-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kieran Wright, Whatever Happened to the Progressive Case for the Union? How Scottish Labour’s Failure to Subsume a Clearly Left of Centre Identity with a Pro-Union One Helps to Explain Its Decline, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 75, Issue 3, July 2022, Pages 616–633, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsab014

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article presents an original account of the tactical options available to political parties in multi-level settings. It applies that framework to the case of post-devolution Scotland via an analysis of First Minister’s Questions sessions in the Scottish Parliament. It shows how Scottish Labour adopted a less left-leaning justification for its stance on the constitutional issue in the years after the party lost power at Holyrood to the Scottish National Party. Consequently, the party failed to present itself as a clearly left of centre alternative to the SNP and downplayed the progressive case for Scotland remaining in the UK.

1. Introduction

Recent studies of party competition in multi-level settings have argued that state-wide parties operating at the sub-state level ‘need clear answers to constitutional questions and national identity’ (Bennett et al., 2020, p. 16) if they are to compete effectively with regional nationalist opponents. This article argues that one way in which parties of that type can provide those clear answers is by justifying their policy on the constitutional question by referencing a position on the left–right axis that reflects their established policy identity. This is borne out of the idea that the language political actors use when justifying their policy stance, or attacking the position of their opponents, is an important element of the image they project to the electorate alongside the policies they argue for or the relative salience they give to each policy topic.

There is already evidence to suggest that the rhetorical justification for a policy position that political actors employ can significantly affect political outcomes. Certain types of rhetoric have been shown to be associated with electoral success (Zullow and Seligman, 1990; Jung, 2020). The type of rhetoric used by a US President in justifying a foreign policy intervention can limit the loss of popularity they experience should that intervention end in failure (Trager and Vavreck, 2011). Meanwhile, the use of a particular form of rhetoric can be helpful to ethno-religious groups in securing equal political rights (Krebs and Jackson, 2007, p. 48). In these examples, it is the political actor’s choice of rhetorical strategy as distinct from their choice of policy position or the relative salience they give to particular issues that is the crucial factor in determining the relevant political outcome.

This article explores the impact of rhetorical justification through an analysis of an example of party competition in a multi-level setting. In that type of setting, there exists a devolved tier of government with significant powers beneath the nation state level, and often a significant regional nationalist party operates within the region. In this type of context, party competition takes place along a territorial dimension where political actors debate whether power should be centred at the nation state level or within the region alongside the ubiquitous left–right axis of competition (Elias et al., 2015, pp. 842–843). Within that framework parties are able to adjust the position they occupy and the relative salience they give to each axis.

Existing work analysing party competition in that type of setting has argued that political parties have a subsuming strategy available to them in which parties frame their position on one of those two axes of competition by referencing their position on the other (Massetti and Schakel, 2015). For example, a regional nationalist party might argue that greater political autonomy for the region is the best route to implementing its preferred set of policies relating to the left–right axis. Regional nationalist parties are able to choose between a set of left- and right-leaning arguments for their position on the constitutional question depending on factors such as the economic circumstances of the region in which they operate (Massetti and Schakel, 2015, p. 873). Ideally, the twin themes that exist within a subsuming strategy should complement one another. So a left of centre regional nationalist party might subsume the twin themes that greater political autonomy for the region is good and left-wing policies are good by arguing that greater political autonomy would enable the region to adopt more left-wing policies than it is currently able to.

This article builds upon this conception of subsuming by distinguishing between positive and negative subsuming strategies. This distinction acknowledges one of the constraints political parties operate within when formulating strategy, namely the party’s established policy identity. Parties that project an image that varies too much from their historic policy positions, the values they have articulated in the past, and the core beliefs of their activists and prominent spokespeople, run the risk of damaging their credibility in the minds of voters. In positive subsuming the position referenced by the party’s strategy on both axes of competition is in line with this established identity. In the case of negative subsuming one of those positions is at variance with it. So in the case of a regional nationalist party with an established left of centre identity positive subsuming consists of the party projecting an image that is both regionalist and left of centre. Were the same party to project an image that is regionalist and right of centre only one of those would be in line with its established identity, so that would constitute negative subsuming.

Established policy identity can be seen as similar to issue ownership (Petrocik, 1996) as an aspect of the general perception voters have of a political party’s brand. However, while issue ownership as initially conceived relates to voter judgement of the extent to which a party has the level of competence necessary to handle a particular policy issue (Petrocik, 1996, p. 826), established policy identity is more matter of the credibility and consistency over time of a party’s policy stance. Just as the identity of the party seen as owning a particular issue can change over time (Walgrave and Lefevere, 2017), established policy identity can change with negative subsuming being one of the tactical devices parties might use in pursuit of that objective.

A party might choose to negatively subsume when it perceives that its established stance is on the wrong side of public opinion, or when it feels that projecting a policy identity more similar to that of an opponent might help it in valence terms. An example of the latter might be a party with an established left of centre policy identity opposed by a centre-right party that appears to have an advantage over it in terms of public perceptions of economic competence adopting some of the languages of fiscal rectitude in an attempt to neutralise that advantage.

In a setting where the twin axes model of party competition operates, parties might attempt to alter their established policy identity by reducing the extent to which the image it projects to the electorate is in line with its existing identity on one of those axes. This could form part of the tactical response of a state-wide party to a perceived increase in the electoral threat posed by a regional nationalist opponent. In the mid-1970s, the Labour Party in Scotland adopted precisely this strategy. Having been internally divided over the issue (McLean and McMillan, 2005, pp. 162–165), the party leadership came out in favour of devolution after the February 1974 UK election in response to a perception that the SNP posed an increased threat (McLean and McMillan, 2005, pp. 184–185). This shift over time enabled the party to establish a policy identity that was pro-devolution as well as opposed to the SNP’s central policy of independence.

Both the positive and negative subsuming strategies have a set of risks and potential rewards associated with them. The former provides a route by which a party can build a stable, non-diffuse support base (Brand et al., 1994, p. 617) but can be risky if an aspect of its established policy identity is unpopular with a significant segment of its target market. Meanwhile, negative subsuming provides a route by which a party can address negative aspects of its established policy identity on one axis while maintaining credibility by continuing to reference what might be a less problematic established identity on the other. At the same time, there are potential risks associated with any type of policy accommodation with those who do not share a party’s fundamental policy objectives (Meijers and Williams, 2020).

2. Method

This article tests the utility of the distinction between positive and negative subsuming by analysing the strategy pursued by the Scottish Labour Party in the first two decades of the 21st century. It aims to establish the extent to which such a framework represents an accurate depiction of the strategic options available to parties operating in a comparable setting, and provides an assessment as to the potential risks and rewards associated with parties pursuing either of the two strategies.

The first two decades after the introduction of devolution for Scotland at the end of the 20th century was the setting for a dramatic turnaround in the electoral fortunes of the main Scottish political parties. Scottish Labour declined from a position of electoral dominance in the country to being merely the second-largest opposition party in the Scottish Parliament facing a Scottish National Party administration. This makes post-devolution Scotland an ideal case for analysing the consequences of the strategic choices parties make in a multi-level setting.

The study focuses on sessions of First Minister’s Question Time as an example of parliamentary question and answer sessions, beginning with the very first sessions of that type that took place the year after Scottish devolution was introduced in 1999 and ending with the last session that took place prior to the 2016 election. It is during this period that the dramatic decline in the electoral fortunes of the Scottish Labour Party referred to above occurred. This article argues that parliamentary events of that type represent an arena in which the elected representatives of political parties implement various rhetorical strategies with the aim of projecting a particular image to the electorate. There is much evidence to support the notion that parties approach those sessions with that type of objective in mind (Datta, 2008; De Saint-Laurent, 2015, p. 45; Spirling, 2016; Otjes and Louwerse, 2018, p. 509). The media coverage these sessions receive means that the leadership teams of the major parties spend a substantial amount of time preparing for them in the hope that they can gain exposure for their take on the issues of the day (Hazarika and Hamilton, 2018, p. 47).

The method employed involved tagging the written record of FMQs sessions for the period studied by the party affiliation of the speaker in order to separate the contributions made by Labour representatives from those of other speakers using the Nvivo software package. The Labour portion of the text was then coded to highlight instances where a Labour representative was making an argument relevant to the constitutional issue. This text was then subjected to a further process of coding that highlighted whether that position was supported with arguments redolent of the left or right side of the left–right axis. This in turn makes it possible to judge the extent to which party representatives are at any particular time utilising the negative or positive subsuming strategies outlined above.

Scottish Labour in the early part of the post-devolution period framed elections to the Scottish Parliament as contests between social justice and separatism, and spoke of Scottish politics as being a contest between ‘nationalists and internationalists’ (Hassan, 2009, p. 156). The party also emphasised the cultural ties inherent in the union, and frequently spoke disparagingly of ‘narrow nationalism’ (Hassan, 2009, p. 157). In questioning the progressive credentials of its main regional nationalist opponent in this way, Labour can be said to be engaging in positive subsuming as the party is justifying its stance on the constitutional issue and attacking that of its main opponent by referencing its established progressive, left of centre policy identity. In deploying this line of argument Labour as a left of centre, anti-independence party is projecting an image on each axis of competition both of which are in line with the party’s established policy identity.

There is, however, another set of arguments often put forward by those opposed to the SNP’s core policy based on the economic viability and/or desirability of Scottish independence. This article argues that deploying those arguments is a risky strategy for a party of the centre-left as it would be criticising its opponents in the way that parties of the right often criticise parties of the left, accusing them of adopting a policy that would leave them unable to fund their spending commitments without tax increases or cuts to other public services. This type of accusation of economic illiteracy represents a staple line of attack for parties of the right directed towards parties of the left. Consequently, it is legitimate to argue that a left of centre party deploying this type of argument is engaging in a form of negative subsuming. The party is articulating a stance on both axes of competition only one of which is in line with its established policy identity. Employing the method described above will highlight the rhetorical strategy Labour employed in relation to the constitutional question, and enable an assessment to be made as to the extent of its use of the positive or negative subsuming strategies over the course of the period studied.

For several decades prior to losing power at Holyrood to the SNP in 2007 Labour dominated the Scottish political scene. It is therefore legitimate to expect the party to have become accustomed to holding power in Scotland, and for the shock of losing power to have elicited a tactical response. This may well bring in to play the established tendency of parties to shift position after losing power (Schumacher, 2015). There is also evidence to suggest that poor electoral performance is associated with more moderate position taking (Schumacher and Elmelund-Præstekær, 2018, p. 344). In the context of a twin axis model of party competition, this means a party losing office will become less likely to project an image entirely in line with its established policy identity. Consequently, the party would be less likely to be seen to have followed the positive subsuming strategy outlined above. This leads to the hypothesis this study will investigate:

Hypothesis: Parties operating in a setting where party competition takes place on the twin axes model become less likely to utilise a positive subsuming strategy after losing power.

3. Results

Labour’s strategic approach between 2000 and 2016 can broadly be divided into three periods. Prior to 2007, it was characterised by the party framing its stance on the constitutional issue with reference to its established policy identity on the left–right axis in the manner envisaged by the positive subsuming strategy. It argued that remaining in the UK was the best way of Scotland benefitting from progressive, left of centre policies. It also characterised independence as a distraction from the pursuit of progressive goals, and a policy that would leave Scotland as a diminished presence on the world stage. As an example of the latter line of argument, Labour argued that an independent Scotland would be damaged as a result of not being able to access the network of UK embassies and consulates around the world:

That network [of Scottish Development International offices] ensures that we in Scotland have direct representation in many countries throughout the world. We also have the benefit of direct Scottish representation through the many British embassies and consulates. Of course, the direct impact of [the SNP’s] political position would be that we would no longer have access to 200 or so embassies and consulates and Scotland’s industries and companies would lose out First Minister Jack McConnell MSP (Lab). SP OR 14 April 2005 Col 16041

The party also scorned the parochialism of the SNP in questioning the cost associated with ensuring adequate security when in 2005 Scotland hosted a summit of the leaders of the G8 group of leading industrialised nations rather than celebrating what the presence of a group of world leaders said about Scotland’s relevance on the world stage:

I have to say that, given the importance of the issues that will be debated at the summit and given the importance of bringing the world’s top table to Scotland, the Scottish National Party’s ability to revert to an introverted, insular and inward-looking position and to be concerned about any potential for the odd penny to go astray in Perth and Kinross Council or Angus Council is depressing for Scotland. Nationalist parties the world over would be delighted with the opportunity to have the world’s leaders on their nation’s doorstep. We in the Labour Party…are delighted that those leaders are coming to Scotland: I wish only that the SNP, too, was delighted First Minister Jack McConnell MSP (Lab) SP OR 19 May 2005 Col 17039.

Labour also argued that Scotland had heightened influence within the European Union as a result of it being part of the UK:

It is precisely because of the way in which Scotland’s interests have been represented over the eight years of devolution, in this devolved Government and at UK level, that we have seen the many successes through changes in European Union legislation and decisions that have been important to Scotland First Minister Jack McConnell MSP (Lab) SP OR 25 January 2007 Col 31576.

The party also framed its anti-nationalist stance as supporting the best route by which Scotland could enjoy the benefits of progressive, left of centre policies. In an archetypal example of positive subsuming, Labour argued that Scotland was better able to tackle the issue of child poverty as part of the UK, and that focus on the constitutional issue would be a damaging distraction in that respect:

The actions of this devolved Government and of the United Kingdom Government over the past 10 years have made a significant difference to child poverty in Scotland. We are leading the way in the UK in tackling child poverty and if members had any soul, they would be proud of that. The reality is that we have lifted more than 100,000 Scottish children out of relative poverty and more than 200,000 of them out of absolute poverty in those years. We know that one in three people in Scotland lived in poverty in 1997, but today only one in four live in poverty, and that figure is coming down year after year.

Those are the solutions, not the nonsense that we get from the Scottish National Party, which, rather than tackling child poverty and giving people the education that lets them get on in life, wants to waste all its efforts over three or four years on an independence bill and a referendum First Minister Jack McConnell MSP (Lab) SP OR 18 January 2007 Col 31364.

Losing power to the SNP in May 2007 appears to have prompted Labour to rethink its strategy. Having argued what could be described as the progressive case against the SNP’s stance prior to that year’s Holyrood election the party shifted towards that of the SNP and came out in favour of an immediate referendum on independence. Then Labour Leader Wendy Alexander during one session in early 2008 asked SNP First Minister Alex Salmond ‘The First Minister has been a nationalist all his political life. I am giving him the opportunity to resolve this issue. Why will he not take it?’ She went on to say:

I have no doubt that the judgment of history will be between those, such as me and my colleagues, who wanted to let the people speak and those who wanted delay in order to foment grievance and to fray the relationship, because they feared the result. The uncertainty is damaging our country. Uncertainty costs jobs. Last night Iain McMillan of the Confederation of British Industry Scotland said that it was time to lance the boil. I have offered Labour’s support for an early referendum. The First Minister has spurned that offer. Why will he not bring the bill on? Wendy Alexander MSP (Lab) SP OR 8 May 2008 Col 8425-8426.

This attempt at policy accommodation with the SNP never had the necessary support within the Labour Party for it to become a consistent line of attack (Hassan and Shaw, 2012, p. 133). Consequently, the approach was short lived with Labour instead of switching to a third strategy. Rather than attacking the fundamental ideology behind the SNP’s stance, Labour increasingly focused on questioning the potential economic cost of independence. This line of attack forms an increasingly prominent theme evident in the written record of FMQs sessions, particularly in the years after the SNP won an overall majority at Holyrood at the 2011 election. In the early 2013, Wendy Alexander’s replacement as Labour leader Johann Lamont attacked the idea of independence on the basis that it would leave Scotland ill prepared to mitigate the effects of economic shocks such as the global financial crisis of the latter part of the first decade of the 21st century.

The last time that our banking sector hit crisis, a Labour Government immediately rescued our banks so that ordinary families in this country could still get money out of the cashpoints. That included Scottish banks, of course. There was no question, no hesitation and no negotiation. It was the kind of action that the Greeks and the Irish can only dream of. Our banking system was saved by one of the most successful economic unions in history—the United Kingdom. Is not the real lesson of the euro crisis that you cannot share a currency and have monetary union without a fiscal union and a political union? Opposition Leader Johann Lamont MSP (Lab) SP OR 24 May 2012 Col 9364.

One prominent theme in the increased focus on the economy in Labour’s attacks on the SNP was the issue of what currency an independent Scotland would use. The currency issue represented an important line of attack as it was an issue that all on the unionist side perceived the SNP to be vulnerable on. In unionist eyes, an independent Scottish state would be choosing from a set of equally unappealing options in this respect involving either using an existing currency (Sterling or the Euro) with the negative implications for Scottish sovereignty that would entail, or setting up a new currency. The latter is a course of action not without its difficulties, and one that had little support within the SNP leadership at the time of the FMQs session referenced above (Mitchell et al., 2012, p. 122).

On one occasion the following year Lamont did attempt to give a left-wing flavour to an attack based on the currency issue by arguing that continuing to use sterling post-independence would give more power to the government of the remaining UK, and therefore potentially more power to a Tory government.

That is the difference between Alex Salmond and me. I want to get rid of the Tories and keep the union; he wants to get rid of the union and keep the Tories in charge of the economy Opposition Leader Johann Lamont MSP (Lab) SP OR April 25th 2013 Col 19019.

However, later in the same session, she reverted to a more financial-based critique without that kind of progressive flavour arguing that the SNP’s plan for independence had the potential to plunge Scotland into a sovereign debt crisis.

John Swinney told the BBC that Scotland might leave the United Kingdom without paying any debts at all. It seems that while there are some who say that an independent Scotland might end up like Greece, John Swinney wants us to start off like Greece, by defaulting on our debts Opposition Leader Johann Lamont MSP (Lab) SP OR April 25th 2013 Col 19020.

In response to this, the SNP adopted a strategy of trying to damage Labour’s left of centre credentials by pointing to the fact that they were occupying the same side of the argument as the Conservatives on the constitutional issue (SP OR 25 April 2013 Col 19020). The latter exchange was more or less repeated in the following week’s session (SP OR 2 May 2013 Col 19308–19312), with SNP Leader and First Minister Alex Salmond noting the distinct similarity in the arguments being put forward by Labour and Conservative representatives when raising the constitutional issue (SP OR 2 May 2013 Col 19314).

During one FMQs session in March 2014 (the year the referendum on independence took place) Lamont again focused on economics referring to a recent decline in the amount of tax raised via the oil industry asking ‘if Scotland were independent, how would the First Minister cope with that revenue drop—by cutting services or by raising taxes?’ (SP OR 13 March 2014 col 28900). In doing this, Labour was adopting a form of the negative subsuming strategy outlined above attacking the SNP in the same way that parties of the right often attack parties of the left; accusing them of adopting a set of policies that are economically incoherent. Similarly, the party also accused the SNP of being anti-business as a result of its stance on independence.

This week Alex Salmond, John Swinney, and Nicola Sturgeon have been asked repeatedly to put a figure on the transaction costs to Scottish business of giving up the pound in the event of a yes vote, but they have refused to come up with an answer. The Scottish Parliament information centre has come up with some numbers. Transaction costs for the rest of the UK—the so called George tax—work out at £9 per head for people in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. However, if the Scottish Government’s own figures are to be believed, the cost in Scotland would be £75 a head, which is eight times greater. No wonder they would not answer the question. Given that that would be the consequence of the First Minister’s plan to break up the United Kingdom, why should Scottish business pay the Alex tax? Johann Lamont MSP (SP OR February 20th 2014 Col 27959).

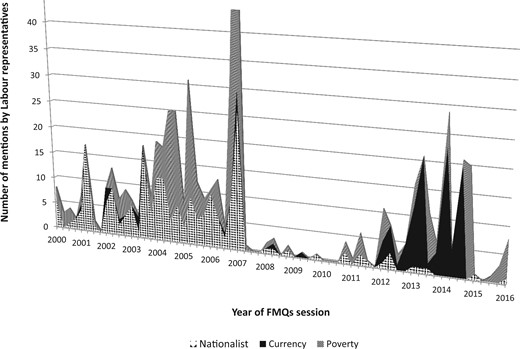

An illustration of the three broad strategic approaches Labour adopted in FMQs sessions over the course of the period studied can be gained by conducting a count of the number of times certain keywords occur within the written record of Labour contributions using the stemmed text search query function offered by Nvivo. An important part of Labour’s pre-2007 strategy of challenging the ideological basis underpinning the SNP’s pro-independence stance was referring to the latter by the ‘nationalist’ label that the party looks to distance itself from (Cramb, 2017). This makes a simple count of the number of times the party’s representatives used that term one way of tracking the extent to which Labour adopted that strategy. Similarly, tracking use of the term ‘poverty’ provides an indication of the extent to which party representatives used language redolent of the party’s left of centre policy identity. That word is traditionally used disproportionately by those on the left of the political spectrum, as evidenced by the fact that it is included in the left-wing section of the main dictionary formulated to measure left–right positioning in the context of British politics (Laver and Garry, 2000). Meanwhile, use of the word ‘currency’ provides an indicator of the extent to which Labour adopted the strategy referred to above of questioning the economic viability of Scottish independence by referring to the issue of what currency the newly independent country would adopt. This query was run on the text being analysed after the written record for each year had been divided into four quarters based on the date the FMQs session took place. This generated four counts for each word for each full year.

The results presented in Figure 1 clearly show the party frequently using the terms ‘poverty’ and ‘nationalist’ in the period up to and including 2007. This indicates that the party frequently supplemented its attack on the SNP’s stance for being anti-progressive with allusions to Labour’s left of centre identity. The passage quoted above relating to child poverty provides a clear example of this. Incidence of both of those terms declines dramatically in the years immediately after 2007, the period when Labour adopted its short-lived strategy of demanding a referendum on independence. Beginning in 2011, the use of the term ‘poverty’ begins to rise again; however, there is no accompanying increase in the use of the term ‘nationalist’. Labour appears to have not returned to its pre-2007 strategy of attempting to associate the SNP with a non-progressive ideology, instead use of the term currency increases indicating that the party increasingly adopted the strategy of criticising the SNP’s stance on economic grounds.

Number of uses of the terms ‘nationalist’, ‘currency’ and ‘poverty’ by Labour representatives during First Minister’s Questions Sessions in the Scottish Parliament 2000–2016

On losing power at Holyrood, Labour seems to have abandoned a critique of independence centred on it being an inward-looking project that would be a distraction from pursuing progressive goals in favour of a set of arguments increasingly centred on economics. In doing so, the party can be said to have switched from a positive subsuming strategy in which it justified its stance on the constitutional issue by referencing a left of centre, progressive stance on the left–right axis of competition in line with its established policy identity to a negative subsuming strategy in which the language it used justifying its position on the independence question became more right leaning.

Consequently, the hypothesis outlined above predicting that parties are less likely to utilise positive subsuming after losing power receives some support. Losing power does seem to have led Labour to undertake a radical reassessment of its strategic approach. Positive subsuming was replaced with negative subsuming with the result that the party’s pro-centre, left of centre identity became less clear and the party decreased the extent to which it argued the progressive case against the SNP’s core policy.

4. Discussion

The findings presented in this article point to the importance of loss of incumbency as a factor influencing the strategic choices political parties make. The study focuses on the strategy pursued by the party elite at devolved level; however, there is reason to believe that the change in incumbency position at Westminster in 2010 when a Labour government was replaced by a Conservative-led administration also had a significant effect. Extolling the positive benefits of Scotland’s position as part of the UK is likely to have come more naturally to Scottish Labour when in doing so it was also talking up the record of a Labour administration in Westminster. Attacking a Conservative administration at UK level while continuing to support Scottish membership of the UK represents a difficult tactical balance when the party’s principle opponent is arguing that independence offers Scotland an obvious escape route from Tory rule. The evidence presented in this article suggests that Labour fell short of striking that balance.

While the party successfully deployed the negative argument that independence would hinder the achievement of social democratic goals it failed to make the positive case as to how those goals could be more effectively pursued by a left of centre party holding power at UK level. The impression created is of a party that acted as though Conservative rule at Westminster had become a fixed aspect of the political landscape with the consequence that it stopped telling the Scottish electorate how Labour could pursue social democratic goals more effectively than the SNP were they in power at UK level.

Labour’s deployment of negative rather than positive arguments against the SNP is one reason why it is legitimate to argue that the party's leading spokespeople used language that made their party sound less convincingly left of centre than the SNP. Existing research has detailed how political actors from the right are more likely to use negative language than those from the left (Sylwester and Purver, 2015; Wojcik et al., 2015; Turetsky and Riddle, 2018). Left of centre politicians tend to talk positively about their ability to deliver improvements to public services. Right of centre ones on the other hand emphasise the financial constraints within which the objective of better public services must be pursued. This article argues that this type of subtle difference in language can have a significant impact in cases such as that of Labour and the SNP where there is a long-standing view among voters that the parties are close enough together ideologically that switching between the two does not represent a huge shift in political identity (Brand et al., 1994).

The negativity of many of the arguments Labour deployed can also be seen as undermining any attempts by the party to portray itself as being at least as pro-Scottish as the SNP. In focusing on things Scotland would not have as an independent country rather than on what it could have as a part of the UK Labour ran the risk of sounding overly pessimistic regarding Scotland’s future potential. This trap of failing to use language that highlights sub-state national identity in a positive way is one that Scottish Labour’s Welsh counterpart has not fallen into (Bennie and Clark, 2020). Taken together the Scottish and Welsh cases emphasise the importance of incumbency status. A Welsh Labour Party in government seemingly finds it easier to project this type of positive identity than a Scottish Labour Party that needs to strike a balance between attacking the Scottish Government while still being seen as pro-Scottish.

The negative aspects of the strategy pursued by Labour in opposition at Holyrood were emphasised by the SNP at the same time pursued a positive subsuming strategy, as exemplified by the following extract from one FMQs session:

One thing indicates the difference between our approach to public services and the approach that Margaret Thatcher’s Government pursued and Gordon Brown’s Government is pursuing: we believe—and we will hold to this—that we can make those efficiency savings across the public sector with no compulsory redundancies. The trade unions appreciate that deeply, just as they deprecate the policy that has been introduced from Westminster

First Minister Alex Salmond (SP OR April 17th 2008 Col 7688).

This shows the SNP questioning Labour’s left of centre credentials at the same time as expressing hostility to rule from Westminster. The SNP’s use of positive subsuming intensified in the years after the party won a majority at Holyrood in 2011 and successfully legislated for a referendum on Scottish independence. It adopted a strategy of questioning Scottish Labour’s progressive credentials by associating them with the Conservatives on account of the two parties occupying the same side in the constitutional debate. In one FMQs session in 2013, the SNP claimed that Labour had effectively gone into coalition with the Conservatives in joining with them in the Better Together campaign, arguing that the party would ‘…pay the highest price for their joint cabal and campaign with the Conservative Party’ (SP OR 18 April 2013 Col 18727).

There is evidence to suggest that the type of image Labour and the SNP projected during FMQs sessions during the period studied had some effect on public perception of the respective parties’ policy identity. Polling from 2011 shows Scottish voters placing Labour to the left of the SNP (Carman et al., 2014, p. 94), but later data from the British Election Study show that the Scottish electorate came to see the SNP as a more convincingly left-wing party than Labour in the years after the 2011 election. In 2014 and 2015, several waves of the BES panel survey asked respondents to scale the main Scottish parties on a left–right axis. In May to June 2014, wave respondents on average rated Labour as the most left-wing of the major Scottish parties, however, in subsequent waves when the question was included Scottish voters rated the SNP as the most left wing (Fieldhouse, 2014a,b; Fieldhouse, 2015).

This polling covers the period around the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence in which Labour’s association with the critique of the idea of Scottish independence based on economics that it used in FMQs sessions would have been particularly prominent. The effect of Scottish voters beginning to doubt whether Scottish Labour represented the most left-wing option available to them on the party’s electoral performance from 2015 onwards in its traditional heartlands was devastating. This article argues that the language used by the party elite at the sub-state level played a part in this shift in public perception. Other factors that fall outside the scope of this study may also have played some part, perhaps most significantly the language used by the party elite at UK level. Generally, the effect the language used by different political actors has on public perceptions of party positioning represents a possible avenue for future research into how voters form judgements about political parties.

Recent research does support the notion that the rhetoric use by party representatives can influence public perception of party positioning (Somer-Topcu et al., 2020). This study argues that the distinction between positive and negative subsuming provides one explanation as to how those two variables might be linked in cases where the twin axes model of part competition operates. Where a party is able to project an image in which its identity on both axes of competition reinforce one another, and where both are in line with the party’s established policy identity, it increases the chances of voters perceiving its message as being coherent and credible. It may also increase its chances of appealing to a range of voters with different ideological affiliations. A subsumed left of centre pro-periphery appeal for example is well placed to attract all voters who do not have a strong preference for right-wing and/or pro-centre policies. Voters who have a weak preference for either of the latter two positions are open to being won over by a subsumed appeal in a way that they might not be where the left of centre and pro-periphery messages delivered without each position complementing one another in the manner envisaged in a positive subsuming strategy.

Further research is needed to clarify why this might be the case, but there are a couple of possible explanations. First, voters are likely to view a party that appears to be appealing to a broad section of the country’s population positively in valence terms as it gives the impression of it being a party prepared to govern in the interests of the whole country. There may also be an element of confirmation bias at work in which voters who are open to being persuaded to support a range of parties have a tendency weigh elements of agreement with a party’s message more heavily than elements of disagreement when multiple messages are presented together.

The results presented here placed in the context of the relative electoral performance of Labour and the SNP in post-devolution Scotland show the potential benefits of a positive subsuming strategy and the pitfalls of a negative one. Research on the impact of the referendum on Scottish independence has detailed how in its aftermath referendum voting choice became increasingly aligned with party support (Fieldhouse and Prosser, 2018, p. 19). This process has worked to the benefit of the SNP and to the detriment of Scottish Labour as the significant pro-independence segment of that latter’s support base has switched to the SNP. This article argues that this process has been partly driven by the SNP’s effective use of the positive subsuming strategy and Labour’s use of negative subsuming. By successfully subsuming pro-independence arguments with left of centre ones, the SNP managed to broaden its appeal beyond its traditional pro-independence base to encompass voters with a preference for left of centre policies that weighed more heavily than their preference for preserving the union.

Labour’s strategy on the other hand had the effect of diminishing its pool of potential voters. On losing power at Holyrood the party appears to have downplayed the progressive case for the union relying increasingly on dry, economic justifications that undermined its image as a clearly left of centre, progressive party. This played into the hands of the SNP who had for some time adopted a strategy of questioning Labour’s ability to live up to its social democratic principles (Newell, 1998, p. 114). Labour’s strategy post-2007 left a gap in Scottish political discourse where the progressive case for the union was underplayed, allowing the SNP to make the case that independence constitutes the more progressive option on the constitutional issue largely unchallenged.

There is some evidence to suggest that Labour made a belated attempt to pursue a positive subsuming strategy as opinion polls during the 2014 referendum campaign suggested independence was a realistic prospect, with the party emphasising ‘…the importance of unity for the achievement of social democratic goals in the Labour tradition’ (White, 2015, p. 107). This article argues that the party could have made more of this type of argument during the preceding years. Instead the party allowed the impression to develop that left of centre polices could be best pursued following Scottish secession. The example of the separation of the former Czechoslovakia into its component parts demonstrates the danger of a significant number of voters coming to believe that they can only have the economic policies they want via territorial secession. In that example Slovak voters hostile to free market reforms introduced after the collapse of Communism came to feel they could only bloc those reforms by seceding from Czechoslovakia, and this happened despite their being little evident pre-existing desire for Slovak independence (White, 2015, p. 109). The fate of Czechoslovakia shows that multi-national states only survive where there is maximum potential for political contestation to take place within the existing constitutional framework. In the Scottish context, this means that the SNP’s positive subsuming strategy of characterising social democratic goals as best attainable in the context of an independent Scotland must not go unchallenged. Scottish Labour’s role must be to provide that challenge. It must be to argue the positive, progressive case for the union.

Funding

The author received no specific funding for the research detailed in this submission.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflicts of interest statement to report.