-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ana María Ibáñez, Andrés Moya, Andrea Velásquez, Promoting recovery and resilience for internally displaced persons: lessons from Colombia, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Volume 38, Issue 3, Autumn 2022, Pages 595–624, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grac014

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The number of forcibly displaced persons has increased substantially since the early 2000s and has more than doubled in the last decade. Responding to the needs of forcibly displaced persons requires comprehensive legal and policy frameworks and evidence-based programmes that promote durable solutions, including sustainable movements out of poverty and their successful integration into hosting communities. In this paper, we review the dynamics of forced displacement in Colombia, the country with the largest number of internally displaced persons worldwide, and the progression of legal and policy frameworks that have been implemented since the late 1990s. We also review over two decades of research on the economic, social, and psychological consequences of forced displacement following an asset-based poverty trap framework that allows us to understand how forced displacement can alter poverty dynamics across time and generations. Throughout the review, we draw lessons for other contexts and countries affected by forced displacement and refugee flows.

I. Introduction

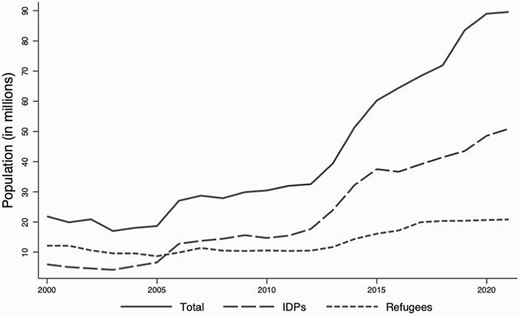

By the end of 2020, more than 82 million people were estimated to have been forcibly displaced worldwide due to ‘persecution, conflict, violations of humanitarian rights and events seriously disturbing public order’ (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2021). This figure includes 48 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), 26.4 million refugees,1 4.1 million asylum-seekers, and 3.9 million Venezuelans displaced abroad. Although forced displacement is not a new phenomenon, the magnitude of the crisis is unprecedented. The number of forcibly displaced persons and of those in need of protection and assistance has more than doubled in just one decade (see Figure 1) and is the highest at any moment in modern history, representing over 1 per cent of the global population. Moreover, this is a crisis that brings a higher burden to low- and middle-income countries, which host 85 per cent of all forcibly displaced persons.

Forcibly displaced persons worldwide 2000–20.Notes: The continuous line plots the evolution of the number of forcefully displaced persons, including IDPs, refugees, returnees, asylum seekers, and forced migrants, including Venezuelans, since 2018. The two dotted lines show the evolution of the number of IDPs and refugees. The figure is based on data from the UNHCR Refugee Population Statistics Database, retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ on 1 December 2021.

The magnitude of forced migration, along with (mis)perceptions about the consequences of increasing flows of refugees to high-income countries, has attracted the attention of governments, international organizations, donors, and researchers, all of whom are trying to address what it is currently known as the ‘Global Refugee Crisis’. However, as Figure 1 illustrates, this is not only a refugee crisis; this is a crisis of forcefully displaced persons in general. IDPs represent 58 per cent of the overall figure of forcefully displaced persons worldwide, and the increasing trend in the last decade of forced displacement is explained to a large extent by internal displacement.2 Importantly, and in contrast to refugees who are under the protection of the international community, the protection of IDPs is the sole responsibility of national governments, which brings additional challenges because they are facing war, conflict, or intense violence. Protecting the forcibly displaced population, including IDPs and refugees alike, is, therefore, one of the leading challenges in the developing world.

Responding to this challenge requires establishing comprehensive policy and legal frameworks and implementing evidence-based programmes to promote the social, economic, and psychological recovery of forcibly displaced persons and their successful integration into hosting communities. This process should be grounded in a better understanding of both the consequences of forced displacement and the characteristics, capacities, and needs of these populations. For example, legal frameworks should recognize that forced displacement is seldom a choice and, thus, they should have a different focus than frameworks implemented for regular migrants. Likewise, policy responses should consider that forced displacement often erodes a displaced person’s productive, social, and psychological capacities, thus hindering their right and opportunities to recover and to lead productive and fulfilling lives. A more informed understanding of the characteristics of forcibly displaced persons and of the mechanisms through which forced displacement increases their vulnerability to chronic poverty will facilitate the design of more effective policies and programmes and a shift away from standard policy responses.

While humanitarian assistance is a necessary component to address short-term needs, legal and policy frameworks should seek durable solutions focused on the capacities of forcibly displaced persons that enable recovery and resilience. A better understanding of the dynamics and consequences of forced displacement will reinforce the need to move beyond a standard humanitarian approach towards a development-oriented framework, as suggested by the Refugee Compact and the report of the UN Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement (United Nations, 2018; High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement, 2021).

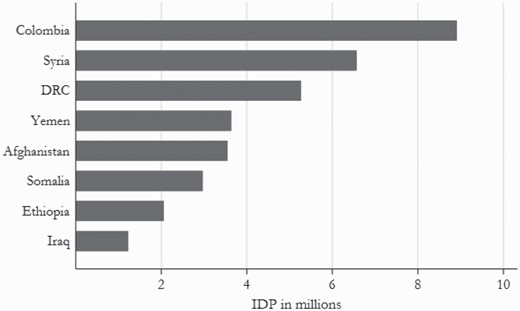

To contribute to understanding how to support forcibly displaced persons, we review a track record of over two decades of evidence, legal frameworks, and policies that have been implemented in Colombia to assist and support IDPs. Our focus on Colombia is first motivated by the magnitude of internal forced displacement, which has affected 8.2 million persons in Colombia.3 This figure corresponds to 16.4 per cent of the Colombian population and 17 per cent of IDPs worldwide. This figure also indicates that Colombia is the country with the largest internally displaced population in the world, surpassing other countries, such as Syria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Yemen, and Afghanistan, which have all received considerable attention recently (see Figure 2) (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2021).

Forcibly displaced persons worldwide 2000–20.Notes: Number of IDPs in the seven countries that host the highest number of IDPs worldwide, based on data from UNHCR Refugee Population Statistics Database, retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ on 1 December 2021.

Although the dynamics of conflict and internal displacement vary greatly across these different settings, our focus on Colombia is further motivated by the fact that there are key elements for which the Colombian case may be informative for other countries, as we discuss in section II. First, as we mentioned above, IDPs and refugees are largely hosted in low- and middle-income countries, such as Colombia, that are characterized by wider sources of risk and that lack resources to address the needs of forcibly displaced persons. Second, much like Colombia, some of these countries are also experiencing protracted and active conflicts where forced displacement is driven by violence and human rights violations, among other factors (High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement, 2021).4 The Colombian case highlights that it is both possible and necessary to protect forcibly displaced persons, even in resource-deprived contexts and in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Perhaps more importantly, our focus on Colombia is motivated by the breadth of evidence on the far-reaching consequences of forced displacement and the track record of the Colombian state in recognizing IDPs and implementing legal frameworks and policies to protect and support them. The review of this evidence and policy response is the focus of this article, which aims to contribute to highlighting key lessons and challenges that can inform policies and research in other countries torn by conflict and forced displacement, as well as in countries receiving refugees or other persons of interest. To date, 43 countries have put in place policies to address the needs of IDPs (High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement, 2021), 18 of which have enacted national laws of varying scopes.5 The lessons from Colombia that we discuss in this paper may contribute to strengthening existing policies in other countries and to the drafting of new ones in countries lacking the instruments to support IDPs.

To guide the discussion, we structure our review around a simple framework as follows. First, in section III, we review the progression and implementation of a policy framework to assist IDPs. Colombia has one of the more progressive and comprehensive policy frameworks in this area. The legal and policy responses by the Colombian state began in 1997 and have since evolved, in response to political debates, to the changing dynamics of the internal conflict and to the findings drawn from multidisciplinary academic research. This analysis can be informative for other contexts because it highlights the progression of this framework and how its focus shifted from providing humanitarian assistance and access to regular state services towards including specific components to promote more durable solutions.

The second element in our framework is the review of the evidence on the far-reaching consequences of forced displacement and its implications for poverty dynamics. We review this body of work in section IV, where we first take advantage of unique microlevel and administrative data, which allow us to assess how forced displacement alters poverty dynamics and to better understand the mechanisms through which it thrusts IDPs into a state of chronic poverty. Our take on this literature is guided by an asset-based approach to poverty traps, which highlights that by eroding the economic, social, and psychological assets of IDPs, forced displacement increases vulnerability to chronic poverty. This asset-based framework is useful to assess which components of the policy framework address the loss of assets and capacities and, thus, whether they promote sustainable movements out of poverty. Likewise, this framework allows us to draw lessons for other contexts and countries affected by forced displacement and refugee flows. Although the specific ways in which such asset losses manifest themselves may be different in each setting, understanding that forced displacement erodes productive, social, and psychological capacities can lead to the design of policies that are better suited to promote the recovery, resilience, and self-reliance of IDPs.

The third element of our framework, in section V, is the review of an upcoming body of work that has analysed the impacts of different programmes and policies aimed at improving the lives of IDPs. We conclude by summarizing lessons for the design of legal and policy frameworks that address the short-term needs of IDPs as well as their capacity to make sustainable transitions out of poverty.

II. Forced displacement in Colombia

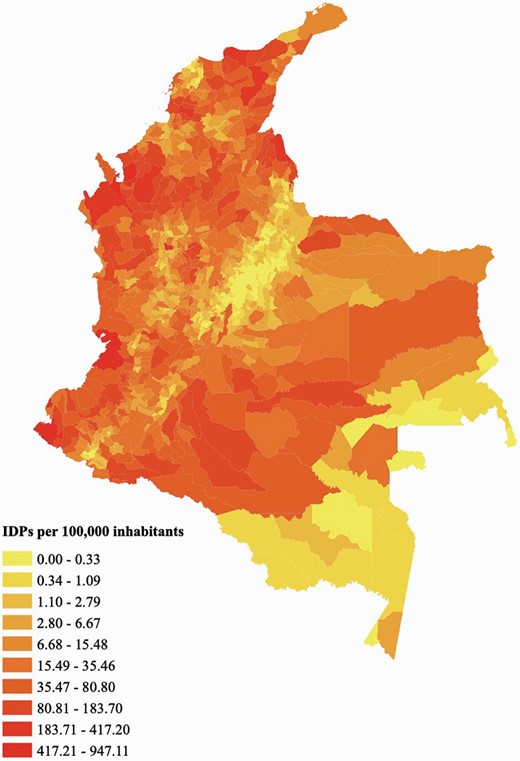

Internal forced displacement has been a constant presence throughout Colombian history. In the last two decades, the dynamics of displacement have increased both in the number of persons affected and in its geographical scope (see Figure 3). While in the 1990s, only 3 per cent of the municipalities in the country had been affected by displacement, by 2020, all municipalities had been affected by forced displacement.6

Geographic distribution of forced displacement in Colombia.Notes: The map illustrates the intensity (number) of displaced persons by municipality. The map is based on data from the Registro Unico de Victimas, retrieved from https://www.unidadvictimas.gov.co/es/reportes in December 2021.

The first wave of internal displacement occurred during the period known as La Violencia (1948–58), when more than 2 million people—10 per cent of the population—were displaced from rural to urban areas of the country (Schultz, 1971; Oquist, 1980; Karl, 2017). The second wave was triggered in the 1960s by the intensification of agrarian conflicts and the emergence of left-wing guerrilla groups in rural, southern regions of the country (Guzmán et al., 1963; Karl, 2017).7 In the 1980s, the emergence and increase in illegal crops intensified the conflict for two main reasons. First, they became an important financial source of the rebel groups and, second, these new resources also funded right-wing paramilitary groups aimed at protecting landowners and drug lords while restraining the expansion of the guerrilla groups (Duncan, 2006; Angrist and Kugler, 2008).

In this context, direct attacks on the civil population became a deliberate strategy of non-state armed groups to increase territorial control, prevent civil resistance, and weaken support for opponent groups (Engel and Ibáñez, 2007; Velásquez, 2008; Ibáñez and Moya, 2010b). Between 1970 and 1991, homicides more than tripled, and rural areas witnessed a spike in armed confrontations, massacres, attacks by armed rebels, and use of land mines (Grupo de Memoria Histórica, 2016). Forced displacement peaked between 2000 and 2004 and started to fall concomitantly once government negotiations with paramilitary groups started, leading to the demobilization of a large percentage of these groups in 2006. In 2012, the Colombian state and the FARC guerrilla began to craft a peace accord that led, in 2016, to the demobilization of over 12,000 combatants from the largest guerrilla group in the hemisphere. Unfortunately, despite the peace agreement, violence subsided only in some regions of the territory, and forced displacement more than doubled between 2020 and 2021.

Below, we describe some of the dynamics of forced displacement, how individuals and households are forced to migrate, and some of the characteristics of IDPs. This discussion, based on Ibáñez (2008), highlights some salient characteristics of forced displacement in Colombia that shaped the design of the Colombia policy.

First, forced displacement is classified as reactive when it occurs as a consequence of direct exposure to violence, or preventive when individuals migrate to avoid victimization that has not yet occurred. The former is the largest driver of displacement, representing 87 per cent of all displacement episodes in 2004 (Ibáñez, 2008). Reactive displacements are often triggered by the accumulation of multiple sources of violence, including direct threats, homicide or homicide attempts, forced disappearances, kidnappings, sexual violence, confrontations between armed groups, and massacres (Ibáñez, 2008; Gómez et al., 2015; Grupo de Memoria Histórica, 2016). This means that the vast majority of the IDPs in Colombia are victims of both direct violence and forced displacement.

Understanding these two types of forced displacement and the degree to which IDPs are also exposed to traumatic violence is important to identify the degrees of heterogeneity in the consequences of displacement and in the corresponding policy responses, which we analyse in the following two sections. For example, Ibáñez and Vélez (2008) find that the consequences of forced displacement on IDPs’ well-being are smaller for those who were displaced preventively, presumably because these IDPs are better able to prepare for the migration process by selling or protecting their assets and by contacting potential networks in their destination. These social networks, in addition, are important determinants of how IDPs decide where to migrate.

Second, the decision to ‘migrate’ is made at the household level, and in the vast majority of cases, all household members migrate together, which partially explains why most IDPs perceive their displacement as a permanent decision and why there are very few returns.8 In addition, most households migrate directly to their final destination, which half of the time is within the same department (Colombian state or provincial jurisdiction), and in approximately 18 per cent of the cases within the same municipality, to facilitate the protection of their assets and social networks in their place of origin.

Third, the vast majority of forced displacement in Colombia does not occur massively, but rather occurs by the displacement of one or a handful of households that settle in slums on the outskirts of urban areas.9 This is in stark contrast to other countries with high levels of IDPs, where displacement occurs massively and forced migrants reallocate to refugee camps and cross international borders (Summers, 2012). In fact, Colombian individuals seldom migrate internationally. In addition to identifying the key elements of the migration process, it is also important to characterize the displaced population to identify their vulnerabilities in the receiving municipalities (Ibáñez and Moya, 2007). Table 1 shows their main characteristics compared to poor households in urban regions, poor households living in rural regions, and homeless individuals living in urban places.10 An important takeaway from this table is that the displaced population has similar characteristics to the poor and most vulnerable population in Colombia: large households with a high dependency rate, low human capital, and female household heads; also, ethnic minorities are overrepresented in this population. We discuss the importance of these characteristics in the context of the consequences of displacement in section IV.

| Variable . | IDP . | Urban poor . | Rural poor . | Urban homeless . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | 4.9 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| Number of children under the age of 14 | 2.14 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| Number of individuals aged between 14 and 60 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Number of adults over the age of 60 | 0.23 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Female household head (%) | 38 | 35.7 | 22.7 | 37.5 |

| Widow household head (%) | 14 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 11.6 |

| Years of education of household head | 4.5 | 5.8 | 3 | 4.9 |

| Years of education of other adults over the age of 18 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 5.4 |

| Households who belong to an ethnic minority | 21 | 9.3 | 13.6 | 10.5 |

| Variable . | IDP . | Urban poor . | Rural poor . | Urban homeless . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | 4.9 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| Number of children under the age of 14 | 2.14 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| Number of individuals aged between 14 and 60 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Number of adults over the age of 60 | 0.23 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Female household head (%) | 38 | 35.7 | 22.7 | 37.5 |

| Widow household head (%) | 14 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 11.6 |

| Years of education of household head | 4.5 | 5.8 | 3 | 4.9 |

| Years of education of other adults over the age of 18 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 5.4 |

| Households who belong to an ethnic minority | 21 | 9.3 | 13.6 | 10.5 |

Notes: Table adapted from Ibáñez and Moya (2007).

| Variable . | IDP . | Urban poor . | Rural poor . | Urban homeless . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | 4.9 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| Number of children under the age of 14 | 2.14 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| Number of individuals aged between 14 and 60 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Number of adults over the age of 60 | 0.23 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Female household head (%) | 38 | 35.7 | 22.7 | 37.5 |

| Widow household head (%) | 14 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 11.6 |

| Years of education of household head | 4.5 | 5.8 | 3 | 4.9 |

| Years of education of other adults over the age of 18 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 5.4 |

| Households who belong to an ethnic minority | 21 | 9.3 | 13.6 | 10.5 |

| Variable . | IDP . | Urban poor . | Rural poor . | Urban homeless . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | 4.9 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| Number of children under the age of 14 | 2.14 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| Number of individuals aged between 14 and 60 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Number of adults over the age of 60 | 0.23 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Female household head (%) | 38 | 35.7 | 22.7 | 37.5 |

| Widow household head (%) | 14 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 11.6 |

| Years of education of household head | 4.5 | 5.8 | 3 | 4.9 |

| Years of education of other adults over the age of 18 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 5.4 |

| Households who belong to an ethnic minority | 21 | 9.3 | 13.6 | 10.5 |

Notes: Table adapted from Ibáñez and Moya (2007).

III. Policy framework and state response

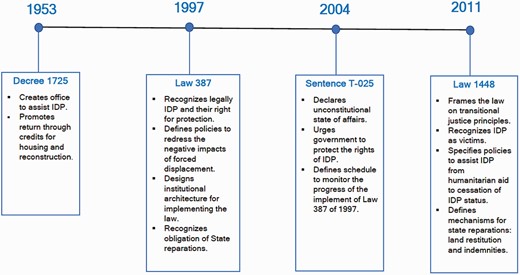

The Colombian state has developed progressive legislation to assist the victims of forced migration. These policies were designed and implemented during the armed conflict, which offers a unique setting in the world. In addition, the richness of the data available through the official registry and several surveys carried out since 1995 offer an opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of IDP policies and programmes. These policies have evolved through a trial-and-error process with strong involvement of the three state branches, international organizations, academics, and, most importantly, victim advocacy groups. The lessons learned from this process are consequential for countries tackling forced migration, including refugees. The purpose of this section is to critically discuss the evolution of Colombia’s policy for internal displacement to feed the policy recommendations discussed in section VI. Figure 4 depicts a timeline of the main legal provisions enacted by the Colombian state to address the needs of IDPs and to protect their rights.

The first state action to support IDPs was Decree 1725 of 1953. The Decree created an office within the Presidency of Colombia to assist forced migrants in their ‘economic rehabilitation’ by facilitating their return to their place of origin and providing credits for housing reconstruction.11 The policy was a small piece of a larger military strategy during the short dictatorship of General Rojas Pinilla to establish state control over conflict regions. Once democracy was restored, President Lleras Camargo implemented peace-making programmes for the reconstruction of rural areas and land restitution and promoted the return of rural dwellers who had fled to urban areas (Karl, 2017).

Law 387 of 1997, the first broad piece of legislation enacted by Colombia, legally defined the status of IDPs and sought to redress the negative impacts of forced migration.12 The goal of the law was to bring the IDPs back to their welfare levels before displacement. Ibáñez and Vélez (2008) estimate that welfare losses for the average IDP households in Colombia amounted to 37 per cent of the net present value of lifetime aggregate consumption.

The law was overly ambitious given the state’s capacity and the later intensification of IDP flows. In 1997, the number of IDPs was near 880,000, but grew to 3.5 million by 2002, the peak of yearly displacement, with 780,000 having been displaced that year alone.13 The law proved difficult to implement in a country ravaged by war, with a population that had many unmet needs, and due to the intense political opposition to the law. Weak state capacity also proved to be an important obstacle. The most limiting factors of state capacity for the purpose of having an effective policy response were related to the lack of strong coordination among several institutions and staff with experience in humanitarian assistance. The new responsibilities were not accompanied by additional resources and personnel and instead overburdened institutions. Nonetheless, some features of the Law were important and were later refined with additional legislation: (i) the legal recognition of IDPs and their right to protection; (ii) the creation of the State Registry for the Displaced Population (RUPD by its Spanish acronym; today, it is called the Registry for Victims—RUV); (iii) the obligation of state reparations through land restitution and indemnities; (iv) the acknowledgment of the need to design special interventions for IDPs instead of providing preferential access to anti-poverty and development programmes; and (v) the design of the institutional architecture for implementing the law.

The lack of wide political support for Law 387 weakened its implementation. The government of President Uribe pushed for the return of IDPs to their homelands due to the improvements in security conditions in many regions of the country and provided preferential access to government programmes while neglecting specific programmes for the displaced population. The Constitutional Court weighed in by declaring the situation unconstitutional and urged the national and local governments to protect the rights of the IDP population, forcing the government to comply with Law 387 of 1997. In addition, the Court defined a strict schedule to monitor the progress of IDP policies, in which it required the government to submit mandatory periodic reports and created an independent commission to apply a yearly representative household survey of IDPs to measure progress in the implementation of the law. The contempt of the Court’s mandate entailed legal implications for government officials, obliging the government to allocate additional resources to strengthen the IDP policy.14

The accumulation of knowledge on effective IDP interventions led a group of legislators and victim advocacy groups to design and propose a new law in 2007 to replace Law 387. The proposal adopted several provisions of Law 387 while incorporating new ones based on the lessons learned from 10 years of policy experimentation. The proposal broadened the scope and framed the law on transitional justice principles, recognizing IDPs as victims of conflict. Although the proposal faced intense political opposition, after 4 years, the Congress approved Law 1448 of 2011 amid the peace negotiations with the FARC.15 The Law legally recognizes IDPs as victims of the Colombian conflict, making it the largest and most ambitious reparation and peace-building programme in the world in absolute and relative terms (Sikkink et al., 2014; Guarin et al., 2021).

Law 1448 has two broad objectives to protect and support IDPs. First, it defined the different stages of IDP interventions from transition to the termination of IDPs’ legal status. Each stage covers policies designed to specifically address the needs of IDPs as well as the mandate for preferential inclusion in anti-poverty and social protection programmes. Law 1448 defined need-based criteria to cease special protection of IDPs, which implies that the legal status of IDPs ends when a person achieves ‘socioeconomic stabilization’. In 2015, the national government defined the criteria for identifying whether a household had overcome the vulnerability conditions caused by internal displacement. This threshold is considered to be achieved: (i) once the rights of the household, grouped into seven dimensions, are fulfilled;16 (ii) when the household’s monthly income is 1.5 times the poverty line and the rights to health, education, identification, and family reunification are fulfilled; or (iii) when the victim voluntarily requests to be withdrawn from the victims registry. Until the conditions of vulnerability are overcome, the IDP population continues to be under special protection of the state. Ibáñez et al. (2012) simulate the fiscal impacts of not achieving this goal and find that the increasing demand for fiscal resources renders Law 1448 unsustainable in the future.

Second, the law defines two mechanisms to compensate IDPs for their losses: indemnities and land restitution. Indemnities are a one-time lump sum of up to US$10,000, which is the equivalent of 3.3 times the annual household income of IDPs (Guarin et al., 2021). To provide incentives to victims to adequately invest the indemnity, recipients need to participate in investment workshops and government fairs. These compensation mechanisms seek a twofold objective: to recognize the suffering that victims have experienced and to help them move out of poverty, akin to development programmes (Vallejo, 2021) (see section V). In contrast, land restitution follows a three-stage process. First, the national government identifies areas to initiate the restitution process based on security conditions, density of land claims, and local conditions for the return. Claimants may, in parallel, apply to the Restitution Unit (URT) of the Ministry of Agriculture requesting inclusion in the Registry of Forcibly Usurped and Abandoned Land (RUPTA is its Spanish acronym). If the request is approved for eligibility by the URT, the claimant or the URT should file a legal claim to a restitution judge. By 2019, the number of hectares registered in RUPTA amounted to 7.3 million hectares (Arteaga et al., 2017).

The pace of the effectiveness of state support for IDPs increased gradually. By the end of October 2021, the percentage of compliance with the seven dimensions to overcome the vulnerability conditions caused by displacement ranged between 0.5 per cent for family reunification and 94 per cent for health coverage.17 With respect to restitution and compensation policies, as of August 2021, 1.1 million victims had received indemnities to a value of US$2.2 billion, equivalent to 0.8 per cent of Colombia’s GDP (Guarin et al., 2021). Judicial sentences for restitution by September covered nearly 485 thousand hectares.18 The slow pace of restitution is explained by the pervasive informality of property rights—63 per cent of hectares registered in RUPTA lack a legal title (Arteaga et al., 2017)—institutional overload, the difficulties on the ground brought by subsequent good-faith occupants, and a low willingness to return by many IDPs (García-Godos and Wiig, 2018).

The following sections examine how the consequences of forced displacement in Colombia may create poverty traps for the IDP population and discuss the effect of government interventions on their lives.

IV. Microlevel consequences of forced displacement

What are the consequences of forced displacement, and how do they alter IDPs’ socioeconomic trajectories? We examine these questions by taking advantage of rich micro- and administrative-level data and over 20 years of research on the consequences of forced displacement.19 Our review, however, is not intended to be comprehensive. On the one hand, it is largely based on economics research and mainly draws on our own work on the topic. Although we review some studies in psychology and law, we do not do justice to the immense body of interdisciplinary work on the topic, because a proper review falls beyond the scope of this article. On the other hand, because we are interested in highlighting lessons that can strengthen policy frameworks to support forcibly displaced populations, our review does not address the impacts of displacement flows on host communities.20 Despite the rather narrow focus, our review provides a picture of the persistence of poverty among IDPs and allows us to understand the mechanisms through which forced displacement can lead to the reproduction of poverty across time and generations. In doing so, we provide a conceptual framework that reinforces the need to move towards more durable solutions to support forcibly displaced persons in Colombia and elsewhere.

(i) Poverty

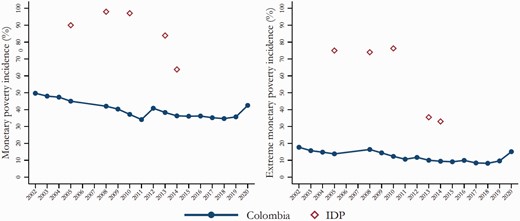

We first analyse the evolution in poverty and extreme poverty rates for IDPs and compare it with national trends. We pool together data from the different surveys, which we describe in the Appendix, along with official figures on poverty rates available from the Colombian National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE is its acronym in Spanish). In Figure 5, we plot the poverty and extreme poverty rates for IDPs as estimated by the different surveys, along with the corresponding national figures. Although we cannot ensure that the methodologies for estimating household income are entirely comparable across surveys, the two figures allow us to illustrate IDPs’ vulnerability to poverty. For instance, in 2005, the data from Deininger et al. (2005) reported poverty and extreme poverty rates of 90 and 75 per cent, respectively. These were more than two and five times above national averages, respectively. Similar figures were observed by the National Monitoring Commission on Public Policies for Forced Displacement in 2008 and 2010.

Poverty and extreme poverty rates—IDPs vs national averages.Notes: Evolution of poverty and extreme poverty rates (% of the population below the national income poverty and extreme poverty line). The continuous lines illustrate national poverty and extreme rates according to official statistics from DANE. The diamonds illustrate the poverty and extreme poverty rates for IDPs as estimated by the following studies. 2005: Deininger et al. (2005); 2008: Comisión de Seguimiento a la Política Pública sobre Desplazamiento Forzado en Colombia (2008); 2010: Comisión de Seguimiento a la Política Pública sobre Desplazamiento Forzado en Colombia (2010); 2013: Contraloría General de la República de Colombia (2015); 2014: Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (2015).

More recent figures indicate that IDP poverty and extreme poverty rates have declined. For example, the data from the National Victims Unit reported poverty and extreme poverty rates of 64 and 33 per cent, respectively, which are well below those estimated in the mid-2000s. This trend may be partially explained by the strengthening of support programmes for IDPs. Despite this progress, in 2013 and 2014, the IDP population was still 1.7 and 3.5 times more likely to be below the poverty and extreme poverty lines, respectively, relative to national averages. Hence, the data in Figure 5 illustrate the larger vulnerability of IDPs to poverty that has persisted over time, even after the implementation of a comprehensive and progressive policy framework. This picture is consistent with recent data from the National Victims Unit, which finds that 62 per cent of IDPs are still in a state of vulnerability.21

While thought provoking, the analysis above does not demonstrate a causal effect of forced displacement on socioeconomic well-being. Nonetheless, we can build upon the analysis from Ibáñez and Moya (2010b) to illustrate how forced displacement brings about substantial drops in income and consumption levels and how IDPs are not able to recover over time. In Figure 6, we replicate the data from Ibáñez and Moya (2010b), illustrating the evolution of average annual (aggregate) income and consumption per equivalent adult before and after displacement, stratifying the data according to the time of settlement—less than 3 months after being displaced, between 3 and 12 months, and over 12 months. The left-hand panel of Figure 6 illustrates how income plummets in the first 3 months after the displacement. Relative to the levels prior to displacement, this represents a loss of 95 per cent of annual income per equivalent adult. Over time, income levels slowly follow an upward trajectory, but IDPs do not fully recover; even for those who were displaced 12 months or more before the date of the survey, income losses were still over 60 per cent relative to pre-displacement levels.

Aggregate income and consumption before and after forced displacement.Notes: The figure illustrates the evolution of annual income and consumption per equivalent adult before and after displacement using the data from Ibáñez and Moya (2010a).

The income shock caused by displacement, coupled with the lack of access to formal risk-sharing mechanisms and the disruption of social networks, results in substantial losses in consumption. In the right-hand panel of Figure 6, we illustrate how forced displacement affects consumption by plotting the evolution of annual consumption per equivalent adult. In the first 3 months after being displaced, consumption falls by 24 per cent relative to pre-displacement levels. While this fall is sizeable, the reception of humanitarian aid from governmental and non-governmental organizations likely prevents the severe income shock from translating into a similarly severe consumption shock (Ibáñez and Moya, 2010b). However, as IDPs settle and lose access to such aid, consumption levels continue to fall. For IDPs displaced for 12 or more months, the fall in consumption represents a 36 per cent loss relative to pre-displacement levels.

The analysis above portrays a picture of the short- and medium-term impacts of forced displacement based on 2005 data from Ibáñez and Moya (2010a). At the time of this study, a large majority of IDPs had not been included in the national registry for the displaced population, and only 43 per cent received any type of support—mainly humanitarian aid. Since then, the majority of victims of displacement have been included in the RUV, and support has been strengthened and made more widely available following the Constitutional Court ruling of 2004 and the enactment of the 2011 Victims’ Law that were discussed in the previous section. Well-being and living conditions may have improved for IDPs, presumably as a result of such progress. Nevertheless, the analysis in this section points towards the persistence of vulnerability to poverty among IDPs, a vulnerability that is well above that of the Colombian population. The analysis below on the asset losses caused by displacement will allow us to understand the mechanisms through which forced displacement drives IDPs into persistent and chronic poverty.

(ii) Multidimensional asset losses

How does forced displacement contribute to trapping IDPs in poverty? The evidence we present below indicates that forced displacement leads to the erosion of the asset base of IDPs, broadly understood as encompassing productive, physical, human, social, and psychological assets. Although most of the studies in our review document short- and medium-term effects, we also identify the key mechanisms through which these effects can have intertemporal and intergenerational consequences. Specifically, we guide our review from the perspective of an asset-based framework to poverty traps (Carter and Barrett, 2006; Barrett and Carter, 2013). Under this conceptual framework, the multidimensional asset losses that forced displacement brings about can be understood as hindering IDPs’ productive capacities, trapping them into a low-level equilibrium and a condition of chronic and persistent poverty.

Socioeconomic assets and capacities

Deininger et al. (2005) document that over 60 per cent of IDPs had access to land and that 81 per cent derived their livelihoods from agricultural activities before being forcefully displaced. As a result of the forced displacement, the large majority of IDPs abandoned their lands or were coerced to sell them well below market prices (Grupo de Memoria Histórica, 2016). Estimates by Arteaga et al. (2017) indicate that forced displacement led to the loss of 7.3 million hectares, which represents 29 per cent of lands suitable for agricultural activities in Colombia. IDPs were also forced to abandon agricultural investments, livestock, and other productive assets. Over time, few IDPs are able to recover their productive asset base. The loss of assets worsens throughout the duration of settlement, as IDPs either lose control of the assets they were still able to control or are forced to sell them to smooth consumption (Deininger et al., 2005). Forced displacement is also associated with the erosion of human assets (capital), which then becomes an obstacle for accessing labour markets at destination sites and for generating income. We identify two mechanisms through which this takes place that build upon the analysis by Ibáñez and Moya (2007). First, IDPs are displaced to a large extent from rural to urban areas, and not only are they less educated with higher illiteracy rates than the urban poor, but their agricultural skills and knowledge also ‘depreciate’ as they are of little or no use in urban labour markets. Second, the shock of forced displacement and the violence that often precedes it increase the demographic vulnerability of displaced households either by the disruption of households in reception sites, the loss of working-age members, and the increase in dependency rates, or by leading to higher rates of female-headed households. These two factors add up to the vulnerable socioeconomic and demographic profile of IDPs that we mentioned in the previous section. Together, they imply disadvantages in urban labour markets that translate into above normal rates of unemployment and a higher likelihood of employment in informal, low-skilled, and low-paying jobs.22

The third dimension of asset losses refers to the disruption of social networks and social capital or assets in general. As happens in developing contexts characterized by multiple market failures, before displacement, IDPs relied on social networks to fund productive activities and to mitigate the consequences of idiosyncratic shocks, allowing them to smooth both consumption and assets. However, armed conflict and forced displacement in Colombia disrupt these social networks and erode social assets in general. Because the majority of IDPs are then displaced individually or in small groups and many choose to settle in large cities where they are able to remain anonymous or invisible, social networks are further disrupted. As a result, IDPs lose the ability to overcome market failures and to smooth consumption through social assets. For example, Ibáñez and Moya (2007) find that relative to pre-displacement levels, access to informal credit falls by 54 per cent (from 17.1 to 9.3 per cent), while participation in community organizations also falls substantially. Together, the disruption and loss of social assets contribute to explaining why a considerable portion of the income shock that results from forced displacement translates into a severe and permanent shock to consumption and well-being, as we observed in Figure 6.

The evidence that we have discussed thus far provides a picture of asset losses and their implications from a standard socioeconomic perspective. This body of research speaks to the progression of the policy framework that is discussed in detail in the previous section by providing evidence that supports the mandate for preferential inclusion of IDPs in anti-poverty programmes and programmes that move beyond standard humanitarian programming towards a more comprehensive strategy that replenishes IDPs’ asset base to ensure their ‘socioeconomic stabilization’ and sustainable movement out of poverty.

Psychological assets and capacities

The consequences of forced displacement are far reaching, and the resulting asset losses are not limited to socioeconomic domains. Forced displacement also takes a toll on IDPs’ mental health, and this also has implications for their capacity to recover. In fact, a large body of work has studied the psychological consequences of forced displacement (see Shultz et al. 2014; Gómez-Restrepo and de Santacruz, 2016; Moya, 2018; Cuartas et al., 2019; León-Giraldo et al., 2021 to name a few), finding that the traumatic episodes of forced displacement, along with the violence that precede it, result in a myriad of psychological disorders, including chronic anxiety, severe depression, and post-traumatic disorders. The manifestations of mental illness are significant; for example, Moya (2018) finds that the incidence of at-risk symptoms of anxiety and depression is three and four times larger among IDPs than in the general Colombian population.23

The psychological consequences of forced displacement are important by themselves because they directly affect IDPs’ well-being. However, these consequences also have negative effects on different socioeconomic domains and can contribute to keeping IDPs in chronic poverty.24 Research among IDPs (or victims of violence) in Colombia has demonstrated that forced displacement and exposure to traumatic episodes of violence distort cognition (Bogliacino et al., 2017), increase risk aversion (Moya, 2018), and lead to overly pessimistic perceptions about the ability to recover and move out of poverty (Moya and Carter, 2019).25 These cognitive and behavioural effects can then have negative effects on productivity levels, educational attainment, saving and investment decisions, and behavioural biases, among others, as demonstrated by research in other countries (Ridley et al., 2020). In doing so, the psychological consequences of forced displacement can increase vulnerability to poverty and can hinder the effectiveness of standard socioeconomic programmes. For example, Moya et al. (2021a) find that among young IDPs participating in a vocational job-training programme, baseline levels of post-traumatic stress disorder were associated with fewer hours attended and lower rates of graduation from the programme, with a lower likelihood of obtaining formal employment and with lower labour income. These effects are sizeable and potentially long-lasting. For example, a one standard deviation in baseline symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder is associated with a reduction of 10 per cent in labour wages and persists 18 months after the job-training programme concluded.

The evidence on the psychological and behavioural consequences of displacement highlights the existence of a psychological poverty trap that would reinforce the already pervasive effects of the socioeconomic poverty trap. Understanding this interplay between the psychological consequences of forced displacement and the socioeconomic trajectories of IDPs is important because it provides evidence of a different mechanism through which forced displacement can contribute to the persistence of chronic poverty. In addition, it further supports the urgency of improving access to mental health services along with standard ‘anti-poverty’ programmes. Unfortunately, approximately 90 per cent of IDPs have not been able to access mental health services, revealing that mental health has received less attention and resources within the policy framework to support IDPs.

Intergenerational domains

Finally, a small but growing body of work documents the intergenerational consequences of forced displacement. Perhaps surprisingly, recent work by Monroy (2018) finds that forced displacement is associated with positive effects on school enrolment and completion. Employing a between-siblings identification strategy, he finds that schooling outcomes improve for the children who were displaced from rural to urban areas relative to their siblings who stayed behind or who completed their schooling process before being displaced. These effects are likely explained by higher access to schools and better-quality schooling in urban areas and by the preferential inclusion in conditional cash transfers that require children to attend schools and health check-ups, but also by the disruption of educational services in rural areas where conflict is still active. However, when comparing displaced and urban poor children, the former are at a disadvantaged position and have lower attendance and completion rates, which then result in further disadvantages in labour markets (Ibáñez and Moya, 2007). This is consistent with the only study that we have identified that provides a long-term perspective on the effects of La Violencia, which finds negative and sizeable effects in schooling attainment, which then translates into employment in less qualified sectors and lower employment rates in manufacturing and services (Fergusson et al., 2020).

The experience of forced displacement, or the violence that leads to forced displacement, during the first 5 years of life hinders early childhood development and can thus derail life trajectories and bring about intergenerational effects. Becerra (2014) finds that children who experience the forced displacement of their families during the first years of life have an 18 per cent higher likelihood of being chronically malnourished, and their size-for-age score is 0.35 standard deviations lower than that of children in the same families who did not experience the shock of displacement during early childhood. Recent work by Moya et al. (2021b) suggests that experiencing violence and forced displacement at an early age is associated with higher levels of childhood trauma, which then take a toll on early childhood mental health and cognitive and socioemotional development. The effects of forced displacement in early childhood compromise children’s opportunities to lead healthy and productive lives and are a mechanism through which forced displacement reproduces poverty and exclusion over time and across generations. Unfortunately, and differently from what happens with anti-poverty programmes and to a lesser extent with mental health programmes, the policy framework does not incorporate specific programmes to protect the mental health and early childhood development of children who have been exposed to violence and forced displacement.

(iii) Policy implications

These conclusions are a call to action for more comprehensive strategies based on a better understanding of the characteristics and needs of displaced populations and on the ways in which asset losses operate. There is an obvious humanitarian aspect to the crisis of forced displacement, and policy responses should address immediate needs, for example, by providing food aid or cash transfers to prevent further well-being losses in the short run.

However, humanitarian programmes cannot and do not intend to address persistent poverty among IDPs. Achieving durable solutions, therefore, rests on the capacity to move beyond standard programming and implement programmes that replenish displaced persons’ economic, social, and psychological assets or capacities. Development-oriented frameworks can thus combine humanitarian aid or cash transfers with indemnities and land restitution to address the loss of physical assets, vocational training or skill certification to address the erosion of human assets, and psychosocial support programmes to address the loss of psychological assets. Moreover, to the extent that the loss of economic, social, and psychological assets reinforce one other (Moya and Carter, 2019), it is possible that addressing one dimension at a time will be insufficient to break the underlying poverty traps.

V. Policy effectiveness

In this section, we provide a brief overview of upcoming research on the effectiveness of policies and programmes implemented to support IDPs. We review work across four different dimensions: (i) IDP registration and information; (ii) standard anti-poverty programmes (conditional cash transfers); (iii) programmes specifically designed for IDPs; and (iv) reparations and land restitution. We review this evidence through the lens of the asset-based conceptual framework we developed in the previous section. This lens allows us to understand how policies and programmes address different constraints faced by IDPs and to distinguish between those that address short-term humanitarian needs, those that can be thought of as an extension of standard anti-poverty programming, and those that target IDPs’ capacities and assets and that are better suited to promote durable solutions. We summarize the findings of this review in Table 2.

| Registration and information about benefits . | IDP specific programmes . | Antipoverty programmes with preferential access for IDPs . | Compensation: restitution and indemnities . |

|---|---|---|---|

| • IDPs dispersed: demand-driven instrument • Registration as IDP guarantees eligibility to receive aid and legal protection • By 2005: 70% of IDPs registered • Most vulnerable groups were not registered • Low take-up of aid (56%) • SMS messages: increased take-up 12 pp | • Income-generating programmes: + effects on income and consumption only in the very short term. Benefits do not persist in the long term • Psychosocial interventions: + impacts on maternal mental health, early childhood development and entrepreneurship | • + impact of CCT on education, health, and nutrition • Using existing infrastructure: useful but not sufficient to guarantee aid dependency | • Large and potentially sustainable impacts on economic and social outcomes • Move from low-wage to high-wage jobs • Investment in education • Higher trustworthiness |

| Registration and information about benefits . | IDP specific programmes . | Antipoverty programmes with preferential access for IDPs . | Compensation: restitution and indemnities . |

|---|---|---|---|

| • IDPs dispersed: demand-driven instrument • Registration as IDP guarantees eligibility to receive aid and legal protection • By 2005: 70% of IDPs registered • Most vulnerable groups were not registered • Low take-up of aid (56%) • SMS messages: increased take-up 12 pp | • Income-generating programmes: + effects on income and consumption only in the very short term. Benefits do not persist in the long term • Psychosocial interventions: + impacts on maternal mental health, early childhood development and entrepreneurship | • + impact of CCT on education, health, and nutrition • Using existing infrastructure: useful but not sufficient to guarantee aid dependency | • Large and potentially sustainable impacts on economic and social outcomes • Move from low-wage to high-wage jobs • Investment in education • Higher trustworthiness |

| Registration and information about benefits . | IDP specific programmes . | Antipoverty programmes with preferential access for IDPs . | Compensation: restitution and indemnities . |

|---|---|---|---|

| • IDPs dispersed: demand-driven instrument • Registration as IDP guarantees eligibility to receive aid and legal protection • By 2005: 70% of IDPs registered • Most vulnerable groups were not registered • Low take-up of aid (56%) • SMS messages: increased take-up 12 pp | • Income-generating programmes: + effects on income and consumption only in the very short term. Benefits do not persist in the long term • Psychosocial interventions: + impacts on maternal mental health, early childhood development and entrepreneurship | • + impact of CCT on education, health, and nutrition • Using existing infrastructure: useful but not sufficient to guarantee aid dependency | • Large and potentially sustainable impacts on economic and social outcomes • Move from low-wage to high-wage jobs • Investment in education • Higher trustworthiness |

| Registration and information about benefits . | IDP specific programmes . | Antipoverty programmes with preferential access for IDPs . | Compensation: restitution and indemnities . |

|---|---|---|---|

| • IDPs dispersed: demand-driven instrument • Registration as IDP guarantees eligibility to receive aid and legal protection • By 2005: 70% of IDPs registered • Most vulnerable groups were not registered • Low take-up of aid (56%) • SMS messages: increased take-up 12 pp | • Income-generating programmes: + effects on income and consumption only in the very short term. Benefits do not persist in the long term • Psychosocial interventions: + impacts on maternal mental health, early childhood development and entrepreneurship | • + impact of CCT on education, health, and nutrition • Using existing infrastructure: useful but not sufficient to guarantee aid dependency | • Large and potentially sustainable impacts on economic and social outcomes • Move from low-wage to high-wage jobs • Investment in education • Higher trustworthiness |

(i) Registry and information

The first dimension we review analyses the capacity of the Colombian state to register and provide aid to IDPs and the impact of different programmes to increase registration rates and aid take-up through the provision of information. Identifying IDPs is the first step towards establishing appropriate policy responses. In Colombia, this brought about different challenges than those that emerged in other settings because displacement often takes place on an individual basis, and IDPs are dispersed throughout the country and are not settled in displaced camps. To address these challenges, the Colombian government designed a demand-driven mechanism whereby IDPs approach a government institution to declare the circumstances and drivers of their displacement (Ibáñez and Velásquez, 2009). Once these circumstances are verified, IDPs are registered and become eligible to receive aid and access the different components embedded in the legal frameworks we discussed in section III.

The efforts to identify and register IDPs in Colombia and to provide aid have been one of the success stories (Sikkink et al., 2014) of the existing framework; this success involved overcoming different obstacles, and academic research played a role in both highlighting these obstacles and providing alternatives to address them. For example, a study by Ibáñez and Velásquez (2009) found that in 2005, seven out of every 10 IDPs were registered and that exclusion from the registry was explained by a lack of information on the part of the most vulnerable groups of displaced persons rather than by institutional decisions or processes. In other words, the Colombian state was partially successful in rapidly reaching the majority of IDPs through demand-side mechanisms. Nonetheless, red tape procedures and bureaucratic obstacles resulted in a lengthy process and delays in the delivery of humanitarian aid. On average, IDPs had to wait approximately 4 months between their declaration and the reception of humanitarian aid (Blanco and Vargas, 2014). In later years, the Constitutional Court’s ruling that called for improvements and greater efficiency in the registry was instrumental in expanding its reach to most IDPs (Sikkink et al., 2014), and this effort has been sustained up to this point, and now 8.2 million displaced persons are officially recognized as such.

Beyond the early progress in registering IDPs, which was a prerequisite for the delivery of humanitarian aid, the take-up rate of benefits was low and largely explained by information constraints. In 2009, for example, only 56 per cent of those registered had received some type of aid (Ibáñez and Velásquez, 2009). To alleviate such information constraints and increase the take-up of benefits, Blanco and Vargas (2014) designed a randomized controlled trial through which SMS messages were delivered with information about aid eligibility. This low-cost intervention increased the take-up of benefits by 12 percentage points and later was scaled up to all IDPs, demonstrating the role that research played early on in improving state-led policies and programmes.

Despite the potential and scalability of the SMS intervention, information constraints still prevented the more vulnerable IDPs and those in isolated areas from accessing the benefits provided by the state and even registering, as we mentioned above. To address this challenge and to increase the take-up and knowledge of the Victim’s Law, the Colombian government rolled out the Mobile Victims Unit (MVU) across isolated communities. Between 2012 and 2014, the MVU was near 31 thousand victims in 164 municipalities. Following the phase-in design of the MVU, Vargas et al. (2019) found that the programme did not increase knowledge of the benefits and services included in the Victim’s Law but had a sizeable and statistically significant 8 percentage point effect on the likelihood of registering in the RUV, which corresponds to a 10 per cent effect relative to the 84 per cent control mean. More importantly, the MVU increased the likelihood of receiving reparations or aid by 21 percentage points, which corresponds to a 150 per cent effect over the control mean. Nonetheless, IDPs served by the MVU became more pessimistic and less likely to make investment plans for the future. These latter results may be partially explained by a sense of frustration regarding the delivery, timeliness, and dosage of the state-led support and by the fact that the MVU registration process made the experience of victimization salient, which could have triggered different behavioural reactions consistent with the findings of Moya (2018).

The evidence from this subsection highlights the importance of creating registries to identify IDPs and quantifying and targeting the demand for aid but also to address supply- and demand-side constraints that may hinder registration and access to available services. Furthermore, our discussion highlights the positive effects of academic research in evaluating and informing programmes and services to identify and address such constraints.

(ii) Standard anti-poverty programmes: conditional cash transfers

In addition to humanitarian aid, the Colombian state supported IDPs within the framework of standard social services originally designed for poor and vulnerable households, including subsidized health care and education and conditional cash transfers. This approach has the advantage of leveraging existing programmes, capacities, and delivery platforms and thus allows assisting IDPs on a more permanent basis, shifting from emergency to more stable support, without requiring investing in the design of new programmes or delivery platforms. Within these services, the Constitutional Court Ruling of 2004 established the preferential access of IDPs to these social protection policies. In practice, this means that IDPs’ access is not conditioned on the standard socioeconomic eligibility requirements that are used to target social programmes.

In this subsection, we review the impact evaluation of the Familias en Acción (FeA) conditional cash transfer programme. Displaced persons are eligible to receive the FeA if, in addition to being registered in the RUV, they fulfil the standard eligibility criteria of conditional cash transfer programmes: (i) having children under 18 years of age in their household; and (ii) the children attending school and attending health and nutrition check-ups.

The impact evaluation of the FeA programme for displaced samples leveraged data from a sample of 147,376 recipients living in 821 municipalities and 203,000 non-beneficiary eligible IDPs (Centro Nacional de Consultoria, 2008). The evaluation found that the programme had a positive effect on the outcomes in which the conditionality is binding, such as children’s education, health, and nutrition, especially for young children under the age of seven. However, the FeA programme did not result in lowering the risk of malnutrition, which has a higher incidence among displaced households, and there is no evidence that the programme allowed displaced children to catch up with non-displaced children. Furthermore, the programme did not bring about positive effects on household well-being, household income, economic independence, or self-sufficiency. This latter result is not surprising to the extent that conditional cash transfer programmes are not designed to alter poor and vulnerable households’ socioeconomic dynamics in a profound way, but rather to break the intertemporal transmission of poverty across generations.

Taking these results in perspective, our review suggests that including IDPs within standard social protection platforms may be an efficient mechanism to expand coverage and reach larger segments of displaced persons. However, standard social protection policies are not designed to address the specific characteristics and vulnerabilities of IDPs, including their experiences of violence and trauma, their cultural uprooting, and the loss of livelihoods and multidimensional assets and capacities (Centro Nacional de Consultoria, 2007). While they may provide much necessary relief, this means that they will not allow IDPs to catch up or to break the intertemporal and intergenerational transmission of poverty and cannot be thought of as the main strategies for socioeconomic stabilization. Specific programmes that build upon or enhance anti-poverty strategies are much needed; this is the focus of the next subsection.

(iii) Programmes specifically designed for IDPs

We now review observational and experimental evidence on the impacts of programmes specifically designed for IDPs or those that build upon standard anti-poverty programming and include additional components that consider IDPs’ characteristics and needs.

The first set of evidence comes from two studies that assess the effectiveness of an income generating program, funded by USAID, that sought to replenish IDPs’ productive capacities. Specifically, the programme provided a one-time cash transfer, a standard job-training component, and a short-term contract with private firms. An observational analysis by Ibáñez and Moya (2010b) and a structural analysis by Helo (2009) indicate that the programme produced positive impacts on labour income and consumption but that the effects dissipated shortly after the programme ended and did not translate into sustainable livelihoods or stable employment. This evidence suggests that cash transfers provide much necessary relief and perhaps enhanced participation by covering the opportunity cost of participating in the programme, but that they did not enable households to invest in productive capacities and assets. Furthermore, the standard job-training component is not adequately powered to replenish the skill and human capacities of IDPs whose previous agricultural background is of little to no use in urban markets. Building upon the findings from Moya et al. (2021a) discussed above, these two studies suggest that, by not incorporating the psychological effects of forced displacement and how they affect socioeconomic dynamics, standard income-generation programmes may be ineffective.

Building upon this last insight, recent job-training programmes have included psychosocial or soft skill components as a way to address the psychological consequences of forced placement or deficiencies in socioemotional domains. The evidence on their effect, however, is mixed. An ongoing experimental study by Maldonado (2021) analyses the effect of complementing the standard job-training programme offered by the Servicio Nacional de Aprenizaje of the Colombian government with a soft-skill training module, which aims to promote teamwork, problem solving, and socio-emotional regulation. By addressing IDPs’ skill deficiencies across standard and socio-emotional domains, the bundled soft-skill and job-training programme was thought to have a stronger potential towards generating sustainable effects on labour-market outcomes. However, preliminary results find no effects of the soft-skill programme by itself and only negligible effects of the job-training strategy as a whole. While soft skills are essential for labour market dynamics, the results from Maldonado (2021) suggest that soft skills are endogenous to the psychological toll of forced displacement and, thus, programmes should have more comprehensive approaches to the socio-emotional and psychological domains.

Indeed, recent evidence from two experimental studies that were in development when the Covid-19 pandemic started suggests that better-informed psychological interventions embedded within job-training or entrepreneurship programmes have a higher potential for generating resilience and positive effects across psychological and socioeconomic domains. First, Ashraf et al. (2021) implemented a ‘mental imagery intervention’ designed to improve the way in which individuals project themselves into the future and move beyond pessimistic attribution styles on top of an entrepreneurship programme for vulnerable youth, many of whom are victims and IDPs. Ashraf et al. (2021) find that the intervention brought about significant effects on earnings even during the pandemic and that effects were larger for psychologically at-risk participants at baseline. Second, Antunes et al. (2021) evaluated the effectiveness of bundling a psychosocial support programme that combined soft-skill training and psycho-social counselling with a job-training programme. Similar to the effects from Ashraf et al. (2021), they find that the treatment allowed vulnerable and conflict-affected youth to better cope with the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, specifically to better manage symptoms of depression and anxiety, even though it did not lead to significant effects on labour market outcomes. Despite the pervasiveness of the Covid-19 pandemic and related lockdowns, which led to a 100 per cent increase in the unemployment rate in mid-2020, the evidence from these two studies speaks to the synergies that can be created by combining psycho-social and socioeconomic interventions and that can prove to be effective at breaking the reinforcing effects of socioeconomic and psychological poverty traps. These studies, however, provide only preliminary and short-term evidence, and there is a need for studies that analyse the effects of these comprehensive interventions over a longer period of time.

The programmes discussed above have focused on the socioeconomic recovery of IDPs by introducing standard socioeconomic programming by itself or by combining it with psychological components. In parallel, recent interventions have been designed to address the psychological consequences of forced displacement, and these interventions not only have promising results on the capacity to restore IDPs’ mental health but also to permeate socioeconomic domains and break the intertemporal and intergenerational transmission of poverty and trauma.

Semillas de Apego, for example, is a community-based psychosocial programme for primary caregivers of children aged 0–5 in communities affected by violence or forced displacement. The goal of the programme is to directly improve maternal mental health as an outcome of direct importance but also as a way to improve the emotional bonds between children and caregivers that are necessary to protect and promote early childhood development. The experimental evaluation of the programme found that, at the 8-month follow-up, the programme had positive and sizeable effects on maternal mental health, child–mother interactions, and early childhood development (Moya et al., 2021b). Moreover, preliminary results from the impact evaluation suggest that the mental health intervention also allowed caregivers to better project themselves towards the future and to rediscover a sense of resilience and empowerment not only in psychosocial domains but also in terms of their educational attainments and labour-market outcomes.

Likewise, Idrobo et al. (2021) analyse the (non-experimental) impacts of the forgiveness and reconciliation clinics that have been implemented across conflict-affected regions of the country and that are characteristic of transitional justice and peace-building initiatives in other post-conflict countries. The forgiveness and reconciliation clinics led to sizeable improvements in the mental health of the participants but also found that this resulted in improvements in their social connectedness and prospects of life trajectories, which are consistent with the results of Ashraf et al. (2021) and Moya et al. (2021b) discussed above.

(iv) Compensation: indemnities and land restitution

Section IV documents the significant vulnerability to poverty of the IDP population, which has persisted despite the reductions in poverty rates and the positive effects of government aid described in the previous paragraphs. The massive asset losses, mainly land, and the difficulty of fully recovering from income losses partially drive this vulnerability. Although land restitution and indemnities sought to legally recognize the suffering and damages brought about by forced displacement, the design and the implementation of both provisions of the Victim’s Law are inspired by development programmes and are, thus, dubbed transformative reparations (Guarin et al., 2021; Vallejo, 2021).

An evaluation by Guarin et al. (2021) finds that indemnities, indeed, significantly improve the economic and social conditions of victims, who are mostly IDPs. Indemnities, a wealth transfer equivalent on average to 3.3 times the income of victims, expand households’ permanent income. These households are, thus, better placed to search for better income opportunities, rely more on credit markets, accumulate assets and durable goods, and invest in human capital (Guarin et al. 2021). The causal impact of indemnities on present income is sizeable. The income from indemnities brings a respite to beneficiary households, allowing them to engage in a lengthier and more effective job search or to invest in their education. Victims that received indemnities are more likely to switch from higher-risk and low-wage jobs to lower-risk and high-wage jobs or to start new businesses. Future income is also likely to increase. Investment in education is higher. Its members enrol more in college, their drop-out rates from college are lower, and there is a higher probability that they transfer from technical to college education.

The effect of reparation measures may go beyond the impacts on economic conditions. In fact, the main purpose of these measures is to contribute to the healing process of victims. Bogliacino et al. (2021) study whether being compensated through land restitution increases interpersonal trust and trustworthiness of IDPs. Using an experimental trust game, they find a strong association between participating in the land restitution programme and greater trustworthiness.

VI. Discussion

The experience of forced migration in Colombia is sobering. The flows of internally displaced persons have been a constant in the country’s history, decreasing when violence subsides and intensifying when violence resumes. The country has put in place institutions, learned how to address the needs of IDPs, and implemented ambitious policies to redress the damages of forced displacement, even while not being able to control the violence that causes it. The efforts of the government have gradually become more effective. However, poverty across the IDP population is pervasive after decades of being displaced. Ending the years of conflict and violence is the best and only option to prevent more forced displacement and its consequences.

The 24-year process in Colombia provides several lessons. The following are particularly salient. The transition from humanitarian aid to development aid is difficult. Forced displacement is a multidimensional shock. IDPs migrate, quickly losing their support networks, productive assets, and sources of income. Their absorption by labour markets is slow and usually in the informal sector with no social protections. Most are victims of violence, which has a profoundly negative impact on their mental health. The transition from humanitarian aid to development aid for helping IDPs resume their economic activities has proven difficult. The latter is, however, important to prevent the persistence of the negative legacies of forced migration, as the negative effects may be passed on to subsequent generations of IDPs (Ibáñez, 2008).

The evidence on the consequences of forced migration in Colombia is compelling: IDPs suffer an erosion of their asset base, broadly defined, which may push them into poverty traps. Policies to compensate for the negative shock of displacement need to address in tandem the erosion of productive, physical, human, social, and psychological assets. How to address multiple and simultaneous asset losses simultaneously is not trivial. Studies to understand the complementarity and substitution across the several policies to address the needs of IDPs are crucial to adjust the current policies.

Overly ambitious policies may hamper the capacity of the state to achieve the final goal. The Colombian state has designed two progressive and ambitious laws to protect and assist IDPs. Although the state has gradually strengthened its institutional and fiscal capacity to implement these policies, there is great uncertainty about whether the final goal will be achieved. The current law covers many persons with a broad set of policies, and displacement persists. The difficulty of fulfilling the expectations of the Victim’s Law may hamper the credibility of the state and frustrate victims even more. Policies to prevent additional displacement are paramount, not only to protect the lives of millions of civilians but also to stop the growth of the number of IDPs. Defining reachable criteria for the cessation of the creation of IDPs may also contribute to this goal.

The creation of the State Registry for Displaced Population was a fundamental instrument for designing and implementing the IDP policy. The registry was a point of entry to rightfully identify the displaced population, estimate the support required to assist them, design special programmes and interventions, and provide timely information to other institutions. This strengthened the institutional capacity of the government.

Last, and very importantly, IDP policies are not implemented in a vacuum. Politics play a role. How to address the needs of victims of conflict and whether these victims should be compensated is a political decision. In the Colombian case, the IDP policy was discussed amid a protracted conflict in which the political shift required to engage in transitional justice had not yet taken place (Summers, 2012). Moreover, land restitution implies a distribution of economic and political power in the long term (García-Godos and Wiig, 2018). Research and technocratic actors supported the claims to consider IDPs as victims and to design a special policy for them, yet the final decision was in the hands of political actors who often disregarded the evidence. However, the enactment of a law to protect the IDP population allowed other branches of government—namely, the judicial branch—to weigh in, thus ensuring the continuity of a state policy beyond the political preferences of a particular government.

We are grateful to the editors Simon Quinn and Isabel Ruiz, an anonymous referee, Romuald Meango, and seminar participants of the Oxford Review of Economic Policy ‘Forced Migration’ seminar for useful comments and suggestions. All errors are our own.

Footnotes

Under UNHCR or UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) mandate.

Unlike refugees and asylum seekers, IDPs do not cross international borders but rather are forced to migrate within their own countries (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2021).