-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ann M Rusk, Rachel E Giblon, Alanna M Chamberlain, Christi A Patten, Jamie R Felzer, Yvonne T Bui, Chung-Il. Wi, Christopher C Destephano, Barbara A Abbott, Cassie C Kennedy, Smoking Behaviors Among Indigenous Pregnant People Compared to a Matched Regional Cohort, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 25, Issue 5, May 2023, Pages 889–897, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntac240

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Smoking commercial tobacco products is highly prevalent in American Indian and Alaska Native (Indigenous) pregnancies. This disparity directly contributes to maternal and fetal mortality. Our objective was to describe cigarette smoking prevalence, cessation intervention uptake, and cessation behaviors of pregnant Indigenous people compared to sex and age-matched regional cohort.

Pregnancies from an Indigenous cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota, identified in the Rochester Epidemiology Project, were compared to pregnancies identified in a sex and age-matched non-Indigenous cohort from 2006 to 2019. Smoking status was defined as current, former, or never. All pregnancies were reviewed to identify cessation interventions and cessation events. The primary outcome was smoking prevalence during pregnancy, with secondary outcomes measuring uptake of smoking cessation interventions and cessation.

The Indigenous cohort included 57 people with 81 pregnancies, compared to 226 non-Indigenous people with 358 pregnancies. Smoking was identified during 45.7% of Indigenous pregnancies versus 11.2% of non-Indigenous pregnancies (RR: 3.25, 95% CI = 1.98–5.31, p ≤ .0001). Although there was no difference in uptake of cessation interventions between cohorts, smoking cessation was significantly less likely during Indigenous pregnancies compared to non-Indigenous pregnancies (OR: 0.23, 95% CI = 0.07–0.72, p = .012).

Indigenous pregnant people in Olmsted County, Minnesota were more than three times as likely to smoke cigarettes during pregnancy compared to the non-indigenous cohort. Despite equivalent uptake of cessation interventions, Indigenous people were less likely to quit than non-Indigenous people. Understanding why conventional smoking cessation interventions were ineffective at promoting cessation during pregnancy among Indigenous women warrants further study.

Indigenous pregnant people in Olmsted County, Minnesota, were greater than three times more likely to smoke during pregnancy compared to a regional age matched non-Indigenous cohort. Although Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnant people had equivalent uptake of cessation interventions offered during pregnancy, Indigenous people were significantly less likely to quit smoking before fetal delivery. This disparity in the effectiveness of standard of care interventions highlights the need for further study to understand barriers to cessation in pregnant Indigenous people.

Introduction

American Indian and Alaska Native (Indigenous) pregnant people have the highest prevalence of smoking during the last 3 months of pregnancy compared to any race or ethnicity in the U.S., with an estimated prevalence of 26.0% of Indigenous pregnancies.1 Maternal mortality for Indigenous women is 2.3 times higher than White pregnant people.2 The use of smoked commercial tobacco products including cigarettes, cigars, and pipe tobacco products during pregnancy contributes to adverse health outcomes for gestational parents and infants.3 Adverse outcomes associated with use of tobacco during pregnancy include low birth weight, preterm delivery, maternal, and fetal mortality.3,4 Access to prenatal care, rural residence, and numerous other social determinants of health further contribute to adverse maternal health outcomes in Indigenous people.2 Addressing smoking use during pregnancy represents a possible modifiable risk factor to influence maternal and fetal health outcomes.2–4 The uptake of smoking cessation interventions in pregnant Indigenous birthing people compared to a matched regional cohort is not described in current literature. Current data derived from birth records or post-partum surveys describing the prevalence of smoked commercial tobacco products are limited by lack of comparison to the regional non-Indigenous cohort and do not examine the uptake or effectiveness of standard of care smoking cessation interventions.1,5

The American College of Gynecology (ACOG) recommends addressing smoking cessation as an important element of prenatal care.4 Despite the ACOG recommendations to counsel pregnant smokers, national data suggest only 56.7% of pregnant people report receiving physician counseling to quit, and only 3.9% are offered nicotine replacement after the failure of behavioral health interventions.6 The success of smoking cessation interventions during pregnancy results in approximately 54.3% of people achieving cessation during pregnancy.6 There is a paucity of data describing the uptake of cessation interventions for people of color, particularly Indigenous people.1,2,6,7 Prior studies examining novel biomarker feedback cessation interventions in Alaska Native pregnancies revealed no difference in the study group compared to standard of care control group, suggesting standard of care cessation interventions may be effective in Alaska Native pregnancies, but have insufficient uptake to demonstrate meaningful changes in smoking prevalence.8

The primary objective of this study is to define Indigenous smoking behaviors during pregnancy compared to a regionally age-matched non-Indigenous cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Secondary outcomes include reviewing the uptake and effectiveness of standard of care smoking cessation interventions in a pregnant cohort.

Methods

To define cigarette smoking prevalence in pregnant Indigenous people and the uptake and effectiveness of standard of care cessation interventions, a longitudinal cohort of Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnant people in Olmsted County, Minnesota was identified using the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP is a multi-site record linkage system unifying multiple healthcare delivery systems in Olmsted County, Minnesota, allowing an inclusive and holistic review of longitudinal health data.9–11 Examples of health data available for review in the REP includes diagnosis and procedure codes, laboratory values, imaging studies, prescriptions, mortality data, including cause of death, and birth and death certificate data.10 The REP was established in 1966 and represents a validated source of smoking data for review.12 With the inclusion of multiple health systems in Olmsted County, data includes 99.9% of people residing in Olmsted County in 2014 as compared to United States (US) census population estimates.9–13 The REP represents a tool that has been validated for longitudinal data review.11,12 Length of data available for review in the REP varies by age and calendar year, with a median low of 2.7 years duration of data availability for those aged over 90 years, to a high of 9.0 years of data availability for those between the ages of 60 and 69.9–13 The cohort gathered from the REP was also studied in conjunction with measures of social determinants of health. To represent Indigenous populations or any vulnerable population in an equitable manner, it is critical to consider the social determinants of health and the contribution to differences in health outcomes.14,15 Access to stable housing, employment, individual safety, systematic racism, discrimination, and historical trauma are examples of social determinates of health with direct and indirect influences on health outcomes.14 To represent socioeconomic factors, we utilized the HOUsing-based index of SocioEconomic Status (HOUSES) index.16,17 The authors recognize the importance of data sovereignty in Indigenous health research. The research team included Indigenous persons and those familiar with the conduct of equitable research involving Indigenous people. Input from Indigenous communities through the Office of Native American Research within the Center for Health Equity and Community Engagement Research was included during the planning of the project and results interpretation.

Subject Eligibility

This study was conducted with Institutional Review Board approval from Mayo Clinic (#20-000642) and Olmsted Medical Center (#019-OMC-20). This study was conducted with patients identified utilizing the REP medical records-linkage system. The date range of data review was January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2019, to capture uniform conversion to an electronic medical record among multisite inclusion regions in Olmsted County. Pediatric patients who reached age 18 during the study period were included. Individuals with any record indicating Indigenous, American Indian, Native American, First Nations, or Alaska Native race or ethnicity were included in the Indigenous cohort. To remove patients who incorrectly self-identified as Indigenous (eg, self-reported as American Indian when they were from the Indian subcontinent), a manual chart audit of social histories and use of foreign language interpreters was completed for all patients with subsequent removal of non-Indigenous patients. The matched cohort was generated to include a goal 2:1 match of female sex within 5 years of age to those in the Indigenous cohort, excluding those with any record indicating Indigenous, American Indian, Native American, First Nations, or Alaska Native race or ethnicity. To identify pregnancies, billing codes for third trimester cesarean and vaginal deliveries, inductions, singleton, twin, and triplet pregnancies, and tobacco use during pregnancy were included. Any billing code identified suggestive of pregnancy resulted in a manual chart audit of pregnancy events to extract data regarding smoking behaviors. First and second-trimester losses were not included in this study. Patients with billing codes indicating pregnancy without associated clinical documentation, orders, or other medical records to review were excluded.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was to compare smoking prevalence between Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnancies. Secondary outcomes included uptake of smoking cessation interventions and effectiveness at promoting smoking cessation before fetal delivery.

Smoking Status

Smoking status was sorted into one of three categories upon manual review of the patient chart: never smoker, current smoker, and former smoker. Patients were considered “never smokers” if documentation available for review indicated no prior tobacco use on all available methods of data entry, including flowsheet entry from nursing or intake staff, patient self-report, orders and diagnosis codes, and provider documentation. Patients were considered “current smokers” if any of the data input methods indicated any amount of smoked tobacco use. For a patient to be considered a former smoker, 30 days or more of sustained cessation between data entry points indicating cessation was required. Changes in smoking status during pregnancy were recorded upon chart review. Smoking status was reviewed for each recorded clinical encounter indicating pregnancy. Encounters reviewed included all available during pregnancy, including those conducted by nursing staff, nurse midwives, non-physician independent practitioners, physicians, or psychologists. Those who used commercial combustible tobacco products including cigarettes and cigars at any point in their pregnancy were considered current smokers for this study. Clinical encounters documenting preconception counseling were recorded in the year prior to pregnancy. The use of electronic cigarettes, chewed tobacco, or traditional Indigenous ceremonial tobacco was not evaluated in this study.

Cessation Interventions

For all current smokers in both cohorts, orders, documentation, and flowsheets were reviewed to identify smoking cessation interventions offered during pregnancy. Referrals to mental health practitioners, inpatient cessation programs, outpatient cessation programs, Quitline use, or other smoking cessation resources were included as behavioral cessation interventions. Orders, documentation, flowsheets, prescription data, and self-reported medication history were reviewed for prescription or over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Prescriptions targeted for review included bupropion, varenicline, and any NRT product (patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler, nasal spray, or other formulation). If smoking cessation interventions were offered but declined by the patient, these patients were included in the determination of cessation aid uptake. If there was no documentation of refusal or discussion of smoking cessation, these patients were excluded from the estimation of smoking cessation aid uptake. Use of phone Quitlines or other publicly available resources were not available for review. Cessation was defined as patient-reported smoking cessation, provider documentation, or change in visit flowsheet status indicated by patient or practitioner entered data. Demographic information reviewed included age, ethnicity, address, and education data.

Social Determinants of Health

By collecting demographic data including address, we calculated the HOUSES index as a measure of socioeconomic status in our study. With property data including the number of bathrooms, the number of bedrooms, square footage, and building value, the HOUSES index can be derived as a surrogate for socioeconomic status.16,18,19 Prior health outcomes studied utilizing the HOUSES index include behavioral health outcomes, smoking, organ transplant outcomes, and all-cause mortality.19–23Z-scores were calculated for individuals based on property features and aggregated to a HOUSES overall Z-score. The Z-score was converted to a HOUSES index in quartiles, with the lowest quartile (quartile 1) representing the lowest surrogate of socioeconomic status, and the highest quartile (quartile 4) representing the greatest socioeconomic status in the cohort. The HOUSES index for individuals in this study was calculated in the first year of available smoking data. The lowest quartile of socioeconomic status (quartile 1) was compared to the summation of the highest quartiles of socioeconomic status (quartiles 2-4).

Statistical Analysis

Smoking prevalence during pregnancy was analyzed with a modified Poisson regression comparing the proportion of current smokers between the Indigenous cohort and the matched cohort. Prevalence was adjusted for HOUSES index, calendar year, maternal age during pregnancy, and multiple pregnancy events. Cessation and uptake of cessation interventions (including behavioral and pharmaceutical interventions) comparing the Indigenous cohort to the matched non-Indigenous cohort were evaluated using generalized estimating equations adjusted for age during pregnancy, HOUSES index, and calendar year with random effects for multiple pregnancies. Age and time were assessed for non-linearity using generalized additive models with splines given parametric methods and small sample sizes. Due to the small number of patients with available HOUSES data, a sensitivity analysis was conducted evaluating smoking prevalence, uptake of cessation interventions and cessation during pregnancy including all eligible patients with available HOUSES data. All data were analyzed for this study with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) or R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The significance level for all p-values was ≤ .05.

Results

Demographics

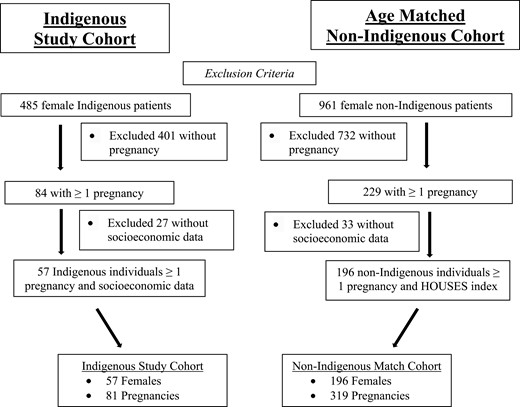

The Indigenous cohort included 485 female Indigenous patients after language and social history audit. A total of 84 female sex people in the Indigenous cohort experienced at least one pregnancy from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2019. Of the 84 people, 57 had a HOUSES index available for estimation of socioeconomic status and smoking data available for review with a total of 81 pregnancies. A total of 961 age-matched non-Indigenous patients were identified for the matched cohort. A total of 229 non-Indigenous people were pregnant during the study. Of the 229 women, 196 had HOUSES and smoking data available with a total of 319 pregnancies. Figure 1 is a flow chart displaying how Indigenous and non-Indigenous cohort participants were selected for inclusion in the study. Demographics of each pregnancy collected included maternal age at the time of delivery, race, and HOUSES index quartile. Missing education data limited the ability to adjust cohorts for the highest level of education achieved and therefore was not completed. The average age at the time of delivery for the cumulative pregnancies in the Indigenous cohort (n = 81) was 26.1 years, and the non-Indigenous matched cohort (n = 319) was 29.3 years. Age at time of delivery, race, and HOUSES index quartiles for all pregnancies in both cohorts are outlined in Table 1. The age at the time of delivery demographics of all pregnancies including individuals without HOUSES data available for socioeconomic adjustment was 26.9 years and 29.9 years for the Indigenous and non-Indigenous cohorts, respectively. The mean number of pregnancies experienced between the two cohorts was 1.4 pregnancies in the Indigenous cohort versus 1.6 pregnancies in the non-Indigenous cohort (p = .22).

Cohort sizes and demographics of indigenous cohort and the non-indigenous matched cohort

| Demographics . | Indigenous cohort . | Non-indigenous cohort . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with ≥1 pregnancy | 57 | 196 | |

| Total number of pregnancies | 81 | 319 | |

| Average maternal age at delivery, all pregnancies (years) | 26.1 | 29.3 | < .001 |

| HOUSES quartile 1, n (%)* | 23(40.4) | 69 (35.2) | .3623** |

| HOUSES quartile 2 | 19 (33.3) | 55 (28.1) | |

| HOUSES quartile 3 | 7 (12.3) | 45 (23.0) | |

| HOUSES quartile 4 | 8 (14.0) | 27 (13.8) | |

| Race and ethnicity demographics*** | |||

| White | 0 | 177 | |

| Black | 0 | 23 | |

| Asian | 0 | 14 | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 57 | 0 | |

| Other/mixed | 0 | 7 | |

| Refusal | 0 | 1 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 4 | |

| Demographics . | Indigenous cohort . | Non-indigenous cohort . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with ≥1 pregnancy | 57 | 196 | |

| Total number of pregnancies | 81 | 319 | |

| Average maternal age at delivery, all pregnancies (years) | 26.1 | 29.3 | < .001 |

| HOUSES quartile 1, n (%)* | 23(40.4) | 69 (35.2) | .3623** |

| HOUSES quartile 2 | 19 (33.3) | 55 (28.1) | |

| HOUSES quartile 3 | 7 (12.3) | 45 (23.0) | |

| HOUSES quartile 4 | 8 (14.0) | 27 (13.8) | |

| Race and ethnicity demographics*** | |||

| White | 0 | 177 | |

| Black | 0 | 23 | |

| Asian | 0 | 14 | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 57 | 0 | |

| Other/mixed | 0 | 7 | |

| Refusal | 0 | 1 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 4 | |

*HOUSES index as surrogate of socioeconomic status. Quartile 1 represents the lowest quartile of socioeconomic distribution, with quartiles 2, 3, and 4 representing progressively higher socioeconomic status.

**Comparing HOUSES index aggregates, Quartile 1 compared to combined quartiles 2,3, and 4.

***Multiple ethnicities are noted for some participants in the non-indigenous matched cohort.

Cohort sizes and demographics of indigenous cohort and the non-indigenous matched cohort

| Demographics . | Indigenous cohort . | Non-indigenous cohort . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with ≥1 pregnancy | 57 | 196 | |

| Total number of pregnancies | 81 | 319 | |

| Average maternal age at delivery, all pregnancies (years) | 26.1 | 29.3 | < .001 |

| HOUSES quartile 1, n (%)* | 23(40.4) | 69 (35.2) | .3623** |

| HOUSES quartile 2 | 19 (33.3) | 55 (28.1) | |

| HOUSES quartile 3 | 7 (12.3) | 45 (23.0) | |

| HOUSES quartile 4 | 8 (14.0) | 27 (13.8) | |

| Race and ethnicity demographics*** | |||

| White | 0 | 177 | |

| Black | 0 | 23 | |

| Asian | 0 | 14 | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 57 | 0 | |

| Other/mixed | 0 | 7 | |

| Refusal | 0 | 1 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 4 | |

| Demographics . | Indigenous cohort . | Non-indigenous cohort . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with ≥1 pregnancy | 57 | 196 | |

| Total number of pregnancies | 81 | 319 | |

| Average maternal age at delivery, all pregnancies (years) | 26.1 | 29.3 | < .001 |

| HOUSES quartile 1, n (%)* | 23(40.4) | 69 (35.2) | .3623** |

| HOUSES quartile 2 | 19 (33.3) | 55 (28.1) | |

| HOUSES quartile 3 | 7 (12.3) | 45 (23.0) | |

| HOUSES quartile 4 | 8 (14.0) | 27 (13.8) | |

| Race and ethnicity demographics*** | |||

| White | 0 | 177 | |

| Black | 0 | 23 | |

| Asian | 0 | 14 | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 57 | 0 | |

| Other/mixed | 0 | 7 | |

| Refusal | 0 | 1 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 4 | |

*HOUSES index as surrogate of socioeconomic status. Quartile 1 represents the lowest quartile of socioeconomic distribution, with quartiles 2, 3, and 4 representing progressively higher socioeconomic status.

**Comparing HOUSES index aggregates, Quartile 1 compared to combined quartiles 2,3, and 4.

***Multiple ethnicities are noted for some participants in the non-indigenous matched cohort.

Flow chart for inclusion criteria for Indigenous females and matched regional cohort who were pregnant from 2006 to 2019 in Olmsted County, Minnesota.

Smoking Prevalence During Pregnancy

Cigarette smoking was identified in 37 of the 81 pregnancies in the Indigenous cohort (45.7%) compared to 34 of the 319 pregnancies in the non-Indigenous cohort (10.7%). The relative risk of smoking during pregnancy was three-fold higher in Indigenous pregnant people than in the matched non-Indigenous cohort (RR: 3.25, 95% CI = 1.98–5.31, p < .01). Among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnancies increasing age during pregnancy decreased the risk of smoking during pregnancy (RR: 0.92, 95% CI = 0.88–0.96, p < .01). In both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous cohorts, those identified with a calculated HOUSES Index ≥2 were significantly less likely to smoke during pregnancy compared to those in quartile 1, the lowest marker of socioeconomic status (Indigenous cohort; RR: 0.59, 95% CI = 0.37–0.92, p = .02). There was no significant interaction between Indigenous race and age (p = .50), or Indigenous status and socioeconomic status (p = .52) compared to the non-Indigenous cohort. No significant deviations from linearity were found. Calendar year was not significantly associated with smoking during pregnancy, demonstrating no change over time. These findings are summarized in Table 2. Due to small sample size, a secondary analysis including individuals without HOUSES data available was conducted. Findings from a sensitivity analysis including all patients were consistent with HOUSES adjusted results reported for the cohort adjusted for HOUSES index. Smoking prevalence of all Indigenous pregnancies (n = 84 women with 111 pregnancies) revealed smoked tobacco use in 42/111 pregnancies, compared to the non-Indigenous cohort (n = 229 individuals with 358 pregnancies) with tobacco used during 40/358 pregnancies (RR: 2.47, 95% CI = 1.54–3.96, p < .01). These findings are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Prevalence of cigarette smoking during pregnancy comparing and indigenous and non-indigenous cohorts

| . | Indigenous study cohort . | Non-indigenous cohort . | Relative risk . | Confidence interval . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people | 57 | 196 | – | – | – |

| Number of pregnancies | 81 | 319 | – | – | – |

| Smoked during pregnancy n (%) | 37/81 (45.7) | 34/319 (10.7) | 3.25 | 1.98–5.31 | < .0001 |

| . | Indigenous study cohort . | Non-indigenous cohort . | Relative risk . | Confidence interval . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people | 57 | 196 | – | – | – |

| Number of pregnancies | 81 | 319 | – | – | – |

| Smoked during pregnancy n (%) | 37/81 (45.7) | 34/319 (10.7) | 3.25 | 1.98–5.31 | < .0001 |

Prevalence of cigarette smoking during pregnancy comparing and indigenous and non-indigenous cohorts

| . | Indigenous study cohort . | Non-indigenous cohort . | Relative risk . | Confidence interval . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people | 57 | 196 | – | – | – |

| Number of pregnancies | 81 | 319 | – | – | – |

| Smoked during pregnancy n (%) | 37/81 (45.7) | 34/319 (10.7) | 3.25 | 1.98–5.31 | < .0001 |

| . | Indigenous study cohort . | Non-indigenous cohort . | Relative risk . | Confidence interval . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people | 57 | 196 | – | – | – |

| Number of pregnancies | 81 | 319 | – | – | – |

| Smoked during pregnancy n (%) | 37/81 (45.7) | 34/319 (10.7) | 3.25 | 1.98–5.31 | < .0001 |

Uptake of Smoking Cessation Interventions During Pregnancy

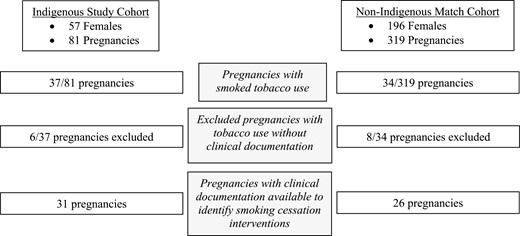

There was no difference in uptake of smoking cessation interventions between the Indigenous cohort and the non-Indigenous matched cohort (OR: 0.72, 95% CI = 0.22–2.7, p = .69). Of the 37 Indigenous pregnancies with smoked tobacco use, 31 pregnancies had longitudinal data to determine if cessation interventions were offered, including documentation, prescription data, and billing codes. Six pregnancies only had flowsheet data or ultrasound visit data without associated documentation to review for cessation intervention uptake. Of the 34 non-Indigenous pregnancies with smoked tobacco use, 8 pregnancies were excluded from intervention analysis as they were isolated encounters for ultrasounds without associated documentation to review for cessation intervention uptake, leaving 26 pregnancies in which cessation intervention uptake could be assessed. A flow chart demonstrating the proportion of included pregnancies can be found in Figure 2. In Indigenous pregnancies with current tobacco use, 11 of the Indigenous pregnant people completed behavioral counseling, and two used NRT. A total of 18 Indigenous pregnancies had no documented cessation intervention. A total of 10 non-Indigenous pregnant people completed behavioral counseling, two completed counseling with concurrent NRT use, two completed behavioral counseling with concurrent bupropion therapy, and one used bupropion only. A total of 11 non-Indigenous pregnancies had no documented intervention. These findings are outlined in Table 3.

Uptake and effectiveness of cessation interventions among smokers in indigenous pregnancies compared non-indigenous pregnancies

| Uptake by smoking cessation intervention . | Indigenous pregnancies . | Non-indigenous pregnancies . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uptake of smoking cessation interventions | |||

| Total number of pregnancies with smoked tobacco use and documentation for review | 31 | 26 | – |

| Counseling, n (%) | 11 (35.5) | 10 (38.5) | – |

| NRT | 2 (6.5) | 0 | – |

| Bupropion | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | – |

| Counseling and NRT | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | – |

| Counseling and bupropion | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | – |

| Uptake, any intervention | 13 (41.9) | 15 (57.7) | 0.69 |

| Smokers with no documented intervention | 18 (58.1) | 11 (42.3) | – |

| Smoking cessation at delivery . | Indigenous pregnancies . | Non-indigenous pregnancies . | p value . |

| Effectiveness of smoking of cessation interventions | |||

| n offered cessation aid | 13 | 15 | – |

| Cessation at fetal delivery* | |||

| Counseling n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (36.4) | – |

| NRT | 1 (50) | – | – |

| Bupropion | – | 1 (100) | – |

| Counseling and NRT | – | 0 (0) | – |

| Counseling and bupropion | – | 0 (0) | – |

| Cessation, any intervention | 1 (7.7) | 5 (33.3) | .012 |

| Cessation, no documented intervention | 3 (16.7) | 6 (54.5) | – |

| Uptake by smoking cessation intervention . | Indigenous pregnancies . | Non-indigenous pregnancies . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uptake of smoking cessation interventions | |||

| Total number of pregnancies with smoked tobacco use and documentation for review | 31 | 26 | – |

| Counseling, n (%) | 11 (35.5) | 10 (38.5) | – |

| NRT | 2 (6.5) | 0 | – |

| Bupropion | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | – |

| Counseling and NRT | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | – |

| Counseling and bupropion | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | – |

| Uptake, any intervention | 13 (41.9) | 15 (57.7) | 0.69 |

| Smokers with no documented intervention | 18 (58.1) | 11 (42.3) | – |

| Smoking cessation at delivery . | Indigenous pregnancies . | Non-indigenous pregnancies . | p value . |

| Effectiveness of smoking of cessation interventions | |||

| n offered cessation aid | 13 | 15 | – |

| Cessation at fetal delivery* | |||

| Counseling n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (36.4) | – |

| NRT | 1 (50) | – | – |

| Bupropion | – | 1 (100) | – |

| Counseling and NRT | – | 0 (0) | – |

| Counseling and bupropion | – | 0 (0) | – |

| Cessation, any intervention | 1 (7.7) | 5 (33.3) | .012 |

| Cessation, no documented intervention | 3 (16.7) | 6 (54.5) | – |

Abbreviation: NRT = nicotine replacement therapy.

*Proportion of women offered specific cessation aid, see Uptake of Cessation Interventions table.

Uptake and effectiveness of cessation interventions among smokers in indigenous pregnancies compared non-indigenous pregnancies

| Uptake by smoking cessation intervention . | Indigenous pregnancies . | Non-indigenous pregnancies . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uptake of smoking cessation interventions | |||

| Total number of pregnancies with smoked tobacco use and documentation for review | 31 | 26 | – |

| Counseling, n (%) | 11 (35.5) | 10 (38.5) | – |

| NRT | 2 (6.5) | 0 | – |

| Bupropion | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | – |

| Counseling and NRT | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | – |

| Counseling and bupropion | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | – |

| Uptake, any intervention | 13 (41.9) | 15 (57.7) | 0.69 |

| Smokers with no documented intervention | 18 (58.1) | 11 (42.3) | – |

| Smoking cessation at delivery . | Indigenous pregnancies . | Non-indigenous pregnancies . | p value . |

| Effectiveness of smoking of cessation interventions | |||

| n offered cessation aid | 13 | 15 | – |

| Cessation at fetal delivery* | |||

| Counseling n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (36.4) | – |

| NRT | 1 (50) | – | – |

| Bupropion | – | 1 (100) | – |

| Counseling and NRT | – | 0 (0) | – |

| Counseling and bupropion | – | 0 (0) | – |

| Cessation, any intervention | 1 (7.7) | 5 (33.3) | .012 |

| Cessation, no documented intervention | 3 (16.7) | 6 (54.5) | – |

| Uptake by smoking cessation intervention . | Indigenous pregnancies . | Non-indigenous pregnancies . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uptake of smoking cessation interventions | |||

| Total number of pregnancies with smoked tobacco use and documentation for review | 31 | 26 | – |

| Counseling, n (%) | 11 (35.5) | 10 (38.5) | – |

| NRT | 2 (6.5) | 0 | – |

| Bupropion | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | – |

| Counseling and NRT | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | – |

| Counseling and bupropion | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | – |

| Uptake, any intervention | 13 (41.9) | 15 (57.7) | 0.69 |

| Smokers with no documented intervention | 18 (58.1) | 11 (42.3) | – |

| Smoking cessation at delivery . | Indigenous pregnancies . | Non-indigenous pregnancies . | p value . |

| Effectiveness of smoking of cessation interventions | |||

| n offered cessation aid | 13 | 15 | – |

| Cessation at fetal delivery* | |||

| Counseling n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (36.4) | – |

| NRT | 1 (50) | – | – |

| Bupropion | – | 1 (100) | – |

| Counseling and NRT | – | 0 (0) | – |

| Counseling and bupropion | – | 0 (0) | – |

| Cessation, any intervention | 1 (7.7) | 5 (33.3) | .012 |

| Cessation, no documented intervention | 3 (16.7) | 6 (54.5) | – |

Abbreviation: NRT = nicotine replacement therapy.

*Proportion of women offered specific cessation aid, see Uptake of Cessation Interventions table.

Flowsheet demonstrating proportion of patients in indigenous and non-indigenous cohorts with smoked tobacco use during pregnancy, uptake of pharmaceutical cessation aids, and effectiveness of smoking cessation aids.

Smoking Cessation During Pregnancy

Pregnant Indigenous people were less likely to quit smoking during pregnancy than non-Indigenous people (OR: 0.23, 95% CI = 0.07–0.72, p = .012). Of the 13 Indigenous people undergoing smoking cessation counseling and/or bupropion interventions, zero quit smoking during pregnancy. One of the two Indigenous pregnancies treated with NRT achieved cessation during pregnancy. Of the 15 non-Indigenous pregnant smokers, five achieved cessation, four with counseling monotherapy, and one with bupropion monotherapy. These findings are demonstrated in Table 3. Age, calendar year, and socioeconomic status were not associated with smoking cessation among pregnant people. Preconception counseling was unable to be reliably extrapolated from chart review in the year prior to conception, thus was not included in analysis.

Discussion

Indigenous people in Olmsted County, Minnesota were more than three times more likely to smoke cigarettes during pregnancy compared to non-Indigenous people. The greater than three-fold increase in smoking prevalence identified in Indigenous pregnancies was associated with significantly lower cessation rates during pregnancy. Although the uptake of validated smoking cessation interventions between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnancies was equivocal, none of the Indigenous pregnancies treated with non-pharmacologic counseling interventions achieved smoking cessation, compared to a 36.4% cessation rate of non-Indigenous pregnancies offered cessation counseling. Of note, the uptake of smoking cessation interventions was lower than expected in Olmsted County in both cohorts compared to the estimated uptake of cessation counseling on a national scale.1,6 Younger individuals and those falling in the lowest quartile of socioeconomic status were more likely to smoke. This trend was noted in Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnancies. The findings of this study suggest there is a disparity in the effectiveness of standardized smoking cessation interventions in Indigenous pregnancies. This disparity in cessation efficacy may contribute to Indigenous maternal mortality in the state of Minnesota, which is over eight times higher than that of White pregnant people.24

We have previously described smoking prevalence in Olmsted County Indigenous people compared to an age and sex-matched cohort. Smoking prevalence in the non-Indigenous cohort (n = 1780) was noted to be between 26% and 30% from 2006 to 2019, compared to 39–47% smoking prevalence in the Indigenous cohort (n = 898) without changes in prevalence noted over time.25 The rate of smoking in Indigenous pregnancies was similar to the smoking prevalence of the cumulative cohort, indicating there may be other disparities in healthcare delivery not captured by this study, such as lack of preconception counseling or unplanned pregnancy. Disparities in the availability of preconception counseling have been described in patients of low socioeconomic opportunity, and racial and ethnic minorities.26,27 Unplanned pregnancy is known to be associated with measures of lower socioeconomic status. In our cohort, 40% of the Indigenous cohort was represented by the lowest socioeconomic quartile versus 35% in the non-Indigenous cohort. Further, the Indigenous cohort was younger at the time of delivery for all pregnancies analyzed.28

Another theory exploring contributions to peri-natal smoking includes the possible influence of psychosocial stress or mood disorders.1,6 In the general population, mood disorders and psychosocial stress have been described as influential factors contributing to smoking during pregnancy.26,29 A recent study published by Patten and colleagues published in 2020 examining stress and depression in pregnant Alaska Native people revealed smoking and use of chewed tobacco products was associated with less stress and lower rates of depression.30 These findings oppose those found in pregnancies in the general population.6,26,31 This study demonstrates the importance of studying the specific factors leading to healthcare disparities, as findings demonstrated in the general population may not apply to diverse populations.14

Our study demonstrates no disparity in the uptake of smoking cessation interventions, but a disparity in the effectiveness of the interventions. When examining the uptake of pharmaceutical cessation aids in all Indigenous people residing in Olmsted County from 2006 to 2019 bupropion and NRT uptake were higher in the Indigenous cohort compared to the non-Indigenous cohort (35.8% vs. 16.3%, p < .001).32 Prior studies suggest standard interventions may not be effective in Indigenous pregnancies due to a variety of factors including lack of acknowledgment of the cultural significance of tobacco as a medicine, delivery by non-Indigenous physicians and providers, and social normalization of tobacco use in Indigenous communities.33 Unfortunately, attempts to address smoking prevalence during pregnancy in Indigenous communities through culturally tailored interventions and biofeedback methods have not resulted in significant smoking cessation or reduced smoking or smokeless tobacco use prevalence.8,34 Further study to understand the background and cause of the ineffectiveness of current interventions is critical to ultimately address this disparity.

Strengths of this study include the longitudinal review of data from 2006 to 2019 compared to a matched regional cohort. Understanding longitudinal regional smoking behaviors allows a holistic view of this population and demonstrates no disparity in uptake, but a disparity in intervention effectiveness. Further, this study allowed the inclusion of mixed-race Indigenous people, who have historically been excluded from studies of Indigenous people. Examining socioeconomic factors influencing smoking behaviors is another strength of this study, demonstrating similar smoking behaviors considering socioeconomic demographics between Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnancies. Although this study does not capture Indian Health Services (IHSs) data, the Olmsted County Indigenous population represents a group of people residing in an area without IHS access as there are no clinics in the county. Of the estimated 5.1 million Indigenous North Americans, IHS serves approximately 2.6 million individuals.35

Limitations include small sample sizes limiting comparison of those within the lowest quartile of socioeconomic demographics between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous cohorts. Additionally, some individuals were not able to be included with adjustment for socioeconomic status due to missing housing data and unsuccessful attempts to geocode limiting the abstraction of the HOUSES index. Although the age, parity, and smoking demographics of excluded individuals were similar to the study cohort, there may be unmeasured social determinants of health influencing the reason for exclusion (ie unstable housing or frequent address change). This study did not have any direct patient contact and did not include data examining the uptake of smoking cessation Quitlines or online cessation tools. Given lack of contact with participants, we were not reliably able to determine which patients were given preconception counseling. We were additionally unable to determine the factors influencing cessation in individuals who were not offered any cessation intervention. This study was specifically designed to examine the use of smoked commercial tobacco products, and therefore does not capture the use of smokeless tobacco or electronic cigarettes, as this information could not be reliably extracted from the electronic medical record. An additional limitation of this study is the exploration of missed healthcare appointments between cohorts or other barriers to attending prenatal appointments. Olmsted County does not include any IHS service units, therefore a comparison of cessation interventions and outcomes among users of IHS for prenatal care was not available for review.

In summary, Indigenous pregnant people are more than three times more likely to smoke commercial tobacco products during pregnancy compared to a matched non-Indigenous regional cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Although there was no difference in patterns of uptake of cessation interventions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnancies, Indigenous people were significantly less likely to quit smoking during pregnancy compared to the matched non-Indigenous cohort with standard of care interventions. Further study is needed to understand why standard of care cessation interventions were ineffective at promoting cessation during pregnancy in this population.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://dbpia.nl.go.kr/ntr.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge generous support from funding sources. The authors had full access to all of the data in this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We confirm this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal. All authors have approved this manuscript and agree with the submission. The authors recognize the importance of data sovereignty and representation of Indigenous people in the conduct of clinical research. Ann Rusk, M.D. is an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Nation. Christi A. Patten, is an expert in the conduct of equitable Indigenous health research through her work with Alaska Native communities. The remaining authors identify as allies in clinical research and representation. This study was conducted with consultation from the Mayo Clinic Center for Health Equity and Community Engagement Research with the department of Native American Research Outreach.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Healthcare Delivery and the Rochester Epidemiology Project Scholarship. This study used the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA; AG 058738), by the Mayo Clinic Research Committee, and by fees paid annually by REP users. This study used the resources of the HOUSES Program which is supported by the National Institute on Aging (AG 65639-02). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Mayo Clinic, or the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of the Healthcare Delivery.

Declaration of Interests

AMR and CCD disclose funding from the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. Rusk also discloses funding from the Rochester Epidemiology Project Scholarship. AMC, BAA, CCK, CAP, and CW, disclose funding from the National Institutes of Health. Kennedy and Wi disclose funding from Mayo Funds. Kennedy also discloses funding from the Department of Defense. Wi also discloses funding from GlaxsoSmithKlein. YTB and JRF have no disclosures to report.

Contributions

AMR designed the study, designed data collection tools, wrote the analysis plan, cleaned and analyzed the data, and drafted and revised the paper. REG cleaned and analyzed the data and revised the paper. AMC analyzed the data and revised the paper. CAP analyzed the data and revised the paper. YTB cleaned and analyzed the data and revised the paper. CCD analyzed the data and revised the paper. CW analyzed and cleaned data and revised the paper. JRF cleaned data and revised the paper. BAA cleaned data and revised the paper. CCK designed the study, designed data collection tools, analyzed the data, and revised the paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article were accessed from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Because of the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study, requests to access the dataset from qualified researchers trained in human subject confidentiality protocols may be sent to the Rochester Epidemiology Project at Mayo Clinic at [email protected].

Comments