-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jonathan Portes, Immigration and the UK economy after Brexit, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Volume 38, Issue 1, Spring 2022, Pages 82–96, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grab045

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract:

I review trends in migration to the UK since the Brexit referendum, examining first the sharp fall in net migration from the EU that resulted, and then the recent more dramatic exodus of foreign-born residents during the covid-19 pandemic. I describe the new post-Brexit system, and review studies which attempt to estimate both the impact on future migration flows and on GDP and GDP per capita. Finally, I discuss the wider economic impact of the new system and some of the policy implications.

I. Introduction

Immigration was central to the politics of Brexit, but was peripheral in the pre-referendum discussion of its economic consequences (Forte and Portes, 2017a). Indeed, both before and in the immediate aftermath of the referendum, the UK’s choice was often framed as a trade-off between the economic costs of increasing trade frictions between the UK and EU on the one hand, and the political benefits of ending free movement and restoring ‘control’ over immigration on the other (UK in a Changing Europe, 2016).

Since the referendum, this has reversed—immigration has become a much less salient political issue, and public attitudes towards immigration have become more positive (Runge, 2019). However, its economic significance has become more apparent, first as migration flows from the EU fell sharply and then, in the past year, as the Covid-19 pandemic has led to very large net outflows.

This paper discusses migration trends since the referendum, revisiting my earlier estimates (Forte and Portes, 2017a), and examining developments during the pandemic. It then analyses the post-Brexit migration policy introduced in January 2021, reviews existing estimates of the likely economic impacts, discusses labour market developments during the post-pandemic recovery and beyond, and considers some of the resulting policy implications.

II. Migration trends since the referendum

Proponents of Brexit often argued that it would merely accelerate an inevitable and desirable reorientation of UK trade away from Europe and towards faster-growing overseas markets. And it is true that, over the last two decades, the UK has become somewhat less integrated with the EU in trade terms; trade with EU members now accounts for just under half of total UK trade. By contrast, even after the departure of the UK, only Ireland and Cyprus will be member states that trade more outside the EU than within (Eurostat, 2021a).

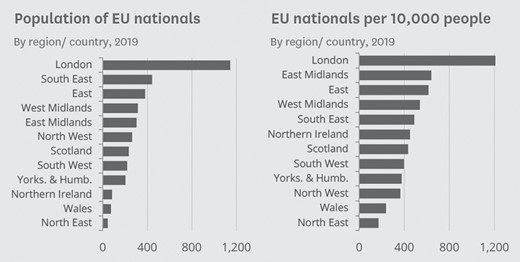

But pre-referendum trends in migration were very different. After the expansion of the EU in 2004 and 2011, the movement of people between the UK and the rest of the EU grew dramatically. Over the same 20-year period, official statistics suggest that the number of UK residents born in an EU member state more than doubled to over 3.6m (just over 5 per cent); as noted below, this is almost certainly a significant underestimate. About one in five EU citizens who have migrated within the EU live in the UK (Office for National Statistics, 2019), with particular concentrations in London (as with other migrant communities) and the east of England/East Midlands (see Figure 1).

EU nationals resident in the UK, by region.Source: Sturge (2021).

These statistics reflect several factors: the UK’s decision to immediately open its labour market to new member states in 2004; its relatively flexible and dynamic labour market (particularly after the eurozone crisis); and the appeal of London, the status of English as the world language, and the UK’s world-class universities. While movement the other way has not expanded as fast, about a million Britons—slightly under 2 per cent of the population—now live in EU member states (Eurostat, 2021b).

In June 2016, when the referendum took place, net migration to the UK reached an all-time record of 333,000. This included net migration of more than 200,000 from elsewhere in the EU, also a record. Immediately after the Brexit vote, I argued (Portes, 2016) that a significant fall was likely for several reasons.

— even before the referendum, employment growth in the UK had slowed, while unemployment was falling elsewhere in the EU;

— the referendum result was likely to make this fall much sharper, partly through the overall economic impact of Brexit on growth, output, and employment, and partly because migration from some EU countries appears to respond to exchange rate changes, with a fall in the pound making the UK less attractive as a destination country;

— legal and psychological factors, relating to the uncertainty about the future rights that EU citizens currently resident might enjoy, and the more general political and social climate, with the UK no longer seen as a hospitable destination for EU migrants.

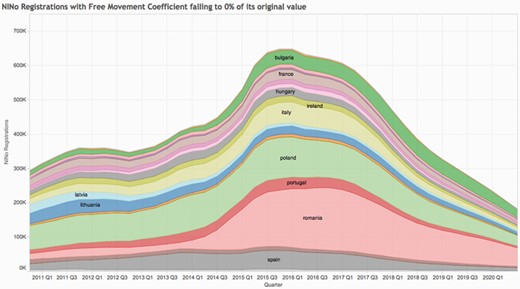

In our paper for the Oxford Review’s first special issue on Brexit, published in January 2017, Giuseppe Forte and I attempted to forecast the evolution of migration flows between the referendum and 2020 (Forte and Portes, 2017a). We used a modelling approach (set out in Forte and Portes, 2017b) that estimates the economic determinants of migration to the UK from the largest source countries for economic migration, as proxied by quarterly National Insurance number (NINo) registrations.

Forecast evolution of migration flows to the UK.Source: Forte and Portes (2017a).

We translated our forecasts for NINo registrations into net migration, predicting that net EU migration could fall by up to 91,000 on the central scenario, and up to 150,000 on a more extreme scenario, over the period between 2016 and 2020 (see Figure 2).

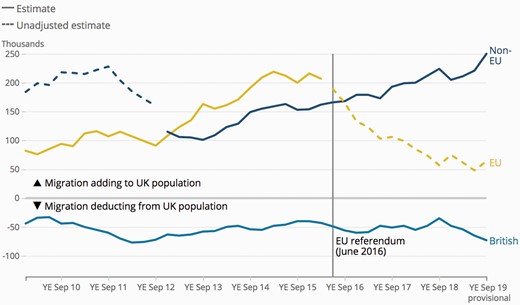

These forecasts have proved broadly accurate. As Figure 3—from the last set of migration statistics published in the UK, before the pandemic made collecting them impossible—shows, net EU migration did indeed fall by slightly more than 150,000 by the end of 2019. It is difficult to disentangle the relative impact of the factors listed above: the pound did fall sharply, reducing the relative value of wages in the UK compared to that in source countries, but the UK labour market remained resilient between the referendum and the onset of the Covid-19 crisis, and overall economic conditions remained relatively favourable. It does appear that the psychological impact of Brexit on past and prospective migrants from elsewhere in the EU was considerable.

Net migration to the UK by citizenship.Source: Office for National Statistics.

At the same time, there was also a significant rise in non-EU migration. This reflected in part labour market pressures, with the fall in EU work-related migration leading to shortages in some sectors and occupations, which may in part (especially in the health sector) have been filled by non-EU migrants. This substitution was facilitated by government policy, with the cap on Tier 2 visas for non-EU migrants (that is, relatively skilled or highly paid workers) being relaxed, particularly for those coming to work in the NHS, in late 2018, when it became apparent that enforcing the existing cap would further aggravate existing recruitment issues. While this represented a relatively minor policy change, it marked the end of the Theresa May era in immigration policy, during which the overriding objective had been to reduce numbers.

Recently published Office for National Statistics analysis (Office for National Statistics, 2021) suggests that EU migration was significantly underestimated, and non-EU migration overestimated, throughout the period discussed above; indeed, the peak in net EU migration in 2016 may have been as high as 280,000. Over the entire 2012–20 period, the analysis suggests net EU migration of 800,000 more than the originally published estimates.

Consistent with this, the number of applications to the EU Settlement Scheme, which offers EU nationals resident in the UK before 1 January 2021 the opportunity to register for permanent residence, has significantly exceeded expectations. While the Home Office estimated—based on population statistics—that 3.5–4.1m people would be eligible to apply to the scheme, approximately 5m people (of whom 4.7m are EU or EEA nationals) have been granted settled or pre-settled status, with significant numbers of additional applications still being received.

While these new data do not change the broad picture or key trends described above—it is still the case that EU migration has fallen very sharply since the referendum, with non-EU migration increasing somewhat—it is also clear that the importance of EU nationals to the UK economy and labour market was and is even larger than suggested.

III. Developments during the pandemic

So, at the beginning of 2020, net migration to the UK remained high, although the post-2004 trend for EU migration to partially displace non-EU migration had in part been reversed. The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, led to a very sharp reversal of migration flows.

While, as noted above, the International Passenger Survey, which forms the basis for migration statistics, has been suspended, the Labour Force Survey provides data on non-UK-born people resident in the UK. The published data initially suggested a fall of approximately a million between the last quarter of 2019 and the last quarter of 2020, with most of that occurring within a few months of the onset of the pandemic, and driven by a fall in the number of EU-origin workers.

There is considerable controversy over the reliability of these estimates, because of the difficulties of conducting surveys during the pandemic, which make it even harder than usual to contact people who have not been here very long, and who live in private rented accommodation (as many recent migrants do). O’Connor and Portes (2021) and Sumption (2021) both reanalyse the underlying data, and come to somewhat different conclusions. However, there is little doubt that there has indeed been a large outflow. As I put it (Portes, 2021):

And while collecting and interpreting the data during the pandemic is extremely challenging—that number could be out by hundreds of thousands in either direction—there is no doubt that this reversal in migration trends has been large, real and abrupt. Neither Theresa May’s hostile environment nor Brexit came close to meeting David Cameron’s foolish ‘tens of thousands’ target for net migration; but Covid-19 has done so, and then some.

Given the nature of the pandemic and its economic and social impacts, this is not surprising. Migrants, especially from Europe, are disproportionately likely to be employed in the hospitality sector, and other service sectors that require face-to-face contact, so are more likely to have been furloughed or lose their jobs. With many universities moving wholly or largely to on-line teaching, many foreign students may have decided not to come to the UK or to return here.

But most of all, the UK (alongside a few other western European countries such as Spain and Italy), performed relatively badly in both economic and health terms during the first wave of the pandemic. For many migrants, especially those from eastern, central, and south-eastern Europe, and especially those who have arrived recently or have family back home, the choice would have been to stay here, with no job, less or no money, and pay for relatively expensive rented accommodation—or return home to family, with lower costs and most likely less risk of catching Covid.

IV. The future migration system

It is against this background that the UK is introducing the new, post-Brexit immigration system. As set out in Portes (2020), the new system was shaped by two broad forces.

First, the government’s commitment to ending free movement and to an ‘Australian-style points system’ which would treat EU and non-EU migrants similarly. Many policy-makers believed it would be clearly in the UK’s economic interests after Brexit to retain most or all of the benefits of membership of the Single Market—either by maintaining membership of the European Economic Area (like Norway) or via a series of bilateral agreements (like Switzerland).

But the government, first under Theresa May and then Boris Johnson, rejected such an approach, making clear ‘we are not leaving the European Union only to give up control of immigration’. This position meant in turn that the EU never seriously considered what, if any, compromises it could make on free movement. Instead, the EU underlined the fact that free movement was an integral part of Single Market membership. As a result, the UK–EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement contains very limited provisions on labour mobility.

However, at the same time, there were significant shifts in both public opinion and government policy towards immigration in general. Opinion polls suggest that voters have simultaneously becoming both much less concerned about immigration and much more positive about its impacts. Moreover, the replacement of Theresa May, who had been a notably restrictionist Home Secretary, with Boris Johnson, who had adopted relatively liberal positions on immigration during his tenure as Mayor of London, signalled a change in the relative priorities within government attached to the economic benefits of immigration compared to the political need to be seen to be controlling it.

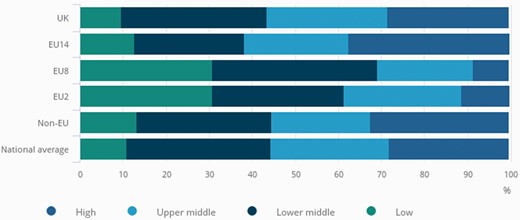

The policy intent of the new system is therefore less about reducing migration, and more about making it both more diverse (in a geographic sense) and more selective (in relation to the skill level of workers) than the existing bifurcated scheme. The potential for these shifts can be seen in Figure 4, which shows that non-EU migrants who, if entering for work purposes (although many do not), have to meet a relatively restrictive salary threshold, work in occupations that are generally higher skilled than the UK average, while those from the EU8 (the Visegrad states and the Baltic States) and EU2 countries (Bulgaria and Romania) are much more likely to work in low-skill occupations.

Distribution of workers in each nationality group by skill level of occupation (UK, 2016)Source: Office for National Statistics, 2017.

The results can be seen in the new ‘points-based system’ that was introduced on 1 January 2021. Free movement ended on 31 December and the new system applies to all those moving to the UK to work, apart from Irish citizens. EU (and EEA/Swiss) nationals already resident in the UK are able to apply to remain indefinitely under the ‘settled status’ scheme, and most have already done so. The key provisions of the new system are that:

— New migrants should be coming to work in a job paying more than £25,600 or the lower quartile of the average salary, whichever is higher, and in an occupation requiring skills equivalent to at least A-levels (‘RQF3’).

— There is a lower initial threshold for new entrants and for those in shortage occupations, meaning that for some occupations the salary threshold may be as low as about £20,000.

— There is also a lower threshold for those with PhDs, especially in STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics).

— For the National Health Service and education sectors, there is in effect no salary threshold. If the job is at an appropriate skill level (again, roughly the equivalent of A-levels, and including not just nurses and doctors but radiographers and technicians), then paying the appropriate salary according to existing national pay scales is sufficient.

— There is an expanded Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme, but no other sectoral schemes for workers who do not meet the skill threshold, and in particular not for the social care sector.

The new system represents a very significant tightening of controls on EU migration compared to free movement. Migrants coming to work in lower-skilled and paid occupations are in principle no longer able to gain entry. Even those who do qualify need their prospective employers to apply on their behalf, have to pay significant fees, and, as has been the case for non-EU migrants, have significantly fewer rights, for example in respect of access to the benefit system.

However, compared to the current system, the new proposals represent a considerable liberalization for non-EU migrants, with lower salary and skill thresholds, and no overall cap on numbers. Approximately 68 per cent of UK employees work in occupations requiring RQF3 level skills or above; given the requirement for new migrants to be paid at or above the lower quartile of earnings for that occupation, that implies about half of all full-time jobs in principle qualify an applicant for a visa under the new system.1 This represents a very substantial increase—perhaps a doubling compared to the previous system for non-EU nationals, who were also, for most of the 2012–19 period, subject to an overall quota and a resident labour market test.

So it is not the case that the new system represents an unequivocal tightening of immigration controls; rather, it rebalances the system from one which was essentially laissez-faire for Europeans, while quite restrictionist for non-Europeans, to a uniform system that, on paper at least, is expensive but has relatively simple and transparent criteria, and covers up to half the UK labour market. As Alan Manning, the former Chair of the Migration Advisory Committee, put it: ‘The UK has gone for reducing aspects of migration bureaucracy—labour market tests, quotas—that are common elsewhere. One way to see it is that it’s got more in the way of tariff barriers than non-tariff barriers.’

V. The economic impacts of the new system

While an extensive literature has developed around the economic impacts of Brexit, most studies focus on trade-related impacts, and either ignore migration entirely, or adopt very broad-brush assumptions. See Office of Budget Responsibility (2018) for a review. However, a number of studies do attempt both to model changes to future migration flows and assess the economic impacts of changes to the post-Brexit system.

(i) The UK government’s analysis of the impact of future Brexit scenarios (HM Government, 2018) modelled the impact if net migration from the EEA fell to zero. The impact was estimated at a reduction of GDP of 1.8 per cent over 15 years, and a reduction of 0.6 per cent in per capita GDP.

(ii) Modelling conducted by the Home Office (Home Office, 2018) forecast a reduction in the number of EU workers in the UK by between 200,000 and 400,000 by 2025, which would reduce GDP by 0.4 to 0.9 per cent, and GDP per capita by 0.1 to 0.2 per cent.

(iii) Both these estimates assumed no change in non-EU migration. Forte and Portes (2019) was the first published analysis to incorporate possible increases in non-EU migration. They estimated a fall in about 600,000 in EU migration over 10 years, partly offset by an increase in non-EU migration of about 50,000, with the latter being higher skilled and higher paid. The net effect was a GDP reduction of 1.4 to 1.9 per cent and a GDP per capita reduction of 0.4 to 0.9 per cent.

(iv) All these estimates assumed a salary threshold of £30,000. However, in subsequent work (UK in A Changing Europe, 2019), Portes elaborated these estimates to include a more liberal approach, broadly reflecting the system ultimately adopted. This estimated a somewhat smaller fall in EU migration (about 500,000) and a considerably larger rise in non-EU migration (about 150,000), and consequently a much smaller reduction in GDP (0.2 to 0.6 per cent) and a small rise (0.2 to 0.6 per cent) in GDP per capita.

(v) The independent Migration Advisory Committee’s assessment of the points-based system (Migration Advisory Committee, 2020) does not attempt to model future migration flows. However, it does model a retrospective counterfactual—what would have happened if the new system had been in place in respect of EEA citizens from 2004 to the present. It finds that GDP would have been 2.8 per cent lower, but GDP per capita would have been 0.4 per cent higher.

(vi) Finally, the Home Office impact assessment of the new system (Home Office, 2020a) projects (consistent with (ii) above) a reduction of 200–400,000 in net EU migration over the period to 2025, partly offset by an increase of 40–100,000 in non-EU migration. They do not estimate the GDP impact, but it appears to suggest a small reduction in GDP (below 0.5 per cent) and little impact on GDP per capita.

These studies use a variety of modelling approaches, but typically make broad-brush estimates of the impact of the new system on migration flows at various skill levels, and hence on both the size and skill levels of the resident labour force; some also incorporate indirect impacts, e.g. through the impact on productivity. Nevertheless, while they are not strictly comparable, there is a considerable degree of consistency in the analyses described above. The new system is likely to lead to a reduction in EU migration, perhaps of the order of 60,000 a year, partly offset by a smaller increase in non-EU migration. This will result in a fall in GDP, but the more liberal approach to non-EU migration means that the overall impacts on GDP per capita are likely to be small.

An additional dimension of uncertainty results from the government’s decision to offer entry—and ultimately a path to citizenship—to the almost 3m British National Overseas passport-holders from Hong Kong, and their dependants. The Home Office’s central forecast of the resulting migration flows (Home Office, 2020b) is about 300,000 over 5 years, but its low and high estimates are 10,000 and 1,000,000, respectively. Actual flows will be driven not by UK policy but by developments in Hong Kong, and in particular by whether political tensions escalate further and China intensifies its crackdown on pro-democracy activists. Nevertheless, if hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong residents do come to the UK, the potential impacts could be transformative.

As with the new system, the Home Office has not modelled the impact on GDP or GDP per capita, but its analysis implies a significant and positive impact. These estimates may be conservative: they take account of the fact that potential migrants from Hong Kong are likely to be of working age, but not that they are also likely to be relatively highly educated, with marketable skills, and will generally speak English. Other evidence (Anders et al., 2021) suggests that the most obviously analogous historical experience of a sudden, large refugee flow to the UK—the East African Asians in the late 1960s and early 1970s—had generally positive outcomes.

There are, however, also risks: while the economic impacts of the unexpected surge in EU migration after 2004 were broadly positive, the perceived impacts at a local level, on the demand for education and health services, were less so. At least in part, this resulted from a failure to plan and to redirect the extra tax revenue resulting from immigration to the provision of public services (see the discussion in Portes (2019)). If the number of Hong Kong migrants exceeds expectations, the economic impacts will almost certainly be positive; but if the government fails to provide accordingly, the political and social impacts may not be.

VI. Wider economic impacts

The analyses discussed above (with the partial exception of Forte and Portes (2019)) largely ignore the indirect impacts of migration on productivity—that is, they incorporate direct impacts, using salary as a proxy for productivity, but not the impact of migration on the productivity of other workers. Theoretically, these impacts are ambiguous: are immigrants complements to natives, and do they increase incentives for natives to improve their skills; or do they reduce the incentive for firms to invest in either physical or human capital? (See Campo et al. (2018) for a discussion.)

However, there is an increasing body of evidence that overall the impact is positive. In our paper for the Oxford Review’s special issue on Brexit in 2017 (Forte and Portes, 2017a), we drew on two papers that used cross-country evidence to estimate such impacts (Boubtane et al., 2015; Jaumotte et al., 2016) and incorporated their estimates into our assessment of the impacts of post-Brexit changes to immigration. This led to much larger negative impacts, of between 3 and 8 per cent to GDP, and 1–5 per cent to per capita GDP. We were, however, careful to note that these were at best broad-brush scenarios, and that direct empirical evidence for the UK was sparse (Portes, 2018).

Subsequent to that, the Migration Advisory Committee commissioned three papers examining the evidence. Campo et al. (2018) exploit geographical variation in the migrant share of the workforce, using an instrumental variable approach, to estimate the impact of immigration on productivity. It finds that a 1 percentage point increase in the share of immigrants within a UK local authority is associated with an almost 3 percentage point increase in productivity. Costas-Fernández (2018), by contrast, assumes a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) production function, and incorporates new estimates of the capital stock at a regional and sector level. The study finds that migrants in both high- and low-skilled occupations are, at the margin, more productive than their UK-born counterparts, with the central estimates suggesting that the marginal migrant is around 2.5 times as productive as a UK-born worker. Finally, Smith (2018) also looks at a region-sector level, but the key dependent variable is total factor productivity (TFP) rather than labour productivity; she also uses firm-level data and imposes less structure on the production function. The central estimate is that a 1 percentage point increase in the migrant share results in a 1.6 per cent increase in TFP.

The striking element of all these results—found by different papers using different methodologies and different data—is not just that immigration appears to have a positive impact on productivity growth, but that this impact is large; indeed, as the Migration Advisory Committee (2018) says, arguably ‘implausibly large’. Nevertheless, the results are consistent with the cross-country evidence.

We are therefore left with a dilemma. Estimates of the mechanical impact of migration on the labour force, ignoring wider productivity impacts, suggest that the new system will reduce migration flows, but with little impact on GDP per capita. However, as the Migration Advisory Committee (2020) puts it: ‘If there is an impact on productivity this effect is very important and likely to out-weigh many or most other impacts.’

Uncertainty about the productivity impacts of the new system also raises the issue of how it aligns with the government’s wider economic strategy. From an economic perspective, there are clear advantages to the basic design proposed by the Migration Advisory Committee and endorsed by the government. If the objective is to maximize the economic benefits of immigration, then a purely market solution would imply open borders. However, this is clearly not feasible for political, cultural, and social reasons.

Given this constraint, a salary threshold is a clear second-best mechanism, at least within the simple framework used by the models summarized above, because it puts the market, rather than bureaucrats or politicians, in charge of the selection process, and selects those with the highest direct impact on productivity, as measured by salary. This avoids having to pick winners, engage in central planning, or allow the loudest business voices to determine which occupations and sectors qualify and which do not. Not surprisingly, the Migration Advisory Committee—dominated by labour market economists—went down this route. See Sumption (2022) for a more detailed discussion.

VII. Wages

However, even if the macroeconomic impacts overall are uncertain, there may be distributional ones. It was frequently argued that free movement, by facilitating the migration of European nationals to low-paid jobs in the UK, reduced wages for low-paid British workers; and that ending it would therefore boost wages (Portes, 2016).

In fact, the empirical evidence suggests that recent migration has had little or no impact on wages overall, but possibly some, small, negative impact on low-skilled workers; and that other factors, positive and negative (technological change, policies on tax credits, the National Minimum Wage) were far more important (see Portes, 2018, for a summary of this literature).

Bringing this evidence together with the wider literature on migration and productivity discussed above, Forte and Portes (2017a) argued that any positive impact on the wages of lower-paid workers resulting from the end of free movement might well be more than outweighed—even for low-paid workers themselves—by the negative macroeconomic impacts on growth, productivity, and hence real wages (although that analysis ignored any positive impact from liberalizing non-EU migration).

The ending of free movement will provide further evidence on these issues. Since the ending of almost all Covid-related restrictions, there have been consistent reports of staff and skill shortages as businesses reopen. Given that, as discussed above, there is clear evidence that there was indeed a large exodus (even if we remain uncertain as to its magnitude) of EU-origin workers during the pandemic, it seems plausible that the two are connected.

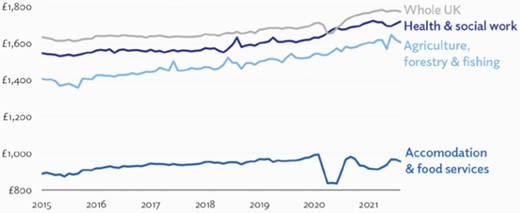

The hospitality sector, in particular, has been hit by successive shocks to labour demand (driven first by the imposition of restrictions, and now by their removal) and to labour supply (resulting primarily from emigration, but also perhaps from some workers leaving the sector permanently). It is therefore not surprising that this should result in substantial labour market ‘mismatches’. However, as yet, it is too early to draw firm conclusions about the medium- to longer-term impacts. Despite the recent recovery, real wages in the accommodation and food services sector are still below their pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 5).

Median wages by sector (real terms).Source: UK in a Changing Europe (2021).

More broadly, current conditions in the immediate aftermath of the reopening of the economy will, almost by definition, be temporary and transitory. However, over the longer term, it is certainly possible that the pandemic, the departure of many EU workers last year, and the introduction of the post-Brexit migration system will have lasting impacts on the labour market; these are not just transitory impacts but, potentially, big long-term shocks.

The pandemic could affect both labour demand and labour supply. If there is a big shift towards working from home some or all of the time for office workers, that will have an impact on the demand for many businesses in the hospitality sector and other customer-facing service businesses in city centres; these are in turn big employers of migrants. And to the extent that those who left the UK do not return, and the new migration system affects the ability or willingness of new migrants to come here, that will reduce labour supply.

If labour supply is, indeed, reduced more than demand, then there is a variety of possible responses: higher employment for UK-origin workers, higher wages (which in turn would likely mean higher prices), higher productivity, or lower output/fewer businesses.

The empirical evidence suggests that the main impact will be through lower overall employment and output; that there will be no significant increase in employment for the UK-born; there will be some, but probably rather small, increase in relative real wages for workers in the most affected sectors (offset by an even smaller fall in relative real wages for other workers who consume the outputs of those sectors); and that there will be no offsetting increase in productivity (indeed, as discussed above, productivity may even fall). But we will need to wait and see.

VIII. Relationship with the government’s broader agenda

As discussed above—and as seen in the government’s response to business concern about recent labour shortages—the new policy places great faith in the UK labour market to adjust smoothly to the new system. The trouble with such a policy is that it sits rather oddly with the government’s wider economic strategy, which is very far from a purist free-market approach. Rather, it combines at least three strands: first, a ‘levelling-up’ agenda, which prioritizes the need to address regional and spatial inequalities, particularly in those areas which felt that they were ‘left behind’ by globalization and disadvantaged, directly or indirectly by immigration. Second, a view that the UK’s economic future will be driven by its success in taking advantages of the commercial opportunities growing out of science and technology, including ‘big data’ and artificial intelligence. And third, the commitment to ‘net zero’, which will require substantial government intervention across key sectors of the economy.

But all of these strands require active policy, including an element of planning and ‘picking winners’—a ‘developmental state’ rather than a night-watchman state. Neither is necessarily compatible with an immigration system that is deliberately neutral between sectors and occupations; and which, because of its reliance on salary as the primary criterion, is, by definition, likely to further advantage those sectors and regions where salaries are already highest and that therefore already benefit the most (notably, the financial sector, and London and the South-east). Indeed, it is possible that the new system will exacerbate the existing imbalances in where migrants locate within the UK.

The pandemic has also highlighted the fact that economic value, as measured by market wages, is not necessarily an accurate reflection of wider social value. Care workers, bus drivers, and supermarket staff all fulfil essential functions, and it is far from obvious that there will be public support for an immigration system that excludes them all in favour of relatively junior bankers. Indeed, public opinion has always been nuanced about the appropriate definition of ‘skills’ for immigration purposes (Rutter and Carter, 2018). Equally, moves towards net zero (particularly increasing the energy efficiency of the housing stock) are likely to require construction-related skills that in recent years have often been supplied by migrant workers, often self-employed (who are not in general eligible to migrate under the new system).

So to sum up, as Sophia Wolfers of London First put it (Financial Times, 2020), are the government’s proposals ‘based on what is rapidly becoming old thinking’? Yes and no. The government can, should it wish, take the opportunity to address the criticisms of its approach and ensure that the new system supports its wider economic strategy.

Some steps would be relatively easy to take and do not require system change. The government has already partially loosened the restrictive rules on settlement which discouraged people who have contributed to the UK for years from making it their permanent home. Further changes could include a reduction in some migration fees, particularly for visa extensions and renewals, settlement, and citizenship; an end to the double taxation of the so-called NHS surcharge, which imposes an arbitrary extra tax on immigrants, including NHS workers, who already pay the same taxes as other residents; and more broadly a more efficient, flexible, and humane approach to the operation and enforcement of the immigration system. All this would help ensure the UK does not lose ‘key workers’ and others who are essential to an economic revival after Covid-19.

More broadly, the government should step back and think again about the alignment of the immigration system with its wider objectives. Which sectors are the priority, from social care to science, and does or should a salary-based scheme take account of that? What regional or national flexibility would spread the benefits of migration outside London, and who decides? Is there a case for varying the criteria so as to encourage skilled migrants to locate in localities which arguably ‘need’ them more than London? How do you adjust the system—which, inevitably, will be very far from perfect initially—quickly and flexibly without falling into the central planning trap? In an uncertain economic and political environment after Brexit and Covid-19, joining up migration policy with its broader economic strategy will be a major policy challenge for the UK—but also, with new-found policy flexibility and unprecedented political space, a major opportunity.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Jonathan Portes’ Senior Fellowship of the ‘UK in a Changing Europe’ programme, financed by the Economic and Social Research Council, grant number ES/N003667/1. I am grateful for comments from Colin Mayer, Madeleine Sumption, Christopher Adam, and participants at a seminar on Brexit convened by the Oxford Review of Economic Policy for this special issue.

Footnotes

This is an approximation. As noted above, some jobs not covered by this qualify in the health and education sectors, and salary requirements are lower for new entrants and PhDs; on the other hand, for some jobs the £25,600 threshold, which also applies, is higher than the lower quartile of earnings.

References

— (

— — (

— — (

— (

— (

— (

— (

— (

— (

— (

— (

— (

Runge, J. (

— (

— (

— (