-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nathan Davies, Ilze Bogdanovica, Shaun McGill, Rachael L Murray, What is the Relationship Between Raising the Minimum Legal Sales Age of Tobacco Above 20 and Cigarette Smoking? A Systematic Review, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 27, Issue 3, March 2025, Pages 369–377, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntae206

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

There is considerable interest in raising the age of sale of tobacco above the conventional age of 18 years. We systematically reviewed whether raising the minimum legal sales age of tobacco (MLSA) to 20 or above is associated with a reduced prevalence of smoking compared to an MLSA set at 18 or below.

Following a preregistered protocol on PROSPERO (ref: CRD42022347604), six databases of peer-reviewed journals were searched from January 2015 to April 2024. Backward and forward reference searching was conducted. Included studies assessed the association between MLSAs ≥20 with cigarette smoking or cigarette sales for those aged 11–20 years. Assessments on e-cigarettes were excluded. Pairs of reviewers independently extracted study data. We used ROBINS-I to assess the risk of bias and GRADE to assess the quality of evidence. Findings were also synthesized narratively.

Twenty-three studies were reviewed and 34 estimates of association were extracted. All extracted studies related to Tobacco 21 laws in the United States. Moderate quality evidence was found for reduced cigarette sales, moderate quality evidence was found for reduced current smoking for 18–20-year-olds, and low-quality evidence was found for reduced current smoking for 11–17-year-olds. The positive association was stronger for those with lower education. Study bias was variable.

There is moderate quality evidence that Tobacco 21 can reduce overall cigarette sales and current cigarette smoking amongst those aged 18–20 years. It has the potential to reduce health inequalities. Research in settings other than the United States is required.

This systematic review on raising the minimum legal sale age of tobacco to 20 or above demonstrates there is moderate quality evidence that such laws reduce cigarette sales and moderate quality evidence they reduce smoking prevalence amongst those aged 18–20 years compared to a minimum legal sale age of 18 years or below. The research highlights potential benefits in reducing health inequalities, especially for individuals from lower educational backgrounds. Studies are limited to the United States, highlighting a need for more global research to assess the impact of these policies in other settings.

Introduction

Globally, over 80% of tobacco smokers start smoking aged 15–24 years.1 In 2019, 155 million in this age group were regular tobacco smokers.1 Preventing both initiation and regular tobacco use in this age group, in which individuals are markedly susceptible to addiction,2 is critical to prevent future smoking harm. Minimum legal sales age (MLSA) laws, which prohibit retailers and vendors from selling tobacco products to those under a certain age, are one policy option for reducing access to tobacco products.

There is good historical evidence that raising the MLSA to 18 was associated with reduced smoking rates in the target population in England after implementation in 2007.3–5 It was also linked with reduced commercial tobacco purchases in Finland after implementation in 1995,6 although a study on raised European MLSAs did not find an overall association with smoking prevalence.7 Given the evidence base for raised MLSAs, and the uniquely harmful properties of tobacco, there has been renewed global interest in increasing MLSAs beyond 18.8–12 Article 16 of the World Health Organization Framework Convention for Tobacco Control compels signatories to prohibit the sale of tobacco products to minors but does not specify an exact age limit.13

The first Tobacco 21 (T21) law in the 21st century was introduced in Needham, Massachusetts. Following this, local areas, cities, and states across the United States began to introduce Tobacco 21 (T21) laws14 culminating in a national law being passed in 2019.15 Several other countries, including Ethiopia, Honduras, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Turkmenistan, and Uganda have been reported to introduce an MLSA of at least 20 in recent years.16 In 2024, the Labour government of the United Kingdom announced plans to adopt a law banning the sale of tobacco to anyone born after 2009.17 This policy, known as the smoke-free generation policy, had been tabled by the previous Conservative government but not passed before a general election.18 New Zealand adopted similar legislation in 202119 but a new government reversed the legislation before it could be implemented.20 There have also been issues with the implementation of smoke-free generation laws in Malaysia, due to last-minute changes in the Control of Smoking Products for Public Health Bill,21 and in Denmark, where the European Union tobacco directive has been cited as a potential legal roadblock.22

As policymakers across the globe continue to consider raising MLSA laws as an important component of strategies to reduce tobacco harm, understanding the effectiveness of such policies is of great importance. The main objective of this systematic review was to determine if raising the legal age of sale of tobacco to 20 or above is associated with reduced prevalence of smoking amongst those aged 11–20, compared to a legal age of tobacco set at 18 or below.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in line with a preregistered protocol on PROSPERO (ref: CRD42022347604) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines.23

Selection Criteria

Studies were eligible if they reported the effect on cigarette use of raising the MLSA to 20 or above. They were eligible if the study population included children and young people aged 11–25 years, or if data restricted to this age group could be extracted from the broader study. We excluded studies where an MLSA of 20 or above was introduced where no prior age-of-sale limit previously existed. We excluded qualitative studies and studies that purely reported estimates relating to e-cigarettes. There were no geographical restrictions.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

We searched the electronic databases Embase through OVID, MEDLINE through PubMed, PyscINFO through Ovid, ProQUEST Public Health, ProQUESTION Dissertations and Theses, and CINAHL through Ebscohost, for studies published from January 1, 2015 (the year in which the first study evaluating the local T21 law in Needham, Massachusetts, was published) to April 18, 2024. A full list of search terms is provided in Supplementary File. No restrictions were in place for the observational period or language. Records were extracted into Rayyan24 and de-deduplicated. Two of the three reviewers (ND, IB, and RM) screened titles and abstracts, and subsequently full texts, to identify eligible studies. ND hand-searched reference lists of identified studies to identify any additional studies. The conflict was settled by discussion or by adjudication from the third screener.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A standard data extraction form was piloted and used to record details for each eligible study by two reviewers (ND and IB). Two of three reviewers (ND, RM, and SM) independently assessed quality using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies—of Interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool25 with conflict resolved by discussion and adjudication from a third reviewer where necessary. Studies were given a risk of bias score for seven domains between “low” and “critical” and given an overall risk of bias score.

Data Synthesis

We planned to conduct a meta-analysis and related sensitivity analyses. However, the data was not found to be suitable for meta-analysis. Even after approaching authors for further information, many studies eligible for inclusion used measures of effect that could not be harmonized, including several studies with a moderate risk of bias. Furthermore, studies included very heterogeneous population groups, comparators, and outcome measures.

Instead, GRADE criteria26 were used to report confidence in overall estimates of the effect for cigarette sales and for current smoking in two preplanned subgroups, those aged 18–20 and those aged under 18 years. A narrative synthesis was also conducted. This followed the process of developing a preliminary synthesis, exploring relationships within and between studies through visual tabulation of intervention type, population characteristics, measures of effect, and whether a statistically significant association was found between current smoking or cigarette sales and T21. The robustness of the synthesis was assessed by considering the quality of included studies.27 As no primary patient-level data was used, ethical approval was not required.

Results

Overview of Included Studies

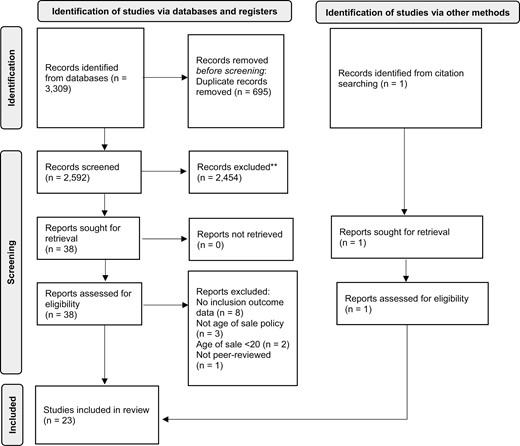

Database searches identified 3309 papers, of which 2592 were unique papers. Thirty-eight papers remained after title and abstract screening. Fifteen were judged ineligible in the full-text review; eight papers had no outcome data, four papers did not relate to age-of-sale policy, two papers related to age-of-sale policies restricting sales to those under 20 only, and one was not peer-reviewed. In total, 23 papers were included (Figure 1).

Thirty-four estimates of the association of the policy with current smoking or cigarette sales were extracted from the 23 included studies28–50 (Tables 1 and 2). Full data extraction is available at https://www.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8D4TB.

Included Estimates of Association by Design, Intervention Level, Age Group, Population Size, and Risk of Bias

| Study author . | Design . | Intervention level . | Intervention age group . | Sample size . | Risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman 201928 | One-off cross-sectional | Local and state | 18–20 year olds | 1869 | Serious |

| Macinko 201829 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 7–12 graders | 76 668 | Moderate |

| Macinko 201829 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 9–12 graders | 71 214 | Serious |

| Garcia-Ramirez 202230 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 229 401 | Moderate |

| Friedman 202031 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local | 18–20 year olds | 25 066 | Moderate |

| Agaku 202232 | One-off cross-sectional | State | 18–20 year olds | 10 146 | Serious |

| Agaku 202232 | One-off cross-sectional | State | 9–12 graders | 182 491 | Serious |

| Dove 202133 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 18-20 year olds | 15 863 | Serious |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 8 graders | 92 922 | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 10 graders | 88 628 | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 12 graders | 81 082 | Moderate |

| Roberts 202235 | Cohort study | City | First-year university | 1140 | Critical |

| Grube 202136 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 956 054 | Moderate |

| Glover-Kudon 202137 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (Hawaii) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Glover-Kudon 202137 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (California) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Schneider 201638 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local | 9–12 graders | 16 385 to 17 089 | Critical |

| Schiff 202139 | Cohort study | State | 19–20 year olds | 3111 | Critical |

| Hawkins 202240 | Repeated cross-sectional | County | 9–12 graders | 9988 | Moderate |

| Liber 202241 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | Designated market areas | N/A | N/A | Moderate |

| Ali 202042 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (California) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Ali 202042 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (Hawaii) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Patel 202343 | Cohort study | Local, city, or state | 15–21 year olds | 13 990 | Moderate |

| Wilhelm 202144 | Repeated cross-sectional | City or county | 8 and 9 graders | 210 177 | Serious |

| Wilhelm 202144 | Repeated cross-sectional | City or county | 11 graders | 210 177 | Serious |

| Yan 201445 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 20 year olds | 60 710 | Moderate |

| Trapl 202246 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 9–12 graders | 12 616 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Repeated cross-sectional | 53 918 | 8 and 10 graders | 53 918 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Repeated cross-sectional | 21 516 | 12 graders | 21 516 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | N/A | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Hansen 202350 | Repeated cross-sectional | 95 557 | 18–20 year olds | 95 557 | Moderate |

| Hansen 202350 | Repeated cross-sectional | 87 612 | 18–20 year olds | 87 612 | Moderate |

| Tennekoon 202347 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 18–20 year old (pregnant) | 2 140 600 | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | Cohort study | Local, substate, state | 18–20 year olds | 55 775 | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, substate, state, federal | 18–20 year olds | Unknown | Serious |

| Study author . | Design . | Intervention level . | Intervention age group . | Sample size . | Risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman 201928 | One-off cross-sectional | Local and state | 18–20 year olds | 1869 | Serious |

| Macinko 201829 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 7–12 graders | 76 668 | Moderate |

| Macinko 201829 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 9–12 graders | 71 214 | Serious |

| Garcia-Ramirez 202230 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 229 401 | Moderate |

| Friedman 202031 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local | 18–20 year olds | 25 066 | Moderate |

| Agaku 202232 | One-off cross-sectional | State | 18–20 year olds | 10 146 | Serious |

| Agaku 202232 | One-off cross-sectional | State | 9–12 graders | 182 491 | Serious |

| Dove 202133 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 18-20 year olds | 15 863 | Serious |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 8 graders | 92 922 | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 10 graders | 88 628 | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 12 graders | 81 082 | Moderate |

| Roberts 202235 | Cohort study | City | First-year university | 1140 | Critical |

| Grube 202136 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 956 054 | Moderate |

| Glover-Kudon 202137 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (Hawaii) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Glover-Kudon 202137 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (California) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Schneider 201638 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local | 9–12 graders | 16 385 to 17 089 | Critical |

| Schiff 202139 | Cohort study | State | 19–20 year olds | 3111 | Critical |

| Hawkins 202240 | Repeated cross-sectional | County | 9–12 graders | 9988 | Moderate |

| Liber 202241 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | Designated market areas | N/A | N/A | Moderate |

| Ali 202042 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (California) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Ali 202042 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (Hawaii) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Patel 202343 | Cohort study | Local, city, or state | 15–21 year olds | 13 990 | Moderate |

| Wilhelm 202144 | Repeated cross-sectional | City or county | 8 and 9 graders | 210 177 | Serious |

| Wilhelm 202144 | Repeated cross-sectional | City or county | 11 graders | 210 177 | Serious |

| Yan 201445 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 20 year olds | 60 710 | Moderate |

| Trapl 202246 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 9–12 graders | 12 616 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Repeated cross-sectional | 53 918 | 8 and 10 graders | 53 918 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Repeated cross-sectional | 21 516 | 12 graders | 21 516 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | N/A | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Hansen 202350 | Repeated cross-sectional | 95 557 | 18–20 year olds | 95 557 | Moderate |

| Hansen 202350 | Repeated cross-sectional | 87 612 | 18–20 year olds | 87 612 | Moderate |

| Tennekoon 202347 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 18–20 year old (pregnant) | 2 140 600 | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | Cohort study | Local, substate, state | 18–20 year olds | 55 775 | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, substate, state, federal | 18–20 year olds | Unknown | Serious |

*per survey, four surveys.

Included Estimates of Association by Design, Intervention Level, Age Group, Population Size, and Risk of Bias

| Study author . | Design . | Intervention level . | Intervention age group . | Sample size . | Risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman 201928 | One-off cross-sectional | Local and state | 18–20 year olds | 1869 | Serious |

| Macinko 201829 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 7–12 graders | 76 668 | Moderate |

| Macinko 201829 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 9–12 graders | 71 214 | Serious |

| Garcia-Ramirez 202230 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 229 401 | Moderate |

| Friedman 202031 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local | 18–20 year olds | 25 066 | Moderate |

| Agaku 202232 | One-off cross-sectional | State | 18–20 year olds | 10 146 | Serious |

| Agaku 202232 | One-off cross-sectional | State | 9–12 graders | 182 491 | Serious |

| Dove 202133 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 18-20 year olds | 15 863 | Serious |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 8 graders | 92 922 | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 10 graders | 88 628 | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 12 graders | 81 082 | Moderate |

| Roberts 202235 | Cohort study | City | First-year university | 1140 | Critical |

| Grube 202136 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 956 054 | Moderate |

| Glover-Kudon 202137 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (Hawaii) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Glover-Kudon 202137 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (California) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Schneider 201638 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local | 9–12 graders | 16 385 to 17 089 | Critical |

| Schiff 202139 | Cohort study | State | 19–20 year olds | 3111 | Critical |

| Hawkins 202240 | Repeated cross-sectional | County | 9–12 graders | 9988 | Moderate |

| Liber 202241 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | Designated market areas | N/A | N/A | Moderate |

| Ali 202042 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (California) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Ali 202042 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (Hawaii) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Patel 202343 | Cohort study | Local, city, or state | 15–21 year olds | 13 990 | Moderate |

| Wilhelm 202144 | Repeated cross-sectional | City or county | 8 and 9 graders | 210 177 | Serious |

| Wilhelm 202144 | Repeated cross-sectional | City or county | 11 graders | 210 177 | Serious |

| Yan 201445 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 20 year olds | 60 710 | Moderate |

| Trapl 202246 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 9–12 graders | 12 616 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Repeated cross-sectional | 53 918 | 8 and 10 graders | 53 918 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Repeated cross-sectional | 21 516 | 12 graders | 21 516 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | N/A | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Hansen 202350 | Repeated cross-sectional | 95 557 | 18–20 year olds | 95 557 | Moderate |

| Hansen 202350 | Repeated cross-sectional | 87 612 | 18–20 year olds | 87 612 | Moderate |

| Tennekoon 202347 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 18–20 year old (pregnant) | 2 140 600 | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | Cohort study | Local, substate, state | 18–20 year olds | 55 775 | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, substate, state, federal | 18–20 year olds | Unknown | Serious |

| Study author . | Design . | Intervention level . | Intervention age group . | Sample size . | Risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman 201928 | One-off cross-sectional | Local and state | 18–20 year olds | 1869 | Serious |

| Macinko 201829 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 7–12 graders | 76 668 | Moderate |

| Macinko 201829 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 9–12 graders | 71 214 | Serious |

| Garcia-Ramirez 202230 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 229 401 | Moderate |

| Friedman 202031 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local | 18–20 year olds | 25 066 | Moderate |

| Agaku 202232 | One-off cross-sectional | State | 18–20 year olds | 10 146 | Serious |

| Agaku 202232 | One-off cross-sectional | State | 9–12 graders | 182 491 | Serious |

| Dove 202133 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 18-20 year olds | 15 863 | Serious |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 8 graders | 92 922 | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 10 graders | 88 628 | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, county, and state laws | 12 graders | 81 082 | Moderate |

| Roberts 202235 | Cohort study | City | First-year university | 1140 | Critical |

| Grube 202136 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 956 054 | Moderate |

| Glover-Kudon 202137 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (Hawaii) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Glover-Kudon 202137 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (California) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Schneider 201638 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local | 9–12 graders | 16 385 to 17 089 | Critical |

| Schiff 202139 | Cohort study | State | 19–20 year olds | 3111 | Critical |

| Hawkins 202240 | Repeated cross-sectional | County | 9–12 graders | 9988 | Moderate |

| Liber 202241 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | Designated market areas | N/A | N/A | Moderate |

| Ali 202042 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (California) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Ali 202042 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | State (Hawaii) | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Patel 202343 | Cohort study | Local, city, or state | 15–21 year olds | 13 990 | Moderate |

| Wilhelm 202144 | Repeated cross-sectional | City or county | 8 and 9 graders | 210 177 | Serious |

| Wilhelm 202144 | Repeated cross-sectional | City or county | 11 graders | 210 177 | Serious |

| Yan 201445 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 20 year olds | 60 710 | Moderate |

| Trapl 202246 | Repeated cross-sectional | City | 9–12 graders | 12 616 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Repeated cross-sectional | 53 918 | 8 and 10 graders | 53 918 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Repeated cross-sectional | 21 516 | 12 graders | 21 516 | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | Longitudinal cigarette sales data | N/A | N/A | N/A | Serious |

| Hansen 202350 | Repeated cross-sectional | 95 557 | 18–20 year olds | 95 557 | Moderate |

| Hansen 202350 | Repeated cross-sectional | 87 612 | 18–20 year olds | 87 612 | Moderate |

| Tennekoon 202347 | Repeated cross-sectional | State | 18–20 year old (pregnant) | 2 140 600 | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | Cohort study | Local, substate, state | 18–20 year olds | 55 775 | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | Repeated cross-sectional | Local, substate, state, federal | 18–20 year olds | Unknown | Serious |

*per survey, four surveys.

Included Estimates of Association by Age Group, Sample Size, Outcome, Direction of Association, and Risk of Bias

| Study author . | Intervention age group . | Sample size . | Outcome . | Direction of association . | Risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman 201928 | 18–20 year olds | 1869 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.6 (0.39, 0.92)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Macinko 201829 | 7–12 graders | 76 668 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 1.25 (0.88, 1.76) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Macinko 201829 | 9–12 graders | 71 214 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 1.40 (1.10, 1.80)^ | Favors control | Serious |

| Garcia-Ramirez 202230 | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 229 401 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Friedman 202031 | 18-20 year olds | 25,066 | Current cigarette smoking: −0.0306 absolute risk reduction (CI −0.0548 to −0.0063)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Agaku 202232 | 18–20 year olds | 10 146 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 0.58 (0.39, 0.74)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Agaku 202232 | 9–12 graders | 182 491 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 0.70 (0.52, −0.93)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Dove 202133 | 18–20 year olds | 15 863 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 1.01 (0.76, 1.34) | Not significant | Serious |

| Colston 202234 | 8 graders | 92 922 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | 10 graders | 88 628 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | 12 graders | 81 082 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.74 (0.60 to 0.91)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Roberts 202235 | First-year university students | 1140 | Current cigarette smoking: 4.1% (interv) 6.6% (control) | Not significant | Critical |

| Grube 202136 | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 956 054 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Glover-Kudon 2021 (Hawaii)37 | N/A | N/A | Change in average monthly unit sales: intervention −4.4%, control −10.6% | Not tested | Serious |

| Glover-Kudon 2021 (California)37 | N/A | N/A | Change in average monthly unit sales: intervention −11.7%, control −10.6% | NA | Serious |

| Schneider 201638 | 9–12 graders | 16 385 to 17,089* | Current cigarette smoking: 12.9% to 6.7% (intervention) 14.8% to 12.0% (control); p < .01^ | Favors intervention | Critical |

| Schiff 202139 | 19–20 year olds | 3111 | Past 30-day use, cigarette: Pre T21 = 150 (9.6%) Post T-21 = 164 (11.1%) | Not tested | Critical |

| Hawkins 202240 | 9–12 graders | 9988 | Current cigarette smoking: Inflation model 0.12 (−1.34 to 0.11) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Liber 202241 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference: Cigarette brand sales: −0.000156 (p = < .001)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Ali 2020 (California)42 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference of cigarette sales: −9.41 (−15.52, −3.30)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Ali 2020 (Hawaii)42 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference of cigarette sales: −0.57 (−0.83, −0.30)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Patel 202343 | 15–21 year olds | 13 990 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.90 (CI: 0.72 to 1.14) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Wilhelm 202144 | 8 and 9 graders | 210 177 | Current cigarette use, 8/9 grade: AOR 0.81 (0.67, 0.99)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Wilhelm 202144 | 11 graders | 210 177 | Cigarettes, 11 grade: AOR 1.2 (0.97, 1.48) | Not significant | Serious |

| Yan 201445 | 20 year olds | 60 710 | Prenatal smoking: 0.013 (SE = 0.010) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Trapl 202246 | 9–12 graders | 12 616 | Adjusted current cigarette smoking: (β = 0.04 [SE = 0.07]; p = .56) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | 8 and 10 graders | 53 918 | Cigarette use past month: −.0100 (SE = 0.0071) (Table 3, column 2) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | 12 graders | 21 516 | Cigarette use past month: −0.0208 (SE = 0.0100), p = < .05 | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | N/A | N/A | Cigarette sales: −.00714 (0.0334) (p < .05) | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Hansen 202350 | 18–20 year olds | 95 557 | Smoking participation: −0.037 (SE = 0.009), p = < .01 | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Hansen 202350 | 18–20 year olds | 87 612 | Smoking participation: −0.009 (SE = 0.019) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Tennekoon 202347 | 18–20 year old (pregnant) | 2 140 600 | Current smoking at the beginning of pregnancy: −0.0574 (0.0009), p ≤ .01 | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | 18–20 year olds | 55 775 | Current cigarette use 0.60 (CI 0.45, 0.79), p < .01 | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | 18–20 year olds | Unknown | Current established smoking: 0.38 (0.25, 0.57) | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Study author . | Intervention age group . | Sample size . | Outcome . | Direction of association . | Risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman 201928 | 18–20 year olds | 1869 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.6 (0.39, 0.92)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Macinko 201829 | 7–12 graders | 76 668 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 1.25 (0.88, 1.76) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Macinko 201829 | 9–12 graders | 71 214 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 1.40 (1.10, 1.80)^ | Favors control | Serious |

| Garcia-Ramirez 202230 | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 229 401 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Friedman 202031 | 18-20 year olds | 25,066 | Current cigarette smoking: −0.0306 absolute risk reduction (CI −0.0548 to −0.0063)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Agaku 202232 | 18–20 year olds | 10 146 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 0.58 (0.39, 0.74)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Agaku 202232 | 9–12 graders | 182 491 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 0.70 (0.52, −0.93)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Dove 202133 | 18–20 year olds | 15 863 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 1.01 (0.76, 1.34) | Not significant | Serious |

| Colston 202234 | 8 graders | 92 922 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | 10 graders | 88 628 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | 12 graders | 81 082 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.74 (0.60 to 0.91)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Roberts 202235 | First-year university students | 1140 | Current cigarette smoking: 4.1% (interv) 6.6% (control) | Not significant | Critical |

| Grube 202136 | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 956 054 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Glover-Kudon 2021 (Hawaii)37 | N/A | N/A | Change in average monthly unit sales: intervention −4.4%, control −10.6% | Not tested | Serious |

| Glover-Kudon 2021 (California)37 | N/A | N/A | Change in average monthly unit sales: intervention −11.7%, control −10.6% | NA | Serious |

| Schneider 201638 | 9–12 graders | 16 385 to 17,089* | Current cigarette smoking: 12.9% to 6.7% (intervention) 14.8% to 12.0% (control); p < .01^ | Favors intervention | Critical |

| Schiff 202139 | 19–20 year olds | 3111 | Past 30-day use, cigarette: Pre T21 = 150 (9.6%) Post T-21 = 164 (11.1%) | Not tested | Critical |

| Hawkins 202240 | 9–12 graders | 9988 | Current cigarette smoking: Inflation model 0.12 (−1.34 to 0.11) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Liber 202241 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference: Cigarette brand sales: −0.000156 (p = < .001)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Ali 2020 (California)42 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference of cigarette sales: −9.41 (−15.52, −3.30)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Ali 2020 (Hawaii)42 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference of cigarette sales: −0.57 (−0.83, −0.30)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Patel 202343 | 15–21 year olds | 13 990 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.90 (CI: 0.72 to 1.14) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Wilhelm 202144 | 8 and 9 graders | 210 177 | Current cigarette use, 8/9 grade: AOR 0.81 (0.67, 0.99)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Wilhelm 202144 | 11 graders | 210 177 | Cigarettes, 11 grade: AOR 1.2 (0.97, 1.48) | Not significant | Serious |

| Yan 201445 | 20 year olds | 60 710 | Prenatal smoking: 0.013 (SE = 0.010) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Trapl 202246 | 9–12 graders | 12 616 | Adjusted current cigarette smoking: (β = 0.04 [SE = 0.07]; p = .56) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | 8 and 10 graders | 53 918 | Cigarette use past month: −.0100 (SE = 0.0071) (Table 3, column 2) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | 12 graders | 21 516 | Cigarette use past month: −0.0208 (SE = 0.0100), p = < .05 | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | N/A | N/A | Cigarette sales: −.00714 (0.0334) (p < .05) | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Hansen 202350 | 18–20 year olds | 95 557 | Smoking participation: −0.037 (SE = 0.009), p = < .01 | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Hansen 202350 | 18–20 year olds | 87 612 | Smoking participation: −0.009 (SE = 0.019) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Tennekoon 202347 | 18–20 year old (pregnant) | 2 140 600 | Current smoking at the beginning of pregnancy: −0.0574 (0.0009), p ≤ .01 | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | 18–20 year olds | 55 775 | Current cigarette use 0.60 (CI 0.45, 0.79), p < .01 | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | 18–20 year olds | Unknown | Current established smoking: 0.38 (0.25, 0.57) | Favors intervention | Serious |

(AOR = adjusted odds ratio, APR = adjusted prevalence ratio, ARR = adjusted risk ratio) * per survey, four surveys ^ = statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

Included Estimates of Association by Age Group, Sample Size, Outcome, Direction of Association, and Risk of Bias

| Study author . | Intervention age group . | Sample size . | Outcome . | Direction of association . | Risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman 201928 | 18–20 year olds | 1869 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.6 (0.39, 0.92)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Macinko 201829 | 7–12 graders | 76 668 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 1.25 (0.88, 1.76) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Macinko 201829 | 9–12 graders | 71 214 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 1.40 (1.10, 1.80)^ | Favors control | Serious |

| Garcia-Ramirez 202230 | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 229 401 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Friedman 202031 | 18-20 year olds | 25,066 | Current cigarette smoking: −0.0306 absolute risk reduction (CI −0.0548 to −0.0063)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Agaku 202232 | 18–20 year olds | 10 146 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 0.58 (0.39, 0.74)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Agaku 202232 | 9–12 graders | 182 491 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 0.70 (0.52, −0.93)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Dove 202133 | 18–20 year olds | 15 863 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 1.01 (0.76, 1.34) | Not significant | Serious |

| Colston 202234 | 8 graders | 92 922 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | 10 graders | 88 628 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | 12 graders | 81 082 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.74 (0.60 to 0.91)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Roberts 202235 | First-year university students | 1140 | Current cigarette smoking: 4.1% (interv) 6.6% (control) | Not significant | Critical |

| Grube 202136 | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 956 054 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Glover-Kudon 2021 (Hawaii)37 | N/A | N/A | Change in average monthly unit sales: intervention −4.4%, control −10.6% | Not tested | Serious |

| Glover-Kudon 2021 (California)37 | N/A | N/A | Change in average monthly unit sales: intervention −11.7%, control −10.6% | NA | Serious |

| Schneider 201638 | 9–12 graders | 16 385 to 17,089* | Current cigarette smoking: 12.9% to 6.7% (intervention) 14.8% to 12.0% (control); p < .01^ | Favors intervention | Critical |

| Schiff 202139 | 19–20 year olds | 3111 | Past 30-day use, cigarette: Pre T21 = 150 (9.6%) Post T-21 = 164 (11.1%) | Not tested | Critical |

| Hawkins 202240 | 9–12 graders | 9988 | Current cigarette smoking: Inflation model 0.12 (−1.34 to 0.11) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Liber 202241 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference: Cigarette brand sales: −0.000156 (p = < .001)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Ali 2020 (California)42 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference of cigarette sales: −9.41 (−15.52, −3.30)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Ali 2020 (Hawaii)42 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference of cigarette sales: −0.57 (−0.83, −0.30)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Patel 202343 | 15–21 year olds | 13 990 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.90 (CI: 0.72 to 1.14) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Wilhelm 202144 | 8 and 9 graders | 210 177 | Current cigarette use, 8/9 grade: AOR 0.81 (0.67, 0.99)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Wilhelm 202144 | 11 graders | 210 177 | Cigarettes, 11 grade: AOR 1.2 (0.97, 1.48) | Not significant | Serious |

| Yan 201445 | 20 year olds | 60 710 | Prenatal smoking: 0.013 (SE = 0.010) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Trapl 202246 | 9–12 graders | 12 616 | Adjusted current cigarette smoking: (β = 0.04 [SE = 0.07]; p = .56) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | 8 and 10 graders | 53 918 | Cigarette use past month: −.0100 (SE = 0.0071) (Table 3, column 2) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | 12 graders | 21 516 | Cigarette use past month: −0.0208 (SE = 0.0100), p = < .05 | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | N/A | N/A | Cigarette sales: −.00714 (0.0334) (p < .05) | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Hansen 202350 | 18–20 year olds | 95 557 | Smoking participation: −0.037 (SE = 0.009), p = < .01 | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Hansen 202350 | 18–20 year olds | 87 612 | Smoking participation: −0.009 (SE = 0.019) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Tennekoon 202347 | 18–20 year old (pregnant) | 2 140 600 | Current smoking at the beginning of pregnancy: −0.0574 (0.0009), p ≤ .01 | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | 18–20 year olds | 55 775 | Current cigarette use 0.60 (CI 0.45, 0.79), p < .01 | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | 18–20 year olds | Unknown | Current established smoking: 0.38 (0.25, 0.57) | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Study author . | Intervention age group . | Sample size . | Outcome . | Direction of association . | Risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedman 201928 | 18–20 year olds | 1869 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.6 (0.39, 0.92)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Macinko 201829 | 7–12 graders | 76 668 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 1.25 (0.88, 1.76) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Macinko 201829 | 9–12 graders | 71 214 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 1.40 (1.10, 1.80)^ | Favors control | Serious |

| Garcia-Ramirez 202230 | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 229 401 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Friedman 202031 | 18-20 year olds | 25,066 | Current cigarette smoking: −0.0306 absolute risk reduction (CI −0.0548 to −0.0063)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Agaku 202232 | 18–20 year olds | 10 146 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 0.58 (0.39, 0.74)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Agaku 202232 | 9–12 graders | 182 491 | Current cigarette smoking: APR 0.70 (0.52, −0.93)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Dove 202133 | 18–20 year olds | 15 863 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 1.01 (0.76, 1.34) | Not significant | Serious |

| Colston 202234 | 8 graders | 92 922 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | 10 graders | 88 628 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Colston 202234 | 12 graders | 81 082 | Current cigarette smoking: ARR 0.74 (0.60 to 0.91)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Roberts 202235 | First-year university students | 1140 | Current cigarette smoking: 4.1% (interv) 6.6% (control) | Not significant | Critical |

| Grube 202136 | 7, 9, and 11 graders | 2 956 054 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Glover-Kudon 2021 (Hawaii)37 | N/A | N/A | Change in average monthly unit sales: intervention −4.4%, control −10.6% | Not tested | Serious |

| Glover-Kudon 2021 (California)37 | N/A | N/A | Change in average monthly unit sales: intervention −11.7%, control −10.6% | NA | Serious |

| Schneider 201638 | 9–12 graders | 16 385 to 17,089* | Current cigarette smoking: 12.9% to 6.7% (intervention) 14.8% to 12.0% (control); p < .01^ | Favors intervention | Critical |

| Schiff 202139 | 19–20 year olds | 3111 | Past 30-day use, cigarette: Pre T21 = 150 (9.6%) Post T-21 = 164 (11.1%) | Not tested | Critical |

| Hawkins 202240 | 9–12 graders | 9988 | Current cigarette smoking: Inflation model 0.12 (−1.34 to 0.11) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Liber 202241 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference: Cigarette brand sales: −0.000156 (p = < .001)^ | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Ali 2020 (California)42 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference of cigarette sales: −9.41 (−15.52, −3.30)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Ali 2020 (Hawaii)42 | N/A | N/A | Absolute adjusted risk difference of cigarette sales: −0.57 (−0.83, −0.30)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Patel 202343 | 15–21 year olds | 13 990 | Current cigarette smoking: AOR 0.90 (CI: 0.72 to 1.14) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Wilhelm 202144 | 8 and 9 graders | 210 177 | Current cigarette use, 8/9 grade: AOR 0.81 (0.67, 0.99)^ | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Wilhelm 202144 | 11 graders | 210 177 | Cigarettes, 11 grade: AOR 1.2 (0.97, 1.48) | Not significant | Serious |

| Yan 201445 | 20 year olds | 60 710 | Prenatal smoking: 0.013 (SE = 0.010) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Trapl 202246 | 9–12 graders | 12 616 | Adjusted current cigarette smoking: (β = 0.04 [SE = 0.07]; p = .56) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | 8 and 10 graders | 53 918 | Cigarette use past month: −.0100 (SE = 0.0071) (Table 3, column 2) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | 12 graders | 21 516 | Cigarette use past month: −0.0208 (SE = 0.0100), p = < .05 | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Abouk 202449 | N/A | N/A | Cigarette sales: −.00714 (0.0334) (p < .05) | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Hansen 202350 | 18–20 year olds | 95 557 | Smoking participation: −0.037 (SE = 0.009), p = < .01 | Favors intervention | Moderate |

| Hansen 202350 | 18–20 year olds | 87 612 | Smoking participation: −0.009 (SE = 0.019) | Not significant | Moderate |

| Tennekoon 202347 | 18–20 year old (pregnant) | 2 140 600 | Current smoking at the beginning of pregnancy: −0.0574 (0.0009), p ≤ .01 | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | 18–20 year olds | 55 775 | Current cigarette use 0.60 (CI 0.45, 0.79), p < .01 | Favors intervention | Serious |

| Friedman 202448 | 18–20 year olds | Unknown | Current established smoking: 0.38 (0.25, 0.57) | Favors intervention | Serious |

(AOR = adjusted odds ratio, APR = adjusted prevalence ratio, ARR = adjusted risk ratio) * per survey, four surveys ^ = statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

The detailed results of the ROBINS-I assessments are set out in Supplementary File. These assessments relate specifically to single effect estimates, not entire studies. Estimates are very unlikely to be graded at a lower risk of bias than “moderate” using the ROBINS-I tool, given residual confounding is almost inevitably introduced in non-randomized studies.25 Sixteen estimates were judged to be of moderate overall risk of bias, 15 of serious risk of bias, and three of critical risk of bias. Sixteen estimates found a statistically significant association favoring T21, 14 estimates were not significant, one estimate favored the control (MLSA of tobacco remaining at 18) and three estimates did not assess statistical significance.

Twenty-eight estimates were based on self-reported current smoking, of which 21 were based on repeated cross-sectional studies, three on one-off cross-sectional studies, and four were based on cohort studies. Six of the estimates were based on cigarette sales data over time.

Using GRADE criteria following the use of ROBINS-I26 we found moderate quality evidence that Tobacco 21 laws reduce overall cigarette sales and that they cause a reduction in current smoking specifically amongst 18–20-year-olds. We found low-quality evidence that Tobacco 21 laws reduce smoking rates amongst 11–17-year-olds (Table 3). All three estimates of quality were downgraded from “high” by the risk of study bias, and evidence for 11–17-year-old current smoking rates was also downgraded by the inconsistency of results.

| Estimates of effect . | Quality of evidence . | Factors that reduce the quality of evidence . | Factors that increase the quality of evidence . | Published studies [reference #] . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction in current smoking amongst 18–20-year-olds | 12 | Moderate | • Risk of bias | None | Friedman (2019); Friedman (2020); Agaku (2022); Dove (2021); Roberts (2022); Schiff (2021); Yan (2014); Abouk (2024); Hansen (2023); Tennekoon (2023); Friedman 2024 [28,31–33,35,39,45,47–50] |

| Reduction in current smoking amongst 11–17 year olds | 15 | Low | • Risk of bias • Inconsistency of results | None | Macinko (2018); Garcia-Ramirez (2022); Agaku (2022); Colston (2022); Grube (2022); Schneider (2016); Hawkins (2022); Wilhelm (2021); Trapl (2022); Abouk (2022) [29,30,32,34,36,38,40,44,46,49] |

| Reduction in cigarette sales | 6 | Moderate | • Risk of bias | None | Glover-Kudon (2021); Liber (2021); Ali (2020); Abouk (2024) [37,41,42,49] |

| Estimates of effect . | Quality of evidence . | Factors that reduce the quality of evidence . | Factors that increase the quality of evidence . | Published studies [reference #] . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction in current smoking amongst 18–20-year-olds | 12 | Moderate | • Risk of bias | None | Friedman (2019); Friedman (2020); Agaku (2022); Dove (2021); Roberts (2022); Schiff (2021); Yan (2014); Abouk (2024); Hansen (2023); Tennekoon (2023); Friedman 2024 [28,31–33,35,39,45,47–50] |

| Reduction in current smoking amongst 11–17 year olds | 15 | Low | • Risk of bias • Inconsistency of results | None | Macinko (2018); Garcia-Ramirez (2022); Agaku (2022); Colston (2022); Grube (2022); Schneider (2016); Hawkins (2022); Wilhelm (2021); Trapl (2022); Abouk (2022) [29,30,32,34,36,38,40,44,46,49] |

| Reduction in cigarette sales | 6 | Moderate | • Risk of bias | None | Glover-Kudon (2021); Liber (2021); Ali (2020); Abouk (2024) [37,41,42,49] |

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence:.

High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate.

| Estimates of effect . | Quality of evidence . | Factors that reduce the quality of evidence . | Factors that increase the quality of evidence . | Published studies [reference #] . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction in current smoking amongst 18–20-year-olds | 12 | Moderate | • Risk of bias | None | Friedman (2019); Friedman (2020); Agaku (2022); Dove (2021); Roberts (2022); Schiff (2021); Yan (2014); Abouk (2024); Hansen (2023); Tennekoon (2023); Friedman 2024 [28,31–33,35,39,45,47–50] |

| Reduction in current smoking amongst 11–17 year olds | 15 | Low | • Risk of bias • Inconsistency of results | None | Macinko (2018); Garcia-Ramirez (2022); Agaku (2022); Colston (2022); Grube (2022); Schneider (2016); Hawkins (2022); Wilhelm (2021); Trapl (2022); Abouk (2022) [29,30,32,34,36,38,40,44,46,49] |

| Reduction in cigarette sales | 6 | Moderate | • Risk of bias | None | Glover-Kudon (2021); Liber (2021); Ali (2020); Abouk (2024) [37,41,42,49] |

| Estimates of effect . | Quality of evidence . | Factors that reduce the quality of evidence . | Factors that increase the quality of evidence . | Published studies [reference #] . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction in current smoking amongst 18–20-year-olds | 12 | Moderate | • Risk of bias | None | Friedman (2019); Friedman (2020); Agaku (2022); Dove (2021); Roberts (2022); Schiff (2021); Yan (2014); Abouk (2024); Hansen (2023); Tennekoon (2023); Friedman 2024 [28,31–33,35,39,45,47–50] |

| Reduction in current smoking amongst 11–17 year olds | 15 | Low | • Risk of bias • Inconsistency of results | None | Macinko (2018); Garcia-Ramirez (2022); Agaku (2022); Colston (2022); Grube (2022); Schneider (2016); Hawkins (2022); Wilhelm (2021); Trapl (2022); Abouk (2022) [29,30,32,34,36,38,40,44,46,49] |

| Reduction in cigarette sales | 6 | Moderate | • Risk of bias | None | Glover-Kudon (2021); Liber (2021); Ali (2020); Abouk (2024) [37,41,42,49] |

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence:.

High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate.

Single Law and Multiple Law Evaluation

Narratively, 18% of analyses evaluating the impact of a single local, city, or state law reported a positive association between T21 and reduced current smoking rates, with 11 of the 17 analyses at serious or critical risk of bias.29,30,33,35–40,42,44–46 This includes the study of New York’s T21 law, which conducted the only analysis to find an association between increased smoking rates and T21.29 However, analyses that evaluated T21 across multiple T21 laws in multiple jurisdictions found significant associations between reduced current cigarette smoking and T21 on 12 of the 17 occasions (71%), with all analyses at moderate or serious risk of bias.28,31,32,34,41,43,47–50

Consideration of Health Inequalities

Six analyses specifically discussed associations of T21 by ethnicity or race in results. The findings were extremely heterogeneous. Agaku32 and Yan45 found that White non-Hispanics were most likely to benefit from T21 laws, Colston34 found Hispanic non-White and other/mixed groups were more likely to benefit, Hansen50 that Black groups were most likely to benefit, Abouk49 that Other groups were more likely to benefit, and Trapl46 found inequity between Black/Hispanic groups and White groups was reduced.

Two analyses at moderate risk of bias considered the differential associations of T21 by education.34,45 Both found that T21 was associated more strongly with reduced cigarette smoking for those with lesser parental or personal education than those with greater parental or personal education.

One study at moderate risk of bias (Garcia-Ramirez) considered differential associations of T21 on current smoking by sexual minority status and found little difference between groups.30

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review assessing the impact of laws raising the MLSA to 20 or above on smoking rates. Studies displayed a high level of heterogeneity in analytical approaches, population groups, and the types of laws enforced.

Our systematic review identified evidence of moderate quality that supports the introduction of T21 laws to reduce cigarette sales. When considering studies with defined age groups, evidence of the policy having an impact on young adults directly covered by the law (18–20-year-olds) was of moderate quality, whilst the evidence that it impacts children indirectly affected (11–17-year-olds) was of low quality. This is supplemented by two recent studies, not included in this systematic review because they did not include data on smoking rates or cigarette sales. One found lower smoking intentions amongst those with knowledge of T21 laws51 and a separate study found that the proportion of youth who perceived easy access to cigarettes significantly decreased following the federal T21 law.52

All studies included in this review were conducted in the United States. One study on retail compliance with the T20 law implemented in Thailand in 2017 which was excluded found that 38% of retailers self-reported selling cigarettes to those under 20s post-implementation.53

There were no studies at low risk of bias, which was expected given that the ROBINS-I assessment tool is extremely unlikely to assess non-randomized studies to be at low risk of bias. There were, however, 34 separate analyses included in this review, which is a relatively rich source of evidence for a single tobacco control policy.

Age appears to mediate the association with T21. The impact of T21 on the ability of 18–20-year-olds and older teens to purchase tobacco or obtain it from peers may be more immediate.51 For younger groups, it is possible that more time is required for T21 policies to change smoking habits, as the policy mechanism may be more reliant on disrupting the supply of tobacco from older groups and wider changes in social norms.37

We found that studies which included multiple T21 laws were more likely to find an association than those that evaluated a single law. Many of the early states and areas that introduced T21 and subsequently evaluated in isolation were already leaders in tobacco control, with relatively low prevalence rates amongst young people, and thus reducing cigarette smoking further is challenging. Many of the studies that focused on multiple areas included the impact of laws in parts of the country which had higher smoking prevalence and thus the scope for reduction in current smoking may have been greater.

There were encouraging findings relating to T21’s potential for reducing educational inequality in smoking, important given the extreme inequity of the impact of tobacco on health.1,54,55 In two analyses at moderate risk of bias, the policy was shown to have reduced disparities in smoking rates between educational groups, despite evidence there is a lower likelihood of ID checks in poorer areas.56 Studies reported heterogeneous differences across racial and ethnic groups, but crucially there was no evidence that white non-Hispanic groups were more likely to benefit from the policy than any other group.

It is important to note that in the United States, rapid and significant increases in e-cigarette use took place during the duration of many of the included studies, along with falls in smoking rates. Only 1.5% of those in grades 9–12 were current cigarette users in 2021.57 Systematically reviewing the literature on the association of T21 laws on e-cigarette use is beyond the scope of this review, but mixed results have been reported. It is possible that this rise affected the impact of T21 laws, although some analyses controlled for e-cigarette use.30,44 The relationship between MLSAs and e-cigarette use needs careful consideration given global increases in e-cigarette use in younger age groups.

T21 is not the only option for countries considering policies based on age of sale. The smoke-free or tobacco-free generation approach, in which the MLSA is effectively raised by one year every year, is a prominent alternative. The United Kingdom has started the process of implementing smoke-free generation laws18 and there are published modeling studies to support smoke-free generation laws in multiple settings in Oceania.58–60

Limitations

We were not able to conduct a meta-analysis which would have provided quantified measures of association and uncertainty. However, the reporting of GRADE assessments and narrative synthesis support an understanding of the strength of evidence and populations for which T21 is likely to have the greatest effect on smoking rates.

It was not clear from most studies how roll-your-own tobacco was categorized, although survey methodologies suggested this would have largely been included under cigarette smoking. This review does not consider e-cigarettes, cigars, or smokeless tobacco products. This may have prevented useful further context on product type; for example, Trapl et al.’s paper found a significant reduction in cigar use in Cleveland compared to surrounding areas, though not cigarettes.46 However, given a proliferation of estimates across product types, a focus on current cigarette smoking enabled a systematic, transparent approach to synthesizing data for the outcome of greatest global relevance, given cigarette smoking is the most common form of tobacco use in this age group.1

Despite having no restriction on geographical location, all included studies were conducted in the United States, and nearly all focused on subnational laws or included a very short window following federal implementation. Research into Tobacco 21 at the federal level in the United States and of MLSAs above 20 in several other countries which have implemented them will be critical to inform wider global tobacco control policymaking.

We did not look in-depth at the design and enforcement of laws and how this affected estimates, which is particularly important for MLSAs.61 For example, California’s law exempted those serving in the military,62 some studies found that T21 implementation was accompanied by a lack of retailer monitoring and enforcement,29,63 and one study found that possession, use, or purchase laws criminalizing young people dampened the effects of T21.48

Conclusions

This review demonstrates that there is moderate quality evidence that T21 policies are associated with both reducing cigarette sales overall and cigarette sales specifically in those aged 18–20. T21 may be more likely to achieve its policy goals when implemented in areas with higher current cigarette smoking rates. T21 may have a greater impact on groups with lower educational status, signifying a possible role in reducing health inequalities. Countries and regions with lower MLSAs should consider raising the age of sale of tobacco as part of a broader tobacco control strategy, paying careful attention to the design, implementation, and enforcement of new laws.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Nicotine and Tobacco Research online.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute for Health and Care Research award 302872.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

Nathan Davies (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [lead], Investigation [lead], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Ilze Bogdanovica (Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [supporting], Validation [equal], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Shaun McGill (Formal analysis [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Validation [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), and Rachael Murray (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [equal], Validation [equal], Writing—review & editing [supporting])

Data Availability

The data underlying this manuscript is available at https://www.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8D4TB

References

ONS. Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2018.

Comments