-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Allison J Lazard, Sydney Nicolla, Avery Darida, Marissa G Hall, Negative Perceptions of Young People Using E-Cigarettes on Instagram: An Experiment With Adolescents, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 23, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages 1962–1966, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab099

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Although e-cigarette marketing on social media increases positive attitudes and experimentation, little is known about non-influencer e-cigarette portrayals of young people.

High school adolescents (n = 928, 15–18) were recruited by Lightspeed Health for an online experiment and randomized to view an Instagram post with or without e-cigarette use. Outcomes were positive and negative perceptions (prototypes), social distance, and willingness to use.

Half (50%) of participants were susceptible to e-cigarette use. E-cigarettes shown (vs. not) led to less positive prototypes, p = .017, more negative prototypes, p = .004, and more social distance, p < .001. Negative prototypes and social distance were moderated by susceptibility (both p < .05); effects among non-susceptible adolescents only. Showing e-cigarettes did not impact willingness to use if offered.

Negative perceptions of e-cigarettes use challenge assumptions that vaping online is universally admirable. Highlighting unfavorable opinions of vaping or negative impacts for adolescents’ social image are potential strategies for tobacco counter-marketing.

Despite daily use of visual-based social media by most adolescents, little is known about the influence of e-cigarette use among young people online. Adolescent negative perceptions and desired distance from non-influencers using e-cigarettes on Instagram indicate digital e-cigarette portrayals are not universally accepted. Negative impacts for adolescents’ social image present a counter-marketing strategy.

Introduction

E-cigarette use has risen among adolescents in high school.1 Most adolescents use visual-based social media (eg, Instagram) daily,2 where portrayals of e-cigarette use from young people and the tobacco industry’s covert “influencer” advertisements have been viewed billions of times in the United States.3–5 Exposure to e-cigarette marketing on social media increases positive attitudes and e-cigarette use6–8; yet, little is known about how e-cigarette use among non-influencer young people is perceived.

Adolescents are motivated to use e-cigarettes (or not) via reasoned intention or reactive social pathways, according to the prototype/willingness model.9,10 The reactive process, via prototypes, is critical for adolescents without explicit goals for e-cigarette use.10 Tobacco user prototypes, or images of young people who vape or smoke, are strong predictors of attitudes and behavior in adolescents.11,12 Perceptions of young people using e-cigarettes (prototypes) can provide salient opinions to either encourage socialization or distancing from e-cigarette users and willingness to use e-cigarettes.13,14 Teens prioritize their social lives and often look to emerging adults, as older peers, on social media for behavioral cues and social opportunities.15

Social media exposure to e-cigarettes increases normalization and glamorization of use.6,16 However, emerging evidence suggests young people sometimes view e-cigarette use negatively,17 which discourages socializing with e-cigarette users or willingness to use e-cigarettes.18,19 While more socially acceptable than cigarettes, teens do not view vaping as universally “cool,” some look down on everyday vaping habits, and many are averse to heavy-handed references to “vape culture” on social media.18,20,21 To understand perceptions of authentic e-cigarette use by young people (not influencers or marketing) as they would appear on Instagram, we conducted an online experiment assessing prototype perceptions, desire for social distance, and willingness to use e-cigarettes.

Methods

Participants

In October 2019, a convenience sample of 928 high school adolescents (15–18 years old) was recruited by Lightspeed Health, a division of Kantar market research company with over 20 million US adults in their opt-in panels. Parents of teens ages 15–17 years old and 18-year-old high school students were contacted to participate. Parental consent was obtained for participants under 18 and all adolescents provided assent or consent online. The University of North Carolina Institution Review Board approved all study procedures.

Procedure

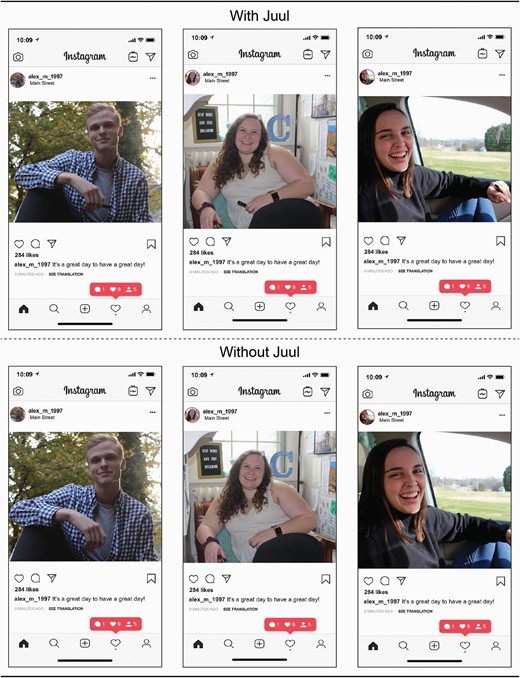

Photographs of three college students holding a Juul were taken by a member of the research team (AD) and used to create Instagram posts showing e-cigarette use for the treatment. For the comparison without e-cigarette use, the Juul was removed from each image in Photoshop (Figure 1). At the time of data collection, Juul was the most popular e-cigarette brand in the United States.22

Participants were randomly assigned to view an Instagram post showing e-cigarette use (or not) in the online experiment programmed in Qualtrics. Within their condition, participants were randomly shown one of the three possible Instagram posts. The Instagram post (with or without an e-cigarette) was shown as a static image embedded within the online survey. Participants answered items assessing positive and negative prototype perceptions, social distance, and willingness to use an e-cigarette. Participants reported their demographics, including susceptibility and e-cigarette use. This study was part of a larger survey; participants completed this study before a second study about vaping prevention social media messages.23 The median time of participation was 13 minutes for the full survey.

Measures

To assess prototype perceptions, participants reported how much the person in the Instagram post was “stylish,” “cool,” and “independent” (positive: α = .78), or “immature,” “inconsiderate,” and “trashy” (negative: α = .82).9 Social distance was assessed by how willing participants would be to “talk with this person [shown],” “go to a party with this person,” “be close friends with this person,” “have this person marry into your family,” and “set up your close friend on a date with this person” (α = .92).13 Response options ranged from “not at all” (coded as 1) to “extremely” (5).

Willingness was assessed with “if this person were to offer you an e-cigarette or other vaping device would you try it?” 24,25 Response options ranged from “definitely no” (1) to “definitely yes” (4). Participants were defined as susceptible to e-cigarette use if they responded “definitely yes,” “probably yes,” or “probably no” to one of three questions: “Have you ever been curious about using e-cigs or vaping devices”; “Do you think you might try an e-cigarette or vaping device soon”; or “If one of your best friend were to offer you an e-cigarette or other vaping device, would you use it?” 25 E-cigarette use was captured as using every day, some days, or not at all.

Data Analyses

To assess the impact of e-cigarette use on prototypes, a multivariate analysis of variance was conducted with positive and negative prototype scales. Separate analyses of variance were conducted to examine the effects of showing e-cigarettes on social distance and willingness to use e-cigarettes. In all analyses, susceptibility to e-cigarettes (non-susceptible vs. susceptible) was a potential moderator.

Results

Participants (n = 928) were between 15 and 18 years old (M = 16.08, SD = .87) and half female (52%; Appendix A). Participant mainly identified as white (81%) and non-Hispanic (90%). Half of participants (50%) were susceptible to e-cigarette use.

Adolescents who saw young adults using e-cigarettes (vs. not) on Instagram had less positive prototype perceptions about the person shown, F(1,923) = 5.70, p = .017, η 2 = .01 (Table 1). Adolescents also had more negative prototype perceptions of e-cigarette users (vs. nonusers), F(1,923) = 8.40, p = .004, η 2 = .01. E-cigarette susceptibility moderated the effects on negative prototype perceptions, F(1,923) = 4.59, p = .032. Showing e-cigarette use led to more negative prototype perceptions among non-susceptible adolescents, p < .001, but not among adolescents susceptible to e-cigarette use, p = .595. Susceptibility did not moderate positive prototype perceptions.

| . | Overall . | . | . | Susceptible . | Non-susceptible . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | F . | p . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | F . | p . |

| Positive prototypes Person in post perceived as cool, etc. | 2.87 (.93) | 3.01 (.91) | 5.70 | .017 | 2.94 (.92) | 3.05 (.85) | 2.80 (.94) | 2.97 (.96) | .24 | .626 |

| Negative prototypes Person in post perceived as inconsiderate, etc. | 1.48 (.82) | 1.33 (.69) | 8.40 | .004 | 1.46 (.79) | 1.42 (.72) | 1.50 (.86) | 1.25 (.65) | 4.59 | .032 |

| Social distance Desire to interact with person in post | 2.68 (1.00) | 2.99 (1.07) | 22.72 | <.001 | 2.86 (.99) | 3.05 (1.00) | 2.47 (.98) | 2.93 (1.12) | 4.14 | .042 |

| Willingness to use e-cigarette If offered from person in post | 1.38 (.70) | 1.37 (.71) | .12 | .734 | 1.68 (.83) | 1.66 (.83) | 1.06 (.29) | 1.10 (.44) | .55 | .459 |

| . | Overall . | . | . | Susceptible . | Non-susceptible . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | F . | p . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | F . | p . |

| Positive prototypes Person in post perceived as cool, etc. | 2.87 (.93) | 3.01 (.91) | 5.70 | .017 | 2.94 (.92) | 3.05 (.85) | 2.80 (.94) | 2.97 (.96) | .24 | .626 |

| Negative prototypes Person in post perceived as inconsiderate, etc. | 1.48 (.82) | 1.33 (.69) | 8.40 | .004 | 1.46 (.79) | 1.42 (.72) | 1.50 (.86) | 1.25 (.65) | 4.59 | .032 |

| Social distance Desire to interact with person in post | 2.68 (1.00) | 2.99 (1.07) | 22.72 | <.001 | 2.86 (.99) | 3.05 (1.00) | 2.47 (.98) | 2.93 (1.12) | 4.14 | .042 |

| Willingness to use e-cigarette If offered from person in post | 1.38 (.70) | 1.37 (.71) | .12 | .734 | 1.68 (.83) | 1.66 (.83) | 1.06 (.29) | 1.10 (.44) | .55 | .459 |

| . | Overall . | . | . | Susceptible . | Non-susceptible . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | F . | p . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | F . | p . |

| Positive prototypes Person in post perceived as cool, etc. | 2.87 (.93) | 3.01 (.91) | 5.70 | .017 | 2.94 (.92) | 3.05 (.85) | 2.80 (.94) | 2.97 (.96) | .24 | .626 |

| Negative prototypes Person in post perceived as inconsiderate, etc. | 1.48 (.82) | 1.33 (.69) | 8.40 | .004 | 1.46 (.79) | 1.42 (.72) | 1.50 (.86) | 1.25 (.65) | 4.59 | .032 |

| Social distance Desire to interact with person in post | 2.68 (1.00) | 2.99 (1.07) | 22.72 | <.001 | 2.86 (.99) | 3.05 (1.00) | 2.47 (.98) | 2.93 (1.12) | 4.14 | .042 |

| Willingness to use e-cigarette If offered from person in post | 1.38 (.70) | 1.37 (.71) | .12 | .734 | 1.68 (.83) | 1.66 (.83) | 1.06 (.29) | 1.10 (.44) | .55 | .459 |

| . | Overall . | . | . | Susceptible . | Non-susceptible . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | F . | p . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | With Juul M (SD) . | Without Juul M (SD) . | F . | p . |

| Positive prototypes Person in post perceived as cool, etc. | 2.87 (.93) | 3.01 (.91) | 5.70 | .017 | 2.94 (.92) | 3.05 (.85) | 2.80 (.94) | 2.97 (.96) | .24 | .626 |

| Negative prototypes Person in post perceived as inconsiderate, etc. | 1.48 (.82) | 1.33 (.69) | 8.40 | .004 | 1.46 (.79) | 1.42 (.72) | 1.50 (.86) | 1.25 (.65) | 4.59 | .032 |

| Social distance Desire to interact with person in post | 2.68 (1.00) | 2.99 (1.07) | 22.72 | <.001 | 2.86 (.99) | 3.05 (1.00) | 2.47 (.98) | 2.93 (1.12) | 4.14 | .042 |

| Willingness to use e-cigarette If offered from person in post | 1.38 (.70) | 1.37 (.71) | .12 | .734 | 1.68 (.83) | 1.66 (.83) | 1.06 (.29) | 1.10 (.44) | .55 | .459 |

Adolescents who saw e-cigarette use desired more social distance (less socialization) from the young adults shown than those who saw Instagram posts without e-cigarettes, F(1,924) = 22.72, p < .001, η 2 = .02. Susceptibility to e-cigarettes moderated this effect; showing e-cigarettes led to more social distancing among non-susceptible adolescents, p < .001, but not among those susceptible to e-cigarette use, p = .054. E-cigarette use did not moderate prototype perceptions or social distancing. Showing e-cigarette use on Instagram did not impact adolescents’ willingness to use e-cigarettes if offered, p = .734.

Discussion

This study provides insights for adolescent responses to e-cigarette use on social media. Adolescents perceived young adults using e-cigarettes on Instagram less positively than those same individuals without e-cigarettes. For adolescents across all e-cigarette use statuses—those who vape, those who do not, and those who will not—the young people shown were perceived as less “stylish,” “cool,” and “independent” when an e-cigarette was in the Instagram post (vs. the same person without an e-cigarette). Despite the likelihood that susceptible adolescents may perceive e-cigarette use more positively, we did not find evidence for this. Susceptibility for vaping did not moderate the main effect of lower positive prototype perceptions when e-cigarettes were shown (vs. not). Those most at risk for e-cigarette use did not think young people were cooler when they had an e-cigarette in the Instagram post.

Moreover, non-susceptible adolescents—the social contacts of teens who vape—perceived those shown with e-cigarettes as more “immature,” “inconsiderate,” and “trashy.” Non-susceptible adolescents who saw the e-cigarette post also desired less social contact from e-cigarette users, compared with those who saw the post without an e-cigarette.

Among susceptible adolescents, showing e-cigarettes did not lead to higher or lower negative prototype perceptions. Susceptible adolescents were also not more or less likely to desire social opportunities. In other words, youth most at risk for vaping were neither repelled by nor desired more social contact with young people with e-cigarettes. Showing e-cigarettes did not impact willingness to use an e-cigarette.

Our findings challenge assumptions that adolescents find e-cigarette use stylish or admirable,6,16,26 shedding light that adolescents think less positively of young people who display their Juul or other popular vaping devices on social media. Our work contributes to growing evidence that youth disapprove of regular use of e-cigarettes and look down on posting about vape culture on social media.18,20 Adolescents’ unfavorable prototype perceptions suggest e-cigarette use on Instagram could negatively impact one’s social image and be leveraged as a strategy to counter-marketing appeals.17,19 In this way, e-cigarette counter-marketing messages can leverage adolescents’ most pressing concern—their social lives. Adolescents often ignore long-term health consequences, however, adolescent brains are highly attentive and receptive to social influences (eg, loss of social standing).23,27 Strategies to downplay the social appeal of smoking have contributed to tobacco control efforts, but are not without potential unintended consequences, such as introducing stigma.28 Public health efforts that carefully balance reduced social appeal of vaping without social identity threats should be evaluated as promising strategies to reduce youth e-cigarette use.

This study is limited to the images shown and the convenience sample of teens. Future research should continue to monitor unfavorable opinions of e-cigarette users with diverse adolescent populations to inform prevention efforts. Additionally, participants responses were captured after they saw a single Instagram post embedded in the survey. Responses to organic social media encounters, as a natural part of an Instagram feed, are needed. Viewing many peers from one’s social network, or visible influencers, using e-cigarettes may have different effects on prototype perceptions or desires for social interactions.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://dbpia.nl.go.kr/ntr.

Funding

This research was supported by a seed grant from the Hussman School of Journalism and Media and an IBM Junior Faculty Development Award from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. K01HL147713 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH supported Marissa Hall’s time writing the paper. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Comments