-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Akanksha Sharma, Justin Low, Maciej M Mrugala, Neuro-oncologists have spoken – the role of bevacizumab in the inpatient setting. A clinical and economic conundrum, Neuro-Oncology Practice, Volume 6, Issue 1, February 2019, Pages 30–36, https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npy011

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key player in tumor angiogenesis. The drug can halt tumor progression, treat radiation necrosis, and reduce peritumoral edema. Although it does not increase overall survival, bevacizumab can improve progression-free survival and quality of life. In many countries, bevacizumab use in the inpatient setting is restricted due to its significant cost. Here, we explore attitudes towards the use of bevacizumab amidst practitioners treating brain tumors and assess ease of accessing the drug in the inpatient setting.

A 10-question survey querying practitioners’ opinions of inpatient bevacizumab utility and its availability was distributed to the membership of the Society of Neuro-Oncology in July 2016.

Eighty-seven percent felt that there was a role for bevacizumab in the inpatient setting, and 69% reported favorable experiences with bevacizumab use. However, 40% encountered difficulty in obtaining approval for inpatient use. We present two contrasting clinical cases that highlight favorable and unfavorable outcomes when bevacizumab use was and was not permitted, respectively.

In this sample of neuro-oncology practitioners, there is general consensus that bevacizumab plays an important role in the inpatient treatment of brain tumors. In light of ongoing barriers to inpatient bevacizumab use due to cost concerns, these data motivate the creation of standardized policies for inpatient bevacizumab use that balances its important role in improving quality of life with financial considerations.

Bevacizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), a key component of tumor survival and spread.1 Bevacizumab is used in the treatment of a variety of solid systemic cancers and was approved for the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma in May 2009.2,3 While it does not improve overall survival, bevacizumab does improve progression-free survival, and may maintain or improve performance status and quality of life in patients with high-grade gliomas.4–6 Bevacizumab is also useful in the therapy of radiation necrosis, a treatment complication whereby therapeutic radiation results in VEGF- and cytokine-mediated blood-brain barrier disruption and endothelial damage.7–9 A recent comprehensive analysis of patients with radiation necrosis reported significant clinical (91%) and radiographic (98%) improvement with bevacizumab treatment.10–13

Despite its important role in treating brain cancers and radiation necrosis, the high cost of bevacizumab has limited its availability.14 A vial of 100 mg of bevacizumab has a price of around $680 in the United States and £243 in the United Kingdom.15 For a typical 70 kg individual, the cost for a single 5–10 mg/kg infusion can range between $3500-$5000, not accounting for ancillary costs. The cost for 4 to 6 cycles (one cycle equating to 2 doses or one month in most systems), which is a reasonable average for a patient with high-grade glioma, can vary by country but is estimated to be quite high. In the United States this would be closer to $30000. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service does not fund the drug due to estimated costs of £21000 a year.16 In the United States, the cost ranges from $50000 to $100000 per year, depending on the type of cancer.14 In glioblastoma, cost effectiveness analyses estimate a cost of nearly $60000 per life year gained.17 For many public health systems, this cost is considered to be too high for the limited survival benefit.17–19

Few studies have analyzed the cost effectiveness of bevacizumab for the treatment of cerebral radiation necrosis. Lubelski et al calculated that bevacizumab would need to result in a 2.4-month survival increase or a 20% improvement in quality of life in order to be cost effective for the treatment of radiation necrosis.20 Due to insurance reimbursement policies, bevacizumab usage is often restricted to the outpatient setting. However, in many cases patients present with sequelae of radiation necrosis that is severe enough to require inpatient admission. Patients with progressive gliomas who develop steroid-resistant vasogenic edema also frequently present acutely to the emergency department and need inpatient admission. While historically such patients were treated with high doses of steroids, bevacizumab is increasingly favored due to its rapid effectiveness and reduced side effect profile when compared to steroids.21 A small retrospective study found that patients with glioblastoma who were treated with a single dose of bevacizumab while admitted for severe neurological deterioration could resume outpatient therapy with significant reduction in steroid requirements.22

In this work, we survey the experiences and attitudes of neuro-oncology practitioners towards the inpatient use of bevacizumab, with a focus on its availability and presumed utility. We also share two illustrative cases – one where bevacizumab treatment was approved for inpatient use and another where it was denied – to illustrate differences in patient outcomes and cost.

Methods

Study Population

The active membership of the Society of Neuro-Oncology (SNO) includes clinicians, basic scientists, nurses, and other health care professionals with background and expertise in fields that include epidemiology, medical oncology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, pathology, pediatrics, psychology, radiology, and radiation oncology. We designed a prospective survey to assess the experience and attitude towards inpatient use of bevacizumab. An email with a link to an online survey hosted on SurveyMonkey was sent to the entire membership through a listserv. No identifying information was collected in this survey. Consent to participate in the study was implied by completing the survey.

Study Measures

The survey consisted of 10 questions investigating respondents’ opinions on the inpatient use of bevacizumab and their experience in using the drug in their practice. An Institutional Review Board (IRB) review was not necessary given the nature of the project and local IRB requirements.

Case Examples

We reviewed two cases of high-grade glioma from our institution. The cases were chosen to illustrate our experience of accessing bevacizumab in the inpatient setting.

Results

A total of 105 members responded to the survey, at a time when the membership of SNO was estimated to be 1996, resulting in a response rate of 5.6%. Respondents were primarily neuro-oncologists (67%) and neurosurgeons (16%), practicing at mainly academic institutions (82%) from 10 different countries (Table 1).

| . | Number . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| Specialty | ||

| Neuro-Oncologist | 70 | 66.6% |

| Neurosurgeon | 17 | 16.2% |

| Radiation Oncologist | 5 | 4.8% |

| Nurse Practitioner | 3 | 2.8% |

| Pediatric Neuro-Oncologist | 5 | 4.8% |

| Other* | 5 | 4.8% |

| Practice Setting | ||

| Academic Institution | 86 | 81.9% |

| Private Practice with Hospital Affiliation | 13 | 12.4% |

| Government Hospital | 7 | 6.7% |

| Is there a role for inpatient use of bevacizumab? | ||

| Yes | 91 | 86.7% |

| No | 14 | 13.3% |

| How often do you use bevacizumab in the inpatient setting? | ||

| Never | 21 | 20% |

| 1–3 times per week | 4 | 3.8% |

| 1–3 times per month | 18 | 17.1% |

| 1–3 times per year | 48 | 45.7% |

| Other† | 14 | 13.4% |

| Do you have difficulty getting bevacizumab approved for inpatient use? | ||

| Yes | 42 | 40% |

| No | 59 | 56.2% |

| No answer | 4 | 3.8% |

| Does your hospital have special procedures in place to approve use of bevacizumab in the inpatient setting? | ||

| Yes | 25 | 23.8% |

| No | 56 | 53.3% |

| Not sure | 24 | 22.9% |

| In the last 12 months has inpatient use of bevacizumab been declined by your hospital? | ||

| Yes | 19 | 18.1% |

| No | 82 | 78.1% |

| No answer | 4 | 3.8% |

| In cases where you used bevacizumab in the inpatient setting was the patient’s outcome favorable? | ||

| Yes | 72 | 68.6% |

| No | 15 | 14.3% |

| No answer | 18 | 17.1% |

| In cases where you initiated bevacizumab in the inpatient setting, were you able to continue the medication outpatient? | ||

| Yes | 81 | 77.1% |

| No | 11 | 10.5% |

| No answer | 13 | 12.4% |

| Do you include considerations about the cost effectiveness of bevacizumab when you offer treatment plans to patients? | ||

| No - if I think it could result in improvement, I offer it as a treatment option | 48 | 45.7% |

| Yes - but only if the patient is underinsured or uninsured and the expenses would be prohibitive | 12 | 11.4% |

| Yes - if I think the cost-benefit ratio is not favorable, I do not offer it as a treatment option at all | 12 | 11.4% |

| Yes - but I still offer it as a treatment option and defer decision to patient | 30 | 28.6% |

| No answer | 3 | 2.9% |

| . | Number . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| Specialty | ||

| Neuro-Oncologist | 70 | 66.6% |

| Neurosurgeon | 17 | 16.2% |

| Radiation Oncologist | 5 | 4.8% |

| Nurse Practitioner | 3 | 2.8% |

| Pediatric Neuro-Oncologist | 5 | 4.8% |

| Other* | 5 | 4.8% |

| Practice Setting | ||

| Academic Institution | 86 | 81.9% |

| Private Practice with Hospital Affiliation | 13 | 12.4% |

| Government Hospital | 7 | 6.7% |

| Is there a role for inpatient use of bevacizumab? | ||

| Yes | 91 | 86.7% |

| No | 14 | 13.3% |

| How often do you use bevacizumab in the inpatient setting? | ||

| Never | 21 | 20% |

| 1–3 times per week | 4 | 3.8% |

| 1–3 times per month | 18 | 17.1% |

| 1–3 times per year | 48 | 45.7% |

| Other† | 14 | 13.4% |

| Do you have difficulty getting bevacizumab approved for inpatient use? | ||

| Yes | 42 | 40% |

| No | 59 | 56.2% |

| No answer | 4 | 3.8% |

| Does your hospital have special procedures in place to approve use of bevacizumab in the inpatient setting? | ||

| Yes | 25 | 23.8% |

| No | 56 | 53.3% |

| Not sure | 24 | 22.9% |

| In the last 12 months has inpatient use of bevacizumab been declined by your hospital? | ||

| Yes | 19 | 18.1% |

| No | 82 | 78.1% |

| No answer | 4 | 3.8% |

| In cases where you used bevacizumab in the inpatient setting was the patient’s outcome favorable? | ||

| Yes | 72 | 68.6% |

| No | 15 | 14.3% |

| No answer | 18 | 17.1% |

| In cases where you initiated bevacizumab in the inpatient setting, were you able to continue the medication outpatient? | ||

| Yes | 81 | 77.1% |

| No | 11 | 10.5% |

| No answer | 13 | 12.4% |

| Do you include considerations about the cost effectiveness of bevacizumab when you offer treatment plans to patients? | ||

| No - if I think it could result in improvement, I offer it as a treatment option | 48 | 45.7% |

| Yes - but only if the patient is underinsured or uninsured and the expenses would be prohibitive | 12 | 11.4% |

| Yes - if I think the cost-benefit ratio is not favorable, I do not offer it as a treatment option at all | 12 | 11.4% |

| Yes - but I still offer it as a treatment option and defer decision to patient | 30 | 28.6% |

| No answer | 3 | 2.9% |

*Included nurses and medical oncologists

†Included “rarely,” once every few years, or “when indicated.”

| . | Number . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| Specialty | ||

| Neuro-Oncologist | 70 | 66.6% |

| Neurosurgeon | 17 | 16.2% |

| Radiation Oncologist | 5 | 4.8% |

| Nurse Practitioner | 3 | 2.8% |

| Pediatric Neuro-Oncologist | 5 | 4.8% |

| Other* | 5 | 4.8% |

| Practice Setting | ||

| Academic Institution | 86 | 81.9% |

| Private Practice with Hospital Affiliation | 13 | 12.4% |

| Government Hospital | 7 | 6.7% |

| Is there a role for inpatient use of bevacizumab? | ||

| Yes | 91 | 86.7% |

| No | 14 | 13.3% |

| How often do you use bevacizumab in the inpatient setting? | ||

| Never | 21 | 20% |

| 1–3 times per week | 4 | 3.8% |

| 1–3 times per month | 18 | 17.1% |

| 1–3 times per year | 48 | 45.7% |

| Other† | 14 | 13.4% |

| Do you have difficulty getting bevacizumab approved for inpatient use? | ||

| Yes | 42 | 40% |

| No | 59 | 56.2% |

| No answer | 4 | 3.8% |

| Does your hospital have special procedures in place to approve use of bevacizumab in the inpatient setting? | ||

| Yes | 25 | 23.8% |

| No | 56 | 53.3% |

| Not sure | 24 | 22.9% |

| In the last 12 months has inpatient use of bevacizumab been declined by your hospital? | ||

| Yes | 19 | 18.1% |

| No | 82 | 78.1% |

| No answer | 4 | 3.8% |

| In cases where you used bevacizumab in the inpatient setting was the patient’s outcome favorable? | ||

| Yes | 72 | 68.6% |

| No | 15 | 14.3% |

| No answer | 18 | 17.1% |

| In cases where you initiated bevacizumab in the inpatient setting, were you able to continue the medication outpatient? | ||

| Yes | 81 | 77.1% |

| No | 11 | 10.5% |

| No answer | 13 | 12.4% |

| Do you include considerations about the cost effectiveness of bevacizumab when you offer treatment plans to patients? | ||

| No - if I think it could result in improvement, I offer it as a treatment option | 48 | 45.7% |

| Yes - but only if the patient is underinsured or uninsured and the expenses would be prohibitive | 12 | 11.4% |

| Yes - if I think the cost-benefit ratio is not favorable, I do not offer it as a treatment option at all | 12 | 11.4% |

| Yes - but I still offer it as a treatment option and defer decision to patient | 30 | 28.6% |

| No answer | 3 | 2.9% |

| . | Number . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| Specialty | ||

| Neuro-Oncologist | 70 | 66.6% |

| Neurosurgeon | 17 | 16.2% |

| Radiation Oncologist | 5 | 4.8% |

| Nurse Practitioner | 3 | 2.8% |

| Pediatric Neuro-Oncologist | 5 | 4.8% |

| Other* | 5 | 4.8% |

| Practice Setting | ||

| Academic Institution | 86 | 81.9% |

| Private Practice with Hospital Affiliation | 13 | 12.4% |

| Government Hospital | 7 | 6.7% |

| Is there a role for inpatient use of bevacizumab? | ||

| Yes | 91 | 86.7% |

| No | 14 | 13.3% |

| How often do you use bevacizumab in the inpatient setting? | ||

| Never | 21 | 20% |

| 1–3 times per week | 4 | 3.8% |

| 1–3 times per month | 18 | 17.1% |

| 1–3 times per year | 48 | 45.7% |

| Other† | 14 | 13.4% |

| Do you have difficulty getting bevacizumab approved for inpatient use? | ||

| Yes | 42 | 40% |

| No | 59 | 56.2% |

| No answer | 4 | 3.8% |

| Does your hospital have special procedures in place to approve use of bevacizumab in the inpatient setting? | ||

| Yes | 25 | 23.8% |

| No | 56 | 53.3% |

| Not sure | 24 | 22.9% |

| In the last 12 months has inpatient use of bevacizumab been declined by your hospital? | ||

| Yes | 19 | 18.1% |

| No | 82 | 78.1% |

| No answer | 4 | 3.8% |

| In cases where you used bevacizumab in the inpatient setting was the patient’s outcome favorable? | ||

| Yes | 72 | 68.6% |

| No | 15 | 14.3% |

| No answer | 18 | 17.1% |

| In cases where you initiated bevacizumab in the inpatient setting, were you able to continue the medication outpatient? | ||

| Yes | 81 | 77.1% |

| No | 11 | 10.5% |

| No answer | 13 | 12.4% |

| Do you include considerations about the cost effectiveness of bevacizumab when you offer treatment plans to patients? | ||

| No - if I think it could result in improvement, I offer it as a treatment option | 48 | 45.7% |

| Yes - but only if the patient is underinsured or uninsured and the expenses would be prohibitive | 12 | 11.4% |

| Yes - if I think the cost-benefit ratio is not favorable, I do not offer it as a treatment option at all | 12 | 11.4% |

| Yes - but I still offer it as a treatment option and defer decision to patient | 30 | 28.6% |

| No answer | 3 | 2.9% |

*Included nurses and medical oncologists

†Included “rarely,” once every few years, or “when indicated.”

Experience with Bevacizumab in the Inpatient Setting

Of the 105 survey respondents, 91 (87%) felt that there was a need for access to inpatient bevacizumab and 87 (83%) had personally used this medication. Favorable responses to bevacizumab use were reported by a significant majority (69%) of respondents, while 14% reported unfavorable responses (17% did not answer). There was a broad range in the frequency of bevacizumab usage with a majority (57%) of those prescribing this medication using it 1 to 3 times per year. Respondent comments suggest that bevacizumab usage would be higher if it was more available. Bevacizumab availability was also highly variable. Some respondents noted that they “cannot get it approved,” while at the other end of the spectrum, bevacizumab was universally covered (for example, in Japan). In total, 40% of respondents reported difficulty in obtaining approval for inpatient bevacizumab use. Extraordinary measures for approval were often required from the medical directors, pharmacy leadership, inpatient hospital service committees, or cost containment committees. In fact, 24% of respondents reported that their centers had special bevacizumab approval procedures, while 23% were not sure. Typical permissible justifications included clinical decline, failure to respond to high doses of steroids, and lifesaving necessity. With these measures, 18% of survey respondents reported denials by their institutions. Furthermore, several respondents commented that they had stopped trying because of difficult paperwork or because they knew it would be denied. Of the respondents who had experience with using bevacizumab in the inpatient setting, 69% described patient outcomes as having been “favorable after treatment” (Table 1).

Continuing Treatment Outpatient

Approximately 77% of respondents reported that their patients were able to continue treatment with bevacizumab in the outpatient setting after initiating the treatment in the inpatient setting, while 10% were unable to do so.

Consideration of Cost Effectiveness of Bevacizumab in Patient Counseling

We found that 47% of our respondents described that they generally did not consider the cost effectiveness of bevacizumab in their treatment discussions – if they felt it could result in an improvement, they offered it as a treatment option. A smaller percentage, about 29%, included cost effectiveness considerations in their counseling but offered it as a treatment option and deferred the final decision to the patient. Only about 12% of the respondents considered the cost effectiveness for the uninsured or underinsured patient, where they felt the expense may be prohibitive. If the cost-benefit ratio was not found to be favorable, 12% did not offer it as a treatment option at all.

Case Examples

We present two brain tumor patients who were considered for inpatient bevacizumab treatment. One of these patients was approved for bevacizumab treatment while the other was denied access to this medication. We use these cases to illustrate the differences in clinical history and hospitalization costs.

Case 1

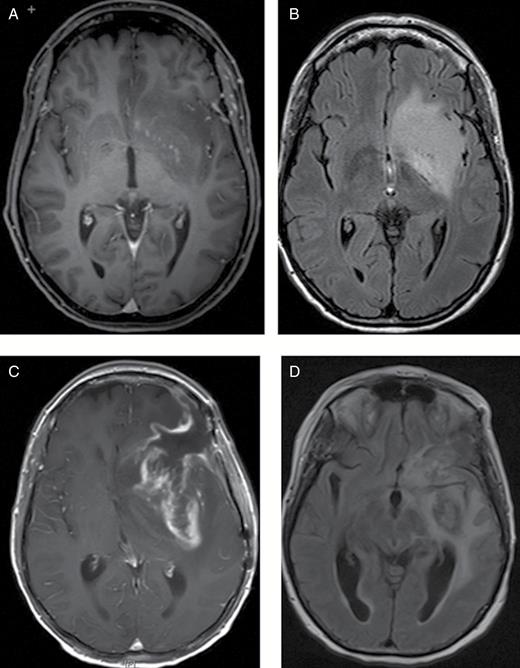

A 49-year-old female was diagnosed with a left frontotemporal anaplastic astrocytoma in November 2015 (Fig. 1A and B). She underwent subtotal resection of the mass and subsequent radiation therapy. Less than one month after completion of radiation therapy she developed worsening right-sided hemiparesis and encephalopathy. She was admitted to the hospital in February 2016 where MRI suggested rapid disease progression versus pseudoprogression with significant increase in T2/FLAIR signal hyperintensity, enhancement of the previously non-enhancing mass, and worsening midline shift (Fig. 1C and D). She responded initially to steroids and was discharged to a nursing home, but returned to the hospital 1 week later with worsening symptoms and failure to thrive. During this hospital stay, use of bevacizumab was planned with palliative intent. The case was reviewed by a special committee and ultimately approval for inpatient use of this medication was denied. The patient had a prolonged hospital course lasting 3 weeks that was notable for increasing somnolence and depression. She was maintained on steroids and discharged to a skilled nursing facility. The hospital charges for this 3-week inpatient stay totaled $61000. She was re-admitted to the hospital for further clinical deterioration 4 months later (from the nursing home) and was ultimately discharged to home hospice. Charges for this subsequent hospital stay totaled an additional $18000.

Case 1. MRI brain: axial T1 postcontrast (A) and FLAIR (B) images at the time of diagnosis shows a predominantly non-enhancing lesion in the left frontotemporal area. Note midline shift and increasing vasogenic edema in the left frontotemporal at the time of progression as seen on axial T1 post contrast (C) and FLAIR (D) images. The patient did not respond to steroids and did not receive bevacizumab. She progressed clinically and required specialized institutional nursing care for several months before she died.

Case 2

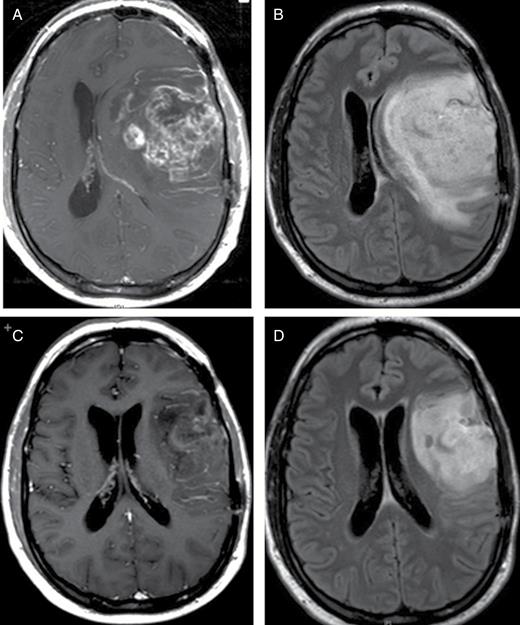

A 41-year-old man presented with headache and aphasia in March 2009 and was diagnosed with a left frontotemporal glioblastoma. He underwent subtotal resection followed by radiation therapy with concurrent temozolomide. After only one cycle of subsequent adjuvant temozolomide, the patient deteriorated clinically and was admitted to the neurology service in July where MRI showed rapid disease progression versus pseudoprogression (Fig. 2A and B). His Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) was estimated at about 50 to 60 and was notable for aphasia, right-sided weakness, and inability to ambulate. High doses of steroids did not result in clinical improvement. Given the patient’s significant clinical neurologic deterioration and with imaging showing midline shift, the decision was made to transition to bevacizumab with addition of carboplatin. The patient showed rapid clinical improvement and was transferred to inpatient rehabilitation just a few days after his first inpatient bevacizumab treatment and was subsequently discharged home. His hospital length-of-stay was only 1 week and total hospital charges were $31000. The cost charged to insurance for his single treatment of bevacizumab was $4400, included in this total. Treatment was continued after hospital discharge as an outpatient and MRI in September (2 months later) demonstrated significant radiographic improvement (Fig. 2C and D). His KPS improved to 90 and he returned to work. Ultimately bevacizumab treatment was discontinued after 1 year due to proteinuria.

Case 2. MRI brain: axial T1 postcontrast (A) and FLAIR (B) images at the time of progression and admission to hospital shows significant midline shift secondary to tumor growth and surrounding vasogenic edema. The patient received bevacizumab during inpatient admission and rapidly improved both clinically and radiographically. Corresponding MR images of the brain show significant reduction of the enhancing tumor volume, decrease in vasogenic edema and reversal of the midline shift after 3 doses of bevacizumab (C, D).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that neuro-oncologists are frequently confronted with a decision to use bevacizumab in the inpatient setting. The indications typically include clinical deterioration due to cerebral edema in the setting of progressive glioma or radiation necrosis in primary or metastatic tumors where steroids are ineffective or have too many side effects.7,10,21,22 Inpatient use of bevacizumab is frequently monitored by appointed hospital committees due to the high cost of the medication. While cost-effectiveness is necessary, it is important to take into consideration the impact of this medication on overall health care costs, including possible complications of a prolonged, expensive hospital stay and nursing care. Bevacizumab, because of its mechanism of action and potential of rapid improvement of severe neurologic impairment, deserves special attention.

As illustrated by our survey, the majority of respondents believe that bevacizumab should be available for the inpatient use, and favorable outcomes were reported in approximately 70% of cases where bevacizumab was used in the inpatient setting. Several studies have suggested that bevacizumab can improve quality of life, decrease neurological morbidity, and our experience suggests that the use of the drug may shorten hospital stays and ultimately decrease cost of care. While the majority of hospital settings do not have special procedures needed for the use of the medication, almost a quarter of the institutions in the United States have some restrictions. While several publications have found the cost-effectiveness of outpatient bevacizumab use to be unfavorable in terms of long-term patient outcomes and survival, many clinicians believe there may be utility in using the drug acutely in the inpatient setting. When used in appropriate cases it may positively impact neurologic morbidity, improve quality of life, and significantly decrease the length of inpatient stay. Respondents to our survey agreed with utility of inpatient use of bevacizumab in the right patient, but a large percentage (close to 40%) of the respondents reported difficulty in getting the drug approved for use in the inpatient setting. Almost a quarter described restrictions and special procedures in place to approve use of the drug at their institutions. Our work thus highlights the discrepancy between provider consensus opinion and hospital policies that discourage bevacizumab use.

The cases we present illustrate two scenarios where bevacizumab was and was not approved, respectively. The differences between these cases provide a striking example of how the clinical outcome (quality of life, neurologic status, length of inpatient admission) can be significantly improved with inpatient bevacizumab use. In the first case, bevacizumab was not used; the patient had a prolonged 3-week hospital stay, did not improve clinically, was subjected to the side effects of long-term steroid use, and required skilled nursing facility care after discharge for a prolonged period of time. Bevacizumab approval is even more difficult when a patient is in a rehabilitation unit or a nursing home, largely because of the insurance payment benefit structure not allowing provision for certain therapies (including chemotherapy) while the patient is undergoing rehabilitation. Frequently, like in our case, the patient cannot receive bevacizumab until discharged home, and the total cost of hospital care ends up being significantly higher. In the second case where bevacizumab was used promptly, the patient was able to rapidly improve neurologically, discontinue steroids, and return to work and life with his family after a short period of rehabilitation. Total hospital charges were significantly lower when bevacizumab was used inpatient ($31000) as compared to the case where it was not ($79000).

There are several limitations to our study. We had only a relatively small number of participants, and thus a limited opinion pool, of the membership of SNO. A survey such as ours is likely affected by participation bias as practitioners who have encountered difficulties with obtaining bevacizumab approval maybe more likely to respond and voice their opinions. The majority of respondents were from the academic institutions in the United States, therefore, community and private hospitals are not well represented. We emphasize that the favorable bevacizumab experiences quantified in this survey reflect expert opinions rather than objective data. The cases we used were selected intentionally to highlight the possible benefits of prompt utilization of anti-VEGF therapy in the inpatient setting and may not represent all indications/scenarios for this application. They should, however, help understand more global and long-term benefits of the drug (to the individual patient and to the health care system), rather than just focusing on the cost of a single dose of the drug. These results could help hospital administrators conduct cost effectiveness analyses and design approval processes that would benefit the patient and would be physician-friendly.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Linda Greer from the Society of Neuro-Oncology (SNO) for assisting with distribution of the survey. We thank every member of SNO who participated in our survey. Deborah Frieze at the University of Washington Pharmacy and Ida Stein in the Billings Department were invaluable resources and we are very grateful for their assistance.

References