-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anyah Prasad, Natalie Shellito, Edward Alan Miller, Jeffrey A Burr, Association of Chronic Diseases and Functional Limitations with Subjective Age: The Mediating Role of Sense of Control, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Volume 78, Issue 1, January 2023, Pages 10–19, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbac121

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study examined the relationships between chronic diseases, functional limitations, sense of control, and subjective age. Older adults may evaluate their subjective age by reference to their younger healthier selves and thus health and functional status are likely to be determinants of subjective age. Although sense of control is also a potential predictor of subjective age, stress-inducing factors associated with disease and functional limitations may reduce older adults’ sense of control, making them feel older.

Using the 2010 and 2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study, structural equation modeling was performed on a sample of 6,329 respondents older than 50 years to determine whether sense of control mediated the relationship between chronic diseases, limitations in instrumental/basic activities of daily living (ADLs, IADLs), and subjective age.

Chronic diseases and limitations in ADLs had a positive, direct association with subjective age (β = 0.037, p = .005; β = 0.068, p = .001, respectively). In addition, chronic diseases and limitations in ADLs and IADLs were positively, indirectly associated with subjective age via a diminished sense of control (β = 0.006, p = .000; β = 0.007, p = .003; β = 0.019, p = .000, respectively).

As predicted by the Deterioration model, the findings showed that chronic diseases and functional impairment are associated with older adults feeling older by challenging the psychological resource of sense of control. Appropriate interventions for dealing with health challenges and preserving sense of control may help prevent the adverse downstream effects of older subjective age.

Subjective age may be a psychological marker of aging, indicating who may be at a higher risk for poor health outcomes. Subjective age is conceptualized as individuals’ cognitive evaluation of how old they feel, which is distinct from their chronological age (Hubley & Russell, 2009). Older adults who report younger subjective age tend to be healthier and live longer (Westerhof et al., 2014). Given the importance of subjective age as a risk factor for subsequent health outcomes, understanding what factors are associated with subjective age and the underlying mechanisms that provide a link for this association may help enhance healthy aging. While subjective age may influence future morbidity and mortality, the scientific literature suggests that disease and functional status, in turn, shape individuals’ felt age (Choi et al., 2014; Spuling et al., 2013). As an important psychological resource contributing to older adults’ ability to cope with health challenges (Rodin, 1986), sense of control may act as a mediator between chronic diseases, functional limitations, and subjective age.

Past studies have used either chronic diseases or functional limitations when examining the role of sense of control in the pathway between health and subjective age (Schafer & Shippee, 2010; Tovel et al., 2019). However, because the risk of comorbidity and dependency increases in later years of life, it is important to consider both of these health statuses together. This study thus aims to build on the existing literature by examining chronic diseases and functional limitations in the same model. We further differentiate between two types of functional limitations; activities of daily living (ADLs), conceptualized as difficulty taking care of oneself and maintaining personal hygiene; and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), conceptualized as difficulty living in the community independently (Spector & Fleishman, 1998). These three factors allow us to parse out the contribution of each health status in determining middle-aged and older adults’ subjective age and whether sense of control is a mechanism linking health and subjective age.

Health and Subjective Age

Despite the potentially reciprocal relationship, the antecedent role of health for subjective age has received much less attention than the negative health consequences of reporting older subjective age (Prasad et al., 2022; Spuling et al., 2013; Westerhof et al., 2014). A few studies, however, showed that people with better self-rated health, and those who were more satisfied with their health, felt relatively younger than those who reported poorer subjective health (Barrett, 2003; Bergland et al., 2014; Hubley & Russell, 2009). Similarly, better grip strength and peak expiratory flow rates were also related to younger subjective age (Stephan et al., 2015). On the other hand, chronic diseases and functional limitations were associated with older subjective age (Barrett, 2005; Choi et al., 2014; Prasad et al., 2022).

Most studies demonstrating an association between health and subjective age are based on cross- sectional research designs (Barrett, 2005; Choi et al., 2014). Longitudinal study designs that examined the effect of baseline chronic diseases and functional limitations on subjective age measured a few years later show mixed evidence, with some demonstrating a statistically significant effect (Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al., 2008) and others showing no effect (Spuling et al., 2013). A probable explanation for the equivocal findings is that the influence of chronic diseases and functional limitations may weaken over time as people adjust to and cope with such challenges. Using change models, Prasad and colleagues (2022) demonstrated that the effect size of incident chronic diseases on subjective age was stronger than that of baseline chronic diseases. They suggested that a similar dynamic may be at play with functional limitations, as well.

The relationship between health and subjective age is likely, indirect, at least partly, with health influencing subjective age through other intermediate factors. For example, factors such as social comparison, affect, and extraversion are shown to mediate the relationship between health and subjective age (Bellingtier et al., 2017; Hughes & Lachman, 2018; Schafer & Shippee, 2010). Another potential but underexplored construct that may help us understand the association between chronic disease, functional status, and subjective age is sense of control, a psychological resource that provides individuals with the ability to cope with losses in health (De Ridder et al., 2008).

Sense of Control as a Mediator Between Health and Subjective Age

Sense of control, also referred to as “mastery” or “self-efficacy,” is conceptualized as individuals’ intuitive expectation and confidence that they have the power to control their life and environment (Skaff, 2007; Zarit et al., 2003). Sense of control is a subconscious psychological asset that improves people’s ability to cope with life’s challenges, helping them successfully overcome hurdles. Sense of control may help people cope with the health challenges presented in later life, and therefore, continue to feel closer to their younger years of peak health and functional ability. This supposition is supported by existing research showing that individuals with a higher sense of control reported younger subjective age (Barrett, 2003; Barrett, 2005; Bergland et al., 2014; Bowling et al., 2005; Teuscher, 2009). The association seems to be stronger among older adults compared to younger adults (Bellingtier & Neupert, 2020; Infurna et al., 2010). Likely, as middle-aged and older adults grow more distant from their younger healthier years, sense of control may assume a heightened role in maintaining a younger age identity.

Maintaining health is essential for meeting life’s demands. Chronic diseases and functional limitations that become more common in later life may make older adults feel constrained in their ability to cope; therefore, they may perceive less control over their lives (Jang et al., 2003; Jang et al., 2009) and in turn feel less like their younger selves. However, few studies have examined the mediating role of sense of control between chronic diseases, functional impairments, and subjective age. Schafer and Shippee (2010) demonstrated that chronic diseases were related to an increase in middle-aged and older Americans’ subjective age via depletion of their sense of control. However, Tovel et al. (2019) found no association between functional limitations and attitudes towards aging in a sample of older Israeli adults. Another analysis, using a daily diary method with a small convenience sample of predominantly older females, also found no support for the mediation role of sense of control between stressors due to health deterioration and subjective age (Bellingtier et al., 2017). Overall, evidence for the mediation role of sense of control on the relationship between chronic diseases, functional limitations, and subjective age is sparse and inconclusive.

Theoretical Perspectives

In theorizing the concept of subjective age, Montepare (2009) distinguishes two broad categories of factors shaping individuals’ felt age, including distal and proximal factors. The distal factor is contextualized within a life-span framework in which human beings perceive young adulthood as the peak of biological and functional development and refer their current age to this prime developmental stage to optimize life’s potential. That is why people often report feeling older than their chronological age in the early part of the life course but report feeling younger in their later years, with the crossover happening at about age 25 (Galambos et al., 2005). The influence of this distal framework on felt age may be modified by proximal factors, such as poor health and functional limitations. Because the risk of poor health increases with advancing age, losses in health and reductions in functional independence may remind middle-aged and older adults of their aging bodies and make them feel older than their chronological age (Kotter-Grühn et al., 2016). In sum, subjective age may play an adaptive role by driving necessary behavioral changes, such as seeking medical help or reevaluating goals, to optimize quality of life in the new reality of their aging bodies.

According to the Deterioration Model proposed by Ensel and Lin (1991), stressors, such as adverse health events, reduce peoples’ psychological resources, including sense of control, a key component of psychological functioning and overall well-being. This model suggests that experiences with chronic diseases and functional limitations associated with the aging process may lower older adults’ sense of control and their ability to refer to a younger age identity. There is some indirect and direct evidence for the mediational role of sense of control as derived from the Deterioration Model. For example, experiencing chronic diseases and functional limitations were related to a diminished sense of control (Jang et al., 2003; Jang et al., 2009). Schafer and Shippee (2010) demonstrated that chronic diseases are associated with people feeling older during the 10-year follow-up period and that this association was mediated by their sense of control.

Current Study

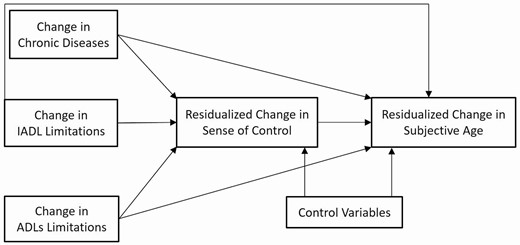

The conceptual model for this study is based on the life-span framework of subjective age, the Deterioration Model, and findings from the empirical literature (see Figure 1). Furthermore, past mediation studies used recent health events to examine the effect on subjective age via sense of control (Bellingtier et al., 2017; Schafer & Shippee, 2010). We argue that recent negative changes in health and loss of independence may be more consequential to subjective age than health observed at a single point in time. In the conceptual model guiding this study, we posit that change in the number of chronic diseases and change in the number of limitations in ADLs and IADLs are positively related to subjective age, all else being equal (hypothesis 1). In addition, we posit that sense of control mediates the relationship between changes in the number of chronic diseases, ADL and IADL limitations and subjective age (hypothesis 2). We include relevant control variables in the model.

Conceptual framework for the mediational role of sense of control between chronic diseases, functional limitations, and subjective age.

Method

Data Source

This study employed data from the 2010 and 2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a probability-based biennial panel survey of Americans aged 51 years and older (Servais, 2010). Beginning in 2006, a random half of the core sample was interviewed face-to-face and was also given a self-administered psychosocial Leave Behind Questionnaire (LBQ). In 2008, the remaining respondents were given the LBQ. Thus, every four years one half of the respondents were given the LBQ. Respondents were asked to report their subjective age in the LBQ (Smith et al., 2017). Those who reported their subjective age in 2010 were not asked their subjective age again until 2014. Although the HRS data set was the primary source for our analyses, those variables that required cross-wave evaluation for consistency were obtained from HRS data files provided by the RAND Corporation (Chien et al., 2015).

Study Sample

Of the random half of the core respondents interviewed face-to-face in 2010, 8,263 returned the LBQ. Respondents younger than 51 years old (n = 415), who were spouses of the study respondents, were not considered in the study sample because they were not part of the sampling strategy for the HRS. Because proxy respondents cannot report subjective age, 239 proxy respondents from 2010 and 137 from 2014 were excluded from the study sample. Those lost to attrition between the two waves (n = 1,143) were also excluded; these exclusions resulted in a final study sample of 6,329 (76.6%) respondents. Compared with respondents in the final study sample, the excluded respondents (n = 1,519) were older (72.89 vs. 66.29, p <.001), felt proportionately less young (−0.12 vs. −0.15, p < .001), were less educated (12.36 vs. 12.99, p < .001), had more chronic diseases (2.65 vs. 1.99, p <.001), ADL limitations (0.68 vs. 0.28, p < .001), and IADL limitations (0.52 vs. 0.17, p < .001), and reported lower levels of sense of control (4.55 vs. 4.82, p < .001).

Measures

Subjective age

Respondents reported their subjective age with the following question: “Many people feel older or younger than they actually are. What age do you feel?” To account for extreme outliers and to reduce bias, 19 respondents who reported their subjective age at less than 12 years old were bottom-coded to age 12, the next youngest reported value in the sample distribution. Similarly, 37 respondents who reported feeling more than 123 years old, were top-coded to 112 years old, the next highest reported subjective age in the study sample. We then calculated the proportional discrepancy score by subtracting chronological age from subjective age and dividing the difference score by chronological age. As a part of sensitivity analysis, we also calculated proportional discrepancy score based on raw subjective age values and then winsorized extreme low values to three times the interquartile range below the first quartile (18 cases) and extreme high values to three times the interquartile range above the third quartile (43 cases). The positive and negative values indicated that the respondents feel proportionately older and younger than they are, respectively, and zero indicated that they felt as old as their chronological age. Subjective age, hereafter, proportional subjective age, reported in 2014 was used as the dependent variable (range = −0.87 to 1.11); we controlled for subjective age in 2010 (baseline).

Change in chronic diseases

Number of chronic diseases was measured as the sum of physician-diagnosed chronic diseases that were newly reported by the respondents between 2010 and 2014. The list of diseases included hypertension, diabetes, cancer, lung disease, heart conditions, stroke, psychological problems, and arthritis (range = 0–8; Bugliari et al., 2019). The number of chronic diseases reported in 2010 or earlier was specified as a baseline control variable.

Change in functional limitations

Functional limitations were measured as change in the number of limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) between 2010 and 2014 (Bugliari et al., 2019). Limitations in ADLs are based on a six-item measure capturing difficulty in bathing, toileting, dressing, eating, getting in/out of bed, and walking across a room. Limitations in IADLs is based on a five-item measure capturing difficulty using a phone, managing money, taking medications, shopping for groceries, and preparing hot meals. In addition, the number of limitations with ADLs and IADLs at baseline (2010) were used as control variables.

Sense of control

As used in previous studies (Hong et al., 2021), sense of control was measured by averaging five mastery and five constraint items, scored on a Likert scale (range = 1–6). The mastery items included statements like “I can do just about anything I really set my mind to.” Whereas the constraint items included statements as “I often feel helpless in dealing with the problems of life.” The constraint items were first reverse coded and the scale was set to missing if more than six items were missing. Cronbach’s α scores were .87 in 2010 and .88 in 2014, respectively (Clarke et al., 2008). Sense of control reported in 2014 was used as the mediating variable, while controlling for baseline sense of control in 2010.

Control variables

We controlled for sociodemographic characteristics in our models, including chronological age, gender, race–ethnic status, education, and household wealth, as these characteristics may be associated with subjective age and sense of control (Henderson et al., 1995; Lachman & Weaver, 1998; Ross & Mirowsky, 2002). Chronological age was measured in years (range = 51–101); gender was coded as a binary variable (1 = female); race–ethnic status was coded as a set of four dichotomous variables, including non-Hispanic White (reference group), non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other race groups, and Hispanic any race; education was measured as number of years of schooling (range = 0–17); and household wealth, transformed with an inverse hyperbolic sine function to correct for skewness (Friedline et al., 2015).

Widowhood, retirement, and grandparent statuses were introduced as binary variables (1 = yes) because, as markers of age transitions, these characteristics may be associated with subjective age (Mathur & Moschis, 2005). Finally, we controlled for self-rated health and cognitive status, along with vision and hearing loss, because these may also be associated with subjective age (Choi et al., 2014; Knoll et al., 2004). Self-rated health was measured on a 5-point scale (1 = poor to 5 = excellent), and self-reported vision and hearing were measured as binary variables (1 = poor, 0 = fair or better). Respondents’ cognition was accessed with the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status measure (TICS, range = 0–35; Ofstedal et al., 2005).

Analytic Strategy

First, we estimated descriptive statistics for all study variables and examined the bivariate associations (Pearson correlations or ANOVA) between subjective age in 2014 and each of the variables in the model. Second, we provided a correlation matrix for subjective age and the key theoretical variables. Third, structural equation modeling was used to estimate the direct effect of incident chronic health conditions and incident functional limitations on subjective age, along with the mediation role of sense of control for these relationships. Subjective age in 2014 and sense of control in 2014 were specified as residualized changes between 2010 and 2014 by including baseline (2010) variables in the model. Data preparation, descriptive statistics, and bivariate analyses were performed using SPSS Version 27. The mediation path analyses were performed using Mplus version 8.1.

One of the assumptions of maximum likelihood methods, the default estimation method used to perform mediation analysis in Mplus, is that the endogenous variables are normally distributed. Although subjective age met this assumption, sense of control was skewed. Therefore, we used the maximum likelihood robust estimator to generate unbiased standard errors and to ensure that the P-values were robust in the context of non-normality. Since this is a change model assessed between two time points, we excluded respondents lost to attrition and those who self-responded at baseline but for whom proxy respondents were used at follow-up. Furthermore, we employed a full information maximum likelihood method to account for other missing data. We reported standardized coefficients to estimate direct and indirect effect sizes. Model fit was assessed based on whether the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was below 0.05 and whether comparative fit index (CFI) was more than 0.95. We engaged in sensitivity analyses by re-estimating the above model with proportional subjective age score winsorized based on interquartile range, including respondents lost to attrition by 2014, and using cross-sectional data only from 2010.

Results

The descriptive statistics for the study sample and bivariate analysis results are presented in Table 1. Respondents’ mean subjective age (original values) in 2010 was 56.0 years compared to a mean chronological age of 66.3 years. During the four-year follow-up period, average subjective age (original values) increased by 3.5 years. Proportional subjective age changed from −0.153 in 2010 to −0.148 in 2014. On average, respondents reported two chronic diseases at baseline and less than one new chronic disease between 2010 and 2014. Respondents reported, on average, less than one ADL and IADL limitation at baseline and even fewer new limitations during the follow-up period. Respondents had mean scores of 4.82 on the sense of control measure at baseline, with a small decrease to 4.79 at follow-up. Respondents were predominately female (59.5%) and non-Hispanic White (71.6%). Median household wealth was approximately $181,500. Respondents averaged 13 years of education. Nearly one sixth of respondents were widowed (16.5%), approximately half of the respondents were retired (46.3%), and over three fourths of the respondents were grandparents (75.5%). Respondents averaged 3.28 on the self-reported health measure (range = 1–5); 4.6% reported poor vision, 4.4% reported poor hearing and the mean score on the TICS cognition measure was 22.41 (range = 0–35).

Descriptive Statistics for the Study Sample and Bivariate Associations With Subjective Age

| . | Mean/% . | N . | SD . | Range . | Bivariate associations with proportional subjective age in 2014 . | N . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | ||||||

| Proportional subjective age—2014 | −0.148 | 5,491 | 0.18 | −0.87 to 1.11 | ||

| Subjective age—raw score | 59.54 | 14.76 | 12 to 112 | |||

| Predictor variables | ||||||

| Change in number of chronic diseases | 0.39 | 6,329 | 0.65 | 0 to 4 | 0.06*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Change in number of ADL limitations | 0.10 | 6,319 | 0.84 | −5 to 6 | 0.1*** (r) | 5,483 |

| Change in number of IADL limitations | 0.09 | 6,327 | 0.67 | −5 to 5 | 0.03* (r) | 5,491 |

| Mediator variable | ||||||

| Sense of control—2014 | 4.79 | 5,712 | 0.96 | 1 to 6 | −0.26*** (r) | 5,467 |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Proportional subjective age—2010 | −0.153 | 6,021 | 0.18 | −0.86 to 1.04 | 0.48*** (r) | 5,293 |

| Subjective age—raw score | 55.98 | 13.88 | 12 to 112 | |||

| Number of chronic diseases in 2010 | 1.99 | 6,329 | 1.42 | 0 to 8 | 0.16*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Number ADL limitations in 2010 | 0.28 | 6,327 | 0.83 | 0 to 6 | 0.1*** (r) | 5,490 |

| Number IADL limitations in 2010 | 0.17 | 6,328 | 0.6 | 0 to 5 | 0.13*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Sense of control—2010 | 4.82 | 6,279 | 0.93 | 1 to 6 | −0.18*** (r) | 5,461 |

| Chronological age—2010 | 66.29 | 6,329 | 9.95 | 51 to 101 | 0.02 (r) | 5,491 |

| Gender (female = 1) | 59.5% | 6,329 | 0 to 1 | 5.2* (F) | 5,491 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 6,324 | 1 to 4 | 3.24* (F) | 6,016 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.6% | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 15.9% | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Other | 2.7% | |||||

| Hispanic | 9.7% | |||||

| Wealth (inverse hyperbolic sine) | 10.69 | 6,329 | −14.34 to 17.83 | −0.03* (r) | 5,491 | |

| Number years of education | 13 | 6,305 | 2.94 | 0 to 17 | −0.08*** (r) | 5,469 |

| Marital status (widowed = 1) | 16.5% | 6,324 | 0 to 1 | 0.18 (F) | 5,488 | |

| Employment status (retired = 1) | 46.3% | 6,325 | 0 to 1 | 2.54 (F) | 5,489 | |

| Grandparent status (grandparent = 1) | 75.5% | 6,250 | 0 to 1 | 5.29* (F) | 5,429 | |

| Self-reported health | 3.28 | 6,327 | 1.04 | 1 to 5 | −0.22*** (r) | 5,490 |

| Cognition | 22.41 | 4,645 | 4.4 | 3 to 34 | −0.05** (r) | 3,984 |

| Self-reported vision | 4.6% | 6,320 | 0 to 1 | 29.29*** (F) | 5,484 | |

| Self-reported hearing | 4.4% | 6,327 | 0 to 1 | 2.81 (F) | 5,489 |

| . | Mean/% . | N . | SD . | Range . | Bivariate associations with proportional subjective age in 2014 . | N . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | ||||||

| Proportional subjective age—2014 | −0.148 | 5,491 | 0.18 | −0.87 to 1.11 | ||

| Subjective age—raw score | 59.54 | 14.76 | 12 to 112 | |||

| Predictor variables | ||||||

| Change in number of chronic diseases | 0.39 | 6,329 | 0.65 | 0 to 4 | 0.06*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Change in number of ADL limitations | 0.10 | 6,319 | 0.84 | −5 to 6 | 0.1*** (r) | 5,483 |

| Change in number of IADL limitations | 0.09 | 6,327 | 0.67 | −5 to 5 | 0.03* (r) | 5,491 |

| Mediator variable | ||||||

| Sense of control—2014 | 4.79 | 5,712 | 0.96 | 1 to 6 | −0.26*** (r) | 5,467 |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Proportional subjective age—2010 | −0.153 | 6,021 | 0.18 | −0.86 to 1.04 | 0.48*** (r) | 5,293 |

| Subjective age—raw score | 55.98 | 13.88 | 12 to 112 | |||

| Number of chronic diseases in 2010 | 1.99 | 6,329 | 1.42 | 0 to 8 | 0.16*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Number ADL limitations in 2010 | 0.28 | 6,327 | 0.83 | 0 to 6 | 0.1*** (r) | 5,490 |

| Number IADL limitations in 2010 | 0.17 | 6,328 | 0.6 | 0 to 5 | 0.13*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Sense of control—2010 | 4.82 | 6,279 | 0.93 | 1 to 6 | −0.18*** (r) | 5,461 |

| Chronological age—2010 | 66.29 | 6,329 | 9.95 | 51 to 101 | 0.02 (r) | 5,491 |

| Gender (female = 1) | 59.5% | 6,329 | 0 to 1 | 5.2* (F) | 5,491 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 6,324 | 1 to 4 | 3.24* (F) | 6,016 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.6% | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 15.9% | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Other | 2.7% | |||||

| Hispanic | 9.7% | |||||

| Wealth (inverse hyperbolic sine) | 10.69 | 6,329 | −14.34 to 17.83 | −0.03* (r) | 5,491 | |

| Number years of education | 13 | 6,305 | 2.94 | 0 to 17 | −0.08*** (r) | 5,469 |

| Marital status (widowed = 1) | 16.5% | 6,324 | 0 to 1 | 0.18 (F) | 5,488 | |

| Employment status (retired = 1) | 46.3% | 6,325 | 0 to 1 | 2.54 (F) | 5,489 | |

| Grandparent status (grandparent = 1) | 75.5% | 6,250 | 0 to 1 | 5.29* (F) | 5,429 | |

| Self-reported health | 3.28 | 6,327 | 1.04 | 1 to 5 | −0.22*** (r) | 5,490 |

| Cognition | 22.41 | 4,645 | 4.4 | 3 to 34 | −0.05** (r) | 3,984 |

| Self-reported vision | 4.6% | 6,320 | 0 to 1 | 29.29*** (F) | 5,484 | |

| Self-reported hearing | 4.4% | 6,327 | 0 to 1 | 2.81 (F) | 5,489 |

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. Bivariate associations with the proportional discrepancy measure of subjective age in 2014 were estimated with Pearson correlation for continuous variables and t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for categorical variables.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Descriptive Statistics for the Study Sample and Bivariate Associations With Subjective Age

| . | Mean/% . | N . | SD . | Range . | Bivariate associations with proportional subjective age in 2014 . | N . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | ||||||

| Proportional subjective age—2014 | −0.148 | 5,491 | 0.18 | −0.87 to 1.11 | ||

| Subjective age—raw score | 59.54 | 14.76 | 12 to 112 | |||

| Predictor variables | ||||||

| Change in number of chronic diseases | 0.39 | 6,329 | 0.65 | 0 to 4 | 0.06*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Change in number of ADL limitations | 0.10 | 6,319 | 0.84 | −5 to 6 | 0.1*** (r) | 5,483 |

| Change in number of IADL limitations | 0.09 | 6,327 | 0.67 | −5 to 5 | 0.03* (r) | 5,491 |

| Mediator variable | ||||||

| Sense of control—2014 | 4.79 | 5,712 | 0.96 | 1 to 6 | −0.26*** (r) | 5,467 |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Proportional subjective age—2010 | −0.153 | 6,021 | 0.18 | −0.86 to 1.04 | 0.48*** (r) | 5,293 |

| Subjective age—raw score | 55.98 | 13.88 | 12 to 112 | |||

| Number of chronic diseases in 2010 | 1.99 | 6,329 | 1.42 | 0 to 8 | 0.16*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Number ADL limitations in 2010 | 0.28 | 6,327 | 0.83 | 0 to 6 | 0.1*** (r) | 5,490 |

| Number IADL limitations in 2010 | 0.17 | 6,328 | 0.6 | 0 to 5 | 0.13*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Sense of control—2010 | 4.82 | 6,279 | 0.93 | 1 to 6 | −0.18*** (r) | 5,461 |

| Chronological age—2010 | 66.29 | 6,329 | 9.95 | 51 to 101 | 0.02 (r) | 5,491 |

| Gender (female = 1) | 59.5% | 6,329 | 0 to 1 | 5.2* (F) | 5,491 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 6,324 | 1 to 4 | 3.24* (F) | 6,016 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.6% | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 15.9% | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Other | 2.7% | |||||

| Hispanic | 9.7% | |||||

| Wealth (inverse hyperbolic sine) | 10.69 | 6,329 | −14.34 to 17.83 | −0.03* (r) | 5,491 | |

| Number years of education | 13 | 6,305 | 2.94 | 0 to 17 | −0.08*** (r) | 5,469 |

| Marital status (widowed = 1) | 16.5% | 6,324 | 0 to 1 | 0.18 (F) | 5,488 | |

| Employment status (retired = 1) | 46.3% | 6,325 | 0 to 1 | 2.54 (F) | 5,489 | |

| Grandparent status (grandparent = 1) | 75.5% | 6,250 | 0 to 1 | 5.29* (F) | 5,429 | |

| Self-reported health | 3.28 | 6,327 | 1.04 | 1 to 5 | −0.22*** (r) | 5,490 |

| Cognition | 22.41 | 4,645 | 4.4 | 3 to 34 | −0.05** (r) | 3,984 |

| Self-reported vision | 4.6% | 6,320 | 0 to 1 | 29.29*** (F) | 5,484 | |

| Self-reported hearing | 4.4% | 6,327 | 0 to 1 | 2.81 (F) | 5,489 |

| . | Mean/% . | N . | SD . | Range . | Bivariate associations with proportional subjective age in 2014 . | N . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | ||||||

| Proportional subjective age—2014 | −0.148 | 5,491 | 0.18 | −0.87 to 1.11 | ||

| Subjective age—raw score | 59.54 | 14.76 | 12 to 112 | |||

| Predictor variables | ||||||

| Change in number of chronic diseases | 0.39 | 6,329 | 0.65 | 0 to 4 | 0.06*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Change in number of ADL limitations | 0.10 | 6,319 | 0.84 | −5 to 6 | 0.1*** (r) | 5,483 |

| Change in number of IADL limitations | 0.09 | 6,327 | 0.67 | −5 to 5 | 0.03* (r) | 5,491 |

| Mediator variable | ||||||

| Sense of control—2014 | 4.79 | 5,712 | 0.96 | 1 to 6 | −0.26*** (r) | 5,467 |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Proportional subjective age—2010 | −0.153 | 6,021 | 0.18 | −0.86 to 1.04 | 0.48*** (r) | 5,293 |

| Subjective age—raw score | 55.98 | 13.88 | 12 to 112 | |||

| Number of chronic diseases in 2010 | 1.99 | 6,329 | 1.42 | 0 to 8 | 0.16*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Number ADL limitations in 2010 | 0.28 | 6,327 | 0.83 | 0 to 6 | 0.1*** (r) | 5,490 |

| Number IADL limitations in 2010 | 0.17 | 6,328 | 0.6 | 0 to 5 | 0.13*** (r) | 5,491 |

| Sense of control—2010 | 4.82 | 6,279 | 0.93 | 1 to 6 | −0.18*** (r) | 5,461 |

| Chronological age—2010 | 66.29 | 6,329 | 9.95 | 51 to 101 | 0.02 (r) | 5,491 |

| Gender (female = 1) | 59.5% | 6,329 | 0 to 1 | 5.2* (F) | 5,491 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 6,324 | 1 to 4 | 3.24* (F) | 6,016 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.6% | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 15.9% | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Other | 2.7% | |||||

| Hispanic | 9.7% | |||||

| Wealth (inverse hyperbolic sine) | 10.69 | 6,329 | −14.34 to 17.83 | −0.03* (r) | 5,491 | |

| Number years of education | 13 | 6,305 | 2.94 | 0 to 17 | −0.08*** (r) | 5,469 |

| Marital status (widowed = 1) | 16.5% | 6,324 | 0 to 1 | 0.18 (F) | 5,488 | |

| Employment status (retired = 1) | 46.3% | 6,325 | 0 to 1 | 2.54 (F) | 5,489 | |

| Grandparent status (grandparent = 1) | 75.5% | 6,250 | 0 to 1 | 5.29* (F) | 5,429 | |

| Self-reported health | 3.28 | 6,327 | 1.04 | 1 to 5 | −0.22*** (r) | 5,490 |

| Cognition | 22.41 | 4,645 | 4.4 | 3 to 34 | −0.05** (r) | 3,984 |

| Self-reported vision | 4.6% | 6,320 | 0 to 1 | 29.29*** (F) | 5,484 | |

| Self-reported hearing | 4.4% | 6,327 | 0 to 1 | 2.81 (F) | 5,489 |

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. Bivariate associations with the proportional discrepancy measure of subjective age in 2014 were estimated with Pearson correlation for continuous variables and t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for categorical variables.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

The bivariate analysis results showed that all the variables except widowhood and retirement status, as well as poor hearing, were significantly associated with subjective age in 2014. The results indicated that baseline scores and change in the number of chronic diseases and limitations in ADLs and IADLs were positively correlated with subjective age in 2014. Sense of control at both time points were negatively correlated with subjective age in 2014. The correlation matrix for the key theoretical variables is presented in Table 2. The results showed that chronic diseases and functional limitations were positively correlated with each other, negatively correlated with sense of control, and positively correlated with subjective age. Sense of control and subjective age were negatively correlated with each other.

| . | r (N) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . |

| Subjective age—2014 | — | ||||

| Sense of control combined—2014 | −0.26*** (5467) | — | |||

| Change in number of chronic diseases | 0.06*** (5491) | −0.07*** (5712) | — | ||

| Change in number of ADL limitations | 0.1*** (5483) | −0.11*** (5704) | 0.06*** (6319) | — | |

| Change in number of IADL limitations | 0.03* (5491) | −0.16*** (5712) | 0.07*** (6327) | 0.37*** (6317) | — |

| . | r (N) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . |

| Subjective age—2014 | — | ||||

| Sense of control combined—2014 | −0.26*** (5467) | — | |||

| Change in number of chronic diseases | 0.06*** (5491) | −0.07*** (5712) | — | ||

| Change in number of ADL limitations | 0.1*** (5483) | −0.11*** (5704) | 0.06*** (6319) | — | |

| Change in number of IADL limitations | 0.03* (5491) | −0.16*** (5712) | 0.07*** (6327) | 0.37*** (6317) | — |

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

| . | r (N) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . |

| Subjective age—2014 | — | ||||

| Sense of control combined—2014 | −0.26*** (5467) | — | |||

| Change in number of chronic diseases | 0.06*** (5491) | −0.07*** (5712) | — | ||

| Change in number of ADL limitations | 0.1*** (5483) | −0.11*** (5704) | 0.06*** (6319) | — | |

| Change in number of IADL limitations | 0.03* (5491) | −0.16*** (5712) | 0.07*** (6327) | 0.37*** (6317) | — |

| . | r (N) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . |

| Subjective age—2014 | — | ||||

| Sense of control combined—2014 | −0.26*** (5467) | — | |||

| Change in number of chronic diseases | 0.06*** (5491) | −0.07*** (5712) | — | ||

| Change in number of ADL limitations | 0.1*** (5483) | −0.11*** (5704) | 0.06*** (6319) | — | |

| Change in number of IADL limitations | 0.03* (5491) | −0.16*** (5712) | 0.07*** (6327) | 0.37*** (6317) | — |

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

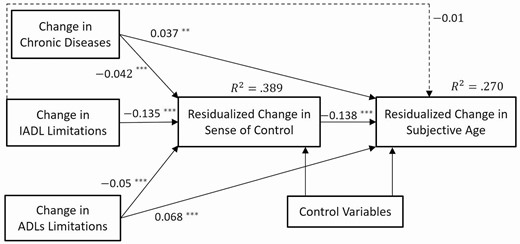

Results from the path analysis model are reported in Table 3. As also depicted in Figure 2, chronic diseases and ADL and IADL limitations show significant indirect associations with subjective age via a diminishing sense of control (0.006, p = .000; 0.007, p = .003; 0.019, p = .000, respectively). In addition to the mediational paths, chronic diseases and ADL limitations also show significant direct associations with subjective age (0.037, p = .005; 0.068, p = .001, respectively). The RMSEA fit statistic for the final model was 0.027, being below the desirable 0.05, and the CFI was 0.996, above the recommended level of 0.95. The direction of association and level of significance of these paths are stable and this model provides a better fit to the data compared with the model run in an earlier step with no control variables (see Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 1). Also, the patterns of associations and their statistical significance levels remained the same when we re-estimated the models with proportional subjective age score winsorized based on interquartile range (see Supplementary Table 2 and Figure 2) and with respondents lost to attrition at follow-up in 2014 (see Supplementary Table 3 and Figure 3). Finally, the results also remained consistent when we estimated a model with cross-sectional data from 2010 only, but this model had poorer fit statistics (see Supplementary Table 4 and Figure 4).

Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects of Chronic Diseases, Functional Limitations, and Sense of Control on Subjective Age

| Paths . | Direct . | Indirect . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of chronic diseases—sense of control—subjective age | 0.037** | 0.006*** | 0.043*** |

| Number of IADL limitations—sense of control—subjective age | 0.010 | 0.019*** | 0.008 |

| Number of ADL limitations—sense of control—subjective age | 0.068*** | 0.007** | 0.075*** |

| Paths . | Direct . | Indirect . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of chronic diseases—sense of control—subjective age | 0.037** | 0.006*** | 0.043*** |

| Number of IADL limitations—sense of control—subjective age | 0.010 | 0.019*** | 0.008 |

| Number of ADL limitations—sense of control—subjective age | 0.068*** | 0.007** | 0.075*** |

Notes: N = 6,329. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects of Chronic Diseases, Functional Limitations, and Sense of Control on Subjective Age

| Paths . | Direct . | Indirect . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of chronic diseases—sense of control—subjective age | 0.037** | 0.006*** | 0.043*** |

| Number of IADL limitations—sense of control—subjective age | 0.010 | 0.019*** | 0.008 |

| Number of ADL limitations—sense of control—subjective age | 0.068*** | 0.007** | 0.075*** |

| Paths . | Direct . | Indirect . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of chronic diseases—sense of control—subjective age | 0.037** | 0.006*** | 0.043*** |

| Number of IADL limitations—sense of control—subjective age | 0.010 | 0.019*** | 0.008 |

| Number of ADL limitations—sense of control—subjective age | 0.068*** | 0.007** | 0.075*** |

Notes: N = 6,329. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Significant direct and indirect pathways for the association between chronic diseases, functional limitations, sense of control and subjective age. N = 6,329. CFI = 0.996; RMSEA = .027. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discussion

The primary aims of this article were to examine whether a change in the number of chronic diseases and change in functional limitations were associated with subjective age, and whether the psychological resource of sense of control mediated these relationships. To our knowledge, this is the first study to have included both chronic diseases and functional impairment in the same model to examine its associated with subjective age through the mediation role of sense of control. The respondents, on average, reported feeling a decade younger than their chronological age, which is consistent with most prior studies (Bergland et al., 2014; Stephan et al., 2015). A review of the mean raw subjective age scores shows respondents felt younger over the observation period. However, in terms of proportional score, their subjective age appears to be stable during the follow-up period. These results are in line with the distal life-span framework of Montepare (2009), which posits that beyond young adulthood individuals may anchor their subjective age closer to the prime of their development, and thus, they report feeling younger than their chronological age.

Chronic diseases and ADL limitations had a direct positive association with subjective age. This observation also supports Montepare’s (2009) proposition that proximal factors, such as the onset of poor health, may disrupt the distal life-span framework of subjective age and reanchor middle-aged and older adults’ subjective age closer to an older subjective age. Since the risk of morbidity and functional dependency increases at older ages, experiencing chronic diseases and functional limitations may have cued the respondents to feel older than they felt earlier (Kotter-Grühn et al., 2016). Sense of control was a key psychological resource for coping with life’s demands, allowing older adults to continue to function as in younger years. The path model results showed that one standard deviation increase in sense of control during the follow-up period resulted in respondents reporting that they felt 0.138 standard deviations younger than at baseline. This significant association between sense of control and subjective age has also been demonstrated in earlier studies (Bergland et al., 2014; Bowling et al., 2005; Bellingtier & Neupert, 2020).

As postulated by the Deterioration Model, the findings from the path model supported our hypothesis that an increase in the number of chronic diseases and limitations in ADLs and IADLs would be associated with an increase in subjective age via a diminished sense of control. The associations between chronic diseases and ADL limitations with subjective age were partially mediated and the association between IADL limitations and subjective age was fully mediated by sense of control. Chronic diseases such as cancer, stroke, heart conditions, and arthritis can be debilitating and likely interfered with some older adults’ ability to carry on with their daily duties and normal routines as they did before being diagnosed. Similarly, functional limitations often curtail older adults’ autonomy and independence, at least in the initial stages. Older adults may have to depend on support provided by other persons in their social network or rely on assistive devices and services. Restrictions in daily life due to chronic diseases and functional limitations may, in turn, reduce older adults’ sense of control, thereby making them feel older. Some debilitating chronic diseases and ADL limitations may be more intensely felt and these restrictions likely have a larger impact than IADL limitations. Therefore, chronic diseases and ADL limitations may act as a stronger reminder of the finitude of life; this may explain why there is a direct association between these two variables and subjective age, in addition to being mediated by diminution of sense of control.

Similar to our findings, Schafer and Shippee (2010) found that sense of control mediated the relationship between incident chronic diseases and subjective age. However, Tovel et al. (2019) found no significant mediation role for sense of control between functional limitations and attitudes towards aging. Subjective age and attitudes towards aging are related, but unique concepts. This may partially explain the differences between the Tovel et al.’s study and ours. An alternative explanation for the difference in findings may be due to Tovel and colleagues’ research design; their sample was considerably older, on average, than respondents in the Schafer and Shippee’s (2010) study and in our sample (mean age—81 years vs. 47 years vs. 57 years, respectively). Also, Tovel et al. (2019) used baseline functional status instead of specifying it as a change in functional status. Recent evidence suggests that health deterioration may be more consequential psychologically to middle-aged individuals than to older adults, and incident health decline may have a stronger association with subjective age than baseline health (Prasad et al., 2022). Being a relatively stable construct across the life course, sense of control may not fluctuate on a day-to-day basis (Slagsvold & Sørensen, 2013), potentially explaining the null findings for other mediation studies using a daily diary method (Bellingtier et al., 2017). The negative effects of chronic diseases and functional limitations may take longer than a few days to affect sense of control and eventually translate into subjective age. Although the impression of adverse health events on subjective age may fade over time, for some older adults the effect may last for years, as seen in our study, and may even linger for up to a decade, found in Schafer and Shippee (2010).

Limitations

Although this study provided evidence for one of the pathways between health and subjective age, it also had some limitations. The relationship between health, sense of control, and subjective age was likely reciprocal and cross-lagged analyses may offer more evidence for establishing causality (Spuling et al., 2013). Qualitative data collected through interviews may also offer more information on the timing of the influence of chronic diseases and functional limitations for sense of control and subjective age. The scientific literature also suggested that health probably has a stronger influence on subjective age among middle-aged individuals than among older adults, but the opposite may likely be the case with respect to the influence of sense of control for subjective age (Bellingtier & Neupert, 2020; Infurna et al., 2010; Prasad et al., 2022). More analyses are needed to unravel this possibility.

Conclusion

This study contributed to the scientific literature by examining sense of control as one of the hypothesized pathways for the relationship between chronic diseases, functional limitations, and subjective age. Most people in their later years are likely to live with chronic diseases and may experience functional limitations for at least some periods of their life. These health challenges are shown to make people feel older. As a potential marker of future health and well-being, subjective age may be helpful for identifying vulnerable, at-risk populations. Appropriate counseling and resources at the time of diagnosis and management of these chronic diseases and the onset of functional limitations may help mitigate the downstream adverse health effects of older subjective age. Interventions aimed at bolstering sense of control among adults with chronic diseases and functional dependencies may be especially helpful in preserving aging individuals’ quality of life (Bellingtier & Neupert, 2020).

Acknowledgments

The first author thank Professor Kyungmin Kim, PhD, for initial methodological mentoring. If required, our analytic methods and study material will be made available for other researchers. There was no preregistration for this study.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.