-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Madeline Woker, French Imperial Statecraft, Capital, Corporate Taxation, and the Tax Haven that Wasn’t, 1920s–1950s, Past & Present, Volume 266, Issue 1, February 2025, Pages 188–228, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtae018

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Towards the mid-1920s, a growing number of colonial firms began to transfer their headquarters from the metropole to French colonies to evade taxation on investment capital income. These transfers threatened to transform French colonies into tax havens. Why was this averted? This article explores the politics of corporate tax planning in the French colonial empire and shows that French colonial tax havens could have materialized on a large scale at two critical junctures: first in the inter-war period and then in the aftermath of the Second World War. It argues that they eventually did not come into being because successive administrations within the French Ministry of Finance did not let it happen. Broader structural determinants — the relative weakness of the French metropolitan fiscal state in the inter-war period and the unwillingness to let international capital dictate French development strategies in the late colonial period — crucially influenced the positions taken by the Ministry of Finance. Post-war dreams of restored grandeur made French authorities much more reluctant to outsource development and let go of state prerogatives. This unrealized possibility sheds light on the role of state power in the making and unmaking of tax havens and contributes to a fast-expanding historiography.

What is a tax haven? What does it take to make or break one? And what role have states played in this process? This is the subject of ongoing debate among historians of capitalism, legal scholars, economists and political scientists but one that has focused primarily on the Anglo-American world and blatant cases like Switzerland.1 Instead, this story will take us to Algiers, Saigon, Djibouti and various other parts of the French colonial empire where, by the end of the 1920s, a ‘large number of companies were transferring their headquarters . . . with the aim of evading taxation’.2 These words were written by Erik Haguenin, a young and reputedly intransigent auditor at the French Ministry of Finance, in a 1928 report to the President of the Council, the head of government in Third Republic France, and marked the beginning of a protracted tax conflict between various branches of the French imperial state and colonial firms.3 This happened as the Ministry of Finance grew increasingly alarmed by the spreading tendency of French firms with colonial activities to evade metropolitan capital income taxes. Such conflict not only tested metropolitan commitments to the imperial economy, but also threatened to transform French colonies into tax havens.

The Ministry of Finance, and especially civil servants working at the Régie de l’Enregistrement, the branch of the tax administration responsible for levying the capital income tax, fought adamantly to prevent this outcome, and eventually succeeded in doing so. The fear then was that the practice would set a precedent and encourage more companies to allege colonial economic activity, set up sham headquarters in the colonies, and thus avoid liability to metropolitan taxation. Developments in the French Empire stood in contrast to those in the British Empire where imperial corporate tax planning was less conflictual and where ‘support for tax havens’ is said to have ‘extended into the highest circles of government’ during decolonization.4 To this day, no overseas French department or territory qualifies as a tax haven.5 Why didn’t the French Empire generate tax havens when the British Empire did? And what does it tell us about the history of global capitalism and the role that tax havens came to play in it?

This article argues that the French Empire provided a fertile terrain for tax havenry in the inter-war period, and that colonial capitalists as well as pro-colonial politicians were poised to entrench legal arrangements that would have made it easier for companies to move their headquarters to the colonies and benefit from lower statutory tax rates. However, unlike in the British Empire, tax haven business did not ‘intersect’ as neatly ‘with development politics’ because the French Ministry of Finance refused to allow the necessary rewriting of intra-imperial tax rules to occur.6 In the post-war era, the prospect of encouraging a vast ‘race to the bottom’ became increasingly undesirable. Wherever the French metropolitan state could exert direct influence, notably in Algeria and colonies, it tried to limit and quash the tax haven temptation. The French Ministry of Finance benefitted from its superior position in the imperial state pecking order, which in turn allowed it to make good on its commitment to punish corporate tax evasion in the colonies although it failed to stem it elsewhere. This is not to say that the British Empire was immune to institutional conflict. After all, ‘Inland Revenue often voiced very serious concern about and criticism of “tax havenry” ’. But, as Vanessa Ogle argues, it was ‘the Foreign and Commonwealth Office that pushed most rigorously for allowing dependent territories to adopt tax haven legislation’.7 Across the Channel, however, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Colonies never had such clout. Just as crucially, the French Ministry of Finance could not afford the British Treasury’s early permissiveness.

Two broader interventions emerge out of this argument. First, a plea for the productive vagueness of ‘tax haven’. This article indeed suggests that historians should seek to historicize and examine modern tax havens beyond the strictures of legalistic definitions, the language of ‘capital coders’, and Google Books Ngram viewers.8 Instead of searching for ‘mythical origins’ or enumerating a list of criteria, they should explore how these might have come about in the first place all the while making a critical use of the term itself.9 Few would disagree that it is a problematic and catch-all term. It is thus best used as a shorthand lest we end up defining it out of existence.10 A second contribution of this article concerns the role of state power in histories of tax havenry. Using hitherto untapped public and private archival documents, the narrative told here is based on a close reading of administrative reports, personal correspondence, and trial minutes produced by the French Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Colonies, the Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Justice, which allow for a precise retracing of the conflict and analysis of the ethos of historical actors. The minutes of debates at the French Chamber of Deputies, pamphlets and opinion pieces, the financial press as well as private sector archives were also given sustained attention. This article indeed makes extensive use of the Colonial Union papers, a powerful professional group that defended the interests of French colonial capitalism and whose lobbying efforts crucially shaped the French imperial tax haven temptation.11

The link between imperial statecraft and the expansion of tax havens has begun to receive scholarly attention but many aspects remain unexplored.12 Despite a large literature on taxation and sovereignty in early modern empires or in the Ottoman or Chinese empires, the history of tax sovereignty in modern European colonial empires is still in its infancy.13 How and when racialized tax systems, tax breaks and incentives end up transforming territories in which they are introduced into tax havens remains poorly understood. The role of state power has come under greater scholarly scrutiny, however, alongside the link between late colonial development and the emergence of tax havens.14 Political scientists, economists and more recently historians, have suggested several possible factors for what they call the post-1945 expansion of tax havens: capital flows from the colonial world to already established tax havens, lack of metropolitan appetite for ratcheting up development aid, state sponsorship (or wilful negligence), the initiatives of individual entrepreneurs, the existence of (post)colonial currency zones, concentration of financial services, potential for secrecy, congenial legal systems, residual white settler presence, geography, size or even natural endowments.15

This article engages with these debates but uses a different approach because it explores an unrealized possibility.16 It argues that the latter was foreclosed by the combative role of the Ministry of Finance whose ‘zealous’ civil servants managed to stop aggressive attempts to allow colonies to become conduits for large-scale tax evasion, often with the tacit approval of specific ministers, notably Joseph Caillaux, Marcel Régnier or Paul Marchandeau.17 In the historical study of decolonization especially, ‘contingency, as a tonic for inevitability, has become an increasingly important consideration when writing about the end of empire’.18 By examining the possibilities or the ‘expired contingencies’ that hid in the fears and hopes of historical actors, this article thus seeks to provide a non-teleological history of tax havens and also a way of ‘reopening the future’ in a time of ‘presentist’ neoliberal ‘closure’.19 As historians debate whether we might be entering ‘post-neoliberal’ times, exploring the history of a tax haven that wasn’t seems all the more timely.20

This article focuses on the process of tax haven (un)making. It does so by paying close attention to the balance between the contextual, institutional and individual factors that shaped the French Empire’s tax haven temptation between the 1920s and the 1950s. It explicitly links the politics of imperial tax planning and tax havenry and asks two fundamental questions: Why did colonial firms feel they had the latitude to evade metropolitan taxes, and why was the metropolitan tax administration eventually willing and able to resist the long-term transformation of French colonial territories into more than ‘tax shelters’ during the developmental era of the post-war years?21

This article is divided into four parts and shows that French colonial tax havens could have materialized on a large scale at two critical junctures, first in the inter-war period and then in the aftermath of the Second World War.22 It argues that they eventually did not come into being because successive administrations within the French Ministry of Finance did not let it happen despite the efforts of colonial capitalists, their lawyers as well as circumstantial allies within colonial administrations or in the French Chamber of Deputies. A first opportunity arose in the 1920s when a surging number of colonial firms sought to set up sham headquarters in French colonies to avoid rising metropolitan taxation and take advantage of much lower statutory tax rates in the colonies. Indeed, while the tax rate on capital income in the metropole grew eightfold after 1914, from a mere 3 per cent in 1914, to 15 per cent in 1925 and 24 per cent in 1937, capital income tax rates remained low in French colonies and never attained more than 10 per cent during the inter-war period. In some parts of the French empire, the tax on capital income was simply never implemented.23

The French Ministry of Finance opposed attempts to facilitate and expand this practice because it resented its present and future impact on metropolitan state coffers. The French Empire’s tax haven temptation then experienced a new impetus in the late 1940s as colonial capitalists increasingly sought to make French colonies more attractive to US capital. The possibility of a state-sanctioned legal route to sham colonial fiscal domiciliation was eventually ruled out in the mid-1950s and so were other tax incentive schemes deemed too favourable to private capital. Institutional preference for state-led economic planning remained strong in the late colonial period and private interests were not given full latitude.24

As the ‘heartland of offshore finance’, the British Empire and its afterlives make for a relevant counterpoint.25 The British Empire contained its own fair share of permissive ‘imperial fiscal frontier[s]’, encouraging low tax morale amongst European settlers and firms.26 Headquarter transfers also took place there but the phenomenon was less divisive because a system of imperial ‘double taxation’ relief, meant to alleviate conflicts arising when the same income or assets are taxed twice across jurisdictions, had been implemented as early as the First World War.27 Fiscal domiciliation in the empire even became an official policy in the 1950s and tax havenry a tolerated, if not encouraged, path to late colonial development.28 This is because crucial differences in size, volume of circulating capital, and imperial culture allowed the British Empire to evolve into a ‘business-state’ in ways that the French Empire was less able or willing to do.29 While it very much aspired ‘to be the world’, it never managed to spin the threads of a ‘world-system’.30 Indeed, in the inter-war period, plans to bring about a coherent French ‘imperial economy’ constantly stumbled against the autonomy of the metropolitan fiscal state and its suspicion of colonial capitalism.31 Furthermore, the humiliation of defeat during the Second World War and post-war dreams of restored grandeur and power — which betrayed a drastic loss of self-confidence on the world stage after 1945 — made French authorities much more reluctant to let international capital, especially US capital, shape French development strategies in the late colonial period, and let go of state prerogatives.32

I French imperial statecraft and tax sovereignty

By the early inter-war period, the French Empire had become a sizeable political ensemble spread over four continents, taking up 9 per cent of the world’s land mass, and inhabited by about one hundred million people.33 It remained a fragile and unstable construction, however, where sovereignty and fiscal power travelled through porous ‘arteries’ despite central efforts to ‘pump it out’.34 Contemporaries did not in fact call this motley legal patchwork of colonies, protectorates and territories under mandatory rule an ‘empire’ until the 1930s.35 Tax systems differed widely across French colonial territories and did not grow in harmonious lockstep with metropolitan developments. In fact, metropolitan and colonial budgets increasingly grew apart in the early twentieth century, only to clumsily converge in the late colonial period.

Following heated debates about the ‘cost’ of colonial conquest and administration in a time of intense global imperial competition, the French parliament voted two crucial laws in April and December 1900. Both made formal colonies — territories falling under the purview of the Ministry of Colonies (the ‘old colonies’ of the Caribbean and Indian Ocean, colonies in the Pacific, Indochina, colonies in sub-Saharan Africa) — and Algeria (a hybrid territory partly assimilated to the metropole and partly under military rule) financially ‘autonomous’. These laws effectively decoupled metropolitan and local budgets, also allowing colonies to issue bonds backed by taxes levied locally as was already the case in the British Empire.36

‘Financial autonomy’ or ‘self-sufficient’ were misleading expressions, however, because imperial fiscal decentralization in the early twentieth century did not amount to financial self-determination. The ‘autonomy’ granted to French colonies and Algeria could instead be more usefully construed as a disciplining device meant to make colonial administration as cheap as possible in what was effectively a ‘low-cost empire’.37 What mattered most to French politicians then was to shield metropolitan taxpayers from colonial expenditures. This idea was in line with the protectionist spirit of the time, according to which colonies were expected to strictly benefit the metropole and not the other way around.38 Although local authorities could steer colonial tax policy, all decisions had to be signed off by the metropole before they could be implemented.39 Colonial ‘financial autonomy’ was thus a form of supervised devolution as colonial fiscal states were required to sustain themselves but could do so only in so far as it did not tread on metropolitan tax prerogatives.

Financial autonomy was nevertheless an essential condition of early colonial tax havenry because it allowed local colonial authorities to pick and choose adequate instruments from the metropolitan fiscal toolbox and to keep low tax rates to attract settlers and investment. Statutory tax rates were indeed much lower in French colonial territories than in the metropole and resistance to redistribution and progressivity was also much fiercer. The tax burden fell disproportionately on colonized subjects as one driving principle of the French colonial doctrine of taxation was to favour systems that ‘put the smallest strain on settlers’.40 Europeans were consequently well placed and eager to skirt tax obligations: in settler colonies such as Algeria for instance, tax exemptions were generously granted to attract immigrants and ‘protect wealth in the making’, so much so that Europeans were not required to pay any land tax until 1918 although land was by the far the largest source of wealth.41 European settlers benefitted from generous tax exemptions in Tunisia and Morocco where, according to the French Resident General Lucien Saint, French citizens enjoyed ‘the possibility of not paying taxes’ and of doing so ‘legally’.42 In Indochina, an income tax on Europeans was only introduced in 1920 and remained extremely low. In West Africa, taxes on Europeans were non-existent until the First World War and the 1930s only saw the introduction of timid replicas of the pre-war metropolitan tax system.43

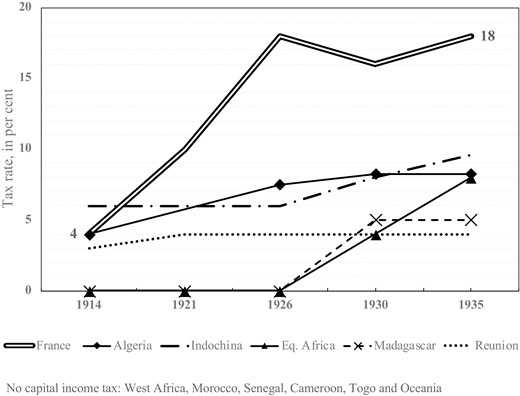

The tax rate differential between the metropole and its colonies grew wider during the inter-war period. On the eve of the First World War, the French parliament had voted the introduction of a progressive income tax in July 1914, which was only implemented in 1916 to tax 1915 incomes. But France funded its war effort through debt rather than taxes. In June 1920, a thorough income tax reform saw the drastic increase of the statutory marginal top income tax rate, which reached 62.5 per cent in 1920, and even 90 per cent in 1924.44 This increase in overall tax pressure spread to all parts of the income tax system, notably the proportional schedular taxes that undergirded it.45 Created in 1872, the tax on capital income was the oldest schedular tax and was paid directly by companies headquartered in France, which deducted it from the dividends and interest payments they distributed.46 The tax rate on capital income grew eightfold from 1914 to 1937 in the metropole but remained extremely low in French colonies, if it was ever implemented (Figure).

CAPITAL INCOME TAX RATES IN METROPOLITAN FRANCE AND IN A SELECTION OF FRENCH COLONIES, 1914–35* * Sources: René-Claude Igier, Les Sociétés de commerce françaises qui ont leur siège social à la colonie (Paris, 1936), 50; A. Dutereste, ‘Le Régime des sociétés commerciales en Indochine française’, Journal des sociétés civiles et commerciales, xii (Paris, 1926), 513; Revue algérienne, tunisienne et marocaine de législation et de jurisprudence, Faculté de droit d’Alger (Alger, 1916), 43; Recueil de législation et de jurisprudence coloniales (Paris, 1908), 523.

‘Financial autonomy’ was a fortiori the rule in territories that were not formally French colonies or administratively assimilated to the metropole, such as Algeria.47 Tunisia and Morocco were protectorates, established in 1881 and 1912, respectively, and fell under the purview of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This also meant that they were considered foreign territories for tax purposes. In both polities, France conveniently set up a system of ‘divided rule’, which ‘institutionalized many sources of authority in the territory’ not only between the French and the Bey of Tunis or the Sultan of Morocco but also with third countries through treaty arrangements.48 In Morocco, France’s margin of manoeuvre was further constrained by the treaties it had signed with other countries under the banner of the ‘open door’ principle although it found ways to circumvent these limitations over time.49 The relatively autonomous nature of the Tunisian and Moroccan protectorates had clear consequences for tax policy because it exerted pressure on French authorities to keep rates low. Tunisian and Moroccan tax systems were in fact so lenient to Europeans that conservative critics of the metropolitan tax systems tellingly praised them for their ‘liberal’ and far less ‘inquisitorial’ nature, even suggesting that they offered ‘more success stories to look up to than errors to avoid’, and only half-jokingly hinting that they could be introduced in the metropole.50

Headquarter transfers also took place between the metropole and North African protectorates. In the 1920s, lawyers noted for instance that firms originally headquartered in France would take on (s’affubler de) a ‘Moroccan nationality’ to evade French metropolitan taxes on company incorporation but also taxes on capital income. The Franco-Moroccan bank, for instance, was transformed into a ‘Moroccan’ company in 1925 to benefit from the lenient tax regime of this ‘paradise for capital’.51 Because Morocco and Tunisia were ‘foreign’ territories for tax purposes, such a move would have required a unanimous vote of all shareholders, a dissolution of the company and its reconstitution as a ‘Moroccan’ or ‘Tunisian’ company, which is also what would have been required if a company were to relocate headquarters from London to Australia in the British Empire for instance.52 These legal hurdles, the higher standing of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the relative powerlessness of French tax authorities when faced with tax evasion abroad may explain why corporate headquarter transfers in North African protectorates are less visible in the archival record than similar transfers to formal colonies. It indeed seems safe to surmise that French tax authorities had more difficulty hunting down French companies moving their headquarters to foreign countries. French courts had for instance agreed on 1 April 1925 to allow the Suez Canal Company to move its headquarters to Egypt despite the shareholders’ assembly being held in the metropole.53

In the Eastern Mediterranean, territories placed under French mandatory rule on behalf of the League of Nations enjoyed even higher levels of tax sovereignty. Starting in 1920, the French implemented a federal system that endowed local states with autonomous budgets fed by local direct taxes while the French High Commissioner sat at the helm of ‘general budget of Syria and Lebanon’, later renamed the ‘Common Interests’ budget, fed mostly by customs taxes.54 Despite French meddling, Syria and Lebanon remained foreign territories for tax purposes. Yet by virtue of the ‘open door’ policy, which theoretically granted ‘economic equality’ (that is, access to resources) to all League members, French authorities were called upon to intercede in favour of French companies that routinely complained about local tax burdens. I found very little evidence of headquarter transfers to Lebanon or Syria in 1930s. In fact, these transfers only seemed to have occurred in the late 1950s, mostly in Lebanon, which emerged as a tax haven in the late 1940s.55 French mandatory rule worked differently in Africa, where territories such as Togo and Cameroon were assimilated to French colonies on most matters yet also remained foreign territories for tax purposes until the late 1930s.56

Depending on their status and the circumstances of initial colonial occupation, French colonial territories were subject to varying levels of tax sovereignty and subservience to French metropolitan economic imperatives. Yet the principle of colonial financial autonomy applied across the board and meant that the French Ministry of Finance could keep colonial issues at arm’s length, only engaging with them when they risked encroaching on its own revenue streams. By the early 1920s, the Ministry of Finance had also taken on a greater role in overall expenditure control.57 Within the Ministry, the Enregistrement displayed a strong and distinctive ethos and employed some of the most vocal French civil servants of the inter-war period notably Georges Mer, a syndicalist who advocated for a ‘restoration of the authority of the state’ and a vision of public service impervious to the sirens of private interests.58 The Ministry’s administrative ethos is perhaps on best display in a now forgotten but then highly popular theatre play written in the late 1920s by Henri Clerc, a civil servant at the Ministry of Finance, and whose main character, Barrail, is an overly honest civil servant who resists demands from a deputy and even from his own Minister to rubber stamp a railway project in colonial Algeria. In another scene, he refuses an offer to sit on the board of a powerful French colonial conglomerate.59

The Ministry of Finance remained deeply suspicious of colonial public finances throughout the period, seeking to keep them on a tight leash. In 1925, in a debate at the French parliament about the formulations to be used in income tax declarations, the finance minister Joseph Caillaux, also known as the ‘father’ of France’s modern income tax, argued against granting protectorates and countries under mandatory rule the status of French territories for tax purposes. His fear then was that this would allow spaces that were barely fiscally legible to the metropole into the French sovereign realm, thus making crackdown on tax evasion even more difficult than it already was. It ‘seems dangerous’, he said, ‘to set up an asylum for French people where they could shelter their securities’ in countries where the metropolitan state had limited margins of manoeuvre and then ‘end up . . . in a Swiss or Dutch bank’.60 In international tax negotiations, ‘France’ typically excluded colonial territories and strictly referred to metropolitan France.61

The French Empire was thus no homogenous fiscal space and stood at the centre of a constellation of low-tax colonial jurisdictions where exchange of tax information remained highly deficient.62 Tax information did not flow seamlessly in the British Empire either but there were efforts to limit tax conflicts thanks to a relief scheme that remained in place until 1946.63 No equivalent scheme existed in the French Empire.64 This offered a fertile terrain for loopholes of all kinds and French colonial firms soon endeavoured to profit from these tax differentials as they began to face climbing tax bills in the metropole.

II The French colonies’ tax haven temptation

French colonial territories gained new visibility in the inter-war period thanks to their human and financial participation in the First World War. They also became a prime investment opportunity for French capital as other popular investment outlets such as the Russian and Ottoman Empires, had disappeared. From 1920 onward, an investment boom thus carried nearly 70 per cent of all French foreign direct private investments to the colonial empire.65 Given the relative dearth of public metropolitan investment in the inter-war period, the joint-stock company had become a prime ‘tool of colonization’ and mise en valeur (development) in the 1920s.66 This decade in fact saw the creation of 208 new colonial companies, joining the 200 existing ones, and energizing a dynamic that originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. French colonial companies were generally clustered in pyramidal business groups involved in shipping, mining, agriculture or banking and were very profitable, especially in North Africa and Indochina, where colonial firms were known for offering the highest dividends on the market.67

What drove French capital to the colonies? Genuine investment opportunities, of course, but also less productive goals such as speculation, and as this article argues, tax evasion.68 The war had left France heavily indebted, and plagued by elevated inflation and steep currency devaluation, creating ideal conditions for capital flight and large-scale tax evasion, which quickly became an issue of the first order for the French metropolitan state.69 The most common type of tax fraud concerned the tax on investment income, and foreign investment was especially prone to evasion because French tax authorities could exert far less control over their citizens’ foreign earnings and crucially could not force foreign companies to deduct the French tax when they disbursed dividends, resulting in de facto exemption of non-French securities.70 A company’s ‘nationality’ determined how the tax was paid and French firms were required to deduct the tax before making payments to shareholders.71 But if a company initially headquartered in France could move to another ‘French’ location that nevertheless lay outside metropolitan France and not in ‘foreign’ territory, then it could suddenly avoid the increasingly high metropolitan tax rates on capital income and distribute higher net dividends to their shareholders. French colonies, it turns out, became increasingly attractive destinations in the ‘international tax evasion market’ of the inter-war period.

In the mid-1920s, a first wave of headquarters transfers unfurled between the metropole and colonies. By moving their headquarters to the colonies without also relocating their shareholders’ assembly or the seat of management, these firms were effectively creating sham residence or ‘fictitious headquarters’ (siège social fictif) with the only aim of paying low or no tax on investment income. As one lawyer put it, this allowed them to obtain a ‘colonial nationality, thanks to which they ceased to be subject to metropolitan fiscal obligations’.72 The companies targeted by the metropolitan tax administration typically adopted a dual organizational structure with the main headquarters situated in the colony and an administrative headquarters in the metropole. While key management decisions were still taking place in Paris, Lyon or Marseille, offices in the colony remained small and usually only comprised an operations manager and a handful of delegated administrators.

In rapid succession, at least a dozen colonial companies began to make this move. The first significant transfer occurred in 1924 when the Compagnie du Cambodge, a rubber company, moved its headquarters from Paris to Saigon, quickly followed in late March 1925 by the Compagnie des Caoutchoucs de Padang, another powerful rubber company operating in three different empires, namely in the Belgian Congo, French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies, and part of the same Belgian conglomerate, the Rivaud group.73 Thanks perhaps to its savvy tax planning, the Rivaud group was serving amongst the highest dividends in the rubber industry in the late 1920s. In 1926, for instance, the financial press emphasized that the dividend distributed by the Compagnie des Caoutchoucs de Padang was worth 130 per cent (in nominal terms) of the initial 1911 investment, and that it was much higher than other comparable companies.74 These large conglomerates — the Rivaud group or the Bank of Indochina — did not typically move their own headquarters but allowed many of their subsidiaries to do so, suggesting that this was very much a tax planning exercise.

In the inter-war period, North Africa, Indochina and West Africa attracted the most capital but headquarters transfers occurred across geographical and sectoral boundaries.75 In 1925, a mining company called the Phosphates de Constantine transferred its main offices from Paris to Algiers. The company was itself part of a financial corporation, the Société Générale des Mines d’Algérie-Tunisie, which moved its own headquarters at the same time. In February 1926, the Compagnie des vignobles de la Mediterrannée, a wine production company, transferred to Bône (today’s Annaba) in Algeria.76 The shipbuilding company L’Est Asiatique français followed suit in March 1926, while in August 1926, the Société immobilière d’Extrême-Orient transferred from Paris to Saigon. Some newly formed companies in the 1920s simply decided to set up their headquarters in the colonies instead of Paris even though most of their shareholders and managers lived in the metropole. This was the case for instance of the Crédit Foncier de l’Ouest-Africain, which had been established in 1928.77

These transfers hardly went unnoticed and risked creating a precedent. The Enregistrement was indeed quick to label them as tax evasion and flagged most of these colonial headquarters as ‘fictitious’.78 In 1928, four years after its official move to Saigon, the Compagnie des Caoutchoucs de Padang’s directors and administrators were all still based in Paris, a tax official in Paris noted.79 Paris was therefore the firm’s real headquarters and these transfers had been made with the sole motive of evading the metropolitan capital income taxes payable at the firm’s real headquarters.80 Colonial firms’ tax evasion practices had by then become a highly visible issue in the French public sphere and a target of the metropolitan satirical press, which poked fun at these colonial firms ‘setting up their headquarters in these happy corners where the tax administration doesn’t operate’.81 But moving headquarters from the metropole to one colony or from one colony to another was one of several strategies used by colonial firms to juice up their after-tax profits: some also transferred profits from metropolitan headquarters to colonial subsidiaries to pay lower taxes on commercial and industrial profits.82 In the British Empire, companies similarly transformed branches into fully fledged subsidiaries because they could be considered ‘autonomous companies’ whose shares belonged to the parent company.83

Yet the practice of headquarters transfers to lower colonial tax jurisdictions caused the most uproar. This is because it clashed with the French tax code as well as budding international tax rules, which stipulated that taxes on investment income were payable at the site of the capital holder’s residence, which in most cases was the metropole, not the colony. It also seems like proving the corporate tax evasion methods mentioned above, notably internal transfer pricing, would have required higher administrative capacity and the ability to scrutinize company’s books across metropole and colony. Headquarter transfers were arguably ‘easier’ and quicker to spot. The Caoutchoucs de Padang company was a particularly egregious example since its main centre of operations was not even in Indochina but in the Dutch Indies. The company’s management could thus not pretend for its defence that it had moved headquarters to the location where most profits were generated. This was clearer still in the case of the Compagnie maritime de Majunga whose headquarters had initially been set up in Madagascar but had then decamped to Djibouti in 1928 shortly after a tax on capital income was introduced in Madagascar. Here it was clear even to authorities in Madagascar that the sole motive had been tax evasion.84

III Sham domicile and the politics of taxing rights in France’s ‘imperial economy’

The triangular headquarters legal dispute between metropole, colonial administrations and colonial firms quickly escalated under the twin pressure of the Great Depression and plummeting metropolitan and colonial budgets.85 On 22 August 1930, the French metropolitan tax administration had indeed summoned the Compagnie du Cambodge to pay all sums incurred to the metropolitan tax administration since October 1924.86 Nearly two years later, the Seine Tribunal ruled that the Compagnie des Caoutchoucs de Padang’s transfer of headquarters to Saigon was indeed ‘fictitious’ and executed solely to evade taxation. In July 1935, the Cour de Cassation, France’s highest judicial court, confirmed this decision. The ruling condemning the Compagnie du Cambodge, another member of the Rivaud group, in December 1938 further entrenched this jurisprudence. Bolstered by these decisions, the Enregistrement continued to vehemently oppose the idea that companies active in the colonies but primarily financed by French metropolitan capital should be allowed to move their headquarters there. While consequences on future revenue clearly mattered less than the ‘encouragement’ it would create towards ‘tax resistance’, the Minister of Finance’s chief of staff and inspecteur des finances Jean Meaudre, estimated in a 1936 letter to the Minister of Colonies that future losses for metropolitan coffers might pile up to ‘at least’ 100 million francs, amounting to 3.5 per cent of all capital income tax revenues that year.87

Nearly twenty years after the implementation of a double taxation relief scheme in the British Empire, and crushed initiatives from Guadeloupe or Madagascar to apportion taxable corporate revenue in the empire, the French government appointed an inter-ministerial commission in 1937 and gave it a clear mandate to put an end to the conflict.88 Led by the state councillor Loriot, commission members first set out to measure the scale of the issue and produced some rough estimates. The commission files notably contain the table reproduced below, which presented the number of colonial companies in each colonial territory and divided them between those headquartered in the colony and those headquartered in the metropole89 (Table). Although lacking in sophistication, these calculations reveal that fiscal domiciliation in French Western Africa, Indochina and Algeria had become particularly attractive despite the legal risk. The number of companies headquartered locally was higher in the colonies of French West Africa or in Indochina although there was little doubt that half of these companies’ shareholders did not in fact live in Dakar or Saigon.

Estimations of Number of Colonial Companies in the Territory they Operate, Arranged by Fiscal Domicile, and Established by the Loriot Commission in 1938

| . | Colonial companies headquartered in metropolitan France . | Colonial companies headquartered in the colonies . |

|---|---|---|

| French West Africa | 65 | 120 |

| French Equatorial Africa | 45 | 40 |

| Madagascar | 48 | 35 |

| Indochina | 79 | 101 |

| Algeria | 64 | 399 |

| . | Colonial companies headquartered in metropolitan France . | Colonial companies headquartered in the colonies . |

|---|---|---|

| French West Africa | 65 | 120 |

| French Equatorial Africa | 45 | 40 |

| Madagascar | 48 | 35 |

| Indochina | 79 | 101 |

| Algeria | 64 | 399 |

Estimations of Number of Colonial Companies in the Territory they Operate, Arranged by Fiscal Domicile, and Established by the Loriot Commission in 1938

| . | Colonial companies headquartered in metropolitan France . | Colonial companies headquartered in the colonies . |

|---|---|---|

| French West Africa | 65 | 120 |

| French Equatorial Africa | 45 | 40 |

| Madagascar | 48 | 35 |

| Indochina | 79 | 101 |

| Algeria | 64 | 399 |

| . | Colonial companies headquartered in metropolitan France . | Colonial companies headquartered in the colonies . |

|---|---|---|

| French West Africa | 65 | 120 |

| French Equatorial Africa | 45 | 40 |

| Madagascar | 48 | 35 |

| Indochina | 79 | 101 |

| Algeria | 64 | 399 |

The commission’s work did not resolve the conflict despite active campaigning by the colonial lobby to transform colonies into fully fledged tax havens. As early as 1931, the French Colonial Union had begun to circulate an amendment proposal to the annual budget law authored by Gratien Candace, a deputy from the French Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, proponent of an integrated imperial economy, and strong supporter of the creation of maritime free-trade zones in the French Empire.90 Participants at the 1935 Imperial Conference then reworded the text slightly, proposing that ‘French firms with headquarters and operations in Algeria, in the French colonies, in protectorates or territories under mandatory rule’ should be ‘exclusively governed by local tax law, even if their administrative or managing centres are in the metropole’.91 Although never passed, this was a daring proposal because it guaranteed that a simple modification of a headquarters’ location in a company’s articles of association would be a sufficient condition to change its fiscal regime. It meant that taxes on capital income would be payable at the site of operations, that is, where income was generated and where tax rates were much lower, rather than where most shareholders resided, the metropole, where tax rates were higher.

The Candace amendment would have resolved the double taxation issue in the French Empire on terms favourable to the colonies and open the way to tax havenry. Yet the arrangement went against the spirit of the metropolitan tax code as well as apportionment methods that were being devised at the League of Nations at the same time. Crucially, it also risked inspiring other companies to allege colonial activity and engage in tax evasion. Because it proposed to normalize the situation of fraudulent firms, it soon raised the suspicions of the Ministry of Finance. To be deemed legal and devoid of fraudulent intention, the headquarters transfer had to be ‘effective’, Ministry’s officials argued. This meant, in other words, that all governing bodies, including the general assembly and administrators’ meetings would have to be transferred to the colonies as well.92

Moving the location of general assembly and administrators’ meetings across continents was not possible for many companies, however. Most shareholders lived in the metropole, and smaller ones would very quickly complain if asked to travel to the colonies for each meeting. Financial newspapers such as Fernand Raucoules’ Commentaires had indeed started to show interest in the matter as some companies were now exclusively holding shareholders’ meetings in the colonies in fear of further lawsuits. In its 5 May 1940 issue, it deplored the fact that the Compagnie du Cambodge’s impulse to ‘pay less taxes’ had rendered smaller shareholders’ control thoroughly impossible. This situation was deemed highly ‘anti-democratic’ and not worthy of a country like France, especially in such troubled times.93

The appeals of small shareholders for more control held little weight against the quest of larger ones for heftier after-tax profits, however. Management decisions remained geared towards ensuring that colonial firms, and ultimately any firm, could transfer headquarters to the colonies and thus reduce its tax burden. The public had been aware of these tax planning strategies for over a decade, but available archival evidence only points to public mobilization in the late 1930s under the left-wing Popular Front government. A distinct case is that of West Africa, where in 1937 a civil servant union in Côte d’Ivoire organized to defend the colony’s governor’s project of taxing corporate profits. In a letter sent to the West Africa Federation Governor Marcel de Coppet, they deplored the fact that while the Federation had become ‘the mecca [terre d’élection] of the Joint-Stock Company, of Banks, of Credit Institutions’, ‘current legislation’ allowed ‘some of these companies to set up their headquarters on this blessed land in order to completely avoid income taxes’. The union expressed its ‘shock’ to see that ‘companies whose artificial headquarters and general assemblies are held in improbable small Sudanese, Senegalese, Guinean towns’ were able to ‘avoid pretty much all taxes’ especially in a context of economic crisis.94 In their pamphlets, critics of corruption in inter-war France also mentioned the sketchy dealings of ‘fictitious colonial companies’.95

Changing the law was indeed key to the long-term viability of colonial capitalists’ plans. For ‘avoidance to occur’, one tax historian recently argued, ‘there have to be latent potentialities contained within the legal code’.96 In order to ease up colonial domiciliation, colonial capitalists and their lawyers as well as allies in the French parliament, began to advance the idea that all taxation of colonial firms should occur in the ‘source’ tax jurisdiction, that is, where income was produced (the colony) and not in the ‘residence’ tax jurisdiction, that is, where investment capital originally came from and was owned (the metropole). One such lawyer was Serge Frager, Director of Litigation at the Bank of Indochina, and author of a book on double taxation in the French Empire. In a context of mounting international tensions, Frager also warned that if French companies were not offered the opportunity to transfer headquarters to their colonies, German companies would take advantage of the loophole.97

Framing the question in terms of imperial ‘taxing rights’ and geopolitical risks rather than debating the ‘fictitious’ nature of headquarters transfers had one large benefit: it created a circumstantial alliance with colonial governments that were, for their part, interested in gathering as much revenue as possible in a context of generalized austerity induced by the self-sufficiency principle.98 In this regard, the conflict was also very much a debate about the apportionment of corporate taxable revenue in the empire and the ability of colonial authorities to tax companies operating on their soil. But this relationship was primarily opportunistic and should not be read as the sign of any clear alliance between private interests and colonial states. It served a clear purpose and allowed colonial authorities to blame the metropolitan Ministry of Finance for its lack of dedication to ‘colonial development’.

The French tax administration would have been keenly aware of contemporaneous international tax negotiations at the League of Nations, where double taxation was the main topic. In 1923, a committee of four internationally mandated European and American economists, which included renowned American public finance economist Edwin Seligman and the British industrialist Josiah Stamp, published a report that laid the foundations of the international tax order that we still live in today. Meant to tackle the ‘evil’ of ‘double taxation and tax evasion’, the report’s main contribution was to set out guidelines for the fairest possible allocation of taxing rights between capital-exporting (or creditor) and capital-importing (or debtor) countries. Whereas double taxation relief in the British Empire was merely a method for sharing taxable revenue regardless of income source, the four economists, and especially Edwin Seligman, sought a system that would have ‘classified’ taxable income according to where its ‘economic allegiance’ lay.99

This ‘classification’ method established that income from land, mines, commercial establishments, agricultural machinery, money and vessels, otherwise known as ‘immovable assets’ would have to be taxed where these assets were physically situated, while income generated from ‘movable assets’ (corporate shares, bonds, etc.) would be taxed at the place of residence of the capital holder.100 These rules were then further refined throughout the 1920s by a group of experts meeting at the League of Nations but their deliberations were often conflictual and biased in favour of capital-exporting countries, notably Britain.101 The French Ministry of Finance stood on the side of ‘source’ countries in international tax negotiations given its status of debtor country in the inter-war period, but took the opposite view when it came to tax negotiations with its own colonies. While the Ministry drew on international developments to make its case, it was French colonial capitalists who now sat on the side of ‘source’ countries. They only did so, however, because it bolstered their case for fiscal domiciliation in the colonies.

Colonial capitalists felt entitled to make these demands in the late 1930s because colonies had by then become the first destination for French goods and a prime shelter for French capital.102 This was a period of rampant imperial protectionism that saw most colonial capitalists eagerly touting their commitment to the French ‘imperial economy’. But a French imperial economic system struggled to materialize despite efforts to organize an equivalent to the 1932 Ottawa Imperial Conference, a high point of the British Empire’s protectionist turn during the inter-war period. The French ‘imperial economy’ essentially remained an awkward mix of variously faring colonial economies, which often held conflictual commercial relationships with the metropole.103 The diversity of legal, monetary and economic regimes in the French Empire meant that conflicts were frequent even as the Ministry of Finance tried to keep the upper hand.

The imperial economy came under even greater strain during the Second World War because hostilities severed connections between administrations and businesses in the metropole and colonies. Forced German requisitions proved particularly daunting for colonial companies but while historians agree that the war was overall disruptive to colonial capitalism, some business leaders stood firmly on the side of the Vichy regime.104 Some even sought to take advantage of the war to push for legislative change. So did the Fruit Colonial Français for instance, a pineapple juice company created in February 1939 in Paris. In a letter to the metropolitan tax administration sent in April 1940, the director requested further information regarding its ability to move headquarters to Abidjan in the colony of Côte d’Ivoire. It argued that because of the war, shareholders’ meetings could only take place in the metropole any way and that it was therefore a convenient time to modify the current legislation.105

French courts nevertheless continued to issue rulings against tax-evading companies throughout the war, further impeding the tax haven temptation. In January 1942, courts went against the Société Agricole du Gabon, a timber company operating in Central Africa while in July 1942, a similar fate struck the Société Coloniale de Bambao, the largest landowner in the Comoros archipelago and one of the main vanilla, ylang-ylang and orange flowers suppliers of the Grasse perfume industry in southern France.106 In the British Empire, the Treasury went as far as banning corporate headquarters transfers, in accordance with the 1939 Defence Regulations.107 But in the French Empire, the Ministry of Finance’s reluctance to acquiesce to fiscal domiciliation in the colonies was never sanctioned by an official ban, and the conflict was allowed to linger on.

IV Ending the French empire’s tax haven temptation

The Vichy years were marked by efforts to enact ambitious imperial economic reforms, but it is only after the Brazzaville conference of 1944 and the signing of the new Constitution of the Fourth Republic in 1946 that the financial links between the metropole and its colonies were thoroughly transformed.108 Heeding the call of the new Keynesian and developmentalist credo of the post-war years, French imperial authorities eventually let go of the principle of strict colonial self-sufficiency. The law of 30 April 1946 created the FIDES (Le Fonds d’investissement pour le Développement Economique), a new overseas development fund operated from the metropole that oversaw much higher levels of public money transfers to the empire. The ‘empire’ itself underwent sizeable change. Renamed the ‘French Union’, it now comprised European France, the French departments of Algeria (Alger, Constantine and Oran), the departments of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guiana, Reunion, the ‘overseas territories’ of sub-Saharan Africa, French India and the Pacific, the ‘associated states’ of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, and the United Nations Trust territories of Cameroon and Togo, while the protectorates of Tunisia and Morocco refused to participate in its institutions.109

French colonial capitalism underwent rapid transformations in an age of undisputed American economic supremacy. Victorious involvement in the Second World War had indeed propelled the United States to the status of global political and economic hegemon, which was further solidified in the immediate post-war era through the Bretton Woods Agreement, the Marshall Plan, and the NATO military alliance. This gave reasons to French imperial businessmen to anticipate an inflow of US capital into the French Empire. French colonial capitalism also benefitted from a ‘rejuvenated’ ‘post-war colonialism’, which focused on ‘dollar-earning, saving, and papering over the cracks of metropolitan industrial infirmity’.110 Its geography similarly experienced a shift: faced with deepening conflict in Indochina, a portion of French colonial business based in Asia began to redeploy its activities in North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa.111 The late 1940s in fact saw a distinct ‘economic boom’ in the French colonies of West and Central Africa. Throughout the 1940s, colonial authorities noticed important capital transfers coming out of Indochina and Algeria to France and other parts of the empire such as Morocco, Tangier, Djibouti or Cameroon.112 The Rivaud group companies, which had been targeted by French tax authorities in the inter-war period, notably the Compagnie des Caoutchoucs de Padang, the Compagnie du Cambodge, and the Plantations des Terres Rouges moved their activities to Cameroon in the early 1950s despite the looming threat of fines and prosecution.113

Companies continued to benefit from what was still a very blurry legal landscape and debates about which jurisdiction ought to be taxing colonial investment income, and related discussions about the ease with which colonial firms should be allowed to set up headquarters in the colonies, remained ongoing. In 1947, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Overseas France tellingly still disagreed about the exact amount of the rebate owed to the colonies for the years 1941 to 1946.114 Civil servants at the Ministry of Finance remained undeterred because keeping French capital available for reconstruction in the metropole always mattered more than colonial development. The Ministry of Finance also wanted to avoid easing the set-up of ‘fictitious headquarters’ at all costs. This again, stood in contrast to the situation in the British Empire, where schemes were introduced to authorize headquarters transfers to the colonies, thus overturning the 1940 ban.115

Post-war geopolitical developments provided new impetus to the proponents of sham colonial fiscal domiciliation in the French Empire. The pressure exerted by US capital, which had had its eyes set on the French Empire since the Second World War, prompted some to resurrect the debates of the inter-war period.116 Further vacillation on colonial firms’ tax treatment risked squandering important financial opportunities, warned the business leader Charles-André Roux in a letter to the Minister of Finance sent in late June 1945. As more and more foreigners, especially Americans, were now likely to invest in overseas France, tax attractiveness could be a key selling point. ‘If these foreign companies’ headquarters remain in their countries of origin (in the case of the United States, in the state of Delaware, for instance, where corporate tax law is especially favourable)’, he explained, ‘French companies will lose out to their competitors’. ‘However’, he continued, ‘if the French tax regime made domiciliation in the colonies easier, the French government would be better equipped to invite foreign companies to set their headquarters there’. In other words, if it was to hold its rank in the emerging post-war world order, France had no choice but to ensure the competitiveness of its firms and use a rather classic ‘race to the bottom’ strategy.117

Reluctant to transform colonies into ‘Delawares’, the Ministry of Finance engaged in further delaying tactics. But French colonial capitalists, and especially an active and vocal group of ‘opinion leaders’, which included Charles-André Roux and also Luc Durand-Réville, a powerful French colonial businessman with interests in Gabon, fellow businessman Edwin Poilay and others, were not easily discouraged and carried on their efforts to change the law.118 Historians have highlighted the extreme racism of le patronat colonial, its unwillingness to let go of the empire, and rooted disbelief at the possibility of non-white-led postcolonial futures. This could partly explain why French colonial capitalists clung to the tax haven temptation until the very end, refusing to let go of their investments.119

In early 1948, Luc Durand-Réville introduced legislation at the National Assembly that largely resurrected the Candace proposal from the 1930s. The aim was, once again, to create a legal path to colonial fiscal domiciliation by making sure that legal headquarters could be set up at the main site of production regardless of where most shareholders and managers lived. The measure, it was argued, would help accelerate overseas territories’ economic development and thus ward off political demands.120 In March of the same year, the members of the French Union Economic Commission of the Economic Council, a corporatist assembly set up by the Constitution of the Fourth Republic whose role was to provide legislative opinions, sat down to discuss Durand-Réville’s proposal. Participating in the meeting that day were a representative from the French Ministry of Finance, M. Jean, Luc Durand-Réville himself as well as Edwin Poilay and Charles Decron, the head of the all-powerful commercial company the Compagnie française de l’Afrique Occidentale. In what turned out to be a rather heated exchange, M. Jean laid out the Ministry’s points of disagreement and firmly reiterated arguments that had been heard during the inter-war years, namely that the Ministry remained committed to avert the mass creation of ‘fictitious headquarters’ in the colonies. As a result, any company electing a colonial territory as headquarters in their articles of association, would also have to move its management and control as well or face fraud accusation and the full force of the law.121

The battle between proponents of companies’ right to shift headquarters and their adversaries also continued in legal journals, in many ways foregrounding current debates about the difference between illegal ‘tax evasion’ and lawful ‘tax avoidance’.122 In a 1947 article, Bernard Berenger, a notary based in Saigon in Indochina and Jacques Razouls, a law professor, argued in favour of domiciliation in the colonies, declaring that headquarters should only be set up at the ‘site of operations’. They also engaged in a lengthy legal discussion about the difference between ‘motive’ and ‘fraud’, defending the ‘right’ of colonial firms to optimize their tax bills. Everyone was entitled to choose the less ‘onerous’ form of taxation, the two lawyers argued, and as fraud implied immorality, colonial tax arbitrage could by no means be considered fraudulent. The ‘fictitious’ nature of colonial headquarters could therefore not be retained and decreeing that headquarters could only be situated where the board and general assembly met was to err dangerously far from ‘realities’ and to transform law into a ‘pure abstraction’.123 But not all specialists agreed with these conclusions and stood firmly on the side of the established jurisprudence, which favoured the point of view of the Ministry of Finance.124

Throughout the early 1950s, the Ministry of Finance remained intent on ‘torpedoing’ the Durand-Réville proposal and delayed its discussion by five years.125 In 1950, it suggested an alternative system, similar to the one suggested by the Loriot Commission, which would have forced colonial companies to pay taxes to the colony on the income generated from activities on its territory, only to be taxed again at the metropolitan level on all profits minus the colonial tax. This suggestion exposed the company to the highest tax rate and was thus hardly acceptable to the colonial lobby. But the project was then left to linger until late October 1954, when it came up again at a meeting of the ‘Tax Studies Commission’, which had been set up by the Ministry of Colonies to conduct ‘comparative tax law’ studies and formulate ‘tax systems conducive to rapid economic and social development’. The commission quickly jettisoned it and explained that, if turned into law, the proposal would generate ‘detrimental’ competition, on a par with what was happening ‘between American states where companies’ headquarters constantly move in order to profit from the most favorable tax system’.126 This was an explicit disavowal of the French empire’s ‘Delaware’ strategy suggested by Charles-André Roux in 1945.

This was not the end of the French Empire’s tax haven temptation, however. In 1954, the deputy Sourou-Migan Apithy, future premier and Minister of Finance of Dahomey (today’s Benin) put forward a bold tax incentive scheme in a legislative proposal. The scheme would have allowed all companies, regardless of whether they had activities in French overseas departments or territories, to benefit from total tax exemptions on corporate tax if they reinvested these tax-exempt profits in the French Union. The goal was clear: increase the attractiveness of the French Union. But so were the risks, according to the project’s detractors, because it would have empowered any French company to use the pretext of colonial activity to pay essentially no taxes on its profits.127Although commentators saw the potential for increased private investment in overseas France, the project was eventually shelved in 1954 because it lacked a mechanism capable of ensuring that profits would effectively be reinvested as planned. This was deemed too costly for the French Treasury and potentially conducive to tax evasion.

Instead of allowing discrete parts of the French Union to transform into tax havens, metropolitan authorities preferred targeted and time-bound tax incentives.128 In the French Empire, ‘the goals and methods of imperial business’ thus ‘remained out of kilter with the colonial development and welfare ethos’ of the time.129 In a speech he gave at the Assembly of the French Union in October 1955, the Minister of Overseas France Pierre-Henri Teitgen warned against granting tax guarantees ‘in a general and absolute manner to all the foreigners who would present themselves with capital’ because this would be the surest way to ‘loose a necessary tool of economic policy, that which would consist in favouring investments in such and such sector where they are useful and on the contrary, not to favour them where they are not useful’.130 In December 1953, a law had indeed established so-called ‘long-term exceptional tax regimes’ in overseas territories, authorizing competent assemblies to grant tax breaks to firms whose creation, equipment or extension carried particular importance for the implementation of the post-war ‘modernization’ plan for overseas France. These ‘long-term exceptional regimes’ were ratified by local assemblies, but the Ministry of Finance kept the upper hand.131

‘Long-term exceptional regimes’ gave firms a ‘special status’, which could only be granted after approval from the Minister of Finance and for a maximum period of 25 years. This new regime was first applied in Cameroon as early as 1955, followed by New Caledonia, French Equatorial Africa, French West Africa and Madagascar.132 In Algeria, the government general also sought to grant ‘very large’ tax and financial advantages to companies regimented into Algeria’s industrialization plan.133 The 1948 metropolitan tax code technically applied to the new overseas departments of the Antilles and Indian Ocean but a tax exemption (défiscalisation) law was also introduced in 1952 to encourage private investment. Although tax exemptions ‘temporarily’ satisfied private interests, they came with strings attached and soon became conditional upon the instauration of a minimum wage.134

Tax incentive schemes were hardly beneficial to local populations, however. According to Andrew W. M. Smith, they instead ‘contributed only to the enrichment of private interests and metropolitan government, leaving the colonial administration all but dependent on capital invested through the paternal metropolitan state’.135 They indeed provided ways for French metropolitan authorities to preserve their economic interests in the face of increasing local political demands and higher tax rates. In 1952, tax specialists were deploring that ‘the time [was] long gone when French Equatorial Africa and Cameroon, faraway lands of overseas France, could be considered a taxpayer’s paradise’.136 In 1955, the French colonial tax specialist René Wirth similarly bemoaned the fact that the French metropole preferred to export the metropolitan tax system rather than follow the example of tax reform in ‘new countries’.137 After 1946 and even more so in the aftermath of the loi-cadre of 1956, former colonies in sub-Saharan Africa were granted greater decision-making powers and became increasingly invested in aligning their tax systems with those of the metropole.138 Members of local territorial assemblies and of the Grand Council of West Africa for instance introduced projects designed to increase corporate tax pressure or tax shipping companies headquartered in France, often eliciting strong push back from Paris.139

In contrast, smaller territories sometimes used increased powers granted through the French Union to vie for lower taxes. Local authorities in the Eastern African territory of Djibouti tried to do so in the late 1940s by engaging in what was later deemed to be the French Empire’s ‘only voluntary experience of tax haven promotion’.140 Under the impulsion of the local governor Paul-Henri Siriex, Djibouti, then officially called French Somaliland, was declared a free port on 1 January 1949. The local franc was pegged to the dollar and made freely convertible in March, authorities got rid of exchange controls, and most direct taxes were abolished between late 1949 and 1952. Several companies originally headquartered in Indochina even moved into the East African territory in the 1950s, notably the Rivaud group’s Plantations des Terres Rouges and the Union Financière d’Extrême-Orient, a prominent Indochinese financial conglomerate.141

But private capital did not flock to Djibouti, and these transfers remained limited. The project petered out notably because of the competition of the nearby British-controlled port of Aden and lack of support from Paris.142 Had the project succeeded, it is highly unlikely that Djibouti would have been able to become an international financial centre as well given that there was no French equivalent to the City of London and that the French financial system remained state-led and largely insulated from the global economy between 1945 and the early 1960s.143 Elsewhere in the world, when placed in a situation where they could have participated in the making of a tax haven, French metropolitan authorities backed down. The New Hebrides (today’s Vanuatu), a Franco-French condominium until the 1970s, became a tax haven despite the French and not thanks to them.144

* * *

This article traced the rise and fall of the French Empire’s tax haven temptation between the mid-1920s and the late 1950s. It also prompted us to rethink the emergence of tax havens as a modern phenomenon via an unusual route: that of the politics of tax planning in the French colonial empire. By showing that, when it could, the Ministry of Finance resisted the transformation of colonies into conduits for large-scale tax evasion, this article has argued for the importance of state power in the making and unmaking of tax havens but also for the importance of exploring paths not taken. This should in no way amount to a normative judgement about France’s particular path to economic and financial decolonization but only serve as a humble reminder that tax haven projects can be made to fail, and that states matter in today’s fight against tax havens.145

Footnotes

I would like to thank Aditya Balasubramanian, Andrea Binder, Lorenzo Bondioli, Damian Clavel, Denis Cogneau, Camille Cole, Martin Daunton, Muriam Haleh Davis, Pierre-Cyrille Hautcoeur, Anthony G. Hopkins, Ajay K. Mehrotra, Flavien Moreau, Vanessa Ogle, Susan Pedersen, Terence Peterson, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuelle Saada, Waltraud Schelkle, Jason Sharman, as well as participants of the ‘Reading, Researching, and Writing the French Empire’ online seminar, the Cambridge Global Economic History seminar, the Paris School of Economics Economic History seminar, the Offshore Finance Workshop, Freie Universität, Berlin, the Oxford International Tax Governance and Justice workshop, and the Actualité de la recherche sur les mondes coloniaux workshop in Aix-en-Provence for their feedback and encouragement.

Sébastien Guex and Hadrien Buclin (eds.), Tax Evasion and Tax Havens since the Nineteenth Century (London, 2023), 1–34; Dhammika Dharmapala, ‘Overview of the Characteristics of Tax Havens’, CESifo Working Paper No. 10411 (2023); Kristine Sævold, ‘Tax Havens of the British Empire: Development, Policy Response, and Decolonization, 1961–1979’ (Univ. of Bergen Ph.D. thesis, 2022); Vanessa Ogle, ‘Archipelago Capitalism: Tax Havens, Offshore Money, and the State, 1950s–1970s’, American Historical Review, cxxii (2017); Vanessa Ogle, ‘ “Funk Money”: The End of Empires, the Expansion of Tax Havens, and Decolonization as an Economic and Financial Event’, Past and Present, no. 249 (Aug. 2020); Christophe Farquet, Histoire du paradis fiscal suisse: expansion et relations internationales du centre offshore suisse au XXesiècle (Paris, 2018).

Service des archives économiques et financières, Savigny-le-Temple, France (hereafter SAEF), SAEF/B-0043315/1: Note pour le président du Conseil, 7 février 1928, <https://rebeca-archives.finances.gouv.fr/exl-php/cadcgp.php?CMD=CHERCHE>.

Florence Descamps, ‘Du verrou au sextant: outils de gestion, outils de pouvoir. La direction du Budget et le contrôle de la dépense publique, 1919–1974’, Gestion et Finances Publiques, i (2019), 118.

Ogle, ‘Archipelago Capitalism’, 1443. See also Sævold, ‘Tax Havens of the British Empire’, 29–30.

Bernard Castagnède, ‘Parler de paradis fiscal pour l’Outre-Mer français relève de la mythologie!’, Outre-Mer 1ère, 25 avril 2013. This is also the conclusion of a recent EU report on ‘Tax Evasion, Money Laundering and Tax Transparency in the EU Overseas Countries and Territories: Ex-Post Impact Assessment’, EPRS European Parliament Research Service (2017), available online at <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_STU(2017)593803> (accessed 13 June 2024).

Ogle, ‘Archipelago Capitalism’, 1442.

Ibid., 1444.

This is in line with the approach of Vanessa Ogle, who writes that ‘contemporary definitions’ of tax havens ‘are often too static’ in ‘Archipelago Capitalism’, 1432. On capitalism and law, Katharina Pistor, The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality (Princeton, 2019).

Christophe Farquet, ‘Attractive Sources: Tax Havens’ Emergence: Mythical Origins versus Structural Evolutions’, SSRN Scholarly Paper (2021). Steven Dean highlights how ‘tax haven’ became a racialized term in ‘Surrey’s Silence: Subpart F and the Swiss Subsidiary Tax that Never Was’, Law and Contemporary Problems (2023), 8, available at <https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/3642> (accessed 10 Apr. 2023).

Guex and Buclin (eds.), Tax Evasion and Tax Havens, 26.

Stuart M. Persell, ‘Joseph Chailley-Bert and the Importance of the Union Coloniale Française’, Historical Journal, xvii (1974); Stuart Michael Persell, The French Colonial Lobby, 1889–1938 (Stanford, 1983).

Gurminder K. Bhambra and Julia McClure (eds.), Imperial Inequalities: The Politics of Economic Governance across European Empires (Manchester, 2022).

Histories of taxation in France or the United Kingdom generally exclude the empire, see for instance Nicolas Delalande, Les Batailles de l’impôt: consentement et résistances de 1789 à nos jours (Paris, 2011); Martin Daunton, Just Taxes: The Politics of Taxation in Britain, 1914–1979 (Cambridge, 2002); Julian Hoppit, The Dreadful Monster and its Poor Relations: Taxing, Spending and the United Kingdom, 1707–2021 (London, 2021). On tax unevenness in the Ottoman Empire, see Ziad Fahmy, ‘Jurisdictional Borderlands: Extraterritoriality and “Legal Chameleons” in Precolonial Alexandria, 1840–1870’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, lv (2013); and also the large literature on ‘mixed courts’ and the tax privileges they granted to foreigners, for instance Nathan J. Brown, ‘The Precarious Life and Slow Death of the Mixed Courts of Egypt’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, xxv (1993). On the lack of fiscal sovereignty in early twentieth-century China, see Hans van de Ven, Breaking with the Past: The Maritime Customs Service and the Global Origins of Modernity in China (New York, 2014). Economic histories of colonial taxation tend to have a regional focus and/or have not explored issues of tax sovereignty: Leigh Gardner, Taxing Colonial Africa: The Political Economy of British Imperialism (Oxford, 2012); and for the French Empire, Denis Cogneau, Yannick Dupraz and Sandrine Mesplé-Somps, ‘Fiscal Capacity and Dualism in Colonial States: The French Empire, 1830–1962’, Journal of Economic History, lxxxi (2021).

Paul Sagar, John Christensen and Nicholas Shaxson, ‘British Government Attitudes to British Tax Havens: An Examination of Whitehall Responses to the Growth of Tax Havens in British Dependent Territories from 1967 to 1975’, in Jeremy Leaman and Attiya Waris (eds.), Tax Justice and the Political Economy of Global Capitalism, 1945 to the Present (Oxford, 2013), 107–32.

Jason C. Sharman, Havens in a Storm: The Struggle for Global Tax Regulation (Ithaca, NY, 2006), 20–48; Ronan Palan, Richard Murphy and Christian Chavagneux, Tax Havens: How Globalization Really Works (Ithaca, NY, 2010), 17–45; Ogle, ‘Archipelago Capitalism’, 1442; Guex and Buclin (eds.), Tax Evasion and Tax Havens, 13–19; Sébastien Lafitte, ‘The Market for Tax Havens’ (Job Market Paper, École Normale Supérieure Paris-Saclay, 7 Feb. 2023); Lukas Hakelberg, ‘The Whiteness of Wealth Management: Colonial Economic Structure, Racism, and the Emergence of Tax Havens in the Global South’ (WOWMA) (accepted ERC Grant project, June 2023 — text communicated by the author); Dharmapala, ‘Overview of the Characteristics of Tax Havens’. The past few years have also seen a flurry of books chronicling libertarian and secessionist projects in the global economy, including: Quinn Slobodian, Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World without Democracy (London, 2023).

Quentin Deluermoz and Pierre Singaravélou, A Past of Possibilities: A History of What Could Have Been (New Haven, CT, 2021).

‘Excès de zèle’, Le Journal de la Bourse (13 Oct. 1938). The article mentions the imperial tax conflict studied in this article and complains about the Ministry’s decision to treat the rubber firm ‘Compagnie de l’Equateur’ as delinquent because it moved headquarters from Paris to Duala.

Andrew W. M. Smith and Chris Jeppesen, Britain, France, and the Decolonization of Africa: Future Imperfect? (London, 2017), 9.

Andrew W. M. Smith, ‘Future Imperfect: Colonial Futures, Contingencies and the End of French Empire’, in Smith and Jeppesen, Britain, France, and the Decolonization of Africa, 87–110. On the present time as one pre-empted by neoliberalism, see Jérôme Baschet, ‘Reopening the Future: Emerging Worlds and Novel Historical Futures’, History and Theory, lxi (2022), 200.

See the interventions in ‘Up from Neoliberalism’, Dissent (Fall 2023). See also current discussions about the pending ‘tax haven reshuffle’ following the introduction of the G20-led global corporate tax reform in 2021: <https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/16/oecd-tax-reform-g-20s-crackdown-may-create-a-new-kind-of-tax-haven.html> (accessed 13 June 2024).

‘Tax shelter’ is the expression used by Vanessa Ogle to refer to colonies in ‘Archipelago Capitalism’, 1438. I understand ‘tax shelter’ to mean ‘low-tax jurisdiction’. But why not use ‘tax haven’?

Ogle identifies these historical junctures as the two first phases of tax haven expansion. See Ogle, ‘ “Funk Money” ’, 7. For another periodization, see Guex and Buclin (eds.), Tax Evasion and Tax Havens, 10–11.

Olivier Serra, ‘Naissance de l’imposition du revenu des capitaux mobiliers en France’, in Luisa Brunori et al. (eds.), Le Droit face à l’économie sans travail, Tome I: Sources intellectuelles, acteurs, résolution des conflits (Paris, 2019), 265–82.

On the role of state centralization in French tax history, see Kimberly J. Morgan and Monica Prasad, ‘The Origins of Tax Systems: A French-American Comparison’, American Journal of Sociology, cxiv (2009), 1350–94.

Binder, Offshore Finance and State Power, 43–76.

Vanessa Ogle speaks of an ‘imperial fiscal frontier’ in ‘ “Funk Money” ’, 21.

Headquarter transfers were ‘the typical technique to avoid international taxation during that period’ according to Ryo Izawa, ‘Corporate Structural Change for Tax Avoidance: British Multinational Enterprises and International Double Taxation between the First and Second World Wars’, Business History, lxiv (2022), 719. The National Archives, London, IR 40/2567B: Finance Act 1920, Section 27, Relief in respect of Dominion income tax. See also Robert Willis, ‘Great Britain’s Part in the Development of Double Taxation Relief’, British Tax Review, cclxx (1965), 270–82; Ogle, ‘ “Funk Money” ’, 236–7.

Sarah Stockwell, ‘Trade, Empire, and the Fiscal Context of Imperial Business during Decolonization’, Economic History Review, lvii (2004); Simon Mollan, Billy Frank and Kevin Tennent, ‘Changing Corporate Domicile: The Case of the Rhodesian Selection Trust Companies’, Business History, lxiv (2022); James Hollis and Christopher McKenna (eds.), ‘The Emergence of the Offshore Economy, 1914–1939’, in Kenneth Lipartito and Lisa Jacobson, Capitalism’s Hidden Worlds (Philadelphia, 2020).

I borrow this expression from Ian Kumekawa, ‘Imperial Schemes: Empire and the Rise of the British Business-State, 1914–1939’, Enterprise and Society, xxiii (2022).

Arthur Asseraf, ‘L’Empire qui voulait être monde, 1815–1930’, in Pierre Singaravélou (ed.), Colonisations: notre histoire (Paris, 2023); John Darwin, The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (Cambridge, 2009).