-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jac M Larner, Richard Wyn Jones, Ed Gareth Poole, Paula Surridge, Daniel Wincott, Incumbency and Identity: The 2021 Senedd Election, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 76, Issue 4, October 2023, Pages 857–878, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsac012

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Taking place amid a global pandemic, the 2021 Senedd Election saw Welsh Labour returned as the largest party at the sixth consecutive occasion since the institution’s founding in 1999. Results for opposition parties were mixed: the Conservatives achieved their highest ever vote share but their seat tally fell short of pre-election expectations, and Plaid Cymru again made little progress. Using data from the 2021 Welsh Election Study, we explore the election campaign and results, and offer a first analysis of vote choice. We find that Labour not only benefitted from incumbency advantages drawn from voters’ approval of the Welsh Government’s handling of the pandemic, but through its use of symbols, branding and messaging, the party continues to remain attuned to a national identity position that broadly aligns with that of the electorate as a whole.

1. Introduction

The sixth election to the Senedd—until 2020 the National Assembly for Wales—took place in the context of the global coronavirus pandemic. Such a generation-defining event had consequences not only for the campaign and the election itself, but also for voters’ engagement with—and perceptions of—the devolved institutions themselves. Social distancing and stay-at-home requirements naturally affected the conduct of the election, from restrictions on door-to-door canvassing and leafletting to increased postal voting and the replacement of the traditional overnight count with a daytime, socially distanced counting process. But an even more important consequence of the pandemic was to register at a deeper level. By the time of the election on 6 May 2021, extensive public awareness and media coverage of the devolved government’s response to Covid-19 brought Welsh governmental institutions and their leading political figures to a level of public prominence than would have been unimaginable at the establishment of devolution in 1999.

Despite the extraordinary circumstances under which the election was contested, however, the result itself was familiar. For the sixth consecutive election—a clean sweep since the advent of devolution in 1999—Welsh Labour emerged as convincing and comfortable winners, and their haul of 30 of the Senedd’s 60 seats matched their best-ever performance. Although the Welsh Conservatives recorded the largest net increase in vote share of any party at the election and secured their largest number of seats ever, this result represented only a marginal improvement on their previous high-water mark in 2011 and fell short of the party’s own expectations at the start of the campaign. Plaid Cymru’s election was yet another characterised by a lack of progress: the party lost support in key constituencies and recorded a single net gain thanks to the compensatory regional party lists. Meanwhile the splintered remnants of the populist right and anti-devolution parties, which had enjoyed considerable success in the previous election in 2016, were roundly rejected by the electorate.

Examining the 2021 Senedd election result in detail, this article draws data primarily from the 2021 Welsh Election Study (WES) (Wyn Jones et al., 2021). The 2021 WES is an Economic and Social Research Council-funded survey of approximately 4,000 eligible voters in Wales carried out online by YouGov. The survey consists of four waves (one pre-election, two post-election, plus an additional rolling campaign wave) and employs a panel design to re-interview as many of the same respondents as possible. To track changes in attitudes, preferences and behaviours of the same respondents over time, the 2021 study also includes a large number of respondents who took part in the 2019 WES (Wyn Jones and Larner, 2020) and 2016 WES (Scully et al., 2016)—comprising, respectively, 32 and 40% of the 2021 survey. The survey’s large sample size coupled with its panel element provides an unrivalled source to study political behaviour and attitudes in Wales.

Consistent with analyses of concurrent elections held elsewhere in the UK during the pandemic, we show that the Welsh Labour benefitted from an incumbency advantage from voters’ perceptions that the Welsh Government had handled the pandemic relatively well, especially when compared with the UK Government. However, because this election was the sixth successive devolved victory for the party, Labour’s 2021 victory cannot be attributed solely to pandemic incumbency advantages. Rather, we use WES data to illustrate how a much more enduring feature of Welsh society—Welsh national identity—markedly limits the gains that Labour’s opponents can expect to achieve at devolved elections. The Conservatives in Wales cannot currently win the support of voters who consider themselves primarily or exclusively Welsh, while Plaid Cymru equally struggle to find votes from those who consider themselves either fully or partially British. What remains, then, is a Welsh Labour party that emphasises its Welsh credentials and distinctiveness from the UK party, while remaining, at least for now, committed to the union. Maintaining this ‘Goldilocks’ positioning on national identity and Wales’ median constitutional preferences across six devolved elections means that Welsh Labour party is now by some margin the most successful electoral force in the UK.

2. The Senedd election in context: Covid-19 and constitutional upheaval

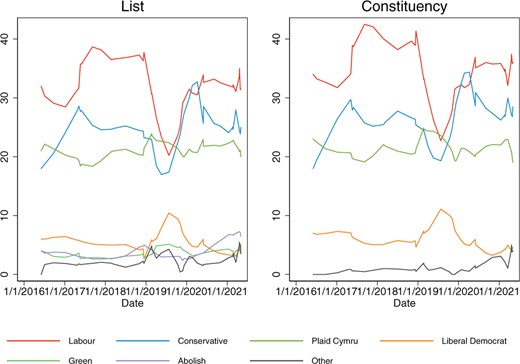

After six devolved elections in Wales, seasoned observers will detect a now rather familiar narrative arc to each campaign. First a ‘shock opinion poll’ is published, prompting a burst of media speculation suggesting that, finally, Labour hegemony in Wales is about to face serious challenge (see Figure 1). These preliminaries are followed by a campaign that sees Welsh Labour apparently shoring up their position; an impression that is subsequently confirmed when the results are declared and the party emerges, once again, as the country’s largest Senedd group by some distance. Part of the explanation for such a narrative is a craving for novelty. With Labour having won every UK general election and devolved election in Wales since 1922, from a political commentary perspective the over-turning of Labour hegemony would be an extraordinarily noteworthy event. Explaining a century of one-party dominance is an altogether subtler proposition than chronicling the day-to-day dynamics of an election campaign.

Senedd vote intention from Welsh opinion polling, 2016–2021 (N = 41). Data are available at www.welshelectionstudy.cymru.

The prevailing narrative of the 2021 devolved election indeed conformed to type. An early opinion poll was indeed hyped as an early indication of sweeping change—in this case, that First Minister Mark Drakeford might lose his seat in Cardiff West (e.g. see Bush, 2021). But as the campaign progressed, Welsh Labour appeared progressively more at ease about their likely electoral prospects while opposition parties became increasingly uncertain about their own. Not only were Labour able to snatch one additional seat to take their total to 30, but the party was able to push back opponents in key defensive target seats while creating new offensive targets seats for itself in future elections.1 Drakeford’s own majority jumped by 13 percentage points and his party increased its vote share in 34 of 40 constituencies.

Despite the campaign ultimately resorting to type, however, the timing of the election during one of the most politically volatile periods in decades gave reasons to suspect that the 2021 election might prove challenging for Wales’ dominant party. The 2016 European Union (EU) referendum was associated with the restructuring of the British electorate into two camps that did not align with traditional partisan divisions, and acute tensions on either side of this division resulted in the political upheaval of two Westminster elections (2017 and 2019) and three different UK Prime Ministers. The Labour party had lost significant ground to the Conservatives at the 2019 UK general election in the northeast of Wales in particular—an area which media and academic commentary alike has routinely included in subsequent accounts of Labour’s lost ‘red wall’ (Awan-Scully, 2020). This served to underpin considerable Conservative optimism about—and investment in—their prospects for the devolved election (Electoral Commission, 2022).

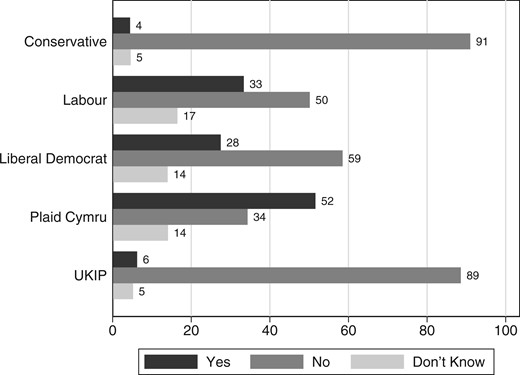

On Labour’s other flank, there was also considerable uncertainty about the potential electoral impact of another notable recent development in Welsh politics, namely the emergence of a substantial and energetic grassroots independence campaign, YesCymru. Both WES 2021 data and numerous public opinion polls suggest that between a quarter and one-third of the Welsh electorate would vote in favour of independence if a referendum were to be held, including one third of 2016 Labour voters (see Figure 2).2 These pre-election fundamentals therefore gave some credence to notions that changed political environments might provide fruitful ground from which both the Conservatives and Plaid Cymru might challenge Labour hegemony.

Welsh independence referendum vote intention by 2016 constituency vote. N = 2,624. Data are weighted.

With the benefit of hindsight, it may now appear obvious that incumbency during a pandemic would have been an electoral asset. But there many occasions during the 14 months to May 2021 in which this eventuality was far from certain. After all, this was a crisis that had thrust into the public eye a Welsh Labour leader who was previously little-known outside of political circles (see Surridge and Larner, 2021), into a leadership role in which he would inevitably be compared with two of the most experienced political communicators in UK politics, Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon. Moreover, the Welsh Government’s decision to adopt a generally more cautious approach in messaging and substance than that of the UK Government had been subjected to frequent criticism by Welsh Conservatives in the Senedd, senior Conservative politicians at Westminster, and the Conservative-supporting London-based news media.3

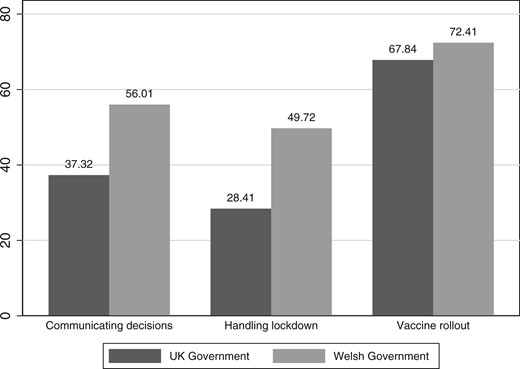

By the time of the 2021 Senedd election, however, the handling of the pandemic by the Welsh Government4 and by Mark Drakeford personally had become a potent electoral asset for Welsh Labour. As illustrated by Figure 3, on a range of Covid-19 related issues, far more voters thought that the Welsh Government had done a better job than the UK Government. Reflecting these unique circumstances, Welsh Labour’s campaign focused on Wales’s pandemic response and on Mark Drakeford’s personal leadership strengths. But such competence-related messaging was once again situated within the party’s longstanding ideological and national appeals to Welsh symbols, branding and values that it has adopted so comfortably since the earliest years of devolution (Wyn Jones et al., 2002). In this regard, and at the inflexion point of Covid management and appeals to national values, Welsh Labour could draw attention to their claims to have adopted a more cautious and deliberative approach to managing the pandemic than the Conservatives in London. Given that such performance-related appeals aligned with the overarching territorial politics cleavage, this strategy was (once again) election winning.

Percentage of respondents agreeing that UK/Welsh Government had done a good job of handling covid-19 policy areas. N = 4,072. Data are weighted.

In terms of policies not associated with the pandemic, although Welsh Labour’s election manifesto was titled Moving Wales Forward, ‘steady as she goes’ more accurately captures the spirit of a document in which both new ideas and new spending commitments were at a premium. All this stood in stark contrast with the approach adopted by the Welsh Conservatives and Plaid Cymru, whose respective manifestos were replete with both as they sought to shift the focus of the campaign to a post-crisis future (for an overview see Ifan, 2021).

It is, however, reflective of the state of both Welsh and UK politics in the third decade of devolution that both the immediate policy response to the pandemic and perceptions of longer-term prospects for post-Covid recovery were intrinsically linked to the question of Wales’ constitutional future. The Welsh Conservatives’ withering criticism of what it has viewed as unwarranted deviations from the crisis response of the UK government (acting in this context as England’s government) is premised on a logic that calls into question the party’s continuing commitment to devolution itself. This suspicion is only strengthened by the Welsh party’s wholehearted support for the UK government’s efforts to bypass the devolved level as it develops its plans for a post-Brexit replacement for EU structural funding and allied efforts aimed at ‘levelling up’. From Welsh Labour’s perspective, the Conservatives’ apparent willingness to undermine devolution amid the most significant combined health, social and economic crisis of our age, merely underlines the First Minister’s claim that the UK in its current form is ‘broken’ (ITV, 2021).

In a political landscape in which the UK Conservatives and Welsh Labour remained implacably opposed on national territorial lines as well as matters of policy, it is perhaps not surprising that Plaid Cymru found it difficult to gain traction. With Drakeford particularly popular among Plaid Cymru voters—precisely because of the distinctive approach adopted by his government during the pandemic—and with even those voters who favour independence viewing defeating Conservative threats to devolution as a higher immediate priority, Plaid Cymru’s national campaign struggled to make an impression. Less understandable, however, was the party’s unfocused efforts in ostensible target seats and its campaign messaging that made only sporadic efforts to target the list vote, even in those electoral regions where voting Labour could credibly be presented as a ‘wasted vote’.5

3. The election result

The Senedd is a 60 member body elected via a variant of Mixed Member Proportional known in the UK as the Additional Member System. Forty constituency members are elected by plurality rule in single-member districts, and 20 members are elected from compensatory closed party-list proportional representation from 5 electoral regions that each return 4 members. Since only a third of Senedd members are elected by List-PR, and because one party has historically predominated in constituency contests, the final composition of the Siambr is perhaps best characterised as semi-proportional. Dissatisfaction over the small size of the Senedd membership and the workings of the electoral system are the subject of an ongoing reform debate between the Welsh political parties (see Section 5, below).

The distribution of seats showing changes since 2016 are illustrated in Table 1. Only three constituency seats changed hands at the 2021 election, which, while modest, was actually an increase from the single constituency switch in 2016. The Conservatives gained one seat from Labour (Vale of Clwyd) and one from the Welsh Liberal Democrats (Brecon and Radnorshire), while Labour gained one seat from Plaid Cymru (Rhondda). There was, however, substantial change in the partisan composition of the lists caused by the complete collapse of the populist right. Because the 2016 election had been held only a few weeks prior to the referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union, United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) were successful in gaining seven list seats at that election. This delegation quickly fractured into multiple rival groups such that by the time of the 2021 election, only one of the original seven remained a UKIP member. The rest were either sitting as independents or scattered across several different parties, the most potentially significant of which appeared to be the Abolish the Welsh Assembly party. But Euroscepticism’s turn to ‘devo-scepticism’ was to no avail. None of the populist right’s candidates were to come close to winning a seat in the sixth Senedd. Their places were taken by three additional Conservatives, two new Plaid Cymru representatives, one additional Labour member and the Senedd’s sole Liberal Democrat.

| Party . | Constituency vote share . | List vote share . | Seats . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | 39.9 (+5.2) | 36.2 (+4.7) | 30 (+1) |

| Conservative | 26.1 (+5.0) | 25.1 (+6.3) | 16 (+5) |

| Plaid Cymru | 20.3 (−0.2) | 20.7 (−0.1) | 13 (+1) |

| Liberal Democrats | 4.9 (−2.8) | 4.3 (−2.2) | 1 (−) |

| UKIP | 0.8 (−11.7) | 1.6 (−11.4) | 0 (−7) |

| Party . | Constituency vote share . | List vote share . | Seats . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | 39.9 (+5.2) | 36.2 (+4.7) | 30 (+1) |

| Conservative | 26.1 (+5.0) | 25.1 (+6.3) | 16 (+5) |

| Plaid Cymru | 20.3 (−0.2) | 20.7 (−0.1) | 13 (+1) |

| Liberal Democrats | 4.9 (−2.8) | 4.3 (−2.2) | 1 (−) |

| UKIP | 0.8 (−11.7) | 1.6 (−11.4) | 0 (−7) |

Change since 2016 in parentheses.

| Party . | Constituency vote share . | List vote share . | Seats . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | 39.9 (+5.2) | 36.2 (+4.7) | 30 (+1) |

| Conservative | 26.1 (+5.0) | 25.1 (+6.3) | 16 (+5) |

| Plaid Cymru | 20.3 (−0.2) | 20.7 (−0.1) | 13 (+1) |

| Liberal Democrats | 4.9 (−2.8) | 4.3 (−2.2) | 1 (−) |

| UKIP | 0.8 (−11.7) | 1.6 (−11.4) | 0 (−7) |

| Party . | Constituency vote share . | List vote share . | Seats . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | 39.9 (+5.2) | 36.2 (+4.7) | 30 (+1) |

| Conservative | 26.1 (+5.0) | 25.1 (+6.3) | 16 (+5) |

| Plaid Cymru | 20.3 (−0.2) | 20.7 (−0.1) | 13 (+1) |

| Liberal Democrats | 4.9 (−2.8) | 4.3 (−2.2) | 1 (−) |

| UKIP | 0.8 (−11.7) | 1.6 (−11.4) | 0 (−7) |

Change since 2016 in parentheses.

Progress on the compensatory regional lists for both Plaid Cymru and the Liberal Democrats served to distract from disappointing vote share performances for both parties. In contrast to both Welsh Labour and the Welsh Conservatives who both saw significant increases in vote share (in 34/40 and 35/40 constituencies, respectively), Plaid Cymru’s total vote share remained effectively static (increases in 22/40 constituencies), while the Liberal Democrat vote decreased in every single constituency. Given that these losses were relative to the already abysmally-poor set of results recorded by the party in the 2016 Senedd election, there must now be fundamental questions about its future direction or even viability, especially as it will now no longer qualify as a ‘major party’ for the purposes of media coverage at future election campaigns.

The 2021 election was also the first to be held in Wales at which eligible voters included 16- and 17-year-olds. Further research will be required to see what if any difference this extended franchise made to the overall result. But given the impact of the pandemic on the country’s education system, schools are unlikely to have been able to deliver the major civic education campaign that was originally intended to accompany this reform (see Huebner et al., 2021; Tonge et al., 2021). Overall, at 46.6% of the eligible electorate, turnout at the election was (albeit narrowly) the highest reached at any devolved election in Wales to date. A further positive development was the decision to replace the traditional overnight count with a socially distanced daytime-only counting process, resulting in unprecedently large audiences tuning into BBC and ITV Cymru Wales election coverage on Friday and Saturday (Ofcom, 2021, p. 28). With an estimated audience size of approximately half the electorate, here at least is evidence of genuine interest in Welsh devolved democracy and that straightforward, low-cost reforms can indeed strengthen public engagement with Wales’ politics and elections.

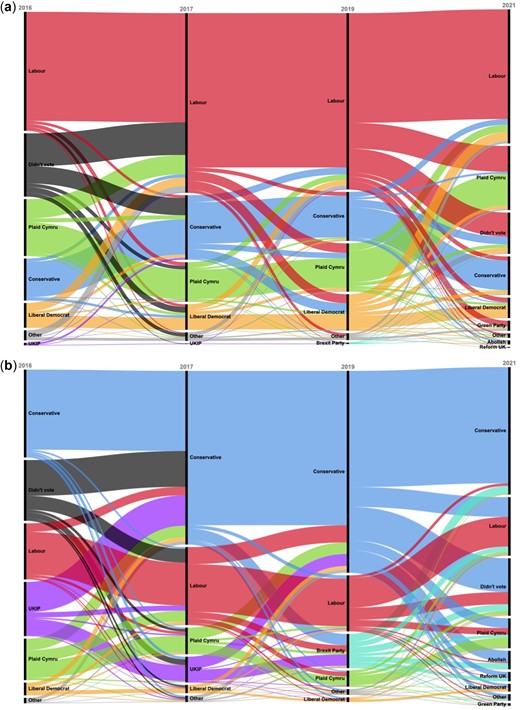

4. Returning to the fold: Vote choice by ‘Remainers’ and ‘Leavers’ in the 2021 election

One major area of focus in the 2021 WES is the interactions between vote choice and voters’ preferences on withdrawal from the EU, which was perhaps the centrally important cleavage in the politically turbulent five years between the 2016 and 2021 elections (and which drove substantial levels of volatility in the electorate, Fieldhouse et al., 2019). Accordingly, we can investigate how individual respondents in the WES survey changed their vote over the four elections held during this period: the Senedd elections in 2016 and 2021 and the UK general elections of 2017 and 2019. Figure 4 plots vote choice of individual respondents as an alluvial and is split between Remain supporting (Figure 4a) and Leave supporting (Figure 4b) voters.

Alluvial plots of respondents’ vote choice between 2016 and 2021. (a) Remain voting respondents (N = 1,509), (b) Leave voting respondents (N = 1,618).

Focusing first on Remain voters in Wales, note the considerable transfer of voters between Plaid Cymru at Senedd elections and Labour at Westminster elections. This pattern of vote switching between elections for different levels of government is well-documented and has been systematic since the establishment of devolution. There is ample evidence suggesting that a substantial proportion of the electorate think of themselves as a supporter of the Labour Party at Westminster elections and Plaid Cymru at devolved elections (see Trystan et al., 2003; Wyn Jones and Scully, 2006; Wyn Jones and Larner, 2020).

Figure 4b also demonstrates high levels of inter-election volatility, but in the case of Leave-supporting voters this switching is a more recent phenomenon relating to the 2016 European referendum. Among Leave voters note the substantial and unprecedented defection of 2016 Labour voters to the Conservatives at the 2017 and 2019 Westminster elections. Such a finding mirrors the plethora of political and academic commentary focusing on Labour-to-Conservative defections elsewhere in Britain, particularly in regions characterised as ‘Red Wall’ seats. But note also the subsequent return of a substantial proportion of Leave voters to Welsh Labour in 2021. Indeed, this shifting of Conservative Westminster voters to Labour Senedd voters in 2021 far exceeds that observed in any election since the establishment of Welsh devolution: whereas in 2016 just 3% of Conservative Westminster voters voted for Welsh Labour; in 2021 that percentage surged to 15%.6 While more Conservative Westminster voters in Wales turned out at the 2021 election than at any previous devolved contest, this surge in Conservative-to-Labour switching can be reasonably interpreted as of Leave-voting Labour voters ‘coming home’, having previously lent their vote to the Conservatives when leaving the EU was the most salient issue of the day.

A finding that Welsh Labour ‘leavers’ returned to the party in 2021 has potentially important implications for electoral research across the rest of the UK. Much academic work has shown how the EU referendum provided a ‘shock’ to the British party system and led to considerable polarisation (Fieldhouse et al., 2019; Hobolt et al., 2021; Sorace and Hobolt, 2021). But the Welsh patterns suggest that when the electoral salience of Brexit is relatively low, voters are prepared to again vote for parties they supported prior to the 2016 referendum.

One final point of interest in Figure 4 is the relatively high level of abstention of 2019 Conservative voters at the 2021 Senedd election. Differential turnout of Conservative voters between Westminster and Senedd elections is a perennial problem for the Welsh Conservatives. While turnout is lower at Senedd elections across the board, voter abstention at devolved elections disproportionately afflicts the Conservatives because a greater proportion of their supporters and voters opt not to vote than those of any other major political party.

5. Post-election Government Formation

Since the establishment of the devolved institutions in 1999, and even if the margin of victory and the composition of the governing bloc has varied, every Welsh Government has been led by Labour. The fifth Senedd (2016–2021) saw a Labour administration drawn from 29 elected members buttressed by the sole Liberal Democrat member who was to serve as a cabinet member throughout, plus a former Plaid Cymru member (a former party leader) who was appointed to a deputy ministerial post.

Which party would lead the government in the Sixth Senedd was, therefore, less of an active question than the constellation of coalitions and other governing arrangement alternatives that might emerge after the election. Pre-election speculation focused either on a potential Labour/Plaid Cymru arrangement, which would have been a successor to the coalition between the two parties that governed Wales between 2007 and 2011; a deal between Labour and any Liberal Democrat members elected, and therefore a re-run of the kind of arrangement seen between both parties between 2000 and 2003 and then between 2016 and 2021; or a Labour minority administration. Meanwhile, both Plaid Cymru and the Welsh Conservatives ruled out any form of post-election agreement between themselves. While such an arrangement had been possible in the past (most prominently in 2007, when an alternative Plaid Cymru-led coalition with the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats appeared for a short time to be the likeliest post-election outcome), the ideological gulf between the avowedly ‘muscular’ unionist Welsh Conservatives and the increasingly independence focused Plaid Cymru is now no longer bridgeable.

Even in the senior ranks of Welsh Labour itself, few if any seemed to have reckoned with the possibility of Labour being able to form a stable government after the election without external assistance. Yet, with Labour outperforming expectations and returning 30 members, and with Elin Jones, a Plaid Cymru MS, being re-elected as Llywydd (Presiding Officer), such an improbable outcome indeed materialised: Welsh Labour were in a position to govern alone. However, perhaps indicating Mark Drakeford’s ambition to leave a distinctive policy legacy after standing down at some point during the Sixth Senedd term, the Labour-led Welsh Government agreed a formal, three-year governing agreement with Plaid Cymru. The ‘Cooperation Agreement’ commits both parties to work together on a host of policy areas including universal free school meals, council tax reform, action on second homes and Senedd reform (Welsh Government, 2021). Unlike the 2007–2011 ‘One Wales’ coalition agreement between the parties, Plaid Cymru members do not hold any ministerial posts; the party instead appoints Special Advisors to ensure the agreement is fulfilled.

This unusual form of governing agreement has potential advantages for both parties. For Welsh Labour, the agreement allows them to push on with fundamental reform of the institutions of government by expanding the number of MSs and reforming the electoral system, knowing that they can rely on Plaid Cymru support to reach the supermajority required to enact such changes. For Plaid Cymru, the agreement allows them to avoid the pitfalls associated with junior membership of a formal coalition while still implementing many of the party’s manifesto commitments and arguably strengthening the party’s nation-building project.

6. Interpreting vote choice at the 2021 Senedd Election

To explore the 2021 Senedd election in greater depth, we next analyse the Welsh Election Study data using statistical modelling. We first run multinomial logistic regressions of respondents’ constituency vote (Table 2) and list vote (Table 3) as the dependent variable. We add a number of socio-demographic controls (age, gender, education household income and language proficiency), and also include national identity and competence measures that draw from a broad-based academic literature that emphasises the relationship between vote choice and both national and cultural identities (Balsom et al., 1983; Curtice, 1999; Wyn Jones and Lewis, 1999; Wyn Jones, 2001; Wyn Jones et al., 2002; though cf. Scully and Wyn Jones, 2012; Scully 2013). At the aggregate level at least, the 2021 data continue to suggest that national and cultural identities remain central to electoral politics in Wales. Labour tends to do best in those constituencies in which the highest proportion of the electorate were born in Wales and worst where the proportion born in England is highest; the reverse is true of the Conservatives (Larner and Surridge, 2021). Likewise, Plaid Cymru tends to perform well in constituencies containing the large numbers of Welsh speakers and poorly where Welsh is spoken by a smaller proportion of the electorate (Larner and Surridge, 2021).

Multinomial logit predicting constituency vote choice (base outcome = Labour), N = 2,966

| Variable . | Labour . | Conservative . | Plaid Cymru . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.122** | 0.325*** | −0.0869* | −0.116** |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

| Female | −0.0419* | −0.0109 | 0.000839 | 0.0520*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Graduate | 0.0907*** | −0.0563** | −0.0213 | −0.0131 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Household income | Reference = Less than £15k | |||

| £15k–£29K | 0.00938 | 0.0331 | −0.0176 | −0.0248 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £30k–£49k | −0.000382 | 0.0577* | −0.00635 | −0.051 |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £50k–£99k | −0.0335 | 0.161*** | −0.0422 | −0.0854** |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £100K+ | −0.0861 | 0.109 | 0.00818 | −0.0312 |

| (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.08) | (0.07) | |

| Speaks Welsh | −0.0871* | −0.0531 | 0.119*** | 0.0216 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Born in England | −0.0314 | −0.0521 | 0.0701*** | 0.0135 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| Relative territorial identity | −0.0182 | −0.306*** | 0.452*** | −0.127*** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Working class (subjective) | 0.0670*** | −0.0328 | −0.0174 | −0.0168 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Remainer | 0.195*** | −0.264*** | 0.0273 | 0.0419** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Welsh Gov handled lockdown well | 0.223*** | −0.157*** | 0.0225 | −0.0887*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Variable . | Labour . | Conservative . | Plaid Cymru . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.122** | 0.325*** | −0.0869* | −0.116** |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

| Female | −0.0419* | −0.0109 | 0.000839 | 0.0520*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Graduate | 0.0907*** | −0.0563** | −0.0213 | −0.0131 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Household income | Reference = Less than £15k | |||

| £15k–£29K | 0.00938 | 0.0331 | −0.0176 | −0.0248 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £30k–£49k | −0.000382 | 0.0577* | −0.00635 | −0.051 |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £50k–£99k | −0.0335 | 0.161*** | −0.0422 | −0.0854** |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £100K+ | −0.0861 | 0.109 | 0.00818 | −0.0312 |

| (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.08) | (0.07) | |

| Speaks Welsh | −0.0871* | −0.0531 | 0.119*** | 0.0216 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Born in England | −0.0314 | −0.0521 | 0.0701*** | 0.0135 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| Relative territorial identity | −0.0182 | −0.306*** | 0.452*** | −0.127*** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Working class (subjective) | 0.0670*** | −0.0328 | −0.0174 | −0.0168 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Remainer | 0.195*** | −0.264*** | 0.0273 | 0.0419** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Welsh Gov handled lockdown well | 0.223*** | −0.157*** | 0.0225 | −0.0887*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

Results presented as marginal effects for ease of interpretation. Effect size should be interpreted as probability of voting for a party for a given person holding all other X at their mean. Standard errors in parentheses.

Levels of significance:

p = 99%;

p = 95%;

p = 90%.

Multinomial logit predicting constituency vote choice (base outcome = Labour), N = 2,966

| Variable . | Labour . | Conservative . | Plaid Cymru . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.122** | 0.325*** | −0.0869* | −0.116** |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

| Female | −0.0419* | −0.0109 | 0.000839 | 0.0520*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Graduate | 0.0907*** | −0.0563** | −0.0213 | −0.0131 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Household income | Reference = Less than £15k | |||

| £15k–£29K | 0.00938 | 0.0331 | −0.0176 | −0.0248 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £30k–£49k | −0.000382 | 0.0577* | −0.00635 | −0.051 |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £50k–£99k | −0.0335 | 0.161*** | −0.0422 | −0.0854** |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £100K+ | −0.0861 | 0.109 | 0.00818 | −0.0312 |

| (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.08) | (0.07) | |

| Speaks Welsh | −0.0871* | −0.0531 | 0.119*** | 0.0216 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Born in England | −0.0314 | −0.0521 | 0.0701*** | 0.0135 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| Relative territorial identity | −0.0182 | −0.306*** | 0.452*** | −0.127*** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Working class (subjective) | 0.0670*** | −0.0328 | −0.0174 | −0.0168 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Remainer | 0.195*** | −0.264*** | 0.0273 | 0.0419** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Welsh Gov handled lockdown well | 0.223*** | −0.157*** | 0.0225 | −0.0887*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Variable . | Labour . | Conservative . | Plaid Cymru . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.122** | 0.325*** | −0.0869* | −0.116** |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

| Female | −0.0419* | −0.0109 | 0.000839 | 0.0520*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Graduate | 0.0907*** | −0.0563** | −0.0213 | −0.0131 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Household income | Reference = Less than £15k | |||

| £15k–£29K | 0.00938 | 0.0331 | −0.0176 | −0.0248 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £30k–£49k | −0.000382 | 0.0577* | −0.00635 | −0.051 |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £50k–£99k | −0.0335 | 0.161*** | −0.0422 | −0.0854** |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| £100K+ | −0.0861 | 0.109 | 0.00818 | −0.0312 |

| (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.08) | (0.07) | |

| Speaks Welsh | −0.0871* | −0.0531 | 0.119*** | 0.0216 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Born in England | −0.0314 | −0.0521 | 0.0701*** | 0.0135 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| Relative territorial identity | −0.0182 | −0.306*** | 0.452*** | −0.127*** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Working class (subjective) | 0.0670*** | −0.0328 | −0.0174 | −0.0168 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Remainer | 0.195*** | −0.264*** | 0.0273 | 0.0419** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Welsh Gov handled lockdown well | 0.223*** | −0.157*** | 0.0225 | −0.0887*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

Results presented as marginal effects for ease of interpretation. Effect size should be interpreted as probability of voting for a party for a given person holding all other X at their mean. Standard errors in parentheses.

Levels of significance:

p = 99%;

p = 95%;

p = 90%.

Multinomial logit predicting party list vote choice (base outcome = Labour), N = 2,966.

| Variable . | Labour . | Conservative . | Plaid Cymru . | Green . | Liberal Democrat . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.0754 | 0.282*** | −0.0677 | −0.0782*** | −0.0235 | −0.0372 |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.05) | |

| Female | −0.0966*** | −0.0101 | 0.0287 | 0.000757 | 0.0158 | 0.0614*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Graduate | 0.0194 | −0.0743*** | 0.0273 | 0.0188 | 0.00719 | 0.00167 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Household Income | Reference = Less than £15k | |||||

| £15k–£29K | 0.00469 | 0.0361 | 0.00342 | −0.00666 | −0.0201 | −0.0175 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £30k–£49k | 0.0106 | 0.0595** | 0.0223 | −0.0186 | −0.0299* | −0.0439 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £50k–£99k | −0.0563 | 0.156*** | −0.0185 | −0.00152 | −0.0197 | −0.0597* |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £100K+ | −0.192*** | 0.181* | 0.132 | −0.0156 | −0.0454* | −0.0599 |

| (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Speaks Welsh | −0.0429 | 0.000846 | 0.105*** | −0.0362 | −0.048 | 0.0215 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.04) | |

| Born in England | −0.032 | −0.0241 | 0.0453* | 0.0368** | 0.0213 | −0.0473** |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Relative territorial identity | −0.0719 | −0.293*** | 0.497*** | −0.00544 | −0.0407* | −0.0853** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.04) | |

| Working class (subjective) | 0.0917*** | −0.0254 | −0.0254 | −0.00226 | −0.0368*** | −0.00183 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Remainer | 0.151*** | −0.205*** | 0.0498*** | 0.0427*** | 0.0535*** | −0.0922*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Welsh Gov handled lockdown well | 0.179*** | −0.143*** | 0.026 | 0.0106 | 0.00541 | −0.0782*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Variable . | Labour . | Conservative . | Plaid Cymru . | Green . | Liberal Democrat . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.0754 | 0.282*** | −0.0677 | −0.0782*** | −0.0235 | −0.0372 |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.05) | |

| Female | −0.0966*** | −0.0101 | 0.0287 | 0.000757 | 0.0158 | 0.0614*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Graduate | 0.0194 | −0.0743*** | 0.0273 | 0.0188 | 0.00719 | 0.00167 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Household Income | Reference = Less than £15k | |||||

| £15k–£29K | 0.00469 | 0.0361 | 0.00342 | −0.00666 | −0.0201 | −0.0175 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £30k–£49k | 0.0106 | 0.0595** | 0.0223 | −0.0186 | −0.0299* | −0.0439 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £50k–£99k | −0.0563 | 0.156*** | −0.0185 | −0.00152 | −0.0197 | −0.0597* |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £100K+ | −0.192*** | 0.181* | 0.132 | −0.0156 | −0.0454* | −0.0599 |

| (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Speaks Welsh | −0.0429 | 0.000846 | 0.105*** | −0.0362 | −0.048 | 0.0215 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.04) | |

| Born in England | −0.032 | −0.0241 | 0.0453* | 0.0368** | 0.0213 | −0.0473** |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Relative territorial identity | −0.0719 | −0.293*** | 0.497*** | −0.00544 | −0.0407* | −0.0853** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.04) | |

| Working class (subjective) | 0.0917*** | −0.0254 | −0.0254 | −0.00226 | −0.0368*** | −0.00183 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Remainer | 0.151*** | −0.205*** | 0.0498*** | 0.0427*** | 0.0535*** | −0.0922*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Welsh Gov handled lockdown well | 0.179*** | −0.143*** | 0.026 | 0.0106 | 0.00541 | −0.0782*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

Results presented as marginal effects for ease of interpretation. Effect size should be interpreted as probability of voting for a party for a given person holding all other X at their mean. Standard errors in parentheses.

Levels of significance:

p = 99%;

p = 95%;

p = 90%.

Multinomial logit predicting party list vote choice (base outcome = Labour), N = 2,966.

| Variable . | Labour . | Conservative . | Plaid Cymru . | Green . | Liberal Democrat . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.0754 | 0.282*** | −0.0677 | −0.0782*** | −0.0235 | −0.0372 |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.05) | |

| Female | −0.0966*** | −0.0101 | 0.0287 | 0.000757 | 0.0158 | 0.0614*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Graduate | 0.0194 | −0.0743*** | 0.0273 | 0.0188 | 0.00719 | 0.00167 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Household Income | Reference = Less than £15k | |||||

| £15k–£29K | 0.00469 | 0.0361 | 0.00342 | −0.00666 | −0.0201 | −0.0175 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £30k–£49k | 0.0106 | 0.0595** | 0.0223 | −0.0186 | −0.0299* | −0.0439 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £50k–£99k | −0.0563 | 0.156*** | −0.0185 | −0.00152 | −0.0197 | −0.0597* |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £100K+ | −0.192*** | 0.181* | 0.132 | −0.0156 | −0.0454* | −0.0599 |

| (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Speaks Welsh | −0.0429 | 0.000846 | 0.105*** | −0.0362 | −0.048 | 0.0215 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.04) | |

| Born in England | −0.032 | −0.0241 | 0.0453* | 0.0368** | 0.0213 | −0.0473** |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Relative territorial identity | −0.0719 | −0.293*** | 0.497*** | −0.00544 | −0.0407* | −0.0853** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.04) | |

| Working class (subjective) | 0.0917*** | −0.0254 | −0.0254 | −0.00226 | −0.0368*** | −0.00183 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Remainer | 0.151*** | −0.205*** | 0.0498*** | 0.0427*** | 0.0535*** | −0.0922*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Welsh Gov handled lockdown well | 0.179*** | −0.143*** | 0.026 | 0.0106 | 0.00541 | −0.0782*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Variable . | Labour . | Conservative . | Plaid Cymru . | Green . | Liberal Democrat . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.0754 | 0.282*** | −0.0677 | −0.0782*** | −0.0235 | −0.0372 |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.05) | |

| Female | −0.0966*** | −0.0101 | 0.0287 | 0.000757 | 0.0158 | 0.0614*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Graduate | 0.0194 | −0.0743*** | 0.0273 | 0.0188 | 0.00719 | 0.00167 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Household Income | Reference = Less than £15k | |||||

| £15k–£29K | 0.00469 | 0.0361 | 0.00342 | −0.00666 | −0.0201 | −0.0175 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £30k–£49k | 0.0106 | 0.0595** | 0.0223 | −0.0186 | −0.0299* | −0.0439 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £50k–£99k | −0.0563 | 0.156*** | −0.0185 | −0.00152 | −0.0197 | −0.0597* |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| £100K+ | −0.192*** | 0.181* | 0.132 | −0.0156 | −0.0454* | −0.0599 |

| (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Speaks Welsh | −0.0429 | 0.000846 | 0.105*** | −0.0362 | −0.048 | 0.0215 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.04) | |

| Born in England | −0.032 | −0.0241 | 0.0453* | 0.0368** | 0.0213 | −0.0473** |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Relative territorial identity | −0.0719 | −0.293*** | 0.497*** | −0.00544 | −0.0407* | −0.0853** |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.04) | |

| Working class (subjective) | 0.0917*** | −0.0254 | −0.0254 | −0.00226 | −0.0368*** | −0.00183 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Remainer | 0.151*** | −0.205*** | 0.0498*** | 0.0427*** | 0.0535*** | −0.0922*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| Welsh Gov handled lockdown well | 0.179*** | −0.143*** | 0.026 | 0.0106 | 0.00541 | −0.0782*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

Results presented as marginal effects for ease of interpretation. Effect size should be interpreted as probability of voting for a party for a given person holding all other X at their mean. Standard errors in parentheses.

Levels of significance:

p = 99%;

p = 95%;

p = 90%.

In our model, we employ a relative measure of territorial identity (RTI), which measures how Welsh a respondent feels relative to how British they feel (see Henderson et al., 2021 for the derivation of this measure). This is a scale from zero to one, where one indicates a respondent feels very strongly Welsh but not at all British, and zero represents the opposite. We also include binary measures of subjective class identity (whether a respondent thinks of themselves as working class or not), and whether a respondent thinks of themselves as a Remainer or not (1, 0). This latter subjective measure is preferable to controlling for past vote as the 2021 survey includes a non-negligible number of respondents who were too young to vote in the 2016 referendum (N = 508). Because a substantial proportion of the Welsh population were born in England (26% according to the 2020 Annual Population Survey), we also include a measure of whether the respondent was born in England or not. These respondents are very unlikely to identify as being Welsh, but their Britishness is also quite distinct from the British identity of those born in Wales (Henderson et al., 2021; Henderson and Wyn Jones, 2021).

Finally, we include a measure of perceived government competence on responding to the coronavirus pandemic. The 2021 WES asked respondents for their perceptions of how both the Welsh and UK governments had handled three specific policy areas related to Covid-19: handling of lockdown, communication of decisions and the vaccine rollout. Perceptions of the Welsh Government’s handling of lockdown and communication was highly correlated (0.83), whereas there was very little variation between respondents’ perceptions of UK and Welsh government to vaccine rollout (respondents here were overwhelmingly positive). Given this lack of differentiation we therefore only include respondents’ perceptions of each government’s handling of the lockdown. All explanatory variables are standardised between 0 and 1, and summary statistics are provided in Table A1 of the Supplementary Appendix.

Several variables appear to have a consistent and substantial effect on vote choice in both the constituency and list vote. In particular, the models suggest that relative territorial identity (RTI), Remain/Leave identity, and competence evaluations all have a strong influence in shaping vote choice.

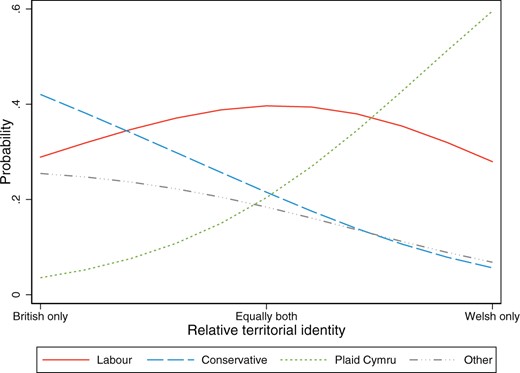

Focusing first on the importance of an individual’s RTI in shaping their vote choice, Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between respondents’ placement on the scale from ‘Strongly Welsh’ to ‘Strongly British’7 and their likelihood of voting for a given party in a constituency contest.8

Effect of relative territorial identity on constituency vote choice.

The resulting graphic reveals the starkly divided picture of electoral politics in contemporary Wales. While an individual’s national identity does not have a significant effect on whether they vote for Welsh Labour, it has a pronounced influence on their probability of voting for either the Conservatives or Plaid Cymru. Here, Plaid Cymru do extremely well among respondents with a strong Welsh and weak British identity, but extremely poorly among voters whose British identity is stronger than their Welsh identity. Conversely, the Conservatives do very poorly among strong Welsh/weak British identifiers and far better among strong British/weak Welsh voters. These marked effects are in stark contrast to the weaker effect of an individual’s national identity on voting for the Labour party: Welsh Labour performs relatively strongly across the whole spectrum of territorial identities. Indeed, the Labour vote is particularly strong among voters who feel a relatively strong attachment to both British and Welsh identities, a group which constitutes a majority of the electorate.

Figure 5 therefore offers an explanation not only of Welsh Labour’s performance in 2021, but for their strong performance at every election in Wales for the past century. Because Plaid Cymru and the Conservatives rely on support drawn from either end of the relative identity scale, national identity attachments act as a ceiling that drastically limits the gains that the opposition parties can expect to make at devolved elections. The fundamental importance of a voter’s self-determined national identity has been identified since the earliest political research carried out in Wales (Madgwick et al., 1973; Balsom et al., 1983, 1984) and has continued throughout the devolution era (Curtice, 1999; Wyn Jones and Lewis, 1999; Wyn Jones, 2001; Wyn Jones et al., 2002; Larner 2019).

In terms of short-term factors, voters’ perceptions of the Welsh Government’s handling of the Coronavirus pandemic were also associated with their vote choice. Positive competence perceptions were linked with a higher probability of voting Labour and a lower probability of voting for the Conservatives. This supports other work showing the importance of incumbency during a time of crisis and during the pandemic (e.g. Jennings, 2020).9 There was no association, however, between respondents’ Covid-19 competence perceptions and voting Plaid Cymru, because Plaid voters were relatively positive of Welsh Government’s handling of the pandemic even where they did not vote Labour at the election.

Finally, although the pandemic supplanted Brexit as the most salient issue at the 2021 devolved election, a voter’s Remain or Leave identity retained its importance as an electoral cleavage motivating vote choice. This occurred despite the substantial proportion of Labour Leavers who ‘returned’ to Labour as previously illustrated in Figure 4. Remain identity appears to be a particularly important distinguishing factor in the propensity to vote Labour or Conservative; effects for these parties were of considerably greater magnitude than for Plaid Cymru and other parties.

7. Discussion

The Welsh election of the 6 May 2021 delivered a vote of confidence in both Welsh Labour and the wider devolution project. This is, of course, significant in itself. But as we widen the optic to include consideration of the results of the elections that also took place in Scotland and in England on the same day, the Welsh result appears even more potentially momentous. For these were a set of elections that underlined the extent to which the politics of the three constituent territories of Britain (sic) are dominated by three different parties, each of which would appear to be national parties in sense that they enjoy majority support among the national group associated with that territory. The SNP is not only the dominant party in Scotland, but it is dominant among those who identify as Scottish (McMillan and Johns, 2021). In England, the Conservatives are not only the dominant party, but they too dominate among those who identify as English (Henderson and Wyn Jones, 2021). In Wales, Labour is, again, the dominant party while dominating also among those who feel Welsh, with the sole exception of those who reject Britishness outright.

If this analysis is correct, then this in turn creates major strategic dilemmas for Wales’ three main parties. For Welsh Labour, the dilemma relates to how it delivers on its ambitions without a significant Labour rebound in England and Scotland; two eventualities that currently look remote. In such a context, there is every likelihood that the Welsh Government ends up in an increasingly conflictual relationship with the UK Government of a kind that merely serves to highlight its own impotence. Never mind securing ‘home rule’; it may well find itself unable to resist the continual erosion of its current powers and standing. With one-third of the current Labour voters already supportive of independence,10 there is clearly a danger that such a scenario would only serve to drive more Labour voters (and party activists) in the direction of independence, eventually forcing the party to choose to follow their supporters or (potentially) lose them.

In structural terms, both the Welsh Conservatives and Plaid Cymru face the same fundamental challenge; namely, how to extend their support beyond the (very different) sections of the electorate that are currently predisposed to supporting them.

The first two decades of democratic devolution have twice seen the Welsh Conservatives fundamentally alter course. After fighting the first devolved election on what remained an anti-devolution platform, the party subsequently made a concerted effort to counter traditional notions that it is an anti-Welsh party or the English party in Wales. This was a matter both of presentation and substance, but (centrally) included adopting a much more positive attitude towards devolution. This was a process that reached its high-water mark with the passage of the Conservative sponsored Wales Acts of 2014 and 2017 which both further developed Wales’ devolution settlement. But even before then, it was obvious that the tide was turning. Many Conservative activists in Wales had never reconciled themselves to devolution, and they were joined by an increasingly significant group of Welsh Conservative MPs who were similarly sceptical. Post-Brexit, the star of the devo-sceptics has not just been in the ascendant, it is now placed more positive attitudes towards devolution very firmly in the shade. Wrapping themselves both metaphorically and literally in the Union Jack flag while presenting themselves as the only party that genuinely cares about the Union; claiming throughout the pandemic that everything was being better managed in England: the current crop of Welsh Conservatives have abandoned both the symbolism and the substance of the party’s previous efforts to appear more wholeheartedly Welsh.

There’s clearly an audience for this. The problem for the Welsh Conservatives is that, given the demographics that underpin voting behaviour in Wales, that audience is unlikely ever to be large enough to allow the party to come anywhere close to being able to govern alone. Moreover, by cheering on the UK Government efforts to undermine devolution, the party also ensures that it is unacceptable as a coalition partner. While it of course remains to be seen, it is also plausible to argue that 2021 represented the ideal circumstances for a Welsh Conservative party intent on making no allowances for Welsh national sentiment. It is hard to imagine that they will be repeated. The question for the party is, therefore, does it continue in the same vein, hoping that some combination of attrition and demographic change will serve to fundamentally alter its electoral prospect? Or can it yet conceive of another approach?

Plaid Cymru’s problem is that in almost every way but one, the profile of its support is extraordinarily similar to that of Welsh Labour voters. In terms of their relative positions on the left-right and liberal-authoritarian scales as well as in terms of patterns of national identity, the overlap between both sets of supporters is very substantial indeed. Even the differences with regards to the desired constitutional future for Wales are less substantial than might be imagined. The one thing that most clearly differentiates between supporters of the two parties is ability to speak Welsh, with Plaid Cymru tending to be the party of choice for those who can. Paradoxically, this is both a source of great strength for Plaid Cymru as well as a source of serial weakness. In constituencies where Welsh is widely spoken the party’s position is dominant. For a relatively minor party operating within an electoral system with an important first-past-the-post dimension, this serves the very valuable function of providing it with a solid, geographically concentrated base of support.

The difficulty arises from the party’s continuing inability to persuade those identify as Welsh but don’t speak the language—a group that is often, in fact, positively disposed towards it—that Plaid Cymru is a party for which they both could and should vote. This challenge is made all the more formidable by the fact that Welsh Labour is so comfortable with its own form of Welsh nationalism. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that Plaid Cymru has struggled to make the fundamental breakthrough that seemed possible after its very strong showing in the first devolved election in 1999.

A favourable change in the political weather for Plaid Cymru may require mistakes by Welsh Labour itself; either that, or for the UK Government to continue undermining the Welsh Government to the extent that it damages its credibility among Welsh Labour supporters. We have already briefly discussed the latter possibility. In terms of the former, an obvious potential point of inflection will occur when (as announced before the May 2021 election) Mark Drakeford steps down as First Minister at some point towards the end of the sixth Senedd. Thus far, three of the four Labour leaders in Wales since devolution have both embodied and embraced Welsh Labour status as both a national and a centre-left party. It remains to be seen if that pattern continues or whether, finally, Labour offers up a vulnerable flank which its opponents might exploit. But until that occurs, ‘Labour wins in Wales’ is likely to remain a recurring theme.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Parliamentary Affairs online.

Footnotes

Welsh Labour’s vote share increased substantially in Vale of Glamorgan, Delyn and Clwyd South—all of which are held by the Conservatives in Westminster—Llanelli—a once perennial Labour/Plaid Cymru marginal—and the party made considerable ground as challengers in Conservative held Preseli Pembrokeshire and Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire.

The figure is the same among 2021 Labour voters.

See, for example, Hodges , D. (31/10/20) ‘A land of fear and twitching curtains: DAN HODGES braves a visit to Wales after its Left-wing leader plunged it into lockdown’ Mail on Sunday, (available at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-8901413/DAN-HODGES-braves-visit-Wales-Left-wing-leader-plunged-lockdown.html)

Health has been a devolved matter since 1999.

Because Labour win nearly every single constituency seat in the three South Wales regions, the threshold required for them to win any of the four regional list seats is so large it is essentially impossible for Labour to win any of these seats.

The average figure between 1999 and 2016 was 3.5%.

Distribution of relative territorial identity provided in Figure A1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Analysis of list vote provides an almost identical graph. For ease of interpretation, we only provide a visualisation for constituency vote.

Although these perceptions independence from pre-existing identities is yet to be determined.

Several polls have suggested this number could be as high as half (e.g. YouGov/Yes Cymru, 2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the manuscript, and to Rachel Statham for her valuable feedback and thoughts.

Funding

The 2021 Welsh Election Study was supported by the Economic and Research Council [grant number ES/V009559/1].

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.