-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Laura Akers, Judy A Andrews, Edward Lichtenstein, Herbert H Severson, Judith S Gordon, Effect of a Responsiveness-Based Support Intervention on Smokeless Tobacco Cessation: The UCare-ChewFree Randomized Clinical Trial, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 22, Issue 3, March 2020, Pages 381–389, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz074

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Partner behaviors and attitudes can motivate or undermine a tobacco user’s cessation efforts. We developed a multimedia intervention, UCare (Understanding-CAring-REspect) for women who wanted their male partner to quit smokeless tobacco (ST), based on perceived partner responsiveness—the empirically based theory that support is best received when the supporter conveys respect, understanding, and caring.

One thousand one hundred three women were randomized to receive either immediate access to the UCare website and printed booklet (Intervention; N = 552), or a Delayed Treatment control (N = 551). We assessed supportive behaviors and attitudes at baseline and 6-week follow-up, and the ST-using partner’s abstinence at 6 weeks and 7.5 months (surrogate report).

For partners of women assigned to Intervention, 7.0% had quit all tobacco at 7.5 months, compared with 6.6% for control (χ2 (1, n = 1088) = .058, p = .810). For partners of women completing the intervention, 12.4% had quit all tobacco at 7.5 months, compared with 6.6% for Delayed Treatment (χ2 (1, n = 753) = 6.775, p = .009). A previously reported change in responsiveness-based behaviors and instrumental behaviors at 6 weeks mediated 7.5-month cessation, and change in responsiveness-based attitudes mediated the change in responsiveness-based behaviors, indirectly increasing cessation.

A responsiveness-based intervention with female partners of male ST users improved supportive attitudes and behaviors, leading to higher cessation rates among tobacco users not actively seeking to quit. The study demonstrates the potential for responsiveness as a basis for effective intervention with supporters. This approach may reach tobacco users who would not directly seek help.

This study demonstrates the value of a responsiveness-based intervention (showing respect, understanding, and caring) in training partners to provide support for a loved one to quit ST. In a randomized clinical trial, 1,103 women married to or living with a ST user were randomized to receive the UCare-ChewFree intervention (website + booklet) or a Delayed Treatment control. Women completing the intervention were more likely to improve their behaviors and attitudes, and change in behaviors and attitudes mediated cessation outcomes for their partners, who had not enrolled in the study and may not have been seeking to quit.

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01885221

Introduction

Intimate partners can promote or undermine their loved one’s tobacco cessation efforts. In the most recent Cochrane review of partner support in smoking cessation,1 the authors note that “support from the spouse is highly predictive of successful smoking cessation,” citing studies as far back as 1971. Partner support may influence quitting through several mechanisms,2 including providing a motivation to initiate quitting (health concerns or the effects of role-modeling on the couple’s children); buffering the stress of withdrawal; counteracting environmental cues to use tobacco; and providing instrumental support such as facilitating access to quitting programs and adjunctive aids. Particular supportive behaviors, such as expressing pleasure at the smoker’s efforts to quit,3,4 have been predictive of cessation. On the other hand, many tobacco users are ambivalent about quitting and react negatively to pressure, which can lead to problematic behaviors becoming even more entrenched.5,6 Negative behaviors (eg, nagging and complaining) have been shown to be predictive of relapse.7

In a 2010 review of social support interventions for smoking cessation, Westmaas and colleagues8 concluded that there is little or no evidence that interventions to promote partner support have been effective. The study points to a common lack of a conceptual or theoretical framework for support. Several frameworks for social support and behavior change present potential mechanisms through which supporters may influence tobacco users (eg, through stress buffering9 or enhancing self-efficacy10 or self-competence11), but these frameworks do not address the potential problems in relationship quality caused by long-term conflicts about one partner’s behavior. Conversely, other frameworks address relationship quality but require the committed participation of both parties (eg, Relationship Enhancement12; Couples Coping Enhancement Training13).

Our research team identified perceived partner responsiveness,14 or Responsiveness Theory,10 as a potentially useful framework for partner support in the tobacco cessation context. As delineated by Reis, Clark, and Holmes,14 “perceived partner responsiveness” is highest when three conditions are met: (1) validation, or believing the partner esteems one’s core personal qualities, including “respect” for one’s decision-making, (2) “understanding,” or feeling a bond of emotional rapport and believing the partner understands one’s concerns, and (3) “caring,” believing the partner will respond supportively to one’s needs and make one feel cared for. In essence, interactions around the issue of tobacco use and cessation should convey respect, understanding, and caring for the tobacco-using partner. Responsiveness Theory thus provides a theoretical framework for asymmetrical supportive relationships, allows for one dyad member to act to improve the relationship for both members within the supportive context, and provides an easily communicated model for understanding why specific supportive behaviors can be classified as positive or negative.

Using the Responsiveness framework, we developed a multimedia program (website + booklet) called “UCare” (Understanding-Caring-Respect), an intervention for women who want a male smokeless tobacco (ST) user to quit. Our rationale was three-fold: Intervening with women to help men allowed us to avoid potential gender complications (males and females may have varying support strategies); we have worked with female supporters of male ST users in the past (R21-CA131461); and we have an effective web-based ST cessation program (ChewFree.com) that we could recommend as a quitting resource.15 This article presents cessation outcomes associated with the UCare pragmatic randomized clinical trial.

In the United States, there are approximately 8.7 million ST users16 (table 2.27A), of which about 95% are males. ST use is associated with oral and other cancers17 and increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular mortality.18,19 ST users’ wives are often highly motivated to encourage them to quit, for both health and aesthetic reasons. During recruitment for the Northwest Smokeless Tobacco Study (1998–1999),20 we observed numerous women attempting to enroll their partner, leading us to conduct a concurrent study (N = 363 couples) of the assessment and value of positive and negative support provided naturally in the course of an ST quit attempt. We found that received positive support and the ratio of positive to negative support predicted abstinence at 6-month follow-up (OR = 1.29 for received positive support, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.03, 1.6121) and received positive support predicted abstinence at 12-month follow-up (OR = 1.43, 95% C.I. = 1.11, 1.8422). Based on these findings, we conducted a feasibility trial in 2009–2011 with 522 women (R21-CA131461). The intervention included an expanded supporter booklet and an adapted version of our empirically validated ChewFree.com ST cessation website15 that included new social support forums for the women. The intervention was well-received and moderately effective, with 6-week cessation rates of 10.9% for Intervention versus 5.1% for Control (p < .05, one-tailed). These studies served as a basis for the use of Responsiveness as a framework for a full-scale pragmatic randomized clinical trial.

Description of the UCare-ChewFree Intervention

Guided by formative interviews to help us operationalize the Responsiveness framework with this population,23 we developed the UCare website and booklet. The core component of the website, “The Basics,” was an instructional program on how to show respect, understanding, and caring in the contexts of planning to quit, quitting, and staying quit, and how to raise the topic of cessation with her partner while setting goals she could attain on her own. Other website features included information on ST addiction and cessation (including facilitated access to the ChewFree.com website), a “notebook” for the women to collect their own personalized information, and social support forums. The printed UCare booklet reinforced the messages in the website and encouraged website use. The UCare intervention is described in greater detail elsewhere.24

Within the randomized trial, those randomized to receive the UCare intervention showed greater change in supportive behaviors and attitudes at 6-week follow-up than did those randomized to a Delayed Treatment control. Change in support was significant for all three support measures: responsiveness behaviors (F(1, 1086) = 15.57, p < .001; partial η2 = 0.014, a “small” effect size per Cohen25); responsiveness attitudes (F(1, 1086) = 80.15, p < .001; partial η2 = 0.069, a “medium” effect); and instrumental behaviors (F (1,1086) = 34.26, p < .001; partial η2 = 0.031, a “small-to-medium” effect).26 Here we report on ST cessation outcomes and examine the association between change in the women’s supportive behaviors and attitudes at 6-week follow-up and the ST user’s tobacco use at 7.5 months post-enrollment. We hypothesized that partners of women randomized to the intervention condition would be more likely to quit than partners of women randomized to control, that intervention adherence (completion of the website Basics or the mailed booklet) would predict cessation, and that change in supportive behaviors and attitudes would mediate the effect of the intervention on cessation. Secondary objectives included the exploration of baseline variables predicting cessation and intervention effects on quit attempts.

Methods

All activities involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Oregon Research Institute. All conditions, relevant measures, and data exclusions are reported.

Study Procedures

Between July 2015 and December 2016, 1,103 women were recruited and enrolled using demographically targeted Facebook advertising.27 Inclusion criteria were: being the wife or female domestic partner of a male current ST user; interested in having him quit using tobacco; willing to provide a phone number, mailing address, and e-mail address; providing informed consent; and both the woman and the ST user being US or Canadian residents age 18 or older, able to read English, and able to access a computer. After online screening, those who were eligible to participate were invited to provide informed consent (online consent, printable for their records), give personal contact information, and complete a baseline survey. Those who met these criteria were randomized to either the UCare intervention or Delayed Treatment Control condition. Those assigned to the UCare Intervention condition were given immediate access to the UCare website, and were mailed the UCare booklet. At 6 weeks and 7.5 months post-enrollment, all participants were sent an e-mail link to complete follow-up assessments. The 7.5-month assessment was used to obtain an estimate of cessation at 6 months post-intervention, assuming a 1.5-month window to complete the intervention, as recommended by the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT) workgroup on abstinence.28 After five automated e-mails prompting participants to complete the assessment, efforts were made to contact them by phone and text message, with the option of completing the assessment online or by phone. Incentives were offered for completing the assessments: $20 for the first, $20 for the second, and a $10 bonus for both. Delayed Treatment participants received website access and the mailed booklet after completing the 7.5-month assessment.

Participants

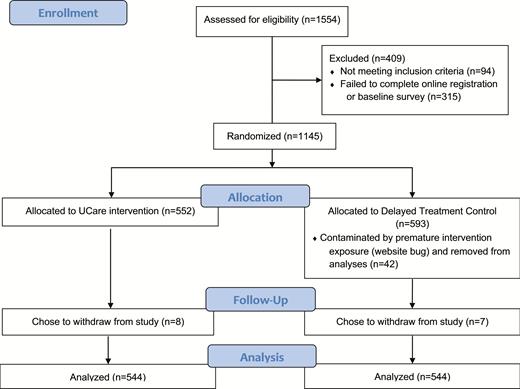

Total enrollment was 1,103 women, of whom 552 were randomized to Intervention and 551 to Delayed Treatment control. An additional seven control participants and eight intervention participants chose to withdraw from the study, leaving 544 per condition. Thus, the baseline sample was 1,103, and the sample for outcome assessment was 1,088. See Figure 1 for a CONSORT flow diagram, displaying the numbers of potential and actual participants at each stage of the study.

Measures

All measures were completed by the participants. The husbands/partners were not asked to complete assessments.

Demographics and Tobacco Use

At baseline, participants provided data on the following: year of birth, highest level of education, race, and Hispanic ethnicity for the participant and her husband/partner; the length of their relationship and whether they were married or in a domestic partnership; her current and past status for smoking and ST use; and his current and past smoking status. At both baseline and in the 7.5-month survey she provided an estimate of his motivation to quit (8-point scale from not motivated to very motivated; rt1t3 = .47, p < .001); and her estimate of his readiness to quit (rt1t3 = .38, p < .001).29 At the 7.5-month assessment, the women were also asked for his current tobacco use and types of tobacco he used. If he had not quit, the 7.5-month assessment included whether he had made a serious quit attempt (able to stay abstinent for 24 hours); if the participant didn’t know, the response was recoded as “no.”

Relationship Quality

The participant’s overall satisfaction with the relationship was assessed with the four-item version of the Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-4).30

Partner Support

Twelve brief measures were created to assess positive and negative behaviors and attitudes for the three responsiveness themes: showing respect, showing understanding, and showing caring. Items for the measures were adapted from many sources, including the Partner Interaction Questionnaire (PIQ-20),31 the Support Provided Measure,32 the Health Care Climate Questionnaire,11 the Davis Interpersonal Reactivity Indexes,33,34 and our own previous research (NIH R21-CA131461). These measures were aggregated into two summary scales: responsiveness behaviors (18 items, Cronbach’s = .81) and responsiveness attitudes (14 items, = .68). We also assessed “instrumental” supportive behaviors (four items, =.77), which were practical activities focusing on facilitating cessation, for example, “Help your partner think of substitutes for snuff or chew.” These measures were administered at baseline and both follow-up assessments. Additional details on partner support scale content, format, and development are available elsewhere.26

Intervention Exposure

Standard web tracking procedures (time-stamped logs of all page visits, etc.) were used to collect data on all participant activity within the UCare website. Participants were informed of this tracking and our planned use of the data in a detailed website Privacy Policy. Booklet use was assessed only at the 6-week follow-up. For the purpose of setting a threshold for intervention adherence,35 we define “Completed Intervention” as either (1) completing the Basics by the relevant assessment point, or (2) reporting that they had read “all of the booklet, once” or “all of the booklet, more than once” at the 6-week follow-up (booklet use was not assessed again after that point). A direct comparison of those who only read the booklet with those who only completed the website “Basics” suggested only minimal differences in support outcomes; both were effective at changing supportive behaviors and attitudes.

Statistical Analyses

Tobacco Cessation

We report cessation rates for our primary tobacco outcome (quit all tobacco) at two endpoints (6 weeks, 7.5 months), defined as reporting that the ST user had quit all tobacco at the relevant endpoint. We compare outcomes for all participants randomized to intervention versus control (intent to treat), as well as for the subset who completed the intervention, and we report outcomes both for responders only (complete case) and for the full sample estimating missing data. We used the Expectation-Maximization algorithm to estimate missing data for the 6-week and 7.5-month measures of cessation within SPSS, version 24. We also report quit rates at 7.5 months for the subsample of those who had reported use at 6 weeks (N = 499), because we expected fairly high rates of “delayed cessation” given that almost 40% of the 170 women who completed “The Basics” did so after the 6-week follow-up.22

Mediation Analyses

To fulfill the criteria for mediation the intervention must be associated with cessation as well as the hypothesized mediators: short-term change in the three support variables (responsiveness behaviors, responsiveness attitudes, and instrumental behaviors). To fulfill the temporal criteria of mediation, short-term change in the three support variables from baseline to 6 weeks was measured prior to the long-term (7.5-month) cessation outcome. To assess cessation, we used 7.5-month abstinence of all tobacco, comparing the subsample who had completed the intervention (completed “The Basics” or read the manual) with the control group. We used Mplus, version 7, with maximum likelihood estimates of missing data, to assess the effect of condition on cessation through changes in support (responsiveness behaviors, responsiveness attitudes, and instrumental behaviors). The indirect effect was estimated using non-parametric tests, using bootstrap estimates of standard errors.36,37

Baseline Predictors of Cessation

We examined baseline predictors of cessation estimating missing data using the Expectation-Maximization algorithm. We used logistic regression, controlling for receipt of the intervention (completing The Basics or reading the booklet, vs. control). Baseline predictors included all of the demographics, tobacco use variables, and relationship quality variables, and interactions of these variables with intervention condition. We used backwards elimination, first eliminating nonsignificant interactions followed by those nonsignificant main effects not included in the interactions. Significant interactions with intervention condition were decomposed using the techniques presented in Aiken and West.38

Quit Attempts

For participants who did not report cessation at either 6 weeks or 7.5 months, we examined quit attempts (“able to stay completely off all tobacco products for at least 24 hours”) combining reports at 6-week and 7.5-month follow-up into a variable “ever quit attempt” and using chi-square analyses to compare groups. Quit attempts for the Delayed Treatment control were compared with both the full group randomized to intervention and for the subset who completed the intervention, estimating missing data.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participant Characteristics

For the 1,103 female participants, the mean age was 43.1 years (SD 9.4). The sample was 95.6% white, 96.1% non-Hispanic, and 87.9% with some college education. Ever-use of tobacco was 26.1% (2.0% current smoker, 23.5% former smoker, 0.5% current ST user, and 0.4% former ST user). No differences between conditions were observed at baseline in the characteristics of participants, including demographics, tobacco use, relationship quality, and the support measures.

ST User Characteristics

For the 1,103 male ST-using partners, the mean age was 44.7 years (SD 9.4). The sample was 96.2% white, 98.4% non-Hispanic, and 68.0% with some college education; 4.2% were current smokers and 39.0% were former smokers. The ST users were demographically similar to the women, except for gender, education (women had more education, p < .001), and tobacco use history (only 26.5% of the women had ever used tobacco, whereas by definition all of the men were current tobacco users).

We compared the ST users’ characteristics (as reported by the female participants) from this study to ST users seeking to quit in our previous online cessation study (ChewFree.com).15 The ChewFree ST users’ self-reported readiness to quit was 8.12 on the “contemplation ladder” (for which scores range from 0 to 10); the UCare participants rated their partner’s readiness at 4.92 (p < .001). The UCare participants’ partners were also older (mean age 45 vs. 37, p < .001) and less well educated (68% vs. 81% completing some college, p < .001) than the ChewFree participants.

Relationship Characteristics

For their relationship status, 93.4% were married (vs. living with partner). The mean relationship length was 15.6 years (SD 10.2). Per the women’s rating of relationship satisfaction, 37.9% of the couples exceeded the CSI-4’s “distress” threshold.

Attrition at 7.5-Month Follow-up

Participants randomized to Delayed Treatment were more likely to complete the 7.5-month assessment (62.1% vs. 49.4%; χ2 (1, N = 1088) = 17.742, p < .001) and more likely to complete both assessments (55.9% vs. 43.0%, χ2 (1, N = 1088) = 18.017, p < .001). Baseline variables associated with higher levels of completing the 7.5-month assessment were participant age (those completing were younger, mean age = 42.44 vs. 43.94, t = 2.558, p = .011), partner age (those completing were partnered with younger men, mean age = 45.75 vs. 43.82, t = 3.355, p = .001) relationship length (those completing had been in this relationship for a shorter length of time 14.55 years vs. 16.83 years, t = 3.690, p < .001), and participant education (those completing had more education (M = 4.21 vs. 3.90, t = −3.954, p < .001). Participant age and partner age were highly correlated (r = .89, p < .001), and both were highly correlated with relationship length (r = .66 for the participant and .68 for the partner, p < .001).

Outcomes

Tobacco Cessation

Table 1 presents the primary cessation outcomes. When comparing cessation outcomes for partners of all women randomized to intervention versus control (eg, 7.0% vs. 6.6% quitting all tobacco at 7.5 months; χ2 (1, N = 1088) = .058, p = .810), the differences were not significant. For the women who completed the intervention, partner cessation of all tobacco products was higher at both 6 weeks and 7.5 months than for the control group (at 6 weeks, χ2 (1, N = 712 = 9.247, p = .004; at 7.5 months, χ2 (1, N = 753) = 6.775, p = .009. For the analysis using data from responders only, 6-week cessation for all tobacco products was greater for those who completed the intervention than for the control (χ2 (1, N = 503 = 3.653, p = .047).

| . | Responders only (complete case) . | All participants (imputed) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint . | Delayed Tx control (6 wk, N = 347; 7.5 mo, N = 336; both N = 299) . | Assigned to intervention (6 wk N = 290; 7.5 mo, N = 268; both N = 230) . | Completed intervention (6 wk, N = 156; 7.5 mo, N = 171; both N = 166) . | Delayed Tx control (N = 544) . | Assigned to intervention (N = 544) . | Completed intervention (6 wk, N = 168; 7.5 mo/both N = 209) . |

| 6 wk | 4.6% | 6.6% | 9.0%* | 2.9% | 3.5% | 8.3%** |

| 7.5 mo | 10.7% | 13.1% | 13.5% | 6.6% | 7.0% | 12.4%** |

| . | Responders only (complete case) . | All participants (imputed) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint . | Delayed Tx control (6 wk, N = 347; 7.5 mo, N = 336; both N = 299) . | Assigned to intervention (6 wk N = 290; 7.5 mo, N = 268; both N = 230) . | Completed intervention (6 wk, N = 156; 7.5 mo, N = 171; both N = 166) . | Delayed Tx control (N = 544) . | Assigned to intervention (N = 544) . | Completed intervention (6 wk, N = 168; 7.5 mo/both N = 209) . |

| 6 wk | 4.6% | 6.6% | 9.0%* | 2.9% | 3.5% | 8.3%** |

| 7.5 mo | 10.7% | 13.1% | 13.5% | 6.6% | 7.0% | 12.4%** |

“Completed Intervention” is defined as either completing “The Basics” in the UCare website by the relevant assessment point, or reporting completion of the booklet at the 6-week follow-up.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

| . | Responders only (complete case) . | All participants (imputed) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint . | Delayed Tx control (6 wk, N = 347; 7.5 mo, N = 336; both N = 299) . | Assigned to intervention (6 wk N = 290; 7.5 mo, N = 268; both N = 230) . | Completed intervention (6 wk, N = 156; 7.5 mo, N = 171; both N = 166) . | Delayed Tx control (N = 544) . | Assigned to intervention (N = 544) . | Completed intervention (6 wk, N = 168; 7.5 mo/both N = 209) . |

| 6 wk | 4.6% | 6.6% | 9.0%* | 2.9% | 3.5% | 8.3%** |

| 7.5 mo | 10.7% | 13.1% | 13.5% | 6.6% | 7.0% | 12.4%** |

| . | Responders only (complete case) . | All participants (imputed) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint . | Delayed Tx control (6 wk, N = 347; 7.5 mo, N = 336; both N = 299) . | Assigned to intervention (6 wk N = 290; 7.5 mo, N = 268; both N = 230) . | Completed intervention (6 wk, N = 156; 7.5 mo, N = 171; both N = 166) . | Delayed Tx control (N = 544) . | Assigned to intervention (N = 544) . | Completed intervention (6 wk, N = 168; 7.5 mo/both N = 209) . |

| 6 wk | 4.6% | 6.6% | 9.0%* | 2.9% | 3.5% | 8.3%** |

| 7.5 mo | 10.7% | 13.1% | 13.5% | 6.6% | 7.0% | 12.4%** |

“Completed Intervention” is defined as either completing “The Basics” in the UCare website by the relevant assessment point, or reporting completion of the booklet at the 6-week follow-up.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

For those who had reported use at 6 weeks, based on estimating missing data, 5.7% of ST users whose partners were assigned to the intervention had quit at 7.5 months vs. 4.9% for control (χ2 (1, N = 1053) = .326, p = .332). Partners of women who completed the intervention (N = 194) quit all tobacco at higher rates than the control group (N = 528; 9.8% vs. 4.9%, χ2 (1, N = 722) = 5.796, p = .016).

Mediation Analyses

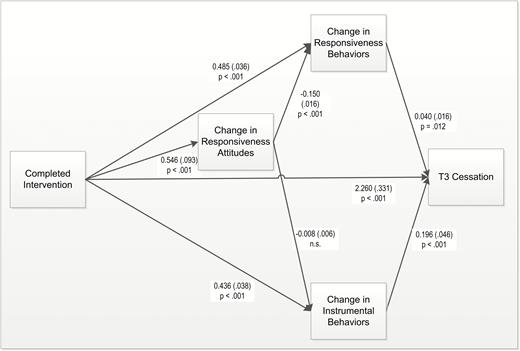

The effect of the intervention condition was indirectly and significantly related to cessation at 7.5 months through both change in responsiveness behaviors, 0.061 (.029), p = .03, and change in instrumental behaviors, 0.110 (.037), p = .003; but the indirect effect through change in responsiveness attitudes was not significant, −0.010 (.022), p = .641. This model fit the data well (root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .102, 90% CI = .084, .120; comparative fit index [CFI] = .879). The nonsignificant indirect effect through change in responsiveness attitudes led us to test a second model, shown in Figure 2. Because the intervention condition significantly predicted change in attitudes, and because change in responsiveness attitudes was correlated with change in responsiveness behaviors (r = .271), we hypothesized that change in responsiveness attitudes would mediate the effect of the intervention on change in responsiveness behaviors and ultimately on cessation. We also tested the hypothesis that change in instrumental behaviors was mediated by change in responsiveness attitudes. This model also fit the data well (RMSEA = .112; 90% CI = .094, .131; CFI = .926). As shown in Figure 2, our hypothesis was supported. The indirect effects through changes in responsiveness attitudes to changes in both responsiveness behaviors and instrumental behaviors were both significant. Further, the indirect effect of condition on cessation through both responsiveness attitudes and responsiveness behaviors was significant, suggesting that improving responsiveness attitudes leads to improvements in responsiveness behaviors, which ultimately leads to cessation. Of note, the indirect effect through changes in instrumental behaviors was not significant.

Model showing the effect of completing the intervention on 7.5-month cessation through change in instrumental behaviors and change in responsiveness (RUC) behaviors. The effect of condition on change in responsiveness behaviors is mediated by change in responsiveness attitudes. Completed Intervention = completed the website “Basics” or read the whole booklet. To simplify the figure, the regression of T2 attitudes/behaviors on T1 attitudes/behaviors to assess change and indirect paths are not shown. Indirect paths are: (1) from condition to cessation through change in responsiveness behaviors, .041 (.019), p = .03; (2) from condition to cessation through change in instrumental behaviors, .107 (.031), p < .001; (3) from condition to cessation through both change in responsive attitudes and change in responsiveness behaviors, .014 (.006), p ≤ .02; (4) from condition to cessation from both change in responsiveness attitudes and change in instrumental behaviors .003 (.003), p = .258.

Baseline Predictors of Cessation

The final model fit the data well (χ2 (6, N = 753) = 33.96; p < .001), explaining 10% of the variance in cessation (Nagelkerke R square). As shown in Table 2, the supporter’s rating of the ST user’s motivation to quit predicted cessation across conditions, and interactions of intervention condition with both supporter’s education and the supporter’s rating of relationship remained in the model. These interactions were decomposed by centering at 1 SD above and below the mean, per Aiken and West.38 The decomposition of the interaction with education indicated the intervention was not effective for those with lower levels of education (OR = .73; 95% CI = .30, 1.78; p =.50), and as shown in Table 2, was less effective in the intervention than in the control condition for those with average levels of education. However, the intervention was more effective than the control condition for those with higher levels of education (OR = 4.93; 95% CI = 2.25; 10.75 = p < .001). In addition, completing the intervention was effective only for those with poorer relationships, as measured by the CSI-4 (OR = 3.29; 95% CI = 1.47, 7.42; p = .002), but not for those with average or higher than average CSI-4 scores (OR = 1.09; 95% CI = .47, 2.53; p = .830).

| Measure . | β . | Odds ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | Significance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition (completed intervention vs. control) | .642 | 1.90 | 1.04, 3.48 | p = .038 |

| Supporter’s rating of ST user’s motivation to quit | .301 | 1.35 | 1.15, 1.59 | p < .001 |

| Supporter’s education | −.342 | 0.71 | 0.54, 0.94 | p = .017 |

| Supporter rating of relationship quality (CSI-4) | .045 | 1.05 | 0.96, 1,15 | p = .331 |

| Condition × supporter’s education | .749 | 2.11 | 1.34, 3.33 | p = .001 |

| Condition × supporter rating of relationship quality (CSI-4) | −.131 | 0.88 | 0.77, 1.00 | p = .053 |

| Measure . | β . | Odds ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | Significance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition (completed intervention vs. control) | .642 | 1.90 | 1.04, 3.48 | p = .038 |

| Supporter’s rating of ST user’s motivation to quit | .301 | 1.35 | 1.15, 1.59 | p < .001 |

| Supporter’s education | −.342 | 0.71 | 0.54, 0.94 | p = .017 |

| Supporter rating of relationship quality (CSI-4) | .045 | 1.05 | 0.96, 1,15 | p = .331 |

| Condition × supporter’s education | .749 | 2.11 | 1.34, 3.33 | p = .001 |

| Condition × supporter rating of relationship quality (CSI-4) | −.131 | 0.88 | 0.77, 1.00 | p = .053 |

All continuous variables were centered at the mean.

| Measure . | β . | Odds ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | Significance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition (completed intervention vs. control) | .642 | 1.90 | 1.04, 3.48 | p = .038 |

| Supporter’s rating of ST user’s motivation to quit | .301 | 1.35 | 1.15, 1.59 | p < .001 |

| Supporter’s education | −.342 | 0.71 | 0.54, 0.94 | p = .017 |

| Supporter rating of relationship quality (CSI-4) | .045 | 1.05 | 0.96, 1,15 | p = .331 |

| Condition × supporter’s education | .749 | 2.11 | 1.34, 3.33 | p = .001 |

| Condition × supporter rating of relationship quality (CSI-4) | −.131 | 0.88 | 0.77, 1.00 | p = .053 |

| Measure . | β . | Odds ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | Significance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition (completed intervention vs. control) | .642 | 1.90 | 1.04, 3.48 | p = .038 |

| Supporter’s rating of ST user’s motivation to quit | .301 | 1.35 | 1.15, 1.59 | p < .001 |

| Supporter’s education | −.342 | 0.71 | 0.54, 0.94 | p = .017 |

| Supporter rating of relationship quality (CSI-4) | .045 | 1.05 | 0.96, 1,15 | p = .331 |

| Condition × supporter’s education | .749 | 2.11 | 1.34, 3.33 | p = .001 |

| Condition × supporter rating of relationship quality (CSI-4) | −.131 | 0.88 | 0.77, 1.00 | p = .053 |

All continuous variables were centered at the mean.

Secondary Outcomes

Quit Attempts

The rates for making a 24-hr quit attempt post-enrollment were 16.7% for the Delayed Treatment control, 16.8% for the Intervention, and 26.8% for the subset of those assigned to the Intervention who completed the intervention (completed the Basics and/or read the booklet). The chi-square comparison between the full intervention group and Delayed Treatment was not significant (χ2 (1, N = 1014) = .001, p =.522), but the comparison between those who completed the intervention and Delayed Treatment was significant (χ2 (1, N = 691) = 8.682, p = .003).

Discussion

Use of the UCare-ChewFree intervention by wives/partners of ST users appears to be an effective method of encouraging ST cessation among a population who were not themselves seeking help to quit. The observed quit rates, although lower than in many cessation trials, should be considered in that context. The ST-using partners of the women recruited for this study differed in several key ways from the participants in a study recruiting ST users directly—in this study, the ST users were older and less well educated. Recruiting supporters has allowed us to access a different population than those seeking to quit on their own.

The higher rate of quit attempts for men whose supporters completed the intervention is also encouraging. Previous research has shown that for smoking, making more quit attempts is associated with higher rates of eventual cessation.39

As previously reported, use of the intervention produced an increase in three categories of support (responsiveness-based behaviors, responsiveness-based attitudes, and instrumental behaviors). The present study showed that these increases in support behaviors and attitudes led to higher cessation rates. Further, the responsiveness-based behaviors and attitudes contributed to cessation independently from instrumental behaviors, supporting the framework of Responsiveness Theory. The finding that responsiveness-based attitudes mediated the change in responsiveness-based behaviors is consistent with the tenets of the Theory of Planned Behavior.40 Within this theoretical framework, attitudes precede and predict behavior.

The UCare-ChewFree intervention was designed to overcome shortcomings in previous research designed to leverage support to help someone quit tobacco. Ten randomized clinical trials have evaluated interventions designed to increase the support provided by a partner in a smoker’s existing social network, to encourage the smoker to quit.41–50 However, each of these interventions had shortcomings that were addressed by the UCare program. All but one (Patten et al.49) involved training a supporter of a smoker who was already trying to quit, which neglects the opportunity to motivate and encourage the many smokers who are not already engaged with the cessation process. UCare enrolled only the supporters, whose partners varied in their readiness to quit. None of the studies related a measured change in supportive behaviors and attitudes to cessation. With UCare, we showed that change in supportive attitudes and behaviors mediated the effect of the intervention on cessation outcomes. Few studies42,48 explicitly addressed communication skills and what Park and colleagues1 referred to as “the quality of the partner interaction.” The UCare intervention explicitly focused on communication skills and relationship quality. All but one of the previous studies46 required the supporter to participate in scheduled in-person or phone training (increasing the cost and limiting the reach of the program). The UCare program, by contrast, could be accessed at the user’s convenience through an interactive website and printed booklet, thus creating a scalable intervention.

Implications for Practice

This study contributes to the growing body of research on intervening with a supporter as a way to influence health behavior in a person who is not the target of intervention. The study supports the specific use of Responsiveness Theory as a framework for intervention in a specific circumstance: between peers with an asymmetry of information and burden, supporting change in a relatively finite time frame. Responsiveness may also be useful in a broader variety of behavior-change contexts, whenever showing respect, understanding, and caring can facilitate the interactions between a supporter or caregiver and a care recipient, such as coping with chronic illness, managing weight, or making the transition from adolescence to adulthood or from independence to elder care.

Limitations

As with many online studies, many participants failed to use the intervention, and many did not complete the follow-up assessments. The high attrition related to not completing assessments resulted in a relatively large amount of data that was estimated. There is much debate in the missing data literature on the ideal amount that can be estimated, in contrast to using other techniques such as listwise deletion.51 Both affect the validity of the data through the impact on the size of the residual and other factors. Thus, we recommend that findings are replicated. We are continuing to explore creative methods for maintaining participants’ engagement with the research, beyond the regular schedule of reminder e-mails used in this study to improve adherence and decrease attrition. Other strategies could include text messaging for reminders and perhaps sending a regular study newsletter that might help impress upon participants the importance of participating in a research trial.

We based our study design on a model of intervention and cessation outcomes used in tobacco cessation studies. However, unlike people signing up for an intervention because they are seeking to quit, the women in this study were less likely to begin or complete the intervention promptly. Almost 40% of those who completed the intervention did so after the 6-week follow-up. Further, the intervention advised them to wait to talk to their partner about quitting until a good opportunity presented itself. Thus, many of the men who quit did so after the 6-week assessment. Future studies with supporters should include more effective encouragement to complete the intervention promptly, or else assessment timing should be linked to actual intervention completion rather than their enrollment date.

Another limitation for this study was the necessity of relying on surrogate report of cessation, as well as quit attempts and perception of readiness to quit. The reports of perceived readiness and motivation to quit may be especially unreliable, as surrogate report of others’ feelings is likely less accurate than their reports of observed behaviors. Enrolling the men would be necessary to obtain more accurate measures of these variables. This would have been a substantial barrier to meeting our recruitment goals, as many ST users may not be interested in quitting. The proposed research sought to change the behavior of ST users across the full range of readiness to quit, including those uninterested in seeking cessation assistance.

Use of the booklet was self-reported at 6-week follow-up. Self-report of reading materials is the standard way of assessing whether information has been received. The UCare intervention is focused on cognitive reframing (encouraging participants to think about support differently), rather than knowledge acquisition, and as such is not amenable to knowledge testing. Rather, adoption of the new cognitive framework is assessed in the Responsiveness support measures. In addition, the booklet content is intended to be equivalent to the website content, further limiting our ability to test for booklet exposure as distinct from website exposure. In future studies, we plan to assess booklet use at all follow-up assessment points.

Finally, our final assessment point was 7.5 months rather than 12 months post-enrollment. Collection of 12-month cessation outcomes might have provided support for longer-term intervention effectiveness.

Conclusions

Perceived partner responsiveness shows promise as a framework for promoting dyadic social support. Women who used the UCare-ChewFree intervention were better able to change their behaviors and attitudes to facilitate their husband/partner’s ST cessation. ST users whose partners completed the UCare program were more likely to quit. While the observed intervention effects are modest, the program is scalable, and the UCare approach may reach ST users who would not directly seek help.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse in the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01DA033422).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Melissa Peterson for data analysis, InterVision Media and Zoe Brady for their help in developing the UCare intervention, and Katie Clawson for assistance with the UCare booklet and manuscript preparation. We appreciate the helpful feedback provided by Christi Patten throughout the study.

Comments