-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Söhnke M Bartram, Jennifer Conrad, Jongsub Lee, Marti G Subrahmanyam, Credit Default Swaps around the World, The Review of Financial Studies, Volume 35, Issue 5, May 2022, Pages 2464–2524, https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhab092

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We analyze the impact of the introduction of credit default swaps (CDSs) on real decision-making within the firm. Our structural model predicts that CDS introduction increases debt capacity more when uncertainty about the credit events that trigger CDS payment is lower. Using a sample of more than 56,000 firms across 51 countries, we find that CDSs increase leverage more in legal and market environments where uncertainty about CDS obligations is reduced and when property rights are weaker. Our results highlight the importance of legal uncertainty in the interpretation of the underlying trigger events of global credit derivatives.

A growing literature examines the influence of a country’s legal system on financial outcomes. In an early paper, La Porta et al. (2000) suggest that differences in countries’ legal systems and the enforcement of laws can be linked to cross-country variation in the size of capital markets, firms’ access to those markets, and ownership concentration in firms. Klapper and Love (2004) present evidence that firm-level corporate governance matters more in countries that have relatively weak legal environments. Beltratti and Stulz (2012) argue that differences in the law and regulation of the banking sector, as well as differences in corporate governance, can explain a significant proportion of cross-country differences in banks’ performance in the 2007–2008 credit crisis. Christensen, Hail, and Leuz (2016) examine changes in EU market regulation across European countries and find significant differences in the effect of these directives, with liquidity benefits stronger in countries that have stricter implementation and enforcement of rules, as well as higher-quality regulatory procedures. Overall, these papers and other research that followed provide strong evidence that the legal environment is an important determinant of the characteristics of capital markets, whether and how firms access these markets, and the structure and effects of corporate governance inside firms.

In this paper, we contribute to this literature on law and finance by empirically analyzing the impact of the introduction of credit default swaps (CDSs) on a cross-country sample of firms. This setting offers significant advantages when analyzing the effect of the legal environment on the firm. Existing research argues that the introduction of CDSs can significantly affect decisions made by the firm; given the mechanisms described in these papers, this impact crucially depends on the legal and market environment that the firm faces.1 In particular, the extent to which CDS contracts, which are typically governed by English or U.S. law, affect creditor rights depends on the benchmark rights that creditors have in the absence of CDSs. These benchmark rights differ across countries and depend on a country’s existing bankruptcy codes, contract enforcement, and corporate governance mechanisms. In addition, although models suggest that the impact of CDS introduction may differ substantially across countries, existing empirical work has examined these effects primarily in North American firms. In sharp contrast, we examine whether cross-country differences in institutional structures, particularly with regard to the legal codes governing the firm, influence the impact of the introduction of CDS trading on the underlying corporate financial policies. Our results provide insight into the importance of specific aspects of the legal environment for key economic quantities, such as the capital structure of firms. Indeed, the results of existing work suggest that, at the country level, creditor rights and the quality of the legal system are important determinants of the depth of credit markets. For example, Djankov, McLiesh, and Shleifer (2007) report that, in a sample of 129 countries, an increase in a (combined) creditor rights index of one unit is associated with an increase in the ratio of private credit to gross domestic product (GDP) of almost 6|$\%$|. In contrast, a decrease in the quality of the legal system, measured by the number of days that contract enforcement requires, is associated with a significant decrease in the ratio of private credit to GDP.

To motivate our tests, we begin with the Bolton and Oehmke (2011) model of the ‘empty creditor’ problem, where CDSs can substantially change the relation between the firm and its creditors in distress by attenuating or severing the link between cash flow rights and control rights. In the limit, an individual who holds both CDS and the underlying debt may have little or no interest in the (efficient) continuation of the firm (see, e.g., Bartram 2019; Hu and Black 2008a,b; Bolton and Oehmke 2011). We extend this structural framework to allow for uncertainty regarding whether an action taken by a firm triggers a credit event for CDSs held on the firm’s debt. This uncertainty captures differences in the way that local bankruptcy codes interact with the standardized definitions of CDS contract terms established by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). If there is less uncertainty that a particular action will trigger payments related to CDSs, the environment is considered more creditor friendly. For plausible parameter values, we demonstrate that the introduction of CDSs increases debt capacity more in regimes with less uncertainty regarding credit events. The intuition is similar to that of Bolton and Oehmke (2011): well-functioning credit derivative contracts, such as CDSs, can allow firms to overcome limited-commitment problems that arise due to weak institutional heritages. However, these benefits are larger when there is less uncertainty about the enforcement of obligations due under the swap contracts. Overall, the results from our extended model highlight that the real effects of CDSs on reference entities depend on features of the home country’s legal environment.2

We conduct our empirical analysis using a sample of more than 56,000 firms from 51 countries during the period 2001–2015. The use of an international sample provides us with cross-sectional variation in the legal environment, particularly creditor rights, which may influence the effect of the introduction of CDSs. In addition, our international sample also has cross-country variation in other dimensions, such as the degree of contract enforceability and the degree of shareholders’ ownership concentration. Existing theory implies that these features of the legal and market environment can be important determinants of the effects of CDS introduction, and a global sample may allow for better inferences about whether these variables play a significant role in those effects. To our knowledge, this research is the first to empirically analyze the consequences of CDS trading for nonfinancial firms in a global context Therefore, it also provides the first detailed, large-scale, out-of-sample evidence for the effect of CDSs on corporate financial policies beyond prior U.S. studies.3

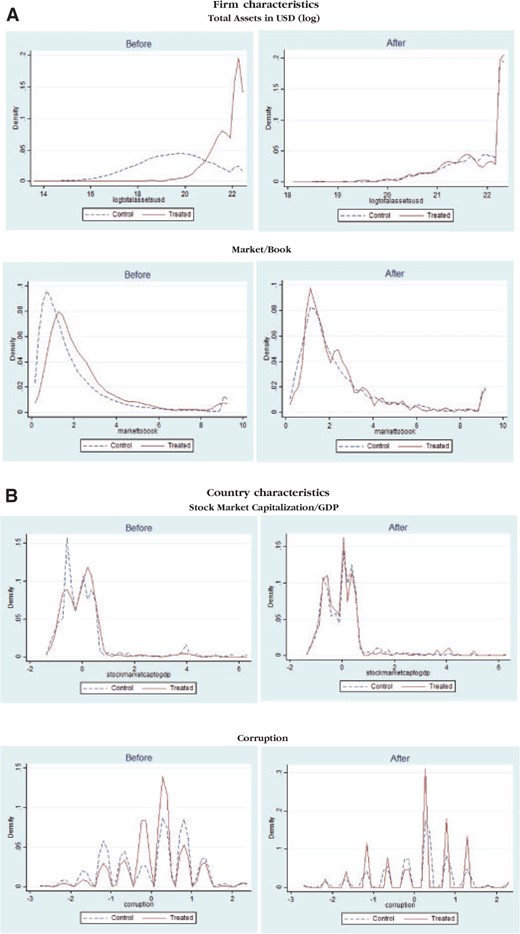

An analysis of the effects of CDS introduction must, by necessity, consider endogeneity biases, since CDS introduction is not random. These potential biases may be related to characteristics of firms, as well as to key attributes of firms’ home countries. We address these concerns using a relatively new econometric technique that has not previously been used in the finance literature. We first estimate the market’s propensity to introduce CDSs to firms, using an extensive array of firm and country characteristics, and then use the resultant propensity scores as a weighting mechanism for the sample in our analysis. This novel “overlap weighting” approach, developed by Li, Morgan, and Zaslavsky (2018), generates similar distributions of all firm- and country-level covariates across CDS firms and non-CDS firms and allows us to make causal inferences on the effects of CDS introduction on corporate financial and investment policies. Although we use a wide array of covariates, we also conduct a sensitivity analysis to examine whether our results are affected by omitted variable bias.

Our results indicate that after CDS introductions the underlying firms increase leverage in countries that have stronger creditor rights along specific dimensions. The first dimension is the requirement for creditor consent in order to enter reorganization, which can act as a trigger for CDS obligations. This result is consistent with the predictions of our theoretical framework: creditors with CDS protection and control over shareholders’ entry into reorganization have substantially higher bargaining power, allowing the firms to overcome the limited-commitment problem related to the ex ante issuance of debt. Indeed, the private renegotiation setting is also the one in which Bolton and Oehmke (2011, 2631) argue that the “main effect of CDS protection” occurs, since it is in this instance that the swaps improve the lender’s bargaining position.

The second dimension that influences the impact of CDS introduction is the requirement that secured creditors be paid first out of liquidation proceeds. This indicates that leverage increases are greater when liquidation costs are low, particularly when ex post excessive liquidation pressure may come from empty creditors with CDS protection.

We also find that underlying firms increase leverage more in countries with weaker contract enforceability, and if their equity ownership is more concentrated, as shareholders would have greater bargaining power. These results indicate that the introduction of CDSs can act as a substitute for weak property rights, especially in situations in which poor enforceability of property rights is a constraint on the supply of credit in the domestic capital market. This is consistent with the finding of Bae and Goyal (2009) that, along with creditor rights, property rights are an important determinant of the credit available to firms. In addition, newly introduced CDS contracts effectively enhance the debt capacity of underlying reference entities when creditors initially have an inferior bargaining position with respect to majority shareholders (Davydenko and Strebulaev 2007), who would have more bargaining power during private debt renegotiation in the absence of CDSs.

We perform a number of robustness checks on our results. In addition to the sensitivity analysis of omitted variables mentioned above, these tests include the use of additional control variables; a test of the conditional independence of our treatment assignment using alternative ordinary least squares (OLS) estimations; the use of CDS existence rather than CDS introduction as the variable of interest; an analysis of a subsample that excludes U.S. firms (as well as other country filters); an analysis that excludes potential “national champions” from the sample; and longer-horizon effects of CDS introductions. The results from these tests remain qualitatively and quantitatively similar.

Although our primary focus is on financing effects, we also briefly explore the effects of CDS introduction on investment, to better understand whether observed effects on leverage have implications for firms’ assets. These results show that the interaction between CDS contracts and local bankruptcy codes also influences the investment policies of firms. Specifically, in cases with creditor restrictions on firms’ entry into bankruptcy, the presence of CDSs increases the level of capital investment of firms.

1. Review of the Related Literature

While financial derivatives have been around for more than three decades, CDS are a much more recent phenomenon. Given the role of CDSs in the recent financial crisis (Stulz 2010), the existing literature has focused primarily on their role with regard to financial institutions. Similarly, the European sovereign debt crisis has triggered interest in using CDS to study sovereign risk (see, e.g., Acharya, Drechsler, and Schnabl 2014; Lee, Naranjo, and Sirmans 2016). In contrast, while an extensive literature has investigated the use of derivatives on currencies, interest rates, and commodity prices by nonfinancial firms and the underlying frictions that justify their existence (see, e.g., Bartram 2019; Bartram, Brown, and Conrad 2011; Bartram, Brown, and Fehle 2009), much less attention has been paid to the effect of CDSs on these firms.4 Like equity derivatives, CDS are typically not held by the reference entity; that is, nonfinancial firms are generally not CDS users. Rather, some of their claimholders (e.g., bondholders) may use CDS contracts for hedging or speculative purposes. Nevertheless, a developing, relatively recent literature suggests that CDS may still affect various corporate policies of the underlying firms.5

Although CDS are, in theory, redundant derivative assets, existing research indicates that market frictions related to these contracts are nontrivial, and hence that the introduction of CDSs can have significant effects on security prices, economic incentives, and investor and firm behavior. These effects drive a wedge between the payoffs on the underlying asset (the firm’s assets) and the payoff on the derivative instrument (the CDS contract).6 No consensus has been reached in the literature about the net impact of CDSs on the underlying firms. CDSs can clearly provide better hedging opportunities for lenders, but these opportunities may be associated with inefficiencies, such as excessive liquidation, reduced monitoring by lenders, and increased losses to creditors in default. However, by improving creditor rights, CDSs also may be associated with higher leverage, greater levels of investment, and less-frequent strategic default. Importantly, all of these effects are related to the creditor rights, property rights, and market framework in which the underlying entity operates. As noted above, this framework includes bankruptcy codes, contract enforcement, and corporate governance mechanisms.

The existing empirical work provides evidence that U.S. firms with CDSs have higher leverage ratios and longer debt maturity (Saretto and Tookes 2013), though only limited evidence suggests that the greater use of credit derivatives is associated with the greater supply of bank credit (Hirtle 2009). The existence of CDS does not affect the cost of debt on average, but riskier firms experience an increase in spreads, while safer firms, as well as those firms with a priori high strategic default incentives, experience a decline in spreads (see Ashcraft and Santos 2009; Kim 2016).

Evidence on the effect of CDSs on firms’ risk is mixed. Several papers present evidence that the credit risk of firms increases when CDS are introduced. For example, Peristiani and Savino (2011) and Subrahmanyam, Tang, and Wang (2014) report that U.S. firms’ credit ratings tend to decline and bankruptcy risk increases following CDS introduction, and Colonnello, Efing, and Zucchi (2019) show that CDS increase the bankruptcy risk and lower the value of firms with powerful shareholders. Narayanan and Uzmanoglu (2018) show that firm value declines as a result of increased costs of capital and lower credit quality when CDS are initiated. In contrast, Caglio, Darst, and Parolin (2019) employ transaction-level data to build a new aggregate measure of CDS use and find that CDS positions of the largest U.S. banks do not adversely affect borrower credit risk, even for lenders that overinsure against credit losses. Bedendo, Cathcart, El-Jahel (2016) do not find an association between CDS and credit deterioration, and Chakraborty, Chava, and Ganduri (2015) show that CDS firms do not go bankrupt at a higher rate.

A smaller set of papers examine the effect of CDSs on investment. Chakraborty, Chava, and Ganduri (2015) find that firms with CDSs decrease investment after covenant violations. Narayanan and Uzmanoglu (2018) present evidence that investment declines with CDS initiation. Danis and Gamba (2018) develop a model that shows that firms increase leverage and invest more after the introduction of CDSs.

While the evidence to date indicates that CDS contracts have significant effects on the financial decisions of firms, the reference entities in almost all of these papers are headquartered in North America and, as a result, are subject to similar legal environments. The results of our theoretical framework indicate that the effects of CDS introduction on leverage should be larger in countries with creditor-friendly bankruptcy codes, weaker contract enforceability, and higher concentration of shareholder ownership. Consequently, in our empirical tests, we allow the impact of CDS introduction to differ with variation in the governance and legal environments in which the underlying reference entities operate.

2. CDS and the Local Legal Environment

A single-name CDS contract specifies the underlying reference entity; the maturity of the contract; the ongoing payments that are required to be made by the protection buyer to the protection seller; the definition of the credit events that would trigger an obligation due from the protection seller to the protection buyer; the manner in which the payments from seller to buyer will be determined; and the manner in which the contractual securities may be delivered (physically or otherwise) will be set. There are six CDS trigger events: bankruptcy, obligation acceleration, obligation default, failure to pay, repudiation/moratorium, and restructuring. Three of these—bankruptcy, failure to pay, and restructuring—are principal credit events for corporate CDSs. When a trigger event occurs, CDS are settled through credit-default auctions, in which final recovery rates are determined through dealer bids, and the contract counterparties are settled accordingly either in cash or with the physical delivery of the underlying debt obligations.

CDS contracts are typically governed by rules established by the ISDA and make use of a standard set of clauses set out in the ISDA Master Agreement. Despite standard language, in the early days of CDS contracts there were significant disagreements and subsequent litigation over contract terms, including whether credit events had actually occurred, and thus whether obligations had been triggered. Over the last 15 years, the ISDA has instituted changes in its Master Agreement in order to minimize ambiguity, create a more homogeneous CDS product, reduce counterparty risk, and streamline the processes through which settlement payments are determined. The most significant changes were included in the Big Bang Protocol in 2009. This protocol sets up regional Determination Committees (DCs) to consider whether a credit event has occurred, and to manage the auction process through which final CDS payments are settled. It also created common “look-back” provisions for credit events to reduce basis risk for CDS traders. In addition, restructuring was excluded as a credit event for North American reference entities (although this was retained as a potential credit event in the rest of the world).

While these changes have created a more standardized CDS contract, the legal environment in which a reference entity operates is still important. Historically, Chapter 11 proceedings in the United States are the most common CDS credit event trigger in the world, but reference entities that operate outside the United States are subject to bankruptcy provisions that differ in the strength of their creditor protections, including the grants of automatic stays, prohibitions on debt payments, preservation of legal rights, and the length and timing of the resolution process. For CDS contracts, these differences influence decisions regarding whether a credit event has occurred and could also influence the timing of settlement auctions in cases in which a credit event is deemed to have occurred.

For example, ISDA’s EMEA (Europe) DC reached a surprising split decision on whether CDS were triggered upon the bankruptcy filing by Abengoa, a Spanish reference entity. In this case, local Spanish insolvency law and the global ISDA credit event definition provided conflicting interpretations of the nature of the underlying credit event.7 In Appendix A, we provide more details on the Abengoa case, as well as an example of another recent case in which the consideration of specific elements of a country’s bankruptcy code played an important role in the enforcement of CDS.

As these examples demonstrate, there can be significant legal issues to consider in the determination of contingent payoffs associated with CDS contracts. These issues motivate our analysis of the ways in which local bankruptcy provisions affect the enforcement of single-name CDS contracts and, as a result, the payoffs of the firms’ creditors. In our formal model, we take into account this uncertainty about whether actions taken by the firm trigger payments due under the CDS contract.

3. Data

Our sample consists of all firms that have market data available on Datastream and accounting data available on WorldScope. We exclude financial firms, specifically, banks, insurance companies, real estate and other investment trusts, etc. with SIC codes 60–69. We also exclude all firm-year observations that have zero or negative values for total assets. Further, we exclude nonprimary issues, U.S. OTC Bulletin Board and “Pink Sheet” stocks, and firms that have missing country or firm identifiers. Our final sample consists of an unbalanced panel of more than 56,000 firms across 51 countries over the period 2001–2015. For these firms, we obtain monthly stock returns in U.S. dollars (USD), and market capitalization (in both USD and local currency) for individual stocks, as well as returns on the value-weighted local and global Datastream stock market indexes. Accounting variables are in millions of units of local currency and include determinants of CDS availability as well as general firm characteristics (such as total assets, sales, profitability, leverage, and cash and short-term investments). All firm-level variables are winsorized at the top and bottom five percentiles, with logical limits applied to mitigate the effect of data errors.

Industry fixed effects are based on the Fama-French 48-industry classification. Various legal, institutional, and financial market characteristics across countries are obtained from the data available from other existing studies (La Porta et al. 1998; Djankov, McLiesh, and Shleifer 2007; Djankov, Hart, et al. 2008; and others), as well as from several major cross-country databases, including those of the World Bank and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), and from PRS Group’s International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). Finally, all CDS data are obtained from Markit.

Firms are identified as reference entities if they have CDS of any maturity during the observation year. Because our CDS data start in 2001, we can only identify CDS introductions beginning in 2002. When we refer to CDS firms and non-CDS firms, this pertains specifically to firm-year observations with and without CDS introductions, respectively. Thus, prior to CDS introduction, firm-year observations of eventual CDS firms are treated as non-CDS firms. To focus our identification on the introduction of CDSs, we do not include in our main results any firm-year observations of CDS firms after the introduction of CDSs. Table D.1 in Appendix D provides variable definitions, and panel A of Table E.1 in Appendix E provides summary statistics for all the variables used in this paper.

4. Insights and Empirical Predictions from a Structural CDS Model

4.1 Setup

We consider a setting that is an extension of a model proposed by Bolton and Oehmke (2011).8 In this setting, we develop key insights and testable implications for our international sample. Suppose a firm raises an amount, |$B$|, of debt today (time 0) by promising a fixed payment, |$F$|, at time 1. At time 1, the firm generates a cash flow, |$C_{1}$|, which may be either |$C_1^H$| with probability |$\theta $| or |$C_1^L$| with probability |$(1 - \theta )$|, where |$C_1^L < C_1^H $| (|$H=$| “high,” |$L=$| “low”). |$C_1^L $| is normalized to zero without loss of generality. Soon after time 1, the firm’s continuation value, |$C_{2}$| (either |$C_2^H $| with probability |$\phi$| or |$C_2^L$| with probability (|$1 - \phi$|), where |$C_2^L < C_2^H )$|, is known with certainty to the firm’s shareholders. However, there is limited verifiability of the cash flow to creditors; that is, they can verify only |$C_1^L $|, but not the magnitude of |$C_1^H$|, at time 1. The continuation value of the firm, |$C_{2}$|, also cannot be verified by the firm’s creditors without incurring costs. If verification costs are paid by shareholders, the exact state of the world at time 2 is observable for both the firm’s insiders (i.e., its shareholders) and its outside claimants (i.e., creditors). We set the risk-free discount rate to zero to keep the notation simple, without loss of generality.

At time 1, if the firm fails to pay |$F$|, the firm and its creditors start private debt renegotiation. During this out-of-court debt negotiation, either creditors can liquidate the firm (e.g., via outright liquidation as in Chapter 7 of the U.S. bankruptcy law), yielding the liquidation value |$S$|, or they can get a renegotiation surplus of |$q\lambda C_{2}$|. In this surplus, the term |$\lambda C_{2}$| takes into account that only a fraction of the continuation value is available, due to the costs of private renegotiation; |$\lambda <1$|. |$\lambda C_{2}$| is therefore the maximum renegotiation surplus that accrues to both the firm and the creditors, taken together; |$q$| denotes the creditors’ bargaining power relative to that of the firm (i.e., its shareholders), which reduces the value available to the latter. Based on the insight provided by Hart and Moore (1994), liquidation is typically costlier than renegotiation (|$S < \lambda C_2^L )$| due to the destruction of the firm’s going-concern value in the event of liquidation, and hence shareholders and creditors are motivated to avoid it.

When creditors owning CDS protection reject a renegotiation offer from the firm’s shareholders, they submit a request to the DC to verify whether a credit event was, in fact, triggered.9 As discussed in Appendix A, there is significant variation in legal risk across country jurisdictions due to differences in legal frameworks and to the resultant conflicting interpretations of the definition of the underlying credit event (see also Simmons & Simmons LLP 2016). Based on this variation, we assume that there is a probability |$\varepsilon $| that a credit event is not triggered. As a specific example of this, consider a case in which the firm could credibly claim that an in-court restructuring filing is voluntary, rather than related to a credit event; this possibility would reduce the bargaining power of creditors.10

Under these circumstances, creditors with CDS credit protection with a notional value of |$N$| maximize their expected payoff during the private debt renegotiation with the firm. Their payoff is |${\it max}[q\lambda C_2^H, \gamma N]$| if |$i=H$| at time 2, where |$\gamma N = (1 - \varepsilon )N + \varepsilon M$| with |$M < N$|; and |${\it max}[q\lambda C_2^L,N]$| if |$i=L$|. In each state, the first term in the square brackets denotes the payoff to CDS creditors if they agree with the firm on debt restructuring, whereas the second term in the square brackets denotes their payoff if they reject the offer from the shareholders and take their case to the DC (or, prior to the Big Bang, the local legal authority). The new parameter |$\gamma $| captures the legal uncertainty experienced by creditors about their payoff. Note that it reduces their payoff only in the |$H$| state at time 2, in which the continuation value of the firm turns out to be high (i.e., sufficient to pay off creditors), and there is some probability |$\varepsilon $| that creditors cannot trigger CDS payments. Consequently, they receive a smaller payout, |$M$| than the contracted notional of the CDS, |$N$|.11 In contrast, when the realization at time 2 is in the |$L$| state, there is no such ambiguity regarding the nature of the trigger event, and the payoff is |$N$|12

4.2 Parameters

The key parameters in the above setting, and in the hypothesis, are |$\lambda, q, \gamma $|, and |$S$|. We provide below a description of the economic intuition behind these parameters and the variables in our data set that best capture these effects. We then derive comparative statics for the sensitivity of the change in debt capacity (due to the introduction of a CDS contract) to changes in these parameters. The parameters are as follows:

Cash flow verifiability (|$\lambda $|)

Debt renegotiation is costly when property rights are poorly enforced (see, e.g., Bae and Goyal 2009; Djankov, Hart, et al. 2008). Poor contract enforcement lowers the recovery rate and also increases the time spent in repossessing collateral during the restructuring process. These costs are captured by 1-|$\lambda $|, which is proportionately deducted from the continuation value, |$C_{2}$|. As a consequence, |$\lambda $|, or contract enforceability, should be related to the strength of property rights in the firm’s local environment. As a proxy for this parameter, we follow the literature (Bae and Goyal 2009) and use the property rights variables Law & Order, Corruption, and Political Risk from the ICRG database.

Creditors’ bargaining power during private debt renegotiation (|$q$|)

The bargaining power of creditors during the private renegotiation process—which is negatively correlated with the fraction of equity owned by a firm’s principal shareholders, such as the CEO and institutional investors (see, e.g., Davydenko and Strebulaev 2007; Dahlquist et al. 2003)—determines the share of the continuation value, |$C_{2}$|, available to creditors, with the balance going to shareholders. We use Closely Held Shares, the fraction of equity ownership held by controlling shareholders, obtained from Worldscope, as our proxy for concentration of shareholder ownership.

Trigger event uncertainty (|$\gamma $|)

A creditor-friendly local bankruptcy code implies less uncertainty in the recognition of the CDS trigger event, and therefore, a greater expected CDS payout (i.e., a higher |$\gamma $|). For instance, when the local bankruptcy codes allow creditors to limit a firm’s ability to file for an in-court restructuring that it claims is voluntary, creditors clearly have stronger bargaining power and, in particular, the uncertainty related to triggering events in CDS contracts is reduced. This aspect of creditor rights is captured by one of the components of the creditor rights index first introduced into the finance literature by La Porta et al. (1998) (LLSV). Specifically, we source the LLSV variable “Restrictions on the shareholders to enter reorganization without creditors’ consent” from Djankov et al. (2007) and assume that when creditors can restrict entry into reorganization, legal uncertainty is reduced.

Liquidation value (|$S$|)

The higher the liquidation value of the firm, or (equivalently) the lower the liquidation cost, the lower are the costs associated with the empty creditor problem. We use Secured Creditors First from Djankov et al. (2007), another subindex of the overall creditor rights index of LLSV (1998), as a proxy for liquidation values. This creditor right establishes the priority of claimants (specifically, creditors) in payments resulting from liquidation of the firm. This is also consistent with the evidence in Djankov et al. (2008), which indicates that deviations from absolute priority rules are associated with substantially lower recovery rates.

4.3 Debt pricing

Our framework, which is based on the model of Bolton and Oehmke (2011), is essentially an extended binomial model that includes ex post trigger event uncertainty regarding the bankruptcy court’s actions. In our model, along the path where the first-period cash flow is |$C_1^H $| and the continuation value turns out to be |$C_2^L $| (the up-down path), there is by construction the possibility of strategic default by shareholders in the first period. Specifically, shareholders can minimize the payment to creditors at time 1, |${\it min}\left[ {F,(1 - \lambda )C_2^L + q\lambda C_2^L} \right]$|, by threatening liquidation without truthfully revealing the actual cash flow at time 1. The first term in the square brackets denotes the cost to shareholders if the firm truthfully reveals its time 1 cash flow (|$C_1^H $|) and pays |$F$|. The second term indicates the consequences of strategic default; in that case, the shareholders’ outlay is the sum of the verification cost of continuation value during private debt renegotiation (|$(1 - \lambda )C_2^L $|) and the portion of the renegotiation surplus that shareholders give up to the benefit of creditors (|$q\lambda C_2^L $|). (Note that this formulation assumes that the verification costs are paid entirely out of the firm’s resources.) If honoring the original contract is not costly (|$F \le (1 - \lambda )C_2^L + q\lambda C_2^L $|), the firm does not attempt strategic default; otherwise, it does.

Proposition 1 presents the comparative statics of the model. Note that the first relation is novel to our framework, while the remaining three are related to parameters in Bolton and Oehmke (2011) and hence are implied by that model.

The introduction of CDS contracts on a firm’s debt increases its debt capacity

(a) the less the trigger event uncertainty in the bankruptcy codes of the country in which the firm operates |$\left({\frac{\partial \Delta B}{\partial \gamma } \ge 0} \right)$|,

(b) the higher the liquidation value of the firm’s assets |$\left({\frac{\partial \Delta B}{\partial S } > 0} \right)$|,

(c) the weaker the contract enforceability in the jurisdiction in which the debt is issued |$\left( {\frac{\partial \Delta B}{\partial \lambda} < 0} \right)$|, and

(d) the more closely held the shares in the firm |$\left( {\frac{\partial \Delta B}{\partial q} < 0} \right)$|.

See Appendix C. ■

When the enforcement of debt contracts faces significant limited-commitment problems due to a weak institutional environment (low |$\lambda $|, low |$q$|), well-functioning credit derivatives contracts, such as CDSs, can help firms overcome such institutional barriers. However, when the contingent payoff of the derivatives is affected by local legal regimes (low |$\gamma $|), the effects of the CDS contract may be significantly limited. Moreover, when creditors overinsure their debt positions through CDS contracts, liquidation becomes more likely than successful private renegotiation. Under such circumstances, a higher liquidation value helps reduce the cost of debt capital that the firm must raise for its positive net present value investments.

4.4 Empirical predictions

Based on the insights from the extended Bolton and Oehmke (2011) model presented above, we derive the following formal hypothesis:16

The introduction of CDSs will increase debt capacity more for firms in countries with less legal uncertainty around triggering events; low liquidation cost; weak contract enforceability; and more concentrated shareholder ownership.

5. Methodology

The decision of whether to introduce CDSs to an individual firm headquartered in a particular country is endogenous and may be affected by characteristics of both the firm and the country. For instance, it may well be that CDS contracts are introduced on levered firms that are already distressed and are likely to face a higher probability of default. In addition, the introduction of such contracts may be affected by the stage of development of equity, debt, and derivatives markets; property rights; or bankruptcy codes in that country. If such endogeneity is not taken into account, estimates of the effect of CDS introduction could be biased, since the firms that have CDS introduced on them (i.e., the treated firms) or the countries in which CDS are introduced may differ on relevant dimensions from firms or countries that do not have CDS introductions. That is, measured differences in the outcomes of CDS introduction may be due to differences in firms’ or countries’ characteristics, or covariates, rather than to the introduction of the CDS themselves.

Other studies have addressed this concern through the use of firm-specific instruments for CDS introduction. However, in an international sample, the standard instrumental variable regression approaches widely used in U.S. samples in the literature are unlikely to satisfy the exclusion restriction due to additional confounding factors at the country level. For example, instruments, such as banks’ use of foreign exchange derivatives, used in Saretto and Tookes (2013) may be correlated with the emergence of CDS markets in different countries and may therefore be related to features of the countries’ debt markets. Similarly, lenders’ capital ratios and portfolio concentration measures, which also have been used in the literature (see, e.g., Saretto and Tookes 2013; Subrahmanyam, Tang, and Wang 2014; Shan, Tang, and Yan 2016) can be confounded with banking regulations that may also affect the availability of CDSs to borrowers from the same country as the lenders. However, imposing restrictions on these lenders and borrowers by requiring that they reside in different countries results in a very significant (|$>$| 90|$\%$|) reduction in sample size and a loss of power in our statistical tests. Such restrictions also introduce the possibility of selection biases associated with factors related to firms’ foreign financing opportunities.17 In addition to selection bias, imposing additional data availability restrictions will necessarily reduce variability in the legal, financial, and political environments that we consider, and as a consequence may reduce the precision of our estimates.

We take endogeneity into account through our choice of empirical method. This method, propensity weighting, is relatively new and, to our knowledge, has not been used previously in the finance literature. This weighting was developed by Li, Morgan, and Zaslavsky (2018), who term these weights “overlap weights,” since the method creates a sample with the most overlap in covariates between the treated and nontreated groups. The intuition behind the method is fairly straightforward. We begin by estimating the probability that individual firms will experience a CDS introduction. This step is similar to the method used for propensity-score matching. However, matching may reduce sample size, particularly in settings with multiple sets of characteristics to take into account (e.g., firm and country characteristics). Propensity weighting, in contrast, uses every observation in the sample with a positive probability of being included in both the treated and control groups.

Instead of matching, we use the estimated propensities to reweight observations in the sample in order to reduce differences in the characteristics of treated and nontreated firms. In effect, this method creates a synthetic sample for which the distribution of pretreatment variables, or covariates, is balanced across treated and nontreated firms. In this synthetic sample, there is no correlation between the treatment and the observed covariates. In addition, the size of the synthetic sample is typically much larger than that in the matching analysis, which is a particular advantage in our case as the number of firms that have CDS introduced on them is small in comparison to the total number of firms in the sample.

Specifically, consider a sample of |$n$| firms. Each firm can belong to one of two groups, where |$Z_{it}$| is the (binary) variable that indicates group membership in year |$t$|; in our case, |$Z_{it} = 1$| represents the treatment, or the case in which a CDS is introduced on the firm. For each firm, we observe an outcome |$Y_{it}$| and a |$k$|-dimensional set of covariates |$X_{ikt}$| in each year |$t$|. The propensity score is the probability that we observe a CDS introduction, given the covariates: |$p_{it}(x_{t}) =$| Pr (|$Z_{it} = 1| X_{ikt}=x_{t})$|.

Note that this method weights each individual firm (treated or nontreated) by the probability that it will be assigned to the opposing group (nontreated or treated, respectively). Consider an individual firm that has a high estimated propensity for treatment and does, in fact, receive the treatment; this type of firm is relatively common, as it has covariate values that are comparable to those of other treated firms. Such a firm will be down-weighted to account for the commonness of its observation. In contrast, a treated firm with a low predicted probability of being treated will receive a higher weight. As a result, individual firms with a low (high) predicted probability of treatment that actually receive the treatment will be up- (down-)weighted; the up-weighting allows the low-propensity treated firm to represent a larger group of similar firms that did not receive the treatment. Similarly, for nontreated firms, those with a high (low) probability of treatment will be up- (down-)weighted. This weighting of observations yields a synthetic sample of treated and nontreated firms with balanced covariates by construction.18

The method proposed by Li, Morgan, and Zaslavsky (2018) is related to inverse probability weighting, as described by Hirano and Imbens (2001). As the name suggests, inverse probability weighting uses the reciprocal of the estimated propensity for treatment to weight observations in the sample. However, inverse probability weighting has the drawback that when estimated probabilities are very small, weights can become extremely large and the resultant estimates become unstable. Rescaling of weights or arbitrary truncation/winsorization of extreme weights is typically used to address this problem. In contrast, the overlap weights proposed by Li, Morgan, and Zaslavsky (2018), which we use in this paper, are bounded between 0 and 1, do not require truncation, result in exact balance of the covariates, and, for plausible distributions of propensity weights, are associated with smaller standard errors in the estimates of treatment effects. Intuitively, the overlap weighting method results in a synthetic sample that can be interpreted as the set of firms that have a substantial probability both of having CDS introduced and of not having CDS contracts available. We estimate the effects of CDS introduction on this propensity-weighted sample.

In Section 6.5, we analyze the robustness of our results along a number of additional dimensions. These tests include a simulation-based analysis of the sensitivity of our main results to potential omitted variable biases (Ichino, Mealli, and Nannicini 2008), and the use of additional controls in the propensity-weighting method. We also confirm the key conditional independence of our treatment assignment using alternative OLS estimations. In addition, we reestimate the effects of CDSs using CDS existence as the variable of interest, rather than CDS introduction; we also examine the robustness of the results when we exclude the set of firms that may be considered “national champions,” since these firms may be perceived as having meaningfully different probabilities of default.19 Finally, we examine the sensitivity of our inferences to the exclusion of U.S. firms from the sample and analyze the longer-horizon effects of CDS introduction.

6. Results

6.1 CDS availability and introductions

Table 1 reports the summary statistics of the sample by country and by industry. In panel A, we report the number of firms with available CDS by country and by year. Each year, on average, 1,225 firms have available CDSs. CDS availability is more common in developed countries: CDS on firms in the United States and Japan make up more than 62|$\%$| of the sample. Other developed countries, such as the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Canada, also have a relatively high proportion of CDS firms. Note, however, that developed countries differ significantly with regards to the country characteristics we consider. For example, the G7 countries span the entire spectrum of creditor rights, as defined in Djankov et al. (2007), from France (with the minimum creditor rights score of 0), to Japan (with a creditor rights score of 2) and the United Kingdom (with the maximum creditor rights score of 4). In addition to this variation in country characteristics among large, developed countries, in recent years the number of firms with available CDS has increased in smaller and/or less developed countries, such as India, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore.20 The number of CDS introductions by country and year are reported in panel B. CDS introductions were relatively numerous prior to the financial crisis, with the number of introductions declining sharply after 2007. Importantly, note that the majority of CDS firms and introductions in our sample are in countries other than the United States, which has been the focus of prior CDS studies.

| A. CDS availability by country and year . | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2001 . | 2002 . | 2003 . | 2004 . | 2005 . | 2006 . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011 . | 2012 . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | Average . | Creditor Rights . |

| Hong Kong | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 21 | 30 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 39 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 7 | 26 | 4 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| United Kingdom | 31 | 48 | 62 | 65 | 66 | 69 | 64 | 59 | 58 | 58 | 60 | 60 | 55 | 58 | 32 | 56 | 4 |

| Australia | 9 | 17 | 20 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 21 | 3 |

| Austria | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Czech Republic | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Denmark | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Germany | 17 | 20 | 29 | 36 | 37 | 40 | 41 | 43 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 10 | 36 | 3 |

| Israel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Korea, Republic Of | 4 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 18 | 3 | |

| Malaysia | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Netherlands | 8 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 3 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Singapore | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| South Africa | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |||

| Belgium | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Chile | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | |||

| Egypt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| India | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 32 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 51 | 52 | 43 | 33 | 2 | |

| Indonesia | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 2 | |||||

| Italy | 7 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 19 | 22 | 23 | 17 | 2 | |

| Japan | 27 | 61 | 121 | 202 | 247 | 267 | 285 | 289 | 288 | 286 | 282 | 278 | 280 | 276 | 255 | 230 | 2 |

| Kazakhstan | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Norway | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | |

| Romania | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Russian Federation | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |||||

| Spain | 5 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 2 | |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Taiwan | 6 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 23 | 2 | |||

| Thailand | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 2 | ||

| Turkey | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Argentina | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Brazil | 2 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 1 | ||||

| Canada | 9 | 18 | 25 | 37 | 42 | 42 | 39 | 39 | 37 | 37 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 3 | 31 | 1 |

| Finland | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | |

| Greece | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Hungary | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Ireland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Philippines | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Poland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Portugal | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Sweden | 7 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 1 |

| Switzerland | 4 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 1 | |

| United States | 251 | 347 | 447 | 566 | 615 | 641 | 670 | 661 | 655 | 634 | 626 | 623 | 609 | 599 | 130 | 538 | 1 |

| Colombia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||

| France | 28 | 36 | 42 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 45 | 43 | 42 | 43 | 45 | 47 | 48 | 4 | 40 | 0 |

| Mexico | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 0 | |||

| Bahrain | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Luxembourg | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Qatar | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Total | 427 | 631 | 849 | 1,117 | 1,271 | 1,365 | 1,449 | 1,483 | 1,485 | 1,462 | 1,455 | 1,467 | 1,450 | 1,445 | 519 | 1,225 | |

| A. CDS availability by country and year . | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2001 . | 2002 . | 2003 . | 2004 . | 2005 . | 2006 . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011 . | 2012 . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | Average . | Creditor Rights . |

| Hong Kong | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 21 | 30 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 39 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 7 | 26 | 4 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| United Kingdom | 31 | 48 | 62 | 65 | 66 | 69 | 64 | 59 | 58 | 58 | 60 | 60 | 55 | 58 | 32 | 56 | 4 |

| Australia | 9 | 17 | 20 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 21 | 3 |

| Austria | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Czech Republic | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Denmark | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Germany | 17 | 20 | 29 | 36 | 37 | 40 | 41 | 43 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 10 | 36 | 3 |

| Israel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Korea, Republic Of | 4 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 18 | 3 | |

| Malaysia | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Netherlands | 8 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 3 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Singapore | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| South Africa | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |||

| Belgium | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Chile | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | |||

| Egypt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| India | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 32 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 51 | 52 | 43 | 33 | 2 | |

| Indonesia | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 2 | |||||

| Italy | 7 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 19 | 22 | 23 | 17 | 2 | |

| Japan | 27 | 61 | 121 | 202 | 247 | 267 | 285 | 289 | 288 | 286 | 282 | 278 | 280 | 276 | 255 | 230 | 2 |

| Kazakhstan | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Norway | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | |

| Romania | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Russian Federation | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |||||

| Spain | 5 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 2 | |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Taiwan | 6 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 23 | 2 | |||

| Thailand | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 2 | ||

| Turkey | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Argentina | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Brazil | 2 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 1 | ||||

| Canada | 9 | 18 | 25 | 37 | 42 | 42 | 39 | 39 | 37 | 37 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 3 | 31 | 1 |

| Finland | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | |

| Greece | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Hungary | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Ireland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Philippines | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Poland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Portugal | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Sweden | 7 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 1 |

| Switzerland | 4 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 1 | |

| United States | 251 | 347 | 447 | 566 | 615 | 641 | 670 | 661 | 655 | 634 | 626 | 623 | 609 | 599 | 130 | 538 | 1 |

| Colombia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||

| France | 28 | 36 | 42 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 45 | 43 | 42 | 43 | 45 | 47 | 48 | 4 | 40 | 0 |

| Mexico | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 0 | |||

| Bahrain | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Luxembourg | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Qatar | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Total | 427 | 631 | 849 | 1,117 | 1,271 | 1,365 | 1,449 | 1,483 | 1,485 | 1,462 | 1,455 | 1,467 | 1,450 | 1,445 | 519 | 1,225 | |

| B. CDS introductions by country and year . | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2002 . | 2003 . | 2004 . | 2005 . | 2006 . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011 . | 2012 . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | Total . | CreditorRights . |

| Hong Kong | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 42 | 4 | |||

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 18 | 14 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 61 | 4 | |||

| Australia | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 3 | |||||||

| Austria | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | |||||||||

| Czech Republic | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Denmark | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Germany | 4 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 34 | 3 | |||||

| Israel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Korea, Republic Of | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 23 | 3 | |||

| Malaysia | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Netherlands | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 3 | ||||||||

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Singapore | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 3 | |||||||

| South Africa | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | |||||||||

| Belgium | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Chile | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 | ||||||||

| Egypt | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| India | 1 | 5 | 9 | 17 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 57 | 2 | ||||||

| Indonesia | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Italy | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 18 | 2 | |||

| Japan | 34 | 62 | 81 | 46 | 24 | 20 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 288 | 2 | |||

| Kazakhstan | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Norway | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Romania | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Russian Federation | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Spain | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 2 | ||||||||

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Taiwan | 6 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 29 | 2 | |||||||

| Thailand | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 12 | 2 | |||||||||

| Turkey | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Argentina | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Brazil | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 17 | 1 | ||||||||

| Canada | 9 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 42 | 1 | ||||

| Finland | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Greece | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Hungary | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Ireland | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Philippines | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | ||||||||

| Poland | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Portugal | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Sweden | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Switzerland | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 1 | |||||||||

| United States | 105 | 116 | 113 | 74 | 46 | 67 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 593 | 1 |

| Colombia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| France | 10 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 28 | 0 | |||||

| Mexico | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 0 | |||||||

| Bahrain | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Luxembourg | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Qatar | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Total | 218 | 237 | 266 | 187 | 128 | 147 | 80 | 38 | 19 | 31 | 41 | 17 | 11 | 1 | 1,421 | |

| B. CDS introductions by country and year . | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2002 . | 2003 . | 2004 . | 2005 . | 2006 . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011 . | 2012 . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | Total . | CreditorRights . |

| Hong Kong | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 42 | 4 | |||

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 18 | 14 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 61 | 4 | |||

| Australia | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 3 | |||||||

| Austria | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | |||||||||

| Czech Republic | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Denmark | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Germany | 4 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 34 | 3 | |||||

| Israel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Korea, Republic Of | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 23 | 3 | |||

| Malaysia | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Netherlands | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 3 | ||||||||

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Singapore | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 3 | |||||||

| South Africa | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | |||||||||

| Belgium | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Chile | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 | ||||||||

| Egypt | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| India | 1 | 5 | 9 | 17 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 57 | 2 | ||||||

| Indonesia | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Italy | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 18 | 2 | |||

| Japan | 34 | 62 | 81 | 46 | 24 | 20 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 288 | 2 | |||

| Kazakhstan | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Norway | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Romania | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Russian Federation | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Spain | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 2 | ||||||||

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Taiwan | 6 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 29 | 2 | |||||||

| Thailand | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 12 | 2 | |||||||||

| Turkey | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Argentina | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Brazil | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 17 | 1 | ||||||||

| Canada | 9 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 42 | 1 | ||||

| Finland | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Greece | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Hungary | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Ireland | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Philippines | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | ||||||||

| Poland | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Portugal | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Sweden | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Switzerland | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 1 | |||||||||

| United States | 105 | 116 | 113 | 74 | 46 | 67 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 593 | 1 |

| Colombia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| France | 10 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 28 | 0 | |||||

| Mexico | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 0 | |||||||

| Bahrain | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Luxembourg | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Qatar | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Total | 218 | 237 | 266 | 187 | 128 | 147 | 80 | 38 | 19 | 31 | 41 | 17 | 11 | 1 | 1,421 | |

| C. CDS availability by industry and year . | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2001 . | 2002 . | 2003 . | 2004 . | 2005 . | 2006 . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011 . | 2012 . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | Average . |

| Agriculture | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| Food Products | 11 | 14 | 20 | 24 | 31 | 33 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 18 | 30 |

| Candy & Soda | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Beer & Liquor | 6 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 6 | 14 |

| Tobacco Products | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 8 |

| Recreation | 4 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 10 |

| Entertainment | 5 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 19 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 7 | 14 |

| Printing and Publishing | 9 | 10 | 13 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 6 | 16 |

| Consumer Goods | 15 | 17 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 9 | 23 |

| Apparel | 5 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 9 |

| Healthcare | 3 | 4 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 2 | 12 |

| Medical Equipment | 4 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 7 | 12 |

| Pharmaceutical Products | 10 | 20 | 26 | 38 | 41 | 45 | 51 | 49 | 43 | 42 | 41 | 40 | 39 | 41 | 12 | 36 |

| Chemicals | 19 | 30 | 40 | 54 | 65 | 64 | 64 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 67 | 67 | 68 | 68 | 25 | 56 |

| Rubber and Plastic Products | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Textiles | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| Construction Materials | 7 | 15 | 19 | 27 | 31 | 30 | 34 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 35 | 13 | 29 |

| Construction | 3 | 11 | 17 | 27 | 33 | 42 | 56 | 62 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 68 | 66 | 67 | 31 | 45 |

| Steel Works Etc | 10 | 13 | 18 | 29 | 35 | 35 | 38 | 44 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 25 | 34 |

| Fabricated Products | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Machinery | 10 | 25 | 35 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 55 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 57 | 33 | 47 |

| Electrical Equipment | 3 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 10 | 16 |

| Automobiles and Trucks | 25 | 34 | 39 | 47 | 56 | 60 | 63 | 64 | 63 | 60 | 61 | 63 | 63 | 60 | 22 | 52 |

| Aircraft | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 1 | 10 |

| Shipbuilding, Railroad Equipment | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Defense | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Precious Metals | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Non-Metallic and Industrial Metal Mining | 3 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 6 | 15 |

| Coal | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | |||

| Petroleum and Natural Gas | 27 | 45 | 55 | 63 | 66 | 76 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 77 | 82 | 80 | 83 | 9 | 66 |

| Utilities | 43 | 71 | 87 | 117 | 137 | 148 | 150 | 153 | 150 | 146 | 147 | 141 | 143 | 139 | 32 | 120 |

| Communication | 46 | 55 | 74 | 79 | 92 | 97 | 101 | 104 | 107 | 103 | 102 | 106 | 105 | 102 | 24 | 86 |

| Personal Services | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 6 |

| Business Services | 13 | 21 | 35 | 52 | 63 | 68 | 73 | 73 | 72 | 75 | 75 | 80 | 77 | 78 | 27 | 59 |

| Computers | 9 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 23 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 11 | 22 |

| Electronic Equipment | 15 | 22 | 38 | 57 | 65 | 71 | 69 | 71 | 71 | 68 | 67 | 62 | 61 | 60 | 22 | 55 |

| Measuring and Control Equipment | 4 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 8 | 12 |

| Business Supplies | 11 | 12 | 14 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 32 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 31 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 11 | 25 |

| Shipping Containers | 4 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 2 | 11 |

| Transportation | 21 | 35 | 52 | 75 | 79 | 85 | 87 | 87 | 89 | 86 | 88 | 91 | 94 | 93 | 44 | 74 |

| Wholesale | 8 | 14 | 19 | 22 | 33 | 36 | 37 | 40 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 38 | 36 | 36 | 21 | 30 |

| Retail | 37 | 44 | 53 | 69 | 74 | 81 | 92 | 94 | 91 | 90 | 90 | 87 | 85 | 85 | 34 | 74 |

| Restaurants, Hotels, Motels | 10 | 15 | 20 | 26 | 26 | 30 | 29 | 31 | 33 | 33 | 32 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 13 | 26 |

| Other Industries | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 6 |

| Total | 427 | 631 | 849 | 1,117 | 1,271 | 1,365 | 1,449 | 1,483 | 1,485 | 1,462 | 1,455 | 1,467 | 1,450 | 1,445 | 519 | 1,195 |

| C. CDS availability by industry and year . | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2001 . | 2002 . | 2003 . | 2004 . | 2005 . | 2006 . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011 . | 2012 . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | Average . |

| Agriculture | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| Food Products | 11 | 14 | 20 | 24 | 31 | 33 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 18 | 30 |

| Candy & Soda | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Beer & Liquor | 6 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 6 | 14 |

| Tobacco Products | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 8 |

| Recreation | 4 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 10 |

| Entertainment | 5 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 19 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 7 | 14 |

| Printing and Publishing | 9 | 10 | 13 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 6 | 16 |

| Consumer Goods | 15 | 17 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 9 | 23 |

| Apparel | 5 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 9 |

| Healthcare | 3 | 4 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 2 | 12 |

| Medical Equipment | 4 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 7 | 12 |

| Pharmaceutical Products | 10 | 20 | 26 | 38 | 41 | 45 | 51 | 49 | 43 | 42 | 41 | 40 | 39 | 41 | 12 | 36 |

| Chemicals | 19 | 30 | 40 | 54 | 65 | 64 | 64 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 67 | 67 | 68 | 68 | 25 | 56 |

| Rubber and Plastic Products | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Textiles | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| Construction Materials | 7 | 15 | 19 | 27 | 31 | 30 | 34 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 35 | 13 | 29 |

| Construction | 3 | 11 | 17 | 27 | 33 | 42 | 56 | 62 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 68 | 66 | 67 | 31 | 45 |

| Steel Works Etc | 10 | 13 | 18 | 29 | 35 | 35 | 38 | 44 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 25 | 34 |

| Fabricated Products | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Machinery | 10 | 25 | 35 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 55 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 57 | 33 | 47 |

| Electrical Equipment | 3 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 10 | 16 |

| Automobiles and Trucks | 25 | 34 | 39 | 47 | 56 | 60 | 63 | 64 | 63 | 60 | 61 | 63 | 63 | 60 | 22 | 52 |

| Aircraft | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 1 | 10 |

| Shipbuilding, Railroad Equipment | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Defense | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Precious Metals | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Non-Metallic and Industrial Metal Mining | 3 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 6 | 15 |

| Coal | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | |||

| Petroleum and Natural Gas | 27 | 45 | 55 | 63 | 66 | 76 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 77 | 82 | 80 | 83 | 9 | 66 |

| Utilities | 43 | 71 | 87 | 117 | 137 | 148 | 150 | 153 | 150 | 146 | 147 | 141 | 143 | 139 | 32 | 120 |

| Communication | 46 | 55 | 74 | 79 | 92 | 97 | 101 | 104 | 107 | 103 | 102 | 106 | 105 | 102 | 24 | 86 |

| Personal Services | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 6 |

| Business Services | 13 | 21 | 35 | 52 | 63 | 68 | 73 | 73 | 72 | 75 | 75 | 80 | 77 | 78 | 27 | 59 |

| Computers | 9 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 23 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 11 | 22 |

| Electronic Equipment | 15 | 22 | 38 | 57 | 65 | 71 | 69 | 71 | 71 | 68 | 67 | 62 | 61 | 60 | 22 | 55 |

| Measuring and Control Equipment | 4 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 8 | 12 |

| Business Supplies | 11 | 12 | 14 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 32 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 31 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 11 | 25 |

| Shipping Containers | 4 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 2 | 11 |

| Transportation | 21 | 35 | 52 | 75 | 79 | 85 | 87 | 87 | 89 | 86 | 88 | 91 | 94 | 93 | 44 | 74 |

| Wholesale | 8 | 14 | 19 | 22 | 33 | 36 | 37 | 40 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 38 | 36 | 36 | 21 | 30 |

| Retail | 37 | 44 | 53 | 69 | 74 | 81 | 92 | 94 | 91 | 90 | 90 | 87 | 85 | 85 | 34 | 74 |

| Restaurants, Hotels, Motels | 10 | 15 | 20 | 26 | 26 | 30 | 29 | 31 | 33 | 33 | 32 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 13 | 26 |

| Other Industries | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 6 |

| Total | 427 | 631 | 849 | 1,117 | 1,271 | 1,365 | 1,449 | 1,483 | 1,485 | 1,462 | 1,455 | 1,467 | 1,450 | 1,445 | 519 | 1,195 |

The table shows the number of CDS reference entities by year across countries (panel A) and industries (panel C) and the number of CDS introductions by year across countries (panel B). Countries in panels A and B are sorted by the creditor rights index as reported in the last column of panel A. The sample consists of an unbalanced panel of more than 56,000 nonfinancial firms across 51 countries over the period 2001–2015. Market data are from Datastream; accounting data are from WorldScope; and CDS data are from Markit.

| A. CDS availability by country and year . | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2001 . | 2002 . | 2003 . | 2004 . | 2005 . | 2006 . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011 . | 2012 . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | Average . | Creditor Rights . |

| Hong Kong | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 21 | 30 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 39 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 7 | 26 | 4 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| United Kingdom | 31 | 48 | 62 | 65 | 66 | 69 | 64 | 59 | 58 | 58 | 60 | 60 | 55 | 58 | 32 | 56 | 4 |

| Australia | 9 | 17 | 20 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 21 | 3 |

| Austria | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Czech Republic | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Denmark | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Germany | 17 | 20 | 29 | 36 | 37 | 40 | 41 | 43 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 10 | 36 | 3 |

| Israel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Korea, Republic Of | 4 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 18 | 3 | |

| Malaysia | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Netherlands | 8 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 3 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Singapore | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| South Africa | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |||

| Belgium | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Chile | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | |||

| Egypt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| India | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 32 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 51 | 52 | 43 | 33 | 2 | |

| Indonesia | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 2 | |||||

| Italy | 7 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 19 | 22 | 23 | 17 | 2 | |

| Japan | 27 | 61 | 121 | 202 | 247 | 267 | 285 | 289 | 288 | 286 | 282 | 278 | 280 | 276 | 255 | 230 | 2 |

| Kazakhstan | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Norway | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | |

| Romania | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Russian Federation | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |||||

| Spain | 5 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 2 | |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Taiwan | 6 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 23 | 2 | |||

| Thailand | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 2 | ||

| Turkey | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Argentina | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Brazil | 2 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 1 | ||||

| Canada | 9 | 18 | 25 | 37 | 42 | 42 | 39 | 39 | 37 | 37 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 3 | 31 | 1 |

| Finland | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | |

| Greece | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Hungary | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Ireland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Philippines | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Poland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Portugal | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Sweden | 7 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 1 |

| Switzerland | 4 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 1 | |

| United States | 251 | 347 | 447 | 566 | 615 | 641 | 670 | 661 | 655 | 634 | 626 | 623 | 609 | 599 | 130 | 538 | 1 |

| Colombia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||

| France | 28 | 36 | 42 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 45 | 43 | 42 | 43 | 45 | 47 | 48 | 4 | 40 | 0 |

| Mexico | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 0 | |||

| Bahrain | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Luxembourg | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Qatar | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Total | 427 | 631 | 849 | 1,117 | 1,271 | 1,365 | 1,449 | 1,483 | 1,485 | 1,462 | 1,455 | 1,467 | 1,450 | 1,445 | 519 | 1,225 | |

| A. CDS availability by country and year . | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2001 . | 2002 . | 2003 . | 2004 . | 2005 . | 2006 . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011 . | 2012 . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | Average . | Creditor Rights . |

| Hong Kong | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 21 | 30 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 39 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 7 | 26 | 4 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| United Kingdom | 31 | 48 | 62 | 65 | 66 | 69 | 64 | 59 | 58 | 58 | 60 | 60 | 55 | 58 | 32 | 56 | 4 |

| Australia | 9 | 17 | 20 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 21 | 3 |

| Austria | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Czech Republic | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Denmark | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Germany | 17 | 20 | 29 | 36 | 37 | 40 | 41 | 43 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 10 | 36 | 3 |

| Israel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Korea, Republic Of | 4 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 18 | 3 | |

| Malaysia | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Netherlands | 8 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 3 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Singapore | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| South Africa | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |||

| Belgium | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Chile | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | |||

| Egypt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| India | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 32 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 51 | 52 | 43 | 33 | 2 | |

| Indonesia | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 2 | |||||

| Italy | 7 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 19 | 22 | 23 | 17 | 2 | |

| Japan | 27 | 61 | 121 | 202 | 247 | 267 | 285 | 289 | 288 | 286 | 282 | 278 | 280 | 276 | 255 | 230 | 2 |

| Kazakhstan | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Norway | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | |

| Romania | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Russian Federation | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |||||

| Spain | 5 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 2 | |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||