-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hanneke Zwinkels, Linda Dirven, Helen J Bulbeck, Robin Grant, Esther J J Habets, Johan A F Koekkoek, Ingela Oberg, Kathy Oliver, Andrea Pace, Alasdair G Rooney, Maaike J Vos, Martin J B Taphoorn, Identification of characteristics that determine behavioral and personality changes in adult glioma patients, Neuro-Oncology Practice, Volume 8, Issue 5, October 2021, Pages 550–558, https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npab041

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Glioma patients may experience behavioral and personality changes (BPC), negatively impacting their lives and that of their relatives. However, there is no clear definition of BPC for adult glioma patients, and here we aimed to determine which characteristics of BPC are relevant to include in this definition.

Possible characteristics of BPC were identified in the literature and presented to patients and (former) caregivers in an online survey launched via the International Brain Tumour Alliance. Participants had to rate the relevance of each presented characteristic of BPC, the three characteristics with the most impact on their lives, and possible missing characteristics. A cluster analysis and discussions with experts provided input to categorize characteristics and propose a definition for BPC.

Completed surveys were obtained from 140 respondents; 35% patients, 50% caregivers, and 15% unknown. Of 49 proposed characteristics, 35 were reported as relevant by at least 25% (range: 7%-44%) of respondents. Patients and caregivers rated different characteristics as most important. Common characteristics included in the top 10 of both patients and caregivers were lack of motivation, change in being socially active, not able to finish things, and change in the level of irritation. No characteristics were reported missing by ≥5 respondents. Three categories of BPC were identified: (1) emotions, needs, and impulses (2) personality traits, and (3) poor judgement abilities.

The work resulted in a proposed definition for BPC in glioma patients, for which endorsement from the neuro-oncological community will be sought. A next step is to identify or develop an instrument to evaluate BPC in glioma patients.

Gliomas are rare, with a dismal outcome in terms of poor prognosis and an obvious negative impact on the patients’ functioning and well-being.1,2 Neurological, physical, and cognitive problems, as well as the occurrence of behavioral and personality changes (BPC), may disrupt the lives of both brain tumor patients and their relatives in a profound way, as these symptoms and impairments may have a negative impact on social, emotional, and psychological well-being,3,4 as well as the medical decision-making capacity of patients.5 A systematic review by our group assessing the prevalence of BPC in glioma patients showed that BPC are present in a substantial number of glioma patients, and are associated with distress and a lower level of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients and informal caregivers.6 However, BPC may mimic and partly overlap with delirium and dementia, with features that touch upon deficits in memory, thinking, and judgment, as well as clinical depression with symptoms such as apathy and loss of initiative.7

The systematic review performed by our group revealed that the reported prevalence rates of BPC varied from only 8% up to 67%,6 possibly due to the lack of a proper definition and understanding of the phenomenon. As such, an accurate prevalence of BPC in glioma patients is difficult to provide. It thus remains unclear how common the problem of BPC is in glioma patients, at which moment in the disease trajectory they occur, whether or not there is a relation with tumor location, and in which way BPC can be best measured and evaluated.6 Further research on the identification of characteristics that determine BPC in glioma patients is needed to propose a clear definition. Ultimately, this definition may help in selecting the right tool to measure BPC (eg, good content validity) and subsequently be used to assess BPC and gain a better understanding of this phenomenon.

In this study, we aimed to determine which characteristics of BPC are relevant for adult glioma patients, and subsequently propose a definition for BPC that can be used in further research.

Methods

Identification of Characteristics of BPC

Possible characteristics of BPC were extracted from the literature as identified in a previously conducted systematic review by our research group.6 The literature search for the systemic review was conducted using the following databases up to June 2014: PubMed/Medline, PsycINFO, Cochrane, CINAHL, and Embase. The search strategy consisted of 2 search strings, one related to “changes in personality and behavior” and one related to “primary brain tumors” (see Zwinkels et al6 for the full search string). For the current study, all articles that were initially screened for the systematic review were considered. Although not eligible for the systematic review, the excluded articles could describe characteristics and tools related to BPC, and therefore be relevant for this study.

During an orienting focus group meeting at the 12th European Association of Neuro-Oncology conference in Heidelberg (2016), health care professionals (HCPs) involved in the care of glioma patients and patient advocates—who are also former caregivers—of glioma patients discussed their ideas, experiences, and perceptions of the identified characteristics of BPC in glioma patients. BPCs were recognized as an important aspect of patients’ functioning and well-being and were considered a dynamic process rather than static. However, no immediate consensus could be reached on the characteristics that determine BPC in glioma patients. It was therefore suggested that both patients and their caregivers should indicate which characteristics are most important, as they were considered to be the best source to identify the most relevant aspects. Therefore, a questionnaire for patients and their (former) caregivers was developed to assess the relevance of the identified characteristics of BPC.

International Survey

The characteristics identified with the literature search were subsequently evaluated for their content, ie, the characteristics had to describe BPC and not a mere cognitive function, realizing that these are interlinked. The goal was to focus on those aspects/issues that are not captured with other instruments such as neurocognitive tests or HRQoL questionnaires. Next, the survey was constructed and presented to patients and (former) caregivers in an anonymous international online survey launched via the International Brain Tumour Alliance (IBTA). The survey, sent via SurveyMonkey, was announced to subscribers of the newsletter of the IBTA from September until December 2018, and only available in English (see Supplementary File 1). A privacy statement was included in the introductory text of the survey, and by continuing with the actual survey, all participants provided consent for using their data.

Participants were requested to complete 4 parts. First, participants had to indicate the relevance for each identified characteristic to the situation of the patient on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much.” Second, participants had to indicate which 3 characteristics had the most significant impact on their daily life/quality of life. Third, it was asked whether there were any characteristics missing in the previously shown list. Lastly, sociodemographic (ie, role [patient/caregiver], age, sex, and educational level) and clinical (tumor type and date of diagnosis) information was collected.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the results of the international survey. Means with their standard deviation were reported for continuous variables, and proportions for categorical variables. Characteristics that were rated as “quite a bit” or “very much” relevant were considered “relevant.”

Next, a cluster analysis was performed to identify associations between characteristics using Spearman correlations. The resulting network model was estimated using the Gaussian graphical model which estimates a network of partial correlation coefficients.8,9 Each link in the network model represents a partial correlation coefficient between 2 characteristics.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) and R10 with the qgraph package.9

Consensus Meeting

All obtained results with the international survey were subsequently discussed by a core group of experts with different backgrounds to identify categories of BPC characteristics relevant to adult glioma patients (step 1). The group existed of 5 HCPs with expertise in brain tumor patients, including 3 neuro-oncologists, 1 nurse practitioner in neuro-oncology, and a neuropsychologist, and was moderated by an independent researcher. As a starting point, the definition of BPC and its characteristics as used in the International Coding of Disease version 10, ICD-10, were used7: “An alteration of personality and behavior which can be residual or concomitant disorder of brain disease, damage or dysfunction” and “A disorder characterized by a significant alteration of the habitual patterns of behavior displayed by the subject pre-morbidly, involving the expression of emotions, needs and impulses. Impairment of cognitive and thought functions, and altered sexuality may also be part of the clinical picture.” As the results of the international survey were rather inconclusive, no consensus was reached on a definition for BPC in glioma patients. In a second step, existing biological and theoretical models11–13 were also considered and included in the final discussion (step 2), in which the definition of BPC in adult glioma patients was formulated. An example of a model is the personality model of Cloninger and the alternative five model of Zuckerman, referring to dimensions of temperaments (such as avoidance [neuroticism], approach [extraversion], and dishinhibition and constraint) which are thought to be biologically based. Results from research suggest that neurotransmitter systems, mainly differences in dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic levels, and different activation in specific brain regions, for example, the prefrontal cortex, are involved in differences in these temperaments. During this second extensive discussion, experts had to come to a consensus. Again, the discussion was moderated by an independent researcher.

Results

Identification of Characteristics

With the literature search, we identified 74 full-text eligible papers reporting on changed behavior, of which 18 reported on prevalence, and were therefore included in our systematic review on prevalence of BPC.6 Various reasons led to the exclusion of articles, most commonly because mixed brain tumor populations were included and results were not described separately for glioma patients, or because the prevalence of BPC was not reported clearly. Although not eligible for our systematic review, there were several articles identified during the screening that contained relevant information for this study. Indeed, 6 promising tools to identify BPC were found in these papers, ie, Frontal Systems Behavioral Scale (FrsBe), Overt Behavior Scale (OBS), the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI), Emotional and Social Dysfunction Questionnaire (ESDQ), and Ten-Item Personality Measurement (TIPI) (see Table 1 for an overview). A total of 75 characteristics were identified from these tools. Characteristics that were overlapping, multi-interpretable, or difficult to understand were excluded in consensus (H.Z., L.D., K.O.), resulting in a questionnaire with 49 items.

Overview of Measurement Tools That Have Been Used to Measure (Aspects of) Behavior and Personality Changes

| Tool . | Focus . |

|---|---|

| Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe)14 | Rating scale designed to measure behaviors associated with damage to the frontal lobes and frontal systems of the brain, including apathy, disinhibition, and executive dysfunction |

| Overt Behavior Scale (OBS)15 | Measures 9 categories of challenging behaviors among brain-damaged populations |

| Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI)16 | To investigate the neurobiological foundation for personality |

| ESDQ (Emotional and Social Dysfunction Questionnaire)17 | To measure emotional and social dysfunction in brain-damaged populations, by subscales such as emotional liability, indifference, and lack of insight |

| TIPI (Ten-Item Personality Inventory)18 | An instrument to measure personality traits in adults |

| Tool . | Focus . |

|---|---|

| Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe)14 | Rating scale designed to measure behaviors associated with damage to the frontal lobes and frontal systems of the brain, including apathy, disinhibition, and executive dysfunction |

| Overt Behavior Scale (OBS)15 | Measures 9 categories of challenging behaviors among brain-damaged populations |

| Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI)16 | To investigate the neurobiological foundation for personality |

| ESDQ (Emotional and Social Dysfunction Questionnaire)17 | To measure emotional and social dysfunction in brain-damaged populations, by subscales such as emotional liability, indifference, and lack of insight |

| TIPI (Ten-Item Personality Inventory)18 | An instrument to measure personality traits in adults |

Overview of Measurement Tools That Have Been Used to Measure (Aspects of) Behavior and Personality Changes

| Tool . | Focus . |

|---|---|

| Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe)14 | Rating scale designed to measure behaviors associated with damage to the frontal lobes and frontal systems of the brain, including apathy, disinhibition, and executive dysfunction |

| Overt Behavior Scale (OBS)15 | Measures 9 categories of challenging behaviors among brain-damaged populations |

| Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI)16 | To investigate the neurobiological foundation for personality |

| ESDQ (Emotional and Social Dysfunction Questionnaire)17 | To measure emotional and social dysfunction in brain-damaged populations, by subscales such as emotional liability, indifference, and lack of insight |

| TIPI (Ten-Item Personality Inventory)18 | An instrument to measure personality traits in adults |

| Tool . | Focus . |

|---|---|

| Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe)14 | Rating scale designed to measure behaviors associated with damage to the frontal lobes and frontal systems of the brain, including apathy, disinhibition, and executive dysfunction |

| Overt Behavior Scale (OBS)15 | Measures 9 categories of challenging behaviors among brain-damaged populations |

| Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI)16 | To investigate the neurobiological foundation for personality |

| ESDQ (Emotional and Social Dysfunction Questionnaire)17 | To measure emotional and social dysfunction in brain-damaged populations, by subscales such as emotional liability, indifference, and lack of insight |

| TIPI (Ten-Item Personality Inventory)18 | An instrument to measure personality traits in adults |

Respondents

Completed surveys were obtained from 140 respondents, of which 35% were patients, 50% caregivers, and for 15% the role was unknown. Most respondents came from the United Kingdom (41%), the United States (15%), or Australia (8%) were female (55%) and highly educated (54% had at least a bachelor’s degree). Most patients were reported to have grade II or IV glioma (29% vs 39%), although 17% of the respondents did not provide information on the tumor characteristics. As only 26% of the respondents provided information on the date of diagnosis, this data was not considered informative. See Table 2 for the characteristics of all 140 respondents. For those analyses comparing responses of patients and caregivers, only those respondents who identified their role were included (ie, 49 patients and 70 caregivers).

| Characteristics . | Respondents (n = 140) . |

|---|---|

| Role, no. (%) | |

| Patient | 49 (35%) |

| Caregiver | 38 (27%) |

| Former caregiver | 32 (23%) |

| Unknown | 21 (15%) |

| Relation to patient, no. (%) (n = 64/70 respondents) | |

| Partner | 38 (54%) |

| Sibling | 3 (4%) |

| Parent | 11 (16%) |

| Child | 9 (13%) |

| Other | 3 (4%) |

| Age in years, no. (%) (n = 72 respondents) | |

| Mean (SD) | 49 (13) |

| Gender, no. (%) | |

| Male | 43 (31%) |

| Female | 77 (55%) |

| Unknown | 20 (14%) |

| Educational level, no. (%) | |

| Primary school | 1 (1%) |

| Lower secondary school | 4 (3%) |

| Upper secondary school | 14 (10%) |

| Postsecondary, non-tertiary | 16 (11%) |

| Short cycle tertiary | 6 (4%) |

| Bachelor or equivalent | 41 (29%) |

| Master or equivalent | 28 (20%) |

| Doctoral or equivalent | 7 (5%) |

| Unknown | 23 (16%) |

| Country of residence, no. (%) | |

| United Kingdom | 57 (41%) |

| United States | 21 (15%) |

| Australia | 11 (8%) |

| the Netherlands | 11 (8%) |

| Sweden | 5 (4%) |

| Other | 14 (10%) |

| Unknown | 21 (15%) |

| WHO grade glioma, no. (%) | |

| Grade II | 41 (29%) |

| Grade III | 21 (15%) |

| Grade IV | 54 (39%) |

| Unknown | 24 (17%) |

| Characteristics . | Respondents (n = 140) . |

|---|---|

| Role, no. (%) | |

| Patient | 49 (35%) |

| Caregiver | 38 (27%) |

| Former caregiver | 32 (23%) |

| Unknown | 21 (15%) |

| Relation to patient, no. (%) (n = 64/70 respondents) | |

| Partner | 38 (54%) |

| Sibling | 3 (4%) |

| Parent | 11 (16%) |

| Child | 9 (13%) |

| Other | 3 (4%) |

| Age in years, no. (%) (n = 72 respondents) | |

| Mean (SD) | 49 (13) |

| Gender, no. (%) | |

| Male | 43 (31%) |

| Female | 77 (55%) |

| Unknown | 20 (14%) |

| Educational level, no. (%) | |

| Primary school | 1 (1%) |

| Lower secondary school | 4 (3%) |

| Upper secondary school | 14 (10%) |

| Postsecondary, non-tertiary | 16 (11%) |

| Short cycle tertiary | 6 (4%) |

| Bachelor or equivalent | 41 (29%) |

| Master or equivalent | 28 (20%) |

| Doctoral or equivalent | 7 (5%) |

| Unknown | 23 (16%) |

| Country of residence, no. (%) | |

| United Kingdom | 57 (41%) |

| United States | 21 (15%) |

| Australia | 11 (8%) |

| the Netherlands | 11 (8%) |

| Sweden | 5 (4%) |

| Other | 14 (10%) |

| Unknown | 21 (15%) |

| WHO grade glioma, no. (%) | |

| Grade II | 41 (29%) |

| Grade III | 21 (15%) |

| Grade IV | 54 (39%) |

| Unknown | 24 (17%) |

| Characteristics . | Respondents (n = 140) . |

|---|---|

| Role, no. (%) | |

| Patient | 49 (35%) |

| Caregiver | 38 (27%) |

| Former caregiver | 32 (23%) |

| Unknown | 21 (15%) |

| Relation to patient, no. (%) (n = 64/70 respondents) | |

| Partner | 38 (54%) |

| Sibling | 3 (4%) |

| Parent | 11 (16%) |

| Child | 9 (13%) |

| Other | 3 (4%) |

| Age in years, no. (%) (n = 72 respondents) | |

| Mean (SD) | 49 (13) |

| Gender, no. (%) | |

| Male | 43 (31%) |

| Female | 77 (55%) |

| Unknown | 20 (14%) |

| Educational level, no. (%) | |

| Primary school | 1 (1%) |

| Lower secondary school | 4 (3%) |

| Upper secondary school | 14 (10%) |

| Postsecondary, non-tertiary | 16 (11%) |

| Short cycle tertiary | 6 (4%) |

| Bachelor or equivalent | 41 (29%) |

| Master or equivalent | 28 (20%) |

| Doctoral or equivalent | 7 (5%) |

| Unknown | 23 (16%) |

| Country of residence, no. (%) | |

| United Kingdom | 57 (41%) |

| United States | 21 (15%) |

| Australia | 11 (8%) |

| the Netherlands | 11 (8%) |

| Sweden | 5 (4%) |

| Other | 14 (10%) |

| Unknown | 21 (15%) |

| WHO grade glioma, no. (%) | |

| Grade II | 41 (29%) |

| Grade III | 21 (15%) |

| Grade IV | 54 (39%) |

| Unknown | 24 (17%) |

| Characteristics . | Respondents (n = 140) . |

|---|---|

| Role, no. (%) | |

| Patient | 49 (35%) |

| Caregiver | 38 (27%) |

| Former caregiver | 32 (23%) |

| Unknown | 21 (15%) |

| Relation to patient, no. (%) (n = 64/70 respondents) | |

| Partner | 38 (54%) |

| Sibling | 3 (4%) |

| Parent | 11 (16%) |

| Child | 9 (13%) |

| Other | 3 (4%) |

| Age in years, no. (%) (n = 72 respondents) | |

| Mean (SD) | 49 (13) |

| Gender, no. (%) | |

| Male | 43 (31%) |

| Female | 77 (55%) |

| Unknown | 20 (14%) |

| Educational level, no. (%) | |

| Primary school | 1 (1%) |

| Lower secondary school | 4 (3%) |

| Upper secondary school | 14 (10%) |

| Postsecondary, non-tertiary | 16 (11%) |

| Short cycle tertiary | 6 (4%) |

| Bachelor or equivalent | 41 (29%) |

| Master or equivalent | 28 (20%) |

| Doctoral or equivalent | 7 (5%) |

| Unknown | 23 (16%) |

| Country of residence, no. (%) | |

| United Kingdom | 57 (41%) |

| United States | 21 (15%) |

| Australia | 11 (8%) |

| the Netherlands | 11 (8%) |

| Sweden | 5 (4%) |

| Other | 14 (10%) |

| Unknown | 21 (15%) |

| WHO grade glioma, no. (%) | |

| Grade II | 41 (29%) |

| Grade III | 21 (15%) |

| Grade IV | 54 (39%) |

| Unknown | 24 (17%) |

Results Survey

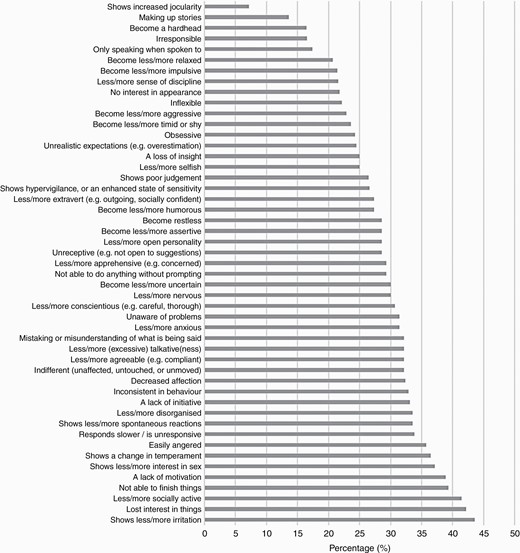

Of the 49 proposed characteristics of BPC, 35 were reported as relevant by at least 25% (range: 7%-44%) of the respondents (Figure 1). The 5 most frequently reported (>30%) characteristics were: shows less/more irritation (61/140, 44%), lost interest in things (41/140, 42%), less/more socially active (58/140, 41%), not able to finish things (55/140, 39%), and a lack of motivation (54/139, 39%). When analyzing the results for patients (n = 50) and caregivers (n = 70) separately, it was found that there was a difference in characteristics that were considered most often relevant (Table 3).

Most Frequently Mentioned Characteristics (Number and Percentage), as Reported by Patients and Caregivers

| . | Patients (n = 50) . | Caregivers (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Less/more socially active (22/49, 45%) | Unaware of problems (35/70, 50%) |

| 2 | Shows less/more interest in sex (18/47, 38%) | Shows less/more irritation (33/70, 47%) |

| 3 | Less/more anxious (18/49, 37%) | Mistaking or misunderstanding what is being said (33/70, 47%) |

| 4 | Not able to finish things (17/49, 35%) | A lack of motivation (31/69, 45%) |

| 5 | Lost interest in things (17/49, 35%) | Lost interest in things (31/70, 44%) |

| 6 | Shows less/more irritation (17/49, 35%) | Shows a change in temperament (31/70, 44%) |

| 7 | Easily angered (16/49, 33%) | Not able to finish things (30/70, 43%) |

| 8 | Less/more nervous (16/49, 33%) | Indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved) (30/70, 43%) |

| 9 | A lack of motivation (15/49, 31%) | Inconsistent in behavior (30/70, 43%) |

| 10 | Shows a change in temperament (14/49, 29%) | A lack of initiative (29/69, 42%) |

| . | Patients (n = 50) . | Caregivers (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Less/more socially active (22/49, 45%) | Unaware of problems (35/70, 50%) |

| 2 | Shows less/more interest in sex (18/47, 38%) | Shows less/more irritation (33/70, 47%) |

| 3 | Less/more anxious (18/49, 37%) | Mistaking or misunderstanding what is being said (33/70, 47%) |

| 4 | Not able to finish things (17/49, 35%) | A lack of motivation (31/69, 45%) |

| 5 | Lost interest in things (17/49, 35%) | Lost interest in things (31/70, 44%) |

| 6 | Shows less/more irritation (17/49, 35%) | Shows a change in temperament (31/70, 44%) |

| 7 | Easily angered (16/49, 33%) | Not able to finish things (30/70, 43%) |

| 8 | Less/more nervous (16/49, 33%) | Indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved) (30/70, 43%) |

| 9 | A lack of motivation (15/49, 31%) | Inconsistent in behavior (30/70, 43%) |

| 10 | Shows a change in temperament (14/49, 29%) | A lack of initiative (29/69, 42%) |

Of note: for 21 respondents the role is unknown, so these are not included in the results. The italic characteristics highlight those that are mentioned by both patients and caregivers.

Most Frequently Mentioned Characteristics (Number and Percentage), as Reported by Patients and Caregivers

| . | Patients (n = 50) . | Caregivers (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Less/more socially active (22/49, 45%) | Unaware of problems (35/70, 50%) |

| 2 | Shows less/more interest in sex (18/47, 38%) | Shows less/more irritation (33/70, 47%) |

| 3 | Less/more anxious (18/49, 37%) | Mistaking or misunderstanding what is being said (33/70, 47%) |

| 4 | Not able to finish things (17/49, 35%) | A lack of motivation (31/69, 45%) |

| 5 | Lost interest in things (17/49, 35%) | Lost interest in things (31/70, 44%) |

| 6 | Shows less/more irritation (17/49, 35%) | Shows a change in temperament (31/70, 44%) |

| 7 | Easily angered (16/49, 33%) | Not able to finish things (30/70, 43%) |

| 8 | Less/more nervous (16/49, 33%) | Indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved) (30/70, 43%) |

| 9 | A lack of motivation (15/49, 31%) | Inconsistent in behavior (30/70, 43%) |

| 10 | Shows a change in temperament (14/49, 29%) | A lack of initiative (29/69, 42%) |

| . | Patients (n = 50) . | Caregivers (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Less/more socially active (22/49, 45%) | Unaware of problems (35/70, 50%) |

| 2 | Shows less/more interest in sex (18/47, 38%) | Shows less/more irritation (33/70, 47%) |

| 3 | Less/more anxious (18/49, 37%) | Mistaking or misunderstanding what is being said (33/70, 47%) |

| 4 | Not able to finish things (17/49, 35%) | A lack of motivation (31/69, 45%) |

| 5 | Lost interest in things (17/49, 35%) | Lost interest in things (31/70, 44%) |

| 6 | Shows less/more irritation (17/49, 35%) | Shows a change in temperament (31/70, 44%) |

| 7 | Easily angered (16/49, 33%) | Not able to finish things (30/70, 43%) |

| 8 | Less/more nervous (16/49, 33%) | Indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved) (30/70, 43%) |

| 9 | A lack of motivation (15/49, 31%) | Inconsistent in behavior (30/70, 43%) |

| 10 | Shows a change in temperament (14/49, 29%) | A lack of initiative (29/69, 42%) |

Of note: for 21 respondents the role is unknown, so these are not included in the results. The italic characteristics highlight those that are mentioned by both patients and caregivers.

Overview of the percentage of all 140 respondents that rated a specific characteristic as very relevant (scored as “Quite a bit” or “Very much”).

The 10 characteristics with the most impact on daily life, based on the 140 respondents, were: lack of motivation (n = 32), less/more anxious (n = 21), a lack of initiative (n = 17), not able to finish things (n = 17), indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved) (n = 17), less/more socially active (n = 17), shows less/more irritation (n = 17), decreased affection (n = 16), lost interest in things (n = 16), and mistaking or misunderstanding of what is being said (n = 16). Again, patients and caregivers differed in their opinion on which characteristics had most impact on daily life/quality of life (Table 4).

Top 10 of the Top 3 Characteristics With the Most Impact, as Reported by Patients and Caregivers

| . | Patients (n = 50) . | Caregivers (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A lack of motivation (n = 15) | Indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved) (n = 14) |

| 2 | Shows less/more interest in sex (n = 11) | Decreased affection (n = 13) |

| 3 | Not able to finish things (n = 9) | Unaware of problems (n = 13) |

| 4 | Easily angered (n = 9) | A lack of motivation (n = 12) |

| 5 | Less/more anxious (n = 9) | Mistaking or misunderstanding of what is being said (n = 12) |

| 6 | Responds slower/is unresponsive (n = 7) | Easily angered (n = 11) |

| 7 | Less/more socially active (n = 7) | A lack of initiative (n = 8) |

| 8 | Lost interest in things (n = 7) | Less/more anxious (n = 8) |

| 9 | Shows hypervigilance, or an enhanced state of sensitivity (n = 7) | Less/more socially active (n = 7) |

| 10 | Shows less/more irritation (n = 7) | Become less/more impulsive (n = 7) |

| 11 | Less/more disorganized (n = 7) | Obsessive (n = 7) |

| 12 | — | Shows more/less irritation (n = 7) |

| . | Patients (n = 50) . | Caregivers (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A lack of motivation (n = 15) | Indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved) (n = 14) |

| 2 | Shows less/more interest in sex (n = 11) | Decreased affection (n = 13) |

| 3 | Not able to finish things (n = 9) | Unaware of problems (n = 13) |

| 4 | Easily angered (n = 9) | A lack of motivation (n = 12) |

| 5 | Less/more anxious (n = 9) | Mistaking or misunderstanding of what is being said (n = 12) |

| 6 | Responds slower/is unresponsive (n = 7) | Easily angered (n = 11) |

| 7 | Less/more socially active (n = 7) | A lack of initiative (n = 8) |

| 8 | Lost interest in things (n = 7) | Less/more anxious (n = 8) |

| 9 | Shows hypervigilance, or an enhanced state of sensitivity (n = 7) | Less/more socially active (n = 7) |

| 10 | Shows less/more irritation (n = 7) | Become less/more impulsive (n = 7) |

| 11 | Less/more disorganized (n = 7) | Obsessive (n = 7) |

| 12 | — | Shows more/less irritation (n = 7) |

Of note: for 21 respondents the role is unknown, so these are not included in the results. The italic characteristics highlight those that are mentioned by both patients and caregivers.

Top 10 of the Top 3 Characteristics With the Most Impact, as Reported by Patients and Caregivers

| . | Patients (n = 50) . | Caregivers (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A lack of motivation (n = 15) | Indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved) (n = 14) |

| 2 | Shows less/more interest in sex (n = 11) | Decreased affection (n = 13) |

| 3 | Not able to finish things (n = 9) | Unaware of problems (n = 13) |

| 4 | Easily angered (n = 9) | A lack of motivation (n = 12) |

| 5 | Less/more anxious (n = 9) | Mistaking or misunderstanding of what is being said (n = 12) |

| 6 | Responds slower/is unresponsive (n = 7) | Easily angered (n = 11) |

| 7 | Less/more socially active (n = 7) | A lack of initiative (n = 8) |

| 8 | Lost interest in things (n = 7) | Less/more anxious (n = 8) |

| 9 | Shows hypervigilance, or an enhanced state of sensitivity (n = 7) | Less/more socially active (n = 7) |

| 10 | Shows less/more irritation (n = 7) | Become less/more impulsive (n = 7) |

| 11 | Less/more disorganized (n = 7) | Obsessive (n = 7) |

| 12 | — | Shows more/less irritation (n = 7) |

| . | Patients (n = 50) . | Caregivers (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A lack of motivation (n = 15) | Indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved) (n = 14) |

| 2 | Shows less/more interest in sex (n = 11) | Decreased affection (n = 13) |

| 3 | Not able to finish things (n = 9) | Unaware of problems (n = 13) |

| 4 | Easily angered (n = 9) | A lack of motivation (n = 12) |

| 5 | Less/more anxious (n = 9) | Mistaking or misunderstanding of what is being said (n = 12) |

| 6 | Responds slower/is unresponsive (n = 7) | Easily angered (n = 11) |

| 7 | Less/more socially active (n = 7) | A lack of initiative (n = 8) |

| 8 | Lost interest in things (n = 7) | Less/more anxious (n = 8) |

| 9 | Shows hypervigilance, or an enhanced state of sensitivity (n = 7) | Less/more socially active (n = 7) |

| 10 | Shows less/more irritation (n = 7) | Become less/more impulsive (n = 7) |

| 11 | Less/more disorganized (n = 7) | Obsessive (n = 7) |

| 12 | — | Shows more/less irritation (n = 7) |

Of note: for 21 respondents the role is unknown, so these are not included in the results. The italic characteristics highlight those that are mentioned by both patients and caregivers.

When combining the characteristics that were most frequently mentioned as being relevant, and had the most impact on daily life, 4 characteristics were maintained: lack of motivation, less/more socially active, not able to finish things, and shows less/more irritation. There were no characteristics reported to be missing by ≥5 respondents.

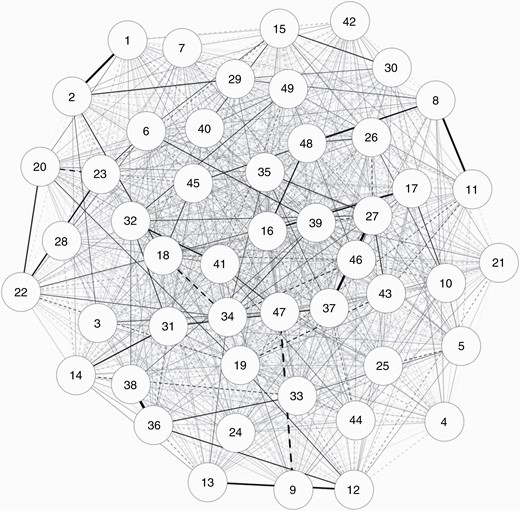

The network analysis (Figure 2) showed that many characteristics were negatively or positively correlated, and did not reveal any definite categories of characteristics.

Spearman correlation matrix of the 49 identified characteristics. Thicker and darker lines represent stronger partial correlations. Solid and dotted lines represent positive and negative correlations, respectively. The position of the numbers relative to each other represents the closeness between characteristics.

1 = a lack of initiative; 2 = a lack of motivation; 3 = not able to finish things; 4 = indifferent (unaffected, untouched, or unmoved); 5 = unreceptive (eg, not open to suggestions); 6 = shows less/more spontaneous reactions; 7 = responds slower/is unresponsive; 8 = decreased affection; 9 = no interest in appearance; 10 = shows less/more interest in sex; 11 = become less/more humorous; 12 = become less/more timid or shy; 13 = less/more open personality; 14 = less/more sense of discipline; 15 = less/more agreeable (eg, compliant); 16 = less/more conscientious (eg, careful, thorough); 17 = less/more socially active; 18 = lost interest in things; 19 = become less/more assertive; 20 = not able to do anything without prompting; 21 = irresponsible; 22 = only speaking when spoken to; 23 = become less/more impulsive; 24 = shows a change in temperament; 25 = less/more extravert (eg, outgoing, socially confident); 26 = unrealistic expectations (eg, overestimation); 27 = easily angered; 28 = less/more (excessive) talkative(ness); 29 = shows hypervigilance, or an enhanced state of sensitivity; 30 = shows increased jocularity; 31 = less/more selfish; 32 = less/more apprehensive (eg, concerned); 33 = obsessive; 34 = become restless; 35 = shows less/more irritation; 36 = less/more nervous; 37 = become less/more aggressive; 38 = less/more anxious; 39 = become less/more relaxed; 40 = shows poor judgement; 41 = unaware of problems; 42 = mistaking or misunderstanding of what is being said; 43 = making up stories; 44 = less/more disorganized; 45 = inconsistent in behavior; 46 = inflexible; 47 = a loss of insight; 48 = become a hardhead; 49 = become less/more uncertain.

Consensus Meeting

The results of the analysis of the survey were discussed in a 2-step procedure by a group of experts consisting of 3 neuro-oncologists (J.A.F.K., M.J.V., M.J.B.T.), 1 nurse practitioner (H.Z.), and 1 neuropsychologist (E.J.J.H.), all with ample experience in the treatment of glioma patients. More specifically, the experts were provided with information on the relevance of each characteristic (ie, percentage of respondents who reported the characteristic as “quite a bit” or “very much” relevant), and which items were in the top 10 of items with the most impact. These results were presented on group level (all respondents), as well as separately for patients and caregivers, and overlap between the groups was also presented. Lastly, the results of the cluster analysis were shown to the experts. The experts agreed that none of the analyses clearly attributed to the identification of the most relevant characteristics of BPC in brain tumor patients, which can subsequently be included in a definition of BPC. They agreed, however, that it was important to also include the ratings of the caregivers, as patients may fail to identify certain aspects due to a lack of judgement or insight. Also, they recognized that too many characteristics were deemed relevant and important to be included in the definition, and that categorization of characteristics was required. For this, existing theoretical models were presented and discussed during a second meeting. Categorization of the 49 characteristics was based on their content and resulted in 3 proposed main categories, that were subsequently presented to the whole study team for evaluation. These procedures resulted in the following definition of BPC in glioma patients: “An alteration of personality and behavior, which can be caused by a glioma and/or its treatment, and may vary in severity, frequency and magnitude during the disease process. This alteration of personality and behavior comprises significant changes in (1) emotions, needs and impulses such as loss of emotional control, decreased motivation or initiative, and indifference, (2) changes in personality traits such as being more selfish, obsessive, or inflexible, and (3) poor judgement abilities.”

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to identify characteristics of BPC in adult glioma patients which could be used to formulate a definition for BPC. These characteristics were identified by means of a web-based questionnaire for patients and their (former) caregivers, as they were considered the best source to identify the most relevant aspects. The results of the international survey showed that the majority (71%) of the characteristics were deemed relevant by at least 25% of respondents, and that characteristics perceived as relevant and important differed between patients and caregivers. The characteristics that were considered relevant and important by both patients and (former) caregivers were lack of motivation, change in social activities, not able to finish things, and change in the level of irritation. During a consensus meeting with experts, relevant characteristics were discussed and categorized based on clinical, biological, and theoretical models. Although arbitrary, this resulted in 3 categories that were subsequently included in the definition of BPC: (1) change in emotions, needs, and impulses such as loss of emotional control, decreased motivation or initiative, and indifference, (2) changes in personality traits such as being more selfish, obsessive, or inflexible, and (3) poor judgement abilities.

Qualitative studies showed that changes in emotions, needs, and impulses in glioma patients, reflecting changes in personality traits, are well recognized by patients and caregivers.19–21 Also, poor judgement abilities are frequently reported. In quantitative studies on BPC in brain tumor patients, different measurement tools for BPC were used, addressing different aspects of behavior and/or personality. To date, none of these tools are validated for brain tumor patients. Also, the instruments do not seem to cover all aspects of BPC that are relevant for brain tumor patients as identified with this study. Another difficulty is that these tools do not properly distinguish between characteristics of BPC and cognitive disturbances, dementia, or depression. Adaptation of an existing instrument or the development of a new instrument to measure BPC in glioma patients, therefore, seems necessary, but further research into the content validity of the instruments is needed.

The need for a good instrument to measure BPC in glioma patients is emphasized by the lack of knowledge on the frequency and timing of occurrence of BPC in this patient population. It is currently unclear if BPC are already present at diagnosis, and if certain aspects worsen or improve during the disease trajectory, although some authors quantified an increase in BPC during the disease trajectory and in the end-of-life phase.22,23 Moreover, it is unclear whether there are interventions that could be used to modify aspects of BPC. If an appropriate measurement tool would be available, subsequent research is needed to obtain information on these knowledge gaps. It is important though, that BPC should not only be evaluated by glioma patients themselves (ie, patient-reported), but also by their caregivers (ie, observer-reported). This seems necessary because we found that patients and caregivers have different perceptions of changes in certain aspects of BPC. However, before we can start to select, adapt, or develop a tool to measure BPC in glioma patients, consensus on the definition of BPC within the brain tumor community is needed.

This study has several limitations. First, we used articles identified with the search for the systematic literature,6 conducted in 2014, to extract the characteristics of BPC in glioma patients. For this study, we also did not systematically record which articles from the original search were eligible for this study, hampering reproducibility. Although unlikely, as we identified 49 characteristics and the respondents did not identify additional characteristics in the survey, it may be that new characteristics of BPC for glioma patients are proposed in more recent studies that were not covered by the current search. Second, the survey was launched via the newsletter of the IBTA, therefore English-speaking patients and (former) caregivers with access to the internet and interest in obtaining information about brain tumors were more likely to respond, resulting in selection bias. These results may therefore not be completely generalizable to the entire glioma population. Also, as this was an anonymized survey, we were not able to verify the role of the respondent or clinical characteristics such as tumor type, which may have resulted in biased results. One of the difficulties with interpreting the results of the survey was that 35 out of the 49 characteristics (71%) were reported as relevant by at least 25% of respondents, indicating that BPC are multifaceted and that many characteristics contribute to BPC in this patient population. Although it was tried to distinguish BPC from pure cognitive functions, overlap may exist. The consequence is that formulation of a definition for BPC in glioma patients is not straightforward and may continue to result in the discussion. Since the definition of BPC has been an arbitrary process (not data-driven), it is of utmost importance to reach a consensus on this definition in the entire neuro-oncological community. In future steps, it is also important to include a patient or patient representative, to gain their perspective on the proposed definition. However, to quantify BPC problems in glioma patients, a definition is needed and instruments should be selected accordingly. It should be recognized though, that the concept of BPC may be subject to change in the future, when new insights arise, which also has consequences for the way BPC are assessed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed that BPC are multifaceted and that formulation of a definition for BPC in glioma patients is not straightforward. To provide a framework for future research on this topic, we have proposed a definition of BPC in adult glioma patients based on the work done so far: “An alteration of personality and behavior, which can be caused by a glioma and/or its treatment, and may vary in severity, frequency and magnitude during the disease process. This alteration of personality and behavior comprises significant changes in (1) emotions, needs and impulses such as loss of emotional control, decreased motivation or initiative, and indifference, (2) changes in personality traits such as being more selfish, obsessive, or inflexible, and (3) poor judgement abilities.” A next step would be to ask for feedback from the neuro-oncological community on the proposed definition through the associations of neuro-oncology (SNO [Society for Neuro-Oncology], EANO [European Association of Neuro-Oncology], ASNO [Asian Society for Neuro-Oncology]) worldwide, and reach consensus. Subsequently, further research can be conducted with the goal to select or develop a measurement tool and measure BPC in the glioma patient population. Ultimately, studies could determine the extent of BPC in glioma patients as well as its impact on aspects of HRQoL of both the patient and their relatives. In clinical practice, monitoring BPC over time could help to timely identify issues and introduce pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions, if available and considered needed.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed to the design and concept of this article. All authors critically revised the article and gave final approval for the version to be published.

Funding

No funding was available for this study.

Conflict of interest statement. None of the authors declares a conflict of interest.