-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Katrin Praprotnik, Maria Thürk, Svenja Krauss, Duration of coalition formation in the German states: Inertia and familiarity in a multilevel setting, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 78, Issue 2, April 2025, Pages 304–328, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsae014

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Only gradually, scholars began to show interest in party competition at the sub-national level. Yet, we still know very little about how long it takes until a regional government gets into office. To narrow this research gap, we examine the effect of previous government experience between parties at the regional and national levels. Government formation processes are expected to be faster if parties currently govern together—i.e. have inertia—or have previous government experience—i.e. have familiarity—at the regional and/or national level. We test our expectations by relying on a newly compiled, comprehensive dataset about government formation duration in Germany between 1949 and 2020. Our hypotheses are largely supported: parties are faster in forming coalition governments if they have inertia at the regional or national level and if they have national familiarity. Our results have important implications for our understanding of the interplay between the national and sub-national levels.

1. Introduction

On 23 April 1967, citizens of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein were called to the polls to vote for a new state parliament. Only 10 days later, their new state government was sworn in. The Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) had reached an agreement with the Free Democratic Party (FDP) and renewed their coalition agreement from 1963. On 22 September 2013, citizens of the German state Hesse could vote for their new state parliament. Yet, it took 118 days—almost 4 months—until the new government took office. These two examples show the range of coalition formation duration we observe at the state level in Germany. In Hesse, the CDU struck out a coalition deal with the Greens that consequently regained governmental power after a long period in opposition. Moreover, it was only the second time ever that the CDU formed a coalition with the Greens—for the first time in a so-called Flächenland.1 In contrast, the CDU and FDP have a long tradition as coalition partners in almost all state governments as well as on the federal level.

Timing, however, is crucial for political systems: The longer the duration of coalition formation, the more likely are detrimental effects on a state’s democratic and economic development. During the period of coalition formation, caretaker cabinets commonly take over the business of government as acting administrations. However, caretaker governments lack democratic legitimacy, accountability, and responsiveness (Schleiter and Belu 2015). Moreover, caretaker cabinets are only allowed to administrate government business, which can lead to policy paralysis and administrative inefficiency, as critical decisions are delayed or postponed (Martin and Vanberg 2003). This can hinder effective responses to pressing issues, economic challenges, and social concerns. Furthermore, research shows that the absence of a fully functional government can lead to economic problems such as higher investment risks (Bechtel 2009) and deter foreign investment (Bernhard and Leblang 2002, 2006). Specifically, for the German states having no elected government can weaken a state’s bargaining position on the national level, too, which would lead to losses in national policy influence. Overall, extensive cabinet formation periods undermine the smooth functioning of a state’s institutions, disrupt the implementation of crucial policies, and hamper its overall development.

Despite this significant variation in the duration of government formation among governments in Germany and the crucial importance of understanding the formation duration processes, scholars have shown only limited interest in understanding why some coalitions form quickly after election day, while others take months to build [but see Bäck et al., (2024a) for a most notable exception]. The emerging literature on sub-national coalitions is centred on the partisan composition of a government (Däubler and Debus 2009; Shikano and Linhart 2010; Falcó-Gimeno and Verge 2013; Albala and Reniu 2019), the process of coalition governance (Krauss et al., 2021), and the termination of coalitions (Martínez-Cantó and Bergmann 2020).

Even at the national level, where coalition research is among the liveliest fields in comparative politics, the duration of coalition building has only gained limited attention (Ecker and Meyer 2015, 2020). Diermeier and van Roozendaal (1998) argue that bargaining uncertainty, which refers to the unfamiliarity of the policy preferences among the key political actors needed for government formation, is central to understanding lengthy coalition formation periods, while Martin and Vanberg (2003) state that bargaining complexity, which refers to the number of potential bargaining partners and the heterogeneity in their policy preferences, is central to explaining long negotiations. Golder (2010) argues that bargaining complexity is only relevant when there is high uncertainty among the involved actors, while uncertainty always prolongs coalition negotiations.

Additionally, Ecker and Meyer (2015) find robust results for coalition formation in Central and Eastern Europe only for bargaining uncertainty, and Giannetti et al. (2020) show that increased complexity in terms of including partisan incongruence in the second chamber does not lead to longer bargaining duration. Furthermore, the most consistent finding in the literature is that formation processes directly after elections take longer periods of time than formations later during the legislative term due to decreased uncertainty among the actors (Falcó-Gimeno and Indridason 2013). Ecker and Meyer (2020) present an actor-specific approach and concentrate on party-level attributes instead of party system-level ones. They show that party leadership tenure and incumbency significantly shorten successful coalition formation negotiations, which strongly supports that decreased levels of uncertainty are central. Furthermore, Bäck et al., (2024b) show that if there is too little familiarity among the partisan actors, negotiations may fail and longer coalition formation durations are expected.

In the present article, we examine the factors of inertia and familiarity at both the regional and national levels in order to explain coalition formation duration in the German Bundesländer. This allows us to advance the literature as follows: First, this is the first contribution that brings the arguments of co-governance experience into an analysis of the duration of German sub-national bargaining processes. Second, we contribute by arguing that multilevel structures crucially affect party behaviour. More specifically, we hypothesize that co-governance at the national level positively affects the actors on the Länder level and thus decreases the coalition formation duration. Therefore, looking at the sub-national level does not simply enlarge the number of potential cases (also see Deschouwer 2009: 14), but it allows us to examine party behaviour in a multilevel setting.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In the subsequent section, we theorize the effect of co-governance experience on the duration of regional bargaining processes. We elaborate on the concept of co-governance, operationalized as inertia and familiarity both at the state and national levels. The third section presents our newly compiled data set on coalition negotiations in Germany between 1949 and 2020. The fourth section is devoted to the multivariate analyses. Our models reveal that the national level has an important influence on government formation duration at the regional level.

2. Theory: Co-governance experience in regional coalition talks

Studies in the field of party competition in general and coalition research more specifically often start with two basic assumptions on their main actors which are political parties. First, political parties are understood as rational utility-maximizers that strive to increase their benefits in terms of votes, policies, and offices (Downs 1957; Strøm 1990). Second, political parties are understood as unitary actors operating under one-party label (Laver and Schofield 1990; Tsebelis 2002). Acknowledging multilevel governance in political systems, however, only the first assumption remains valid. Political parties consist of national, regional, local, and European party organizations. While all of them can be understood as rational in the tradition of Downs, packing them into one box would be an oversimplification that is not justifiable in the present study on regional government formation duration (Hopkin 2003).

Depending on constitutional powers, regional parties are more or less independent from their national party branch. Regional actors choose their candidates or write their own electoral programs (Laffin et al., 2007). Scholars even have reported programmatic differences between regional and national manifestos (Pogorelis et al., 2005; Debus 2008). At the same time, however, this autonomy is limited, since regional actors do not compete in a vacuum, but are embedded in the national political landscape (Jeffery and Hough 2001). Libbrecht et al. (2011), for example, point out that sub-national actors sometimes refrain from the most logical campaign strategies if they run counter their dominant national strategy. This is still a reasonable behaviour, since surveys regularly reveal that voters take national factors into account when making their regional vote choice. National incumbents tend to be punished in the regional election in times of poor national economic conditions (Thorlakson 2016).

The interplay between the regional and the national levels is thus quite evident. Strategic regional actors that aim to maximize their electoral benefit in the run-up to an election try to incorporate the national level in case they expect to benefit from it electorally. In a situation where there is a single party holding a parliamentary majority, there is no need for parties to negotiate a coalition deal with another party. Intra-party positions are known both at one level as well as across levels. In contemporary parliamentary democracies, however, coalition governments are rather the rule than the exception. In coalition talks, parties negotiate about policies and offices. In contrast to vote-maximization, policy- and office-motivation can be both intrinsic and instrumental (Strøm and Müller 1999). In the case of intrinsic motivation, policies or offices are valuable goods in themselves. In the case of instrumental motivation, policies or offices are only the means to an end. In the present study, we do not look at the motivations behind policy and office goals. We are only interested in the time that the actors need to agree upon a compromise to form a coalition and argue that policy preferences are relevant and need to be negotiated.

Which factors help to decrease the negotiation process over policies and hence the duration of the negotiation process itself? We start from the rich literature on coalition formation. Negotiations require trust and information between actors (Kennan and Wilson 1993). Trust and information are built through social interactions (Browne and Rice 1979). If these elements are missing, then interactions should be harder and hence, the duration longer. This argument is coined most prominently in Franklin and Mackie’s (1983: 277) contribution:

[C]oalition formation would be regarded as a continuing process over very long time periods in which parties build up experience of governing in different combinations with each other. This form of shared experience might even come to transcend ideological differences, as summed up so succinctly in the proverbial phrase ‘better the devil you know than the devil you don’t’.

The authors identified the concepts of inertia—defined as current government experience—and familiarity—defined as government experience in the past—as the missing variables in theories of coalition formation based on size or ideology. Their work tells us that government formation processes, as well as the parties involved, have a history and this history plays an important role in the present. Similar to control mechanisms that parties employ to ensure smooth governance once in office (Müller and Meyer 2010), previous government experience gives them a good evaluation basis on whether coalition governance will work. Parties already know whether policy compromises are feasible or whether each partner is able to enact its core policies without interference from the other. The mode of governance is known and even if certain areas have not been free of conflicts, again, they are at least known. The incumbency advantage was found to be relevant in coalition formation research (Warwick 1996; Martin and Stevenson 2001, 2010; Bäck and Dumont 2007).

A related argument can be found in the literature on government formation duration processes that is of core interest in the present study. Scholars have argued that the level of uncertainty increases the length of the negotiation process. Although measured differently in different studies, the authors acknowledged that uncertainty positively affects the time needed to build a new cabinet (Diermeier and Van Roozendaal 1998; Martin and Vanberg 2003; De Winter and Dumont 2008; Golder 2010). More recently, analysing more than 300 bargaining attempts in Western and Central Eastern European democracies, Ecker and Meyer (2020) found that previous government experience decreases negotiation time (also see Ecker and Meyer 2015). They operationalized the concept of uncertainty based on the familiarity of the party composition and between party elites.

Having established sub-national actors’ behaviour and their bargaining situation, we can now think of the potential influence of the national level in these situations. Again, we find our point of departure in studies analysing the partisan composition of coalitions. Downs (1998: 55) already noted that ‘subnational parties negotiate simultaneously with their local rivals and with their own central party leaders’ (emphasis in the original) and we have ample work that supports this claim (Swenden 2002; Debus 2008; Däubler and Debus 2009; Bäck et al., 2013; Ştefuriuc 2013). For example, Däubler and Debus (2009) analysed coalition building in German states and showed a preference for congruent coalitions, i.e. sub-national coalitions that include the same parties as the current national coalition. This finding was corroborated by a comparative study analysing coalition formation at the regional level in eight European countries (Bäck et al., 2013). Especially cross-cutting coalitions—e.g. coalitions that bring together a national government and opposition party—are less likely to form. Most recently, Martínez-Cantó and Bergmann (2020) provided empirical evidence that congruent governments are also more likely to serve until the regular end of their terms.

Based on previous research, we first theorize that regional co-governance experience increases trust in the future policy pay-offs if joining a mutual coalition but also in productive and reliable mutual cooperation in times of conflict based on increased inter-personal trust. Thus, we assume that recent co-governance increases the likelihood that partners choose each other again to form a mutual government and that the selection process is speed up because parties are not in dire need of gathering additional information in a long series of bargaining offers, rejections, and counteroffers to uncover information about their opposite (see Kennan and Wilson 1993). That is why, the partners’ previous mutual history also leads to shorter bargaining and hence shorter coalition negotiations in the formation process.

However, if previous contact between the sub-national actors is missing due to a lack of co-governance in the past, then the national level might help to provide this missing link. Consequently, we further argue that previous cooperation of parties at the national level might help to decrease uncertainty among the actors and thus to decrease negotiation time. If party elites have been or are successfully cooperating on the national level, regional party elites should have greater trust and certainty in a mutual coalition and increased knowledge about their opposite, also on the regional level, compared to parties without any recent co-governance experience.

Differentiating between these distinct situations of co-governing experience, our hypotheses read:

Hypothesis 1: Inertia decreases the duration of the coalition formation process. If parties are currently governing together at the regional level (H1a) or at the national level (H1b) or at both levels (H1c) then the coalition formation process is faster compared to situations without co-governing experiences.

Hypothesis 2: Familiarity decreases the duration of the coalition formation process. The longer the parties have governed together at the regional level (H2a) or at the national level (H2b) in the past, the faster the coalition formation process.

3. Data on cabinet formation processes in the German Bundesländer

To answer our research question, we collected data on 208 regional cabinet formation processes in the 16 German Bundesländer since 1949, of which there are 139 coalition formations. Importantly, we only include post-election government formation processes and do not take into account replacements during the legislative term. As such, the levels of uncertainty are very high compared to government formation processes during the legislative term, thus familiarity and inertia should be of utmost importance. The data on election dates, the partisan composition, and the dates of investiture votes of regional and national governments in Germany have been coded based on official election results and cabinet information on official federal or state government websites.

The focus on the German states gives us the possibility to study structural attributes in the government formation processes. While we see sufficient variation in the party strength over the electoral periods and across the states, the case selection following the logic of a most similar system design allows us to hold important institutional settings as well as party system factors constant. With few exceptions (such as the CSU in Bavaria or the SSW in Schleswig-Holstein), the competing parties on the regional level are the same and the political institutions influencing government formation processes, e.g. investiture votes, vary to a very low degree between the states, especially in comparison to cross-country studies.

Moreover, Germany can be seen as a highly interesting case to investigate co-governance and the interplay between the national government and regional coalition formation processes. This is due to the fact that the bargaining environment in such a setup in a multilevel country such as Germany can be considered to be both, uncertain and complex (Diermeier and van Roozendaal, 1998; Martin and Vanberg 2003). The rationale behind this is that the German states have high authority on the interior level, but at the same time have strong possibilities to exert ‘bottom-up’ influence on national politics (Bäck et al., 2013: 374). This is reflected by the high ranking of the German states on both dimensions of the regional authority index (Marks et al., 2008): the degree of regional autonomy (self-rule) and the regions’ ability to exert influence on national politics (shared rule).

Thus, on the one hand, the impact of the federal government on regional politics is institutionally constrained by German federalism, which is, according to Lijphart (2012: 178), one of the strongest federal and decentralized systems among established parliamentary democracies in the world. It is protected by the German constitution through an ‘eternity clause’ which makes it legally impossible to abolish the states’ regional autonomy. Consequently, the tax share of the German national government is one of the lowest in international comparison with only about 50% (Jahn 2013: 79) which is another indicator of the strong regional autonomy in Germany. Accordingly, the national level has a strong interest in being able to influence the policies for which the competencies lie at the regional level, such as education. Hence, the national parties aim to influence the formation of regional governments that overlap with their own preferences.

On the other hand, national parties have strong incentives to try to impact regional government formation processes. For example, previous research has shown that regional coalition participation influences the voters’ perception of parties even on the national level (Hjermitslev et al., 2024). Moreover, national parties are motivated to interfere with regional coalition formation due to the powerful political position of the state governments in the national policy-making process. The reason for their strong position regarding the shared rule is that the composition of the state governments directly affects the composition of the Bundesrat, Germany’s second chamber2 on the national level with strong veto potential in the federal law-making process (Tsebelis 2002: 80). The Bundesrat is the institution that ensures the representation of the states on the national level and all legislative policy proposals have to be presented to the Bundesrat before they can be passed in the German parliament, the Bundestag. For all policy proposals that considerably affect the competences and/or finances of the states as well as for constitutional changes, the Bundesrat has an absolute veto power, for all other policies, the Bundesrat has a suspensive veto that can only be overridden by an absolute majority in the Bundestag. Before substantial federalism reforms in 2006, the Bundesrat had an absolute veto power on over 50% of all policy proposals, this number dropped to about 38% in 2013–17 (Bundesrat statistics 2017). As the members of the Bundesrat are delegates of the state governments, every change in state government composition leads to changes in the party composition of the Bundesrat, thus leading to potential blocking majorities. Prominently, former chancellor Gerhard Schröder had continuous political struggles with the opposing Bundesrat majority in the early 2000s. In May 2005, the electoral loss of the last red–green-led state government in North-Rhine Westphalia caused Schröder to intentionally lose a confidence vote in parliament in order to be able to call early elections.

Hence, following the arguments of inertia and familiarity, the position within the parties is known and does not per se prolong the duration processes, but the national level has an incentive to care about the regional level.

3.1 Dependent variable: Coalition formation duration

We measure bargaining duration as the time between the election date and the official start date of the first post-electoral government, i.e. the investiture vote of the head of government. Thus, the variable Coalition formation duration tells us how long it took to find a legislative majority in favour of a new government, irrespective of the number of bargaining attempts during that time. Data availability prohibits us from registering unsuccessful bargaining attempts. However, as we are interested in the duration of finding a newly invested government, this measurement fits our research goal. Furthermore, since we are examining the effect of co-governance experience, the multivariate analyses in the subsequent section are based solely on government formation processes that resulted in a coalition between at least two parties (N = 139). We compare our results with the full sample and further sub-samples in the Supplementary Appendix.3

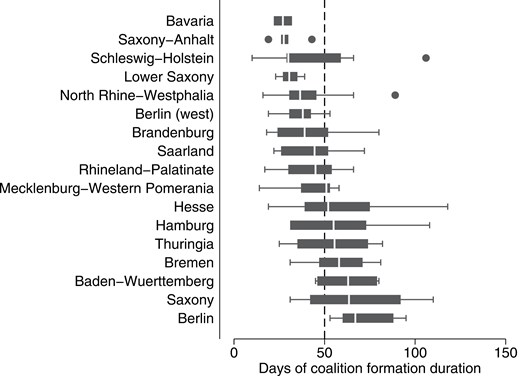

Figure 1 presents box plots of the duration to form a cabinet across states ranging from the shortest to the longest duration, including all coalition formation processes.4 The box plots show the median formation duration (white line within the box), the first and third quartiles (the lower and upper ends of the box), the spread of cases (the whiskers including all cases that are within 1.5 times the interquartile range above the upper/below the lower quartiles), and the outliers (circles). The mean coalition formation duration across the states is 50 days (SD = 30) as indicated by the vertical line.

Box plots of coalition formation duration across states

Note: The cabinet Börner III (Hesse) has been excluded from the graph for displaying purposes.

The box plots show significant variation in the cabinet formation processes among the 16 (or 175) states. While Bavaria has the shortest average duration time with 27 days, in unified Berlin government formation takes the longest with 73 days on average.6 This can largely be explained by the strong dominance of the CSU in Bavaria which only twice could not win an absolute majority of legislative seats since the 1960s but has always had the position of the prime minister, while there have been very volatile coalition formation processes in Berlin where five different party compositions have ruled in coalitions since only 1990. Thus, our data are closely aligned with those of comparable studies (e.g. Bäck et al., 2024a), despite slight differences in observations and time frames. Notably, even the variation in duration by state is similarly comparable.

Furthermore, there are some important outliers in the data. The longest cabinet formation process was in 1983/1984 when it took 283 days to form the third cabinet of Holger Börner (SPD) in Hesse. After the 1982 elections to the Hessian parliament ended in a political gridlock, the 1983 snap elections did not lead to clear majorities for the parties either (also called ‘Hessian circumstances’). Hence, after long party negotiations, an SPD-led minority cabinet was formed with the explicit support of the Greens who later joined the coalition in 1985, resulting in the first red–green coalition in Germany. Other outliers include the 118-day formation process in Hesse in 2014 which led to the only second ever, but first in a Flächenland, CDU–Greens coalition, and the 106-day formation process after the elections in Schleswig-Holstein in 1962 after which SPD and FDP tried to form a minority cabinet with the support of the ethno-regional deputy for the Danish and Frisian minorities. However, the negotiations failed and eventually a CDU–FDP coalition was formed in 1963 under Helmut Lemke. This anecdotal evidence underlines the discussion above that the co-governing experience between the parties seems to play an important role in the duration of coalition formation processes.

Interestingly, Supplementary Appendix Figures A1 and A2 do not show clear trends in the cabinet and coalition formation duration over the past decades before 2000. Only in the last two decades, there seems to be an increase in the time it takes for parties to form a government on the state level. This can partly be explained by the upcoming of the Linke even in West Germany and the AfD which led to more difficult government formations (Bäck et al., 2024b).

3.2 Independent variables

Our analyses build on the argument of co-governing experience at the different political levels that we measure based on the concepts of inertia and familiarity (Franklin and Mackie 1983; Martin and Stevenson 2010). Thus, our first variable of interest is Inertia. The variable inertia differentiates between cases Without inertia (0), Regional inertia (1), National inertia (2), and Inertia on both levels (3). Note that, in contrast to familiarity, inertia registers only current co-governance between parties. Hence, only if the negotiating parties at the regional level are the same in the preceding regional government or are currently in power at the national level, then we coded these situations as regional inertia and national inertia, respectively.7 The majority of observations fall into the categories (0) without inertia, N = 71 or 51%, and (1) regional inertia, N = 36 or 26%. For 17 government formation processes (or 12% of our observations), we identify (2) national inertia, and for 15 cases (or 11%), we code inertia on both levels (3). Supplementary Appendix Figure A4 shows the distribution of the variable inertia.

Familiarity reflects the time in government that two parties have spent together in the past, and this common history is expected to facilitate current cooperation. A common history means that the actors involved know their counterparts, know which policy compromises are feasible, and know how to communicate with each other.

Clearly, this argument only holds if the present actors are aware of their common history. The longer it is in the past, the less likely it is that it still matters in current politics. Identifying the appropriate time frame is thus key in operationalizing familiarity. Martin and Stevenson (2010: 510), who examined the effect of familiarity on coalition formation in Western Europe, argued that the average tenure time of national party leaders is a good proxy of a relevant past. Therefore, they discounted co-governing experience that was more than 8 years in the past. Examining state-level politics, we decided to take a similar approach and operationalize familiarity as the share of co-governance experience over the past 7 years. In our sample, this is the average time German state governors—and thus the key figures in state politics—remained in office. For example, in Brandenburg, the cabinet Platzeck II (2004–9) between the SPD and the CDU brought together two parties that had already governed together in the previous government. Regional familiarity reflects the share of these co-governing days over a period of 7 years (1,804/2,555 = 0.71).

Furthermore, we need to account for situations, in which three or four parties negotiate a coalition and only two of them have common experiences (at the regional or national level).8 Clearly, familiarity is present, albeit not to an equal strength compared to situations in which all actors share a common history. Thus, in cases where a third actor is involved, we calculate the share of co-governing days over the past 7 years and weigh the result with the share of ministerial posts of the rejoining parties in the current coalition. To give another example, in Bremen, the cabinet Bovenschulte (since 2019) brought together the SPD, the Greens, and the Left. In the past 7 years, only the SPD and the Greens were governing together. Thus, regional familiarity reflects the share of co-governing days between the SPD and the Greens over a period of 7 years weighted by the share of ministerial posts of the SPD and the Greens (7 out of 9) in the current coalition government (2,555/2,555*0.79 = 0.79).

Finally, our data set includes two variables of familiarity: one that represents familiarity at the national level (National familiarity) and one that represents familiarity at the regional level (Regional familiarity). The variables range from ‘0’, which denotes no co-governing experience over the past 7 years, to ‘1’, which denotes that the same parties were represented in the governments over the past 7 years.

Though our case selection strategy holds many confounding factors such as institutional settings and party types constant, we add some additional variables to our models to control for other systemic factors (Ecker and Meyer, 2020; Bäck et al., 2024b). Martin and Vanberg (2003) found that the larger ideological distance between the involved parties increases the duration of coalition bargaining. Thus, we include a variable for the ideological divisiveness of the cabinet parties. It is measured as the distance between the left-most and right-most party in the cabinet based on the national party manifestos. We gathered the data from the national party manifesto published closest to the regional elections and used the data based on the rile scores provided by the MARPOR project. The rationale behind using data from the national level is that data for the regional parties is only available for the time after 1990 (Bräuninger et al., 2019, 2020) which would mean a considerable loss of data for our analysis. Furthermore, we follow Golder (2010), Ecker and Meyer (2015) as well as Bäck et al., (2024b) and include the effective number of legislative parties since the higher the number of relevant parties, the more complicated the bargaining environment and thus the longer negotiations might take. The data for the regional level have been computed by the authors based on regional election reports.

Previous research has found that institutional aspects play an important role with regard to government formation duration (see, e.g. Ecker and Meyer 2015). In order to account for investiture vote requirements, we have included a variable that is ‘1’ if a state requires an absolute majority for the government to be voted into office and ‘0’ otherwise. In order to check if there are differences between East and West German states, we include a dummy variable that is ‘1’ if the state is in Eastern Germany, and in order to control for time effects, we also include decade dummies. In the Supplementary Appendix, we further show models including a binary variable if the state’s prime minister remained the same and one model where we control for the length of coalition agreements since longer coalition agreements may lead to longer negotiations. The data on coalition agreements have been collected from the Political Documents Archive (Benoit et al., 2009; Gross and Debus 2018). However, we have only data for coalition agreements since the 1990s which reduces our sample drastically to only 83 observations. Furthermore, we replicate the models using the data provided by Bäck et al., (2024a). Finally, we check whether the results hold once we control for the effect of regional coalition formation on the majority in the Bundesrat.

4. Analyses

In this article, we analyse coalition formation processes. Concretely, we are interested in the time it takes until an event—in this case, government coalition formation—happens. Accordingly, we rely on event history analysis to test our hypotheses (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004). A hazard ratio above 1 indicates a higher ‘risk’ of coalition formation and therefore denotes a shorter coalition formation process.9

However, before we move on to the interpretation of the results, two modelling choices need to be mentioned. First, we rely on Cox proportional hazards models to test our hypotheses. While these models are generally rather flexible, they make one important assumption: the proportional hazards assumption (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004). One of our independent variables violates this assumption: the effective number of parliamentary parties variable. In order to account for this, we follow the advice given by Box-Steffensmeier and Zorn (2001) and interact this variable with the natural logarithm of time. Second, the previous section has demonstrated that there are substantial differences between government formation processes in the German states. This might result in formation processes being more similar to each other within states compared to formation processes between states. In order to account for this, we estimate shared frailty models.

The results of our analysis can be found in Table 1. Our first main explanatory variable is the current co-governing experience between the negotiating parties, i.e. inertia. As mentioned previously, the variable has four different categories: without inertia, regional inertia, national inertia, and inertia on both levels. In Table 1 the reference category is without inertia.

| DV: Coalition formation duration . | Model 1 . |

|---|---|

| Main explanatory variables | |

| Without inertia | Reference category |

| National inertia | 3.161*** (1.085) |

| Regional inertia | 4.145*** (1.548) |

| Inertia on both levels | 3.727** (1.921) |

| National familiarity | 1.760** (0.525) |

| Regional familiarity | 0.192*** (0.089) |

| Control variables | |

| Ideological distance (nat.) | 0.967*** (0.008) |

| Eff. number of parl. parties | 0.026*** (0.035) |

| Absolute majority | 0.434** (0.176) |

| East German state | 1.127 (0.511) |

| Decade dummies | ✔ |

| Time-varying co-variates | |

| ENPP × ln(t) | 2.279** (0.792) |

| Observations | 139 |

| Failures | 139 |

| Log-likelihood | −516.580 |

| DV: Coalition formation duration . | Model 1 . |

|---|---|

| Main explanatory variables | |

| Without inertia | Reference category |

| National inertia | 3.161*** (1.085) |

| Regional inertia | 4.145*** (1.548) |

| Inertia on both levels | 3.727** (1.921) |

| National familiarity | 1.760** (0.525) |

| Regional familiarity | 0.192*** (0.089) |

| Control variables | |

| Ideological distance (nat.) | 0.967*** (0.008) |

| Eff. number of parl. parties | 0.026*** (0.035) |

| Absolute majority | 0.434** (0.176) |

| East German state | 1.127 (0.511) |

| Decade dummies | ✔ |

| Time-varying co-variates | |

| ENPP × ln(t) | 2.279** (0.792) |

| Observations | 139 |

| Failures | 139 |

| Log-likelihood | −516.580 |

Notes: Model 1 includes all coalitions, irrespective of their majority status. Standard errors in parentheses; *** P < .01, ** P < .05, * P < .1.

| DV: Coalition formation duration . | Model 1 . |

|---|---|

| Main explanatory variables | |

| Without inertia | Reference category |

| National inertia | 3.161*** (1.085) |

| Regional inertia | 4.145*** (1.548) |

| Inertia on both levels | 3.727** (1.921) |

| National familiarity | 1.760** (0.525) |

| Regional familiarity | 0.192*** (0.089) |

| Control variables | |

| Ideological distance (nat.) | 0.967*** (0.008) |

| Eff. number of parl. parties | 0.026*** (0.035) |

| Absolute majority | 0.434** (0.176) |

| East German state | 1.127 (0.511) |

| Decade dummies | ✔ |

| Time-varying co-variates | |

| ENPP × ln(t) | 2.279** (0.792) |

| Observations | 139 |

| Failures | 139 |

| Log-likelihood | −516.580 |

| DV: Coalition formation duration . | Model 1 . |

|---|---|

| Main explanatory variables | |

| Without inertia | Reference category |

| National inertia | 3.161*** (1.085) |

| Regional inertia | 4.145*** (1.548) |

| Inertia on both levels | 3.727** (1.921) |

| National familiarity | 1.760** (0.525) |

| Regional familiarity | 0.192*** (0.089) |

| Control variables | |

| Ideological distance (nat.) | 0.967*** (0.008) |

| Eff. number of parl. parties | 0.026*** (0.035) |

| Absolute majority | 0.434** (0.176) |

| East German state | 1.127 (0.511) |

| Decade dummies | ✔ |

| Time-varying co-variates | |

| ENPP × ln(t) | 2.279** (0.792) |

| Observations | 139 |

| Failures | 139 |

| Log-likelihood | −516.580 |

Notes: Model 1 includes all coalitions, irrespective of their majority status. Standard errors in parentheses; *** P < .01, ** P < .05, * P < .1.

Hypothesis 1a expected that regional inertia decreases the duration of government formation. The figures in Table 1 corroborate the hypothesis. The hazard ratios of having regional inertia are above 1 in our model and significant. This means that the ‘risk’ of having successful coalition negotiations when the same parties are currently in government together at the regional level is substantially higher compared to when parties are not cooperating at the moment.

Hypothesis 1b is also supported by the data. The hazard ratio of having national inertia is above 1 and significant. Coalition negotiations between parties that are already in government at the national level are shorter compared to coalition negotiations between parties that are not already together in the national government.

Finally, we also find support for hypothesis 1c. For the category inertia at both levels, the hazard ratio is also above 1 and statistically significant. This means that if the parties involved in the negotiations at the regional level are already in government together at the regional and national levels, then these negotiations are considerably shorter.

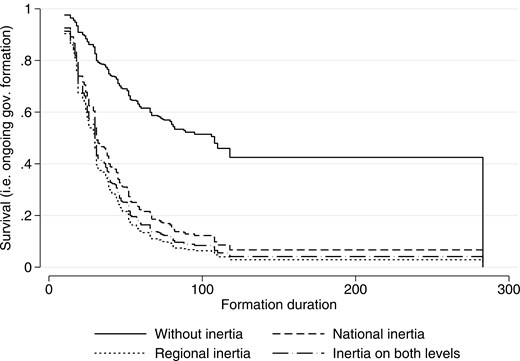

Figure 2 shows the survival rates for the government formation processes in our dataset and graphically displays our results. Survival curves show how many of the cases still have not yet experienced a failure (i.e. successful government formation) at a certain point in time. The figure clearly shows that there is a substantial difference between formation processes where there is no inertia and formation processes with regional and national experiences. For example, 100 days after the election, around 51% of the negotiating processes are still ongoing when inertia is not present. Yet, in cases where some form of inertia is present, on average only around 8% of the cases are unfinished.

We now turn to our second concept of interest, regional and national familiarity. Regional familiarity has a negative influence on the risk of successful government formation. This means that, as regional familiarity increases, the duration of coalition formation increases. This finding runs counter to our theoretical expectations formulated in hypothesis 2a. Recall that we are interested in the duration until a new coalition government is ready to take over governmental responsibilities. Unsuccessful bargaining attempts that might have happened in between remain in a black box. Since the regional level in Germany is often used as a testing ground for new coalition types (Gross and Niendorf 2017), the result might be explained by unsuccessful bargaining attempts with new partners that then failed and finally led to a coalition among familiar partners. We will come back to this point in the concluding section.

The negative finding might be a hint that new coalitions have been yet unsuccessfully negotiated, thus prolonging the formation process. Maybe not the same partner is selected in order to ‘test the ground’ regional level. Unsuccessful attempts are not visible in our design. Future studies could look at formation attempts to disentangle the effects more clearly. However, since we do find the expected positive effect for regional inertia, the negative effect of regional familiarity is likely to be rather a long-term effect. This could, therefore, be potentially explained by changes in the party elites over time or by the overall development of longer coalition formation durations since 2000, which covers a substantial share of our sample (see Supplementary Appendix Figures A1 and A2). Also, regional familiarity is significantly correlated with the length of coalition agreements10 (see Supplementary Appendix Figure A6). Coalition agreements became longer over time (see Supplementary Appendix Figure A7) and writing long agreements takes more time which leads to longer coalition formation processes (see Supplementary Appendix Figure A8).

National familiarity, on the other hand, increases the risk of successful government formation. Thus, if parties are familiar with each other from the national coalition government, the duration of coalition formation on the state level decreases. This is in line with our theoretical expectations formulated in H2b.

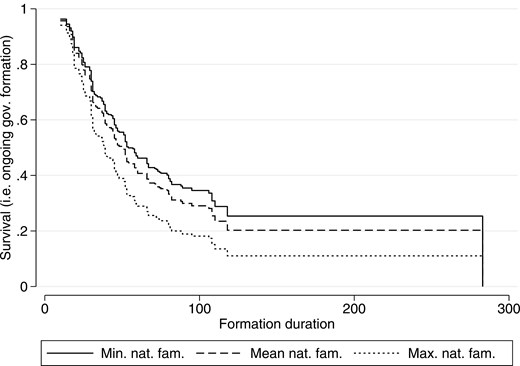

Figure 3 again shows the survival rates, this time depending on the level of familiarity at the national level. We have calculated survival rates for the minimum (0), the mean (0.3), and the maximum (1) of familiarity. For instance, after 100 days of cabinet formation talks, the survival rate of cabinets with the maximum of national familiarity is at around 18%, whereas it is at roughly 29% for the mean value of national familiarity and at around 34% for the minimal value of national familiarity. Hence, the graph again shows that familiarity at the national level importantly influences the chances of successful government formation.

Finally, we ran several different robustness checks in order to check the stability of our findings. First, we ran two separate analyses for the two different concepts of inertia and familiarity. Running the variables separately gives us the assurance that the variables do not affect each other (see Supplementary Appendix Table A2). While the significance levels decrease, the results still show the expected signs and are largely robust.

Second, we alter the definition of relevant cases (see Supplementary Appendix Table A3). Model 4 is based on all cases that are included in the main Model 1, but adds all cases in which a single-party minority government came into office. Thus, this extends our sample in order to check whether the results remain stable including these minority situations that ultimately did not end up in a coalition government. Model 5, on the other hand, restricts our cases from the main Model 1 by excluding all cases in which the largest party has an absolute majority (i.e. surplus coalitions). Thus, we can see whether this restricted sample based on situations where a coalition partner is needed to form a majority government yields to the same results. Model 6, finally, includes all governments that were formed after an election during our research period. This means that we add to our cases from the main Model 1 all single-party governments regarding their majority status. Looking at the results of the various models we see that the findings are stable (with the only exception being the effect of inertia at both levels which is insignificant in Model 6).

Third, we alter the specification of our models (see Supplementary Appendix Tables A4 and A7). Model 7 shows our main model, but excludes the coalition formation process of Börner III (Hesse). We decided to run a separate mode that excludes this cabinet because it is an extreme outlier with a formation duration of 283 days (compared to 50 days average formation duration). Model 8 controls whether the prime minister remained the same before and after the election. This tests whether familiarity and inertia go beyond the position of the prime minister. Model 9 controls for the length of coalition agreements in order to see whether writing longer coalition agreements is related to the duration process. The results are robust, except for Model 9. However, this model reduces the sample drastically to only 83 observations and does not reduce our confidence in the presented results since the coefficients show in the expected direction and the P-values are only marginally above the traditional level of significance (P = .15). Model 14, finally, includes two dummy variables checking for cases that change Bundesrat majorities positively or negatively in the eyes of the current national government. The results of our models remain robust, the newly created variables do not have an effect.

In addition to these robustness checks, we replicate the two-stage model with data provided by Bäck et al., (2024a). We added our main explanatory variables to this data set. The results are presented in Supplementary Appendix Table A6. Even though the sample is restricted to the time frame since 1990, our findings are largely robust, with the exception of the duration-decreasing effect of national inertia and national familiarity. We argue that one potential explanation of these null findings might be the more diverse party composition of coalitions at the regional level since the 1990s, which is likely to be linked to a comparably low number of cases with national inertia—only 8% in that sample—and a significantly lower mean of national familiarity (only 0.2). However, the models show that inertia is an important driver in both stages, which underlines our main argument that inertia affects coalition formation in both stages: the selection process and the bargaining duration.

5. Conclusion

How can the large variation in the duration of regional coalition formation processes be explained? What role does co-governing experience at different political levels play for the time parties need to form a winning coalition? This study set out to answer these questions by examining regional coalition formations in the federal system of Germany and parties’ co-governing experience both at the regional and national levels.

Building on Franklin and Mackie’s (1983) work on national coalition building, we have hypothesized that regional government formation processes should be faster if parties are currently in government with each other at the regional and/or the national level, i.e. have inertia. Furthermore, we expected the same effect the longer parties have previously governed with each other at the regional or national level, i.e. have familiarity. Inertia and familiarity—through increasing trust and information among the involved actors—increase the probability that the duration of the process decreases. This is in line with the words of Kennan and Wilson (1993: 46) who argued that ‘bargaining is substantially a process of communication necessitated by initial differences in information known to the parties separately’.

We generated a new dataset of regional government formation from the 16 German states since 1949 and tested our hypotheses with the help of event history analysis. The results support most of our hypotheses: parties are commonly faster in forming a coalition if they currently cooperate at the national and/or regional level or have a national history of governing together. Yet, in contrast to our expectations, regional familiarity does not speed up the negotiations. Having regional familiarity is associated with longer processes. Examining these cases in a qualitative manner does not show a systematic picture. We take from this result that these cases were potentially influenced by unsuccessful bargaining attempts at the regional level. Data on unsuccessful bargaining attempts at the regional level do not and we were unable to find reliable evidence on previous unsuccessful bargaining attempts for our research period. Our results contribute to understanding the duration until a new government is formed. We hope that future studies that are based on recent regional government formation processes in a cross-country setting will disentangle this finding further. Additionally, it would be interesting to test whether inertia and familiarity still have an influence when uncertainty is lower (i.e. when new governments form as a replacement and not after an election).

Turning back to our two extreme examples from the beginning of the article, it fits that the parties in the fastest coalition formation process in our dataset—the 10 days which led to the formation of the CDU/FDP coalition in Schleswig-Holstein in 1967—had regional inertia (and also regional and national familiarity). In contrast, the longest (non-outlier) coalition formation process in our dataset—the 118 days which led to the CDU/Greens coalition in Hesse under Volker Bouffier in 2014—had none: no regional and/or national inertia (and no regional or national familiarity). A high level of uncertainty led to a substantially longer coalition formation period in that case.

Quite interestingly, the effects are more substantial and robust for national co-governing experience than for regional ones. This finding underlines that it is highly important to analyse regional government formation in the light of national politics in strongly federalized systems such as Germany. Hence, the national level does play an important role in regional bargaining processes. If cross-cutting coalitions—e.g. coalitions that include a national government and opposition party (Däubler and Debus 2009)—are about to form, then national party branches might slow the process and bring alternative proposals to the lower level. National parties have an incentive to see congruent coalitions installed at the regional level since these types of coalitions might facilitate policy-making across coalitions (Bolleyer 2006). This might be especially relevant in our research on the German case, since the Bundesrat is a veto player in national policy-making (König 2001).

A natural progression of this work is to analyse the effect of inertia and familiarity in other multilevel countries. We would expect to see similar results in similarly federalist European countries such as Belgium or Spain. Adding more cases would further allow us to examine the connection between the specific structure of a federalist country on the one hand, and the effect of multilevel co-governing experience, on the other. Germany scores high on both the self-rule and the shared rule indicators that comprise the regional authority index (Hooghe et al., 2016; Shair-Rosenfield et al., 2021). Italy, for example, scores similarly high on the self-rule indicator, but much lower on the shared rule one. National party branches might have less incentive to influence regional government formation and the regional co-governing experience might thus be of greater influence in such cases. Austria, to bring in one final example, scores lower on self-rule and comparatively higher on shared rule. In such federalist settings, the national level might exert a similar influence as in the present German study.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at Parliamentary Affairs online.

Funding

Katrin Praprotnik conducted this research under the auspices of the Austrian Democracy Lab (ADL), a cooperation with Forum Morgen. No additional funding.

References

Footnotes

Flächenland stands as the opposite to the general more liberal Stadtstaaten (city-states or independent states) Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg. The first-ever CDU-Green coalition was formed in liberal city-state Hamburg in 2008 and held for 2 years.

In strictly legal terms, the Bundesrat is not a second chamber of the national parliament but rather a legal organ ‘sui generis’. However, in terms of the policy-making process, it functions similarly to second chambers in other countries.

Supplementary Appendix Figure A3 shows the distribution for the full sample.

Supplementary Appendix Table A1 shows summary statistics for our dependent and independent variables.

Due to the substantial variation between West Berlin and unified Berlin, we treat these as two different states in our statistical analyses.

The average coalition formation duration is the longest in Hesse (75 days), however, this result is driven by one outlier as discussed below.

We argue that simultaneous national negotiation talks are not likely to denote co-governing experience relevant to the regional level.

We do not, on the other hand, weigh in situations where two parties are negotiating and these two parties plus a third actor have been in office in the past.

Note that our interest lies in the overall duration of coalition formation, not in individual formation attempts. Our argument encompasses the entire process, suggesting that the impact of co-governance is not isolated but affects the process as a whole. Therefore, in our primary analysis, we do not adopt a two-stage modelling approach for government formation—a method employed by Bäck et al., (2024a) and Ecker and Meyer (2020). However, as a robustness check, we incorporated our data into the dataset used by Bäck et al., (2024a) and re-analysed it using a two-stage process. This approach yielded results that were largely similar (see Supplementary Appendix Table A6).

Running negative binomial regression results with the length of coalition agreements as the dependent variable, we find a highly significant effect (P-value < .01) of regional familiarity despite controlling for ideological party distances and time effects (see Supplementary Appendix Table A5).