-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Liang En Wee, Jue Tao Lim, Janice Yu Jin Tan, Calvin Chiew, Chee-Fu Yung, Chia Yin Chong, David Chien Lye, Kelvin Bryan Tan, Long-term Sequelae Following Dengue Infection vs SARS-CoV-2 Infection in a Pediatric Population: A Retrospective Cohort Study, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 12, Issue 4, April 2025, ofaf134, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaf134

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Long-term postacute sequelae following SARS-CoV-2 infection in children have been extensively documented. However, while persistence of chronic symptoms following pediatric dengue infection has been documented in small prospective cohorts, population-based studies are limited. We evaluated the risk of multisystemic complications following dengue infection in contrast to that after SARS-CoV-2 infection in a multiethnic pediatric Asian population.

This retrospective population-based cohort study utilized national COVID-19/dengue registries to construct cohorts of Singaporean children aged 1 to 17 years with either laboratory-confirmed dengue infection from 1 January 2017 to 31 October 2022 or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection from 1 July 2021 to 31 October 2022. Cox regression was utilized to estimate risks of new-incident cardiovascular, neurologic, gastrointestinal, autoimmune, and respiratory complications, as identified by national health care claims data, at 31 to 300 days after dengue infection vs COVID-19. Risks were reported by 2 measures: adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) and excess burden.

This study included 6452 children infected with dengue and 260 749 cases of COVID-19. Among children infected with dengue, there was increased risk of any postacute gastrointestinal sequelae (aHR, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.18–7.18), specifically appendicitis (aHR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.36–8.99), when compared with children infected with SARS-CoV-2. In contrast to cases of unvaccinated COVID-19, children infected with dengue demonstrated lower risk (aHR, 0.42; 95% CI, .29–.61) and excess burden (−6.50; 95% CI, −9.80 to –3.20) of any sequelae, as well as lower risk of respiratory sequelae (aHR, 0.17; 95% CI, .09–.31).

Lower overall risk of postacute complications was observed in children following dengue infection vs COVID-19; however, higher risk of appendicitis was reported 31 to 300 days after dengue infection vs SARS-CoV-2. Public health strategies to mitigate the impact of dengue and COVID-19 in children should consider the possibility of chronic postinfectious sequelae.

Long-term postacute sequelae across multiple organ systems following SARS-CoV-2 infection in children have been documented across large population-based cohort studies [1–5]. Chronic symptom persistence following COVID-19 has been postulated to arise from exacerbation of preexisting conditions, viral persistence, or other postinfectious immunologic responses [1]. However, long-term sequelae may also occur following infections other than SARS-CoV-2, some with epidemic potential.

Dengue is one such example, with dengue epidemics occurring seasonally in tropical regions. Given the resurgence of dengue due to global warming and climate change, autochthonous dengue transmission has been reported even in temperate regions during favorable seasons [6], and imported pediatric cases can occur outside tropical regions [7]. Chronic persistence of a spectrum of postviral symptoms, including fatigue, myalgia, visual disturbances, loss of appetite, and gastrointestinal symptoms, has been reported following dengue infection in children and adults [8–11]; yet, the small size of these prospective cohorts and methodological limitations restricted generalizability, and uncertainty still exists regarding the extent and spectrum of chronic symptoms after dengue infection. Population-wide retrospective studies can better elucidate long-term sequelae after dengue infection and have demonstrated increased risk of cardiovascular, neurologic, and autoimmune complications in the postacute period following dengue infection in adults [12–16], with increased risk of postacute cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric complications observed in adult dengue survivors vs COVID-19 survivors infected during Delta and Omicron predominance [17]. However, no similar studies have been conducted in the pediatric population.

As such, to fill this gap, we conducted a population-wide retrospective cohort study among Singaporean children aged 1 to 17 years to estimate risks of new-incident complications up to 300 days after dengue infection, contrasted against that observed following COVID-19, for which long-term sequelae are better characterized. Risks of postacute sequelae following dengue infection in children were hypothesized to be comparable to those occurring after COVID-19, with the exception of respiratory sequelae. Singapore is a multiethnic Asian city-state situated on the equator. Dengue is endemic, with all 4 serotypes in circulation (DENV1, 2, 3, 4) [18], although the prevalence of past dengue infection was only 10.4% in a serologic survey of Singaporean children aged 1 to 17 years [19]. The case fatality rate was also low (<0.5%) [18], and the risk of severe dengue in children progressively decreased with increasing age [19].

METHODS

Study Design and Period

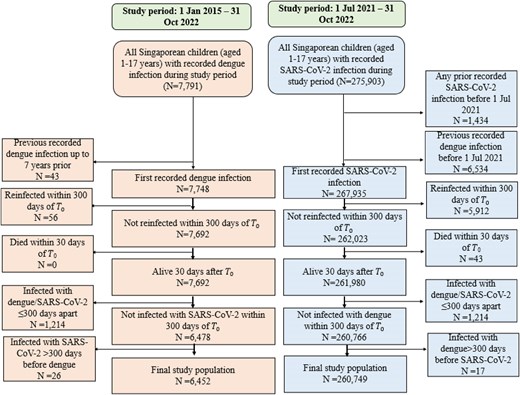

A retrospective population-based cohort study design was utilized to evaluate the risk of postacute sequelae following dengue infection vs COVID-19 in Singaporean children aged 1 to 17 years (citizens and permanent residents); as such, all Singaporean children who fulfilled inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the study. In Singapore, dengue and COVID-19 are legally notifiable to the Ministry of Health (MOH), with notified infections recorded in national registries. National registries for SARS-CoV-2 and dengue infection were hence utilized to construct 2 pediatric cohorts: one first infected with dengue infection over the enrollment period of 1 January 2015 to 31 October 2022 and the other with first SARS-CoV-2 infection over the enrollment period of 1 July 2021 to 31 October 2022. Individuals were excluded if they had previous SARS-CoV-2 infection or documented prior dengue infection, died within the first 30 days of the index date (T0; date of notification), or had documented reinfections within 300 days of T0. Individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 and dengue ≤300 days apart were excluded; if any had SARS-CoV-2 or dengue infection >300 days apart, only the first chronologic infection was included. Enrolled cases of dengue and COVID-19 were followed up to 300 days from T0 to assess occurrence of new-incident complications postinfection.

Exposure

Dengue infection was taken as the exposure and SARS-CoV-2 infection as the comparator, with dengue and SARS-CoV-2 infection status defined per notified records in the national COVID-19 and dengue registries. Confirmatory diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2 and dengue is widely available across health care settings in Singapore [20–23], with results requested at the point of notification to MOH. For SARS-CoV-2, diagnostic testing (polymerase chain reaction, rapid antigen testing) was mandatory for all individuals presenting with acute respiratory illness (ARI) at any health care provider, including public and private primary care clinics, and testing was free [20]. Similarly, rapid diagnostic tests for dengue are widely utilized in primary care [21], with additional tests (eg, polymerase chain reaction, enzyme-linked immunoassay) available in all hospitals [22, 23]. This enabled comprehensive capture of dengue and COVID-19 cases across health care settings (primary care as well as hospitals). During the period of overlap between SARS-CoV-2 and dengue transmission (2020–2022), a surge in dengue infections in 2020 coincided with a shift from DENV2 to DENV3 as well as social distancing measures imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic [24]. Social distancing measures suppressed community transmission of COVID-19 until the emergence of the Delta variant in April 2021; Omicron subsequently displaced Delta as the predominant strain from January 2022 onward [20]. Postacute sequelae following COVID-19 has been described following Delta and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 infection in Singaporean children and adults [5, 25–27].

Prespecified Outcomes

New-incident cardiovascular, neurologic, gastrointestinal, and autoimmune complications following SARS-CoV-2 and dengue infection were assessed during a follow-up period beginning 31 days post-T0 and ending 300 days post-T0. Occurrence of sequelae was assessed by prespecified ICD-10 diagnosis codes recorded in the national health care claims database (Mediclaims), referencing previous published work on postacute sequelae following COVID-19 and dengue in children [1–5, 8, 9, 28]. In Singapore, claims made against Medisave and Medshield–the medical savings and insurance schemes administered by the national government–for inpatient care and outpatient treatment at public and private healthcare providers are recorded in Mediclaims; participation in Medisave/Medishield is compulsory [29]. This enabled comprehensive capture of new-incident postacute sequelae across different health care settings and minimized loss to follow-up as coverage was universal. Any sequelae included a composite of any cardiovascular, neurologic, autoimmune, or gastrointestinal sequelae. Cardiovascular events included dysrhythmias, inflammatory heart disease, other cardiac disorders, and thrombotic disorders. Neurologic sequelae comprised cerebrovascular events, peripheral neuropathies, episodic disorders (headaches, seizures), movement disorders, sensory disorders (visual disturbances, hearing abnormalities, dysgeusia, anosmia), and other neurologic disorders (including chronic fatigue and malaise).

Autoimmune diseases were a composite of various autoimmune and autoinflammatory connective tissue disorders, such as, Kawasaki disease, systemic lupus, and vasculitis. Gastrointestinal outcomes consisted of appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and celiac disease. Additionally, while increased risk of respiratory sequelae has been documented following SARS-CoV-2 infection in children [1, 4, 5], dengue is not a respiratory virus; hence, increased risk of chronic respiratory sequelae vs COVID-19 was not expected. We therefore evaluated respiratory sequelae postinfection to see if expected reduction in respiratory sequelae after dengue vs SARS-CoV-2 was observed. Risks for the following conditions were individually evaluated: dysrhythmias, episodic disorders, movement disorders, other neurologic disorders, appendicitis, bronchitis, and asthma; other conditions were not individually evaluated due to the small number of new-incident cases in those categories. Relevant definitions and ICD-10 codes are detailed in the Supplementary material.

Covariates

Demographics (age, sex, ethnicity), comorbidities, and socioeconomic status (SES) were included as covariates. Age was treated as a continuous variable in analyses. Preexisting comorbidity burden was assessed per the national health care claims database (Mediclaims); comorbidity was defined as the presence of a pediatric complex chronic condition according to ICD-10 diagnosis codes [30]. Housing type was used as a surrogate marker of SES [23]. In Singapore, the majority (≥90%) stay in owner-occupied public housing, with purchase eligibility for more highly subsidized smaller flats dependent on monthly household income [31]. As clinical and sociodemographic information was derived from national databases maintained by the local MOH, data were complete. There were no missing data, and imputation of missing data was not necessary.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as proportion and percentage for categorical data and mean and SD for parametric continuous data; for skewed continuous data, median and IQR were reported. Risks of prespecified new-incident cardiovascular, neurologic, gastrointestinal, and autoimmune complications after dengue infection were estimated with SARS-CoV-2 infection as a comparator at 300 days from T0. For each new-incident complication, a subcohort was constructed of children without a history of the studied complication in the past 5 years. Baseline characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 and dengue groups were computed with standardized mean differences (SMDs). Differences in baseline characteristics between the COVID-19 and dengue cases were adjusted by overlap weighting to better account for outlying values [32, 33], with overlap weights computed as equal to the propensity score for individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 (the controls) and 1 – propensity score for dengue-infected cases, incorporating all available covariates (demographics, comorbidities, SES). SMD <0.1 was taken as the threshold for good covariate balance postweighting [34].

For approximation of risks, hazard ratios of incident complications between the SARS-CoV-2 and dengue groups were estimated by Cox regression, with overlap weights applied. Excess burdens (EBs) per 1000 individuals at 300 days of follow-up were estimated by the between-group differences between in estimated incidence rates of pre-specified complications. EBs were defined as the increase and decrease in incidence rates in dengue vs COVID-19 cases. Risks of new-incident complications after dengue infection were also compared against COVID-19 cases stratified by COVID-19 vaccination status (unvaccinated, vaccinated) via the national vaccination registry. COVID-19 vaccination with mRNA vaccines (mRNA-1273/BNT162b2) was rolled out for children aged 12 to 17 years from May 2021 [35]. In those aged 5 to 11 years, vaccination was rolled out in December 2021, with boosters recommended from October 2022 [36]. Vaccination for <5-year-olds started in October 2022 [37]. Subgroup analyses were also conducted comparing dengue with unvaccinated COVID-19 cases infected during Delta- and Omicron-predominant transmission.

Sensitivity Analyses

The robustness of our results was examined through various sensitivity analyses.

First, to account for the competing risk of death (ie, that death may have precluded occurrence of the primary outcome of interest, new-incident sequelae postinfection), risk for each new-incident sequela of interest was alternatively estimated by competing risks regression, taking death as a competing risk. Estimates were contrasted against those derived from the main analysis in which Cox regression was used.

Second, risk of negative-outcome controls (a composite outcome comprising injuries across various anatomic locations) was estimated between the SARS-CoV-2 and dengue groups by Cox regression (with overlap weights applied) and competing risks regression, taking death as a competing risk. The composite outcome, any injury, was taken as a negative outcome control [5] because postacute risk of injuries across various anatomic locations should not differ between children infected with SARS-CoV-2 and dengue, with injuries being attributed to trauma and accidents for which infection occurs outside the causal pathway.

Third, given public attention on long COVID [38], heightened awareness of prolonged sequelae following viral infection might have resulted in changes in health care utilization postinfection during the COVID-19 pandemic; moreover, the dengue and SARS-CoV-2 cohorts were not fully contemporaneous. As such, the risks of postacute sequelae in COVID-19 cases were additionally contrasted against a fully contemporaneous dengue cohort infected from 1 July 2021 to 31 October 2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The contemporaneous dengue cohort (1 July 2021–31 October 2022) was constructed with similar inclusion and exclusion criteria as the primary dengue cohort (1 January 2015–31 October 2022).

Finally, although our study focused on prespecified hypotheses and end points, to account for multiple comparisons, results with P values <.003 were considered additionally robust to correction for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction). A 95% CI that excluded 1 was considered evidence of statistical significance. Analyses were conducted in Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp).

Ethics Statement

This study met “review not required” criteria for national public health research under the Infectious Diseases Act, Singapore (1976). Institutional review board review and informed consent were waived under the stipulation of the act, and declaration of exemption was additionally sought and obtained from the board (NTU-IRB; reference IRB-2024-002). All data were anonymized prior to usage and analysis.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

There were 7791 documented dengue infections among Singaporean children aged 1 to 17 years from January 2015 to October 2022 and 275 903 SARS-CoV-2 infections from July 2021 to October 2022. After exclusion and inclusion criterion were met, 6452 children with documented dengue infection were compared against 260 749 COVID-19 cases (Figure 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of both groups are presented in Table 1. At baseline, the majority of children infected with dengue (61.1%, 3944/6452) were aged 12 to 17 years, as compared with only one-third of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 (34.3%, 89 345/260 749). The median age of dengue cases was 11 years (IQR = 9–15), while the median age of COVID-19 cases was 9 years (IQR = 5–13); <5% of the cohort had comorbidities (dengue, 2.6% [169/6452]; SARS-CoV-2, 3.4% [8949/260 749]). After weighting, differences in baseline characteristics were minimal with all SMDs <0.1. The majority had mild disease not requiring hospitalization: only 4.4% (285/6452) of dengue cases and 1.4% (3585/260 749) of COVID-19 cases required acute hospitalization. Almost two-thirds (57.7%, 150 565/260 749) of COVID-19 cases had completed a primary vaccination series prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection: 17.3% (45 195/260 749) had additionally received a COVID-19 booster while 42.3% (110 184/260 749) were unvaccinated at the point of infection.

Baseline Characteristics of Singaporean Children Aged 1–17 Years, Stratified by Dengue and SARS-CoV-2 Infection, With SMDs Before and After Overlap Weighting

| . | Baseline . | Postweighting . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Dengue (n = 6452) . | SARS-CoV-2 (n = 260 749) . | SMD . | Dengue . | SARS-CoV-2 . | SMDa . |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 1–4 | 464 (7.2) | 55 418 (21.3) | 0.41 | 459 (9.1) | 459 (9.1) | 0.00 |

| 5–11 | 2044 (31.7) | 115 986 (44.5) | 0.27 | 1958 (38.8) | 1958 (38.8) | 0.00 |

| 12–17 | 3944 (61.1) | 89 345 (34.3) | 0.56 | 2636 (52.2) | 2636 (52.2) | 0.00 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 3704 (57.4) | 135 285 (51.9) | 0.11 | 2840 (56.2) | 2840 (56.2) | 0.00 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Chinese | 4820 (74.7) | 173 632 (66.6) | 0.18 | 3717 (73.6) | 3717 (73.6) | 0.00 |

| Malay | 653 (10.1) | 52 643 (20.2) | 0.28 | 557 (11.0) | 557 (11.0) | 0.00 |

| Indian | 629 (9.7) | 25 645 (9.8) | 0.00 | 511 (10.1) | 511 (10.1) | 0.00 |

| Otherb | 350 (5.4) | 8829 (3.4) | 0.10 | 269 (5.3) | 269 (5.3) | 0.00 |

| Housing | ||||||

| Public, rooms | ||||||

| 1–2 | 148 (2.3) | 10 293 (3.9) | 0.10 | 123 (2.4) | 123 (2.4) | 0.00 |

| 3 | 623 (9.7) | 34 225 (13.1) | 0.11 | 530 (10.5) | 530 (10.5) | 0.00 |

| 4 | 1508 (23.4) | 97 253 (37.3) | 0.31 | 1306 (25.9) | 1306 (25.9) | 0.00 |

| 5 | 2801 (43.4) | 104 872 (40.2) | 0.06 | 2278 (45.1) | 2278 (45.1) | 0.00 |

| Private | 1372 (21.2) | 14 106 (5.4) | 0.51 | 816 (16.2) | 816 (16.2) | 0.00 |

| Comorbidity burden | ||||||

| ≥1 pediatric CCCc | 169 (2.6) | 8949 (3.4) | 0.05 | 140 (2.8) | 140 (2.8) | 0.00 |

| . | Baseline . | Postweighting . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Dengue (n = 6452) . | SARS-CoV-2 (n = 260 749) . | SMD . | Dengue . | SARS-CoV-2 . | SMDa . |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 1–4 | 464 (7.2) | 55 418 (21.3) | 0.41 | 459 (9.1) | 459 (9.1) | 0.00 |

| 5–11 | 2044 (31.7) | 115 986 (44.5) | 0.27 | 1958 (38.8) | 1958 (38.8) | 0.00 |

| 12–17 | 3944 (61.1) | 89 345 (34.3) | 0.56 | 2636 (52.2) | 2636 (52.2) | 0.00 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 3704 (57.4) | 135 285 (51.9) | 0.11 | 2840 (56.2) | 2840 (56.2) | 0.00 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Chinese | 4820 (74.7) | 173 632 (66.6) | 0.18 | 3717 (73.6) | 3717 (73.6) | 0.00 |

| Malay | 653 (10.1) | 52 643 (20.2) | 0.28 | 557 (11.0) | 557 (11.0) | 0.00 |

| Indian | 629 (9.7) | 25 645 (9.8) | 0.00 | 511 (10.1) | 511 (10.1) | 0.00 |

| Otherb | 350 (5.4) | 8829 (3.4) | 0.10 | 269 (5.3) | 269 (5.3) | 0.00 |

| Housing | ||||||

| Public, rooms | ||||||

| 1–2 | 148 (2.3) | 10 293 (3.9) | 0.10 | 123 (2.4) | 123 (2.4) | 0.00 |

| 3 | 623 (9.7) | 34 225 (13.1) | 0.11 | 530 (10.5) | 530 (10.5) | 0.00 |

| 4 | 1508 (23.4) | 97 253 (37.3) | 0.31 | 1306 (25.9) | 1306 (25.9) | 0.00 |

| 5 | 2801 (43.4) | 104 872 (40.2) | 0.06 | 2278 (45.1) | 2278 (45.1) | 0.00 |

| Private | 1372 (21.2) | 14 106 (5.4) | 0.51 | 816 (16.2) | 816 (16.2) | 0.00 |

| Comorbidity burden | ||||||

| ≥1 pediatric CCCc | 169 (2.6) | 8949 (3.4) | 0.05 | 140 (2.8) | 140 (2.8) | 0.00 |

Data are presented as No. (%).

Abbreviations: CCC, complex chronic condition; SMD, standardized mean difference.

aSMD after overlap weighting of SARS-CoV-2 and dengue cases, as weighted from original samples.

bIncludes individuals of other ethnicities or mixed ethnicities.

cComorbidity was defined as the presence of a pediatric CCC, according to ICD-10 diagnosis codes for cardiovascular, respiratory, kidney, gastrointestinal, neurologic, metabolic, congenital, and hematologic/immunologic conditions and malignancies.

Baseline Characteristics of Singaporean Children Aged 1–17 Years, Stratified by Dengue and SARS-CoV-2 Infection, With SMDs Before and After Overlap Weighting

| . | Baseline . | Postweighting . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Dengue (n = 6452) . | SARS-CoV-2 (n = 260 749) . | SMD . | Dengue . | SARS-CoV-2 . | SMDa . |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 1–4 | 464 (7.2) | 55 418 (21.3) | 0.41 | 459 (9.1) | 459 (9.1) | 0.00 |

| 5–11 | 2044 (31.7) | 115 986 (44.5) | 0.27 | 1958 (38.8) | 1958 (38.8) | 0.00 |

| 12–17 | 3944 (61.1) | 89 345 (34.3) | 0.56 | 2636 (52.2) | 2636 (52.2) | 0.00 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 3704 (57.4) | 135 285 (51.9) | 0.11 | 2840 (56.2) | 2840 (56.2) | 0.00 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Chinese | 4820 (74.7) | 173 632 (66.6) | 0.18 | 3717 (73.6) | 3717 (73.6) | 0.00 |

| Malay | 653 (10.1) | 52 643 (20.2) | 0.28 | 557 (11.0) | 557 (11.0) | 0.00 |

| Indian | 629 (9.7) | 25 645 (9.8) | 0.00 | 511 (10.1) | 511 (10.1) | 0.00 |

| Otherb | 350 (5.4) | 8829 (3.4) | 0.10 | 269 (5.3) | 269 (5.3) | 0.00 |

| Housing | ||||||

| Public, rooms | ||||||

| 1–2 | 148 (2.3) | 10 293 (3.9) | 0.10 | 123 (2.4) | 123 (2.4) | 0.00 |

| 3 | 623 (9.7) | 34 225 (13.1) | 0.11 | 530 (10.5) | 530 (10.5) | 0.00 |

| 4 | 1508 (23.4) | 97 253 (37.3) | 0.31 | 1306 (25.9) | 1306 (25.9) | 0.00 |

| 5 | 2801 (43.4) | 104 872 (40.2) | 0.06 | 2278 (45.1) | 2278 (45.1) | 0.00 |

| Private | 1372 (21.2) | 14 106 (5.4) | 0.51 | 816 (16.2) | 816 (16.2) | 0.00 |

| Comorbidity burden | ||||||

| ≥1 pediatric CCCc | 169 (2.6) | 8949 (3.4) | 0.05 | 140 (2.8) | 140 (2.8) | 0.00 |

| . | Baseline . | Postweighting . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Dengue (n = 6452) . | SARS-CoV-2 (n = 260 749) . | SMD . | Dengue . | SARS-CoV-2 . | SMDa . |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 1–4 | 464 (7.2) | 55 418 (21.3) | 0.41 | 459 (9.1) | 459 (9.1) | 0.00 |

| 5–11 | 2044 (31.7) | 115 986 (44.5) | 0.27 | 1958 (38.8) | 1958 (38.8) | 0.00 |

| 12–17 | 3944 (61.1) | 89 345 (34.3) | 0.56 | 2636 (52.2) | 2636 (52.2) | 0.00 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 3704 (57.4) | 135 285 (51.9) | 0.11 | 2840 (56.2) | 2840 (56.2) | 0.00 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Chinese | 4820 (74.7) | 173 632 (66.6) | 0.18 | 3717 (73.6) | 3717 (73.6) | 0.00 |

| Malay | 653 (10.1) | 52 643 (20.2) | 0.28 | 557 (11.0) | 557 (11.0) | 0.00 |

| Indian | 629 (9.7) | 25 645 (9.8) | 0.00 | 511 (10.1) | 511 (10.1) | 0.00 |

| Otherb | 350 (5.4) | 8829 (3.4) | 0.10 | 269 (5.3) | 269 (5.3) | 0.00 |

| Housing | ||||||

| Public, rooms | ||||||

| 1–2 | 148 (2.3) | 10 293 (3.9) | 0.10 | 123 (2.4) | 123 (2.4) | 0.00 |

| 3 | 623 (9.7) | 34 225 (13.1) | 0.11 | 530 (10.5) | 530 (10.5) | 0.00 |

| 4 | 1508 (23.4) | 97 253 (37.3) | 0.31 | 1306 (25.9) | 1306 (25.9) | 0.00 |

| 5 | 2801 (43.4) | 104 872 (40.2) | 0.06 | 2278 (45.1) | 2278 (45.1) | 0.00 |

| Private | 1372 (21.2) | 14 106 (5.4) | 0.51 | 816 (16.2) | 816 (16.2) | 0.00 |

| Comorbidity burden | ||||||

| ≥1 pediatric CCCc | 169 (2.6) | 8949 (3.4) | 0.05 | 140 (2.8) | 140 (2.8) | 0.00 |

Data are presented as No. (%).

Abbreviations: CCC, complex chronic condition; SMD, standardized mean difference.

aSMD after overlap weighting of SARS-CoV-2 and dengue cases, as weighted from original samples.

bIncludes individuals of other ethnicities or mixed ethnicities.

cComorbidity was defined as the presence of a pediatric CCC, according to ICD-10 diagnosis codes for cardiovascular, respiratory, kidney, gastrointestinal, neurologic, metabolic, congenital, and hematologic/immunologic conditions and malignancies.

Risks of Postacute Sequelae Following Pediatric Dengue Infection vs COVID-19

Overall

Risks of any prespecified new-incident sequelae and any cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, gastrointestinal, and autoimmune complications up to 300 days postinfection were estimated in the dengue and SARS-CoV-2 groups (Table 2). The mean follow-up time was 269.4 days (SD, 10.2) for dengue cases and 268.9 days (SD, 13.9) for COVID-19 cases. Among children infected with dengue, there was a significantly increased risk (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 2.92; 95% CI, 1.18–7.18; P = .002) of gastrointestinal sequelae as a composite outcome when compared against COVID-19 cases. Specifically, increased risk of appendicitis (aHR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.36–8.99; P < .001) was noted in children infected with dengue when contrasted against SARS-CoV-2 infection. The proportion of children who developed appendicitis 31 to 300 days following dengue infection was, however, modest (0.1%, 7/6421). Among the 7 new-incident cases of appendicitis recorded after dengue infection, the median age was 14 years (IQR, 9–17), 3 were female and 4 were male, and none had preexisting comorbidities. The median time from T0 (ie, the index date of dengue infection) to occurrence of appendicitis was 158 days (IQR, 62–223). In contrast, only 0.03% (83/260 251) of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 went on to develop appendicitis within 31 to 300 days of infection.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios and Excess Burdens of Prespecified Postacute Sequelae in Pediatric Dengue vs COVID-19 Cases

| . | . | . | Dengue Cases, No. (%)a . | COVID-19 Cases, No. (%)a . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Outcome . | aHR (95% CI)b . | EB Weighted per 1000 Persons (95% CI) . | Overall . | With Outcome . | Overall . | With Outcome . |

| Any multisystemic sequelae | 0.92 (.62, 1.36) | −0.46 (−3.45, 2.54) | 6105 | 29 (0.5) | 247 950 | 1810 (0.7) |

| Any diagnosis | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 0.56 (.12, 2.77) | −0.18 (−.92, .55) | 6400 | 2 (0.0) | 260 324 | 61 (0.0) |

| Neurologic | 1.46 (.74, 2.91) | 0.53 (−.98, 2.04) | 6371 | 10 (0.2) | 258 492 | 296 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2.92 (1.18, 7.18)** | 0.76 (−.36, 1.89) | 6413 | 7 (0.1) | 260 011 | 107 (0.0) |

| Autoimmunec | 2.52 (.60, 10.51) | 0.22 (−.42, .86) | 6436 | 2 (0.0) | 260 094 | 67 (0.0) |

| Respiratory | 0.78 (.41, 1.48) | −0.51 (−2.35, 1.33) | 6324 | 10 (0.2) | 252 406 | 1143 (0.5) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosesd | ||||||

| Dysrhythmia | 0.44 (.06, 3.28) | −0.13 (−.66, .40) | 6402 | 1 (0.0) | 260 390 | 52 (0.0) |

| Neurologic diagnosese | ||||||

| Episodic disordersf | 1.46 (.46, 4.65) | 0.20 (−.72, 1.12) | 6427 | 4 (0.1) | 259 886 | 104 (0.0) |

| Extrapyramidal/movement disorders | 3.71 (.71, 19.30) | 0.23 (−.34, .79) | 6445 | 2 (0.0) | 260 561 | 18 (0.0) |

| Othersg | 1.39 (.48, 3.97) | 0.19 (−.78, 1.16) | 6417 | 4 (0.1) | 259 962 | 135 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal diagnosesh | ||||||

| Appendicitis | 3.50 (1.36, 8.99)*** | 0.83 (−.27, 1.93) | 6421 | 7 (0.1) | 260 251 | 83 (0.0) |

| Respiratory diagnosesi | ||||||

| Bronchitis | 0.85 (.40, 1.82) | −0.24 (−1.81, 1.32) | 6384 | 7 (0.1) | 257 291 | 786 (0.3) |

| Asthma | 1.46 (.63, 3.37) | 0.32 (−.86, 1.50) | 6416 | 6 (0.1) | 258 812 | 369 (0.1) |

| . | . | . | Dengue Cases, No. (%)a . | COVID-19 Cases, No. (%)a . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Outcome . | aHR (95% CI)b . | EB Weighted per 1000 Persons (95% CI) . | Overall . | With Outcome . | Overall . | With Outcome . |

| Any multisystemic sequelae | 0.92 (.62, 1.36) | −0.46 (−3.45, 2.54) | 6105 | 29 (0.5) | 247 950 | 1810 (0.7) |

| Any diagnosis | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 0.56 (.12, 2.77) | −0.18 (−.92, .55) | 6400 | 2 (0.0) | 260 324 | 61 (0.0) |

| Neurologic | 1.46 (.74, 2.91) | 0.53 (−.98, 2.04) | 6371 | 10 (0.2) | 258 492 | 296 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2.92 (1.18, 7.18)** | 0.76 (−.36, 1.89) | 6413 | 7 (0.1) | 260 011 | 107 (0.0) |

| Autoimmunec | 2.52 (.60, 10.51) | 0.22 (−.42, .86) | 6436 | 2 (0.0) | 260 094 | 67 (0.0) |

| Respiratory | 0.78 (.41, 1.48) | −0.51 (−2.35, 1.33) | 6324 | 10 (0.2) | 252 406 | 1143 (0.5) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosesd | ||||||

| Dysrhythmia | 0.44 (.06, 3.28) | −0.13 (−.66, .40) | 6402 | 1 (0.0) | 260 390 | 52 (0.0) |

| Neurologic diagnosese | ||||||

| Episodic disordersf | 1.46 (.46, 4.65) | 0.20 (−.72, 1.12) | 6427 | 4 (0.1) | 259 886 | 104 (0.0) |

| Extrapyramidal/movement disorders | 3.71 (.71, 19.30) | 0.23 (−.34, .79) | 6445 | 2 (0.0) | 260 561 | 18 (0.0) |

| Othersg | 1.39 (.48, 3.97) | 0.19 (−.78, 1.16) | 6417 | 4 (0.1) | 259 962 | 135 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal diagnosesh | ||||||

| Appendicitis | 3.50 (1.36, 8.99)*** | 0.83 (−.27, 1.93) | 6421 | 7 (0.1) | 260 251 | 83 (0.0) |

| Respiratory diagnosesi | ||||||

| Bronchitis | 0.85 (.40, 1.82) | −0.24 (−1.81, 1.32) | 6384 | 7 (0.1) | 257 291 | 786 (0.3) |

| Asthma | 1.46 (.63, 3.37) | 0.32 (−.86, 1.50) | 6416 | 6 (0.1) | 258 812 | 369 (0.1) |

aHR >1 denotes higher risk of a composite or individual new-incident cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, or autoimmune diagnosis among dengue vs COVID-19 cases. EB >0 denotes excess burden in a composite or individual new-incident cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, or autoimmune diagnosis among dengue vs COVID-19 cases. Results with P values <.003 were considered robust to correction for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction).

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; EB, excess burden.

aNumbers in each subcohort for each diagnosis do not add up to the original number of dengue and COVID-19 cases because a subcohort of individuals without a history of the diagnosis in the past 5 years was constructed for estimation of risks for each new-incident diagnosis.

bEach model is overlap weighted and regression adjusted by demographic characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity), socioeconomic status (housing type), and comorbidities.

cIndividual autoimmune diagnoses were not evaluated because of the small number of new-incident autoimmune diagnoses, given their rarity.

dInflammatory heart disorders, other cardiac disorders, and thrombotic disorders were not individually evaluated due to the small number of new-incident cases.

eCerebrovascular diseases, peripheral neuropathies, and sensory disorders were not individually evaluated due to the small number of new-incident cases.

fEpisodic disorders included headache disorders, epilepsy, and seizures.

gOther neurologic disorders included dizziness, sleep disorders, somnolence, malaise and chronic fatigue, Guillain-Barre syndrome, encephalitis/encephalopathy, and transverse myelitis.

hAlthough cases of new-incident celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease were included in the composite of gastrointestinal diagnoses, a separate category for these diagnoses was not computed given the small number of incident cases.

iWhile cases of new-incident bronchiolitis were included in the composite of respiratory diagnoses, a separate category for these diagnoses was not computed given the small number of incident cases.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios and Excess Burdens of Prespecified Postacute Sequelae in Pediatric Dengue vs COVID-19 Cases

| . | . | . | Dengue Cases, No. (%)a . | COVID-19 Cases, No. (%)a . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Outcome . | aHR (95% CI)b . | EB Weighted per 1000 Persons (95% CI) . | Overall . | With Outcome . | Overall . | With Outcome . |

| Any multisystemic sequelae | 0.92 (.62, 1.36) | −0.46 (−3.45, 2.54) | 6105 | 29 (0.5) | 247 950 | 1810 (0.7) |

| Any diagnosis | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 0.56 (.12, 2.77) | −0.18 (−.92, .55) | 6400 | 2 (0.0) | 260 324 | 61 (0.0) |

| Neurologic | 1.46 (.74, 2.91) | 0.53 (−.98, 2.04) | 6371 | 10 (0.2) | 258 492 | 296 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2.92 (1.18, 7.18)** | 0.76 (−.36, 1.89) | 6413 | 7 (0.1) | 260 011 | 107 (0.0) |

| Autoimmunec | 2.52 (.60, 10.51) | 0.22 (−.42, .86) | 6436 | 2 (0.0) | 260 094 | 67 (0.0) |

| Respiratory | 0.78 (.41, 1.48) | −0.51 (−2.35, 1.33) | 6324 | 10 (0.2) | 252 406 | 1143 (0.5) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosesd | ||||||

| Dysrhythmia | 0.44 (.06, 3.28) | −0.13 (−.66, .40) | 6402 | 1 (0.0) | 260 390 | 52 (0.0) |

| Neurologic diagnosese | ||||||

| Episodic disordersf | 1.46 (.46, 4.65) | 0.20 (−.72, 1.12) | 6427 | 4 (0.1) | 259 886 | 104 (0.0) |

| Extrapyramidal/movement disorders | 3.71 (.71, 19.30) | 0.23 (−.34, .79) | 6445 | 2 (0.0) | 260 561 | 18 (0.0) |

| Othersg | 1.39 (.48, 3.97) | 0.19 (−.78, 1.16) | 6417 | 4 (0.1) | 259 962 | 135 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal diagnosesh | ||||||

| Appendicitis | 3.50 (1.36, 8.99)*** | 0.83 (−.27, 1.93) | 6421 | 7 (0.1) | 260 251 | 83 (0.0) |

| Respiratory diagnosesi | ||||||

| Bronchitis | 0.85 (.40, 1.82) | −0.24 (−1.81, 1.32) | 6384 | 7 (0.1) | 257 291 | 786 (0.3) |

| Asthma | 1.46 (.63, 3.37) | 0.32 (−.86, 1.50) | 6416 | 6 (0.1) | 258 812 | 369 (0.1) |

| . | . | . | Dengue Cases, No. (%)a . | COVID-19 Cases, No. (%)a . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Outcome . | aHR (95% CI)b . | EB Weighted per 1000 Persons (95% CI) . | Overall . | With Outcome . | Overall . | With Outcome . |

| Any multisystemic sequelae | 0.92 (.62, 1.36) | −0.46 (−3.45, 2.54) | 6105 | 29 (0.5) | 247 950 | 1810 (0.7) |

| Any diagnosis | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 0.56 (.12, 2.77) | −0.18 (−.92, .55) | 6400 | 2 (0.0) | 260 324 | 61 (0.0) |

| Neurologic | 1.46 (.74, 2.91) | 0.53 (−.98, 2.04) | 6371 | 10 (0.2) | 258 492 | 296 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2.92 (1.18, 7.18)** | 0.76 (−.36, 1.89) | 6413 | 7 (0.1) | 260 011 | 107 (0.0) |

| Autoimmunec | 2.52 (.60, 10.51) | 0.22 (−.42, .86) | 6436 | 2 (0.0) | 260 094 | 67 (0.0) |

| Respiratory | 0.78 (.41, 1.48) | −0.51 (−2.35, 1.33) | 6324 | 10 (0.2) | 252 406 | 1143 (0.5) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosesd | ||||||

| Dysrhythmia | 0.44 (.06, 3.28) | −0.13 (−.66, .40) | 6402 | 1 (0.0) | 260 390 | 52 (0.0) |

| Neurologic diagnosese | ||||||

| Episodic disordersf | 1.46 (.46, 4.65) | 0.20 (−.72, 1.12) | 6427 | 4 (0.1) | 259 886 | 104 (0.0) |

| Extrapyramidal/movement disorders | 3.71 (.71, 19.30) | 0.23 (−.34, .79) | 6445 | 2 (0.0) | 260 561 | 18 (0.0) |

| Othersg | 1.39 (.48, 3.97) | 0.19 (−.78, 1.16) | 6417 | 4 (0.1) | 259 962 | 135 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal diagnosesh | ||||||

| Appendicitis | 3.50 (1.36, 8.99)*** | 0.83 (−.27, 1.93) | 6421 | 7 (0.1) | 260 251 | 83 (0.0) |

| Respiratory diagnosesi | ||||||

| Bronchitis | 0.85 (.40, 1.82) | −0.24 (−1.81, 1.32) | 6384 | 7 (0.1) | 257 291 | 786 (0.3) |

| Asthma | 1.46 (.63, 3.37) | 0.32 (−.86, 1.50) | 6416 | 6 (0.1) | 258 812 | 369 (0.1) |

aHR >1 denotes higher risk of a composite or individual new-incident cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, or autoimmune diagnosis among dengue vs COVID-19 cases. EB >0 denotes excess burden in a composite or individual new-incident cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, or autoimmune diagnosis among dengue vs COVID-19 cases. Results with P values <.003 were considered robust to correction for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction).

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; EB, excess burden.

aNumbers in each subcohort for each diagnosis do not add up to the original number of dengue and COVID-19 cases because a subcohort of individuals without a history of the diagnosis in the past 5 years was constructed for estimation of risks for each new-incident diagnosis.

bEach model is overlap weighted and regression adjusted by demographic characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity), socioeconomic status (housing type), and comorbidities.

cIndividual autoimmune diagnoses were not evaluated because of the small number of new-incident autoimmune diagnoses, given their rarity.

dInflammatory heart disorders, other cardiac disorders, and thrombotic disorders were not individually evaluated due to the small number of new-incident cases.

eCerebrovascular diseases, peripheral neuropathies, and sensory disorders were not individually evaluated due to the small number of new-incident cases.

fEpisodic disorders included headache disorders, epilepsy, and seizures.

gOther neurologic disorders included dizziness, sleep disorders, somnolence, malaise and chronic fatigue, Guillain-Barre syndrome, encephalitis/encephalopathy, and transverse myelitis.

hAlthough cases of new-incident celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease were included in the composite of gastrointestinal diagnoses, a separate category for these diagnoses was not computed given the small number of incident cases.

iWhile cases of new-incident bronchiolitis were included in the composite of respiratory diagnoses, a separate category for these diagnoses was not computed given the small number of incident cases.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Stratified by Vaccination

When risks of new-incident complications after dengue infection were compared against unvaccinated COVID-19 cases, lower risk (aHR, 0.42; 95% CI, .29–.61; P < .001) and EB (−6.50; 95% CI, −9.80 to –3.20) of any sequelae, as well as lower risk (aHR, 0.17; 95% CI, .09–.31; P < .001) and EB (−7.85; 95% CI, −10.56 to –5.14) of respiratory sequelae but higher risk of gastrointestinal sequelae (aHR, 3.84; 95% CI, 1.58–9.29; P < .002), were observed in children infected with dengue (Table 3). Similarly, increased risk (aHR, 5.99; 95% CI, 2.21–16.23; P < .001) and EB (0.82; 95% CI, .05–1.68) of appendicitis but lower risk (aHR, 0.16; 95% CI, .07–.33; P < .001) and EB (−5.72; 95% CI, −7.99 to –3.44) of bronchitis were observed in children infected with dengue as compared with unvaccinated COVID-19 cases. Elevated risk of appendicitis (aHR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.01–5.63; P = .02) was still observed in children infected with dengue when compared with vaccine-breakthrough COVID-19 cases (Supplementary Table 1).

Adjusted Hazard Ratios and Excess Burdens of Prespecified Postacute Sequelae in Pediatric Dengue vs Unvaccinated COVID-19 Cases

| . | . | . | Dengue Cases, No. (%)a . | Unvaccinated COVID-19 Cases, No. (%)a . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Outcome . | aHR (95% CI)b . | EB Weighted per 1000 Persons (95% CI) . | Overall . | With Outcome . | Overall . | With Outcome . |

| Any multisystemic sequelae | 0.42 (.29, .61)*** | −6.50 (−9.80, –3.20) | 6105 | 29 (0.5) | 102 364 | 1140 (1.1) |

| Any diagnosis | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 2.16 (.46, 10.16) | 0.18 (−.39, 0.75) | 6400 | 2 (0.0) | 110 039 | 16 (0.0) |

| Neurologic | 1.81 (.93, 3.53) | 0.72 (−.57, 2.01) | 6371 | 10 (0.2) | 109 355 | 96 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 3.84 (1.58, 9.29)** | 0.73 (−.18, 1.63) | 6413 | 7 (0.1) | 109 952 | 27 (0.0) |

| Autoimmunec | 0.79 (.18, 3.42) | −0.08 (−.74, 0.59) | 6436 | 2 (0.0) | 109 735 | 38 (0.0) |

| Respiratory | 0.17 (.09, .31)*** | −7.85 (−10.56, –5.14) | 6324 | 10 (0.2) | 103 933 | 984 (0.9) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosesd | ||||||

| Dysrhythmia | 1.59 (.21, 12.24) | 0.06 (−.36, 0.48) | 6402 | 1 (0.0) | 110 070 | 14 (0.0) |

| Neurological diagnosese | ||||||

| Episodic disordersf | 2.24 (.78, 6.45) | 0.34 (−.42, 1.11) | 6427 | 4 (0.1) | 109 942 | 30 (0.0) |

| Extrapyramidal/movement disorders | 3.82 (.82, 17.92) | 0.24 (−.28, 0.76) | 6445 | 2 (0.0) | 110 074 | 9 (0.0) |

| Otherg | 1.65 (.57, 4.80) | 0.26 (−.58, 1.09) | 6417 | 4 (0.1) | 109 982 | 37 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal diagnosesh | ||||||

| Appendicitis | 5.99 (2.21, 16.23)*** | 0.82 (.05, 1.68) | 6421 | 7 (0.1) | 110 095 | 15 (0.0) |

| Respiratory diagnosesi | ||||||

| Bronchitis | 0.16 (.07, .33)*** | −5.72 (−7.99, –3.44) | 6384 | 7 (0.1) | 107 821 | 704 (0.7) |

| Asthma | 0.45 (.20, 1.02) | −1.18 (−2.61, .26) | 6416 | 6 (0.1) | 109 269 | 265 (0.2) |

| . | . | . | Dengue Cases, No. (%)a . | Unvaccinated COVID-19 Cases, No. (%)a . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Outcome . | aHR (95% CI)b . | EB Weighted per 1000 Persons (95% CI) . | Overall . | With Outcome . | Overall . | With Outcome . |

| Any multisystemic sequelae | 0.42 (.29, .61)*** | −6.50 (−9.80, –3.20) | 6105 | 29 (0.5) | 102 364 | 1140 (1.1) |

| Any diagnosis | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 2.16 (.46, 10.16) | 0.18 (−.39, 0.75) | 6400 | 2 (0.0) | 110 039 | 16 (0.0) |

| Neurologic | 1.81 (.93, 3.53) | 0.72 (−.57, 2.01) | 6371 | 10 (0.2) | 109 355 | 96 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 3.84 (1.58, 9.29)** | 0.73 (−.18, 1.63) | 6413 | 7 (0.1) | 109 952 | 27 (0.0) |

| Autoimmunec | 0.79 (.18, 3.42) | −0.08 (−.74, 0.59) | 6436 | 2 (0.0) | 109 735 | 38 (0.0) |

| Respiratory | 0.17 (.09, .31)*** | −7.85 (−10.56, –5.14) | 6324 | 10 (0.2) | 103 933 | 984 (0.9) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosesd | ||||||

| Dysrhythmia | 1.59 (.21, 12.24) | 0.06 (−.36, 0.48) | 6402 | 1 (0.0) | 110 070 | 14 (0.0) |

| Neurological diagnosese | ||||||

| Episodic disordersf | 2.24 (.78, 6.45) | 0.34 (−.42, 1.11) | 6427 | 4 (0.1) | 109 942 | 30 (0.0) |

| Extrapyramidal/movement disorders | 3.82 (.82, 17.92) | 0.24 (−.28, 0.76) | 6445 | 2 (0.0) | 110 074 | 9 (0.0) |

| Otherg | 1.65 (.57, 4.80) | 0.26 (−.58, 1.09) | 6417 | 4 (0.1) | 109 982 | 37 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal diagnosesh | ||||||

| Appendicitis | 5.99 (2.21, 16.23)*** | 0.82 (.05, 1.68) | 6421 | 7 (0.1) | 110 095 | 15 (0.0) |

| Respiratory diagnosesi | ||||||

| Bronchitis | 0.16 (.07, .33)*** | −5.72 (−7.99, –3.44) | 6384 | 7 (0.1) | 107 821 | 704 (0.7) |

| Asthma | 0.45 (.20, 1.02) | −1.18 (−2.61, .26) | 6416 | 6 (0.1) | 109 269 | 265 (0.2) |

aHR >1 denotes higher risk of a composite or individual new-incident cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, or autoimmune diagnosis among dengue vs unvaccinated COVID-19 cases. EB >0 denotes excess burden in a composite or individual new-incident cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, or autoimmune diagnosis among dengue vs unvaccinated COVID-19 cases. Results with P values <.003 were considered robust to correction for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction).

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; EB, excess burden.

aEach model is overlap weighted and regression adjusted by demographic characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity), socioeconomic status (housing type), and comorbidities.

bNumbers in each subcohort for each diagnosis do not add up to the original number of dengue and COVID-19 cases because a subcohort of individuals without a history of the diagnosis in the past 5 years was constructed for estimation of risks for each new-incident diagnosis.

cIndividual autoimmune diagnoses were not evaluated because of the small number of new-incident autoimmune diagnoses, given their rarity.

dInflammatory heart disorders, other cardiac disorders, and thrombotic disorders were not individually evaluated due to the small number of new-incident cases.

eCerebrovascular diseases, peripheral neuropathies, and sensory disorders were not individually evaluated due to the small number of new-incident cases.

fEpisodic disorders included headache disorders, epilepsy, and seizures.

gOther neurologic disorders included dizziness, sleep disorders, somnolence, malaise and chronic fatigue, Guillain-Barre syndrome, encephalitis/encephalopathy, and transverse myelitis.

hAlthough cases of new-incident celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease were included in the composite of gastrointestinal diagnoses, a separate category for these diagnoses was not computed given the small number of incident cases.

iAlthough cases of new-incident bronchiolitis were included in the composite of respiratory diagnoses, a separate category for these diagnoses was not computed given the small number of incident cases.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios and Excess Burdens of Prespecified Postacute Sequelae in Pediatric Dengue vs Unvaccinated COVID-19 Cases

| . | . | . | Dengue Cases, No. (%)a . | Unvaccinated COVID-19 Cases, No. (%)a . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Outcome . | aHR (95% CI)b . | EB Weighted per 1000 Persons (95% CI) . | Overall . | With Outcome . | Overall . | With Outcome . |

| Any multisystemic sequelae | 0.42 (.29, .61)*** | −6.50 (−9.80, –3.20) | 6105 | 29 (0.5) | 102 364 | 1140 (1.1) |

| Any diagnosis | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 2.16 (.46, 10.16) | 0.18 (−.39, 0.75) | 6400 | 2 (0.0) | 110 039 | 16 (0.0) |

| Neurologic | 1.81 (.93, 3.53) | 0.72 (−.57, 2.01) | 6371 | 10 (0.2) | 109 355 | 96 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 3.84 (1.58, 9.29)** | 0.73 (−.18, 1.63) | 6413 | 7 (0.1) | 109 952 | 27 (0.0) |

| Autoimmunec | 0.79 (.18, 3.42) | −0.08 (−.74, 0.59) | 6436 | 2 (0.0) | 109 735 | 38 (0.0) |

| Respiratory | 0.17 (.09, .31)*** | −7.85 (−10.56, –5.14) | 6324 | 10 (0.2) | 103 933 | 984 (0.9) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosesd | ||||||

| Dysrhythmia | 1.59 (.21, 12.24) | 0.06 (−.36, 0.48) | 6402 | 1 (0.0) | 110 070 | 14 (0.0) |

| Neurological diagnosese | ||||||

| Episodic disordersf | 2.24 (.78, 6.45) | 0.34 (−.42, 1.11) | 6427 | 4 (0.1) | 109 942 | 30 (0.0) |

| Extrapyramidal/movement disorders | 3.82 (.82, 17.92) | 0.24 (−.28, 0.76) | 6445 | 2 (0.0) | 110 074 | 9 (0.0) |

| Otherg | 1.65 (.57, 4.80) | 0.26 (−.58, 1.09) | 6417 | 4 (0.1) | 109 982 | 37 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal diagnosesh | ||||||

| Appendicitis | 5.99 (2.21, 16.23)*** | 0.82 (.05, 1.68) | 6421 | 7 (0.1) | 110 095 | 15 (0.0) |

| Respiratory diagnosesi | ||||||

| Bronchitis | 0.16 (.07, .33)*** | −5.72 (−7.99, –3.44) | 6384 | 7 (0.1) | 107 821 | 704 (0.7) |

| Asthma | 0.45 (.20, 1.02) | −1.18 (−2.61, .26) | 6416 | 6 (0.1) | 109 269 | 265 (0.2) |

| . | . | . | Dengue Cases, No. (%)a . | Unvaccinated COVID-19 Cases, No. (%)a . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Outcome . | aHR (95% CI)b . | EB Weighted per 1000 Persons (95% CI) . | Overall . | With Outcome . | Overall . | With Outcome . |

| Any multisystemic sequelae | 0.42 (.29, .61)*** | −6.50 (−9.80, –3.20) | 6105 | 29 (0.5) | 102 364 | 1140 (1.1) |

| Any diagnosis | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 2.16 (.46, 10.16) | 0.18 (−.39, 0.75) | 6400 | 2 (0.0) | 110 039 | 16 (0.0) |

| Neurologic | 1.81 (.93, 3.53) | 0.72 (−.57, 2.01) | 6371 | 10 (0.2) | 109 355 | 96 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 3.84 (1.58, 9.29)** | 0.73 (−.18, 1.63) | 6413 | 7 (0.1) | 109 952 | 27 (0.0) |

| Autoimmunec | 0.79 (.18, 3.42) | −0.08 (−.74, 0.59) | 6436 | 2 (0.0) | 109 735 | 38 (0.0) |

| Respiratory | 0.17 (.09, .31)*** | −7.85 (−10.56, –5.14) | 6324 | 10 (0.2) | 103 933 | 984 (0.9) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosesd | ||||||

| Dysrhythmia | 1.59 (.21, 12.24) | 0.06 (−.36, 0.48) | 6402 | 1 (0.0) | 110 070 | 14 (0.0) |

| Neurological diagnosese | ||||||

| Episodic disordersf | 2.24 (.78, 6.45) | 0.34 (−.42, 1.11) | 6427 | 4 (0.1) | 109 942 | 30 (0.0) |

| Extrapyramidal/movement disorders | 3.82 (.82, 17.92) | 0.24 (−.28, 0.76) | 6445 | 2 (0.0) | 110 074 | 9 (0.0) |

| Otherg | 1.65 (.57, 4.80) | 0.26 (−.58, 1.09) | 6417 | 4 (0.1) | 109 982 | 37 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal diagnosesh | ||||||

| Appendicitis | 5.99 (2.21, 16.23)*** | 0.82 (.05, 1.68) | 6421 | 7 (0.1) | 110 095 | 15 (0.0) |

| Respiratory diagnosesi | ||||||

| Bronchitis | 0.16 (.07, .33)*** | −5.72 (−7.99, –3.44) | 6384 | 7 (0.1) | 107 821 | 704 (0.7) |

| Asthma | 0.45 (.20, 1.02) | −1.18 (−2.61, .26) | 6416 | 6 (0.1) | 109 269 | 265 (0.2) |

aHR >1 denotes higher risk of a composite or individual new-incident cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, or autoimmune diagnosis among dengue vs unvaccinated COVID-19 cases. EB >0 denotes excess burden in a composite or individual new-incident cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, or autoimmune diagnosis among dengue vs unvaccinated COVID-19 cases. Results with P values <.003 were considered robust to correction for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction).

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; EB, excess burden.

aEach model is overlap weighted and regression adjusted by demographic characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity), socioeconomic status (housing type), and comorbidities.

bNumbers in each subcohort for each diagnosis do not add up to the original number of dengue and COVID-19 cases because a subcohort of individuals without a history of the diagnosis in the past 5 years was constructed for estimation of risks for each new-incident diagnosis.

cIndividual autoimmune diagnoses were not evaluated because of the small number of new-incident autoimmune diagnoses, given their rarity.

dInflammatory heart disorders, other cardiac disorders, and thrombotic disorders were not individually evaluated due to the small number of new-incident cases.

eCerebrovascular diseases, peripheral neuropathies, and sensory disorders were not individually evaluated due to the small number of new-incident cases.

fEpisodic disorders included headache disorders, epilepsy, and seizures.

gOther neurologic disorders included dizziness, sleep disorders, somnolence, malaise and chronic fatigue, Guillain-Barre syndrome, encephalitis/encephalopathy, and transverse myelitis.

hAlthough cases of new-incident celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease were included in the composite of gastrointestinal diagnoses, a separate category for these diagnoses was not computed given the small number of incident cases.

iAlthough cases of new-incident bronchiolitis were included in the composite of respiratory diagnoses, a separate category for these diagnoses was not computed given the small number of incident cases.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Stratified by SARS-CoV-2 Variant

Lower risk (aHR, 0.40; 95% CI, .27–.58; P < .001) and EB (−7.03; 95% CI, −10.40 to –3.66) of any sequelae, as well as lower risk (aHR, 0.16; 95% CI, .08–.29; P < .001) and EB (−8.50; 95% CI, −11.30 to –5.70) of respiratory sequelae but higher risk of gastrointestinal sequelae (aHR, 4.11; 95% CI, 1.65–10.24; P < .001), were observed in children infected with dengue as compared with unvaccinated COVID-19 cases infected during Omicron-predominant transmission (Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, increased risk (aHR, 6.56; 95% CI, 2.28–18.89; P < .001) of appendicitis but lower risk (aHR, 0.15; 95% CI, .07–.31; P < .001) and EB (−6.15; 95% CI, −8.50 to –3.80) of bronchitis were observed in children infected with dengue when compared with unvaccinated COVID-19 cases during the Omicron-predominant period. Risks of postacute sequelae following dengue infection were not significantly different from those observed in unvaccinated COVID-19 cases infected during Delta-predominant transmission.

Sensitivity Analyses

Use of competing risks regression did not significantly skew risk estimates (Supplementary Table 3). Increased risk of appendicitis (aHR, 3.36; 95% CI, 1.05–10.79; P = .03) was still observed in contemporaneous dengue cases infected from 2021 to 2022 as compared with COVID-19 cases (Supplementary Table 4). No significantly increased risk of negative-outcome controls (injuries) was observed in cases of dengue infection as compared with COVID-19 (Supplementary Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Lower overall risk of postacute complications was observed following dengue infection in a national population-based cohort of Singaporean children aged 1 to 7 years when compared against COVID-19 cases—with the exception of appendicitis, for which higher risk was consistently reported 31 to 300 days after dengue infection when contrasted against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

These results substantially differ from our findings in the adult Singaporean population, in which increased risk of any postacute cardiovascular and neurologic sequelae persisted up to 300 days following dengue infection when compared against COVID-19 [17]. Long COVID in children is less well characterized as compared with adults, with more modest estimates of prevalence [39]. Postinfectious sequelae following dengue infection in children remains even less well characterized and limited to small cohorts and case reports [8, 9, 40]. In a cohort of Vietnamese children followed for 3 months after febrile illness, primarily acute dengue, a broad spectrum of postviral symptoms was reported [8], with close to half of cases reporting >1 postacute symptom, though occurrence of individual symptoms was low. In a Colombian pediatric cohort (N = 135) with nonsevere dengue, 14% to 18% of children demonstrated gastrointestinal symptoms at 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month follow-up, though these proportions were not significantly higher than controls [9]. Uncertainty exists regarding the extent and spectrum of chronic symptoms after dengue infection in children and the comparative burden of postacute symptoms following dengue infection in children vs other viral infections. In an adult cohort comprising dengue-infected cases as well as cases of non–SARS-CoV-2 respiratory viral infection, a greater proportion of the dengue cohort (18.0%) experienced persistent symptoms at 3-month follow-up; in contrast, only 14.6% of the cohort with respiratory viral infection demonstrated persistence of chronic symptoms [10]. Lower risk of chronic sequelae following dengue infection vs respiratory viral infection in children but not in adults may stem from lesser comorbidity burden and reduced severity of dengue in children. Risk of severe dengue increases with overall age [41]: in an adult population, increased risks of postacute sequelae in dengue survivors vs COVID-19 survivors were generally observed in those aged ≥65 years [17]. More modest estimates of postacute sequelae are reassuring, particularly in tropical countries where overlapping dengue and COVID-19 outbreaks may increase burden and severity of disease [42]. Lower risk of respiratory sequelae was observed in children infected with dengue when contrasted against unvaccinated COVID-19 cases but not vaccine-breakthrough COVID-19 cases, thereby highlighting the protective effect of COVID-19 vaccination against chronic respiratory sequelae following SARS-CoV-2 infection [43]. Dengue vaccine trials in children have demonstrated protection against acute infection [44]; cost-effectiveness estimates of vaccination strategies should also take into account the added burden of postinfectious sequelae.

Higher risk of gastrointestinal sequelae, specifically appendicitis, was consistently reported up to 300 days after dengue infection in children when contrasted against COVID-19. In a retrospective population-based Taiwanese study that included 7775 children infected with dengue and 31 100 matched controls without dengue, increased risk of appendicitis (hazard ratio, 1.63) was observed up to 1 year after dengue in children but not adults [28]. Increased incidence of appendicitis and other gastrointestinal diagnoses following COVID-19 has been observed in several pediatric cohorts [45, 46], possibly attributed to the enteric persistence of viral infection in the lymphoid tissue of the appendix. Increased risk of gastrointestinal disorders in the postacute phase of COVID-19 has also been reported in adults [47], with persistence of SARS-CoV-2 viral antigen in gut mucosal tissue associated with postacute sequelae [48]. A similar pathophysiologic mechanism may underlie increased risk of appendicitis and gastrointestinal sequelae following dengue in children, given that the small intestine has been identified as a major site of inflammation in animal models of late-stage dengue infection [49]. Approximately 1 out of every 1000 children infected with dengue went on to developed appendicitis within 300 days of infection. Appendicitis is a common surgical condition in children and adolescents, with a significant clinical and economic burden; the global age-standardized incidence rate of appendicitis in 2021 was 2.14 per 1000, corresponding to 17 million new cases yearly [50]. Additional prospective cohort studies are required to better characterize the burden and extent of chronic gastrointestinal sequelae and symptoms following dengue infection in children.

The present study has several strengths. Comprehensive nationwide registries were utilized to classify COVID-19 and dengue infections, with supporting laboratory confirmation. A comprehensive health care claims database with national-level coverage was utilized, minimizing bias caused by loss to follow-up. However, limitations are as follows. First, risks of postacute sequelae following dengue were contrasted against COVID-19 cases. While this allowed comparison against the better-characterized phenomenon of long COVID, true population-wide prevalence of chronic symptoms vis-à-vis uninfected controls could not be estimated. Moreover, comparisons of long-term sequelae against other viral infections known to cause chronic symptom persistence in children, such as Epstein-Barr virus infections [51], could not be made. Second, underreporting of asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 infections might bias estimates of risk downward due to inclusion of more severe COVID-19 cases for comparison against dengue. Yet, this study was conducted during a period when COVID-19 testing was widely available in the primary care setting and fully subsidized [5, 20] and public health messaging encouraged individuals to present to health care settings for confirmatory testing and subsequent triage to home recovery or hospitalization. Third, serotype data were unavailable for dengue, and the SARS-CoV-2 variant was imputed on the basis of the prevailing circulating variant, not individual-level sequencing, potentially leading to misclassification. Fourth, health care claims data were used to identify postacute sequelae, which might lead to underreporting of milder sequelae not affecting reimbursement. Finally, the dengue and SARS-CoV-2 cohorts were not fully contemporaneous, though increased risk of appendicitis following dengue vis-à-vis SARS-CoV-2 infection was still observed when restricted to contemporaneous infections alone. Specific observation of reduced postacute risk of respiratory sequelae in dengue, a nonrespiratory virus, as compared with COVID-19 provided reassurance that divergence in risk estimates was due to infection-specific factors and less likely due to changes in behavioral or environmental confounders over time.

CONCLUSION

Lower overall risk of postacute complications was observed following dengue infection in children when compared against COVID-19 cases, with the exception of higher risk of appendicitis 31 to 300 days after dengue infection as compared with COVID-19. More modest estimates of chronic sequelae following dengue infection in the pediatric population vs COVID-19 are reassuring, particularly in tropical countries whose health care systems may be strained by concurrent dengue and COVID-19 outbreaks during COVID-19 endemicity. Public health strategies to mitigate the impact of dengue and COVID-19 in children should consider the possibility of chronic postinfectious sequelae.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. L. E. W. and J. T. L. contributed to the literature search and writing of the manuscript. J. T. L., J. Y. J. T. , C. C., C.-F. Y., C. Y. C., D. C. L., and K. B. T. contributed to critical review and editing of the manuscript. D. C. L. and K. B. T. provided supervision. K. B. T., L. E. W., and J. T. L. contributed to study design. J. Y. J. T. contributed to data collection and data analysis. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. L. E. W., J. T. L., and J. Y. J. T. directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the article. The corresponding author is the guarantor and accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Data sharing. The databases with individual-level information used for this study are not publicly available due to personal data protection. Deidentified data can be made available for research, subject to approval by the Ministry of Health of Singapore. All inquiries should be sent to the corresponding author.

Patient consent statement. This study met “review not required” criteria for national public health research under the Infectious Diseases Act, Singapore (1976); institutional review board review and informed consent were waived under the stipulation of the act, and declaration of exemption was additionally sought and obtained from the board (NTU-IRB reference IRB-2024-002). All data were anonymized prior to usage and analysis.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Medical Research Council, Singapore, under its Clinician-Scientist Individual Research Grant (MOH-001572 to J. T. L.).

References

Author notes

L. E. W., J. T. L., and J. Y. J. T. contributed equally.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

Comments