-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alfonso Martínez Arranz, Steven T Zech, Matteo Bonotti, Political Parties and Civility in Parliament: The Case of Australia from 1901 to 2020, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 77, Issue 2, April 2024, Pages 371–399, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsad008

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Incivility in parliaments is always prominently displayed in media reports, often with the implicit or explicit commentary that the situation is getting worse. This paper processes and analyses the records of verbal interactions in the Australian Parliament for over 100 years to provide a first approximation on the evolution of civility. It provides a framework for understanding the multidimensional nature of civility that examines both ‘politeness’ and ‘argumentation’, with the latter grounded in notions of public-mindedness. The analysis focuses on the interactions between parties of the orators and the party in power, the chamber of utterance, and the year. The results indicate that instances of impoliteness have increased since the 1970s but only modestly and remain highly infrequent. Minor parties, particularly those representing right-wing and Green politics are more likely to use dismissive or offensive language than the dominant centre-left and centre-right parties, although direct insults and swearwords are the particular remits of right-wing ‘system-wrecker’ parties. All these minor parties, nonetheless, also display higher levels of argumentation in their interventions. This combination of aggressive language and increased argumentation highlights the pressures on minor parties to convey their points in a forceful way, a challenge that is particularly pressing in two-party systems like the Australian one.

1. Introduction

Parliamentary debates arguably do not attract attention from the general public commensurate with their importance. Yet, when the media do cover parliamentary affairs, they often focus on instances of incivility and lament that the latter are on the rise, especially across partisan lines (Murphy, 2022). Snippets of crude name-calling and other instances of uncivil behaviour may not be entirely surprising, especially in what some view as the highly antagonistic setup of a Westminster-style parliament (Sawer, N.d.). This article turns to the empirical record and examines civility and incivility in the Parliament of Australia. Our objective is twofold. First, we provide a conceptualisation of civility, unpack its different dimensions (focusing on two of them—‘civility as politeness’ and ‘justificatory civility’), and theorise potential factors that may lead to greater incivility in parliaments. These include structural and systemic features; the broader political and social context, and issues under debate; and attributes of the actors/parties speaking in parliaments, along with their positionality and power. Second, we identify instances of incivility both in the entirety of the Hansard records and in connection with specific policy issues. For this purpose, we employ several reinforcing methods that allow us to provide a first attempt at a general assessment of the extent of civility and incivility in the Australian Parliament.

We find that expletives and open incivility—which we consider violations of civility as politeness—are relatively rare and have only marginally increased over time in the Australian Parliament. However, we also find that these incidents are concentrated among the minor parties and that these parties seem driven to use ‘offensive’ language more frequently than major ones. Furthermore, while we observe that levels of argumentation and deliberative quality in the Australian Parliament have decreased overall—testifying to a perceived diminution of justificatory civility over time—we also find that minor parties tend to provide more arguments for their positions on different policy issues than their major counterparts. We suspect that members of minor parties are using both more forms of incivility as impoliteness and more arguments in support of their preferred positions (i.e. more justificatory civility) to make up for their limited time and exposure (resulting from the marginal role they occupy in the Australian party system) compared to members of major governing parties. Following our analysis we discuss the implications of our findings.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Understanding civility

The broader political theory and philosophy literature often views the civility concept in terms of two main dimensions: civility as politeness and civility as public-mindedness (Bardon et al., 2023).

Civility as politeness can be seen as a virtue tied to compliance with etiquette, good manners, and certain protocols. Derek Edyvane, for example, suggests that ‘civility is bound up with the idea of what it means to be civilised, to be well-mannered or polite; its focus is on standards of behaviour in our dealings with others in everyday life’ (2017, p. 345). Likewise, Cheshire Calhoun refers to ‘polite civility’, which ‘has been understood as the mark of the competent participant in the social settings of everyday life’ (2000, p. 257). In line with these points, the politeness dimension of civility can be seen as a feature of speech or action that involves adhering to certain social norms that prescribe appropriate modes of exchange and interaction (Bonotti and Zech, 2021, p. 39). In the context of parliaments and party politics, civility as politeness might involve refraining from using words and actions that cause offence. These could include insults, swear words, and dismissive or denigrating behaviour.

Civility as public-mindedness is more onerous than civility as politeness. Unlike the latter, it moves beyond adhering to politeness norms, demanding more from citizens and politicians. More specifically, it entails displaying respect for others as free and equal members of society and showing a commitment to liberal political values and institutions (Macedo, 1992; Meyer, 2000; Rawls, 2005; Boyd, 2006) . In addition to refraining from such extreme behaviours as violence, discrimination, and hate speech (Bardon et al., 2023), which constitute blatant (and, in parliamentary debates in established liberal democracies like Australia, very rare) violations of moral liberal democratic norms—i.e. moral incivility—this commitment can also be displayed by providing justifications for the political positions and policy preferences that one advocates, rather than simply asserting them. As Joshua Cohen suggests, this type of civility—which we refer to as justificatory civility—does not concern politeness and ‘how we talk to our friends or students or members of our neighbourhood or church or union or company’, but rather politics and ‘how we ought to argue with others on basic political and constitutional questions’ (2012, pp. 119–20). We focus on this specific aspect of civility as public-mindedness given the central role that communicative practices of justification play in the context of parliamentary debates.

Some scholars contend that to be civil in this justificatory sense means to comply with the demands of public reason by appealing to political values such as individual rights and liberties, equality of opportunity, and the promotion of the common good, and by grounding one’s proposed policies in ‘the methods and conclusions of science when these are not controversial’ (Rawls, 2005, p. 224). Others, however, may set the bar lower, suggesting that simply providing reasons—public or not—is sufficient for public justification, as what matters is the deliberative quality resulting from the very exchange of reasons. As Quong points out,

some critics argue that public reason is not the only way, and perhaps not the best way, to show respect for others, or show civility, when engaged in moral and political dialogue. There are equally plausible conceptions of respect and civility which favor presenting others with the whole truth [e.g. non-public reasons such as religious arguments] as we see it when engaged in moral or political debate, rather than restricting ourselves to shared or common reasons. If this is true, then those who ground their moral or political arguments only in religious or otherwise nonpublic reasons are not being unreasonable or disrespectful: they are simply following a different, but equally plausible, interpretation of what respect or civility requires (2022).

Given the span of time and potential argumentative positions covered in this paper, we remain agnostic as to whether justificatory civility requires appealing to public or non-public reasons to justify political arguments. Instead, our focus is on reason-giving per se. Alongside respect, listening and open-mindedness, reason-giving is a key norm of deliberative quality (Drury et al., 2021) and of justificatory civility. It requires that we do not simply assert our political positions but also provide justifications for them. And while defenders of public reason believe that deliberative quality is maximised when reasons are public, reason-giving itself, even when non-public, constitutes a baseline for deliberative quality. In the remainder of the paper, we will use the term deliberative quality to refer only to its reason-giving component, understanding the latter in a baseline—or minimal—sense.

2.2 Civility in parliaments

Instances of civility and incivility manifest in various ways in political contexts (Stryker et al., 2016), including in interpersonal exchanges among citizens as well as through public-facing words and actions (Muddiman, 2017). Uncivil political discourse might appear in campaign advertisements as well as within the broader media landscape including blogs, talk radio, and cable news (Sobieraj and Berry, 2011). Political actors at the highest levels are certainly not immune from using uncivil speech and behaviour, with some US Presidents exhibiting more name-calling behaviour than others (Coe and Park-Ozee, 2020). Existing empirical research suggests that incidents of incivility permeate down the ranks and that these kinds of words and actions from politicians could alienate the public, even among their own political supporters (Frimer and Skitka, 2018). Uncivil political behaviour can reduce citizens’ level of political participation (Otto et al., 2020) and can lower public trust in some cases (Van’t Riet and Van Stekelenburg, 2022). The way arguments are presented—in terms of communicating respect and providing justifications for political positions—is essential for trust and for persuading constituents (Goovaerts and Marien, 2020). The tone and content of exchange by politicians and parties in parliaments can have far-reaching consequences. These potential negative effects, however, beg the question as to why we see more or less incivility among politicians.

In this paper, we focus specifically on the political context of parliaments, where we suspect a range of factors may condition civility and incivility. Political parties are central actors in parliaments and they merit focus given their key role in structuring political action within democratic institutions (Rosenblum, 2008). Parliaments can be regarded as ‘communities of practice’ with often highly regulated expectations and codes of conduct (Harris, 2001). Deviations from these standards, in the form of incivility, might include relatively banal provocations like impolite words between opposing party members, as well as more offensive speech that can potentially violate the more demanding norms of civility as public-mindedness. Factors contributing to greater civility or incivility can be structural or systemic (Kettler et al., 2021). For example, party competition where parliamentary proceedings are more adversarial—even of a ‘gladiatorial’ nature—might foster incivility, especially when coupled with issues like gender (Sawer, N.d.; Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2016).1 Furthermore, factors related to whether the exchanges take place in different chambers may influence incivility (Jenny et al., 2021; Schraufnagel et al., 2021). More generally, the high stakes and intense, all-encompassing competition that characterise two-party systems driven by a winner-takes-all logic are likely to increase inter-partisan incivility, since partisans from different parties will often view and treat each other as enemies rather than competitors, a process that can sometimes even result in ‘partisan warfare’ (Kalmoe, 2020). Conversely, in more pluralist party systems where coalition governments are the norm, the frequent need for partisans to interact, compromise and join forces with their counterparts from other parties can incentivise civil behaviour, including among at least some minor parties, i.e. those which have the potential of joining a coalition government (Bonotti and Nwokora, 2021).

The latter point helps us to introduce a distinction important to the remainder of our analysis. While we suspect that the size of different parties can play a role in explaining different levels of (in)civility in different parties, another key element is the relevance of a party in a party system. As famously argued by Sartori (1976), a party can be considered relevant when it has a credible potential to be in government—either on its own or within a coalition—or to influence other parties’ strategies via the threat of electoral losses. We believe that whether a party is relevant or irrelevant (all else being equal, including size) can influence its commitment to civility. Irrelevant parties’ marginal role in a party system, that is, may incentivise them to be louder and more disruptive of civility norms than if they were more invested in inter-party relations. Crucially, and to stress again the distinction between size and relevance, a smaller party in a multi-party system can potentially be more relevant than a larger one in a two-party system, given the different structures and dynamics that characterise the two different party systems.

In line with this point, for our particular case of Australia’s two-party system, we suspect that minor parties—which, in addition to having very few MPs, are also irrelevant since they are very unlikely to ever participate in or influence government—are more likely to deploy incivility to amplify their voice through provocation and to generate publicity because these kinds of statements in parliaments are newsworthy. We also hypothesise that minor parties will use more arguments to make the most of their speaking time and gain further attention, and to signal their seriousness and competency through the use of argumentation and reason-giving, which are indicators of deliberative quality. Furthermore, many minor parties are particularly vocal on specific issues (e.g. Green parties focused on the environment) and will likely have the competencies and the incentives to provide greater argumentation when speaking in parliament about those specific issues.

The social, economic, or political context of the time may also help us to understand why we see higher and lower levels of incivility in parliaments. Particular contentious events could set the scene for more polarised exchanges between political actors and parties. What happens in the world around us affects what happens in the parliamentary context (Peele, 2022). We suspect that the prevalence of perceived injustices, global instability, climate crisis, and war could all contribute to heightened tensions and more frequent provocations in parliaments. In terms of deliberative quality, we also suspect that when things are going well there will be greater indifference around policy change, a higher degree of consensus, and less of a need for detailed arguments. An exception might be when issue-based minor parties continue to advocate vocally around a particular point.

The issues raised in parliaments themselves may also play a significant role in affecting levels of civility and incivility. Some topics or themes are more controversial than others. The degree of contentiousness surrounding certain issues may affect the way politicians and parties speak about them. Even parliaments often characterised by ‘moderation and tolerance’ can exhibit significant combativeness around particular issues like immigration (Wyss et al., 2015). Likewise, discussions about gun violence in the United States can provoke impolite exchange and extremely charged rhetoric (Hollihan and Smith, 2014). Countries may have their own distinct policy issue pathologies that generate more instances of uncivil exchange, and more complex issues will likely require greater argumentation when they are brought up for discussion and debate.

Attributes of individual politicians or their parties may also influence civility and incivility in parliaments. Personality or individual characteristics might affect the degree or form of incivility. Specific high-profile leaders can become ‘the intemperate embodiment of extreme partisanship’ and come to exhibit ‘arrogant self-promotion, angry assaults on political adversaries, and rank hypocrisy’ (Brattebo, 2013, pp. 47–48). These forms of incivility expressed through individual actions can set the tone for entire parties. This can be problematic, as upholding expectations of civil exchange around specific issues and the quality of debate are often inherently tied to parties (Wyss et al., 2015; Cox, 2022). Furthermore, the tone or sentiment expressed in policy debates may be linked to the opposition status of a party (Louwerse et al., 2021) or their ideological distance from a median position on an issue (Schraufnagel et al., 2021). We suspect that fringe parties and some far-right parties that emerge as ‘system wreckers’ may be more uncivil because they are disruptive spoilers seeking to exert influence disproportionate to their party size and their low (or absent) relevance. They might also exhibit greater obstinance and a refusal to compromise with other parties on specific issues as a general principle (Wolf et al., 2012), and provide more arguments to make the most of their speaking time as well.

Finally, the positionality and the distribution of power among parties may also affect civility and incivility in parliaments. Relationships between parties, along with levels of polarisation between them, can influence the nature of interpersonal and interpartisan conflict as well as subsequent legislative outcomes (Dodd and Schraufnagel, 2012). For example, recent research suggests that levels of democracy and the composition of parliament can influence the likelihood of more extreme acts of incivility like physical altercations between politicians—fragmented parliaments and chambers with slim majorities are more likely to see physical altercations (Schmoll and Ting, 2022). Where parties stand in relation to others and the power they hold at any specific time (e.g. whether they are in government or not) are also likely to influence their actions in parliament. A dominant party may not need to adopt direct or aggressive tactics in the same way as a minor party with low representation. Furthermore, we suspect that some minor parties may be characterised by a greater ideological distance from dominant parties in government, increasing not only the likelihood of impoliteness but also the levels of argumentation, given the lack of shared grounds with their dominant counterparts and the resulting need for them to better explain the reasons underpinning their political positions.

This paper will focus on parliamentary exchange in the Australian context to assess whether the issues under debate, as well as characteristics of the actors/parties speaking, have an influence on incivility. In our analysis, we remain mindful of the key events and context in which the exchanges take place, including party positionality and the distribution of power.

3. Data and methodology

3.1 Hansard records and their processing

We collected the entirety of Australian Parliament Hansard records as available on the Parliament’s website from 1901 until 2020. Note that, for more recent records (post-1980), the Parliament’s website contains the full text of Committee documents and Reports, stored as separate ‘databases’; however, we focus on the databases ‘House Hansard’ and ‘Senate Hansard’ which overwhelmingly consist of oral, interactive and often spontaneous interactions on the floor of Parliament. Our intention is to exclude any material that may have been sanitised of incivility (such as bills and committee reports).

Our data collection and processing consisted of automated queries to the Parliament website that obtain document metadata in comma-separated values (CSV) format in monthly intervals. These metadata include date, name and party allegiance of the main orator and potential interjectors and respondents. They also contain a ‘permalink’ to the full text of the document, which we used to automatically download the text. Overall, we captured over 1.2 million documents, which we standardised into more than 2.5 million paragraphs or sections. Each of these sections is spoken by only one of 1772 orators.

During the initial processing, we carried out a basic level of filtering, removing overly short documents and procedural interventions by the speaker (i.e. ‘the room will now come to order’). We also note that the two Hansard databases may contain some statements ‘committed to the Hansard’ in written form already, and enumerations of legislation or other documents. These may be mixed in with the oral exchanges in some categories of intervention sometimes labelled ‘Documents’, etc. To control for the impact of these documents, we contrast our findings against the subset of the documents that are either (i) bill readings or (ii) Question Time transcripts, i.e. the most traditional oral interactions on the floor of Westminster-style parliaments, which correspond to about 63% of the 2.5 million paragraphs.

3.2 Specific topics

To enable a more grounded understanding and to tease out potential differences by theme, we searched for text containing words relating to specific topics that are (or have been) controversial and are covered in the automated text classification models we use in our methodology (Stab et al., 2018). Three topics directly matched this requirement, namely: reproductive rights (shorthand ‘abortion’), drug addiction, and nuclear power. In addition, we added similar topics that have been addressed more consistently throughout Australian parliamentary history, such as coal—an energy source that, like nuclear, has been both defended and maligned—and Aboriginal affairs, with their connection to rights. Finally, after a first analysis showing the increase in ‘aggressiveness’ of the opinions of Greens and right-wing parties over time, we added the ‘renewables’ topic.

The distribution of each topic is diverse but in all cases sufficient for extensive analysis:

Aboriginal: 861,629 sentences2

Abortion: 39,439 sentences3

Coal: 1,178,449 sentences4

Drugs: 42,003 sentences5

Nuclear: 299,672 sentences6

Renewables: 138,670 sentences7

3.3 Party families and government in power

Many parties exist in the Australian political landscape but the two major players are a centre-right conservative ‘Coalition’—made up of a mainly urban Liberal Party of Australia and a mostly rural/regional National Party of Australia—and the centre-left Australian Labor Party (ALP). The Coalition and its historical predecessors (which included the Protectionist Party and the Free Trade Party) and the ALP have been the only political forces to form governments and hold cabinet positions since 1901, and those which have dominated the Australian Parliament. However, particularly in recent times and in the Senate (the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives), they have been joined by a range of minor parties which, aside from the Greens, we group into broader ‘families’ of centre, independent and right-wing.8

4. Identifying incivility

Providing an overview of the civility and incivility of the millions of utterances contained in the Hansard is a task best suited to quantitative methods. We focused our analysis on two key dimensions of civility: politeness and public-mindedness. More specifically, we aimed to identify instances of incivility as impoliteness as well as levels of deliberative quality, the latter being an indicator of justificatory civility.

4.1 Incivility as impoliteness

Incivility as ‘impoliteness’ often manifests itself in the form of ‘offensive’ language, e.g. the use of insults and accusations of incompetence or corruption, which can be identified by a set of words that are unequivocally uncivil. We use two main vocabularies that capture this type of incivility:

dismissive and denigrating (e.g. ‘disgrace’, ‘embarrassment’, ‘outrage’, ‘ridiculous’, ‘scandal’, etc.)

insults and swear words (e.g. ‘imbecile’, ‘stupid’, ‘dumb’, ‘fuck’, etc.)

The vocabulary lists were compiled by the authors from the ‘bad words’ list at Carnegie Mellon University (von Ahn, N.d.). This list comprises 1383 English terms and it is taken to be a rather exhaustive list from which to capture dismissive or insulting terms likely to appear on the floor of the Australian Parliamentary chambers. The full curated categories for analysis included:

dismissive <- c(‘disgrace’, ‘embarrassment’, ‘outrage’, ‘ridiculous’, ‘a joke’, ‘shame’, ‘scandal’, ‘ridicule’, ‘laughable’, ‘silly’, ‘nonsense’, ‘drivel’, ‘blather’, ‘bunkum’, ‘rigmarole’, ‘piffle’, ‘trash’, ‘bladerdash’, ‘twaddle’, ‘malarkey’, ‘babble’, ‘gibberish’, ‘prattle’, ‘gimcrackrey’, ‘ludicrous’, ‘folderol’, ‘junk’, ‘jabber’, ‘absurd’, ‘madness’, ‘folly’, ‘hocus-pocus’, ‘nonsensical’)

insults_swearwords <- c(‘moron’, ‘dickhead’, ‘shithead’, ‘imbecile’, ‘slimeball’, ‘wanker’, ‘retard’, ‘retarded’, ‘fuckhead’, ‘stupid’, ‘dipshit’, ‘idiot’, ‘asshole’, ‘arsehole’, ‘bastard’, ‘dumb’, ‘fool’, ‘fucking’, ‘fuck’, ‘bugger’, ‘fucken’, ‘fucked’, ‘slut’, ‘shit’, ‘bullshit’, ‘crap’, ‘shite’, ‘turd’)

Searching for these vocabularies directly allows us to accurately determine the evolution of this subset of incivility.

We also apply a sentence classification model that determines whether a sentence contains potentially offensive language and accusations. Sentence classification models are machine learning tools trained on human-labelled data. These models are capable of labelling previously unseen data based on the patterns they uncover within their training data. We use the ‘transformers’ Python library to apply off-the-shelf models to our own data (Wolf et al., 2020). For offensiveness/aggressiveness, some of the most advanced sentence classification models rely on Twitter data given that the latter are easily accessible and have been thoroughly labelled. We adopted the most widely used transformer model: ‘cardiffnlp/twitter-roberta-base-offensive’ (Barbieri et al., 2020).

The model was externally trained and thus would have, if any, different biases from our vocabularies above, so it serves as a good test of the outcomes. Some sample sentences that have been identified as ‘offensive’ by this classification model are shown below:

the government is picking winners and mucking around with the market.

[name of MP] is reported to have told colleagues that the liberals are now widely regarded as homophobic, anti-women climate-change deniers.

this sort of debate is not helped by the stupid intervention of the honourable member for north Sydney.

[name of Senator], in particular, has been vilified and calumnied very widely as being either a knave or a fool – a knave to the extent that, whatever she might have been pretending to say by way of justification for her position, really she was in favour of a massive extension of abortions through the agency of private abortion clinics.

so, once again, there is this condescending and just disgusting attack on their capabilities, which I find absolutely inconsistent with this whole argument.

this anti-semitic nonsense parades under the banner of Christianity.

I think that really highlights the hypocrisy.

such procedures are undemocratic and unfairly place people between a rock and a hard place

It is worth noting that neither method—i.e. direct search or sentence classification model—can distinguish between an orator who is being offensive themself and one who is simply attributing offensive language, attitudes or behaviour to others. Nonetheless, the use of offensive language in either direct or reported way indicates a greater potential for somebody to wind up offended and, more generally, an increase in the level of impolite offence in the Australian Parliament.

4.2 Argument levels

As with offensive terms, we deploy another sentence classification model that identifies arguments, understood as a generic ‘reason-giving’ to support a particular point in a debate. For this sentence classification, we use the ‘chkla/roberta-argument’ model, which is well adapted to our particular types of arguments having been trained on relevant topics (Stab et al., 2018). Note that, for the purposes of our paper, these arguments are not assessed as good or bad. Some examples are provided below:

But to say to small business that, because there has been that sort of disagreement within the coalition ranks, you cannot have the amendments to strengthen the trade practices act—which the government actually agrees with—is, I think, rather spiteful.

The investment will target the high levels of overcrowding in remote NT and will provide jobs and apprenticeships for local indigenous people.

The survey found that 92% of respondents were opposed to abortion due to the sex of a child, with only 6% being in favour.

This would not have been possible had they not been reliant significantly upon nuclear power. The uranium information centre has predicted that, within the next 15 years, current infrastructure used to generate power is going to have to be replaced.

This bill will allow the cultivation of cannabis for medicinal purposes while remaining compliant with Australia’s international obligations.

It is a plan that will kill investment in renewables in this country—investment that requires long time horizons, long-term contracts and long-term certainty.

A conscience clause enables medical practitioners to elect not to participate in the abortion.

Despite our filtering, there may be a large amount of ‘boilerplate’ language, i.e. introductions to the business of law-making and issues only tangentially related to the specific topics we hoped to identify. Hence, we focus only on sentences that contain specific terms relevant to each topic as denoted above. The filtering reduces the number of sentences to 10–25% of the original.

4.3 Statistical models

We build two types of models depending on the outcome variable:

Linear models for the frequency of dismissive/offensive words

frequency = month_id + month_id + chamber + party_family + government (+ topic)

2. Logistic for the binary outputs of our text classification models (offensive/non-offensive or argumented/not-argumented)

Classification [e.g. ‘offensive’ or ‘not-offensive’] = decade_id + chamber + party_family + government (+ topic)

where:

frequency is one of the two frequencies of either dismissive words or insults/swear words per thousand words

classification is one of the two binary classifications of the sentences (as argument/non-argument and as offensive/not-offensive)

month_id is the month number starting in January 1901

decade_id is the decade in which the speech took place

chamber is either House or Senate

party_family is Coalition, Labor, Greens, independents (ind.) centre, and right-wing parties

government: is either a Coalition or Labor government

topic: are the six outlined above

As can be deduced, the models control for time either through decadal fixed effects (in logistic regressions) or with polynomial terms for monthly effects (in linear models), and include all potential variables of interest. The full results of all regressions are available in a table in the Appendix. We use graphs to illustrate the most interesting effects throughout the results sections.

5. Results

Our results are consistent across the various methods. We see that Greens and minor right-wing parties display a higher proportion of ‘offensive’ language than other parties; however, they also couple this with higher levels of argumentation. A possible interpretation is that the Greens and right-wing minor parties—and, to a lesser extent, other minor parties—share a commitment to ‘shaking up’ the establishment. With a relatively limited representation in Parliament and hence speaking time, and given their irrelevance (in Sartori’s sense), they need to make their interventions as impactful as possible. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the Greens have a below average use of expletives, while right-wing minor parties display a well above average rate. This may be due to the need for them to make strong points within a limited time allotment, not least to attract outside attention. For some extreme right-wing parties, their identity as ‘system-wreckers’ lends itself to this kind of language, more so than for the Greens or other types of minor parties.9

Our results also show that the overall level of incivility—understood as offensive impoliteness—in the Australian Parliament is limited and, despite a tripling since the 1970s, has remained relatively low.

5.1 Dismissive and insulting language

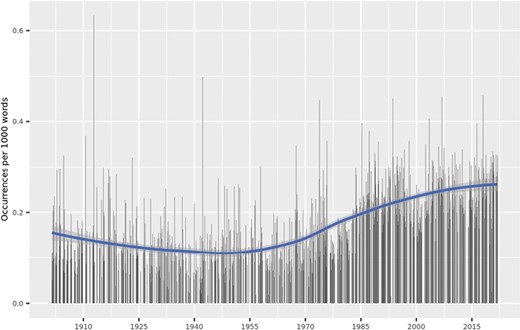

The perception of increasing offensive language in Parliament is somewhat reflected in the raw data as displayed in Figure 1. However, the most recent levels are neither unprecedented nor overall very large, peaking at around 0.45 words per thousand in various months in the early 1970s, which coincided with the tensions surrounding the Vietnam War.

Frequency of dismissive language in occurrences per 1000 words across the entire Hansard document sample.

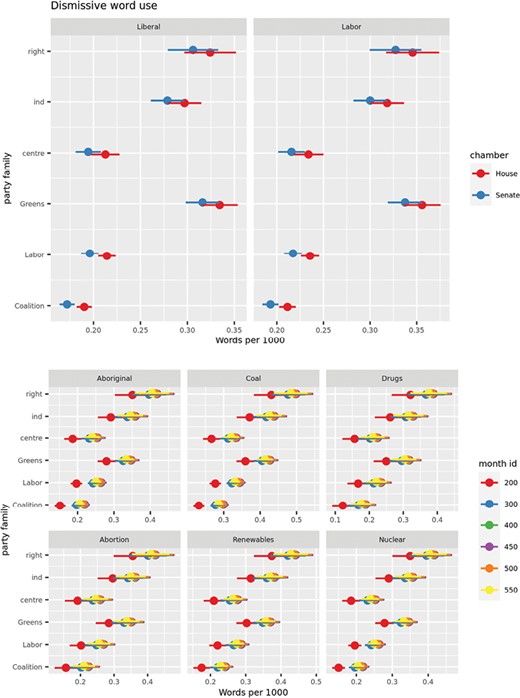

5.2 Dismissive language

Looking at the results of the statistical modelling in Figure 2, the frequency of dismissive language is clearly higher in the minor parties than in the two major ones, and there are differences between the House and the Senate, as well as between periods of Labor government and Coalition government. More specifically, the Senate displays slightly less dismissive language in comparison to the House. This seems to confirm one of our earlier hypotheses. Unlike the House, which uses instant-runoff voting (also known as preferential voting or alternative vote)—a type of majority rule electoral system—to elect its members, resulting in the dominance of two main parties, Labor and Coalition, members of the Senate are elected via single transferable vote with proportional representation. This electoral system produces a more diverse chamber, therefore granting a more important role (in terms of speaking time and balance of power) to minor parties and independents, which reduces the need for them to use dismissive language to get their point across. Relatedly, it is also plausible to speculate that the more significant role played by minor parties in the Senate than in the House may also increase, from time to time, the government’s need to obtain support from non-government MPs in the former chamber to secure parliamentary majorities. This may incentivise more polite and non-dismissive language in order to facilitate interaction and cooperation. If and when that is the case, and even though this was not part of our findings, it is also plausible that government MPs may display more polite behaviour towards the specific MPs (whether affiliated with a minor party or independents) whose support is perceived as crucial for the government’s stability than towards others.10 The increase of dismissive language over time is also significant but it is worth noting that the increase in the presence of minor parties also takes place towards the end of the period considered.

Predicted values from model on frequency of dismissive word use.

5.3 Insulting language

In terms of purely insulting language, all party families present low levels. However, right-wing parties display double the mean expected frequency compared with mainstream parties (0.16/1000 vs 0.08/1000) and the Greens are the lowest overall, unique among minor parties for using insulting language less frequently than the two mainstream parties. This seems to corroborate the widespread (self-)perception of Australian minor right-wing parties as expressing anger against mainstream politics in the country. Note that the frequency of insulting language use among minor right-wing parties is somewhat higher during Labor party governments.

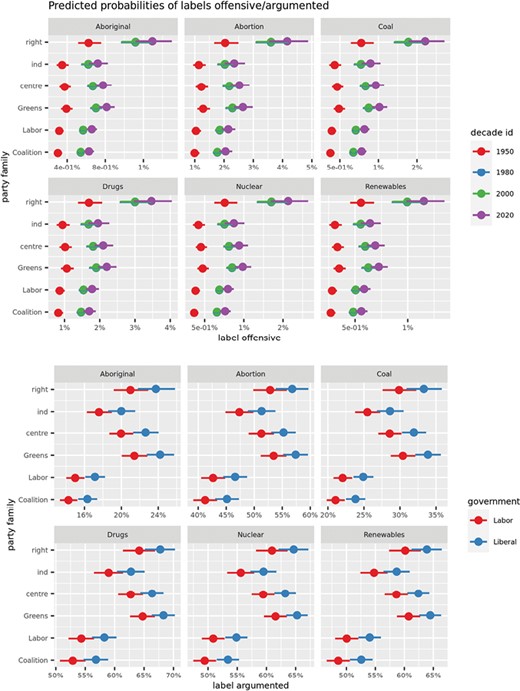

Figure 3 shows that the offensive sentence classification model largely supports the above findings but combining the two: Greens are only slightly above the others, and we do observe more offensive language coming from the right.

Predicted probabilities of label offensive in our offensive text classification model.

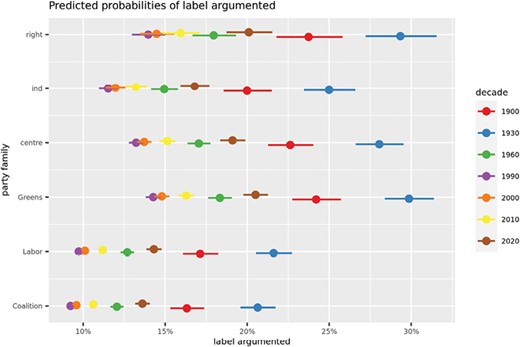

5.4 Deliberative quality

In terms of deliberative quality, assessed by measuring the level of argumentation, a reduction trend seems to have bottomed out in the late 1990s. This trend might be due to changes in parliamentary debate regulation producing different numbers of sentences available for analysis per decade, though we were unable to find evidence for this.11 However, even if that were the case, differences between parties are still evident in each specific decade. More precisely, model results again single out minor parties, which score higher than the two traditional government parties. These results control not only for time but also for party in government and chamber venue. Figure 4 showcases that this is particularly true for the Greens and for minor right-wing parties.

Predicted probabilities of label ‘argumented’ (attempting to give reasons) in our argumentation text classification model.

5.5 Variation across different topics

Different topics seem to generate clear differences in levels of argumentation, which correlate strongly with topic size and complexity. The broader/more complex the topic, the higher the need to contextualise it and present generic information, rather than simply asserting a point.

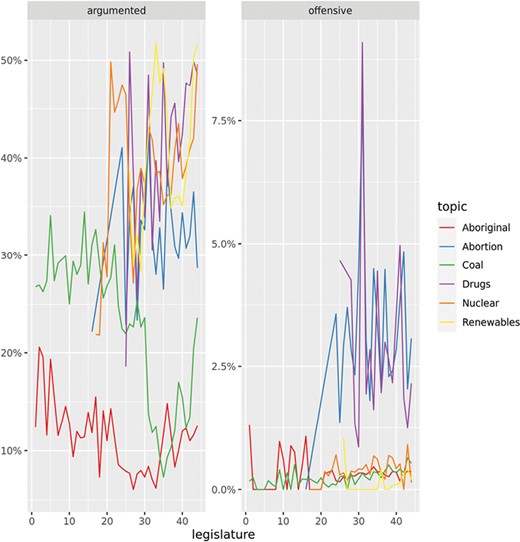

Figure 5 shows the proportion of sentences that were identified as ‘argumented’ (containing arguments) and offensive by the classification algorithms. The graph below displays the proportions of dismissive language and insults/swearwords. To ensure relevance, we have removed topics that did not have at least 30 mentions in each legislature, leading to the exclusion of more ‘modern’ topics from earlier legislatures.

Percentage of sentences in each topic classified as ‘argumented’ or ‘offensive’ by their respective algorithms.

The most salient insights from the left panel in the first figure are that Aboriginal matters are overwhelmingly discussed in a tokenistic way compared to other topics. This seems to fit with ‘Aboriginal issues’ being acknowledged rather than acted upon. It is also notable that the coal-related discussion lost a fair amount of its argumentative power later on.

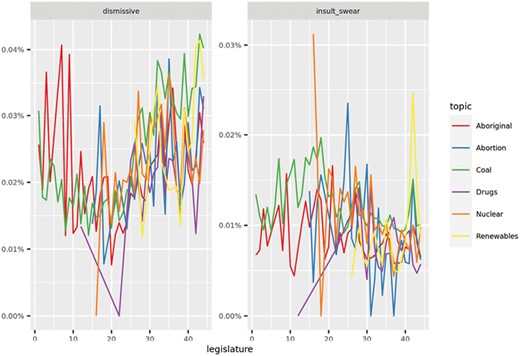

In terms of aggressiveness of the discussion, abortion and drugs present a significantly higher level of offensive language use, albeit still rather limited. However, this contrasts with a very limited use of unambiguously dismissive and offensive words from our lists, as shown in Figure 6.

Percentage of occurrence of insults and swearwords in each topic.

Upon closer inspection, the discrepancy is the result of frequent description of the potential trauma and difficult circumstances of these two activities, often in terms of either ‘repulse/disgust’ or ‘insensitivity’, which arguably speak to a different category of civility, i.e. whether an individual feels repulsed by others’ actions even if they do not directly affect the individual. For example, in the case of abortion:

‘I firmly believe that abortion should not be used to shame women or make women feel guilty’.

‘to suggest that a pregnancy should be terminated simply because of the sex of the child—because the parents wanted a child of the other sex—is just repugnant and repulsive’.

‘we have seen these cruel, insensitive antics by senator [omitted] before’.

6. Discussion and conclusions

Our empirical findings confirm many of our original hypotheses regarding the use of civil and uncivil language in the Australian Parliament. Our most significant finding is that there are key differences between minor and major parties regarding both the frequency of offensive impolite language and the degree of deliberative quality. More specifically, minor parties, and particularly the Greens and minor right-wing parties, are more likely to use dismissive language towards their opponents, and right-wing parties also display a significantly higher use of insulting language than any other parties. We also found that, at least in the case of minor right-wing parties, the frequency of offensive impolite language is higher under Labor governments, suggesting that ideological distance can incentivise impoliteness. There are some differences between the data for the House and those for the Senate, with the level of offensive speech being generally higher in the former chamber, where minor parties have a weaker presence (due to the electoral system employed to elect its members) and therefore need to amplify their message via either dismissive and/or insulting language. Furthermore, we found that the level of deliberative quality, as manifested in the degree of reason-giving, is also higher among minor parties. We suspect that this may be due to the fact that such parties need to maximise the limited presence and time they have to speak in Parliament. Since their views on different policy issues may be less widely known than those of the major parties, minor parties need to articulate their views by providing a higher proportion of reasons and arguments than their major counterparts.12

Finally, our finding that incivility as impoliteness is more frequent among minor parties also points to another important aspect of civility and incivility. The norms of decorum and etiquette associated with civility as politeness are sometimes viewed as a tool for maintaining the status quo and perpetuating the oppression, silencing and exclusion of minority and marginalised voices (Elias, 1969; Freud, 2004; Bejan, 2017). Therefore various forms of ‘incivility as dissent’ (Edyvane, 2020), ‘uncivil disobedience’ (Delmas, 2018) or ‘disruptive speech’ (Goodman, 2018), which challenge established norms of decorum and etiquette, may sometimes be permissible or even desirable. For example, by expressing a sense of injustice towards established social norms, structures and institutions, and advocating for those individuals and groups that are ‘denied full and equal status’ (Delmas, 2018, p. 63), these instances of incivility as impoliteness can advance ideals associated with civility as public-mindedness. Likewise, in her critique of civil political communication, Iris Young points out that ‘[t]o the extent that norms of deliberative democracy oppose disorderly, demonstrative, and disruptive political behaviour or label a certain range of positions extreme in order to dismiss them, such norms wrongfully exclude some opinions and modes of their expression’ (2002, p. 48). While we are aware of these critiques, we remain normatively agnostic about them in this paper. More specifically, our goal is not to normatively evaluate the justifiability of instances of (in)civility in the Australian Parliament but to empirically examine the frequency of such instances over time and their distribution between different political parties. We suspect that the critical use of incivility may be more frequent among Green MPs than among MPs from minor right-wing parties, given that at least some of the latter parties’ policies tend to deny the free and equal status of certain members of society—a non-public-minded goal which, in fact, may often be the very target of Greens’ uncivil tactics. However, hypotheses like these would require further investigation in future research.

Appendix

The following contains the results from all the models

| Data subset . | Bills and questions . | All sentences . | Topics . | All . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: . | Argument . | Offensive . | Argument . | Offensive . | Bad language . | Dismissive language . | Dismissive language . | Polarity . |

| Regression (type of dep. variable) . | Logistic (labels) . | OLS (frequencies) . | ||||||

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . | |

| month_id | −0.0001*** (0.00003) | 0.0003*** (0.00003) | 0.001*** (0.0001) | |||||

| I(month_id2) | 0.00000*** (0.00000) | −0.00000*** (0.00000) | −0.00000*** (0.00000) | |||||

| governmentLiberal | 0.057*** (0.005) | 0.037 (0.023) | 0.159*** (0.008) | 0.045* (0.017) | −0.013*** (0.003) | −0.021*** (0.004) | −0.007 (0.006) | −0.002 (0.001) |

| chamberSenate | −0.101*** (0.005) | −0.059* (0.022) | −0.046*** (0.008) | −0.037 (0.017) | −0.018*** (0.003) | −0.018*** (0.004) | −0.014 (0.006) | |

| party_familyLabor | 0.013* (0.005) | 0.020 (0.022) | 0.058*** (0.008) | 0.046* (0.017) | −0.0001 (0.003) | 0.024*** (0.004) | 0.045*** (0.006) | −0.004*** (0.001) |

| party_familyGreens | 0.329*** (0.010) | 0.266*** (0.047) | 0.493*** (0.015) | 0.261*** (0.034) | −0.003 (0.007) | 0.144*** (0.009) | 0.128*** (0.012) | −0.017*** (0.001) |

| party_familycentre | 0.296*** (0.012) | 0.197** (0.055) | 0.405*** (0.017) | 0.213*** (0.040) | 0.010 (0.006) | 0.023** (0.007) | 0.035** (0.011) | −0.008*** (0.001) |

| party_familyind. | 0.174*** (0.018) | 0.111 (0.080) | 0.248*** (0.027) | 0.138 (0.061) | 0.018* (0.007) | 0.107*** (0.009) | 0.139*** (0.017) | −0.004 (0.002) |

| party_familyright | 0.342*** (0.027) | 0.822*** (0.091) | 0.468*** (0.042) | 0.729*** (0.069) | 0.078*** (0.011) | 0.134*** (0.014) | 0.199*** (0.024) | −0.018*** (0.004) |

| topicAbortion | 0.952*** (0.017) | 1.345*** (0.054) | 1.439*** (0.023) | 1.197*** (0.041) | 0.005 (0.017) | −0.020*** (0.002) | ||

| topicCoal | 0.481*** (0.006) | 0.293*** (0.026) | 0.472*** (0.010) | 0.220*** (0.019) | 0.080*** (0.006) | −0.008*** (0.001) | ||

| topicDrugs | 1.240*** (0.015) | 0.974*** (0.056) | 1.909*** (0.022) | 1.008*** (0.042) | −0.030 (0.015) | −0.049*** (0.002) | ||

| topicNuclear | 0.953*** (0.008) | 0.102 (0.040) | 1.771*** (0.010) | 0.193*** (0.028) | −0.001 (0.008) | −0.022*** (0.001) | ||

| topicRenewables | 1.140*** (0.009) | −0.088 (0.053) | 1.737*** (0.014) | −0.117** (0.040) | 0.023 (0.011) | 0.003 (0.001) | ||

| decade_id1910 | 0.064 (0.036) | 0.605 (0.263) | 0.298*** (0.055) | 0.284 (0.199) | −0.0005 (0.005) | |||

| decade_id1920 | 0.063 (0.033) | 0.495 (0.254) | 0.288*** (0.050) | 0.333 (0.181) | −0.011 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1930 | 0.132*** (0.034) | 0.880** (0.244) | 0.288*** (0.049) | 0.635** (0.172) | 0.001 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1940 | 0.123*** (0.029) | 0.849** (0.227) | 0.402*** (0.042) | 0.563** (0.155) | −0.002 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1950 | −0.087** (0.029) | 0.671** (0.227) | −0.080 (0.042) | 0.379 (0.156) | 0.011** (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1960 | −0.308*** (0.029) | 0.838** (0.223) | −0.352*** (0.042) | 0.566** (0.150) | 0.005 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1970 | −0.407*** (0.028) | 1.097*** (0.217) | −0.616*** (0.040) | 0.859*** (0.144) | −0.010** (0.003) | |||

| decade_id1980 | −0.327*** (0.027) | 1.157*** (0.217) | −0.600*** (0.040) | 0.964*** (0.143) | −0.009* (0.003) | |||

| decade_id1990 | −0.316*** (0.027) | 1.228*** (0.215) | −0.651*** (0.039) | 1.026*** (0.142) | −0.001 (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2000 | −0.201*** (0.027) | 1.125*** (0.215) | −0.609*** (0.039) | 0.966*** (0.142) | 0.001 (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2010 | −0.053 (0.026) | 1.357*** (0.215) | −0.496*** (0.039) | 1.131*** (0.142) | 0.011** (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2020 | 0.076* (0.029) | 1.221*** (0.222) | −0.213*** (0.042) | 1.114*** (0.146) | 0.013** (0.004) | |||

| Constant | −2.076*** (0.027) | −6.509*** (0.217) | −1.794*** (0.040) | −6.223*** (0.143) | 0.119*** (0.006) | 0.086*** (0.008) | 0.008 (0.014) | 0.092*** (0.003) |

| Observations | 1,611,653 | 1,611,653 | 593,482 | 2,559,862 | 90,351 | 90,351 | 69,133 | 593,482 |

| Data subset . | Bills and questions . | All sentences . | Topics . | All . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: . | Argument . | Offensive . | Argument . | Offensive . | Bad language . | Dismissive language . | Dismissive language . | Polarity . |

| Regression (type of dep. variable) . | Logistic (labels) . | OLS (frequencies) . | ||||||

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . | |

| month_id | −0.0001*** (0.00003) | 0.0003*** (0.00003) | 0.001*** (0.0001) | |||||

| I(month_id2) | 0.00000*** (0.00000) | −0.00000*** (0.00000) | −0.00000*** (0.00000) | |||||

| governmentLiberal | 0.057*** (0.005) | 0.037 (0.023) | 0.159*** (0.008) | 0.045* (0.017) | −0.013*** (0.003) | −0.021*** (0.004) | −0.007 (0.006) | −0.002 (0.001) |

| chamberSenate | −0.101*** (0.005) | −0.059* (0.022) | −0.046*** (0.008) | −0.037 (0.017) | −0.018*** (0.003) | −0.018*** (0.004) | −0.014 (0.006) | |

| party_familyLabor | 0.013* (0.005) | 0.020 (0.022) | 0.058*** (0.008) | 0.046* (0.017) | −0.0001 (0.003) | 0.024*** (0.004) | 0.045*** (0.006) | −0.004*** (0.001) |

| party_familyGreens | 0.329*** (0.010) | 0.266*** (0.047) | 0.493*** (0.015) | 0.261*** (0.034) | −0.003 (0.007) | 0.144*** (0.009) | 0.128*** (0.012) | −0.017*** (0.001) |

| party_familycentre | 0.296*** (0.012) | 0.197** (0.055) | 0.405*** (0.017) | 0.213*** (0.040) | 0.010 (0.006) | 0.023** (0.007) | 0.035** (0.011) | −0.008*** (0.001) |

| party_familyind. | 0.174*** (0.018) | 0.111 (0.080) | 0.248*** (0.027) | 0.138 (0.061) | 0.018* (0.007) | 0.107*** (0.009) | 0.139*** (0.017) | −0.004 (0.002) |

| party_familyright | 0.342*** (0.027) | 0.822*** (0.091) | 0.468*** (0.042) | 0.729*** (0.069) | 0.078*** (0.011) | 0.134*** (0.014) | 0.199*** (0.024) | −0.018*** (0.004) |

| topicAbortion | 0.952*** (0.017) | 1.345*** (0.054) | 1.439*** (0.023) | 1.197*** (0.041) | 0.005 (0.017) | −0.020*** (0.002) | ||

| topicCoal | 0.481*** (0.006) | 0.293*** (0.026) | 0.472*** (0.010) | 0.220*** (0.019) | 0.080*** (0.006) | −0.008*** (0.001) | ||

| topicDrugs | 1.240*** (0.015) | 0.974*** (0.056) | 1.909*** (0.022) | 1.008*** (0.042) | −0.030 (0.015) | −0.049*** (0.002) | ||

| topicNuclear | 0.953*** (0.008) | 0.102 (0.040) | 1.771*** (0.010) | 0.193*** (0.028) | −0.001 (0.008) | −0.022*** (0.001) | ||

| topicRenewables | 1.140*** (0.009) | −0.088 (0.053) | 1.737*** (0.014) | −0.117** (0.040) | 0.023 (0.011) | 0.003 (0.001) | ||

| decade_id1910 | 0.064 (0.036) | 0.605 (0.263) | 0.298*** (0.055) | 0.284 (0.199) | −0.0005 (0.005) | |||

| decade_id1920 | 0.063 (0.033) | 0.495 (0.254) | 0.288*** (0.050) | 0.333 (0.181) | −0.011 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1930 | 0.132*** (0.034) | 0.880** (0.244) | 0.288*** (0.049) | 0.635** (0.172) | 0.001 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1940 | 0.123*** (0.029) | 0.849** (0.227) | 0.402*** (0.042) | 0.563** (0.155) | −0.002 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1950 | −0.087** (0.029) | 0.671** (0.227) | −0.080 (0.042) | 0.379 (0.156) | 0.011** (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1960 | −0.308*** (0.029) | 0.838** (0.223) | −0.352*** (0.042) | 0.566** (0.150) | 0.005 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1970 | −0.407*** (0.028) | 1.097*** (0.217) | −0.616*** (0.040) | 0.859*** (0.144) | −0.010** (0.003) | |||

| decade_id1980 | −0.327*** (0.027) | 1.157*** (0.217) | −0.600*** (0.040) | 0.964*** (0.143) | −0.009* (0.003) | |||

| decade_id1990 | −0.316*** (0.027) | 1.228*** (0.215) | −0.651*** (0.039) | 1.026*** (0.142) | −0.001 (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2000 | −0.201*** (0.027) | 1.125*** (0.215) | −0.609*** (0.039) | 0.966*** (0.142) | 0.001 (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2010 | −0.053 (0.026) | 1.357*** (0.215) | −0.496*** (0.039) | 1.131*** (0.142) | 0.011** (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2020 | 0.076* (0.029) | 1.221*** (0.222) | −0.213*** (0.042) | 1.114*** (0.146) | 0.013** (0.004) | |||

| Constant | −2.076*** (0.027) | −6.509*** (0.217) | −1.794*** (0.040) | −6.223*** (0.143) | 0.119*** (0.006) | 0.086*** (0.008) | 0.008 (0.014) | 0.092*** (0.003) |

| Observations | 1,611,653 | 1,611,653 | 593,482 | 2,559,862 | 90,351 | 90,351 | 69,133 | 593,482 |

Note: *p < 0.01; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.001

| Data subset . | Bills and questions . | All sentences . | Topics . | All . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: . | Argument . | Offensive . | Argument . | Offensive . | Bad language . | Dismissive language . | Dismissive language . | Polarity . |

| Regression (type of dep. variable) . | Logistic (labels) . | OLS (frequencies) . | ||||||

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . | |

| month_id | −0.0001*** (0.00003) | 0.0003*** (0.00003) | 0.001*** (0.0001) | |||||

| I(month_id2) | 0.00000*** (0.00000) | −0.00000*** (0.00000) | −0.00000*** (0.00000) | |||||

| governmentLiberal | 0.057*** (0.005) | 0.037 (0.023) | 0.159*** (0.008) | 0.045* (0.017) | −0.013*** (0.003) | −0.021*** (0.004) | −0.007 (0.006) | −0.002 (0.001) |

| chamberSenate | −0.101*** (0.005) | −0.059* (0.022) | −0.046*** (0.008) | −0.037 (0.017) | −0.018*** (0.003) | −0.018*** (0.004) | −0.014 (0.006) | |

| party_familyLabor | 0.013* (0.005) | 0.020 (0.022) | 0.058*** (0.008) | 0.046* (0.017) | −0.0001 (0.003) | 0.024*** (0.004) | 0.045*** (0.006) | −0.004*** (0.001) |

| party_familyGreens | 0.329*** (0.010) | 0.266*** (0.047) | 0.493*** (0.015) | 0.261*** (0.034) | −0.003 (0.007) | 0.144*** (0.009) | 0.128*** (0.012) | −0.017*** (0.001) |

| party_familycentre | 0.296*** (0.012) | 0.197** (0.055) | 0.405*** (0.017) | 0.213*** (0.040) | 0.010 (0.006) | 0.023** (0.007) | 0.035** (0.011) | −0.008*** (0.001) |

| party_familyind. | 0.174*** (0.018) | 0.111 (0.080) | 0.248*** (0.027) | 0.138 (0.061) | 0.018* (0.007) | 0.107*** (0.009) | 0.139*** (0.017) | −0.004 (0.002) |

| party_familyright | 0.342*** (0.027) | 0.822*** (0.091) | 0.468*** (0.042) | 0.729*** (0.069) | 0.078*** (0.011) | 0.134*** (0.014) | 0.199*** (0.024) | −0.018*** (0.004) |

| topicAbortion | 0.952*** (0.017) | 1.345*** (0.054) | 1.439*** (0.023) | 1.197*** (0.041) | 0.005 (0.017) | −0.020*** (0.002) | ||

| topicCoal | 0.481*** (0.006) | 0.293*** (0.026) | 0.472*** (0.010) | 0.220*** (0.019) | 0.080*** (0.006) | −0.008*** (0.001) | ||

| topicDrugs | 1.240*** (0.015) | 0.974*** (0.056) | 1.909*** (0.022) | 1.008*** (0.042) | −0.030 (0.015) | −0.049*** (0.002) | ||

| topicNuclear | 0.953*** (0.008) | 0.102 (0.040) | 1.771*** (0.010) | 0.193*** (0.028) | −0.001 (0.008) | −0.022*** (0.001) | ||

| topicRenewables | 1.140*** (0.009) | −0.088 (0.053) | 1.737*** (0.014) | −0.117** (0.040) | 0.023 (0.011) | 0.003 (0.001) | ||

| decade_id1910 | 0.064 (0.036) | 0.605 (0.263) | 0.298*** (0.055) | 0.284 (0.199) | −0.0005 (0.005) | |||

| decade_id1920 | 0.063 (0.033) | 0.495 (0.254) | 0.288*** (0.050) | 0.333 (0.181) | −0.011 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1930 | 0.132*** (0.034) | 0.880** (0.244) | 0.288*** (0.049) | 0.635** (0.172) | 0.001 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1940 | 0.123*** (0.029) | 0.849** (0.227) | 0.402*** (0.042) | 0.563** (0.155) | −0.002 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1950 | −0.087** (0.029) | 0.671** (0.227) | −0.080 (0.042) | 0.379 (0.156) | 0.011** (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1960 | −0.308*** (0.029) | 0.838** (0.223) | −0.352*** (0.042) | 0.566** (0.150) | 0.005 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1970 | −0.407*** (0.028) | 1.097*** (0.217) | −0.616*** (0.040) | 0.859*** (0.144) | −0.010** (0.003) | |||

| decade_id1980 | −0.327*** (0.027) | 1.157*** (0.217) | −0.600*** (0.040) | 0.964*** (0.143) | −0.009* (0.003) | |||

| decade_id1990 | −0.316*** (0.027) | 1.228*** (0.215) | −0.651*** (0.039) | 1.026*** (0.142) | −0.001 (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2000 | −0.201*** (0.027) | 1.125*** (0.215) | −0.609*** (0.039) | 0.966*** (0.142) | 0.001 (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2010 | −0.053 (0.026) | 1.357*** (0.215) | −0.496*** (0.039) | 1.131*** (0.142) | 0.011** (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2020 | 0.076* (0.029) | 1.221*** (0.222) | −0.213*** (0.042) | 1.114*** (0.146) | 0.013** (0.004) | |||

| Constant | −2.076*** (0.027) | −6.509*** (0.217) | −1.794*** (0.040) | −6.223*** (0.143) | 0.119*** (0.006) | 0.086*** (0.008) | 0.008 (0.014) | 0.092*** (0.003) |

| Observations | 1,611,653 | 1,611,653 | 593,482 | 2,559,862 | 90,351 | 90,351 | 69,133 | 593,482 |

| Data subset . | Bills and questions . | All sentences . | Topics . | All . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: . | Argument . | Offensive . | Argument . | Offensive . | Bad language . | Dismissive language . | Dismissive language . | Polarity . |

| Regression (type of dep. variable) . | Logistic (labels) . | OLS (frequencies) . | ||||||

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . | |

| month_id | −0.0001*** (0.00003) | 0.0003*** (0.00003) | 0.001*** (0.0001) | |||||

| I(month_id2) | 0.00000*** (0.00000) | −0.00000*** (0.00000) | −0.00000*** (0.00000) | |||||

| governmentLiberal | 0.057*** (0.005) | 0.037 (0.023) | 0.159*** (0.008) | 0.045* (0.017) | −0.013*** (0.003) | −0.021*** (0.004) | −0.007 (0.006) | −0.002 (0.001) |

| chamberSenate | −0.101*** (0.005) | −0.059* (0.022) | −0.046*** (0.008) | −0.037 (0.017) | −0.018*** (0.003) | −0.018*** (0.004) | −0.014 (0.006) | |

| party_familyLabor | 0.013* (0.005) | 0.020 (0.022) | 0.058*** (0.008) | 0.046* (0.017) | −0.0001 (0.003) | 0.024*** (0.004) | 0.045*** (0.006) | −0.004*** (0.001) |

| party_familyGreens | 0.329*** (0.010) | 0.266*** (0.047) | 0.493*** (0.015) | 0.261*** (0.034) | −0.003 (0.007) | 0.144*** (0.009) | 0.128*** (0.012) | −0.017*** (0.001) |

| party_familycentre | 0.296*** (0.012) | 0.197** (0.055) | 0.405*** (0.017) | 0.213*** (0.040) | 0.010 (0.006) | 0.023** (0.007) | 0.035** (0.011) | −0.008*** (0.001) |

| party_familyind. | 0.174*** (0.018) | 0.111 (0.080) | 0.248*** (0.027) | 0.138 (0.061) | 0.018* (0.007) | 0.107*** (0.009) | 0.139*** (0.017) | −0.004 (0.002) |

| party_familyright | 0.342*** (0.027) | 0.822*** (0.091) | 0.468*** (0.042) | 0.729*** (0.069) | 0.078*** (0.011) | 0.134*** (0.014) | 0.199*** (0.024) | −0.018*** (0.004) |

| topicAbortion | 0.952*** (0.017) | 1.345*** (0.054) | 1.439*** (0.023) | 1.197*** (0.041) | 0.005 (0.017) | −0.020*** (0.002) | ||

| topicCoal | 0.481*** (0.006) | 0.293*** (0.026) | 0.472*** (0.010) | 0.220*** (0.019) | 0.080*** (0.006) | −0.008*** (0.001) | ||

| topicDrugs | 1.240*** (0.015) | 0.974*** (0.056) | 1.909*** (0.022) | 1.008*** (0.042) | −0.030 (0.015) | −0.049*** (0.002) | ||

| topicNuclear | 0.953*** (0.008) | 0.102 (0.040) | 1.771*** (0.010) | 0.193*** (0.028) | −0.001 (0.008) | −0.022*** (0.001) | ||

| topicRenewables | 1.140*** (0.009) | −0.088 (0.053) | 1.737*** (0.014) | −0.117** (0.040) | 0.023 (0.011) | 0.003 (0.001) | ||

| decade_id1910 | 0.064 (0.036) | 0.605 (0.263) | 0.298*** (0.055) | 0.284 (0.199) | −0.0005 (0.005) | |||

| decade_id1920 | 0.063 (0.033) | 0.495 (0.254) | 0.288*** (0.050) | 0.333 (0.181) | −0.011 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1930 | 0.132*** (0.034) | 0.880** (0.244) | 0.288*** (0.049) | 0.635** (0.172) | 0.001 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1940 | 0.123*** (0.029) | 0.849** (0.227) | 0.402*** (0.042) | 0.563** (0.155) | −0.002 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1950 | −0.087** (0.029) | 0.671** (0.227) | −0.080 (0.042) | 0.379 (0.156) | 0.011** (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1960 | −0.308*** (0.029) | 0.838** (0.223) | −0.352*** (0.042) | 0.566** (0.150) | 0.005 (0.004) | |||

| decade_id1970 | −0.407*** (0.028) | 1.097*** (0.217) | −0.616*** (0.040) | 0.859*** (0.144) | −0.010** (0.003) | |||

| decade_id1980 | −0.327*** (0.027) | 1.157*** (0.217) | −0.600*** (0.040) | 0.964*** (0.143) | −0.009* (0.003) | |||

| decade_id1990 | −0.316*** (0.027) | 1.228*** (0.215) | −0.651*** (0.039) | 1.026*** (0.142) | −0.001 (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2000 | −0.201*** (0.027) | 1.125*** (0.215) | −0.609*** (0.039) | 0.966*** (0.142) | 0.001 (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2010 | −0.053 (0.026) | 1.357*** (0.215) | −0.496*** (0.039) | 1.131*** (0.142) | 0.011** (0.003) | |||

| decade_id2020 | 0.076* (0.029) | 1.221*** (0.222) | −0.213*** (0.042) | 1.114*** (0.146) | 0.013** (0.004) | |||

| Constant | −2.076*** (0.027) | −6.509*** (0.217) | −1.794*** (0.040) | −6.223*** (0.143) | 0.119*** (0.006) | 0.086*** (0.008) | 0.008 (0.014) | 0.092*** (0.003) |

| Observations | 1,611,653 | 1,611,653 | 593,482 | 2,559,862 | 90,351 | 90,351 | 69,133 | 593,482 |

Note: *p < 0.01; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.001

Funding

This work is part of a larger collaborative project titled ‘Civic Virtue in Public Life: Understanding and Countering Incivility in Liberal Democracies’. The research was funded as part of the Self, Virtue and Public Life Project, a three-year research initiative based at the Institute for the Study of Human Flourishing at the University of Oklahoma, made possible with generous support from the Templeton Religion Trust.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments on earlier versions of the article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

Footnotes

In cases of more extreme incivility—such as sexism, harassment, and violence against women parliamentarians—the roots of this behaviour are found not only in entrenched gendered ideologies and gender imbalances in the political system, but also inadequate mechanisms for upholding codes of behaviour (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2016).

Aboriginal OR indigenous OR native title OR aborigine.

Abortion OR pro-life OR contraceptive OR contraception OR birth control.

Coal OR lignite OR coke.

Illegal drug OR illicit drug OR psychoactive OR amphetamine OR opioid OR morphine OR heroin OR cannabis OR cocaine OR ecstasy OR hallucinogen OR inhalant OR ketamine.

Nuclear OR uranium.

Renewable OR solar power OR wind power OR solar energy OR wind energy OR wind electricity.

The largest examples of centre parties are the early Protectionist Party (which split into two factions in 1909, one joining the Coalition, the other Labor), the Australian Democrats, the Democratic Labor Party, and, in recent years, the Centre Alliance (formerly known as the Nick Xenophon Team), Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party, and the Jacquie Lambie Network, plus a handful of smaller short-lived splinter groups. Right-wing parties are Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, the Palmer United Party, Katter’s Australia Party, Family First, and the Australian Conservative Party. Independents are those few MPs who are listed as independents in the Hansard records.

While, as we explained earlier, a distinction should be made between size and relevance of minor parties—as these may not always be as correlated as they are in the Australian context—and relevance should be assigned a more important role in the evaluation of parties’ offensiveness, one might argue that size should still play a role in our analysis. More specifically, if our assumptions regarding typical data patterns hold—i.e. minor/irrelevant/small parties present higher levels of offensiveness than major/relevant/large ones—and also assuming that the use of offensive language is often episodic and restricted to uncivil utterances by a single or very few MPs—we do not have the data to support this claim but we think it is quite plausible—then large parliamentary party groups are likely to have a much smaller share of MPs contributing to their party group’s offensiveness score than minor parties. The occasional instances of offensiveness of a few MPs in large parties are therefore likely to be ‘diluted’ within their mostly civil ranks, thus losing much of their impact. If this is the case, then offensiveness in minor Australian parties is likely to be exponentially higher than in major parties—because a higher percentage of their MPs use offensive language—thus further strengthening our interpretation of the data.

The same variation might be observed within each chamber over time though we do not have the data to support this conclusion.

The Standing Orders of the Australian Parliament, which include rules about time limits applying to parliamentary debates, are usually reviewed by incoming governments (Gill, 2022). However, while a reduction trend can be found in more recent times (Parliament of Australia, 2022, Chapter 10), we found no evidence that there was a reduction trend in the time limits in the late 1990s which could explain the corresponding reduction trend in the level of argumentation in that period that our data reveal.

Furthermore, as in the case of offensiveness, party size may also play a role when it comes to deliberative quality. More specifically, assuming that large party groups enlist more speakers for a debate than small party groups, this may have two consequences. On the one hand, larger party group size may increase the overall level of argumentation and reasoning. Assuming that each MP has normally the same time available to speak, and if many MPs from the same party speak, the overall level argumentation and reasoning may end up be higher than in minor parties that can only enlist one or a few MPs to speak. That is, even if, for example, only 50% of large party MPs’ speeches contain reason-giving relevant to the specific point being debated—whereas the percentage is, say, 90% in the case of minor party MPs—if there are 50 major party MPs speaking vs. 2 from a minor party, the overall level of reason-giving and argumentation will be higher in the former than the latter. On the other hand, party size is likely to reduce the average level of argumentation in the contributions of large party group members. This is because as a parliamentary debate on a specific topic proceeds, and speakers come up with new arguments, at some point some arguments will become repetitive and will no longer be mentioned, and eventually the set of arguments will be exhausted. Hence, the level of argumentativeness of late speakers from the same party group is likely to be lower compared to early speakers, thus decreasing the average level of argumentation. Conversely, all or most MPs from minor parties will be able to (in fact will have to) cover a wider range of arguments in their speeches, maximising the time available to them and the average level of argumentation in their party.