-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andrea Antoniolli, Hélène Guis, Mathieu Picardeau, Cyrille Goarant, Claude Flamand, One Health Field Approach Applied to Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Across Humans, Animals and the Environment, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 12, Issue 1, January 2025, ofae757, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofae757

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Leptospirosis is a neglected zoonosis transmitted through urine of infected hosts or contaminated environments. The transmission of bacteria between humans, animals, and the environment underscores the necessity of a One Health approach.

We conducted a systematic review to identify significant findings and challenges in One Health research on leptospirosis, focusing on studies involving sampling in ≥2 of the 3 compartments: human, animal, and environment. We searched in PubMed, Web of Science, Medline, Scopus, and ScienceDirect from 1 January 1918 to 31 December 2022. We assessed risk of bias in studies using Joanna Briggs Institute tools and performed a meta-analysis to identify links between One Health compartments.

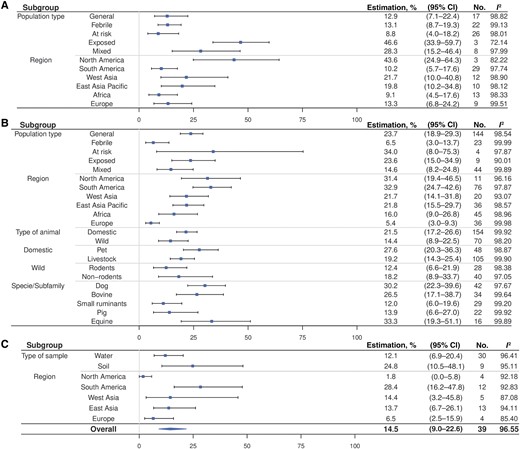

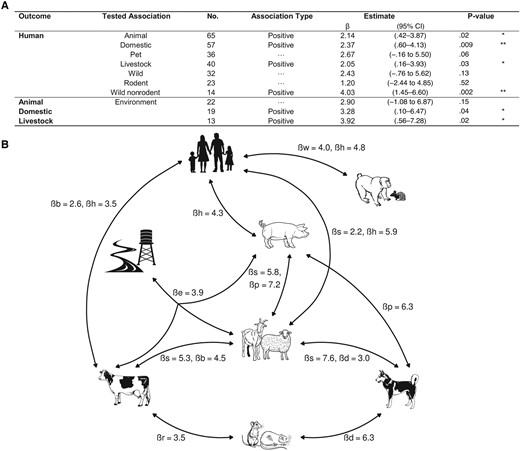

Of 1082 leptospirosis studies with sampling, 102 multicompartmental studies conducted between 1972 and 2022 were included: 70 human-Animal, 18 animal-environment, 4 human-environment, and 10 across all compartments. Various methodological weaknesses were identified, from study design to statistical analysis. Meta-regressions identified positive associations between human and animal seroprevalences, particularly with livestock and with wild nonrodent animals, and a link between the environmental positivity rate and domestic animal seroprevalence. Our analysis was constrained by the limited number of studies included and by the quality of protocols.

This 50-year overview of One Health field approach to leptospirosis highlights the critical need for more robust, well-supported One Health research to clarify the transmission dynamics and identify risk factors of zoonoses.

Leptospirosis is a globally distributed bacterial zoonosis that affects mammals through leptospires penetration via wounds or mucous membranes. After colonization of the kidneys, the bacteria are excreted in urine [1]. Mammals may contract the infection directly from infected urine or through contact with environments contaminated by leptospires, where these bacteria can survive for several months [2].

The Leptospira genus comprises 69 species, classified into more than 250 serovars across more than 25 serogroups [3]. Due to its varied clinical manifestations, often characterized by influenzalike symptoms [3], leptospirosis is frequently misdiagnosed as other febrile illness like dengue or malaria, leading to its significant underestimation. With estimates of >1 million cases and about 60 000 deaths annually, predominantly in tropical regions [4], leptospirosis remains a neglected tropical disease [5, 6]. The diversity of serovars complicates serological diagnosis due to the low cross-reactivity of serovar-specific antibodies. The microscopic agglutination test (MAT), despite being the gold standard for serological diagnosis, has several limitations [7], contributing to the disease's neglect.

Host specificity of serovars varies widely, some serovars infect a broad range of hosts while others are host specific. Host roles in transmission also differ. Susceptible hosts might experience severe illness or death, excreting leptospires only during the acute phase, whereas maintenance hosts may show mild or no symptoms but continuously excrete leptospires for months or their entire lifespan, thus acting as reservoirs [3]. This enduring excretion is facilitated by coadaptation between host and serovar, like Icterohaemorrhagiae and rats or Hardjo and cattle [1].

Despite ongoing research, significant uncertainties about leptospires transmission remain, especially concerning regional and contextual variations. The environment's role is particularly unclear even though many outbreaks occur after heavy rainfalls or floods [2, 3]. The environment could serve as an intermediary between reservoirs and humans, potentially acting as a vector by dispersing leptospires. Heavy rainfalls might cause contaminated surface soil to slip into watercourses, carrying leptospires to humans. In addition, floods can transport leptospires, leading to new exposures [8]. This issue may grow with climate change and its effects on flooding [9] and rainfall [10]. Moreover, the role in disease transmission of dogs, often in close contact with humans [3], is not well understood.

Addressing uncertainties requires a One Health approach that integrates human, animal and environmental health disciplines [11] to clarify each compartment's role in pathogen dissemination, thereby enhancing our understanding of transmission dynamics and informing mitigation strategies.

This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of One Health field approaches to leptospirosis, identifying their strengths, challenges, and research quality. It also aims to guide future robust and integrated studies. Furthermore, through meta-analysis, this review seeks to identify factors linked to Leptospira presence or seroprevalence across the 3 compartments and explore intercompartment connections to elucidate transmission pathways.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis following the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023394574) through the National Institute for Health and Care Research [13] on 21 March 2023.

Study Eligibility

This review focused on field studies incorporating the One Health concept, specifically those involving ≥2 of the 3 One Health compartments: human, animal, and environmental. Eligible studies needed to report Leptospira presence or exposure across these compartments, with clear descriptions of sample sizes. We excluded single-compartment studies, reviews, case reports, editorial comments, and studies without original field data. No language restrictions were applied.

Data Source and Search Strategy

We searched databases including Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, ScienceDirect and Medline from 1 January 1918 to 31 December 2022. The search strategy for Web of Science is detailed in Supplementary Material 1 and Supplementary Table 1. We excluded unpublished manuscripts and translated non-English and non-French studies using digital tools, verified by native speakers when necessary.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Titles and abstracts were initially screened, followed by full-text evaluations. Two reviewers resolved disagreements through discussion, involving a third arbitrator if necessary. Data were independently extracted by 2 reviewers into a structured Microsoft Excel form, and the risk of bias was assessed. Extracted information included study design, population, sample types, laboratory tests, data analysis, study limitations, and conclusions. We also collected data on prevalence, type of laboratory test, number positive, and total tested for each sample type. Study designs were classified into 6 categories, including a “mixed” category for diverse designs. Populations were categorized into 5 groups, also including a mixed category for various types: general population, febrile population, exposure to positive cases, and population at risk due to a given practice or lifestyle. The sample size calculation was complete if it covered human and animal species and partial if it omitted any of these. Randomization was assessed similarly, with wildlife trapping considered inherently random and environmental sampling was considered unsuitable for randomization, given the difficulty of achieving representativeness.

The quality of each study was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools (presented in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2) tailored to the study design [14, 15]. Populations were categorized into 4 groups: humans, domestic animals, wild animals, and the environment. Each group's protocol quality was evaluated independently, with inappropriate questions omitted from the JBI tool to ensure standardized scoring. Scores were normalized to 1 for comparability across groups.

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were conducted using R software, version 4.3.1 [16]. Meta-analyses were performed via generalized linear random-effects models to estimate subgroup-aggregated proportions using the rma.glmm function from the metafor R package [17]. These models accounted for variability among studies due to heterogeneity [18]. Pooled proportions of individuals testing positive for bacteria or antibodies were expressed as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Data were logit transformed for modeling and subsequently inverse-logit transformed for generating estimates and forest plots [19]. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I² statistic [19]. For the meta-analysis, all studies were included, regardless of their JBI score. For animal data, each species from a study was considered separately, and for environmental data, each sample type (water or soil) was treated individually. Consequently, multiple proportions from the same study could be included in the meta-analysis, appearing separately for different species or sample types. For environmental data, the positivity rate was calculated by combining findings of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and culture. Subgroups were established based on study population type, geographic region, animal type, species or subfamilies, and environmental sample type. Subgroups of species were considered if included in ≥10 studies.

Generalized linear mixed-effects models were used to assess the impact of moderator variables on outcomes, incorporating fixed effects of variables like study population type, geographic region, country, animal type, species and observed proportion rates. Adjustments were based on study population type: febrile, general, at risk, exposed, or mixed. There were 2 conditions for testing an association by explaining one positivity rate by another. First, we fixed the minimum sample size at 10 studies: ≥10 studies had to measure the 2 positivity rates to be tested. Second, a positivity rate was used as an explanatory variable only if it was measured in ≥10 individuals.

RESULTS

Eligible Studies

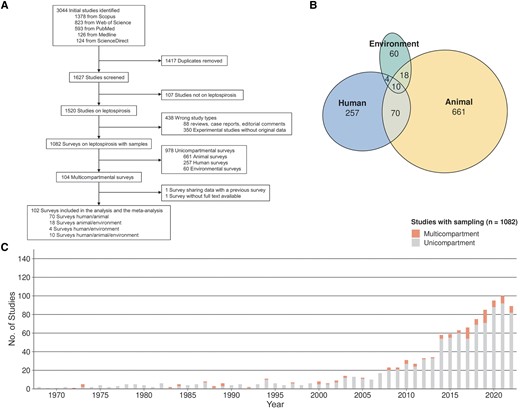

We initially identified 3044 studies. After removing 1417 duplicates and screening 1627 studies, we included 102 in the review, covering the period from 1972 to 2022 (Figure 1A). We excluded 978 unicompartmental surveys and 1 study [20] with redundant data from a previous article [21]. Another study was excluded due to the unavailability of the full text [22].

Implementation of the One Health approach. A, Flowchart of study selection. B, Venn diagram showing the numbers of studies with sampling, according to the compartment(s) investigated. C, Numbers of unicompartmental and multicompartmental studies published per year.

Figure 1B displays a Venn diagram illustrating intersections among the 102 One Health studies included. The environmental compartment was the least represented in unicompartmental studies (n = 60 [6.1%]) and appeared in only 30.7% of multicompartmental studies. In contrast, animals and humans were included in 94.2% and 82.4% of studies, respectively. Only 10 studies (9.8%) investigated all 3 compartments. The use of multicompartmental approaches studying leptospirosis significantly increased after the year 2000 (Figure 1C), but overall such approaches were used in only 9.6% of published studies.

Database Description

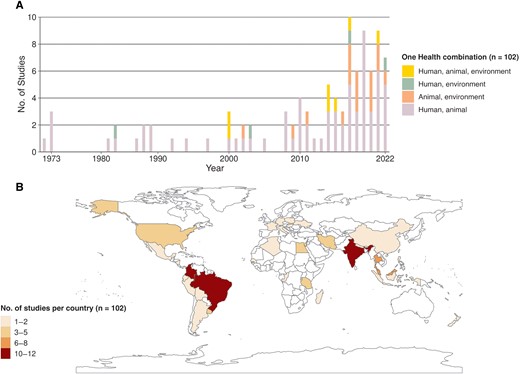

The investigation of the environment has progressed more gradually compared with the other 2 compartments (Figure 2A). Before 2000, only 6% of studies (1 of 15) involved the environment, compared with 36% (31 of 87) after 2000. Most studies were conducted in South America (n = 36 [35.3%]) or Asia (n = 34 [33.3%]) (Figure 2B). Supplementary Table 2 provides the detailed geographic distribution.

Spatiotemporal distribution of included studies. A, Number of studies included per year, showing compartments of the One Health concept investigated. B, Spatial distribution of the numbers of studies by country.

Table 1 describes the characteristics of included studies. Among the 98 animal studies, 44% focused on domestic animals, 22% on wild animals and 34% on both. Of the 76 studies investigating domestic animals, 33% investigated livestock, 26% pets, and 41% both. Among the 32 environmental studies, 22 (69%) investigated water, 9 (28%) both water and soil, and 1 (3%) examined only the air. Environmental samples were mainly from nearby farms (38%) or houses (28%), with 34% involving domestic water and 34% waterways.

Characteristics of One Health Studies on Leptospirosis Included in the Current Review

| Study Authors (Year) . | Type . | Date . | Country . | Design . | Population . | Test . | Positivity Rate . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maronpot and Barsoum (1972) [23] | H, A | 1968–1971 | Egypt | Prevalence survey | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 52/513, cows 209/424, pigs 70/130, goats 135/195, sheep 57/330, horses 11/31, camels 29/50 |

| Nelson et al (1973) [24] | H, A | 1964 | USA | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 61/245, cows 26/305 |

| CAR | Cows 9/43 | ||||||

| Tsai et al (1973) [25] | H, A | 1968 | Taiwan | Prevalence survey | H: gen A: gen | MAT | H 25/167, dogs 0/2, cows 18/57, pigs 0/64, goats 2/32, civets 1/2, rodents 3/47 |

| Culture | Civets 1/2, rodents 7/59 | ||||||

| Limpias and Marcus (1973) [26] | H, A | … | Bolivia | Prevalence survey | H: feb A: mix | MAT | H 7/142, dogs 1/17, cows 372/520, pigs 7/102, goats 4/53, sheep 1/61, horses 76/101, monkeys 1/1, bats 0/9, rabbits 0/1, snakes 0/1, boars 1/1, deer 1/1, rodents 0/3 |

| Ratnam et al (1983) [27] | H, A | India | Cluster investigation | H: mix A: feb | MAT | H 35/75, cows 27/40 | |

| Culture | Cows 0/9 | ||||||

| Prokopcaková and Pospisil (1984) [28] | H, A | … | Slovakia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | ALR | H 28/876, cows 13/168, rodents 20/243 |

| Gelosa and Manera (1984) [29] | H, E | 1980–1983 | Italia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb | MAT | H 34/168 |

| Culture | Water 0/40 | ||||||

| Sebek et al (1987) [30] | H, A | 1976–1982 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 80/2448, cows 2/4, pigs 15/89, goats 6/65, sheep 9/328 |

| Heisey et al (1988) [31] | H, A | 1983–1984 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: feb | MAT/Culture | H 33/110 |

| MAT | Dogs 56/293, cats 0/8, cows 54/204, pigs 3/17, rodents 84/174 | ||||||

| Culture | Cows NA/150, rodents 23/75 | ||||||

| Everard et al (1988) [32] | H, A | 1982–1984 | Belize | Prevalence survey | H: mix A: mix | MAT | H 99/451, dogs 5/7, cows 136/155, pigs 32/71, goats and sheep 88/162 |

| Sebek et al (1989) [33] | H, A | 1987 | Egypt | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 17/196, dogs 0/1, cows 0/1, pigs 4/28, goats 1/67, horses 2/12, rodent 36/65 |

| Sebek et al (1989) [34] | H, A | 1983 | Cape Verde | Prevalence survey | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 44/611, dogs 0/89, cows 3/150, pigs 0/316, goats 34/640, sheep 0/39, horses 3/64, rodents 0/211 |

| Venkataraman and Nedunchelliyan (1992) [35] | H, A | 1988 | India | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 48/95, dogs 20/94, bandicoots 10/24, rodents 8/64 |

| DFM | H 10/48+,a dogs 8/20+, bandicoots 8/24+, rodents 5/32 | ||||||

| Culture | H 1/10+, dogs 1/8+ | ||||||

| Prokopcáková et al (1994) [36] | H, A | 1991–1993 | Slovakia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 56/1740, rodents 99/1038, shrews 1/68 |

| Machang’u et al (1997) [37] | H, A | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 1/375, dogs 80/208, cows 28/374, rodents 10/537 | |

| Culture | Cows 7/1021 | ||||||

| Campagnolo et al (2000) [38] | H, A, E | 1998 | USA | Cluster investigation | H: risk; A: feb | IgMELISA | H 9/17 |

| MAT | Pigs 97/302 | ||||||

| Culture | Pigs 4/6, water 0/8 | ||||||

| Ochoa et al (2000) [39] | H, A | 1997–1998 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 15/67, cows 106/174, pigs 60/278 |

| Vanasco et al (2000) [40] | H, A, E | 1998 | Argentina | Cluster investigation | H: mix; A: exp | MAT | H 12/32, dogs 6/8 |

| DFM | Water 8 spirochete+/8 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 8 spirochete+/8 | ||||||

| Ralaiarijaona et al (2001) [41] | H, A | 2000 | Madagascar | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 1/105 |

| PCR | Cows 0/50, pigs 0/13, rodents 0/115 | ||||||

| León et al (2002) [42] | A, E | 1996–1998 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | A: feb | MAT | Pigs 0/68 |

| DFM | Water 91/339 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 38/311 | ||||||

| Natarajaseenivasan et al (2002) [43] | H, A | 2000 | India | Mixed | H: mix; A: gen | IgGELISA | H 241/268 |

| MAT | H 231/338, dogs 2/4, cats 6/9, cows 18/34, rodents 12/23 | ||||||

| Ramakrishnan et al (2003) [44] | H, E | 2001 | India | Cluster investigation | H: exp | MAT | H 20/64 |

| Culture | Water 1/1 | ||||||

| PCR | Water 1/1 | ||||||

| Cerri et al (2003) [45] | H, A | 1995–2001 | Italia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 14/250, dogs 278/4369, cows 7/644, pigs 123/1299, sheep 132/1088, horses 107/938, boars 11/459, deer 0/567, wolves 0/4, marmots 0/120, rodents 0/4 |

| Ren et al (2005) [46] | H, A | 1998–2003 | China | Longitudinal monitoring | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 57/1777, pigs 10/232 |

| Culture | Dogs 0/30, pigs 1/524, rodents 16/123 | ||||||

| Kuriakose et al (2008) [47] | H, A | 1993–1997 | India | Longitudinal monitoring | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 38/376, bandicoot 4/9, shrews 0/5, rodents 2/40 |

| DFM | Bandicoots 2/4, rodents 1/2 | ||||||

| Culture | Bandicoots 0/2, shrews 0/2, rodents 1/6 | ||||||

| Langoni et al (2008) [48] | H, A | 2005 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 8/34, cows 46/140, rodents 0/50 |

| Culture | Cows 0/140, rodents 0/50 | ||||||

| PCR | Rodents 0/50 | ||||||

| Habuš et al (2008) [49] | H, A | 2007 | Croatia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 24/113, dogs 2/20, cows 295/9867, pigs 1397/15524, goats 24/1639, sheep 46/16278, horses 196/1212, foxes 36/70, wild animals (undefined) 0/100 |

| Zhou et al (2009) [50] | H, A | 2002 | China | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 444/772 |

| Culture | Cows 11/225, rodents 22/726 | ||||||

| Aviat et al (2009) [51] | A, E | 2001–2004 | France | Prevalence survey | A: exp | MAT | Rodents 288/649 |

| PCR | Rodents 41/516, water 6/151 | ||||||

| Silva et al (2010) [52] | H, A | 2006 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 0/15, Snake 47/110, Fish 2/25, Bird 34/143, Wild undefined 11/49 |

| Zakeri et al (2010) [53] | H, A | 2005–2007 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 98/369, dogs 33/150, sheep 13/175 |

| Romero et al (2011) [54] | H, A | 2007 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 51/850, dogs 182/850 |

| Bermúdez et al (2010) [55] | H, A | … | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 10/46, dogs 41/61 |

| Cárdenas-Marrufo et al (2011) [56] | A, E | 2004–2005 | Mexico | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Dogs 22/61, cows 97/212, pigs 26/203 |

| PCR | Water 0/68 | ||||||

| De Castro et al (2011) [57] | H, A | 2007–2009 | Brazil | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 7/97, dogs 76/268 |

| Romero et al (2011) [54] | H, A | 2009–2010 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 5/20, monkeys 15/65 |

| Fonzar and Langoni (2012) [58] | H, A | 2006–2008 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 5/25, dogs 41/335 |

| Romero-Vivas et al (2013) [59] | H, A | 2007–2009 | Colombia | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 16/128, dogs 19/83, rodents 13/69 |

| Culture | H 0/10, dogs 0/54, rodents 1/69 | ||||||

| PCR | H 1/10 PCR, dogs 2/4 (2+), rodents 2/16 | ||||||

| Calderón et al (2014) [60] | H, A, E | 2009–2011 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 47/62, dogs 19/54, pigs 214/383, rodents 0/39 |

| Culture | Dogs 2/54, pigs 3/171, rodents 1/39, water 9/57 | ||||||

| PCR | Dogs 2/2+, pigs 3/3+, water 2/9+ | ||||||

| Soman et al (2014) [61] | H, A | India | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 84/154, dogs 44/121, wild animals (undefined) 9/42 | |

| Culture | H 1/154, dogs 1/121, bandicoots 3/11, rodents 2/24 | ||||||

| Vimala et al (2014) [62] | H, A | 2009–2010 | India | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 10/129, rodents 9/24 |

| Silva et al (2014) [63] | H, A | 2013 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 2/10, dogs 6/12, sheep 7/34, horses 6/10, rodents, 1/1, feral cats 0/1, foxes 1/2, tatous 0/16 |

| Assenga et al (2015) [64] | H, A | 2012–2013 | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 80/267, cows 346/1141, goats 22/248, lions 1/2, zebras 0/2, shrews 1/11, rodent 42/207 |

| Samir et al (2015) [65] | H, A, E | Egypt | Cluster investigation | H: exp; A: mix | MAT | H 87/175, dogs 98/168, cows 239/651, sheep 45/99, horses 2/40, camels 0/22, rodents 205/270 | |

| Culture | H 0/175, dogs 19/168, cows 7/651, sheep 0/99, horses 0/40, camels 0/22, rodents 17/270 | ||||||

| PCR | H 0/175, dogs 65/168, cows 7/651, horses 0/40, sheep 0/99, camels 0/22, rodents 65/270, water 10/45 | ||||||

| Da Silva et al (2015) [66] | H, A | 2012 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 11/28, dogs 7/13, cows 6/17, goats 16/37, sheep 16/41, horses 30/57, foxes 6/11, opossums 1/1, tatous 4/4, monkeys 3/4, coatis 2/3, rodents 1/1 |

| Lugo-Chávez et al (2015) [67] | H, A | 2012 | Mexico | Cluster investigation | H: exp; A: gen | MAT | H 22/36, dogs 19/29 |

| Barragan et al (2016) [68] | H, A | 2013–2015 | Ecuador | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 100/680, cows 59/165, pigs 27/128, rodents 3/101 |

| Cibulski and Wollanke (2016) [69] | A, E | … | Germany and Luxembourg | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Shrews 3/67, Mole 1/1, rodents 38/226, water 9/87 |

| Parveen et al (2016) [70] | H, A | India | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 94/244, dogs 4/15, cows 39/86, goats 7/29, rodents 9/23 | |

| Culture | Rodents 2/23 | ||||||

| Habus et al (2017) [71] | H, A | 2009–2014 | Croatia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 395/1917, dogs 85/364, cows 3251/22 669, pigs 2016/18 163, goats and sheep 376/41 752, horses 5595/41 538 |

| Chadsuthi et al (2017) [72] | H, A | 2010–2015 | Thailand | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 471/1990, cows 1133/4080, pigs 356/3138 |

| Pui et al (2017) [73] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 23/107, water 13/324, soil 46/292 |

| Kurilung et al (2017) [74] | H, A, E | 2013–2016 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | Culture | H 0/37, dogs 4/58, cows 1/131, pigs 6/152, goats 0/1, horses 0/1, water 0/14 |

| PCR | H 1/37, dogs 6/58, cows 16/131, pigs 12/152, goats 1/1, water 3/14 | ||||||

| Ensuncho-Hoyos et al (2017) [75] | H, A, E | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 14/20, dogs 5/11, cows 242/325, water 0/39 | |

| Culture | Cows 3/78 | ||||||

| PCR | Cows 3/3+, water 1/39 | ||||||

| Jorge et al (2017) [76] | H, A | 2003–2007 | Brazil | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H NA/997, dogs NA/1176, cows NA/1484, horses NA/240 |

| Meny et al (2017) [77] | H, E | 2010–2016 | Uruguay | Cluster investigation | H: feb | MAT | H 5/302 |

| Culture | H 8/302, water 7/36 | ||||||

| PCR | H 8/8+, water 6/7+ | ||||||

| Pui et al (2017) [78] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 1/31, water 17/210, soil 8/210 |

| Sanhueza et al (2017) [79] | H, A | 2009–2013 | New Zealand | Prevalence survey | H: risk A: gen | MAT | H 12/178, cows 717/1374, sheep 939/2178, Deer 72/1133 |

| Grevemeyer et al (2017) [80] | A, E | … | Saint Kitts and Nevis | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Horses 22/124, water 0/2 |

| Biscornet et al (2017) [81] | H, A | 2013–2015 | Seychelles | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | IgMELISA | H 18/223 |

| MAT | H 19/223 | ||||||

| PCR | H 32/223, dogs 1/24, cats 1/12, rodents 57/739 | ||||||

| Chávez et al (2018) [82] | A, E | 2014–2016 | Nicaragua | Cluster investigation | A: exp | MAT | Dogs NA/159, cats NA/1, cows NA/36, pigs NA/60, horses NA/7 |

| Culture | Dogs NA/75, cows NA/15, pigs NA/22, water 61/129, soil 14/69 | ||||||

| Shrestha et al (2018) [83] | H, A | 2013 | Nepal | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 13/239, dogs 9/20, cows 60/155, goats 31/181, rodents 3/14 |

| Zala et al (2018) [84] | A, E | 2016–2017 | India | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | PCR | Dogs 2/30, cows 20/121, goats 1/40, soil 8/60, water 80/216 |

| Cortez et al (2018) [85] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Peru | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | Culture | Water 1/64 |

| PCR | Rodents 23/97, water 23/64, soil 21/25 | ||||||

| Tabo et al (2018) [86] | H, A | 2015 | Philippines | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 7/46, cows 3/9, pigs 37/69 |

| Ukhovskyi et al (2018) [87] | H, A | 2009–2016 | Ukraine | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 3012/24 990, cats 52 310/1 238 876, pigs 31 181/989 659, horses 6734/70 674 |

| Markovych et al (2019) [88] | H, A | 2005–2015 | Ukraine | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 401/2079, rodents 276/2820 |

| Takhampunya et al (2019) [89] | H, A | 2014–2018 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 3 pools/23 pools (200), rodents 3pools/64pools (309) |

| Salmon-Mulanovich (2019) [90] | H, A | 2011–2014 | Peru | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 229/2165, dogs 44/53, cats 2/10, Poultry 30/37, rodents 2/30 |

| Jittimanee and Wongbutdee (2019) [91] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 0/270, water 0/100 |

| Marinova-Petkova et al (2019) [92] | H, A, E | 2017–2019 | US Virgin Islands | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT/RDT | H 2/78 |

| MAT | Dogs 1/1 | ||||||

| PCR | H 1/2, dogs 0/1, water 1/5 | ||||||

| Bakoss et al (2019) [93] | H, A | … | Slovakia | Cluster investigation | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 12/19, cows 9/15, rodents 2/44 |

| Meny et al (2019) [94] | H, A, E | 2015–2017 | Uruguay | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT/IIF | H 140/308 |

| MAT | Dogs 8/50, horses 11/22 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 6/25 | ||||||

| Neela et al (2019) [95] | H, A, E | 2016 | Malaysia | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: gen | MAT/RDT/ IgMELISA | H 4/12 |

| PCR | Rodents 6/12, water 6/18, soil 8/18 | ||||||

| Nadia et al (2019) [96] | H, A | … | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 10/23, monkeys 5/10, shrews 1/1, rodents 4/43 |

| Roqueplo et al (2019) [97] | H, A | 2012–2014 | Senegal | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 42/545, dogs 32/33, cows 17/56, goats 18/52, sheep 3/43, horses 16/20 |

| PCR | Rodents 2/36 | ||||||

| Verma et al (2019) [98] | A, E | 2016–2017 | USA | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Cows 7/21, horses 13/31 |

| PCR | Rabbit 0/1, squirrels 0/1, shrews 3/6, rodents 60/93, water 2/89 | ||||||

| Calderón et al (2019) [99] | H, A | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 4/123, horses 130/153 | |

| Culture | Horses 99/153 | ||||||

| PCR | Horses 0/99+ | ||||||

| Mgode et al (2019) [100] | H, A | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: mix A: gen | MAT | H 72/455, shrews 1/5 rodents 3/21 | |

| Culture | Shrews 0/5, rodents 0/21 | ||||||

| Goh et al (2019) [21] | H, A | … | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 67/194, dogs 70/266, cats 7/47 |

| Rodriguez et al (2020) [101] | H, A | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | IgMELISA | H 25/83 | |

| PCR | Rodents 4/53 | ||||||

| Murcia et al (2020) [102] | H, A | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 2/69, dogs 53/92 | |

| Culture | Dogs 54/92 | ||||||

| Alashraf et al (2020) [103] | H, A | … | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 5/58, dogs 26/127, cats 7/47 |

| Grimm et al (2020) [104] | A, E | 2008–2009 | USA | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | MAT | Feral cats 0/19, opossums 60/112, racoons 121/221 |

| PCR | Water 6/8 | ||||||

| Wójcik-Fatla et al (2020) [105] | A, E | Poland | Prevalence survey | A: gen | ELISA | Cows 0/80, pigs 51/86 | |

| PCR | Air 2/50 | ||||||

| Dushyant et al (2020) [106] | A, E | India | Prevalence survey | A: mix | Culture | Dogs 0/5, cows 0/77, rodents 0/5, water 0/3 | |

| PCR | Dogs 0/10, cows 55/299, water 0/16, soil 0/4 | ||||||

| Van et a (2017) [107] | H, A, E | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | ImmunoC | H 199/280 | |

| PCR | Fish 8/11, water 4/12, soil 9/12 | ||||||

| Ospina-Pinto and Hernández-Rodríguez (2021) [108] | A, E | 2019 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Pigs 58/65 |

| Culture | Pigs 10/65, water 10/15 | ||||||

| PCR | Pigs 10/10+, water 10/10+ | ||||||

| Benitez et al (2021) [109] | H, A | 2015–2016 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 11/597, dogs 155/729 |

| Mgode et al (2021) [110] | H, A | … | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 15/50, goats 28/45, sheep 34/56, rodents 7/45 |

| Machado et al (2021) [111] | H, A | 2016–2018 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 0/49, dogs 18/170, boars 9/74 |

| Dreyfus et al (2021) [112] | H, A | 2015 | Bhutan | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 14/864, dogs 40/84, cows 48/130 |

| Msemwa et al (2021) [113] | H, A | 2018 | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 33/205, dogs 66/414 |

| Medkour et al (2021) [114] | H, A | 2016–2019 | Congo Algeria Senegal Djibouti | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | PCR | H 31/38, Gorilla 46/172 |

| Shamsusah et al (2021) [115] | A, E | 2017–2018 | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Gorilla 1/12, rodents 1/23, soil 22/123, water 7/37 |

| Aghamohammad et al (2022) [116] | H, A | 2019 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: mix | IgGELISA | H 1/51, cows 0/30, goats 1/31, sheep 2/30 |

| Setyaningsih et al (2022) [117] | H, E | 2017–2018 | Indonesia | Case control | H: mix | PCR | H 34 (in case-control studyb), water 6/100 |

| de Souza Rocha et al (2022) [118] | H, A | 2014–2015 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 15/80, dogs 31/85, cats 0/10 |

| PCR | Dogs 13/68 | ||||||

| Cunha et al (2022) [119] | H, A | 2017–2019 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 0/19, dogs 16/264 |

| Richard et al (2022) [120] | A, E | 2018–2020 | France | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 68/189, water 158/1031 |

| do Couto (2022) [121] | H, A | … | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 0/200, dogs 5/40 |

| Meny et al (2022) [122] | H, A | 2017–2020 | Uruguay | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 6/150, horses 546/891 |

| Study Authors (Year) . | Type . | Date . | Country . | Design . | Population . | Test . | Positivity Rate . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maronpot and Barsoum (1972) [23] | H, A | 1968–1971 | Egypt | Prevalence survey | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 52/513, cows 209/424, pigs 70/130, goats 135/195, sheep 57/330, horses 11/31, camels 29/50 |

| Nelson et al (1973) [24] | H, A | 1964 | USA | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 61/245, cows 26/305 |

| CAR | Cows 9/43 | ||||||

| Tsai et al (1973) [25] | H, A | 1968 | Taiwan | Prevalence survey | H: gen A: gen | MAT | H 25/167, dogs 0/2, cows 18/57, pigs 0/64, goats 2/32, civets 1/2, rodents 3/47 |

| Culture | Civets 1/2, rodents 7/59 | ||||||

| Limpias and Marcus (1973) [26] | H, A | … | Bolivia | Prevalence survey | H: feb A: mix | MAT | H 7/142, dogs 1/17, cows 372/520, pigs 7/102, goats 4/53, sheep 1/61, horses 76/101, monkeys 1/1, bats 0/9, rabbits 0/1, snakes 0/1, boars 1/1, deer 1/1, rodents 0/3 |

| Ratnam et al (1983) [27] | H, A | India | Cluster investigation | H: mix A: feb | MAT | H 35/75, cows 27/40 | |

| Culture | Cows 0/9 | ||||||

| Prokopcaková and Pospisil (1984) [28] | H, A | … | Slovakia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | ALR | H 28/876, cows 13/168, rodents 20/243 |

| Gelosa and Manera (1984) [29] | H, E | 1980–1983 | Italia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb | MAT | H 34/168 |

| Culture | Water 0/40 | ||||||

| Sebek et al (1987) [30] | H, A | 1976–1982 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 80/2448, cows 2/4, pigs 15/89, goats 6/65, sheep 9/328 |

| Heisey et al (1988) [31] | H, A | 1983–1984 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: feb | MAT/Culture | H 33/110 |

| MAT | Dogs 56/293, cats 0/8, cows 54/204, pigs 3/17, rodents 84/174 | ||||||

| Culture | Cows NA/150, rodents 23/75 | ||||||

| Everard et al (1988) [32] | H, A | 1982–1984 | Belize | Prevalence survey | H: mix A: mix | MAT | H 99/451, dogs 5/7, cows 136/155, pigs 32/71, goats and sheep 88/162 |

| Sebek et al (1989) [33] | H, A | 1987 | Egypt | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 17/196, dogs 0/1, cows 0/1, pigs 4/28, goats 1/67, horses 2/12, rodent 36/65 |

| Sebek et al (1989) [34] | H, A | 1983 | Cape Verde | Prevalence survey | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 44/611, dogs 0/89, cows 3/150, pigs 0/316, goats 34/640, sheep 0/39, horses 3/64, rodents 0/211 |

| Venkataraman and Nedunchelliyan (1992) [35] | H, A | 1988 | India | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 48/95, dogs 20/94, bandicoots 10/24, rodents 8/64 |

| DFM | H 10/48+,a dogs 8/20+, bandicoots 8/24+, rodents 5/32 | ||||||

| Culture | H 1/10+, dogs 1/8+ | ||||||

| Prokopcáková et al (1994) [36] | H, A | 1991–1993 | Slovakia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 56/1740, rodents 99/1038, shrews 1/68 |

| Machang’u et al (1997) [37] | H, A | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 1/375, dogs 80/208, cows 28/374, rodents 10/537 | |

| Culture | Cows 7/1021 | ||||||

| Campagnolo et al (2000) [38] | H, A, E | 1998 | USA | Cluster investigation | H: risk; A: feb | IgMELISA | H 9/17 |

| MAT | Pigs 97/302 | ||||||

| Culture | Pigs 4/6, water 0/8 | ||||||

| Ochoa et al (2000) [39] | H, A | 1997–1998 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 15/67, cows 106/174, pigs 60/278 |

| Vanasco et al (2000) [40] | H, A, E | 1998 | Argentina | Cluster investigation | H: mix; A: exp | MAT | H 12/32, dogs 6/8 |

| DFM | Water 8 spirochete+/8 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 8 spirochete+/8 | ||||||

| Ralaiarijaona et al (2001) [41] | H, A | 2000 | Madagascar | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 1/105 |

| PCR | Cows 0/50, pigs 0/13, rodents 0/115 | ||||||

| León et al (2002) [42] | A, E | 1996–1998 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | A: feb | MAT | Pigs 0/68 |

| DFM | Water 91/339 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 38/311 | ||||||

| Natarajaseenivasan et al (2002) [43] | H, A | 2000 | India | Mixed | H: mix; A: gen | IgGELISA | H 241/268 |

| MAT | H 231/338, dogs 2/4, cats 6/9, cows 18/34, rodents 12/23 | ||||||

| Ramakrishnan et al (2003) [44] | H, E | 2001 | India | Cluster investigation | H: exp | MAT | H 20/64 |

| Culture | Water 1/1 | ||||||

| PCR | Water 1/1 | ||||||

| Cerri et al (2003) [45] | H, A | 1995–2001 | Italia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 14/250, dogs 278/4369, cows 7/644, pigs 123/1299, sheep 132/1088, horses 107/938, boars 11/459, deer 0/567, wolves 0/4, marmots 0/120, rodents 0/4 |

| Ren et al (2005) [46] | H, A | 1998–2003 | China | Longitudinal monitoring | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 57/1777, pigs 10/232 |

| Culture | Dogs 0/30, pigs 1/524, rodents 16/123 | ||||||

| Kuriakose et al (2008) [47] | H, A | 1993–1997 | India | Longitudinal monitoring | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 38/376, bandicoot 4/9, shrews 0/5, rodents 2/40 |

| DFM | Bandicoots 2/4, rodents 1/2 | ||||||

| Culture | Bandicoots 0/2, shrews 0/2, rodents 1/6 | ||||||

| Langoni et al (2008) [48] | H, A | 2005 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 8/34, cows 46/140, rodents 0/50 |

| Culture | Cows 0/140, rodents 0/50 | ||||||

| PCR | Rodents 0/50 | ||||||

| Habuš et al (2008) [49] | H, A | 2007 | Croatia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 24/113, dogs 2/20, cows 295/9867, pigs 1397/15524, goats 24/1639, sheep 46/16278, horses 196/1212, foxes 36/70, wild animals (undefined) 0/100 |

| Zhou et al (2009) [50] | H, A | 2002 | China | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 444/772 |

| Culture | Cows 11/225, rodents 22/726 | ||||||

| Aviat et al (2009) [51] | A, E | 2001–2004 | France | Prevalence survey | A: exp | MAT | Rodents 288/649 |

| PCR | Rodents 41/516, water 6/151 | ||||||

| Silva et al (2010) [52] | H, A | 2006 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 0/15, Snake 47/110, Fish 2/25, Bird 34/143, Wild undefined 11/49 |

| Zakeri et al (2010) [53] | H, A | 2005–2007 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 98/369, dogs 33/150, sheep 13/175 |

| Romero et al (2011) [54] | H, A | 2007 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 51/850, dogs 182/850 |

| Bermúdez et al (2010) [55] | H, A | … | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 10/46, dogs 41/61 |

| Cárdenas-Marrufo et al (2011) [56] | A, E | 2004–2005 | Mexico | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Dogs 22/61, cows 97/212, pigs 26/203 |

| PCR | Water 0/68 | ||||||

| De Castro et al (2011) [57] | H, A | 2007–2009 | Brazil | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 7/97, dogs 76/268 |

| Romero et al (2011) [54] | H, A | 2009–2010 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 5/20, monkeys 15/65 |

| Fonzar and Langoni (2012) [58] | H, A | 2006–2008 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 5/25, dogs 41/335 |

| Romero-Vivas et al (2013) [59] | H, A | 2007–2009 | Colombia | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 16/128, dogs 19/83, rodents 13/69 |

| Culture | H 0/10, dogs 0/54, rodents 1/69 | ||||||

| PCR | H 1/10 PCR, dogs 2/4 (2+), rodents 2/16 | ||||||

| Calderón et al (2014) [60] | H, A, E | 2009–2011 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 47/62, dogs 19/54, pigs 214/383, rodents 0/39 |

| Culture | Dogs 2/54, pigs 3/171, rodents 1/39, water 9/57 | ||||||

| PCR | Dogs 2/2+, pigs 3/3+, water 2/9+ | ||||||

| Soman et al (2014) [61] | H, A | India | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 84/154, dogs 44/121, wild animals (undefined) 9/42 | |

| Culture | H 1/154, dogs 1/121, bandicoots 3/11, rodents 2/24 | ||||||

| Vimala et al (2014) [62] | H, A | 2009–2010 | India | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 10/129, rodents 9/24 |

| Silva et al (2014) [63] | H, A | 2013 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 2/10, dogs 6/12, sheep 7/34, horses 6/10, rodents, 1/1, feral cats 0/1, foxes 1/2, tatous 0/16 |

| Assenga et al (2015) [64] | H, A | 2012–2013 | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 80/267, cows 346/1141, goats 22/248, lions 1/2, zebras 0/2, shrews 1/11, rodent 42/207 |

| Samir et al (2015) [65] | H, A, E | Egypt | Cluster investigation | H: exp; A: mix | MAT | H 87/175, dogs 98/168, cows 239/651, sheep 45/99, horses 2/40, camels 0/22, rodents 205/270 | |

| Culture | H 0/175, dogs 19/168, cows 7/651, sheep 0/99, horses 0/40, camels 0/22, rodents 17/270 | ||||||

| PCR | H 0/175, dogs 65/168, cows 7/651, horses 0/40, sheep 0/99, camels 0/22, rodents 65/270, water 10/45 | ||||||

| Da Silva et al (2015) [66] | H, A | 2012 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 11/28, dogs 7/13, cows 6/17, goats 16/37, sheep 16/41, horses 30/57, foxes 6/11, opossums 1/1, tatous 4/4, monkeys 3/4, coatis 2/3, rodents 1/1 |

| Lugo-Chávez et al (2015) [67] | H, A | 2012 | Mexico | Cluster investigation | H: exp; A: gen | MAT | H 22/36, dogs 19/29 |

| Barragan et al (2016) [68] | H, A | 2013–2015 | Ecuador | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 100/680, cows 59/165, pigs 27/128, rodents 3/101 |

| Cibulski and Wollanke (2016) [69] | A, E | … | Germany and Luxembourg | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Shrews 3/67, Mole 1/1, rodents 38/226, water 9/87 |

| Parveen et al (2016) [70] | H, A | India | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 94/244, dogs 4/15, cows 39/86, goats 7/29, rodents 9/23 | |

| Culture | Rodents 2/23 | ||||||

| Habus et al (2017) [71] | H, A | 2009–2014 | Croatia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 395/1917, dogs 85/364, cows 3251/22 669, pigs 2016/18 163, goats and sheep 376/41 752, horses 5595/41 538 |

| Chadsuthi et al (2017) [72] | H, A | 2010–2015 | Thailand | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 471/1990, cows 1133/4080, pigs 356/3138 |

| Pui et al (2017) [73] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 23/107, water 13/324, soil 46/292 |

| Kurilung et al (2017) [74] | H, A, E | 2013–2016 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | Culture | H 0/37, dogs 4/58, cows 1/131, pigs 6/152, goats 0/1, horses 0/1, water 0/14 |

| PCR | H 1/37, dogs 6/58, cows 16/131, pigs 12/152, goats 1/1, water 3/14 | ||||||

| Ensuncho-Hoyos et al (2017) [75] | H, A, E | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 14/20, dogs 5/11, cows 242/325, water 0/39 | |

| Culture | Cows 3/78 | ||||||

| PCR | Cows 3/3+, water 1/39 | ||||||

| Jorge et al (2017) [76] | H, A | 2003–2007 | Brazil | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H NA/997, dogs NA/1176, cows NA/1484, horses NA/240 |

| Meny et al (2017) [77] | H, E | 2010–2016 | Uruguay | Cluster investigation | H: feb | MAT | H 5/302 |

| Culture | H 8/302, water 7/36 | ||||||

| PCR | H 8/8+, water 6/7+ | ||||||

| Pui et al (2017) [78] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 1/31, water 17/210, soil 8/210 |

| Sanhueza et al (2017) [79] | H, A | 2009–2013 | New Zealand | Prevalence survey | H: risk A: gen | MAT | H 12/178, cows 717/1374, sheep 939/2178, Deer 72/1133 |

| Grevemeyer et al (2017) [80] | A, E | … | Saint Kitts and Nevis | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Horses 22/124, water 0/2 |

| Biscornet et al (2017) [81] | H, A | 2013–2015 | Seychelles | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | IgMELISA | H 18/223 |

| MAT | H 19/223 | ||||||

| PCR | H 32/223, dogs 1/24, cats 1/12, rodents 57/739 | ||||||

| Chávez et al (2018) [82] | A, E | 2014–2016 | Nicaragua | Cluster investigation | A: exp | MAT | Dogs NA/159, cats NA/1, cows NA/36, pigs NA/60, horses NA/7 |

| Culture | Dogs NA/75, cows NA/15, pigs NA/22, water 61/129, soil 14/69 | ||||||

| Shrestha et al (2018) [83] | H, A | 2013 | Nepal | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 13/239, dogs 9/20, cows 60/155, goats 31/181, rodents 3/14 |

| Zala et al (2018) [84] | A, E | 2016–2017 | India | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | PCR | Dogs 2/30, cows 20/121, goats 1/40, soil 8/60, water 80/216 |

| Cortez et al (2018) [85] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Peru | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | Culture | Water 1/64 |

| PCR | Rodents 23/97, water 23/64, soil 21/25 | ||||||

| Tabo et al (2018) [86] | H, A | 2015 | Philippines | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 7/46, cows 3/9, pigs 37/69 |

| Ukhovskyi et al (2018) [87] | H, A | 2009–2016 | Ukraine | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 3012/24 990, cats 52 310/1 238 876, pigs 31 181/989 659, horses 6734/70 674 |

| Markovych et al (2019) [88] | H, A | 2005–2015 | Ukraine | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 401/2079, rodents 276/2820 |

| Takhampunya et al (2019) [89] | H, A | 2014–2018 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 3 pools/23 pools (200), rodents 3pools/64pools (309) |

| Salmon-Mulanovich (2019) [90] | H, A | 2011–2014 | Peru | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 229/2165, dogs 44/53, cats 2/10, Poultry 30/37, rodents 2/30 |

| Jittimanee and Wongbutdee (2019) [91] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 0/270, water 0/100 |

| Marinova-Petkova et al (2019) [92] | H, A, E | 2017–2019 | US Virgin Islands | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT/RDT | H 2/78 |

| MAT | Dogs 1/1 | ||||||

| PCR | H 1/2, dogs 0/1, water 1/5 | ||||||

| Bakoss et al (2019) [93] | H, A | … | Slovakia | Cluster investigation | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 12/19, cows 9/15, rodents 2/44 |

| Meny et al (2019) [94] | H, A, E | 2015–2017 | Uruguay | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT/IIF | H 140/308 |

| MAT | Dogs 8/50, horses 11/22 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 6/25 | ||||||

| Neela et al (2019) [95] | H, A, E | 2016 | Malaysia | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: gen | MAT/RDT/ IgMELISA | H 4/12 |

| PCR | Rodents 6/12, water 6/18, soil 8/18 | ||||||

| Nadia et al (2019) [96] | H, A | … | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 10/23, monkeys 5/10, shrews 1/1, rodents 4/43 |

| Roqueplo et al (2019) [97] | H, A | 2012–2014 | Senegal | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 42/545, dogs 32/33, cows 17/56, goats 18/52, sheep 3/43, horses 16/20 |

| PCR | Rodents 2/36 | ||||||

| Verma et al (2019) [98] | A, E | 2016–2017 | USA | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Cows 7/21, horses 13/31 |

| PCR | Rabbit 0/1, squirrels 0/1, shrews 3/6, rodents 60/93, water 2/89 | ||||||

| Calderón et al (2019) [99] | H, A | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 4/123, horses 130/153 | |

| Culture | Horses 99/153 | ||||||

| PCR | Horses 0/99+ | ||||||

| Mgode et al (2019) [100] | H, A | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: mix A: gen | MAT | H 72/455, shrews 1/5 rodents 3/21 | |

| Culture | Shrews 0/5, rodents 0/21 | ||||||

| Goh et al (2019) [21] | H, A | … | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 67/194, dogs 70/266, cats 7/47 |

| Rodriguez et al (2020) [101] | H, A | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | IgMELISA | H 25/83 | |

| PCR | Rodents 4/53 | ||||||

| Murcia et al (2020) [102] | H, A | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 2/69, dogs 53/92 | |

| Culture | Dogs 54/92 | ||||||

| Alashraf et al (2020) [103] | H, A | … | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 5/58, dogs 26/127, cats 7/47 |

| Grimm et al (2020) [104] | A, E | 2008–2009 | USA | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | MAT | Feral cats 0/19, opossums 60/112, racoons 121/221 |

| PCR | Water 6/8 | ||||||

| Wójcik-Fatla et al (2020) [105] | A, E | Poland | Prevalence survey | A: gen | ELISA | Cows 0/80, pigs 51/86 | |

| PCR | Air 2/50 | ||||||

| Dushyant et al (2020) [106] | A, E | India | Prevalence survey | A: mix | Culture | Dogs 0/5, cows 0/77, rodents 0/5, water 0/3 | |

| PCR | Dogs 0/10, cows 55/299, water 0/16, soil 0/4 | ||||||

| Van et a (2017) [107] | H, A, E | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | ImmunoC | H 199/280 | |

| PCR | Fish 8/11, water 4/12, soil 9/12 | ||||||

| Ospina-Pinto and Hernández-Rodríguez (2021) [108] | A, E | 2019 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Pigs 58/65 |

| Culture | Pigs 10/65, water 10/15 | ||||||

| PCR | Pigs 10/10+, water 10/10+ | ||||||

| Benitez et al (2021) [109] | H, A | 2015–2016 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 11/597, dogs 155/729 |

| Mgode et al (2021) [110] | H, A | … | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 15/50, goats 28/45, sheep 34/56, rodents 7/45 |

| Machado et al (2021) [111] | H, A | 2016–2018 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 0/49, dogs 18/170, boars 9/74 |

| Dreyfus et al (2021) [112] | H, A | 2015 | Bhutan | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 14/864, dogs 40/84, cows 48/130 |

| Msemwa et al (2021) [113] | H, A | 2018 | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 33/205, dogs 66/414 |

| Medkour et al (2021) [114] | H, A | 2016–2019 | Congo Algeria Senegal Djibouti | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | PCR | H 31/38, Gorilla 46/172 |

| Shamsusah et al (2021) [115] | A, E | 2017–2018 | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Gorilla 1/12, rodents 1/23, soil 22/123, water 7/37 |

| Aghamohammad et al (2022) [116] | H, A | 2019 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: mix | IgGELISA | H 1/51, cows 0/30, goats 1/31, sheep 2/30 |

| Setyaningsih et al (2022) [117] | H, E | 2017–2018 | Indonesia | Case control | H: mix | PCR | H 34 (in case-control studyb), water 6/100 |

| de Souza Rocha et al (2022) [118] | H, A | 2014–2015 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 15/80, dogs 31/85, cats 0/10 |

| PCR | Dogs 13/68 | ||||||

| Cunha et al (2022) [119] | H, A | 2017–2019 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 0/19, dogs 16/264 |

| Richard et al (2022) [120] | A, E | 2018–2020 | France | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 68/189, water 158/1031 |

| do Couto (2022) [121] | H, A | … | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 0/200, dogs 5/40 |

| Meny et al (2022) [122] | H, A | 2017–2020 | Uruguay | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 6/150, horses 546/891 |

Abbreviations: A, animals; ALR, agglutination-lyse reaction; CAR, cross-agglutination reaction; E, environment; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; exp, exposed; feb, febrile; gen, general; H, humans; Ig, immunoglobulin; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; ImmunoC, immunochromatography; MAT, microscopic agglutination test; mix, mixed; NA, not available; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RDT, rapid diagnostic test; risk, at risk;

aPlus signs (+) indicate that tested samples were positive to a previous test.

bCase-control study without number of all tested patients.

Characteristics of One Health Studies on Leptospirosis Included in the Current Review

| Study Authors (Year) . | Type . | Date . | Country . | Design . | Population . | Test . | Positivity Rate . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maronpot and Barsoum (1972) [23] | H, A | 1968–1971 | Egypt | Prevalence survey | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 52/513, cows 209/424, pigs 70/130, goats 135/195, sheep 57/330, horses 11/31, camels 29/50 |

| Nelson et al (1973) [24] | H, A | 1964 | USA | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 61/245, cows 26/305 |

| CAR | Cows 9/43 | ||||||

| Tsai et al (1973) [25] | H, A | 1968 | Taiwan | Prevalence survey | H: gen A: gen | MAT | H 25/167, dogs 0/2, cows 18/57, pigs 0/64, goats 2/32, civets 1/2, rodents 3/47 |

| Culture | Civets 1/2, rodents 7/59 | ||||||

| Limpias and Marcus (1973) [26] | H, A | … | Bolivia | Prevalence survey | H: feb A: mix | MAT | H 7/142, dogs 1/17, cows 372/520, pigs 7/102, goats 4/53, sheep 1/61, horses 76/101, monkeys 1/1, bats 0/9, rabbits 0/1, snakes 0/1, boars 1/1, deer 1/1, rodents 0/3 |

| Ratnam et al (1983) [27] | H, A | India | Cluster investigation | H: mix A: feb | MAT | H 35/75, cows 27/40 | |

| Culture | Cows 0/9 | ||||||

| Prokopcaková and Pospisil (1984) [28] | H, A | … | Slovakia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | ALR | H 28/876, cows 13/168, rodents 20/243 |

| Gelosa and Manera (1984) [29] | H, E | 1980–1983 | Italia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb | MAT | H 34/168 |

| Culture | Water 0/40 | ||||||

| Sebek et al (1987) [30] | H, A | 1976–1982 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 80/2448, cows 2/4, pigs 15/89, goats 6/65, sheep 9/328 |

| Heisey et al (1988) [31] | H, A | 1983–1984 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: feb | MAT/Culture | H 33/110 |

| MAT | Dogs 56/293, cats 0/8, cows 54/204, pigs 3/17, rodents 84/174 | ||||||

| Culture | Cows NA/150, rodents 23/75 | ||||||

| Everard et al (1988) [32] | H, A | 1982–1984 | Belize | Prevalence survey | H: mix A: mix | MAT | H 99/451, dogs 5/7, cows 136/155, pigs 32/71, goats and sheep 88/162 |

| Sebek et al (1989) [33] | H, A | 1987 | Egypt | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 17/196, dogs 0/1, cows 0/1, pigs 4/28, goats 1/67, horses 2/12, rodent 36/65 |

| Sebek et al (1989) [34] | H, A | 1983 | Cape Verde | Prevalence survey | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 44/611, dogs 0/89, cows 3/150, pigs 0/316, goats 34/640, sheep 0/39, horses 3/64, rodents 0/211 |

| Venkataraman and Nedunchelliyan (1992) [35] | H, A | 1988 | India | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 48/95, dogs 20/94, bandicoots 10/24, rodents 8/64 |

| DFM | H 10/48+,a dogs 8/20+, bandicoots 8/24+, rodents 5/32 | ||||||

| Culture | H 1/10+, dogs 1/8+ | ||||||

| Prokopcáková et al (1994) [36] | H, A | 1991–1993 | Slovakia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 56/1740, rodents 99/1038, shrews 1/68 |

| Machang’u et al (1997) [37] | H, A | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 1/375, dogs 80/208, cows 28/374, rodents 10/537 | |

| Culture | Cows 7/1021 | ||||||

| Campagnolo et al (2000) [38] | H, A, E | 1998 | USA | Cluster investigation | H: risk; A: feb | IgMELISA | H 9/17 |

| MAT | Pigs 97/302 | ||||||

| Culture | Pigs 4/6, water 0/8 | ||||||

| Ochoa et al (2000) [39] | H, A | 1997–1998 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 15/67, cows 106/174, pigs 60/278 |

| Vanasco et al (2000) [40] | H, A, E | 1998 | Argentina | Cluster investigation | H: mix; A: exp | MAT | H 12/32, dogs 6/8 |

| DFM | Water 8 spirochete+/8 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 8 spirochete+/8 | ||||||

| Ralaiarijaona et al (2001) [41] | H, A | 2000 | Madagascar | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 1/105 |

| PCR | Cows 0/50, pigs 0/13, rodents 0/115 | ||||||

| León et al (2002) [42] | A, E | 1996–1998 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | A: feb | MAT | Pigs 0/68 |

| DFM | Water 91/339 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 38/311 | ||||||

| Natarajaseenivasan et al (2002) [43] | H, A | 2000 | India | Mixed | H: mix; A: gen | IgGELISA | H 241/268 |

| MAT | H 231/338, dogs 2/4, cats 6/9, cows 18/34, rodents 12/23 | ||||||

| Ramakrishnan et al (2003) [44] | H, E | 2001 | India | Cluster investigation | H: exp | MAT | H 20/64 |

| Culture | Water 1/1 | ||||||

| PCR | Water 1/1 | ||||||

| Cerri et al (2003) [45] | H, A | 1995–2001 | Italia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 14/250, dogs 278/4369, cows 7/644, pigs 123/1299, sheep 132/1088, horses 107/938, boars 11/459, deer 0/567, wolves 0/4, marmots 0/120, rodents 0/4 |

| Ren et al (2005) [46] | H, A | 1998–2003 | China | Longitudinal monitoring | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 57/1777, pigs 10/232 |

| Culture | Dogs 0/30, pigs 1/524, rodents 16/123 | ||||||

| Kuriakose et al (2008) [47] | H, A | 1993–1997 | India | Longitudinal monitoring | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 38/376, bandicoot 4/9, shrews 0/5, rodents 2/40 |

| DFM | Bandicoots 2/4, rodents 1/2 | ||||||

| Culture | Bandicoots 0/2, shrews 0/2, rodents 1/6 | ||||||

| Langoni et al (2008) [48] | H, A | 2005 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 8/34, cows 46/140, rodents 0/50 |

| Culture | Cows 0/140, rodents 0/50 | ||||||

| PCR | Rodents 0/50 | ||||||

| Habuš et al (2008) [49] | H, A | 2007 | Croatia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 24/113, dogs 2/20, cows 295/9867, pigs 1397/15524, goats 24/1639, sheep 46/16278, horses 196/1212, foxes 36/70, wild animals (undefined) 0/100 |

| Zhou et al (2009) [50] | H, A | 2002 | China | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 444/772 |

| Culture | Cows 11/225, rodents 22/726 | ||||||

| Aviat et al (2009) [51] | A, E | 2001–2004 | France | Prevalence survey | A: exp | MAT | Rodents 288/649 |

| PCR | Rodents 41/516, water 6/151 | ||||||

| Silva et al (2010) [52] | H, A | 2006 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 0/15, Snake 47/110, Fish 2/25, Bird 34/143, Wild undefined 11/49 |

| Zakeri et al (2010) [53] | H, A | 2005–2007 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 98/369, dogs 33/150, sheep 13/175 |

| Romero et al (2011) [54] | H, A | 2007 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 51/850, dogs 182/850 |

| Bermúdez et al (2010) [55] | H, A | … | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 10/46, dogs 41/61 |

| Cárdenas-Marrufo et al (2011) [56] | A, E | 2004–2005 | Mexico | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Dogs 22/61, cows 97/212, pigs 26/203 |

| PCR | Water 0/68 | ||||||

| De Castro et al (2011) [57] | H, A | 2007–2009 | Brazil | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 7/97, dogs 76/268 |

| Romero et al (2011) [54] | H, A | 2009–2010 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 5/20, monkeys 15/65 |

| Fonzar and Langoni (2012) [58] | H, A | 2006–2008 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 5/25, dogs 41/335 |

| Romero-Vivas et al (2013) [59] | H, A | 2007–2009 | Colombia | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 16/128, dogs 19/83, rodents 13/69 |

| Culture | H 0/10, dogs 0/54, rodents 1/69 | ||||||

| PCR | H 1/10 PCR, dogs 2/4 (2+), rodents 2/16 | ||||||

| Calderón et al (2014) [60] | H, A, E | 2009–2011 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 47/62, dogs 19/54, pigs 214/383, rodents 0/39 |

| Culture | Dogs 2/54, pigs 3/171, rodents 1/39, water 9/57 | ||||||

| PCR | Dogs 2/2+, pigs 3/3+, water 2/9+ | ||||||

| Soman et al (2014) [61] | H, A | India | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 84/154, dogs 44/121, wild animals (undefined) 9/42 | |

| Culture | H 1/154, dogs 1/121, bandicoots 3/11, rodents 2/24 | ||||||

| Vimala et al (2014) [62] | H, A | 2009–2010 | India | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 10/129, rodents 9/24 |

| Silva et al (2014) [63] | H, A | 2013 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 2/10, dogs 6/12, sheep 7/34, horses 6/10, rodents, 1/1, feral cats 0/1, foxes 1/2, tatous 0/16 |

| Assenga et al (2015) [64] | H, A | 2012–2013 | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 80/267, cows 346/1141, goats 22/248, lions 1/2, zebras 0/2, shrews 1/11, rodent 42/207 |

| Samir et al (2015) [65] | H, A, E | Egypt | Cluster investigation | H: exp; A: mix | MAT | H 87/175, dogs 98/168, cows 239/651, sheep 45/99, horses 2/40, camels 0/22, rodents 205/270 | |

| Culture | H 0/175, dogs 19/168, cows 7/651, sheep 0/99, horses 0/40, camels 0/22, rodents 17/270 | ||||||

| PCR | H 0/175, dogs 65/168, cows 7/651, horses 0/40, sheep 0/99, camels 0/22, rodents 65/270, water 10/45 | ||||||

| Da Silva et al (2015) [66] | H, A | 2012 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 11/28, dogs 7/13, cows 6/17, goats 16/37, sheep 16/41, horses 30/57, foxes 6/11, opossums 1/1, tatous 4/4, monkeys 3/4, coatis 2/3, rodents 1/1 |

| Lugo-Chávez et al (2015) [67] | H, A | 2012 | Mexico | Cluster investigation | H: exp; A: gen | MAT | H 22/36, dogs 19/29 |

| Barragan et al (2016) [68] | H, A | 2013–2015 | Ecuador | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 100/680, cows 59/165, pigs 27/128, rodents 3/101 |

| Cibulski and Wollanke (2016) [69] | A, E | … | Germany and Luxembourg | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Shrews 3/67, Mole 1/1, rodents 38/226, water 9/87 |

| Parveen et al (2016) [70] | H, A | India | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 94/244, dogs 4/15, cows 39/86, goats 7/29, rodents 9/23 | |

| Culture | Rodents 2/23 | ||||||

| Habus et al (2017) [71] | H, A | 2009–2014 | Croatia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 395/1917, dogs 85/364, cows 3251/22 669, pigs 2016/18 163, goats and sheep 376/41 752, horses 5595/41 538 |

| Chadsuthi et al (2017) [72] | H, A | 2010–2015 | Thailand | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 471/1990, cows 1133/4080, pigs 356/3138 |

| Pui et al (2017) [73] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 23/107, water 13/324, soil 46/292 |

| Kurilung et al (2017) [74] | H, A, E | 2013–2016 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | Culture | H 0/37, dogs 4/58, cows 1/131, pigs 6/152, goats 0/1, horses 0/1, water 0/14 |

| PCR | H 1/37, dogs 6/58, cows 16/131, pigs 12/152, goats 1/1, water 3/14 | ||||||

| Ensuncho-Hoyos et al (2017) [75] | H, A, E | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 14/20, dogs 5/11, cows 242/325, water 0/39 | |

| Culture | Cows 3/78 | ||||||

| PCR | Cows 3/3+, water 1/39 | ||||||

| Jorge et al (2017) [76] | H, A | 2003–2007 | Brazil | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H NA/997, dogs NA/1176, cows NA/1484, horses NA/240 |

| Meny et al (2017) [77] | H, E | 2010–2016 | Uruguay | Cluster investigation | H: feb | MAT | H 5/302 |

| Culture | H 8/302, water 7/36 | ||||||

| PCR | H 8/8+, water 6/7+ | ||||||

| Pui et al (2017) [78] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 1/31, water 17/210, soil 8/210 |

| Sanhueza et al (2017) [79] | H, A | 2009–2013 | New Zealand | Prevalence survey | H: risk A: gen | MAT | H 12/178, cows 717/1374, sheep 939/2178, Deer 72/1133 |

| Grevemeyer et al (2017) [80] | A, E | … | Saint Kitts and Nevis | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Horses 22/124, water 0/2 |

| Biscornet et al (2017) [81] | H, A | 2013–2015 | Seychelles | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | IgMELISA | H 18/223 |

| MAT | H 19/223 | ||||||

| PCR | H 32/223, dogs 1/24, cats 1/12, rodents 57/739 | ||||||

| Chávez et al (2018) [82] | A, E | 2014–2016 | Nicaragua | Cluster investigation | A: exp | MAT | Dogs NA/159, cats NA/1, cows NA/36, pigs NA/60, horses NA/7 |

| Culture | Dogs NA/75, cows NA/15, pigs NA/22, water 61/129, soil 14/69 | ||||||

| Shrestha et al (2018) [83] | H, A | 2013 | Nepal | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 13/239, dogs 9/20, cows 60/155, goats 31/181, rodents 3/14 |

| Zala et al (2018) [84] | A, E | 2016–2017 | India | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | PCR | Dogs 2/30, cows 20/121, goats 1/40, soil 8/60, water 80/216 |

| Cortez et al (2018) [85] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Peru | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | Culture | Water 1/64 |

| PCR | Rodents 23/97, water 23/64, soil 21/25 | ||||||

| Tabo et al (2018) [86] | H, A | 2015 | Philippines | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 7/46, cows 3/9, pigs 37/69 |

| Ukhovskyi et al (2018) [87] | H, A | 2009–2016 | Ukraine | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 3012/24 990, cats 52 310/1 238 876, pigs 31 181/989 659, horses 6734/70 674 |

| Markovych et al (2019) [88] | H, A | 2005–2015 | Ukraine | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 401/2079, rodents 276/2820 |

| Takhampunya et al (2019) [89] | H, A | 2014–2018 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 3 pools/23 pools (200), rodents 3pools/64pools (309) |

| Salmon-Mulanovich (2019) [90] | H, A | 2011–2014 | Peru | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 229/2165, dogs 44/53, cats 2/10, Poultry 30/37, rodents 2/30 |

| Jittimanee and Wongbutdee (2019) [91] | A, E | 2014–2015 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 0/270, water 0/100 |

| Marinova-Petkova et al (2019) [92] | H, A, E | 2017–2019 | US Virgin Islands | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT/RDT | H 2/78 |

| MAT | Dogs 1/1 | ||||||

| PCR | H 1/2, dogs 0/1, water 1/5 | ||||||

| Bakoss et al (2019) [93] | H, A | … | Slovakia | Cluster investigation | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 12/19, cows 9/15, rodents 2/44 |

| Meny et al (2019) [94] | H, A, E | 2015–2017 | Uruguay | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT/IIF | H 140/308 |

| MAT | Dogs 8/50, horses 11/22 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 6/25 | ||||||

| Neela et al (2019) [95] | H, A, E | 2016 | Malaysia | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: gen | MAT/RDT/ IgMELISA | H 4/12 |

| PCR | Rodents 6/12, water 6/18, soil 8/18 | ||||||

| Nadia et al (2019) [96] | H, A | … | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 10/23, monkeys 5/10, shrews 1/1, rodents 4/43 |

| Roqueplo et al (2019) [97] | H, A | 2012–2014 | Senegal | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 42/545, dogs 32/33, cows 17/56, goats 18/52, sheep 3/43, horses 16/20 |

| PCR | Rodents 2/36 | ||||||

| Verma et al (2019) [98] | A, E | 2016–2017 | USA | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Cows 7/21, horses 13/31 |

| PCR | Rabbit 0/1, squirrels 0/1, shrews 3/6, rodents 60/93, water 2/89 | ||||||

| Calderón et al (2019) [99] | H, A | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 4/123, horses 130/153 | |

| Culture | Horses 99/153 | ||||||

| PCR | Horses 0/99+ | ||||||

| Mgode et al (2019) [100] | H, A | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: mix A: gen | MAT | H 72/455, shrews 1/5 rodents 3/21 | |

| Culture | Shrews 0/5, rodents 0/21 | ||||||

| Goh et al (2019) [21] | H, A | … | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 67/194, dogs 70/266, cats 7/47 |

| Rodriguez et al (2020) [101] | H, A | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | IgMELISA | H 25/83 | |

| PCR | Rodents 4/53 | ||||||

| Murcia et al (2020) [102] | H, A | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 2/69, dogs 53/92 | |

| Culture | Dogs 54/92 | ||||||

| Alashraf et al (2020) [103] | H, A | … | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 5/58, dogs 26/127, cats 7/47 |

| Grimm et al (2020) [104] | A, E | 2008–2009 | USA | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | MAT | Feral cats 0/19, opossums 60/112, racoons 121/221 |

| PCR | Water 6/8 | ||||||

| Wójcik-Fatla et al (2020) [105] | A, E | Poland | Prevalence survey | A: gen | ELISA | Cows 0/80, pigs 51/86 | |

| PCR | Air 2/50 | ||||||

| Dushyant et al (2020) [106] | A, E | India | Prevalence survey | A: mix | Culture | Dogs 0/5, cows 0/77, rodents 0/5, water 0/3 | |

| PCR | Dogs 0/10, cows 55/299, water 0/16, soil 0/4 | ||||||

| Van et a (2017) [107] | H, A, E | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | ImmunoC | H 199/280 | |

| PCR | Fish 8/11, water 4/12, soil 9/12 | ||||||

| Ospina-Pinto and Hernández-Rodríguez (2021) [108] | A, E | 2019 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Pigs 58/65 |

| Culture | Pigs 10/65, water 10/15 | ||||||

| PCR | Pigs 10/10+, water 10/10+ | ||||||

| Benitez et al (2021) [109] | H, A | 2015–2016 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 11/597, dogs 155/729 |

| Mgode et al (2021) [110] | H, A | … | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 15/50, goats 28/45, sheep 34/56, rodents 7/45 |

| Machado et al (2021) [111] | H, A | 2016–2018 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 0/49, dogs 18/170, boars 9/74 |

| Dreyfus et al (2021) [112] | H, A | 2015 | Bhutan | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 14/864, dogs 40/84, cows 48/130 |

| Msemwa et al (2021) [113] | H, A | 2018 | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 33/205, dogs 66/414 |

| Medkour et al (2021) [114] | H, A | 2016–2019 | Congo Algeria Senegal Djibouti | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | PCR | H 31/38, Gorilla 46/172 |

| Shamsusah et al (2021) [115] | A, E | 2017–2018 | Malaysia | Prevalence survey | A: gen | PCR | Gorilla 1/12, rodents 1/23, soil 22/123, water 7/37 |

| Aghamohammad et al (2022) [116] | H, A | 2019 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: mix | IgGELISA | H 1/51, cows 0/30, goats 1/31, sheep 2/30 |

| Setyaningsih et al (2022) [117] | H, E | 2017–2018 | Indonesia | Case control | H: mix | PCR | H 34 (in case-control studyb), water 6/100 |

| de Souza Rocha et al (2022) [118] | H, A | 2014–2015 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 15/80, dogs 31/85, cats 0/10 |

| PCR | Dogs 13/68 | ||||||

| Cunha et al (2022) [119] | H, A | 2017–2019 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 0/19, dogs 16/264 |

| Richard et al (2022) [120] | A, E | 2018–2020 | France | Longitudinal monitoring | A: gen | PCR | Rodents 68/189, water 158/1031 |

| do Couto (2022) [121] | H, A | … | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: risk | MAT | H 0/200, dogs 5/40 |

| Meny et al (2022) [122] | H, A | 2017–2020 | Uruguay | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 6/150, horses 546/891 |

| Study Authors (Year) . | Type . | Date . | Country . | Design . | Population . | Test . | Positivity Rate . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maronpot and Barsoum (1972) [23] | H, A | 1968–1971 | Egypt | Prevalence survey | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 52/513, cows 209/424, pigs 70/130, goats 135/195, sheep 57/330, horses 11/31, camels 29/50 |

| Nelson et al (1973) [24] | H, A | 1964 | USA | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 61/245, cows 26/305 |

| CAR | Cows 9/43 | ||||||

| Tsai et al (1973) [25] | H, A | 1968 | Taiwan | Prevalence survey | H: gen A: gen | MAT | H 25/167, dogs 0/2, cows 18/57, pigs 0/64, goats 2/32, civets 1/2, rodents 3/47 |

| Culture | Civets 1/2, rodents 7/59 | ||||||

| Limpias and Marcus (1973) [26] | H, A | … | Bolivia | Prevalence survey | H: feb A: mix | MAT | H 7/142, dogs 1/17, cows 372/520, pigs 7/102, goats 4/53, sheep 1/61, horses 76/101, monkeys 1/1, bats 0/9, rabbits 0/1, snakes 0/1, boars 1/1, deer 1/1, rodents 0/3 |

| Ratnam et al (1983) [27] | H, A | India | Cluster investigation | H: mix A: feb | MAT | H 35/75, cows 27/40 | |

| Culture | Cows 0/9 | ||||||

| Prokopcaková and Pospisil (1984) [28] | H, A | … | Slovakia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | ALR | H 28/876, cows 13/168, rodents 20/243 |

| Gelosa and Manera (1984) [29] | H, E | 1980–1983 | Italia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb | MAT | H 34/168 |

| Culture | Water 0/40 | ||||||

| Sebek et al (1987) [30] | H, A | 1976–1982 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 80/2448, cows 2/4, pigs 15/89, goats 6/65, sheep 9/328 |

| Heisey et al (1988) [31] | H, A | 1983–1984 | Thailand | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: feb | MAT/Culture | H 33/110 |

| MAT | Dogs 56/293, cats 0/8, cows 54/204, pigs 3/17, rodents 84/174 | ||||||

| Culture | Cows NA/150, rodents 23/75 | ||||||

| Everard et al (1988) [32] | H, A | 1982–1984 | Belize | Prevalence survey | H: mix A: mix | MAT | H 99/451, dogs 5/7, cows 136/155, pigs 32/71, goats and sheep 88/162 |

| Sebek et al (1989) [33] | H, A | 1987 | Egypt | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 17/196, dogs 0/1, cows 0/1, pigs 4/28, goats 1/67, horses 2/12, rodent 36/65 |

| Sebek et al (1989) [34] | H, A | 1983 | Cape Verde | Prevalence survey | H: mix; A: gen | MAT | H 44/611, dogs 0/89, cows 3/150, pigs 0/316, goats 34/640, sheep 0/39, horses 3/64, rodents 0/211 |

| Venkataraman and Nedunchelliyan (1992) [35] | H, A | 1988 | India | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 48/95, dogs 20/94, bandicoots 10/24, rodents 8/64 |

| DFM | H 10/48+,a dogs 8/20+, bandicoots 8/24+, rodents 5/32 | ||||||

| Culture | H 1/10+, dogs 1/8+ | ||||||

| Prokopcáková et al (1994) [36] | H, A | 1991–1993 | Slovakia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 56/1740, rodents 99/1038, shrews 1/68 |

| Machang’u et al (1997) [37] | H, A | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 1/375, dogs 80/208, cows 28/374, rodents 10/537 | |

| Culture | Cows 7/1021 | ||||||

| Campagnolo et al (2000) [38] | H, A, E | 1998 | USA | Cluster investigation | H: risk; A: feb | IgMELISA | H 9/17 |

| MAT | Pigs 97/302 | ||||||

| Culture | Pigs 4/6, water 0/8 | ||||||

| Ochoa et al (2000) [39] | H, A | 1997–1998 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 15/67, cows 106/174, pigs 60/278 |

| Vanasco et al (2000) [40] | H, A, E | 1998 | Argentina | Cluster investigation | H: mix; A: exp | MAT | H 12/32, dogs 6/8 |

| DFM | Water 8 spirochete+/8 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 8 spirochete+/8 | ||||||

| Ralaiarijaona et al (2001) [41] | H, A | 2000 | Madagascar | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 1/105 |

| PCR | Cows 0/50, pigs 0/13, rodents 0/115 | ||||||

| León et al (2002) [42] | A, E | 1996–1998 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | A: feb | MAT | Pigs 0/68 |

| DFM | Water 91/339 | ||||||

| Culture | Water 38/311 | ||||||

| Natarajaseenivasan et al (2002) [43] | H, A | 2000 | India | Mixed | H: mix; A: gen | IgGELISA | H 241/268 |

| MAT | H 231/338, dogs 2/4, cats 6/9, cows 18/34, rodents 12/23 | ||||||

| Ramakrishnan et al (2003) [44] | H, E | 2001 | India | Cluster investigation | H: exp | MAT | H 20/64 |

| Culture | Water 1/1 | ||||||

| PCR | Water 1/1 | ||||||

| Cerri et al (2003) [45] | H, A | 1995–2001 | Italia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: feb | MAT | H 14/250, dogs 278/4369, cows 7/644, pigs 123/1299, sheep 132/1088, horses 107/938, boars 11/459, deer 0/567, wolves 0/4, marmots 0/120, rodents 0/4 |

| Ren et al (2005) [46] | H, A | 1998–2003 | China | Longitudinal monitoring | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 57/1777, pigs 10/232 |

| Culture | Dogs 0/30, pigs 1/524, rodents 16/123 | ||||||

| Kuriakose et al (2008) [47] | H, A | 1993–1997 | India | Longitudinal monitoring | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 38/376, bandicoot 4/9, shrews 0/5, rodents 2/40 |

| DFM | Bandicoots 2/4, rodents 1/2 | ||||||

| Culture | Bandicoots 0/2, shrews 0/2, rodents 1/6 | ||||||

| Langoni et al (2008) [48] | H, A | 2005 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 8/34, cows 46/140, rodents 0/50 |

| Culture | Cows 0/140, rodents 0/50 | ||||||

| PCR | Rodents 0/50 | ||||||

| Habuš et al (2008) [49] | H, A | 2007 | Croatia | Laboratory monitoring | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 24/113, dogs 2/20, cows 295/9867, pigs 1397/15524, goats 24/1639, sheep 46/16278, horses 196/1212, foxes 36/70, wild animals (undefined) 0/100 |

| Zhou et al (2009) [50] | H, A | 2002 | China | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 444/772 |

| Culture | Cows 11/225, rodents 22/726 | ||||||

| Aviat et al (2009) [51] | A, E | 2001–2004 | France | Prevalence survey | A: exp | MAT | Rodents 288/649 |

| PCR | Rodents 41/516, water 6/151 | ||||||

| Silva et al (2010) [52] | H, A | 2006 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 0/15, Snake 47/110, Fish 2/25, Bird 34/143, Wild undefined 11/49 |

| Zakeri et al (2010) [53] | H, A | 2005–2007 | Iran | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 98/369, dogs 33/150, sheep 13/175 |

| Romero et al (2011) [54] | H, A | 2007 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 51/850, dogs 182/850 |

| Bermúdez et al (2010) [55] | H, A | … | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 10/46, dogs 41/61 |

| Cárdenas-Marrufo et al (2011) [56] | A, E | 2004–2005 | Mexico | Prevalence survey | A: gen | MAT | Dogs 22/61, cows 97/212, pigs 26/203 |

| PCR | Water 0/68 | ||||||

| De Castro et al (2011) [57] | H, A | 2007–2009 | Brazil | Mixed | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 7/97, dogs 76/268 |

| Romero et al (2011) [54] | H, A | 2009–2010 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 5/20, monkeys 15/65 |

| Fonzar and Langoni (2012) [58] | H, A | 2006–2008 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 5/25, dogs 41/335 |

| Romero-Vivas et al (2013) [59] | H, A | 2007–2009 | Colombia | Cluster investigation | H: feb; A: exp | MAT | H 16/128, dogs 19/83, rodents 13/69 |

| Culture | H 0/10, dogs 0/54, rodents 1/69 | ||||||

| PCR | H 1/10 PCR, dogs 2/4 (2+), rodents 2/16 | ||||||

| Calderón et al (2014) [60] | H, A, E | 2009–2011 | Colombia | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 47/62, dogs 19/54, pigs 214/383, rodents 0/39 |

| Culture | Dogs 2/54, pigs 3/171, rodents 1/39, water 9/57 | ||||||

| PCR | Dogs 2/2+, pigs 3/3+, water 2/9+ | ||||||

| Soman et al (2014) [61] | H, A | India | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: mix | MAT | H 84/154, dogs 44/121, wild animals (undefined) 9/42 | |

| Culture | H 1/154, dogs 1/121, bandicoots 3/11, rodents 2/24 | ||||||

| Vimala et al (2014) [62] | H, A | 2009–2010 | India | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | MAT | H 10/129, rodents 9/24 |

| Silva et al (2014) [63] | H, A | 2013 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: risk; A: gen | MAT | H 2/10, dogs 6/12, sheep 7/34, horses 6/10, rodents, 1/1, feral cats 0/1, foxes 1/2, tatous 0/16 |

| Assenga et al (2015) [64] | H, A | 2012–2013 | Tanzania | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 80/267, cows 346/1141, goats 22/248, lions 1/2, zebras 0/2, shrews 1/11, rodent 42/207 |

| Samir et al (2015) [65] | H, A, E | Egypt | Cluster investigation | H: exp; A: mix | MAT | H 87/175, dogs 98/168, cows 239/651, sheep 45/99, horses 2/40, camels 0/22, rodents 205/270 | |

| Culture | H 0/175, dogs 19/168, cows 7/651, sheep 0/99, horses 0/40, camels 0/22, rodents 17/270 | ||||||

| PCR | H 0/175, dogs 65/168, cows 7/651, horses 0/40, sheep 0/99, camels 0/22, rodents 65/270, water 10/45 | ||||||

| Da Silva et al (2015) [66] | H, A | 2012 | Brazil | Prevalence survey | H: gen; A: gen | MAT | H 11/28, dogs 7/13, cows 6/17, goats 16/37, sheep 16/41, horses 30/57, foxes 6/11, opossums 1/1, tatous 4/4, monkeys 3/4, coatis 2/3, rodents 1/1 |

| Lugo-Chávez et al (2015) [67] | H, A | 2012 | Mexico | Cluster investigation | H: exp; A: gen | MAT | H 22/36, dogs 19/29 |

| Barragan et al (2016) [68] | H, A | 2013–2015 | Ecuador | Prevalence survey | H: feb; A: gen | PCR | H 100/680, cows 59/165, pigs 27/128, rodents 3/101 |