-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shanti Narayanasamy, Adam R Williams, Wiley A Schell, Rebekah W Moehring, Barbara D Alexander, Thuy Le, Ramesh A Bharadwaj, Michelle McGauvran, Jacob N Schroder, John R Perfect, Curvularia alcornii Aortic Pseudoaneurysm Following Aortic Valve Replacement: Case Report and Review of the Literature, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 8, Issue 11, November 2021, ofab536, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofab536

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We report the first case of Curvularia alcornii aortic pseudoaneurysm following bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement in an immunocompetent host. Infection was complicated by septic emboli to multiple organs. Despite aggressive surgical intervention and antifungal therapy, infection progressed. We review the literature on invasive Curvularia infection to inform diagnosis and management.

Curvularia species are dematiaceous, saprophytic molds found ubiquitously in soil, which rarely cause disease in animals and humans [1]. The earliest report of phaeohyphomycosis due to Curvularia was a patient with black-grain mycetoma in Senegal in 1959 [2]. The clinical spectrum of Curvularia infections in humans is broad, ranging from allergic bronchopulmonary disease and localized infections involving the skin, eyes, and sinuses, to invasive infections including brain abscess, endocarditis, and peritonitis [3–5]. We report the first case of Curvularia alcornii aortic pseudoaneurysm following aortic valve replacement in an immunocompetent host. As Curvularia endocarditis is rare, we review the literature of invasive Curvularia infections to inform diagnosis and management.

CASE REPORT

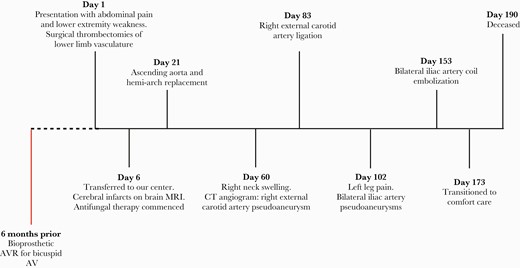

A 53-year-old man with hypertension and hypercholesterolemia underwent bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement for bicuspid aortic valve (Figure 1). The procedure was uncomplicated. Six months later, he presented to his local hospital with acute abdominal pain and lower extremity pain and weakness. He reported a 4-month history of right neck pain, and a 2-month history of low-grade fevers, sweats, malaise, and dysphagia. He was born in Mexico and had migrated to the United States 14 years prior. He lived in an urban area of South Carolina and worked as a landscaper.

Timeline of the patient’s clinical progress and major surgical interventions. Abbreviations: AV, aortic valve; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

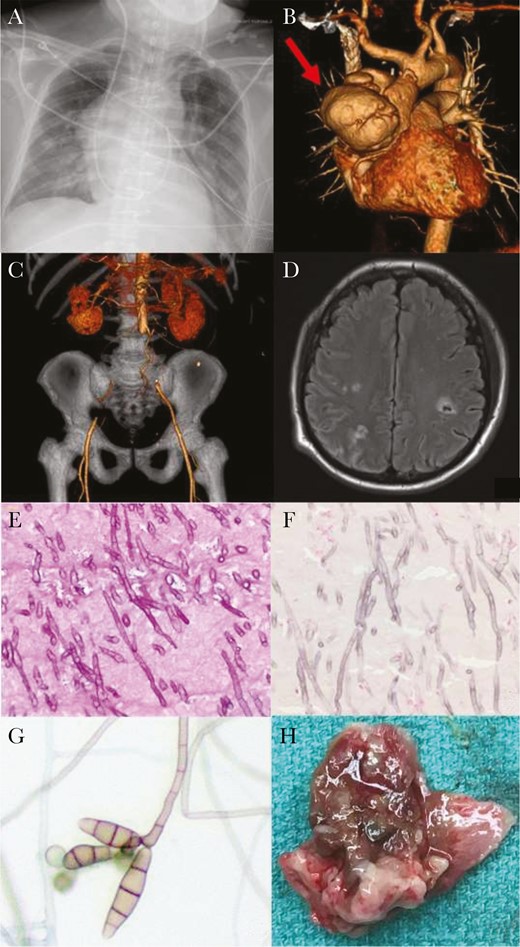

On admission examination, he was febrile, with bilateral cold lower extremities and absent femoral pulses. Chest radiograph (Figure 2A) and computed tomography (CT) angiogram demonstrated a large, multilobar, 8cm ×7.6cm ascending aortic pseudoaneurysm causing mass effect on the left atrium and superior vena cava (Figure 2B). He had multiple embolic occlusions of the aorta, renal arteries, superior mesenteric artery, hepatic artery, and splenic artery (Figure 2C). Transthoracic echocardiography showed a large ascending aortic pseudoaneurysm and a well-seated prosthetic aortic valve with no perivalvular regurgitation. He was commenced on intravenous vancomycin and cefepime.

Radiographic, histopathological, and microbiological results. A, Anteroposterior erect chest radiograph on presentation demonstrating large aortic aneurysm. B, Computed tomography (CT) angiogram reformats on presentation: red arrow indicating ascending aortic aneurysm. C, CT angiogram reformats on presentation: coronal view, demonstrating absence of blood flow through bilateral iliac arteries. D, Magnetic resonance imaging of the head demonstrating septic cerebral emboli. E, Periodic acid-Schiff stain of the aortic thrombus, 400×, showing narrow, septate fungal hyphae with acute angle branching. F, Fontana-Masson stain, 400×, demonstrating melanin uptake in the fungal cell wall. G, Lactophenol cotton blue stain of the Curvularia alcornii recovered in culture. H, Macroscopic “fungal ball” from ascending aorta.

Due to limb ischemia, he underwent emergency laparotomy for surgical thrombectomies of the superior mesenteric and aortoiliac arteries and bilateral lower limb fasciotomies. On day 6 following the operation, he transferred to Duke University Hospital for further management while critically ill on mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, and renal replacement therapy. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed multiple supra and infratentorial acute infarcts, and intraparenchymal and subarachnoid hemorrhages (Figure 2D). Histopathology from the previously excised thrombus showed extensive infiltrates with pigmented septate fungal hyphae (Figure 2E), and Fontana-Masson stain demonstrated melanin in the fungal cell wall (Figure 2F). Antibacterials were stopped; instead, we started broad-spectrum antifungal therapy: liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) 5mg/kg once daily, intravenous voriconazole (loading dose of 6mg/kg then 4mg/kg every 12 hours), and intravenous micafungin 150mg daily.

Bacterial and fungal blood cultures remained negative after 5 days of incubation, so we used a Karius test (Karius, Redwood City, California), a metagenomic next-generation sequencing test designed to detect circulating microbial cell-free DNA in plasma [6]. No pathogen was detected above the statistical threshold. However, the assay did detect Curvularia species below the statistical threshold. Fungal culture of the aortic thrombus grew black colonies after 10 days’ incubation. Microscopically, the pathogen had brown, narrow-angle branching, septate hyphae with sympodial growth and brown multiseptate conidia (Figure 2G), consistent with Curvularia species. The nucleotide sequence of the isolate for internal transcribed spacer 1, partial sequence; 5.8S ribosomal RNA gene, complete sequence; and internal transcribed spacer 2, partial sequence (GenBank accession number MT658129) was determined by the Duke Mycology Research Laboratory using previously described methodology [7].

On day 21 he underwent an ascending aorta and hemi-arch replacement graft and biological Bentall aortic root and valve replacement. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography showed a large mycotic aneurysm (8.8 cm×8cm) (see video in the Supplementary Materials) and fungal balls within it (Figure 2H). Fungal cultures of the intraoperative tissue revealed Curvularia alcornii. The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Fungus Testing Laboratory performed standardized susceptibility tests [8] with the following minimum inhibitory concentrations: amphotericin B, 0.06 µg/mL; voriconazole, 0.25 µg/mL; fluconazole, 8 µg/mL; itraconazole, ≤0.03 µg/mL; ketoconazole, 0.125 µg/mL.

He recovered well from the operation. On day 60, he noted right neck swelling and increased pulsatility. CT angiogram of the neck showed a right external carotid artery pseudoaneurysm. He underwent open right external carotid artery ligation on day 83. Cultures of the carotid artery were not sent; however, histopathology demonstrated septate hyphae. He completed 12 weeks of L-AmB and 2 weeks of micafungin and transitioned to suppressive oral voriconazole.

Shortly after discharge to a rehabilitation facility on day 102, he developed progressive left leg pain. He was readmitted with persistent left leg pain, numbness, and fever. Voriconazole level on admission was 4.0 µg/mL. Blood cultures were negative. CT angiography demonstrated bilateral iliac artery pseudoaneurysms with associated thrombus and suspicion for abscesses. Open surgery was deemed too high risk, so he underwent bilateral iliac artery coil embolization. L-AmB and micafungin were restarted, and given refractory disease despite adequate levels, voriconazole was changed to posaconazole. Despite these interventions, he developed further arterial pseudoaneurysms and emboli with persistent fever. He transitioned to comfort care and died 5 months after initial presentation.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

We performed an English-language literature review of invasive Curvularia infections between 1970 and June 2021. The PubMed database was searched for “Curvularia” in the title or abstract. Criteria for inclusion were (1) a clinical syndrome consistent with invasive infection and (2) microbiological recovery of Curvularia spp. Localized infections of the sinus, skin, or eye or catheter-associated infections were excluded, as were pediatric cases.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a mycotic aortic aneurysm caused by Curvularia alcornii and only the third reported case of cardiac infection caused by Curvularia species [9, 10]. All 3 cases were associated with aortic valve replacement and had several features in common: (1) aortic root involvement, (2) occurring within 6 months following aortic valve replacement, (3) did not originate from a cutaneous or sinopulmonary source, and (4) presented in an immunocompetent host.

Endocarditis due to phaeohyphomycosis is uncommon, accounting for just 13% (9/72) of invasive disease [4]. A 2002 review article on disseminated phaeohyphomycosis reported just 7% (5/72) of infections caused by Curvularia species [4]. Twenty cases of invasive Curvularia infection have been described in the literature including the present case (Table 1). The majority (16/20 [80%]) of invasive Curvularia infections occurred in men, mirroring the male predominance of disseminated phaeohyphomycosis (41/72 [57%]). Most (11/20 [55%]) patients with invasive infection were immunocompromised or had preexisting sinopulmonary disease. Mortality of invasive Curvularia was 45% (9/20), compared to 79% (57/72) for disseminated phaeohyphomycosis.

Cases of Invasive Curvularia Species Infection Reported in the Adult Literature (1970–June 2021)

| Reference . | Curvularia Species . | Patient Characteristics . | Presumed Source . | Site(s) of Disease . | Therapy . | Alive at Publication (Yes/No) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)/Sex . | Risk Factor(s) for Invasive Infection . | ||||||

| Current case | C alcornii | 53/M | None | Prosthetic material | PVE, aortic root, brain, spleen, kidneys, iliac arteries | AmB, vori, mica, posa, surgery | No |

| Rolfe et al, US, 2020 [7] | C lunata | 67/M | Lung transplant | Prosthetic material | Lungs, pleural space | AmB, surgery | No |

| Djenontin et al, Mali, 2020 [11] | C sp | 44/F | None | Traumatic inoculation following road accident | Native knee septic arthritis | AmB, posa, surgery | No |

| Gonzales Zamora et al, US, 2019 [12] | Curvularia sp | 42/F | Heart, kidney transplant | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | AmB, vori | No |

| Vasikasin et al, 2019, Thailand [13] | C tuberculata | 22/M | None | Cutaneous | Skin, lungs | AmB | Yes |

| Shrivastava et al, 2017, India [14] | C lunata | 48/M | None | Cutaneous | Epidural space | AmB, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Skovrlj et al, 2014, US [15] | Curvularia sp | 33/M | Marijuana use | Sino-pulmonary | Brainstem | AmB, 5-FC, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Gongidi et al, 2013, US [16] | Curvularia sp | 37/M | Steroids, marijuana use | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | “IV antifungals,” surgery | Yes |

| Gagdil et al, 2013, US [17] | Curvularia sp | 50/F | Sinus surgery | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | Vori, surgery | Yes |

| Gagdil et al, 2013, US [18] | C geniculata | 35/M | Plasma cell dyscrasia | Unknown | Brain | AmB, vori, surgery | No |

| Singh et al, 2008 [18]; Australia [19] | C lunata | 57/M | None | Sino-pulmonary | Sinus, brain | AmB, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Carter et al, 2004, US [20] | C lunata | 21/M | Marijuana use | Unknown | Brain | AmB, 5-FC | No |

| Tessari et al, 2003, Italy [21] | C lunata | 68/M | Heart transplant | Cutaneous | Skin, lungs, GI tract | AmB | No |

| Levi & Basgoz, 2000, US [22] | Curvularia sp | 56/M | Lung transplant | Prosthetic material | Lung, pleura, pericardium, sternal wound, thyroid | AmB, itra, 5-FC | No |

| Ebright et al, 1999, US [23] | C clavata | 46/F | Chronic sinusitis | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | AmB, itra, surgery | Yes |

| Bryan et al, 1993, US [9] | C lunata | 44/M | None | Unknown | PVE, aortic root | AmB, ket, terb, surgery | Yes |

| Pierce et al, 1986, US [24]; de la Monte & Hutchins, 1985, US [25] | C lunata | 42/M | T-cell deficiency | Unknown | Lung, brain | AmB, ket, mico, surgery | Yes |

| Rohwedder et al, 1979, US [26] | C lunata | 25/M | None | Cutaneous | Lung, lymph node, skin, muscle, brain, spine | AmB, mico, surgery | Yes |

| Harris & Downham, 1978, US [27] | Curvularia sp | 27/M | None | Cutaneous | Lung, spine | AmB, 5-FC, mico | Yes |

| Kaufman, 1971, US [10] | C geniculata | 41/M | None | Unknown | Aortic homograft, brain, spleen, kidney, thyroid | Surgery | No |

| Reference . | Curvularia Species . | Patient Characteristics . | Presumed Source . | Site(s) of Disease . | Therapy . | Alive at Publication (Yes/No) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)/Sex . | Risk Factor(s) for Invasive Infection . | ||||||

| Current case | C alcornii | 53/M | None | Prosthetic material | PVE, aortic root, brain, spleen, kidneys, iliac arteries | AmB, vori, mica, posa, surgery | No |

| Rolfe et al, US, 2020 [7] | C lunata | 67/M | Lung transplant | Prosthetic material | Lungs, pleural space | AmB, surgery | No |

| Djenontin et al, Mali, 2020 [11] | C sp | 44/F | None | Traumatic inoculation following road accident | Native knee septic arthritis | AmB, posa, surgery | No |

| Gonzales Zamora et al, US, 2019 [12] | Curvularia sp | 42/F | Heart, kidney transplant | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | AmB, vori | No |

| Vasikasin et al, 2019, Thailand [13] | C tuberculata | 22/M | None | Cutaneous | Skin, lungs | AmB | Yes |

| Shrivastava et al, 2017, India [14] | C lunata | 48/M | None | Cutaneous | Epidural space | AmB, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Skovrlj et al, 2014, US [15] | Curvularia sp | 33/M | Marijuana use | Sino-pulmonary | Brainstem | AmB, 5-FC, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Gongidi et al, 2013, US [16] | Curvularia sp | 37/M | Steroids, marijuana use | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | “IV antifungals,” surgery | Yes |

| Gagdil et al, 2013, US [17] | Curvularia sp | 50/F | Sinus surgery | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | Vori, surgery | Yes |

| Gagdil et al, 2013, US [18] | C geniculata | 35/M | Plasma cell dyscrasia | Unknown | Brain | AmB, vori, surgery | No |

| Singh et al, 2008 [18]; Australia [19] | C lunata | 57/M | None | Sino-pulmonary | Sinus, brain | AmB, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Carter et al, 2004, US [20] | C lunata | 21/M | Marijuana use | Unknown | Brain | AmB, 5-FC | No |

| Tessari et al, 2003, Italy [21] | C lunata | 68/M | Heart transplant | Cutaneous | Skin, lungs, GI tract | AmB | No |

| Levi & Basgoz, 2000, US [22] | Curvularia sp | 56/M | Lung transplant | Prosthetic material | Lung, pleura, pericardium, sternal wound, thyroid | AmB, itra, 5-FC | No |

| Ebright et al, 1999, US [23] | C clavata | 46/F | Chronic sinusitis | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | AmB, itra, surgery | Yes |

| Bryan et al, 1993, US [9] | C lunata | 44/M | None | Unknown | PVE, aortic root | AmB, ket, terb, surgery | Yes |

| Pierce et al, 1986, US [24]; de la Monte & Hutchins, 1985, US [25] | C lunata | 42/M | T-cell deficiency | Unknown | Lung, brain | AmB, ket, mico, surgery | Yes |

| Rohwedder et al, 1979, US [26] | C lunata | 25/M | None | Cutaneous | Lung, lymph node, skin, muscle, brain, spine | AmB, mico, surgery | Yes |

| Harris & Downham, 1978, US [27] | Curvularia sp | 27/M | None | Cutaneous | Lung, spine | AmB, 5-FC, mico | Yes |

| Kaufman, 1971, US [10] | C geniculata | 41/M | None | Unknown | Aortic homograft, brain, spleen, kidney, thyroid | Surgery | No |

Abbreviations: 5-FC, flucytosine; AmB, amphotericin B; F, female; GI, gastrointestinal; itra, itraconazole; IV, intravenous; ket, ketoconazole; M, male; mica, micafungin; mico, miconazole; posa, posaconazole; PVE, prosthetic valve endocarditis; terb, terbinafine; US, United States; vori, voriconazole.

Cases of Invasive Curvularia Species Infection Reported in the Adult Literature (1970–June 2021)

| Reference . | Curvularia Species . | Patient Characteristics . | Presumed Source . | Site(s) of Disease . | Therapy . | Alive at Publication (Yes/No) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)/Sex . | Risk Factor(s) for Invasive Infection . | ||||||

| Current case | C alcornii | 53/M | None | Prosthetic material | PVE, aortic root, brain, spleen, kidneys, iliac arteries | AmB, vori, mica, posa, surgery | No |

| Rolfe et al, US, 2020 [7] | C lunata | 67/M | Lung transplant | Prosthetic material | Lungs, pleural space | AmB, surgery | No |

| Djenontin et al, Mali, 2020 [11] | C sp | 44/F | None | Traumatic inoculation following road accident | Native knee septic arthritis | AmB, posa, surgery | No |

| Gonzales Zamora et al, US, 2019 [12] | Curvularia sp | 42/F | Heart, kidney transplant | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | AmB, vori | No |

| Vasikasin et al, 2019, Thailand [13] | C tuberculata | 22/M | None | Cutaneous | Skin, lungs | AmB | Yes |

| Shrivastava et al, 2017, India [14] | C lunata | 48/M | None | Cutaneous | Epidural space | AmB, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Skovrlj et al, 2014, US [15] | Curvularia sp | 33/M | Marijuana use | Sino-pulmonary | Brainstem | AmB, 5-FC, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Gongidi et al, 2013, US [16] | Curvularia sp | 37/M | Steroids, marijuana use | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | “IV antifungals,” surgery | Yes |

| Gagdil et al, 2013, US [17] | Curvularia sp | 50/F | Sinus surgery | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | Vori, surgery | Yes |

| Gagdil et al, 2013, US [18] | C geniculata | 35/M | Plasma cell dyscrasia | Unknown | Brain | AmB, vori, surgery | No |

| Singh et al, 2008 [18]; Australia [19] | C lunata | 57/M | None | Sino-pulmonary | Sinus, brain | AmB, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Carter et al, 2004, US [20] | C lunata | 21/M | Marijuana use | Unknown | Brain | AmB, 5-FC | No |

| Tessari et al, 2003, Italy [21] | C lunata | 68/M | Heart transplant | Cutaneous | Skin, lungs, GI tract | AmB | No |

| Levi & Basgoz, 2000, US [22] | Curvularia sp | 56/M | Lung transplant | Prosthetic material | Lung, pleura, pericardium, sternal wound, thyroid | AmB, itra, 5-FC | No |

| Ebright et al, 1999, US [23] | C clavata | 46/F | Chronic sinusitis | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | AmB, itra, surgery | Yes |

| Bryan et al, 1993, US [9] | C lunata | 44/M | None | Unknown | PVE, aortic root | AmB, ket, terb, surgery | Yes |

| Pierce et al, 1986, US [24]; de la Monte & Hutchins, 1985, US [25] | C lunata | 42/M | T-cell deficiency | Unknown | Lung, brain | AmB, ket, mico, surgery | Yes |

| Rohwedder et al, 1979, US [26] | C lunata | 25/M | None | Cutaneous | Lung, lymph node, skin, muscle, brain, spine | AmB, mico, surgery | Yes |

| Harris & Downham, 1978, US [27] | Curvularia sp | 27/M | None | Cutaneous | Lung, spine | AmB, 5-FC, mico | Yes |

| Kaufman, 1971, US [10] | C geniculata | 41/M | None | Unknown | Aortic homograft, brain, spleen, kidney, thyroid | Surgery | No |

| Reference . | Curvularia Species . | Patient Characteristics . | Presumed Source . | Site(s) of Disease . | Therapy . | Alive at Publication (Yes/No) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)/Sex . | Risk Factor(s) for Invasive Infection . | ||||||

| Current case | C alcornii | 53/M | None | Prosthetic material | PVE, aortic root, brain, spleen, kidneys, iliac arteries | AmB, vori, mica, posa, surgery | No |

| Rolfe et al, US, 2020 [7] | C lunata | 67/M | Lung transplant | Prosthetic material | Lungs, pleural space | AmB, surgery | No |

| Djenontin et al, Mali, 2020 [11] | C sp | 44/F | None | Traumatic inoculation following road accident | Native knee septic arthritis | AmB, posa, surgery | No |

| Gonzales Zamora et al, US, 2019 [12] | Curvularia sp | 42/F | Heart, kidney transplant | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | AmB, vori | No |

| Vasikasin et al, 2019, Thailand [13] | C tuberculata | 22/M | None | Cutaneous | Skin, lungs | AmB | Yes |

| Shrivastava et al, 2017, India [14] | C lunata | 48/M | None | Cutaneous | Epidural space | AmB, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Skovrlj et al, 2014, US [15] | Curvularia sp | 33/M | Marijuana use | Sino-pulmonary | Brainstem | AmB, 5-FC, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Gongidi et al, 2013, US [16] | Curvularia sp | 37/M | Steroids, marijuana use | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | “IV antifungals,” surgery | Yes |

| Gagdil et al, 2013, US [17] | Curvularia sp | 50/F | Sinus surgery | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | Vori, surgery | Yes |

| Gagdil et al, 2013, US [18] | C geniculata | 35/M | Plasma cell dyscrasia | Unknown | Brain | AmB, vori, surgery | No |

| Singh et al, 2008 [18]; Australia [19] | C lunata | 57/M | None | Sino-pulmonary | Sinus, brain | AmB, vori, surgery | Yes |

| Carter et al, 2004, US [20] | C lunata | 21/M | Marijuana use | Unknown | Brain | AmB, 5-FC | No |

| Tessari et al, 2003, Italy [21] | C lunata | 68/M | Heart transplant | Cutaneous | Skin, lungs, GI tract | AmB | No |

| Levi & Basgoz, 2000, US [22] | Curvularia sp | 56/M | Lung transplant | Prosthetic material | Lung, pleura, pericardium, sternal wound, thyroid | AmB, itra, 5-FC | No |

| Ebright et al, 1999, US [23] | C clavata | 46/F | Chronic sinusitis | Sino-pulmonary | Brain | AmB, itra, surgery | Yes |

| Bryan et al, 1993, US [9] | C lunata | 44/M | None | Unknown | PVE, aortic root | AmB, ket, terb, surgery | Yes |

| Pierce et al, 1986, US [24]; de la Monte & Hutchins, 1985, US [25] | C lunata | 42/M | T-cell deficiency | Unknown | Lung, brain | AmB, ket, mico, surgery | Yes |

| Rohwedder et al, 1979, US [26] | C lunata | 25/M | None | Cutaneous | Lung, lymph node, skin, muscle, brain, spine | AmB, mico, surgery | Yes |

| Harris & Downham, 1978, US [27] | Curvularia sp | 27/M | None | Cutaneous | Lung, spine | AmB, 5-FC, mico | Yes |

| Kaufman, 1971, US [10] | C geniculata | 41/M | None | Unknown | Aortic homograft, brain, spleen, kidney, thyroid | Surgery | No |

Abbreviations: 5-FC, flucytosine; AmB, amphotericin B; F, female; GI, gastrointestinal; itra, itraconazole; IV, intravenous; ket, ketoconazole; M, male; mica, micafungin; mico, miconazole; posa, posaconazole; PVE, prosthetic valve endocarditis; terb, terbinafine; US, United States; vori, voriconazole.

The current case is strikingly similar to 2 previously reported cases of Curvularia endocarditis. Kaufman et al described a patient presenting 6 months after aortic homograft placement with mycotic aneurysms of the aorta and septic emboli to the spleen, kidneys, and brain [10]. Premortem and postmortem tissue isolated Curvularia geniculata. Bryan et al reported a case of Curvularia lunata prosthetic valve endocarditis and aortic mycotic aneurysm presenting 6 months after aortic valve replacement and 2 months of fevers, sweats, and lower back pain [9]. In all 3, the lack of a cutaneous or sinopulmonary portal of entry raises the possibility of periprocedural exposure.

Curvularia species have been cultured from the surfaces and air of clinical environments, including operating rooms [28, 29]. One study reported that 5.6% of molds isolated from surveillance culture plates placed throughout an intensive care unit (ICU) were identified as Curvularia species [29]. Reports of postoperative Curvularia infections suggest a healthcare environmental origin. A lung transplant recipient developed Curvularia lunata pleural and pericardial infection following a prolonged period with an open chest and multiple chest cavity explorations [7]. In this case, a black mold was seen growing inside the chest tubes. However, environmental sampling of the ICU did not reveal Curvularia. Levi and Basgoz described a lung transplant patient who developed Curvularia infection of the sternal wound extending to the lung parenchyma, pleural space, and pericardium [22]. Another report described a neonatal sternal wound infection with Curvularia lunata following cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease complicated by cardiac tamponade and delayed chest closure [30]. In all 3 cases, the infection was fatal.

In 2000, investigators reported an outbreak of 5 Curvularia infections associated with breast implant surgery [31]. Curvularia was found in 2 environmental sources: saline bottles stored in a supply room with a water-damaged ceiling and the corridor outside an operating room. The postulated mechanisms of contamination of the surgical site were via spores on the saline bottles or saline in open bowls during the procedure.

Our patient’s case and the evidence reviewed here suggest that environmental contamination at the time of valve surgery may have been the source of Curvularia infection. An investigation for a possible environmental exposure was not conducted at our institution, as the original surgery took place elsewhere. His unfortunate outcome, despite maximal medical and surgical treatment, serves as reminder of the high mortality associated with invasive disease. Clinicians should be aware of this late-occurring deep surgical site infection, and such cases should be investigated for origins within healthcare facilities.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors acknowledge Dr William La Via, Medical Director of Karius, for his assistance with the Karius Test and its interpretation in the clinical setting.

Patient consent statement. Every effort was made to contact the family of the patient, but unfortunately, we were unable to make contact to obtain consent. Both the patient’s wife and daughter had contact details at both hospitals where the patient was hospitalized. Two authors (S. N. and R. A. B.) called both numbers on different occasions (various dates and times of day) and left messages on voicemail to contact us regarding publication of the case report. We called repeatedly and sent text messages, but were unable to make contact. Ample time (2 weeks) was given for a response. All clinical information and images have been anonymized sufficiently to protect the patient’s privacy and identity. This research did not require ethical review board approval.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Comments