-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gina R Kruse, Vaibhav Thawal, Himanshu A Gupte, Leni Chaudhuri, Sultan Pradhan, Sydney Howard, Nancy A Rigotti, Tobacco Use and Subsequent Cessation Among Hospitalized Patients in Mumbai, India: A Longitudinal Study, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 22, Issue 3, March 2020, Pages 363–370, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz026

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hospitalization is an important setting to address tobacco use. Little is known about post-discharge cessation and treatment use in low- and middle-income countries. Our objective was to assess tobacco use after hospital discharge among patients in Mumbai, India.

Longitudinal observational study of inpatients (≥15 years) admitted at one hospital from November 2015 to October 2016. Patients reporting current tobacco use were surveyed by telephone after discharge.

Of 2894 inpatients approached, 2776 participated and 15.7% (N = 437) reported current tobacco use, including 5.3% (N = 147) smokers, 9.1% (N = 252) smokeless tobacco (SLT) users, and 1.4% (N = 38) dual users. Excluding dual users, SLT users, compared to smokers, were less likely to report a plan to quit after discharge (42.6% vs. 54.2%, p = .04), a past-year quit attempt (38.1% vs. 52.7%, p = .004), to agree that tobacco has harmed them (57.9% vs. 70.3%, p = .02) or caused their hospitalization (43.4% vs. 61.4%, p < .001). After discharge, 77.6% of smokers and 78.6% of SLT users reported trying to quit (p = .81). Six-month continuous abstinence after discharge was reported by 27.2% of smokers and 24.6% of SLT users (p = .56). Nearly all relapses to tobacco use after discharge occurred within 30 days and did not differ by tobacco type (log-rank p = .08). Use of evidence-based cessation treatment was reported by 6.5% (N = 26).

Three-quarters of tobacco users in a Mumbai hospital attempted to quit after discharge. One-quarter reported continuous tobacco abstinence for 6 months despite little use of cessation treatment. Increasing post-discharge cessation support could further increase cessation rates and improve patient outcomes.

No prior study has measured the patterns of tobacco use and cessation among hospitalized tobacco users in India. Three-quarters of tobacco users admitted to a hospital in Mumbai attempted to quit after discharge, and one-quarter remained tobacco-free for 6 months, indicating that hospitalization may be an opportune time to offer a cessation intervention. Although smokers and SLT users differed in socioeconomic status, perceived risks and interest in quitting, they did not differ in their ability to stay abstinent after hospital discharge.

Introduction

Hospitalization is a key site in the health care system for delivering tobacco cessation treatment.1 By itself, a hospital admission promotes subsequent smoking cessation because a serious illness, especially if tobacco-related, increases smokers’ motivation to quit. A systematic review showed that starting a cessation intervention in the hospital increases post-discharge cessation rates by 37%.1 However, only 1 of the 50 trials included in that review was conducted in a low- or middle-income country (LMICs) and no trials examined smokeless tobacco (SLT) cessation. Little is known about the natural history or pattern of tobacco use among hospitalized smokers in LMICs. Whether hospitalization offers a similar opportunity for promoting cessation in LMICs such as India is not clear.

Providing interventions to hospital patients might be a valuable cessation strategy in India, an LMIC with an enormous burden of tobacco use and tobacco-related disease. India had an estimated 1 million tobacco-attributable deaths in 20102 and the world’s highest rate of head and neck cancer.3–5 India faces unique challenges for controlling this tobacco epidemic. A diverse array of smoked and SLT products are used by 267 million current tobacco users. Among men more than 15 years of age, 42% use tobacco (19% smoke and 30% use SLT products).6,7 Among women more than 15 years of age, 13% use SLT and 2% smoke.6,7 The health threat of SLT in India and elsewhere in South Asia is unique in that products are cheaper, not subject to public use bans, more socially acceptable, and have widely varying levels of nicotine.8 Furthermore, although smoking prevalence is declining in India and neighboring countries, SLT use is growing.9 This is concerning given the health effects of SLT that include causing cancer of the mouth, esophagus, and pancreas; SLT use may also be associated with cardiovascular disease.10,11 An additional challenge is that the evidence base of effective cessation treatments is more limited for SLT users than for cigarette smokers12 and previous trials of hospital-based interventions have targeted only cigarette smokers.1

To the best of our knowledge, neither the pattern of tobacco use among hospital patients nor the natural history of cessation after discharge has previously been described in India. This information could inform the development of an intervention tailored to this setting. This study aims to provide this information by describing patterns of tobacco use among hospitalized tobacco users in India, comparing SLT users with smokers, and by measuring the natural history of quit attempts and cessation after hospital discharge.

Methods

Study Sample

This longitudinal observational study was conducted at the Prince Aly Khan Hospital (PAKH) in Mumbai. PAKH is a private, 137-bed general hospital recognized as a Center for Excellence in cardiac and cancer care. From November 2015 to October 2016 all patients admitted to PAKH were identified from the daily admission report of the hospital’s electronic information system. The study was conducted during a time period when there was no systematic tobacco cessation service active in the hospital. The goal of the study was to understand the natural history of cessation among hospitalized tobacco users. Three research staff approached patients admitted to standard care units, excluding intensive care or day surgery units, to screen for eligibility. If a patient was unavailable, up to three attempts were made per day to recruit them until time of discharge. The research staff who conducted the surveys included one trained social worker and two staff with Bachelor of Science and basic training in clinical trials data collection. To standardize data collection methods across the three interviewers a survey manual was developed and interviewers were trained for 3 days on the use of the manual and survey data collection and for 3 days on the use of the tablet based data collection app. Following a series of at least 10 pilot interviews, the interviewers were observed individually for 10 interviews by a fourth study staff to ensure fidelity to the manualized data collection procedures. Interviewers were later observed and given feedback periodically throughout the study. Inclusion criteria were Indian national or resident, age more than 15 years, length of stay 24 hours or longer and speaker of English, Hindi, or Marathi. Patients were excluded if their illness or cognitive impairment limited the ability to consent or communicate. Informed consent was obtained from patients aged 18 years and older and from parents or guardians for minor patients aged 15–17 years together with minor’s assent.

Our target sample size was based on practical considerations. We had resources to conduct the survey over a 12-month period after which implementation of a tobacco cessation treatment service would begin. The PAKH has about 7300 admissions per year (20 admissions/day × 365 days). If roughly two-thirds are eligible and half of those participate, we anticipated a survey sample size of 2500 subjects, and a conservative response distribution of 50% with 95% confidence intervals yields a 3% margin of error on baseline variables.

Data Collection

Survey Methods

In-Person Baseline Survey

Subjects were asked to complete an in-person survey by a trained research staff member who used an electronic-handheld tablet to record responses. Current tobacco use was assessed using the tobacco use questions from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey.13 Surveys also collected self-reported socioeconomic measures and screened for mood and anxiety disorders with the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4).14 Subjects were asked about nicotine dependence,15,16 quit plans,17 self-efficacy,18 motivation,18 and health beliefs.19 Subjects who reported current daily or less than daily tobacco use were asked to provide a telephone number where they could be reached after discharge and a telephone number for a family member who could serve as a proxy to report on the participants’ tobacco use. Medical diagnoses were obtained from medical records.

Telephone Follow-Up Surveys

Subjects who reported current tobacco use at the baseline survey were contacted for follow-up telephone surveys at 7 days, 30 days, 3 months, and 6 months after hospital discharge. Follow-up surveys collected self- or proxy-reported continuous abstinence, quit attempt, use of tobacco cessation treatments, and time of first tobacco use after discharge. Proxy-reported outcomes were based on responses by the family member named by the participant at the baseline survey. The family member serving as a proxy was asked about the participant’s tobacco use after discharge if the patient could not be reached for self-reported tobacco use.

Statistical Analysis

We compared demographic, socioeconomic, tobacco, use and health characteristics by baseline self-reported tobacco use status and tobacco type using Fisher’s exact tests, chi-square tests, and t tests. Using follow-up surveys, we measured the proportion of tobacco users who self-reported or proxy-reported a quit attempt and continuous abstinence after hospital discharge at each timepoint. Proxy report was used only when self-report was unavailable at that timepoint. Making a quit attempt was defined as responding “Yes” to the item “Since leaving the hospital did you try to stop smoking/using smokeless tobacco?” If this item was missing, individuals were considered to have made a quit attempt if they reported one or more days of abstinence since leaving the hospital. If self-reported abstinence at a subsequent timepoint contradicted proxy-report, the abstinence measure was edited to be consistent with self-report. Patients who were lost to follow-up were considered tobacco users in analyses. Using logistic regression models, we examined adjusted odds of 6-month continuous abstinence by tobacco type. We adjusted for age, gender, and independent variables associated with abstinence in unadjusted models at p < .10. We calculated variance inflation factors by adding model variables to a generalized linear regression model as a measure of collinearity. We used Kaplan–Meier analysis to compare days of abstinence by tobacco type with the log-rank test. Subjects not reporting return to tobacco use were censored at time of last contact. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the PAKH Medical Ethics Committee, the Indian Council on Medical Research and the Partners Healthcare Systems Institutional Review Board.

Results

From November 2015 to October 2016 all 7889 admitted patients were screened for eligibility. Of those screened, 5038 were eligible and 2894 were approached by research staff to be recruited for the study. Patients who were not recruited were either unavailable despite multiple attempts or deemed unable to participate following an inpatient surgery or intervention. Of those approached, 2776 (95.9%) agreed to participate, representing 35.2% of all hospitalized patients and 55.1% of eligible patients. Reasons for refusal among the 4.1% were not collected. Among 2776 participants, 437 (15.7%) reported current daily or less than daily tobacco use, 637 (22.9%) reported former tobacco use and 1702 (61.3%) reported no prior tobacco use (Supplementary Table 1). Among 637 former tobacco users, the median time since quitting was 12.0 months (interquartile range: 3.0–72.1 months) and 4.4% (N = 28) quit in the past month prior to hospitalization. The most commonly reported reasons for quitting prior to hospitalization include current health problems, concern for future health, pressure from family, and advice from a doctor (Supplementary Table 2). Current tobacco users included SLT users (9.1%, N = 252), smokers (5.3%, N = 147), and dual users of smoked and smokeless products (1.4%, N = 38). Supplementary Table 3 compares the characteristics of current smokers and current SLT users.

In terms of tobacco type, among current smokers the mean number of tobacco products used was 1.1 (SD = 0.4). SLT users used a mean of 1.3 products (SD = 0.7) and dual users reported using a mean 2.6 products (SD = 1.2). Among smokers the most commonly smoked products were cigarettes (82.3%) followed by bidis (27.9%) and hookah (2.0%). Among SLT users the most commonly used products were betel quid with tobacco (30.6%), tobacco with slaked lime (27.0%), mishri with tobacco (23.0%), and gutkha (13.1%). Among dual users the most commonly used products were cigarettes (79.0 %), betel quid with tobacco (50.0%), bidis (34.2%) and gutkha (29.0%).

SLT users, compared to smokers, were younger, more likely to be female, less educated, and less likely to be employed. Admission diagnosis did not differ by tobacco type with 20.6% of tobacco users admitted for tobacco-related cancers, 8.9% admitted for other cancers, and 11.0% admitted for cardiovascular disease. Depressive symptoms were reported by 21.1% and anxiety symptoms were reported by 19.9% with no difference by tobacco type. In terms of tobacco use SLT users, compared to smokers, more often reported daily use, less often reported being asked about tobacco by doctors, making a past year quit attempt or planning to quit after discharge. SLT users and smokers did not differ in motivation to quit, confidence, importance of quitting, or prior use of cessation treatments. Nearly all tobacco users agreed that smoking and SLT cause serious illness. Fewer agreed that smoking causes heart attack or stroke than cancer. Perceived harms of smoking were lower among SLT users compared to smokers.

Among smokers, we also compared cigarette smokers (N = 126) with bidi users (N = 29). Compared to cigarette users, bidi users were older (55.4 vs. 45.1 years, p = .004), less educated (20.6% with no formal school or illiterate vs. 7.2%, p < .001), and were more often not working or unemployed (37.9% vs. 15.9%, p = .006). They did not differ by admitting diagnosis, tobacco use characteristics, or health beliefs.

Tobacco users were followed for 6 months after discharge ending May 2017. We excluded dual users (N = 38) from post-discharge outcome analysis because of small numbers. We analyzed the remaining 399 current tobacco users (147 smokers and 252 SLT users). Of these, 375 (94.0%) completed one or more follow-up assessment(s) by self-report or proxy-report. This includes 69 (17.3%) with one follow-up, 109 (27.3%) with two follow-up contacts, 130 (32.6%) with three follow-up contacts, and 67 (16.8%) with all four follow-ups completed. Among smokers and SLT users, 312 (78.2%) reported having tried to quit after discharge and 102 (25.6%) reported continuous abstinence at 6 months post-discharge (Table 1). There were no differences in quit attempts or abstinence by past quit attempts, beliefs that smoking or SLT cause specific conditions or that tobacco has harmed the participant’s health. Other differences are shown in Table 1. Six-month continuous abstinence outcomes were based on proxy-report for 34 (8.5%). In nine of these cases proxy-report contradicted self-report at an earlier follow-up and outcomes were edited to reflect self-report. There were no differences in attempting to quit or succeeding in staying quit by demographic or socioeconomic measures, tobacco use types, daily use, nicotine dependence, past quit attempts, intentions to quit, or treatment use. Those who attempted to quit did differ by admission diagnosis, being more likely to be admitted for cancer, and to report more anxiety symptoms. Those who succeeded in their attempt, compared to those who relapsed, differed by admission diagnosis, being more likely to be admitted for tobacco-related cancer and less likely for cardiovascular disease or other diagnosis. Those who quit also reported greater importance of quitting, confidence and motivation to quit, and they more often agreed that tobacco causes serious illness and that tobacco caused their hospitalization. The most commonly reported reasons for quitting after hospitalization included current health problems, concern for future health, pressure from family, and advice from a doctor (Supplementary Table 2).

Characteristics of Smokers (N = 147) and Smokeless Tobacco Users (N = 252) by Post-Discharge Quit Attempta

| . | . | No attempt N = 87 . | p Valueb . | Quit attemptc N = 312 . | . | p Valueb . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | Relapse N = 210 | 6-month CA N = 102 | ||||

| Sociodemographics, N (column %) | ||||||

| Age (mean[SD]) | 395 | 48.5 (15.9) | .09 | 52.3 (13.0) | 50.4 (13.4) | .25 |

| Gender | 389 | .46 | .53 | |||

| Female | 18 (20.9) | 52 (25.9) | 23 (22.6) | |||

| Education | 399 | .07 | .73 | |||

| Illiterate | 5 (5.8) | 25 (11.9) | 13 (12.8) | |||

| No formal school, can read | 5 (5.8) | 18 (8.6) | 8 (7.8) | |||

| Primary school | 37 (42.5) | 58 (27.6) | 34 (33.3) | |||

| Secondary school or more | 40 (46.0) | 109 (51.90) | 47 (46.1) | |||

| Employment | 399 | .11 | .81 | |||

| Government or nongovernment employee | 30 (34.5) | 53 (25.2) | 31 (30.4) | |||

| Self-employed | 21 (24.1) | 74 (35.2) | 34 (33.3) | |||

| Homemaker | 15 (17.2) | 46 (21.9) | 21 (20.6) | |||

| Not workinge | 21 (24.1) | 37 (17.6) | 16 (15.7) | |||

| Marital status | 399 | .06 | .35 | |||

| Married | 67 (77.01) | 177 (84.3) | 90 (88.2) | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Admission Diagnosis | 399 | .02 | <.001 | |||

| Tobacco-related cancerf | 9 (10.3) | 35 (16.7) | 41 (40.2) | |||

| Cancer, not tobacco-related | 5 (5.8) | 17 (8.1) | 11 (10.8) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (13.8) | 26 (12.4) | 4 (3.9) | |||

| Other diagnosis | 61 (70.1) | 132 (62.9) | 46 (45.1) | |||

| PHQ-2 ≥3 | 399 | 13 (14.9) | .11 | 43 (20.5) | 28 (27.5) | .17 |

| GAD-2 ≥3 | 399 | 10 (11.5) | .04 | 43 (20.5) | 24 (23.5) | .54 |

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| Smoker | 147 | 33 (37.9) | .81 | 74 (35.2) | 40 (39.2) | .49 |

| SLT user | 252 | 54 (62.1) | 136 (64.8) | 62 (60.8) | ||

| Daily user | 399 | 78 (89.7) | .37 | 193 (91.9) | 96 (94.1) | .48 |

| FTND/FTND-ST | 399 | 4.0 (2.4) | .69 | 4.4 (2.4) | 3.7 (2.6) | .06 |

| Past 12-month doctor visit | 399 | 57 (65.5) | .51 | 150 (71.4) | 66 (64.7) | .23 |

| Doctor asked about tobacco | 273 | 40 (70.2) | .10 | 84 (56.0) | 42 (63.6) | .29 |

| Doctor advised to quit | 166 | 32 (80.0) | .08 | 76 (90.5) | 38 (90.5) | 1.00 |

| Plan to stay quit after discharge | 334 | 27 (40.9) | .29 | 80 (44.7) | 49 (55.1) | .11 |

| Any prior cessation treatmentg | 399 | 3 (3.5) | .45 | 7 (3.3) | 0 (0.00) | .10 |

| Very important to quit | 386 | 41 (50.0) | .60 | 99 (48.8) | 63 (62.4) | .03 |

| Very confident to quit | 386 | 37 (44.6) | .71 | 85 (42.1) | 57 (56.4) | .02 |

| Very motivated to quit | 385 | 34 (41.0) | .58 | 76 (39.3) | 55 (54.5) | .01 |

| Health risks and beliefs | ||||||

| Smoking causes serious illness | 399 | 77 (88.5) | .67 | 183 (87.1) | 98 (96.1) | .01 |

| SLT causes serious illness | 398 | 77 (88.5) | .09 | 192 (91.9) | 100 (98.0) | .03 |

| Tobacco caused my hospitalizationh | 399 | 34 (39.1) | .06 | 94 (44.8) | 63 (61.8) | .004 |

| Quitting would improve my healthh | 399 | 59 (67.8) | .18 | 153 (72.9) | 81 (79.4) | .21 |

| . | . | No attempt N = 87 . | p Valueb . | Quit attemptc N = 312 . | . | p Valueb . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | Relapse N = 210 | 6-month CA N = 102 | ||||

| Sociodemographics, N (column %) | ||||||

| Age (mean[SD]) | 395 | 48.5 (15.9) | .09 | 52.3 (13.0) | 50.4 (13.4) | .25 |

| Gender | 389 | .46 | .53 | |||

| Female | 18 (20.9) | 52 (25.9) | 23 (22.6) | |||

| Education | 399 | .07 | .73 | |||

| Illiterate | 5 (5.8) | 25 (11.9) | 13 (12.8) | |||

| No formal school, can read | 5 (5.8) | 18 (8.6) | 8 (7.8) | |||

| Primary school | 37 (42.5) | 58 (27.6) | 34 (33.3) | |||

| Secondary school or more | 40 (46.0) | 109 (51.90) | 47 (46.1) | |||

| Employment | 399 | .11 | .81 | |||

| Government or nongovernment employee | 30 (34.5) | 53 (25.2) | 31 (30.4) | |||

| Self-employed | 21 (24.1) | 74 (35.2) | 34 (33.3) | |||

| Homemaker | 15 (17.2) | 46 (21.9) | 21 (20.6) | |||

| Not workinge | 21 (24.1) | 37 (17.6) | 16 (15.7) | |||

| Marital status | 399 | .06 | .35 | |||

| Married | 67 (77.01) | 177 (84.3) | 90 (88.2) | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Admission Diagnosis | 399 | .02 | <.001 | |||

| Tobacco-related cancerf | 9 (10.3) | 35 (16.7) | 41 (40.2) | |||

| Cancer, not tobacco-related | 5 (5.8) | 17 (8.1) | 11 (10.8) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (13.8) | 26 (12.4) | 4 (3.9) | |||

| Other diagnosis | 61 (70.1) | 132 (62.9) | 46 (45.1) | |||

| PHQ-2 ≥3 | 399 | 13 (14.9) | .11 | 43 (20.5) | 28 (27.5) | .17 |

| GAD-2 ≥3 | 399 | 10 (11.5) | .04 | 43 (20.5) | 24 (23.5) | .54 |

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| Smoker | 147 | 33 (37.9) | .81 | 74 (35.2) | 40 (39.2) | .49 |

| SLT user | 252 | 54 (62.1) | 136 (64.8) | 62 (60.8) | ||

| Daily user | 399 | 78 (89.7) | .37 | 193 (91.9) | 96 (94.1) | .48 |

| FTND/FTND-ST | 399 | 4.0 (2.4) | .69 | 4.4 (2.4) | 3.7 (2.6) | .06 |

| Past 12-month doctor visit | 399 | 57 (65.5) | .51 | 150 (71.4) | 66 (64.7) | .23 |

| Doctor asked about tobacco | 273 | 40 (70.2) | .10 | 84 (56.0) | 42 (63.6) | .29 |

| Doctor advised to quit | 166 | 32 (80.0) | .08 | 76 (90.5) | 38 (90.5) | 1.00 |

| Plan to stay quit after discharge | 334 | 27 (40.9) | .29 | 80 (44.7) | 49 (55.1) | .11 |

| Any prior cessation treatmentg | 399 | 3 (3.5) | .45 | 7 (3.3) | 0 (0.00) | .10 |

| Very important to quit | 386 | 41 (50.0) | .60 | 99 (48.8) | 63 (62.4) | .03 |

| Very confident to quit | 386 | 37 (44.6) | .71 | 85 (42.1) | 57 (56.4) | .02 |

| Very motivated to quit | 385 | 34 (41.0) | .58 | 76 (39.3) | 55 (54.5) | .01 |

| Health risks and beliefs | ||||||

| Smoking causes serious illness | 399 | 77 (88.5) | .67 | 183 (87.1) | 98 (96.1) | .01 |

| SLT causes serious illness | 398 | 77 (88.5) | .09 | 192 (91.9) | 100 (98.0) | .03 |

| Tobacco caused my hospitalizationh | 399 | 34 (39.1) | .06 | 94 (44.8) | 63 (61.8) | .004 |

| Quitting would improve my healthh | 399 | 59 (67.8) | .18 | 153 (72.9) | 81 (79.4) | .21 |

CA = continuous abstinence, FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, FTND-ST = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence Smokeless Tobacco Version, GAD-2 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2-item scale, PHQ-2 = Patient Health Questionnaire 2-item scale, SLT = smokeless tobacco.

aExcludes N = 38 dual users.

bBased on Student’s t-test, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test.

cSelf-reported quit attempt or ≥1 day with no tobacco use

dExcludes refused and missing.

eUnemployed, retired, or student.

fLung, oropharyngeal, laryngeal, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, cervical, colorectal, renal, bladder, and lymphoma.

gCounseling, nicotine replacement, or prescription medications.

hA little/Some/A lot versus Not at all/Don’t know.

Characteristics of Smokers (N = 147) and Smokeless Tobacco Users (N = 252) by Post-Discharge Quit Attempta

| . | . | No attempt N = 87 . | p Valueb . | Quit attemptc N = 312 . | . | p Valueb . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | Relapse N = 210 | 6-month CA N = 102 | ||||

| Sociodemographics, N (column %) | ||||||

| Age (mean[SD]) | 395 | 48.5 (15.9) | .09 | 52.3 (13.0) | 50.4 (13.4) | .25 |

| Gender | 389 | .46 | .53 | |||

| Female | 18 (20.9) | 52 (25.9) | 23 (22.6) | |||

| Education | 399 | .07 | .73 | |||

| Illiterate | 5 (5.8) | 25 (11.9) | 13 (12.8) | |||

| No formal school, can read | 5 (5.8) | 18 (8.6) | 8 (7.8) | |||

| Primary school | 37 (42.5) | 58 (27.6) | 34 (33.3) | |||

| Secondary school or more | 40 (46.0) | 109 (51.90) | 47 (46.1) | |||

| Employment | 399 | .11 | .81 | |||

| Government or nongovernment employee | 30 (34.5) | 53 (25.2) | 31 (30.4) | |||

| Self-employed | 21 (24.1) | 74 (35.2) | 34 (33.3) | |||

| Homemaker | 15 (17.2) | 46 (21.9) | 21 (20.6) | |||

| Not workinge | 21 (24.1) | 37 (17.6) | 16 (15.7) | |||

| Marital status | 399 | .06 | .35 | |||

| Married | 67 (77.01) | 177 (84.3) | 90 (88.2) | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Admission Diagnosis | 399 | .02 | <.001 | |||

| Tobacco-related cancerf | 9 (10.3) | 35 (16.7) | 41 (40.2) | |||

| Cancer, not tobacco-related | 5 (5.8) | 17 (8.1) | 11 (10.8) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (13.8) | 26 (12.4) | 4 (3.9) | |||

| Other diagnosis | 61 (70.1) | 132 (62.9) | 46 (45.1) | |||

| PHQ-2 ≥3 | 399 | 13 (14.9) | .11 | 43 (20.5) | 28 (27.5) | .17 |

| GAD-2 ≥3 | 399 | 10 (11.5) | .04 | 43 (20.5) | 24 (23.5) | .54 |

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| Smoker | 147 | 33 (37.9) | .81 | 74 (35.2) | 40 (39.2) | .49 |

| SLT user | 252 | 54 (62.1) | 136 (64.8) | 62 (60.8) | ||

| Daily user | 399 | 78 (89.7) | .37 | 193 (91.9) | 96 (94.1) | .48 |

| FTND/FTND-ST | 399 | 4.0 (2.4) | .69 | 4.4 (2.4) | 3.7 (2.6) | .06 |

| Past 12-month doctor visit | 399 | 57 (65.5) | .51 | 150 (71.4) | 66 (64.7) | .23 |

| Doctor asked about tobacco | 273 | 40 (70.2) | .10 | 84 (56.0) | 42 (63.6) | .29 |

| Doctor advised to quit | 166 | 32 (80.0) | .08 | 76 (90.5) | 38 (90.5) | 1.00 |

| Plan to stay quit after discharge | 334 | 27 (40.9) | .29 | 80 (44.7) | 49 (55.1) | .11 |

| Any prior cessation treatmentg | 399 | 3 (3.5) | .45 | 7 (3.3) | 0 (0.00) | .10 |

| Very important to quit | 386 | 41 (50.0) | .60 | 99 (48.8) | 63 (62.4) | .03 |

| Very confident to quit | 386 | 37 (44.6) | .71 | 85 (42.1) | 57 (56.4) | .02 |

| Very motivated to quit | 385 | 34 (41.0) | .58 | 76 (39.3) | 55 (54.5) | .01 |

| Health risks and beliefs | ||||||

| Smoking causes serious illness | 399 | 77 (88.5) | .67 | 183 (87.1) | 98 (96.1) | .01 |

| SLT causes serious illness | 398 | 77 (88.5) | .09 | 192 (91.9) | 100 (98.0) | .03 |

| Tobacco caused my hospitalizationh | 399 | 34 (39.1) | .06 | 94 (44.8) | 63 (61.8) | .004 |

| Quitting would improve my healthh | 399 | 59 (67.8) | .18 | 153 (72.9) | 81 (79.4) | .21 |

| . | . | No attempt N = 87 . | p Valueb . | Quit attemptc N = 312 . | . | p Valueb . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | Relapse N = 210 | 6-month CA N = 102 | ||||

| Sociodemographics, N (column %) | ||||||

| Age (mean[SD]) | 395 | 48.5 (15.9) | .09 | 52.3 (13.0) | 50.4 (13.4) | .25 |

| Gender | 389 | .46 | .53 | |||

| Female | 18 (20.9) | 52 (25.9) | 23 (22.6) | |||

| Education | 399 | .07 | .73 | |||

| Illiterate | 5 (5.8) | 25 (11.9) | 13 (12.8) | |||

| No formal school, can read | 5 (5.8) | 18 (8.6) | 8 (7.8) | |||

| Primary school | 37 (42.5) | 58 (27.6) | 34 (33.3) | |||

| Secondary school or more | 40 (46.0) | 109 (51.90) | 47 (46.1) | |||

| Employment | 399 | .11 | .81 | |||

| Government or nongovernment employee | 30 (34.5) | 53 (25.2) | 31 (30.4) | |||

| Self-employed | 21 (24.1) | 74 (35.2) | 34 (33.3) | |||

| Homemaker | 15 (17.2) | 46 (21.9) | 21 (20.6) | |||

| Not workinge | 21 (24.1) | 37 (17.6) | 16 (15.7) | |||

| Marital status | 399 | .06 | .35 | |||

| Married | 67 (77.01) | 177 (84.3) | 90 (88.2) | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Admission Diagnosis | 399 | .02 | <.001 | |||

| Tobacco-related cancerf | 9 (10.3) | 35 (16.7) | 41 (40.2) | |||

| Cancer, not tobacco-related | 5 (5.8) | 17 (8.1) | 11 (10.8) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (13.8) | 26 (12.4) | 4 (3.9) | |||

| Other diagnosis | 61 (70.1) | 132 (62.9) | 46 (45.1) | |||

| PHQ-2 ≥3 | 399 | 13 (14.9) | .11 | 43 (20.5) | 28 (27.5) | .17 |

| GAD-2 ≥3 | 399 | 10 (11.5) | .04 | 43 (20.5) | 24 (23.5) | .54 |

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| Smoker | 147 | 33 (37.9) | .81 | 74 (35.2) | 40 (39.2) | .49 |

| SLT user | 252 | 54 (62.1) | 136 (64.8) | 62 (60.8) | ||

| Daily user | 399 | 78 (89.7) | .37 | 193 (91.9) | 96 (94.1) | .48 |

| FTND/FTND-ST | 399 | 4.0 (2.4) | .69 | 4.4 (2.4) | 3.7 (2.6) | .06 |

| Past 12-month doctor visit | 399 | 57 (65.5) | .51 | 150 (71.4) | 66 (64.7) | .23 |

| Doctor asked about tobacco | 273 | 40 (70.2) | .10 | 84 (56.0) | 42 (63.6) | .29 |

| Doctor advised to quit | 166 | 32 (80.0) | .08 | 76 (90.5) | 38 (90.5) | 1.00 |

| Plan to stay quit after discharge | 334 | 27 (40.9) | .29 | 80 (44.7) | 49 (55.1) | .11 |

| Any prior cessation treatmentg | 399 | 3 (3.5) | .45 | 7 (3.3) | 0 (0.00) | .10 |

| Very important to quit | 386 | 41 (50.0) | .60 | 99 (48.8) | 63 (62.4) | .03 |

| Very confident to quit | 386 | 37 (44.6) | .71 | 85 (42.1) | 57 (56.4) | .02 |

| Very motivated to quit | 385 | 34 (41.0) | .58 | 76 (39.3) | 55 (54.5) | .01 |

| Health risks and beliefs | ||||||

| Smoking causes serious illness | 399 | 77 (88.5) | .67 | 183 (87.1) | 98 (96.1) | .01 |

| SLT causes serious illness | 398 | 77 (88.5) | .09 | 192 (91.9) | 100 (98.0) | .03 |

| Tobacco caused my hospitalizationh | 399 | 34 (39.1) | .06 | 94 (44.8) | 63 (61.8) | .004 |

| Quitting would improve my healthh | 399 | 59 (67.8) | .18 | 153 (72.9) | 81 (79.4) | .21 |

CA = continuous abstinence, FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, FTND-ST = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence Smokeless Tobacco Version, GAD-2 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2-item scale, PHQ-2 = Patient Health Questionnaire 2-item scale, SLT = smokeless tobacco.

aExcludes N = 38 dual users.

bBased on Student’s t-test, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test.

cSelf-reported quit attempt or ≥1 day with no tobacco use

dExcludes refused and missing.

eUnemployed, retired, or student.

fLung, oropharyngeal, laryngeal, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, cervical, colorectal, renal, bladder, and lymphoma.

gCounseling, nicotine replacement, or prescription medications.

hA little/Some/A lot versus Not at all/Don’t know.

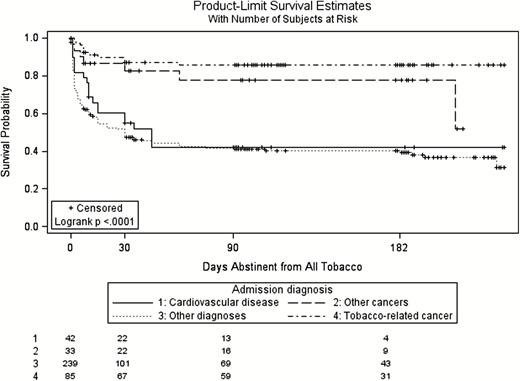

Among smokers and SLT users, use of evidence-based treatments after discharge was reported by 10 smokers (6.8%) and 16 SLT users (6.4%, p = .93). Of these, most (N = 24) used nicotine replacement therapy, three used other medications and four used counseling. In Kaplan–Meier life tables, there were no differences in time to relapse to tobacco by tobacco type (log-rank p = .08, Supplementary Figure 1). However, subjects admitted for cancer diagnoses were less likely to report relapse in follow-up (log-rank p < .001, Figure 1). Of the 164 patients who reported relapse to tobacco at one or more follow-up calls, 86.6% (N = 142) reported that the relapse occurred at or before the 30-day follow-up.

Days abstinent from all tobacco following hospital discharge by diagnosis.

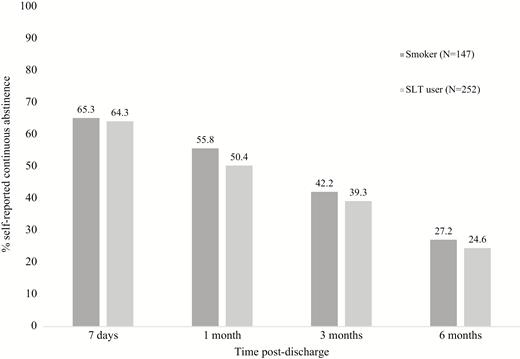

Self-reported continuous abstinence did not differ by tobacco type at any follow-up timepoint (Figure 2). In a multivariable model of 6-month continuous abstinence there was no difference between smokers and SLT users after adjusting for age, gender, admission diagnosis, PHQ-2, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, the intention to quit tobacco after discharge, importance of quitting, and confidence (Table 2). An admission diagnosis of cancer, depressive symptoms, and a lower level of nicotine dependence were associated with 6-month continuous abstinence.

Self-reported continuous abstinence by tobacco type, N = 399. Continuous abstinence defined as self-report of no tobacco use since discharge at reference time-point or a later timepoint. Those not responding assumed to be using tobacco.

| . | OR (95% CI) . | p Value . | AOR (95% CI) . | p Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLT user vs. smoker | 0.87 (0.55 to 1.39) | .56 | 1.22 (0.62 to 2.42) | .56 |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) | .65 | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | .58 |

| Female | 0.90 (0.53 to 1.54) | .71 | 1.14 (0.52 to 2.47) | .74 |

| Education: illiterate | REF | — | — | — |

| Education: no formal school, can read | 1.19 (0.37 to 3.80) | .68 | — | — |

| Education: primary school | 1.03 (0.42 to 2.55) | .62 | — | — |

| Education: secondary school or more | 0.82 (0.34 to 1.98) | .39 | — | — |

| Employment: government or nongovernment employee | REF | — | — | — |

| Employment: self-employed | 0.96 (0.54 to 1.69) | .88 | — | — |

| Employment: homemaker | 0.92 (0.48 to 1.76) | .80 | — | — |

| Employment: not workinga | 0.74 (0.37 to 1.47) | .39 | — | — |

| Married | 1.63 (0.83 to 3.19) | .15 | — | — |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Admission diagnosis: cancer-tobacco related | 3.91 (2.29 to 6.66) | <.001 | 4.12 (2.02 to 8.44) | .001 |

| Admission diagnosis: cancer-not tobacco related | 2.10 (0.95 to 4.63) | .07 | 3.03 (1.13 to 8.15) | .03 |

| Admission diagnosis: cardiovascular disease | 0.44 (0.15 to 1.30) | .14 | 0.28 (0.06 to 1.27) | .10 |

| Admission diagnosis: other | REF | — | REF | — |

| PHQ-2 ≥3 | 1.63 (0.97 to 2.75) | .07 | 2.11 (1.09 to 4.10) | .03 |

| GAD-2 ≥3 | 1.42 (0.82 to 2.44) | .21 | — | — |

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Daily user | 1.53 (0.61 to 3.84) | .36 | — | — |

| Age of first useb | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | .82 | — | — |

| FTND/FTND-ST | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.01) | .09 | 0.85 (0.71 to 0.96) | .01 |

| Plan to stay quit after discharge | 1.58 (0.97 to 2.57) | .07 | 0.92 (0.45 to 1.89) | .81 |

| Any prior quit attempt | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.55) | .93 | — | — |

| Past 12-month quit attempt | 0.93 (0.59 to 1.47) | .76 | — | — |

| Very important to quit | 1.72 (1.08 to 2.73) | .02 | 1.86 (0.71 to 4.88) | .21 |

| Very confident to quit | 1.73 (1.10 to 2.74) | .02 | 1.03 (0.36 to 2.95) | .95 |

| Very motivated to quit | 1.81 (1.14 to 2.86) | .01 | —c | — |

| Any post-discharge evidence-based treatmentd | 0.51 (0.17 to 1.52) | .23 | — | — |

| . | OR (95% CI) . | p Value . | AOR (95% CI) . | p Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLT user vs. smoker | 0.87 (0.55 to 1.39) | .56 | 1.22 (0.62 to 2.42) | .56 |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) | .65 | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | .58 |

| Female | 0.90 (0.53 to 1.54) | .71 | 1.14 (0.52 to 2.47) | .74 |

| Education: illiterate | REF | — | — | — |

| Education: no formal school, can read | 1.19 (0.37 to 3.80) | .68 | — | — |

| Education: primary school | 1.03 (0.42 to 2.55) | .62 | — | — |

| Education: secondary school or more | 0.82 (0.34 to 1.98) | .39 | — | — |

| Employment: government or nongovernment employee | REF | — | — | — |

| Employment: self-employed | 0.96 (0.54 to 1.69) | .88 | — | — |

| Employment: homemaker | 0.92 (0.48 to 1.76) | .80 | — | — |

| Employment: not workinga | 0.74 (0.37 to 1.47) | .39 | — | — |

| Married | 1.63 (0.83 to 3.19) | .15 | — | — |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Admission diagnosis: cancer-tobacco related | 3.91 (2.29 to 6.66) | <.001 | 4.12 (2.02 to 8.44) | .001 |

| Admission diagnosis: cancer-not tobacco related | 2.10 (0.95 to 4.63) | .07 | 3.03 (1.13 to 8.15) | .03 |

| Admission diagnosis: cardiovascular disease | 0.44 (0.15 to 1.30) | .14 | 0.28 (0.06 to 1.27) | .10 |

| Admission diagnosis: other | REF | — | REF | — |

| PHQ-2 ≥3 | 1.63 (0.97 to 2.75) | .07 | 2.11 (1.09 to 4.10) | .03 |

| GAD-2 ≥3 | 1.42 (0.82 to 2.44) | .21 | — | — |

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Daily user | 1.53 (0.61 to 3.84) | .36 | — | — |

| Age of first useb | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | .82 | — | — |

| FTND/FTND-ST | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.01) | .09 | 0.85 (0.71 to 0.96) | .01 |

| Plan to stay quit after discharge | 1.58 (0.97 to 2.57) | .07 | 0.92 (0.45 to 1.89) | .81 |

| Any prior quit attempt | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.55) | .93 | — | — |

| Past 12-month quit attempt | 0.93 (0.59 to 1.47) | .76 | — | — |

| Very important to quit | 1.72 (1.08 to 2.73) | .02 | 1.86 (0.71 to 4.88) | .21 |

| Very confident to quit | 1.73 (1.10 to 2.74) | .02 | 1.03 (0.36 to 2.95) | .95 |

| Very motivated to quit | 1.81 (1.14 to 2.86) | .01 | —c | — |

| Any post-discharge evidence-based treatmentd | 0.51 (0.17 to 1.52) | .23 | — | — |

AOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, FTND-ST = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence Smokeless Tobacco Version, GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire, OR = odds ratio, REF = reference group, SLT = smokeless tobacco user.

aN = 29 excluded from multivariable model due to missing ≥1 independent variable(s).

bFirst use of current product.

cExcluded due to collinearity.

dCounseling, nicotine replacement, or prescription medications.

| . | OR (95% CI) . | p Value . | AOR (95% CI) . | p Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLT user vs. smoker | 0.87 (0.55 to 1.39) | .56 | 1.22 (0.62 to 2.42) | .56 |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) | .65 | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | .58 |

| Female | 0.90 (0.53 to 1.54) | .71 | 1.14 (0.52 to 2.47) | .74 |

| Education: illiterate | REF | — | — | — |

| Education: no formal school, can read | 1.19 (0.37 to 3.80) | .68 | — | — |

| Education: primary school | 1.03 (0.42 to 2.55) | .62 | — | — |

| Education: secondary school or more | 0.82 (0.34 to 1.98) | .39 | — | — |

| Employment: government or nongovernment employee | REF | — | — | — |

| Employment: self-employed | 0.96 (0.54 to 1.69) | .88 | — | — |

| Employment: homemaker | 0.92 (0.48 to 1.76) | .80 | — | — |

| Employment: not workinga | 0.74 (0.37 to 1.47) | .39 | — | — |

| Married | 1.63 (0.83 to 3.19) | .15 | — | — |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Admission diagnosis: cancer-tobacco related | 3.91 (2.29 to 6.66) | <.001 | 4.12 (2.02 to 8.44) | .001 |

| Admission diagnosis: cancer-not tobacco related | 2.10 (0.95 to 4.63) | .07 | 3.03 (1.13 to 8.15) | .03 |

| Admission diagnosis: cardiovascular disease | 0.44 (0.15 to 1.30) | .14 | 0.28 (0.06 to 1.27) | .10 |

| Admission diagnosis: other | REF | — | REF | — |

| PHQ-2 ≥3 | 1.63 (0.97 to 2.75) | .07 | 2.11 (1.09 to 4.10) | .03 |

| GAD-2 ≥3 | 1.42 (0.82 to 2.44) | .21 | — | — |

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Daily user | 1.53 (0.61 to 3.84) | .36 | — | — |

| Age of first useb | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | .82 | — | — |

| FTND/FTND-ST | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.01) | .09 | 0.85 (0.71 to 0.96) | .01 |

| Plan to stay quit after discharge | 1.58 (0.97 to 2.57) | .07 | 0.92 (0.45 to 1.89) | .81 |

| Any prior quit attempt | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.55) | .93 | — | — |

| Past 12-month quit attempt | 0.93 (0.59 to 1.47) | .76 | — | — |

| Very important to quit | 1.72 (1.08 to 2.73) | .02 | 1.86 (0.71 to 4.88) | .21 |

| Very confident to quit | 1.73 (1.10 to 2.74) | .02 | 1.03 (0.36 to 2.95) | .95 |

| Very motivated to quit | 1.81 (1.14 to 2.86) | .01 | —c | — |

| Any post-discharge evidence-based treatmentd | 0.51 (0.17 to 1.52) | .23 | — | — |

| . | OR (95% CI) . | p Value . | AOR (95% CI) . | p Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLT user vs. smoker | 0.87 (0.55 to 1.39) | .56 | 1.22 (0.62 to 2.42) | .56 |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) | .65 | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | .58 |

| Female | 0.90 (0.53 to 1.54) | .71 | 1.14 (0.52 to 2.47) | .74 |

| Education: illiterate | REF | — | — | — |

| Education: no formal school, can read | 1.19 (0.37 to 3.80) | .68 | — | — |

| Education: primary school | 1.03 (0.42 to 2.55) | .62 | — | — |

| Education: secondary school or more | 0.82 (0.34 to 1.98) | .39 | — | — |

| Employment: government or nongovernment employee | REF | — | — | — |

| Employment: self-employed | 0.96 (0.54 to 1.69) | .88 | — | — |

| Employment: homemaker | 0.92 (0.48 to 1.76) | .80 | — | — |

| Employment: not workinga | 0.74 (0.37 to 1.47) | .39 | — | — |

| Married | 1.63 (0.83 to 3.19) | .15 | — | — |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Admission diagnosis: cancer-tobacco related | 3.91 (2.29 to 6.66) | <.001 | 4.12 (2.02 to 8.44) | .001 |

| Admission diagnosis: cancer-not tobacco related | 2.10 (0.95 to 4.63) | .07 | 3.03 (1.13 to 8.15) | .03 |

| Admission diagnosis: cardiovascular disease | 0.44 (0.15 to 1.30) | .14 | 0.28 (0.06 to 1.27) | .10 |

| Admission diagnosis: other | REF | — | REF | — |

| PHQ-2 ≥3 | 1.63 (0.97 to 2.75) | .07 | 2.11 (1.09 to 4.10) | .03 |

| GAD-2 ≥3 | 1.42 (0.82 to 2.44) | .21 | — | — |

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Daily user | 1.53 (0.61 to 3.84) | .36 | — | — |

| Age of first useb | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | .82 | — | — |

| FTND/FTND-ST | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.01) | .09 | 0.85 (0.71 to 0.96) | .01 |

| Plan to stay quit after discharge | 1.58 (0.97 to 2.57) | .07 | 0.92 (0.45 to 1.89) | .81 |

| Any prior quit attempt | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.55) | .93 | — | — |

| Past 12-month quit attempt | 0.93 (0.59 to 1.47) | .76 | — | — |

| Very important to quit | 1.72 (1.08 to 2.73) | .02 | 1.86 (0.71 to 4.88) | .21 |

| Very confident to quit | 1.73 (1.10 to 2.74) | .02 | 1.03 (0.36 to 2.95) | .95 |

| Very motivated to quit | 1.81 (1.14 to 2.86) | .01 | —c | — |

| Any post-discharge evidence-based treatmentd | 0.51 (0.17 to 1.52) | .23 | — | — |

AOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, FTND-ST = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence Smokeless Tobacco Version, GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire, OR = odds ratio, REF = reference group, SLT = smokeless tobacco user.

aN = 29 excluded from multivariable model due to missing ≥1 independent variable(s).

bFirst use of current product.

cExcluded due to collinearity.

dCounseling, nicotine replacement, or prescription medications.

Discussion

This longitudinal observational study of 437 tobacco users admitted to a hospital in Mumbai demonstrates that in India, as in Western populations,1 hospitalization is a teachable moment with the potential to encourage tobacco cessation. The proportion of former tobacco users in the inpatient sample is larger than the general Indian population. Current health problems are the most common reason for quitting among former users. Among current tobacco users, more than three-quarters of current users in this study reported making a post-discharge quit attempt, and one in four reported staying abstinent for 6 months. The most common reason for quitting after discharge was current health problems, as it was for former users. Nearly all of those who tried and failed to quit relapsed in the first 30 days after discharge. Very few of these individuals used any evidence-based cessation treatment, consistent with tobacco cessation treatment in India in general.20 More of the tobacco users who were prompted by a hospitalization to try to quit might be successful if provided a cessation intervention that started in the hospital and continued after discharge. This hypothesis deserves to be tested, and our findings provide a strong rationale for doing so.

A distinctive feature of tobacco use in India is the heterogeneity of tobacco products. This study compared smokers and SLT users and found socioeconomic and demographic differences between SLT users and smokers that were consistent with prior work.20 Furthermore, SLT users in this study differed from smokers in characteristics that might reduce the likelihood of cessation. SLT users were less likely to believe that their tobacco use was harmful or that their hospitalization was attributable to their tobacco use and less likely to plan to quit after discharge. Prior work has shown a shift in tobacco product preferences in three Asian countries toward more SLT use relative to smoking and the authors attribute that shift in part to tobacco company practices which suggest SLT is a safer alternative to smoking.9 There is a need for better communication of the risks of SLT products used in India, which could be incorporated into an intervention targeting hospital patients. Despite their differences, however, smokers and SLT users did not differ in their report of attempting to quit after discharge or of achieving continuous abstinence for 6 months. A hospital admission appears to be an opportune time for offering cessation interventions to both types of tobacco users.

SLT users were a more heterogeneous group in terms of the number of tobacco products used than smokers in this study. Although both smokers and SLT users reported a median of one current tobacco product, smokers nearly all used cigarettes whereas SLT users reported a wide variety of tobacco products including betel quid with tobacco, mishri, tobacco with slake lime, and gutkha. This diversity of products may present a challenge for cessation services which aim to assist both smokers and SLT users.

The only independent predictors of self-reported continuous abstinence in this study were admission diagnosis, depressive symptoms, and nicotine dependence. Tobacco users with an admission diagnosis of cancer were more likely to remain abstinent after discharge. Participants with cancer diagnoses may have been more motivated by the nature and severity of the diagnosis or have received more advice or encouragement to quit tobacco from their health care providers. This echoes the finding that among current tobacco users, cancer was more commonly identified as a health consequence of smoking and SLT use than cardiovascular disease or stroke. This heightened recognition of the cancer risks of tobacco may make patients with cancer diagnoses especially receptive to cessation advice. That patients admitted for cardiovascular disease were not more likely to abstain contrasts with patterns in high income countries.21 From an intervention standpoint, educating patients in India about the cardiovascular risks of tobacco use may make cardiac patients more receptive to cessation messages.

Post-discharge tobacco cessation was also independently associated with a higher score on a brief scale of depressive symptoms. This contrasts with prior work in which cessation is more frequent among individuals with less depression.22–24 These inconsistencies may be unique to the hospital setting with its associated external stresses and internal vulnerabilities. Other possibilities for the discrepancy include cross-cultural differences in the reporting of psychiatric symptoms or in the performance of the PHQ-2 scale in a South Asian population.

Overall, nearly one in four tobacco users reported staying abstinent after hospital discharge regardless of tobacco type. This is higher than rates seen in high-income settings delivering usual care.1,25 Most subjects who remained abstinent for 6 months after discharge did so without the assistance of evidence-based tobacco cessation treatments. Whether the low rates of treatment use are due to patient preferences or the unavailability of treatment was not assessed, but we suspect that it is the latter because in India, cessation medicines have a high cost and access to behavioral counseling resources such as telephone quitlines for tobacco users are limited. The steep decline in abstinence that we measured in the first 30 days after discharge suggests that extending hospital-based interventions after discharge may be an essential feature of an effective program, as is the case in high-income settings.1

Limitations

Tobacco use information in this study is collected by both self- and proxy-report. The accuracy of self- and proxy-report is not known in this setting but proxy has been found to be less accurate in other settings.26 Using self-report of tobacco use is a major limitation but biochemical validation is beyond the scope of this study in terms of resources. Although we provided no intervention, the assessment of tobacco use and perceived harms of tobacco at baseline may have influenced post-discharge cessation behaviors or willingness to admit to tobacco use in follow-up. Accuracy of self-reported tobacco use after hospitalization has been measured elsewhere and accuracy of self-reported SLT use has been measured in India, and these studies suggest underreporting of continued tobacco is likely.27,28 The prevalence of self-reported current tobacco use among hospitalized patients in Mumbai is lower than in the general Indian population.29 In this sample, more hospitalized patients reported being former tobacco users than current tobacco users. Many users may have quit when first diagnosed with a tobacco-related illness, and this may have occurred prior to admission. This study was conducted at a single hospital, specializing in cancer and cardiac care which serves a socioeconomically diverse population and results may not be generalizable to other hospitals.

Conclusions

Among hospitalized patients who use tobacco, one in four, including both smokers and SLT users, reported sustained cessation for 6 months after discharge. However, many more patients tried to quit and failed, and almost no patient used evidence-based assistance. Offering additional post-discharge support might have helped more people to quit successfully. Providing tobacco interventions in a hospital setting is consistent with guidelines for implementing Article 14 of the World Health Organization’s landmark Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.30,31 This document, which India ratified, advises the documentation of tobacco status and delivery of brief advice to all tobacco users at every health care interaction. Beyond brief advice, our work suggests hospital-based cessation assistance that extends beyond discharge deserves to be tested because it has the potential to improve individual outcomes and reduce the burden of tobacco-related illness in India.

Funding

This project was supported by the Narotam Sekhsaria Foundation. GRK was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (no. 5K23DA038717). NAR was supported by the MGH Executive Committee on Research.

Declaration of Interests

GRK was a paid consultant for Click Therapeutics and has a family financial interest in Dimagi, Inc. NAR has had a research grant and been an unpaid consultant to Pfizer and receives royalties from UpToDate.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our counselor Rashmi Asthana and our data collector Deepali Patil for their contribution to the study and the Prince Aly Khan Hospital management and staff.

Comments