-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shi-Cheng Zou, Mao-Gen Zhuo, Farhat Abbas, Gui-Bing Hu, Hui-Cong Wang, Xu-Ming Huang, Transcription factor LcNAC002 coregulates chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis in litchi, Plant Physiology, Volume 192, Issue 3, July 2023, Pages 1913–1927, https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiad118

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis, which often occur almost synchronously during fruit ripening, are crucial for vibrant coloration of fruits. However, the interlink point between their regulatory pathways remains largely unknown. Here, 2 litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) cultivars with distinctively different coloration patterns during ripening, i.e. slow-reddening/stay-green “Feizixiao” (FZX) vs rapid-reddening/degreening “Nuomici” (NMC), were selected as the materials to study the key factors determining coloration. Litchi chinensis STAY-GREEN (LcSGR) was confirmed as the critical gene in pericarp chlorophyll loss and chloroplast breakdown during fruit ripening, as LcSGR directly interacted with pheophorbide a oxygenase (PAO), a key enzyme in chlorophyll degradation via the PAO pathway. Litchi chinensis no apical meristem (NAM), Arabidopsis transcription activation factor 1/2, and cup-shaped cotyledon 2 (LcNAC002) was identified as a positive regulator in the coloration of litchi pericarp. The expression of LcNAC002 was significantly higher in NMC than in FZX. Virus-induced gene silencing of LcNAC002 significantly decreased the expression of LcSGR as well as L. chinensis MYELOBLASTOSIS1 (LcMYB1), and inhibited chlorophyll loss and anthocyanin accumulation. A dual-luciferase reporter assay revealed that LcNAC002 significantly activates the expression of both LcSGR and LcMYB1. Furthermore, yeast-one-hybrid and electrophoretic mobility shift assay results showed that LcNAC002 directly binds to the promoters of LcSGR and LcMYB1. These findings suggest that LcNAC002 is an important ripening-related transcription factor that interlinks chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis by coactivating the expression of both LcSGR and LcMYB1.

Introduction

The scale and intensity of coloration during fruit ripening is one of the most important determinants of the marketability of fruits. Development of a vibrant color in fruits involves loss of the background color (reduction in chlorophylls) and development of the surface color (accumulation of anthocyanins or carotenoids). In general, fruits of red or orange color are more often selected for domestication, not only due to their attractive appearance, but also because of the substantial health benefits of anthocyanins and carotenoids (Bohn et al. 2021; Mohanmmad et al. 2021). However, the stay-green phenotype or low anthocyanin or carotenoid accumulation of numerous fruit varieties has a substantial impact on consumer acceptance.

Studies on degreening due to chlorophyll degradation and its effect on fruit skin coloration have been carried out in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa, Duch.) (Matínez et al. 2001), apple (Malus domestica) (Han et al. 2018; Wei et al. 2021), lemon (Citrus limon) (Shemer et al. 2008), banana (Musa spp.) (Wu et al. 2019), tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) (Luo et al. 2013), and litchi (Litchi chinensis) (Wang et al. 2005). The chlorophyll degradation pathway consisting of several enzymes that convert chlorophyll to nonfluorescent chlorophyll catabolites is well understood (Hörtensteiner 2013). STAY-GREEN (SGR) proteins have been identified as the key regulator of chlorophyll degradation in multiple species, including rice (Oryza sativa) (Park et al. 2007), Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) (Sakuraba et al. 2012), tomato (Luo et al. 2013), pepper (Capsicum annuum) (Barry et al. 2008), alfalfa (Medicago truncatula) (Zhou et al. 2011), banana (Wu et al. 2019), and orange (Citrus sinensis) (Zhu et al. 2021). SGRs accelerate chlorophyll degradation via recruiting chlorophyll catabolizing enzymes (Park et al. 2007; Sakuraba et al. 2012) and were recently identified as Mg-dechelatase (Matsuda et al. 2016; Shimoda et al. 2016). Nevertheless, the regulatory pathways of SGRs remain poorly understood.

Anthocyanins are a group of pigments produced from the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway and are responsible for the generation of red, blue, and purple colors in plants, which enhance the esthetic value of fruits. The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway that leads to anthocyanin accumulation is well comprehended. The enzymes and structural genes involved in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway and the subsequent flavonoid transportation have been characterized in fruits (Jaakola 2013). The complex of DNA-binding R2R3 MYB transcription factor (TF), MYC-like basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH), and WD40-repeat proteins is one of the most well-known regulators of anthocyanin biosynthesis (Allan et al. 2008). The MYB proteins are considered to be the key component in the allocation of specific gene expression patterns. MdMYBA/1/10 in apple, PcMYB10 in pear (Pyrus communis), VvMYBA in grape (Vitis vinifera), MrMYB1 in bayberry (Myrica rubra), and LcYMB1/5 in litchi are examples of MYBs that are positive regulators, which promote the expression of the structural genes involved in flavonoid pathway (Huang et al. 2013; Jaakola 2013; Lai et al. 2014). However, the signaling network that drives the upregulation of these MYBs and anthocyanin biosynthesis in response to fruit ripening remains unknown.

Plant growth and development are controlled by a variety of TFs, which modulate the expression of target genes by binding to their promoters or interacting with other proteins (Zafar et al. 2021). The NAC (no apical meristem [NAM], Arabidopsis transcription activation factor 1/2 [ATAF1/2], and cup-shaped cotyledon 2 [CUC2]) TF family is one of the largest TF superfamilies and has been extensively studied because of its highly conserved N-terminal NAC domain and diverse C-terminal domains (Shinozaki et al. 2018). NAC TFs have been shown to be involved in the regulation of a variety of ripening-related processes in diverse species including tomato (Kumar et al. 2018), apple (Migicovsky et al. 2021), strawberry (Martín-Pizarro et al. 2021), banana (Tak et al. 2018), peach (Prunus persica) (Cao et al. 2021), litchi (Jiang et al. 2019), and ponkan (Citrus reticulata) (Li et al. 2017). Recent evidence emphasizes the importance of NAC in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis. In apple, MdNAC52 interacts with the promoters of MdMYB9 and MdMYB11 to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis (Sun et al. 2019). BLOOD (BL) and MdNAC42 regulate anthocyanin pigmentation in red-fleshed peach and apple by interacting with PpMYB10.1 and MdMYB10, respectively, to trigger the expression of flavonoid pathway genes (Zhou et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2020). In litchi, LcNAC13 enhances anthocyanin accumulation by repressing the expression of LcR1MYB1, a negative regulatory protein in anthocyanin biosynthesis (Jiang et al. 2019). NACs have been found to be associated with chlorophyll degradation during leaf senescence and under stress in Arabidopsis and banana (Tak et al. 2018). However, the role of NACs in fruit chlorophyll degradation is unclear. In most fruits, degreening and pigmentation occur almost simultaneously during ripening. Very likely, there is a common trigger that initiates both events. It is fascinating to unravel how these 2 biological changes are coregulated. Fruit ripening is a uniquely complex network of biological pathways, coordination of which is dependent on phytohormone signaling, especially ethylene and abscisic acid (ABA) signaling (Fenn and Giovannoni 2021). NACs have been implicated in the biosynthesis and/or signaling of ethylene and ABA, in addition to targeting MYB TFs (Shan et al. 2012; An et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2020; Fu et al. 2021; Martín-Pizarro et al. 2021). Therefore, NACs may coregulate chlorophyll loss and anthocyanin accumulation during fruit ripening through their roles in phytohormone biosynthesis and signaling.

The litchi pericarp shows remarkable variation in coloration pattern among cultivars, which can be classified into 3 coloration types, namely non-red (stay-green), unevenly red, and fully red types, based on changes in concentrations of chlorophylls and anthocyanins in the pericarp at maturity (Wei et al. 2011). Litchi coloration phenotype is characterized by a combination of chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin accumulation. The key structural genes and TFs in anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway have been well characterized in litchi. LcMYB1 regulates the expression of late anthocyanin biosynthesis structural genes, primarily L. chinensis DIHYDROFLAVONOL REDUCTASE (LcDFR) and L. chinesis UDP-FLAVONOID GLUCOSYL TRANSFERASE (LcUFGT1), by interacting with L. chinensis BASIC HELIX–LOOP–HELIX1/3 (LcbHLH1/3) (Lai et al. 2014, 2016). The expression patterns of LcSGR during litchi ripening and the bleaching phenotype of LcSGR overexpression in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves imply that LcSGR plays an important role in chlorophyll degradation (Lai et al. 2015). The litchi genome contains 3 SGR genes, and their roles need to be further verified. The cultivars with contrasting coloration patterns provide ideal materials to explore mechanisms in regulation of chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin accumulation. Herein, we revealed that LcSGR regulates chlorophyll degradation in the litchi pericarp via direct protein–protein interaction with pheophorbide-a oxygenase (LcPAO), and that silencing LcSGR results in a stay-green and delayed pigmentation phenotype. Furthermore, we functionally characterized LcNAC002, which coregulates the chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis in litchi pericarp by upregulating the expression of both LcSGR and LcMYB1 through directly binding to their promoters.

Results

Mining the key genes regulating chlorophyll degradation in litchi

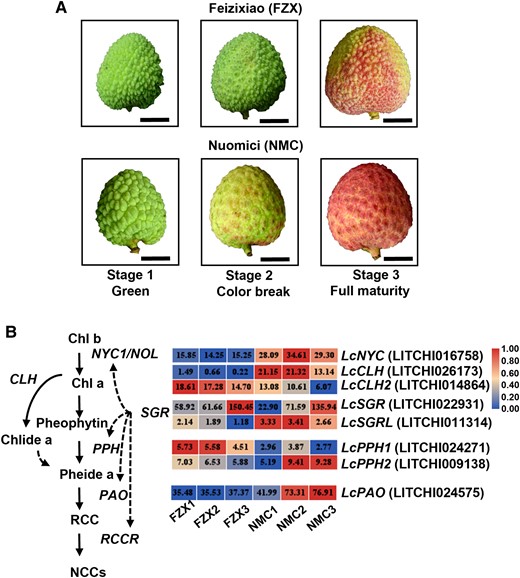

In contrast to the degreening and well-colored cultivar Nuomici (NMC), Feizixiao (FZX) exhibits a distinct stay-green and poor pigmentation phenotype (Fig. 1A). RNA-seq analyses were performed on FZX and NMC pericarp at 3 different developmental stages (Fig. 1A). The RNA-seq data have been submitted to the NCBI database (PRJNA905662). A total of 9,095 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between FZX and NMC at all the 3 stages were found in RNA-seq data, and kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes pathway enrichment analysis was carried out (Supplemental Fig. S1). Then, we concentrated on the identified DEGs involved in the chlorophyll degradation pathway (Fig. 1B). The degreening cultivar NMC had significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) higher transcription levels of LcSGRs (LITCHI022931 and LITCHI1011314), LcNYC (NON YELLOW COLORING) (LITCHI016758), LcCLH (CHLOROPHYLLASE) (LICHI026173), LcPPH2 (PHEOPHYTINASE2) (LITCHI009138), and LcPAO (LITCHI024575) than FZX, while the transcript of LcPPH1 (LITCHI024271), was lower in NMC than in FZX. Pheophytinase (PPH) specifically dephytylates pheophytin, an Mg-free chlorophyll (Sakuraba et al. 2012). The expression of LcPPH2 was paralleled with the loss of chlorophylls, and thus it was targeted as a key chlorophyll degradation gene in the further assays.

Coloration patterns of FZX and NMC and DEGs involved in chlorophyll degradation between the 2 cultivars. A) Images of FXZ and NMC fruits at various stages of coloration. Images were digitally extracted for comparison. Bars = 1 cm. B) DEGs involved in chlorophyll degradation identified in RNA-seq data in litchi pericarp. Chl, chlorophyll; NOL, NYC1 non-yellow coloring 1; CLH, chlorophyllase; PAO, pheophorbide a oxygenase; Pheide, pheophorbide; PPH, pheophytinase; RCC, red Chl catabolite; RCCR, RCC reductase; SGR, stay-green protein. Numbers in the blocks indicate gene expression level in RPKM based on RNA-seq analysis.

Role of LcSGR in chlorophyll degradation and its interaction with LcPAO

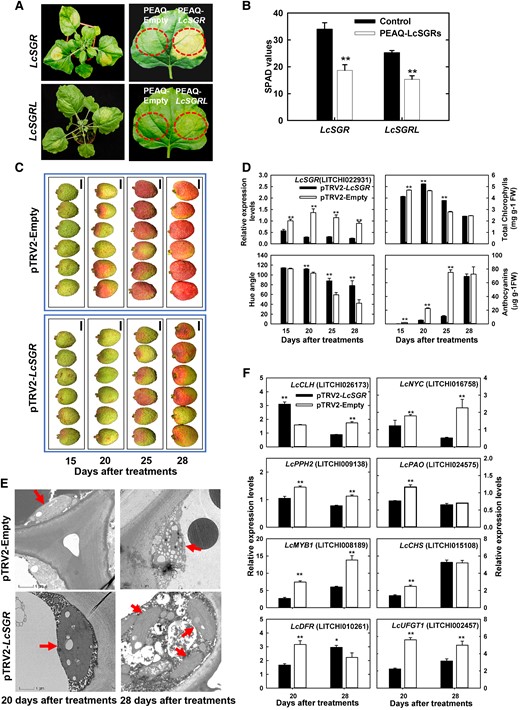

Then 2 differentially transcribed SGR genes, LcSGR and LcSGRL were characterized. Nicotiana benthamiana leaves transiently expressing LcSGR and LcSGRL displayed bleaching phenotype and had a significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) lower soil and plant analyzer development (SPAD, a parameter that reflects chlorophyll levels) value compared with the wild type (Fig. 2, A and B). Since the bleaching phenotype was more prominent in leaves overexpressing LcSGR than in those overexpressing LcSGRL, we suppressed LcSGR expression in a red litchi cultivar “Yingzhizaohong” (YZZH) using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) (Fig. 2, C and D). In response to LcSGR silencing, both chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin accumulation were delayed, resulting in a significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) lower hue angle value (Fig. 2D). These results suggested the critical role of LcSGR in chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin accumulation in the litchi pericarp.

Functional verification of LcSGRs by transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves and VIGS in litchi “YZZH.” A) The phenotype of N. benthamiana leaves transiently expressing PEAQ-LcSGRs, with the empty PEAQ vector as a control. B) SPAD values of N. benthamiana leaves transiently expressing PEAQ-LcSGRs. Bars above the columns represent standard error of mean. Double asterisks (**) indicate significant difference compared with the control at P < 0.01, Student's t-test (n = 6). C) Litchi fruit color phenotype after LcSGR silencing using pTRV2-vector. Images were digitally extracted for comparison. Bars = 1 cm. D) Changes of LcSGR expression, color parameters, chlorophyll contents, and anthocyanin contents in the pericarp in response to the silencing of LcSGR. Bars above columns represent standard error of mean. Double asterisks (**) indicate significant difference compared with the control at P < 0.01, Student's t-test (n = 12). E) Changes in pericarp chloroplast structure observed using a transmission electron microscope in response to LcSGR silencing. The red arrows denote chloroplasts. Bars = 1 μm. F) Changes in the expression of genes involved in chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis in response to LcSGR silencing. Bars above columns represent standard error of mean. Single asterisks (*) and double asterisks (**) represent significance compared to the control at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, Student's t-test (n = 3).

To gain more understanding, changes in chloroplast structure in the pericarp were examined under transmission electron microscopy and the expression of key chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis genes was tracked in response to LcSGR silencing. A well-developed functional chloroplast is generally long oval or spindle in shape and has a complete chloroplast membrane with a small number of osmiophilic particles on the surface of the closely arranged matrix lamellae and grana lamellae (Oi et al. 2020). As litchi fruit ripens, chlorophyll loss is usually accompanied by chloroplast disintegration (Wang et al. 2002). Disintegrated chloroplasts were found in the pTRV2-Empty control pericarp, while intact chloroplasts with starch granules and clear lamellar structure were found in the pTRV2-LcSGR pericarp at 20 d after treatments (Fig. 2E). These findings suggested that the LcSGR protein is required for chloroplast breakdown. In response to LcSGR silencing, the expression of LcNYC (LITCHI016758), LcPPH2 (LITCHI0009138), and LcPAO (LITCHI024575) was significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) suppressed and so was the expression of litchi anthocyanin biosynthesis key structural genes including LcMYB1 (LITCHI008189), LcCHS (CHALCONE SYNTHASE) (LITCHI015108), LcDFR (LITCHI002550), and LcUFGT1 (LITCHI002457), at 20 d after treatments when the delayed degreening and pigmentation phenotype was noticed (Fig. 2F).

Since the expression of LcMYB1 deceased in response to the silencing of LcSGR, LcSGR might be an upstream regulator of LcMYB1. In a yeast-one-hybrid (Y1H) assay and a dual-luciferase (LUC) assay, however, LcSGR showed no interaction with the LcMYB1 promoter (Supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that LcSGR affected the expression of LcMYB1 in an indirect way.

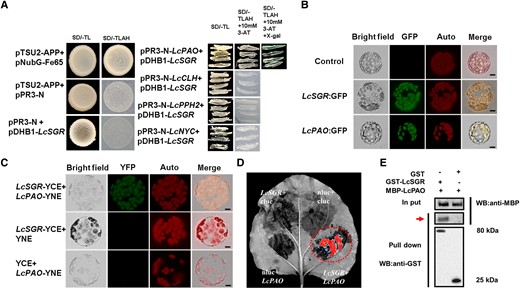

To explain how LcSGR works, we explored the potential LcSGR partner using yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) assays and targeted LcPAO as one of putative proteins (Fig. 3A). The subcellular localization assay revealed that LcSGR and LcPAO colocalized in the chloroplast (Fig. 3B), and a bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay revealed an interaction between LcSGR and LcPAO (Fig. 3C). Their interaction was further confirmed with firefly LUC complementation imaging (Fig. 3D) and a GST-pull down assay (Fig. 3E). These results indicated that LcSGR enhanced chlorophyll degradation and chloroplast breakdown by interacting with LcPAO protein. This is consistent with the findings of Sakuraba et al. (2012), who demonstrated that SGR interacted with chlorophyll catabolic enzymes (CCEs) including PAO at light-harvesting complex II for chlorophyll degradation during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis.

LcSGR physically interacts with LcPAO. A) The interaction between LcSGR and key chlorophyll degradation enzymes in Y2H assays. pTSU-APP with pNubG-Fe65 served as a positive control and pTSU-APP with pPR3-N and pPR3-N with pDHB1-LcSGR served as negative control. B) Subcellular location of LcSGR and LcPAO in N. benthamiana leaves cells. C) LcSGR and LcPAO interact in mesophyll protoplasts of N. benthamiana. YFP signal of LcSGR interacting with LcPAO observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Chlorophyll fluorescence as red signals (middle) with LcSGR fused with YNE or LcPAO fused with YCE serving as a negative control. D) Imaging of firefly LUC complementation in N. benthamiana leaves. The LcSGR-nluc and LcPAO-cluc fused vectors were cotransformed in N. benthamiana leaves with LcSGR-nluc + cluc, LcPAO-cluc, and nluc + cluc serving as negative controls. E) LcSGR GST pull-down assay. The bound protein was detected by western blotting with anti-GST and anti-MBP antibodies. A red arrow indicates the pull down protein.

The role of putative NACs in the regulation of litchi coloration

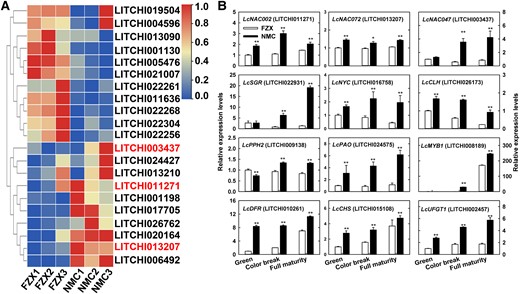

In recent years, the NAC TF family has been linked to fruit development, ripening, and coloration. We screened the RNA-seq DEG data for NACs. We identified 21 DEGs in the NAC family, and 7 of these NAC genes exhibited significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) higher expression in NMC compared to in FZX (Fig. 4A). We further explored LcNAC002 (LITCHI011271), LcNAC072 (LITCHI013207), and LcNAC047 (LITCHI003437) because their transcription levels were significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) higher than those of the other LcNACs. Phylogenetic analysis showed that LcNAC002, LcNAC072, and LcNAC047 were clustered with ANAC002, ANAC019 and ANAC055, and ANAC047, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S3). In parallel with the significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) higher expressions of key chlorophyll degradation genes including LcSGR, LcNYC, LcCLH, LcPPH2 and LcPAO, and anthocyanin biosynthesis genes such as LcMYB1, LcCHS, LcDFR, and LcUFGT1, the transcription levels of the 3 NACs were all significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) higher in the pericarp of NMC than in that of FZX (Fig. 4B).

Expression profiles of NAC DEGs and key genes involved in chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin synthesis. A) A heat map of relative expression levels of LcNAC DEGs based on RNA-seq analysis. The expression levels were normalized with the highest expression level of the same gene across cultivars and stages arbitrarily valued as 1.0. Three LcNACs marked in red were selected for reverse transcription quantitative real-time-PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis. B) TR-qPCR analysis of the selected LcNAC and key DEGs involved in chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin synthesis. SGR, stay-green protein; NYC, non-yellow coloring 1; CLH, chlorophyllase; PPH, pheophytinase; PAO, pheophorbide a oxygenase; DFR, dihydroflavonol reductase; CHS, chalcone synthase; UFGT, UDP-flavonoid glucosyl transferase. Bars at the top of the columns indicate standard error of mean. The asterisks (*) and double asterisks (**) represent significant difference between NMC and FZX at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, Student's t-test (n = 3).

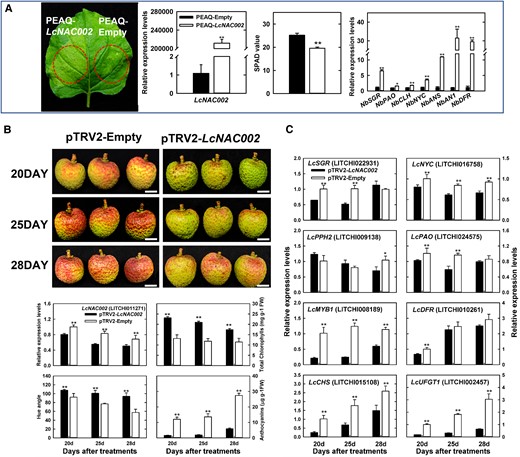

LcNAC002 plays an important role in chlorophyll degradation and pigmentation

LcNAC047, corresponding to the LcNAC13 named by Jiang, has been previously shown to negatively regulate the expression anthocyanin biosynthesis genes and thus inhibit anthocyanin accumulation in the pericarp of litchi (Jiang et al. 2019). In the present study, the role of LcNAC002 and LcNAC0072 in chlorophyll degradation was investigated. Only the leaves transiently expressing LcNAC002 exhibited degreening and a significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) lower SPAD value phenotype (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Fig. S4). In addition, key genes involved in N. benthamiana chlorophyll degradation (NbSGR, NbPAO, NbCLH, and NbNYC) and flavonoid biosynthesis (NbANS [ANTHOCYANIDIN SYNTHASE], NbAN1 [ANTHOCYANIN 1], and NbDFR) were all upregulated in response to the overexpression of LcNAC002. VIGS assay was employed to knock down LcNAC002 in litchi pericarp 3 wk before maturity. As shown in Fig. 5B, silencing LcNAC002 significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) inhibited both chlorophyll loss and anthocyanin accumulation, and thus coloration was clearly delayed. Furthermore, reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis showed that the expression of both chlorophyll degradation-related (LcSGR, LcNYC, and LcPAO) and anthocyanin accumulation-related genes (LcMYB1, LcCHS, LcDFR, and LcUFGT1) were all significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) inhibited (Fig. 5C). These results suggested that LcNAC002 is a key positive regulator in both chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis in the litchi pericarp.

Functional analyses related to the role of LcNAC002 in coloration. A) The phenotype, SPAD value, and the expression of key chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis genes in N. benthamiana leaves transiently expressing PEAQ-LcNAC002. B) Functional verification of LcNAC002 using VIGS in pericarp of litchi (YZZH) and changes in LcNAC002 expression, color parameters, chlorophyll contents, anthocyanin contents in the pericarp in response to LcNAC002 silencing. C) Changes in the expression of chlorophyll degradation- and anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes in response to LcNAC002 silencing. Bars at the top of the columns indicate standard error of mean. Single asterisks (*) and double asterisks (**) represent significant difference compared to the control with empty vector treatment at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively (Student's t-test, n = 3 for gene expression and pigments, n = 6 for SPAD value, and n = 12 for Hue angle).

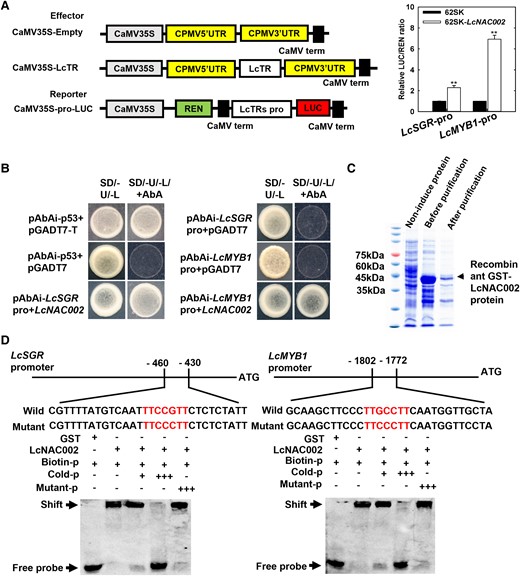

LcNAC002 enhances LcSGR and LcMYB1 expression by directly binding to their promoters

The nuclear located LcNAC002 served as a transcriptional activator because only yeast cells containing pGBKT7-LcNAC002 grew well on SD/Trp–His–Ade selective medium, and a dual-LUC reporter (DLR) assay demonstrated that expression of pBD-LcNAC002 markedly activated LUC expression when compared to the empty control pBD (Supplemental Fig. S5). DLR and Y1H assays were then performed to examine the role of LcNAC002 in regulation of LcSGR and LcMYB1 expression. A transient dual LUC assay confirmed that LcNAC002 markedly enhances LUC expression driven by the LcSGR and LcMYB1 promoters (Fig. 6A). A Y1H assay confirmed the interaction of LcNAC002 with the promoters of LcSGR and LcMYB1 (Fig. 6B). When yeast cells with LcSGR and LcMYB1 promoters were transformed with a plasmid carrying a constitutively expressed LcNAC002 effector, they grew well in SD/Ura–Leu selective medium with AbA. Furthermore, electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA) revealed that LNAC002 bound to an upstream TTCCGTT domain of LcSGR and LcMYB1 promoters, and guanosine acid (G) in the TTCCGTT domain is essential for the binding (Fig. 6D).

LcSGR and LcMYB1 are downstream target genes of LcNAC002. A) LcNAC002 activates LcSGR and LcMYB promoters in a dual-LUC assay. Nicotiana benthamiana leaf cells were cotransformed with reporter and effector vectors. The ratio of LUC to REN indicated LcNAC002's ability to bind to LcSGR and LcMYB promoters. Bars above the column indicate the standard error of mean. Double asterisks (**) represent significant difference at P < 0.01, Student's t-test (n = 6). B) A Y1H assay revealed that LcNAC002 binds to the promoters of LcSGR and LcMYB. Interaction between bait and prey on synthetic drop-out nutrient medium lacking Ura and Leu and containing 500 ng mL−1 ABA. C) The EMSA of LcNAC002 binding to LcSGR and LcMYB promoters. D) The GST-LcNAC002 (0 to 150 aa) recombinant protein binds to the 430 to 460 upstream and 1,772 to 1,802 upstream fragments of LcSGR and LcMYB1 promoters, respectively.

Discussion

LcSGR acts as a critical protein in the degreening of litchi pericarp

Chlorophyll degradation leading to degreening occurs during the processes of leaf senescence and fruit ripening. The PAO pathway, the biochemical pathway of chlorophyll degradation, has been elucidated in the past decade (Christ and Hörtensteiner 2013). SGR has been shown to serve as a recruiter of CCEs by interacting with CCEs and binding to LHCII (Sakuraba et al. 2012). Other studies showed that it encodes Mg-dechelatase, which catalyzes the first step of Chl a degradation (Matsuda et al. 2016; Shimoda et al. 2016). In this study, LcSGR and LcSGRL were found to have much higher expression in degreening cultivar NMC than in stay-green cultivar FZX (Fig. 1). Leaves of N. benthamiana transiently overexpressing LcSGR and LcSGRL showed bleaching with a significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) lower SPAD value compared with the wild type, and the bleaching effect was stronger in leaves overexpressing LcSGR than in those overexpressing LcSGRL (Fig. 2A). This result is consistent with the previous report from Lai et al. (2015).

Knocking down LcSGR in litchi pericarp resulted in substantially slower chlorophyll degradation and thus the stay-green phenotype (Fig. 2, C and D). Furthermore, interactions between the LcSGR and LcPAO proteins observed in this study (Fig. 3) indicated LcSGR promotes chlorophyll degradation in ripening fruit of litchi probably by recruiting LcPAO, similar to the SGR roles in leaf senescence in Arabidopsis (Sakuraba et al. 2012).

LcNAC002 promotes chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis by directly targeting LcSGR and LcMYB1 promoters

The fruit ripening of most litchi cultivars is accompanied by chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin synthesis, both of which contribute to fruit coloration (Wang et al 2017). As previously stated, LcSGR plays an important role in chlorophyll degradation, and earlier studies have identified LcMYB1 as a key TF determining anthocyanin biosynthesis in the litchi pericarp (Wei et al. 2011; Lai et al. 2014). However, the upstream regulators of these 2 genes remains poorly explored. Chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis are the 2 most noticeable biological processes during litchi fruit maturation. NACs are among the specific TFs that switch the ripening in both climacteric and nonclimacteric fruits (Martín-Pizarro et al. 2021; Migicovsky et al. 2021). In the present study, LcNAC002 expression was found to be significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) higher in rapid degreening/reddening NMC than in stay-green FZX (Fig. 4). Transient overexpression of LcNAC002 in N. benthamiana leaves enhanced chlorophyll loss, whereas LcNAC002 silencing in litchi pericarp inhibited chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin accumulation (Fig. 5). These findings suggest that LcNAC002 might serve as a positive regulator of both chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis.

However, available studies suggested that NAC might play either positive or negative role in anthocyanin accumulation depending on the sequence difference of NACs. Knockout of ANAC078 decreased the transcription of flavonoid biosynthesis-related genes including AtPAP1, AtCHS, AtCHI, and AtF3H, while overexpression of it increased their expression (Morishita et al. 2009). Likewise, knockout of another Arabidopsis NAC, ANAC019, resulted in significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) lowered expression of AtCHI, AtCHS, AtF3H, AtDFR, and AtDFR (Hickman et al. 2013). After 3 to 6 d of cold storage, there was a substantial increase in the amounts of transcripts of PAL (PHENYLALANINE AMMONIA LYASE), CHS, DFR, ANS, UFGT, and GST in blood oranges [(C. sinensis) L. Osbeck Tarocco Sciara] but not in common oranges [(C. sinensis) L. Osbeck Navel], which coincided with a selectively induced NAC (Crifó et al. 2012). In this study, significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) higher expression of NbANS, NbANI, and NbDFR was observed in leaves of N. benthamiana overexpressing LcNAC002 compared to in wild-type leaves, whereas significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) lower expression of LcMYB1, LcCHS, LcDFR, and LcUFGT1 was observed in response to LcNAC002 silencing in litchi pericarp (Fig. 5).

The MYB TFs control the expression of flavonoid biosynthetic structural genes. Previously, 2 apple NACs, MdNAC52 and MdNAC42, and a peach NAC (BL) were shown to promote the anthocyanin biosynthesis by enhancing the expression of key MYB TFs (Zhou et al. 2015; Sun et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2020). The observed expression changes in response to NAC expression change could be attributed to NAC's direct action on key MYB involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis. In this study, LcNAC002 was found to significantly (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) activate LcMYB1 expression by binding to its promoter through a TTCCGTT domain (Fig. 6). These findings implicate that LcNAC002 as an upstream regulator of LcMYB1 expression plays critical role in litchi anthocyanin biosynthesis and thus pigmentation.

Although NACs have been shown to play a critical role in leaf degreening during senescence, their roles in chlorophyll loss in fruits and how they work are still largely unknown. In Arabidopsis, ANAC019, ANAC055, and ANAC072 have been reported as a positive regulator of leaf senescence by activating AtSGR expression (Zhu et al. 2015; Broda et al. 2021). ANAC092/ORE1 promotes leaf senescence by activating the expression of NYE1, NYC1, and PAO through binding to their promoters (Balazadeh et al. 2010). Overexpression of ZmNAC126 in Arabidopsis and maize (Zea mays) enhanced chlorophyll degradation and promoted leaf senescence (Xiao et al. 2021). In tomato, SlNAP2 promoted leaf senescence by potentially activating SlSGR1 and SlPAO expression (Ma et al. 2018). Overexpression of OsNAC2 resulted in upregulation of OsSGR (Singh et al. 2021), and the expressions of chlorophyll catabolic genes such as PAO-like, HCAR-like, and NYC/NOL-like were substantially elevated in MpSNAC67 overexpressing leaves (Tak et al. 2018). SGR1 was suggested as a potential direct target of VviNAC33 (D’Incà et al. 2021). In the present study, LcNAC002 was shown to promote LcSGR expression in the litchi pericarp by directly binding to its promoter (Fig. 6).

Taken together, our results define LcNAC002 as an interlink in the regulatory pathways of chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis during litchi fruit ripening. LcNAC002 upregulates both biological pathways by directly activating the expression of both LcSGR and LcMYB1.

LcSGR serves as an indirect regulator of genes involved in chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis

Bagging litchi fruit clusters with light impermeable bags results in reduced chlorophyll and a sharper postdebagging increase in anthocyanin accumulation with higher expression of LcUFGT1 in the pericarp compared to the unbagged control (Wei et al. 2011). Some stay-green litchi cultivars, such as “Yamulong” and “Xingqiumuli,” have a substantial delay in anthocyanin accumulation and thus produce green fruits at commercial ripeness before they are pigmented (Wang et al. 2017). The degradation of chlorophylls in litchi pericarp generally occurs prior to the accumulation of anthocyanins, giving a short color-break stage with fruit yellowing prior to reddening. It seems that chlorophyll degradation somehow promotes anthocyanin accumulation.

As mentioned above, it is well understood that LcSGR accelerates chlorophyll degradation as a recruiter of CCEs. However, silencing LcSGR also caused significant (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) reduction in transcription levels of both chlorophyll catabolic genes (LcNYC, LcPPH2, and LcPAO) and anthocyanin synthesis genes (LcMYB1, LcCHS, and LcUFGT1) (Fig. 2, E and F), with delayed chloroplast breakdown and anthocyanin accumulation, suggesting that LcSGR has a regulatory role in transcription of these genes. Since LcSGR is not a TF and is located in chloroplast instead of nucleus (Fig. 3), it is unlikely that LcSGR directly regulates gene transcription. As expected, LcSGR showed no interaction with LcMYB1 promoter (Supplemental Fig. S2). The possible indirect ways, in which LcSGR regulates gene expression, are worth exploration.

Chlorophylls are plant pigments that absorb light and transfer excited energy for photochemical reactions. SGR has been shown to play a key role in the interactions of NON YELLOW COLORING1 (NYC1) and NYC1-like (NOL) proteins, which are involved in the degradation of LHCII and the thylakoid membrane during senescence (Sakuraba et al. 2012). In Arabidopsis, the degradation of chlorophylls is accompanied by accumulation of ABA and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to the overexpression of ZjNYC1 (Teng et al. 2021). The role of ABA in the regulation of chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis as well as genes involved has been well established (Jia et al. 2011; Wei et al. 2011; Shen et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2016; Hu et al. 2019). Significantly higher ABA was detected in the pericarp of degreening NMC than in that of stay-green FZX (Wang et al. 2007). ROS signaling has been shown to play a key role in anthocyanin accumulation (Wu et al. 2016; Sun et al. 2021). The intracellular reduction–oxidation (redox) status is tightly regulated by oxidant and antioxidant systems. The increased anthocyanin under high ROS conditions, in turn, helps to quench the ROS production during degreening (Moustaka et al. 2018). Evidence suggests that ROS can cause post-translational oxidative modification of TFs, resulting in altered gene expression in response to developmental changes or environmental inputs (Lundquist et al. 2014; Tian et al. 2018; Li et al. 2019). Redox remodification of NON-RIPENING (NOR) influences tomato fruit ripening by regulating the expression of ripening-related genes (Jiang et al. 2020). These findings may help to explain the phenomenon of increased anthocyanin accumulation in the presence of low chlorophyll levels. The downregulation of key anthocyanin biosynthesis and chlorophyll degradation genes and thus delayed chlorophyll loss and anthocyanin accumulation in response to LcSGR silencing (Fig. 2) might be mediated by the decreased ABA and ROS, which are suggested to accumulate with chlorophyll degradation accelerated by LcSGR and LcNYC1 and subsequently upregulate both chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin synthesis genes. This indirect bypass of LcSGR regulatory pathway in chlorophyll degradation and thus anthocyanin synthesis is worth further investigation.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The plant materials were obtained from the experimental orchard of South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou, China. To investigate key genes involved in chlorophyll degradation and anthocyanin biosynthesis during fruit ripening, litchi (L. chinensis Sonn.) cultivars with contrasting coloration pattern, the fully red “Nuomici” (NMC) and green ripe or stay-green “FZX,” were chosen. FZX is a mid-season cultivar, whereas NMC is a late-season cultivar. Although the weather was generally similar during their mature season in Guangzhou, we chose late flowering FZX which matured about 1 wk before NMC to minimize the influence of environmental difference. Samples were taken based on maturity (days before harvest, DBH). Fruit samples were collected at 3 fruit developmental stages: 21 DBH (green stage), 10 DBH (color break stage for NMC), and harvest stage. The samples were used for RNA-seq analysis as well as RT-qPCR analysis of selected genes. For VIGS assays, the cultivar “YZZH” of 3 litchi trees was chosen. Thirty bearing shoots of each tree in different directions of the canopy were tagged, and VIGS treatments were performed at 4 wk before full maturity (56 DAA). Pericarp samples were collected at 5 or 3 d intervals from 15 d after treatment, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Nicotiana benthamiana plants were grown in a sunlight green house at 28 °C for subcellular localization and the DLR assay.

Color analysis and determination of chlorophylls and anthocyanins

The pericarp color of 20 fruit was measured immediately after picking using a Konica Minolta CR-10 Chroma Meter (Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). The parameter hue angle (h*) was recorded. Pericarp chlorophylls were extracted with 80% (v/v) acetone for 24 h in the dark, and the leaching solution was measured for OD645 and OD663 with a UV1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Total content of chlorophylls was calculated according to Arnon (1949). Total anthocyanins were determined according to our previous method (Wei et al. 2011). A nondestructive determination of chlorophyll levels in N. benthamiana leaves was carried out using a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan), which reads chlorophyll level as SPAD value.

Transmission electron microscope assay

The transmission electron microscope assay was performed in accordance with Huang et al. (2002). Briefly, pericarp of litchi fruit was cut into rectangular strips about 0.5 mm × 2 mm in 4% glutaraldehyde and 3% paraformaldehyde fixing solution with a blade, and about 10 pieces of each sample were placed in a 2-mL centrifuge tube, fixed for 4 h at room temperature, and then fixed at 4 °C overnight. Five longitudinal ultrathin sections of each sample were prepared after alcohol gradient dehydration, spur-resin/acetone permeation, spur-infiltration, and plastic embedding. Three pieces of ultrathin sections were picked randomly and placed on the copper grids of 100 meshes. The chloroplast structure was observed under a transmission electron microscope (TECNAI 12, Phillips, The Netherlands).

RNA extraction, RT-qPCR, gene cloning, and bioinformation analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the stored pericarp samples using Quick RNA isolation kit (Huayueyang, Beijing, China). The Hifair III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for RT-qPCR (gDNA digester plus) was used to synthesize cDNA using 5 μg of total RNA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). qPCR was performed to determine gene expression levels based on Lai et al. (2015). The gene-specific primer pairs are listed in Supplemental Table S1, and the gene sequences were obtained from litchi database (https://www.sapindaceae.com).

The cDNAs of NMC pericarp were used as templates to clone LcNAC002, LcNAC047, and LcNAC072. The sequences of other species were acquired from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The phylogenetic tree was generated in MAGA11 using the Neighbor–Joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replications.

RNA-seq analysis

RNA-seq libraries were prepared and sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2500 system, according to the manufacturers’ instructions (Illumina, https://www.illumina.com). Each library consisted of equal amounts of RNA from 3 biological replicates. The RNA-seq data were processed, assembled, and annotated as previously described (Lai et al. 2015). De novo assembly of sequence data was carried out using Vazyme (Najin, China, https://www.vazyme.com/touzi.html). Genes with an expression log2 ratio ≥1 or ≤−1 between NMC and FZX were identified.

Subcellular localization analysis

The gene sequences were amplified using PCR (primers are listed in Supplemental Table S2) and fused into pGreen-35S-GFP (green fluorescent protein) using the Hieff Clone Plus One Step Cloning Kit (Yeasen Biotechnology). The recombinant vectors were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101:pSoup (Weidi Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves was performed according to our previous method (Lai et al. 2014). The N. benthamiana plants were grown in a greenhouse at 28 °C using natural light, and GFP fluorescence proteins were observed under a fluorescence microscope with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 529 nm (Zeiss Axio Observer D1, Oberkochen, Germany).

Protein interaction experiments

Y2H assays were performed using the Matchmaker Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System kit (Clontech, CA, USA) following product instructions (primers are listed in Supplemental Table S3). The CDS of LcSGR, LcNYC1, LcCLH, and LcPPH2 were cloned into PDHB1 and PPR3-N. Full length of LcSGR was used since it showed no transcriptional activation activity in yeast cells.

For BiFC assay, CDS were cloned into pSPYNE and pSPYCE vectors. Then the homologous recombination vectors were transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101-pSoup, and transiently coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. YFP fluorescence proteins were observed under fluorescence microscope with excitation at 488 nm and emission in the range 520 to 540 nm (Zeiss Axio Observer D1).

For the firefly LUC complementation imaging assay, the CDS of selected genes were cloned into pCambia1300-nLUC and pCambia1300-cLUC vectors, transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101-pSoup, and then transiently coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. LUC imaging was detected after 72 h using chemical fluorescence imager system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

For GST-pull down assay, protein with an MBP-tag and GST-tag was expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells and induced with 2 mM of isopropyl-b-D-thiogalactopyramoside (IPTG) for 8 h at 27 °C. GST-LcSGR or GST protein was added to MBP-LcPAO protein and incubated at 4 °C for 4 h, and then 50 μL glutathione resin in 1× phosphate buffered saline buffer was added at 4 °C for 8 h, followed by washing 4 or 5 times with wash buffer (1× phosphate buffered saline, 0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100). The proteins bound to the particles were eluted and separated with SDS-PAGE and visualized using western blotting assay. Pull down proteins with anti-GST were imaged on a Chemi-Doc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad). The primers are listed in Supplemental Table S4.

Transcriptional activation assays of LcNAC002

A Y1H assay was conducted using the Matchmaker Gold Yeast One-Hybrid System kit (Clontech, now TaKaRa, https://www.takarabio.com). DLR assay was carried out according to Hellens et al. (2005). By using the kpnI and NcoI enzyme cutting sites, 2 vectors of pGreenII 0800-LUC reporter vector and pGreenII 62-SK effector vector, as well as the promoters of LcSGR and LcMYB1, were cloned into the pGreen 0800-LUC reporter vector. LcNAC002 was cloned into pGreenII 62-SK effector vector by BamHI and EcoRI enzymes. The 2 reconstructed plasmids were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. Detection of LUC and REN activities was performed using a Dual Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay kit (Yeasen Biotechnology) with dual-LUC reagents (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The ratio of LUC to REN was used to analyze the results, and 3 biological repeats were set.

EMSA was performed using LightShift EMSA Optimization and Control Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instruction. The probes containing the LcNAC002-binding site in the promoters of LcSGR and LcMYB1 were labeled with biotin using Biotin3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). The CDS of LcNAC002 was cloned into pGEX-4T-1 vector, expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells, and then induced with 2 mM IPTG for 8 h at 17 °C. The obtained recombinant GST-LcNAC002 proteins were tested by GSTSep glutathione agarose resin (YEASEN, https://www.yeasen.com) with GST protein as the negative control.

VIGS-mediated silencing of gene expressions

VIGS was carried out as described earlier by Zhang et al. (2018). The fragment of LcNAC002 (420 bp) and full length of LcSGR were cloned into TRV2 vector. To silence the genes, a microbial concentration of OD600 = 1.0 was injected into the fruit peduncle with a syringe. Twenty panicles were treated in each tree of YZZH at 56 d after anthesis. Three single-tree-based biological replicates were set up. Samples were collected from 15 to 20 d after treatments at intervals of 5 d. The primer pairs were listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Statistics

Gene expression and phenotypic analyses were carried out with at least 3 biological replicates. Significance of difference between the treatment (gene silencing or overexpression) and the control (wild type or treatment with empty vectors) or between cultivars was analyzed with Student's t-test using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers shown in the following table.

Gene—Accession number

NbSGR—XM_016651072.1

NbPAO—EU294211.1

NbCLH—ACH54085.1

NbNYC—NM_001326040.1

NbANS—AB289447

NbANI—HQ589208

NbDFR—NM_001325732.1

LcSGR—AKA88530.1

LcCHS—QRV61377.1

LcUFGT1—ALH45553.1

LcMYB1—APP94121.1

LcNAC002—UBT01638.1

LcActin—HQ615689

NbActin—NM_001325628.1

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Minglei Zhao, Xia Rui, and Prof. Jianguo Li for their valuable suggestions.

Author contributions

W.H.C. and H.X.M. designed the research; Z.S.C. and Z.M.G. performed the experiments; A.F., W.H.C., and H.G.B. performed data analysis and interpreted the results; W.H.C., H.X.M., and Z.S.C. wrote the manuscript.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Analyses of RNA-seq data from FZX and NMC pericarp at different stages.

Supplemental Figure S2. Test of the interaction of LcSGR to the promoter of LcMYB1.

Supplemental Figure S3. Phylogenetic analysis of LcNAC002, LcNAC072, and LcNAC047 with homolog proteins from Arabidopsis and other species reported.

Supplemental Figure S4. The phenotype and SPAD value in N. benthamiana—leaves transiently expressing PEAQ-LcNAC072 and PEAQ-empty.

Supplemental Figure S5. Subcellular localization patterns and transcriptional activity analysis of LcNAC002.

Supplemental Table S1. Primer sequences used for RT-qPCR expression analysis

Supplemental Table S2. Primer sequences used for transient expression analysis and VIGS assays

Supplemental Table S3. Primer sequences used for Y1H and Y2H

Supplemental Table S4. Primer sequences used for GST pull-down assays and EMSA assays

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2018YFD1000200), the National Natural Science Fund of China (project nos 31772248 and 32272663), and the China Litchi and Longan Industry Technology Research System (project no. CARS-32-08).

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

Author notes

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the 31 policy described in the Instructions for in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://dbpia.nl.go.kr/plphys/pages/General-Instructions) is Yunqing Yu ([email protected]).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.