-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Samantha Chirunomula, Anahit Muscarella, Kristen Whelchel, Fiona Gispen, David Marcovitz, Katie White, Cody Chastain, Hepatitis C Cascade of Care in a Multidisciplinary Substance Use Bridge Clinic Model in Tennessee, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 11, Issue 5, May 2024, ofae205, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofae205

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Many barriers prevent individuals with substance use disorders from receiving hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment. This study describes 96 patients with active HCV treated in an opioid use disorder bridge clinic model. Of 33 patients who initiated treatment, 25 patients completed treatment, and 13 patients achieved sustained virologic response.

Between 2014 and 2021, the number of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases reported in the United States increased 2-fold [1]. This rise has correlated with increased hospitalizations related to injection of heroin and prescription opioid analgesics [2]. This syndemic highlights the importance of exploring care models that address both substance use and injection-related complications, including HCV.

The hepatitis C cascade of care (CoC) is a care continuum that outlines 7 key steps including diagnosis, linkage, treatment, and sustained virologic response (SVR) [3]. Prior studies have documented barriers to HCV care that exist at the patient level (ie, fear of treatment side effects, complex social determinants of health), provider level (ie, concern for reinfection, lack of familiarity with HCV treatment), and systems level (ie, complexity of healthcare system, stigmatization) [4].

The Bridge Clinic at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) is a transitional, hospital-based clinic that provides multispecialty, multidisciplinary outpatient addiction treatment including medication for opioid use disorder for individuals recently hospitalized for complications of substance use [5]. The Bridge Clinic is available to patients referred from the general adult hospital at Vanderbilt with any primary substance use disorder (SUD) (including primary opioid use disorder or primary alcohol use disorder). Patients are followed in Bridge Clinic until they are linked to long-term addiction care through VUMC or community providers. The aim of this study is to characterize the HCV CoC in this care model and identify barriers to advancement through the HCV CoC.

METHODS

This single-center, ambispective cohort study followed all patients enrolled in the Bridge Clinic from 1 July 2020 to 31 December 2021. An ambispective approach was selected to capture both past and future patients because the clinic initiated HCV screening shortly before the study commenced. Collaborative care was delivered by Bridge Clinic staff, including medical assistants, nurses, case managers, pharmacists, physicians, advanced practice practitioners, recovery coaches, and social workers. Patients were seen primarily on site, with telemedicine available for initial pharmacist assessment and counseling prior to initiation of HCV therapy, or rarely for well-established patients or those in skilled nursing facilities. Infectious disease specialty pharmacy team members were available via consultation on site and remotely during clinic hours to provide patient support.

The Bridge Clinic team evaluated each HCV RNA–positive patient in preparation for direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy. Pharmacists performed comprehensive medication management including drug interaction screening, patient education, and treatment monitoring. Workup included assessment of patient readiness for treatment and completion of laboratory tests required prior to initiation of therapy, as recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/Infectious Diseases Society of America (AASLD/IDSA) guidelines [6]. With the assistance of Bridge Clinic social workers and case managers, the pharmacy team facilitated access to DAA therapy through insurance or patient assistance programs. Patients were monitored throughout the steps of the CoC during initial identification of HCV antibody (Ab)–positive and HCV RNA–positive status, HCV treatment approval, HCV treatment initiation, HCV treatment completion, and achievement of sustained virologic response after 12 weeks (SVR12).

Data were gathered from the electronic medical record including demographics (ie, patient age, gender, race, insurance status), social factors (ie, employment status, housing stability), substance use history, characteristics of HCV infection (ie, genotype, fibrosis score, viral load, HCV-related medical complications, prior treatment history, eligibility for simplified treatment as per AASLD/IDSA guidance [6]), and comorbid medical or mental health diagnoses. Information was also collected on reasons for exiting the CoC prematurely. This study was approved by the VUMC Institutional Review Board under exempt status.

RESULTS

During the study period, a total of 230 patients were enrolled in the Bridge Clinic and screened for HCV (Table 1). Of the 230 patients screened, 84 tested negative for HCV Ab, 37 tested positive for HCV Ab but were HCV RNA negative, and 13 tested positive for HCV Ab without additional RNA testing. Of the 96 patients who tested positive for both HCV Ab and HCV RNA, the median age was 39 (interquartile range [IQR], 25.2–62.1) years and 54 patients (56%) were female. Most patients had no insurance (73%) or had an active Medicaid plan (23%). Many patients were experiencing homelessness (44%), and most were unemployed (64%). Mental health diagnoses were documented in 71% of patients. Only 2% of patients were coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus, and 3% of patients were coinfected with hepatitis B virus. Nearly all patients reported use of opioids, and other substance use was also reported (Table 1). There were 3 known patients with cirrhosis (3%), 1 case of which was decompensated. Most patients were treatment naive (n = 92), and 4 patients were treatment experienced (n = 2 interferon/ribavirin, n = 3 ledipasvir/sofosbuvir). One patient had previously received both interferon/ribavirin and ledipasvir/sofosbuvir.

| Characteristic . | HCV Ab Positive/RNA Positive (n = 96) . |

|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 39.2 (25.2–62.1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 42 (45) |

| Female | 54 (56) |

| Race | |

| White | 91 (95) |

| Black | 4 (4) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Insurance status | |

| Private | 3 (3) |

| Medicaid | 22 (23) |

| Medicare | 1 (1) |

| No insurance | 70 (73) |

| Substance usea | |

| Methamphetamines | 36 (37.5) |

| Heroin | 51 (53) |

| Opioidsb | 68 (71) |

| Cocaine | 24 (25) |

| Other | 29 (30) |

| Housing status | |

| Stable housing | 31 (32) |

| Experiencing homelessnessc | 42 (44) |

| Other/unknown | 23 (24) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed, full-time | 11 (12) |

| Employed, part-time | 3 (3) |

| Unemployed | 61 (64) |

| Other/unknown | 21 (22) |

| Viral coinfections | |

| HIV | 2 (2) |

| HBV | 3 (3) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | |

| Yes | 68 (71) |

| No | 28 (29) |

| Characteristic . | HCV Ab Positive/RNA Positive (n = 96) . |

|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 39.2 (25.2–62.1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 42 (45) |

| Female | 54 (56) |

| Race | |

| White | 91 (95) |

| Black | 4 (4) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Insurance status | |

| Private | 3 (3) |

| Medicaid | 22 (23) |

| Medicare | 1 (1) |

| No insurance | 70 (73) |

| Substance usea | |

| Methamphetamines | 36 (37.5) |

| Heroin | 51 (53) |

| Opioidsb | 68 (71) |

| Cocaine | 24 (25) |

| Other | 29 (30) |

| Housing status | |

| Stable housing | 31 (32) |

| Experiencing homelessnessc | 42 (44) |

| Other/unknown | 23 (24) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed, full-time | 11 (12) |

| Employed, part-time | 3 (3) |

| Unemployed | 61 (64) |

| Other/unknown | 21 (22) |

| Viral coinfections | |

| HIV | 2 (2) |

| HBV | 3 (3) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | |

| Yes | 68 (71) |

| No | 28 (29) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range.

aIndividual subjects may have used >1 type of substance (thus percentages may add up to >100%), and substance use was self-reported.

bOpioids included prescription drugs and/or fentanyl.

cExperiencing homelessness may include living unsheltered, in a shelter, or staying with family/friends.

| Characteristic . | HCV Ab Positive/RNA Positive (n = 96) . |

|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 39.2 (25.2–62.1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 42 (45) |

| Female | 54 (56) |

| Race | |

| White | 91 (95) |

| Black | 4 (4) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Insurance status | |

| Private | 3 (3) |

| Medicaid | 22 (23) |

| Medicare | 1 (1) |

| No insurance | 70 (73) |

| Substance usea | |

| Methamphetamines | 36 (37.5) |

| Heroin | 51 (53) |

| Opioidsb | 68 (71) |

| Cocaine | 24 (25) |

| Other | 29 (30) |

| Housing status | |

| Stable housing | 31 (32) |

| Experiencing homelessnessc | 42 (44) |

| Other/unknown | 23 (24) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed, full-time | 11 (12) |

| Employed, part-time | 3 (3) |

| Unemployed | 61 (64) |

| Other/unknown | 21 (22) |

| Viral coinfections | |

| HIV | 2 (2) |

| HBV | 3 (3) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | |

| Yes | 68 (71) |

| No | 28 (29) |

| Characteristic . | HCV Ab Positive/RNA Positive (n = 96) . |

|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 39.2 (25.2–62.1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 42 (45) |

| Female | 54 (56) |

| Race | |

| White | 91 (95) |

| Black | 4 (4) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Insurance status | |

| Private | 3 (3) |

| Medicaid | 22 (23) |

| Medicare | 1 (1) |

| No insurance | 70 (73) |

| Substance usea | |

| Methamphetamines | 36 (37.5) |

| Heroin | 51 (53) |

| Opioidsb | 68 (71) |

| Cocaine | 24 (25) |

| Other | 29 (30) |

| Housing status | |

| Stable housing | 31 (32) |

| Experiencing homelessnessc | 42 (44) |

| Other/unknown | 23 (24) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed, full-time | 11 (12) |

| Employed, part-time | 3 (3) |

| Unemployed | 61 (64) |

| Other/unknown | 21 (22) |

| Viral coinfections | |

| HIV | 2 (2) |

| HBV | 3 (3) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | |

| Yes | 68 (71) |

| No | 28 (29) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range.

aIndividual subjects may have used >1 type of substance (thus percentages may add up to >100%), and substance use was self-reported.

bOpioids included prescription drugs and/or fentanyl.

cExperiencing homelessness may include living unsheltered, in a shelter, or staying with family/friends.

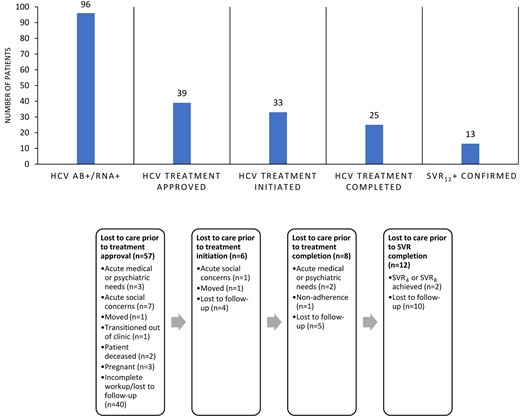

Of the 96 patients with confirmed active HCV, 39 patients (40%) completed workup and were approved for treatment, 33 patients (34%) initiated treatment, 25 patients (26%) completed treatment, and 13 patients (14%) had confirmed SVR. The most common reason that patients were not approved for treatment was that they were lost to follow-up or did not complete workup (42% of patients). Progression through the HCV CoC is presented in Figure 1.

Hepatitis C virus cascade of care within a substance use disorder bridge clinic. Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; HCV, hepatitis C virus; SVR4, sustained virologic response after 4 weeks; SVR8, sustained virologic response after 8 weeks; SVR12, sustained virologic response after 12 weeks.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated a relatively high prevalence of untreated HCV in an opioid use disorder bridge clinic. Using an integrated multidisciplinary program, 25% of those with active HCV completed treatment and 14% achieved confirmed SVR12. The 12 patients who completed treatment but did not have SVR12 data available may have also been cured. The majority of the patients diagnosed with active untreated HCV unfortunately failed to complete workup or were lost to follow-up, preventing progression through the CoC. It is worth noting that despite the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and a patient population with complex social determinants of health including lack of insurance, receipt of DAA therapy was close to previously published rates for insured persons [7]. Additionally, >50% of the cohort included women, suggesting that new strategies for HCV screening could potentially be linked to women's health resources.

The incidence of HCV among people who inject drugs (PWID) has been described often in the literature and ranges from 9.8% to 97% [8]. In high-income countries, up to 80% of new HCV infections occur in PWID and 60% of existing HCV infections affect current and former PWID [9]. This study found a rate of HCV among this PWID population similar to other studies. Because stigma around SUD may prevent patients at the highest risk for HCV infection from reporting their use, we must have a low threshold for HCV screening and address any treatment barriers in this population.

This study also found that the greatest barriers to progression through the CoC included loss to follow-up and other acute medical, psychiatric, or social needs. Despite the services available in the Bridge Clinic to promote retention (eg, recovery coaches to check on patients, social workers to assist with transportation), patients experienced the highest drop-off in care between diagnosis and approval of HCV treatment, most often due to incomplete workup and loss of retention in care. Multiple studies have shown that co-localizing treatment for SUDs and HCV care increases the probability that patients will complete an HCV evaluation [10] and successfully proceed with treatment [11]. However, this study demonstrates that there are still challenges to treating HCV within a bridge clinic model.

Other tools are needed to effectively engage populations with challenging social and medical factors in HCV treatment. Because pangenotypic DAA therapies do not require confirmation of HCV genotype prior to initiation of medication, one potential approach is a rapid-start protocol through which patients receive DAA therapy during their initial clinic visit. Populations who are most likely to benefit from rapid-start HCV treatment include those with less healthcare engagement, those with high risk of transmission, and persons undergoing long-term residential substance use treatment [12]. One study gave patients in a syringe services program a 7-day starter pack of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir but instructed them not to start the medication until they were contacted with confirmation that HCV RNA was positive [13]. Although various types of rapid-start studies have been published, limitations remain in executing these HCV treatment protocols in real-world settings (ie, insurance approval, medication access). Nonetheless, this treatment approach resulted in significantly higher rates of SVR than the majority of studies that have co-localized SUD and HCV treatment, including ours [13]. Rapid-start protocols may represent a promising option to decrease barriers to HCV treatment.

This study does have a number of limitations. The sample size was relatively low with only 96 patients identified as having confirmed active HCV, 33 of whom initiated treatment. The majority of the data collection during this project occurred during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have also limited clinic attendance and engagement. The generalizability of this study is limited based on the unique model of the Bridge Clinic. Additionally, this study was implemented in a large metropolitan area, which may differ from other settings with fewer transportation options.

The need for interventions to increase linkage to care and adherence to HCV treatment among people with SUD has been well-described in the literature. Suggested strategies include integrated care involving case management, peer support, psychological interventions, contingency management, and healthcare providers [14]. Our study demonstrates the utility of HCV evaluation and management in an opioid use disorder bridge clinic model but also highlights the need for additional strategies to facilitate progression through the HCV CoC. Coordinated approaches between various disciplines such as infectious diseases, addiction medicine, and behavioral health can help keep patients engaged in care. Our findings can inform other programs that provide HCV and SUD care.

Notes

Patient consent. This study does not include factors necessitating patient consent.

References

Author notes

S. C. and A. M. contributed equally to this work as joint first authors.

Potential conflicts of interest. D. M. has equity in Better Life Partners LLC and Legion Health LLC. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

Comments