-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mallika P Patel, Eric S Lipp, Elizabeth S Miller, Patrick N Healy, James E Herndon, Katherine B Peters, Availability and role of clinical pharmacists in ambulatory neuro-oncology, Neuro-Oncology Practice, Volume 9, Issue 1, February 2022, Pages 18–23, https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npab060

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Outpatient clinics treating neuro-oncology patients are becoming more multidisciplinary. Utilization of all team members is critical for the holistic care of these complex patients. Specifically, the role of clinical pharmacist (CP) in the ambulatory clinic remains undefined and will likely evolve as more therapeutics are developed for CNS malignancies. We queried the Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) membership about the availability of a CP in their ambulatory setting and, if present, the role of that CP.

In an IRB-exempt study, we surveyed the SNO community and analyzed responses to queries about CPs in the ambulatory setting.

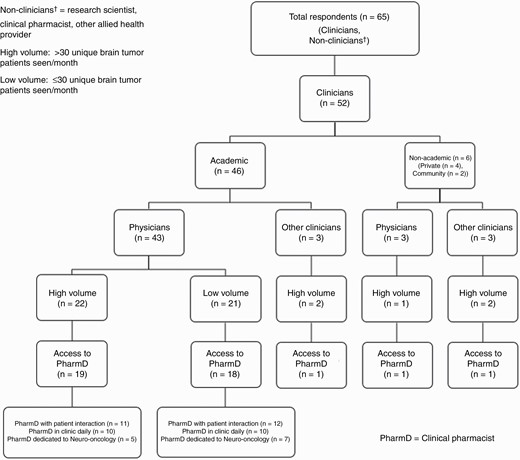

Of the 65 SNO members who responded, 52 were clinical members. Of these 52 clinicians, the majority were physicians (88.5%, n = 46). Of these physicians, most were in academic practices (93.5%, n = 43). Over half of the 52 clinical respondents (51.9%, n = 27) reported that they saw ≥30 primary brain tumor patients per month, thus typifying busy clinics. Despite having busy clinics, only 12 (28.6%) of 42 providers with access to a CP reported that their CP was solely dedicated to neuro-oncology patients. For the respondents who had access to a CP, only ~two-thirds of those CPs had direct patient interaction. The top 3 roles of the CP included medication review, chemotherapy dosing/modifications, and practice guideline development; none of which involve direct patient interaction.

We found that while our surveyed population of SNO clinical members have demanding outpatient practices, most do not have the support or expertise of dedicated neuro-oncology CPs.

Neuro-oncology patients have unique oncologic and neurologic treatment demands which contribute to their complex care. Outpatient clinics that treat neuro-oncology patients are becoming more multidisciplinary, and utilization of all team members is critical for providing best practice.1,2 Authors of the European Association for Neuro-Oncology Guideline on the “Diagnosis and treatment of adult astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas” state that implementing these recommendations requires multidisciplinary care.3 Further, this aligns with the Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and the organization’s dedication to multidisciplinary research, education, and collaboration to drive discovery and improve patient care.4 While the specialty of neuro-oncology is conducive to a multidisciplinary approach, the role of a clinical pharmacist (CP) in this setting remains to be defined. We envision that as more therapeutic options are developed to treat primary and metastatic central nervous system malignancies that CPs’ role will likely evolve. In ambulatory oncology, the role of the CP not only involves chemotherapy preparation and dosing and administration review, but also supportive education for staff, patients, and caregivers, involvement in clinical research, and development of institutional and practice guidelines. One study by Meleis et al examined the role and impact of oncology CPs in an academic practice setting. These investigators demonstrated the magnitude of interventions (5901 interventions over a 6-month period) highlighting oncology CPs involvement while embedded into specific ambulatory clinics.5 Meleis et al demonstrated that pharmacists are highly valued members of the multidisciplinary team. Although data exist to show CPs involvement in oncology clinics, there is a paucity of data when considering the sub-specialty of neuro-oncology. We sought to quantify and better understand the activities in which CPs participate in neuro-oncology clinics as well as their level of involvement in this setting. With better awareness, neuro-oncology clinics and providers can integrate CPs as vital team members.

Methods

We conducted this prospective, Institutional Review Board (IRB)-exempt analysis of the SNO membership, primarily targeting clinical providers. An email questionnaire was sent to SNO members regarding the availability of a CP in their respective ambulatory settings and, if present, the role of that pharmacist. The SNO member-to-member survey process includes an application to the scientific planning chairs of that year’s SNO annual meeting, which if approved, is circulated one time to the Society’s email list. The survey consisted of 13 questions incorporating branched chain logic to determine demographics including type and size of practice setting, access to a CP, and activities in which the CP participates. A full list of survey questions is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at Duke University Health System.6

The primary aim of this analysis was to describe the presence and function of a CP in the ambulatory neuro-oncology practice setting. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the demographics of survey respondents and summarize survey responses. We conducted the survey per the ethical standards of the IRB of the Duke University Health System.

Results

Our survey questionnaire was sent to multidisciplinary SNO members, including clinical providers, research scientists, CPs, and other allied health providers. Per the SNO annual meeting planning committee, the survey was distributed to 1895 unique email addresses, with 65 total respondents (Table 1). Our target population was clinicians practicing in the ambulatory setting; of the total respondents, 52 are clinicians (80%). Forty-four of the 52 clinician respondents practice in the United States, while 8 practice internationally (Canada = 4, Europe = 3, Middle East = 1). The majority of clinician respondents practice in academic settings (n = 46), most of which are physicians (n = 43). As illustrated in Figure 1, survey respondents are categorized by discipline; practice area (academic, private, or community); the volume of patients seen in clinic per month; and their access to a CP. Additionally, a distinction is made regarding the CPs’ level of patient interaction, time in clinic, and dedication to neuro-oncology patients.

| Role . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Physician | 46 | 70.77 |

| Nurse | 1 | 1.54 |

| Advanced Practice Provider | 5 | 7.69 |

| Clinical Pharmacist | 6 | 9.23 |

| Other Allied Health Provider | 4 | 6.15 |

| Research Scientist | 3 | 4.62 |

| Role . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Physician | 46 | 70.77 |

| Nurse | 1 | 1.54 |

| Advanced Practice Provider | 5 | 7.69 |

| Clinical Pharmacist | 6 | 9.23 |

| Other Allied Health Provider | 4 | 6.15 |

| Research Scientist | 3 | 4.62 |

| Role . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Physician | 46 | 70.77 |

| Nurse | 1 | 1.54 |

| Advanced Practice Provider | 5 | 7.69 |

| Clinical Pharmacist | 6 | 9.23 |

| Other Allied Health Provider | 4 | 6.15 |

| Research Scientist | 3 | 4.62 |

| Role . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Physician | 46 | 70.77 |

| Nurse | 1 | 1.54 |

| Advanced Practice Provider | 5 | 7.69 |

| Clinical Pharmacist | 6 | 9.23 |

| Other Allied Health Provider | 4 | 6.15 |

| Research Scientist | 3 | 4.62 |

The questionnaire also included the clinician respondents’ time in their practice settings, with almost 50% of respondents (n = 25) being in practice for 10 or more years. Over half of the 52 clinical respondents (51.9%, n = 27) reported that they saw greater than 30 unique brain tumor patients per month, defined as a high-volume clinic. Only 12 (28.6%) of the 42 providers with access to a CP reported that their CP was solely dedicated to neuro-oncology patients. Of the 42 providers with access to a CP, 24 (57.1%) of these providers collaborated with a CP in the outpatient clinic daily.

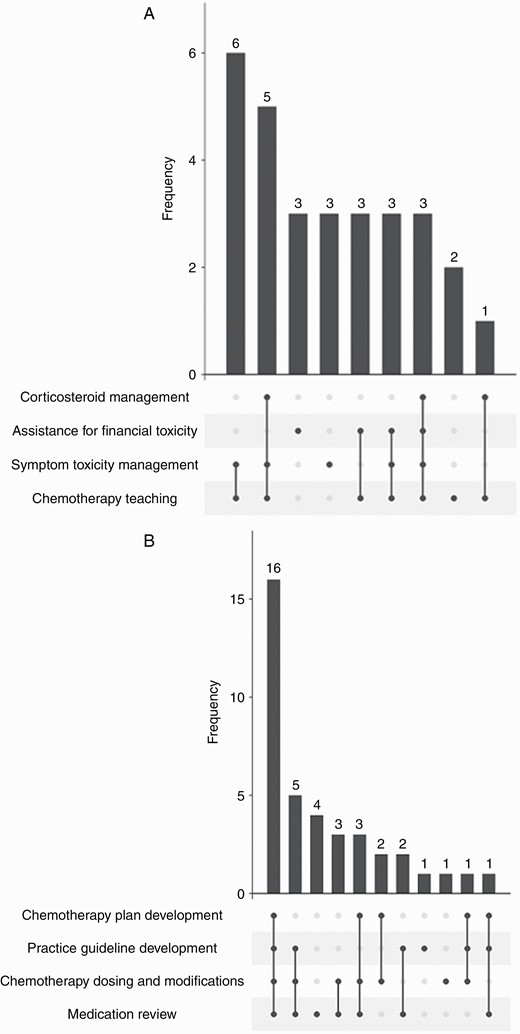

The questionnaire included specific questions about the role of the CP in patient care. Survey participants were asked to identify activities in which their CP participates. The following is an all-inclusive list of activities included in our survey: Chemotherapy teaching, Chemotherapy dosing and modifications, Development of chemotherapy plans, Corticosteroid management, Institutional/practice guideline development, Anti-epileptic drug therapy management, Antibiotic management, Medication review for possible drug interactions or adverse events, Clinical trial recruitment, Clinical trial eligibility determination, Patient assistance for financial toxicity, Prior authorizations, Staff education/in-services, Supplement reviews, Symptom/toxicity management, and Resident/fellow teaching. There was also a category listed as other, with the option for survey participants to free text in additional activities. Some of the additional activities that survey participants listed include: checking prescription and compliance with research protocols, patient medication calendar, non-chemotherapy drug teaching, and providing clinical trial chemotherapy drugs to patients. Of the 42 respondents with access to a CP, Figure 2 depicts the frequency of each activity with CP participation. Overall, the most common activities, including those with a frequency >50%, include medication review for possible drug interactions or adverse events (n = 34, 81%), chemotherapy dosing and modifications (n = 31, 73.8%), institutional/practice guideline development (n = 26, 61.9%), chemotherapy teaching (n = 23, 54.8%), and development of chemotherapy plans (n = 23, 54.8%).

Clinical pharmacist activities. (a) Clinical pharmacist activities with direct patient interaction. (b) Clinical pharmacist activities without direct patient interaction.

These activities were further categorized based on if they included direct patient interaction or those activities without direct patient interaction. For those survey participants with access to a CP, only 28 (66.7%) of those pharmacists had direct patient interaction in the clinic. The top 3 activities with direct patient interaction include chemotherapy teaching, symptom/toxicity management from treatment, and patient assistance for financial toxicity. Figure 2a and b further illustrate the top 4 activities of a CP with and without direct patient care.

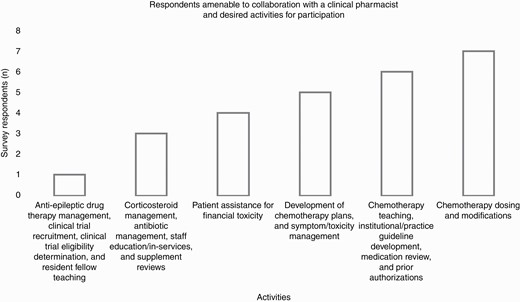

Survey participants were also given the opportunity to state if they would be receptive to working with a CP if they did not have access to one in their practice. Of the 52 clinicians, 10 reported that they did not have access to a CP. Of those 10 respondents, 80% (n = 8) reported that they would be receptive to collaborating with a CP. The following activities were most commonly (>75%) described by respondents as those which would be amendable to CP involvement, including chemotherapy dosing/modifications, chemotherapy teaching, institutional/practice guideline development, medication review for possible drug interactions or adverse drug events, and prior authorizations. Of note, chemotherapy teaching was the only one of these activities with direct patient interaction that those without access to a CP reported interest in pharmacist involvement. A comprehensive list of activities these 8 clinicians were responsive to CP’s involvement in, if available as a resource, is detailed in Figure 3.

Respondents amenable to collaboration with a clinical pharmacist and desired activities for participation.

Discussion

Pharmacists have had varying functions within oncology practices over the years; however, their role in a clinical capacity has increased steadily since the 1960s with more direct patient involvement.7 While the exact breadth is hard to quantify, hundreds of studies have examined CP interventions in oncology ambulatory settings.5,8,9 In the study by Meleis et al, the investigators sought to understand the perceived contribution and impact of a CP on patient care via a survey that was distributed to providers and nurses. The authors concluded that CPs add value to patient care and are integral team members.5 In another study, Maleki et al, reviewed over 900 publications during a 10-year period. The final analysis included 13 studies that met pre-defined criteria and provided specific data about the description and utility of outpatient pharmacy clinical services for oncology cancer clinics.8 While the overall results support CP services in oncology settings, it is hard to draw compelling conclusions as the studies were not uniform and included bias.

In a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), published in 2016, authors describe how patient care services provided by pharmacists can reduce fragmented care, lower health care costs, and improve health outcomes.10 Similar outcome-based data specific to neuro-oncology patients are not yet available. Lee et al evaluated justifying a neuro-oncology CP position through quantitative assessment of interventions as well as financial benefit shown through re-allocation of physician time. Involving the CPs into clinic workflow allowed for physicians to increase dedicated face-to-face time with patients as well as increasing available patient slots.11 This 14-day pilot study showed the financial benefit of a dedicated CP role in the neuro-oncology clinic setting.11 Within the specialty of neuro-oncology, there is a niche role for a CP, as many providers are neurology-trained12 and may benefit from collaboration with an oncology-specialty trained CP. Further, many neuro-oncologists practice in both specialty areas, often transitioning between the 2 patient populations routinely. Collaboration with an oncology-specialty trained CP may provide further expertise in chemotherapy management.

The goal of our survey was to determine the availability of CPs in the ambulatory neuro-oncology setting and further to better understand the role of the CP. In our survey, over half of the clinical respondents (51.9%) reported that they practiced in a high-volume clinic. Even in spite of demanding clinics, only ~30% of these providers with access to a pharmacist had one embedded within the clinic setting. By physically distancing the CP from the multidisciplinary team, there may be potential for missed patient interventions, for example, chemotherapy dose modifications, patient education, or symptom management. For those survey respondents with access to a CP, only two-thirds of those pharmacists had direct patient interaction in the clinic. In a study by Delaney et al, researchers looked at the feasibility of integrating a pharmacist in a neuro-oncology clinic. They found that over a 4-month period, the clinical team reported improved clinical efficiency directly due to a CP’s presence. Patients were also surveyed regarding their perception of this direct interaction with a pharmacist. Remarkably, every patient reported that they received useful information from the pharmacist. Patients also reported less stress related to their treatment. Moreover, 90% of patients expressed that the pharmacist should remain a part of the neuro-oncology team. While our survey did not incorporate patient or provider perceptions of the CP, this small study examined these perceptions and supported that a CP should be a permanent member of the ambulatory neuro-oncology clinical team.13

The low survey response rate was a limitation of our study. The survey was sent to a total of 1895 individual email addresses with a ~3.5% response rate. Unfortunately, the survey was sent to an unknown number of nonclinical members as well as trainees, which may have minimized responses. The title of the survey, “Role of Clinical Pharmacists in Neuro-Oncology Clinics” may have biased the participants only to respond if they had a pharmacist present, thereby missing those individuals who would be receptive to working with this discipline. With higher survey participation, investigators may better understand the true access of neuro-oncology providers to CPs.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Although many members of the SNO clinical community have demanding outpatient neuro-oncology practices, most do not have the support or expertise of a dedicated neuro-oncology CP. Education about the roles and activities in which a CP can participate and provide valuable input may help to increase access to and utilization of a team-based approach to care. Further investigation regarding potential cost-savings, avoidance of medication errors, and patient-related satisfaction should be evaluated to glean future data on the value of a CP as an integral member of the multidisciplinary neuro-oncology team.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References