-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nathaniel Morris, Crisis, corruption and state-led development in the making of the Mexican drug trade, Past & Present, Volume 265, Issue 1, November 2024, Pages 235–273, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtad028

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

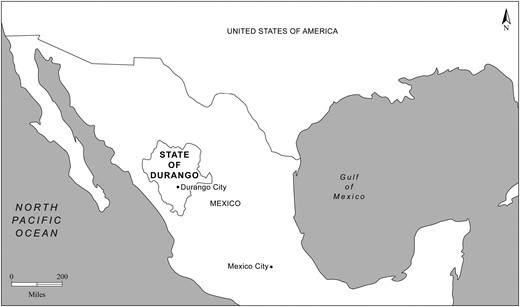

The state of Durango has long been a centre of Mexican heroin production and an important node in transnational drug trafficking networks. As early as 1944, it was the site of one of the biggest drug busts in Mexican history, when an opium poppy plantation the size of 325 football pitches, irrigated by a purpose-built aqueduct, was discovered in the state’s northern mountains. By the mid 1970s, a combination of kinship ties and concrete connected these poppy fields directly with the US drug market hub of Chicago, Illinois, along a route known as the ‘heroin highway’, which helped Mexico become the supplier of 90 per cent of US heroin. But how did a poor, underpopulated and overwhelmingly rural state become a major player in the billion-dollar US–Mexican drug trade? This article shows that in Durango, the rise of heroin production and trafficking were integral aspects of local processes of social, political and economic modernization. Stimulated by the Mexican and US governments’ promotion of infrastructural improvements and mass migration, and protected by representatives of Mexico’s post-revolutionary political system, the drug trade in turn fuelled further ‘licit’ economic development, making it part of the very foundation of Mexico as we know it today.

When US treasury agent Salvador C. Peña left his desk in Mexico City for the mountains of Durango in early 1944, he had much to be suspicious about. The men whose poppy fields he and his men had been sent to destroy were known to be heavily armed; some of the officials supposedly supporting his mission were likely in the pay of drug traffickers; and the loyalty of his Mexican military escort was dubious. But in a poor northern state (see Map 1) still regarded as a minor player in the burgeoning US–Mexican drug trade, Peña never expected to stumble upon one of the largest opium poppy plantations ever discovered in Mexico: an area of 232 hectares — equivalent to 325 football pitches — watered by ‘a great work of irrigation . . . a concrete tunnel of nearly two kilometres of length that cut across a hill’. The irrigation system was fed by its own dam, an infrastructural feat far beyond anything the Mexican government had been willing or able to provide to peasant communities in this marginal corner of the country.1 And according to Peña’s initial estimates, the poppies growing in these fields would together have yielded around four and a half tonnes of crude opium per harvest — a huge amount by any standards, and enough to produce 450 kilograms of pure heroin (today worth more than US$27 million).2 But Peña admitted that this plantation, in Durango’s remote northern municipality of Tepehuanes, was so densely planted and well watered that it could have produced twice that quantity of opium, or more, at each harvest — of which two or even three per year would have been possible.3

The story of Agent Peña’s 1944 discovery of the poppy fields of Tepehuanes — which extended over an area forty-six times larger than the biggest plantation found anywhere in Mexico in recent years4 — is one of many examples of Durango’s long-standing significance as a centre of Mexican opium production and international heroin trafficking. A history that is all the more important today, as the death toll of the ongoing US opiate epidemic reaches into the hundreds of thousands, and overdoses have overtaken road accidents as the most common cause of death in American men under the age of 50;5 while in Mexico, the ‘war on the drug cartels’ launched by the government in 2006 has claimed hundreds of thousands more lives, and induced violent social breakdown across much of the country.6

Despite its immense — and tragic — contemporary importance, few historians have studied the Mexican heroin trade in much depth, despite the existence of a vibrant and ever-expanding historiography concerning drug production, trafficking and policy in Mexico, ranging from Campos’s ground-breaking work on marijuana and prohibition, and Osorno’s in-depth account of the origins of the notorious Sinaloa Cartel, to more recent, edited collections dealing with the country’s ongoing ‘drug war’, and the regional idiosyncrasies of trafficking networks.7 But Mexican opium and heroin as discrete subjects of historical analysis have been largely overlooked, especially when compared to the extensive research done on opium and heroin production in Asia and the Middle East.8 The work of Benjamin Smith and Luis Astorga are notable exceptions to this rule, but their primary focus has been on heroin production and trafficking in the states of Sinaloa and the US–Mexican borderlands.9 Scholarly analyses of the opium and heroin trades in Durango are limited to an excellent early study written by a pair of political scientists in 1980, and two more recently published book chapters: one by Elaine Carey, the other by myself. All three of these analyses, however, barely touch on the emergence of local opium production and regional trafficking routes, instead focusing almost entirely on the mechanics of heroin smuggling and distribution operations between Durango and Chicago from the mid 1970s.10

The present article asserts Durango’s central place in the longer history of the Mexican opium and heroin trades. Based on research in a range of archives,11 data taken from regional newspapers and local historical chronicles,12 and insights gleaned from the scholarly literature both on the nexus between drugs and development in Latin America and beyond,13 and on the regional dynamics of state formation in Mexico more specifically,14 it outlines the social, political and economic factors — some of them common to drug-producing centres across the globe, others particular to Mexico, or even unique to Durango itself — that helped it to become a major player in the US–Mexican drug trade. Above all, in line with recent analyses that causally link illicit cocaine booms in Peru and Bolivia to the failures of ‘state-led, mid-century modernizing colonization projects’;15 that identify similar connections between ‘state interventions . . . carried out in pursuit of agrarian development and nation-state formation’ and the rise of the marijuana trade on Colombia’s Caribbean coast;16 and that argue the emergence of industrial heroin production in Central Asia was an ‘unintended consequence’ of US-backed development programmes,17 it shows that the increasing importance of Durango’s drug trade was an integral part of local processes of social, political and economic modernization, above all during the so-called ‘Mexican Miracle’ of the 1940s–70s.

The idea of the ‘Mexican Miracle’ — a touchstone for politicians, economists, journalists and much of Mexican society at large during the second half of the twentieth century — sees the revolutionary upheaval of the 1920s and 1930s as giving way to stable, hegemonic one-party rule in the 1940s.18 This set the stage for the arrival and consolidation over the ensuing four decades of a Mexican version of the ‘technocratic, capitalist model of modernity that has been dominant since the mid-nineteenth century’ across most of Latin America,19 and which, in line with the post-war ‘Truman doctrine’,20 prioritized urbanization, industrialization, infrastructural expansion, rapid population growth, mass international migration and the ‘growing economic and political integration of the Western Hemisphere, and particularly new connections between the United States and Mexico’.21 Mexico’s one-party state ‘invested hugely in public services’ and promoted industrial and agricultural development, and as a result ‘the national economy more than doubled in size’,22 while ‘literacy and longevity rose alongside [it]’.23 Mexican society underwent similar transformations, too, pulling it in an increasingly capitalist, consumerist direction.

Contrary to the boosterism of many observers at the time,24 scholars have long since accepted that this economic ‘golden age’ had significant costs.25 The promotion of industry and agribusiness came at the expense of informal workers, urban women, and above all the country’s peasantry, who suffered a ‘systematic transfer of resources from countryside to city’. The period was also marked by the increasingly brutal state repression of anyone who protested against such inequity.26 And the evidence from Durango points to the existence of a further and hitherto overlooked dark side to the ‘Mexican Miracle’: the unprecedented expansion of drug production and trafficking, to which rural people turned in order to (literally) capitalize on Mexico’s modernization while minimizing its negative impacts on themselves and their communities.

Case studies of drug booms in Peru and Colombia in the 1960s and 1970s, and in Mexico’s southern states from the 1980s onwards, have suggested that it is in order to gain access to political, economic and social ‘modernity’, from a position outside it, that marginalized rural populations enter the drug trade.27 But in Durango, I argue that it was in fact the prior arrival of this modernity as early as the 1920s, and its uneven and often disruptive impacts on rural society, that in the first place created the conditions for an illicit local drug boom. There, the emergence of opium production and heroin trafficking and their growth into major local industries was a direct consequence of a declining international market for the products of the regional mining sector; the stabilization of Mexico’s post-revolutionary political system; the modernization of Mexican agriculture and the expansion of the country’s transport infrastructure; and, not least, the use of Mexican labour to fuel industrial and especially agricultural development in the USA itself, which ‘helped to transform southwestern agriculture, especially the fields of California, into the richest and most productive on the planet’.28

The case of Durango also attests to how the profits generated by illicit activities have helped to fuel ‘licit’ economic development in Mexico.29 As early as 1944 drug money was being funnelled back into the sort of agricultural infrastructure — dams, aqueducts and back-woods dirt roads — that were discovered during the Tepehuanes poppy plantation bust. By the 1970s, as the Herrera family completed the ‘modernization’ of Durango’s heroin trade, the cash they earned wholesaling heroin in Chicago was invested throughout Durango and beyond in ‘gas stations, restaurants, dancehalls, discotheques, construction companies [with] drainage and road construction contracts from the state government . . . bars, mansions, ranches and airlines’.30 In Durango, then, a booming drug trade was intrinsic to the economic growth that characterized the ‘Mexican Miracle’. This fact challenges a central policy paradigm of governments and NGOs alike: that licit and illicit economies are dichotomous, and more ‘development’ is therefore the best path out of dependence on the drug trade.31 Instead, the case of Durango strengthens the argument that developmentalist state policies have, more often than not, actually sparked drug booms in Asia and the Americas,32 and contributes to an expanding historiography exploring the many and contested histories of ‘development’ at global level.33

Drug money also helped to support a variety of political actors from the 1940s onwards, from the police chiefs, municipal presidents and military commanders who promoted and protected poppy cultivation in Durango’s mountains, to powerful cliques in Mexico City adjacent to the president himself. By the 1980s, the Herrera family controlled the appointments of ‘chiefs of police at the town and municipal levels, directors of state police, mayors and police agents in every law-enforcement agency . . . Jaime Herrera himself is said to encourage bright young men to pursue political careers’.34 The story of how Durango’s ‘heroin highway’ was built therefore complicates the narrative — increasingly central to populist political campaigns throughout the Global South — that strong states are somehow antithetical to organized crime.35 Instead, it adds weight to the idea that not only ‘corruption’, but total, full-on criminality, have been essential to the formation of ‘modern’ nation states both in post-revolutionary Mexico, and much of the rest of the world besides.36

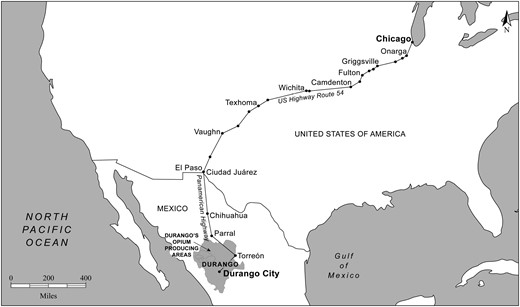

The story of Durango’s drug trade has four main chapters, around which this article is structured: first, the birth and initial expansion of an export-orientated opium agriculture in the mountains of Durango in the 1930s; second, the institutionalization of US-backed, militarized government crackdowns against opium production and trafficking, and, at the same time, of high-level political and military protection of and active involvement in these illicit industries in the 1940s and 1950s; then, the development, in the 1950s and 1960s, of the physical and social infrastructure — above all a growing network of new roads and highways, and a growing Duranguense immigrant diaspora in the USA — that allowed Durango’s traffickers to become independent of networks based in the neighbouring state of Sinaloa, and instead start smuggling locally processed heroin along new routes connecting Durango directly to US markets; and, finally, the emergence of the Herrera trafficking organization — made up of merchants, police officers and US migrants from a small town on the main road between Durango’s mountains and the state capital — who modernized the transnational transport and state-side distribution of locally produced heroin in the 1960s and 1970s.

In so doing, the Herreras completed the half-century-long process of building the ‘heroin highway’ — more than just a road, but rather a whole ‘farm to arm’ network of peasants, traders, cops, chemists, smugglers, politicians, dealers and consumers — that linked the poppy fields of Durango to the streets of Chicago. All four of these phases were shaped by the interplay of national and international economic crises, corruption on the part of opportunistic representatives of Mexico’s post-revolutionary state, and regional, national and international development policies promoted by both the Mexican and US governments as they strove to bring a particular vision of social, economic and political ‘modernity’ to rural Mexico.37 That the drug trade was thus part of the very foundation of modern Mexico helps, in turn, to explain its remarkable resilience, despite the billions of dollars and millions of lives consumed by more than a century’s worth of campaigns against it.

I Crisis, corruption, and the origins of the drug trade in Durango, 1930–1945

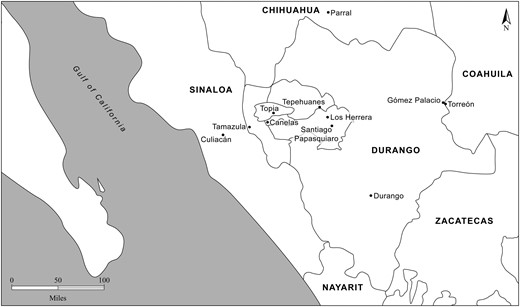

Of Mexico’s thirty-two federal entities, Durango is the fourth largest, covering some 123,317 square kilometres (making it almost the same size as England). Geographically, it consists of three distinct zones: a heavily forested strip in the west, dominated by the mountains of the Sierra Madre Occidental and bordering the states of Sinaloa and Chihuahua (see Map 2); a temperate, fertile region in the centre, where the state’s eponymous capital city is located; and vast, arid plains in the east. Durango is a largely rural state, whose main industries have traditionally included forestry, mining, large-scale cattle ranching and small-scale farming. And it has always been sparsely inhabited: even today it has the second-lowest population density in Mexico, at under fifteen people per square kilometre.38

THE OPIUM-PRODUCING MUNICIPALITIES OF NORTHERN DURANGO

Map drawn by Louise Buglass.

Durango had been the site of various economic booms during the nineteenth century, but with the outbreak of the Revolution in 1910, it entered a period of seemingly permanent decline.39 Over the next three decades, violent conflicts between rival revolutionary factions, anti-government revolts led by Durango’s pre-eminent revolutionary caciques (political bosses), the Arrieta brothers, and then the Catholic-inspired Cristero Rebellion, consumed much of the state. The violence led to mass emigration and many thousands of deaths: while in 1900 Durango was northern Mexico’s most populous entity, by 1950 it was second-to-last,40 having suffered significantly greater demographic losses than any other Mexican state in the first half of the twentieth century, including 30 per cent of its population between 1910 and 1921 alone.41

Throughout the revolutionary period, rebels, bandits and government-armed militias alike ransacked the state’s cattle ranches and haciendas, carrying off tens of thousands of heads of cattle,42 and raided the US-owned mines in Durango’s northern mountains — including, at San Dimas and Tayoltita, some of the largest gold and silver mines in Latin America43 — stealing dynamite supplies and looting company offices, kidnapping US citizens for ransom and forcing other workers to flee.44 The social and economic impacts of the constant violence were compounded by the Great Depression, which reduced US demand for precious metals and US companies’ ability to invest in extraction, dealing a further blow to this important regional industry.45 The closure of the gold, silver and lead mines that were the lifeblood of the economy in municipalities like Tamazula and Topia, and had become a vital source of temporary, dry-season employment for local peasants, left these areas socially and politically fractured, economically depressed and littered with ‘ghost towns’.46

Many of northern Durango’s battled-scarred and poverty-stricken peasants and former miners adapted to the blows that national and global turbulence dealt them by turning to opium poppies as a profitable — and, since 1920, illicit — cash crop: one that could be easily cultivated even on poor mountain soils, and was shielded by the rugged terrain of their homeland from the enforcers of prohibitionist laws. In 1931, one such enforcer, Juan N. Requena, was sent to investigate reports of opium production in the mountains of north-western Durango. Requena was not a policeman or state security official per se, but rather a covert operative of the Mexican Secretariat of Health’s ‘Department of Public Sanitation’, the Federal body charged since 1920 with cracking down on the production, sale and use of drugs and alcohol as part of the post-revolutionary regime’s crusade against ‘degeneration’.47 Agent Requena reported back to his superiors that

In the state of Durango, to the west of the town of Topia . . . there is an immense amount of land given over to the cultivation of poppies, and I was informed by an individual of American nationality, Mr. Hon Berk, that he believes that the Chinese found in those places dedicate themselves to the production of opium.48

Requena’s claims of Chinese involvement in Durango’s opium trade echo similar, self-consciously nationalist (and often outright racist) stories published in regional newspapers.49 But elsewhere in Requena’s report it becomes evident that the most important players in the local opium game were actually Mexicans: more specifically, growers and traffickers from just across Durango’s state border with Sinaloa. In 1929, members of Sinaloa’s ethnically Mexican rural middle class — ‘artisans, ranchers, mid-size farmers, merchants, and miners’ — had violently seized control of the state’s nascent local opium industry from elements of the local Chinese community who had previously ‘cultivated small amounts of poppies and harvested the residue or goma for personal use or for sale in opium dens’.50 From their new position of dominance over opium production in Sinaloa,51 it seems these traffickers soon expanded their operations into Durango. In this they would have been aided by the traditionally close cultural, political, economic and kinship ties between the inhabitants of both sides of the Sinaloa–Durango border,52 and by the fact that it made more sense for Durango’s early poppy farmers to move their opium west into Sinaloa, via the same mule trails that local peasants and miners had for centuries depended on for commercial exchange with the cities of the Pacific Coast,53 than to attempt moving it east along almost non-existent roads towards the more distant commercial centres of Durango’s interior.54

Opium cultivation spread slowly but surely through the mountains of Durango as the 1930s progressed, and then boomed after the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, which dealt a further blow to Durango’s mining industry,55 while at the same time greatly stimulating US demand for Mexican heroin by cutting off US markets from both European and Asian suppliers.56 In 1944, the assistant US military attaché in Mexico reported that Mexico had become ‘one of the largest producers of opium in the world . . . almost all’ of which was exported to the USA.57 Growers in Durango, aided by the local authorities, were clearly doing their best to keep up with demand: in 1945, a peasant from Tamazula arrested in Sinaloa while trying to find a buyer for half a kilo of opium confessed that, in his home village,

the whole world grows [poppies] and despite the existence of a Mayor and Authorities there, they trouble no-one nor enforce any prohibitions, so for him it seemed easy to grow them, especially given the bad [economic] situation in which the declarant found himself; he had harvested a little more than a kilo of opium gum, of which three-quarters he sold to a short, fat man wearing a cowboy hat, whose name he did not know, who visited the declarant in order to buy [the opium] from him.58

Despite the central government’s official prohibition of such activities, regional authorities and local caciques in Sinaloa and neighbouring parts of Durango likely supported the opium industry in order to share in its profits, and because they believed the ‘high wages and commensurate purchasing power’ that it provided local peasants, ‘dissuaded most from seeking further land reform’, helping to stabilize these previously restive regions and setting the stage for their further political and economic integration into the modernizing Mexican nation state.59 The increasing quantities of raw opium produced in Durango in this period were subsequently refined either into smoking opium or crude heroin in secret laboratories in Sinaloa.60 The finished product was smuggled north along the Pacific coast railway to the border cities of Tijuana and Mexicali, for sale to American distributors. Judicial case files show that by the mid 1940s, increasing numbers of individuals from Durango had also entered this side of the trade, becoming full-time traffickers based in cities on the US–Mexican border, where the number of opium-related arrests of individuals from Durango greatly increased.61

II Government–trafficker pacts and US entanglements, 1945–1955

The election of Manuel Ávila Camacho to the presidency in 1940 marked the end of the Mexican Revolution and the beginning of a sixty-year period of ‘soft authoritarianism’ under hegemonic one-party rule — the so-called ‘perfect dictatorship’.62 Successive Mexican governments steered clear of social, political or economic radicalism, instead promoting ‘stability’ at home, increasing hemispheric co-operation abroad (not least, in the context of the Second World War and then the early Cold War, in matters of security), and the development of Mexican industry and ‘modernization’ of the country more generally with the aid of US investment.63 As a consequence, throughout the 1940s ‘Mexican officials worked extensively with US agencies to legitimize a new phase in bilateral relations, while . . . they also strained to secure policy concessions and deflect unwanted US intrusions’.64

In addition to co-ordinating defence policy, creating new trade agreements, sharing new agricultural technology, organizing new binational transport networks and jointly eradicating an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in southern and central Mexico,65 US and Mexican officials collaborated on a series of anti-drugs campaigns. Driven by the aggressive campaigning of officials like Harry J. Anslinger, the US government took an increasingly hard line on drugs in general, and opiates in particular, both domestically and internationally.66 Believing that ‘it is more effective to destroy the opium at its source in Mexico than to prevent effectively the entrance of the drug into the US’,67 it began to sponsor, co-organize and supervise the militarized eradication of poppy crops in Mexican states including Sinaloa, Chihuahua and Durango.68

However, ‘while political elites in both countries increasingly accepted the principle and necessity of institutionalized co-operation on a host of issues, the practical details left ample room for tensions and conflict’,69 and US anti-opium efforts in Mexico were ultimately rendered ineffective by the existence of what US officials concurrently recognized as the ‘strong political influences and the “interests” of certain politicos in this trade’.70 Such government–trafficker pacts were built on identical foundations to the one-party political system then emerging in these same areas of rural Mexico: namely durable patron–client relationships between politicians, military commanders and local elites, combined with newer forms of post-revolutionary caciquismo (‘boss politics’) that helped to harness the (always conditional) support of the middle and lower classes. By protecting, taxing and even directly investing in opium production and trafficking in this period, representatives of the Mexican state avoided conflict and gained additional power and wealth, while drug profits buoyed the local economy. This eased the further integration, both political and economic, of marginalized rural regions like north-western Durango into the modern Mexican mainstream.71

The very earliest Mexican opium eradication expedition — part-funded by the US Treasury Department, observed by US drugs agents, and carried out by a mixed team of Mexican sanitary officials, police officers and soldiers — took place in Sinaloa in 1938. But such campaigns only became ‘institutionalized as state policy concurrently with the process of state centralization occurring in Mexico in the early 1940s’.72 The first eradication expedition to include Durango was launched in 1944, and focused on the state’s northern municipalities of Tamazula, Topia and Tepehuanes. It was co-ordinated by a ‘special employee’ of the US Treasury Department’s drug control division, Salvador Peña, based at the US embassy in Mexico City.73 The US Treasury also contributed 2,000 Mexican pesos towards the Durango expedition — although Peña noted this was a pittance compared with the fortunes being made by the country’s traffickers, and even some peasant growers.74

Within a week, the expedition had uncovered the 232-hectare poppy plantation described at the beginning of this article. It was located not in the long-standing opium-production hotspots of Tamazula or Topia (directly bordering Sinaloa), but rather further inland in the municipality of Tepehuanes, on the eastern slopes of Durango’s Sierra Madre mountains: clear evidence of the spread of opium production into areas closer to the city of Durango during the 1940s. Given that the plantation’s irrigation system would have enabled two or even three such crops a year, it is likely that by 1944, tens of millions of dollars’ worth of opium was being produced in the municipality of Tepehuanes alone. Little wonder, then, that the traffickers who controlled these fields had been able to construct their two-kilometre concrete aqueduct: a true feat of engineering in such a remote and mountainous region.

In the self-consciously paternalist fashion that would become typical of many Latin American traffickers, they had promised to hand the canal over to the local peasants once their five-year rents were up.75 In this sense a drug ring proved more effective in providing a peasant community with irrigation — one of the foundational elements of ‘modernized’ agriculture — than the post-revolutionary Mexican state itself, which never managed to ‘fully overcome’ the issue of the redistribution of water resources.76 Indeed, official inadequacy in this respect was especially stark in Durango, where a failure to ‘expand the frontier of irrigated agriculture over the course of the twentieth century’ has been identified as a key cause in the state’s long-term economic decline.77 This decline was also locally offset by the income from small-scale poppy cultivation, which allowed peasants to buy previously unaffordable consumer goods such as ‘radios, arms, cars and even American tinned foods’, while cattle ownership — a key marker of status in peasant society — also rose exponentially throughout north-western Mexico during this period.78 Thus in the mountains of Durango, as in the jungle communities at the centre of Peru’s concurrent cocaine boom, the drug trade offered marginalized rural populations a more promising route to ‘development’ than the apparently empty words of a distant state.79

The Tepehuanes case also provides clear evidence of the increasingly high-level collusion between military officers stationed in lowland Durango, and opium growers up in the mountains. The expedition’s army escort deliberately delayed their departure, and by the time they arrived in the area, the local opium producers (or gomeros) had been tipped off and successfully harvested most of their illicit crop before disappearing into the hills. A US official suggested that high-ranking military or political officials based in the state capital might have warned the gomeros before the inspector and his assistant even left Durango city. Indeed, a military officer, Major Gorgonio Acuña, was rumoured to be the main ‘go-between for the growers and the purchasers for the opium that finds an outlet on the west coast’.80 As in much of Mexico in this period, then, the rapid expansion of the drug trade in Durango depended not just on the desperation of farmers and miners and the entrepreneurship of merchants, but also on the active support of local representatives of a supposedly prohibitionist state for those who broke the nation’s laws against poppy cultivation and opium production.81

Chief among these ‘official traffickers’ in the north-west of Mexico were members of the de la Rocha family of Copalquín, Tamazula, who were directly involved in the local opium trade while holding positions as police commanders in the mountainous Sinaloa–Durango borderlands. Only a few months after the initial Tepehuanes expedition, the chief of Tamazula’s municipal police force confidentially warned President Avila Camacho that

Since last year the cultivation of poppies has been spreading, protected by Aureliano de la Rocha, Chief of Judicial Police in this municipality and in that of Topia . . . it has come to my knowledge that he helps various inhabitants of the aforementioned settlements, and protects them by appointing them as agents of the judicial police.

I am writing to you directly, bypassing the state government, because Mr. de la Rocha claims that an official in the Government of Durango is a relative of his; that [the latter] is on top of everything; it is he who has managed to win approval for [de la Rocha’s] appointments of police agents.82

However, the Mexican Secretariat of Health, regional military authorities, and the US consulate in Durango ignored these warnings when they put together a follow-up eradication expedition in 1945. In command was Brigadier General Simón Díaz Estrada, who subsequently claimed the mission was a stunning success that had resulted in the destruction of 250 hectares of poppies in Tepehuanes, Topia, Canelas and Tamazula. However, General Estrada made no arrests, seized no opium, sent no official report to the consulate, and provided them with only three photographs of a single poppy field. An American secret agent reported back to the US consulate that this was, in fact, the only one Estrada’s men had managed to destroy, despite the existence of so many in the region.83

It is perhaps no coincidence that Judicial Police Chief Aureliano de la Rocha and several of his trusted subordinates had ‘aided’ Estrada’s abortive expedition, on the direct orders of Durango’s state governor Blas Corral Martínez (himself a native of Tepehuanes). The following year, Aureliano de la Rocha was himself appointed commander-in-chief of a third eradication campaign covering the entire opium-growing ‘Golden Triangle’ region that spanned neighbouring areas of Durango, Sinaloa and Chihuahua.84 Unsurprisingly, the new expedition again accomplished little in Durango, finding no new poppy fields in Tepehuanes (despite the existence of such extensive plantations there in 1944), and discovering in Topia only a few plantations that had not already been harvested and then destroyed.85

Around the middle of 1947, however, Aureliano and other high-ranking members of the de la Rocha family dramatically fell from official favour. This was likely linked to the recent accession of Miguel Alemán Valdés to the presidency, which had triggered the outbreak of violent power struggles in the Mexican underworld over control of drug-trafficking protection rackets between an upstart clique linked to the new president’s close associate Colonel Carlos I. Serrano, and a range of old-guard politicians and traffickers.86 Colonel Serrano had been fund manager for Alemán’s presidential campaign, which brought him into contact with ‘a range of smugglers, who agreed to make lavish contributions in return for protection’. He soon moved directly into opium trafficking himself, and after Alemán’s election set out to bring Mexico’s drug trade — at this point ‘worth an annual US$20 million according to the US Treasury and US$60 million according to Alemán’s private secretary’ — under more centralized federal control.87

Serrano’s chief weapon in this campaign was the recently founded Federal Directorate of Security (DFS), of which he himself was commander-in-chief. The agency was riddled with corruption from top to bottom: US drugs officials reported in 1947 that ‘anyone with a past record as a crooked narcotics enforcement officer needs no other qualification to be accepted as an agent’.88 The agency was perfectly placed to muscle in on Mexico’s national drug trade by attacking smaller traffickers under the pretext of a new Federal government-led ‘permanent campaign’ against drugs, which had ceased to be the ‘fragmented and temporary endeavour’ of old, and was now a ‘policy to which the Mexican president committed his prestige’.89

In this context, Aureliano de la Rocha and his older brother, Francisco, then commander of the judicial police in Sinaloa, his younger brother Rafael, a military officer and state deputy for Tamazula, and their relative, regional police chief Átalo de la Rocha, were all publicly accused of involvement in the drug trade by journalists and rival politicians and military commanders.90 A further blow came in early 1948, when Durango’s new state governor, José Ramón Valdez, ordered an ambitious new poppy eradication campaign in the mountains of northern Durango. The campaign was put under the command of General Dámaso Carrasco, an old Duranguense veteran of the Revolution, and extended east beyond Topia, Tamazula and Tepehuanes into Canelas and Santiago Papasquiaro.91 During a fifty-three-day expedition across more than a thousand kilometres of mountainous terrain, Carrasco’s forces located and destroyed 117 poppy plantations covering nearly eighteen hectares, found an additional seventy-seven plantations, covering eight hectares, which had already been harvested and destroyed, and arrested ten men and women for growing poppies. All in all, Carrasco claimed to have prevented the harvest of a total of 1,300 kilograms of opium, which, given recent increases in its value due to the ongoing national-level conflicts between different cliques of traffickers and politicians, was estimated to have been worth more than US$14.5 million once it reached the USA.92 These figures show that Durango’s opium industry continued to generate extraordinary profits for a wide range of different actors during this period; but also that local poppy plantations were shrinking and dispersing under government pressure, as growers, traffickers and their allies in the government adapted to the campaigns being waged against them.

While on campaign in the mountains, General Carrasco also dissolved the municipal government of Tamazula, and arrested on drugs charges the recently elected mayor — no less than Aureliano de la Rocha himself — who was denounced by local peasants as the ‘biggest and most vile poisoner of humanity with narcotics that there is’.93 However, as in so many Latin American drug-producing regions in this period, a range of other local, regional and federal government officials remained deeply involved in Durango’s drug trade, which was more profitable than ever thanks to the booming demand in the USA.94 Among the new generation of politically connected caciques who took over from the disgraced de la Rocha clan were Tamazula’s Chávez León brothers — Ezequiel, Conrad and José María — ‘who held posts as the local judge, the head of the local branch of the state police, and a policeman’.95 The family had reputedly been involved in local opium trafficking since at least the mid 1940s, well-protected by higher officials.96 By 1955 they were confident enough of their power to drunkenly provoke a gunfight with a military unit recently posted to Tamazula to clamp down on the vigorous local drug trade and disarm the local population.97

US government pressure, and periodic political and military crackdowns waged by Mexican state agencies, were thus no match for the demands of the USA’s own citizens for Mexican opiates, or for the corruption of Mexican politicians and military officials, who stood to gain wealth and power by protecting or actively participating in the drug trade, while risking violent retribution if they threatened their compatriots’ illegal crops.98 Continued eradication campaigns in north-western Durango, a region long ‘distinguished for its rebellion and its disorders’, therefore remained ineffective.99 Instead, the amount of land dedicated to poppy cultivation, and the quantities of opium produced by those who cultivated them, continued to expand there throughout the 1950s,100 earning Tamazula, Tepehuanes and Topia permanent positions amongst Mexico’s top ten opium-producing municipalities.101

III Local roads, international highways and a revolution in Durango’s drug trade

Durango’s mid-twentieth-century opium boom coincided with important changes in the dynamics of drug trafficking in the state and beyond. In particular, the expansion of Mexico’s road network in response to Mexican state-building goals, US commercial aims, and the security issues posed first by the Second World War and then by the Cold War, helped to shift the axis of Durango’s opium trade away from older Pacific Coast smuggling routes and towards the centre-north of the country. This allowed Duranguense traffickers to free themselves from Sinaloan influence and develop their own smuggling networks, which connected Durango to the US–Mexican border at Ciudad Juárez via Parral and Chihuahua city.

In the same way as railways had been envisioned as harbingers of ‘progress’ in Mexico (and much of the rest of world) in the nineteenth century,102 the country’s post-revolutionary governments saw the building of roads across the nation as essential to ‘strengthening the national government and connecting a nation torn by factionalism’.103 By connecting the countryside with the cities, and zones of agricultural and industrial production with market hubs,104 they believed new networks of local roads and national highways would ‘expand the reach of the national economy, dismantle regional economic isolation, and break the economic power of caciques’.105 Roads would also help to promote capitalist development in a country with strong, communist-influenced labour and peasant movements, weakening ‘the power of railroad labor and pav[ing] the way for a more acquiescent work force’.106 At the same time, peasants and workers in many areas also saw new roads and the motorized transport they enabled as key to their ‘liberation’ from the political and economic oppression of local caciques, who had previously controlled local trade via monopolies over mule trains and provincial storage depots.107 Thus post-revolutionary road-building programmes were not just the top-down project of a modernizing and centralizing state apparatus, but also a product of grassroots demands for ‘progress’ and ‘modernity’.108

Many US politicians and businessmen were also enthused by the idea of expanding Mexico’s road network and connecting it to their country’s own in order to promote increased trade with both Mexico and the rest of the Americas.109 Plans for what would become the Pan-American Highway were put forward as early as 1923 at the International Conference of American States. Its promoters planned to connect road systems already running from the American Midwest down to Texas, and from there cross over into Mexico at Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas. The idea was that the Pan-American Highway would eventually span the entire length of the continent, from the centre of the USA to Buenos Aires, Argentina.110

Work on this international highway, as well as Mexico’s regional road network, slowed in the 1930s in the wake of spending cuts forced by the Great Depression.111 But from 1939, ‘a world war, security concerns, and an increased need to move goods from the United States’ gave new impetus to Mexico’s road-building programmes. Fearing Axis designs on the western hemisphere, both the Mexican and US governments ‘worked to increase the interconnectedness of Mexican and American road systems in case the need arose to move troops and military equipment’.112 As the two nations became better connected in the 1940s, ‘the US and Mexican economies become more closely linked’, which only increased the need for the further expansion and integration of their road networks.113 With the subsequent outbreak of the Cold War and Alemán’s election as president of Mexico in 1946, the US and Mexican governments drew closer thanks to their shared anti-communism and commitment to ‘hemispheric defence’ under the 1947 Rio Treaty, paving the way for the further ‘opening up of Mexico to US capital’.114

By 1949, more than sixty thousand kilometres of roads criss-crossed Mexico, including 21,422 kilometres of highway.115 A year later President Alemán officially inaugurated Mexico’s first fully completed stretch of the Pan-American Highway, which ran 3,446 kilometres from the country’s northern border with the USA at Ciudad Juárez, south through Chihuahua, Parral, Torreón and Durango to Mexico City, and then on towards the Guatemalan frontier.116 Its construction created an alternate north–south trade route to the old Central Railway, significantly ‘increasing the possibilities of commercial interchange between the US and Mexico’.117 The building of these new highways, and networks of feeder roads to connect these major transport routes with the country’s hinterland, helped drive the ‘Mexican Miracle’ and brought rapid and often dramatic social and economic change to many rural communities.118 They created new opportunities for loggers, farmers and merchants, while also facilitating the outmigration of former peasants in search of work and steady wages, first in the growing cities of central and northern Mexico, and, later, in the USA, creating a rural Mexican diaspora whose family ties linked together distant urban centres throughout both countries.119

The new roads also made it less difficult to travel between the poppy fields of Durango’s northern mountains and the state capital, and from there to the rest of north-central Mexico. Local drug traffickers were quick to take advantage of the opportunities provided by such infrastructural improvements,120 which by the mid 1940s had already reportedly spurred the evolution of new trafficking routes running from the mountains of Durango to ‘Parral, Chihuahua; and El Paso, Texas’.121 Given their inherently secretive nature, there is little concrete information on the further development of Durango’s trafficking routes before the Chicago police identified the existence of the state’s ‘heroin highway’ in 1974,122 except for a newspaper report from 1963 detailing the use of new roads to transport opium from Topia, Tamazula and Tepehuanes first to Durango city, from there to the trafficking hub of Gómez Palacio-Torreón, and then up through north-central Mexico to the US border at Ciudad Juárez. These revelations came after federal judicial police in Torreón found eleven and a half kilos of opium in a car that two men had driven down from a village in the mountains of Tepehuanes. The opium was worth 100,000 pesos raw, but had the potential to ‘yield products worth more than half a million pesos’ (then worth US$40,000) once refined into heroin and sold in the USA.123 One of the men confessed that ‘as a boy in Tepehuanes he had heard much talk about the cultivation of poppies’, and had bought the opium on behalf of two Americans he had encountered in Monterrey. But with each of them holding valid passports and more than 500 pesos in cash when arrested, the police surmised it was more likely they used north-central Mexico’s expanding road network to ‘smuggle drugs [directly] to the United States with some frequency and have used these documents to enter that country, in what appears to be an “open and shut case” ’.124

The new roads connecting rural parts of Durango to the state capital, and thence to the USA via Chihuahua, allowed Durango-born traffickers to establish their own independent, small-scale trafficking networks, which boosted their profits by cutting out the Sinaloan traffickers who controlled traditional Pacific Coast smuggling routes. Thus in Durango, as in other marginal regions of Mexico or, for that matter, in comparable parts of Bolivia, Peru, Colombia or Afghanistan, road-building projects that formed part of wider, Cold War development programmes facilitated the expansion and increasing sophistication of illicit as well as licit activities, which became progressively more interwoven as together they helped to drive forward nationwide processes of social, political and economic modernization.125

IV Arrieros, Braceros and ‘Narcos’: Durango’s drug trade enters the modern age

The final element in the development of the drug trade in Durango into a major state industry that combined rural production with transnational trafficking, was the departure of thousands of people from rural Durango to the USA in the immediate post-war period, which led to the emergence of a tight-knit Duranguense community in Chicago in the 1960s. Just as the presence of Cuban exiles in Florida facilitated the development of early trafficking routes through the Caribbean,126 and the establishment of a Colombian diaspora in New York later helped the Medellín Cartel take control of cocaine distribution there,127 some of Chicago’s Duranguense migrants had family ties to opium producers and traffickers back home, for whom they began to act as drug mules and local distributors. In so doing, they consolidated Durango’s importance as one of Mexico’s major centres of heroin production, while transforming Chicago into the most significant heroin-trafficking hub in all of North America.128

Duranguense immigration to the USA skyrocketed in the 1940s and 1950s, with the completion of the Durango to Juárez stretch of the Pan-American Highway, and the concurrent expansion of the Bracero migrant worker programme. The latter was a joint US–Mexican government initiative, officially launched in 1942, that aimed to resolve US labour shortages caused by the Second World War by inviting Mexicans to the USA to work as temporary agricultural workers.129 In public, the then-President Ávila Camacho had celebrated the scheme’s launch as a demonstration of his government’s commitment to the Allied war effort and to democracy.130 But Mexican policy makers were in reality more enthusiastic about the idea ‘that braceros would use their earnings and acquired knowledge to develop and modernize rural Mexico upon their return’.131 Despite generating virulent opposition on both the left and right, the Bracero programme proved wildly popular with rural Mexicans, and after the end of the Second World War it was extended for another two decades. When the programme was finally wrapped up in 1964, more than 4.6 million bracero contracts had been given out to at least 1 million individual Mexican workers, ‘making it the largest importation of foreign labour in US history’.132

Nearly half of these workers hailed from the four core Mexican states of Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán and Zacatecas, while another 20 per cent were natives of Chihuahua or Durango.133 Most came from either depressed former mining regions or overcrowded agricultural areas, particularly those where state-led agrarian reform had been minimal. Environmental factors also helped to drive migration, particularly the droughts that affected much of western and northern Mexico in the mid 1940s.134 In Durango, ‘entire villages showed up at the state capital hoping to join the [Bracero] program and go north to find work’ in the wake of the worst of these dry years.135 The unforeseen negative impacts of revolutionary-era agrarian reform, and subsequent modernizing policies enacted during the ‘Mexican Miracle’ — during which improved health-care provision and the technology-driven ‘Green Revolution’ led to ‘population explosion, erosion, and market dependence [and] forced rising numbers off the land’136 — spurred further waves of mass migration to the USA. These increasingly involved workers who had been unable to secure contracts as braceros, as well as women and children, who were officially excluded from the Bracero programme.137 Despite being unauthorized migrants, they were able to take advantage of the ‘transnational social and financial networks’ established by those who had already left as braceros to help them ‘find work and housing in the United States’.138

By the mid 1960s, many tens of thousands of migrants from Durango (including depressed former mining regions such as Tepehuanes),139 had travelled up the Pan-American Highway, crossed the US border at Juárez-El Paso (or, less often, at Eagle Pass or Laredo),140 and worked their way up through Texas and the south-eastern states as far as the agricultural Midwest, where they picked beets in the fields of Ohio and Nebraska,141 or cucumbers in Michigan (an activity in which Mexicans made up 75 per cent of the workforce by the mid 1950s).142 Many eventually settled in the Midwest’s largest city, Chicago, where they joined other Mexicans from across the country. Rather than mixing together as in other US cities, in Chicago the Mexican immigrants tended to settle together with others from the same state, or even municipality, with each group dominating a different Southside neighbourhood (with those from Tepehuanes, for example, favouring the suburb of Aurora).143 Fierce rivalries developed between them, increasing the internal solidarity that existed within each neighbourhood.144 At the same time, in line with the hopes of Mexico’s revolutionary ideologues that immigration to the USA would inspire ‘newfound skills, aspirations and behavioural traits’ amongst their countrymen,145 a handful of Durango-born Chicagoans recognized the opportunity presented by increasing local demand for heroin, which they began to secure from contacts back in Durango for distribution in their new home city.

At the helm of this new transnational enterprise was a former traffic policeman named Jaime Herrera Nevárez, who would reign as the ‘Tsar of heroin in Mexico’ from the early 1970s until the late 1980s.146 Herrera and his brothers, sons, cousins and the other relatives who formed the initial core of the Durango–Chicago trafficking network all hailed from the imaginatively named village of Los Herrera, in Santiago Papasquiaro: a large, oddly shaped municipality that lay half within Durango’s western mountains, half in the state’s central plains. While Carey implies that the links between the Herrera network and this one ‘small Mexican town’ have been exaggerated,147 their birthplace was central to their emergence as traffickers. Los Herrera was the eastern terminus of the ancient mule trails that linked Durango’s altiplano to the mining settlements of Tepehuanes and Topia to the west and the Sinaloan coast beyond them,148 while the early twentieth-century Durango–Tepehuanes railway,149 and the more recently completed road connecting Durango’s state capital to Tepehuanes, Canelas, Topia and Tamazula, also ran right through the town. Thanks to its position on these major thoroughfares from the mountains to the plains, and from there to the rest of Mexico’s centre-north, a good part of the people of Los Herrera had left along those same roads in search of new opportunities in the USA. While of the thousand or so who stayed behind, many were small-scale farmers and ranchers who also worked part-time as travelling merchants, or arrieros, selling lowland products in the mountains, and bringing back the ‘products of the Sierra [Madre]’ for sale in the nearby towns.150 By the mid 1950s, of course, the aforementioned ‘products’ included opium.151

Jaime Herrera Nevárez apparently became involved in this trade at some point in the late 1950s or early 1960s.152 Like many major players in the Mexican drug trade past and present, he started out as a state police officer,153 for whom precarious working conditions were a given and the need for ‘additional funds’ a constant, leading DEA sources to suspect that ‘most of these agents are involved with minor narcotic traffickers’.154 Having grown up in Los Herrera, to which he maintained close links throughout his life,155 Herrera Nevárez would have known all about the booming opium industry in neighbouring Tepehuanes, and might well have known some of the local growers, buyers and traffickers himself.156 During the mid to late 1960s, when he was stationed on the Durango City–Gómez Palacio highway as an officer of Durango’s State Judicial Police, he would likely have had further contact with the drug trade via occasional run-ins with traffickers using this route to move heroin between Durango and the USA.157 And given that his brother Reyes, and other close family had settled in Chicago, he must also have been conscious of where much of this heroin eventually ended up, and of the increasing amounts of money to be made through its distribution,158 as from the early 1960s in Chicago, Detroit and other major US cities, ‘young African Americans and Latinos — and, from the end of the decade, young whites — began to use heroin in larger numbers, creating a new wave of heroin use that dwarfed the one that had followed World War II’.159

By the late 1960s, Jaime Herrera Nevárez had combined the power and status that came with his position as a representative of the Mexican state, with his personal connections with three very different worlds — that of drug production in Durango’s mountains; the police forces that regulated regional trafficking; and the Mexican migrant communities of Chicago — to become a major heroin trafficker. By then, he had also risen to command of the Second Section of Durango’s Judicial Police,160 and, like many of Mexico’s other top narco-entrepreneurs, soon earned the badge of a DFS agent, too, all of which provided him with further high-level political connections, protection and the ability to selectively enforce anti-drug laws to his own advantage.161 At the same time as it depended on constituent elements of Mexican modernity such as transnational highway networks, mass migration, political patronage and an increasingly well-organized (and deeply corrupt) law enforcement apparatus, the trafficking network Herrera Nevárez ran with his brothers and other relatives also remained deeply rooted in structures and practices long prevalent in the mountains of northern Durango. The raw opium on which it ultimately depended was purchased from growers in Tamazula, Topia and Tepehuanes by arrieros connected by blood, marriage or geography to the Herrera family, who left their produce for collection in a designated spot in the mountains in what was effectively a more secretive version of traditional trade arrangements between highland peasants and lowland merchants.162

For every ten kilos of opium bought down from the mountains, one kilo of crude but potent ‘black tar’ heroin could be produced,163 initially in laboratories still run by Sinaloan traffickers and chemists.164 In the Mexican heroin trade, as in the Andean cocaine business, these drug-processing labs were vital links in the chain connecting peasant growers to US drug consumers,165 and their dominance in this area enabled the Sinaloans to maintain an outsized influence over Durango’s opium industry. However, in the three years following the 1972 dismantling of the ‘French Connection’ linking Turkish opium producers to US dealers, ‘Mexican heroin increased from 40 to 90 per cent of the US market’.166 This high-level shift drove important changes on the ground across Mexico: it prompted the expansion of poppy cultivation (and state eradication campaigns) south into the states of Jalisco, Michoacán and Guerrero,167 while traffickers’ surging profits allowed them to set up their own opium-processing facilities. The Herreras established new laboratories in Durango city, Los Herrera, and Tepehuanes, cutting out the last Sinaloan middlemen from Durango’s drug trade.168 The heroin they produced was then hidden in cars — either packed into specially partitioned petrol tanks, or metal sleeves surrounding the drive shaft (which became known as a ‘Durango drive shaft’) — and driven by mules up the Pan-American Highway from Durango to Chicago (see Map 3), a fifty-hour journey along a route by now familiar to two generations of local immigrants.

All along this ‘heroin highway’, Herrera operatives — including corrupt officials in both Mexico and the USA — helped make sure that the journey went smoothly.169 The Herreras also took advantage of US stereotypes to get their produce safely across the border. A DEA agent stationed at El Paso noted that Customs officers ‘stop the wrong people . . . It’s longhairs. It’s blacks. It’s Americans. But you sit at the border for a couple of hours and watch . . . [customs agents] wave through the clean-looking Mexican families in well-maintained cars with kids in the back seat. That’s your heroin coming through right under everyone’s nose’. The Herreras’s intelligence service was also effective and responded quickly to the emergence of new threats to their operation: ‘When Mexican authorities started a road-block campaign [in 1974], for instance, Durango traffickers switched within hours to aircraft instead of cars and trucks’. Thus the US Customs service themselves estimated they were ‘only able to interdict some two percent of the heroin crossing the Southwest border’.170

By the mid 1970s, Chicago had ‘usurped New York’s role as the national distributor of heroin’,171 of which US law enforcement estimated that between one-third and one-half was supplied by the Herreras.172 But unlike the centralized, top-down organization that the DEA and its media allies presented to the public,173 the Herrera network constituted a much looser association of merchants, smugglers and ‘protectors’: one that, from a core of individuals from one small corner of Durango connected by long-standing social, political and economic practices, expanded in the USA to include a range of ‘Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and European Americans, men and women alike’.174 The Herreras and their affiliates sold their heroin wholesale to buyers ranging from Mexican- and Afro-American street gangs in Chicago, to Puerto Rican mafia groups in New York, and other criminal groups further afield in Denver, Detroit, Dallas, Oklahoma City and Los Angeles.175

US law enforcement agencies estimated that the Herrera organization made around US$21,000 profit per kilo of heroin, and that their total annual turnover ‘would place the Herrera group about 116th in the Fortune magazine listing of America’s most profitable corporations, and ninth, just behind Safeway Stores, in profit earned by U.S. retailers’.176 More than 75 per cent of this money was sent back to Durango via neighbourhood money exchanges,177 which continued to drive the development of its mountain regions. Thanks to the ‘cultivation and production of illegal drugs’, remote former mining towns like Topia enjoyed a newfound ‘economic affluence’, their shops stocking ‘a wide assortment of US and Mexican products’ to sell to local peasants flush with drug money.178 Even a small (quarter-hectare) field of poppies could, by the late 1970s, produce opium worth US$3,000 every year, ‘about five times the average annual wage’.179 The DEA claimed that such profits directly supported some 7,460 farm labourers in Durango in the same period, providing a ‘tremendous, if illicit, boon to the Mexican economy’.180

Even treating the DEA’s often-inflated figures with a healthy scepticism, it is clear that the Herreras — who became one of Durango’s most important families — earned tens of millions of dollars a year from the heroin trade, which they reinvested in ‘land, ranches, dairies, apartments, resort developments, and financial institutions’ throughout the state and beyond into the rest of Mexico,181 and which transformed the village of Los Herrera into a ‘town of wealthy people, [who] gave work to the men of the other communities of Santiago [Papasquiaro], [and] provisioned the town’s boutiques with clothes from Fifth Avenue’.182 By the late 1970s, the effects of crisis, corruption and the quest to bring ‘modernity’ to rural Mexico had made opium production and heroin trafficking among the biggest businesses in Durango, and ones so deeply intertwined with the licit regional economy and political system that they remained largely invulnerable to both US and Mexican government attack.

V Conclusions

In August 1987, Jaime Herrera Nevárez was arrested in Durango and extradited to the USA, where he received a life sentence.183 But his downfall had little more effect on Durango’s drug trade than that of earlier traffickers such as Aureliano de la Rocha. Nor has the active and continued involvement of US officials in anti-drugs crackdowns in the state — from the eradication expeditions of the 1940s to the heavily militarized ‘Operation Cóndor’ in the 1970s — done much to curb opium production and heroin trafficking in places like Tamazula and Topia, which in 2021 were home to, respectively, the second and ninth greatest areas of poppy cultivation of all Mexico’s 2,454 municipalities.184 Instead, the insatiable appetites of US citizens, the increasing integration of global markets, and the resilience of corruption, caciquismo and rural poverty in Mexico despite its social, economic and political modernization, continue to drive a booming drug trade in Durango: a trade that depends on family-based enterprises that concurrently span regional and national borders, working together to return profits that would make a megacorporation proud, on the back of an ‘artisanal’ product created by a few thousand hardscrabble peasants and rural merchants in a peripheral corner of a poor Mexican state.

Contrary to the worries of nineteenth-century Mexican elites that drug use and trafficking by their compatriots would ‘symbolically disqualify [Mexico] from the club of civilised modernity’,185 the rise of the drug trade in places like Durango was from its very beginnings an integral part of local modernizing processes. The state’s peasants did not turn to opium production to gain access to a ‘modern world’ they were entirely closed off from; it was instead their prior involvement in a mining industry ravaged by national political turmoil and global economic shock that pushed them to diversify the products they offered to an already transnational market, and in so doing further harness the benefits of ‘modernity’ in the form of new consumer goods and improved agricultural technologies. As Mexico’s modern political system subsequently took shape, Durango’s burgeoning drug trade was buoyed by the participation of an expanding range of state officials, from the members of the de la Rocha clan who promoted and protected highland opium production in the 1940s, to police officers like Jaime Herrera who, in the 1960s, transformed lowland heroin smuggling networks into international distribution organizations. Such government–trafficker pacts were compounded by the official promotion of infrastructural development and mass migration, which provided new and more efficient ways of getting illicit commodities from Mexico to the USA. In so doing they helped consolidate the political, social and economic modernization of parts of Durango that would otherwise have been left behind by the licit side of the ‘Mexican Miracle’.

In this sense, then, the growing importance of opium production and heroin trafficking in Durango between 1920 and 1980 was not the result of a ‘failure’ of state development of the type that had sparked drug booms in many other Latin American nations in the 1960s and 1970s. Instead, the case of Durango more closely resembles that of Myanmar in the 1990s, where ‘for many households the decision to cultivate opium has been a response to the very processes of market-led rural development that policymakers claim will alleviate poverty’.186 After all, the construction of Durango’s ‘heroin highway’ was a reaction to precisely the sort of market forces that the US model of capitalist development, promoted so strenuously in Latin America over the last century, demands that any ‘rational’ economic actor should — indeed, must — exploit for profit.187 The transformations on both the Mexican and US sides of the border that facilitated the birth, expansion and consolidation of a Durango–Chicago heroin connection and the US–Mexican heroin trade as we know it today — which included industrial crises and entrepreneurial booms, international economic integration and rural capitalist development, political stabilization and mass migration — together constitute a transnational capitalist success story, and one that was built on the combined efforts, hopes and desires of the kinds of people that US and Mexican policy makers would have us believe we should all be: from the peasants in the mountains of Durango chasing the ‘Mexican Miracle’, to the illicit entrepreneurs in Chicago trying to live the American dream.

Footnotes

I owe a great debt of thanks to Wil Pansters and Benjamin Smith for including me in their AHRC-funded project on the history of the Mexican drug trade (AHRC,Narco-Mex Project 2016–17), which gave me the opportunity to begin the research presented in this article. I am also deeply grateful to the Leverhulme Trust for awarding me an Early Career Fellowship (Leverhulme Trust, ECF-2018-466), which gave me the time and space to start writing up this research, and to UCL’s History Department, where as a member of staff I was able to finish it. I owe further thanks to Benjamin Smith and Thomas Rath for their supremely instructive comments on various versions of this paper; and to my colleagues at the IHR Latin American History seminar, whose feedback helped me to fine-tune the revisions to this article. Finally, muchas gracias to Antonio Reyes Valdez and Bridget Zavala Moynahan for hosting me in Durango on multiple occasions, and to Alan Knight for his generous and untiring mentorship over many, many years. Funding is provided by Leverhulme Trust, ECF-2018-466 AHRC, Narco-Mex Project 2016-17.

‘Plantío de Adormidera’, El Siglo de Torreón, 13 June 1944.

If sold wholesale in the USA (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, ‘World Drug Report’, 2021).

US National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (hereafter NARA), RG170, Box 22: Salvador Peña to US Customs Commissioner, 16 May 1944.

This was also discovered in Durango in 2020, but measured only five hectares — Omar Hernández, ‘Destruyen plantío de amapola en Durango’, Imágen Radio, 26 Feb. 2020, <https://www.imagenradio.com.mx/destruyen-plantio-de-amapola-en-durango> (accessed 10 Oct. 2023).

Janice Hopkins Tanne, ‘Life Expectancy: US Sees Steepest Decline in a Century’, BMJ (Online), ccclxxviii, o2142 (5 Sept. 2022).

Cecilia Farfán-Méndez, Romain Le Cour Grandmaison and Nathaniel Morris, ‘Why the Drug War Endures: Local and Transnational Linkages in the North and Central America Drug Trades’, Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, iv (2022), 103.

Isaac Campos, Home Grown: Marijuana and the Origins of Mexico’s War on Drugs (Chapel Hill, 2012); Diego Enrique Osorno, El cártel de Sinaloa: Una historia del uso político del narco (Mexico City, 2009); Wil G. Pansters, Benjamin T. Smith and Peter Watt (eds.), Beyond the Drug War in Mexico: Human Rights, the Public Sphere and Justice (Abingdon, 2018); Wil G. Pansters and Benjamin T. Smith (eds.), Histories of Drug Trafficking in Twentieth-Century Mexico (Santa Fe, 2022).

A classic example is Alfred W. McCoy, The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (New York, 1972); amongst the best recent studies is James Bradford, Poppies, Politics, and Power: Afghanistan and the Global History of Drugs and Diplomacy (Ithaca, NY, 2019).

Benjamin T. Smith, ‘The Rise and Fall of Narcopopulism: Drugs, Politics, and Society in Sinaloa, 1930–1980’, Journal for the Study of Radicalism, vii (2013); Benjamin T. Smith, The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade (London, 2021); and, Benjamin T. Smith and Juan Fernández Velázquez, ‘A History of Opium Commodity Chains in Mexico, 1900–1950’, Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, iv (2022); Luis Astorga, Drogas sin fronteras (Mexico City, 2003).

Peter A. Lupsha and Kip Schlegel, ‘The Political Economy of Drug Trafficking: The Herrera Organization (Mexico and the United States)’, (University of New Mexico, Latin American Institute Working Paper no. 2) (Albuquerque, 1980); Elaine Carey, ‘The Mexico–Chicago Heroin Connection’, in David Farber (ed.), The War on Drugs: A History (New York, 2021); Nathaniel Morris, ‘Heroin, the Herreras, and the “Chicago Connection” ’, in Pansters and Smith (eds.), Histories of Drug Trafficking in Twentieth-Century Mexico.

In Mexico, these include the Casas de Cultura Jurídica of Durango (hereafter CCJD), Mazatlán (hereafter CCJS), Tijuana, and Ciudad Juárez (hereafter CCJCJ); the National General Archive (hereafter AGN) and Health Ministry Archive (hereafter AHSS) in Mexico City; in the USA, the NARA in Washington, DC, and the private archive of an anonymous former DEA agent.

Particularly the Siglo de Torreón, the Chicago Sun-Times, and Jorge Hayashi Jiménez, Benjamín Luna Lujano and Gabriela Moreno Nevárez, El legendario Tino Nevárez, un tigre de la montaña (Culiacán, 2015).

For a recent overview of this fascinating, fast-expanding, interdisciplinary field, see Jonathan Goodhand et al., ‘Drugs, Conflict and Development’, in the homonymous special issue of the International Journal of Drug Policy, lxxxix (2021), 1–3. More detailed case studies that have informed my analysis here include: Astorga, Drogas sin fronteras; Paul Gootenberg and Liliana Dávalos (eds.), The Origins of Cocaine: Colonization and Failed Development in the Amazon Andes (London, 2018); Thomas Grisaffi, Coca Yes, Cocaine No: How Bolivia’s Coca Growers Reshaped Democracy (Durham, NC, 2018); and Bradford, Poppies, Politics, and Power.

My debts to the work of Alan Knight, Luis Aboites, Wil Pansters, Thomas Rath and Benjamin Smith on this subject are many and obvious.

Paul Gootenberg, ‘Orphans of Development: The Unanticipated Rise of Illicit Coca in the Amazon Andes, 1950–1990’, in Gootenberg and Dávalos (eds.), Origins of Cocaine, 1.

Lina Britto, Marijuana Boom: The Rise and Fall of Colombia’s First Drug Paradise (Stanford, 2020), 2.

Bradford, Poppies, Politics, and Power.

Alan Knight, ‘The Myth of the Mexican Revolution’, Past and Present, no. 209 (Nov. 2010), 260–3.

Nicola Miller, Reinventing Modernity in Latin America: Intellectuals Imagine the Future, 1900–1930 (London, 2008), 1–2.

Arturo Escobar, Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World (1994; Princeton, 2012), 4.

Thomas Rath, ‘Burning the Archive, Building the State? Politics, Paper, and US Power in Postwar Mexico’, Journal of Contemporary History, lv (2020), 769.

Timo Schaefer, ‘Growing up Indio during the Mexican Miracle: Childhood, Race and the Politics of Memory’, Journal of Latin American Studies, liv (2022), 182.

Paul Gillingham and Benjamin T. Smith (eds.), Dictablanda: Politics, Work, and Culture in Mexico, 1938–1968 (Durham, NC, 2014), 11–12 (editors’ intro).

For example, Howard F. Cline, Mexico: Revolution to Evolution, 1940–1960 (Oxford, 1962).

Ryan Alexander, ‘Myth and Reality of the Mexican Miracle, 1946–1982’, in William Beezley (ed.), Oxford Handbook of Mexican History (Oxford, 2020).

Gillingham and Smith (eds.), Dictablanda, 11–12.

Maritza Paredes and Hernán Manrique, ‘Ideas of Modernization and Territorial Transformation: The Case of the Upper Huallaga Valley of Peru’, and Jennifer S. Holmes, Viveca Pavón, Sheila Amin Gutiérrez de Piñeres, ‘Economic Development Policies in Colombia (1960s–1990s) and the Turn to Coca in the Andes Amazon’, both in Gootenberg and Dávalos (eds.), Origins of Cocaine; Britto, Marijuana Boom, 9; Victoria Malkin, ‘Narcotrafficking, Migration, and Modernity in Rural Mexico’, Latin American Perspectives, xxviii (2001), 101; James H. McDonald, ‘The Narcoeconomy and Small-Town, Rural Mexico’, Human Organization, lxiv (2005), 115–25.

Michael Snodgrass, ‘The Bracero Program, 1942–1964’, in Mark Overmyer-Velásquez (ed.), Beyond la Frontera: The History of Mexican–U.S. Migration (Oxford, 2011), 80; see also Alberto García, ‘Regulating Bracero Migration: How National, Regional, and Local Political Considerations Shaped the Bracero Program’, Hispanic American Historical Review, ci (2021), 433.

Malkin, ‘Narcotrafficking, Migration, and Modernity in Rural Mexico’, 102; McDonald, ‘Narcoeconomy and Small-Town, Rural Mexico’, 120.

Anon., ‘Jaime Herrera y otros prominentes empresarios de Durango, involucrados’, Siglo de Torreón, 30 June 1985.

See Patrick Meehan, ‘Precarity, Poverty and Poppy: Encountering Development in the Uplands of Shan State, Myanmar’, International Journal of Drug Policy, lxxxix (2021).

Paul Gootenberg, ‘Chicken or Eggs?: Rethinking Illicit Drugs and “Development” ’, International Journal of Drug Policy, lxxxix (2021).

See, for example, Escobar, Encountering Development; Sara Lorenzini, Global Development: A Cold War History (Princeton, 2019); and the essays in Stephen J. Macekura and Erez Manela (eds.), The Development Century: A Global History (Cambridge, 2018).

Charles Bowden, Down by the River: Drugs, Money, Murder, and Family (New York, 2002), 169.

Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines (2016–22), Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil (2019–22) and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador (2019 to the present), all harnessed this idea to election-winning effect.

For Mexico specifically, see Pablo Piccato, A History of Infamy: Crime, Truth, and Justice in Mexico (Oakland, 2017), 263–4; for a classic analysis centred on Europe, see Charles Tilly, ‘War Making and State Making as Organized Crime’, in Peter B. Evans, Dietrich Rueschmeyer and Theda Skocpol, Bringing the State Back In (Cambridge, 1985).

See McDonald, ‘Narcoeconomy and Small-Town, Rural Mexico’, 117.

National Institute of Statistics and Geography, Aguascalientes, Mexico (hereafter INEGI), ‘México en Cifras’, 2020, at <https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas>; for context, this is four times lower than Mexico’s average, and twenty times lower than England’s.

Luis Aboites Aguilar, ‘La decadencia de Durango durante el siglo XX: una mirada a la historia del norte mexicano’, Chihuahua Hoy, xvi (2018), 190.

Ibid., 193.

Antonio Avitia Hernández, El caudillo sagrado: historia de las rebeliones cristeras en el estado de Durango (México, 2006), 87–8; Aboites Aguilar, ‘La decadencia de Durango’, 192.

Nathaniel Morris, Soldiers, Saints, and Shamans: Indigenous Communities and the Revolutionary State in Mexico’s Gran Nayar (Tucson, 2020).

Avitia Hernández, El caudillo sagrado, 256.

Jean Meyer, La cristiada, 3 vols. (Mexico, 1973), i, 222.

Johnathan Walker and Jonathan Leib, ‘Revisiting the Topia Road: Walking in the Footsteps of West and Parsons’, Geographical Review, xcii (2002), 572.

Hayashi Jiménez, Luna Lujano and Moreno Nevárez, El legendario Tino Nevárez, un tigre de la montaña, 31.

Campos, Home Grown, 199–200.

AHSS, SP/SJ/c/28/e/6: Requena to Departamento de Salubridad Pública, 21 July 1931.

‘Chinos Siguen Comerciando Drogas Nocivas’, Siglo de Torreón, 16 Apr. 1925.

Smith, ‘Rise and Fall of Narcopopulism’, 132–5.

Juan Antonio Fernández Velázquez, ‘El narcotráfico en los Altos de Sinaloa, 1940–1970’ (Univ. of Veracruzana Ph.D. thesis, 2020), 31.

Marcos Vizcarra Ruiz, ‘The Pendulum of Scarcity: Opium, Farmers and Internal Migration in the Golden Triangle’, Noria Research, 7 Mar. 2021, available at <https://noria-research.com/chapter_5_the_pendulum_of_scarcity/> (accessed 10 Oct. 2023).

Hayashi Jiménez, Luna Lujano and Moreno Nevárez, El legendario Tino Nevárez, un tigre de la montaña, 58.

For more details on these routes, see Walker and Leib, ‘Revisiting the Topia Road’, 576.

Ibid., 572, 578.

NARA/MIDRF/Box 2553: Asst. Mil. Attaché Capt. HL Wightman, Report on Mexican Opium Trade, 20 Apr. 1944.

Ibid.

CCJCJ, Penales/1945/E/53: Abraham Delgado.

Smith, ‘Rise and Fall of Narcopopulism’, 133–4.

Fernández Velázquez and Smith, ‘History of Opium Commodity Chains in Mexico’, 17–18.

See, for example, CCJBCN/Penales/1945/C/1/E/16: Manuel Salinas Ortiz; CCJBCN/Penales/1948/C/2/E/36: Narciso Chávez García; CCJCJ/Penales/1937/E/2224: Ignacia Jasso; CCJCJ/Penales/1929/E/1020: Pablo González; CCJCJ/Penales/1938/ID/2364/E/1: Gregorio Pérez; and CCJCJ/Penales/1944/ID/3358/E/13: Juana Alvarado.

Alan Knight, ‘The Weight of the State in Modern Mexico’, in James Dunkerley (ed.), Studies in the Formation of the Nation State in Latin America (London, 2002), 212–53; see also the essays in Gillingham and Smith (eds.), Dictablanda.