |

| Persistence | −0.05 (−0.20, 0.09) | .49 | 1.00 | −0.10 (−0.24, 0.04) | .19 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.18, 0.25) | .75 | 1.00 |

| Reciprocity | 0.05 (−0.10, 0.20) | .51 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.10, 0.18) | .62 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.26, 0.16) | .63 | 1.00 |

| Silence | 0.00 (−0.10, 0.10) | .93 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.11) | .73 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.11, 0.18) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Synchrony | 0.10 (−0.06, 0.27) | .25 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.09, 0.22) | .44 | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.36, 0.11) | .32 | 1.00 |

| Tension | −0.11 (−0.24, 0.01) | .10 | 1.00 | −0.10 (−0.22, 0.02) | .13 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.11, 0.26) | .43 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal | 0.00 (−0.14, 0.14) | .99 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.14 , 0.12) | .89 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.19, 0.21) | .95 | 1.00 |

| Factors | |||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.11 (−0.15, 0.37) | .41 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.15, 0.33) | .49 | 1.00 | −0.15 (−0.52, 0.21) | .43 | 1.00 |

| Initiation | 0.14 (−0.09, 0.37) | .25 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.17, 0.26) | .70 | 1.00 | −0.02 (−0.35, 0.31) | .90 | 1.00 |

| Tension | −0.21 (−0.47, 0.04) | .12 | .60 | −0.15 (−0.40, 0.09) | .23 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.27, 0.46) | .63 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal | 0.01 (−0.26, 0.28) | .95 | 1.00 | −0.13 (−0.38, 0.13) | .35 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.30, 0.47) | .69 | 1.00 |

| Positive Affect | 0.28 (0.08, 0.49) | .01 | .06 | 0.19 (−0.00, 0.39) | .07 | .33 | −0.36 (−0.66, −0.07) | .02 | .11 |

| . | 1. Two-way Complete Model . | ||||||||

| Predictors (Interaction With Time) . | Oxytocin . | Social Treatment . | Social Treatment × Oxytocin . | ||||||

| Outcomes . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . |

| PANSS Total | 0.55 (−1.71, 2.80) | .63 | 1.00 | −0.45 (−2.66, 1.75) | .69 | 1.00 | 0.25 (−2.93, 3.44) | .88 | 1.00 |

| PANSS Positive Score | 0.64 (−0.11, 1.39) | .10 | .87 | −0.04 (−0.77, 0.70) | .92 | 1.00 | −0.14 (−1.20, 0.92) | .79 | 1.00 |

| PANSS Negative Score | −0.21 (−1.22, 0.80) | .69 | 1.00 | −0.64 (−1.63, 0.35) | .21 | 1.00 | 1.33 (−0.10, 2.76) | .07 | .66 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology Score | 0.08 (−1.22, 1.37) | .91 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−1.33, 1.21) | .93 | 1.00 | −0.64 (−2.47, 1.19) | .50 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal Factor | −0.04 (−0.21, 0.12) | .61 | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.29, 0.04) | .14 | 1.00 | 0.23 (−0.00, 0.47) | .06 | .52 |

| Delusion Factor | 0.09 (−0.02, 0.21) | .11 | .99 | 0.02 (−0.09, 0.13) | .69 | 1.00 | −0.04 (−0.20, 0.12) | .60 | 1.00 |

| Anxiety Factor | −0.02 (−0.21, 0.17) | .82 | 1.00 | 0.00 (−0.19, 0.19) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.09 (−0.36, 0.18) | .53 | 1.00 |

| Disorganization Factor | −0.00 (−0.13, 0.12) | .95 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.09, 0.16) | .61 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.23, 0.13) | .55 | 1.00 |

| Poor Control Factor | 0.01 (−0.10, 0.12) | .84 | 1.00 | −0.03 (−0.14, 0.08) | .64 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.16, 0.16) | .99 | 1.00 |

| . | 1. Two-way Complete Model . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors (Interaction With Time) . | Effect of Oxytocin . | Effect of Social Treatment . | Interaction Effect of Oxytocin and Social Treatment . | ||||||

| Outcomes . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . |

| CIB Total Score | |||||||||

| Individual items | |||||||||

| Acknowledgment | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.35) | .31 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.19, 0.24) | .82 | 1.00 | −0.08 (−0.40, 0.25) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Alertness | 0.15 (−0.07, 0.37) | .20 | 1.00 | 0.17 (−0.04, 0.38) | .13 | 1.00 | −0.33 (−0.64, −0.01) | .06 | 1.00 |

| Anger | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.08) | .80 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.05, 0.09) | .56 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.16 , 0.05) | .36 | 1.00 |

| Anxiety | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.16) | .42 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.17) | .27 | 1.00 | −0.17 (−0.33, −0.01) | .05 | 1.00 |

| Avoidance | 0.07 (0.00, 0.14) | .05 | 1.00 | 0.07 (0.00, 0.13) | .05 | 1.00 | −0.14 (−0.24, −0.05) | .01 | .18 |

| Blunt Affect | −0.04 (−0.16, 0.08) | .55 | 1.00 | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.01) | .04 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.13, 0.22) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Constriction | −0.13 (−0.30, 0.04) | .16 | 1.00 | −0.08 (−0.24, 0.08) | .35 | 1.00 | 0.12 (−0.12, 0.36) | .36 | 1.00 |

| Criticism | −0.08 (−0.18, 0.02) | .16 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.16, 0.03) | .21 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.06, 0.23) | .28 | 1.00 |

| Detachment | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.06) | .26 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | .43 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | .72 | 1.00 |

| Elaboration | 0.09 (−0.11, 0.30) | .40 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.20, 0.19) | .96 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.34, 0.24) | .75 | 1.00 |

| Fluency | 0.15 (−0.01, 0.31) | .08 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.06, 0.24) | .24 | 1.00 | −0.15 (−0.37, 0.08) | .23 | 1.00 |

| Gaze | −0.05 (−0.27, 0.16) | .63 | 1.00 | 0.19 (−0.01, 0.39) | .08 | 1.00 | 0.07 (−0.24, 0.37) | .67 | 1.00 |

| Hostility | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.06) | .18 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.03, 0.03) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.01) | .11 | 1.00 |

| Initiation | 0.24 (−0.06, 0.54) | .14 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.19, 0.38) | .54 | 1.00 | −0.27 (−0.70, 0.16) | .23 | 1.00 |

| Instrusiveness | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.04) | .31 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.08) | .88 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.07, 0.15) | .52 | 1.00 |

| Therapist leads | −0.01 (−0.17, 0.16) | .93 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.16, 0.15) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.07 (−0.30, 0.16) | .58 | 1.00 |

| Patient leads | 0.05 (−0.09, 0.20) | .47 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.12, 0.16) | .78 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.21, 0.20) | .96 | 1.00 |

| Mismatch Affect | 0.03 (−0.05, 0.11) | .44 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.11) | .42 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.06) | .34 | 1.00 |

| Motivation | 0.05 (−0.13, 0.24) | .58 | 1.00 | 0.15 (−0.02, 0.32) | .11 | 1.00 | −0.25 (−0.51, 0.01) | .08 | 1.00 |

| Negative Affect | −0.19 (−0.39, 0.00) | .06 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.16, 0.21) | .80 | 1.00 | 0.13 (−0.15, 0.40) | .39 | 1.00 |

| Positive Affect | 0.13 (0.00, 0.26) | .06 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.06, 0.19) | .33 | 1.00 | −0.18 (−0.37, 0.01) | .07 | 1.00 |

| Persistence | −0.05 (−0.20, 0.09) | .49 | 1.00 | −0.10 (−0.24, 0.04) | .19 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.18, 0.25) | .75 | 1.00 |

| Reciprocity | 0.05 (−0.10, 0.20) | .51 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.10, 0.18) | .62 | 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.26, 0.16) | .63 | 1.00 |

| Silence | 0.00 (−0.10, 0.10) | .93 | 1.00 | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.11) | .73 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.11, 0.18) | .65 | 1.00 |

| Synchrony | 0.10 (−0.06, 0.27) | .25 | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.09, 0.22) | .44 | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.36, 0.11) | .32 | 1.00 |

| Tension | −0.11 (−0.24, 0.01) | .10 | 1.00 | −0.10 (−0.22, 0.02) | .13 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.11, 0.26) | .43 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal | 0.00 (−0.14, 0.14) | .99 | 1.00 | −0.01 (−0.14 , 0.12) | .89 | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.19, 0.21) | .95 | 1.00 |

| Factors | |||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.11 (−0.15, 0.37) | .41 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.15, 0.33) | .49 | 1.00 | −0.15 (−0.52, 0.21) | .43 | 1.00 |

| Initiation | 0.14 (−0.09, 0.37) | .25 | 1.00 | 0.04 (−0.17, 0.26) | .70 | 1.00 | −0.02 (−0.35, 0.31) | .90 | 1.00 |

| Tension | −0.21 (−0.47, 0.04) | .12 | .60 | −0.15 (−0.40, 0.09) | .23 | 1.00 | 0.09 (−0.27, 0.46) | .63 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal | 0.01 (−0.26, 0.28) | .95 | 1.00 | −0.13 (−0.38, 0.13) | .35 | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.30, 0.47) | .69 | 1.00 |

| Positive Affect | 0.28 (0.08, 0.49) | .01 | .06 | 0.19 (−0.00, 0.39) | .07 | .33 | −0.36 (−0.66, −0.07) | .02 | .11 |

| . | 1. Two-way Complete Model . | ||||||||

| Predictors (Interaction With Time) . | Oxytocin . | Social Treatment . | Social Treatment × Oxytocin . | ||||||

| Outcomes . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . | Estimates (CIs) . | P-value . | Q-value . |

| PANSS Total | 0.55 (−1.71, 2.80) | .63 | 1.00 | −0.45 (−2.66, 1.75) | .69 | 1.00 | 0.25 (−2.93, 3.44) | .88 | 1.00 |

| PANSS Positive Score | 0.64 (−0.11, 1.39) | .10 | .87 | −0.04 (−0.77, 0.70) | .92 | 1.00 | −0.14 (−1.20, 0.92) | .79 | 1.00 |

| PANSS Negative Score | −0.21 (−1.22, 0.80) | .69 | 1.00 | −0.64 (−1.63, 0.35) | .21 | 1.00 | 1.33 (−0.10, 2.76) | .07 | .66 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology Score | 0.08 (−1.22, 1.37) | .91 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−1.33, 1.21) | .93 | 1.00 | −0.64 (−2.47, 1.19) | .50 | 1.00 |

| Withdrawal Factor | −0.04 (−0.21, 0.12) | .61 | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.29, 0.04) | .14 | 1.00 | 0.23 (−0.00, 0.47) | .06 | .52 |

| Delusion Factor | 0.09 (−0.02, 0.21) | .11 | .99 | 0.02 (−0.09, 0.13) | .69 | 1.00 | −0.04 (−0.20, 0.12) | .60 | 1.00 |

| Anxiety Factor | −0.02 (−0.21, 0.17) | .82 | 1.00 | 0.00 (−0.19, 0.19) | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.09 (−0.36, 0.18) | .53 | 1.00 |

| Disorganization Factor | −0.00 (−0.13, 0.12) | .95 | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.09, 0.16) | .61 | 1.00 | −0.06 (−0.23, 0.13) | .55 | 1.00 |

| Poor Control Factor | 0.01 (−0.10, 0.12) | .84 | 1.00 | −0.03 (−0.14, 0.08) | .64 | 1.00 | −0.00 (−0.16, 0.16) | .99 | 1.00 |

(1. Two-way complete model: Outcome ~ Oxytocin * Social Treatment * Time).

Interaction model with CIB total (a), PANSS total (b), and PANSS subscales (c) as outcomes.

The Effect of Oxytocin and Social Skills Training on Individual CIB Variables and Factors

For each of the 27 CIB social interaction items and the CIB Factors, comparisons were made between oxytocin and placebo, between the social skills training and supportive psychotherapy, and their interactions. This is presented in table 2. The effect of oxytocin is presented in the left panel, the effect of social skills training in the next panel, and the interaction of the 2 treatments in the third panel. The outcome in the far-right panels reflects the direct outcome of oxytocin vs placebo, and social skills training vs supportive psychotherapy, evaluated without the interaction. These results are presented in graphs with more statistical information in the web supplement. When comparing oxytocin to placebo, summing the results over all 3 scenarios, oxytocin had no significant effects on the 2 major factors Synergy or Initiative, as well as the Tension and Withdrawal factors. Oxytocin improved the positive affect factor (coefficient 0.28, CI: 0.08–0.49, P = .01), but did so only in the supportive psychotherapy conditions, (the opposite of the predicted effects), (interaction coefficient −0.36, CI: −0.66 to −0.07, P = .02), (see web supplement 1.1.3, page 9.) Social skills training reduced blunted affect, regardless of oxytocin treatment (coefficient −0.13, CI: −0.24 to 0.01, P = .04).

Overall, oxytocin led to a decrease in the avoidance item, when combined with social skills training, and there was an increase in the avoidance item in the supportive psychotherapy interactions, coefficient −0.14, CI: −0.24 to −0.05, P = .01, see figure 2 and web supplement 1.2.5 page 17. Social skills training, regardless of oxytocin, led toward an improvement in gaze (estimate 0.22, P = .01).

When controlling for multiple comparisons, none of these findings remained significant.

The Effect of Oxytocin and Social Skills Training in the 3 Social Interaction Conditions

Post-hoc analyses looking at the different CIB factors in the 3 (positive, conflicted, and supportive) social interactions separately (table 3) showed a few significant effects. In the positive social interaction, the positive affect factor improved in the oxytocin groups (coefficient 0.29, CI: 0.04−0.55, P = .03). In the conflict social interaction, the withdrawal factor (coefficient −0.33, CI: −0.57 to 0.08, P = .01) and the positive affect (coefficient 0.21, CI: 0.02–0.04, P = .04) showed improvement in the social skills training group compared to supportive psychotherapy. However, for those patients receiving social skills training together with oxytocin, withdrawal increased and positive affect decreased.

Full Interaction Model for the Effect of Oxytocin, Social Skills Training or Both on the 5 Factors in the 3 Different Social Interaction Scenarios

| . | Full Interaction Model . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Effect of Oxytocin . | Effect of Social Treatment . | Interaction Effect of Oxy and Social . | |||||||||

| . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . |

| Conflict Interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | −0.02 | −0.29 | 0.26 | .92 | 0.05 | −0.21 | 0.31 | .71 | 0.12 | −0.27 | 0.51 | .56 |

| Initiation | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.45 | .18 | 0.01 | −0.23 | 0.26 | .92 | −0.09 | −0.47 | 0.28 | .63 |

| Tension | −0.15 | −0.47 | 0.16 | .36 | −0.16 | −0.46 | 0.13 | .3 | 0.12 | −0.33 | 0.56 | .62 |

| Withdrawal | −0.16 | −0.41 | 0.1 | .25 | −0.33 | −0.57 | −0.08 | .01 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.76 | .05 |

| Positive Affect | 0.14 | −0.07 | 0.34 | .21 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.4 | .04 | −0.45 | −0.74 | −0.16 | .01 |

| Positive interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.09 | −0.23 | 0.41 | .59 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.2 | .54 | −0.15 | −0.6 | 0.3 | .53 |

| Initiation | 0.01 | −0.27 | 0.29 | .96 | 0.16 | −0.1 | 0.43 | .25 | 0.07 | −0.33 | 0.46 | .75 |

| Tension | −0.14 | −0.42 | 0.15 | .37 | −0.14 | −0.4 | 0.13 | .34 | 0.04 | −0.36 | 0.44 | .85 |

| Withdrawal | 0.14 | −0.22 | 0.5 | .46 | −0.06 | −0.4 | 0.28 | .74 | −0.15 | −0.66 | 0.36 | .58 |

| Positive Affect | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.55 | .03 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.31 | .56 | −0.32 | −0.68 | 0.04 | .1 |

| Supportive interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.77 | .01 | 0.19 | −0.11 | 0.49 | .24 | −0.29 | −0.74 | 0.16 | .22 |

| Initiation | 0.25 | −0.03 | 0.53 | .1 | 0.08 | −0.19 | 0.34 | .58 | −0.15 | −0.55 | 0.24 | .46 |

| Tension | −0.39 | −0.76 | −0.03 | .05 | −0.25 | −0.6 | 0.09 | .16 | 0.54 | 0.02 | 1.05 | .05 |

| Criticism | −0.28 | −0.61 | 0.05 | .11 | −0.18 | −0.5 | 0.13 | .28 | 0.15 | −0.33 | 0.62 | .56 |

| Positive Affect | 0.13 | −0.19 | 0.45 | .45 | −0.13 | −0.43 | 0.18 | .43 | −0.07 | −0.53 | 0.39 | .77 |

| . | Full Interaction Model . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Effect of Oxytocin . | Effect of Social Treatment . | Interaction Effect of Oxy and Social . | |||||||||

| . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . |

| Conflict Interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | −0.02 | −0.29 | 0.26 | .92 | 0.05 | −0.21 | 0.31 | .71 | 0.12 | −0.27 | 0.51 | .56 |

| Initiation | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.45 | .18 | 0.01 | −0.23 | 0.26 | .92 | −0.09 | −0.47 | 0.28 | .63 |

| Tension | −0.15 | −0.47 | 0.16 | .36 | −0.16 | −0.46 | 0.13 | .3 | 0.12 | −0.33 | 0.56 | .62 |

| Withdrawal | −0.16 | −0.41 | 0.1 | .25 | −0.33 | −0.57 | −0.08 | .01 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.76 | .05 |

| Positive Affect | 0.14 | −0.07 | 0.34 | .21 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.4 | .04 | −0.45 | −0.74 | −0.16 | .01 |

| Positive interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.09 | −0.23 | 0.41 | .59 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.2 | .54 | −0.15 | −0.6 | 0.3 | .53 |

| Initiation | 0.01 | −0.27 | 0.29 | .96 | 0.16 | −0.1 | 0.43 | .25 | 0.07 | −0.33 | 0.46 | .75 |

| Tension | −0.14 | −0.42 | 0.15 | .37 | −0.14 | −0.4 | 0.13 | .34 | 0.04 | −0.36 | 0.44 | .85 |

| Withdrawal | 0.14 | −0.22 | 0.5 | .46 | −0.06 | −0.4 | 0.28 | .74 | −0.15 | −0.66 | 0.36 | .58 |

| Positive Affect | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.55 | .03 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.31 | .56 | −0.32 | −0.68 | 0.04 | .1 |

| Supportive interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.77 | .01 | 0.19 | −0.11 | 0.49 | .24 | −0.29 | −0.74 | 0.16 | .22 |

| Initiation | 0.25 | −0.03 | 0.53 | .1 | 0.08 | −0.19 | 0.34 | .58 | −0.15 | −0.55 | 0.24 | .46 |

| Tension | −0.39 | −0.76 | −0.03 | .05 | −0.25 | −0.6 | 0.09 | .16 | 0.54 | 0.02 | 1.05 | .05 |

| Criticism | −0.28 | −0.61 | 0.05 | .11 | −0.18 | −0.5 | 0.13 | .28 | 0.15 | −0.33 | 0.62 | .56 |

| Positive Affect | 0.13 | −0.19 | 0.45 | .45 | −0.13 | −0.43 | 0.18 | .43 | −0.07 | −0.53 | 0.39 | .77 |

Full Interaction Model for the Effect of Oxytocin, Social Skills Training or Both on the 5 Factors in the 3 Different Social Interaction Scenarios

| . | Full Interaction Model . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Effect of Oxytocin . | Effect of Social Treatment . | Interaction Effect of Oxy and Social . | |||||||||

| . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . |

| Conflict Interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | −0.02 | −0.29 | 0.26 | .92 | 0.05 | −0.21 | 0.31 | .71 | 0.12 | −0.27 | 0.51 | .56 |

| Initiation | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.45 | .18 | 0.01 | −0.23 | 0.26 | .92 | −0.09 | −0.47 | 0.28 | .63 |

| Tension | −0.15 | −0.47 | 0.16 | .36 | −0.16 | −0.46 | 0.13 | .3 | 0.12 | −0.33 | 0.56 | .62 |

| Withdrawal | −0.16 | −0.41 | 0.1 | .25 | −0.33 | −0.57 | −0.08 | .01 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.76 | .05 |

| Positive Affect | 0.14 | −0.07 | 0.34 | .21 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.4 | .04 | −0.45 | −0.74 | −0.16 | .01 |

| Positive interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.09 | −0.23 | 0.41 | .59 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.2 | .54 | −0.15 | −0.6 | 0.3 | .53 |

| Initiation | 0.01 | −0.27 | 0.29 | .96 | 0.16 | −0.1 | 0.43 | .25 | 0.07 | −0.33 | 0.46 | .75 |

| Tension | −0.14 | −0.42 | 0.15 | .37 | −0.14 | −0.4 | 0.13 | .34 | 0.04 | −0.36 | 0.44 | .85 |

| Withdrawal | 0.14 | −0.22 | 0.5 | .46 | −0.06 | −0.4 | 0.28 | .74 | −0.15 | −0.66 | 0.36 | .58 |

| Positive Affect | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.55 | .03 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.31 | .56 | −0.32 | −0.68 | 0.04 | .1 |

| Supportive interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.77 | .01 | 0.19 | −0.11 | 0.49 | .24 | −0.29 | −0.74 | 0.16 | .22 |

| Initiation | 0.25 | −0.03 | 0.53 | .1 | 0.08 | −0.19 | 0.34 | .58 | −0.15 | −0.55 | 0.24 | .46 |

| Tension | −0.39 | −0.76 | −0.03 | .05 | −0.25 | −0.6 | 0.09 | .16 | 0.54 | 0.02 | 1.05 | .05 |

| Criticism | −0.28 | −0.61 | 0.05 | .11 | −0.18 | −0.5 | 0.13 | .28 | 0.15 | −0.33 | 0.62 | .56 |

| Positive Affect | 0.13 | −0.19 | 0.45 | .45 | −0.13 | −0.43 | 0.18 | .43 | −0.07 | −0.53 | 0.39 | .77 |

| . | Full Interaction Model . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Effect of Oxytocin . | Effect of Social Treatment . | Interaction Effect of Oxy and Social . | |||||||||

| . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . | coef . | lower ci . | upper ci . | P-value . |

| Conflict Interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | −0.02 | −0.29 | 0.26 | .92 | 0.05 | −0.21 | 0.31 | .71 | 0.12 | −0.27 | 0.51 | .56 |

| Initiation | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.45 | .18 | 0.01 | −0.23 | 0.26 | .92 | −0.09 | −0.47 | 0.28 | .63 |

| Tension | −0.15 | −0.47 | 0.16 | .36 | −0.16 | −0.46 | 0.13 | .3 | 0.12 | −0.33 | 0.56 | .62 |

| Withdrawal | −0.16 | −0.41 | 0.1 | .25 | −0.33 | −0.57 | −0.08 | .01 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.76 | .05 |

| Positive Affect | 0.14 | −0.07 | 0.34 | .21 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.4 | .04 | −0.45 | −0.74 | −0.16 | .01 |

| Positive interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.09 | −0.23 | 0.41 | .59 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.2 | .54 | −0.15 | −0.6 | 0.3 | .53 |

| Initiation | 0.01 | −0.27 | 0.29 | .96 | 0.16 | −0.1 | 0.43 | .25 | 0.07 | −0.33 | 0.46 | .75 |

| Tension | −0.14 | −0.42 | 0.15 | .37 | −0.14 | −0.4 | 0.13 | .34 | 0.04 | −0.36 | 0.44 | .85 |

| Withdrawal | 0.14 | −0.22 | 0.5 | .46 | −0.06 | −0.4 | 0.28 | .74 | −0.15 | −0.66 | 0.36 | .58 |

| Positive Affect | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.55 | .03 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.31 | .56 | −0.32 | −0.68 | 0.04 | .1 |

| Supportive interaction | ||||||||||||

| Synchrony | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.77 | .01 | 0.19 | −0.11 | 0.49 | .24 | −0.29 | −0.74 | 0.16 | .22 |

| Initiation | 0.25 | −0.03 | 0.53 | .1 | 0.08 | −0.19 | 0.34 | .58 | −0.15 | −0.55 | 0.24 | .46 |

| Tension | −0.39 | −0.76 | −0.03 | .05 | −0.25 | −0.6 | 0.09 | .16 | 0.54 | 0.02 | 1.05 | .05 |

| Criticism | −0.28 | −0.61 | 0.05 | .11 | −0.18 | −0.5 | 0.13 | .28 | 0.15 | −0.33 | 0.62 | .56 |

| Positive Affect | 0.13 | −0.19 | 0.45 | .45 | −0.13 | −0.43 | 0.18 | .43 | −0.07 | −0.53 | 0.39 | .77 |

In the supportive interaction, oxytocin improved the synchrony factor (coefficient 0.45, CI: 0.13–0.77, P = .01), and decreased the tension factor (coefficient −0.39, CI: −0.76 to −0.03, P = .05). However, the opposite effect is seen for patients receiving oxytocin together with the social skills training (coefficient 0.54, CI: 0.02–1.05, P = .05).

All P values were not significant when controlling for multiple comparisons.

The Effect of Oxytocin and Social Skills Training on PANSS Scores

We evaluated the interaction effects of oxytocin and social skills training on the PANSS total score, its subscales, and the 5 PANSS factors, to test the hypothesis that oxytocin and social skills training potentiated each other. No statistically significant effects were reported for both the main interventions (oxytocin or social skills training) and the interaction of the 2 on any PANSS variable. The only significant main effect of oxytocin was the worsening of positive symptoms (coefficient estimate 0.56, 95% CI: 0.03–1.09, P = .04), when directly evaluated since the interactions was not significant. However, when correcting for multiple comparisons, this finding did not remain significant (table 2 and figure 2).

Discussion

This was an exploratory study, using the CIB coding instrument to test the effect of oxytocin, social skills training, and the combination of the 2 on patients with schizophrenia. This instrument has not been previously used in schizophrenia, therefore we looked at the total score, its factors, and individual items to explore the possible effect of oxytocin. Overall, oxytocin failed to improve social interactions and overall psychopathology, as seen in the (PANSS) analyses when we controlled for multiple comparisons.

Social Interactions

Before controlling for multiple comparisons, oxytocin did improve avoidant behavior. This is consistent with the literature and specifically with the theory of Kemp and Guastella,59 who suggest that oxytocin decreases avoidance and withdrawal. This finding is also supported by studies on rodents,60 borderline personality disorder,61 and social anxiety.62

Very interesting and relevant for our study is the work of Heinrichs et al63 which showed that the combination of intranasal administration of oxytocin and social support reduces both anxiety and neuroendocrine stress reactivity in healthy men. Although the social support given in the Heinrichs study is not identical to the social skills training given in our study, it suggests that in these situations when support is needed, oxytocin may be relevant.

Our study is consistent with several studies that failed to find oxytocin more effective than placebo on social functioning.31,35,64–68

Symptoms

We found no effect of high-dose oxytocin on clinical symptoms measured by the PANSS. Meta-analyses found oxytocin to be no better than placebo on PANSS total score,17,22,69 a finding consistent with other reviews.70 But several of the studies that did find oxytocin effective on the PANSS used high doses,24,26,27 which is why we used this high dose, but with no improvement. Furthermore, we found a hint of greater improvements for the placebo group in the PANSS positive subscale.

A meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials examined the efficacy of oxytocin in schizophrenia and found that oxytocin was superior to placebo for the PANSS general psychopathology scale, and was not different from placebo for PANSS total symptoms, positive or negative symptoms.69 However, when the researchers removed the study of Davis et al,28 due to intermittent administration of drug, the meta-analysis found improvement in negative symptoms. A meta-analysis of Sabe suggested that oxytocin might benefit negative symptoms, particularly if given at higher doses.30 Our findings failed to find oxytocin to significantly alter negative symptoms, particularly in the social skill training group.

Two studies similar to ours combined psychotherapy and oxytocin. Davis et al28 and Cacciotti-Saija et al,33 administered oxytocin and social skills training to schizophrenia patients for a period of 6 weeks. Both studies did not find improvements in positive symptoms.

Strengths and Limitations

Although we had a relative small sample size, this was the third-largest study on oxytocin in schizophrenia. Studies with larger sample sizes might yield more information on oxytocin’s potential as a therapeutic molecule. We cannot rule out that a dose higher than ours might be efficacious. Social functioning is complex, and we cannot rule out the possibility of oxytocin effecting some aspects not captured by our measures.

We administered oxytocin chronically for 3 weeks and at the end of study visit we administered the last dose 30 min before the assessment of social interactions. For that reason, we could not separate the influence of daily administration over the 3 week study period, from that of the last single administration. Scheduling an additional visit at least 3 days after the cessation of treatment, would have enabled us to differentiate between these possibilities. Oxytocin was administered 30 min before the social skills training or psychotherapy so that these treatments occurred when Oxytocin plasma and brain levels may have been elevated. However, previous studies have failed to find a difference between intranasal oxytocin and placebo among schizophrenia patients, even 20 h after the last oxytocin dose.71

An additional limitation of this study is the inclusion of subjects who were stable on antipsychotics for 2 weeks prior to randomization. This is a relatively short interval of medication stability, and might have led to the inclusion of patients who might not have been clinically stable, with potentially increased variability and reduced ability to discern a therapeutic effect of the experimental intervention.

The current study had a gender imbalance, with 38 males and 8 females, thus limiting the ability to make any gender-specific inferences. Also, tolerance and compliance were not measured and might have affected outcomes. However, other studies on intranasal oxytocin did not report significant side effects.

A major strength of this study was the inclusion of a “real-life” outcome measure, which has never used in schizophrenia studies testing oxytocin before. It is somewhat similar to another study, which assessed social skills in schizophrenia patients during role-playing after 6 weeks of oxytocin administration.25 That study also found no significant change in the quality of the interaction during rule playing in the oxytocin group.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study’s findings do not support the use of oxytocin, social skills training, or the combination of both as a treatment for schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

Prof. Weiser has received advisory board/speaker’s fees/consultant fees/owns stock from Dexcel, Janssen, Lundbeck, Minerva, Pfizer, Acadia, Roche, and Teva. He reports personal fees from Stanley Medical Research Institute, outside the submitted work. Prof. Davidson is an employee and owns stock options of Minerva Neurosciences a Biotech developing CNS drugs. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

This work was supported by the Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI)—Grant 11T-012. SMRI had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.