-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sarah D Kowitt, Jennifer Mendel Sheldon, Rhyan N Vereen, Rachel T Kurtzman, Nisha C Gottfredson, Marissa G Hall, Noel T Brewer, Seth M Noar, The Impact of The Real Cost Vaping and Smoking Ads across Tobacco Products, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 25, Issue 3, March 2023, Pages 430–437, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntac206

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Little research has examined the spillover effects of tobacco communication campaigns, such as how anti-smoking ads affect vaping.

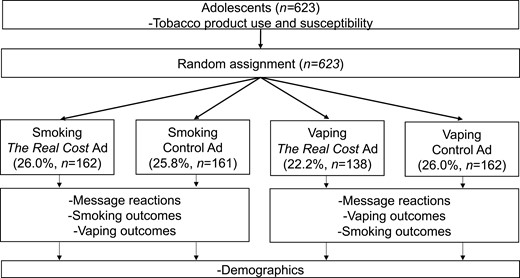

Participants were a national sample of 623 U.S. adolescents (ages 13–17 years) from a probability-based panel. In a between-subjects experiment, we randomly assigned adolescents to view one of four videos online: (1) a smoking prevention video ad from the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) The Real Cost campaign, (2) a neutral control video about smoking, (3) a vaping prevention video ad from The Real Cost campaign, or (4) a neutral control video about vaping. We present effect sizes as Cohen’s d, standardized mean differences, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Exposure to The Real Cost vaping prevention ads led to more negative attitudes toward vaping compared with control (d = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.53), while exposure to The Real Cost smoking prevention ads did not affect smoking-related outcomes compared with control (p-values > .05). Turning to spillover effects, exposure to The Real Cost smoking prevention ads led to less susceptibility to vaping (d = −0.34, 95% CI: −0.56, −0.12), more negative attitudes toward vaping (d = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.65) and higher perceived likelihood of harm from vaping (d = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.48), compared with control. Exposure to The Real Cost vaping prevention ads did not affect smoking-related outcomes compared with control (p-values > .05).

This experiment found evidence of beneficial spillover effects of smoking prevention ads on vaping outcomes and found no detrimental effects of vaping prevention ads on smoking outcomes.

Little research has examined the spillover effects of tobacco communication campaigns, such as how anti-smoking ads affect vaping. Using a national sample of 623 U.S. adolescents, we found beneficial evidence of spillover effects of smoking prevention ads on vaping outcomes, which is promising since it suggests that smoking prevention campaigns may have the additional benefit of reducing both smoking and vaping among adolescents. Additionally, we found that vaping prevention campaigns did not elicit unintended consequences on smoking-related outcomes, an important finding given concerns that vaping prevention campaigns could drive youth to increase or switch to using combustible cigarettes instead of vaping.

Introduction

Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable disease, disability, and death in the United States.1 Nearly all tobacco use begins during adolescence, making youth prevention an important priority for tobacco prevention and control efforts.2 Despite lower rates of combustible cigarette smoking in recent years, each day thousands of adolescents smoke their first cigarette, and many become daily tobacco users—contributing to over 5 million adolescents at risk of premature death.2,3 Increasing evidence of dual- and poly-use of tobacco products4—coupled with an epidemic of e-cigarette use among youth5—presents an imminent need for continued tobacco control efforts, including national communication campaigns.

Launched in 2014, the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) The Real Cost youth tobacco prevention campaign aims to educate at-risk teens about the harmful effects of tobacco use.6 Initially, the campaign focused exclusively on cigarette smoking. Evaluations of The Real Cost suggest that it has reached almost 90% of adolescents,7 influenced risk beliefs about combustible tobacco,8 and prevented smoking initiation.9,10 Specifically, the campaign has prevented an estimated 380 000–587 000 youths ages 11–19 years from initiating smoking nationwide.9 In September 2018, The Real Cost campaign expanded to include messages about e-cigarettes.11 Research suggests that exposure to e-cigarette prevention ads used in The Real Cost campaign is associated with higher perceived message effectiveness, more negative views of vaping, and lower intentions to vape compared to control videos.12,13

However, it is unclear whether The Real Cost campaign messages about one tobacco product may affect beliefs about other nontargeted tobacco products. To conceptualize such spillover effects, we turn to theories of spreading activation14 and attitude accessibility.15 These theories posit that we have imprecise and overlapping mental representations of concepts, store semantically similar concepts in memory together, and form associations between objects (campaign messages) and attitudes (toward tobacco use). Cigarettes and e-cigarettes are both tobacco products that contain nicotine. In addition, connections between vaping and smoking may be strengthened by shared physical similarities (e.g. vapes can look like cigarettes and produce vapor akin to smoke) and advertisements that have tied vaping and smoking together by implying the benefits of quitting smoking16 or showing comparisons in nicotine levels.17 One implication of this is that people’s attitudes and beliefs about different tobacco products are likely to be connected.18 For example, a vaping prevention video may influence adolescents’ attitudes toward smoking.

There are three different types of spillover effects that are possible. First, campaigns may have beneficial spillover effects, which could mean that the impact of campaigns may be greater than previously thought, since evaluations typically only examine targeted products. For instance, one study found that e-cigarette warnings reduced interest in smoking cigarettes compared with control warnings.19 Second, campaigns may have detrimental spillover effects (e.g. vaping prevention ads increasing interest in cigarettes), which could mean that campaigns may not have as much impact on overall tobacco use. That is, if messages increase harmful perceptions toward the targeted tobacco product, that could lead tobacco users to instead consume a tobacco product that is not the target of the messages.20–22 For example, exposure to cigarette pictorial warnings increased intentions to quit smoking but also increased intentions to use hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus, in an online experiment.23 Importantly, this would be particularly detrimental if users moved from less harmful to more harmful tobacco products, such as moving from e-cigarettes to cigarettes. Finally, it is possible to have no spillover effects, which would be the case if campaigns affected only the targeted tobacco product but had no impact on nontargeted products.

To advance the literature on tobacco prevention communication campaigns, we conducted an experimental evaluation of The Real Cost cigarette and e-cigarette prevention ads among adolescents, examining the impact of The Real Cost ads on message reactions and psychosocial outcomes, including susceptibility, negative attitudes, and perceived likelihood of harm. Since The Real Cost campaign was designed to change beliefs and attitudes about particular tobacco products,6 we sought to examine the impact of vaping and cigarette prevention ads on targeted outcomes (e.g. the influence of vaping ads on vaping attitudes). To examine the possibility that The Real Cost ads might affect beliefs and attitudes about nontargeted tobacco products (i.e. spillover effects), we also examined the impact of vaping and cigarette prevention ads on nontargeted outcomes (e.g. the influence of vaping ads on smoking attitudes).

Methods

Participants

Participants were a national probability sample of U.S. adolescents (ages 13–17 years) recruited in the Fall of 2020 from the AmeriSpeak panel, a probability-based panel maintained by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago. NORC randomly selected U.S. households using area probability and address-based sampling, with a known, nonzero probability of selection from the NORC National Sample Frame. For the current study, adolescents were drawn from AmeriSpeak panel households. To address panel attrition because of the COVID-19 pandemic, NORC also invited adolescents ages 13–17 years living in AmeriSpeak panel households who had not yet joined the teen panel to take part in the study. In total, 1351 households had age-eligible children and received information about the study. Parents from 1002 households (74% of those eligible) provided informed consent, and 624 adolescents assented and completed the survey (62% of households whose parents consented; 46% of all eligible households). One participant had extensive missing data and was excluded from analyses, resulting in an analytic sample of 623 adolescents.

Procedures

We conducted an online between-subjects messaging experiment with four conditions. We randomized adolescents to (1) a smoking prevention video ad from The Real Cost campaign, (2) a neutral control video about smoking, (3) a vaping prevention video ad from The Real Cost campaign, or (4) a neutral control video about vaping (Figure 1). The ads were 30 seconds long. Adolescents randomized to view The Real Cost ad were further randomized to see one of six ads. Three of the six ads from The Real Cost were about health harms and three were about addiction (Supplementary Table A). Adolescents randomized to view the control ad viewed an informational video we developed with basic facts about vaping or smoking culled from Wikipedia and other sources. The information included product definitions and production methods and used parallel language for cigarettes and e-cigarettes. The control ads featured black text on a white screen with audio narration. To maximize ad exposure, we presented the ad two times. Participants received a $12 cash equivalent incentive through the NORC panel. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures.

Measures

The survey first assessed tobacco product use, then displayed ads per participants’ randomly assigned condition and then assessed message reactions. Next, participants assigned to see vaping ads (The Real Cost and control) answered questions on vaping outcomes and then smoking outcomes. For participants assigned to see smoking ads (The Real Cost and control), the smoking questions came first, followed by the vaping questions. Finally, the survey assessed demographics.

Message Reactions

The survey assessed several constructs from the Tobacco Warnings Model,24 including attention,25 negative affect,25,26 and cognitive elaboration,27–29 as well as avoidance,30,31 and reactance,32,33 with one item for each construct. The survey presented the stem, “How much does this ad . . .” and the following five prompts: (1) grab your attention (attention), (2) make you feel scared (negative affect), (3) make you think about reasons for not [vaping/ smoking cigarettes] (cognitive elaboration), (4) make you want to look away (avoidance), and (5) annoy you (reactance). The 5-point response scale ranged from “not at all” (coded as 1) to “a great deal” (5).

Susceptibility

The survey assessed susceptibility to vaping and smoking using three items: (1) “Do you think you might [use an e-cigarette or vape/ smoke a cigarette] soon?,” (2) “Do you think you will [use an e-cigarette or vape/ smoke a cigarette] in the next year?,” and (3) “If one of your best friends were to offer you [an e-cigarette or vape/ cigarette], would you [use/ smoke] it?”34 The 4-point response scale ranged from “definitely not” (coded as 1) to “definitely yes” (coded as 4). We averaged these three items together to create a susceptibility scale for vaping (α = 0.94) and smoking (α = 0.92).

Negative Attitudes

The survey assessed attitudes toward vaping and smoking using one item per product, adapted from prior work.35 The survey presented the stem “Do you think [vaping/ smoking] is . . .” and 5-point response scales that ranged from “very bad” (coded as 1) to “very good” (coded as 5). We reverse coded this item so that higher scores indicate more negative attitudes.

Perceived Likelihood of Harm

The survey assessed the perceived likelihood of harm using one item per product, adapted from prior work.36,37 The survey asked, “If you regularly [vaped/ smoked cigarettes], what is the chance that you would one day get [vaping-related/ smoking-related] health problems?” The 5-point response scale ranged from “no chance” (coded as 1) to “certain” (coded as 5).

Tobacco Product Use and Demographics

The survey assessed vaping status, cigarette smoking status, and current use of the other tobacco product prior to randomization to conditions. To assess vaping status, we classified youth into mutually exclusive categories as:

Current vapers. If youth reported ever trying vaping and reported vaping in the past 30 days, we classified them as current users.

At risk for vaping. If youth had vaped before, but not in the past 30 days, the survey assessed whether they thought they would vape in the future, on a 4-point scale ranging from definitely not (coded as 1) to definitely yes (coded as 4).38 If they answered anything other than “definitely not,” we classified them as at risk of vaping. If youth had never vaped before, the survey assessed whether they had ever been curious about vaping39 and if they thought they would vape in the future.38 If they answered anything other than “definitely not,” to both questions we classified them as at risk for vaping.

Not at risk for vaping. We classified all other adolescents as not at risk for vaping.

The survey included similar questions to assess cigarette smoking status. The survey also assessed current other tobacco product use by asking about past 30-day use of traditional cigars; cigarillos, filtered cigars, and little cigars; pipes filled with tobacco; hookah; and smokeless tobacco. Following the experiment, the survey assessed age, race and Hispanic ethnicity,40 genders, education level for the highest educated parent, household income, and tobacco product use in the home.

Data Analysis

To compare experimental conditions (The Real Cost vs. control) on demographic and tobacco use variables, we used independent sample t-tests and χ2 tests, which revealed no differences (Supplementary Table B). To compare experimental conditions on vaping and smoking outcomes, we then used independent sample t-tests and Cohen’s d effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).41 We did this first for targeted effects and then for spillover effects; means and p-values from the t-tests appear in the tables. As a sensitivity analysis, we also examined results for all outcomes excluding current smokers or current vapers, which yielded the same general pattern of findings (data not shown). We conducted the analyses in SAS (version 9.4) and used two-tailed tests and a critical alpha of 0.05.

Results

Participants' mean age was 15 years, and about half reported being female (53%) (Supplementary Table C). About two-thirds of the sample identified as white (65%), and 19% identified as Hispanic. In terms of tobacco use, 14% currently vaped while 47% were at risk for vaping and 8% currently smoked while 33% were at risk for smoking.

Smoking Prevention Ads

Exposure to The Real Cost smoking ads led to more attention (d = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.52), negative affect (d = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.65, 1.11), and cognitive elaboration (d = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.75, 1.22) than the smoking control ad (Table 1). The Real Cost smoking ads also led to more avoidance (d = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.79) than the smoking control ad, but not reactance (d = 0.11, 95% CI: −0.11. 0.33).

| Outcome . | Smoking control ad, M (SD) . | The Real Cost smoking ad, M (SD) . | p . | Cohen’s d (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Message reactions | ||||

| Attention a | 2.25 (1.31) | 3.83 (1.14) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.04, 1.52) |

| Negative affect a | 1.83 (1.19) | 2.99 (1.44) | <.001 | 0.88 (0.65, 1.11) |

| Cognitive elaboration a | 2.44 (1.44) | 3.75 (1.21) | <.001 | 0.98 (0.75, 1.22) |

| Avoidance a | 1.95 (1.25) | 2.73 (1.50) | <.001 | 0.56 (0.34, 0.79) |

| Reactance a | 2.22 (1.23) | 2.36 (1.23) | .32 | 0.11 (−0.11. 0.33) |

| Targeted outcomes: Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Susceptibility to smoking b | 1.41 (0.64) | 1.32 (0.56) | .20 | −0.14 (−0.36, 0.08) |

| Smoking attitudes c | 4.63 (0.70) | 4.75 (0.60) | .10 | 0.19 (−0.04, 0.41) |

| Smoking perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.87 (1.08) | 4.09 (0.95) | .06 | 0.21 (−0.01, 0.43) |

| Nontargeted outcomes: Vaping | ||||

| Susceptibility to vaping b | 1.69 (0.85) | 1.43 (0.69) | .003 | −0.34 (−0.56, −0.12) |

| Vaping attitudes c | 4.17 (0.91) | 4.53 (0.76) | <.001 | 0.43 (0.20, 0.65) |

| Vaping perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.45 (1.05) | 3.73 (1.07) | .02 | 0.26 (0.04, 0.48) |

| Outcome . | Smoking control ad, M (SD) . | The Real Cost smoking ad, M (SD) . | p . | Cohen’s d (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Message reactions | ||||

| Attention a | 2.25 (1.31) | 3.83 (1.14) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.04, 1.52) |

| Negative affect a | 1.83 (1.19) | 2.99 (1.44) | <.001 | 0.88 (0.65, 1.11) |

| Cognitive elaboration a | 2.44 (1.44) | 3.75 (1.21) | <.001 | 0.98 (0.75, 1.22) |

| Avoidance a | 1.95 (1.25) | 2.73 (1.50) | <.001 | 0.56 (0.34, 0.79) |

| Reactance a | 2.22 (1.23) | 2.36 (1.23) | .32 | 0.11 (−0.11. 0.33) |

| Targeted outcomes: Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Susceptibility to smoking b | 1.41 (0.64) | 1.32 (0.56) | .20 | −0.14 (−0.36, 0.08) |

| Smoking attitudes c | 4.63 (0.70) | 4.75 (0.60) | .10 | 0.19 (−0.04, 0.41) |

| Smoking perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.87 (1.08) | 4.09 (0.95) | .06 | 0.21 (−0.01, 0.43) |

| Nontargeted outcomes: Vaping | ||||

| Susceptibility to vaping b | 1.69 (0.85) | 1.43 (0.69) | .003 | −0.34 (−0.56, −0.12) |

| Vaping attitudes c | 4.17 (0.91) | 4.53 (0.76) | <.001 | 0.43 (0.20, 0.65) |

| Vaping perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.45 (1.05) | 3.73 (1.07) | .02 | 0.26 (0.04, 0.48) |

aHigher scores indicate greater message reactions.

bHigher scores indicate greater susceptibility.

cHigher scores indicate more negative attitudes.

dHigher scores indicate higher beliefs about harms.

| Outcome . | Smoking control ad, M (SD) . | The Real Cost smoking ad, M (SD) . | p . | Cohen’s d (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Message reactions | ||||

| Attention a | 2.25 (1.31) | 3.83 (1.14) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.04, 1.52) |

| Negative affect a | 1.83 (1.19) | 2.99 (1.44) | <.001 | 0.88 (0.65, 1.11) |

| Cognitive elaboration a | 2.44 (1.44) | 3.75 (1.21) | <.001 | 0.98 (0.75, 1.22) |

| Avoidance a | 1.95 (1.25) | 2.73 (1.50) | <.001 | 0.56 (0.34, 0.79) |

| Reactance a | 2.22 (1.23) | 2.36 (1.23) | .32 | 0.11 (−0.11. 0.33) |

| Targeted outcomes: Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Susceptibility to smoking b | 1.41 (0.64) | 1.32 (0.56) | .20 | −0.14 (−0.36, 0.08) |

| Smoking attitudes c | 4.63 (0.70) | 4.75 (0.60) | .10 | 0.19 (−0.04, 0.41) |

| Smoking perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.87 (1.08) | 4.09 (0.95) | .06 | 0.21 (−0.01, 0.43) |

| Nontargeted outcomes: Vaping | ||||

| Susceptibility to vaping b | 1.69 (0.85) | 1.43 (0.69) | .003 | −0.34 (−0.56, −0.12) |

| Vaping attitudes c | 4.17 (0.91) | 4.53 (0.76) | <.001 | 0.43 (0.20, 0.65) |

| Vaping perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.45 (1.05) | 3.73 (1.07) | .02 | 0.26 (0.04, 0.48) |

| Outcome . | Smoking control ad, M (SD) . | The Real Cost smoking ad, M (SD) . | p . | Cohen’s d (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Message reactions | ||||

| Attention a | 2.25 (1.31) | 3.83 (1.14) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.04, 1.52) |

| Negative affect a | 1.83 (1.19) | 2.99 (1.44) | <.001 | 0.88 (0.65, 1.11) |

| Cognitive elaboration a | 2.44 (1.44) | 3.75 (1.21) | <.001 | 0.98 (0.75, 1.22) |

| Avoidance a | 1.95 (1.25) | 2.73 (1.50) | <.001 | 0.56 (0.34, 0.79) |

| Reactance a | 2.22 (1.23) | 2.36 (1.23) | .32 | 0.11 (−0.11. 0.33) |

| Targeted outcomes: Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Susceptibility to smoking b | 1.41 (0.64) | 1.32 (0.56) | .20 | −0.14 (−0.36, 0.08) |

| Smoking attitudes c | 4.63 (0.70) | 4.75 (0.60) | .10 | 0.19 (−0.04, 0.41) |

| Smoking perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.87 (1.08) | 4.09 (0.95) | .06 | 0.21 (−0.01, 0.43) |

| Nontargeted outcomes: Vaping | ||||

| Susceptibility to vaping b | 1.69 (0.85) | 1.43 (0.69) | .003 | −0.34 (−0.56, −0.12) |

| Vaping attitudes c | 4.17 (0.91) | 4.53 (0.76) | <.001 | 0.43 (0.20, 0.65) |

| Vaping perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.45 (1.05) | 3.73 (1.07) | .02 | 0.26 (0.04, 0.48) |

aHigher scores indicate greater message reactions.

bHigher scores indicate greater susceptibility.

cHigher scores indicate more negative attitudes.

dHigher scores indicate higher beliefs about harms.

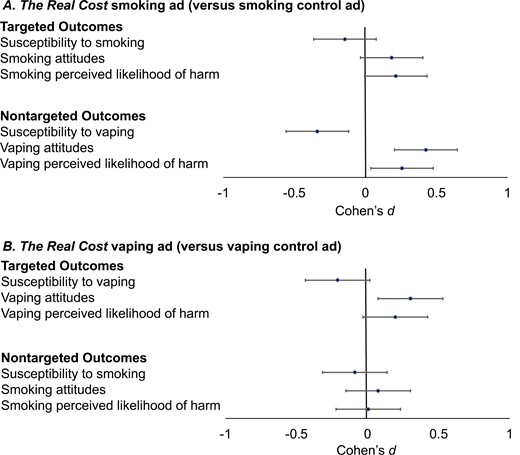

The Real Cost smoking ads did not affect susceptibility to smoking (d = −0.14, 95% CI: −0.36, 0.08), smoking attitudes (d = 0.19, 95% CI: −0.04, 0.41), or perceived likelihood of harm from smoking (d = 0.21, 95% CI: −0.01, 0.43) compared with the smoking control ad (Figure 2).

Impact of The Real Cost ads on vaping and smoking outcomes. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Exposure to The Real Cost smoking ads led to beneficial spillover effects on vaping outcomes with lower susceptibility to vaping than the smoking control ad (d = −0.34, 95% CI: −0.56, −0.12). In addition, participants exposed to The Real Cost smoking ads had more negative attitudes toward vaping (d = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.65) and a higher perceived likelihood of harm from vaping (d = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.48) compared with the smoking control ad.

Vaping Prevention Ads

Exposure to The Real Cost vaping ads led to more attention (d = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.69, 1.17), negative affect (d = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.54, 1.01), and cognitive elaboration (d = 0.81, 0.57, 1.04), but did not elicit more avoidance (d = 0.06, 95% CI: −0.17, 0.29) or reactance (d = −0.07, 95% CI: −0.30, 0.16) compared with the vaping control ad (Table 2).

| Outcome . | Vaping control ad, M (SD) . | The Real Cost vaping ad, M (SD) . | p . | Cohen’s d (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Message reactions | ||||

| Attention a | 2.39 (1.38) | 3.62 (1.25) | <.001 | 0.93 (0.69, 1.17) |

| Negative affect a | 1.98 (1.21) | 2.99 (1.40) | <.001 | 0.77 (0.54, 1.01) |

| Cognitive elaboration a | 2.72 (1.40) | 3.80 (1.28) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.57, 1.04) |

| Avoidance a | 2.23 (1.31) | 2.31 (1.45) | .60 | 0.06 (−0.17, 0.29) |

| Reactance a | 2.36 (1.29) | 2.27 (1.33) | .54 | −0.07 (−0.30, 0.16) |

| Targeted outcomes: Vaping | ||||

| Susceptibility to vaping b | 1.57 (0.71) | 1.43 (0.68) | .07 | −0.21 (−0.44, 0.02) |

| Vaping attitudes c | 4.33 (0.83) | 4.57 (0.69) | .009 | 0.30 (0.07, 0.53) |

| Vaping perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.54 (1.13) | 3.75 (1.09) | .09 | 0.20 (−0.03, 0.42) |

| Nontargeted outcomes: Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Susceptibility to smoking b | 1.32 (0.60) | 1.27 (0.59) | .44 | −0.09 (−0.32, 0.14) |

| Smoking attitudes c | 4.71 (0.72) | 4.76 (0.63) | .52 | 0.08 (−0.15, 0.30) |

| Smoking perceived likelihood of harm d | 4.12 (1.16) | 4.12 (1.12) | .96 | 0.01 (−0.22, 0.23) |

| Outcome . | Vaping control ad, M (SD) . | The Real Cost vaping ad, M (SD) . | p . | Cohen’s d (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Message reactions | ||||

| Attention a | 2.39 (1.38) | 3.62 (1.25) | <.001 | 0.93 (0.69, 1.17) |

| Negative affect a | 1.98 (1.21) | 2.99 (1.40) | <.001 | 0.77 (0.54, 1.01) |

| Cognitive elaboration a | 2.72 (1.40) | 3.80 (1.28) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.57, 1.04) |

| Avoidance a | 2.23 (1.31) | 2.31 (1.45) | .60 | 0.06 (−0.17, 0.29) |

| Reactance a | 2.36 (1.29) | 2.27 (1.33) | .54 | −0.07 (−0.30, 0.16) |

| Targeted outcomes: Vaping | ||||

| Susceptibility to vaping b | 1.57 (0.71) | 1.43 (0.68) | .07 | −0.21 (−0.44, 0.02) |

| Vaping attitudes c | 4.33 (0.83) | 4.57 (0.69) | .009 | 0.30 (0.07, 0.53) |

| Vaping perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.54 (1.13) | 3.75 (1.09) | .09 | 0.20 (−0.03, 0.42) |

| Nontargeted outcomes: Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Susceptibility to smoking b | 1.32 (0.60) | 1.27 (0.59) | .44 | −0.09 (−0.32, 0.14) |

| Smoking attitudes c | 4.71 (0.72) | 4.76 (0.63) | .52 | 0.08 (−0.15, 0.30) |

| Smoking perceived likelihood of harm d | 4.12 (1.16) | 4.12 (1.12) | .96 | 0.01 (−0.22, 0.23) |

aHigher scores indicate greater message reactions.

bHigher scores indicate greater susceptibility.

cHigher scores indicate more negative attitudes.

dHigher scores indicate higher beliefs about harms.

| Outcome . | Vaping control ad, M (SD) . | The Real Cost vaping ad, M (SD) . | p . | Cohen’s d (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Message reactions | ||||

| Attention a | 2.39 (1.38) | 3.62 (1.25) | <.001 | 0.93 (0.69, 1.17) |

| Negative affect a | 1.98 (1.21) | 2.99 (1.40) | <.001 | 0.77 (0.54, 1.01) |

| Cognitive elaboration a | 2.72 (1.40) | 3.80 (1.28) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.57, 1.04) |

| Avoidance a | 2.23 (1.31) | 2.31 (1.45) | .60 | 0.06 (−0.17, 0.29) |

| Reactance a | 2.36 (1.29) | 2.27 (1.33) | .54 | −0.07 (−0.30, 0.16) |

| Targeted outcomes: Vaping | ||||

| Susceptibility to vaping b | 1.57 (0.71) | 1.43 (0.68) | .07 | −0.21 (−0.44, 0.02) |

| Vaping attitudes c | 4.33 (0.83) | 4.57 (0.69) | .009 | 0.30 (0.07, 0.53) |

| Vaping perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.54 (1.13) | 3.75 (1.09) | .09 | 0.20 (−0.03, 0.42) |

| Nontargeted outcomes: Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Susceptibility to smoking b | 1.32 (0.60) | 1.27 (0.59) | .44 | −0.09 (−0.32, 0.14) |

| Smoking attitudes c | 4.71 (0.72) | 4.76 (0.63) | .52 | 0.08 (−0.15, 0.30) |

| Smoking perceived likelihood of harm d | 4.12 (1.16) | 4.12 (1.12) | .96 | 0.01 (−0.22, 0.23) |

| Outcome . | Vaping control ad, M (SD) . | The Real Cost vaping ad, M (SD) . | p . | Cohen’s d (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Message reactions | ||||

| Attention a | 2.39 (1.38) | 3.62 (1.25) | <.001 | 0.93 (0.69, 1.17) |

| Negative affect a | 1.98 (1.21) | 2.99 (1.40) | <.001 | 0.77 (0.54, 1.01) |

| Cognitive elaboration a | 2.72 (1.40) | 3.80 (1.28) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.57, 1.04) |

| Avoidance a | 2.23 (1.31) | 2.31 (1.45) | .60 | 0.06 (−0.17, 0.29) |

| Reactance a | 2.36 (1.29) | 2.27 (1.33) | .54 | −0.07 (−0.30, 0.16) |

| Targeted outcomes: Vaping | ||||

| Susceptibility to vaping b | 1.57 (0.71) | 1.43 (0.68) | .07 | −0.21 (−0.44, 0.02) |

| Vaping attitudes c | 4.33 (0.83) | 4.57 (0.69) | .009 | 0.30 (0.07, 0.53) |

| Vaping perceived likelihood of harm d | 3.54 (1.13) | 3.75 (1.09) | .09 | 0.20 (−0.03, 0.42) |

| Nontargeted outcomes: Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Susceptibility to smoking b | 1.32 (0.60) | 1.27 (0.59) | .44 | −0.09 (−0.32, 0.14) |

| Smoking attitudes c | 4.71 (0.72) | 4.76 (0.63) | .52 | 0.08 (−0.15, 0.30) |

| Smoking perceived likelihood of harm d | 4.12 (1.16) | 4.12 (1.12) | .96 | 0.01 (−0.22, 0.23) |

aHigher scores indicate greater message reactions.

bHigher scores indicate greater susceptibility.

cHigher scores indicate more negative attitudes.

dHigher scores indicate higher beliefs about harms.

Participants exposed to The Real Cost vaping ads had more negative attitudes toward vaping compared with the vaping control ad (d = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.53) (Figure 2). The Real Cost vaping ads did not affect susceptibility to vaping (d = −0.21, 95% CI: −0.44, 0.02) or perceived likelihood of harm from vaping (d = 0.20, 95% CI: −0.03, 0.42) compared with the vaping control ad.

Exposure to The Real Cost vaping ads did not result in any spillover effects, with no differences in susceptibility to smoking (d = -0.09, 95% CI: −0.32, 0.14), smoking attitudes (d = 0.08, 95% CI: −0.15, 0.30), or perceived likelihood of harm from smoking (d = 0.01, 95% CI: −0.22, 0.23) compared with the vaping control ad.

Discussion

Communication campaigns are an effective strategy for reducing youth smoking,42–44 but little research has examined the spillover effects of tobacco prevention campaigns. In this experiment with a national sample of U.S. adolescents, we found evidence of the intended effects of the vaping prevention ads on vaping-related outcomes, beneficial spillover effects of smoking prevention ads on vaping outcomes, and no detrimental effects of vaping prevention ads on smoking outcomes. These findings are important because they add to the growing research on the effectiveness of vaping prevention ads for youth and suggest that smoking prevention ads could discourage both smoking and vaping.

As expected, we found the effects of The Real Cost vaping ads on vaping outcomes, which adds to the growing body of literature on the effectiveness of vaping prevention ads for youth.12,45 Specifically, compared with the control ad, The Real Cost vaping ads led to more attention, negative affect, cognitive elaboration, and negative attitudes about vaping, and most effect sizes were large (d > 0.80). A substantial body of research and theory suggests that changing these constructs is associated with subsequent behavior change24,46,47– therefore, our findings suggest that The Real Cost vaping ads are likely to be successful in changing vaping behaviors. While we did not observe effects of The Real Cost vaping ads on susceptibility to vaping and the perceived likelihood of harm from vaping, these findings were in the expected direction. Many youths in this experiment may have already seen ads from The Real Cost campaign, especially the vaping prevention ads which were more current than the smoking prevention ads.48 However, our experimental design should have balanced prior exposure to The Real Cost across experimental conditions, and thus any differences observed are likely because of the experimental manipulations, rather than any preexisting characteristics.

Importantly, exposure to The Real Cost smoking ads made youth less susceptible to vaping, led to more negative attitudes about vaping, and led to a higher perceived likelihood of harm from vaping, compared with the control ad. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experiment demonstrating that The Real Cost smoking ads’ impact may beneficially spill over to other tobacco products. Our findings stand in contrast to a previous experiment in which exposure to graphic cigarette warnings increased adult smokers’ intentions to switch to using other tobacco products.23 In our experiment, however, cigarette smoking prevention ads discouraged the use of other tobacco products (e-cigarettes) among youth, many of whom did not use tobacco. It is possible that when youth viewed ads about cigarette smoking, they implicitly thought about vaping because of connections among different tobacco products in adolescents’ minds, which is consistent with theories of spreading activation14 and attitude accessibility.15 Our findings, therefore, suggest that even as combustible tobacco product use continues to decline among youth,34 messages about smoking may continue to remain important, not only for their effects on cigarette smoking but also for their potential to dissuade the use of other tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes. Additionally, since our experiment found that prevention ads about one tobacco product influence beliefs about other tobacco products, the FDA and other organizations could consider proactively developing campaign ads that target multiple tobacco products simultaneously. Finally, future research should design longitudinal studies and conduct mediation analyses to examine why smoking prevention ads affect vaping outcomes over time and how pathways may differ for current versus never users.

Importantly, we found no effects of the vaping ads on smoking outcomes. There is a concern that messaging about vaping could lead youth to think vaping is more harmful than cigarette smoking or encourage them to smoke rather than vape. Promisingly, our experiment did not find any evidence of such detrimental spillover effects, but it also did not find any beneficial effects of The Real Cost vaping ads on cigarette outcomes. It is worth noting that two previous studies among adult tobacco users found that vaping communication messages did elicit lower interest in smoking and intention to smoke than control messages.19,49 It is possible that smoking outcomes did not change because youth in our experiment already perceived smoking very negatively, and these attitudes were so entrenched that they were difficult to influence with one exposure. One implication is that attitudes and beliefs toward different tobacco products may be connected in adolescents’ minds—consistent with spreading activation14 and attitude accessibility15 theories—but that prevention ads may not produce spillover effects for outcomes that are too entrenched to change. Future research could examine the impact of vaping prevention ads on the use of combustible tobacco products, including assessments of ads that directly compare the harms of vaping and smoking.

Finally, we did not observe effects of The Real Cost smoking prevention ads on cigarette smoking susceptibility, attitudes, or perceived likelihood of harm, which stands in contrast to previous research documenting the effectiveness of these ads.7–10 Potential reasons for these null findings include that smoking outcomes may be harder to change, our experiment was underpowered to detect effects of this size, there were floor or ceiling effects (e.g. susceptibility was low to begin within), or there was narrow variance in smoking outcomes. We did, however, find (1) effects on psychosocial outcomes were in the expected direction and (2) strong effects on attention, negative affect, and cognitive elaboration, which suggests that The Real Cost smoking prevention ads affect important constructs associated with subsequent behavior change.24,46,47 We also know from prior work that these ads are part of a larger campaign that was successful in changing population-level smoking-related beliefs8 and reducing initiation of cigarette smoking9 among youth.

The strengths of our study include the use of an experimental design, a national probability sample of adolescents, and use of high-quality ad stimuli. Limitations include the brief exposure to a single ad, no assessment of future behavior, and participants from only a single high-income country. Future research will need to establish the generalizability of our findings on these dimensions. In addition, our control ads were designed to be less engaging than ads from The Real Cost. Ads with higher production quality can elicit stronger emotional responses and thus be more impactful, particularly among young audiences, than ads with lower production quality.44,50 Future evaluations could explore to what extent production value versus other aspects of video ads (e.g. content, visual and audio features) are responsible for message effects. Finally, it is possible that prior exposure to The Real Cost ads accounted for some of the effects observed here, compared to the control ads which participants had never seen before. Future research should examine the ways in which prior exposure to ads does or does not affect ad impact in the context of experimental studies.

Conclusions

In a national sample of adolescents, our experiment found beneficial evidence of spillover effects of smoking ads on vaping outcomes and no detrimental effects of vaping ads on smoking outcomes. This is promising, as it suggests that smoking prevention campaigns may have the additional benefit of reducing both smoking and vaping among adolescents and further expands the field’s understanding of spillover effects. Additionally, vaping prevention campaigns did not elicit unintended consequences on smoking-related outcomes, an important finding given concerns that vaping prevention campaigns could drive youth to increase or switch to using combustible cigarettes instead of vaping. This work helps advance our understanding of communication effects in a modern, complex tobacco product environment. Our findings suggest that campaign evaluators should examine spillover effects when evaluating the success or failure of tobacco prevention campaigns.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://dbpia.nl.go.kr/ntr.

Funding

This project was supported by grant number R01CA246600 from the National Cancer Institute and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). MGH’s work on this paper was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number K01HL147713. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank NORC at the University of Chicago for their data collection efforts.

Disclosures

Seth Noar has served as a paid expert witnesses in litigation against tobacco and e-cigarette companies. Jennifer Mendel Sheldon has served as a paid consultant in government litigation against tobacco companies. IRB: The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures. Presentation of results: The article contents were presented during the 2022 annual meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT).

Author Contributorship

SMN, JMS, MGH, NCG, and NTB conceptualized the study. SMN acquired funding and JMS conducted project administration. SDK analyzed the data and drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Data Availability

Data are available upon reasonable request to Dr. Seth Noar at [email protected].

Comments