-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Taneisha S. Scheuermann, Kimber P. Richter, Lisette T. Jacobson, Theresa I. Shireman, Medicaid Coverage of Smoking Cessation Counseling and Medication Is Underutilized for Pregnant Women, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 19, Issue 5, 1 May 2017, Pages 656–659, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw263

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Policies to promote smoking cessation among Medicaid-insured pregnant women have the potential to assist a significant proportion of pregnant smokers. In 2010, Kansas Medicaid began covering smoking cessation counseling for pregnant smokers. Our aim was to evaluate the use of smoking cessation benefits provided to pregnant women as a result of the Kansas Medicaid policy change that provided reimbursement for physician-provided smoking cessation counseling.

We examined Kansas Medicaid claims data to estimate rates of delivery of smoking cessation treatment to Medicaid-insured pregnant women in Kansas from fiscal year 2010 through 2013. We analyzed the number of pregnant women who received physician-provided smoking cessation counseling indicated by procedure billing codes (ie, G0436 and G0437) and medication (ie, nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, or varenicline) located in outpatient managed care encounter and fee-for-service claims data. We estimated the number of Medicaid-insured pregnant smokers using the national smoking prevalence (14%) in this population and the number of live births reported in Kansas.

Annually from 2010 to 2013, approximately 27.2%–31.6% of pregnant smokers had claims for nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, or varenicline. Excluding claims for bupropion, a medication commonly prescribed to treat depression, claims ranged from 9.3% to 11.1%. Following implementation of Medicaid coverage for smoking cessation counseling, less than 1% of estimated smokers had claims for counseling.

This low claims rate suggests that simply changing policy is not sufficient to ensure use of newly implemented benefits, and that there probably remain critical gaps in smoking cessation treatment.

This study evaluates the use of Medicaid reimbursement for smoking cessation counseling among low-income pregnant women in Kansas. We describe the Medicaid claims rates of physician-provided smoking cessation counseling for pregnant women, an evidence-based and universally recommended treatment approach for smoking cessation in this population. Our findings show that claims rates for smoking cessation benefits in this population are very low, even after policy changes to support provision of cessation assistance were implemented. Additional studies are needed to determine whether reimbursement is functioning as intended and identify potential gaps between policy and implementation of evidence-based smoking cessation treatment.

Introduction

Smoking during pregnancy is associated with major adverse health outcomes including increased risk of preterm membrane rupture, placenta previa, still birth, and neonatal mortality.1 Women who smoke during pregnancy also double their risk of having a low birth weight infant compared to nonsmoking women.1 Low-income women have higher smoking rates and are less likely to quit smoking during pregnancy.2 As such, Medicaid-insured women are at greater risk for continued smoking in their third trimester (11.4%) compared to 8.4% of pregnant women overall.3

Policies to promote smoking cessation among Medicaid-insured pregnant women have the potential to assist a significant proportion of women who smoke. Data from the US Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring Systems (PRAMS) show that pregnant smokers in states with higher levels of Medicaid coverage for prenatal smoking cessation (ie, medications and counseling) had higher quit rates compared to states with lower or no coverage.4 However, when controlling for demographic characteristics, state-level income per capita, and other tobacco control policies (eg, smoking bans in restaurants), living in states that provided Medicaid smoking cessation coverage only reduced smoking prevalence among women enrolled before pregnancy; there was no association with smoking during pregnancy.5 This null result and other recent studies call into question use of Medicaid smoking cessation benefits among pregnant women. National estimates suggest that only 10% of Medicaid adults who smoke received any smoking cessation medications (ie, nicotine replacement therapy [NRT], bupropion, or varenicline),6 and state-level data from Maryland show that only 2.4% of pregnant smokers received NRT or varenicline.7 No studies have examined Medicaid reimbursement claims for smoking cessation counseling among pregnant women.

One third of women giving birth in the state of Kansas are insured through the state’s Medicaid program.8 Following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA),9,10 Kansas Medicaid began providing reimbursement for smoking cessation counseling for pregnant smokers effective October 2010 with no cost-sharing.11 Retroactively effective to July 1, 2011, the individual smoking cessation billing codes were changed to G0436 and G0437 which currently remain in effect.12,13 Billing codes for smoking cessation counseling must be used in conjunction with diagnosis code 649.00 (defined as tobacco use disorder complicating pregnancy, childbirth, or the puerperium, unspecified as to episode of care or not applicable) or 649.03 (defined as tobacco use disorder complicating pregnancy, childbirth, or the puerperium, antepartum condition or complication). This new provision was in addition to previous coverage that provided smoking cessation medications (ie, NRT, bupropion, or varenicline) to all Medicaid participants that also do not require cost-sharing by the insured.

As required by federal law, Kansas offers Medicaid coverage to pregnant women, children, seniors, individuals with disabilities, and parents whose income is below the eligibility threshold.14 In Kansas, pregnant women with an income up to 166% of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) are eligible.14 Medicaid coverage for pregnant women includes prenatal care, delivery, and postpartum care up to 60 days after delivery.15 Kansas has not expanded Medicaid coverage to include low-income adults, and parents with dependent children must have a household income of 33% of the FPL or below to be eligible.14

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the use of smoking cessation benefits provided to pregnant women as a result of the Kansas Medicaid policy change that provided reimbursement for individual physician-provided smoking cessation counseling. We examined Kansas Medicaid billing data to estimate rates of delivery of smoking cessation treatment to Medicaid-insured pregnant women. We obtained outpatient managed care encounter and fee-for-service claims data from Kansas Medicaid through the Data Analytic Interface (under a business associates agreement with Dr Theresa Shireman).

Methods

We extracted claims for smoking cessation counseling and pharmacotherapy from fiscal years 2010–2013 from the Kansas Medicaid outpatient managed care encounter and fee-for-service claims data. We limited the claims to women who were pregnant during each year; pregnancies were identified using the following ICD-9 codes: 640–679, V22–V24, V27, and V28. Claims for physician-provided smoking cessation counseling were identified using Procedure billing codes G0436 (counseling lasting 3–10 minutes) and G0437 (counseling for greater than 10 minutes) and were examined for fiscal years 2011–2013, the timeframe for which these codes were implemented. Pharmacy claims were also reviewed for filled prescriptions for smoking cessation medications including any NRT, bupropion, or varenicline.

As we were unable to identify which women were smokers, we used an ecologic approach to estimate the proportion of pregnant women who were smokers. We used the number of live births paid for by Medicaid in each year as the denominator obtained from the Kansas Department of Health and Environment annual reports. Approximately 64% of US pregnancies result in live births,16 and we used live births as a conservative estimate for the number of pregnant women who may have attended multiple prenatal visits that would have allowed for smoking cessation treatment.

Results

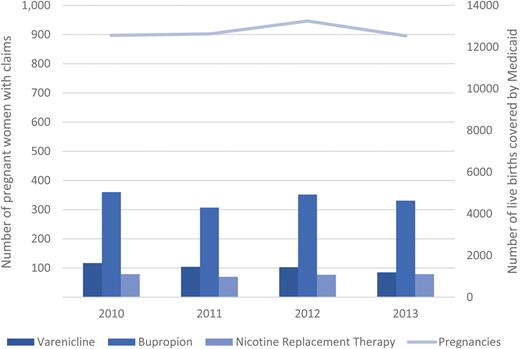

We identified 18976–25767 Kansas Medicaid enrollees with pregnancy-related ICD-9 codes between 2010 and 2013. There were only five claims for smoking cessation counseling during the following fiscal years: 2011 (one G0436 claim), 2012 (two G0436 claims), and 2013 (two G0436 and one G0437 claims). Provision of smoking cessation medications was higher with 117 women receiving varenicline, 360 women receiving bupropion, and 79 receiving NRT in 2010. Pharmacy claims for these medications were similar over the years 2010–2013 (see Figure 1). Notably, 85 women received varenicline in 2013 compared to a range from 103 to 117 in the prior 3 years.

Pharmacy claims for smoking cessation medications across fiscal years.

Using data reported by the state, there were between 12542 and 13249 births in Kansas paid for by Medicaid in years 2010–2013.8,17–19 Using the national prevalence rate of smoking during pregnancy among Medicaid-paid deliveries (14%),3 we would expect at least 1755 pregnant smokers each year. If we assume that each woman only received one type of smoking cessation medication, then 556 would have been considered treated with medications out of 1758 in 2010 or 31.6%. Claims rates for subsequent years were 27.2% in 2011 (481 claims/1768 estimated smokers), 28.7% in 2012 (532 claims/1854 estimated smokers), and 28.2% in 2013 (495 claims/12542 smokers). Excluding pharmacy claims for bupropion which is also commonly prescribed for treating depression, 11.1% of estimated smokers received smoking cessation medications in 2010 (196 claims), 9.8% in 2011 (174 claims), 9.7% in 2012 (180 claims), and 9.3% in 2013 (164 claims). The proportion of women with billing claims for evidence-based, reimbursable counseling by their physician was less than 1%.

Discussion

In this Midwestern state, claims for smoking cessation counseling and smoking cessation medications among Medicaid-insured pregnant women were very low. A number of factors may have influenced the number of billing claims, including that providers may have been unaware of Medicaid benefits,20 they may have been providing services but not using billing codes, or patients may have refused counseling or medications at high rates. The extremely low utilization rates for smoking cessation counseling reimbursement are concerning because behavioral treatment for tobacco dependence is universally indicated for all pregnant women who smoke and is recommended as the initial step in treatment in multiple guidelines for treating tobacco dependence among pregnant women.21,22 At the very least, findings indicate that reimbursement for counseling is not serving as an incentive to provide treatment to pregnant smokers. Whether or not clinicians are providing counseling, our study findings show they appear not to claim reimbursement for this service.

Our data are consistent with a recent study reporting low Medicaid claims rates for smoking cessation pharmacotherapy across the United States6 and for pregnant smokers in the Maryland Medicaid program.7 As noted above, potential reasons for low numbers of claims could be that providers are counseling women on quitting smoking but are not billing for this intervention, or they may not be providing prescriptions for smoking cessation medications because they do not know that they are covered by Medicaid. In fact, a recent study shows that only 17% of obstetrician–gynecologists were aware of the ACA provisions for smoking cessation assistance for pregnant women.20 Another potential reason for low pharmacotherapy claims could be that women receive prescriptions but do not fill them. Possible interventions include educating providers and Medicaid participants about Medicaid smoking cessation benefits. There is evidence that media campaigns directed at Medicaid participants can increase use of cessation benefits.23

Our study provides preliminary findings on use of the Medicaid smoking cessation benefit for pregnant women in one state that has not opted to expand Medicaid eligibility. There are a number of limitations. First, this study was an ecological study based on extracted claims and we could not determine smoking status at the individual level. Second, we were unable to identify whether smoking cessation counseling was included in bundled claims rather than as individual billing claims. Third, we used a wide range of ICD-9 codes to identify pregnancies and report the number of patients who received counseling and pharmacotherapy each fiscal year, but conservatively used live births as the denominator for utilization rates. Consequently we expect that our findings likely overestimate rates of filled prescriptions for pregnant smokers. In context, our findings assessed only Medicaid claims for dispensed prescriptions for women who were pregnant during each year and could include postpartum prescriptions. Therefore, our findings may not indicate the true rate that physicians were prescribing these medications for use during pregnancy. Further, we are unable to distinguish whether bupropion was prescribed specifically to assist women in quitting smoking or for the treatment of depression.

Future studies should evaluate quit rates among Medicaid-insured pregnant smokers who receive reimbursable smoking cessation counseling and pharmacotherapy. These studies should use person-level smoking status data collected via self-report to pinpoint actual rates of tobacco dependence diagnoses, smoking cessation counseling claims, and pharmacotherapy claims. To determine the impact of Medicaid policies, studies should link treatment utilization to cessation outcomes. To date, findings on the effect of Medicaid coverage of smoking cessation assistance for pregnant women have been mixed. These studies were ecological studies that focused on reductions in state-level smoking among pregnant women and that did not account for use of services.4,5

In conclusion, preliminary evidence from Kansas shows very low use of physician-provided smoking cessation counseling Medicaid billing codes for pregnant women after implementation of the ACA mandate. These state-level Medicaid claims data suggest that simply changing policy is not sufficient to ensure use of newly implemented benefits, and that there probably remain critical gaps in smoking cessation treatment delivery for pregnant women. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether reimbursement is functioning as intended and to identify potential gaps between policy and implementation of evidence-based smoking cessation treatment.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

Author notes

Corresponding Author: Taneisha S. Scheuermann, PhD, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA. Telephone: 913-588-2616; Fax: 913-588-2780; E-mail: [email protected]

Comments