-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yida Zhai, Declining U.S. Soft Power in East Asia: Evaluations of the U.S. COVID-19 Response by Citizens of China, Japan, and South Korea, Political Science Quarterly, 2025;, qqaf005, https://doi.org/10.1093/psquar/qqaf005

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A country's ability to handle emergencies reflects its soft power. This study examines how Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean citizens evaluated the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the differences among them. Cross-national surveys were conducted in these three East Asian countries. The results showed that all three countries' citizens unfavorably evaluated the U.S. performance in dealing with COVID-19. However, Japanese and South Korean citizens, to a certain degree, acknowledged the U.S. contribution to international cooperation to control the pandemic, whereas Chinese citizens maintained a negative evaluation thereof. National ingroup identity, such as belief in the superiority of one's home country's political system and nationalist orientations, along with relative comparisons between one's home country and the United States, predicted evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Chinese public exhibited a different reaction pattern than their Japanese and South Korean counterparts. The results elucidated the political-psychological underpinnings of evaluating a foreign country and highlighted the changing international relations in East Asia from the perspective of ordinary people.

The United States, a developed country with great economic power and medical resources, did not perform well during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Johns Hopkins University, nearly 1.1 million Americans died of COVID-19 and 102 million infection cases were reported during the 3 years following the diagnosis of the first COVID-19 case in the country on 20 January 2020.1 The United States leads the world in confirmed cases and deaths.2 Experts have concluded that the United States failed to effectively contain COVID-19.3 The Government Accountability Office reported persistent deficiencies in the preparedness and response efforts and designated the government's leadership and coordination of a range of public health emergencies as high risk.4 The United States' slow and flawed testing, inadequate tracing, isolating and quarantines, sidelining of experts, and confusing mask guidance were also blamed for the failure of its COVID-19 response.5

Public opinion surveys have shown that U.S. citizens were dissatisfied with the country's performance during the pandemic.6 What was the image of the U.S. response to COVID-19 in other countries? To some extent, a country's capability and success in dealing with a public health crisis show its soft power. In the context of increasing China–U.S. tensions, the soft power of the United States is critical to maintaining its influence on East Asian allies. The evaluation among the East Asian population of how the United States responded to the COVID-19 pandemic reveals the changing international relations in the region from the perspective of ordinary people. Political psychology has a long tradition in the research of the management of a country's reputation and emphasizes the importance of a better national image in foreign relations.7 Multiple factors are related to the perceptions of foreign countries, including psychological dispositions at individual levels and mass-media communication at country levels.8 A recent study documented Chinese people's widespread perception of the poor pandemic management in the United States.9 More broadly, the perception of the United States as a model country has declined among the Chinese public over the past decade.10 The Chinese Communist Party has leveraged the United States' flawed pandemic response to discredit democracy, leading to a negative perception among the Chinese people regarding democracy's capacity to effectively manage a public health crisis.11 In addition to China, Japan and South Korea also play important roles in East Asia. The present study extends this line of research and examines evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic by Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean citizens.

Various factors may affect the evaluations of the U.S. COVID-19 responses. This study adopts two theoretical approaches to explain how people perceive and evaluate a foreign country. First, the approach of political-psychological motives uses the psychological theory of ingroup identity and intergroup relations to understand the evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic by citizens from the three East Asian countries. Ingroup identity fosters ingroup favoritism and generates outgroup discrimination and hatred in a given situation.12 A high ingroup identity with one's own country can predict the evaluation of the U.S. COVID-19 response. Second, comparisons between the United States and one's own country may affect the evaluation of the United States in relative terms. This study analyzes the home country's economic situation and control of COVID-19 and examines their relationships with the evaluation of the United States' response to the pandemic.

Given the changing international relations in East Asia, for this study, China, Japan, and South Korea were selected as its sample. These three countries represent different interstate relationships with the United States, and their citizens' evaluations of the U.S. response to COVID-19 indicate the influence of the United States in East Asia. Japan and South Korea maintain friendly and cooperative relations with the United States, whereas tensions between China and the United States have been increasing in recent years. China's rise and assertive diplomacy have caused Japan and South Korea to be more concerned about their national security, and unfavorable perceptions of China have increased in the two countries.13 As a strategical force to balance China's influence in East Asia, both Japan and South Korea have strengthened their friendly and collaborative relationships with the United States.14 However, Japanese and South Korean citizens' unfavorable evaluations of the U.S. response to COVID-19 may shake public confidence in the United States among East Asian allies. In contrast, Chinese citizens' evaluation of the U.S. response to COVID-19 reflects the degree of the soft power of the United States in China, which is meaningful for understanding the prospects of China–U.S. relations. The relationships between political-psychological motives and evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic should vary among the three countries. The results show how these relationships are contingent on a specific country's context.

National Ingroup Identity and Evaluations of the U.S. Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

In political psychology, social identity is widely recognized as a cognitive motivation for people's attitudes toward outgroups. Social identity theory states that part of people's self-concept arises from membership in social groups.15 When people perceive the world, their attitudes are not only formed based on individual stance but are also influenced by their social identity. People spontaneously divide themselves and others into ingroups and outgroups, form a group-level definition of self (group members), and perceive and interact with others based on social identity.16 Social identity theory contends that the construction of social identity encourages people to favor their ingroups.17 For example, they evaluate ingroups and members more positively and maximize ingroups' benefits in the distribution of interests.18

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the strength of national ingroup identity heightened.19 On the one hand, emergencies and social crises pose threats to the normal lives of people who correspondingly have to seek risk reduction through cooperation and contributions to the ingroup.20 The perception of a common fate within the group increases ingroup identity.21 Facing the threat of COVID-19, people seek to reduce uncertainties and anxiety by attachment to their ingroups, which consequently elicits their sense of belonging to a common national ingroup. Such social identity helps increase group solidarity for responding to emergencies. On the other hand, the nation-state played a major role in dealing with the problems brought about by the pandemic. The state's measures, including protectionist trade policies, export restrictions on medical resources to other countries, the closure of borders, and vaccine nationalism, strengthened its citizens' national ingroup identity. An increase in exclusionist tendencies was also observed during the COVID-19 pandemic.22 Some countries' statesmen even intentionally manipulated national ingroup identity to secure domestic approval and maintain their rule during this public health crisis.

The present study examines two national ingroup identities. One is beliefs in the superiority of a national ingroup's political system in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. A political system is the basic institutional arrangement of a country's political power and shapes political actors' activities. During the pandemic, national ingroup favoritism was revealed in citizens' confidence in their country's political system in terms of effectively dealing with the outbreak of COVID-19. Although citizens in Japan and South Korea expressed discontent with their governments and politicians, their confidence in their political systems has remained stable.23 No evidence suggests that most Japanese and South Korean citizens want their political systems replaced by authoritarian alternatives. During the pandemic, people in the two countries held beliefs in the superiority of their political systems in dealing with the outbreak of COVID-19. Equally, the pandemic facilitated Chinese citizens' belief in the superiority of their political system. This is largely a consequence of the government's sophisticated discourse manipulation. As a national ingroup identity, the rhetoric that China's political system had an advantage in dealing with COVID-19 was constructed to reinforce domestic solidarity in China. Empirical studies have confirmed that Chinese citizens had high levels of confidence in their political system during the pandemic.24

The other ingroup identity is nationalist orientations, which reveal citizens' attachment to and identification with nation-states as their ingroup.25 People with high nationalist orientations value their membership in a nation more than do other groups, and they hold this national ingroup identity in social interactions.26 Nationalism not only incorporates favorable feelings for one's own country but also involves a feeling of superiority and dominance of one's nation over others.27 Nationalist orientations are associated with authoritarianism and an adherence to foreign countries' conspiracy theories.28 As an ingroup identity, nationalist orientations often thrive in the midst of emergencies or crises, because the latter create a threat to people of the same nation-state.29 The COVID-19 pandemic fueled a global rise in nationalism.30 As an ingroup identity, citizens' nationalist orientations should influence their evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Classic psychological experiments have found that competition for resources, status, and power causes intergroup rivalry.31 Moreover, even in the absence of realistic competition, ingroup-outgroup distinctions and ingroup identity can affect members' evaluation of outgroups.32 As ingroup identity motivates individuals to internalize the benefit or loss of the group as personal, rivalry with an outgroup causes individuals to perceive a threat from the outgroup and generates uncomfortable feelings.33 Thus, if the relationships between the groups are friendly and cooperative, members' ingroup identity does not generate negative sentiments about the outgroup. If intergroup relations are antagonistic and conflicting, ingroup identity generates outgroup discrimination and hatred. Under the influence of social identity, intergroup relations at the macro level affect the micro-level individual attitudes toward outgroups.

Japan and South Korea are Asian allies of the United States. There has been extensive and comprehensive cooperation between them in the economic, cultural, military, and national security fields. Given the friendly and cooperative relations between the two countries and the United States, Japanese and South Korean citizens' national ingroup identities do not necessarily generate negative attitudes toward the United States. In contrast, Sino-U.S. relations had worsened even before the COVID-19 pandemic.34 The Trump administration engaged in a trade war with China and launched sanctions against Chinese companies. During the pandemic, the United States played a leading role in criticizing China for its responsibility for the global spread of COVID-19 and blamed China for the increasing number of deaths in the United States. U.S. statesmen referred to COVID-19 as the “Wuhan virus” or the “Chinese virus” and claimed that the virus was leaked from a Chinese laboratory.35 Meanwhile, the Chinese government actively disseminated the U.S. criticism of China to the domestic audiences and propagandized that the United States sought to contain China's development and destabilize the regional order, and that it posed a great threat to China's national security. An increasing number of Chinese people agree with the government's rhetoric about the U.S. threat.36 The tensions between China and the United States cause Chinese citizens' ingroup favoritism to be associated with resentments of the United States. High national ingroup identity should negatively predict evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Relative Comparisons between the United States and One's Own Country

Foreign citizens' evaluation of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic is influenced not only by the U.S. actual performance but also by relative comparisons of the United States to their home countries. Social comparison theory states that people compare their ingroups and outgroups during the process of attitude formation.37 Group-based social comparison is a fundamental feature of group life relevant to one's social identity.38 If foreign citizens expressed strong discontent with their home country's performance in handling the COVID-19 pandemic, their evaluation of the U.S. response might be relatively high, even if the actual performance of the United States was poor, and vice versa.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, social comparisons between one's home country and foreign countries were primarily based on two policy objectives: achieve economic recovery and growth and control the spread of COVID-19. To a certain extent, these two objectives conflicted. Strict measures were effective in controlling infections but imposed considerable restrictions on economic activities and damaged economic growth. The balance between infection control and economic activity was determined by a specific country's national policies. China, Japan, and South Korea adopted different anti–COVID-19 policies, affecting each country's performance in controlling the spread of COVID-19 and realizing economic recovery.

The performance of one's home country serves as a benchmark for evaluating the U.S. response to COVID-19. China adopted the Zero COVID-19 policy that aimed to achieve zero infections by implementing mandatory quarantine, citywide lockdowns, and frequent nucleic acid tests.39 This policy contributed to reducing a large number of infections and deaths.40 Additionally, government propaganda praised China's success in controlling the spread of COVID-19 while stressing the incapacity and incompetency of the United States. For example, Chinese media represented the United States as experiencing multiple forms of chaos and criticized its failed response to the pandemic.41 Therefore, from the perspective of relative comparisons, the Chinese people's evaluation of their own country's control of COVID-19 might generate a negative evaluation of the U.S. response. However, the Zero COVID policy also dealt the country a severe economic blow.42 Because China's economy did not recover well, the Chinese people's evaluation of their own country's economic situation might not have significantly affected their evaluation of the U.S. response to COVID-19.

Although South Korea did not impose lockdowns, it also did not choose mitigation policies like those in Japan but instead adopted a containment approach, implementing large-scale testing, contact tracing, and isolation.43 Japan adopted a balanced policy that reconciled control of COVID-19 with the negative effects of countermeasures on the economy.44 Japan's anti–COVID-19 policy has been characterized by its soft request for citizens' “self-restraint.” Japanese citizens voluntarily complied with the government's requests, without the government using coercive measures. Because Japan and South Korea performed well during the COVID-19 pandemic, from the perspective of relative comparisons, their citizens' favorable evaluation of their home country's performance might be negatively associated with their evaluation of the U.S. response to COVID-19.

Data and Methods

Data

Cross-national surveys were conducted in China, Japan, and South Korea between January and February 2022. The three countries shared a common English questionnaire translated into the local languages. Zhongyan Technology was responsible for data collection in China, and Cross Marketing was responsible for data collection in Japan and South Korea. These are professional survey agencies that have administered many surveys in collaboration with academic institutions. The surveys were administered on the respective survey agency's platforms.45

We are aware of the weaknesses of web-based surveys and made efforts to improve the quality of our sample. First, we ensured that our sample covered the major geographic areas of the country surveyed. These surveys collected nationwide data rather than targeting residents of a specific region. Second, the surveys adhered to the quota sampling method by considering age, gender, educational level, and area of residence. These quotas reflect the demographic characteristics of the target population and increase the representativeness of the sample. We defined the subgroups of the population and the number of respondents for each group. The quotas vary across the three countries because the demographic features differ among them. Table A1 presents distribution of demographic variables for the sample.

Following the quota, the survey agencies randomly sent invitations to their registered respondents, via email or cell phone messages with a link, to participate in a social survey. Respondents interested in participating in the survey clicked on the link and were directed to an online questionnaire. After they read the introductory information and provided informed consent, they completed the online questionnaire. We finally obtained 1,000 respondents from each country. In the Chinese sample, the respondents were aged 18 to 68 years, with equal proportions of men and women. In the Japanese sample, the respondents were aged 18 to 79 years, and women and men accounted for 50.5 percent and 49.5 percent of respondents, respectively. In the South Korean sample, the respondents were aged from 18 to 79 years; women accounted for 49.3 percent and men accounted for 50.7 percent of the sample.

Dependent Variables

This study evaluated the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic using two variables: the performance of the United States in dealing with COVID-19 and the country's international contribution to controlling COVID-19. They gauged different aspects of foreign citizens' evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The former variable reflects how they perceive the United States as handling domestic challenges. It was measured by asking the respondents whether they agreed that the United States did well in dealing with the outbreak of COVID-19. The responses were coded on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating more favorable evaluations of the U.S. response to COVID-19. The latter variable reflects how the respondents perceived the contribution of the United States to the global control of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was measured by asking the respondents whether they agreed that the United States contributed to international cooperation against the pandemic. The responses were coded on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating more favorable evaluations of the United States’ international contribution.

Independent Variables

Beliefs in the superiority of a political system were measured by asking respondents whether they agreed that China/Japan/South Korea's political system had an advantage in dealing with the pandemic. The responses were coded on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated greater levels of beliefs that the country's political system was superior.

Nationalist orientations were measured by adapting Kosterman and Feshbach's nationalism scale.46 Sample items were as follows: generally, the more influence China/Japan/South Korea has on other nations, the better off they are; the first duty of every Chinese/Japanese/Korean is to honor the national history and heritage; and the Chinese/Japanese/Korean nation has the greatest history and culture in the world. The responses were coded on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater levels of nationalist orientations. These items were organized into a single index of citizens' nationalist orientations using principal component analysis.

Drawing on research by Napier and Jost,47 ideology was assessed by asking respondents to rate their political stance on a 7-point scale, from 1 (extremely liberal) to 7 (extremely conservative), with higher scores indicating greater levels of conservativeness.

The national economic situation was measured by asking the respondents to rate their country's economic situation since the COVID-19 outbreak. The responses were coded on a 5-point scale from 1 (bad) to 5 (good), with higher scores indicating a more favorable evaluation of national economic situation. Individual economic status was measured by asking respondents whether their household income decreased due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The responses were coded on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (very much) to 5 (not at all), with higher scores indicating a more favorable evaluation of individual economic status.

We included a variable evaluating participants' perceptions of their home country's COVID-19 response. Respondents were asked whether they agreed that China/Japan/South Korea did well in dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak. Responses were coded on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating more favorable evaluations of one's home country's response to COVID-19.

Control Variables

The demographic variables—age, gender, education, and income—were controlled for in the multivariate regression analyses. Age was measured in years. Education was measured on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (primary school education) to 6 (postgraduate). Gender was coded on a dummy scale, with 0 indicating male and 1 indicating female. Income was measured on a range of 13 brackets in China, one of 14 brackets in Japan, and one of 6 brackets in South Korea. The respondents were asked to select the bracket that best represented their annual household income. The income measure corresponded to the respective countries' income distributions, and income levels differed. Testing each country individually did not result in any problems. If the analysis combines the three countries, the income scale of each country should be standardized beforehand.

Findings

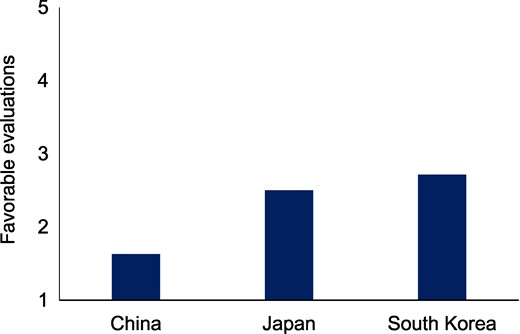

We first compared citizens' evaluations of the U.S. performance in dealing with the outbreak of COVID-19 in the three countries (see fig. 1). On a 5-point scale, all the three countries' scores were below the median value of 3, which indicated that these countries' citizens did not positively evaluate the U.S. performance in dealing with COVID-19. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed a significant effect of country on citizens' evaluation (F(2, 2997) = 372.57; p < .001). The results of post hoc analyses using Scheffe's test indicated a significantly less favorable evaluation among the Chinese citizens (M = 1.633, SD = 0.870) than among the Japanese (M = 2.505, SD = 0.915; p < .001) and South Korean (M = 2.716, SD = 1.030; p < .001) respondents. In addition, the Japanese citizens' evaluation of the U.S. performance in dealing with COVID-19 was also significantly lower than that of their South Korean counterparts (p < .001). The results demonstrate gaps in citizens' evaluation of the U.S. performance in dealing with COVID-19 among these three East Asian countries. Although the three countries' citizens generally did not favorably evaluate the U.S. response, the most favorable evaluation was by the South Korean citizens, and the least favorable evaluation was by the Chinese respondents. Additionally, significant disparities were found in the evaluation of the U.S. performance in dealing with COVID-19 between the Japanese and South Korean citizens.

Evaluation of the U.S. COVID-19 Response in China, Japan, and South Korea

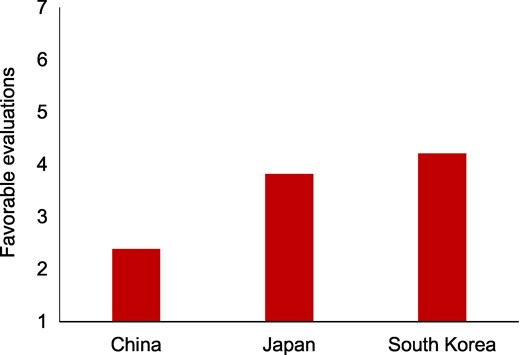

Figure 2 shows the differences in the citizens' evaluation of the U.S. international contribution during the pandemic. On a 7-point scale, the South Korean respondents' score was higher than the median value of 4, whereas the Japanese respondents' score was close to the median. However, the Chinese respondents' score was fairly low. An ANOVA showed a significant effect of country on citizens' evaluation (F(2, 2997) = 430.03; p < .001). The results of post hoc analyses using Scheffe's test indicated a significantly less favorable evaluation among the Chinese citizens (M = 2.386, SD = 1.494) than among the Japanese (M = 3.821, SD = 1.355, p < .001) and South Korean (M = 4.213, SD = 1.544; p < .001) counterparts. In addition, the Japanese citizens' evaluation of the U.S. international contribution during the pandemic was also significantly lower than that of their South Korean counterparts (p < .001).

Evaluation of the U.S. International Contribution during the Pandemic in China, Japan, and South Korea

The results show that the South Korean citizens acknowledged the U.S. international contribution most highly, whereas the least recognition was among the Chinese citizens. In contrast to the Chinese citizens' consistently unfavorable evaluation of the U.S. response to COVID-19, the Japanese and South Korean citizens, to a certain extent, acknowledged the U.S. international contribution to controlling COVID-19.

Table 1 presents the results of the multivariate analysis of the evaluation of the U.S. performance in dealing with COVID-19 and its international contribution during the pandemic. In China, beliefs in the superiority of the country's political system and nationalist orientations were negatively associated with the evaluation of the U.S. performance (b = −.082, p < .05; b = −.112, p < .01) and international contribution (b = −.110, p < .01; b = −.208, p < .001). Favorable evaluations of China's anti–COVID-19 performance was negatively associated with the evaluation of the U.S. response to COVID-19 (b = −.297, p < .001).

| Dependent Variable . | Evaluation of U.S. Performance in Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic, Standardized Coefficient (SE) . | Evaluation of U.S. International Contribution, Standardized Coefficient (SE) . |

|---|---|---|

| China (N = 1,000) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of political system | −0.082 (0.022)* | −0.110 (0.037)** |

| Nationalist orientations | −0.112 (0.013)** | −0.208 (0.022)*** |

| Ideology | 0.052 (0.011) | 0.020 (0.020) |

| National economic situation | −0.008 (0.035) | 0.057 (0.063) |

| Individual economic status | −0.014 (0.037) | −0.018 (0.067) |

| China's COVID-19 response | −0.297 (0.041)*** | |

| R2 | 0.166 | 0.075 |

| Japan (N = 729) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of political system | 0.221 (0.029)*** | 0.345 (0.033)*** |

| Nationalist orientations | −0.045 (0.025) | 0.128 (0.037)*** |

| Ideology | 0.045 (0.018) | 0.049 (0.027) |

| National economic situation | 0.100 (0.040)** | 0.093 (0.058)* |

| Individual economic status | −0.018 (0.042) | 0.005 (0.062) |

| Japan's COVID-19 response | 0.218 (0.042)*** | |

| R2 | 0.219 | 0.209 |

| South Korea (N = 1,000) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of the political system | −0.124 (0.028)** | 0.172 (0.030)*** |

| Nationalist orientations | 0.019 (0.025) | 0.074 (0.037)* |

| Ideology | −0.061 (0.021) | −0.024 (0.032) |

| National economic situation | 0.126 (0.037)** | 0.036 (0.056) |

| Individual economic status | 0.008 (0.038) | 0.051 (0.056) |

| South Korea's COVID-19 response | 0.209 (0.042)*** | |

| R2 | 0.068 | 0.072 |

| Dependent Variable . | Evaluation of U.S. Performance in Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic, Standardized Coefficient (SE) . | Evaluation of U.S. International Contribution, Standardized Coefficient (SE) . |

|---|---|---|

| China (N = 1,000) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of political system | −0.082 (0.022)* | −0.110 (0.037)** |

| Nationalist orientations | −0.112 (0.013)** | −0.208 (0.022)*** |

| Ideology | 0.052 (0.011) | 0.020 (0.020) |

| National economic situation | −0.008 (0.035) | 0.057 (0.063) |

| Individual economic status | −0.014 (0.037) | −0.018 (0.067) |

| China's COVID-19 response | −0.297 (0.041)*** | |

| R2 | 0.166 | 0.075 |

| Japan (N = 729) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of political system | 0.221 (0.029)*** | 0.345 (0.033)*** |

| Nationalist orientations | −0.045 (0.025) | 0.128 (0.037)*** |

| Ideology | 0.045 (0.018) | 0.049 (0.027) |

| National economic situation | 0.100 (0.040)** | 0.093 (0.058)* |

| Individual economic status | −0.018 (0.042) | 0.005 (0.062) |

| Japan's COVID-19 response | 0.218 (0.042)*** | |

| R2 | 0.219 | 0.209 |

| South Korea (N = 1,000) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of the political system | −0.124 (0.028)** | 0.172 (0.030)*** |

| Nationalist orientations | 0.019 (0.025) | 0.074 (0.037)* |

| Ideology | −0.061 (0.021) | −0.024 (0.032) |

| National economic situation | 0.126 (0.037)** | 0.036 (0.056) |

| Individual economic status | 0.008 (0.038) | 0.051 (0.056) |

| South Korea's COVID-19 response | 0.209 (0.042)*** | |

| R2 | 0.068 | 0.072 |

Standardized coefficients were reported. Standard errors in parentheses.

aAge, gender, education, and income were controlled for in the analysis.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, two-tailed test.

| Dependent Variable . | Evaluation of U.S. Performance in Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic, Standardized Coefficient (SE) . | Evaluation of U.S. International Contribution, Standardized Coefficient (SE) . |

|---|---|---|

| China (N = 1,000) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of political system | −0.082 (0.022)* | −0.110 (0.037)** |

| Nationalist orientations | −0.112 (0.013)** | −0.208 (0.022)*** |

| Ideology | 0.052 (0.011) | 0.020 (0.020) |

| National economic situation | −0.008 (0.035) | 0.057 (0.063) |

| Individual economic status | −0.014 (0.037) | −0.018 (0.067) |

| China's COVID-19 response | −0.297 (0.041)*** | |

| R2 | 0.166 | 0.075 |

| Japan (N = 729) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of political system | 0.221 (0.029)*** | 0.345 (0.033)*** |

| Nationalist orientations | −0.045 (0.025) | 0.128 (0.037)*** |

| Ideology | 0.045 (0.018) | 0.049 (0.027) |

| National economic situation | 0.100 (0.040)** | 0.093 (0.058)* |

| Individual economic status | −0.018 (0.042) | 0.005 (0.062) |

| Japan's COVID-19 response | 0.218 (0.042)*** | |

| R2 | 0.219 | 0.209 |

| South Korea (N = 1,000) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of the political system | −0.124 (0.028)** | 0.172 (0.030)*** |

| Nationalist orientations | 0.019 (0.025) | 0.074 (0.037)* |

| Ideology | −0.061 (0.021) | −0.024 (0.032) |

| National economic situation | 0.126 (0.037)** | 0.036 (0.056) |

| Individual economic status | 0.008 (0.038) | 0.051 (0.056) |

| South Korea's COVID-19 response | 0.209 (0.042)*** | |

| R2 | 0.068 | 0.072 |

| Dependent Variable . | Evaluation of U.S. Performance in Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic, Standardized Coefficient (SE) . | Evaluation of U.S. International Contribution, Standardized Coefficient (SE) . |

|---|---|---|

| China (N = 1,000) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of political system | −0.082 (0.022)* | −0.110 (0.037)** |

| Nationalist orientations | −0.112 (0.013)** | −0.208 (0.022)*** |

| Ideology | 0.052 (0.011) | 0.020 (0.020) |

| National economic situation | −0.008 (0.035) | 0.057 (0.063) |

| Individual economic status | −0.014 (0.037) | −0.018 (0.067) |

| China's COVID-19 response | −0.297 (0.041)*** | |

| R2 | 0.166 | 0.075 |

| Japan (N = 729) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of political system | 0.221 (0.029)*** | 0.345 (0.033)*** |

| Nationalist orientations | −0.045 (0.025) | 0.128 (0.037)*** |

| Ideology | 0.045 (0.018) | 0.049 (0.027) |

| National economic situation | 0.100 (0.040)** | 0.093 (0.058)* |

| Individual economic status | −0.018 (0.042) | 0.005 (0.062) |

| Japan's COVID-19 response | 0.218 (0.042)*** | |

| R2 | 0.219 | 0.209 |

| South Korea (N = 1,000) | ||

| Belief in the superiority of the political system | −0.124 (0.028)** | 0.172 (0.030)*** |

| Nationalist orientations | 0.019 (0.025) | 0.074 (0.037)* |

| Ideology | −0.061 (0.021) | −0.024 (0.032) |

| National economic situation | 0.126 (0.037)** | 0.036 (0.056) |

| Individual economic status | 0.008 (0.038) | 0.051 (0.056) |

| South Korea's COVID-19 response | 0.209 (0.042)*** | |

| R2 | 0.068 | 0.072 |

Standardized coefficients were reported. Standard errors in parentheses.

aAge, gender, education, and income were controlled for in the analysis.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, two-tailed test.

In Japan, beliefs in the superiority of the country's political system were positively associated with the evaluation of the U.S. performance (b = .221, p < .001) and international contribution (b = .345, p < .001) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Japanese citizens' nationalist orientations were positively associated with the evaluation of the U.S. international contribution (b = .128, p < .001). The evaluation of Japan's national economic situation was positively associated with the evaluation of the U.S. performance (b = .100, p < .01) and international contribution (b = .093, p < .05). A favorable evaluation of Japan's anti–COVID-19 performance was positively associated with evaluations of the U.S. COVID-19 response (b = .218, p < .001). Unlike the Chinese public, Japanese citizens' favorable evaluations of their own country's performance in handling the COVID-19 pandemic did not generate low evaluations of the U.S. response.

In South Korea, beliefs in the superiority of South Korea's political system were negatively associated with the evaluation of the U.S. performance (b = −.124, p < .01) but positively associated with the evaluation of the U.S. international contribution (b = .172, p < .001). South Korean citizens' nationalist orientations were positively associated with their evaluation of the U.S. international contribution (b = .074, p < .05). Evaluation of the home country's national economic situation was positively associated with the evaluation of the U.S. performance (b = .126, p < .01). A favorable evaluation of South Korea's anti–COVID-19 performance was positively associated with the evaluation of the U.S. response to COVID-19 (b = .209, p < .001). Similar to Japan, South Korean citizens' favorable evaluation of their own country's performance did not generate a poor evaluation of the U.S. response to COVID-19.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study examined evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic by Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean citizens. Overall, these three East Asian countries unfavorably evaluated the U.S. performance in dealing with the outbreak of COVID-19; Chinese citizens offered the least favorable evaluation in the three countries. The U.S. response to COVID-19 was objectively weak or flawed, and this is the possible reason that Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean citizens judged it to be so. However, the actual performance of the United States is not the only reason for unfavorable evaluations of the United States’ COVID-19 responses. Facing the same objective indicators such as deaths and infection cases in the United States, there were significant differences in the evaluations of the United States among Chinese, Japanese, and South Koreans. Chinese people's favorable evaluations of the U.S. response were considerably lower than that of Japanese and South Koreans. Additionally, Japanese and South Korean citizens acknowledged the U.S. contribution to international cooperation in controlling the pandemic, to some extent, whereas Chinese citizens maintained a consistent and negative evaluation of the United States. Although the three countries' citizens unfavorably evaluated the U.S. response to COVID-19, the difference between the Chinese and the other two countries' citizens was significant.

This study applied national ingroup identity and relative comparisons between the United States and one's home country to account for variations among these three East Asian countries. A country's contextual aspect made a difference. Neglecting the contextual influence risks oversimplifying complex correlations, because many relationships observed between relevant variables are contingent on specific contexts. Clarifying these conditions is meaningful for better understanding the causes of people's perceptions of outgroups, which contributes to mitigating and eliminating conflicts in different forms of intergroup relations, such as religion, race, gender, and nationality. In the present study, interstate relations are the context that shapes the relationships between political-psychological factors and the evaluation of the U.S. COVID-19 response. Tensions between China and the United States have heightened, whereas Japan and South Korea are still allies of the United States. The overall climate of interstate relations affects ordinary people's evaluations of other countries.

This study demonstrated that national ingroup identity does not necessarily lead to outgroup discrimination and hatred; group characteristics moderate the association. When intergroup relations are not competitive or conflictive, ingroup identity and outgroup hostility are independent.48 Japanese citizens' ingroup identities based on beliefs in the superiority of their political system in controlling COVID-19 and nationalist orientations positively predicted evaluations of the U.S. performance in handling the COVID-19 outbreak and its international contribution. Similarly, South Korean citizens' beliefs in the superiority of their political system and nationalist orientations were positively associated with their evaluation of the U.S. international contribution during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous studies emphasized how identifying with a national ingroup stimulated hostility toward other countries, and such a relationship was also found in nationalist Japanese people's attitudes toward China and South Korea.49 Interstate relations between the United States and both Japan and South Korea may explain the positive relationship between national ingroup identity and evaluations of the U.S. response to COVID-19.

Certainly, the relationship between ingroup identity and unfavorable evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed in China. This result is consistent with theoretical predictions of ingroup favoritism, which assumes that ingroup identity causes adverse outcomes of the evaluation of outgroups and distribution of benefits to outgroups. The two countries' competitive and conflictive relations explained the negative relationships between the Chinese citizens' beliefs in the superiority of China's political system and nationalist orientations and the evaluations of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese government propagandized the superiority of its one-party system over other countries' political systems.50 Chinese nationalism is related to the history of national humiliation and Western colonization,51 through which the Chinese Communist Party intensifies domestic support by emphasizing China's rise achieved under its leadership. Therefore, Chinese people's national ingroup identities breed outgroup hostility.

The relative comparison between the United States and one's home country also affects evaluations in China, Japan, and South Korea of the U.S. response to COVID-19. According to social comparison theory, the evaluation of the U.S. response to COVID-19 is based on not only its actual performance but also the results of relative comparisons. Even if the actual performance of the United States in controlling infections and deaths was less satisfactory, the worse performance of the home country elicited a relatively favorable evaluation of the U.S. case. However, this hypothesis was not confirmed in Japan or South Korea. In these two countries, high evaluations of the home country's performance during the pandemic did not generate negative evaluations of the U.S. response to COVID-19.

Although Japanese and South Korean citizens shared a similar pattern of relative comparisons between the United States and their home country, the political-psychological mechanism in the positive relationships between evaluation of their home country and that of the United States may differ. Previous studies have found that citizens in Japan and South Korea differed in how they evaluated their own countries' performance in handling the COVID-19 pandemic. Japanese citizens were critical of the government and discontent with their own country's economic recovery and infection control.52 In contrast, South Koreans thought their country had successfully handled COVID-19 and positively evaluated the government's performance.53 One possible explanation is that Japanese citizens who favorably evaluated their own country's performance during the pandemic were less critical and evaluated not only Japan's COVID-19 response highly but also that of the United States. Although South Korean citizens evaluated their own country's performance highly, they were not willing to evaluate the performance of the United States, South Korea's most important ally, as poor. Therefore, South Koreans who positively viewed their national economic recovery and their home country's performance in handling the COVID-19 outbreak also made favorable evaluations of the U.S. response.

A relative comparison between the United States and one's home country yielded a negative relationship in the Chinese sample. Chinese people who favorably viewed their country's performance in handling the COVID-19 outbreak provided more negative evaluations of the U.S. response to COVID-19. In China, mass media are strictly controlled by government authorities and information from mass media tends to serve government interests.54 Since 2012, the Xi administration has strengthened surveillance and censorship of the internet.55 During the pandemic, the Chinese government not only propagandized the “great success” of China's control of infections and deaths but also repeatedly circulated information of the failure of the United States in responding to the COVID-19 outbreak.56 Consequently, the Chinese people's favorable evaluation of their own country's performance during the pandemic was negatively associated with their evaluation of the U.S. response to COVID-19. However, the Chinese people's evaluation of their national economic situation did not significantly predict their evaluation of the U.S. performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is primarily because China's economic downturn has continued, and the Chinese people's relative comparison between the United States and their home country did not negatively affect their evaluation of the United States.

This study had several limitations. First, some variables were not analyzed, because they had not been incorporated into the surveys. For example, expectations for the performance of the United States may affect evaluations. If the expectation of the capacity and performance is high, this would amplify disappointment with the actual performance, which might cause an underevaluation of the U.S. performance. Additionally, this study initially included the variable of access to information in the analysis. However, it is inadequate to rely solely on the frequency of media access as a measure of its influence on respondents. Future research should develop more nuanced and detailed individual-level media-exposure variables to better capture the impact of media on public opinion. Second, this study only examined three East Asian countries, and all independent variables were at the individual level. Admittedly, the country-level factors also matter in public evaluation of a foreign country. Previous studies have found that citizens' evaluations of a country's response to the pandemic differ between individualist and collectivist cultures.57 Future studies should consider expanding the research to a larger sample of countries and examining the effects of country-level factors.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72274121).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this article. Data analyzed in this article were collected by the joint research project “COVID-19 and Relations between State & Society,” which was co-administered by Taisuke Fujita, Hidehiro Yamamoto, Yida Zhai, and Woontaek Lim. The views expressed herein are the author's own.

| Characteristic . | China, % . | Japan, % . | South Korea, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| 18–29 | 35 | 15.4 | 18.8 |

| 30–49 | 30 | 34 | 36.3 |

| 50- | 35 | 50.6 | 44.9 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 50 | 49.5 | 50.7 |

| Female | 50 | 50.5 | 49.3 |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 5.4 | 2.54 | 1.4 |

| Middle school | 14.6 | 29.7 | 22.8 |

| High school | 30 | 13.84 | 18.2 |

| University and above | 50 | 53.92 | 57.6 |

| Characteristic . | China, % . | Japan, % . | South Korea, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| 18–29 | 35 | 15.4 | 18.8 |

| 30–49 | 30 | 34 | 36.3 |

| 50- | 35 | 50.6 | 44.9 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 50 | 49.5 | 50.7 |

| Female | 50 | 50.5 | 49.3 |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 5.4 | 2.54 | 1.4 |

| Middle school | 14.6 | 29.7 | 22.8 |

| High school | 30 | 13.84 | 18.2 |

| University and above | 50 | 53.92 | 57.6 |

| Characteristic . | China, % . | Japan, % . | South Korea, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| 18–29 | 35 | 15.4 | 18.8 |

| 30–49 | 30 | 34 | 36.3 |

| 50- | 35 | 50.6 | 44.9 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 50 | 49.5 | 50.7 |

| Female | 50 | 50.5 | 49.3 |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 5.4 | 2.54 | 1.4 |

| Middle school | 14.6 | 29.7 | 22.8 |

| High school | 30 | 13.84 | 18.2 |

| University and above | 50 | 53.92 | 57.6 |

| Characteristic . | China, % . | Japan, % . | South Korea, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| 18–29 | 35 | 15.4 | 18.8 |

| 30–49 | 30 | 34 | 36.3 |

| 50- | 35 | 50.6 | 44.9 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 50 | 49.5 | 50.7 |

| Female | 50 | 50.5 | 49.3 |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 5.4 | 2.54 | 1.4 |

| Middle school | 14.6 | 29.7 | 22.8 |

| High school | 30 | 13.84 | 18.2 |

| University and above | 50 | 53.92 | 57.6 |

| Variable . | Survey Item . |

|---|---|

| Evaluation of U.S. performance in managing the COVID-19 pandemic | “Do you agree that the [United States] has done a good job in dealing with the coronavirus outbreak?” |

| Evaluation of U.S. international contribution | “Do you agree that the [United States] has contributed to international cooperation to reduce coronavirus cases?” |

| Superiority of political system | “Do you agree that our country's political system has the advantage of dealing with the pandemic?” |

| Nationalist orientation | What do you think about following statements? “Generally, the more influence China/Japan/South Korea has on other nations, the better off they are.” “The first duty of every Chinese/Japanese/Korean citizen is to honor the national history and heritage.” “The Chinese/Japanese/Korean nation has the greatest history and culture in the world.” |

| “It is important for China/Japan/Korea to succeed in international sports events such as the Olympics.” | |

| Ideology | “To indicate one's political position, the concepts of conservative and liberal are used. Suppose that 1 is liberal and 7 is conservative. Where do you think your political position falls?” |

| National economic situation | “Since the COVID-19 outbreak, our national economy has been bad/good?” |

| Individual economic status | “Do you agree that your household income experienced a decrease due to the COVID-19 pandemic?” |

| Home country's COVID-19 response | “Do you agree that China/Japan/South Korea has done a good job in dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak?” |

| Variable . | Survey Item . |

|---|---|

| Evaluation of U.S. performance in managing the COVID-19 pandemic | “Do you agree that the [United States] has done a good job in dealing with the coronavirus outbreak?” |

| Evaluation of U.S. international contribution | “Do you agree that the [United States] has contributed to international cooperation to reduce coronavirus cases?” |

| Superiority of political system | “Do you agree that our country's political system has the advantage of dealing with the pandemic?” |

| Nationalist orientation | What do you think about following statements? “Generally, the more influence China/Japan/South Korea has on other nations, the better off they are.” “The first duty of every Chinese/Japanese/Korean citizen is to honor the national history and heritage.” “The Chinese/Japanese/Korean nation has the greatest history and culture in the world.” |

| “It is important for China/Japan/Korea to succeed in international sports events such as the Olympics.” | |

| Ideology | “To indicate one's political position, the concepts of conservative and liberal are used. Suppose that 1 is liberal and 7 is conservative. Where do you think your political position falls?” |

| National economic situation | “Since the COVID-19 outbreak, our national economy has been bad/good?” |

| Individual economic status | “Do you agree that your household income experienced a decrease due to the COVID-19 pandemic?” |

| Home country's COVID-19 response | “Do you agree that China/Japan/South Korea has done a good job in dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak?” |

| Variable . | Survey Item . |

|---|---|

| Evaluation of U.S. performance in managing the COVID-19 pandemic | “Do you agree that the [United States] has done a good job in dealing with the coronavirus outbreak?” |

| Evaluation of U.S. international contribution | “Do you agree that the [United States] has contributed to international cooperation to reduce coronavirus cases?” |

| Superiority of political system | “Do you agree that our country's political system has the advantage of dealing with the pandemic?” |

| Nationalist orientation | What do you think about following statements? “Generally, the more influence China/Japan/South Korea has on other nations, the better off they are.” “The first duty of every Chinese/Japanese/Korean citizen is to honor the national history and heritage.” “The Chinese/Japanese/Korean nation has the greatest history and culture in the world.” |

| “It is important for China/Japan/Korea to succeed in international sports events such as the Olympics.” | |

| Ideology | “To indicate one's political position, the concepts of conservative and liberal are used. Suppose that 1 is liberal and 7 is conservative. Where do you think your political position falls?” |

| National economic situation | “Since the COVID-19 outbreak, our national economy has been bad/good?” |

| Individual economic status | “Do you agree that your household income experienced a decrease due to the COVID-19 pandemic?” |

| Home country's COVID-19 response | “Do you agree that China/Japan/South Korea has done a good job in dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak?” |

| Variable . | Survey Item . |

|---|---|

| Evaluation of U.S. performance in managing the COVID-19 pandemic | “Do you agree that the [United States] has done a good job in dealing with the coronavirus outbreak?” |

| Evaluation of U.S. international contribution | “Do you agree that the [United States] has contributed to international cooperation to reduce coronavirus cases?” |

| Superiority of political system | “Do you agree that our country's political system has the advantage of dealing with the pandemic?” |

| Nationalist orientation | What do you think about following statements? “Generally, the more influence China/Japan/South Korea has on other nations, the better off they are.” “The first duty of every Chinese/Japanese/Korean citizen is to honor the national history and heritage.” “The Chinese/Japanese/Korean nation has the greatest history and culture in the world.” |

| “It is important for China/Japan/Korea to succeed in international sports events such as the Olympics.” | |

| Ideology | “To indicate one's political position, the concepts of conservative and liberal are used. Suppose that 1 is liberal and 7 is conservative. Where do you think your political position falls?” |

| National economic situation | “Since the COVID-19 outbreak, our national economy has been bad/good?” |

| Individual economic status | “Do you agree that your household income experienced a decrease due to the COVID-19 pandemic?” |

| Home country's COVID-19 response | “Do you agree that China/Japan/South Korea has done a good job in dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak?” |

Footnotes

Katia Hetter, “It’s Been Three Years since the First Covid-19 Case in the United States. What Have We Learned and What More Do We Need to Understand?” CNN, 26 January 2023. Accessed 1 July 2023. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/01/26/health/covid-variant-vaccine-omicron-health-wellness/index.html

The World Health Organization, WHO COVID-19 dashboard. Accessed 2023. https://covid19.who.int/

Mathew Alexander, Lynn Unruh, Andriy Koval, and William Belanger, “United States Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic, January–November 2020,” Health Economics, Policy and Law 17, no. 1 (January 2022): 62–75, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133121000116; Armin Nowroozpoor, Esther K. Choo, and Jeremy S. Faust, “Why the United States Failed to Contain COVID-19,” Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open 1, no. 4 (August 2020): 686–88, https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12155.

Eli Y. Adashi and I. Glenn Cohen, “Failing Grade: The Pandemic Legacy of HHS,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 64, no. 1 (January 2023): 142–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.07.008.

Tanya Lewis, “How the U.S. Pandemic Response Went Wrong—and What Went Right—during a Year of COVID,” Scientific American, 11 March 2021. Accessed 10 May 2023. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-the-u-s-pandemic-response-went-wrong-and-what-went-right-during-a-year-of-covid/

Associated Press-NORC, “AP-NORC Poll: Support for Donald Trump, Federal Government Split along Partisan Lines,” University of Chicago News, 1 April 2020. Accessed 10 May 2023. https://news.uchicago.edu/story/how-do-americans-view-governments-handling-coronavirus-outbreak; Pew Research Center, “Increasing Public Criticism, Confusion over COVID-19 Response in U.S.,” 9 February 2022. Accessed 10 May 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/02/09/increasing-public-criticism-confusion-over-covid-19-response-in-u-s/; Adrianna Rodriguez, “Many Americans Don’t Trust Their Public Health System during COVID-19 Pandemic, Survey Shows,” USA Today, 13 May 2021. Accessed 10 May 2023. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2021/05/13/cdc-fda-american-opinion-public-health-system-suffers-amid-covid/5054439001/

Tanja Passow, Rolf Fehlmann, and Heike Grahlow, “Country Reputation—From Measurement to Management: The Case of Liechtenstein,” Corporate Reputation Review 7, no. 4 (January 2005): 309–26, https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540229; Jian Wang, “Managing National Reputation and International Relations in the Global Era: Public Diplomacy Revisited,” Public Relations Review 32, no. 2 (June 2006): 91–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2005.12.001; Sung-Un Yang, Hochang Shin, Jong-Hyuk Lee, and Brenda Wrigley, “Country Reputation in Multidimensions: Predictors, Effects, and Communication Channels,” Journal of Public Relations 20, no. 4 (December 2008): 421–40, https://doi.org/10.1080/10627260802153579.

Min-hua Huang and Yun-han Chu, “The Sway of Geopolitics, Economic Interdependence and Cultural Identity: Why Are Some Asians More Favorable toward China’s Rise than Others?” Journal of Contemporary China 24, no. 93 (May 2015): 421–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2014.953842; Mathew Linley, James Reilly, and Benjamin E. Goldsmith, “Who’s Afraid of the Dragon? Asian Mass Publics’ Perceptions of China’s Influence,” Japanese Journal of Political Science 13, no. 4 (December 2012): 501–23, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109912000242.

Yu Xie, Feng Yang, Junming Huang, Yuchen He, Yi Zhou, Yue Qian, Weicheng Cai, and Jie Zhou, “Declining Chinese Attitudes toward the United States amid COVID-19,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, no. 21 (March 2024): e2322920121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2322920121.

Yida Zhai, “Living with the Global Hegemon: How the Chinese Public Views the United States,” Asian Perspective 48, no. 42 (November 2024): 549–73, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/944261.

Yida Zhai, “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Popular Confidence in Democracy: Evidence from China, Japan, and South Korea,” Democratization. Published ahead of print, 13 June 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2024.2355245.

Henri Tajfel, “Social Identity and Intergroup Behavior,” Social Science Information 13, no. 2 (April 1974): 65–93, https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847401300204; Henri Tajfel and John C. Turner, “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict,” in ed. Stephen Worchel and William G. Austin, Psychology of Intergroup Relations (Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall, 1986), 2–24.

Min-gyu Lee and Yufan Hao, “China’s Unsuccessful Charm Offensive: How South Koreans Have Viewed the Rise of China over the Past Decade,” Journal of Contemporary China 27, no. 114 (November 2018): 867–86, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1488103; Shigeto Sonoda, “Asian Views of China in the Age of China’s Rise: Interpreting the Results of Pew Survey and Asian Student Survey in Chronological and Comparative Perspectives, 2002–2019,” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 10, no. 2 (June 2021): 262–79, https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2021.1943116; Yida Zhai, “The Gap in Viewing China’s Rise between Chinese Youth and Their Asian Counterparts,” Journal of Contemporary China 27, no. 114 (November 2018): 848–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1488102; Yida Zhai, “A Peaceful Prospect or a Threat to Global Order: How Asian Youth View a Rising China,” International Studies Review 21, no. 1 (March 2019): 38–56, https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viy010.

Kyle Ferrier, “The United States and South Korea in the Indo-Pacific after COVID-19,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs 3, no. 3 (September 2020): 97–111; Stephanie A. Weston, “Returning to a New Normal in U.S.-Japan Relations,” Fukuoka University Review of Law 65, no. 4 (March 2021): 629–66, https://fukuoka-u.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/5231.

Tajfel, “Social Identity and Intergroup Behavior”; Henri Tajfel, “Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations,” Annual Review of Psychology 33 (February 1982): 1–39, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245; Tajfel and Turner, “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.”

Naomi Ellemers and S. Alexander Haslam, “Social Identity Theory,” in Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, ed. Paul A. M. van Lange, Arie W. Kruglanski, and E. Tory Higgins (Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications Ltd., 2012), 379–99; Michael A. Hogg, “From Uncertainty to Extremism: Social Categorization and Identity Processes,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 23, no. 5 (October 2014): 338–42, https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414540168; Geoffrey J. Leonardelli and Soo Min Toh, “Perceiving Expatriate Coworkers as Foreigners Encourages Aid: Social Categorization and Procedural Justice Together Improve Intergroup Cooperation and Dual Identity,” Psychological Science 22, no. 1 (January 2011): 110–17, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610391913.

Tajfel, “Social Identity and Intergroup Behavior”; Tajfel and Turner, “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.”

Charles Efferson, Rafael Lalive, and Ernst Fehr, “The Coevolution of Cultural Groups and Ingroup Favoritism,” Science 321, no. 5897 (September 2008): 1844–49, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1155805; Angelo Romano, Daniel Balliet, Toshio Yamagishi, and James H. Liu, “Parochial Trust and Cooperation across 17 Societies,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 48 (November 2017): 12702–707, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1712921114.

Laura King, “Will ‘Vaccine Nationalism’ Rear Its Head? Britain May be a Test Case,” Los Angeles Times, 2, 2 December 2020. Accessed 19 August 2023. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-12-02/britain-shows-pride-in-experience-programs-as-it-approves-a-covid-19-vaccine; Gideon Rachman, “Nationalism is a Side Effect of the Coronavirus,” Financial Times, March 23, 2020. Accessed 19 August 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/644fd920-6cea-11ea-9bca-bf503995cd6f; Eric Taylor Woods, Robert Schertzer, Liah Greenfeld, Chris Hughes, and Cynthia Miller-Idriss, “COVID-19, Nationalism, and the Politics of Crisis: A Scholarly Exchange,” Nations and Nationalism 26, no. 4 (October 2020): 807–25, https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12644.

Patrick Francois, Thomas Fujiwara, and Tanguy van Ypersele, “The Origins of Human Prosociality: Cultural Group Selection in the Workplace and the Laboratory,” Science Advances 4, no. 9 (September 2018): article eaat2201. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat2201; Guanghua Han and Yida Zhai, “The Association between Food Insecurity and Social Capital under the Lockdowns in COVID-Hit Shanghai,” Urban Studies 61, no. 1 (January 2024): 130–47, https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231172403; Martin Lang, Dimitris Xygalatas, Christopher M. Kavanagh, Natalia A. Craciun Boccardi, Jamin Halberstadt, Chris Jackson, Mercedes Martínez et al., “Outgroup Threat and the Emergence of Cohesive Groups: A Cross-Cultural Examination,” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 25, no. 7 (October 2022): 1739–59, https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211016961.

Maxwell Burton-Chellew, Adin Ross-Gillespie, and Stuart A. West, “Cooperation in Humans: Competition between Groups and Proximate Emotions,” Evolution and Human Behavior 31, no. 2 (March 2010): 104–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.07.005; Daniel M. T. Fessler and Kevin J. Haley, “The Strategy of Affect: Emotions in Human Cooperation,” in Genetic and Cultural Evolution of Cooperation, ed. Peter Hammerstein (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 7–36.

Yida Zhai, “Exclusionist Reactions during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean Citizens’ Support for Border Restriction,” Social Science Quarterly 105, no. 7 (December 2024): 2208–2223, https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.13465.

Ken’ichi Ikeda and Masaru Kohno, “Japanese Attitudes and Values toward Democracy,” in How East Asians View Democracy, ed. Yun-han Chu, Larry Diamond, Andrew J. Nathan, and Doh Chull Shin (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 161–86; Doh Chull Shin and Jason Wells, “Is Democracy the Only Game in Town?” Journal of Democracy 16, no. 2 (April 2005): 88–101, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2005.0036.

Yida Zhai, “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Popular Confidence in Democracy: Evidence from China, Japan, and South Korea.” Democratization. Published ahead of print 13 June 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2024.2355245; Yida Zhai, Li Ying Chong, Yunzhe Liu, Shuting Yang, and Changfa Song, “Social Dominance Orientation, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, and Political Attitudes toward Governmental Performance during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 22, no. 1 (April 2022): 150–67, https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12296.

Yida Zhai, Yizhen Lu, and Qidi Wu, “Patriotism, Nationalism, and Evaluations of the Government’s Handling of the Coronavirus Crisis,” Frontiers in Psychology 14 (February 2023): 1016435, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1016435.

Jon E Fox. and Cynthia Miller-Idriss, “Everyday Nationhood,” Ethnicities 8, no. 4 (December 2008): 536–63, https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796808088925; Andrew Thompson, “Nations, National Identities and Human Agency: Putting People Back into Nations,” Sociological Review 49, no. 1 (February 2001): 18–32, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.00242.

Gerard Kleinpenning and Louk Hagendoorn. “Forms of Racism and the Cumulative Dimension of Ethnic Attitudes,” Social Psychology Quarterly 56, no. 1 (March 1993): 21–36, https://doi.org/10.2307/2786643; Rick Kosterman and Seymour Feshbach, “Toward a Measure of Patriotic and Nationalistic Attitudes,” Political Psychology 10, no. 2 (June 1989): 257–74, https://doi.org/10.2307/3791647.

Woods et al., “COVID-19, Nationalism, and the Politics of Crisis: A Scholarly Exchange.”

Florian Bieber, “Global Nationalism in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Nationalities Papers 50, no. 1 (January 2022): 13–25, https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.35; John Hutchinson, Nationalism and War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

King, “Will ‘Vaccine Nationalism’ Rear Its Head?”; Rachman, “Nationalism is a Side Effect of the Coronavirus.”

Donald Campbell, “Ethnocentric and Other Altruistic Motives,” in Nebraska Symposium on Motivation Vol. 13, ed. David Levine (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 283–311; Paul Collier, Anke Hoeffler, and Dominic Rohner, “Beyond Greed and Grievance: Feasibility and Civil War,” Oxford Economic Papers 61, no. 1 (January 2009): 1–27, https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpn029; Muzafer Sherif and Carolyn W. Sherif, Groups in Harmony and Tension (New York: Harper, 1953).

Michael Billig and Henri Tajfel, “Social Categorization and Similarity in Intergroup Behaviour,” European Journal of Social Psychology 3, no. 1 (January 1973): 27–52, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420030103; Henri Tajfel, “Experiments in Intergroup Discrimination,” Scientific American 223, no. 5 (November 1970): 96–102, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24927662.

Luca Caricati, “Perceived Threat Mediates the Relationship between National Identification and Support for Immigrant Exclusion: A Cross-National Test of Intergroup Threat Theory,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 66 (September 2018): 41–51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.06.005; Cody T. Havard, Patrick Ferrucci, and Timothy D. Ryan, “Does Messaging Matter? Investigating the Influence of Media Headlines on Perceptions and Attitudes of the In-Group and Out-Group,” Journal of Marketing Communications 27, no. 1 (January 2021): 20–30, https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2019.1620838; Blake M. Riek, Eric W. Mania, and Samuel L. Gaertner, “Intergroup Threat and Outgroup Attitudes: A Meta-Analytic Review,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 10, no. 4 (November 2006): 336–53, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4.

Woods et al., “COVID-19, Nationalism, and the Politics of Crisis: A Scholarly Exchange.”

“Coronavirus: Mike Pompeo Says ‘Significant Evidence’ COVID-19 Came from Wuhan Lab,” Sky News, 4 May 2020. Accessed 10 July 2023. https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-mike-pompeo-says-significant-evidence-covid-19-came-from-wuhan-lab-11982686; Katie Rogers, Lara Jakes, and Ana Swanson, “Trump Defends Using ‘Chinese Virus’ Label, Ignoring Growing Criticism,” New York Times, 18 March 2020. Accessed 10 July 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/us/politics/china-virus.html.

Peter Hays Gries and Matthew Sanders, “How Socialization Shapes Chinese Views of America and the World,” Japanese Journal of Political Science 17, no. 1 (March 2016): 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109915000365; Elina Sinkkonen and Marko Elovainio, “Chinese Perceptions of Threats from the United States and Japan,” Political Psychology 41, no. 2 (April 2020): 265–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12630.

Hart Blanton, Jennifer Crocker, and Dale T. Miller, “The Effects of In-Group Versus Out-Group Social Comparison on Self-Esteem in the Context of a Negative Stereotype,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 36, no. 5 (September 2000): 519–30, https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2000.1425; Marilynn B. Brewer and Joseph G. Weber, “Self-Evaluation Effects of Interpersonal Versus Intergroup Social Comparison,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 66, no. 2 (February 1994): 268–75, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.2.268; Susanne Bruckmüller and Andrea E. Abele, “Comparison Focus in Intergroup Comparisons: Who We Compare to Whom Influences Who We See as Powerful and Agentic,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36, no. 10 (October 2010): 1424–35, https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210383581.

Michael A. Hogg, “Social Identity and Social Comparison,” in Handbook of Social Comparison: Theory and Research, ed. Jerry Suls and Ladd Wheeler (Boston: Springer, 2000), 401–21.

Han and Zhai, “The Association between Food Insecurity and Social Capital Under the Lockdowns in COVID-Hit Shanghai.”

Ji-Ming Chen and Yi-Qing Chen, “China Can Prepare to End Its Zero-COVID Policy,” Nature Medicine 28, no. 6 (June 2022): 1104–105, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01794-3; Xinxin Zhang, Wenhong Zhang, and Saijuan Chen, “Shanghai’s Life-Saving Efforts against the Current Omicron Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” The Lancet 399, no. 10340 (May 2022): 2011–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00838-8.

Yan Yi, “The Unequal Others: Mediation of Distant COVID-19 Suffering in Chinese Television News,” Chinese Journal of Communication 16, no. 3 (September 2023): 285–302, https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2023.2196086; Hong Zhang, “America’s Fight against the Pandemic: From Failure to Failure,” People’s Daily, 15 February 2022. Accessed 18 May 2023. http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0215/c1003-32351982.html

Kerry Liu, “China’s Dynamic Covid-Zero Policy and the Chinese Economy: A Preliminary Analysis,” International Review of Applied Economics 36, no. 5–6 (November 2022): 815–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2022.2138836; Dali L. Yang, “China’s Zero-COVID Campaign and the Body Politic,” Current History 121, no. 836 (September 2022): 203–10, https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2022.121.836.203.

Haiqian Chen, Leiyu Shi, Yuyao Zhang, Xiaohan Wang, and Gang Sun, “A Cross-Country Core Strategy Comparison in China, Japan, Singapore and South Korea during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic,” Globalization and Health 17 (February 2021): 22, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00672-w; Sungjoong Kim, Sung Kyum Cho, and Sarah Prusoff LoCascio, “The Role of Media Use and Emotions in Risk Perception and Preventive Behaviors Related to COVID-19 in South Korea,” Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research 8, no. 3 (August 2020): 297–323, https://doi.org/10.15206/ajpor.2020.8.3.297.

Hideaki Shiroyama, “Japan’s Response to the COVID-19,” in Good Public Governance in a Global Pandemic, ed. Paul Joyce, Fabienne Maron, and Purshottama Sivanarain Reddy (Brussels: The International Institute of Administrative Sciences, 2020), 195–204.

Data analyzed in this article were collected by the joint research project “COVID-19 and Relations between State & Society,” which was co-administered by Taisuke Fujita, Hidehiro Yamamoto, Yida Zhai, and Woontaek Lim. The views expressed herein are the author’s own.

Kosterman and Feshbach, “Toward a Measure of Patriotic and Nationalistic Attitudes.”

Jaime L. Napier and John T. Jost, “Why Are Conservatives Happier than Liberals?” Psychological Science 19, no. 6 (June 2008): 565–72, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02124.x.

Marilynn B. Brewer, “The Psychology of Prejudice: Ingroup Love or Outgroup Hate?” Journal of Social Issues 55, no. 3 (September 1999): 429–44, https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00126.

Koichi Nakano, “Contemporary Political Dynamics of Japanese Nationalism,” The Asia-Pacific Journal 14, no. 20 (October 2016): article 4965; Hironori Sasada, “Youth and Nationalism in Japan,” The SAIS Review of International Affairs 26, no. 2 (October 2006): 109–22, https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2006.0044.

Yang, “China’s Zero-COVID Campaign and the Body Politic”; Yida Zhai, “The Politics of COVID-19: The Political Logic of China’s Zero-COVID Policy,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 53, no. 5 (September 2023): 869–86, https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2023.2194322.

John Agnew, “Looking Back to Look Forward: Chinese Geopolitical Narratives and China’s Past,” Eurasian Geography and Economics 53, no. 3 (May 2012): 301–14, https://doi.org/10.2747/1539-7216.53.3.301; Peter Hays Gries, China’s New Nationalism: Pride, Politics, and Diplomacy (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2004); Zheng Wang, Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014).

Ken’ichi Ikeda, Contemporary Japanese Politics and Anxiety over Governance (London: Routledge, 2022).

Sijeong Lim and Aseem Prakash, “Pandemics and Citizen Perceptions about Their Country: Did COVID-19 Increase National Pride in South Korea?” Nations and Nationalism 27, no. 3 (July 2021): 623–37, https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12749.

Steve Guo and Dan Wang, “News Production and Construal Level: A Comparative Analysis of the Press Coverage of China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Chinese Journal of Communication 14, no. 2 (June 2021): 211–30, https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2020.1816556; Guobin Yang, “Contesting Food Safety in the Chinese Media: Between Hegemony and Counter-Hegemony,” The China Quarterly 214 (2013): 337–55, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741013000386; Ying Zhu, Two Billion Eyes: The Story of China Central Television (New York: The New Press, 2014).

Rogier Creemers, “Cyber China: Upgrading Propaganda, Public Opinion Work and Social Management for the Twenty-First Century,” Journal of Contemporary China 26, no. 103 (January 2017): 85–100, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2016.1206281; Qiang Xiao, “The Road to Digital Unfreedom: President Xi’s Surveillance State,” Journal of Democracy 30, no. 1 (January 2019): 53–67, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0004.

Cui Zhang Meadows, Lu Tang, and Wenxue Zou, “Managing Government Legitimacy during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China: A Semantic Network Analysis of State-Run Media Sina Weibo Posts,” Chinese Journal of Communication 15, no. 2 (June 2022): 156–81, https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2021.2016876; Yi, “The Unequal Others: Mediation of Distant COVID-19 Suffering in Chinese Television News.”

Yasheng Chen and Mohammad Islam Biswas, “Impact of National Culture on the Severity of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Current Psychology 42, no. 18 (June 2023): 15813–26, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02906-5; Jackson G. Lu, Peter Jin, and Alexander S. English, “Collectivism Predicts Mask Use during COVID-19,” The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 23 (May 2021): e2021793118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2021793118; Zhuo Wang, Yi Li, Ruiqing Xu, and Haoting Yang, “How Culture Orientation Influences the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Analysis,” Frontiers in Psychology 13 (September 2022): 899730, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.899730.

Author notes

Yida Zhai is an associate professor of Political Science at the University of Tsukuba, Japan. He studies political psychology, political sociology, and Asian comparative politics. His research has appeared in Contemporary Politics, Journal of Public Policy, and other Chinese and Japanese journals.

Conflict of Interest: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest.