-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Joanne H Hunt, Oliver Laeyendecker, Richard E Rothman, Reinaldo E Fernandez, Gaby Dashler, Patrizio Caturegli, Bhakti Hansoti, Thomas C Quinn, Yu-Hsiang Hsieh, A Potential Screening Strategy to Identify Probable Syphilis Infections in the Urban Emergency Department Setting, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 11, Issue 5, May 2024, ofae207, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofae207

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Syphilis diagnosis in the emergency department (ED) setting is often missed due to the lack of ED-specific testing strategies. We characterized ED patients with high-titer syphilis infections (HTSIs) with the goal of defining a screening strategy that most parsimoniously identifies undiagnosed, untreated syphilis infections.

Unlinked, de-identified remnant serum samples from patients attending an urban ED, between 10 January and 9 February 2022, were tested using a three-tier testing algorithm, and sociodemographic variables were extracted from ED administrative database prior to testing. Patients who tested positive for treponemal antibodies in the first tier and positive at high titer (≥1:8) for nontreponemal antibodies in the second tier were classified as HTSI. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status was determined with Bio-Rad enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and confirmatory assays. Exact logistic regression and classification and regression tree (CART) analyses were performed to determine factors associated with HTSI and derive screening strategies.

Among 1951 unique patients tested, 23 (1.2% [95% confidence interval, .8%–1.8%]) had HTSI. Of those, 18 (78%) lacked a primary care physician, 5 (22%) were HIV positive, and 8 (35%) were women of reproductive age (18–49 years). CART analysis (area under the curve of 0.67) showed that using a screening strategy that measured syphilis antibodies in patients with HIV, without a primary care physician, and women of reproductive age would have identified most patients with HTSI (21/23 [91%]).

We show a high prevalence of HTSI in an urban ED and propose a feasible, novel screening strategy to curtail community transmission and prevent long-term complications.

Over the past decade there has been a dramatic surge in syphilis cases in the United States (US), reaching the highest total case number since 1950 [1, 2]. From 2017 to 2021, primary and secondary infections rose 74%, totaling over 176 713 cases in 2021 [2]. When left undiagnosed and untreated, syphilis can spread in the community and can lead to serious multisystem complications, including ocular syphilis, neurosyphilis, and congenital syphilis [2, 3].

Emergency departments (EDs) often provide emergent and primary care to populations who are underserved and/or of lower socioeconomic status [3–6]. EDs are critical for identifying and diagnosing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in patients who might otherwise lack access to screening [3, 5–8]. According to the 2022 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), persons at greater risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men, people with human immunodeficiency virus (PWH) or other STIs, people who use drugs, and people with a history of incarceration, sex work, or military service [9, 10]. In practice, clinicians ultimately decide which patient to test, integrating the patient’s risk profile in the local context of disease [1, 10, 11]. Given the fast-paced ED setting, clinicians face inherent challenges to assess the patient's priority health concerns, and as a result, syphilis screening is frequently overlooked [12].

The three-tier testing algorithm used to confirm a syphilis infection detects both nontreponemal and treponemal antibodies and is thus intrinsically more time-consuming and complex than other STI tests [12, 13]. Consequently, typically only ED patients presenting with symptoms consistent with primary or secondary syphilis are identified [8, 12, 13]. Recent ED studies have proposed integration of syphilis testing into existing STI/human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screening programs and have reported high rates of underrecognized syphilis infections in the population [11]. Given most ED patients are discharged, and many have limited access to a primary care physician (PCP), missed opportunities likely exist for identifying asymptomatic and undiagnosed syphilis infections [14]. There are limited studies to date characterizing the risk factors associated with syphilis infection among ED patients, hindering the evidence-based design of ED-specific syphilis testing strategies [8, 15]. Recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines suggested a conservative approach for identifying patients with unknown duration of infection [16, 17]. When faced with uncertainty of patient history, high rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titers and positive treponemal serology may indicate a probable infection [16] and thus should be prioritized for identification and treatment given the heightened transmission risk during primary or secondary syphilis infection [16, 17]. In times of an epidemic surge, EDs could serve as sentinel sites to implement screening strategies, and thus help identify probable infections in the community [8, 15, 18].

Our study sought to (1) determine the point prevalence of seroreactive syphilis and high-titer syphilis infection (HTSI, operationally defined as treponemal positive and ≥1:8 nontreponemal antibodies) among adult ED patients in Baltimore, Maryland; (2) define and compare characteristics of seroreactive patients; and (3) inform a potential screening strategy to identify HTSI in our ED population.

METHODS

Patient Population

This retrospective cross-sectional analysis utilized de-identified, unlinked remnant blood samples from adults (≥18 years of age) who attended the Johns Hopkins Hospital emergency department (JHHED) between 10 January and 9 February 2022 and had blood drawn for clinical purposes. This urban, academic ED in Baltimore, Maryland, has approximately 60 000 patient visits per year and provides care to patients known to have a high prevalence of HIV, chlamydia, and gonorrhea [19, 20]. Since 2005, the JHHED has established a screening and linkage-to-care (LTC) program for HIV [21–23]. No screening protocol for syphilis currently exists.

Remnant blood samples and clinical data were collected as previously described [23, 24]. Briefly, sera were unlinked, de-identified, assigned unique research identifiers, and stored at −80°C until use. Demographic features (age, sex, race, and ethnicity), ED parameters (chief complaint, primary ED diagnosis, and disposition), and information about having a PCP and medical insurance were abstracted from the ED administrative database. Female patients aged between 18 and 49 years were considered to be of reproductive age [25].

Laboratory Methods

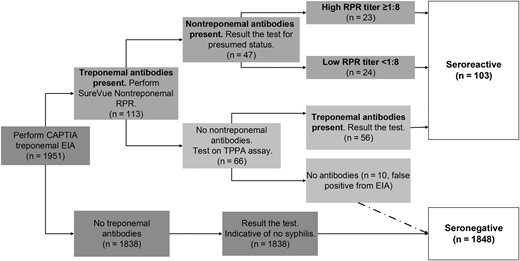

Syphilis status was determined by the presence of syphilis antibodies using the three-tier reverse algorithm (Figure 1) [26], employing 3 antibody assays with high sensitivity and specificity [27–29]. Detailed information on the serological testing is presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Flowchart of reverse algorithm 3-tier testing modality for syphilis. Abbreviations: EIA, enzyme immunoassay; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TPPA, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination.

Patients were classified as having an HTSI if their serum tested positive for treponemal antibodies and a high titer (≥1:8) of nontreponemal antibodies (Figure 1) [11, 13, 30]. Seroreactive patients were enzyme immunoassay (EIA) positive with a positive RPR (EIA+/RPR+) or were EIA positive, RPR negative, and Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA) positive (EIA+/RPR−/TPPA+) [11, 13]. Seronegative patients were EIA negative or EIA positive but RPR and TPPA negative. HIV status was determined using BioRad EIA and confirmatory assays as further detailed in the Supplementary Materials.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were employed to characterize the sociodemographic and clinical features of ED patients, and multivariable exact logistic regression identified factors associated with HTSI. A classification and regression tree (CART) analysis was used as an algorithm to inform the proposed ED-specific screening strategies to identify and manage HTSI [16, 17, 31]. A 2-sided P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses. Additional information on the statistical methodology is explained further in the Supplementary Materials.

IBM SPSS version 29.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) was used to conduct CART analyses, and SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for other analyses.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Using an identity-unlinked methodology for determining syphilis and HIV seroprevalence is permitted via a consent waiver and involves accessing remnant clinical blood specimens and pairing that with de-identified demographic and administrative data to characterize the seroepidemiology of disease [4, 23, 24].

RESULTS

Characteristics of Patient Population

Of the 3504 unique patients who attended JHHED during the 1-month study period (Supplementary Table 1), 1951 had a complete blood count with a remnant sample available for testing (Table 1). The study population was older (median [interquartile range] age, 47 [32–62] years vs 40 [30–56] years) and more likely to be female (52.0% vs 48.2%), to be White non-Hispanic (28.5% vs 23.3%), and to have a PCP (61.0% vs 51.6%) than those not evaluated due to lack of a blood draw for the ED clinical visit (Supplementary Table 1). Eighty-seven (4.5%) patients had serum antibodies indicative of HIV infection (Table 1).

Association Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Seropositivity of Syphilis Antibody Among 1951 Johns Hopkins Hospital Emergency Department Patients, January–February 2022a–c

| Characteristics . | Syphilis Serologic Status, No. (%) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total . | Seronegative . | Seroreactive . | Serology by Antibody Result . | |||

| EIA+/RPR–/TPPA+ . | EIA+/RPR <1:8 . | EIA+/RPR ≥1:8 . | ||||

| No. of patients | 1951 | 1848 (94.7) | 103 (5.3) | 56 (2.9) | 24 (1.2) | 23 (1.2) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–24 | 202 | 194 (96.0) | 8 (4.0) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| 25–34 | 387 | 374 (96.6) | 13 (3.4) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 8 (2.1) |

| 35–44 | 321 | 305 (95.0) | 16 (5.0) | 9 (2.8) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| 45–54 | 290 | 271 (93.5) | 19 (6.5) | 11 (3.8) | 5 (1.7) | 3 (1.0) |

| 55–64 | 344 | 313 (91.0) | 31 (9.0) | 22 (6.4) | 6 (1.7) | 3 (0.9) |

| ≥65 | 405 | 389 (96.1) | 16 (3.9) | 10 (2.5) | 5 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 936 | 873 (93.3) | 63 (6.7) | 22 (2.4) | 9 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) |

| Female | 1015 | 975 (96.1) | 40 (3.9) | 34 (3.3) | 15 (1.5) | 14 (1.4) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 556 | 544 (97.8) | 12 (2.2) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1108 | 1032 (93.1) | 76 (6.9) | 44 (4.0) | 19 (1.7) | 13 (1.2) |

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 134 | 131 (97.8) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Hispanic | 153 | 141 (92.2) | 12 (7.8) | 6 (3.9) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) |

| Having PCP | ||||||

| No | 761 | 707 (92.9) | 54 (7.1) | 22 (2.9) | 14 (1.8) | 18 (2.4) |

| Yes | 1190 | 1141 (95.9) | 49 (4.1) | 34 (2.9) | 10 (0.8) | 5 (0.4) |

| ED disposition | ||||||

| Discharge | 1022 | 955 (93.4) | 67 (6.6) | 36 (3.5) | 14 (1.4) | 17 (1.7) |

| Hospital observation | 475 | 455 (95.8) | 20 (4.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Admit | 298 | 286 (96.0) | 12 (4.0) | 13 (4.4) | 5 (1.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Other | 156 | 152 (97.4) | 4 (2.6) | 6 (3.8) | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) |

| HIV infection | ||||||

| No | 1864 | 1779 (95.4) | 85 (4.6) | 47 (2.5) | 20 (1.1) | 18 (1.0) |

| Yes | 87 | 69 (79.3) | 18 (20.7) | 9 (10.3) | 4 (4.6) | 5 (5.7) |

| Characteristics . | Syphilis Serologic Status, No. (%) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total . | Seronegative . | Seroreactive . | Serology by Antibody Result . | |||

| EIA+/RPR–/TPPA+ . | EIA+/RPR <1:8 . | EIA+/RPR ≥1:8 . | ||||

| No. of patients | 1951 | 1848 (94.7) | 103 (5.3) | 56 (2.9) | 24 (1.2) | 23 (1.2) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–24 | 202 | 194 (96.0) | 8 (4.0) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| 25–34 | 387 | 374 (96.6) | 13 (3.4) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 8 (2.1) |

| 35–44 | 321 | 305 (95.0) | 16 (5.0) | 9 (2.8) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| 45–54 | 290 | 271 (93.5) | 19 (6.5) | 11 (3.8) | 5 (1.7) | 3 (1.0) |

| 55–64 | 344 | 313 (91.0) | 31 (9.0) | 22 (6.4) | 6 (1.7) | 3 (0.9) |

| ≥65 | 405 | 389 (96.1) | 16 (3.9) | 10 (2.5) | 5 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 936 | 873 (93.3) | 63 (6.7) | 22 (2.4) | 9 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) |

| Female | 1015 | 975 (96.1) | 40 (3.9) | 34 (3.3) | 15 (1.5) | 14 (1.4) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 556 | 544 (97.8) | 12 (2.2) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1108 | 1032 (93.1) | 76 (6.9) | 44 (4.0) | 19 (1.7) | 13 (1.2) |

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 134 | 131 (97.8) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Hispanic | 153 | 141 (92.2) | 12 (7.8) | 6 (3.9) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) |

| Having PCP | ||||||

| No | 761 | 707 (92.9) | 54 (7.1) | 22 (2.9) | 14 (1.8) | 18 (2.4) |

| Yes | 1190 | 1141 (95.9) | 49 (4.1) | 34 (2.9) | 10 (0.8) | 5 (0.4) |

| ED disposition | ||||||

| Discharge | 1022 | 955 (93.4) | 67 (6.6) | 36 (3.5) | 14 (1.4) | 17 (1.7) |

| Hospital observation | 475 | 455 (95.8) | 20 (4.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Admit | 298 | 286 (96.0) | 12 (4.0) | 13 (4.4) | 5 (1.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Other | 156 | 152 (97.4) | 4 (2.6) | 6 (3.8) | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) |

| HIV infection | ||||||

| No | 1864 | 1779 (95.4) | 85 (4.6) | 47 (2.5) | 20 (1.1) | 18 (1.0) |

| Yes | 87 | 69 (79.3) | 18 (20.7) | 9 (10.3) | 4 (4.6) | 5 (5.7) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; EIA, Captia treponemal enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PCP, primary care physician; RPR, Sure-Vue rapid plasma reagin nontreponemal assay; TPPA, Serodia treponemal agglutination assay.

aThere were statistically significant differences (ie, P < .05) in age group, sex, race/ethnicity, having a PCP, and HIV infection between ED patients seroreactive for syphilis antibodies and those seronegative for syphilis.

bThere were statistically significant differences in age group and having a PCP among the 3 subgroups (EIA+/RPR–/TPPA+, EIA+/RPR <1:8, and EIA+/RPR ≥1:8) in those with seroreactive results (all P < .01).

cThere were statistically significant differences (ie, P < .05) in age group, sex, race/ethnicity, having a PCP, and HIV infection among ED patients with high-titer syphilis infection (EIA+/RPR ≥1:8), those with seroreactive but not high-titer syphilis infection for syphilis antibodies (EIA+/RPR–/TPPA+, EIA+/RPR <1:8), and those seronegative for syphilis.

Association Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Seropositivity of Syphilis Antibody Among 1951 Johns Hopkins Hospital Emergency Department Patients, January–February 2022a–c

| Characteristics . | Syphilis Serologic Status, No. (%) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total . | Seronegative . | Seroreactive . | Serology by Antibody Result . | |||

| EIA+/RPR–/TPPA+ . | EIA+/RPR <1:8 . | EIA+/RPR ≥1:8 . | ||||

| No. of patients | 1951 | 1848 (94.7) | 103 (5.3) | 56 (2.9) | 24 (1.2) | 23 (1.2) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–24 | 202 | 194 (96.0) | 8 (4.0) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| 25–34 | 387 | 374 (96.6) | 13 (3.4) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 8 (2.1) |

| 35–44 | 321 | 305 (95.0) | 16 (5.0) | 9 (2.8) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| 45–54 | 290 | 271 (93.5) | 19 (6.5) | 11 (3.8) | 5 (1.7) | 3 (1.0) |

| 55–64 | 344 | 313 (91.0) | 31 (9.0) | 22 (6.4) | 6 (1.7) | 3 (0.9) |

| ≥65 | 405 | 389 (96.1) | 16 (3.9) | 10 (2.5) | 5 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 936 | 873 (93.3) | 63 (6.7) | 22 (2.4) | 9 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) |

| Female | 1015 | 975 (96.1) | 40 (3.9) | 34 (3.3) | 15 (1.5) | 14 (1.4) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 556 | 544 (97.8) | 12 (2.2) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1108 | 1032 (93.1) | 76 (6.9) | 44 (4.0) | 19 (1.7) | 13 (1.2) |

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 134 | 131 (97.8) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Hispanic | 153 | 141 (92.2) | 12 (7.8) | 6 (3.9) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) |

| Having PCP | ||||||

| No | 761 | 707 (92.9) | 54 (7.1) | 22 (2.9) | 14 (1.8) | 18 (2.4) |

| Yes | 1190 | 1141 (95.9) | 49 (4.1) | 34 (2.9) | 10 (0.8) | 5 (0.4) |

| ED disposition | ||||||

| Discharge | 1022 | 955 (93.4) | 67 (6.6) | 36 (3.5) | 14 (1.4) | 17 (1.7) |

| Hospital observation | 475 | 455 (95.8) | 20 (4.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Admit | 298 | 286 (96.0) | 12 (4.0) | 13 (4.4) | 5 (1.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Other | 156 | 152 (97.4) | 4 (2.6) | 6 (3.8) | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) |

| HIV infection | ||||||

| No | 1864 | 1779 (95.4) | 85 (4.6) | 47 (2.5) | 20 (1.1) | 18 (1.0) |

| Yes | 87 | 69 (79.3) | 18 (20.7) | 9 (10.3) | 4 (4.6) | 5 (5.7) |

| Characteristics . | Syphilis Serologic Status, No. (%) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total . | Seronegative . | Seroreactive . | Serology by Antibody Result . | |||

| EIA+/RPR–/TPPA+ . | EIA+/RPR <1:8 . | EIA+/RPR ≥1:8 . | ||||

| No. of patients | 1951 | 1848 (94.7) | 103 (5.3) | 56 (2.9) | 24 (1.2) | 23 (1.2) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–24 | 202 | 194 (96.0) | 8 (4.0) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| 25–34 | 387 | 374 (96.6) | 13 (3.4) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 8 (2.1) |

| 35–44 | 321 | 305 (95.0) | 16 (5.0) | 9 (2.8) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| 45–54 | 290 | 271 (93.5) | 19 (6.5) | 11 (3.8) | 5 (1.7) | 3 (1.0) |

| 55–64 | 344 | 313 (91.0) | 31 (9.0) | 22 (6.4) | 6 (1.7) | 3 (0.9) |

| ≥65 | 405 | 389 (96.1) | 16 (3.9) | 10 (2.5) | 5 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 936 | 873 (93.3) | 63 (6.7) | 22 (2.4) | 9 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) |

| Female | 1015 | 975 (96.1) | 40 (3.9) | 34 (3.3) | 15 (1.5) | 14 (1.4) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 556 | 544 (97.8) | 12 (2.2) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1108 | 1032 (93.1) | 76 (6.9) | 44 (4.0) | 19 (1.7) | 13 (1.2) |

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 134 | 131 (97.8) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Hispanic | 153 | 141 (92.2) | 12 (7.8) | 6 (3.9) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) |

| Having PCP | ||||||

| No | 761 | 707 (92.9) | 54 (7.1) | 22 (2.9) | 14 (1.8) | 18 (2.4) |

| Yes | 1190 | 1141 (95.9) | 49 (4.1) | 34 (2.9) | 10 (0.8) | 5 (0.4) |

| ED disposition | ||||||

| Discharge | 1022 | 955 (93.4) | 67 (6.6) | 36 (3.5) | 14 (1.4) | 17 (1.7) |

| Hospital observation | 475 | 455 (95.8) | 20 (4.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Admit | 298 | 286 (96.0) | 12 (4.0) | 13 (4.4) | 5 (1.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Other | 156 | 152 (97.4) | 4 (2.6) | 6 (3.8) | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) |

| HIV infection | ||||||

| No | 1864 | 1779 (95.4) | 85 (4.6) | 47 (2.5) | 20 (1.1) | 18 (1.0) |

| Yes | 87 | 69 (79.3) | 18 (20.7) | 9 (10.3) | 4 (4.6) | 5 (5.7) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; EIA, Captia treponemal enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PCP, primary care physician; RPR, Sure-Vue rapid plasma reagin nontreponemal assay; TPPA, Serodia treponemal agglutination assay.

aThere were statistically significant differences (ie, P < .05) in age group, sex, race/ethnicity, having a PCP, and HIV infection between ED patients seroreactive for syphilis antibodies and those seronegative for syphilis.

bThere were statistically significant differences in age group and having a PCP among the 3 subgroups (EIA+/RPR–/TPPA+, EIA+/RPR <1:8, and EIA+/RPR ≥1:8) in those with seroreactive results (all P < .01).

cThere were statistically significant differences (ie, P < .05) in age group, sex, race/ethnicity, having a PCP, and HIV infection among ED patients with high-titer syphilis infection (EIA+/RPR ≥1:8), those with seroreactive but not high-titer syphilis infection for syphilis antibodies (EIA+/RPR–/TPPA+, EIA+/RPR <1:8), and those seronegative for syphilis.

Overall Prevalence of Seroreactivity

Of the 1951 patients, 103 (5.3% [95% confidence interval {CI}, 4.3–6.4]) had detectable treponemal antibodies indicating a previous or active syphilis infection (Table 1). Prevalence of seroreactivity was higher in men than women (6.7% [63/936] vs 3.9% [40/1015], P < .05) and differed by race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, 2.2%; non-Hispanic Black, 6.9%; non-Hispanic other race, 2.2%; and Hispanic, 7.8%; P < .05). A significantly higher proportion of patients who did not have a PCP were seroreactive as compared to patients who had a PCP (7.1% [54/761] vs 4.1% [49/1109], P < .05) (Table 1). PWH also had a higher proportion of syphilis seroreactivity than HIV-seronegative participants (20.7% [18/87] vs 4.6% [85/1864], P < .05).

Seroprevalence of HTSI

The seroprevalence of HTSI in our study was 1.2% (95% CI, .8%–1.8%; n = 23/1951) (Table 1). Key sociodemographic, RPR titer, and ED clinical characteristics of the 23 patients with HTSI are presented in Table 2. RPR titers ranged from 1:8 to 1:256. Eight of 9 females were of reproductive age. Five patients were also living with HIV. Six of 9 female patients did not have a PCP. All patients with an RPR titer >1:32 (n = 10) had no PCP. Three patients presented to the ED with potential STI-related chief complaint and 2 had ED primary diagnoses directly related to syphilis.

Characteristics of 23 Johns Hopkins Hospital Emergency Department Patients With High-Titer Syphilis Infection (Rapid Plasma Reagin Titer ≥1:8) in a Seroprevalence Study of 1951 Patients, January–February 2022

| Subject . | Woman of Reproductive Age . | Has PCP . | HIV Status . | RPR Titer . | Chief Complaint . | ED Primary Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Positive | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 2 | No | Yes | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 3 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 4 | NA | Yes | Positive | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 5 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 6 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 7 | NA | No | Positive | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 8 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 9 | NA | Yes | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 10 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 11 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 12 | Yes | Yes | Negative | 1:32 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Exposure to syphilis |

| 13 | NA | No | Positive | 1:32 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 14 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:64 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 15 | NA | No | Negative | 1:64 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 16 | NA | No | Negative | 1:64 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 17 | NA | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 18 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Neurosyphilis |

| 19 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 20 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 21 | NA | No | Positive | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 22 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 23 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| Subject . | Woman of Reproductive Age . | Has PCP . | HIV Status . | RPR Titer . | Chief Complaint . | ED Primary Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Positive | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 2 | No | Yes | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 3 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 4 | NA | Yes | Positive | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 5 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 6 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 7 | NA | No | Positive | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 8 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 9 | NA | Yes | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 10 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 11 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 12 | Yes | Yes | Negative | 1:32 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Exposure to syphilis |

| 13 | NA | No | Positive | 1:32 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 14 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:64 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 15 | NA | No | Negative | 1:64 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 16 | NA | No | Negative | 1:64 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 17 | NA | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 18 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Neurosyphilis |

| 19 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 20 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 21 | NA | No | Positive | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 22 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 23 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NA, not applicable, patient was male; PCP, primary care physician; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; STI, sexually transmitted infection. Bold text in the table indicates which of the screening variables would have applied to identify this patient for syphilis screening. Bold and italic text in the table indicates possible syphilis-related ED chief complaint and syphilis-related ED diagnosis.

Characteristics of 23 Johns Hopkins Hospital Emergency Department Patients With High-Titer Syphilis Infection (Rapid Plasma Reagin Titer ≥1:8) in a Seroprevalence Study of 1951 Patients, January–February 2022

| Subject . | Woman of Reproductive Age . | Has PCP . | HIV Status . | RPR Titer . | Chief Complaint . | ED Primary Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Positive | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 2 | No | Yes | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 3 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 4 | NA | Yes | Positive | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 5 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 6 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 7 | NA | No | Positive | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 8 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 9 | NA | Yes | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 10 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 11 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 12 | Yes | Yes | Negative | 1:32 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Exposure to syphilis |

| 13 | NA | No | Positive | 1:32 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 14 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:64 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 15 | NA | No | Negative | 1:64 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 16 | NA | No | Negative | 1:64 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 17 | NA | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 18 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Neurosyphilis |

| 19 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 20 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 21 | NA | No | Positive | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 22 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 23 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| Subject . | Woman of Reproductive Age . | Has PCP . | HIV Status . | RPR Titer . | Chief Complaint . | ED Primary Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Positive | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 2 | No | Yes | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 3 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 4 | NA | Yes | Positive | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 5 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 6 | NA | No | Negative | 1:8 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 7 | NA | No | Positive | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 8 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 9 | NA | Yes | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 10 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 11 | NA | No | Negative | 1:16 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 12 | Yes | Yes | Negative | 1:32 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Exposure to syphilis |

| 13 | NA | No | Positive | 1:32 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 14 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:64 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 15 | NA | No | Negative | 1:64 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 16 | NA | No | Negative | 1:64 | Possible STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 17 | NA | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 18 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Neurosyphilis |

| 19 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 20 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:128 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 21 | NA | No | Positive | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 22 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

| 23 | Yes | No | Negative | 1:256 | Not STI/syphilis-related | Non-syphilis |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NA, not applicable, patient was male; PCP, primary care physician; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; STI, sexually transmitted infection. Bold text in the table indicates which of the screening variables would have applied to identify this patient for syphilis screening. Bold and italic text in the table indicates possible syphilis-related ED chief complaint and syphilis-related ED diagnosis.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Associations of HTSI

The prevalence of HTSI varied by sociodemographic factors in the bivariate analysis (Table 1). Male sex and being a woman of reproductive age were marginally associated with HTSI as compared to women who were not of reproductive age (prevalence ratio [PR], 6.7 [95% CI, .9–51.0], P = .067, and 6.3 [95% CI, .8–50.1], P = .085, respectively). HTSI was significantly associated with coinfection with HIV and having no PCP (PR, 6.3 [95% CI, 2.3–17.3], P < .001, and 5.7 [95% CI, 2.1–15.5], P < .001, respectively). Similar associations of HTSI with HIV coinfection and having no PCP were seen in the multivariate analyses (adjusted PR, 8.5 [95% CI, 2.3–25.8], P = .002, and 6.6 [95% CI, 2.3–23.3], P < .001, respectively).

ED Screening Strategy to Identify HTSI

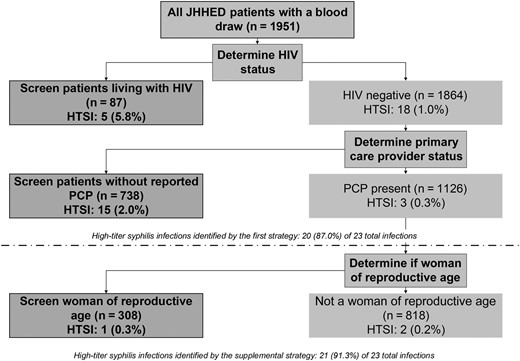

Screening all PWH and those without a PCP would identify 20 of the 23 (87%) ED patients with HTSI (AUC, 0.73 [95% CI, .64–.81]) (Figure 2). If women of reproductive age were also screened to address cases of congenital syphilis, 21 of 23 (91%) ED patients with HTSI would have been identified (AUC, 0.67 [95% CI, .58–.76]).

Decision tree for 2 proposed screening strategies for the identification of 23 Johns Hopkins Hospital emergency department patients with high-titer syphilis infection (rapid plasma reagin titer ≥1:8) from a seroprevalence study of 1951 patients, January–February 2022. Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTSI, high-titer syphilis infection; JHHED, Johns Hopkins Hospital emergency department; PCP, primary care physician.

DISCUSSION

We found that >5% of patients were seroreactive for syphilis, of which a quarter had high RPR titers (≥1:8). The strongest predictor of HTSI was among PWH, who were 8.5 times more likely to have HTSI. Our findings of an adjusted PR of 6.6 for those without a self-reported PCP and all HTSIs with RPR >1:32 without a self-reported PCP suggest the potential for PCP status to inform an ED syphilis screening strategy. Almost all (8/9) female patients with HTSI were of reproductive age, revealing the potential impact of ED screening to prevent congenital syphilis. CART analyses demonstrated that targeting screening to PWH, those without a self-reported PCP, and women of reproductive age could identify >90% of HTSIs. These findings suggest that an ED-specific screening strategy could potentially benefit populations that might otherwise remain undiagnosed and untreated. Further research is needed to tailor ED screening strategies to better address the testing needs across diverse ED settings.

From 2016 to 2020, primary and secondary syphilis rates surged by 50% in the US to 13 per 100 000 people and by 69% in Maryland to 14 per 100 000 people [31]. Our 1.2% prevalence of HTSI surpassed national and state averages, aligning with a recent ED study reporting a 1.1% prevalence of presumed active infections (defined as ≥1:8 RPR titer and relevant clinical history) [11]. These findings suggest a potential underestimation of syphilis prevalence, underlining the potential for robust ED screening programs to potentially identify undiagnosed cases and prevent further transmission in the community [11, 16, 32].

As a point of comparison, we reviewed information from the Johns Hopkins Hospital Pathology Laboratory referencing 4355 ED visits from 3504 unique patients during the study window (communication with co-author P. C.). Among the 76 clinician-initiated orders for T pallidum–specific antibody testing, we found 12 RPR-positive cases, 4 of which had high RPR titers (≥1:8). These 4 patients were likely included among the 23 HTSI identified in our study because all remnant blood specimens were obtained during the study window. These data highlight the potential missed opportunity in the ED to identify and treat syphilis infections among patients in the current epidemic.

Our study underscores the recent and evolving epidemiological evidence outlining associations between syphilis and HIV acquisition and supports the current USPSTF recommendation to screen all PWH [33, 34]. PWH were 8.5 times more likely to have HTSI than people without HIV. We found that 21.7% of patients with HTSI were coinfected with HIV, which aligns with another ED study that identified 23.7% of coinfections [11]. These data highlight the continued syndemic of syphilis and HIV [35] and support the integration of HIV and syphilis screening strategies to diagnose and treat all possible STIs that may be circulating in our ED populations [4, 10, 11].

To our knowledge, no studies have examined reported PCP status as a potential risk factor for syphilis screening. Patients who did not self-report having a PCP were 6.6 times as likely to have HTSI than those with a PCP, and only screening patients without a reported PCP would have identified 78% of HTSIs. Historically, routine screening practices were left to PCPs, but epidemiologic trends have shown that patients with low socioeconomic status face social and structural barriers that directly impact their access to primary care and instead use the ED for both primary and urgent care [3, 5, 11]. All 10 patients with an RPR titer >1:32 did not have a PCP, indicating significant clinical and public health implications. It is important to consider this finding given the CDC recommendation to prioritize syphilis cases of unknown duration with RPR titers >1:32 for further investigation and partner contact services [16, 17]. However, in the absence of patient clinical history, distinguishing active infection can be challenging, particularly among patients with low titers (<1:8) or who are RPR negative/TPPA positive. Our screening strategy aims to improve catchment by identifying all probable syphilis infections with an unknown duration of infection and elevated RPR titers (≥1:8), to conservatively manage patients with the highest transmission risk [16, 17].

The prevalence of HTSI varied by demographic characteristics. Thirty-nine percent (9/23) of HTSIs were found in female patients, a proportion consistent with findings from the Chicago ED study reporting 33% female presumed active infection [11]. Both figures were more than two times higher than the CDCs national rate of 14% [1]. Moreover, 8 of 9 female patients with HTSI were of reproductive age, which is particularly concerning given the increasing rates of congenital syphilis [13, 32, 36]. The CDC recently estimated that 88% of US congenital syphilis cases resulted from missed diagnosis and treatment of syphilis during pregnancy, and 40% of women who had a baby with syphilis in 2022 did not have access to prenatal care [32]. These findings highlight the potential opportunity for identifying syphilis infections outside of traditional prenatal care settings, such as EDs [32]. Historically, syphilis rates have been lower among women, but reported cases increased by 217% from 2017 to 2021 [1].

Almost 90% of HTSI patients presented to our ED with a non-STI-related chief complaint. More than half (56.9% [1992/3504]) of all ED patients seen during the study period, and 39.0% of our study sample, did not have a reported PCP (Supplementary Table 1). An ED-specific syphilis screening strategy integrating PCP status could improve screening catchment and potentially serve as a critical mechanism to reach an important sector of the population who may not otherwise have access to STI testing [8, 15].

Two proposed ED screening strategies were derived from our decision tree as a rational data-based starting strategy to guide ED-specific syphilis testing [37]. Both strategies showed (AUC = 0.73 and 0.67, respectively) that a targeted screening program focusing on PWH, patients without a reported PCP, and women of reproductive age could have identified approximately 90% of ED patients with HTSI who had blood drawn during their visit.

A previous ED study used automated testing reminders for physicians to minimize time constraints and leveraged existing HIV screening protocols to maximize the utility of an opt-out syphilis screening program [11]. We propose using the electronic medical record to automate the identification of patients with no reported PCP, PWH, or women of reproductive age for screening [22, 38]. This automated process could flag patients for recommended syphilis testing with pop-up best practice alerts during their initial clinical evaluation [11]. Best practice alerts have been effective in other EDs in bundling physician orders to test the patient for all STIs of concern and to augment LTC by outpatient clinics [15, 39, 40]. Drawing from our successful ED HIV screening and LTC programs, which have connected >90% of ED patients to care within 1 month of diagnosis and achieved viral suppression in 72% of PWH, our study could leverage existing infrastructure to establish a syphilis LTC and treatment program [14, 21, 22, 41]. Our program could expand the evidence base for ED-based syphilis screening, mirroring the achievements of our HIV LTC initiatives [14, 21, 22, 41].

There are several limitations that may affect the generalizability and practical relevance of our findings and suggested screening strategy in other ED settings [35]. First, only ED patients requiring blood draws for their standard medical care were included in this study (Supplementary Table 1). The characteristics of patients who did not have a blood sample available were statistically different from the population analyzed in our study. While this may limit the generalizability relative to the true prevalence of syphilis in the broader population, it is pragmatically justifiable given that only patients with blood drawn would be subject to the proposed screening program. This criterion ensures that the selected population is relevant to the proposed testing intervention. Second, the variables available to be electronically extracted from the ED administration database were limited and not necessarily optimized for this study. Risk factors referenced by the USPSTF (pregnancy status, previously known HIV status, sexual behaviors [ie, men who have sex with men], or history of injection drug use) may be essential for future analyses. However, gathering a comprehensive risk profile of factors that might further stigmatize already marginalized populations can be challenging, and future studies integrating a broader risk stratification approach could help inform screening strategies most relevant to the population. Given the constraints of our ED administrative database, the variables analyzed herein were sufficient to characterize ED patients with HTSI and inform a potential screening strategy. Last, PCP status should be interpreted carefully. ED registrars are trained to ask and verify PCP status during every visit; however, this evidence is self-reported and may not reflect patients’ utilization of PCP services. Further research including additional patient clinical history could assist in the interpretation of HTSI and enable clinicians to distinguish the stage of infection across diverse ED settings.

Our study revealed a syphilis seroreactivity rate exceeding 5%, with 1.2% exhibiting HTSI, aligning with multiple ED studies [11, 42]. This high prevalence raises concerns about potential syphilis underdiagnosis in our ED, emphasizing the potential for an ED-specific screening strategy to aid in identifying unrecognized and/or asymptomatic infections that may otherwise go undiagnosed or untreated [1]. Our proposed strategy incorporating HIV status, reported PCP status, and women of reproductive age could improve catchment of HTSI. Early identification is the critical first step for linking patients with treatment, curtailing transmission, and addressing congenital syphilis. Additional research, namely internal and external validation studies, is needed to evaluate the efficacy and practicality of parsimonious screening strategies for identifying patients with HTSI.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. O. L., R. R., B. H., T. C. Q., and Y.-H. H. designed the study. J. H. H. had primary responsibility for the remnant blood specimen and data collection. J. H. H. performed laboratory testing. O. L., R. E. F., and T. C. Q. supervised data collection. O. L. and R. E. F. supervised laboratory testing. Y.-H. H. performed data analyses. J. H. H., O. L., R. R., G. D., P. C., T. C. Q., and Y.-H. H. primarily interpreted results. J. H. H. and Y.-H. H. primarily drafted the manuscript. J. H. H., O. L., R. R., R. E. F., P. C., B. H., T. C. Q., and Y.-H. H. performed critical editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Patient consent. This identity-unlinked seroprevalence study was reviewed by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and was approved as an informed consent–waived research protocol (IRB00083646) due to the identity-unlinked methodology.

Financial support. This research was supported in part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

References

Author notes

O. L. and R. R. contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-second authors.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

Comments