-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Moon Kim, Matt Zahn, Roshan Reporter, Ziad Askar, Nicole Green, Michael Needham, Hilary Rosen, Akiko Kimura, Dawn Terashita, Outbreak of Foodborne Botulism Associated With Prepackaged Pouches of Liquid Herbal Tea, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 6, Issue 2, February 2019, ofz014, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz014

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In 2017, local public health authorities in California received reports of 2 elderly patients with suspected botulism who knew each other socially. A multijurisdictional investigation was conducted to determine the source.

Investigators reviewed medical records, interviewed family to establish food and drink histories, and inspected a facility that produced liquid herbal tea. Clinical specimens and product were tested for botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT).

A total of 2 confirmed botulism cases were identified with BoNT type A; both were hospitalized, 1 died. Botulism was not suspected until several days after hospital admission. Case-patients ingested single-serving prepackaged liquid herbal tea. Inspection of the tea production facility identified conditions conducive to product contamination with C botulinum and toxin production. Samples of tea tested negative for botulinum toxin. Local and state public health authorities issued alerts and the facility recalled the liquid herbal tea.

Liquid herbal tea prepackaged in sealed pouches was the likely source of this type A botulism outbreak because the 2 cases were linked socially and shared no other foods. This type of product has not previously been described in the foodborne botulism literature. In the absence of known risk factors for botulism at the time of presentation, suspicion based on clinically compatible findings is critical so that and treatment with botulinum antitoxin is not delayed. A coordinated response by public health authorities is necessary in identifying a potential food source, inspecting facilities producing the product, alerting medical providers and the public, and preventing further illness.

Botulism is a rare but serious and potentially fatal paralytic illness most commonly caused by the neurotoxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum and is considered a medical emergency. Suspected cases are mandated to be reported immediately to local and state public health authorities. Heptavalent botulinum antitoxin (BAT) is used to treat botulism and can only be released when authorized by local or state public health officials in coordination with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Los Angeles County, California, an average of 3 cases of adult botulism were confirmed annually between 2007 and 2017, and cases are primarily wound botulism associated with injection drug use. Foodborne botulism is uncommon; during that same period, only 2 cases of foodborne botulism were reported in Los Angeles County, and none were reported in Orange County. Symptoms of foodborne botulism generally begin 18 to 36 hours after ingesting a contaminated item, but they can begin as soon as 6 hours after exposure or up to 10 days later. Clostridium botulinum spores are found in both soil and water. Under certain conditions, such as low oxygen, low acidity, and unrefrigerated temperatures, C botulinum can proliferate and produce toxin.

In 2017, 2 elderly residents of California were identified with suspected botulism, presenting at hospitals 22 days apart. The Orange County Healthcare Agency (OCHCA), Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (LACDPH), and California Department of Public Health (CDPH) initiated an investigation to determine the source of illness, describe the clinical course, and prevent further illness.

METHODS

Epidemiological Investigation

A case was defined as an illness in a person clinically compatible with botulism that began between March 1, 2017 and June 1, 2017 and linked to a common ingested product before illness onset, with botulism toxin A detected by mouse bioassay in clinical specimens. Public health investigators conducted home visits to identify high-risk food and drink items and reviewed case-patients’ medical records. Because the case-patients were intubated, family members were interviewed to collect food and drink exposures in the 10 days before illness onset to identify common items. For case-finding, public health also obtained invoice records for other customers who purchased the common product.

Environmental Investigation

Local and state public health investigators inspected the facility (Company A) where the common product was produced. Investigators reviewed ingredient records and equipment used to produce the product. The owner and workers of Company A were interviewed regarding handling, production, and storage of the liquid herbal tea. Unopened product was obtained for botulinum toxin testing.

Laboratory Testing

Pre-antitoxin stools and serum specimens were tested by the LACDPH Laboratory for Case 1 and CDPH Microbial Diseases Laboratory for Case 2 using the mouse bioassay for C botulinum toxin. Testing of pH levels and presence of C botulinum neurotoxin and neurotoxin producing organisms in the suspected source product was performed by the CDPH Food and Drug Laboratory Branch.

RESULTS

Epidemiological Investigations

We identified 2 patients meeting the case definition. Case-patient 1 was an elderly Asian resident of California who presented to Hospital A in 2017 with slurred speech, bilateral ptosis, and left-sided weakness beginning 3 days before admission. Case-patient 1 required intubation due to respiratory failure later on the same day of admission. Imaging of the brain and cerebrospinal fluid were unremarkable. The disease progressed to complete bilateral paralysis, and on hospital day 13 clinicians consulted with their local public health and CDPH and BAT was released. Investigation conducted by local public health identified no obvious food sources. Case-patient 1 died on hospital day 29. Twenty-two days after Case-patient 1 was admitted, another elderly Asian resident of California was admitted to Hospital B with a 1-day history of vomiting, abdominal pain, diplopia, bilateral symmetric extraocular and facial palsy, dysphagia, and dyspnea. Case-patient 2 required intubation on the day of admission. Exam noted diffuse flaccid paralysis with minimal deep tendon reflexes. Brain imaging was unremarkable; a lumbar puncture was not performed. Clinicians at Hospital B suspected botulism on hospital day 4 and BAT was released by CDPH. No evidence of trauma, wounds, or history of injection drug use were present for either patient. Case-patients did not have any anatomic or functional bowel abnormalities or altered gastrointestinal flora associated with receipt of recent antimicrobials. On hospital day 24, Case-patient 2 was transferred to a long-term care facility for ventilator care and, at 14 months after illness onset, had some improvement in function but was unable to stand or walk.

Members of Case-patient 2’s family reported to local public health that they knew of Case-patient 1 being ill but denied the 2 sharing meals together. Review of both case-patient’s food histories with family members led to the identification of a single common exposure: both had ingested prepackaged liquid tea pouches containing herbs and deer antlers, which were part of a single purchase from Company A made by a mutual friend. No other shared or common food or drink items were identified. Three additional social contacts also ingested liquid herbal tea pouches from the same purchase. None of these contacts became ill.

Environmental Investigation

The LACDPH and CDPH conducted a site visit at Company A’s herbal tea production facility. The facility is a 2-story building containing dry herbs stored on shelves in boxes and jars from floor to ceiling. The liquid tea production, filling, and packaging are conducted in a separate room located on the 2nd floor room containing 12 industrial pressure cookers and 2 automated pouch filling and packaging machines. Company A’s customers are mostly from the local area, but their herbal products are also shipped to out-of-state customers. The liquid herbal tea was supplied in sealed pouches and sold in a box of 60 pouches; per Company A, 1 pouch (Figure 1A and B) is usually recommended to be taken twice a day. Instructions to refrigerate the pouches were written on the back of each individual pouch, but the instructions were not written in English. Instructions to refrigerate the pouches were also printed on a label, in English, on the outside of the cardboard box. Both cases reportedly kept the pouches refrigerated before use.

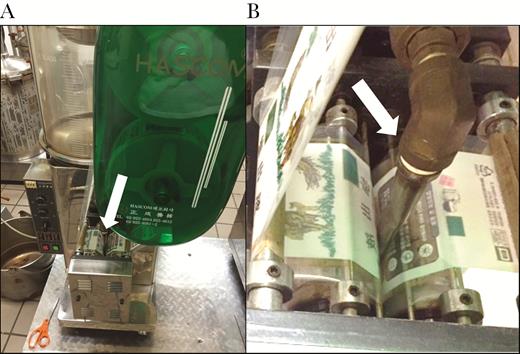

Company A produces pouches of liquid tea containing ingredients as advised by each customer’s herbal medicine practitioner. The liquid herbal tea production steps were described by Company A workers as follows: (1) dry herbs, plant products (eg, onions, dates), roots (eg, ginger), and sometimes sliced deer antlers were placed in a large tea bag (Figure 2A); (2) ingredients and water were boiled for 5 hours in industrial pressure cookers; (3) the liquid tea was either drained into uncovered stainless steel buckets using a flexible hose connected to the pressure cooker spigot or directly drained without hoses into uncovered stainless steel buckets from the spigot (Figure 2B); (4) the contents of the stainless steel bucket were then poured by workers into the reservoir of an automatic pouch filling and packaging machine (Figure 3A and B); (5) the packaging machine aliquoted the liquid tea into individual pouches containing approximately 120 mL liquid tea, which was then heat sealed. Use-by-dates, store identification, or lot numbers were not printed on the pouches. A review of Company A’s invoice records listed the tea ingredients consumed by the case-patients as deer antlers, dates, ginger, and huang qi (a dried root).

Pressure cookers: (A) tea bag inside containing dried herbs; (B) spigot draining into bucket.

(A) Automatic pouch filling machine and spout (white arrow); (B) close up of pouch film and filling spout (white arrow).

Deficiencies noted by public health inspectors included the following: the tea product was exposed to unsterilized pressure cooker drain spigots or hoses that were exposed to the processing room environment and not adequately controlled to prevent contamination; the product was exposed to unsterilized stainless steel buckets that were left uncovered and exposed to the processing room environment, which was not controlled to prevent contamination; the tea product was further exposed to the processing room environment while being carried over to the pouch filling and packaging machine.

Inspectors also observed large bags of unpeeled onions stored in the same room as pressure cookers and the pouch filling and packaging machine; the flexible hoses used to drain the liquid tea from the pressure cookers were stored on top of the onion bags. The product was exposed to unsterilized packaging pouch film in the packaging machine that was exposed to the processing room environment. In addition, the facility owner and workers failed to demonstrate knowledge of proper cleaning and sanitizing procedures for the equipment. Inspectors also noted that the gradual, uncontrolled pouch cooling process was inadequate in that the sealed pouches could be exposed to time and temperature ranges favorable to C botulinum spore germination.

During the site visit, LACDPH issued directives to Company A to discontinue tea production. The CDPH also directed Company A to cease tea processing immediately because they did not have the required CDPH-issued cannery license to manufacture low-acid canned foods. Review of invoice records showed that the liquid herbal tea pouches were also distributed to customers outside the state of California.

Laboratory Testing

Stool and serum for Case-patients 1 and 2 were positive by mouse bioassay for botulinum neurotoxin, toxin type A. In addition, toxin-producing C botulinum organisms were isolated from the stool of Case-patient 1. Seven unopened liquid tea pouches that remained from the common purchase, including pouches from the 2 case-patients and a friend who ingested the tea but did not become ill, were tested by CDPH and were negative for C botulinum toxin and toxin-producing C botulinum. Seven sealed liquid tea pouches obtained from Company A’s facility were also negative for C botulinum toxin and toxin-producing C botulinum. The pH of the liquid herbal tea obtained from the case-patients’ homes varied and ranged from 5.13 to 7.58.

Public Health Response

The LACDPH issued a press release, including to the local Asian media, warning residents not to consume the liquid herbal tea pouches. That same day, LACDPH distributed an alert to Los Angeles County hospitals providing healthcare providers information on the clinical manifestations of foodborne botulism and immediate reporting of suspected cases to public health authorities. The OCHCA also issued a press release and sent alerts to Orange County hospitals. The CDPH notified public health authorities from the out-of-state jurisdictions listed on customer invoice records and also issued a press release warning consumers regarding herbal tea produced by Company A and the risk of botulism.

In cooperation with CDPH, Company A issued a voluntarily recall of liquid herbal tea varieties produced between March 1, 2017 and April 30, 2017 due to risk for C botulinum. The recall was posted on the US Food and Drug Administration’s website. No additional botulism cases associated with liquid herbal tea pouches were reported in California or other states.

DISCUSSION

We describe an outbreak of botulism associated with the ingestion of liquid herbal tea packaged in sealed pouches [1]. The liquid herbal tea produced at Company A was the most likely source of the illness because the tea was the only common item known to be ingested by both patients; the tea was produced and packaged in air-tight pouches in a facility lacking the required CDPH-issued cannery license, where contamination with C botulinum could have occurred due to improper handling, production, and storage; C botulinum is commonly found in soil, and thus the onions or other root vegetables are inherently contaminated with soil and, as such, may present a more direct risk of food contamination than generic environmental contamination; and the tea was packaged in a low-acid, anaerobic environment, conditions where C botulinum can grow and produce toxin. Case-patients also had no known risk factors for botulism due to adult intestinal colonization and had epidemiologic links to consuming a common food product with high risk for botulism. The detection of neurotoxin-producing C botulinum in the stool of Case-patient 1 at approximately 2 weeks after symptom onset is not atypical. Clostridium botulinum detection in stool culture at 18 days after symptom onset has occurred in a previously reported foodborne botulism outbreak [2].

Botulism can be fatal and clinical recognition is often difficult in elderly patients. The differential diagnosis includes cerebrovascular disease, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and myasthenia gravis. Healthcare providers, most of whom rarely see botulism, might not suspect the diagnosis in patients when a history of injection drug use or ingestion of high-risk home canned or fermented foods is absent. Because laboratory testing for botulism may take days and risk factors might not be apparent at time of presentation, BAT should be given empirically and urgently based on clinical findings to prevent progression of paralysis or respiratory failure [3, 4]. Case 1 did not receive BAT until 2 weeks after hospitalization and later died. A recent review of botulism cases showed that respiratory involvement can occur early, and many patients require intubation on the first or second hospital day as with the 2 confirmed cases in this report [5].

Foods previously associated with botulism have included improperly canned commercial foods, home-canned or fermented fish, herb-infused oils, baked potatoes in aluminum foil, cheese sauce, and bottled garlic [6]. Liquid herbal tea sealed in pouches has not previously been reported in the literature to be associated with foodborne botulism. Low-acid foods have pH values greater than 4.6 and when processed and placed into sealed, air-tight containers such as cans, pouches, or jars, and not stored under temperature control, they can allow the growth of C botulinum and toxin production. Although we were unable to detect botulinum toxin in the liquid herbal tea product samples tested, this may be due to the varying amount of contamination or variations in the pouch environment. Variations in temperature and pH can occur during production and storage and thus not all pouches may have had conditions suitable for C botulinum toxin production.

CONCLUSIONS

This outbreak highlights several key points. First, it is important that healthcare providers have a high index of suspicion and immediately report suspected cases of botulism based on clinical findings to local and state public health authorities [4]. Consultation by public health is available around the clock to authorize release of BAT, which can prevent further paralysis or respiratory compromise if administered early in the course of illness, as well as to initiate appropriate diagnostic testing by public health that is not provided by standard commercial laboratories. Second, rapid reporting of suspected botulism by healthcare providers to public health authorities allows for immediate investigation, removal of potentially contaminated sources, and issuing of alerts to prevent further illness. Third, public health investigators should be aware of ingestible sources for botulinum toxin including exposures in drinks as well as foods. Ethnic foods unfamiliar to investigators can be challenging [7]. Prepackaged liquid herbal tea pouches have not, to our knowledge, been previously recognized as a product causing foodborne botulism [6]. However, because the production process is similar to canning, public health investigators should be aware that drink products including those packaged in sealed pouches with low-acid content and low or no oxygen environments can be suitable for C botulinum growth and toxin production if stored or produced improperly. This underscores the importance of governmental regulations and inspection of facilities producing food and drinks. Finally, rapid coordination with local, state, and federal agencies is essential in alerting healthcare providers and the public to a potential foodborne botulism risk.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge June Nakagawa and Lillian Araiza (California Department of Public Health [CDPH] Food and Drug Branch), the CDPH Food and Drug Laboratory Branch, and the CDPH Microbial Diseases Laboratory.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

California Code of Regulations, Title 17, Section 2500 (a) (14): “Foodborne disease outbreak” means an incident in which 2 or more persons experience a similar illness after ingestion of a common food, and epidemiologic analysis implicates the food as the source of the illness.

Comments