-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Changmin Peng, Laura L Hayman, Jan E Mutchler, Jeffrey A Burr, Friendship and Cognitive Functioning Among Married and Widowed Chinese Older Adults, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Volume 77, Issue 3, March 2022, Pages 567–576, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbab213

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Guided by the social convoy model, this study investigated the association between friendship and cognitive functioning among older Chinese adults, as well as the moderating effect of marital status (married vs widowed). We also explored whether depression might account for the link between friendship and cognitive functioning.

We used data from the China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey in 2014 (N = 8,482). Cognitive functioning was measured with the Mini-Mental State Examination instrument and friendship was assessed with a 3-item Lubben Social Network Scale. Linear regression and path analyses within a structural equation modeling framework were performed to examine the hypotheses.

Results indicated that friendship was significantly related to better cognitive functioning among older Chinese adults (β = 0.083, p < .001) and marital status moderated this association (β = −0.058, p < .01). In addition, depression partially mediated the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning (β = 0.015, p < .001).

The results implied that friendship is important for maintaining cognitive functioning in later life and widowed older Chinese adults may benefit more from friendship in its relationship to cognitive functioning than married older Chinese adults. Further, one potential pathway linking friendship to cognitive functioning may be through depression; however, more research is needed to support this finding. Intervention programs aimed at building friendship opportunities may be one way to achieve better cognitive aging.

Friendship is an important factor worth considering in helping older people achieve healthy aging. This specific type of social relationship is an important component of older adults’ social network in later life, especially among those whose social network is shrinking. Although family has traditionally been regarded as the main source of social support for older adults, especially in developing countries like China, friendship is increasingly one of the most important social connections that influence the health and well-being of older adults, partly due to decreasing fertility rates, rising life expectancy, family disruption, and greater geographic mobility (Blieszner et al., 2019; Wang & Wellman, 2010). Previous research demonstrated that older adults who have more friends in their social network have higher levels of happiness and life satisfaction (Chen et al., 2019; Lei et al., 2015) and lower levels of loneliness and depression (Chen et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021) than those who have fewer friends. Further, a friend-focused network was shown to be more beneficial in terms of physical health outcomes than a family-focused network (Li & Zhang, 2015). The beneficial effects of friendship may derive from its voluntary and mutually supportive nature, whereas family support is seen as an obligation, especially in China, where Confucian philosophy is deeply rooted. In general, unsatisfactory family relationships are more difficult to avoid than negative friendships. In addition, friends usually share similar generation and age characteristics, life experiences and normative expectations, and lifestyles; friends, therefore, are often more important than family as a source of companionship explained in part by their participation in informal social activities (Huxhold et al., 2014).

Friendship has also been shown to be significantly associated with cognitive functioning in later life (Li & Dong, 2018; Sharifian et al., 2019, 2020; Windsor et al., 2014; Zahodne et al., 2019). However, previous studies investigating the friendship–cognition relation were more likely to focus on friendship structures (e.g., size, contact frequency) and less on functional dimensions (e.g., perceived social support) of friendship. The current study employed a more comprehensive measure than most previous studies to capture both structural and functional aspects of friendship (Lubben et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2020). In addition, few studies have examined whether the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning varies across individuals’ sociodemographic characteristics. Further, the potential pathways that link friendship with cognitive functioning have also been underexplored (Blieszner et al., 2019). Finally, most studies in this area were conducted in western countries and friendship relationship with cognitive functioning in the Chinese context has not yet been fully examined. The rapidly aging Chinese population, and the increased geographic distance between generations due to expansive rural-to-urban migration, coupled with the underdeveloped long-term care and formal social support systems, make the exploration of the association between types of informal social support, such as friendship, and cognitive function, a contribution to the scholarly literature. To fill these gaps in the scientific literature, this study used the 2014 wave of the China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS) to examine the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning in older Chinese adults aged 60 and older and to investigate the moderating role of marital status (married and widowed groups) and the mediating role of depression for this association.

Cognitive Health and Cultural Change in the Chinese Context

Maintaining cognitive functioning at optimal levels throughout older adulthood is an important global health issue, including in China which has the largest older population. The number of Chinese adults aged 65 years and older is expected to be approximately 336 million by 2030 (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, 2018), and by 2050, 10 million older Chinese adults are expected to have Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD; Zhang et al., 2012). Cognitive dysfunction poses a heavy burden for older Chinese adults, their families, and the larger Chinese society. The economic cost of ADRD in China was estimated to be $167.74 billion in 2015, and is expected to reach $507.49 billion in 2030, and $1.89 trillion in 2050 (Jia et al., 2018). Cognitive impairment, a key risk factor for ADRD, is associated with poor health outcomes and increased mortality risk among older Chinese adults (Lv et al., 2019). The large number of older people with ADRD poses a substantial challenge for the sustainability of China’s health care system.

In China’s traditional filial piety culture, adult children have the primary responsibility for taking care of their older parents, including providing instrumental, emotional, and financial support for their activities of daily living (ADLs) in their later years. However, in recent decades, rapid demographic, economic, and social changes due to the urbanization and modernization of China have weakened to some degree the norms that guide intergenerational duties and responsibilities (Cheung & Kwan, 2009). In particular, the one-child policy, which began in 1980, led to a decrease in family size. In addition, many young adults from rural areas and small towns are flocking to cities for better job opportunities, which often increases the geographic distance between generations (Du, 2013). As a result, reduced fertility rates and large-scale migration have led to a shift in family structure from multigenerational families to more nuclear ones. For example, about 75% of older adults lived with their adult children in 1982 (Cartier, 1995), but more than half of older adults in recent years lived alone or with their spouse only (Tang et al., 2020). The weakened support function of the Chinese family often forces older adults to rely more on their friends for support.

Friendship and Cognitive Functioning in Later Life

Recognizing that friendship is an important part of older adults’ social networks and a growing source of social support in recent decades, attention to examining the association between friendship characteristics and physical and mental health outcomes has also grown (Blieszner et al., 2019; Shiovitz-Ezra & Litwin, 2012). The social convoy model suggests that individuals, throughout their life course, are surrounded by a group of supportive family and friends (Antonucci et al., 2014). These supportive convoys of social relationships vary in their quality (e.g., negative and positive relationship), function (e.g., instrumental and emotional support), and structure (e.g., size, composition, and frequency of contact), depending on individual characteristics, and they have important implications for health and well-being. In later life, people may reduce their social interactions due to labor market exits, losing family members, and having limited energy. The social convoy model is widely used by scholars to explain the link between social relationships and health in later life.

The association between different dimensions of friendship and cognitive functioning has been documented in studies of western societies. For the structural aspect of friendship, the most common focus in friendship studies, research found that older adults reporting having any friends or having a greater proportion of friends in their social network had better cognitive performance (Li & Dong, 2018; Sharifian et al., 2019) and a slower rate of cognitive decline (Béland et al., 2005), along with better initial memory and a slower rate of decline in memory function (Giles et al., 2012). Further, older adults who had a higher frequency of contact with their friends also reported better global cognitive functioning (Ybarra et al., 2008) and executive function (Sharifian et al., 2020), better initial episodic memory and slower subsequent memory decline than their counterparts (Zahodne et al., 2019; Zunzunegui et al., 2003). These studies generally supported the expectation that friendship structure was related to better cognitive functioning. However, the cross-sectional research designs and longitudinal research designs with short time intervals and a narrow focus on the structural dimension of friendships limit our understanding of this understudied issue. In addition, people with poor cognitive health may not be able to maintain friendships and a reduced friendship network may actually be a marker of the presence of cognitive impairment or dementia.

Regarding the quality aspect of friendships, a limited number of studies found that engaging in positive interactions with friends was associated with better episodic memory (Windsor et al., 2014), while having a strained relationship with friends was associated with worse episodic memory (Zahodne et al., 2019). In terms of the functional aspect of friendship, although a cross-sectional study conducted by Yeh and Liu (2003) found that perceived positive support from friends had a statistically significant association with better cognitive functioning among older adults in Taiwan, the study did not indicate whether the kind of support received from friends was related to later-life cognitive functioning. Thus, more studies are needed in this area.

Several explanations based on the social convoy model have been offered to help us understand better the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning. First, interaction with friends appears to stimulate the brain, affecting cognitive functioning by providing individuals with more opportunities to exchange and access information, increasing positive affect, and engaging in more intellectually stimulating social activities (Huxhold et al., 2014). Second, feeling cared for and supported by friends increases a sense of connection, self-worth, competence, and control over life through shared activities and communication, which may contribute to the development and maintenance of cognitive functioning. However, the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning in eastern cultures, especially in China, is not well-understood. To our knowledge, only one study examined this association in China, focusing on the oldest-old population (Wang et al., 2015). In addition, most of the studies from different parts of the world explored the relationship between the structural aspect of friendship and cognitive functioning, making it difficult to understand the association between multidimensional friendship characteristics and cognitive function.

Married and Widowed Older Adults

There is general agreement that marriage benefits health, with married adults typically reporting better health than those with other marital statuses (widowed, divorced, and never married). Older adults are more likely to experience the loss of their spouse through widowhood compared to younger adults and spouses are the main source of support in later life (Roth & Peng, 2021). Being widowed or divorced without spousal support can be detrimental to older adults’ psychological and emotional status and may be associated with a decline in their mental health, including poor cognitive performance and high risk of social isolation and mortality (Barragán-García et al., 2021; Monserud & Wong, 2015; Peng & Roth, 2021; Roth & Peng, 2021).

Widowed and divorced older adults may not have as many family ties as married older adults; thus, friendship may be a key component of the social network of older adults who have experienced marital disruption (Schnettler & Wöhler, 2016). Therefore, interactions with friends may have greater benefit for cognitive functioning in widowed and divorced older adults when compared to married older adults whose spouses provide critical support. Further, compared to western countries, China has a weak social service “safety net,” especially with respect to long-term care; thus, widows are more likely than married persons to suffer from children’s migration to urban areas. Informal support might be more important for Chinese older adults than in western countries with more developed formal support systems, including public pension systems. This study thus investigated whether the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning would be different for married and widowed older Chinese adults (the CLASS contains too few cases for reliable analyses of the divorced/separated and never married persons).

Role of Depression

Depression is considered as one of the most prevalent mental health problems and a major cause of disease burden in later life, as older adults are more likely to encounter a range of stressful events, such as retirement, poverty, loss of significant others, decline in physical health, chronic pain, loneliness, and social withdrawal (Li et al., 2014; Santini et al., 2015). Depression is likely to result from dissatisfaction with or experiencing unmet needs associated with one’s social relationships (Blieszner et al., 2019; Ten Bruggencate et al, 2018). Previous studies suggested large and diverse social networks, especially those that contain friends, are protective against depression (Santini et al., 2015). For example, Han and colleagues (2019) found a significant association between friendship and depression among married couples. Findings from a study by Chen et al. (2019) indicated having more friends was associated with a lower level of depression. In addition, depression is a well-known risk factor for cognitive health (Diniz et al., 2013; Donovan et al., 2017). Evidence shows depression is generally found to be associated with lower scores in cognitive performance (Wei et al., 2019) and a significant contributor to major cognitive impairment (Richard et al., 2013). Therefore, in this study we explored whether depressive symptoms may be a possible pathway linking friendship to cognitive functioning in older Chinese adults.

The Present Study

Guided by the social convoy model and findings from the existing scientific literature, this study was designed to examine the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning, along with the moderating effects of marital status among older Chinese adults. We also introduced an exploratory analysis of one possible pathway linking friendship and cognition, depressive symptoms. The following three hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Friendship is positively associated with cognitive functioning. Older Chinese adults who perceived higher levels of social support from friends have better cognitive functioning than those who perceived lower levels of friend support.

Hypothesis 2: Marital status moderates the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning, whereby the association would be stronger for widowed older Chinese adults than for married older Chinese adults.

Hypothesis 3: Number of depressive symptoms mediate the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning. Older Chinese adults who have higher levels of friend support would experience fewer depressive symptoms and those with fewer depressive symptoms would have better cognitive functioning, while those who have lower levels of friend support would experience more depressive symptoms and worse cognitive functioning.

Method

Data and Sample

The CLASS, a nationally representative data survey of Chinese older adults aged 60 and older, was the source of data for this study. CLASS, collected by Renmin University of China, adopts a multistage stratified sampling design to select one eligible respondent from each sampled household. The survey was first conducted with 11,511 respondents in 2014 and was followed up every 2 years. New respondents were added to each wave to replenish the sample. The CLASS contains rich information about respondents’ demographic characteristics, economic standings, social adjustment, attitudes toward aging, intergenerational support, coping strategy, and physical and mental health status, and was designed to help understand the problems and challenges faced by older Chinese adults during the aging process.

The study sample was restricted to older adults who completed the baseline survey. The CLASS excluded 2,867 respondents who made three or more mistakes on five cognitive questions in the screening test; these respondents were considered incapable of answering the subjective evaluation measures, such as cognitive functioning and depression. We further excluded 99 divorced respondents and 52 never married respondents from the analyses, and one respondent with missing information on age. This cross-sectional study included 8,482 respondents.

Measures

Cognitive functioning

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) instrument, modified for the Chinese context, was used to measure respondents’ cognitive functioning, including orientation, memory, and calculation (Folstein et al., 1975). Orientation was assessed with five questions; respondents were asked to name today’s date, the village’s name, the date of National Day, the current president’s name, and the lunar calendar year (1 = correct, 0 = incorrect; range = 0–5). Memory function included immediate word recall and delayed word recall, where respondents were required to recall three simple Chinese words immediately and several minutes after hearing them (range = 0–6). Calculation ability was measured by asking respondents to count backwards from 100 by 7s five consecutive times (range = 0–5). The sum score of these three dimensions was used to represent respondents’ cognitive functioning, with higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning. As mentioned earlier, respondents who answered at least three questions correctly on orientation function were considered to have the cognitive ability to take the full MMSE test; the final cognitive functioning score ranged from 3 to 16.

Depressive symptoms

A shortened version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression scale with nine items was adopted to measure possible depression (Santor & Coyne, 1997). Respondents were asked to report the frequency of the following feelings in the past week: was happy, enjoyed life, felt pleasure, felt lonely, felt upset, had restless sleep, felt useless, had nothing to do, and had poor appetite. Respondents’ responses to each item were assessed on a 3-point scale (0 = rarely or none of the time, 1 = some of the time, 2 = most of the time). The first three items were reverse-coded, and all items were summed to represent respondents’ depressive symptoms score with a higher score indicating a higher level of depression (range = 0–18; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76).

Friendship

An abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS; Lubben et al., 2006) was used to evaluate respondents’ friendship status. Respondents were asked to report: (a) “the number of friends they could meet or contact each month” (i.e., frequency of contact; the presence and quantity of potential support resources that a person expects from friends), (b) “the number of friends they feel comfortable talking with about personal matters” (i.e., emotional support from friends), and (c) “the number of friends they could call on for help, if needed” (i.e., instrumental support from friends). These self-reported measures reflect respondent’s perceived availability of social support from friends. Respondents’ responses to each item were assessed on a 6-point scale (0 = none, 1 = one, 2 = two, 3 = three or four, 4 = five to eight, 5 = nine and above). The mean score across the three items was calculated, with a higher score representing perceived higher levels of friend support (range = 0–5, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85).

Covariates

We controlled for a range of sociodemographic and health factors that could confound the association among friendship and cognitive functioning, including age group (1 = 60–74, 0 = 75 and older), gender (1 = female, 0 = male), education (1 = no formal education, 2 = elementary or middle school, 3 = high school and above), marital status (1 = married, 0 = widowed; the CHARLS contained few respondents who were divorced/separated or never married groups), hukou registration status (1 = rural hukou, 0 = nonrural hukou), annual income (100$ = 700 yuan, range = 0–960,000, log-transformed), self-rated health (1 = very unhealthy, 2 = unhealthy, 3 = general, 4 = healthy, 5 = very healthy), working for pay (1 = yes, 0 = no), chronic diseases (1 = yes, 0 = no), and number of ADL limitations (including bathing, dressing, eating, toileting, walking, and getting out of bed; range = 0–6).

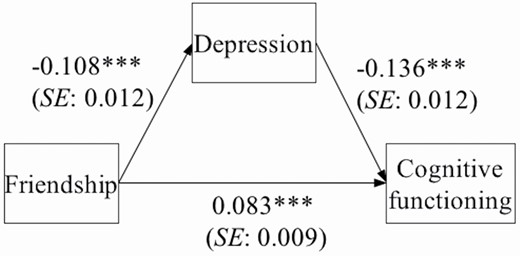

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample characteristics; group differences between married and widowed older adults were tested using a t test for continuous variables and a chi-squared test for categorical variables (Table 1). Linear regression modeling and path analysis within a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework were then performed. First, we examined the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning, including all of the covariates with a linear regression model (Table 2, Model 1). Second, we examined whether marital status moderates the friendship–cognition link by adding an interaction term friendship × marital status to the linear regression model (Table 2, Model 2). Third, we explored the mediating effect of depression for the association between friendship and cognitive functioning with SEM, using the MODEL INDIRECT command in Mplus (Figure 1).

| . | Full sample . | Married (n = 6,122) . | Widowed (n = 2,360) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | M (SD) . | M (SD) . | M (SD) . | t or χ 2 . |

| Variables | ||||

| Friendship (0–5) | 2.18 (1.56) | 2.21 (0.02) | 2.09 (0.03) | −3.15** |

| Depressive symptoms (0–18) | 4.57 (3.56) | 4.17 (0.04) | 5.50 (0.08) | 15.05*** |

| Cognitive functioning (3–16) | 13.13 (3.01) | 13.46 (0.04) | 12.26 (0.07) | −16.74*** |

| Covariates | ||||

| Age group 60–74, % | 75.22 | 83.26 | 54.36 | 762.83*** |

| Female, % | 46.13 | 38.21 | 66.68 | 555.41*** |

| Education, % | 407.35*** | |||

| No formal education | 22.90 | 17.31 | 37.41 | |

| Elementary/middle school | 57.32 | 60.40 | 49.32 | |

| High school and above | 19.78 | 22.29 | 13.26 | |

| Rural hukou status, % | 44.36 | 42.98 | 47.92 | 16.82*** |

| Annual income; yuan (0–960,000) | 21,060 (25,519) | 22,456 (321.49) | 17,385 (617.46) | −7.85*** |

| Income (logged: 0–13.77) | 9.16 (1.90) | 9.27 (0.02) | 8.85 (0.04) | −8.87*** |

| Had a chronic disease, % | 72.33 | 70.36 | 77.45 | 42.40*** |

| ADL limitations (0–6) | 0.11 (0.59) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 5.19*** |

| Self-rated health (1–5) | 3.32 (1.07) | 3.36 (0.01) | 3.20 (0.02) | −6.20*** |

| Working for pay, % | 19.91 | 23.24 | 11.24 | 153.67*** |

| . | Full sample . | Married (n = 6,122) . | Widowed (n = 2,360) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | M (SD) . | M (SD) . | M (SD) . | t or χ 2 . |

| Variables | ||||

| Friendship (0–5) | 2.18 (1.56) | 2.21 (0.02) | 2.09 (0.03) | −3.15** |

| Depressive symptoms (0–18) | 4.57 (3.56) | 4.17 (0.04) | 5.50 (0.08) | 15.05*** |

| Cognitive functioning (3–16) | 13.13 (3.01) | 13.46 (0.04) | 12.26 (0.07) | −16.74*** |

| Covariates | ||||

| Age group 60–74, % | 75.22 | 83.26 | 54.36 | 762.83*** |

| Female, % | 46.13 | 38.21 | 66.68 | 555.41*** |

| Education, % | 407.35*** | |||

| No formal education | 22.90 | 17.31 | 37.41 | |

| Elementary/middle school | 57.32 | 60.40 | 49.32 | |

| High school and above | 19.78 | 22.29 | 13.26 | |

| Rural hukou status, % | 44.36 | 42.98 | 47.92 | 16.82*** |

| Annual income; yuan (0–960,000) | 21,060 (25,519) | 22,456 (321.49) | 17,385 (617.46) | −7.85*** |

| Income (logged: 0–13.77) | 9.16 (1.90) | 9.27 (0.02) | 8.85 (0.04) | −8.87*** |

| Had a chronic disease, % | 72.33 | 70.36 | 77.45 | 42.40*** |

| ADL limitations (0–6) | 0.11 (0.59) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 5.19*** |

| Self-rated health (1–5) | 3.32 (1.07) | 3.36 (0.01) | 3.20 (0.02) | −6.20*** |

| Working for pay, % | 19.91 | 23.24 | 11.24 | 153.67*** |

Notes: N = 8,482. ADL = activities of daily living; CLASS = Chinese Longitudinal Aging Social Survey; SD = standard deviation.

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

| . | Full sample . | Married (n = 6,122) . | Widowed (n = 2,360) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | M (SD) . | M (SD) . | M (SD) . | t or χ 2 . |

| Variables | ||||

| Friendship (0–5) | 2.18 (1.56) | 2.21 (0.02) | 2.09 (0.03) | −3.15** |

| Depressive symptoms (0–18) | 4.57 (3.56) | 4.17 (0.04) | 5.50 (0.08) | 15.05*** |

| Cognitive functioning (3–16) | 13.13 (3.01) | 13.46 (0.04) | 12.26 (0.07) | −16.74*** |

| Covariates | ||||

| Age group 60–74, % | 75.22 | 83.26 | 54.36 | 762.83*** |

| Female, % | 46.13 | 38.21 | 66.68 | 555.41*** |

| Education, % | 407.35*** | |||

| No formal education | 22.90 | 17.31 | 37.41 | |

| Elementary/middle school | 57.32 | 60.40 | 49.32 | |

| High school and above | 19.78 | 22.29 | 13.26 | |

| Rural hukou status, % | 44.36 | 42.98 | 47.92 | 16.82*** |

| Annual income; yuan (0–960,000) | 21,060 (25,519) | 22,456 (321.49) | 17,385 (617.46) | −7.85*** |

| Income (logged: 0–13.77) | 9.16 (1.90) | 9.27 (0.02) | 8.85 (0.04) | −8.87*** |

| Had a chronic disease, % | 72.33 | 70.36 | 77.45 | 42.40*** |

| ADL limitations (0–6) | 0.11 (0.59) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 5.19*** |

| Self-rated health (1–5) | 3.32 (1.07) | 3.36 (0.01) | 3.20 (0.02) | −6.20*** |

| Working for pay, % | 19.91 | 23.24 | 11.24 | 153.67*** |

| . | Full sample . | Married (n = 6,122) . | Widowed (n = 2,360) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | M (SD) . | M (SD) . | M (SD) . | t or χ 2 . |

| Variables | ||||

| Friendship (0–5) | 2.18 (1.56) | 2.21 (0.02) | 2.09 (0.03) | −3.15** |

| Depressive symptoms (0–18) | 4.57 (3.56) | 4.17 (0.04) | 5.50 (0.08) | 15.05*** |

| Cognitive functioning (3–16) | 13.13 (3.01) | 13.46 (0.04) | 12.26 (0.07) | −16.74*** |

| Covariates | ||||

| Age group 60–74, % | 75.22 | 83.26 | 54.36 | 762.83*** |

| Female, % | 46.13 | 38.21 | 66.68 | 555.41*** |

| Education, % | 407.35*** | |||

| No formal education | 22.90 | 17.31 | 37.41 | |

| Elementary/middle school | 57.32 | 60.40 | 49.32 | |

| High school and above | 19.78 | 22.29 | 13.26 | |

| Rural hukou status, % | 44.36 | 42.98 | 47.92 | 16.82*** |

| Annual income; yuan (0–960,000) | 21,060 (25,519) | 22,456 (321.49) | 17,385 (617.46) | −7.85*** |

| Income (logged: 0–13.77) | 9.16 (1.90) | 9.27 (0.02) | 8.85 (0.04) | −8.87*** |

| Had a chronic disease, % | 72.33 | 70.36 | 77.45 | 42.40*** |

| ADL limitations (0–6) | 0.11 (0.59) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 5.19*** |

| Self-rated health (1–5) | 3.32 (1.07) | 3.36 (0.01) | 3.20 (0.02) | −6.20*** |

| Working for pay, % | 19.91 | 23.24 | 11.24 | 153.67*** |

Notes: N = 8,482. ADL = activities of daily living; CLASS = Chinese Longitudinal Aging Social Survey; SD = standard deviation.

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

Regression Results for Friendship, Cognitive Functioning, and Marital Status

| Effect . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | β . | SE . | β . | SE . |

| Friendship | 0.083*** | 0.009 | 0.133*** | 0.020 |

| Friendship × Married | −0.058** | 0.019 | ||

| Age group 60–74 | 0.140*** | 0.011 | 0.140*** | 0.011 |

| Female | −0.018 | 0.011 | −0.019 | 0.011 |

| Marrieda | 0.040*** | 0.011 | 0.082*** | 0.019 |

| Elementary/middle schoolb | 0.231*** | 0.014 | 0.231*** | 0.014 |

| High school and aboveb | 0.257*** | 0.013 | 0.257*** | 0.013 |

| Rural hukou status | −0.079*** | 0.013 | −0.078*** | 0.013 |

| Annual income | 0.070*** | 0.014 | 0.070*** | 0.014 |

| Had a chronic disease | −0.038*** | 0.009 | −0.038** | 0.009 |

| ADL limitations | −0.039** | 0.014 | −0.038** | 0.014 |

| Self-rated health | 0.055*** | 0.011 | 0.055*** | 0.011 |

| Working for pay | −0.017 | 0.010 | −0.018 | 0.010 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.136*** | 0.012 | −0.136*** | 0.012 |

| Effect . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | β . | SE . | β . | SE . |

| Friendship | 0.083*** | 0.009 | 0.133*** | 0.020 |

| Friendship × Married | −0.058** | 0.019 | ||

| Age group 60–74 | 0.140*** | 0.011 | 0.140*** | 0.011 |

| Female | −0.018 | 0.011 | −0.019 | 0.011 |

| Marrieda | 0.040*** | 0.011 | 0.082*** | 0.019 |

| Elementary/middle schoolb | 0.231*** | 0.014 | 0.231*** | 0.014 |

| High school and aboveb | 0.257*** | 0.013 | 0.257*** | 0.013 |

| Rural hukou status | −0.079*** | 0.013 | −0.078*** | 0.013 |

| Annual income | 0.070*** | 0.014 | 0.070*** | 0.014 |

| Had a chronic disease | −0.038*** | 0.009 | −0.038** | 0.009 |

| ADL limitations | −0.039** | 0.014 | −0.038** | 0.014 |

| Self-rated health | 0.055*** | 0.011 | 0.055*** | 0.011 |

| Working for pay | −0.017 | 0.010 | −0.018 | 0.010 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.136*** | 0.012 | −0.136*** | 0.012 |

Notes: N = 8,482. Standardized coefficients are reported. ADL = activities of daily living; SE = standard error.

aReference group = widowed.

bReference group = no formal education.

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

Regression Results for Friendship, Cognitive Functioning, and Marital Status

| Effect . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | β . | SE . | β . | SE . |

| Friendship | 0.083*** | 0.009 | 0.133*** | 0.020 |

| Friendship × Married | −0.058** | 0.019 | ||

| Age group 60–74 | 0.140*** | 0.011 | 0.140*** | 0.011 |

| Female | −0.018 | 0.011 | −0.019 | 0.011 |

| Marrieda | 0.040*** | 0.011 | 0.082*** | 0.019 |

| Elementary/middle schoolb | 0.231*** | 0.014 | 0.231*** | 0.014 |

| High school and aboveb | 0.257*** | 0.013 | 0.257*** | 0.013 |

| Rural hukou status | −0.079*** | 0.013 | −0.078*** | 0.013 |

| Annual income | 0.070*** | 0.014 | 0.070*** | 0.014 |

| Had a chronic disease | −0.038*** | 0.009 | −0.038** | 0.009 |

| ADL limitations | −0.039** | 0.014 | −0.038** | 0.014 |

| Self-rated health | 0.055*** | 0.011 | 0.055*** | 0.011 |

| Working for pay | −0.017 | 0.010 | −0.018 | 0.010 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.136*** | 0.012 | −0.136*** | 0.012 |

| Effect . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | β . | SE . | β . | SE . |

| Friendship | 0.083*** | 0.009 | 0.133*** | 0.020 |

| Friendship × Married | −0.058** | 0.019 | ||

| Age group 60–74 | 0.140*** | 0.011 | 0.140*** | 0.011 |

| Female | −0.018 | 0.011 | −0.019 | 0.011 |

| Marrieda | 0.040*** | 0.011 | 0.082*** | 0.019 |

| Elementary/middle schoolb | 0.231*** | 0.014 | 0.231*** | 0.014 |

| High school and aboveb | 0.257*** | 0.013 | 0.257*** | 0.013 |

| Rural hukou status | −0.079*** | 0.013 | −0.078*** | 0.013 |

| Annual income | 0.070*** | 0.014 | 0.070*** | 0.014 |

| Had a chronic disease | −0.038*** | 0.009 | −0.038** | 0.009 |

| ADL limitations | −0.039** | 0.014 | −0.038** | 0.014 |

| Self-rated health | 0.055*** | 0.011 | 0.055*** | 0.011 |

| Working for pay | −0.017 | 0.010 | −0.018 | 0.010 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.136*** | 0.012 | −0.136*** | 0.012 |

Notes: N = 8,482. Standardized coefficients are reported. ADL = activities of daily living; SE = standard error.

aReference group = widowed.

bReference group = no formal education.

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

Path analysis results for friendship, depression, and cognitive functioning. Notes: N = 8,482. Standardized coefficients were reported. Comparative fit index = 1.000, Tucker–Lewis index = 1.000, root mean square error of approximation = 0.000, standardized root mean square residual = 0.000. Covariates were controlled for the mediator and outcome. Covariates included: age, gender, marital status, education, hukou status, income, chronic diseases, activities of daily living, self-rated health, working for pay. ***p < .001.

The rate of missingness for most variables in this study was lower than 5%. The full information maximum likelihood method was used to handle missing data; a method that allowed the parameters to be estimated based on all available data, providing robust estimates. The maximum likelihood estimator with bootstrapping approach was performed to examine all coefficients; this approach is more conservative and accurate than other general approaches that assume parameter estimates to be normally distributed (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). For all the estimates, standardized coefficients were reported. We performed all analyses using Mplus (7.4 version).

Results

Study Sample Characteristics

Descriptive characteristics for the full study sample along with comparisons between married and widowed Chinese older adults are presented in Table 1. The mean score for friendship is 2.18 (SD = 1.56). The average score for depression is 4.57 (SD = 3.56) and for cognitive functioning is 13.13 (SD = 3.01). The widowed sample reported fewer friendships (t = −3.15, p < .01), higher levels of depression (t = 15.05, p < .001), and lower levels of cognitive functioning (t = −16.74, p < .001) compared to the married sample. Other significant differences between married and widowed groups were also observed across all demographic characteristics.

Associations Among Friendship, Marital Status, and Cognitive Functioning

Results from the regression analysis for the study sample are reported in Table 2. We examined the friendship–cognition relationship in Model 1, and found friendship was significantly associated with cognitive functioning (β = 0.083, SE = 0.009, p < .001). Thus, older Chinese adults who reported higher levels of social support from friends reported higher scores on cognitive functioning than those with lower levels of friend support. We examined the moderating effect of marital status on the association between friendship and cognitive functioning in Model 2. We found that marital status significantly moderated this association (β = −0.058, SE = 0.019, p = .002), showing that the friendship–cognition relationship is stronger for widowed older adults compared to married older adults (also see Supplementary Figure A).

We further explored the associations between cognitive function and the three components of friendship from the LSNS (the results are presented in Supplementary Table A). The findings showed that perceived higher levels of emotional support (β = 0.051, SE = 0.013, p < .001) and instrumental support (β = 0.035, SE = 0.014, p = .014) from friends were associated with better cognitive performance, while the frequency of contact with friends was not associated with cognitive functioning (β = 0.011, SE = 0.013, p = .428).

The Mediating Effect of Depressive Symptoms for the Association Between Friendship and Cognitive Functioning

We examined the potential mediating effect of depressive symptoms for the association between friendship and cognitive functioning in older Chinese adults, using path analysis combined with a bootstrapping technique. The results are presented graphically in Figure 1. We found friendship was significantly associated with cognitive functioning both directly and indirectly through depressive symptoms. Specifically, higher scores on the friendship LSNS was related to better cognitive functioning (β = 0.083, SE = 0.009, p < .001). Perceived high levels of friend support was associated with reporting fewer depressive symptoms (β = −0.108, SE = 0.012, p < .001), and reporting fewer depressive symptoms was associated with higher levels of cognitive functioning (β = −0.136, SE = 0.012, p < .001). Thus, we found initial evidence to suggest that depressive symptoms may partially mediate the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning, and the estimated indirect effect of friendship on cognitive functioning was 0.015 (−0.108 × −0.136; SE = 0.002, p < .001).

Discussion

China’s unprecedented rapid growth of its aging population accompanied by sociodemographic transformations occurring in China in recent decades have attracted scholars’ attention to the cognitive functioning of Chinese older adults. Social network characteristics, friendships in particular, are posited to be an important aspect for promoting and maintaining cognitive functioning in later life. This study examined the association between friendship and cognitive functioning along with the role of marital status and depression in helping to understand this association.

Our first hypothesis was supported. We found that friendship was significantly associated with cognitive functioning. Respondents with higher scores on the LSNS friendship measure reported better cognitive functioning than those with lower scores on this measure of friendship. This is in line with western studies that showed friendship may help preserve cognitive functioning in later life, as maintaining friendships requires more participation in shared physical and cognitive activities (Li & Dong, 2018; Sharifian et al., 2019). Importantly, most studies indicated structural aspects of friendship, such as frequency of contact, are associated with better cognitive performance (Sharifian et al., 2020; Ybarra et al., 2008; Zahodne et al., 2019; Zunzuncgui et al., 2003). Our study found that only functional components of friendship are associated with cognitive functioning and that functional aspects of friendship may play a larger role than structural components (Yeh & Liu, 2003). In other words, if the study design did not include multiple aspects of friendship network characteristics in the same model, it would be difficult to know what are the “active ingredients” at work (Barnes et al., 2004). Future studies should evaluate multiple components of friendship to detect the potential “active ingredients” related to better health outcomes.

This study also demonstrated that marital status moderated the association between friendship and cognitive functioning. We found that friendship had a stronger relationship on cognitive functioning in widowed older adults compared to their counterparts who were married. Thus, hypothesis 2 was supported, as well. As discussed earlier, friendship networks may be more important for widowed older adults than for married older adults because widowed persons did not experience daily spousal interactions along with social and economic support within the household, which are important resources for maintaining cognitive functioning (Barragán-García et al., 2021; Monserud & Wong, 2015). This implies widows may benefit more from friendship in its relation to cognitive functioning than married persons.

The findings also suggested that number of depressive symptoms may have mediated the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning, which supported our third hypothesis. Older adults who perceived higher levels of social support from friends reported relatively fewer depressive symptoms, which in turn was associated with better cognitive functioning. These results implied that friendship may be related to cognitive functioning through its relationship with self-reported number of depressive symptoms, which is consistent with earlier research suggesting that respondents with better friendships tended to report lower levels of depression (Han et al., 2019; Santini et al., 2015), and depression serves as an important risk factor for cognitive impairment (Richard et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2019).

These study findings have potential implications for clinical and public health practice including preventive interventions. Our findings indicated that maintaining friendship was beneficial for cognitive outcomes, suggesting that community organizations could provide more opportunities and create supportive environments for older adults to participate in a variety of formal and informal social activities (e.g., volunteering, social clubs, card games) to help foster new friendships and maintain strong bonds with existing friends. Because widowed older adults benefit more from friendships than married people, encouraging and helping them maintain meaningful social connections with friends may reduce the adverse effects of losing a partner. Intervention programs that focus on friendship development and communication skills may help older adults increase social interaction with friend-based networks. The application of modern communication technology and social media (e.g., WeChat, Weibo, Facebook) also makes it possible for older people to preserve their friendship through routine and daily contact, information sharing, and online support.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study had some limitations. First, due to the limitations of cross-sectional designs, especially for estimating indirect effects (Maxwell & Cole, 2007; O’Laughlin et al., 2018; Shrout, 2011), and the likelihood of omitted variable bias, the causal direction of the relationships among friendship and cognitive functioning cannot be determined. Further, individuals with better cognitive functioning may be more likely to develop and maintain larger friendship networks, suggesting a reciprocal relationship. Future studies based on longitudinal designs could be implemented to explore this bidirectional association and also whether friendship is associated with changes in cognitive functioning. Second, only respondents who were considered to be capable of completing the cognitive and depression measures by the CLASS survey team were included; thus, the sample in this study was more cognitively healthy than the Chinese population of persons 60 years old and older; consequently, the study results cannot be generalized to those older Chinese adults with more severe cognitive impairment. Also, clinical research has shown that education and age can affect MMSE scores. Future studies should replicate our study with a standardized MMSE instrument. Third, friendship was measured as the number of friends the respondents had contact with or could rely on; we did not have additional information about a third dimension of friendship, friendship quality (e.g., positive or negative relationship quality with friends). Future research that includes more dimensions of friendship, including number of friends, positive and negative friendship quality, and other friendship network composition indicators, would help us better understand the relationship between friendship and cognitive functioning.

Also, we were only able to examine the associations among friendship and cognitive functioning in married and widowed groups due to small sample sizes for never married and divorced persons in the CLASS (however, see Supplementary Table B). Future studies should explore whether these associations are applicable to never married and divorced or separated older adults in other developing countries where these forms of marital disruption are more common and where data are available. Whether marital quality and family support confound the friendship–cognition link is also worth studying; in a recent study, friendship was found to be more important for those with relatively poor marital quality and lower levels of family support (Han et al., 2019). Further, we engaged in additional exploratory analyses to identify whether age group and gender were potential moderators for the relationship between friendship and cognition. We found no significant effects (results available upon request).

In addition, other potential underlying mechanisms linking friendship and cognitive functioning need further investigation in the Chinese context, as well as in western countries. Health behaviors (e.g., alcohol consumption, smoking, and seeking health services) and social participation are possible pathways; for example, friends may promote social engagement and positive health behaviors, helping maintain cognitive functioning. Finally, because friendships can be developed and dissolved across the life course, it would be informative to know how friendship characteristics at different life stages shape later-life cognitive functioning trajectories.

Conclusion

Older adults in China are increasingly relying on friendship for support when they face health decline and social losses. This study contributed to the scientific literature in three ways: (a) by providing empirical evidence for the effects of friendship on cognitive functioning in the Chinese context; (b) by exploring how friendship affects cognitive outcomes depending on the demographic characteristics of an individual’s marital status; and (c) by offering insights into number of depressive symptoms as a specific pathway in which friendship may influence cognitive functioning among older Chinese adults.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Population Development Studies Center and Institute of Gerontology at Renmin University of China for making the data available to the public.

Author Contributions

C. Peng planned the study, performed statistical analyses, and wrote and revised the paper. L. L. Hayman and J. E. Mutchler helped to revise the paper. J. A. Burr provided guidance and helped plan and revise the paper.