-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jill Romer, Katharina Gutbrod, Antonia Schuppener, Michael Melzer, Stefanie J Müller-Schüssele, Andreas J Meyer, Peter Dörmann, Tocopherol and phylloquinone biosynthesis in chloroplasts requires the phytol kinase VITAMIN E PATHWAY GENE5 (VTE5) and the farnesol kinase (FOLK), The Plant Cell, Volume 36, Issue 4, April 2024, Pages 1140–1158, https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koad316

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chlorophyll degradation causes the release of phytol, which is converted into phytyl diphosphate (phytyl-PP) by phytol kinase (VITAMIN E PATHWAY GENE5 [VTE5]) and phytyl phosphate (phytyl-P) kinase (VTE6). The kinase pathway is important for tocopherol synthesis, as the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) vte5 mutant contains reduced levels of tocopherol. Arabidopsis harbors one paralog of VTE5, farnesol kinase (FOLK) involved in farnesol phosphorylation. Here, we demonstrate that VTE5 and FOLK harbor kinase activities for phytol, geranylgeraniol, and farnesol with different specificities. While the tocopherol content of the folk mutant is unchanged, vte5-2 folk plants completely lack tocopherol. Tocopherol deficiency in vte5-2 plants can be complemented by overexpression of FOLK, indicating that FOLK is an authentic gene of tocopherol synthesis. The vte5-2 folk plants contain only ∼40% of wild-type amounts of phylloquinone, demonstrating that VTE5 and FOLK both contribute in part to phylloquinone synthesis. Tocotrienol and menaquinone-4 were produced in vte5-2 folk plants after supplementation with homogentisate or 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid, respectively, indicating that their synthesis is independent of the VTE5/FOLK pathway. These results show that phytyl moieties for tocopherol synthesis are completely but, for phylloquinone production, only partially derived from geranylgeranyl-chlorophyll and phytol phosphorylation by VTE5 and FOLK.

Background: Isoprenoid lipids in Arabidopsis chloroplasts include chlorophyll, carotenoids, tocopherols (vitamin E), and phylloquinone (vitamin K). Their biosynthesis depends on the availability of the isoprenoid precursors geranylgeranyl diphosphate and phytyl diphosphate. The geranylgeranyl moiety can first be incorporated into chlorophyll where it is reduced to the phytyl group and subsequently hydrolyzed. Phytol kinase (VITAMIN E PATHWAY GENE5 [VTE5]) phosphorylates phytol, and phytol-phosphate kinase (VTE6) produces phytyl diphosphate that is employed for tocopherol and phylloquinone synthesis. While the vte5 mutant of Arabidopsis contains reduced amounts of tocopherol, the vte6 mutant is deficient in tocopherol and phylloquinone.

Questions: Why do tocopherol and phylloquinone syntheses differentially depend on phytol phosphorylation by phytol kinase (VTE5)? Does another kinase contribute to phytol phosphorylation?

Findings:Arabidopsis contains 1 paralog to VTE5, farnesol kinase (FOLK), which is involved in farnesol phosphorylation. We show here that FOLK also phosphorylates phytol. While the vte5 folk double mutant is completely devoid of tocopherol, it still accumulates residual amounts of phylloquinone. The amounts of chlorophyll and carotenoids are not affected in the vte5 folk mutant. Ectopic expression of FOLK partially complements tocopherol deficiency in vte5. Therefore, VTE5 and FOLK are essential to provide phytol-phosphate for tocopherol synthesis, but alternative pathways exist to provide the phytyl group during phylloquinone synthesis.

Next steps: Further research is required to elucidate the contribution of the different pathways to geranylgeraniol and phytol metabolism for isoprenoid lipid synthesis in chloroplasts.

Introduction

Isoprenoids represent one of the largest classes of metabolites in plants, and they include numerous essential compounds like chlorophyll, carotenoids, quinone lipids (plastoquinone, phylloquinone, tocopherol, and ubiquinone), and phytohormones (abscisic acid [ABA] and gibberellic acid [GA]). Two pathways contribute to de novo isoprenoid synthesis in plants, the mevalonate pathway localized in the cytosol/peroxisomes, which is also active in animals and yeast, and the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in the chloroplasts also found in many bacteria (Lichtenthaler et al. 1997; Flesch and Rohmer 1988). Each of the 2 pathways results in the synthesis of the 2 C5 isoprenoid precursors, isopentenyl diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate. Successive condensation reactions of these C5 units lead to the production of geranyl diphosphate (geranyl-PP), farnesyl diphosphate (farnesyl-PP), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (geranylgeranyl-PP). Farnesyl-PP and geranylgeranyl-PP are the substrates for protein prenylation, and farnesyl-PP is required for sterol synthesis (Randall et al. 1993). Geranylgeranyl-PP in the chloroplast is the precursor for carotenoids (Cunningham and Gantt 1998). Phytol, which is the isoprenoid side chain of chlorophyll, tocopherol, and phylloquinone, is synthesized by the reduction of 3 double bonds of the geranylgeranyl moiety by geranylgeranyl reductase (GGR) in chloroplasts. GGR catalyzes the reduction of geranylgeranyl-chlorophyll to chlorophyll and might also be active with the alternative substrate geranylgeranyl-PP (Keller et al. 1998). The phytohormones ABA and GA are synthesized from the carotenoid zeaxanthin or from geranylgeranyl-PP, respectively (Finkelstein 2013). Tocopherols together with tocotrienols and plastochromanol-8 (PC-8) are tocochromanols, lipid antioxidants in the chloroplasts. Tocochromanols collectively exert vitamin E activity in mammals. Tocopherols with saturated side chain are abundant in dicot plants including Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), while tocotrienols with unsaturated side chain are mostly found in monocots (Cahoon et al. 2003). Tocopherols are synthesized by condensation of homogentisate from the shikimate pathway with phytyl diphosphate (phytyl-PP), while tocotrienols are derived from condensation of homogentisate with geranylgeranyl-PP (Cahoon et al. 2003). Phylloquinone, an electron carrier in PSI (Basset et al. 2017), consists of a methylated naphthoquinone ring with a phytyl-PP-derived side chain. Phylloquinone is essential for humans because it harbors vitamin K activity. Biosynthesis of phylloquinone in plants starts with chorismate and is localized to chloroplasts with some reactions taking place in peroxisomes (Reumann et al. 2007). The late steps of phylloquinone synthesis in the chloroplast include the attachment of a phytyl group to 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid (DHNA) by the prenyltransferase ABC4 (MenA) (Basset et al. 2017).

Free isoprenoid alcohols are of low abundance. Because of their detergent-like characteristics, which affect protein and membrane integrity, isoprenoid alcohols are rapidly metabolized or degraded. Phytol is rapidly metabolized by (i) deposition in the form of fatty acid phytyl esters (FAPEs) that are synthesized by the 2 enzymes, phytyl ester synthase 1 and 2 (PES1 and PES2) in Arabidopsis (Lippold et al. 2012); (ii) degradation via α- and β-oxidation, following a pathway similar to phytol degradation in animals (Gutbrod et al. 2021); (iii) recycling by phosphorylation in 2 consecutive steps yielding phytyl phosphate (phytyl-P) and phytyl-PP that can be used for tocopherol or phylloquinone synthesis. The scenario that phytol for tocopherol synthesis is derived from chlorophyll hydrolysis and subsequent phosphorylation of phytol is corroborated by the identification of the protochlorophyllide reductases POR1 and POR2 involved in chlorophyll synthesis, and the α/β hydrolase VTE7 presumably involved in chlorophyll hydrolysis, as determinants for tocopherol synthesis in Arabidopsis and maize (Zea mays) (Diepenbrock et al. 2017; Zhan et al. 2019; Albert et al. 2022).

VITAMIN E PATHWAY GENE5 (VTE5) catalyzes the phosphorylation of phytol (Valentin et al. 2006). The Arabidopsis vte5-1 and vte5-2 null mutants contain reduced tocopherol levels in seeds (∼20% of wild-type levels), while in leaves, the tocopherol content is reduced to ∼50% (Valentin et al. 2006; vom Dorp et al. 2015). It was believed that the residual amount of tocopherol in vte5 plants is produced using phytyl-PP from the reduction of geranylgeranyl-PP from the MEP pathway. The phosphorylation of phytyl-P is catalyzed by phytyl-P kinase (VTE6) (vom Dorp et al. 2015). The Arabidopsis vte6 null mutant completely lacks tocopherol and phylloquinone (vom Dorp et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2017). In contrast to other tocopherol-deficient plants (vte1 and vte2) that grow normally, vte6 plants display a dwarf and chlorotic phenotype (Porfirova et al. 2002; Collakova and DellaPenna 2003; Sattler et al. 2004).

Farnesol and geranylgeraniol can be converted in 2 consecutive steps into their respective activated diphosphorylated forms by enzymes present in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) cells (Thai et al. 1999). Arabidopsis contains only 1 paralog of VTE5 designated FOLK for farnesol kinase (FOLK) (Fitzpatrick et al. 2011). Recombinant FOLK protein phosphorylates geraniol, farnesol, and, to a lesser extent, geranylgeraniol, while phytol was never tested (Fitzpatrick et al. 2011).

At present, the contributions of the MEP pathway or the kinase pathway for the synthesis of geranylgeranyl-PP and phytyl-PP and for the different geranylgeranyl/phytyl-derived lipids in chloroplasts remain unclear. To address the question of the origin of phytyl-PP for the synthesis of tocopherol and phylloquinone, as well as the origin of geranylgeranyl-PP for the synthesis of carotenoids and ABA, we hypothesized that VTE5 and FOLK might both be involved to the phosphorylation of phytol and geranylgeraniol. The generation of the vte5-2 folk double mutant revealed that although this plant is completely devoid of tocopherol, considerable amounts of phylloquinone are still produced, while the amounts of chlorophyll, carotenoids, and ABA are unchanged. Therefore, FOLK represents an authentic enzyme of tocopherol synthesis. Analysis of enzyme specificity and of the levels of isoprenoid metabolites in plant extracts indicated that chloroplasts exclusively employ phytyl-PP derived from the kinase pathway for tocopherol synthesis, while phylloquinone is only in part derived from the kinase pathway.

Results

Contents of chlorophyll, carotenoids, and ABA in the vte5-2 folk-2 double mutant are not changed

It has previously been shown that the Arabidopsis phytol kinase VTE5 is involved in the synthesis of phytyl-P, which is subsequently converted to phytyl-PP, the precursor for tocopherol and phylloquinone synthesis, by VTE6. Two vte5 mutant alleles (vte5-1 and vte5-2) have been identified as null mutations because the vte5-1 sequence harbors a premature stop codon, while vte5-2 carries a transposon insertion in the first exon (Valentin et al. 2006; vom Dorp et al. 2015). Due to the residual amount of tocopherol detectable in the vte5-1 and vte5-2 plants, we considered the possibility that a second kinase might be involved in the generation of phytyl-P for tocopherol synthesis. Previous BLAST searches revealed that Arabidopsis harbors only 1 paralog of VTE5, which was designated FOLK (Valentin et al. 2006; Fitzpatrick et al. 2011). To study the role of FOLK in tocopherol metabolism, the double mutant vte5-2 folk-2 was generated by crossing vte5-2 and folk-2. The double mutant plants were grown on soil and were fully fertile, similar to the single mutant plants (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Electron microscopy of vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 chloroplasts revealed no visible alterations of the size or morphology of chloroplast ultrastructure including thylakoids and plastoglobules (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Chlorophyll fluorescence in leaves was studied using pulse-amplified modulation (PAM) fluorometry. Plants were dark adapted for 1 h and then exposed to 0, 150, 500, or 900 µmol s−1 m−2 of light, and the photosynthetic quantum yield of PSII was recorded. The single and double mutant plants displayed similar photosynthetic quantum yields with no significant differences to Col-0 under all light conditions (Supplementary Fig. S1C).

The chlorophyll contents in leaves of vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 plants were very similar to that in Col-0 (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Carotenoids are synthesized from 2 molecules of geranylgeranyl-PP (Cunningham and Gantt 1998). The contents and the composition of carotenoids in the vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 mutants were also very similar to those in Col-0 (Supplementary Fig. S2B). The FOLK protein has been suggested to be involved in the regulation of the ABA signaling pathway (Fitzpatrick et al. 2011). ABA is a sesquiterpene lipid synthesized from zeaxanthin, which in turn is derived from geranylgeranyl-PP (Finkelstein 2013); therefore, it was possible that ABA contents were altered in folk-2 or vte5-2 folk-2 plants. However, no differences in ABA levels were observed in vte5-2, folk-2, or vte5-2 folk-2 plants (Supplementary Fig. S2C).

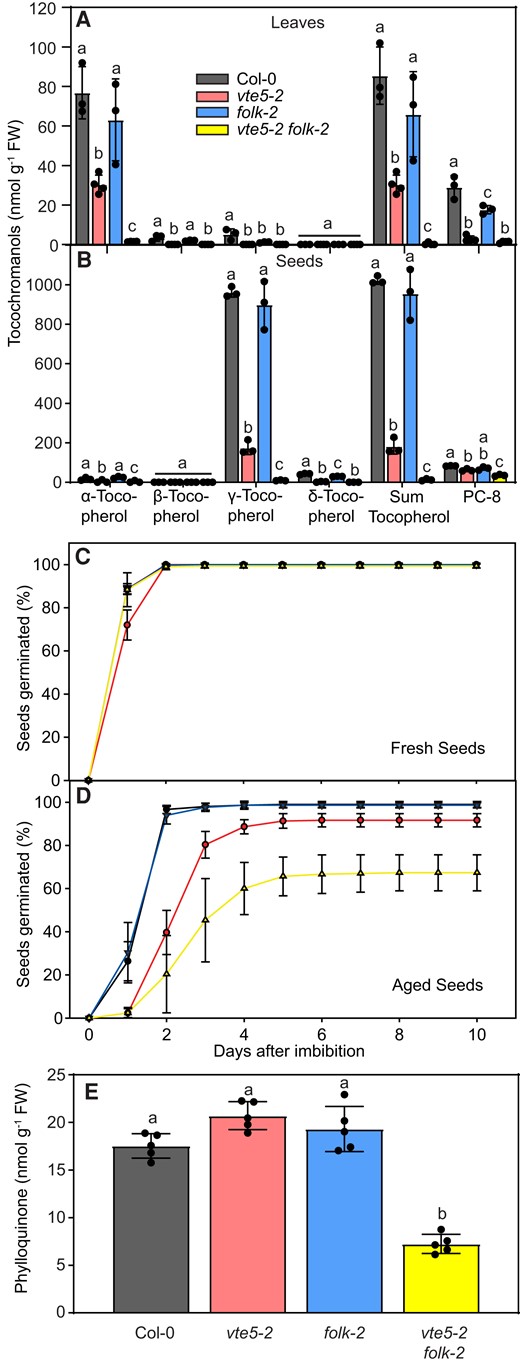

The vte5-2 folk-2 mutant lacks all forms of tocopherol

Tocochromanols were extracted from leaves and seeds of vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 plants and measured by HPLC (Fig. 1, A and B). The sum of all tocopherols was reduced in leaves and seeds of vte5-2 plants to about 30% and 20% of wild-type Col-0 levels, respectively. In the vte5-2 folk-2 leaves and seeds, the total tocopherol level was decreased further to ∼0 nmol g−1 fresh weight (FW). The decrease in tocopherol was found in all tocopherol forms and was most visible for the highly abundant forms of α-tocopherol in leaves and γ-tocopherol in seeds. The amounts of PC-8 were also reduced in leaves and, to a lesser extent, in the seeds of vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants. The tocopherol or PC-8 levels were found to be similar in the folk-2 single mutant leaves or seeds in comparison with Col-0.

Arabidopsis vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 mutant plants are deficient in tocochromanols and phylloquinone. A) Tocochromanols were extracted from leaves of 4-wk-old plants and measured by HPLC. B) Tocochromanols extracted from seeds were measured by HPLC. C) Germination rate of vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 seeds. Germination rates were determined for fresh, dry seeds (stored for 1 mo at 4 °C). Seeds were placed on wet filter papers and after 1 d of stratification, the germination rate was determined every day. D) Germination rate of artificially aged seeds (40 °C, 100% humidity, 72 h). E) Phylloquinone contents in vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 leaves. Phylloquinone was extracted from leaves of 4-wk-old Arabidopsis plants and measured by fluorescence HPLC after postcolumn reduction. Data represent means ± Sd of 3 different plants. Letters within each tocochromanol class indicate significant differences; 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.05.

During HPLC analysis, it remained unclear whether the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant leaves contain extremely low amounts or whether they are completely devoid of tocopherol. To address this question, tocopherols were measured in leaves of vte5-2 folk-2 plants by the highly sensitive LC-MS/MS method. To increase the precursor availability and upregulate tocopherol synthesis, plants were also grown in a medium supplemented with phytol. While α-tocopherol was clearly detected in Col-0, vte5-2, and folk-2 leaves, it was not found in vte5-2 folk-2 leaves with or without supplemented phytol (Supplementary Fig. S3). Therefore, vte5-2 folk-2 leaves were absolutely devoid of tocopherol.

Seed longevity is impaired in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant

Tocopherol-deficient Arabidopsis mutant seeds, including those of vte1, vte2, and vte6 mutants, display a poor germination rate after storage or artificial aging (Sattler et al. 2004; vom Dorp et al. 2015). To unravel whether the tocopherol-deficient vte5-2 folk-2 mutant plants also display reduced seed longevity, vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 seeds were artificially aged by incubating the seeds at high temperature and high humidity (Sattler et al. 2004). While the germination rate of the fresh mutant seeds was similar to that of Col-0 seeds, germination of vte5-2 folk-2 seeds was strongly suppressed after artificial aging and only reached 63% of the Col-0 level (Fig. 1, C and D). The germination rate of vte5-2 seeds after accelerated aging was slightly lower (∼90% after 5 d) in comparison with the same seeds without accelerated aging (∼100%). The germination rates of the aged Col-0 and folk-2 seeds (∼100%) remained unchanged in comparison with their untreated controls. These results correspond with the tocopherol levels in the mutant seeds. Therefore, in analogy with the other tocopherol-deficient mutants, seed longevity of vte5-2 folk-2 seeds is strongly reduced.

Decreased phylloquinone content in vte5-2 folk-2 mutant plants

Similar to tocopherol, phylloquinone carries a side chain derived from phytyl-PP. As tocopherol biosynthesis in the vte5-2 folk-2 line was severely affected, the relevance of FOLK and VTE5 for the biosynthesis of phylloquinone was analyzed. Leaves from vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 lines were extracted and phylloquinone was measured by fluorescence HPLC (Fig. 1E). While the phylloquinone contents were similar in Col-0, vte5-2, and folk-2 plants, it was decreased to ∼40% in the vte5-2 folk-2 double mutant in comparison with that in Col-0. Therefore, in contrast to tocopherol synthesis, phylloquinone synthesis was not completely abolished in the vte5-2 folk-2 double mutant.

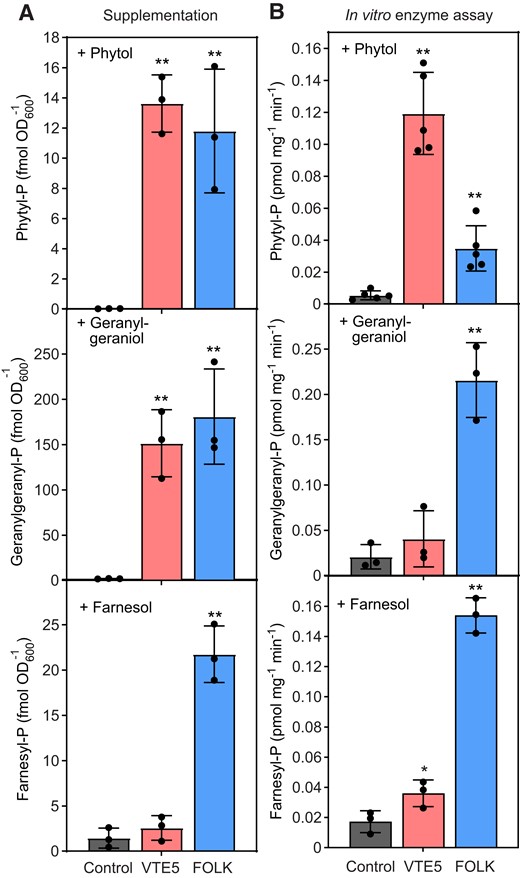

VTE5 and FOLK encode kinases with specificities for phytol, geranylgeraniol, and farnesol

The FOLK and VTE5 coding sequences were heterologously expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Recombinant S. cerevisiae cells were supplemented with phytol, geranylgeraniol, or farnesol, to study the kinase activities of the 2 proteins with the different substrates. Isoprenoid alcohol phosphates were extracted from the cells and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Phytol supplementation resulted in the production of 13.5 and 11.8 fmol OD−1600 phytyl-P in VTE5- and FOLK-expressing cells, respectively (Fig. 2A). The conversion of geranylgeraniol into geranylgeranyl-P was even higher, with 151 and 180 fmol OD600−1 for VTE5 and FOLK, respectively. In addition, FOLK converted farnesol into farnesyl-P (21.7 fmol OD600−1), while the farnesol kinase activity of VTE5 was low (2.6 fmol OD600−1). Therefore, heterologously expressed FOLK protein converted all 3 isoprenoid alcohol kinases into their monophosphates, with the highest activity for geranylgeraniol, while VTE5 was active with phytol and geranylgeraniol.

VTE5 and FOLK display kinase activities with different isoprenoid alcohols. A) Supplementation of phytol, geranylgeraniol, or farnesol to S. cerevisiae cells expressing VTE5 or FOLK. The cDNAs of VTE5, FOLK, or GFP (control) were expressed in S. cerevisiae and the cells cultivated in the presence of 5 mM phytol, geranylgeraniol, or farnesol. Phosphorylation products (phytyl-P, geranylgeranyl-P, and farnesyl-P) were analyzed by LC-MS/MS and calculated as fmol per OD600. B) Isoprenoid alcohol kinase assays with VTE5 and FOLK. Isoprenoid alcohol kinase assays were performed with microsomal fractions of VTE5 and FOLK proteins expressed in S. cerevisiae. The assays included 5 mM of phytol, geranylgeraniol, or farnesol with an equimolar mix of NTPs. Phytyl-P, geranylgeranyl-P, and farnesyl-P were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Data represent the means ± Sd of 3 replicates. Significant differences to control: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, Student t-test. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

To study the in vitro substrate specificities, microsomal proteins were isolated from S. cerevisiae cells after expression of VTE5 or FOLK and incubated with the different substrates, phytol, geranylgeraniol, or farnesol, and an equimolar mixture of ATP, CTP, GTP, and UTP. Isoprenoid alcohol phosphates were extracted and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. VTE5 displayed kinase activities of 0.11, 0.04, and 0.03 pmol mg−1 min−1 with phytol, geranylgeraniol, and farnesol, respectively (Fig. 2B). The activities of FOLK with phytol, geranylgeraniol, and farnesol were 0.03, 0.21, and 0.15 pmol mg−1 min−1, respectively. Therefore, while VTE5 showed kinase activities with phytol and lower activities with geranylgeraniol and farnesol, FOLK displayed moderate kinase activity with phytol, but very high activities with geranylgeraniol and farnesol.

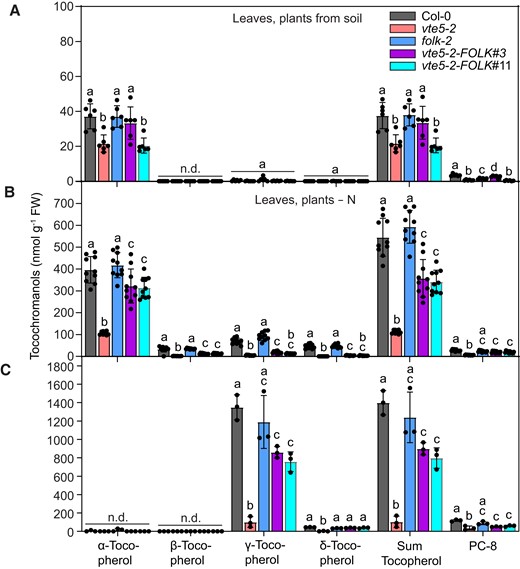

FOLK contributes to in vivo tocopherol synthesis

Because the tocopherol contents in leaves and seeds of the folk-2 mutant were not significantly changed compared with that in Col-0, it remained unclear whether FOLK contributes to tocopherol synthesis in vivo. We reasoned that if both FOLK and VTE5 contribute to tocopherol synthesis, it should be possible to complement the tocopherol deficiency of vte5-2 by strong overexpression of FOLK. Therefore, the FOLK cDNA under the control of the 35S promoter was introduced into the vte5-2 mutant. The transformed plants were screened for the tocopherol contents in leaves and seeds. Only a few transgenic plants (e.g. line vte5-2-FOLK#3) displayed an increased leaf tocopherol content, reaching almost Col-0 levels, but many plants (e.g. line vte5-2-FOLK#11) contained low tocopherol levels similar to the vte5-2 mutant background (Fig. 3A). The plants were grown on nitrogen-deficient medium to stimulate chlorophyll degradation and the phytol kinase pathway. Under these conditions, most plants including vte5-2-FOLK#3 and vte5-2-FOLK#11 showed tocopherol contents that were increased compared with that in vte5-2 plants, albeit without reaching Col-0 levels (Fig. 3B). Next, tocopherols were measured in the seeds. The contents of total tocopherol in vte5-2-FOLK#3 and vte5-2-FOLK#11 seeds were strongly increased compared with that in vte5-2 seeds but did not reach the levels in Col-0 seeds (Fig. 3C). Therefore, strong overexpression of FOLK can partially complement the tocopherol deficiency of the vte5-2 mutant, indicating that FOLK displays functional redundancy with VTE5. The degree of complementation by FOLK is most efficient in leaves of N-deprived plants and in seeds, where the contribution of phytol from chlorophyll degradation and from the kinase pathway to tocopherol synthesis is high, while the complementation is less efficient in leaves of soil-grown plants with lower chlorophyll turnover.

Complementation of tocopherol deficiency in the vte5-2 mutant with FOLK. The FOLK cDNA under the control of the 35S promoter was introduced into the vte5-2 mutant background. Tocochromanols were measured A) in leaves of plants grown on soil, B) grown on a nitrogen-deficient medium, or C) in seeds. Data represent means ± Sd of 3 to 10 replicates of different plants. Letters indicate significant differences for each tocochromonal class; 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.05; n.d., not detectable.

The Arabidopsis mutants vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 accumulate different amounts of isoprenoid alcohol phosphates

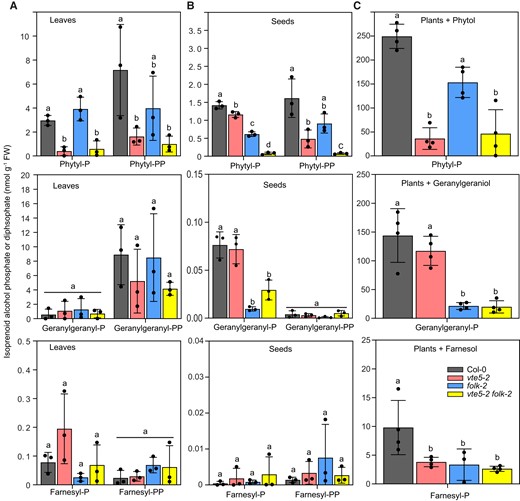

To test the impact of decreased isoprenoid alcohol kinase activities in the vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 mutants on isoprenoid alcohol metabolism, the contents of phytyl-P, geranylgeranyl-P, and farnesyl-P were quantified in leaves and seeds by LC-MS/MS. In leaves, a decrease in phytyl-P and phytyl-PP levels in the vte5-2 and the vte5-2 folk-2 lines by ∼75% compared with the Col-0 level was observed, while phytyl-P and phytyl-PP remained unchanged in folk-2 leaves (Fig. 4A). In seeds, their contents were reduced in all mutants, with the strongest reduction of >90% in vte5-2 folk-2 seeds, compared with that in Col-0 seeds (Fig. 4B). The geranylgeranyl-P and geranylgeranyl-PP contents in vte5-2 and folk-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 leaves remained similar to that in Col-0 leaves, while the geranylgeranyl-PP level in vte5-2 folk-2 leaves was lower than that in Col-0 leaves (Fig. 4A). Similar to the phytyl-P content, the geranylgeranyl-P content was lower in folk-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 seeds than in Col-0 seeds (Fig. 4B). The geranylgeranyl-PP contents in mutant seeds were extremely low and not different from those in Col-0 seeds. The amounts of farnesyl-P and farnesyl-PP in leaves and seeds were very low and not significantly different from those in Col-0 seeds (Fig. 4, A and B).

Isoprenoid alcohol phosphate contents in leaves and seeds of the Arabidopsis vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 mutants. A) Isoprenoid alcohol monophosphates (-P) and diphosphates (-PP) in leaves of 4-wk-old Arabidopsis plants grown on MS medium. B) Isoprenoid alcohol monophosphates and diphosphates in seeds. C) Leaf isoprenoid alcohol phosphate contents after supplementation with phytol, geranylgeraniol, or farnesol. Three-week-old plants were incubated in liquid culture supplemented with 5 mM phytol, geranylgeraniol, or farnesol for 24 h. Phytyl-P, phytyl-PP, geranylgeranyl-P, geranylgeranyl-PP, farnesyl-P, and farnesyl-PP were measured by LC-MS/MS. Data represent means ± Sd of 3 replicates of different plants. Letters indicate significant differences for each compound class; 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.05.

Phytol, geranylgeraniol, and farnesol were supplemented to the plants to increase the production of endogenous isoprenoid alcohol phosphates. After growth in the presence of phytol or geranylgeraniol, the plants were still green, but plants grown in the presence of farnesol turned brown, in agreement with the high toxicity of farnesol observed previously (Hemmerlin and Bach 2000). The contents of isoprenoid alcohol phosphates measured by LC-MS/MS in plants after feeding with free alcohols were ∼100-fold higher compared with that in leaves of soil-grown plants (Fig. 4, A and C). After growth in the presence of phytol, the phytyl-P content was lower in vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants in comparison with that in Col-0 plants (Fig. 4C), but it was still higher compared with that in nonsupplemented vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants, indicating that vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants harbor a residual capacity for phytyl-P synthesis. Supplementation with geranylgeraniol revealed that geranylgeranyl-P production in folk-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants was decreased in comparison with that in Col-0 plants, but production was not reduced in vte5-2 plants. Because the seedlings supplemented with farnesol were highly stressed and contained low farnesyl-P contents, no conclusive results for farnesyl-P levels could be obtained, although the amounts of farnesyl-P seemed to be lower in all mutant leaves than in Col-0 leaves. The supplementation experiments showed that phytol feeding resulted in a strong increase in phytyl-P production in folk-2 plants compared with that in vte5-2 plants, while geranylgeraniol feeding caused a strong increase in geranylgeranyl-P in vte5-2 plants compared with that in folk-2 plants, indicating that VTE5 displays higher activity with phytol and FOLK with geranylgeraniol. Furthermore, the vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants display a residual capacity for the phosphorylation of supplemented phytol.

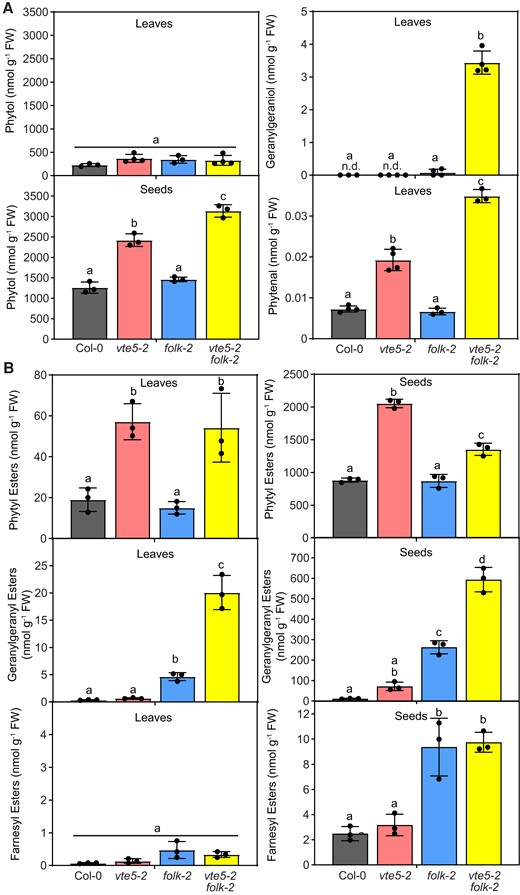

Phytol, geranylgeraniol, phytenal, and fatty acid isoprenoid alcohol esters accumulate in Arabidopsis vte5-2 folk-2 mutant plants

To address the question if the decrease in isoprenoid alcohol kinase activity in vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 mutants leads to the accumulation of the corresponding alcohols, phytol, geranylgeraniol, and farnesol were analyzed in leaves and seeds by GC-MS after silylation (Fig. 5A). The amounts of free phytol were not significantly altered in leaves, but they were increased in vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 seeds in comparison with levels in Col-0 seeds. Free geranylgeraniol was not detectable in seeds of any line. In the leaves, geranylgeraniol was not detectable in Col-0 and vte5-2 plants, but it was found in folk-2 leaves and at high levels in vte5-2 folk-2 leaves. The farnesol contents in leaves or seeds were below the detection limit. We also measured the amounts of phytenal, the degradation product of phytol in the leaves by LC-MS/MS (Gutbrod et al. 2021). Elevated levels of phytenal were detected in vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 leaves in comparison with that in Col-0 leaves, but the amounts were in the range of 0.01 to 0.03 nmol g−1 FW, much lower compared with the amounts of phytol in leaves (200 to 400 nmol g−1 FW) (Fig. 5A).

Isoprenoid alcohols, phytenal, and fatty acid isoprenoid alcohol esters in leaves and seeds of Arabidopsis vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 plants. A) Isoprenoid alcohols were extracted from leaves or seeds and analyzed by GC-MS after silylation. Only phytol and geranylgeraniol were detected in leaves and only phytol in the seeds, while farnesol in leaves and geranylgeraniol and farnesol in seeds were below the detection limit. Phytenal was extracted from leaves, derivatized with methoxylhydroxylamine, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. B) FAPEs, geranylgeranyl esters, and farnesyl esters were determined by direct infusion Q-TOF MS/MS in leaves or seeds of soil-grown plants. The composition of isoprenoid alcohol esters is provided in Supplementary Fig. S4. Data represent means ± Sd of 3 to 4 replicates. Letters indicate significant differences for each compound class; 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.05.

Phytol is esterified to acyl groups and thereby converted into FAPE, which can be transiently deposited in the plastoglobules of chloroplasts, to reduce the toxicity of free phytol (Ischebeck et al. 2006; vom Dorp et al. 2015). To address the question if the accumulation of free isoprenoid alcohols in vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 plants results in an increased production of fatty acid isoprenoid alcohol esters, phytyl esters, geranylgeranyl esters, and farnesyl esters were measured by direct infusion MS/MS (vom Dorp et al. 2015). The total amounts of phytyl esters were increased in vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 leaves and seeds in comparison with in Col-0 leaves and seeds (Fig. 5B). The concentration of geranylgeranyl esters was very low in Col-0 and vte5-2 leaves and seeds. In folk-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 leaves and seeds, geranylgeranyl esters were strongly increased compared with levels in Col-0 leaves and seeds. Farnesyl esters were almost undetectable in leaves and seeds, with no significant differences in the leaves, and strong increases in folk-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 seeds in comparison with the amounts in Col-0 seeds. In general, the total amount of isoprenoid alcohol esters was much higher in the seeds compared with that in leaves. In agreement with previous studies (Gaude et al. 2007), the main fatty acid in phytyl esters in leaves was 16:3 (Supplementary Fig. S4A). In seeds, phytol was mainly esterified to 18:2 and 18:3, followed by 16:3 and 16:0 (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Geranylgeranyl esters, which were highly abundant in vte5-2 folk-2 leaves and seeds, were mainly esterified with 16:0, 16:3, 18:3, and 20:0 in leaves and with 18:2 and 18:3 in seeds. Farnesyl esters containing 18:3, 20:0, and 22:0 were increased in the folk-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 leaves and those with 18:2 and 18:3 in the seeds of folk-2 and vte5-2 folk-2.

Supplementation with homogentisate leads to tocotrienol accumulation in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant

Previous strategies to elevate the tocopherol content in Arabidopsis included the increase in the availability of the precursor homogentisate in transgenic plants.

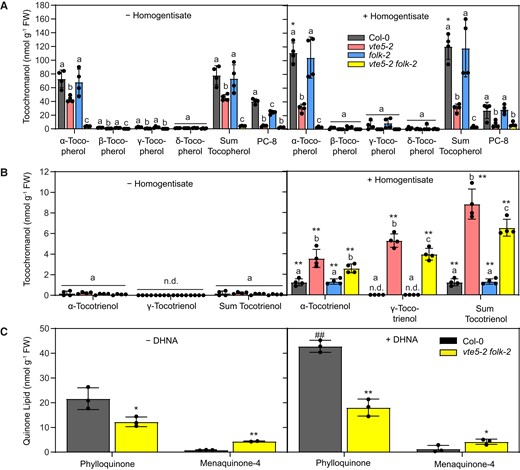

Tocotrienols accumulated in Arabidopsis containing elevated homogentisate levels in addition to tocopherols (Rippert et al. 2004; Karunanandaa et al. 2005; Tzin et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2013). Tocotrienols are normally absent, as Arabidopsis lacks homogentisate geranylgeranyl transferase (HGGT) that is responsible for tocotrienol synthesis in monocots (Cahoon et al. 2003). To test whether exogenous addition of homogentisate can also lead to stimulation of tocopherol or tocotrienol synthesis, Col-0, vte5-2, folk-2, or vte5-2 folk-2 plants were grown on a medium containing homogentisate. In agreement with the previous genetic experiments, the α-tocopherol content was increased in Col-0 after growth in the presence of homogentisate (Fig. 6A). The tocopherol content was lower in vte5-2 plants, and it was virtually absent from vte5-2 folk-2 plants compared with the amount in Col-0 plants after growth on control or homogentisate-containing medium. Therefore, homogentisate is limiting for tocopherol synthesis in Col-0, but in vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants, tocopherol synthesis is restricted by a limitation in phytyl-PP. Only trace amounts of tocotrienols were detected in all plants when grown on a homogentisate-free medium. When grown on homogentisate medium, α-tocotrienol accumulated in all lines, and γ-tocotrienol was found in vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants (Fig. 6B). The vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 mutants grown on homogentisate contained higher amounts of α-tocotrienol and γ-tocotrienol compared with Col-0. The presence of α-tocotrienol and γ-tocotrienol in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant was unexpected, since these plants are completely devoid of tocopherols (Figs. 1 and 6A; Supplementary Fig. S3). To confirm the results obtained by HPLC measurements, tocotrienols were measured in vte5-2 folk-2 leaves using the highly sensitive LC-MS/MS method. While α-tocotrienol and a peak for γ-tocotrienol were identified in vte5-2 folk-2 plants after homogentisate supplementation, the 2 tocotrienols were not detectable without homogentisate feeding (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Tocochromanol and phylloquinone/menaquinone-4 contents in vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 plants after homogentisate or DHNA supplementation. A) Two-week-old Arabidopsis plants were grown on a control medium (− homogentisate) or medium supplemented with 5 mM homogentisate (+ homogentisate) for 9 d. Tocopherols and PC-8 were extracted from leaves and measured by HPLC. B) Tocotrienol contents in plants grown on control or on homogentisate-supplemented medium. C) Two-week-old plants were transferred to solid medium containing 2.5 mM DHNA (+ DHNA) or without DHNA (− DHNA) and grown for another 9 d. Phylloquinone and menaquinone-4 contents were measured by HPLC with postcolumn reduction. Data represent means ± Sd of 3 to 4 replicas of different plants. A, B) Letters indicate significant differences for each compound class; 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test, P < 0.05. Asterisks indicate differences between treatments; Student t-test: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. C) Significant differences to Col-0; **P < 0.01, Student t-test. Significant differences between treatments; ##P < 0.01, Student t-test. n.d., not detectable.

Menaquinone-4 synthesis in vte5-2 folk-2 plants after DHNA supplementation

We considered the possibility that in analogy with the increase in tocopherol/tocotrienol synthesis observed after homogentisate supplementation, it would be possible to enhance the production of phylloquinone by feeding the plants with the corresponding head group precursor. The attachment of the alternative geranylgeranyl group to DHNA by MenA would result in the production of menaquinone-4. Menaquinone-4, however, is barely produced in plants, but it is an abundant quinone lipid in many bacteria. The content of phylloquinone was strongly increased after DHNA supplementation in Col-0 plants, and in vte5-2 folk-2 plants, it still remained at ∼40% of the Col-0 levels (Fig. 6C). Menaquinone-4 was detected in vte5-2 folk-2 plants with or without DHNA feeding at ∼3-fold higher levels than that in Col-0 plants, while it remained very low in Col-0. Therefore, although the capacity for phylloquinone synthesis is compromised in vte5-2 folk-2 plants, the double mutant plants can synthesize low amounts of the unusual quinone lipid menaquinone-4.

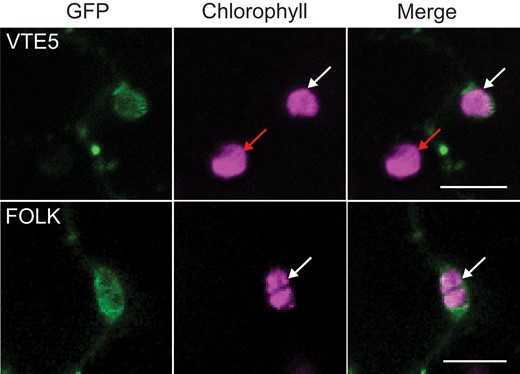

Subcellular localization of VTE5 and FOLK

The subcellular localization of VTE5 and FOLK was analyzed to address the question whether the 2 proteins are found in the chloroplast as expected based on their involvement in the metabolism of phytol, tocopherol, and phylloquinone. VTE5 and FOLK were previously predicted to carry N-terminal transit peptides for the chloroplast, but the subcellular localization was never experimentally tested (Valentin et al. 2006). VTE5 and FOLK were fused to the N-terminus of eGFP and the fusion protein transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves (Fig. 7). Analysis by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) revealed that GFP signals in leaves expressing the VTE5-eGFP or FOLK-eGFP constructs colocalized with chlorophyll fluorescence in chloroplasts (Fig. 7). The chloroplast localization is in line with the predicted localization of VTE5 and FOLK (suba5.live database). Also, VTE5 was previously identified in the proteome of Arabidopsis chloroplasts by mass spectrometry (Zybailov et al. 2008). The chloroplast localization of VTE5 and FOLK is in agreement with their function in tocopherol biosynthesis. Other enzymes involved in tocopherol synthesis, VTE2, VTE3, and VTE4, were localized to subfractions of spinach (Spinacia oleracea) chloroplasts (Soll et al. 1980), while tocopherol cyclase (VTE1) was localized to plastoglobules (Vidi et al. 2006; Spicher and Kessler 2015), and YFP-VTE6 fusion constructs were found in chloroplasts of transformed protoplasts (vom Dorp et al. 2015).

Subcellular localization of VTE5 and FOLK. Leaves of N. benthamiana plants were infiltrated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells carrying the constructs pLH9000-VTE5-eGFP (top) or pLH9000-FOLK-eGFP (bottom panels). After 4 d, leaves were analyzed by CLSM. Colocalization of the GFP fluorescence and chlorophyll autofluorescence is indicated with white arrows. Red arrows indicate chloroplasts in untransformed cells, which lack green fluorescence. The absence of green fluorescence from these chloroplasts indicates that there was no overflow of chlorophyll fluorescence to the green channel. Bars = 10 µm.

Discussion

Isoprenoid alcohol phosphates are important precursors for the biosynthesis of photosynthetic pigments and electron carriers (chlorophyll, carotenoids, phylloquinone, and plastoquinone), phytohormones (ABA), and tocochromanols in the chloroplasts. It has been demonstrated that free phytol from chlorophyll degradation can be remobilized by phosphorylation and that phytyl-PP derived from the kinase pathway is employed for the synthesis of tocopherol and phylloquinone. We show here that the previously identified FOLK represents an additional enzyme of tocopherol and phylloquinone synthesis. While VTE5 is most active with phytol, FOLK shows the highest activities with geranylgeraniol and farnesol but is also active with phytol (Figs. 2 and 8).

Deficiency in isoprenoid alcohol kinase activity in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant has a minor impact on growth, photosynthesis, and the contents of chlorophyll, carotenoids, and ABA

The vte5-2 folk-2 plants are viable and grow normally on soil (Supplementary Fig. S1). The chloroplast ultrastructure was not changed, and the photosynthetic quantum yield was unaffected. Therefore, FOLK and VTE5 are not required for normal photosynthesis or structural integrity of the chloroplasts. Chlorophyll is synthesized by chlorophyll synthase from chlorophyllide and geranylgeranyl-PP (Rüdiger et al. 1980). Geranylgeranyl-chlorophyll is reduced to phytyl-containing chlorophyll by GGR (Keller et al. 1998). Carotenoids are produced by condensation of 2 geranylgeranyl-PP molecules, and the phytohormone ABA is derived from the carotenoid zeaxanthin via a dioxygenase reaction. The levels of chlorophyll, carotenoids, or ABA were similar in vte5-2 folk-2 and Col-0 plants (Supplementary Fig. S2). Therefore, geranylgeranyl-PP required for the synthesis of chlorophyll, carotenoids, or ABA is not derived from the phosphorylation of geranylgeraniol by VTE5 or FOLK but directly from the MEP pathway. Based on an ABA-hypersensitive phenotype of folk-2 plants, FOLK was postulated to be involved in ABA signaling (Fitzpatrick et al. 2011). The finding that ABA contents are not changed in folk-2 or vte5-2 folk-2 plants indicates that FOLK is not involved in ABA synthesis or homeostasis. Mutations in the Arabidopsis gene-encoding farnesylcysteine lyase also cause an ABA-hypersensitive phenotype, suggesting that alterations in the turnover of farnesylated proteins or farnesol recycling are linked to ABA signaling (Crowell et al. 2007).

Isoprenoid alcohols and their metabolites accumulate in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant

In line with the deficiency in kinase activity, free isoprenoid alcohols increased in the vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 mutants (Fig. 5A). In general, the chlorophyll turnover/degradation and the VTE5/FOLK kinase pathway are much more active during seed development compared with that in green leaves, because Arabidopsis embryos are green during early stages of development, and during later stages, chlorophyll is degraded, and the released phytol is converted into phytyl-PP for tocopherol synthesis. In green leaves, chlorophyll turnover is less pronounced. Only after stimulating chlorophyll degradation by stress (e.g. nitrogen deprivation), the VTE5/FOLK kinase pathway becomes more relevant. This results in higher steady-state levels of phytol in seeds and nitrogen-deprived leaves, compared with green leaves (Fig. 5A). Phytol accumulated in vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 seeds, and geranylgeraniol was elevated in vte5-2 folk-2 leaves, but it was not detectable in Col-0 and vte5-2 plants. Free farnesol could not be detected in leaves or seeds of any plant, presumably because of its high toxicity (Hemmerlin and Bach 2000). The amounts of downstream metabolites were increased in the mutants, indicating that isoprenoid alcohols were metabolized to prevent their accumulation. Phytenal, a catabolite of phytol, accumulated in vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants, suggesting that a certain proportion of phytol was degraded (Gutbrod et al. 2021). The effects of the vte5-2 or folk-2 mutations on isoprenoid lipids and metabolites were more pronounced in seeds than leaves, e.g. with higher accumulation of phytyl esters and geranylgeranyl esters in mutant seeds (Fig. 5B). The amounts of isoprenoid alcohol mono- and diphosphates were far lower compared with all other isoprenoid metabolites, presumably because they are very sensitive to small changes in the different pathways. Therefore, the supplementation experiments with phytol, geranylgeraniol, and farnesol provided more robust results revealing strong increases in isoprenoid alcohol phosphates in Col-0 that were partially suppressed in the mutants (Fig. 4C).

The vte5-2 mutation suppressed phytyl-P production after phytol feeding compared with Col-0, while phytyl-P production in the folk-2 mutant was similar to Col-0. On the other hand, the folk-2 mutation suppressed the geranylgeranyl-P production after geranylgeraniol feeding compared with Col-0, while geranylgeranyl-P production was less affected in vte5-2.

This is in agreement with the finding that VTE5 is most active with phytol and FOLK with geranylgeraniol. These results are also reflected in the accumulation of phytyl esters or geranylgeraniol esters, which take up the free isoprenoid alcohols, in vte5-2 or folk-2 plants (Fig. 5B). The differential accumulation of phytyl esters and geranylgeranyl esters in the mutants presumably reflects the in planta activity of VTE5 and FOLK for phytol and geranylgeraniol. VTE5 is most active with phytol and has considerable activity with geranylgeraniol. FOLK is most active with geranylgeraniol and has low activity with phytol. Therefore, phytyl esters are increased (taking up free phytol) in vte5-2 plants, but they are not changed in folk-2 plants, and there is no additive effect in vte5-2 folk-2 plants. On the other hand, geranylgeranyl esters show a minor increase in vte5-2 plants (at least in seeds) more strongly in folk-2 plants, and there is an additive effect in vte5-2 folk-2 plants. While phytyl esters have been described in plants, mosses, and algae before (Krauß and Vetter 2018), geranylgeranyl and farnesyl esters have rarely been found. Geranylgeranyl esters were described in spores of the moss Polytrichum commune and in spruce (Picea abies) (Liljenberg and Karunen 1978; Nagel et al. 2014). Farnesyl esters were identified in the microalga Botryococcus braunii (Inoue et al. 1994). Similar to phytyl esters, geranylgeranyl and farnesyl esters presumably represent sinks for the intermediate storage of geranylgeraniol and farnesol, respectively.

Tocotrienol and menaquinone-4 production in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant

Arabidopsis contains tocopherols rather than tocotrienols. Overexpression of p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase, catalyzing the last step of homogentisate biosynthesis, leads to an increase in homogentisate and tocopherol synthesis (Tsegaye et al. 2002). The addition of homogentisate to cell cultures of sunflower (Helianthus annuus) or tobacco (N. tabacum) resulted in an increase in α-tocopherol by ∼30% (Caretto et al. 2004; Harish et al. 2013). Supplementation of homogentisate to Col-0 plants also caused an increase in the amounts of tocopherol (Fig. 6A) and led to the production of tocotrienols in Col-0, vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 plants. Interestingly, the vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 plants produced even higher amounts of tocotrienols compared with Col-0 plants after homogentisate feeding, while tocopherols were still completely absent from vte5-2 folk-2 plants. Arabidopsis contains only 1 homogentisate phytyltransferase (HPT) specific for phytyl-PP but is devoid of geranylgeranyl-PP-specific HGGT (Yang et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2013; Cahoon et al. 2003). It is known that in the presence of excess amounts of homogentisate the HPT enzyme also employs geranylgeranyl-PP for tocotrienol production (Karunanandaa et al. 2005).

Phylloquinone is produced from phytyl-PP and DHNA by action of the prenyltransferase MenA. Menaquinone-4, which contains an unsaturated side chain derived from geranylgeranyl-PP, is an electron carrier in bacteria but is absent from plants (Schurgers and Vermeer 2000). In accordance, phylloquinone, but not menaquinone-4, was detected in Arabidopsis Col-0 leaves, even after supplementation with DHNA (Fig. 6C). While the phylloquinone content was decreased in vte5 folk-2 plants, the plants produced low amounts of menaquinone-4 in the presence or absence of DHNA. These results suggest that similar to HPT during tocotrienol synthesis, MenA can also employ geranylgeranyl-PP in addition to phytyl-PP for menaquinone-4 synthesis in vte5-2 folk-2 plants (Fig. 8).

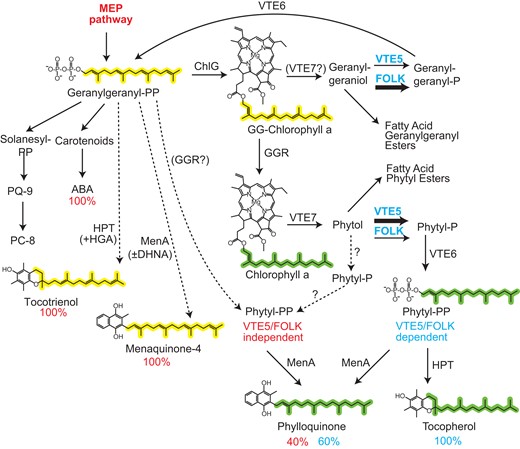

Geranylgeranyl-PP from the MEP pathway and phytyl-PP contribute to isoprenoid synthesis in the chloroplast. Geranylgeranyl-PP is derived from the isoprenoid de novo synthesis pathway (MEP pathway) and is employed for the synthesis of carotenoids, ABA, and geranylgeranyl-chlorophyll. GG-chlorophyll is converted into chlorophyll by GGR. Hydrolysis of GG-chlorophyll and chlorophyll gives rise to the release of geranylgeraniol and phytol, respectively. Geranylgeraniol and phytol are phosphorylated by VTE5 or FOLK. Geranylgeranyl-PP and phytyl-PP are derived from a second phosphorylation by VTE6. The percent numbers indicate the relative contribution of geranylgeranyl-PP or phytyl-PP to the different isoprenoids. During homogentisate (HGA) supplementation, or in the presence or absence of DHNA, tocotrienols and menaquinone-4 are produced in vte5-2 folk-2 plants (dashed arrows). Phylloquinone is produced not only from phytyl-PP derived from the kinase reactions but also from geranylgeranyl-PP from the MEP pathway, which is potentially converted into phytyl-PP by a side reaction of GGR (dashed arrow).

Dependency of the synthesis of tocopherol and PC-8 on the VTE5/FOLK kinase pathway

In vitro enzyme assays with recombinant FOLK revealed kinase activity with phytol and higher activities with farnesol and geranylgeraniol (Fig. 2B). VTE5 displayed high kinase activity with phytol but low activities with geranylgeraniol and farnesol. Supplementation experiments confirmed that VTE5 and FOLK can phosphorylate phytol and geranylgeraniol and FOLK, in addition, was active with farnesol. The production of alcohol phosphates was in general higher during the supplementation experiments, and the relative amounts of alcohol phosphates differed compared with those in the in vitro assays (Fig. 2A). This might be due to the fact that S. cerevisiae harbors endogenous pools and enzymes of isoprenoid alcohol metabolism, which can affect the supplementation experiments.

The vte5-2 folk-2 double mutant completely lacks tocopherols, while the folk-2 mutant has similar tocopherol levels as Col-0 (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. S3). Therefore, both FOLK and VTE5 contribute to the production of phytyl-P for tocopherol synthesis. FOLK can phosphorylate phytol, providing phytyl chains for tocopherol synthesis, in addition to VTE5 (Fig. 2). It is also possible that FOLK and VTE5 phosphorylate geranylgeraniol and that geranylgeranyl-P or geranylgeranyl-PP produced by VTE6 are reduced to phytyl-P or phytyl-PP by GGR for tocopherol synthesis. In any case, the levels of phytyl-PP would be decreased in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant, in agreement with the data shown in Fig. 4.

The strong overexpression of FOLK in the vte5-2 mutant confirmed that FOLK is an authentic in planta enzyme of tocopherol synthesis. The tocopherol deficiency of vte5-2 seeds and of vte5-2 leaves from plants grown on soil or exposed to nitrogen deprivation was partially complemented by ectopic expression of FOLK. This result confirms that the activity of the endogenous FOLK enzyme is too low to compensate for the loss of tocopherol in the vte5-2 mutant but that strong overexpression of FOLK is sufficient for complementation. Therefore, FOLK and VTE5 have overlapping functions during phytol phosphorylation in planta.

Similar to tocopherol, the amounts of PC-8 were strongly reduced in vte5-2 leaves and virtually absent from vte5-2 folk-2 leaves (Figs. 1A and 6A). PC-8 levels were decreased, but it was still detectable in vte5-2 and vte5-2 folk-2 seeds. Therefore, the production of solanesyl diphosphate (solanesyl-PP), the prenyl precursor for PC-8 synthesis, depends to a large extent on the VTE5/FOLK pathway in leaves but only to a low extent in seeds. In conclusion, in nonphotosynthetic tissues like seeds, geranylgeranyl-PP is presumably employed for solanesyl-PP synthesis independent of VTE5/FOLK, while in photosynthetic tissues like leaves, geranylgeraniol needs to be activated by the VTE5/FOLK pathway to serve as substrate for solanesyl-PP synthesis.

Phylloquinone is only partially synthesized via the VTE5/FOLK kinase pathway

Phylloquinone is required for the stability of PSI (Wang et al. 2017), and it is additionally found in plastoglobules (Lohmann et al. 2006). In contrast to tocopherol, which is completely absent, phylloquinone levels in vte5-2 folk-2 leaves were reduced to ∼40% of the Col-0 level, and phylloquinone was not decreased in the vte5-2 or folk-2 single mutants. Presumably, the plastoglobules of the vte5-2 folk-2 double mutant are preferentially depleted from phylloquinone, and the remaining amount is relocalized to the thylakoids to stabilize PSI. The presence of phylloquinone in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant shows that it is not entirely synthesized via the VTE5/FOLK kinase pathway. In contrast, phylloquinone was completely absent from the vte6 mutant (Wang et al. 2017). In the vte6 mutant, which shows a strong chlorotic phenotype, not only the levels of tocopherol and phylloquinone but also chlorophyll and carotenoids were strongly decreased. The simultaneous decrease of the plastidial isoprenoid lipids might be due to the pleiotropic effects of the vte6 mutation on general chloroplast metabolism.

The fact that the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant can still produce phylloquinone reveals that a “safety” pathway for the production of the phytyl chain in phylloquinone, but not for tocopherol, exists in Arabidopsis. It is possible that (i) a small amount of phytyl-PP might be produced in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant via the reduction of geranylgeranyl-PP from the MEP pathway by GGR (Fig. 8) (Keller et al. 1998). GGR might also display low reductase activity with geranylgeranyl-P that would be converted into phytyl-P and into phytyl-PP by VTE6, or GGR might be able to directly reduce low amounts of menaquinone-4 in the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant. Different studies provided evidence that GGR from Arabidopsis converts geranylgeranyl-chlorophyll to chlorophyll, similar to GGR from Rhodobacter that reduces geranylgeranyl-bacteriochlorophyll to bacteriochlorophyll (Addlesee and Hunter 1999). In barley (Hordeum vulgare) leaves exposed to darkness or green light, partially reduced forms of geranylgeranyl-chlorophyll are found that are reduced to chlorophyll, presumably by GGR, during greening (Domanskii et al. 2003; Karlický et al. 2021). However, the activity of GGR with geranylgeranyl-PP is less clear. Interestingly, GGR enzymes from archaea display broad substrate specificity because they can reduce the 2 geranylgeranyl moieties of digeranylgeranyl glycerophospholipids in the membranes and presumably also geranylgeranyl-PP to phytyl-PP (Murakami et al. 2007). In an alternative scenario (ii), Arabidopsis might contain a third phytol/geranylgeraniol kinase in addition to VTE5 and FOLK, which produces phytyl-P for the synthesis of phylloquinone, but not of tocopherol (Fig. 8). This scenario would be in line with the finding that supplementation of phytol or geranylgeraniol to the vte5-2 folk-2 mutant resulted in the accumulation of phytyl-P and geranylgeranyl-P, respectively, suggesting that the double mutant contains another kinase activity (Fig. 4C). This additional kinase cannot be related to VTE5 or FOLK because the Arabidopsis genome does not harbor further kinase sequences related to VTE5 and FOLK (Valentin et al. 2006). In both scenarios, an additional phytyl-PP pool might exist separated from tocopherol synthesis and only available for phylloquinone synthesis, possibly mediated by substrate channeling.

Materials and methods

Plants and plant cultivation

The Arabidopsis (A. thaliana) mutant plants vte5-2 (At5g04490, pst12490, line 11-5074-1, RIKEN, Japan) and folk-2 (At5g58560, SALK_123564, Nottingham Arabidopsis Seed Centre, Nottingham, UK) were described previously (vom Dorp et al. 2015; Fitzpatrick et al. 2011). Homozygous vte5-2 plants were identified by PCR using primers for the genomic locus (bn772 and bn771) or for the insertion (bn772 and bn232) (Supplementary Table S1). Plants homozygous for folk-2 were screened by PCR using the oligonucleotides bn2853 and bn2854 for the genomic locus and bn2854 and bn78 for the insertion. The 2 lines vte5-2 and folk-2 were crossed, and double homozygous plants were selected in the F2 generation by PCR.

Seeds were germinated on synthetic MS medium containing 1% (w/v) sucrose and 0.8% (w/v) agarose (Murashige and Skoog 1962). Plants were grown (16-h light, 150 µmol m−2 s−1), at 22 °C and 55% relative humidity. After 2 wk, Arabidopsis plants were transferred to fresh MS medium or to pots with soil (Einheitserde Typ P, Patzer Erden GmbH, Sinntal-Altengronau, Germany; containing 33% vermiculite).

For supplementation experiments with alcohols, 3-wk-old plants were transferred to flasks containing 20 mM MES-KOH (pH 6.5) supplemented with 5 mM phytol, 5 mM farnesol, or 5 mM geranylgeraniol. After 24 h incubation with gentle shaking, under long-day conditions, plants were harvested for lipid analysis.

For homogentisate or DHNA supplementation, 10- to 14-d-old plants were transferred to fresh medium containing 1% (w/v) sucrose, 0.8% (w/v) agarose, and 5 mM homogentisate (Tokyo Chemical Industry) or 2.5 mM DHNA (Alfa Aesar) and grown for up to 10 more days. Media containing homogentisate or DHNA turned brown or black, respectively, after several days due to polycondensation, as previously observed with genetically engineered Synechocystis cells accumulating homogentisate (Karunanandaa et al. 2005).

Heterologous expression of VTE5 and FOLK in S. cerevisiae

Arabidopsis Col-0 leaf mRNA was used for cDNA synthesis (RevertAid RT Reverse Transcription, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Coding sequences were amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotides bn4161/bn4162 (VTE5) and bn4163/bn4164 (FOLK), introducing PstI and SalI restriction sites. The PCR products were cloned into pJet1.2 (Thermo Scientific) and then into the PstI and SalI sites of pDR196 (Rentsch et al. 1995). The constructs were introduced into S. cerevisiae BY4741 for protein expression. S. cerevisiae cells harboring the VTE5 or FOLK constructs were grown in a synthetic dextrose (SD) medium lacking uracil at 28 °C and harvested by centrifugation. For in vivo isoprenoid alcohol supplementation, S. cerevisiae cell pellets were resuspended in 5-ml SD minus uracil medium and supplemented with 5 mM phytol, geranylgeraniol, or farnesol (vom Dorp et al. 2015). Cells were incubated for 3 h at 28 °C, harvested by centrifugation, and isoprenoid alcohol phosphates were extracted. For in vitro kinase assays, S. cerevisiae cell pellets were washed with 5-ml PBS, resuspended in homogenization buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 200 mM sucrose; 1 mM EDTA), and homogenized with glass beads in a Precellys homogenizer (Bertin Instruments, Frankfurt). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (3 min, 4,000 × g, 4 °C), and microsomal membranes were obtained from the supernatant by ultracentrifugation (1 h, 60,000 × g, 4 °C). Microsomal pellets were resuspended in 1-ml homogenization buffer. The kinase assay was performed in a final volume of 100 µl with 83-µl assay buffer (0.25%, w/v, CHAPS, 20 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Na-orthovanadate), 2 µl of nucleotide mix (10 mM each of ATP, CTP, GTP, and UTP in water), and 5 µl of 10 mM phytol, geranylgeraniol, or farnesol in ethanol. The assay was started by adding 10 µl of microsomal protein (200 µg) and incubated at 30 °C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by freezing in liquid nitrogen. Isoprenoid alcohol phosphates were extracted and measured by LC-MS/MS.

Complementation of the vte5-2 mutant with FOLK

The full-length sequence of FOLK was amplified from Arabidopsis Col-0 leaf cDNA using the primers bn4165/bn4166, introducing BsaI sites for Golden Gate cloning. The PCR product was cloned into the binary Golden Gate vector pBin35S-GG-DsRed, a derivative of pBinGlyRed1 (Edgar Cahoon, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA). The construct pBin35S:FOLK-GG-DsRed was introduced into Agrobacterium and then transferred into the Arabidopsis vte5-2 mutant by floral dipping.

Subcellular localization

The full-length VTE5 and FOLK sequences lacking the stop codons were amplified by PCR from first-strand cDNA of Arabidopsis leaves using the oligonucleotides bn3203/bn3205 and bn3173/bn3174, thereby introducing SpeI/BamHI and XbaI/BamHI restriction sites, respectively. The eGFP sequence was amplified from the construct pJet-VTE6-eGFP using bn1280 and bn1281 (vom Dorp et al. 2015), thereby adding BamHI and SalI sites. The PCR products were ligated into pJet1.2. Next, VTE5 and FOLK sequences were released from pJet1.2 with PstI and BamHI and ligated into the same sites of the pJet-eGFP construct, thus generating the VTE5-eGFP and FOLK-eGFP fusion constructs. The binary vector pLH9000-eGFP-WSD6 harboring the 35S promoter (Patwari et al. 2019) was digested with SalI and SpeI and used for the ligation with the VTE5-eGFP construct released from pJet1.2. Similarly, the FOLK-eGFP sequence was released from pJet1.2 after digestion with XbaI/SalI and ligated into pLH9000-eGFP-WSD6. The constructs pLH9000-VTE5-eGFP and pLH9000-FOLK-eGFP were transferred into Agrobacterium. Leaves from N. benthamiana were infiltrated with Agrobacterium cells harboring the pLH9000-VTE5-eGFP or pLH9000-FOLK-eGFP constructs, together with cells containing the pMP19 plasmid (Voinnet et al. 2000). The expression and subcellular localization of the eGFP fusion constructs were recorded by CLSM at 4 d after infiltration (LSM 780; Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Fluorescence was detected with a 40× lens (C-Apochromat 40×/1.2-W Korr) after excitation at 488 nm and emission at 517 to 561 nm (eGFP) and 686 to 735 nm (chlorophyll).

Seed longevity

Seed longevity was studied by determination of the germination rate after accelerated aging for 72 h at 40 °C and 100% relative humidity (Sattler et al. 2004). Seeds were placed on filter paper soaked with tap water, and germination of seeds was defined as the time point when the root emerged from the seeds as observed with a binocular. Germination was recorded every day for 10 d.

Chlorophyll fluorescence and electron microscopy

Chlorophyll fluorescence was measured by PAM fluorometry using a Junior-PAM (Walz, Effeltrich). Plants were dark adapted for 60 min prior to measurements. Leaves were exposed for 5 min to light intensities of 150, 500, and 900 µmol m−2 s−1. The quantum yield of PSII was calculated according to the formula (Fm − F)/Fm, where Fm and F are the fluorescence emission of light-adapted plants under measuring light and after applying a saturation light pulse, respectively (Schreiber et al. 1986). For each light condition, 10 measurements each were performed with three different plants.

Four-week-old Arabidopsis plants were kept in darkness overnight and used for the preparation of 2 mm2 leaf cuttings for histological and ultrastructural analysis (Schumann et al. 2017).

Tocochromanol and phylloquinone measurements

Tocochromanols were extracted with diethyl ether and 300 mM ammonium acetate from leaves or seeds (Zbierzak et al. 2010). Tocol (Matreya, State College, PA, USA) was used as internal standard. Tocochromanols were separated on a diol column and measured by fluorescence HPLC with excitation at 290 nm and emission at 330 nm (Zbierzak et al. 2010). Alternatively, tocochromanols were dissolved in dichloromethane/methanol (1:5, v/v) and separated on a reversed-phase column (C18 Gemini 5 µm, 150 × 2 mm; Phenomenex) using 95% methanol at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min. Tocochromanols were measured by LC-MS/MS on a Q-TOF 6530 (Agilent) or Q-Trap 6500+ (Sciex) mass spectrometer in the positive ion mode. Targeted lists of parental ions and neutral losses are given in Supplementary Table S2.

For phylloquinone and menaquinone-4 measurement, frozen leaves were homogenized and extracted with isopropanol/hexane (3:1, v/v). Menaquinone-4 (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as internal standard for phylloquinone measurements. For menaquinone-4 quantification, plant phylloquinone was used as a reference in plant extracts. The quinone lipids were dissolved in methanol/dichloromethane (9:1, v/v), separated on a C18 reversed-phase column, and detected by fluorescence after postcolumn reduction with Zn (Jakob and Elmadfa 1996; Lohmann et al. 2006).

Fatty acid isoprenoid alcohol esters and free isoprenoid alcohols

Leaves or seeds were frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in a Precellys homogenizer. Lipids were extracted with diethyl ether and 300 mM ammonium acetate, and internal standards were added (heptadecanoyl-phytol, 17:0-phytol, synthesized in house, vom Dorp et al. 2015; octadecenol/oleyl alcohol, Sigma Aldrich). The organic phase was harvested and dried under nitrogen gas. Lipids were dissolved in hexane and separated by solid phase extraction on silica columns (Strata S1-1, 100 mg/1 ml, Phenomenex) (vom Dorp et al. 2015). After loading the lipids in hexane, nonpolar lipids were removed by washing with hexane. Fatty acid isoprenoid alcohol esters were eluted with hexane/diethylether (99:1, v/v) and isoprenoid alcohols and tocochromanols with hexane/diethylether (92:8, v/v). All fractions were dried under nitrogen gas. Fatty acid isoprenoid alcohol esters were dissolved in chloroform/methanol/300 mM ammonium acetate (300:665:35, v/v/v) for analysis by direct infusion MS/MS on a Q-TOF 6530 mass spectrometer (Agilent) (vom Dorp et al. 2015). Targeted lists for MS/MS analysis are provided in Supplementary Table S3. The isoprenoid alcohol fractions were incubated with N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoracetamide (MSTFA) at 80 °C for 30 min. MSTFA was removed with nitrogen gas. The trimethylsilyl ethers of isoprenoid alcohols were dissolved in hexane and measured by GC-MS (Agilent). The trimethylsilylated lipids were injected via a split/splitless injector with a flow rate of 3.1450 ml/min on a HP-5MS column (Agilent, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 µm) with helium as carrier gas. The temperature gradient was as follows: initial, 100 °C, 3 min; ramp with 5 °C to 200 °C, hold 1 min; ramp with 20 °C to 310 °C, hold 3 min; ramp with 20 °C to 100 °C, hold 3 min. For targeted lists for MS analysis, see Supplementary Table S4.

Isoprenoid alcohol phosphates

Isoprenoid alcohol phosphates were measured as published (Gutbrod et al. 2023). Briefly, Arabidopsis leaves or seeds were frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground in a Precellys homogenizer, and 200 µl of extraction buffer (isopropanol/50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2/glacial acetic acid; 1:1:0.025, v/v/v) was added. The internal standards (decanoyl-phosphate [10:0ol-P] and decanoyl-diphosphate [10:0ol-PP]) were added to the leaf extract. Nonpolar lipids were removed from isoprenoid alcohol phosphates by washing the aqueous extract 4 times with 200 µl, 50 °C warm, hexane (1 volume saturated with 6 volumes of isopropanol/water, 1:1, v/v). Phases were separated after vortexing by centrifugation. To the isoprenoid alcohol phosphates in the lower aqueous phase, 5-µl saturated (NH4)2SO4 and 600 µl methanol/chloroform (2:1, v/v) were added. Samples were mixed and after centrifugation, the supernatant was dried, and the samples dissolved in methanol. Isoprenoid alcohol phosphates were measured after separation on a reversed-phase column (Poroshell 120 EC-C8, 50 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 µm, Agilent) using a Q-Trap 6500+ mass spectrometer with turbo V electrospray ion source (Sciex) via multiple reaction monitoring in the negative ion mode (Supplementary Table S5).

Measurement of chlorophyll, carotenoids, ABA, and phytenal

Photosynthetic pigments were extracted from frozen leaves after homogenization with 0.5-ml 80% (v/v) acetone and a second time with 0.5-ml 100% acetone. After centrifugation, the supernatants were combined and chlorophyll was measured photometrically (Porra et al. 1989). Photosynthetic pigments were measured by HPLC with a diode array detector (Agilent) using the absorption at 440 nm (Thayer and Björkman 1990), by comparison of the peak areas with those of chlorophyll a and b whose contents were determined photometrically in the same extract. Peak areas were corrected for different molar extinction coefficients at 440 nm (Jeffrey et al. 1997).

Phytohormones were extracted from leaves (Pan et al. 2008). Samples were dried under nitrogen gas and dissolved in methanol/water (1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid. ABA was quantified by LC-MS/MS analysis with a Q-Trap instrument (Sciex) using deuterated ABA as internal standard (d6-ABA, OlchemIm, Olomouc, Czech Republic).

Phytenal was measured as described (Gutbrod et al. 2021). Briefly, frozen leaves were homogenized and long-chain aldehydes were extracted with chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) and 0.3 M ammonium acetate. The internal standard (hexadecanal, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was added. The organic phase was harvested and dried under nitrogen gas. Aldehydes were derivatized with methoxylhydroxylamine-HCl in pyridine, dried under nitrogen gas, dissolved in hexane, and purified by solid phase extraction on a silica column (Strata S1-1 100 mg/1 ml; Phenomenex). Aldehyde-methyloximes were eluted, dried under nitrogen gas, and dissolved in acetonitrile. After separation by LC-MS/MS on a reversed-phase column, the methyloximes of phytenal and hexadecanal were measured on a Q-Trap mass spectrometer (Sciex) using the mass transitions of 324.33/96.08 and 270.28/60.0455, respectively (Gutbrod et al. 2021).

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed as described in the figure legends. Statistical data are provided in Supplementary Data Set S1.

Accession numbers

The accession numbers for VTE5 and FOLK are At5g04490 and At5g58560, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Georg Hölzl and Dr. Philipp Gutbrod for the help with crossing of the 2 mutant plants vte5-2 and folk-2 and with phytenal analysis, respectively. The help of Kirsten Hoffie and Marion Benecke for excellent technical assistance in transmission electron microscopy at the IPK, Fiona Göbel for the expression of FOLK in yeast, Jordy Pérez-Gonáles for mutant analysis, Jan Schönenbach for the generation of the pLH9000 constructs, and Anna-Lena Falz during subcellular localization is acknowledged. We thank Brigitte Dresen-Scholz and Helga Peisker for technical assistance.

Author contributions

J.R., K.G., and P.D. conceived the study and designed the research; J.R., K.G., M.M., and S.J.M.-S. performed the research; J.R., K.G., M.M., S.J.M.-S., A.J.M., and P.D. analyzed the data; and J.R. and P.D. wrote the article.

Supplementary data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Figure S1. Growth, chloroplast ultrastructure, and photosynthetic quantum yield of vte5-2 folk-2 mutant plants.

Supplementary Figure S2. Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents in vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 mutants.

Supplementary Figure S3. LC-MS/MS analysis of α-tocopherol in vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 mutants.

Supplementary Figure S4. Composition of fatty acid isoprenoid alcohol esters in Arabidopsis vte5-2, folk-2, and vte5-2 folk-2 leaves and seeds.

Supplementary Figure S5. Tocotrienol analysis by LC-MS/MS in leaves of vte5-2 folk-2 plants after homogentisate supplementation.

Supplementary Table S1. Synthetic oligonucleotides.

Supplementary Table S2. Targeted list for LC-MS/MS analysis of tocopherols and tocotrienols.

Supplementary Table S3. Targeted list for direct infusion MS/MS analysis of fatty acid isoprenoid alcohol esters.

Supplementary Table S4. Targeted list for GC-MS analysis of isoprenoid alcohols.

Supplementary Table S5. Targeted list for LC-MS/MS analysis of isoprenoid alcohol phosphates.

Supplementary Data Set S1. Statistics.

Funding

Research for this project was made possible by grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG grant # Do520/16-1; GRK 2064; EXC-2070–390732324).

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Dive Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

References

Author notes

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://dbpia.nl.go.kr/plcell/pages/General-Instructions) is: Peter Dörmann ([email protected]).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.