-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kymberle L Sterling, Monika Vishwakarma, Kimberly Ababseh, Lisa Henriksen, Flavors and Implied Reduced-Risk Descriptors in Cigar Ads at Stores Near Schools, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 23, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages 1895–1901, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab136

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Although the FDA prohibits using inaccurate, reduced-risk descriptors on tobacco product advertising, descriptors that imply reduced risk or an enhanced user experience may be present on cigar product advertising in retail outlets near schools. Therefore, to inform the development of federal labeling and advertising requirements that reduce youth appeal of cigars, we conducted a content analysis of cigar ads in retailers near schools to document the presence of implied health claims and other selling propositions that may convey enhanced smoking experience.

Up to four interior and exterior little cigar and cigarillo advertisements were photographed in a random sample of licensed tobacco retailers (n = 530) near California middle and high schools. Unique ads (n = 234) were coded for brand, flavor, and presence of implicit health claims, premium branding descriptors, and sensory descriptors. Logistic regressions assessed the association among flavored ads and presence of implicit health claims, premium branding, or sensory descriptors.

Seventeen cigar brands were advertised near schools; Black & Mild (20.1%) and Swisher Sweets (20.1%) were most common. Flavor was featured in 64.5% of ads, with explicit flavor names (eg, grape) being more prevalent than ambiguous names (eg, Jazz) (49.6% vs. 34.2%). Compared to ads without flavors, ads with ambiguous flavors were more likely to feature implicit health claims (OR = 1.83, 95% CI = 1.06% to 3.19%) and sensory descriptors (OR = 2.64, 95% CI = 1.39% to 5.04%); ads with explicit flavors were more likely to feature premium branding (OR = 2.84, 95% CI = 1.53% to 5.41%).

Cigar ads that featured implicit health claims and premium branding, and sensory selling propositions are present at retailer stores near schools.

We document the presence of implied health claims, premium branding, and sensory descriptors on cigar ads found in retail settings near schools. This study adds to the body of evidence that supports the development of federal labeling and advertising requirements for cigar products to reduce their appeal among vulnerable groups.

Introduction

Cigars, including little filtered cigars and cigarillos, are among the most commonly used combustible tobacco products used by youth, and use is highest among males, youth of color (eg, Black and/or African Americans), and those who have used other tobacco products (eg, cigarettes).1 Cigar products (cigarillos, wraps, large cigars, and little filtered cigars) are available in sweet, fruit, alcohol, and other flavors that appeal to youth (citation).2–4 By year-end 2020, eight states and more than 290 localities restricted sales of flavored non-cigarette tobacco products.5 To circumvent the regulation, however, tobacco companies manufacture flavored cigars with ambiguous descriptors (ie, “concept” flavors, such as “Jazz,” “Blue,” and “Tropical Twist”), and their sales have proliferated.6

Beyond flavor characteristics, cigar products are labeled and advertised with descriptors that may imply to users that the product or its use presents a lower risk of disease, reduced risk of exposure to a potentially harmful substance, or is free of potentially harmful substances.7–9 The FDA prohibits using descriptors on the packaging and advertising that may convey reduced risk or exposure messages unless the manufacturer demonstrates that the descriptors are accurate, do not mislead consumers, and benefit the public’s health.10 In August 2015, the FDA sent warning letters to certain cigarette tobacco companies stating that descriptors such as “natural” and “additive-free” were a form of misbranding and violated section 911 of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act.11 “Natural” and descriptors like “fresh” may indicate to consumers that the tobacco product has not been altered or genetically modified.12 These descriptors are still found on some tobacco packaging and advertising and may be associated with perceptions of lower risk, increased appeal, and purchase intentions among youth and adults.12,13 Product descriptors that may convey reduced harm are often present in cigar advertising and package labeling. A content analysis of 34 cigar advertisements from Trinkets & Trash reported the presence of product descriptors, such as “natural” and “fresh” on cigar ads. It noted that these might be used as a marketing strategy to lessen health risk concerns.14 In focus groups with little cigar and cigarillo users and nonusers, young adults described how pack images, colors, flavor descriptors, and product features, such as filters, influenced their taste perceptions.15 Experimental evidence also demonstrates that the presence of flavor descriptors and colors significantly influenced product perceptions among young-adult little cigar and cigarillo users and nonusers.9

Tobacco product promotion, including cigars, occurs mainly in the retail environment at point-of-sale.16 Giovenco et al found almost a third of tobacco advertisements at New York City retailers featured cigar products.17 To inform federal labeling and advertising requirements for cigars, this content analysis study builds on prior research in two ways. Unlike previous content analyses of print media (including direct mail and magazine ads)14,18–21 and social media advertising14,21–23, the current study addresses a gap in the literature by examining cigar ads that were photographed in the retail environment near schools. Additionally, we expand upon prior research by examining the cigar-specific selling propositions, including promotion of product flavor, health claims that may imply reduced-risk, product sensory descriptors (eg, taste, smell), and premium branding claims that focus on promoting a “high-end product” 19 that may influence youth appeal and risk perceptions about the harmfulness of cigars.10,19

Materials and Methods

Advertisements for this study were derived from retail marketing surveillance near a statewide sample of 114 middle and high schools that completed the 2015–2016 California Student Tobacco Survey.24 Using ArcGIS (v10.1, ESRI) and a state tobacco retail license list (mapping rate = 99%), we identified all stores within ½ mile (straight line) of school boundary shapefiles that we obtained or created.25 For schools without any stores within ½ mile, we increased the boundary to 1 mile (n = 18) or 2 miles (n = 2). We telephoned stores thus identified (n = 1211) to confirm they sold little cigar and cigarillos (completion rate = 79.2%, eligibility = 79.0%). In school neighborhoods with six or fewer stores that sold little cigar and cigarillos, we sampled all of them. In 48 neighborhoods, we randomly selected 50% or 6, whichever yielded the larger number. Across the sample of observed stores (n = 530), the median distance to schools was 0.35 miles (Min = 0.01, Max = 1.72).

Professional data collectors visited stores between December 2015 and May 2016 (M = 4.0 per school, SD = 2.1, completion rate = 97.4%). As part of a surveillance task to assess product availability, promotion, and price, data collectors also recorded the presence of any cigar advertising, defined as branded, preprinted signs, decals, or shelf strips (no minimum size was specified). Using an iPod Touch, data collectors were instructed to photograph up to four advertisements inside the store and four advertisements outside each store. This yielded 1405 photographs from which 465 cigar advertisements were identified, excluding ads for other tobacco products. We excluded 27 cigar ads that were poor-quality photos. The remaining images were sorted by brand and location (exterior, interior), and each was assigned a unique ID. Reviewing each collection of brand-specific photos, separately for interior and exterior advertisements, we removed 180 duplicates, using a stringent definition for elimination. For example, any variation in product price, package size, or promotional offers of the same brand was treated as a unique ad. Reserving a random subsample of 24 “practice” ads for coding protocol development and training, the analysis sample included 234 unique ads.

Content Analysis

Our coding protocol was informed by reviewing company Web sites for popular cigarillo brands and the “practice” ads. We developed and refined a coding scheme to record multiple attributes of advertisements, such as type of advertisement (sign, decal or shelf strip), presence of packaging (yes, no), and product descriptors, including flavor categories (if any). The 21-item coding form was programed in Qualtrics. Two authors (LH, KS) each coded half of the advertisements, and 23 randomly selected ads were coded by both authors independently to assess interrater reliability (IRR).

Product Descriptors

Expanding on an established coding scheme for implicit health claims in cigarette advertising,26 advertisements were coded for the terms “natural,” “mild,” “filter,” and “100% tobacco.” The presence of one or more of these terms indicated an implicit health claim. In addition, advertisements contained a sensory descriptor if product packaging or other ad language mentioned “gentle,” “smooth,” “fresh,” “refreshing,” or “satisfying.” Finally, advertisements contained premium branding descriptors if product packaging or other ad language referred to “quality,” “fine,” “finest,” “premium,” or “hand-rolled.”

Flavor Categories

We began with a list of 10 flavor categories based on the evidence on cigar product sales.8,27 These categories were later classified as explicit flavors and ambiguous flavors for subsequent analyses. The Explicit flavors category included food or beverage, “sweet,” and mint, menthol-flavored products. The food or beverages category consisted of unambiguous flavor names that were either alcohol, candy, dessert, coffee, tea, fruit, or other beverage or food flavor. Other flavors, such as “sweet” and mint or menthol, were categorized separately.

Ads with flavor names that could not be classified as a distinct flavor category were placed in the Ambiguous flavor category. Examples of Ambiguous flavor names included those with a color name (eg, Red) or other concept flavors (eg, Island Madness). Ads that portrayed tobacco-flavored products were placed in an Unflavored category.

Some ads depicted a product line of all flavor varieties, showing cigar packs like a hand of playing cards, such that pack colors were visible, but flavor descriptors were not. To assist in describing what flavors were advertised for these cases, we created a dictionary of product images for each brand in the dataset, using images from the company Web sites and other online vendors. Coders relied on the flavor dictionary to code 26.5% of all ads. Nine ads that were too dark or faded to discern the flavor varieties from the codebook were grouped with ads with no flavor descriptors.

Cigar Brands and Manufacturers

We developed a list of unique brands that appeared in the cigar advertisements. After coding, we searched brand Web sites to link each brand with a manufacturer, parent company.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized the percent of unique ads by store location (exterior, interior), cigar manufacturer and brand, flavor categories, and other product descriptors. Tobacco (unflavored) cigar products’ ads were grouped with ads that had no flavor descriptors. Analyses focused on differences by manufacturers as in previous studies.28 A parallel analysis by brand for the three leading manufacturers was nearly redundant. Chi-square tests examined whether the presence of descriptors (implicit health claims, premium branding, and sensory) and presence of a flavor (yes, no) differed by the manufacturer (Altria, Imperial Brands, Swisher International, and “other” manufacturers). If omnibus chi-square tests were significant, we tested pairwise comparisons to examine if the cigar descriptors and presence of flavors differed between manufacturers. Logistic regressions tested whether ads with implicit health claims, premium branding, or sensory descriptors were more or less likely to feature ambiguous or explicit flavor descriptors. Supplemental figures include illustrative images from the set of retail cigar ads.

Results

Sample Description

Table 1 summarizes characteristics of retail cigar advertisements near schools by ad location (store interior or exterior). The sample of 234 retail cigar ads near schools included 17 different cigar brands. Most were from three manufacturers: Altria (23.1%), Imperial Brands (26.9%), and Swisher International (21.8%) (see Table 1). Three brands comprised the majority of ads: 20.1% Black & Mild (Altria), 20.1% Swisher Sweets (Swisher Intl), and 16.7% Dutch Masters (Imperial Brands). Across all brands, the median number of ads per brand was 5 (mean = 11, SD = 14).

Characteristics of Retail Cigar Ads Near California Schools, by Ad Location

| . | Interior (n = 139) (%) . | Exterior (n = 95) (%) . | Total (n = 234) (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturers | |||

| Altriaa | 28.8 | 14.7 | 23.1 |

| Imperial Brandsb | 20.9 | 35.8 | 26.9 |

| Swisher Internationalc | 23.7 | 18.9 | 21.8 |

| “Other” manufacturersd | 26.6 | 30.5 | 28.2 |

| Product descriptors | |||

| Implicit health claims | 41.0 | 48.4 | 44.0 |

| Premium branding | 17.3 | 36.8 | 25.2 |

| Sensory | 19.4 | 25.3 | 21.8 |

| Flavors | |||

| Explicit | 45.3 | 55.8 | 49.6 |

| Ambiguous | 33.8 | 34.7 | 34.2 |

| Nonee | 38.8 | 30.5 | 35.5 |

| . | Interior (n = 139) (%) . | Exterior (n = 95) (%) . | Total (n = 234) (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturers | |||

| Altriaa | 28.8 | 14.7 | 23.1 |

| Imperial Brandsb | 20.9 | 35.8 | 26.9 |

| Swisher Internationalc | 23.7 | 18.9 | 21.8 |

| “Other” manufacturersd | 26.6 | 30.5 | 28.2 |

| Product descriptors | |||

| Implicit health claims | 41.0 | 48.4 | 44.0 |

| Premium branding | 17.3 | 36.8 | 25.2 |

| Sensory | 19.4 | 25.3 | 21.8 |

| Flavors | |||

| Explicit | 45.3 | 55.8 | 49.6 |

| Ambiguous | 33.8 | 34.7 | 34.2 |

| Nonee | 38.8 | 30.5 | 35.5 |

Cell entries are column percents.

aBlack & Mild and Royal Comfort.

bDutch Masters, Backwoods, Krome, and Phillies.

cSwisher Sweets, ACID, and Optimo.

dCosa Nostra, PomPom, Clipper, Al Capone, ZigZag, Garcia y Vega, White Owl, and Jackpot.

eNone includes ads with tobacco “flavors,” ads with no flavor descriptors, and nine ads that could not be coded for flavor.

Characteristics of Retail Cigar Ads Near California Schools, by Ad Location

| . | Interior (n = 139) (%) . | Exterior (n = 95) (%) . | Total (n = 234) (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturers | |||

| Altriaa | 28.8 | 14.7 | 23.1 |

| Imperial Brandsb | 20.9 | 35.8 | 26.9 |

| Swisher Internationalc | 23.7 | 18.9 | 21.8 |

| “Other” manufacturersd | 26.6 | 30.5 | 28.2 |

| Product descriptors | |||

| Implicit health claims | 41.0 | 48.4 | 44.0 |

| Premium branding | 17.3 | 36.8 | 25.2 |

| Sensory | 19.4 | 25.3 | 21.8 |

| Flavors | |||

| Explicit | 45.3 | 55.8 | 49.6 |

| Ambiguous | 33.8 | 34.7 | 34.2 |

| Nonee | 38.8 | 30.5 | 35.5 |

| . | Interior (n = 139) (%) . | Exterior (n = 95) (%) . | Total (n = 234) (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturers | |||

| Altriaa | 28.8 | 14.7 | 23.1 |

| Imperial Brandsb | 20.9 | 35.8 | 26.9 |

| Swisher Internationalc | 23.7 | 18.9 | 21.8 |

| “Other” manufacturersd | 26.6 | 30.5 | 28.2 |

| Product descriptors | |||

| Implicit health claims | 41.0 | 48.4 | 44.0 |

| Premium branding | 17.3 | 36.8 | 25.2 |

| Sensory | 19.4 | 25.3 | 21.8 |

| Flavors | |||

| Explicit | 45.3 | 55.8 | 49.6 |

| Ambiguous | 33.8 | 34.7 | 34.2 |

| Nonee | 38.8 | 30.5 | 35.5 |

Cell entries are column percents.

aBlack & Mild and Royal Comfort.

bDutch Masters, Backwoods, Krome, and Phillies.

cSwisher Sweets, ACID, and Optimo.

dCosa Nostra, PomPom, Clipper, Al Capone, ZigZag, Garcia y Vega, White Owl, and Jackpot.

eNone includes ads with tobacco “flavors,” ads with no flavor descriptors, and nine ads that could not be coded for flavor.

Most retail cigar advertisements (59.4%) were interior ads and 40.6% were exterior. Of the interior ads, the majority (59.7%) were either signs or window decals, 38.1% were shelf strips, and 2.2% were classified as “other.” Almost all (96.8%) of the exterior store ads were either signs or window decals, but a few were standalone sidewalk displays (see Supplemental Figure 1). More than half of the ads (53.4%) either portrayed the packaging or showed a cigar product, 22.7% showed both packages and the cigar products they contained, and 23.9% of ads did not show any packaging or cigar products.

Product Descriptors

As shown in Table 1, implicit health claims were found in 44% of the retail cigar ads. “Natural” was the most common implicit health descriptor, appearing in 21.4% of ads and was used to characterize the tobacco inside the cigar or the cigar leaf itself. For example, ACID cigars (manufacturer, Swisher International) prominently advertises “NATURAL LEAF” in a large bold, yellow font (Supplemental Figure 2A). “Mild” appeared in 20.9% of ads. Excluding ads for “Black & Mild,” which has the descriptor as its brand name, 1.7% (n = 4) of ads included the “mild” descriptor, all for Backwoods (Altria), with the slogan “Wild N Mild” (Supplemental Figure 2B).

Premium branding descriptors appeared in 25.2% of ads (see Table 1). “Fine, finest, premium” were the most common descriptors, occurring in 19.2% of the ads. Of note, “finest” and “quality” were present on each package of the Swisher Sweets 2-pack cigarillos that was shown in the ad but did not appear in every advertisement for that brand (Supplemental Figure 2C).

Sensory descriptors appeared in 21.8% of ads (see Table 1). “Gentle, calm, smooth” were the most common sensory descriptors (14.5%). Several Zig Zag ads featured the descriptor “smooth” (Supplemental Figure 2D).

Associations Between Cigar Product Descriptors and Manufacturers

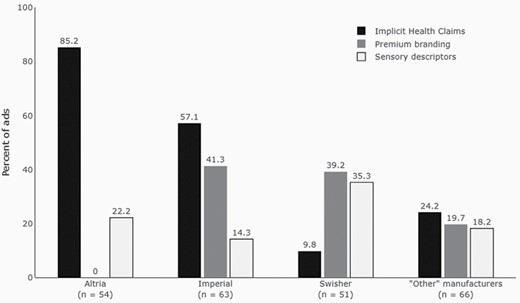

Figure 1 illustrates the prevalence of product descriptors by the manufacturer. Supplemental Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics by brand. Focusing on manufacturers, there were significant differences for the use of implicit health claims (□ 2 = 76.24, p ≤ .01), appearing in nearly all ads (85.2%) from Altria (Black & Mild manufacturer), and more than half (57.1%) of ads from Imperial Brands. Five of the six pairwise comparisons were significant (see Supplemental Table 2). For example, significantly more Altria ads had implicit health claims than ads from Imperial Brands, Swisher International, and those from “other” manufacturers (data shown in Figure 1; p’s < .01). In addition, significantly more ads from Imperial Brands had implicit health claims than Swisher and “other” manufacturers (see Supplemental Table 2).

Product descriptors in California retail cigar ads, by manufacturer (n = 234). Notes: A parallel analysis by brand for the three main brands was nearly redundant. Pairwise comparison data can be found in Supplemental Materials as tables. “Other” manufacturers include those excluding Altria, Swisher Sweets, and Imperial Brands.

Premium branding descriptors were found in roughly 40% of Imperial Brands and Swisher International ads and almost 20% of “other” manufacturers. Altria ads, however, had no premium branding descriptors (see Figure 1). In addition, the presence of premium branding descriptors differed by the manufacturer (□ 2 = 33.19, p < .01). All pairwise comparisons were statistically significant except Swisher and Imperial Brands (see Supplemental Table 2).

The presence of sensory descriptors also differed by the manufacturer (□ 2 = 8.05, p = .04). The only significant pairwise comparison was that a greater percentage of Swisher International ads had sensory descriptors than those from Imperial Brands (see Supplemental Table 2). Swisher Sweets ads often included several sensory descriptors, such as fresh, smooth, and satisfying. Additionally, most Swisher Sweets cigarillos packages include the “smooth” and “satisfying” descriptors (see Supplemental Figure 2a).

Cigar Flavors

As shown in Supplemental Figure 3, 64.5% of retail cigar ads featured any flavor. Almost half (49.6%) of all ads featured any explicit flavor name; of those, fruit was the most common (32.1% of all ads). Regarding explicit flavors, almost 40% of ads featured food, beverage flavor names; 18.0% of those featured alcohol-flavored cigars (eg, Blackberry Mojito, White Russian). Nearly one-third of explicit flavor ads (30.3%) featured “sweet” flavored cigars, and only 5.6% of ads featured mint or menthol-flavored cigars. Ambiguous flavor descriptors appeared in 34.2% of all ads, with concept flavors (26.9%), like Casino, being more common than color names, like Blue (13.2%). Unflavored cigars (ie, “tobacco” flavor) were featured in 9.8% of all ads. In 34.2% of all ads, there was no product image or descriptor from which we could discern a flavor.

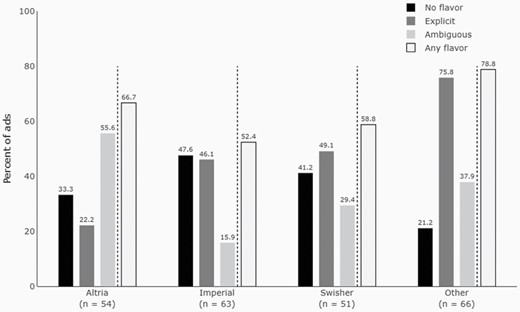

Association Between Cigar Flavor Categories and Manufacturers

Regardless of manufacturer, most ads featured any flavor descriptors, either explicit, ambiguous, or both (see Figure 2). However, the presence of any flavor descriptors differed across manufacturers (□ 2 =10.76, p = .013), and the results from pairwise comparisons suggest that ads from Imperial Brands were less likely than “other” manufacturers to contain any flavor descriptors (52.4% vs. 78.8%, p < .05). Ads from Swisher International were also less likely than “other” manufacturers to have any flavor descriptors (58.8% vs. 78.8%, p < .05).

Flavors in California retail cigar ads, by manufacturer (n = 234). Notes: Any flavor—ads with any one of the flavors (Food, beverage, Sweet, Menthol, Mint, Color or Concept). No flavor—includes ads with no flavor descriptor, a tobacco flavor descriptor only, and ads that could not be coded for flavor.

Association Between Cigar Product Descriptors and Flavor Categories

As shown in Table 2, implicit health claims were significantly more common in ads with ambiguous flavors (OR = 1.83, 95% CI = 1.06% to 3.19%) than ads without any flavors. For instance, “natural leaf” was highlighted on several Dutch Masters ads for ambiguous flavors such as Atomic Fusion Fire (see Supplemental Figure 4A). Likewise, premium branding descriptors were significantly more common in advertisements with explicit flavor names than ads without any flavor names (OR = 2.84, 95% CI = 1.53% to 5.41%). For example, an advertisement for Al Capone cigarillos included “premium” and “hand-rolled” descriptors on its sweet flavored cigar (see Supplemental Figure 4B). Finally, sensory descriptors were significantly more common in ads with ambiguous flavor names than ads without any flavors (OR = 2.64, 95% CI = 1.39% to 5.04%). For example, a Black & Mild ad used “smooth” and “rich” to characterize its “Casino” flavored cigar (see Supplemental Figure 4C).

| . | Implicit health claims . | Premium branding . | Sensory descriptors . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| No flavorsa | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Ambiguous | 1.83 | 1.06, 3.19 | 0.71 | 0.36, 1.35 | 2.64 | 1.39, 5.04 |

| Explicit | 0.94 | 0.56, 1.59 | 2.84 | 1.53, 5.41 | 1.85 | 0.97, 3.60 |

| . | Implicit health claims . | Premium branding . | Sensory descriptors . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| No flavorsa | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Ambiguous | 1.83 | 1.06, 3.19 | 0.71 | 0.36, 1.35 | 2.64 | 1.39, 5.04 |

| Explicit | 0.94 | 0.56, 1.59 | 2.84 | 1.53, 5.41 | 1.85 | 0.97, 3.60 |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

aThis category includes ads with no flavor descriptor, a tobacco flavor descriptor only, and ads that could not be coded for flavor.

| . | Implicit health claims . | Premium branding . | Sensory descriptors . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| No flavorsa | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Ambiguous | 1.83 | 1.06, 3.19 | 0.71 | 0.36, 1.35 | 2.64 | 1.39, 5.04 |

| Explicit | 0.94 | 0.56, 1.59 | 2.84 | 1.53, 5.41 | 1.85 | 0.97, 3.60 |

| . | Implicit health claims . | Premium branding . | Sensory descriptors . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| No flavorsa | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Ambiguous | 1.83 | 1.06, 3.19 | 0.71 | 0.36, 1.35 | 2.64 | 1.39, 5.04 |

| Explicit | 0.94 | 0.56, 1.59 | 2.84 | 1.53, 5.41 | 1.85 | 0.97, 3.60 |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

aThis category includes ads with no flavor descriptor, a tobacco flavor descriptor only, and ads that could not be coded for flavor.

Interrater Reliability

There was high IRR about the presence of implicit health claims (κ = 1.0) and premium branding descriptors (κ = 1.0), and substantial coder agreement about sensory descriptors (κ = 0.74). However, percent agreement for the flavor categories varied and included 91.3% (κ = 0.75) for fruit, 87.0% (κ = 0.36) for color names of ambiguous flavor categories, 78.3% (κ = 0.51) for food, beverage category, 78.3% (κ = 0.47) for concept, and 65.0% (κ = 0.19) for “sweet.” The IRR for mint or menthol-flavored cigar ads was not calculated as there were no ads with this flavor in the IRR sample.

Discussion

This study documents the presence of flavored cigar product advertising in retail stores near middle and high schools in California. The advertisements featured product descriptors that may communicate messages about health, market inexpensive cigarillos as “premium” products, and characterize sensory experiences of cigar product use. The retail environment is where the preponderance of tobacco marketing and is the dominant channel for young people’s exposure to tobacco marketing.16 Giovenco et al found that cigar advertisements were frequently placed on the door of entry or window, increasing their likelihood of visibility.17 Cigar features are appealing to youth29–31 and recall of retail point-of-sale cigar ads is associated with cigar use susceptibility and ever and use among some youth.32 Omnipresent cigar advertising at stores in school neighborhoods increases the likelihood that students will be exposed to these appealing ads.

Approximately 65% of retail cigar ads near California schools featured flavored cigar products, including those categorized as explicit (eg, fruit, food, beverages, or sweets) and ambiguous (ie, concept flavors such as “Jazz” or a color like “Red”). Cigar ads featuring explicit flavors were more prevalent in our sample than those featuring ambiguous or other flavors. Food and beverage flavored cigar ads represented a large proportion of explicit flavored cigar ads. For instance, Swisher International ads had flavor names such as Chocolate and Wine. Concept flavors were also evident, such as Casino and Jazz (Altria) and Jamaican Blaze (The Dannemann Company). Our findings complement research about cigar marketing from retail sales data that indicate an increase in flavored cigars with concept flavor names. Between 2012 and 2016, Gammon et al reported that cigarillos, compared to little filtered cigars and large cigars, had the greatest increase in concept flavor descriptors, with most sales occurring among concept flavors of “Sweet” and “Jazz.” 8

Almost 35% of ads did not portray a flavored cigar or list a flavor name or descriptor on its advertisement. The low representation of cigars that did not advertise a characterizing flavor in our sample is consistent with evidence that shows that most cigar products are flavored. Youth exposure to flavored tobacco advertising is associated with increased product appeal, lower perceptions of risk and harm, increased perceived benefits of use, and may encourage cigar use initiation among youth.33 Our findings add to the body of evidence that may support California and other statewide legislation that would seek to implement a ban on the sale of all categories of flavored tobacco products, including explicit and ambiguous flavors, to reduce their appeal and curb use among youth. Pending a voter referendum, a California state law to restrict the sales of flavored tobacco would eliminate flavored cigars and, presumably, retail advertising for these products.

More than 20% of retail cigar ads near California schools featured implicit health claims; “natural” and “mild” were the most common descriptors. Cigar ads from Altria (Black & Mild and Royal Comfort brands) and Imperial Tobacco Brands (Dutch Masters, Backwoods, Phillies, and Krome) were more likely to feature implicit health claim descriptors, including “natural.” The FDA prohibits using descriptors on tobacco packaging or advertising that may convey reduced risk or exposure; that is, unless the manufacturer demonstrates that the descriptors are accurate, not misleading consumers, and would benefit the public’s health. Specifically, using the descriptors “light,” “mild,” and “low” is prohibited on all tobacco packaging and advertising.10 After filing a lawsuit against the FDA, Black & Mild’s parent company, John Middleton Co LLC (a subsidiary of Altria), was allowed to continue using “mild” in its brand name.34 Although the Federal Trade Commission banned the descriptor “natural” in all cigarette advertisements and packaging,11 it was present on Black & Mild and Dutch Masters brand ads in our sample. The presence of implied risk descriptors raises concerns that the cigar industry may be using selling propositions to ease health concerns and misinform consumers about the cigars’ safety.

Our study also documented the presence of premium branding and sensory descriptors in the sample ads. Of the premium branding descriptors, “fine, finest, premium” and “quality” were more prevalent in cigar ads. Swisher International’s Swisher Sweets brand and Imperial Brand’s Dutch Masters had the highest percentage of premium branding. Several Dutch Masters’ advertisements featured “Experience New Look, Same Taste and Quality,” “Deluxe,” or “Premium Cigarillos” descriptors. In a review of 22 cigar print ads from 2012 to 2013, Shen et al found that the promotion of cigars as “premium” or sophisticated products was the most common unique selling proposition.19 Exposure to descriptors about the cigars’ “premium” characteristics may influence users’ perceptions about their quality.35

Finally, sensory descriptors about taste (eg, smooth, refreshing) were more often featured in Swisher International cigar ads than ads from all other manufacturers. Of note, the descriptors “smooth” and “satisfying” were featured on each Swisher Sweets cigarillo 2-pack wrapper in this sample. Sensory descriptors may convey characteristics of the cigar product and influence consumers’ thoughts about the strength and appeal of a tobacco product.36,37 Our findings complement the growing body of research that suggests that the presence of sensory descriptors on cigar ads may be an industry strategy to influence consumers’ perception of the sensory benefits of the cigar product or users’ experience with it.

Implicit and sensory descriptors were significantly more common in ambiguous flavors, including concept and color flavor names. Cigarette companies have paired descriptors with pack colors to infer misleading claims.10,38,39 Tobacco industry documents show that package color impacts consumers’ perception of tobacco flavor, strength, and harmfulness.40 Swisher International’s Optimo “Silver” cigarillos (Swisher International) features “Natural Leaf,” and Swisher Sweet’s “Coco Blue” cigarillo features “Satisfying” on advertisements. Both silver and blue colors are associated with perceptions of lower tobacco strength and mild flavors. Premium branding descriptors were significantly more common in explicit flavor name cigars. For example, advertisements for Dutch Master’s “Wine” flavored cigarillos feature “Premium Cigarillos,” perhaps conveying that it is a high-end product.19 Consistent with evidence from prior cigarette pack design studies,41 these findings indicate that cigar companies use descriptors and flavor names to miscommunicate about the products’ taste, strength, and harm.

There was good IRR for implied health claims, premium branding, and sensory descriptors. However, just as determining which cigarillos contained a characterizing flavor was an obstacle to enforcing local sales restrictions on flavored tobacco,42 identifying which advertisements include flavored products and enumerating all the different flavors depicted presented similar challenges. Even with the aid of a flavor dictionary for all brands represented in the ads, these challenges remained.

An important strength of our study is its documentation of descriptors on cigar advertisements that may increase product appeal among youth exposed to them in retail settings. Although this content analysis did not assess youth exposure to cigar advertisements, all advertisements were visible at stores near schools. Nearly half of US youth (ages 13–16) visit convenience stores at least weekly.43 The main limitation is the age of the data, although the FDA has not introduced new regulations on cigar advertising since these data were collected in 2016. However, the advertising stimuli do not capture newer brand varieties and flavors. Our study advertisements were restricted stores near schools in California; therefore, generalizability is limited. In addition, because we only examined stores near schools, this study could not test whether the quantity and content of cigar advertising differ at stores near schools versus other stores.

The presence of implied health claims, sensory, and premium branding descriptors on retail cigar ads may indicate the tobacco industry’s strategy to influence youth and other consumers’ perceptions about the health benefits, appeal, and quality of flavored cigar use. Our study findings may support local, state, and federal policies that restrict the sale of flavored cigars. Findings also add to the body of evidence demonstrating a need for the FDA to limit descriptors that communicate reduced health risks from cigar products.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://dbpia.nl.go.kr/ntr.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, grant number 5R01-CA067850 (PI: Henriksen). The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the NIH. We are grateful for expert feedback on the content analysis protocol and paper drafts from Stephen P. Fortmann (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research) and Nina C. Schleicher (Stanford Prevention Research Center), and to Ewald & Wasserman LLC (San Francisco) for in-store photographs and data collection.

Comments