-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David Cutts, Andrew Russell, Relevant Again but Still Unpopular? The Liberal Democrats’ 2019 Election Campaign, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 73, Issue Supplement_1, September 2020, Pages 103–124, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsaa024

Close - Share Icon Share

The year 2019 was supposed to be the year of the Liberal Democrats’ rehabilitation. They had apparently emerged from the long, dark shadows cast by their coalition with the Conservatives, and their electoral trouncing in 2015 and poor showing in 2017. They had enjoyed a period of stability, and remarkable progress, under the leadership of Vince Cable who inherited a party that had been worn down to a husk. As Labour shifted to the left and the Conservatives chose full-on Euroscepticism and inner turmoil, the Liberal Democrats started to grow. A rearguard action in local government, European Election success and victory in a Westminster by-election saw off a centre party threat seeking to claim their territory. Brexit—and the need to stop it—was the party’s passport back to the top table of British politics. When Cable stood down as leader, he was succeeded by a candidate who seemed to fit the bill for what the party most desired. Jo Swinson was young, female and had a reputation in the Westminster circle for competence and empathy. Under Swinson, the Liberal Democrats grasped the opportunity with both hands to reinvent themselves as the only GB wide, unambiguously anti-Brexit party. With pre-election polls placing them on the coattails of Labour, the Liberal Democrats then went for the jugular. Swinson began the campaign in spectacularly upbeat fashion, reasserting that a majority Liberal Democrat government would revoke Article 50 and announcing that she was running to be the new Prime Minister. A few weeks later, the party’s campaign had turned to ashes, the number of Westminster Liberal Democrats actually fell and Swinson herself, for the second time in four years, lost her own seat to the Scottish National Party (SNP). Everything that might have gone wrong went spectacularly awry. So what was to blame for the Liberal Democrats’ failure to sustain pre-election expectations? Why in the so-called ‘Brexit election’ did the party whose raison d’être was to stop Britain leaving the European Union (EU) fail to make significant electoral headway? Why did the Liberal Democrats get their political and electoral strategy so badly wrong? We examine what happened and why and assess whether this represented another missed opportunity, or whether the failings of the campaign mask the underlying story of slow, relative and partial, recovery in Liberal Democrat fortunes.

1. Building momentum

After Tim Farron’s resignation, Sir Vince Cable was elected unopposed as leader, with the unenviable task of reconnecting with an increasingly polarised and divided electorate. The Cable era can be divided into two parts. Initially, Cable was keen to play the ‘statesmanlike’ card by making a virtue out of his longevity in public life. On Brexit, for instance, he immediately painted himself as the ‘political adult’ in the room and while ruling out formal pacts with the others sought to call out ‘sensible grown-ups’ from both parties who shared his and the party’s position to keep Britain in the single market and customs union. He recognised that the party needed more media exposure to rally the troops and sought to provide clearer political messaging and policy positions in order to keep the Liberal Democrat badge in the forefront of public debate and people’s minds. Yet, despite all the positive rhetoric, optimism and denial that he was merely a short-term caretaker, the reality was something different. The first 18 months of Cable’s leadership was pedestrian, lacklustre and did little to raise the party’s profile. The Liberal Democrats poll rating barely moved much above 8% while the 2018 local election results were, in terms of its nationwide share of the vote, one of the worst local election performances by the Liberal Democrats since their formation. Unsurprisingly, a year on from becoming leader, Cable confirmed that he would stand down after Brexit was resolved or stopped and after he had transformed the inner workings of the party. Yet, writing off Cable proved to be premature.

During the first half of 2019, both the Conservatives and Labour hit internal strife and showed signs of fracturing as they faced increasing public derision over Brexit. When the inevitable happened, the new Independent Group of 11 MPs was vocal in expressing their desire not to join the Liberal Democrats, claiming the party brand had been damaged by coalition with the Conservatives. Cable responded in a measured manner, calling for electoral alliances around shared interests such as a second Brexit referendum but noted the structural electoral hurdles for two centrist parties competing for the same voters. His decision in mid-March to step down after the local elections, to make way for a new generation, simultaneously enabled the party to talk about renewal and a fresh start but strategically was designed to offset the novelty of its new centrist opponent. And with Change UK not standing in the local elections and Brexit dominating political discourse, the door seemed ajar for the Liberal Democrats to make a political statement.

Over the next month, the Liberal Democrats not only gained significant electoral impetus but also they mortally damaged their Centrist adversaries. First, through local election success—704 net gains and 12 councils—the party won 16% of seats up for election, with 1,351 councillors returned and now controlled 23 councils, its highest number since 2010. With visibility increasing, a seemingly decisive shift in the national polls occurred. The Liberal Democrats immediately sought to build on this through the launch of their European election manifesto and campaign slogan, ‘Bollocks to Brexit’, which generated even more media exposure. Like the local elections, it was the Liberal Democrats that cannibalised the pro-Remain vote in the European elections, winning 16 seats, its largest number since 1979. With 3.4 million votes and 20% of the national vote, the party topped the poll in London and was the largest party in 44 local areas, 29 of which were in the capital and the South East. Cable passed the baton onto Swinson with the Liberal Democrats seemingly back in the electoral fight.

2. Swinson: shifting position

Emboldened by the legitimacy given to it from pro-Remain supporters in local and European elections, a record membership of 120,000 and the subsequent considerable uptick in national polls, the Liberal Democrats became increasingly visible and garnered far more national media attention. Swinson hit the ground running with success in the Brecon and Radnorshire by-election while defections from Change UK and, in time, from three Conservative MPs who crossed the floor of the House also provided publicity and a legitimacy boost.

From the early days of Swinson’s leadership, there were two distinct shifts from the Cable regime. On becoming leader, Swinson unequivocally set out her stall to ‘Stop Brexit’ and remove any ambiguity about the Liberal Democrats’ pro-Remain credentials. Part of the reasoning was to exploit the uncertainty around Labour’s ‘renegotiation strategy’ position and their shift towards a ‘second referendum’ position with strings attached. As a consequence, the Liberal Democrats signalled to Remain voters that they would revoke Article 50 if they won outright power and would revert to supporting a second referendum with a Remain option if they fell short.

The Liberal Democrats also adopted an unambiguous equidistance stance to lure recruits from both Labour and the Conservatives by ruling out supporting a Johnson- or Corbyn-led administration. Compared to Cable, Swinson also ‘ratcheted up’ the anti-Corbyn tone and rhetoric. She consistently dismissed a Corbyn-led caretaker government to avoid a no-deal Brexit and instead put forward other alternative caretaker PMs. Eyeing disenchanted Labour voters, Swinson went beyond Corbyn’s reluctance to back a second referendum. She also signposted the Labour leadership’s handling of anti-Semitism and its damaging economic policies, while portraying Corbyn as a threat to national security, using examples of his response to the Salisbury poisoning incident and support for authoritarian regimes.

Both the Revoke policy and the rigid equidistance stance represented political gambles. Each risked alienating potential Conservative and Labour tactical switchers. They also jeopardised message clarity and handed their rivals potential attack lines warning that supporting the Liberal Democrats could let in their opponent by mistake. With both leaders and parties not overwhelmingly popular in their own right, the Liberal Democrats began to project Swinson as a competent, decisive leader who owned policy positions like Revoke and was not afraid to make tough choices. When the Labour leadership bowed to pressure from Swinson and the SNP for an early general election, it was clear that the party would go ‘all in’ on this one-club electoral strategy.

3. The political and electoral strategy

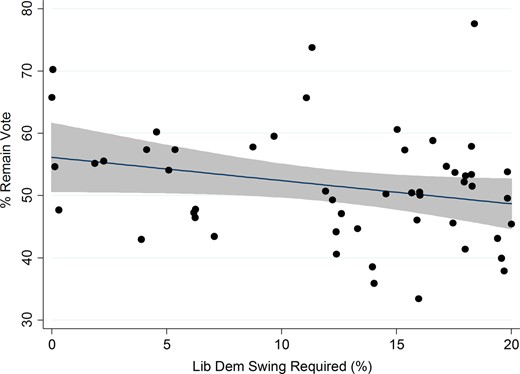

After their 2017 general election performance, the Liberal Democrats still needed to climb an electoral mountain even to get back to the point prior to entering coalition with the Conservatives. There were 17 seats where the party needed a swing of 10% or less, 12 of which were won by the Conservatives in 2017. On a swing of 20% or less, this figure increased to 52 seats with 40 held by the Conservatives, 7 by Labour and 5 by nationalist parties in Scotland and Wales. Of these 35 most marginal, only Dorset West and St Albans had not been held by the Liberal Democrats between 2001 and 2010. Despite evidence of growing individual switching, for any Liberal Democrat revival to occur, it was highly likely it would be in the places where local credibility remained a factor. But there were other problems to overcome. As Figure 6.1 shows, only 16 of the 52 seats where the Liberal Democrats required a swing of 20% or less had a Remain vote above 55%. Nine of these 16 seats were held by Labour or the SNP. Yet, 22 of these seats had a majority for Leave, with 12 recording a Leave vote of 55% or more. Ten of these 12 were held by the Conservatives. If the Liberal Democrats were to make an electoral breakthrough, they needed the support of both a highly efficient tactical ‘Remain Alliance’ and disgruntled moderate Leave voters. This was a monumental challenge.

Liberal Democrat 2019 possible constituency targets (swing 20% or less) by 2016 % Remain vote

To overcome the millstone of credibility, part of the electoral strategy involved trying to persuade switching MPs to remain in their incumbent seats and fight on the Liberal Democrat badge. Two of its new MPs (Sandbach and Wollaston) fought where they were originally elected. Other high-profile defectors were parachuted into Remain seats where party polling suggested they had a viable chance of winning or causing an upset. Three of these MPs (Berger, Gyimah and Ummuna) were strategically placed into strong London Remain seats, while Smith and Lee moved to Remain Altrincham and Sale West and Wokingham, respectively.

The party sought to offset credibility concerns by re-selecting either former MPs or those who stood in key target seats last time out. It hoped that the personal votes of former MPs would simultaneously nullify any incumbent advantage and act as a focal point for tactical pro-Remain switching in these seats. The Liberal Democrats also relied on their trusted local base to help spring a surprise. Recent local gains against the Conservatives in North Devon and Winchester provided some hope that this would translate to the parliamentary level. And the party agreed a Unite to Remain electoral pact with the Greens and Plaid Cymru in 60 seats where only one of these party’s candidates would stand to maximize the chances of getting MPs who opposed Brexit elected. With a free-run in 43 of these seats, the party hoped it would boost its electoral chances in key targets.

A key plank of the party’s electoral strategy was to minimize the potential squeezing from its rivals. Evidence from the British Election Study (Fieldhouse et al., 2019) suggested that the Liberal Democrats drew 49% of its vote from Labour and 20% from Conservative 2017 voters in the European elections. Holding onto these voters who switched was vital. Again, credibility was critical, given that in many potential seats the Liberal Democrats were third or a distant second. To offset this, the party deliberately avoided mentioning the 2017 constituency result and used more favourable local polling, evidence from Remain driven tactical voting sites and European election data. This led to some embarrassing enquiries about the creative use of data and dubious bar charts in some Liberal Democrat literature. The dual credibility goal was to ensure that the Liberal Democrats were regarded as the main Remain party and that they not Labour (in most cases) were best placed to stop the Conservatives winning a majority.

The biggest political and electoral gamble was the party’s Revoke policy. On the face of it, the strategy did have some merit. Senior party strategists were concerned about the fragility of the Liberal Democrat vote—a post-European election poll found that only 31% of Liberal Democrat voters would definitely continue to support the party at the general election whereas 29% may change their mind and vote for someone else. Without a distinctive platform, the fear was that they risked being swallowed up by one of its main rivals. With Labour now offering another referendum, the Revoke position meant the Liberal Democrats could continue to present itself as the true party of Remain. Given its weak partisan base and desire to build support in Labour seats, shoring up its vote through this Remain narrative seemed a credible option. Leaving aside the judgment on whether the party’s new policy was sufficiently liberal or democratic, it was a clear risk nevertheless. Only 54% of those who voted Liberal Democrat in June 2019 either approved or strongly approved of cancelling Brexit.1 While the policy appealed to voters in much of London and its wealthy suburban belt, outside of four or five London seats, it still needed to convert Labour and Green voters en masse to translate votes into seats. There was also a worry that a policy of revoking Article 50 could seriously backfire in Conservative battlegrounds. At the individual level, it was inconceivable that such a policy would appeal to Leavers while the Conservative Remain vote could also be turned off by such as hard-line policy. At the aggregate level, many of its previous strongholds in the South West of England were strong Leave areas. To win back these seats and others elsewhere, the Liberal Democrats were now reliant on the Remain vote mobilizing behind them and the Brexit party splitting the Leave vote. In Scotland, the Liberal Democrats had to ‘out-Remain’ the Remain SNP in a country where growing support for the SNP’s IndyRef2 platform was likely to split the Remain vote and lead to the party battling other parties for the Remain plus Union voter (see the Mitchell and Henderson contribution to this volume). Away from Brexit, it would still need to appease core Labour voters in any tactical coalition, given the Liberal Democrats austerity record. For all the talk of individual volatility, it still looked electorally complicated for the Liberal Democrats when the anchor of credibility was not present (Cutts and Russell, 2018).

4. The electoral outcome

The 2019 general election saw the Conservatives gain 43.6% of the UK vote and win an 80-seat majority with 48 net gains. Labour saw their vote plummet by almost 8 percentage points to 32.1% and 60 seat losses. While the combined Conservative and Labour vote share did not reach the heights of 2017, more than 75% of voters still supported the two main parties. With the SNP also gaining ground in Scotland, internal party fears that the Liberal Democrat vote could be squeezed during the election campaign became reality. Nonetheless, the party did poll nearly 3.7 million votes, 1.31 million more than in 2017 despite the 2-point decline in turnout and increased its vote share by 4.2 percentage points to 11.5% (Table 6.1). The improvement was steady but not the spectacular increase hoped for prior to the campaign. To put this into perspective, the Liberal Democrat vote was higher than in 2015 and 2017 but half of what it achieved nine years ago pre-coalition and lower than at any election between 1974 and 2010. Two years previously, the party lost support but achieved a net gain of four seats due to effective targeting. In 2019, support increased in 574 of the 611 constituencies where the Liberal Democrats stood candidates. Yet the party suffered a net loss of one seat, gaining three seats and losing four, and the number of Liberal Democrat MPs in Westminster fell to11.

| LD . | 1992 . | 1997 . | 2001 . | 2005 . | 2010 . | 2015 . | 2017 . | 2019 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes (000) | 5999 | 5243 | 4814 | 5985 | 6836 | 2416 | 2372 | 3696 |

| UK vote (%) | 17.8 | 16.8 | 18.3 | 22.0 | 23.0 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 11.5 |

| Seats won | 20 | 46 | 52 | 62 | 57 | 8 | 12 | 11 |

| Seats won (%) | 3.2 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Votes: seatsa | 1.12 | 2.74 | 2.84 | 2.82 | 2.48 | 1.01 | 1.62 | 0.96 |

| Lost deposits | 11/632 | 13/639 | 1/639 | 1/626 | 0/631 | 341/631 | 375/629 | 136/611 |

| LD . | 1992 . | 1997 . | 2001 . | 2005 . | 2010 . | 2015 . | 2017 . | 2019 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes (000) | 5999 | 5243 | 4814 | 5985 | 6836 | 2416 | 2372 | 3696 |

| UK vote (%) | 17.8 | 16.8 | 18.3 | 22.0 | 23.0 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 11.5 |

| Seats won | 20 | 46 | 52 | 62 | 57 | 8 | 12 | 11 |

| Seats won (%) | 3.2 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Votes: seatsa | 1.12 | 2.74 | 2.84 | 2.82 | 2.48 | 1.01 | 1.62 | 0.96 |

| Lost deposits | 11/632 | 13/639 | 1/639 | 1/626 | 0/631 | 341/631 | 375/629 | 136/611 |

Note: These are UK-wide vote share percentages so differ slightly from the GB-only figures reported by David Denver in ‘Results’.

Votes: Seats ratio derived from dividing LD seats won by LD share of the vote. In 1992, the Liberal Democrats stood in 632 constituencies; and in 2017, they stood in 629. In 2019, the party only stood in 611 seats following their pact with Plaid Cymru and the Greens.

| LD . | 1992 . | 1997 . | 2001 . | 2005 . | 2010 . | 2015 . | 2017 . | 2019 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes (000) | 5999 | 5243 | 4814 | 5985 | 6836 | 2416 | 2372 | 3696 |

| UK vote (%) | 17.8 | 16.8 | 18.3 | 22.0 | 23.0 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 11.5 |

| Seats won | 20 | 46 | 52 | 62 | 57 | 8 | 12 | 11 |

| Seats won (%) | 3.2 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Votes: seatsa | 1.12 | 2.74 | 2.84 | 2.82 | 2.48 | 1.01 | 1.62 | 0.96 |

| Lost deposits | 11/632 | 13/639 | 1/639 | 1/626 | 0/631 | 341/631 | 375/629 | 136/611 |

| LD . | 1992 . | 1997 . | 2001 . | 2005 . | 2010 . | 2015 . | 2017 . | 2019 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes (000) | 5999 | 5243 | 4814 | 5985 | 6836 | 2416 | 2372 | 3696 |

| UK vote (%) | 17.8 | 16.8 | 18.3 | 22.0 | 23.0 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 11.5 |

| Seats won | 20 | 46 | 52 | 62 | 57 | 8 | 12 | 11 |

| Seats won (%) | 3.2 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Votes: seatsa | 1.12 | 2.74 | 2.84 | 2.82 | 2.48 | 1.01 | 1.62 | 0.96 |

| Lost deposits | 11/632 | 13/639 | 1/639 | 1/626 | 0/631 | 341/631 | 375/629 | 136/611 |

Note: These are UK-wide vote share percentages so differ slightly from the GB-only figures reported by David Denver in ‘Results’.

Votes: Seats ratio derived from dividing LD seats won by LD share of the vote. In 1992, the Liberal Democrats stood in 632 constituencies; and in 2017, they stood in 629. In 2019, the party only stood in 611 seats following their pact with Plaid Cymru and the Greens.

Liberal Democrat performance, 2019 general election: national and regional breakdown

| National and Regional . | 2019 % LD Vote . | 2017 % LD Vote . | Change 2017–19 . | Seats 2019 . | Seats 2017 . | Change 2017–19 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | ||||||

| UK | 11.5 | 7.4 | +4.2 | 11/632 | 12/632 | −1 |

| England | 12.4 | 7.8 | +4.6 | 7/533 | 8/533 | −1 |

| Scotland | 9.5 | 6.8 | +2.8 | 4/59 | 4/59 | 0 |

| Wales | 6.0 | 4.5 | +1.5 | 0/40 | 0/40 | 0 |

| Region | ||||||

| East Midlands | 7.8 | 4.3 | +3.5 | 0/46 | 0/46 | 0 |

| Eastern | 13.4 | 7.9 | +5.5 | 1/58 | 1/58 | 0 |

| London | 14.9 | 8.8 | +6.1 | 3/73 | 3/73 | 0 |

| North East | 6.8 | 4.6 | +2.3 | 0/29 | 0/29 | 0 |

| North West | 7.9 | 5.4 | +2.5 | 1/75 | 1/75 | 0 |

| South East | 18.2 | 10.5 | +7.7 | 1/84 | 2/84 | −1 |

| South West | 18.2 | 14.9 | +3.2 | 1/55 | 1/55 | 0 |

| West Midlands | 7.9 | 4.4 | +3.5 | 0/59 | 0/59 | 0 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 8.1 | 5.0 | +3.1 | 0/54 | 0/54 | 0 |

| National and Regional . | 2019 % LD Vote . | 2017 % LD Vote . | Change 2017–19 . | Seats 2019 . | Seats 2017 . | Change 2017–19 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | ||||||

| UK | 11.5 | 7.4 | +4.2 | 11/632 | 12/632 | −1 |

| England | 12.4 | 7.8 | +4.6 | 7/533 | 8/533 | −1 |

| Scotland | 9.5 | 6.8 | +2.8 | 4/59 | 4/59 | 0 |

| Wales | 6.0 | 4.5 | +1.5 | 0/40 | 0/40 | 0 |

| Region | ||||||

| East Midlands | 7.8 | 4.3 | +3.5 | 0/46 | 0/46 | 0 |

| Eastern | 13.4 | 7.9 | +5.5 | 1/58 | 1/58 | 0 |

| London | 14.9 | 8.8 | +6.1 | 3/73 | 3/73 | 0 |

| North East | 6.8 | 4.6 | +2.3 | 0/29 | 0/29 | 0 |

| North West | 7.9 | 5.4 | +2.5 | 1/75 | 1/75 | 0 |

| South East | 18.2 | 10.5 | +7.7 | 1/84 | 2/84 | −1 |

| South West | 18.2 | 14.9 | +3.2 | 1/55 | 1/55 | 0 |

| West Midlands | 7.9 | 4.4 | +3.5 | 0/59 | 0/59 | 0 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 8.1 | 5.0 | +3.1 | 0/54 | 0/54 | 0 |

Liberal Democrat performance, 2019 general election: national and regional breakdown

| National and Regional . | 2019 % LD Vote . | 2017 % LD Vote . | Change 2017–19 . | Seats 2019 . | Seats 2017 . | Change 2017–19 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | ||||||

| UK | 11.5 | 7.4 | +4.2 | 11/632 | 12/632 | −1 |

| England | 12.4 | 7.8 | +4.6 | 7/533 | 8/533 | −1 |

| Scotland | 9.5 | 6.8 | +2.8 | 4/59 | 4/59 | 0 |

| Wales | 6.0 | 4.5 | +1.5 | 0/40 | 0/40 | 0 |

| Region | ||||||

| East Midlands | 7.8 | 4.3 | +3.5 | 0/46 | 0/46 | 0 |

| Eastern | 13.4 | 7.9 | +5.5 | 1/58 | 1/58 | 0 |

| London | 14.9 | 8.8 | +6.1 | 3/73 | 3/73 | 0 |

| North East | 6.8 | 4.6 | +2.3 | 0/29 | 0/29 | 0 |

| North West | 7.9 | 5.4 | +2.5 | 1/75 | 1/75 | 0 |

| South East | 18.2 | 10.5 | +7.7 | 1/84 | 2/84 | −1 |

| South West | 18.2 | 14.9 | +3.2 | 1/55 | 1/55 | 0 |

| West Midlands | 7.9 | 4.4 | +3.5 | 0/59 | 0/59 | 0 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 8.1 | 5.0 | +3.1 | 0/54 | 0/54 | 0 |

| National and Regional . | 2019 % LD Vote . | 2017 % LD Vote . | Change 2017–19 . | Seats 2019 . | Seats 2017 . | Change 2017–19 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | ||||||

| UK | 11.5 | 7.4 | +4.2 | 11/632 | 12/632 | −1 |

| England | 12.4 | 7.8 | +4.6 | 7/533 | 8/533 | −1 |

| Scotland | 9.5 | 6.8 | +2.8 | 4/59 | 4/59 | 0 |

| Wales | 6.0 | 4.5 | +1.5 | 0/40 | 0/40 | 0 |

| Region | ||||||

| East Midlands | 7.8 | 4.3 | +3.5 | 0/46 | 0/46 | 0 |

| Eastern | 13.4 | 7.9 | +5.5 | 1/58 | 1/58 | 0 |

| London | 14.9 | 8.8 | +6.1 | 3/73 | 3/73 | 0 |

| North East | 6.8 | 4.6 | +2.3 | 0/29 | 0/29 | 0 |

| North West | 7.9 | 5.4 | +2.5 | 1/75 | 1/75 | 0 |

| South East | 18.2 | 10.5 | +7.7 | 1/84 | 2/84 | −1 |

| South West | 18.2 | 14.9 | +3.2 | 1/55 | 1/55 | 0 |

| West Midlands | 7.9 | 4.4 | +3.5 | 0/59 | 0/59 | 0 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 8.1 | 5.0 | +3.1 | 0/54 | 0/54 | 0 |

For the second time in four years, Swinson experienced defeat in her East Dunbartonshire seat. In 2015, her vote held up relatively well when other Liberal Democrat incumbents suffered dramatic drops in support. This time, with her as party leader, the effect was hugely symbolic and catastrophic. The SNP was extremely effective at squeezing the Labour vote and building an anti-Swinson alliance to secure victory. The loss of Stephen Lloyd in Eastbourne was less surprising and less high profile, while defeat for Tom Brake in Carshalton and Wallington appeared to be a tactical blunder. Internal Liberal Democrat analysis suggested that Brake would hold the seat and central office then deployed valuable resources to nearby Wimbledon where the party was challenging the Conservatives. Warning signs emerged on polling day as efforts were made to save Brake but to no avail. Elsewhere, with Norman Lamb not standing in Norfolk North, the Liberal Democrat vote plunged by more than 18 percentage points as the Conservatives regained the seat.

The Liberal Democrats did gain North East Fife from the SNP helped by pro-Union Conservative tactical switching and narrowly held onto Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross and Edinburgh West. Across England, the two gains in ultra-Remain Richmond Park and St Albans were secured with comfortable majorities with both Liberal Democrat candidates polling more than 50% of the vote. In 6 of the 11 seats won, the party gained more than half of the votes cast. Elsewhere the party fell agonisingly short in four seats: Cheltenham, Sheffield Hallam, Wimbledon and Winchester. Wimbledon was one of seven seats (excluding Buckingham) where the party increased their vote by more than 20 percentage points but failed to win the seat. Despite some strong performances, all the Labour and Conservatives defectors who stood as Liberal Democrats in 2019 fell short. Perhaps the worst kept secret of the Liberal Democrat campaign was the big effort in Esher and Walton to unseat the incumbent, prominent Conservative Brexiteer Dominic Raab but despite increasing their vote by almost 28 points the party narrowly failed.

Two years ago, the Liberal Democrats polled more than 30% of the vote in 28 constituencies, lost 375 deposits and only came second in 38 seats. In 2019, the party did advance, winning more than 30% of the vote in 51 seats and losing deposits in only 138 constituencies. They are now second in 91 seats, 80 of which where the Conservatives are the incumbent. Of those second places, the Liberal Democrats are now 10% behind the winning party in 15 seats compared to 9 two years ago. Ten seats are ultra-marginal (5% or less behind the incumbent) with eight of these held by the Conservatives. Optimists might claim the Liberal Democrats have the platform to make serious electoral inroads into the Conservatives next time.

At the national and regional levels, the Liberal Democrat vote remains uneven and the post 2010 north-south divide in party support is widening (Table 6.2). Despite holding four seats in Scotland, its vote continued to be squeezed in the face of SNP resurgence and pro-Union supporters opting for the Conservatives unless the Liberal Democrats were better placed. Liberal Democrat support rose by less than 3 points in Scotland but it fared far worse in Wales. Even accounting for the Unite to Remain pact, the party lost Brecon and Radnorshire, 16 deposits in the 32 seats they stood and only managed to increase their vote by 1.5 percentage points across the country.

The Liberal Democrats gained support across all regions in England, with the largest growth in London and the South East. Of the 29 seats where the party is now fewer than 10 percentage points behind the incumbent, 14 are in London and the South East (and only eight of the party’s 138 lost deposits nationally were suffered in these areas). The Liberal Democrats continue to poll relatively strongly in its area of traditional strength, notably the South West with 11 of the 55 seats in the region recording Liberal Democrat vote shares of 30% or more. However, as in 2017, party support continues to bottom-out with increases below the national average. Aside from regaining Bath in 2017, they failed to recover lost ground elsewhere and the task seems to be getting more difficult. Only 5 of the 29 seats where the Liberal Democrats are 10% behind the incumbent now are in the South West with the Conservatives retaining huge majorities in previous Liberal Democrat strongholds.

Liberal Democrat support continues to hold up in eastern England and remains above the national average but elsewhere the picture looks bleak. Across the North of England and the Midlands, party support is anything from 3.4% to as much as 4.7% below the national vote share. In 2017, the difference between the five northern and midland regions and the four southern regions of England was roughly 6.5 points. By 2019, this gap had grown to 9 percentage points. To reiterate the growing divide, around 87% of lost party deposits in England were in the North and Midlands. Forty per cent of all UK wide lost party deposits were in the North West and Yorkshire and the Humber. The Liberal Democrats failed to record any constituency vote shares above 30% across the whole of the Midlands. Only 4 of the 29 seats where the party was second and less than 10% behind the winner in 2019 are in the North of England. There remains a clear geographic divide in Liberal Democrat representation. For the second successive election, Westmoreland and Lonsdale is the only northern English Liberal Democrat seat.

5. The constituency battleground

Table 6.3 examines the Liberal Democrats’ 2019 performance by seat type. In 2015 and 2017, while incumbency mattered, those seeking re-election were not guaranteed immunity from any national surge because of their personal standing in the seat (Cutts and Russell, 2017). The loss of Swinson and Brake reinforces this. Nonetheless, where a Liberal Democrat incumbent stood again, support rose by a modest 2 percentage points, lower than the national increase in party support and roughly half that achieved by incumbent candidates in 2017. For Liberal Democrat candidates in a number of incumbent seats, support had begun to reach its ceiling. Moreover, the party was far less defensive than two years ago targeting many more seats including some where the Liberal Democrats were languishing in third place. In non-held seats, support increased by more than 4 points. Evidence suggests that the floor of the Liberal Democrat vote (the 375 seats where the party lost its deposit in 2017) rose by 3.1 percentage points. Yet closer inspection suggests that, while being in second place mattered, the role of political agency continues to be more important.

Liberal Democrat performance by incumbency and seat type, 2019 general election

| Seats . | 2019 % LD Vote . | 2017 % LD Vote . | Change ±17–19 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incumbency | |||

| LD 2017 incumbent seats (12) | 44.6 | 44.2 | +0.4 |

| LD incumbent candidates (10) | 44.9 | 42.9 | +2.0 |

| LD non-held seats (599) | 10.9 | 6.6 | +4.3 |

| Seat type (LDs second place) | |||

| LD all second place (38) | 33.1 | 29.1 | +4.0 |

| Con-LD seats (29) | 35.4 | 29.7 | +5.7 |

| Lab-LD seats (7) | 24.5 | 26.1 | −1.6 |

| SNP/PC-LD seats (2) | 30.2 | 30.9 | −0.7 |

| Historical Legacy | |||

| LD legacy February 1974 seats (13)a | 19.9 | 21.9 | −2.0 |

| LD heartland 1992 seats (18) | 26.2 | 27.0 | −0.8 |

| LD breakthrough 1997 seats (28)a | 31.8 | 28.5 | +3.3 |

| LD pre-coalition 2010 (56)a | 27.6 | 27.6 | 0.0 |

| Seats . | 2019 % LD Vote . | 2017 % LD Vote . | Change ±17–19 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incumbency | |||

| LD 2017 incumbent seats (12) | 44.6 | 44.2 | +0.4 |

| LD incumbent candidates (10) | 44.9 | 42.9 | +2.0 |

| LD non-held seats (599) | 10.9 | 6.6 | +4.3 |

| Seat type (LDs second place) | |||

| LD all second place (38) | 33.1 | 29.1 | +4.0 |

| Con-LD seats (29) | 35.4 | 29.7 | +5.7 |

| Lab-LD seats (7) | 24.5 | 26.1 | −1.6 |

| SNP/PC-LD seats (2) | 30.2 | 30.9 | −0.7 |

| Historical Legacy | |||

| LD legacy February 1974 seats (13)a | 19.9 | 21.9 | −2.0 |

| LD heartland 1992 seats (18) | 26.2 | 27.0 | −0.8 |

| LD breakthrough 1997 seats (28)a | 31.8 | 28.5 | +3.3 |

| LD pre-coalition 2010 (56)a | 27.6 | 27.6 | 0.0 |

Notes: Percentages derived from summing LD votes cast/Total Valid Votes Cast × 100. The 2017 constituencies exclude Buckingham and Brighton Pavilion as the LDs did not stand a candidate in either constituency. In 2019, the Liberal Democrats stood in 611 seats.

Legacy seats are one less because the party did not stand in Isle of Wight; in 2010 they are one less because the party did not stand in Bristol West.

Liberal Democrat performance by incumbency and seat type, 2019 general election

| Seats . | 2019 % LD Vote . | 2017 % LD Vote . | Change ±17–19 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incumbency | |||

| LD 2017 incumbent seats (12) | 44.6 | 44.2 | +0.4 |

| LD incumbent candidates (10) | 44.9 | 42.9 | +2.0 |

| LD non-held seats (599) | 10.9 | 6.6 | +4.3 |

| Seat type (LDs second place) | |||

| LD all second place (38) | 33.1 | 29.1 | +4.0 |

| Con-LD seats (29) | 35.4 | 29.7 | +5.7 |

| Lab-LD seats (7) | 24.5 | 26.1 | −1.6 |

| SNP/PC-LD seats (2) | 30.2 | 30.9 | −0.7 |

| Historical Legacy | |||

| LD legacy February 1974 seats (13)a | 19.9 | 21.9 | −2.0 |

| LD heartland 1992 seats (18) | 26.2 | 27.0 | −0.8 |

| LD breakthrough 1997 seats (28)a | 31.8 | 28.5 | +3.3 |

| LD pre-coalition 2010 (56)a | 27.6 | 27.6 | 0.0 |

| Seats . | 2019 % LD Vote . | 2017 % LD Vote . | Change ±17–19 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incumbency | |||

| LD 2017 incumbent seats (12) | 44.6 | 44.2 | +0.4 |

| LD incumbent candidates (10) | 44.9 | 42.9 | +2.0 |

| LD non-held seats (599) | 10.9 | 6.6 | +4.3 |

| Seat type (LDs second place) | |||

| LD all second place (38) | 33.1 | 29.1 | +4.0 |

| Con-LD seats (29) | 35.4 | 29.7 | +5.7 |

| Lab-LD seats (7) | 24.5 | 26.1 | −1.6 |

| SNP/PC-LD seats (2) | 30.2 | 30.9 | −0.7 |

| Historical Legacy | |||

| LD legacy February 1974 seats (13)a | 19.9 | 21.9 | −2.0 |

| LD heartland 1992 seats (18) | 26.2 | 27.0 | −0.8 |

| LD breakthrough 1997 seats (28)a | 31.8 | 28.5 | +3.3 |

| LD pre-coalition 2010 (56)a | 27.6 | 27.6 | 0.0 |

Notes: Percentages derived from summing LD votes cast/Total Valid Votes Cast × 100. The 2017 constituencies exclude Buckingham and Brighton Pavilion as the LDs did not stand a candidate in either constituency. In 2019, the Liberal Democrats stood in 611 seats.

Legacy seats are one less because the party did not stand in Isle of Wight; in 2010 they are one less because the party did not stand in Bristol West.

Heading into the 2019 general election, the Liberal Democrats were second in 38 seats, 29 of which were Conservative–Liberal Democrat battlegrounds. Previously, the tactical unwind of the centre-left vote in these battleground seats was a major factor in the party’s collapse. Likewise in 2017, while success against the Conservatives transpired where the Liberal Democrats were able to curb the Labour vote, some tactical unwind occurred, with Labour even relegating the Liberal Democrats to third place in five seats (Cutts and Russell, 2017). In 2019, tactical unwind not only stopped but had reversed, although in modest and uneven fashion. In the 29 Conservative–Liberal Democrat battlegrounds, the party made above-average headway, increasing support by 5.7 points. There is, however, a lot of unevenness, with the party losing ground in five seats and simultaneously recording double-digit increases in another six. In the two seats, the Liberal Democrats won, both the Conservatives and Labour lost support. Across the 29 seats, the Conservatives marginally increased their support but Labour saw their vote drop by 6.6 points, with their vote declining in all but one of these constituencies. The Liberal Democrats clearly began to regain some of the centre-left tactical switchers that had left it after 2010 but its failure to make any deep inroads into the Conservative vote placed a ceiling on its ability to win seats.

In the seven seats, they were directly challenging Labour the party simply failed to breakthrough and lost 1.7 percentage points of their vote. Again, Liberal Democrat vote change was uneven with four of the seven seats recording a decline in support. Two recorded little change while the party’s vote rose by nearly 10 points in Hornsey and Wood Green. Labour also experienced a decline in support but only by 2.2 percentage points. Clearly, the failure to secure the marginal seats of Cambridge and Sheffield Hallam and to make further inroads against Labour generally was a considerable setback.

The tactic of re-selecting a previous Liberal Democrat MP to stand in the seat they once represented had limited success. Of those, only Sarah Olney in Richmond Park saw a substantial increase in support and actually won back the seat. In two potentially winnable seats—Ceredigion and St Ives—previous MPs lost ground. The Liberal Democrat retreat in their traditional heartlands continued although there are signs that the rate of decline is beginning to slow as support reaches its floor. Of the 14 Liberal constituencies held in February 1974, Orkney and Shetland remained the only seat held. The Liberal Democrats largely stood still in all 1,992 seats despite regaining North East Fife. Many of these seats were the foundation for party growth during 1990s and 2000s but were wiped out during the coalition years. In 2019, the drop in Liberal Democrat voting looks to have bottomed-out but there are few signs of any long-term recovery. On the contrary, for the second successive election, the Liberal Democrats improved their performance in the ‘breakthrough’ seats which the party won in 1997 at the peak of the anti-Conservative tactical alliance. They recorded on average more than 30% of the vote in these predominantly Conservative-leaning constituencies and increased their support overall by more than 3 points. Across the 56 seats that the party won in 2010 and stood a candidate in 2019, there was little evidence of any resurgence. This is mainly because any growth where the party was fighting the Conservatives was largely offset by more challenging conditions in seats where Labour and the SNP were the primary competitors. Despite the churn, 8 of the 11 seats won in 2019 were held by the party in 2010; 5 were first gained in 1997; 4 of the 11 seats also elected Liberal Democrat representatives 27 years ago. The story, therefore, remains similar to two years ago: while the party has failed to recover in its traditional heartland areas, the Liberal Democrats historical legacy still remains vital to both its support and Westminster representation.

6. Brexit and the Liberal Democrat vote

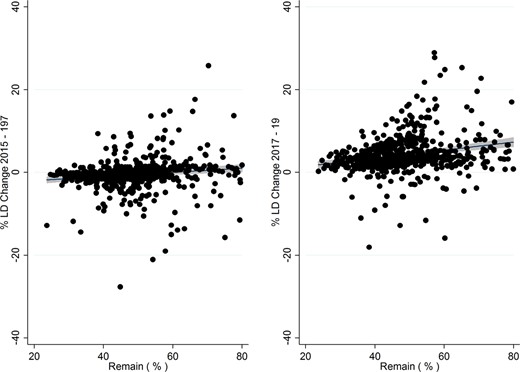

After the 2019 election, only 1 of the 11 seats represented by Liberal Democrat MPs voted Leave in the 2016 EU Referendum. In 6 of the other 10 seats it now holds, support for Remain in the referendum exceeded 60%. Three of the four losses were Leave seats. In 2017, there was a positive relationship (correlation of 0.15* significant at 99% level) between Liberal Democrat constituency vote change and Remain vote, albeit the line was relatively flat. Two years later, the relationship is slightly stronger (0.24* significant at 99% level) although there is some indication that the Liberal Democrat vote increased more in softer Remain seats as well as in those places that strongly voted Remain (see Figure 6.2).

Liberal Democrat vote change 2015–2017 and 2017–2019, by % Remain vote

Overall, party support was on average more than 6 percentage points higher in Remain areas than in Leave seats and around 4 percentage points higher than the party’s national vote share. When broken down into ‘soft’ (50–59.9%) and ‘hard’ (with a 60%+ vote) categorisations, it is evident that the party’s vote was 5.5 points lower in ‘hard Brexit’ than ‘soft Brexit’ areas but both saw increases in Liberal Democrat support (see Table 6.4). Many of these included seats where Labour was fighting off a Conservative surge. Even on this limited evidence (and acknowledging ecological fallacy issues), it is probable that while Remain voters did not abandon Labour for the Liberal Democrats in droves, the party’s ability to lift the floor of its vote harmed Labour. The party increased their vote share, on average, by 5.6% across Remain constituencies but the growth was nearly 1 percentage point stronger in ‘soft’ than ‘hard Remain’ seats. In a sizeable minority of these ‘hard Brexit’ seats, the SNP was rampant which restricted growth. Many others were safe Labour seats of which more than 30 were in London. The party simply lacked the longstanding credibility in these seats as a viable voting option so any possible surge in support was always going to have a ceiling.

Liberal Democrat performance in Remain and Leave seats, 2019 general election

| Seats . | 2019 % LD Vote . | Change ±17–19 . |

|---|---|---|

| Remain/Leave | ||

| All Leave seats (381) | 9.2 | +3.3 |

| All Remain seats (230) | 15.4 | +5.6 |

| Leave | ||

| ‘Soft Brexit’ seats 50.1–59.9% (231) | 11.0 | +3.8 |

| ‘Hard Brexit’ seats 60%+ (150) | 6.5 | +2.6 |

| Remain | ||

| ‘Soft Remain’ seats 50.1–59.9% (145) | 15.6 | +5.9 |

| ‘Hard Remain’ seats 60%+ (85) | 15.0 | +5.0 |

| Seats . | 2019 % LD Vote . | Change ±17–19 . |

|---|---|---|

| Remain/Leave | ||

| All Leave seats (381) | 9.2 | +3.3 |

| All Remain seats (230) | 15.4 | +5.6 |

| Leave | ||

| ‘Soft Brexit’ seats 50.1–59.9% (231) | 11.0 | +3.8 |

| ‘Hard Brexit’ seats 60%+ (150) | 6.5 | +2.6 |

| Remain | ||

| ‘Soft Remain’ seats 50.1–59.9% (145) | 15.6 | +5.9 |

| ‘Hard Remain’ seats 60%+ (85) | 15.0 | +5.0 |

Note: 611 seats where the Liberal Democrats stood candidates.

Liberal Democrat performance in Remain and Leave seats, 2019 general election

| Seats . | 2019 % LD Vote . | Change ±17–19 . |

|---|---|---|

| Remain/Leave | ||

| All Leave seats (381) | 9.2 | +3.3 |

| All Remain seats (230) | 15.4 | +5.6 |

| Leave | ||

| ‘Soft Brexit’ seats 50.1–59.9% (231) | 11.0 | +3.8 |

| ‘Hard Brexit’ seats 60%+ (150) | 6.5 | +2.6 |

| Remain | ||

| ‘Soft Remain’ seats 50.1–59.9% (145) | 15.6 | +5.9 |

| ‘Hard Remain’ seats 60%+ (85) | 15.0 | +5.0 |

| Seats . | 2019 % LD Vote . | Change ±17–19 . |

|---|---|---|

| Remain/Leave | ||

| All Leave seats (381) | 9.2 | +3.3 |

| All Remain seats (230) | 15.4 | +5.6 |

| Leave | ||

| ‘Soft Brexit’ seats 50.1–59.9% (231) | 11.0 | +3.8 |

| ‘Hard Brexit’ seats 60%+ (150) | 6.5 | +2.6 |

| Remain | ||

| ‘Soft Remain’ seats 50.1–59.9% (145) | 15.6 | +5.9 |

| ‘Hard Remain’ seats 60%+ (85) | 15.0 | +5.0 |

Note: 611 seats where the Liberal Democrats stood candidates.

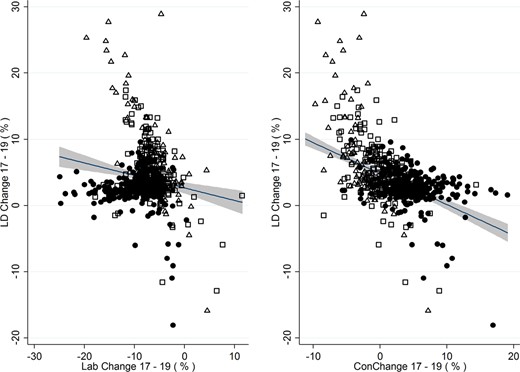

Figure 6.3 provides further insight into how Brexit shaped Liberal Democrat support in the 2019 election against their main rivals. Here, we mark England and Wales constituencies as to whether they backed Remain (hollow triangle, where support for Leave <45%); were comparatively evenly balanced (hollow square, where support for Leave ≥45% and ≤55%) or whether they backed Leave (black circle, where support for Leave >55%). For the Liberal Democrats, there is a significant negative effect for Conservative and Labour vote change on Liberal Democrat vote change, suggesting that Liberal Democrat support held up better in seats where their rivals did not make as much ground. In 2019, we can see how the Liberal Democrats made modest gains in Leave and largely working-class seats from an extremely low base predominantly where the Conservatives gained moderate support and Labour collapsed. In Remain and largely middle-class seats, there are places where the Liberal Democrats saw their vote surge while Labour fell away but there are also a number of strong Remain areas where the Labour vote held up. Liberal Democrat gains and Conservative losses are predominantly in the evenly balanced Brexit areas and Remain seats notwithstanding a small cluster of the latter where the party made little progress. While this did not translate into Liberal Democrat seats in 2019, it does illustrate Britain’s changing electoral map where previous Conservative middle class, largely Remain areas might be potentially vulnerable to the Liberal Democrats in future elections.

How Brexit shaped Liberal Democrat gains and losses, 2019 general election

7. Why did it go wrong for the Liberal Democrats?

7.1 Jo Swinson’s disastrous campaign

Leaders are critical nowadays in British elections but they are especially vital for third parties. Not only do they enable them to reach out to the electorate but they provide a vehicle to enhance electoral credibility and create goodwill towards the party brand. Traditionally, the Liberal Democrats always did better when they were given more exposure with the popularity of the leader a key determinant in the party’s success. With Johnson marmite for many and Corbyn unpalatable for more, the Liberal Democrats sensed an opportunity. Notwithstanding internal party enthusiasm for Swinson, many saw her relative obscurity both an advantage and a vehicle through which the Liberal Democrats could capture votes from disenchanted voters. As a consequence, the party’s campaign, branding and literature were built around her. From the orange battlebus emblazoned with her photo and the phrase ‘Jo Swinson’s Liberal Democrats’ to personalising high-profile policy announcements on free childcare for those aged two to four, the ‘presidential style’ campaign was all about selling Swinson the person to the public at large.

Far from being an electoral asset, Swinson quickly became a liability. At the party’s formal election campaign launch, Swinson insisted she was running to become Prime Minister. The comment haunted her throughout the campaign with many considering it arrogant and unrealistic. As the party’s polling began to slide, Swinson resolutely kept talking up her Prime Ministerial chances, which served to make her sound fanciful and out of touch. This was largely of the party’s own making but there was also a bind the Liberal Democrats now consistently find themselves in, since their time in coalition. The party ruled out working with a Johnson-led Conservative administration and a Labour one led by Corbyn but did not explicitly dismiss other alternatives. While this permitted some deflection on questions of potential coalition building, it meant that the party needed to persuade voters to support it in their own right and selling Swinson as a potential, credible Prime Minister was an important plank in this strategy. Crucially, Swinson’s approval ratings barely got above 25% throughout her period as leader. In the early days, many polled could not make a judgement but as the public got to know and see Swinson more, the more unimpressed they became. Whereas Swinson’s net approval rating was below Corbyn, ultimately, only 19% of the public approved of Swinson, a figure below even 21% for the Labour leader. Swinson simply failed to cut through.

Swinson’s inability to free herself from the shackles of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat 2010–2015 coalition also damaged the party’s appeal. Swinson’s own track record in the austerity government dogged her throughout the campaign. Not only she was the subject of a concerted online campaign from Labour supporters and activists, she faced anger from voters in person. During her BBC Question Time appearance, Swinson came under repeated attack from younger audience members for supporting austerity and was forced to say ‘sorry that we did not win more of those fights in coalition’ (Independent, 2019a). Swinson was also confronted by a student in Glasgow who blamed her and the Liberal Democrats for enabling austerity cuts and then later in the campaign by a protestor in Streatham over the effect of the coalition government's policies on young people. There was also a sense that the apology for austerity cuts became more sincere as the campaign progressed. Early on, Swinson not only spoke about being upfront about the Liberal Democrats failings in coalition but also defended their role in government pointing to policy successes such as same-sex marriage and taking lower incomes out of paying tax. A few weeks later the tone changed. The week before polling day, Swinson apologised for voting for austerity cuts, supporting policies such as the ‘bedroom tax’ and admitted that austerity went too far (Independent, 2019b). Austerity remained a millstone around the party’s neck. Among key voters that the party needed onside, austerity still mattered and Swinson represented the era when the Liberal Democrats were the poster boys of economic cuts. If the Liberal Democrats wanted to draw a line under this period, Swinson was emblematic of why this could not happen.

Swinson’s exclusion from the first televised head-to-head election debate was a damaging blow. It might have provided a critical space for the Liberal Democrat leader’s credibility, just as it did for Nick Clegg in 2010. A three-way leaders’ debate could have given the party and Swinson equal footing with her main rivals on a national stage. The vigour with which the party attacked and contested the decision suggested that they thought it might be a pivotal moment. Given the ‘presidential nature’ of the Liberal Democrat campaign, it represented a prize opportunity for Swinson to present herself as the moderate, progressive leader reaching out to discontented voters. Nevertheless, in different TV debate formats, it was not as if Swinson ‘stole the show’, so it is not guaranteed that Swinson and the Liberal Democrats would have gained a huge advantage from taking part.

7.2 Party strategy

Aside from adopting a backfiring ‘Presidential style’ campaign, the biggest strategic error was the policy to revoke Article 50. Throughout the campaign, it came under sustained attack from both the main parties. On the one hand, it was counterproductive because it could only be implemented if the party won a majority which was highly unlikely. It also muddied the Liberal Democrats’ Brexit message which was previously simple and clear. It both hurt and contradicted the moderate, pragmatic appeal of the party’s image to voters. Opponents questioned whether winning a majority at Westminster under first-past-the-post constituted an unequivocal mandate. For the Liberal Democrats, a party that had long supported proportional representation recognizing such a mandate seemed inconsistent and in the long run an act of self-harm. Polling two weeks before election day suggested that 28% of the public supported the Liberal Democrats’ position of revoking Article 50 and stopping Brexit completely (YouGov, 2019). Yet, only 50% of Remain voters backed it while 35% opposed. More than four-fifths of Leave voters unsurprisingly did not support the policy. The policy was clearly polarising and caused a great deal of public resentment. Moreover, there was barely any support among Conservative voters, with only 3% in agreement and 90% opposed. The policy of revoking Article 50 arguably placed a ceiling on party support and hampered efforts to persuade large numbers of Conservative moderates to lend them their vote. To make matters worse, in the final weeks of the campaign, the Liberal Democrats began to row back and returned to what Layla Moran called ‘Plan A’ of a second referendum. This shifted position reaffirmed that it ‘bombed’ with those voters the party wanted to win over.

Like previous efforts to be equidistant, such a stance simply failed to reap electoral rewards. While criticisms of Boris Johnson and his Brexit policy was wholly unsurprising, the acerbic tone levelled at Corbyn and Labour was strategically a little more difficult to fathom. Early on it appeared that the party saw an electoral opening. By winning over Labour Remain voters and moderates from other parties, the Liberal Democrats could do irreparable damage to Labour. Yet while Corbyn was clearly unpopular, it became abundantly evident as the campaign progressed that he was the only leading politician—and Labour the only party—that could achieve what the Liberal Democrats wanted—to stop Brexit. Despite this, the attacks continued diluting the party’s supposedly unequivocal anti-Brexit stance. This had two damaging knock-on effects. Firstly, many Labour Remainers simply saw through Liberal Democrat attempts to position themselves in key seats as the only viable Remain option. As Lord Ashcroft’s (2019) post-election polling shows, 84% of 2017 Labour Remainers stayed with Labour. Secondly, for Remain Conservatives, already nervous about a Corbyn-led Labour government, constant confirmation from the Liberal Democrats about how bad it would be scared them off from switching. When the opposition is unpopular, it makes it difficult for a third party to win seats from the incumbent. Further fuelling that unpopularity and supporting an extreme policy which could lead to resentment from voters in those key seats it is trying to attract, made little strategic sense and unsurprisingly failed. On the face of it, cooperation with Labour together with a carefully thought out political strategy to get a ‘people’s vote’ with Remain on the ballot through a Labour-led administration might have changed electoral dynamics. Simply put, equidistance gave the party a high-risk shot at a ‘home run’ return to the Kennedy days of Westminster representation, but ultimately it was somewhat easily and predictably ‘struck out’ by far cannier rivals.

7.3 The campaign

The party went into the election with a highly ambitious 80-seat target strategy as internal strategists believed that the electoral momentum was with them. It staked that volatility would triumph over local credibility with scores of voters abandoning place-based political loyalties as they switched to them. Yet, despite the odd surge and the leapfrogging of Labour in some seats, longstanding credibility once again proved far more vital. As the campaign went on, the target list was amended week by week based on internal polling and local canvass returns with layers of key seats withdrawn central support. Come polling day, only a select few target seats remained, illustrating how hopelessly optimistic the original strategy was. Some of the damage was done early on. Nigel Farage’s decision to remove the Brexit party from standing in Conservative-held seats was out of Liberal Democrat control but might have been anticipated as Farage had come under severe pressure from donors, high-profile supporters and the Brexit-leaning media in advance of the campaign. For the Liberal Democrats, already struggling to unify the Remain vote in marginal battlegrounds, a united Leave vote was far too powerful to overcome.

Other problems were of the Liberal Democrats’ own making. In an attempt to offset an absence of local credibility, the Liberal Democrats used European election constituency results, internal polling and external multilevel regression with post-stratification (MRP) polling from tactical voting websites and local constituency polls to tell voters it was them, not Labour, most likely to oust Conservative incumbents. The party’s use of data and badly drawn bar charts angered opposition activists and voters alike and quickly attracted media attention with Swinson having to face down accusations of misleading voters. It became an unwelcome distraction. And if Labour suspicions about the Liberal Democrats pro-Remain credentials at all costs were already somewhat waning, candidate disputes in Canterbury and High Peak added fuel to the anti-Labour conspiracy. While the decision to stand a candidate against pro-Remain Labour MP Rosie Duffield in marginal Canterbury did not stop her winning, her compatriot in High Peak was not so lucky, losing by 600 votes with the new Liberal Democrat candidate decisively winning more than 5% of the vote. Even though there was no formal Remain pact with Labour, it seemed to contradict the Liberal Democrats' widely aired stated ambition of stopping Brexit and opened it up to accusations that its real goal was to damage Labour.

Beyond revoking Article 50, the Liberal Democrats’ manifesto remixed and extended some 2017 policies such as 1p in the pound on income tax to raise £7 billion for NHS and free childcare for two to four year olds. Like 2017, there was a renewed attempt to win back centre-left voters who had deserted the party since 2010, with proposals to generate 80% of electricity from renewables, freeze train fares, recruit 20,000 new teachers, lift the minimum wage for those on zero-hour contracts and build 300,000 new homes a year. On the economy though, the Liberal Democrats were more fiscally conservative than their rivals, with stringent borrowing limits. Any additional revenue was due to come from the ‘Brexit bonus’ from remaining in the EU. Although the Liberal Democrats’ efforts to showcase their broader policy portfolio were somewhat overshadowed by ‘Brexit’, longstanding problems on political identity and policy appeal remained. Like 2017, aside from Europe where 11% of respondents named the Liberal Democrats as the best party, the Liberal Democrats were unable to make much headway in challenging their rivals’ ownership of salient issues (see Table 6.5). There were some improvements on Education but apart from Europe all other issues remained in single digits. Simply put, there were few signs that the policies presented in the manifesto translated to the public and little evidence that the party had managed to address longstanding concerns by showcasing a distinctive identity.

| Issue . | Conservatives . | Labour . | Lib Dems . | Others . | None . | DK . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 26 | 35 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 21 |

| Immigration | 30 | 18 | 8 | 14 | 7 | 24 |

| Law and order | 36 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 26 |

| Education | 26 | 30 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 24 |

| Taxation | 34 | 24 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 24 |

| Unemployment | 28 | 27 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 27 |

| Economy | 37 | 19 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 26 |

| Housing | 22 | 32 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 28 |

| Britain’s EU exit | 31 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 20 |

| Defence and security | 39 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 30 |

| Issue . | Conservatives . | Labour . | Lib Dems . | Others . | None . | DK . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 26 | 35 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 21 |

| Immigration | 30 | 18 | 8 | 14 | 7 | 24 |

| Law and order | 36 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 26 |

| Education | 26 | 30 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 24 |

| Taxation | 34 | 24 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 24 |

| Unemployment | 28 | 27 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 27 |

| Economy | 37 | 19 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 26 |

| Housing | 22 | 32 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 28 |

| Britain’s EU exit | 31 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 20 |

| Defence and security | 39 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 30 |

| Issue . | Conservatives . | Labour . | Lib Dems . | Others . | None . | DK . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 26 | 35 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 21 |

| Immigration | 30 | 18 | 8 | 14 | 7 | 24 |

| Law and order | 36 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 26 |

| Education | 26 | 30 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 24 |

| Taxation | 34 | 24 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 24 |

| Unemployment | 28 | 27 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 27 |

| Economy | 37 | 19 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 26 |

| Housing | 22 | 32 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 28 |

| Britain’s EU exit | 31 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 20 |

| Defence and security | 39 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 30 |

| Issue . | Conservatives . | Labour . | Lib Dems . | Others . | None . | DK . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 26 | 35 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 21 |

| Immigration | 30 | 18 | 8 | 14 | 7 | 24 |

| Law and order | 36 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 26 |

| Education | 26 | 30 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 24 |

| Taxation | 34 | 24 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 24 |

| Unemployment | 28 | 27 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 27 |

| Economy | 37 | 19 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 26 |

| Housing | 22 | 32 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 28 |

| Britain’s EU exit | 31 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 20 |

| Defence and security | 39 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 30 |

8. Conclusion

After being routed in 2015, the Liberal Democrats were on life support, battling for electoral survival. Two years ago, the party had stabilised but was still in a critical condition. In 2019, the Liberal Democrats seemed to be on the precipice of a full recovery but remain in intensive care. Most of the damage was self-inflicted. The campaign proved to be a disaster and much of the political strategy was ill-thought out. Embarking on a ‘Presidential style’ campaign with a leader whose popularity plummeted on close public inspection damaged the party’s ability to reach out to disenchanted voters (and suggests no-one in Liberal Democrat HQ had paid any attention to Theresa May’s disastrous campaign of 2017). Its seemingly kamikaze Revoke policy muddied the Liberal Democrat Brexit message, polarised the public and undermined the party’s moderate-pragmatic brand. The unrelenting personal attacks on Corbyn backfired, as Conservative and Labour voters hardened their positions for different reasons. Tactical mistakes, targeting blunders and data misrepresentation combined to make this a campaign to forget. Swinson’s own defeat in a seat the party was adamant throughout they would defend exemplified the campaign’s shortcomings. However, these failings actually mask some small but important advances. Leaving aside the drop in representation, the party saw an upsurge in support and is in a far healthier position than two years ago. Amidst Britain’s changing electoral geography, it is now in prime position against the Conservatives in a cluster of seats and has an opportunity to develop its local brand in many others. There are also strong signs of growth among longstanding demographics, particularly graduates living in suburban, cosmopolitan areas who in recent elections looked elsewhere. Despite the disappointment, there are reasons to be optimistic.

Yet longstanding issues persist. The party’s social and partisan base remains relatively weak and it is still largely reliant on votes that are lent rather than owned. Aside from Europe, the party continues to lack a political identity, focussing instead on quick fix, eye-catching proposals rather than building a long-term policy platform that appeals to those who share wider liberal values. Excluding its high-profile Remain credentials, it remains the case that, outside the most avid of political observers, most voters would be unable to say what the Liberal Democrats stand for, or recollect any of their policies. The association with the Coalition and its austerity policies also continues to damage the party’s brand with key sections of the electorate.

After three consecutive election setbacks, now ought to be the time to change direction and adopt a different approach. The Liberal Democrats need to rethink their political identity, probably embrace a more centre-left agenda and possibly abandon equidistance. Given the changing electoral map, it makes political sense to take a more strident anti-Conservative line and forge new alliances with those on centre left of British politics. With Corbyn gone and a new leader with reputational competence and ‘soft Left’ credentials at the helm, the task of persuading moderates in Conservative facing seats to switch should now be easier. But the party needs to be careful as they too could lose ground to Labour in the places where they have made progress if credibility is weak. And if Labour surges, winning back Labour-held seats may prove impossible. This will be doubly difficult if the party does not choose to break with the past. The logic here suggests the next Liberal Democrat leader ought to have been elected since the Coalition years so that they and the party can move forward without the baggage of austerity. While the Liberal Democrats are not awash with potential candidates, recent electoral churn means that there are a number of credible options. Rebuilding the connection with Labour and Green supporters could be the difference between making significant electoral gains or remaining a spectator on the sidelines.

The Liberal Democrats still face a monumental task. With Brexit seemingly done and dusted, political and economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to dominate the political discourse. With traditional left-right debates about the role, size and funding of the state likely to usurp recent cultural drivers of voting, the Liberal Democrats will face a renewed challenge of connecting with the public, providing policy distinctiveness and retaining political relevance. The 2019 election demonstrated that even when the Liberal Democrats recovered their relevance they still found it difficult to be popular. How the party defines and positions itself in the next few years could dictate its viability and long-term future. The Liberal Democrats might be on the road to recovery but the path ahead remains hazardous.

Footnotes

To the BES question of whether parliament should cancel Brexit, 54% of Liberal Democrat voters in June 2019 either approved or strongly approved. For Labour switchers, it was 57% but far less for Conservative switchers (46%).

References

Independent (

Independent (

YouGov (