-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Farah Hussain, Enduring inequalities in British politics: Muslim women in the Labour Party, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 77, Issue 4, October 2024, Pages 713–734, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsae025

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article combines an understanding of British politics grounded in the Asymmetric Power Model with intersectionality to comprehend Muslim women’s experiences in the Labour Party. This paper shows that an intersectional framework and an analysis of political parties’ relationships with their members are essential to understanding the enduring inequalities of the British political system. Muslim women are under-represented in our political system; they face multiple forms of discrimination (racism and sexism). Some Muslim men have and use their relative power over Muslim women through their use of biraderi-politicking, and Muslim women do not trust the Labour Party to support them.

1. Introduction

Centring the experiences of Muslim women in the Labour Party, this article shows how enduring inequalities stemming from our unequal socio-economic society continue to characterize the British political system. Twenty years since Marsh et al. first published their article on the Asymmetric Power Model (Marsh et al. 2003), this paper expands their analysis to include a discussion of the role political parties play in determining the representativeness of our politics. This article develops their analysis by applying the inequalities they discuss in the abstract to the reality of one group of those under-represented in our political system. By using new qualitative data from semi-structured interviews with Muslim women active in the Labour Party, it centres these women’s experiences and shows how racism and sexism combine to hinder these women’s political careers. It shows how South Asian Muslim women are more under-represented than Muslim men because of how their ethnic identities and sex intersect. This article expands the Asymmetric Power Model beyond the constitutional actors identified by Marsh et al. to include an analysis of the role political parties play in perpetuating enduring inequalities. The findings of this article, which are that Muslim women face both racism and sexism, that Muslim men are able to disrupt their political careers and that the women feel unsupported by the Labour Party, emphasize that the relationship between parties and their members is key to understanding why some people are less visible in British politics. The Labour Party’s embrace of biraderi kinship networks, the lack of ‘champions’ of the Muslim women’s cause within the party and the failure of the party’s complaints process to invite trust from its members means that Muslim women are unable to progress their political careers within the most diverse political party, and therefore are under-represented in our political system. With the Labour Party having won a landslide election in 2024, understanding the role that political parties have in fostering diversity of our political representatives is fundamental to fully-appreciating the scale of the barriers that still exist to achieving gender and ethnic parity in the British system.

2. What we know about Muslim women’s representation

The general state of play of British politics has not drastically changed since Marsh et al. described it as ‘white, middle-class and male’ in 2003. Women remain under-represented in national politics, where across the House of Commons, only 35 per cent of MPs are female, although the Parliamentary Labour Party is now over 45 per cent women. In local government, only 36 per cent of over 19,000 local councillors are women (Sobolewska and Begum 2020). In terms of ethnic minorities, compared to constituting 14 per cent of the general population, only 10 per cent of MPs and 7 per cent of local councillors are from ethnic minority backgrounds (Sobolewska and Begum 2020).

Getting a comprehensive picture of the political representation of specific religious communities is difficult as these records are not kept, and it is methodologically difficult to accurately guess a person’s religious beliefs from name or photo. However, as most Muslim people in the UK are South Asian, we can deduce from other data that Muslims are under-represented in our political system. South Asians make up just 5 per cent of local councillors (Sobolewska and Begum 2020).

While the number of Muslim female councillors has increased in recent years, South Asian women remain under-represented at all levels of government, with only 37 per cent of South Asian councillors being women, compared to 63 per cent of them being men (Sobolewska and Begum 2020). Even in London, where ethnic minority representation is generally higher than in the rest of the country, Asian women in general are under-represented, while Asian men are over-represented (Muroki and Cowley 2019). Although it is imperfect, the uneven representation of South Asians in Britain points to differences in the experiences of South Asian/Muslim men and women, which can help explain why they are not equally as visible in the political system.

3. The Asymmetric Power Model, representation and intersectionality

In this article, I expand upon the Asymmetric Power Model to include an analysis of enduring inequalities within political parties that contribute to representational inequality within the British political system by examining the case of Muslim women in the Labour Party. This article also contributes to our understanding of enduring inequalities by focussing on local government political actors, thereby casting its gaze further than Westminster politics. While the Asymmetric Power Model tells us that inequalities exist in the British political system, intersectionality is employed in this paper to explain why and how Muslim women remain under-represented in our politics, and how the Labour Party contributes to this underrepresentation. Intersectionality helps to elaborate on the key arguments of the Asymmetric Power Model by providing a framework for understanding how unequal power relations function in society and how those with multiple disadvantages often face complex forms of inequality. Used together, as this paper does, these two frameworks help us understand how these forms of inequality play out in a fundamentally unequal political system such as the British one.

Critiquing the Differentiated Polity Model and adapting Rhodes’s model of British politics, the Asymmetric Power Model is a much more ‘convincing, explicit organising perspective of the British political system’ (Marsh et al. 2003: 307). Marsh et al. call for other scholars to acknowledge and further explore the asymmetries of power relations, supplementing their own research that provides evidence of ‘structured inequalities that still exist in British politics’ (Marsh et al. 2003: 307), which this article heeds. The Asymmetric Power Model describes a political system that is closed and elitist and is the natural outcome of a social and economic system characterized by ‘structured inequality which is reflected in access to crucial political resources such as money, education and key political positions’. (Marsh et al. 2003: 309). Class and ethnicity are acknowledged as key indicators of access to educational resources, and as we will later discuss when examining Muslim women’s experiences, whether a political actor is a man or woman, and the ways in which their multiple characteristics interact also play significant roles in their ability to gain support within political parties and their chances of political success. Although our governments, national, regional and local, have become more diverse since Marsh et al. first published their article in 2003, it is still the case that some interests are better represented than others.

Marsh et al. show how examining the British system through the lens of the Westminster model could allow one to believe that the British system is representative, as we do indeed have ‘periodic free and fair elections’ and as a model, it pays little attention to questions of demographic diversity of political representatives and how well they represent their views of their constituents (Marsh et al. 2003). The Asymmetric Power Model, however, does emphasize the importance of these forms of representation and demonstrates that because of enduring socio-economic inequalities seeping into the political system, British politics is not as representative as the Westminster model implies. This critique of the Westminster model and the prevailing consensus amongst British political scientists has been developed by Sadiya Akram in her 2023 article Dear British politics- where is the race and racism. She argues that the focus on the Westminster model and what are seen as ‘core areas of government, parliament and related actors and institutions’ equates to a neglection of questions of race and racism and the impact of this social construct on politics and political participation (Akram 2023: 11). While Akram argues that some of Marsh et al.’s arguments are important, she does not believe that they do enough to unpack inequalities beyond the core institutions and processes of Westminster politics. Heeding Akram’s call to ‘go further than [Marsh et al.] do in thinking about structural inequality’ (Akram 2023: 13), this article is a deep dive into the case of Muslim women’s representation. Here we not only look at what forms racism and sexism can take, but how they affect Muslim women’s political careers.

This article also represents an extension of Marsh et al.’s analysis beyond the civil service, government, and think tanks to include the role of political parties in helping to perpetuate enduring inequalities. Throughout our political system, even at the local level, it is incredibly difficult for anyone to get elected without the support of a political party. That means that the relationship between parties and their members and the outcomes of party selection processes, the ways in which political parties decide who they endorse as candidates, are key to understanding why our political system remains unequal and unrepresentative of the wider population. As Bale argues, political parties are ‘the ghost in the machine’: key to understanding why the political system is the way it is but often overlooked by political scientists (Bale 2023: 6), including Marsh et al. This article addresses this blind spot by treating political parties and local government as part of the political system rather than merely actors within it. Further, in this paper, local government is treated as an important arena of politics in its own right—it accounts for around one fifth of all government spending (Great Britain 2023), and because it can act as a pipeline to parliament for politicians (Norris and Lovenduski 1995).

While the Asymmetric Power Model highlights longstanding inequalities in the British political system, it is limited in its scope and focus. By using intersectionality to examine the experiences of Muslim women in the Labour Party, this paper makes the theoretical contribution of combining a focus on the British system with an intersectional outlook, shining a light on how and why those at the intersections face discrimination and filling a gap in the existing literature. As a tool of understanding, intersectionality is essential to fully comprehending Muslim women’s experiences. It allows us to elaborate on Akram’s analysis, making not only the point that race is a significant factor in an individual’s ability to access our political institutions but that the way that race affects people intersects with other factors such as gender and class. Applying intersectionality to this case study allows us to examine all relevant power relations that impact Muslim women’s lives and the political opportunities they have within the British political system.

Intersectional analyses centre the experience of black women and view their lives as ‘unique and valuable’ in the study of power structures and society (Hooks 2000). The theory refuses to treat gender and race as mutually exclusive categories of analysis. Crenshaw, (1989) uses intersectionality to illustrate the social positioning of black women in society and how their lived experience cannot be explained by simply adding together the experience of white women and the experience of black men. Instead, the systematic inequalities that they encounter can only be understood by analysing how gender and race interact with one another and shape their lived experiences.

Intersectionality equips us with the tools to go beyond inter-group analysis and examine relationships and power structures within social groups, thereby allowing us to question our ideas of group homogeneity and encouraging the interrogation of societal categorization of people.

Patricia Hill Collins has written of how, although black organizations claim to speak for all black people, black women have historically never held leadership positions within these organizations (Collins 2000). In such organizations, women are not only rendered secondary and invisible, but when they do begin to question their subjugated position, they face opposition and hostility from male members. This adverse reaction is often characterized by claims that by fighting gender inequality within black spaces, black women are acting in a way that is counter-productive to the wider struggle of black power (Collins 2000).

Progress has been made in recent years to build upon earlier work and expand intersectionality beyond its geographical roots and create a more European understanding of the theory. More recent applications of intersectionality to European case studies have also allowed a greater understanding of the role dual characteristics can play in shaping women’s lives. Particular progress has been made in applying intersectional understanding of the societal positioning of ethnic minority women in relation to political representation in local and national politics.

In the case of Muslim women, intersectional studies show us that they are often less associated with conceptions of violent Islamism and more assimilated into majority society than their male counterparts and are therefore favoured as candidates by political parties (Murray 2016). Muslim women are sometimes used as tokens of diversity by governments as a tactic to appear more diverse and inclusive than they actually are. Sometimes, therefore, ‘multiple social inequalities do not always ‘add up’, but sometimes lead to multiple advantages’ (Mügge and Erzeel 2016: 505).

Being the most diverse political party in its representatives (House of Commons Library 2023) and voting base (Martin and Khan 2019), and with a commitment to equality at the centre of many of its policies and processes, including All Women Shortlists, the Labour Party would seem the ideal place for Muslim women to do well and succeed. However, as this case study shows, its embrace of clan politics, its dysfunctional complaints system, and its lack of support for those facing discrimination mean that many Muslim women face barriers in their political careers in the party. Thinking about the wider British political system, these findings make one question what further examples of enduring inequalities other case studies would uncover and how other institutions’ behaviours contribute to underrepresentation in our politics.

4. Methodology

Together with the use of intersectionality as the theoretical framework, the research methods used in this study were chosen to centre the voices and experience of Muslim women. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with Muslim women and other people involved in the labour movement. Autoethnography was also used in order for me, as a researcher, to use my own experiences as a Muslim woman member of the Labour Party and former Labour councillor as part of the data-gathering process.

Interviewing has long been the preferred qualitative research method of by scholars researching the issues of race, class, and gender (Cuadraz and Uttal 1999). Semi-structured interviewing is particularly associated with academic feminism as it is the most appropriate research method when undertaking research that focuses on marginalized people. Feminist researchers not only want to explore women’s lives and experiences, but they also want to give a voice to the women they are studying, who have hitherto been largely silenced and absent in academic scholarship. In line with the feminist assertion that ‘the personal is political’ academics who associate themselves with the movement emphasize the integration of women’s narratives and voices into their research approaches (Stanley and Wise 1983). The method of in-depth semi-structured interviewing allows the interviewee to frame and understand issues and events in her own words (Few et al. 2003). The resulting interview data was coded and analysed to detect recurring themes, experiences and issues raised by the women.

Overall, twelve people were interviewed during the research process. Eight are Muslim women who are current or former Labour Party members and have stood for the party at the local level. All of the interviewees have been anonymized, although one has now left the party and was happy to be named. Although this number is small, it reflects the relatively small numbers of Muslim women involved in British politics, as outlined above, and the reluctance of some to discuss the issues of discrimination within their own political party. There is no denying that these issues are sensitive, and for those still involved in the Labour Party, it can feel too uncomfortable or too risky to discuss such matters, even with their anonymity guaranteed.

As a Muslim woman who has been an active member of the Labour Party and therefore personally connected to the research topic of this paper, I had a choice to make when first considering the methodological approaches to take. Simply put, I had two options: either I could ignore my positionality in the research topic that I have chosen, or I could embrace my experiences as valid and useful in answering the research questions outlined above. As (Ngundjiri et al., 2010) write, ‘scholarship is inextricably connected to self’, therefore it is impossible to separate oneself entirely from one’s research topic, even though political sciencsts have attempted to exclude the personal and self from scholarly research and writing due to the disciplines commitment to being a science (Burnier 2006). I chose to use the method of autoethnography which has allowed me to use my personal experiences in a meaningful way. Although relatively little known in political science, autoethnography is a popular research method in fields as diverse as sociology and public health (Ellis 2004) and is well-used in other social sciences such as geography (Burnier 2006). It is also not entirely untested in political science; former government minister, Tony McNulty used the method in his thesis on British government policymaking and politics. He summarizes his approach as one in which, as much as possible, he is both ‘a dispassionate academic inquirer and researcher as well as an active participant’ (McNulty 2018: 93).

There are multiple approaches to autoethnography. I have used analytical autoethnography, which is described as the ‘mind’ of autoethnography, compared to evocative autoethnography, which is the ‘heart’ (Burnier 2006). While evocative autoethnography uses tools such as personal narratives (Méndez, 2014), artefacts (Muncey, 2005), fiction, and poetry (Gallardo et al., 2009) to emphasize the emotive nature of the issues that they are researching, analytical autoethnographers are more likely to use personal narratives and self-reflection, often in the form of journaling, to document their experiences that they then analyse alongside other data.

Analytical autoethnography is more in keeping with political science scholarship and norms, with its emphasis on advancing broad theoretical insight into sociological phenomena (Burnier 2006). It does this by being less intimate and personal than evocative autoethnography, sometimes limiting the voice and experience of the scholar to mere glimpses (Burnier 2006). Anderson sees analytical autoethnography as a counterbalance to the postmodern sensibilities and literary approach of evocative autoethnography (Anderson 2006).

Practically, this approach has allowed me to transparently draw upon my own experiences where they are useful and acknowledge them during my interviews with other Muslim women in order to support the interview process (Griffin 2012). I have not included my own experiences in this paper as data or quotes, but they did enable me to have open and frank conversations with the Muslim women I interviewed who, although I did not know them all before the research process, were once my colleagues.

5. Findings of enduring inequalities: Muslim women in the Labour Party

In this section, I discuss the findings of my research and how these demonstrate the enduring inequalities of the British political system. I find that Muslim women face both racism and sexism and particular forms of discrimination stemming from their positionality at the intersection of sex and race; Muslim men have relative power over Muslim women in British politics through their use of biraderi networks that exclude women; Muslim women in Labour feel unsupported by their political party because of an absence of an organization that champions their cause and because of negative experiences with the party’s complaints process.

5.1 Finding one: Muslim women face both racism and sexism

5.1.1 Muslim women’s experiences of racism. According to data collected by Tell MAMA (Measuring Anti-Muslim Attacks), 58 per cent of racist incidents reported to its services by the British public were attacks on Muslim women (Allen et al. 2013). Although it was not the main theme I questioned them about, some of the Muslim women I interviewed raised unprompted their experiences of racist comments and incidents that they had faced as British Muslim women of South Asian heritage.

One, a councillor in London, described an incident where she had invited her mother to join her at her first Annual Council event marking the start of the new municipal year. An opposing councillor spoke to the Labour councillor’s mother and expressed astonishment that the councillor could speak English, was allowed to leave the house, and did not wear a hijab. When the councillor’s mother looked offended, the opposing councillor continued to say that it was not usual for Muslim women to speak English properly and leave the family home.

Another Labour councillor, this time in the Southeast of England, spoke of being removed from certain decision-making panels on the council just because she was Asian and there were already too many other Asian members present. She was replaced by a white woman.

These experiences support evidence gathered by the Muslim Women’s Network (MWNUK) that showed that anti-Muslim sentiment played a big role in Muslim women’s everyday lives (Wadia et al. 2011). This form of discrimination is felt by Muslim women in a number of ways; through the targeting of the community post-9/11 and 7/7 and through the increase in direct attacks, verbal and physical, from the public as they went about their daily activities. This means that rather than feeling more integrated into wider British society, Muslim women can feel increasingly marginalized from civic and political life (Wadia et al. 2011).

5.1.2 Muslim women’s experiences of sexism. Interviewees spoke of the sexist discrimination they have experienced at the hands of Muslim men in the Labour Party. Notions of ‘honour’ and a sense of ‘decency’ have a role to play in the way that these women are treated. There exists an idea within biraderi networks that ‘no good upstanding woman from a Muslim community would stand for election’ (Akhtar and Peace 2018: 1910). Muslim women Labour Party members interviewed for this research described how an idea of shame was used to prevent them from taking on prominent roles within the party. One spoke of how Muslim men in her local party did not appreciate her turning up for canvassing sessions when she first joined as a member, talking amongst themselves about how she had ‘no shame’ to be spending time with a group of men, even if it was for the purpose of campaigning for the Labour Party. These conversations about this member, who was subsequently elected as a local councillor, became increasingly personal to the extent that rumours were spread about her sex life, with some of her male colleagues complaining that the only way she was able to get promoted was by sleeping with men in the party.

Another woman spoke of how a group of men visited her parents-in-law’s and grandparents’ house when she first stood for local selection. They said that she should have checked with the men in her family before joining the Labour Party and that ‘girls shouldn’t be involved in this sort of thing’. In the end, she withdrew her application after a group of ten or so men came to her home to persuade her to drop out. When this councillor in the Southeast was finally selected as a local candidate, she was told that it would be better for her to use an older photograph of her wearing a hijab on her election leaflets, despite her taking the decision to no longer wear the headscarf.

Using honour and shame as ways to police behaviour, Muslim men actively organize to prevent women from standing for election either because the women are ‘too honourable’ and thus should not be corrupted by politics or because they are ‘too dishonourable’ and thus undeserving of the Labour Party and the local community’s support. As Lila Ramos Shahani (2013) has found, in British Muslim communities, Muslim women’s ‘bodies are invariably imagined as resources of men’s honor [sic] and volatile repositories of shame, making them subject to social control and sacrificial extermination.’

Either way, Muslim women who wish to stand for election for the Labour Party are prevented from doing so by powerful Muslim men. A sense of shame is also used to prevent these same women from complaining about the discrimination they face within the party. They are told to stay quiet about the abuse they face, with one woman describing how there was an overwhelming feeling amongst Muslim members of the Labour Party that women should not speak about the behaviour of Muslim men as if these issues are made public, it will ‘shame the community’. These women are not only victims of male privilege during selection meetings via the evocation of shame as a tool of subjugation, they are also prevented from complaining about the treatment they receive through a sense of shame and community honour and reputation. This echoes Patricia Hill Collins’ assertions of how Black women are treated by the wider Black community when discussing discrimination that they face from Black men (Collins 2000).

5.2 Finding two: Muslim men have relative power over Muslim women in British politics

5.2.1 Biraderi politics. The use of kinship or biraderi networks by Muslim men in the Labour Party and their exclusion of Muslim women from them was a recurring theme throughout my interviews with Muslim women.

Biraderi is an Urdu and Punjabi term that can be literally translated as ‘brotherhood’. It is used to describe a broad range of networks based on kinship and familial relationships within which members are expected to support one another in their aspirations and endeavours. While these support networks provided much-needed support to new migrants looking for friendship with others of the same heritage during the first wave of Muslim migration to the UK, they began to serve new purposes as the community became more established (Bouyarden 2013).

Biraderis are more than kinship networks, although a shared heritage plays a crucial role in determining who can and cannot be a member of the biraderi. Through supporting members with practical arrangements such as filling in forms, biraderis create systems of patronage and political power that political parties, particularly the Labour Party, have tried to use for their own electoral gain.

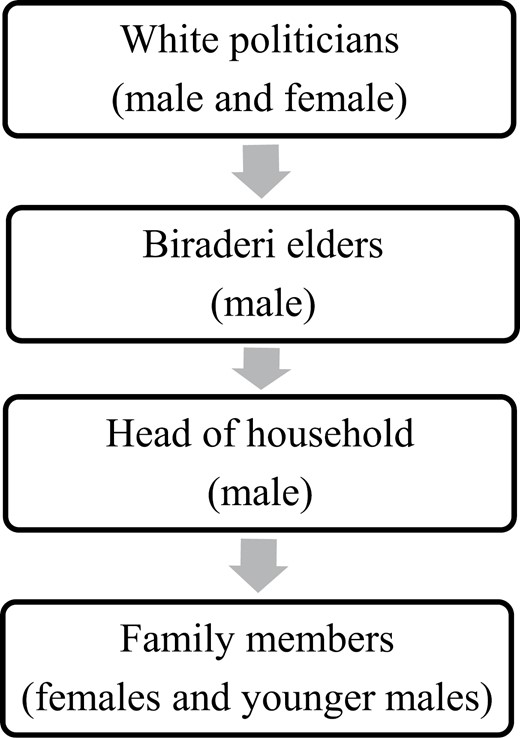

In the case of biraderis in Britain, biraderi elders (or community leaders as they are sometimes euphemistically known) use the client-patron relationships they have cultivated via biraderi networks to gain political influence, as shown in Fig. 1 below. They do this by becoming so important and powerful in the local community that without their support, any political candidate for local government office would struggle to win. Some biraderi elders claim that they control hundreds of votes through the influence they have over ‘heads of households’ in the local area (Hill 2018). Because local electoral districts are so small, and turnout for local elections is often low, these votes can be significant to the chances of a candidate winning or losing. Therefore, in some areas, personal relationships replace traditional electioneering as the method to gain votes and win elections in certain geographical areas (Hill 2018).

Interviewees said that they were aware of instances where local Labour officials and local politicians made these kinds of ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ with biraderi elders, some of whom called themselves ‘kingmakers’, so confident are they of the sway that they have over local Labour party selection processes. One of the women, the local councillor in the Southeast, said that it was openly known that selection meetings were only a formality; the outcome having been determined much earlier by male leaders of biraderi networks.

Biraderi elders are in their positions of influence and power because they have strong relationships with other members from the same ethnoreligious community and are also often involved in local religious institutions. By and large, such people are men. The Labour Party’s embrace of biraderi networks is inherently disadvantageous to Muslim women who are barred from membership of these patriarchal networks (Dancygier 2017). It also makes local party leaders and politicians unlikely to support Muslim women when they face patriarchal discrimination at the hands of men who are biraderi-connected.

A former councillor in the Northwest of England explained how ‘sexism [had] played such a huge role in her life’, although she had experienced discrimination from people outside of her community, what she had experienced from Muslim men in the Labour Party was ‘ten times’ worse. This woman, when she complained to her colleagues within the party about her experiences, including her council colleagues spreading rumours about her sleeping with men in the party as the only way she could get promoted, others photoshopping her face onto pornographic images and spreading them in the local community, and the way she dressed and behaved openly judged and commented upon, was told that this is ‘just politics’ and that she would have to get past this behaviour and build alliances with these men as they were well-connected and important locally.

5.2.2 The importance of party selection meetings. Looking from the outside, it may seem that party members are mostly involved in large national events, in fact the bulk of members’ activities take place at the local level (Russell 2005). There was a clear sense from the Muslim women I interviewed that it was at this local level that they faced discrimination, and it was particularly around selection meetings that they felt the full force of biraderi power.

Labour Party members play an incredibly important and powerful role in the selection of candidates, particularly at the local level, where once the interview process has been successfully completed, a potential candidate has only to convince a majority of members who attend a local ward selection meeting to choose them as the local candidate. In many local parties where meeting attendance is low, a handful of guaranteed voters can be invaluable to aspiring local councillors. The increase in individual party members’ power during selection processes through the introduction of One Member One Vote has given potential candidates with established personal connections advantages in these contests (Minkin 2014). This has provided a ‘huge incentive for aspiring candidates to mobilize individuals to sign up for party membership’ (Akhtar and Peace 2018: 5). Seventy-four per cent of Muslim councillors interviewed by Purdam (2001) said that they knew of cases where party members have attempted to gain support for selection by invoking loyalties through biraderi networks. In contrast, parliamentary selection processes are more difficult to influence in this way as the larger geographical area of parliamentary constituencies means that they are very often more ethnically diverse than wards and the power of the biraderi network is diluted.

Two of the women, despite being from different ends of the country, spoke of how some men within their local parties referred to themselves as ‘Kingmakers’ so sure were they of the influence they had over local parties and the decisions they make in relation to candidate selection. These women, respectively, a current and a former councillor from the Southeast and Northwest of England, described how these men used their positions for business purposes to elect local councillors who they thought would be easier to persuade to pass their planning or licensing applications. These men spoke quite openly about the influence they had over local parties, boasting about their power and using it to ensure that compliant and sympathetic local councillors were elected.

Akhtar calls political manoeuvring by biraderi networks ‘biraderi-politicking’ (Akhtar 2013). Biraderi-politicking and biraderi networks are not necessarily synonymous. While biraderi networks are needed for biraderi-politicking, they do not always have a political function (Akhtar 2013).

When discussing any group, such as a biraderi, there are always two mechanisms at play: in-group solidarity on the basis of shared characteristics and out-group hostility towards those who do not belong (Martin 2016). Therefore, while biraderi networks have been useful for some Muslims as a mechanism to gain party candidacy and other influential roles within party structures, such as Constituency Labour Party (CLP) Chair, there are people who miss out because they are not members of these networks: people of other ethnicities, younger Muslims and Muslim women. Muslim women who are also younger than the average Labour member and, therefore, face more intersecting forms of discrimination are further disadvantaged. The barring of non-South Asian Muslims from biraderi networks is relatively easy to explain: they do not belong to the clan, come from the same village in the Indian subcontinent, nor have the same family background as biraderi members, so cannot join. The factors at play in relation to younger Muslims and Muslim women’s exclusion from these networks are more complex.

It is clear that, as with younger Muslims, biraderi networks are used to actively block Muslim women from party candidature (Akhtar and Peace 2018). Muslim women are disadvantaged by both uses of biraderi: within Labour party structures and also external to party structures. Muslim women are seen as less capable of bringing in biraderi votes from the local Muslim community at election time and are also excluded from the support given to male Muslims by biraderi networks through selection processes. There is also evidence that sometimes white party activists and members choose candidates based on their perceived ability to tap into biraderi networks for electioneering purposes (Hill 2018). In these kinds of assessments, women who are barred from biraderis are disadvantaged as they are not seen as assets in gaining the votes using patriarchal patronage systems of influence.

While biraderi leaders often get their way when it comes to selection processes, there are of course, times when they do not. One councillor in the Northwest experienced first-hand what it was like to go up against a strong biraderi network as a Labour-endorsed candidate. The opposition to her candidature culminated in a Labour Party member resigning his membership of the party and standing against her as a local election candidate after she was reselected to represent Labour. Her colleagues, people she had campaigned with previously, supported this independent candidate. She said:

“Die hard Labour activists and councillors supported an independent, behind the scenes, but also sometimes directly, not even behind the scenes. It was the worst kept covert operation ever.”

Talking about the emotional effect this had on her, she said,

“That was when I felt like these people actually really hate me. They really, really hate me… They must feel so strongly about the way they feel about me that they’d go to this extent.”

Standing outside a polling station on election day, supporters of the independent candidate would remark to voters about to cast their vote ‘Out with the old, in with the new, vote for a real man’. In the end, the Muslim woman councillor lost her seat, and the biraderi-backed independent candidate won. Looking back, she blames the Labour Party for not taking her concerns seriously,

“I kept telling people, I kept saying, look, these people are gonna come for me, I need support. They are Labour Party people, they have memberships, they are activists. But because they presented themselves as self-proclaimed ‘community kings’, the Labour Party believed that and then didn’t take the action that they needed to take at the right time to support me.”

It is clear from this Muslim woman’s experiences how the Labour Party’s embrace of ‘community kings’ or biraderi leaders can disadvantage those outside of these networks. The Labour Party’s selection processes, which give so much power and influence to party members, mean that Muslim women standing at the local level are particularly vulnerable to being blocked from standing for their party by well-connected men. This contributes to Muslim women’s enduring inequalities and the unrepresentative nature of our political system, as described by Marsh et al.

5.3 Finding three: Muslim women in Labour feel unsupported by their political party

5.3.1 No person or organization champions Muslim women’s cause in the Labour Party. Although Labour has a long and strong history of women organizing separately to ensure representation of their views within the party, with the first such organization forming in 1906 (Halcli 1996), Muslim women in the Labour Party do not have faith in the current predominant women’s organization, Labour Women’s Network (LWN), to champion their cause.

None of the interviewees were optimistic about LWN taking on the issue of the specific forms of discrimination they face and pushing for change in the Labour Party. Echoing intersectional theorists’ critiques of the feminist movement (Hooks 1981), for these Muslim women, the Labour Women’s Network has the image of being only for white women. Some felt excluded from training opportunities provided by LWN, and there was a sense that Muslim women’s situations were not fully appreciated by those involved in the organization. All of these factors combined to leave them unenthusiastic about LWN and the chance of it working to improve their experiences by supporting them against the sexist discrimination they face from Muslim men within the Labour Party. This finding supports the Asymmetric Power’s Model’s assertion that it is not only our political representatives that are not diverse, but also other political actor such as policy networks (Marsh et al. 2003).

There was a sense among the Muslim women I interviewed that people like them did not fit in with the Labour Women’s Network, although they did acknowledge that the organization had become more diverse in recent years, particularly with the election of its first black chair.

A former Labour councillor in Manchester said that ‘Labour Women’s Network is for white middle-class women’. Another Muslim woman, a councillor in London, said,

“Labour Women’s Network used to be, I think, very, very white… It seemed to me a bit like school. And my school was a private school, a girls’ private school. So, it was the feel of it. It was very much like that. Where there was the sort of well spoken, well behaved, identikit women coming off the conveyor belt to be MPs and councillors.”

The mention of class and private schools adds another dimension to these Muslim women’s feeling of exclusion from the Labour Women’s Network. As March et al. write, ‘class and ethnicity are… strongly associated with access to educational resources’. (Marsh et al. 2003: 309). These women feel like they do not fit in with the rest of the organization because of the lack of ethnic diversity within the leadership but also because it seems to them that all the other women involved are similar in their socio-economic backgrounds and the way they behave.

As discussed earlier, Muslim women are often excluded from local kinship networks that promote the interests of Muslim men and restrict Muslim women’s advancement. Some women felt that this particular aspect of Muslim women’s experiences was not appreciated within LWN. One Muslim woman complained that the advice she had been given by LWN in the past was not relevant or applicable to her situation. When I asked if she believed that the Labour Women’s Network was capable of supporting her with the problems she faced in her local Labour Party, one Labour councillor in London said,

“No, I don’t think they are capable of supporting me as a member because most of time, what you hear from them is ‘oh, you know, you have to work your way around there, or you’re going to have to put up with it or find allies’. And it’s like, you know, sometimes you can’t find allies within your own party, there’s a lack of allies within your own cause.”

For many Muslim women who are under-represented in politics, the combination of LWN’s lack of diversity and the absence of understanding of their particular experiences of discrimination means that LWN is not an organization that they trust to take on their cause with the leadership and challenge it to take action to better support them.

Muslim women similarly feel that they cannot rely on BAME Labour and Muslim Labour Network to champion their cause but for different reasons. Both organizations, although they have very different histories and leaderships, were seen by the Muslim women to be male-led, ineffective, uninterested in women’s issues and factional tools.

BAME Labour in particular was seen by one former Labour councillor as being ‘Keith Vaz’s project’ that the party leadership let the former MP rule in exchange for his support. Another interviewee, a current local councillor, when asked if she felt represented by any Labour liberation organizations, said,

“I’ve never felt represented by these organisations, specifically BAME Labour. It feels like they’re not taken seriously by the party at large, and therefore their voice doesn’t really matter... how can they represent me when their own voice as an organisation isn’t respected by the party at large?”

Muslim women’s lack of reliable allies within the labour movement demonstrates clearly the ‘double bind’ that Bell Hooks described in 1982:

“Black women were placed in a double bind; to support women’s suffrage would imply that they were allying themselves with white women activists who had publicly revealed their racism, but to support only black male suffrage was to endorse a patriarchal social order that would grant them no political voice.”

Just as black women were in a ‘double bind’ then, due to the lack of intersectional organizations in the Labour Party, Muslim women are left with the choice of joining a women’s organization that they don’t feel truly understands their experiences, or joining a male-led organization that understands their experiences, but chooses to ignore them.

5.3.2 Muslim women do not trust Labour’s complaints process. As well as not having an organization within the Labour Party to champion their cause, Muslim women also distrust the party’s internal complaints process. A number of women I interviewed had negative direct experiences of submitting complaints, usually followed by long waits before hearing of an outcome and then finding out that no action will be taken against the accused because of a lack of evidence.

One woman, a former Labour local councillor spoke of her experience submitting a complaint following sexist discrimination she faced within her local party:

“The complaint that I had submitted went on for like nearly two and a half years and I just think that it’s such an enduring thing to go through, you know, it’s like it’s just so difficult and you just want closure and you’re not getting it because people think they got away with treating you so badly in such a public way, which sends out absolutely the wrong message. It sends out [the message] that you can act without consequence, and you can do that. And I think that was so difficult … Really hard and difficult situation because these people then thought ‘oh, we can get away with this’.”

In the end, the Labour Party suspended several members involved in her complaint, but this former local councillor did not feel like she was treated well by the party. Another Muslim woman, this one a former Labour council candidate in the Southeast told me how her email complaining about unfairness and rule-breaking in her local branch was forwarded onto to the people she was complaining about and others in her local party. She said that ‘random members’ knew about her complaint and spoke to her about it when she had not spoken to anyone about it. The same woman had another negative experience of using Labour’s complaints process:

“So, I wrote to the party, and I thought the fact that you know there was…maybe one or two people who were like I thought, OK, maybe they could back me up in the end. Basically, nothing kind of came of this complaint. [The] response that was something like they either they didn’t think there was any wrongdoing or there was nothing they could do, or they couldn’t prove it, something like that… so since then, that’s when you know the behaviour’s got worse.”

In this case, there is no evidence that the Labour Party has fully understood the nature of the discrimination that Muslim women face, the effect that their intersectional societal positioning has on their ability to persuade other people to support them at witnesses, and the influence (perceived or real) that local biraderi networks have in some local Labour parties. Even when complaints are finally upheld, and action is taken against the accused, the time it takes for the process to complete means that these women can sometimes continue to live with uncertainty for years.

Others’ negative experiences serve as examples to other Muslim women who have faced discrimination and prevent them from taking action against the perpetrators of their discrimination themselves. Several women I spoke to who have experienced either racism or sexism from other members did not complain to the Labour Party. When asked if she had ever made a formal complaint, one woman answered:

“No, because it’s not worth the time and effort because it falls on deaf ears. You know [someone else has put in] a complaint. It goes to CLP, they go to Region, Region give it to National… and [you’ve] been at it for two years. And I’m thinking ‘no, I’m not wasting my time on something that doesn’t work.’ Because if the process isn’t there to work and give you an outcome, why would I want to fight for something when people don’t appreciate what I’ve done and it’s not worth my time? I’ve got better things to spend my energy and my life on and be more productive and be happier.”

Another woman was advised by someone she trusted, a union representative, not to make a formal complaint because it would harm her chances of becoming a candidate for the upcoming local elections:

“My union rep. said to me, ‘considering you want to be a councillor, don’t take it forward further because you’re just going to cause enemies for yourself and problems for yourself so just be silent about it at the moment.’ I was young, I didn’t know, like I was so new to politics and everything, I didn’t know. I was like, OK, this is how it works, I guess you should just be silent about stuff that is said to you.”

Yet another Muslim woman, this time a Labour councillor in the Southeast, spoke of her distrust of the party’s complaints process because she did not believe it was transparent and open to all. She said, ‘the problem is we know there is a systemic problem at the top of the organisation, depending on who it is and what the flavour of the week is, they will treat it [the complaint] differently’.

The Muslim women interviewed do not trust the Labour Party’s complaints processes and procedures. Those who have previously submitted complaints relating to the discrimination they have faced or rule-breaking they have witnessed have universally had negative experiences. Those who have not yet submitted complaints have been put off doing so by the experiences of others. This distrust contributes to Muslim women’s underrepresentation in two ways: by contributing to them feeling that the party does not value them, and therefore discouraging them from putting themselves forward for other positions of responsibility, and by sending out the message to those who discriminate against Muslim women that there are no consequences, leading to further discrimination.

6. Conclusion

Over twenty years since the publication of the Asymmetric Power Model by Marsh et al., British politics remain unrepresentative of the wider population. Enduring socio-economic inequalities mean that not everyone is able to access political institutions in the same way. It is time that actors within the British political system and those who study it acknowledge these characteristics of our politics and examine more closely how and why these inequalities play out in political institutions. The case of Muslim women in the Labour Party demonstrates the role that intersecting forms of discrimination, particularly racism and sexism, have in preventing and discouraging political activists from putting themselves forward for political office and the role that political parties have in fostering a political system in which inequalities are challenged rather than allowed to endure. Using interviewing and autoethnography, this paper finds that Muslim women face racism and sexism. It is also found that the discrimination that Muslim women face is often by Muslim men. The Labour Party’s embrace of male-dominated biraderi politics at the local level means that some Muslim women, who are excluded from these kinship networks, are unable to overcome the hurdle of the party’s selection processes. When Muslim women face difficulties, they do not have an organization within the party to champion their cause and negative experiences, both their own and those of others, mean that they do not have faith in the party’s complaints process so are reluctant to make formal complaints. A one-dimension analysis of inequality would not have succeeded in exposing these forms of inequality, and an intersectional framework is key to understanding how multiple forms of discrimination work together to contribute to Muslim women’s underrepresentation in British politics.

This paper shows how, beyond the actors that Marsh et al. first identified as contributing to the asymmetry of British politics, understanding the role that political parties have in perpetuating inequalities is essential if we are to have a more representative political system in the future. Furthermore, this case demonstrates that an intersectional approach is needed to fully comprehend the multi-faceted forms of discrimination that those ‘at the intersections’ face.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by Queen Mary University of London through the Principal’s Studentship Programme.