-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Muhammad Meki, Simon Quinn, Microequity: some thoughts for an emerging research agenda, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Volume 40, Issue 1, Spring 2024, Pages 176–188, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grae001

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This paper summarizes recent research in performance-based microfinance, and outlines future directions for research. We use the term ‘microequity’ to refer to any small-enterprise financing contract in which the repayment owed in each instalment depends positively upon the variable performance of the enterprise. We summarize research from financial economics and development economics to highlight the importance of implicit insurance in microequity contracts, and present a theoretical framework to illustrate the potential of microequity in supporting capital investment and incentivizing asset use. We conclude by highlighting directions for future research in this emerging field of microfinance.

I. Introduction

In many parts of the world, small firms have access to financing contracts that specifically allow them to purchase large fixed assets—often with flexibility in repayment terms and asset ownership options. One of the most common forms of such flexible financing is equity, in which, typically, a lender provides a lump sum to a firm in return for owning a share of the firm (or, in some cases, a share of a specific firm project). This provides a stark contrast to most low-income settings—in which microenterprise owners typically only have access to inflexible debt-based cash loans (and often for amounts that are insufficient for large fixed-capital purchases).

In recent years, there has been extensive interest—from academic researchers, financial institutions, and policy-makers—in different forms of microfinance. This has involved very detailed debates on microcredit, as well as extensive discussion on microsaving and microinsurance. Conspicuous in its (near) absence, with a handful of notable exceptions, have been debates about microequity—notwithstanding the critical role that equity financing plays for small and large firms in middle- and high-income settings.

In this paper, we discuss some of the reasons for this discrepancy, and highlight some of the possibilities for expanding the use of microequity in future. We argue that equity-like products may—in the near future—provide a valuable complement to the portfolio of microfinance products; we say this based both on their flexibility (in particular, their implicit insurance aspects) and based on the increasing availability of high-quality transaction data for microenterprises in low-income settings.

When we speak in this paper of ‘microequity’, we refer to any small-enterprise financing contract in which the repayment owed in each instalment depends positively upon the variable performance of the enterprise. In this sense, we view ‘microequity’ as essentially being a synonym for ‘performance-contingent microfinance’—albeit with several key caveats that our definition implies. First, the lender’s exposure to the performance of the borrower’s enterprise should exist in the ordinary course of events—as a component of the repayments owed on a regular basis—rather than being limited to the risk of borrower default, or to the possibility of the borrower opting not to make a repayment. As Udry (1990) concisely put it, ‘Actual repayments of loans will generally depend on the random shocks received by the borrower, as long as defaults are possible. Here, owed repayments are at issue.’1 (In this sense, we view microequity contracts as distinct from literature on flexibility in microfinance—in which the exercise of an option to defer repayment might covary with the performance of a borrower’s business, but does not depend formally upon it.) Second, the owed repayments must depend positively upon enterprise performance—so we would not include as ‘microequity’ any kind of ‘performance-sensitive debt’ under which (for example) the lender is allowed to impose more adverse terms in response to poor borrower performance.2

This definition implies that—even in the normal course of events, aside from any consideration of default—a microequity lender faces both upside and downside risk in real terms.3 In particular, we argue that the term ‘microequity’ should not be limited to contracts in which a lender takes a formal ownership share in a business. As De Mel et al. (2019) emphasize, this implies that—in almost all cases—the financier’s exit will occur through the contract (for example, through the borrower successfully completing their repayments) rather than through a formal sale of shares (for example, through an initial public offering (IPO)).

We adopt this broad definition for two reasons: one principled, the other pragmatic. On a principled level, we will shortly argue—drawing on literature from financial economics and from development economics—that the conceptual essence of an equity contract is the shared claim upon business performance: the ‘mutuality’. Shared ownership of an entire business is one obvious way of achieving this—and, indeed, it is the most common sense of the term in many western legal and financial systems. However, there are many ways in which a borrower and lender might strike a formal sharing agreement other than through shared ownership of the business as a whole; we argue that ‘sharing agreements’, rather than ‘shared ownership of the firm’, lie at the conceptual foundation of academic literature on equity.

This is recognized directly in Islamic law—where musharakah sharing contracts allow joint ownership of a project or venture (rather than of an entire company). Many western legal systems allow broadly the same kind of equity agreement, through the use of ‘special purpose vehicles’ (and similar entities). Indeed, in a similar discussion, Zingales (2000) argues that the term ‘corporate finance’ became accepted for historical reasons, and that one could easily use alternative terms such as ‘enterprise finance’ or ‘firm finance’ (given that corporations as legal entities do not represent the only significant vehicle for economic activity, and particularly considering the changing nature of the firm in modern times). By analogous logic, we prefer that the term ‘microequity’ emphasize the formal sharing of risk—rather than being tied mechanically to the underlying legal form.

On a pragmatic level—as De Mel et al. (2019) note—microenterprises in low-income settings are generally (i) partially informal and (ii) owner-managed. For many microenterprises, it therefore may not even be legally possible (or meaningful) to have a part-ownership agreement for the enterprise as a whole. There is, in our view, a real risk in this space that the definitional ‘tail’ might wag the financial ‘dog’: that lenders and policy-makers might recoil from the very notion of microequity on the basis that it is impossible to share ownership of the microenterprise as a whole. We argue that, in order for the term to be useful, ‘microequity’ must describe a class of contracts that might plausibly be offered to microenterprises; the definition of the term must be sensitive to the realities of institutional settings in low-income contexts.

Our paper proceeds as follows. We begin—in section II—by summarizing key contributions from financial economics, to answer a fundamental question: Why not just use debt? That literature helps us to understand the advantages and disadvantages of equity-based financing relative to traditional debt; while primarily designed to think about larger firms in high-income settings, these models also provide useful general insights for thinking about microequity. In section III, we turn directly to some classic papers from development economics—many of which, in various ways, discuss themes of performance-contingent microfinance. We conclude that section by noting that most of this discussion has concerned informal lending practices—leaving unresolved some key questions about contract design for formal financial institutions. Section IV presents a simple theoretical model—based on a traditional sharecropping framework with multi-tasking—to illustrate the potential for microequity to support both capital investment (often in cases where a debt contract would be unattractive), and then to encourage asset use (through implicit insurance). We conclude in section V, with a discussion of related issues and next steps in this space.

II. Why not just use debt?

A long literature in financial economics has considered the relative merits of debt-based and equity-based financing. We begin by discussing some key contributions in this space—with a particular focus on issues that may be relevant for performance-contingent products in low-income settings. Specifically, we discuss corporate finance theories concerning the determinants of capital structure—meaning, in this context, the blend of debt and equity financing used by firms to support their investments.

Literature on capital structure can be broadly categorized into two strands: (i) one strand that takes the forms of financial instruments as exogenous, and explores how firms determine the optimal mix between debt and equity; and (ii) a second strand that endogenizes the forms of financial instruments by exploring the question of how specific financial instruments (like debt and equity) actually emerge, focusing on the theory of the firm and the allocation of cash flows and decision rights between entrepreneurs and investors. That second strand often works with models based on an extremely simple concept of a firm—with a single entrepreneur, a sole investor, and a single project (Hart, 2001). In our view, many of these conceptual insights—particularly from the second strand of literature—are highly relevant for thinking about the financial structure of small firms in low-income settings.

The starting point for considering capital structure is the classic work of Modigliani and Miller (1958). Modigliani and Miller show that, in a world with perfect capital markets—where investors can create well-diversified portfolios—the overall risk and return profile of an investor’s portfolio is determined by the underlying assets in which they invest, rather than the capital structure of individual firms. The famous ‘capital structure irrelevance’ proposition therefore argues that the choice between debt and equity financing has no material effect on the value of the firm. While the assumptions of frictionless capital markets and perfect information are clearly unrealistic, the model provides a useful benchmark from which subsequent theories deviate, to demonstrate how specific imperfections can make capital structure relevant. That subsequent theoretical and empirical literature has identified several key determinants of capital structure—with a particular emphasis on key reasons that firms should prefer debt financing over equity financing. Here we focus on what we believe are the two most important factors for small firms in low-income settings: (i) asymmetric information; and (ii) agency costs caused by conflicts of interest.

Managers—and other firm insiders—are generally assumed to hold private information about the characteristics of the firm’s assets and investment opportunities. Suppose that there are three sources of funding available to firms: retained earnings, debt, and equity. The seminal work of Myers and Majluf (1984) implies that, if external investors are less informed than firm insiders about the value of the firm’s assets, new equity issuances are likely to be under-priced by the market. The under-pricing may even be so severe that new investors capture more than the net present value of the new project—resulting in a net loss to existing shareholders. In such a case, the project will be rejected even if its net present value is positive. However, this under-investment can be avoided if the firm can finance the new project using a security that is not so severely undervalued by the market (such as retained earnings and internal funds—which have no adverse selection problem—or debt, which is less subject to adverse selection problems). This leads to the famous ‘pecking order’ theory of financing: capital structure will be driven by firms’ desire to finance new investments first with internal funds, then with debt; equity will be used only as a last resort. One of the most important implications of the pecking order theory is that, if the firm announces that it will issue equity, the market value of the firm will decrease—as investors update their belief about the unobservable ‘type’ of the firm.

There is extensive empirical evidence in high-income countries to support this prediction. The deeper point about signalling, and the information conveyed by the firm’s actions, is likely also relevant in low-income settings. Famously, in his work on ‘the market for lemons’, Akerlof (1970) recognized (for example) that an owner’s willingness to sell a used car conveyed information about the car’s quality. In a similar way, the willingness of firm managers to sell equity at a particular price conveys information about their view of what the equity is really worth. Knowing that selling equity will convey a negative signal concerning their views of the future prospects of their firm, an entrepreneur may, relative to a full-information setting, (i) retain more of the shares of the firm, (ii) be less diversified, and accordingly, (iii) may act in a more risk-averse manner (Stiglitz, 2002).

Agency costs, which stem from conflicts of interest among different groups with claims to the firm’s resources, provide an additional rationale for favouring debt-based financing. In the first strand of the capital structure literature—which assumes the existence of debt and equity contracts—traditional agency models identify two conflicts of interest (Fama and Miller, 1972; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). The first conflict involves shareholders and managers, and arises when managers hold less than 100 percent of the residual claim. Consequently, managers bear the entire cost of profit-enhancing activities, but without capturing the entire gain. (For example, managers can invest less effort in managing firm resources and potentially transfer firm resources to their own personal benefit.) As a result, managers may overindulge in these pursuits relative to the level that maximizes firm value. This inefficiency is reduced as the manager owns a larger fraction of the firm’s equity. Increasing the portion of the firm financed by debt increases the manager’s share of the equity—and, therefore, mitigates the loss from the conflict between the manager and shareholders. Moreover, as pointed out by Jensen (1986), debt commits the firm to pay out cash, reducing the availability of ‘free’ cash for managers to engage in such pursuits. This mitigation of conflicts between managers and equity-holders constitutes one major benefit of debt financing.

The second type of conflict arises between debt-holders and equity-holders. This conflict may occur because the debt contract provides equity-holders with an incentive to invest sub-optimally. Specifically, if an investment generates substantial returns, exceeding the face value of the debt, equity-holders reap most of the gain. However, in the event of investment failure and limited liability, debt-holders bear the consequences. Consequently, equity-holders may benefit from pursuing highly risky projects—even if those projects decrease the value of the firm. This phenomenon, known as the ‘asset substitution effect’, represents an agency cost associated with debt financing. Jensen and Meckling (1976) argue that an optimal capital structure can be achieved by balancing the agency cost of debt against the benefits it provides.

Agency problems are also addressed by the second strand of the capital structure literature, known as the ‘financial contracting’ literature, which examines optimal contract design and the emergence of debt and equity contracts. This literature primarily focuses on agency problems between managers and outside investors, as well as the allocation of cash flows. The underlying framework involves a manager who retains any income not distributed to outside investors (Harris and Raviv, 1993). However, the firm requires external financing for investments, leading to the need for an optimal contract that attracts willing outside investors. The seminal work of Townsend (1979) demonstrates that a debt contract serves as the optimal mechanism for addressing moral hazard problems arising from information asymmetry between borrowers and capital providers: the ‘costly state verification’ problem. Numerous studies delve into similar issues and consistently conclude that debt is the optimal financing contract in such environments.

Finally, we note the trade-off theory of capital structure (Robichek and Myers, 1966; Kraus and Litzenberger, 1973; Scott Jr, 1976). This theory posits that firms balance the tax advantages of debt (primarily interest rate deductibility) against its costs (notably the increased likelihood of financial distress). Such tax implications are less pertinent for informal firms in low-income settings (many of which do not register for business taxes). Nevertheless, the cost of debt—manifest in the heightened risk of business failure—is undeniably significant for all firms.

To this point, we have discussed various findings that suggest the optimality of debt contracts over equity contracts. However, these results pose a challenge when considering the empirical evidence that many firms indeed raise external equity finance. Several authors have attempted to address this ‘failure to develop a theory of outside equity’ (Dowd, 1992; Harris and Raviv, 1993). Webb (1992) extends Townsend’s static model to demonstrate the efficiency of state-contingent payments in a two-period model, where the second-period contract incentivizes honest reporting of first-period outcomes. Dowd (1992) highlights the tension addressed in many of the previously mentioned papers—namely, that the optimal contract places a significant amount of residual risk on potentially risk-averse entrepreneurs.

In sum, a body of literature in financial economics helps us to think about the relative advantages and disadvantages of performance-contingent financing for firm investments. This literature shows that the choice of financing must depend upon the firm’s individual circumstances—and this includes, critically, the firm’s exposure to risk. In a similar vein, Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) provide an analysis of sharecropping contracts, drawing parallels with the capital structure literature. They argue that performance-contingent contracts are inefficient because tenants equate their marginal disutility of effort with their share of the marginal product, rather than with their total marginal product, leading to insufficient effort exertion. However, their analysis also raises a crucial point, particularly relevant for low-income settings: that fixed-repayment contracts impose a heavy risk burden on agents who are risk averse.

III. Microequity as mutuality

This observation from Stiglitz and Weiss—that fixed-repayment contracts create a particular cost for agents who are risk averse—resonates with a long literature in development economics. In various ways, development economics has long studied situations where different economic actors share the risk from some venture. This includes borrowers and lenders.4

A key early contribution in this space is the work of Townsend (1994), using panel data from the ‘ICRISAT villages’ in India.5 Townsend finds that a model of full insurance provides a ‘surprisingly good benchmark’ for understanding the sensitivity of household consumption to idiosyncratic shocks (even though the null hypothesis of full insurance is formally rejected). Informal credit markets are one key mechanism by which such collective insurance might operate; as Townsend acknowledges, this might occur through flexibility ‘as regards the repayment of loans in bad years’, and through the ability more generally for ‘borrowing from village lenders or itinerant merchants’.

In seminal earlier work, Udry had—from February 1988 to February 1989—surveyed 198 farming households in northern Nigeria, with a particular emphasis on the relationship between adverse shocks and financial flows. Udry found persuasive evidence that the loans provided were performance-contingent by design: that owed repayments depended upon adverse shocks both to the borrower and to the lender. As explained in a companion follow-up paper (Udry, 1994):

The results show that when adverse shocks are received by sample households which are borrowers, they pay back less. This is consistent with conventional models of loan contracting, as the lower repayments may simply reflect a higher incidence of default on the part of sample households which receive adverse shocks. On the other hand, the estimates also indicate that when adverse shocks are received by sample households which are net lenders, they are paid back more. This finding cannot be understood in the context of conventional models of the credit market and provides striking evidence that repayments are state-contingent.

This result provides a fascinating real-world illustration of performance-contingent microfinance in a low-income setting. In doing so, it provides a useful reminder of the creativity and the flexibility of many local economic institutions. It is also important to understand several key features of the context of Udry‘s work. First, the loan agreements were ‘extreme in their informality’. Most loan agreements were made in private, with neither witnesses nor written agreement; most of the loans (84 per cent of the recorded transactions) did not agree explicitly an interest rate or a repayment date. Second, the context was unusual—as Udry explains, ‘significantly different from its counterparts in other areas of the world’—in the free flow of information between borrowers and lenders. Third, as subsequent work by Fafchamps and Lund (2003) emphasizes, ‘contingent repayment can only compensate for a small portion of actual shocks’—for many households, the receipt of credit (and of other gifts) may be more important for insuring against shocks than variation in repayment terms for existing contracts.6

It is one thing to recognize the value in principle of performance-contingent microfinance, and to observe its successful implementation among informal borrowers and lenders who know each other well; it is a distinct challenge to design a formal product that can be offered by a microfinance institution. As De Mel et al. (2019) describe, ‘in practice there are few concrete examples that show how such contracts could be structured, or demonstrations of how they would work in practice with microenterprises in developing-country settings’.

The key challenges in designing such products flow directly from the nuances recognized in the earlier literature just discussed. In our view, there are three primary challenges. First, the need for formality: for any formal microequity contract, there must be clear agreement on how owed repayments will be calculated—and this needs to be understood by the client prior to the point of agreement. Put bluntly, two friends can enter an informal loan agreement in which the terms of repayment are unspecified; a microfinance institution cannot. Second, the need for good proxy measures: owed repayments must depend upon one or more specific measures, and these measures need to provide a reasonable proxy for the underlying shocks facing a microenterprise. Third, the need for enforcement—whether through formal or informal means.

Several recent papers make some progress in thinking about what microequity contracts might look like in low-income settings. In a key early paper, Fischer (2013) ran a series of lab-in-the-field exercises with microfinance clients in India; this included an investment decision and an equity-like contract to finance it. Fischer found—in that laboratory context—that ‘The equity-like contract increased risk-taking and expected returns relative to other contracts, while at the same time producing the lowest default rates’; he concluded that ‘Innovative financial contracts may encourage substantial increases in the expected returns of microfinance-funded projects.’ Meki (2023) extends this to study preferences for equity-like financing among microfinance clients in Kenya and Pakistan—and shows additional benefits of equity for loss-averse individuals. This makes strong intuitive sense: loss aversion generates particular costs from downside risk, so loss-averse individuals stand particularly to gain from the implicit insurance aspect of microequity.

De Mel et al. (2019) ran a pilot study in Sri Lanka of a ‘self-liquidating, revenue-based, royalty contract’. (The authors chose a revenue-based contract rather than a profit-based contract in order to avoid encouraging cost distortions.) Collaborating with nine microenterprises, the study involved an average investment of $3,800 per firm, structured to be repaid over 36 months (with a 3-month grace period). Repayment outcomes varied substantially: two firms made all of their payments on time (yielding positive returns); one experienced minor delays in completion; four firms fell into arrears after 8 months; and two fell into arrears immediately. Together, the portfolio lost 52 per cent of the initial investment—which was then later reduced to 40 per cent following arbitration and commencing litigation.

More recently, Cordaro et al. (2023) ran a field experiment in Kenya within the supply chain for chewing gum of a multinational food manufacturer (which the authors pseudonymously term ‘FoodCo’). Traditionally, many of FoodCo’s distributors travel on foot; Cordaro et al. partnered with a local microfinance institution to test alternative financing models to provide distributors with bicycles. The experiment involved a control group (who did not receive financing), and a group offered a traditional debt contract. However, the authors went further: working with FoodCo to use high-frequency administrative data on stock purchases. These data enabled the authors to offer two alternative contracts: a revenue-sharing contract (in which clients owed a fixed sum plus a share of the revenue earned through FoodCo), and a hybrid contract (in which regular repayments are calculated in the same way as in the revenue-sharing contract, until total repayments reach the same total repayments owed under the debt contract).7

Cordaro et al. find that the hybrid contract is the most successful—and that it outperforms the traditional debt contract in several ways. First, this contract encourages clients to work harder in their business efforts, and to take additional risks in their business operations. In turn, this leads to large positive impacts on distributors’ profits: in intent-to-treat terms, an increase of about 170 per cent in monthly business profits for individuals assigned to the hybrid contract compared to the control group. This generates measurable downstream household gains—including increased household expenditure on food and clothing. The authors conclude that their experimental results illustrate that ‘incorporating performance-contingent features into standard microfinance contracts can encourage investment and increase profits more than under a standard rigid debt contract’.

IV. A stylized framework

In principle, there are many ways in which a microequity contract might be structured. For example, owed repayments may be an increasing function of some agreed measure of a borrower’s revenues—possibly with owed repayments capped at some pre-agreed ceiling on total repayments. Alternatively, repayments might depend upon a precise measure of microenterprise inputs (on the understanding—as in Cordaro et al. (2023)—that this will be a reasonable proxy for value-added). De Mel et al. (2019) emphasize that this case will require microenterprises with ‘very simple production functions’. To illustrate, the authors explain how one Egyptian lender provided finance for an egg producer, ‘calculating payments on the basis of the number of chickens the producer had, along with an estimate of eggs produced per chicken on average, and prevailing egg prices’. Further, repayments might also depend—in part, at least—upon some other proxies for shocks to the borrower’s enterprise (for example, an index of local weather conditions, or some index of the revenue earned by other microenterprises in a market).8 As Holmström (1979) explained,

In the same way managers are not held responsible for events one can observe are outside their control, and implicitly at least, their performance is always judged against information about what should be achievable given, say, the current economic situation.

To fix ideas, we now present a simple model. This model is designed to illustrate how one class of microequity contracts can be structured, and to illustrate some of the key tensions determining both take-up and effort. The model is inspired by Holmström (1979) and a sharecropping framework.9 Specifically, this model is a simplified version of the set-up in an earlier version of Cordaro et al. (2023).

We imagine a microfinance client, with a profitable potential capital investment. We assume initially that she will finance this investment with a loan from a microfinance institution (MFI). After investing, the client must choose effort, e. Initially, we consider a single margin of effort—which will increase repayments to the lender. (So, in Cordaro et al. (2023), the client chooses the number of bags of chewing gum to purchase—which will increase profits but will also increase repayments for the bicycle. In the example given by De Mel et al. (2019), the client could invest in buying more chickens—where her ownership of chickens will be taken as a proxy for her profitability, and thus increase her payments to the lender.) We assume a static framework in which the client owes a fixed repayment of F, plus some proportion 1−ω of income.

We allow income to depend multiplicatively on both effort and on a productivity shock; that is, we assume π(e, η; κ) = κ · η · e. We normalize κ = 1 for the case where the potential investment is not made (so that κ > 1 captures the returns to capital investment). This simple production function formalizes the notion that, as clients exert more effort (increased e), they also expose themselves to more risk; the same is true as clients invest in capital (increased κ).

Finally, we allow the entrepreneur to be risk averse (with her risk aversion captured by parameter r > 0). Allowing for quadratic effort costs in both on-contract and non-contract effort, we can then therefore write the value of the microequity contract—to the client—as follows:

To solve the client’s problem, we use a standard CARA utility function (that is, u(x) ≡ − exp(−rx)), and assume that the productivity shock η is Normal:10η ∼ (1, σ2). This generates straightforward expressions for the client’s certainty equivalent, her optimal effort, and the value of the contract.11

This framework allows us to model several key contractual forms:

No-contract case: For a client refusing to take a loan (and, therefore, not investing in the product), ω = 1, F = 0 and κ = 1.

Debt: Under the debt contract, clients retain all of their profits (ω = 1), owe a fixed repayment (F = Fd), and enjoy higher productivity: κ > 1.

Equity: Under the equity contract, clients retain a share ω of their on-contract profits, may owe some fixed repayment (Fe ∈ [0, Fd)), and enjoy higher productivity: κ > 1.

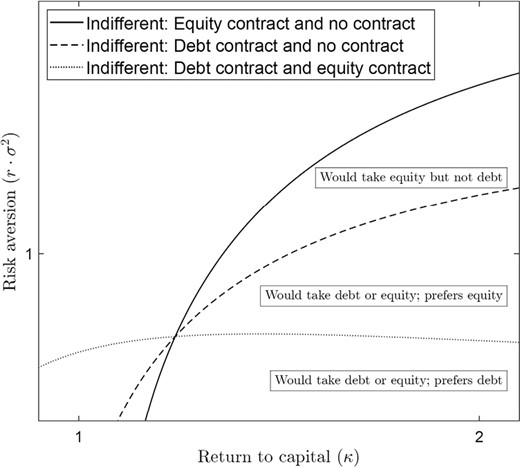

Figure 1 shows the predictions of the model on take-up—where we allow here for heterogeneity in the return to capital (represented here in the form of κ, on the horizontal axis) and in risk aversion (here captured jointly by the coefficient of absolute risk aversion and the riskiness of the productivity shock: r·σ2). To illustrate, we use throughout the values ω = 0.9, Fd = 0.1, and Fe = 0.05. The solid black line shows the client’s indifference curve between taking the equity contract and taking no contract; below this line, the client strictly prefers to take the equity contract. The dashed line shows indifference between taking the debt contact and taking no contract (below the line, the client strictly prefers to take debt), and the dotted line shows indifference between taking the debt contract and the equity contract (below the line, the client strictly prefers the debt contract).12

The figure illustrates three key points. First, the debt contract is preferable for clients who are relatively less risk averse, whereas the equity contract is valued by those who are more risk averse (because of its bundled insurance feature). Second, there is a region of the space in which clients who are highly risk averse will take an equity contract but not a debt contract. This reflects the notion of ‘risk rationing’ (Carter et al., 2007)—that, when capital investment brings additional risks, an absence of bundled insurance implies that profitable investments do not go ahead. Third—because κ has a multiplicative effect on risk—the effect of increasing κ is not straightforward. One might intuitively expect that there is a strong adverse selection in κ—so that enterprises with a higher return to the capital investment would be much more likely to prefer debt (rather than to share their proceeds through equity). In this stylized model, this is not necessarily the case; because κ increases investment risk, the implicit insurance provided by the equity contract can offset the adverse selection that one might otherwise intuitively expect.

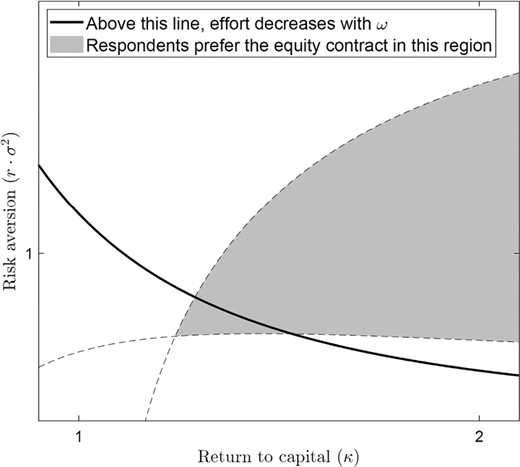

To understand this point further, it is useful to explore the impact of the sharing ratio (ω) on the entrepreneur’s effort (e*). In Figure 2, we take the same model predictions as Figure 1 (shading the area in which, in Figure 1, we showed that respondents would prefer the equity contract); to this, we add a line showing the set of points where effort is invariant with respect to the sharing ratio. Above this line, effort decreases as ω increases—that is, entrepreneurs make less effort as the equity contract allows them to keep more of their revenue.13 (The opposite is true below this line.) In most of the shaded area in the figure, effort decreases as ω increases. This is quite a different prediction to most theoretical formulations of sharing contracts—in which revenue-sharing reduces effort by ‘taxing’ the client’s returns (as Angrist et al. (2021) explain, output sharing ‘inserts a wedge between effort and income’). This result follows from the assumption that risk increases with effort—so the implicit-insurance feature of equity contracts enters directly the client’s first-order condition. As we noted earlier, this feature—that increasing the use of an asset also exposes the entrepreneur to additional risk—is common to many settings, including many settings that are relevant for microfinance.

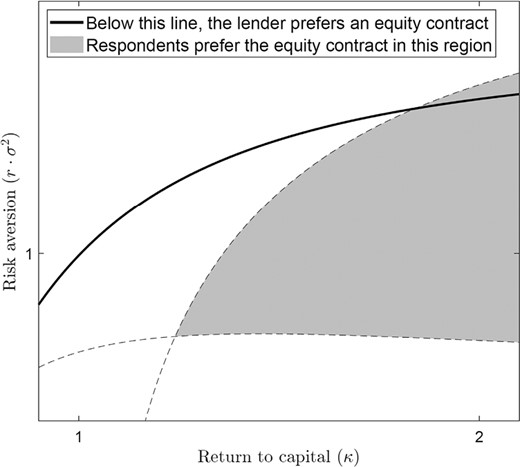

Finally, we consider the preferences of the lender. We do this in a very stylized way: under a debt contract, the lender recovers Fd; under an equity contract, the lender recovers (in expectation) Fe +(1 − ω) · κ. Figure 3 shows the set of points for which Fd = Fe + (1 − ω) · κ; below this line, a risk-neutral lender would prefer to offer the equity contract (in order to share the gains from the capital investment). The figure also shows a shaded region: here, the client prefers the equity contract over both taking the debt contract and taking no contract. The graph illustrates that, for almost all of the region in which the client prefers to accept the equity contract, the lender prefers to offer it. This emphasizes—again—the critical role of risk for this model: the client is willing to trade substantial profits to reduce uncertainty, so both parties prefer the implicit-insurance (equity) contract to the fixed-repayment debt contract.

This model is extremely stylized—and we view the framework as a useful guide for capturing intuition and for illustrating possibilities, rather than for making specific empirical predictions. In particular, we caution against a literal interpretation of the magnitude of the risk aversion (not least because of the very stylized way in which η enters the production function). In our view, there are at least two plausible model extensions that hold useful relevance for real-world settings.

First, one could imagine a client choosing effort on two separate margins—one of which will increase her repayments to the lender; the other of which will not. (So, in Cordaro et al. (2023), the client could sell chewing gum for the multinational corporation ‘FoodCo’—where such sales will increase the amount owed under the financing contract—or could spend time on other productive activities. In the example given by De Mel et al. (2019), the client could invest in buying more chickens—where her ownership of chickens will be taken as a proxy for her profitability, and thus increase her payments to the lender—or could buy other livestock.) This multi-tasking framework is clearly relevant to our conceptualization of microequity: if a lender is not taking an ownership share in the microenterprise as a whole, the lender must accept that the client can substitute away from whichever activity is used as a proxy for sales.14 We describe the former category as requiring ‘on-contract’ effort (which we denote as ec), and the latter category as requiring ‘non-contract’ effort (en). In this setting, the degree of substitutability between ec and en is clearly fundamentally important. In one limiting case, the two activities are completely separate from each other—for example, perhaps the non-contract effort generates its own separate retained earnings κen, at a cost of . This case is essentially isomorphic to the case already discussed above; the optimal choice of en does not depend upon ω. In another limiting case, the two activities are perfectly substitutable (so retained earnings after sharing become κ · η · (ω · ec + en) and total cost is (ec + en)2. In this case, trivially, a risk-neutral entrepreneur immediately shifts all effort away from the ‘taxed’ activity (that is, for r ≈ 0, ω < 1 implies = 0). This seems unrealistic for real-world settings, but is worth bearing in mind—if, for example, ‘FoodCo’ had a very close competitor in the labour market for micro-distributors, the results of Cordaro et al. (2023) might be very different.

Second, there is clearly scope here for variations in the contractual design. One approach is suggested immediately by Figure 3: if the lender can observe rσ2 and κ, there is scope for the lender to increase profits by adjusting Fe and ω. A more creative approach—and one that goes beyond the static set-up considered here—is to consider a dynamic contract in which the repayments depend upon past as well as current performance. This is the nature of the ‘hybrid’ contract in Cordaro et al. (2023)—where monthly repayments are calculated in the same way as the equity contract, until total repayments match the amount that would be owed under the debt contract. Cordaro et al. (2023) show how this kind of risk-sharing theoretical framework can be extended to consider that kind of dynamic contract, using a Bellman equation (where the state variable is the outstanding debt).

V. Conclusions and future directions

In this paper, we have argued that microequity is a promising area for further development in the microfinance space. We have reviewed the traditional arguments for and against equity financing, and situated such financing more generally in the development economics literature on mutuality. We have used a stylized multi-tasking model to illustrate how microequity contracts might be both attractive (in the sense of being preferable to traditional debt-based financing for at least some clients) and useful (encouraging effort through implicit insurance).

In this concluding section, we speculate on some directions for the future development of this kind of performance-contingent microfinancing. We highlight three issues: (i) the scope for using microequity to expand financing to the unbanked Muslim poor, (ii) the special organizational challenges that microequity might pose for loan officers in large microfinance institutions, and (iii) the particular relevance for microequity of the expansion of digital transactions.

(i) Microequity and the Muslim poor

We earlier discussed the work of Udry (1990), who surveyed 198 households in northern Nigeria. Of these, 197 households were Muslim—and all of whom, when asked to explain the absence of fixed interest rates in their informal financial contracts, referred to Sharia law. This, of course, is no coincidence; many Muslims view traditional interest-based financing as being contrary to the principles of their faith.15 Nearly a billion of the world’s poor live in Muslim-majority countries, with high reported levels of financial exclusion (World Bank, 2013). Islamic finance specifically encourages risk-sharing instruments (Iqbal and Mirakhor, 2013; Sheng and Singh, 2013); an equity-based product, though not restricted to any one particular religion or group, is likely to have particular appeal to Muslim entrepreneurs who often reject conventional financial products due to the classic ban on usury (Karim et al., 2008; Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2014; El-Gamal et al., 2014; Bari et al., 2021; Karlan et al., 2021).

Further, several large Muslim-majority countries—in particular, including Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Indonesia—face a disproportionate exposure to climate risks, and a need for innovative risk-sharing products. A recent report by the Asian Development Bank (2022) advocates for the development of Islamic finance products that address climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience. This includes the use of blended finance, which utilizes concessional capital to crowd-in private-sector funding in the form of equity or commercial loans.

(ii) Loan officers and internal incentives

The successful implementation of novel microfinance models requires more than intricate theories and sophisticated product design; it hinges on a deep understanding of the critical role played by microfinance loan officers in the financial intermediation process. Loan officers are a key component in what remains a labour-intensive sector (Malik et al., 2020; Czura et al., 2022). It is thus critical to think about the mechanics of how loan officers select clients, disburse loans, and how they are incentivized, and the implications of new business models on these existing structures.

Meki (2018) reports on an attempt by a large MFI in Pakistan to implement microequity contracts with a common sharing ratio for all microenterprises. Monitoring client performance required significant effort from loan officers. Some of the most profitable clients initially made large profit-sharing payments, which concerned them about the total amount they would have to share. Subsequently, the programme unravelled as clients and loan officers mutually agreed to revert back to the simpler fixed-repayment model with which they were familiar (rather than just reverting all the most profitable clients to debt contracts and keeping the least profitable under profit-sharing contracts).

This highlights the need for careful design of the sharing mechanism, with particular attention to the extent of upside sharing. Other more general evidence of the challenge of organization change and incentives within MFIs is provided by Rigol and Roth (2021), who demonstrate that loan officers impede borrower graduation due to their compensation structure. In a middle-income setting, Hertzberg et al. (2010) provide evidence that loan officers may hide information about borrower quality that may reflect poorly on their own performance and affect their career prospects.

(iii) The future (of microequity) is digital

Several papers in this issue of the Oxford Review of Economic Policy have discussed the ‘digital transformation’ taking place in low- and middle-income countries—emphasizing the potential for reducing information asymmetries, improving financial inclusion, and stimulating financial innovations (Barboni, 2024; Burlando et al., 2024; Mazer and Garz, 2024). In particular, Annan et al. (2024) report a significant increase in the share of people engaging in digital transactions over the last 7 years, rising from 12 per cent to 35 per cent. Of particular interest for this present article are the advancements in digital payment systems, such as the growing use of point-of-sale (POS) machines and quick response (QR) codes. These technologies—often implementable without formal bank accounts by linking to mobile money networks (Higgins, 2022; Suri et al., 2023)—have expanded firms’ ‘digital footprints’. The Cordaro et al. (2023) field experiment—conducted within the supply chain of a multinational that pays its distributors via mobile money—also illustrates the possibility for finance contract payments to be deducted directly at source. Payment fintechs that observe firms’ revenue and can use past performance for better screening can also directly deduct loan payments—offering a unique opportunity for experimenting with microequity. Indeed, several firms in high-income countries, such as PayPal and Square in the US and Zettle in Europe, have begun offering revenue-based financing (Rishabh and Schäublin, 2021). Despite the remaining challenges of ‘side-selling’ and sales diversion (Russel et al., 2023), data triangulation methods and ‘forensic measurements’ like mystery shoppers (Annan et al., 2024) could reduce lender risks. These digital developments offer promising avenues for experimenting with microequity contracts better tailored to the specific investment needs of small businesses in low-income countries.

We thank Paddy Carter, Vatsal Khandelwal, Tim Ogden, and Isabel Ruiz for very useful comments, as well as participants at the 2024 Biennial Conference of the Economic Society of South Africa.

References

—

—

—

— (

— (

Footnotes

Emphasis in original.

See Manso et al. (2010) for a theoretical discussion of this class of contract. This occurs under some corporate financing contracts (for example, bonds whose interest rate increases as the borrower’s credit rating deteriorates) and under many household financing contracts (for example, overdraft fees increasing when a borrower exceeds some pre-specified overdraft limit).

For the avoidance of doubt, it may be worth adding a further clarification—that we are speaking here about financing contracts designed so that the lender has some reasonable expectation of recovering their capital outlay; when we speak in this paper about ‘microequity’, we are not speaking simply about grants. In earlier work, Pretes (2002) used the term ‘microequity’ to refer to ‘the provision of grants by external agencies to potential entrepreneurs in developing countries, without any expectation of a share in the ownership or profits of the business’. We agree that such grants can be very valuable for microenterprises, but we do not include them in our definition of ‘microequity’.

Indeed, all credit is—to some extent, at least—performance-contingent. No loan can truly be risk free for the lender: there is always some plausible scenario in which, owing to some unanticipated shock, a borrower does not repay in full. This may be permitted under the terms of a loan agreement (in the sense of a force majeure event). Alternatively, it may amount to a breach of contract—with a borrower delaying repayments, or even defaulting on the loan completely. In an intermediate case, a loan officer may agree to renegotiate a contract with a borrower who is facing financial difficulties—including, perhaps, offering a new loan to revive a loan that is approaching default (sometimes known as ‘evergreening’).

Specifically, Townsend uses data from the villages of Aurepalle (in Andhra Pradesh), Kanzara, and Shirapur (both in Maharashtra). The Indian ICRISAT villages have formed the basis for a very large number of empirical studies in development economics; see Bold and Broer (2021) for a summary of some of these contributions.

Dercon et al. (2006)’s work on Ethiopian funeral societies—iddir—provides another example of an indigenous institution providing performance-contingent financing, albeit with a different focus. Dercon et al. explain that iddir groups take payments from a defined membership group in order to defray funeral expenses—and that approximately two-thirds of the groups in the sample would also offer loans. These loans would be offered in the form of short-term credit to help deal with adverse shocks.

The authors also offered an index insurance contract, which we do not discuss in this summary.

This is closely analogous to what is known in agricultural settings as ‘area-based yield insurance’: see Carter et al. (2007).

The analogy between performance-contingent microfinance and sharecropping dates at least to Udry (1990): ‘The simplest form of this loan contract, in which repayments depend upon the outcome of a particular project, is analogous to sharecropping in the land market.’

Taken literally, the assumption that the productivity shock is Normal implies that output may be negative (in the sense that η is unbounded, with output depending multiplicatively upon η). This may or may not be realistic, given the context, and could readily be corrected by taking some other assumption on the shock distribution (for example, the Log-Normal may be more realistic—albeit less elegant for the model solution).

The certainty equivalent is given by. This implies the following choice of effort: The certainty equivalent under optimal effort choice is, therefore:

The curves in Figure 1 are obtained by equating the certainty equivalents for different contracts, using the equation in footnote 11.

The line shows the set of points for which rσ2 = (ωκ)−2; for these points, de*/dω = 0.

In this sense, the model has some similarity to the multi-tasking principal–agent models of Holmström and Milgrom (1991) and of Feltham and Xie (1994).

It is worth noting that Udry (1990) also notes that, in his sample, ‘individuals display no reluctance to accept loans from banks at low (but positive) fixed nominal interest rates’.