-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Matteo Boldrini, Candidates nomination strategy in a mixed electoral system: Evidence from the 2022 Italian general election, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 78, Issue 2, April 2025, Pages 401–424, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsae030

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Despite the significant attention that scientific literature has dedicated to candidate selection mechanisms, relatively few studies have delved into which characteristics influence candidate positioning on the list. Social scientists have primarily focussed on factors shaping a candidate’s career rather than those affecting their placement on the list. Placement is a crucial factor in mixed or proportionally representative electoral systems with closed-list structures. Through a multivariate statistical analysis applied to an original dataset on candidates from major parties, this article aims to fill this gap in the literature by analysing candidates in the list during the 2022 Italian political elections. The results suggest that factors such as incumbency, previous national career, and the level of local rootedness favour placement on the list in positions where the chance of election seems more realistic. Conversely, gender favours placement in positions where the chances of election are less realistic. Additionally, dual candidacy in both the proportional and majoritarian parts also appear to have a positive effect; however, its interaction effects with other variables are less clear.

1. Introduction

The selection of candidates has long been a favoured subject of analysis for social scientists. Scholars have extensively explored candidate selection, its rules, and mechanisms (Gallagher and Marsh 1988; Best and Cotta 2000; Rahat and Hazan 2001; Shomer 2014), along with the characteristics that favour the selection of certain candidates (Put et al., 2015; Vandeleene et al., 2016; Berz and Jankowski, 2022; Rehmert, 2022). However, how these factors influence candidates’ positioning on the electoral list, and consequently their visibility and probability of election, has often been overlooked by social scientists.

Only in recent years has scientific literature started to investigate which factors affect candidates’ placement on the electoral list, predominantly examining this in reference to open-list proportional representation systems (Däubler, Christensen and Linek 2018; Put et al. 2021a, 2021b; Dvořák and Pink 2023; Passarelli 2023), where—paradoxically—the influence of the order on the list is less pronounced. In fact, less frequent are studies on proportional representation systems with a closed list (Gherghina and Chiru 2010) and on mixed majoritarian and proportional systems (Ceyhan 2018). Mixed-member systems constitute a particularly interesting case to investigate, as, due to their dual nature, they allow for an examination of whether there is a contamination effect (Herron and Nishikawa 2001) from one arena to another.

In this perspective, due to its political and institutional features, Italy represents a crucial case study (Eckstein 1975). After the electoral reform of 2017, a mixed proportional and majoritarian electoral law is in force, allocating approximately 36% of seats in single-member districts (SMDs) and the remaining 64% in multi-member districts (MMDs).

Through an original dataset on candidates from the Italian elections of 2022, this article aims to contribute to studies on factors that facilitate candidates’ inclusion in positions on the list where the chances of election are higher, with a perspective that highlights the influence of the dual electoral arena in this process. More specifically, the research question investigates which socio-biographical and political characteristics favour candidacy in positions where the chances of election are higher and how their influence changes in interaction with candidacy in the two different electoral arenas.

Through a multivariate analysis performed using linear regression with OLS, the analysis highlights those factors such as incumbency, a longer national career, or stronger territorial roots favour inclusion in positions on the list where the chances of election are more realistic. On the contrary, gender is a feature that negatively affects list positioning. Furthermore, regarding the influence of candidacy in the dual arena, the results are more puzzling. The research highlights a positive influence of dual candidacy regarding the position on the list; however, this does not apply to its interaction with other characteristics, which seem to remain the determining variables in defining who will be nominated in positions where the chances of election are more realistic.

The article is structured as follows. The first section illustrates the results of previous research on party list nominations in proportional and mixed electoral systems. The second section briefly summarizes the features of the Italian electoral law and explains why it is an interesting case to explore. The third section illustrates the research hypothesis. The fourth section presents the method, the selection of variables, and their operationalization. The fifth section illustrates the multivariate analysis with the respective data interpretation. Finally, the conclusions follow.

2. Party list ranking in proportional system

Social scientists have strongly focussed on the process of choosing candidates. However, as noted in the literature (Put et al., 2021b; Vandeleene 2023), research on selection processes has primarily concentrated on the methods used by parties to select candidates (e.g. Gallagher and Marsh 1988; Rahat and Hazan 2001; Hazan and Rahat 2010; Shomer 2014; Vandeleene and van Haute 2021) rather than on the criteria favouring their placement on the list. Only recently has the literature started to analyse why certain candidates are chosen (Vandeleene 2023), how these processes can facilitate or hinder access to representation by specific social groups (Dvořák and Pink 2023), and how certain candidate features can favour placement in higher positions on the list (Gherghina and Chiru 2010; Put and Maddens 2013; André et al. 2017; Ceyhan 2018; Put et al. 2021a, 2021b).

The subject holds central importance from various perspectives. If the process of choosing candidates still truly represents the ‘secret garden of politics’ (Gallagher and Marsh 1988), understanding the logic of list placement allows a deep exploration of the recruitment strategies of the parliamentary class before the electoral outcome. Elections, in fact, represent a filtering moment in which the members of the parliamentary class are defined and selected from the broader pool of candidates. Thus, understanding the strategies of list placement—especially in closed-list proportional systems where parties determine who has the highest chance of being elected—allows a better understanding of how parties facilitate (or do not facilitate) access to representation. Furthermore, candidacies represent one of the fundamental elements with which parties seek to maximize their popularity (and therefore their seats). Therefore, examining which factors favour or hinder the placement of candidates on the list allows for an exploration of the parties’ strategies in garnering electoral support.

Based on the classification proposed by Duverger (1951), which distinguishes between realistic positions (the most desirable, as they offer higher chances of being elected), non-realistic positions, and marginal positions, the scientific literature has investigated the factors influencing parties’ decisions to place certain individuals in realistic or less realistic positions. The literature has focussed on exploring the effects of list positioning within open-list proportional systems such as Belgium (Put et al. 2021a, 2021b), Sweden (Däubler, Christensen and Linek 2018), and the Czech Republic (Dvořák and Pink, 2023). However, the literature has not thoroughly explored this topic, especially in relation to closed proportional and mixed systems, analysed only in relation to Romania (Gherghina and Chiru 2010) and Germany (Ceyhan 2018). This constitutes a limitation, as in closed-list systems, positioning decisively influences a candidate’s chances of election.

In fact, unlike open proportional systems where the chances of election are guaranteed by the ability to obtain preference votes—although with some important variations related to the specifics of the electoral law (Passarelli 2020, 2023)—in closed systems, the chances of election are entirely determined by the position on the list. This aspect is particularly interesting in relation to mixed systems. As the literature has highlighted, mixed systems can indeed be characterized by the so-called ‘contamination effect’ (Herron and Nishikawa 2001; Cox and Schoppa 2002; Ferrara, Herron and Nishikawa 2005), where competition in both arenas (majoritarian and proportional) influences each other.

This connection has, however, been studied primarily at the level of voting behaviour, highlighting how the connection between the two arenas can influence the electorate and thus the results obtained by the parties. However, as part of the literature has pointed out, the connection between the two arenas can create incentives for strategic behaviour not only for voters at the time of voting but also for parties and candidates during list composition, creating a unique electoral incentive that can favour some candidates over others (Ceyhan 2018). This aspect, however, remains largely understudied in the literature. The limited presence of studies on different cases that include mixed electoral systems constitutes a significant limitation for three main reasons.

First, further studies on other country cases allow for a greater understanding of how the interaction between the two arenas influences the candidacy process. Additionally, there is strong variability in the functioning of mixed systems (Chiaramonte 2005), so comparing different cases (with different electoral systems) allows for exploration of how certain variables differently influence list placement. Furthermore, it highlights how national specificities—related to structural or conjunctural dynamics of the country—influence the candidacy process.

Lastly, the division into realistic and non-realistic positions—although a useful simplification—may not always be entirely satisfactory. Positions, as in Duverger’s original representation, are not divided into realistic or non-realistic but rather by different levels of electability, making an ordinal operationalization representation more useful.

3. Mixed electoral law in the Italian case

Italy—among the major European countries—is known for the frequent changes in its electoral law (Passarelli 2018) and for experimenting with mixed majoritarian and proportional electoral models. In the last thirty years, there have been four major electoral reforms (Chiaramonte 2015), introducing two mixed proportional–majoritarian systems and two mixed proportional systems with a majority bonus (Chiaramonte and D’Alimonte 2018).

The first system—the so-called Mattarella Law—was introduced in 1993 in the wake of the political change following the Tangentopoli scandal and replaced the previous proportional system with a mixed electoral law composed of 75% SMDs and 25% MMDs (D’Alimonte and Chiaramonte, 1995; Katz 2001).

The second reform took place in 2005 and reintroduced a mixed system—the so-called Calderoli Law—this time proportional with a majority bonus for the leading party or coalition (Di Virgilio 2007).

A third mixed electoral law was then introduced in 2015. Like the previous law, it consisted of a predominantly proportional system with a majority bonus of 54% of the seats for the party or coalition that obtained at least 40% of the votes. In the absence of this, a run-off would be held, where the winner would receive the majority bonus (Chiaramonte and D’Alimonte 2018).

Lastly, in 2017, the Italian legislature modified the electoral law, introducing a new mixed proportional and majoritarian system (Chiaramonte 2020). The new law, known as the ‘Rosato law’ after its proposer, allocates approximately 35% of seats (232 in the Chamber of Deputies and 116 in the Senate) in SMDs with a plurality system, whereas the remaining 65% is allocated in MMDs that include 2 to 4 candidates without the possibility of preference votes (Pinto, Pedrazzani and Baldini 2018). Each candidate can run in one SMD and up to five MMDs. However, the two arenas are not separate but closely linked. First, candidates in SMDs cannot run alone, as independents, but must be affiliated with a party list in the proportional part. The electoral system also includes a fused vote, where voters are given a single ballot and can cast only one vote, so they cannot vote separately (e.g. for a candidate and for a list that does not support him or her in the proportional part) in the two different arenas (Chiaramonte and D’Alimonte 2018). Thus, voters have three different voting choices: for a party list in the MMDs (in which case the vote is automatically transferred to the supported candidate in the SMDs), for a candidate in the SMDs (in which case the vote is transferred to the lists supporting them in the MMDs on a pro-rata basis based on the votes obtained in the same MMD), or, finally, for a candidate in the SMDs and for one of the lists supporting them in the MMDs. The presence of the fused vote favours the existence of the so-called ‘contamination effect’, through which the two different arenas influence each other in defining the voters’ preferences (Chiaramonte 2005; Ferrara, Herron and Nishikawa 2005).

Furthermore, the new electoral law introduces strong regulatory provisions aimed at promoting gender parity. In the SMDs, parties or coalitions cannot field more than 60% of candidates of one gender compared to the other, while in the MMDs, all candidates must be inserted in alternating gender order, and the first position on the list cannot be assigned to candidates of the same gender for more than 60% (Pansardi and Pedrazzani 2023). The Italian case, in addition to providing valuable information on how the process of candidate nomination works, is also interesting precisely because of the introduction of this regulation. Thus, for these reasons, Italy offers unique opportunities to observe and analyse a phenomenon (Yin, 2018) and can be considered a crucial case (Eckstein 1975), allowing us to precisely identify how the characteristics of the candidates and their interaction with the mixed electoral system influence their position on the list.

4. Research hypothesis

As regards the factors that can influence a candidate’s positioning on the list, the literature has explored the effects of different features.

From a theoretical point of view, one of the main factors that can favour placement on the list is being an outgoing MP. Firstly, being an incumbent can provide a significant advantage during elections. Incumbents can rely on the great visibility, resources, and relationships that their MP status provides them. The existence of an electoral advantage for incumbents has been studied particularly in relation to single-member district systems (Norris and Lovenduski 1995), but also in relation to proportional systems with open lists (André et al. 2017; Put et al., 2021a; Söderlund and von Schoultz, 2024). By positioning them at the top of the list where they are most visible to voters, parties believe they can increase their percentage of support (Ceyhan, 2018).

A second aspect is linked to the paths of elite reproduction. The theme of the self-reproduction of existing political elites is a tendency extensively examined by the classics of social sciences (Michels 1912; Pareto 1916). According to the classical authors, existing political elites generally tend to reproduce themselves, limiting the chances of election for outsiders. Contemporary research on the European political class has generally confirmed this tendency towards persistence. Although some research has highlighted cases of successful outsiders (Verzichelli 2010), the literature has underscored that—under normal conditions—there is a general propensity for the persistence of political elites (Matland and Studlar, 2004; Cotta and Best 2007; Verzichelli 2018). Incumbent candidates, leveraging their position and resources, can limit the entry of external candidates, exerting pressure on parties and securing the best positions on the list. Empirically, a strong effect of incumbency on list position has been observed in numerous studies (André et al. 2017; Ceyhan 2018; Meserve, Pemstein and Bernhard 2020; Put et al. 2021a, 2021b; Dvořák and Pink 2023; Passarelli 2023). Specifically, some authors have highlighted how certain factors destabilizing the political system (such as high volatility) can positively impact the closure of elites. Fearing non-reelection due to the political context, these elites tend to negotiate better positions on the list (Muyters and Maddens 2023).

It can therefore be hypothesized that, both due to this greater endowment of resources and due to needs linked to the reproduction of the existing parliamentary class, incumbent candidates have a greater possibility of being positioned in list places where the probability of election is more realistic. Based on this, the first hypothesis of the research can be formulated:

H1: Incumbent candidates have a higher chance of being placed in positions where election is more realistic.

Another characteristic linked to more favourable list placement is institutional experience. As highlighted in the literature (Vandeleene 2023), the search for competent candidates, experts in politics, and knowledgeable about institutional dynamics constitutes one of the prevalent criteria by which parties select candidates.

Election campaigns are often complex and lengthy, requiring time to understand their functioning. It is natural for parties to seek to promote candidates with more experience in this regard. Understanding the functioning of institutions, specific political dynamics, and the mechanism of parliamentary activity necessarily requires time (Best and Cotta 2000), so it is natural that more experienced politicians can be an important resource for parties, both in terms of knowledge and competence of institutional mechanisms and as credibility in front of voters. Therefore, a long institutional career would be a factor favouring placement in positions on the list where it is easier to be elected (Gherghina and Chiru 2010; Chiru and Popescu 2017; Ceyhan 2018; Meserve et al., 2020). Thus, it can be hypothesized that candidates with longer institutional experience at the national level have a greater probability of being placed in positions with a higher likelihood of election.

H2: Candidates with longer institutional career in national institutions have greater chance of being placed in positions where election is more realistic.

A further aspect sporadically explored by scientific literature relates to the territorial roots of candidates. The local status of candidates has usually been investigated in relation to their previous institutional experiences at the local level (Put and Maddens 2013; Dvořák and Pink 2023) without in-depth investigations into its influence. As scientific literature has extensively highlighted, territorial rootedness constitutes a significant competitive advantage for candidates (Shugart et al., 2005; Tavits 2010; Arzheimer and Evans 2012; Gorecki and Marsh 2012; Roy and Alcantara 2015; Jankowski 2016; Put, Smulders and Maddens 2019). Candidates with strong local roots can be perceived by voters as more attentive to the needs of their community, more aware of their problems, and therefore more dedicated to their resolution (Campbell and Cowley 2014). In this way, candidates with greater localness would have a competitive advantage over those with less rootedness at the time of elections. Specifically in reference to the Italian case, literature has highlighted how—in the context of single-member districts—candidates with greater localness tend to have a competitive advantage over others in terms of personal vote collection (Boldrini 2020, 2023). It can thus be imagined that, analogously to what was said earlier, candidates with stronger territorial rootedness will be positioned higher by parties, thus ensuring greater visibility to candidates, and seeking to increase their consensus.

H3: Candidates with higher territorial rootedness have greater chances of being placed in positions where election is more realistic.

Another aspect of analysis relates to the gender dimension. In fact, literature has shown that being a woman is negatively correlated with receiving a position on the list where the chances of being elected are higher (Chiru and Popescu 2017; Meserve, Pemstein and Bernhard 2020; Dvořák and Pink 2023). In Italy, the gender gap is widely highlighted by scholars, with women—in addition to being fewer in number than men—having less structured and linear careers (Carbone and Farina 2020; Sampugnaro 2020; Sampugnaro and Montemagno 2020; Boldrini and Grimaldi 2023). Despite the introduction of an electoral law that provides for strong gender quotas aimed at promoting better gender parity, literature has shown how parties use strategies to limit the effectiveness of these gender-balancing provisions (Pansardi and Pedrazzani 2023). Analyses have indeed shown that women are frequently nominated in positions on the list where the chances of election are lower, or in single-member districts with lower competitiveness (De Lucia and Paparo 2019; Boldrini, Improta and Paparo 2024). Based on this, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

H4: Female candidates have a lower chance of being placed in positions where election is more realistic.

Finally, a last aspect to examine relates to the dynamics of the electoral system. As mentioned earlier, the Italian electoral system is a mixed-type electoral system, with approximately two-thirds of seats assigned in proportional multi-member districts (MMDs) with closed lists and one-third in single-member districts (SMDs) (Chiaramonte and D’Alimonte 2018). Literature on nominations in mixed electoral systems has highlighted a positive correlation between candidacy in SMDs and candidacy in MMDs (Ceyhan 2018). The reasons for this influence must be sought precisely in the reciprocal influence that the two different arenas have on each other. As secure as they may be, candidacies in single-member districts expose candidates to a higher risk of non-election compared to a top position within a closed list. Candidates in SMDs might therefore require greater protection, and as such, they may be nominated in safer positions in the proportional part, as demonstrated by investigations into the German case (Reiser 2014). Conversely, parties have an interest in nominating individuals in SMDs who are capable of gathering significant percentages of support because they will serve to increase the party’s support in the proportional part. Regarding the Italian case, research has highlighted a widespread tendency to use ‘vertical’ plural candidacies between SMDs and MMDs, differentiating also according to the type of political figure, with politicians with national experience using dual candidacy more widely than outsiders (De Lucia and Paparo 2019). It can indeed be imagined that candidates who are more relevant in terms of resources can constitute an important competitive advantage for parties in SMDs. However, precisely because of their greater resources, they can negotiate positions on the list where it is more realistic to be elected. For example, incumbent candidates, those with higher political experience, or those with stronger territorial rootedness, who have been nominated in SMDs, can be placed higher on the list, both compared to other dual candidates and to those candidates with similar characteristics but who lack a dual mandate. Based on this, the final set of hypotheses of the analysis can be enunciated:

H5: Dual candidates have a greater chance of being placed in positions where election is more realistic.

H6: Incumbent dual candidates have a greater chance of being placed in positions where is election more realistic compared to other incumbent candidates.

H7: Dual candidates with longer national career have a greater chance of being placed in positions where election is more realistic compared to other candidates with longer national career.

H8: Dual candidates with higher territorial rootedness have a greater chance of being placed in positions where election is more realistic compared to other candidates with territorial rootedness.

5. Data and method

As previously mentioned, research on the factors influencing candidate placement on electoral lists has not been extensively investigated by scholars. Researchers have extensively examined countries with flexible proportional representation systems, such as Belgium (Put and Maddens 2013, 2015; Put, Smulders and Maddens 2019, 2021a, 2021b), the Czech Republic (Dvořák and Pink 2023), and Sweden (Däubler, Christensen and Linek 2018), while studies on closed-list systems have been less common (Gherghina and Chiru 2010; Chiru and Popescu 2017), and studies on mixed systems have been relatively rare (Ceyhan 2018).

The analysis focussed on candidates in the 2022 Italian general elections for the chamber of deputies presented by the following political parties: the centre-left coalition formed by the Partito Democratico, Più Europa, Alleanza Verdi Sinistra, and Impegno Civico; the centre-right coalition formed by Fratelli d’Italia (FDI), Lega per Salvini, Forza Italia, and Noi Moderati; the Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S); and the united list Azione-Italia Viva. The choice to focus only on these lists was dictated by the need for comparability and reliability of the results. Including parties with very few or even no chances of electing deputies (both in the SMDs and in the MMDs) would have necessarily made data collection less reliable and the analysis less robust. The analysis thus covered a total of 1,898 candidates.

Furthermore, the research focuses solely on candidates for the Chamber of Deputies to enhance the comparative value (Sartori 2011) of the research. As is well known, the Italian Senate constitutes an anomaly within the landscape of European upper houses, as it is essentially a duplicate of the lower house, albeit with some significant differences regarding passive electorate requirements. Including candidates for the Senate would therefore diminish the comparative value of the research results in relation to other country cases due to this specificity.

The analysis is based on a multivariate analysis conducted with multivariate linear regression with OLS. For greater explanatory power, the analysis includes five different models: one general model that includes all the independent variables, and one different model for each interaction analysis.

Regarding the dependent variable, as previously mentioned, the traditional conceptualization following Duverger (1951), which divides positions based on their associated probability of election, is considered not entirely satisfactory. This division is commendable for its simplicity and intuitiveness, but it has some limitations.

Firstly, this distinction seems to work well in relatively stable contexts, where it is easy to predict the election probabilities associated with each position. In more volatile contexts, where there are significant vote shifts between elections, it becomes more challenging to determine the real chances of election since even less relevant positions can become significant due to a sudden increase in votes.

Secondly, it is not easily applicable in a comparative perspective, not only between different countries but also between different parties. This is because, depending on the size of a party, positions with significant election probabilities can vary greatly based on the party’s size and its geographical distribution of votes.

Ultimately, Duverger’s distinction is particularly useful for distinguishing the top positions (those with higher election probabilities) from the bottom ones (where the chances of being elected are lower). However, it does not allow for easy differentiation among the various intermediate positions, hindering the overall understanding of how lists are constructed.

To address these limitations, a different operationalization of the list position has been chosen, based on a progressive decrease in election probability as one moves down the list. This approach, although simple, can better facilitate the understanding of how political parties construct their lists.

Thus, the dependent variable is the position in the MMD list occupied by each candidate. As previously mentioned, Italian electoral law allows the candidacy of up to four candidates in each closed-list MMD, which means that the allocation of seats to candidates is carried out solely based on the position in which candidates were included in the list. Among the positions, a precise hierarchy of both visibility and realistic probability of election is therefore created. The first positions are associated with very high election chance, especially for the first—defined as ‘head of the list’1—then decreasing progressively for the third and fourth position, in which—conversely—the chances of elections are almost nil, especially for the smaller parties. Operationally, for the sake of simplicity of the analysis, the variable was considered as a continuous variable, which can take on values between 1 (maximum chance of election) and 4 (minimum chance of election).

Regarding the independent variables, incumbency, national political career, territorial localness, gender, and dual candidacy were considered. Incumbency has been operationalized as a dichotomous variable, with a value of zero if the candidate is not an incumbent and one if they are, considering their incumbency both in the Chamber and in the Senate.

On the contrary, the national political career has been operationalized as an ordinal variable, considering the number of national mandates (both in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate) held by each candidate. The logic behind this type of operationalization is to highlight how longer national political careers can lead to stronger expertise and know-how in terms of political skills (Claessen 2023). The variable will have a value of zero if the candidate has not previously held any national-level terms, and at most, the maximum number of mandates held over the course of their political career.

Following part of the literature (Marangoni and Tronconi 2009; Boldrini 2020, 2023), the level of territorial localness has been operationalized as an ordinal variable, constructing an index of localness. The candidate was assigned one point if they were born in one of the municipalities—wholly or partially—in the candidacy MMD, one point if the candidate held at least one mandate in a local institution (Municipality, Province, or Region) present—wholly or partially—in the MMD, and an additional point if the position is held at the time of the candidacy. In this way, an ordinal variable is obtained with a minimum value of zero (no localness) and three (maximum localness for candidates who were born in the MMD and are holding a position in the local government at the time of the candidacy).

As for gender and dual mandates, they have been operationalized as dichotomous variables with a value of one if the candidate is a woman for gender and if they were a candidate both in the SMDs and in the MMDs.

To increase the robustness of the analysis, some control variables related to age, the presence of multi-candidacies, and party size have been introduced.

Age has been calculated by subtracting the year of birth of each candidate from the year of the election and has been operationalized as an ordinal variable, with five different modalities depending on whether the candidate’s age in completed years falls within the following categories (25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75 or more).

As previously mentioned, the electoral law allows for up to five multi-candidacies in the MMDs. To avoid possible distortions related to this possibility, an ordinal variable has been introduced (ranging from one to five, depending on the number of candidacies in the MMDs) aimed at controlling for the presence of multi-candidacies.

Finally, a control variable has been introduced to account for party size. Different parties of different sizes can naturally have different strategies for the candidacy in MMDs. Smaller parties have a lower probability of electing many MPs and consequently will be more inclined to evaluate differently the chances of election associated with the different positions. To this end, a control variable has been introduced, calculated as the average share of votes that the polls in the months of July and August attributed to each party. Data were calculated through the official website that collects Italian political polls (www.sondaggipoliticoelettorali.it), including all polls between 1 July 2022 and 22 August 2022 (deadline for candidate submissions). This period has been selected since it is imagined that the parties’ candidacy choices are made based on the share of votes attributed by the polls in the weeks leading up to the deadline.2

The analysis is based on an original dataset constructed from official data available in the archives of major Italian institutions. For the main sociodemographic variables (age, gender, place of birth) and political variables (dual candidacy, multi-candidacy), the data were collected automatically from the archive of the Ministry of the Interior related to the 2022 political elections. Career-related data were extracted from datasets available on the websites of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic for national career and incumbency, while data on localness were obtained from the Registry of Local and Regional Administrators on the Ministry of the Interior’s website. Candidates for the 2022 political elections were then manually searched (by name, surname, date, and place of birth to avoid cases of homonymy) in the other datasets, allowing their previous national career and level of localness to be associated with each. The decision to conduct a manual rather than automated search—which took about two months—was made to ensure better data reliability3.

6. Data analysis and discussion

Table 1 presents the results of the multivariate analysis. Model 1 illustrates the results of the OLS regression with all independent variables included, while Models 2 to 5 explore different interaction models. Standard errors have been clustered based on the region in which the MMDs are located.

| Independent variables . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National incumbent | −0.348*** | −0.571*** | −0.497*** | −0.477*** | −0.477*** |

| (0.101) | (0.108) | (0.101) | (0.101) | (0.101) | |

| National career | −0.127*** | −0.190*** | −0.268*** | −0.200*** | −0.200*** |

| (0.0506) | (0.0505) | (0.0593) | (0.0551) | (0.0502) | |

| Localness | −0.182*** | −0.179*** | −0.178*** | −0.178*** | −0.179*** |

| (0.0246) | (0.0265) | (0.0250) | (0.0259) | (0.0256) | |

| Female | 0.186*** | 0.181*** | 0.177*** | 0.183*** | 0.186*** |

| (0.0461) | (0.0460) | (0.0460) | (0.0554) | (0.0467) | |

| Dual candidate | −0.285*** | −0.426*** | 0.746** | −0.267*** | −0.264* |

| (0.0603) | (0.0886) | (0.203) | (0.0580) | (0.101) | |

| Dual candidate × incumbent | – | 0.383** | – | – | – |

| – | (0.125) | – | – | – | |

| Dual candidate × national career | – | – | 0.612** | – | – |

| – | – | (0.200) | – | – | |

| Dual candidate × female | – | – | – | 0.014 | – |

| – | – | – | (0.111) | – | |

| Dual candidate × local candidate | – | – | – | – | 0.0045 |

| – | – | – | – | (0.0761) | |

| Control variables | |||||

| Age cohort reference category: 25–34 | |||||

| 35–44 | −0.272** | −0.257** | −0.258** | −0.256** | −0.257** |

| (0.0692) | (0.0739) | (0.0761) | (0.0695) | (0.0693) | |

| 45–54 | −0.346** | −0.358** | −0.363** | −0.355** | −0.355** |

| (0.0994) | (0.102) | (0.103) | (0.0990) | (0.0994) | |

| 55–64 | −0.292** | −0.315** | −0.307** | −0.313** | −0.314** |

| (0.0883) | (0.0886) | (0.0885) | (0.0870) | (0.0885) | |

| 65–74 | −0.365*** | −0.411*** | −0.423*** | −0.419*** | −0.419*** |

| (0.0769) | (0.0800) | (0.0819) | (0.0759) | (0.0768) | |

| 75 or more | −0.469*** | −0.787*** | −0.739*** | -0.758*** | -0.759*** |

| (0.172) | (0.158) | (0.163) | (0.173) | (0.174) | |

| Pluri-candidacy | −0.133*** | −0.133*** | −0.132*** | −0.133*** | −0.133*** |

| (0.0115) | (0.0119) | (0.0113) | (0.0117) | (0.0115) | |

| Party magnitude | 0.007** | 0.00884** | 0.00928** | 0.00876** | 0.00879** |

| (0.00245) | (0.00248) | (0.00247) | (0.00246) | (0.00246) | |

| _cons | 3.134*** | 3.333*** | 3.360*** | 3.317*** | 3.316*** |

| (0.0717) | (0.0762) | (0.0725) | (0.078) | (0.0762) | |

| N | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 |

| R-sq | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 |

| Independent variables . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National incumbent | −0.348*** | −0.571*** | −0.497*** | −0.477*** | −0.477*** |

| (0.101) | (0.108) | (0.101) | (0.101) | (0.101) | |

| National career | −0.127*** | −0.190*** | −0.268*** | −0.200*** | −0.200*** |

| (0.0506) | (0.0505) | (0.0593) | (0.0551) | (0.0502) | |

| Localness | −0.182*** | −0.179*** | −0.178*** | −0.178*** | −0.179*** |

| (0.0246) | (0.0265) | (0.0250) | (0.0259) | (0.0256) | |

| Female | 0.186*** | 0.181*** | 0.177*** | 0.183*** | 0.186*** |

| (0.0461) | (0.0460) | (0.0460) | (0.0554) | (0.0467) | |

| Dual candidate | −0.285*** | −0.426*** | 0.746** | −0.267*** | −0.264* |

| (0.0603) | (0.0886) | (0.203) | (0.0580) | (0.101) | |

| Dual candidate × incumbent | – | 0.383** | – | – | – |

| – | (0.125) | – | – | – | |

| Dual candidate × national career | – | – | 0.612** | – | – |

| – | – | (0.200) | – | – | |

| Dual candidate × female | – | – | – | 0.014 | – |

| – | – | – | (0.111) | – | |

| Dual candidate × local candidate | – | – | – | – | 0.0045 |

| – | – | – | – | (0.0761) | |

| Control variables | |||||

| Age cohort reference category: 25–34 | |||||

| 35–44 | −0.272** | −0.257** | −0.258** | −0.256** | −0.257** |

| (0.0692) | (0.0739) | (0.0761) | (0.0695) | (0.0693) | |

| 45–54 | −0.346** | −0.358** | −0.363** | −0.355** | −0.355** |

| (0.0994) | (0.102) | (0.103) | (0.0990) | (0.0994) | |

| 55–64 | −0.292** | −0.315** | −0.307** | −0.313** | −0.314** |

| (0.0883) | (0.0886) | (0.0885) | (0.0870) | (0.0885) | |

| 65–74 | −0.365*** | −0.411*** | −0.423*** | −0.419*** | −0.419*** |

| (0.0769) | (0.0800) | (0.0819) | (0.0759) | (0.0768) | |

| 75 or more | −0.469*** | −0.787*** | −0.739*** | -0.758*** | -0.759*** |

| (0.172) | (0.158) | (0.163) | (0.173) | (0.174) | |

| Pluri-candidacy | −0.133*** | −0.133*** | −0.132*** | −0.133*** | −0.133*** |

| (0.0115) | (0.0119) | (0.0113) | (0.0117) | (0.0115) | |

| Party magnitude | 0.007** | 0.00884** | 0.00928** | 0.00876** | 0.00879** |

| (0.00245) | (0.00248) | (0.00247) | (0.00246) | (0.00246) | |

| _cons | 3.134*** | 3.333*** | 3.360*** | 3.317*** | 3.316*** |

| (0.0717) | (0.0762) | (0.0725) | (0.078) | (0.0762) | |

| N | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 |

| R-sq | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

| Independent variables . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National incumbent | −0.348*** | −0.571*** | −0.497*** | −0.477*** | −0.477*** |

| (0.101) | (0.108) | (0.101) | (0.101) | (0.101) | |

| National career | −0.127*** | −0.190*** | −0.268*** | −0.200*** | −0.200*** |

| (0.0506) | (0.0505) | (0.0593) | (0.0551) | (0.0502) | |

| Localness | −0.182*** | −0.179*** | −0.178*** | −0.178*** | −0.179*** |

| (0.0246) | (0.0265) | (0.0250) | (0.0259) | (0.0256) | |

| Female | 0.186*** | 0.181*** | 0.177*** | 0.183*** | 0.186*** |

| (0.0461) | (0.0460) | (0.0460) | (0.0554) | (0.0467) | |

| Dual candidate | −0.285*** | −0.426*** | 0.746** | −0.267*** | −0.264* |

| (0.0603) | (0.0886) | (0.203) | (0.0580) | (0.101) | |

| Dual candidate × incumbent | – | 0.383** | – | – | – |

| – | (0.125) | – | – | – | |

| Dual candidate × national career | – | – | 0.612** | – | – |

| – | – | (0.200) | – | – | |

| Dual candidate × female | – | – | – | 0.014 | – |

| – | – | – | (0.111) | – | |

| Dual candidate × local candidate | – | – | – | – | 0.0045 |

| – | – | – | – | (0.0761) | |

| Control variables | |||||

| Age cohort reference category: 25–34 | |||||

| 35–44 | −0.272** | −0.257** | −0.258** | −0.256** | −0.257** |

| (0.0692) | (0.0739) | (0.0761) | (0.0695) | (0.0693) | |

| 45–54 | −0.346** | −0.358** | −0.363** | −0.355** | −0.355** |

| (0.0994) | (0.102) | (0.103) | (0.0990) | (0.0994) | |

| 55–64 | −0.292** | −0.315** | −0.307** | −0.313** | −0.314** |

| (0.0883) | (0.0886) | (0.0885) | (0.0870) | (0.0885) | |

| 65–74 | −0.365*** | −0.411*** | −0.423*** | −0.419*** | −0.419*** |

| (0.0769) | (0.0800) | (0.0819) | (0.0759) | (0.0768) | |

| 75 or more | −0.469*** | −0.787*** | −0.739*** | -0.758*** | -0.759*** |

| (0.172) | (0.158) | (0.163) | (0.173) | (0.174) | |

| Pluri-candidacy | −0.133*** | −0.133*** | −0.132*** | −0.133*** | −0.133*** |

| (0.0115) | (0.0119) | (0.0113) | (0.0117) | (0.0115) | |

| Party magnitude | 0.007** | 0.00884** | 0.00928** | 0.00876** | 0.00879** |

| (0.00245) | (0.00248) | (0.00247) | (0.00246) | (0.00246) | |

| _cons | 3.134*** | 3.333*** | 3.360*** | 3.317*** | 3.316*** |

| (0.0717) | (0.0762) | (0.0725) | (0.078) | (0.0762) | |

| N | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 |

| R-sq | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 |

| Independent variables . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National incumbent | −0.348*** | −0.571*** | −0.497*** | −0.477*** | −0.477*** |

| (0.101) | (0.108) | (0.101) | (0.101) | (0.101) | |

| National career | −0.127*** | −0.190*** | −0.268*** | −0.200*** | −0.200*** |

| (0.0506) | (0.0505) | (0.0593) | (0.0551) | (0.0502) | |

| Localness | −0.182*** | −0.179*** | −0.178*** | −0.178*** | −0.179*** |

| (0.0246) | (0.0265) | (0.0250) | (0.0259) | (0.0256) | |

| Female | 0.186*** | 0.181*** | 0.177*** | 0.183*** | 0.186*** |

| (0.0461) | (0.0460) | (0.0460) | (0.0554) | (0.0467) | |

| Dual candidate | −0.285*** | −0.426*** | 0.746** | −0.267*** | −0.264* |

| (0.0603) | (0.0886) | (0.203) | (0.0580) | (0.101) | |

| Dual candidate × incumbent | – | 0.383** | – | – | – |

| – | (0.125) | – | – | – | |

| Dual candidate × national career | – | – | 0.612** | – | – |

| – | – | (0.200) | – | – | |

| Dual candidate × female | – | – | – | 0.014 | – |

| – | – | – | (0.111) | – | |

| Dual candidate × local candidate | – | – | – | – | 0.0045 |

| – | – | – | – | (0.0761) | |

| Control variables | |||||

| Age cohort reference category: 25–34 | |||||

| 35–44 | −0.272** | −0.257** | −0.258** | −0.256** | −0.257** |

| (0.0692) | (0.0739) | (0.0761) | (0.0695) | (0.0693) | |

| 45–54 | −0.346** | −0.358** | −0.363** | −0.355** | −0.355** |

| (0.0994) | (0.102) | (0.103) | (0.0990) | (0.0994) | |

| 55–64 | −0.292** | −0.315** | −0.307** | −0.313** | −0.314** |

| (0.0883) | (0.0886) | (0.0885) | (0.0870) | (0.0885) | |

| 65–74 | −0.365*** | −0.411*** | −0.423*** | −0.419*** | −0.419*** |

| (0.0769) | (0.0800) | (0.0819) | (0.0759) | (0.0768) | |

| 75 or more | −0.469*** | −0.787*** | −0.739*** | -0.758*** | -0.759*** |

| (0.172) | (0.158) | (0.163) | (0.173) | (0.174) | |

| Pluri-candidacy | −0.133*** | −0.133*** | −0.132*** | −0.133*** | −0.133*** |

| (0.0115) | (0.0119) | (0.0113) | (0.0117) | (0.0115) | |

| Party magnitude | 0.007** | 0.00884** | 0.00928** | 0.00876** | 0.00879** |

| (0.00245) | (0.00248) | (0.00247) | (0.00246) | (0.00246) | |

| _cons | 3.134*** | 3.333*** | 3.360*** | 3.317*** | 3.316*** |

| (0.0717) | (0.0762) | (0.0725) | (0.078) | (0.0762) | |

| N | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 |

| R-sq | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The first model highlights a statistically significant effect for all considered independent variables.

Incumbency appears to have the strongest effect on list placement. Being an incumbent is negatively correlated with list position (−0.348, 99% confidence interval [CI]), with the coefficient being the most substantial among those presented here. This indicates a higher influence of incumbency compared to other variables. Essentially, being an MP in the previous legislature favours inclusion in the top positions of the list, where the likelihood of election is higher. Thus, hypothesis H1 is confirmed.

A similar result is observed for national political career and localness. Both show a negative correlation with list position (−0.127 for national career and −0.182 for localness, both significant at 99% CI). As experience as a national MP and levels of localness increase, candidates are more likely to be placed in higher positions on the list. Consequently, both hypotheses H2 and H3 are confirmed.

Regarding gender, the regression highlights a positive influence on list position (0.186, 99% CI). This is the only variable showing a positive influence and indicates that female candidates are generally placed in lower positions compared to their male counterparts. Thus, hypothesis H4 is confirmed.

Finally, the analysis reveals a statistically significant negative correlation between being a candidate in both arenas and list position (−0.285, 99% CI). Essentially, candidates who have accepted a position in SMDs are generally positioned higher on the list, thus having a greater chance of election in the majoritarian part. In this case, hypothesis H5 is also confirmed.

Next, we explore the results of the various interaction models. Model 2 illustrates the effects of the interaction between incumbency and dual candidacy. The analysis highlights a positive and statistically significant association for this interaction model, which contradicts the initial hypothesis. To better understand these results, the interaction plot (Fig. 1) shows the marginal effects of being an incumbent on list position, considering the interaction with dual candidacy.

As shown in the graph, the two CIs overlap, indicating that the effect is not statistically significant. Both being an incumbent and being a dual candidate are confirmed as the variables with the greatest effect on list position, even within the interaction model. Overall, there does not appear to be a statistically significant interaction effect between being an incumbent candidate and being a candidate in both tiers. Instead, the effect of being an incumbent and a dual candidate seems to be more pronounced. Therefore, hypothesis H6 is not confirmed.

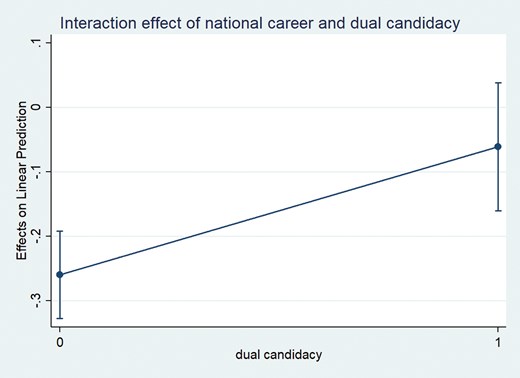

Regarding the interaction between national career and dual candidacy, Model 2 presents the results. The analysis highlights a statistically significant positive association (coefficient 0.612, 99% CI) between being a dual candidate and having a national career, which is also confirmed by the marginal effects graph (Fig. 2).

Contrary to expectations, the interaction coefficient has a positive value, indicating that there is not a multiplicative effect of dual candidacy and having a national career but rather a moderating effect. Specifically, being a dual candidate moderates the effect of having previous national experience, leading to a lower likelihood of being placed in more prominent list positions in terms of election probabilities. Conversely, both dual candidacy and national experience are confirmed as statistically significant and positively associated with more favourable list positions. Therefore, hypothesis H7 is not confirmed.

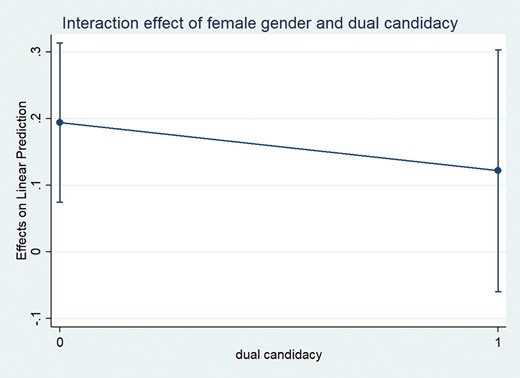

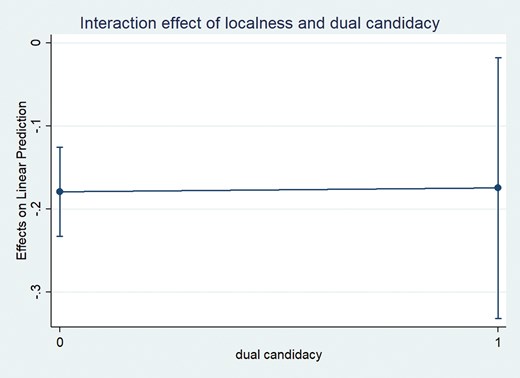

Finally, Models 4 and 5, which examine the interactions between dual candidacy and gender, and dual candidacy and levels of localness, do not show any statistical significance. This finding is also confirmed by the marginal effect plots presented in Figs 3 and 4.

Regarding the pathways of candidate circulation and recruitment, the analysis suggests a strong control over candidacies, which limits the election opportunities for outsider candidates, particularly women and non-incumbents. This does not mean that there is no space for those individuals to be placed in more relevant positions, but rather that the parties’ candidacy strategies tend to disadvantage them. The results align with literature on proportional systems, which highlights how parliamentary turnover decreases as the proportional system becomes more closed (Passarelli 2020), both in terms of general list placement (André et al. 2017; Ceyhan 2018; Meserve, Pemstein and Bernhard 2020; Put et al. 2021a, 2021b; Passarelli 2023). Muyters and Maddens (2023) have highlighted that high electoral volatility can influence the positioning of incumbents in better positions. Essentially, the expected victory of FDI led incumbent candidates to negotiate positions with higher election probabilities. This effect certainly impacted parties in the centre-left coalition and the M5S, but also those in the centre-right coalition—such as Salvini’s League, which saw its support halved (Chiaramonte & De Sio, 2024). Additionally, compared to 2018, the reduction in the number of seats has led to a substantial “entrenchment” of incumbent candidates in the best positions. Therefore, the combination of these conjunctural factors may explain the strong influence of incumbency on list positioning in the 2022 Italian elections.

Another finding of the research is related to the contamination effects between the two electoral arenas. The analysis seems to show that there was no influence of the two different electoral arenas in shaping the candidacies. The only statistically significant influence appears to be related to national career, but counterintuitively, the effect is negative, with dual national candidates running in MMDs in positions where the probability of election tends to be lower. In this case, the research highlights results that diverge from what is stated in the literature (Ceyhan 2018), with a dual candidacy effect that is not particularly strong and, in some cases, entirely absent. However, it can be assumed that this result can be attributed to the structure of the electoral law and the specific conditions of the 2022 elections.

First, the Italian electoral law is primarily proportional, with only 37% of seats allocated in SMDs. The reduced number of SMDs may have diminished the possibility of a contagion effect in candidacies, making the MMDs the main arena determining candidacy strategies.

Second, the centre-right’s large dominance in the SMDs (where it won about 80% of the seats), combined with the use of multi-candidacies, reduced the importance of negotiating nominations in positions with higher chances of election. In the case of multi-candidacies, being elected in several constituencies requires the candidate to choose one, with the second on the list being elected in the others. Thus, national candidates, who were in safe constituencies or protected by multi-candidacies, could accept positions in the MMDs where the chances of election were theoretically less realistic, counting on a shift in the list. It can be hypothesized that there is a relationship between the strength of the contagion effect between the two arenas and its expected outcome. The more overwhelming the estimated victory of a party or coalition in one arena—here, the majoritarian arena—the lower the contagion effect between the two, leading to different candidacy dynamics. However, these are only provisional results and require further investigation.

7. Conclusion

This article aimed to investigate which factors favoured the listing of candidates in certain positions. Specifically, by examining the 2022 Italian general election, it sought to contribute to the scientific literature on candidacies, exploring how candidates’ political and personal characteristics affected their positioning on the list in a mixed electoral system. Certain characteristics may indeed have a different influence in a context where dual candidacy is possible in two different arenas.

The research provides a threefold contribution.

First of all, it argued that the traditional classification of positions provided by Duverger is found to be insufficient, suggesting instead a more empirical conceptualization linked to the actual position on the list. This approach ensures greater comparability and a more complete understanding of the dynamics behind party list construction, beyond just the most relevant positions.

Secondly, from an empirical perspective, the analysis confirms the initial expectations. Parties tend to use higher positions for incumbent MPs, candidates with longer national careers, and those more deeply rooted in their constituencies. Conversely, despite gender equality regulations, female candidates were generally placed in lower list positions, where the chances of election were reduced.

Lastly, from a theoretical point of view the literature has been largely confirmed.

Beyond the legal framework, women’s participation in politics continues to be limited by party strategies that make it more difficult for women to be elected. Moreover, parties tend to favour incumbents, more experienced, and more locally rooted candidates by placing them in higher positions to facilitate their election and increase their visibility during the campaign. Among these factors, incumbency appears to play a central role, with a higher influence than the others. The reproduction of the existing political class seems to be the decisive factor in how parties compose their lists, beyond volatility and, in some cases, precisely due to it.

Furthermore, the analysis shows a limited influence of the mixed electoral system. The ‘contamination effect’ between the two arenas seems to be less extensive than theoretically assumed, and in some cases, it exhibits an opposite effect. The dynamics of candidate selection in the proportional tiers appear to be largely independent—and to some extent predominant—with regard to the SMDs. However, these results might be attributable to the specific political conditions of the 2022 election, with the centre-right leading in almost all SMDs, making it a less salient arena of competition and thus reducing the potential for blackmail in this arena. The contamination effect between the two arenas in defining candidacies seems to be influenced by the perceived outcome of the competition. The more decisive the outcome appears to be, the lower the contamination effect.

The article opens several avenues for further research. A first line of inquiry could be comparative in nature, exploring more deeply the existence of the relationship between the contamination effect and election expectations. A second possibility is to investigate whether different parties with various organizational structures employ distinct candidacy strategies. These investigations could further explore this ‘secret garden of politics.’

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at Parliamentary Affairs online.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

This study received no specific funding.

References

Footnotes

‘Capolista’ in Italian.

A table summarizing all variables and their operationalization is available in Supplementary Materials.

Specifically, the aim was to avoid the possibility that different candidates—such as those with more than one name or surname—might be recorded differently in the various datasets. This issue can arise, particularly with older data present in the Registry of Local and Regional Administrators, where reliability levels are lower.