-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ami Schattner, Ina Dubin, Yair Glick, Yossi Cohen, A ‘benign’ malignant disease—splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 116, Issue 6, June 2023, Pages 445–446, https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcad007

Close - Share Icon Share

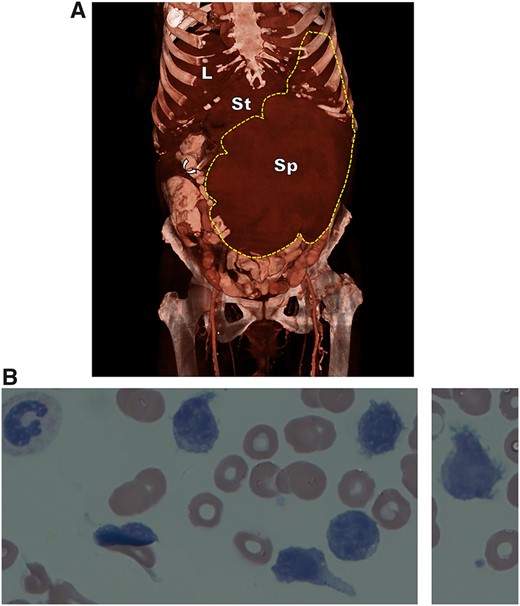

An active 84-year-old woman presented with urinary tract infection, but on admission an abdominal mass was felt. Imaging revealed massive splenomegaly (homogeneous) occupying most of the abdominal cavity (Figure 1A). No lymphadenopathy or hepatic pathology was found and chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was ruled out. Haemoglobin was 9 g/dl (mean corpuscular volume 90), white blood cells 9.6 × 109/l (neutrophils 2.0, lymphocytes 6.3 and large unstained cells [LUC] 0.9), platelets 72 × 109/l and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 359 IU/l (N < 214). Blood smear demonstrated abundant atypical lymphocytes with villous projections (Figure 1B). Her old charts revealed an outpatient haematology work-up 5 years prior for asymptomatic splenomegaly of 17 cm associated with a similar blood count without LUC, C-reactive protein 5.0 (N ≤ 0.5), Immunoglobulin M (IgM) 459 mg/dl (N < 293), IgM kappa monoclonal 0.6 g/dl, free Kappa light chains 219.8 mg/l with kappa/lambda ratio 8.96 (N 0.26–1.65) and normal LDH. Bone marrow biopsy was consistent with splenic low-grade marginal zone lymphoma (ki-67 < 2%). Asked directly, she reported early satiety and weight loss but refused treatment then, and now.

(A) 3D reformation of contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen and pelvis, showing a gigantic spleen (SPL; borders demarcated by broken line) dwarfing the liver (L), compressing the stomach (G) and left kidney and displacing the liver and many bowel loops. The curved arrow points to the edge of a nasogastric tube. (B) Peripheral blood smear (Giemsa, X100) showing abnormal lymphoid cells with characteristic surface villous projections and a clumped chromatin.

The differential diagnosis of splenomegaly is wide, including myriad infectious, autoimmune, malignant, haemolytic, metabolic and portal hypertension causes.1 In contrast, ‘massive splenomegaly’ that crosses the midline or extends into the pelvis is associated almost exclusively with haematological malignancies or parasitic infestations, less often with portal hypertension or Gaucher disease (based on PubMed search 1982–2022, n = 287 abstracted publications in English).

Our patient steadfastly declined treatment affording a unique insight into the natural history of a slowly growing lymphoid neoplasm. Her rare splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes is an indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma mainly involving the spleen and bone marrow. It is histologically indistinguishable from splenic marginal-zone lymphoma and villous lymphocytes have immunologic and immunophenotypical characters of marginal zone lymphocytes.2 Clinically, moderate lymphocytosis, villous lymphocytes on peripheral blood smear, marked splenomegaly, no lymphadenopathy, serum monoclonal band and a slow benign course are typical. In some patients, autoimmune haematological syndromes are associated. An intriguing association with HCV was reported and antiviral treatment led to the regression of the lymphoma.3 Without treatment, and with few symptoms (more recently, pressure by the spleen caused early satiety) our patient’s spleen enlarged to extreme proportions. Calculated from the imaging studies, it weighed approximately 2700 g, 20 times more than the mean 135 g found in normal women.4 Had she consented, treatment with rituximab/bendamustine could be highly effective.

Author contributions

Yossi Cohen (Investigation [supporting], Validation [supporting]).

Patient informed consent

signed.

Conflict of interest: None declared.