-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paul Anderson, Coree Brown Swan, An unstable Union? The Conservative Party, the British Political Tradition, and devolution in Scotland and Wales 2010–23, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 77, Issue 4, October 2024, Pages 790–815, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsae020

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

While devolution in Scotland and Wales is often established as the settled will, it has been built on unsettled ground, lacking a robust system of intergovernmental relations, and sitting increasingly at odds with the central principle of parliamentary sovereignty. Examining successive UK Conservative-led governments, we evaluate devolution in Scotland and Wales through the lens of the Asymmetric Power Model and the British Political Tradition, documenting changes in the position of successive Conservative governments, from the more plurinationally sensitive respect agenda of David Cameron to the more assertive and intrusive Unionism advanced under those in post after 2016, notably Theresa May and Boris Johnson.

1. Introduction

Addressing the Labour Party Conference in 1999, the then Prime Minister Tony Blair proclaimed, ‘Delivering our promise of a Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly has strengthened the UK not weakened it’ (Blair 1999). Twenty-five years on, the Union remains intact, but the notion of a stable, long-term political settlement has been increasingly undermined by both centripetal and centrifugal forces. The steady rise of secessionism in Scotland and the growth of independence-curious voters in Wales are clear illustrations of the existential threat posed to the UK by centrifugal forces (Hayward 2022; Anderson 2024). Likewise, the centralizing tendencies of successive Conservative governments in Westminster, the interference of the UK government in devolved affairs, and the adoption of a more assertive approach to territorial management illuminate the centripetal pressures that equally jeopardize the continuation of the political Union (Andrews 2021; Hayton 2021; McEwen 2022).

As highlighted by Marsh et al. (2024) in this special issue, the Asymmetric Power Model (APM), as much the original as the updated version, illuminates the enduring strength of the British Political Tradition (BPT), reflected in a top-down understanding of democracy, a hierarchical, power-hoarding form of governance, and a prevailing notion that Westminster and Whitehall know best. Developed in the very early years of devolution, the APM afforded little attention to the transfer of power from Westminster to Scotland and Wales. The devolved settlements, nonetheless, while often framed in opposition to the politics of Westminster, embodied and perpetuated some of the principal characteristics of the APM, and more specifically the BPT.

Capturing the period 2010–23, when the Conservatives formed the main party of government in Westminster, whether in coalition, or as majority or minority governments, this article examines the influence of the BPT on the Party’s strategies towards devolution in Scotland and Wales. During this period, the UK was led by five Prime Ministers (David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, and Rishi Sunak) each with their own territorial strategies informed by different political contexts in which issues relating to devolution increased in prominence and at times dominated political agendas. Much of the unionist narrative during this period was concentrated on the more immediate threat of Scottish independence, and Wales often received less attention, more broadly amalgamated into a discourse of the Union as a family of nations. Focusing on three ‘constitutional moments’—the Scottish independence referendum and subsequent debates on devolution across the UK; the vote to leave the EU and the protracted negotiations that followed; and the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic—we highlight the enduring legacy of the BPT particularly during moments of crisis. Under the Conservatives, the devolution of (further) powers to Scotland and Wales followed a similar pattern to Blair’s Labour governments in seeking to preserve the power of the central state, while disrupting crises such as Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the centralizing tendencies of the BPT, culminating in increasingly assertive territorial strategies and a deterioration of devolved-UK government relations. In analysing these three constitutional moments, we draw on contemporaneous speeches, parliamentary debates, and policy documents, as well as news articles that capture the political dynamics during the periods in question.

The contribution of this paper is 2-fold. First, building on the revised model of the APM and recent research on devolution, unionism, and the BPT (Richards and Smith 2016; Richards et al 2019; Sandford 2023), we chart the influence of the BPT on territorial politics and its particular emphasis on the notion that Westminster and Whitehall know best as manifested in the period from 2010 onward. We highlight how the BPT informs UK Government thinking vis-à-vis territorial politics over this period and argue that the continued dominance of the BPT and its associated notions of centralized governance and the primacy of Westminster risk further undermining an already fragile Union. Second, we contribute to the literature on the UK Conservative Party and territorial politics by providing a holistic and in-depth analysis of the UK Conservatives’ strategies towards devolution in Scotland and Wales across a thirteen-year period. Our findings document the changing nature of devolution policy of successive Conservative governments, from the more plurinationally sensitive respect agenda of David Cameron to the more assertive and intrusive Unionism advanced under those in post after 2016, notably Theresa May and Boris Johnson.

This article is structured as follows: Section two provides an overview of the APM, with a specific focus on the BPT, and explores how it informed the introduction and early experiences of devolution at the turn of the twentieth century. Section three presents the empirical analysis, which details and examines the ways in which the Conservatives’ strategies towards devolution across the UK since 2010 are informed by the principal characteristics of the APM. The final section reflects on the future trajectory of constitutional policy.

2. The Asymmetric Power Model, the British Political Tradition and Devolution

Writing in the early 2000s, Bogdanor (2001: 1) described the establishment of devolved executives and legislatures in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland as ‘the most radical change this country has seen since the Great Reform Act of 1832’. Twenty-five years later, devolution has transformed the governance of the political systems in Scotland and Wales, but its impact on Westminster and Whitehall has been markedly less pronounced. As such, the UK state is predominantly understood ‘as unitary at the centre, but differentiated at the periphery’ (Keating, 2015: 179).

That devolution did not entail a radical overhaul of the workings of the core executive will be unsurprising to students and scholars of British politics. As Marsh et al (2003) make clear in their development of the APM, the British political system is characterized by a particular conception of democracy, a concentration of power within Westminster and Whitehall, and a prevailing notion that the UK government knows best. Understood more widely as representing a core element of the BPT that emphasizes a ‘top-down’ view of democracy (Marsh 2008; Diamond and Richards 2012; Richards et al 2019), the idea of a strong, centralized core executive is a fundamental aspect of the APM. This belief in centralism and a power-hoarding executive is encapsulated in the sacrosanct principle of parliamentary sovereignty as well as a hierarchical understanding of governance (Marsh, 2008: 259). The dominance of this ‘elitist conception of democracy’ (Marsh and Hall, 2016: 128) is shaped by a limited understanding and narrow vision of the British political system and the unitary mindset of political elites (ministers, civil servants, and politicians more generally), more suited to the nineteenth century than the twenty-first (Blunkett and Richards 2011; Diamond and Richards 2012; Richards and Smith 2016). Arguably a result of bipartisan loyalty to the BPT by the Conservative and Labour parties at the UK level (Blunkett and Richards, 2011: 179), the BPT remains an enduring force and ‘a cornerstone of elite actors’ and citizens’ understandings of the British system of government’ (Sandford, 2023: 3).

This was made explicitly clear in Section 28 of the Scotland Act 1998 which while providing that the Scottish Parliament can make laws for Scotland, also noted in subsection 7 that ‘this section does not affect the power of the Parliament of the UK to make laws for Scotland’. A similar provision can also be found in Section 107(5) of the Government of Wales Act 2006. The assertion of parliamentary sovereignty underlined the hierarchical approach to governance (as discussed in the APM), specifically the idea that the Westminster Parliament has merely ‘loaned’ powers to the devolved institutions and ‘can in principle, revoke them and invade devolved competences’ (Keating and Laforest, 2018: 8). As Lord Sewel, then Parliamentary Under Secretary of State at the Scottish Office, noted during the passage of the Scotland Act in 1998:

We are setting about a devolved settlement – nothing more, nothing less. It is not the first step on the road to some other settlement, whether that be independence or federalism. It is a self-contained settlement, based on the principles of devolution. Essential to that is the recognition that sovereignty remains with the UK Parliament. The UK Parliament retains the ability to legislate on all matters (The House of Lords, 21 July 1998)

Devolution, therefore, entailed only ‘limited modifications at Westminster’ and rather than representing a challenge to the traditional political orthodoxy, was ‘a way in which centralized power, albeit altered, could be reaffirmed and protected’ (Hall et al, 2018b). That said, the ability to ‘invade’ devolved jurisdictions was tempered by the introduction of the eponymous Sewel Convention, latterly enshrined in the Scotland Act 2016 and Wales Act 2017, which states that ‘the Parliament of the United Kingdom will not normally legislate with regards to devolved matters without the consent of’ the Scottish and Welsh Parliaments. While for most of the two decades since the inception of the devolved institutions, the Convention operated without much controversy, it is merely a device of ‘voluntary constraint’ (McEwen, 2022: 739). As later sections make clear, in recent years, particularly in the contentious process of exiting the European Union (EU), the Sewel Convention has been repeatedly disregarded.

At first glance, the transfer of powers from central authorities to subnational institutions suggests a significant departure from the power-hoarding, top-down, and centralizing BPT described above. Indeed, with specific reference to the Scottish case, Hall et al (2018a: 368) point out that ‘Devolution, decentralization, and independence pose, to varying degrees, a challenge to the centralization of power, the desire to protect Westminster’s sovereignty and the notion that “Westminster and Whitehall know best’’’. In consonance with the enduring dominance of the BPT however, as well as the hierarchical approach to governance as highlighted in the APM, devolution is more accurately described as a ‘story of constitutional continuity’ rather than radical change (Sandford, 2023: 5). Political devolution in the late 1990s built on a fairly long history of administrative devolution in both Scotland and Wales, including institutions such as the Scottish and Welsh Offices, established in 1885 and 1965, respectively. These institutions, nonetheless, while representative of territorial distinctiveness within the British state in the development and delivery of policy across the different territories, were ‘part of Whitehall and accountable to Parliament at Westminster’ (Mitchell, 2003: 1). In the nineteenth century as much as in the twentieth, reformed constitutional arrangements, however much they seemed to represent a departure from traditional understandings of the British political system and the omnipresent BPT, were much in line with Bulpitt’s ‘central autonomy model’, reflecting its division of responsibility between high and low politics (Bradbury 2006). For Bulpitt (1983: 85) ‘the Centre is prepared to allow considerable operational autonomy to peripheral governments and political organization, so long as they do not challenge its autonomy in matters of “High Politics’’’. Devolution in the late 1990s followed suit. Elite control was maintained over core areas of high politics (e.g. defence and foreign affairs), thus preserving the enduring dominance of the BPT and the perpetuation of the ethos that, despite the creation of devolved executives and legislatures, on the issues that matter, it is the central government that will decide.

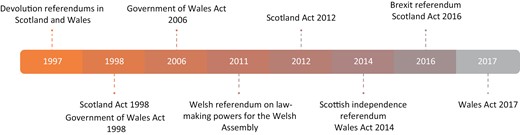

Prior to and in the aftermath of the establishment of the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly, there was a sense of optimism among advocates of devolution that the new institutions and political processes would usher in an era of ‘new politics’ characterized by ‘a more consensual elite political culture’ (Bradbury and Mitchell, 2001: 275). While two decades later, the success of a new politics remains a subject of debate (McMillan 2020), the hopes and dreams of doing politics differently were somewhat tempered in the first few years of devolution. In Scotland, Labour and the Liberal Democrats formed a coalition government in the aftermath of the 1999 and 2003 Scottish Parliament elections, but much like Westminster a pattern of executive dominance emerged (Simpkins 2022) as well as a continuation of traditional ‘confrontational partisanship’ between the Parliament’s main political parties (Cairney, 2011: 28). After the 2007 election and the formation of a Scottish National Party (SNP) minority administration, there was renewed optimism for the prospect of ‘new politics’, but while there was some cooperation with other parties on the part of the SNP to advance its policy agenda, ‘the main parties generally disengaged from Parliament’ and ‘the Scottish Parliament plenary was used largely as an adversarial forum and committees were not particularly effective’ (Cairney, 2011: 40). In Wales, the committee system likewise did not live up to expectations of enhanced scrutiny and cross-party policy development (McAllister and Cole 2007). Since 1999, Welsh Labour has been returned as the largest party in the legislature at every Welsh election, but it has never secured a majority of seats. As such, inter-party cooperation has been a feature of Welsh governance, though in the early years suspicion of coalition government largely hindered closer party-political cooperation (McAllister and Kay 2010). Akin to Scotland, from 2007 Wales entered a new era of devolution. The Wales Act 2006 formally separated the Assembly from the Welsh Government and for the first time gave the Assembly the power to make primary legislation. In addition, after the 2007 Assembly election and a protracted period of negotiations, Welsh Labour and Plaid Cymru formed a coalition government, but, like Scotland, politics largely remained ‘an adversarial business’ (Lundberg 2013). Despite, or perhaps as a result of, political tensions within each system, the devolution settlements did not remain static, with the further transfer of powers triggered in Scotland by the ascendency of the SNP, and the promises made in the 2014 referendum campaign, and in Wales, by an effort to deliver a more coherent system of devolution, empowering the executive and legislature, and to keep pace with Scotland (Fig. 1).

Despite the optimism and rhetoric of ‘new politics’, ‘the devolved institutions exhibit the pull of their genealogical roots’, created and shaped by Westminster politicians, some of whom stood for election in the devolved legislatures (Mitchell, 2010: 87). From the first crop of parliamentarians in 1999, circa 14 per cent of Members of the Scottish Parliament and 10 per cent of Welsh Assembly Members were already members of either the House of Commons or House of Lords (Goldberg 2017). As Hall et al (2018a: 370) note, ‘actors schooled in, and faithful to, the BPT, found it difficult to shake-off old habits, even if they wanted’. Notwithstanding the optimism of devolution proponents, the top-down, hierarchical, and executive-dominated politics embodied by the APM and BPT became fundamental features of devolved governance and territorial politics more widely in the UK.

3. 2010–23: the Conservatives and devolution

The results of the 2010 general election, specifically, the transition to full party-political incongruence across the UK–whereby different political parties were in power in Cardiff, Edinburgh, and Westminster–precipitated increased attention on issues of territorial politics and the implications for relations between the UK and devolved governments. Taking this watershed moment as our starting point, in this section we focus on three ‘constitutional moments’–the 2014 Scottish independence referendum; the Brexit debate; and the COVID-19 pandemic–to examine the impact of the BPT on successive Conservative governments’ territorial strategies as relates to Scotland and Wales. Our analysis charts a change in strategy from a more accommodative stance cognisant of territorial distinctiveness under the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government which saw further powers devolved to Scotland and Wales to an increasingly assertive Anglo-centric ‘muscular unionism’ predicated on the supremacy of the UK Parliament and indivisible notion of parliamentary sovereignty in the aftermath of the 2016 vote to leave the EU.

3.1 The Union under threat: from Indyref to a ‘balanced settlement’

In the aftermath of the 2010 general election and their elevation to government as the senior partner in the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, the UK Conservatives’ territorial strategy was 3-fold: a strong commitment to the Union; an acknowledgement of the need for the constituent units of the UK to work collaboratively together, underpinned by a ‘respect agenda’; and finally, an attempt to revive the party in Scotland and Wales (Randall and Seawright 2012). Cameron understood a revised position on devolution, and support for its expansion as necessary for the Conservative Party’s electoral revival in Scotland and Wales, even if only as a party of second place (Randall and Seawright 2012: 108-9). In its 2010 manifesto, while critical of Labour’s ‘constitutional vandalism’, the party pledged to work more constructively with the devolved governments in pursuit of a more effective Union (Conservative Party 2010: 83). In Cameron’s memoir, he rationalizes his decision to engage productively with both devolution and the devolved institutions, saying that ‘we had–wrongly in my view–opposed the devolution settlements in Scotland and Wales in the late 1990s, and had struggled ever since to find a constructive stance... only by giving people a real stake in their nation’s affairs could we continue to justify the Union and retain support for it’ (Cameron 2019: 304). While not without problems (see below), Cameron’s tenure saw signs of an electoral revival in Wales, albeit short-lived, and the seeds of a Conservative resurgence in Scotland which persisted, even as the fallout from the EU referendum exposed the fragility of the Union.

In consonance with its respect agenda, Cameron’s government sought to recast relationships with the devolved governments, pledging to increase intergovernmental interactions and present UK government ministers for questioning in Edinburgh and Cardiff (Arnott 2015). In the early weeks of his premiership, Cameron visited both Edinburgh and Cardiff and pledged to work cooperatively with the devolved governments in both capitals (BBC News 2010; UK Government 2010). It was not long, however, before relations with the devolved governments soured, largely a result of the UK government’s pursuit of austerity. Such was the opposition in Scotland that the Scottish Parliament refused consent for the UK Welfare Reform Bill in 2011, substantiated by vociferous criticism on the ramifications of austerity policies from the Welsh and Northern Irish institutions (Birrell and Gray 2016).

The Scottish Parliament’s first-time refusal of legislative consent, while predominantly a result of ideological divergence between the SNP government in Holyrood and UK Conservative-Liberal Democrat government in Westminster, was illustrative of wider issues regarding intergovernmental relations between the devolved and UK governments (McEwen et al 2020). Tellingly, these issues were not new; forums to facilitate intergovernmental interaction had fallen into disuse long before the Conservatives had taken power and while the electoral victory of the SNP in the 2007 Scottish Parliament election saw increased attention paid to intergovernmental relations, interaction remained ad hoc and infrequent (Swenden and McEwen 2014). That said, more intergovernmental meetings took place under the Conservatives from 2010 onward and new intergovernmental forums, such as the Joint Exchequer Committees, were established to facilitate the implementation of fiscal powers devolved by the Scotland and Wales Acts, 2012 and 2014 respectively (Anderson, 2022b: 100). These forums, nonetheless, were creatures of Whitehall; intergovernmental sites for debate and discussion and not co-decision making. Consequently, intergovernmental forums were generally considered ‘not fit for purpose’ with devolved-UK government relations coloured by the UK Government’s top-down view of devolution (Kenny and McEwen, 2021: 13).

2010–16 marks a remarkable degree of flexibility in the transfer of further powers to the devolved legislatures, in Scotland, triggered by the existential threat the SNP posed to the UK, and in Wales, where the devolution model seemed to be forever playing catch-up with Scotland. Further reform, however, was not rooted in a particular commitment to devolution and followed a similar ad hoc pattern as previous governments, ‘shaped by the controlling instincts of Westminster, rather than informed by a coherent and consistent vision of subsidiarity’ (Marsh et al. 2024). In Wales, following a referendum in 2011 in which 64 per cent of voters supported the extension of full law-making powers within the devolved competences to the Welsh Assembly, the UK Government established the Silk Commission whose recommendations formed the basis of the Wales Act 2014 (Awan-Scully, 2023: 298). In Scotland, debate on further devolution was also underway, the result of the electoral victory of the SNP in the 2007 Scottish Parliament election and subsequent Calman Commission, set-up by the pro-Union parties in the Scottish Parliament (with the support of the then Labour-led UK Government) to review the Scottish devolution settlement. Following the recommendations of the Calman Commission, which included new powers over borrowing and the creation of a Scottish rate of income tax, the UK Parliament passed the Scotland Act 2012 (Arnott 2015). By the time the Scotland Act 2012 was passed, however, the legislation had been over taken by events: in the 2011 Scottish Parliament election, the SNP was not only returned to power but also became the first party ever to secure an electoral majority, bringing the issue of a referendum on Scottish independence to the top of political agendas in Holyrood and Westminster.

The decision by the UK Government to temporary transfer power to the Scottish Parliament to facilitate the holding of a referendum exhibited a remarkable degree of constitutional flexibility, described by Convery (2016: 33) as a ‘triumph in intergovernmental relations for both sides’. The decision to grant a referendum to Scotland was met with little resistance within the wider Conservative party, convinced both that independence was unlikely and that a decisive victory would undercut the SNP (Torrance 2013: 15). Reflecting on the decision, Cameron explains: ‘While I could understand the desire to avoid a referendum, I thought it would be a much bigger gamble to thwart it. The sense of grievance against a distant-out-of-touch Westminster would only grow’ (Cameron 2019: 315). Although the decision to grant a referendum represents a radical step for a unionist political leader, it is consistent with the constitutional assumptions of the BPT and confidence by UK Government personnel ‘that their own political powers remained paramount’ (Sandford, 2023: 6). In this regard, the granting of a referendum to Scotland was not a challenge to the durability of the BPT but rather a tactical decision to reassert the supremacy of the Westminster Parliament and ‘to preserve [its] core framework’ (Sandford, 2023: 6). This, it is worth noting, was not a new strand of Conservative thinking. Thatcher, one of the most unionist prime ministers in modern history, in rationalizing her opposition to devolution in her memoirs wrote:

As a nation, they (the Scots) have an undoubted right to self-determination...what the Scots (nor indeed the English) cannot do, however, is to insist on their own terms for remaining in the Union, regardless of the view of the others... it cannot claim devolution as a right of nationhood within the Union (Thatcher, 1993: 624).

In the 2014 ballot, the UK Government rejected calls for a second question, a ‘devo-max’ question that would see further devolution to Scotland, on the basis that this would not represent a clear and decisive judgement of public sentiment, but also, that it was outwith the remit of the Scottish Parliament/Government to deliver such a reform. In this sense, and within the context of the BPT, the referendum was a tool to maintain the authority of central government, while initial debate on further reform was neutered by the fact that constitutional reform is within the purview of the UK Parliament only. However, as the referendum campaign drew to a close and the gap between yes and no narrowed, the leaders of the UK Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat parties signed ‘the Vow’, an unprecedented agreement that a ‘no’ victory in the referendum would deliver ‘extensive new powers’ for the Scottish Parliament. While scholars contest the impact of the Vow on influencing voting behaviour in the referendum (Henderson et al 2022), it nonetheless set in train a process of further constitutional reform. As Cameron (2014) commented the day after the vote:

So now it is time for our United Kingdom to come together, and to move forward. A vital part of that will be a balanced settlement – fair to people in Scotland and importantly to everyone in England, Wales and Northern Ireland as well… Just as the people of Scotland will have more power over their affairs, so it follows that the people of England, Wales and Northern Ireland must have a bigger say over theirs. The rights of these voters need to be respected, preserved and enhanced as well.

Notwithstanding Cameron’s commitment to enhance devolution across the UK, reforms were largely based on short-term thinking and akin to the New Labour devolution scheme were not part of a holistic project of constitutional reform. Contrary to the rhetoric of the UK Government (2015) which talked of further devolution to Scotland as ‘an enduring settlement’, further devolution was characterized by short-termism, with little attention paid to its long-term implications. As Marsh et al (2024) astutely observe, ‘the net result has been that of instability, short-termism and persistent policy shortcomings which challenges the notion that the Westminster Government operates as a rational and strategic manner’. This piecemeal approach to reform is a consequence of the power-hoarding, Westminster and Whitehall centric understanding of the Constitution in which powers are devolved only insofar as they do not limit the centre’s power (Diamond and Richard 2012).

The Smith Commission established to enhance Scottish devolution in the aftermath of the vote against independence took place on a timeline of the UK Government’s choosing and did not, by virtue of both time and structure, meaningfully engage with a more expansive understanding of reform (Kenealy et al., 2017: 77–102). The resultant legislation, which Cameron (2015) argued would make Scotland ‘one of the most powerful devolved parliaments in the world’, acknowledged the permanence of the Scottish Parliament and placed the Sewel Convention on a statutory footing. Within the context of the BPT, these reforms, however symbolically important, did not amount to altering the power of the dominant centre. Instead, they were an explicit accommodation of the changed circumstances wrought by devolution, but one that does not affect the sacrosanct principle of parliamentary sovereignty nor necessitate any reform at the centre. As discussed in the next section, this was made clear by the Supreme Court in its unanimous ruling on the Sewel Convention in the Miller case, as well as in the parliamentary debates on the passage of the Scotland Act 2016. In the words of Lord Keen, then Advocate General for Scotland, ‘It appears to us that, in light of the Smith commission agreement, the Government should be prepared to make that political declaration of permanence. It does not take away from the supremacy or sovereignty of this United Kingdom Parliament. That remains’ (House of Lords, 15 December 2015).

The unexpected return of a Conservative majority government in May 2015 saw the enactment of further devolution to Scotland and Wales, as laid out in the Party’s manifesto. The manifesto also promised a referendum on continued membership of the EU, the result of which had significant ramifications for territorial politics across the UK. The Scotland Act 2016 and Wales Act 2017 resulted in a marked expansion of the powers of the nations’ devolved legislatures, albeit in a radically different context than first envisaged. The Scottish Parliament, inter alia, gained additional law-making powers over abortion, equal opportunities and speed limits, powers to top-up and create new welfare benefits, and the power to set rates and bands of income tax (McHarg 2016). The Wales Act 2017 delivered further powers to the Welsh Assembly in areas such as electoral arrangements, energy, transport, and some control over income tax levels. In addition, the Act replaced the existing conferred powers model in Wales (in which the Assembly could legislate in only a limited number of policy areas), with a reserved powers model in which the Assembly can, akin to the Scottish Parliament, legislate on all matters except those reserved to the UK Parliament (Rawlings 2022).

In both cases, however, and contrary to the recommendations of the Silk and Smith Commissions to enhance intergovernmental relations between the UK and Scottish and Welsh governments, reform was not accompanied by more robust structures of intergovernmental cooperation to support increasing policy interdependencies between the UK and devolved legislatures (McEwen et al 2020). Once again, processes of constitutional reform were conditioned by the BPT and its hierarchical conception of the UK political system, with little attention afforded to intergovernmental working. They were also overshadowed by the 2016 vote to leave the EU which would put the UK’s constitutional order, and relationships between the centre and the devolved governments, significantly to the test.

3.2 Negotiating Brexit: from ‘Our Precious Union’ to muscular unionism

The vote to leave the EU in June 2016 marked the beginning of a protracted negotiation process, and significant upheaval between the UK Government and EU, the UK Government and devolved governments, and within the Conservative Party itself. Following Cameron’s resignation, Theresa May was elected as Conservative leader. In her first speech as Prime Minister, May (2016a) underlined her commitment to the Union and the importance of preserving ‘the precious, precious bond between England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland’. Akin to her predecessor, the rhetoric of the May premiership talked up the Union and constructive engagement with the devolved governments, and the new Prime Minister made visits to Cardiff and Edinburgh early in her tenure. May (2016b) committed to securing a ‘UK approach and objectives for negotiations’ before the triggering of Article 50 to leave the EU, including the establishment of the JMC (European Negotiations (EN)) as a sub-committee to discuss the UK’s Brexit strategy. However, beyond rhetoric there was little effort by the UK government to actively engage with the devolved governments in preparing for EU exit (Hunt and Minto 2017; McEwen 2022).

By the Conservative Party conference in autumn 2016, the commitment to a ‘UK approach and objectives’ had been reduced to a commitment to ‘consult and work with the devolved administrations for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland…’ (May 2016b). This was coupled with a statement stressing Whitehall’s prerogative:

But the job of negotiating our new relationship is the job of the Government. Because we voted in the referendum as one United Kingdom, we will negotiate as one United Kingdom, and we will leave the European Union as one United Kingdom. There is no opt-out from Brexit (May 2016b)

As opposition mounted from within the Conservative Party, Westminster, the courts, and the devolved governments and legislatures, May and those surrounding her reverted to a position of what Sandford and Gormley-Heenan (2020: 110) describe as a ‘reflex centralism’, rejecting the demands for consultation from outside Whitehall, a mainstay of the BPT. While May’s political position was weakened by the results of the snap 2017 election, leaving her without a majority and relying on a supply-and-confidence arrangement with the Democratic Unionist Party, her position on the devolved nations was strengthened by the Supreme Court’s Miller judgement which ruled that Brexit negotiations were in the domain of Whitehall and Westminster (McHarg 2018). Ruling that the Sewel Convention was a political not legal convention and thus declining to say whether the Court believed devolved consent should be sought to trigger Article 50, the Court’s ruling underlined that the statutory provisions of the Scotland and Wales Acts ‘would continue to be interpreted in line with the BPT’ (Sandford, 2023: 7)

From here on, the May government continued to pursue a more centralist, executive-dominated approach vis-a-vis Brexit negotiations, often at the expense of engagement and relationships with the devolved governments. The UK Government’s Withdrawal Act 2018, for instance, was vehemently opposed by the devolved governments which saw the Act as a ‘power-grab’ that, contrary to the rhetoric of the UK Government, weakened rather than strengthened the devolved settlements (McEwen 2021). Illustrating the power-hoarding impulse of the UK Government, the original Withdrawal Bill presented to Parliament by the UK Government initially re-reserved all competences returning from the EU to the UK level, including those that prima facie fell within devolved competence. For the Scottish and Welsh governments, the Bill represented ‘the first major restriction of Scottish [and Welsh] self-rule since devolution in 1998’ and as such both the Scottish and Welsh Parliaments refused legislative consent for the bill (Anderson, 2024: 99). Following changes to the legislation by the UK Government, the Welsh Parliament subsequently granted legislative consent, but the Scottish Parliament did not follow suit. With little constructive engagement with the devolved governments and the insistence on a UK government-led approach, the May government’s territorial strategy, undergirded by strong notions of elite accountability and a top-down understanding of policy, represented ‘a reassertion of the centralising, power-hoarding tendencies associated with the BPT that are deemed necessary to ‘deliver’ Brexit’ (Richards et al, 2019: 345). A result of this centralizing strategy, the much-heralded JMC (EN) failed in its principal objective; there was no UK-wide agreed approach to withdrawal. Indeed, the UK government gave notice to the European Council of its intention to withdraw without the consent or even knowledge of the devolved governments. Following a succession of failed attempts to pass the Withdrawal Agreement in Parliament and a string of challenges to her leadership, May resigned as Prime Minister in July 2019, succeeded by Boris Johnson.

The Johnson Government approach to the devolved governments was similar to that of Theresa May’s, albeit somewhat more combative (Hayton 2021). Although differing dramatically in their presentational styles, the May and Johnson leaderships were both characterized by an assertion of central power against the devolved governments. This was accompanied by an increasingly robust defence of the Union in the form of ‘muscular unionism’, a more assertive Anglo-centric territorial strategy in which ‘Britain is a single nation and a unitary state’ and ‘the devolved institutions are to be tolerated... but their powers are to be checked and contested, and, should the opportunity arise, clipped’ (Martin, 2021: 37). After taking office, Johnson (2019) advanced a pro-devolution lexicon and talked up the merits of ‘the awesome foursome’ of England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, but territorial strategy largely failed to live up to the rhetoric. Discursively, Johnson’s approach to both Brexit—and the institutions and individuals he perceived as thwarting the pursuit of Brexit—and devolution, was much more assertive than his predecessors.

As the Prime Minister sought re-election in 2019, a snap election centred on Brexit, the Conservative Party sought to play up the potential of decentralization, unfettered by the constraints of the EU. In contrast with the 2017 Conservative manifesto in which there was an identifiable commitment to the BPT (Richards et al 2019), the 2019 manifesto appeared to challenge some of that traditional orthodoxy. In advocating the flagship levelling up agenda, the manifesto stated ‘the days of Whitehall knows best are over. We will give towns, cities, and communities of all sizes across the UK real power and real investment to drive the growth of the future and unleash their full potential’ (Conservative Party 2019: 26). Like his predecessor, however, the Johnson government’s unionism and governing strategy more broadly perpetuated a top-down, Whitehall-centric understanding of policy (Kenny and Sheldon 2021; Ward and Ward 2023). As Diamond et al (2023) point out, the levelling up agenda focuses on reform of local governance and not, as is needed, reform to the structures of central government. Consequently, despite the APM-challenging rhetoric of the 2019 manifesto, the levelling up agenda operates within rather than challenges the BPT and upholds a ‘power-hoarding conception of British democracy’ (Diamond et al, 2023: 362).

The centralizing impulse of the UK Government is also evidenced in the UK Government’s pursuit of the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (UKIMA) introduced to avoid barriers to trade within the UK. Through the creation of a common regulatory project which places restraints on the regulatory competences of the Scottish and Welsh governments (Horsley 2022), the Act highlights the power-hoarding characteristics of the BPT and is illustrative of the ‘centralizing command’ inherent in UK Government actions over recent years. The UKIMA was enacted notwithstanding the refusal of legislative consent by the Scottish and Welsh Parliaments (and Northern Irish Assembly), which saw the Act as representing the most egregious form of encroachment on devolved powers and a threat to the future of devolution. Marsh et al (2024) argue that the consequence of the centralizing impulse of UK Government actions in recent years ‘is a reactive, inconsistent, interventionist, sometimes arbitrary governing style that is anything but strategic in providing clear and effective policies to address complex policy challenges’. The UKIMA is a case in point.

Further, the Act constituted what Rawlings (2022) describes as a form of economic unionism, evidenced in the development of the Shared Prosperity Fund, the UK Government’s replacement for the European Structural and Investment Programme, which enables the UK Government to spend money in devolved areas, bypassing interaction with the devolved governments and once more emphasizing the prominence of the BPT (Andrews 2021). The Shared Prosperity Fund comes under critique by the devolved governments, both for its failure to match funds received from EU schemes and for its failure to consult with the devolved governments (Morgan and Wyn Jones, 2023: 4). For former Welsh First Minister, Mark Drakeford (2022) the Fund is a ‘scheme devised by the UK Government; made in Whitehall… [with] no sense at all that it understands the Welsh context in which it seeks to operate’.

The protracted process of the UK’s exit from the EU had significant implications for the operation of devolution in Scotland and Wales. The actions of the governments of both Theresa May and Boris Johnson were undergirded by a reincarnation of parliamentary sovereignty, the notion of a strong executive, and the durability of a UK Government knows best attitude. For Marsh et al (2024), the latter was largely undermined by the poor political performance of the UK Government, a pattern that was likewise repeated in its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.3 The COVID 19 pandemic and beyond: from ‘the awesome foursome’ to disunited kingdom

By the time the first cases of COVID emerged in the UK in January 2021, political crises had become the norm rather than the exception (Anderson et al., 2023). The COVID-19 period was characterized by significant social, political, and economic instability, and ultimately brought an end, in summer 2022, to Boris Johnson’s premiership. Meanwhile, the devolved governments in Scotland and Wales saw a greater degree of recognition, and both the Scottish and Welsh independence causes experienced boosts in support, albeit at levels difficult to sustain over time. In Scotland, support for independence averaged around 54 per cent between June 2020 and January 2021, ‘the first time ever that polling had so consistently put independence ahead’ (Curtice 2022), while in Wales polls recorded an upward trend in support for independence averaging between 20 and 30 per cent from 2020 to 2021 (Cordner 2022). Following revelations of repeated breaches of COVID lockdown restrictions by Boris Johnson and others in Downing Street, the issuance of fixed penalty notices for having broken the law during lockdown, accusations of lying to Parliament and ultimately a significant number of ministerial resignations, in June 2023 Boris Johnson was forced to resign. Liz Truss was elected Conservative Party leader, but following a calamitous mini budget she resigned and was replaced by Rishi Sunak (Jeffery et al 2023). During this period, little attention was paid to issues of devolution or the Union, but the UK Government’s position on refusing consent to a second Scottish independence referendum was bolstered in late 2022 by a ruling of the UK Supreme Court that the Scottish Parliament does not have the legislative competence to hold a referendum on independence; a second referendum is within the gift of Westminster only (Psycharis and Mills 2023).

The onslaught of the pandemic from early 2020 precipitated a significant challenge to the governance of the UK. Contra to the traditional silo working of the UK government and its various ministries and departments, the scale and urgency of the COVID crisis necessitated close cooperation between all levels of government in the UK. As such, in the early throes of the pandemic, there was unprecedented intergovernmental interaction between the UK and devolved governments, with focus on a ‘four nation approach’ to manage the pandemic. This resulted in the publication of a jointly produced Coronavirus Action Plan, the participation of First Ministers in COBR meetings, regular interaction between ministers and officials in newly created intergovernmental forums and legislative consent for the Coronavirus Act 2020 (Anderson 2022a). In contradistinction to the prevailing ethos of the APM and Westminster and Whitehall know best approach, the largely decentralized approach to the pandemic appeared to cast the UK Government in a largely coordinating role with limited authority in the devolved territories vis-à-vis mitigation and prevention measures.

That said, the somewhat coordinated approach to the pandemic was short-lived, a result of the unilateral actions of the UK Government from May 2020 in easing lockdown rules in England and changing previously agreed communication messages without prior consultation or negotiation with the devolved governments. On 10 May, for instance, Boris Johnson announced a change in message from ‘stay at home’ to ‘stay alert’ but this was rebuffed and criticized by the Scottish, Welsh, and Northern Ireland governments which continued with the ‘stay at home’ message. At the time, the devolved governments justified the continuation of the previously agreed communications as a result of ‘varying infection rates in the different territories’, (Schnabel et al, 2023: 20), but the unilateral actions of the UK Government once again hinted at a unitary mindset and re-emergence of the ‘UK Government knows best’ mentality. Indeed, former Welsh First Minister, Mark Drakeford (2024: 113) forcefully acknowledged this in his evidence in the UK COVID Inquiry, describing unliteral changes by the UK Government, which also included disbanding newly created intergovernmental forums, as ‘a bleak moment’ in the handling of the pandemic.

Despite the previously described unprecedented interaction between the UK and devolved governments, revelations at the UK COVID Inquiry pointed to a rather dysfunctional relationship during the pandemic, at times coloured by the constitutional preferences of the respective governments, notably in Scotland and Westminster. As well as this fractious relationship, in true BPT fashion, UK Government witnesses, including Boris Johnson and Scotland Secretary Alistair Jack, championed the idea that in the event of future crises ‘a more centralized approach’ in which Westminster and Whitehall would lead the charge would be the most appropriate response. Notwithstanding the often incoherent and perceptibly poor performance of the UK Government’s reaction to the pandemic (Morphet 2021; Diamond and Laffin 2022), as well as public opinion that throughout the pandemic habitually rated the performance of the Scottish and Welsh governments much higher than the UK Government (YouGov 2020), its principal personnel still believe that Westminster and Whitehall know best.

Further illuminating the prevalence of this unitary and centralist mindset within Westminster as well as a hierarchical understanding of territorial power, in his written evidence to the Inquiry, Boris Johnson noted that he did not believe as Prime Minister it was necessary to have regular interaction with the leaders of the devolved governments:

It is optically wrong, in the first place, for the UK Prime Ministers to hold regular meetings with other DA [Devolved Administrations] First Ministers, as though the UK were a kind of mini-EU of four nations and we were meeting as a ‘council’ in a federal structure. That is not, in my view, how devolution is meant to work (Johnson 2023).

Analysing the discursive rhetoric of the UK Government in the first few months of the pandemic, Finlayson et al (2023: 340) argue that the relationship between the state and the public ‘was overwhelmingly figured around a distinctive and established set of politico-discursive claims characterized by a ‘government knows best’ attitude associated with the British Political Tradition’. As the actions and remarks of the former Prime Minister above illustrate, the same argument can be made of the UK Government’s approach to the devolved governments, whereby the initial strategy of joined up working gave way to a unilateral strategy with only limited interaction with the devolved governments.

Liz Truss’s short-lived premiership was notable only for her lack of engagement with the question of the Union. In a leadership husting, she pledged to ignore Nicola Sturgeon’s calls for another referendum, saying ‘I think the best thing to do with Nicola Sturgeon is ignore her...She’s an attention seeker, that’s what she is’ (BBC News 2022). She failed to call any of the devolved leaders during her tenure. Her successor, Rishi Sunak entered office buoyed by the Supreme Court’s decisive ruling against another independence referendum and signs that the SNP’s electoral hegemony was under threat, albeit from a resurgent Scottish Labour, rather than the Conservatives (Brown Swan 2023). Sunak maintained the position of opposition to a second referendum and explicitly rejected calls for further devolution in Wales, most notably the devolution of justice and policing, a longstanding demand of Welsh campaigners (Hayward 2023).

In his 2023 conference speech, heralded as an opportunity for Sunak to set out a plan for change, engagement with devolution was almost entirely absent. Akin to his predecessors, the Sunak Government pursued a more aggressive tact towards Scotland with two notable interventions: the first, the blocking of the Scottish Government’s Gender Recognition Reform Act, and the second, the refusal of the necessary exemption to the Internal Market Act to make a Scottish bottle deposit scheme possible. In January 2023, the UK Government, for the first time, used Section 35 of the Scotland Act, which allows it to challenge Scottish legislation where it believed it would have ‘an adverse effect’ on reserved matters, to challenge the Scottish Government’s Gender Recognition Reform Act. While this legislation was passed with cross-party consent within Holyrood, the UK Government considered it to have practical consequences for reserved matters and therefore prevented the Bill from being submitted for Royal Assent. In summer 2023, the Scottish Government’s Deposit Return scheme was refused the requested exclusion to the UKIMA. Under this provision, devolved governments which wish to use their legislative powers to introduce policies that restrict market access principles must seek an exclusion to the Act to enable this (Dougan et al 2022). The UK Government opted for a more limited exclusion, necessitating a significant delay of the scheme just months prior to its introduction. Devolved governments have raised concerns about a stifling effect on policy, given the process, timing, and uncertainty in securing UKIMA exclusions. As Marsh et al (2024) note, a trend in the ‘post-Johnson Conservative Governments is a further attempt to use Parliamentary Sovereignty to reassert the dominance of the executive’ and further illuminate the more confrontational approach the UK Government has adopted towards the devolved governments in recent years (Brown Swan and Anderson 2024). Notwithstanding the upheaval of three prime ministers within just one parliamentary term, the top-down, hierarchical, Westminster and Whitehall know best attitude was a steady constant.

4. An unstable Union: constitutional futures

In the fourteen years of Conservative government, discussions on devolution and the future of the Union have been a regular feature of parliamentary and political debate. The Conservative government acquiesced to the 2014 referendum in Scotland, however, the vote failed to settle the question of Scottish independence. Support for independence has remained steady around the 45 per cent, with rises precipitated in part by Brexit and the COVID pandemic. The experiences of these crises have also seen increased constitutional contestation in the UK’s other constituent territories, manifest in heightened discussions on Welsh independence, Irish unification, and further devolution across England. Despite such proclamations that the Union represents ‘the most successful political and economic partnership the world has seen’ (Gove 2021), its recent history has been marked by a sustained period of instability.

As the analysis of the UK Conservative Party’s devolution strategies toward Scotland and Wales demonstrates, recent years have seen a more direct articulation of the BPT, which, as our analysis shows, becomes even more explicit at moments of crisis, when political elites attempt to assert authority and maintain control. Notably, this has primarily been discursive in the form of muscular unionism, a political strategy designed to assert primacy over the devolved governments, while concomitantly appeal to a more Conservative voter base. Assertions that the Conservatives would address the prevailing attitude of ‘devolve and forget’ and play a more active role in the devolved territories, evidenced in the UKIMA, Shared Prosperity Fund and levelling up agenda, underline the more active role adopted by successive Conservative leaders in recent years. Framed by the devolved governments as threats to the devolution settlements, the top-down, hierarchical and ‘Government knows best’ approach of UK Conservative governments has significantly damaged relations with the devolved governments. Legal proceedings and challenges to the exercise of devolved powers have exposed the fragility of the constitutional underpinnings of the Union particularly in the face of a more assertive Conservative government willing to flex its constitutional authority.

The findings of our paper illuminate the continued relevance of the APM in the study of British politics. Much like the original model, the revised APM emphasizes the omnipresence of the BPT in influencing understandings of democracy, policy, and as we have examined in this paper, territorial strategy. As Marsh et al. (2024) accord, tensions remain between ‘decentralization–recentralization’ dynamics, reinvigorated by disrupting events such as the UK’s exit from the EU. Furthermore, the revised model notes that while the notion that the UK Government know best remains, government actions in managing Brexit and COVID, ‘directly challenge the key BPT ideational assertion that the Government does in fact know best’ (Marsh et al., 2024). As the analysis of this paper shows, there is evident merit in this assertion. Yet, while devolution has created multiple centres of power across the UK each of which represents a further challenge to the dominance of the BPT, and while for some, or indeed many, it may become increasingly clear that Westminster and Whitehall do not know best, the enduring legacy of the BPT means that politicians and civil servants in Westminster and Whitehall continue to think that they do. And therein lies the rub. For the political elite operating in Whitehall and Westminster, the stability of the UK’s governing institutions is predicated on the strong executive and top-down governance associated with the BPT. This understanding of governance, however, risks further destabilizing and jeopardising the continuation of political union. Put differently, the continued dominance of the BPT and a more assertive and aggressive Unionism pose as great a threat to the continued existence of the UK state as, for example, Scottish and Welsh secessionism (Anderson 2024).

For over a decade, the Union has faced an existential crisis. Buffeted by internal dynamics, with clamour for Scottish independence, and latterly growing discussions on the position of Wales and Northern Ireland within the Union, the Union remains under stress. Labour’s landslide victory in the 2024 general election offers an opportunity for the new government to forge a less combative approach to UK-devolved government relations and in turn seek to strengthen the Union. The party overcame its electoral doldrums in Scotland, increasing its share of the vote by almost 17 per cent with a net gain of 36 MPs, largely at the expense of the SNP which saw its 2019 cohort reduced from 48 to just 9 parliamentarians. In Wales, although Labour’s share of the vote fell by almost 4 per cent compared to the 2019 election, the party won 27 of Wales' 32 seats. In his first press conference as Prime Minister, Keir Starmer promised an ‘immediate reset’ of the relationship between the UK and devolved governments, followed by visits to Edinburgh, Cardiff, and Belfast to meet with the respective First Ministers. The Labour manifesto advocated strengthening the Sewel Convention through a new memorandum of understanding and committed to ‘greater collaboration and respect’ in working with devolved governments, including a Council of the Nations and Regions to bring together the Prime Minister, the devolved leaders in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland and the English mayors. In a sign of the party’s commitment to devolution, the manifesto further advocated transferring power away from Westminster and Whitehall to local communities. These warm words are a contrast to the more muscular unionism advanced by the Conservative Party in its final years in government, but reforging the bonds of Union is likely to require significant political capital as well as more strategic, long-term thinking vis-à-vis devolution and reform.

Rebuilding and strengthening relations between the different governments in the UK is a necessary and worthwhile endeavour for the current and future governments. Labour’s more collaborative approach might extend to a reconceptualization of territorial strategy and the BPT more broadly, though this would require significant political will. Will, nonetheless, that a government facing crises on multiple fronts might find difficult to muster. Twenty-five years after the establishment of the Scottish and Welsh Parliaments, we can expect questions on devolution, territorial management, and the future of the Union to persist.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this article.