-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Koichi Takeda, Taro Shiga, The knowledge and skills required for the onco-rheumatologist: Study of four-year consultation records of a high-volume cancer centre, Modern Rheumatology, Volume 35, Issue 3, May 2025, Pages 402–409, https://doi.org/10.1093/mr/roae114

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Onco-rheumatology, the intersection of oncology and rheumatology, is an emerging field requiring further definition. This study aimed to identify the knowledge and skills essential for rheumatologists in clinical oncology.

We retrospectively reviewed consultations with the onco-rheumatology department of a high-volume tertiary cancer centre in Japan from January 2020 to December 2023.

We analysed 417 consultations. The most common consultation (229, 55%) was related to immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Of the 238 irAEs in 185 patients, 15% were rheumatic and 85% were nonrheumatic (e.g. hepatobiliary toxicities, colitis). Approximately 25% of nonendocrine irAEs were refractory/relapsing, requiring second-line therapy (e.g. mycophenolate mofetil, biologics, immunoglobulin). In addition to irAE consultations, 137 (33%) consultations were about possible rheumatic diseases. The final diagnosis often related to cancer treatment, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-related aortitis (15 patients, 11%), olaparib-related erythema nodosum (10 patients, 7.3%), and surgical menopause-related arthralgia (10 patients, 7.3%). Five patients (3.6%) were diagnosed with autoinflammatory bone disease mimicking bone tumours.

Onco-rheumatologists are expected to play a central role in the management of a wide range of irAEs, not limited to rheumatic irAEs. They must also manage rheumatologic manifestations during cancer treatment and rheumatic diseases that mimic tumours.

Introduction

Treatment has become increasingly complex in oncology. In line with this trend, collaboration with other medical fields and multidisciplinary professionals has become increasingly important. Moreover, novel fields – such as onco-cardiology, onco-nephrology [1–3], and onco-rheumatology – have emerged. In 2020, Szekanecz et al. [4] reported that onco-rheumatology encompasses the following eight clinical and practical pillars: secondary malignancies in rheumatologic diseases, soluble tumour antigens in rheumatologic diseases, tumour formation/cancer with relapsed rheumatologic drug therapy, nondrug therapy (physiotherapy) in locomotor cancer patients, paraneoplastic syndromes, autoimmune/rheumatologic disorders with oncotherapy, osteoporosis with hormone deprivation therapy, and tumours of the musculoskeletal system.

However, the kinds of knowledge and skills that are required for onco-rheumatologists in real clinical practice have yet to be established. We conducted a retrospective descriptive study at a Japanese high-volume tertiary cancer centre to analyse consultations with the Department of Onco-Rheumatology and clarify what is required of rheumatologists in this new field.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A retrospective observational study was conducted at the Japan Foundation for Cancer Research Hospital (JFCR). The JFCR is a 686-bed, high-volume tertiary cancer centre in Tokyo, with approximately 8800 first-time visitors and 18,000 new admissions annually.

Our cancer centre does not have a standard rheumatology department, but instead established the Department of Onco-Rheumatology in January 2020, as a specialised department for onco-rheumatology.

The Department of Onco-Rheumatology is required to provide consultation services for all kinds of cancer-related rheumatic diseases, be a member of the immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-induced immune-related adverse events (irAEs) team (comprising physicians with multiple specialties, such as oncologists, emergency physicians, and cardiologists, in addition to rheumatologists), and engage in the management of a wide range of irAEs, not limited to rheumatic irAEs. During the study period, KT was the only physician working in the Department of Onco-Rheumatology. He was a board-certified rheumatologist who engaged in in-house consultation 4 days per week and an outpatient clinic half a day per week. In cases where it was difficult to distinguish between arthralgia and arthritis, musculoskeletal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging were used for further evaluation.

In this study, we used the Department of Onco-Rheumatology’s consultation database. We extracted data on cases that were formally consulted from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2023. The following were excluded from the study: consultations with JFCR staff about symptoms unrelated to cancer, informal consultations, and follow-up consultations about consultations that had already taken place.

Data collection

The following data were extracted: age, sex, place of consultation (outpatient or inpatient), underlying cancer, and type of consultation, including consultations regarding (1) irAEs, (2) possible rheumatic disease, (3) management of underlying rheumatic disease, and (4) other issues. For consultations about irAEs, we collected data on the total number of irAEs (since some patients develop multiple irAEs at the same time or at different time intervals), the category of irAE, and the type of ICI used. Regarding the treatment of irAEs, we analysed the dose of glucocorticoids required; if second-line therapy other than glucocorticoids (e.g. immunosuppressive agents, biologic agents, immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange) was selected for treating irAEs, we recorded the type of irAEs treated and the treatment selected. For consultations regarding the possibility of rheumatic diseases, we analysed the details of the symptoms and findings that triggered the consultation and the final diagnosis. For consultations related to the management of underlying rheumatic diseases, the type of underlying rheumatic disease and the consultation outline were analysed.

Ethics approval statement

Institutional review board approval was obtained before initiating the study (approval number: 2020-GB-180). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent for this retrospective, noninvasive study not containing personally identifiable information was waived by the ethics committee.

Results

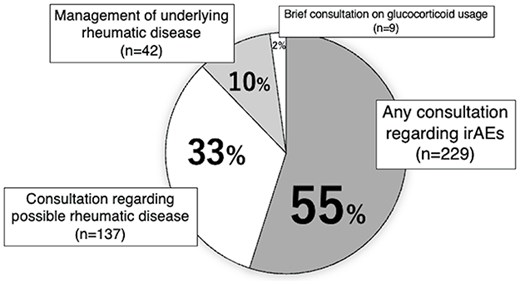

During the study period, 422 patients were referred to the Department of Onco-Rheumatology. Consultations on symptoms for five JFCR staff members unrelated to cancer were excluded, and the consultations for the remaining 417 patients were analysed. Patient demographics and consultation categories are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively.

| Median age (range) | 64 (10–88) |

| Sex, male (%) | 171 (41) |

| Place of consultation (%) | |

| Inpatient | 275 (66) |

| Outpatient | 142 (34) |

| Underlying cancer (%) | |

| Haematologic malignancies | 12 (2.9) |

| Solid tumours | 391 (94) |

| Gynaecologic | 101 (24) |

| Thoracic | 82 (20) |

| Gastrointestinal | 63 (15) |

| Genitourinary | 43 (10) |

| Head and neck | 39 (9.4) |

| Breast | 28 (6.7) |

| Melanoma and other neoplasms of the skin | 12 (2.9) |

| Hepato-biliary-pancreatic | 9 (2.2) |

| Sarcoma | 7 (1.7) |

| Other solid tumoura | 5 (1.2) |

| Noneb | 14 (3.4) |

| Median age (range) | 64 (10–88) |

| Sex, male (%) | 171 (41) |

| Place of consultation (%) | |

| Inpatient | 275 (66) |

| Outpatient | 142 (34) |

| Underlying cancer (%) | |

| Haematologic malignancies | 12 (2.9) |

| Solid tumours | 391 (94) |

| Gynaecologic | 101 (24) |

| Thoracic | 82 (20) |

| Gastrointestinal | 63 (15) |

| Genitourinary | 43 (10) |

| Head and neck | 39 (9.4) |

| Breast | 28 (6.7) |

| Melanoma and other neoplasms of the skin | 12 (2.9) |

| Hepato-biliary-pancreatic | 9 (2.2) |

| Sarcoma | 7 (1.7) |

| Other solid tumoura | 5 (1.2) |

| Noneb | 14 (3.4) |

The five other types of solid tumour were carcinoma of unknown primary (n = 3), schwannoma (n = 1), and germ cell tumour (n = 1).

These 14 patients were referred to our facility after cancer was suspected at other hospitals; however, further examinations revealed that they did not have cancer.

| Median age (range) | 64 (10–88) |

| Sex, male (%) | 171 (41) |

| Place of consultation (%) | |

| Inpatient | 275 (66) |

| Outpatient | 142 (34) |

| Underlying cancer (%) | |

| Haematologic malignancies | 12 (2.9) |

| Solid tumours | 391 (94) |

| Gynaecologic | 101 (24) |

| Thoracic | 82 (20) |

| Gastrointestinal | 63 (15) |

| Genitourinary | 43 (10) |

| Head and neck | 39 (9.4) |

| Breast | 28 (6.7) |

| Melanoma and other neoplasms of the skin | 12 (2.9) |

| Hepato-biliary-pancreatic | 9 (2.2) |

| Sarcoma | 7 (1.7) |

| Other solid tumoura | 5 (1.2) |

| Noneb | 14 (3.4) |

| Median age (range) | 64 (10–88) |

| Sex, male (%) | 171 (41) |

| Place of consultation (%) | |

| Inpatient | 275 (66) |

| Outpatient | 142 (34) |

| Underlying cancer (%) | |

| Haematologic malignancies | 12 (2.9) |

| Solid tumours | 391 (94) |

| Gynaecologic | 101 (24) |

| Thoracic | 82 (20) |

| Gastrointestinal | 63 (15) |

| Genitourinary | 43 (10) |

| Head and neck | 39 (9.4) |

| Breast | 28 (6.7) |

| Melanoma and other neoplasms of the skin | 12 (2.9) |

| Hepato-biliary-pancreatic | 9 (2.2) |

| Sarcoma | 7 (1.7) |

| Other solid tumoura | 5 (1.2) |

| Noneb | 14 (3.4) |

The five other types of solid tumour were carcinoma of unknown primary (n = 3), schwannoma (n = 1), and germ cell tumour (n = 1).

These 14 patients were referred to our facility after cancer was suspected at other hospitals; however, further examinations revealed that they did not have cancer.

The most common type of consultation was for irAEs [229 patients (55%)], followed by consultations for possible rheumatic diseases [137 patients (33%)]. There were 42 (10%) consultations regarding the management of underlying rheumatic diseases. The remaining nine patient consultations (2%), classified as ‘others’, were all brief consultations on using glucocorticoids.

Consultations regarding irAEs

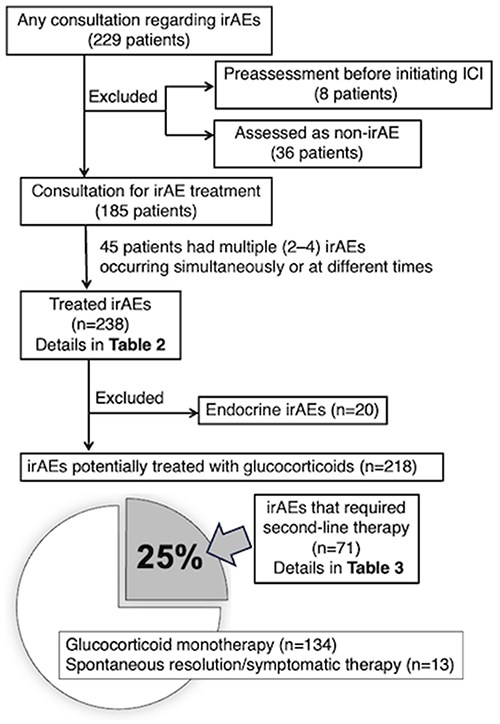

Figure 2 illustrates the overall picture of consultations related to irAEs. Of the 229 patients who had consultations for irAEs, 8 were referred for evaluation before starting ICIs for underlying autoimmune/rheumatic diseases [3 rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 1 systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), 1 dermatomyositis, 1 psoriatic arthritis, 1 positive antinuclear antibody, and 1 nonspecific creatine kinase elevation]. Thirty-six patients had consultations for suspected irAEs that were later deemed not to be irAEs. Of the remaining 185 patients, 122 were treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), 22 with anti-PD ligand 1 (PD-L1), and 41 with the combination of anti-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and anti-PD-(L)1; among those 185, 45 had multiple (2–4) irAEs occur simultaneously or at different time points. The department was involved in the treatment of 238 irAEs, which are listed in Table 2 according to irAE category. Only 36 (15%) were rheumatic irAEs, and 202 (85%) were nonrheumatic irAEs, including hepatobiliary toxicities and colitis.

| irAE category . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rheumatic | 36 (15) |

| Myositis | 13 (4.6) |

| Arthritis | 6 (2.1) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica-like | 5 (1.8) |

| Arthralgia | 4 (1.4) |

| Raynaud’s‐like phenomenon | 2 (0.7) |

| Small vessel vasculitis | 2 (0.7) |

| Sicca syndrome | 1 (0.4) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1 (0.4) |

| SLE | 1 (0.4) |

| RA flare | 1 (0.4) |

| Nonrheumatic | 202 (85) |

| Hepatobiliary | 46 (16) |

| Colitis | 31 (11) |

| Dermatological | 20 (7.1) |

| Endocrine | 20 (7.1) |

| Neurological | 18 (6.4) |

| Cardiovascular | 14 (5.0) |

| CRS/HLH | 14 (5.0) |

| Pulmonary | 12 (4.3) |

| Haematologic | 7 (2.5) |

| Upper gastrointestinal | 7 (2.5) |

| Renal | 3 (1.1) |

| Pancreatic | 2 (0.7) |

| Cervical lymphadenitis | 2 (0.7) |

| Others | 6 (2.1) |

| irAE category . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rheumatic | 36 (15) |

| Myositis | 13 (4.6) |

| Arthritis | 6 (2.1) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica-like | 5 (1.8) |

| Arthralgia | 4 (1.4) |

| Raynaud’s‐like phenomenon | 2 (0.7) |

| Small vessel vasculitis | 2 (0.7) |

| Sicca syndrome | 1 (0.4) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1 (0.4) |

| SLE | 1 (0.4) |

| RA flare | 1 (0.4) |

| Nonrheumatic | 202 (85) |

| Hepatobiliary | 46 (16) |

| Colitis | 31 (11) |

| Dermatological | 20 (7.1) |

| Endocrine | 20 (7.1) |

| Neurological | 18 (6.4) |

| Cardiovascular | 14 (5.0) |

| CRS/HLH | 14 (5.0) |

| Pulmonary | 12 (4.3) |

| Haematologic | 7 (2.5) |

| Upper gastrointestinal | 7 (2.5) |

| Renal | 3 (1.1) |

| Pancreatic | 2 (0.7) |

| Cervical lymphadenitis | 2 (0.7) |

| Others | 6 (2.1) |

Of the 185 patients consulted for treatment of irAEs, 45 had multiple (2–4) irAEs simultaneously or at different times, so we treated 238 irAEs.

CRS, cytokine release syndrome; HLH, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

| irAE category . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rheumatic | 36 (15) |

| Myositis | 13 (4.6) |

| Arthritis | 6 (2.1) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica-like | 5 (1.8) |

| Arthralgia | 4 (1.4) |

| Raynaud’s‐like phenomenon | 2 (0.7) |

| Small vessel vasculitis | 2 (0.7) |

| Sicca syndrome | 1 (0.4) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1 (0.4) |

| SLE | 1 (0.4) |

| RA flare | 1 (0.4) |

| Nonrheumatic | 202 (85) |

| Hepatobiliary | 46 (16) |

| Colitis | 31 (11) |

| Dermatological | 20 (7.1) |

| Endocrine | 20 (7.1) |

| Neurological | 18 (6.4) |

| Cardiovascular | 14 (5.0) |

| CRS/HLH | 14 (5.0) |

| Pulmonary | 12 (4.3) |

| Haematologic | 7 (2.5) |

| Upper gastrointestinal | 7 (2.5) |

| Renal | 3 (1.1) |

| Pancreatic | 2 (0.7) |

| Cervical lymphadenitis | 2 (0.7) |

| Others | 6 (2.1) |

| irAE category . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rheumatic | 36 (15) |

| Myositis | 13 (4.6) |

| Arthritis | 6 (2.1) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica-like | 5 (1.8) |

| Arthralgia | 4 (1.4) |

| Raynaud’s‐like phenomenon | 2 (0.7) |

| Small vessel vasculitis | 2 (0.7) |

| Sicca syndrome | 1 (0.4) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1 (0.4) |

| SLE | 1 (0.4) |

| RA flare | 1 (0.4) |

| Nonrheumatic | 202 (85) |

| Hepatobiliary | 46 (16) |

| Colitis | 31 (11) |

| Dermatological | 20 (7.1) |

| Endocrine | 20 (7.1) |

| Neurological | 18 (6.4) |

| Cardiovascular | 14 (5.0) |

| CRS/HLH | 14 (5.0) |

| Pulmonary | 12 (4.3) |

| Haematologic | 7 (2.5) |

| Upper gastrointestinal | 7 (2.5) |

| Renal | 3 (1.1) |

| Pancreatic | 2 (0.7) |

| Cervical lymphadenitis | 2 (0.7) |

| Others | 6 (2.1) |

Of the 185 patients consulted for treatment of irAEs, 45 had multiple (2–4) irAEs simultaneously or at different times, so we treated 238 irAEs.

CRS, cytokine release syndrome; HLH, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Excluding 20 endocrine irAEs for which hormone replacement therapy was the primary treatment, 203 (93%) of the 218 irAEs were treated with glucocorticoids. Most required prednisone/methylprednisolone ≥0.5 mg/kg/day [median 1 mg/kg/day (range 0.1–2.2 mg/kg/day)], and 71 (25%) required one or more second-line therapies, most of which were used in addition to glucocorticoids. Table 3 summarises the second-line therapies used in these 71 cases and the irAEs they treated. Second-line therapy was selected on 87 occasions. Oral immunosuppressive agents, mostly mycophenolate mofetil, were used on 37 (42%) occasions. Biologic agents were used on 25 (28%) occasions, with vedolizumab, infliximab, and tocilizumab being the most frequently selected agents. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) was also used on 14 (16%) occasions.

| Details of second-line therapy . | n (%) . | irAEs treated with each second-line therapy . | Occasions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral immunosuppressive drugs | 37 (42) | ||

| MMF | 31 (35) | Hepatobiliary | 22 |

| Myocarditis | 5 | ||

| Pneumonitis | 1 | ||

| CRS/HLH | 1 | ||

| Pancreatitis | 1 | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1 | ||

| Azathioprine | 1 (1.1) | Hepatobiliary | 1 |

| Sulfasalazine | 3 (3.4) | Arthritis | 3 |

| Iguratimod | 1 (1.1) | Arthritis | 1 |

| MTX | 1 (1.1) | Arthritis | 1 |

| Biologics | 25 (28) | ||

| Infliximab | 6 (6.8) | Colitis | 5 |

| Renal | 1 | ||

| Vedolizumab | 11 (13) | Colitis | 11 |

| Tocilizumab | 6 (6.8) | CRS/HLH | 3 |

| Hepatobiliary | 2 | ||

| Arthritis | 1 | ||

| Rituximab | 1 (1.1) | Myasthenia gravis | 1 |

| Guselkumab | 1 (1.1) | Psoriatic arthritis | 1 |

| IVIg | 14 (16) | CRS/HLH | 3 |

| Dermatological | 4 | ||

| Encephalitis | 2 | ||

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 | ||

| GBS | 1 | ||

| Myocarditis | 1 | ||

| Myositis | 1 | ||

| Plasma exchange | 5 (5.7) | CRS/HLH | 2 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 | ||

| Renal | 1 | ||

| Others | 6 (6.8) | ||

| Colchicine | 2 (2.3) | Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis | 2 ※1 |

| Intra-articular glucocorticoid injection | 2 (2.3) | Arthritis | 2 ※2 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (1.1) | SLE | 1 |

| Alprostadil | 1 (1.1) | Raynaud’s‐like phenomenon | 1 |

| Details of second-line therapy . | n (%) . | irAEs treated with each second-line therapy . | Occasions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral immunosuppressive drugs | 37 (42) | ||

| MMF | 31 (35) | Hepatobiliary | 22 |

| Myocarditis | 5 | ||

| Pneumonitis | 1 | ||

| CRS/HLH | 1 | ||

| Pancreatitis | 1 | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1 | ||

| Azathioprine | 1 (1.1) | Hepatobiliary | 1 |

| Sulfasalazine | 3 (3.4) | Arthritis | 3 |

| Iguratimod | 1 (1.1) | Arthritis | 1 |

| MTX | 1 (1.1) | Arthritis | 1 |

| Biologics | 25 (28) | ||

| Infliximab | 6 (6.8) | Colitis | 5 |

| Renal | 1 | ||

| Vedolizumab | 11 (13) | Colitis | 11 |

| Tocilizumab | 6 (6.8) | CRS/HLH | 3 |

| Hepatobiliary | 2 | ||

| Arthritis | 1 | ||

| Rituximab | 1 (1.1) | Myasthenia gravis | 1 |

| Guselkumab | 1 (1.1) | Psoriatic arthritis | 1 |

| IVIg | 14 (16) | CRS/HLH | 3 |

| Dermatological | 4 | ||

| Encephalitis | 2 | ||

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 | ||

| GBS | 1 | ||

| Myocarditis | 1 | ||

| Myositis | 1 | ||

| Plasma exchange | 5 (5.7) | CRS/HLH | 2 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 | ||

| Renal | 1 | ||

| Others | 6 (6.8) | ||

| Colchicine | 2 (2.3) | Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis | 2 ※1 |

| Intra-articular glucocorticoid injection | 2 (2.3) | Arthritis | 2 ※2 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (1.1) | SLE | 1 |

| Alprostadil | 1 (1.1) | Raynaud’s‐like phenomenon | 1 |

There were 87 occasions of second-line therapy use for 71 irAEs. On most occasions, they were used in addition to glucocorticoids, with two exceptions. One case of IgA vasculitis was treated with colchicine alone (※1). In the other case, arthritis was controlled by intra-articular glucocorticoid injection together with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (※2).

MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate CRS, cytokine release syndrome; HLH, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; GBS, Guillain–Barre syndrome.

| Details of second-line therapy . | n (%) . | irAEs treated with each second-line therapy . | Occasions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral immunosuppressive drugs | 37 (42) | ||

| MMF | 31 (35) | Hepatobiliary | 22 |

| Myocarditis | 5 | ||

| Pneumonitis | 1 | ||

| CRS/HLH | 1 | ||

| Pancreatitis | 1 | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1 | ||

| Azathioprine | 1 (1.1) | Hepatobiliary | 1 |

| Sulfasalazine | 3 (3.4) | Arthritis | 3 |

| Iguratimod | 1 (1.1) | Arthritis | 1 |

| MTX | 1 (1.1) | Arthritis | 1 |

| Biologics | 25 (28) | ||

| Infliximab | 6 (6.8) | Colitis | 5 |

| Renal | 1 | ||

| Vedolizumab | 11 (13) | Colitis | 11 |

| Tocilizumab | 6 (6.8) | CRS/HLH | 3 |

| Hepatobiliary | 2 | ||

| Arthritis | 1 | ||

| Rituximab | 1 (1.1) | Myasthenia gravis | 1 |

| Guselkumab | 1 (1.1) | Psoriatic arthritis | 1 |

| IVIg | 14 (16) | CRS/HLH | 3 |

| Dermatological | 4 | ||

| Encephalitis | 2 | ||

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 | ||

| GBS | 1 | ||

| Myocarditis | 1 | ||

| Myositis | 1 | ||

| Plasma exchange | 5 (5.7) | CRS/HLH | 2 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 | ||

| Renal | 1 | ||

| Others | 6 (6.8) | ||

| Colchicine | 2 (2.3) | Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis | 2 ※1 |

| Intra-articular glucocorticoid injection | 2 (2.3) | Arthritis | 2 ※2 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (1.1) | SLE | 1 |

| Alprostadil | 1 (1.1) | Raynaud’s‐like phenomenon | 1 |

| Details of second-line therapy . | n (%) . | irAEs treated with each second-line therapy . | Occasions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral immunosuppressive drugs | 37 (42) | ||

| MMF | 31 (35) | Hepatobiliary | 22 |

| Myocarditis | 5 | ||

| Pneumonitis | 1 | ||

| CRS/HLH | 1 | ||

| Pancreatitis | 1 | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1 | ||

| Azathioprine | 1 (1.1) | Hepatobiliary | 1 |

| Sulfasalazine | 3 (3.4) | Arthritis | 3 |

| Iguratimod | 1 (1.1) | Arthritis | 1 |

| MTX | 1 (1.1) | Arthritis | 1 |

| Biologics | 25 (28) | ||

| Infliximab | 6 (6.8) | Colitis | 5 |

| Renal | 1 | ||

| Vedolizumab | 11 (13) | Colitis | 11 |

| Tocilizumab | 6 (6.8) | CRS/HLH | 3 |

| Hepatobiliary | 2 | ||

| Arthritis | 1 | ||

| Rituximab | 1 (1.1) | Myasthenia gravis | 1 |

| Guselkumab | 1 (1.1) | Psoriatic arthritis | 1 |

| IVIg | 14 (16) | CRS/HLH | 3 |

| Dermatological | 4 | ||

| Encephalitis | 2 | ||

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 | ||

| GBS | 1 | ||

| Myocarditis | 1 | ||

| Myositis | 1 | ||

| Plasma exchange | 5 (5.7) | CRS/HLH | 2 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 | ||

| Renal | 1 | ||

| Others | 6 (6.8) | ||

| Colchicine | 2 (2.3) | Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis | 2 ※1 |

| Intra-articular glucocorticoid injection | 2 (2.3) | Arthritis | 2 ※2 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (1.1) | SLE | 1 |

| Alprostadil | 1 (1.1) | Raynaud’s‐like phenomenon | 1 |

There were 87 occasions of second-line therapy use for 71 irAEs. On most occasions, they were used in addition to glucocorticoids, with two exceptions. One case of IgA vasculitis was treated with colchicine alone (※1). In the other case, arthritis was controlled by intra-articular glucocorticoid injection together with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (※2).

MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate CRS, cytokine release syndrome; HLH, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; GBS, Guillain–Barre syndrome.

Consultation on possible rheumatic diseases

The reason for the consultation and the final diagnosis after further examination for the 137 patients who underwent consultation on possible rheumatic disease are shown in Table 4. The top three reasons for consultation were musculoskeletal pain in 37 patients (27%), aortitis revealed by computed tomography in 17 patients (12%), and dermatological problems in 16 patients (12%). There was considerable variation in the final diagnosis. The top three were granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–associated aortitis in 15 cases (11%), olaparib-associated erythema nodosum in 10 cases (7.3%), and surgical menopause-associated arthralgia in 10 cases (7.3%). Of note, five patients (3.6%) were referred from other hospitals with suspected bone tumours but showed only osteitis or osteomyelitis on magnetic resonance imaging and/or pathology, and were finally diagnosed with synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome; chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO); or chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNO).

| Primary manifestations . | n (%) . | Final diagnosis (number of cases) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Arthralgia/arthritis/myalgia | 37 (27) | aSurgical menopause-associated arthralgia (10), Osteoarthritis (7), Gout (3), PMR (3), RA (2), SpA (2), aLemvatinib-associated arthralgia (1), aParaneoplastic polyarthritis (1), aPathological fracture (1), CPPD (1), Calcific tendinopathy of the shoulder (1), aEN due to Hodgkin lymphoma (1), Fibromyalgia (1), Subacromial impingement syndrome (1), De Quervain tendinopathy (1), Trigger finger (1) |

| Dermatological problems | 16 (12) | aOlaparib-induced EN (10), *Cutaneous irAEs (1), Drug eruption (1), DLE (1), aParaneoplastic dermatoses (1), Peripheral cyanosis (1), Unknown (1) | |

| Fever of unknown origin/Fever | 15 (11) | Self-limiting fever (6), Drug fever (2), MPA (2), SSI (1), aG-CSF–related aortitis (1), RA (1), CPPD (1), Chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection (1) | |

| Neurological problem | 2 (1.5) | aIntrathecal MTX-induced neurotoxicity (1), aChemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (1) | |

| Recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations | 2 (1.5) | aBehçet’s syndrome-associated with MDS (1), Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (1) | |

| Multiple lymphadenopathy | 1 (0.7) | Sarcoidosis (1) | |

| Finger deformity | 1 (0.7) | Jaccoud’s arthropathy (1) | |

| Laboratory findings | Positive for autoantibodies | 6 (4.4) | Asymptomatic anticentromere antibody carrier (2), Nonspecific antinuclear antibody positive (1), aANCA false positive due to malignancy (1), Antiphospholipid antibody carrier (1), Asymptomatic MDA-5 antibody carrier or false positive (1) |

| Elevation in creatine kinase | 2 (1.5) | Possible macro creatine kinase (1), Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 1 (0.7) | aMembranous nephropathy (1) | |

| Image and/or pathologic findings | Aortitis revealed by CT | 17 (12) | aG-CSF–related aortitis (14), Takayasu’s arteritis (1), aAortitis associated with MDS (1), Findings associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm (1) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 9 (6.6) | aLymphangiosis carcinomatosa (1), aPneumonitis associated with trastuzumab emtansine (1), Aspiration pneumonia (1), RA-associated interstitial lung disease (1), Interstitial pneumonia associated with a double-positive anti-MDA5 and anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibody (1), Antisynthetase syndrome (1), Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (1), ARDS (1), Atelectasis due to gravitational forces (1) | |

| Osteitis/osteomyelitis | 8 (5.8) | SAPHO syndrome (3), CRMO or CNO (2), Osteitis condensans ilii (2), aAML (1) | |

| Enthesitis | 1 (0.7) | SpA (1) | |

| Sacroiliac joint abnormalities | 1 (0.7) | SpA (1) | |

| Retroperitoneal fibrosis | 1 (0.7) | aRetroperitoneal bleeding related to malignancy (1) | |

| Multiple intra-abdominal masses | 1 (0.7) | Unknown (1) | |

| Dural thickness | 1 (0.7) | Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Muscle oedema | 1 (0.7) | aPost-radiation changes (1) | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (0.7) | aPulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy (1) | |

| Pericardial effusion | 2 (1.5) | aCarcinomatous pericardial effusion (1), SLE (1) | |

| Granulomatous disease | 2 (1.5) | Unknown (2) | |

| Combination of findings | Eosinophilia and pneumonia | 3 (2.2) | Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia (1), EGPA (1), Unknown (1) |

| Rash/muscle weakness | 2 (1.5) | aDermatomyositis (TIF-1γ antibody positive) (2) | |

| Pleural and pericardial effusion | 1 (0.7) | Systemic lupus erythematosus (1) | |

| Myalgia, renal disorder, ILD | 1 (0.7) | Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Low white blood cell count, anaemia | 1 (0.7) | Copper deficiency anaemia (1) | |

| Primary manifestations . | n (%) . | Final diagnosis (number of cases) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Arthralgia/arthritis/myalgia | 37 (27) | aSurgical menopause-associated arthralgia (10), Osteoarthritis (7), Gout (3), PMR (3), RA (2), SpA (2), aLemvatinib-associated arthralgia (1), aParaneoplastic polyarthritis (1), aPathological fracture (1), CPPD (1), Calcific tendinopathy of the shoulder (1), aEN due to Hodgkin lymphoma (1), Fibromyalgia (1), Subacromial impingement syndrome (1), De Quervain tendinopathy (1), Trigger finger (1) |

| Dermatological problems | 16 (12) | aOlaparib-induced EN (10), *Cutaneous irAEs (1), Drug eruption (1), DLE (1), aParaneoplastic dermatoses (1), Peripheral cyanosis (1), Unknown (1) | |

| Fever of unknown origin/Fever | 15 (11) | Self-limiting fever (6), Drug fever (2), MPA (2), SSI (1), aG-CSF–related aortitis (1), RA (1), CPPD (1), Chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection (1) | |

| Neurological problem | 2 (1.5) | aIntrathecal MTX-induced neurotoxicity (1), aChemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (1) | |

| Recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations | 2 (1.5) | aBehçet’s syndrome-associated with MDS (1), Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (1) | |

| Multiple lymphadenopathy | 1 (0.7) | Sarcoidosis (1) | |

| Finger deformity | 1 (0.7) | Jaccoud’s arthropathy (1) | |

| Laboratory findings | Positive for autoantibodies | 6 (4.4) | Asymptomatic anticentromere antibody carrier (2), Nonspecific antinuclear antibody positive (1), aANCA false positive due to malignancy (1), Antiphospholipid antibody carrier (1), Asymptomatic MDA-5 antibody carrier or false positive (1) |

| Elevation in creatine kinase | 2 (1.5) | Possible macro creatine kinase (1), Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 1 (0.7) | aMembranous nephropathy (1) | |

| Image and/or pathologic findings | Aortitis revealed by CT | 17 (12) | aG-CSF–related aortitis (14), Takayasu’s arteritis (1), aAortitis associated with MDS (1), Findings associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm (1) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 9 (6.6) | aLymphangiosis carcinomatosa (1), aPneumonitis associated with trastuzumab emtansine (1), Aspiration pneumonia (1), RA-associated interstitial lung disease (1), Interstitial pneumonia associated with a double-positive anti-MDA5 and anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibody (1), Antisynthetase syndrome (1), Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (1), ARDS (1), Atelectasis due to gravitational forces (1) | |

| Osteitis/osteomyelitis | 8 (5.8) | SAPHO syndrome (3), CRMO or CNO (2), Osteitis condensans ilii (2), aAML (1) | |

| Enthesitis | 1 (0.7) | SpA (1) | |

| Sacroiliac joint abnormalities | 1 (0.7) | SpA (1) | |

| Retroperitoneal fibrosis | 1 (0.7) | aRetroperitoneal bleeding related to malignancy (1) | |

| Multiple intra-abdominal masses | 1 (0.7) | Unknown (1) | |

| Dural thickness | 1 (0.7) | Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Muscle oedema | 1 (0.7) | aPost-radiation changes (1) | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (0.7) | aPulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy (1) | |

| Pericardial effusion | 2 (1.5) | aCarcinomatous pericardial effusion (1), SLE (1) | |

| Granulomatous disease | 2 (1.5) | Unknown (2) | |

| Combination of findings | Eosinophilia and pneumonia | 3 (2.2) | Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia (1), EGPA (1), Unknown (1) |

| Rash/muscle weakness | 2 (1.5) | aDermatomyositis (TIF-1γ antibody positive) (2) | |

| Pleural and pericardial effusion | 1 (0.7) | Systemic lupus erythematosus (1) | |

| Myalgia, renal disorder, ILD | 1 (0.7) | Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Low white blood cell count, anaemia | 1 (0.7) | Copper deficiency anaemia (1) | |

Those related to the malignant tumour itself or the treatment of the malignancy (a). ANCA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; MDA, melanoma differentiation-associated gene; CT, computed tomography; CPPD, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease; PMR, polymyalgia rheumatica; SpA, spondyloarthritis; EN, erythema nodosum; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; SSI, surgical site infection; DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; RNA, ribonucleic acid; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; TIF-1, transcription intermediary factor 1

| Primary manifestations . | n (%) . | Final diagnosis (number of cases) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Arthralgia/arthritis/myalgia | 37 (27) | aSurgical menopause-associated arthralgia (10), Osteoarthritis (7), Gout (3), PMR (3), RA (2), SpA (2), aLemvatinib-associated arthralgia (1), aParaneoplastic polyarthritis (1), aPathological fracture (1), CPPD (1), Calcific tendinopathy of the shoulder (1), aEN due to Hodgkin lymphoma (1), Fibromyalgia (1), Subacromial impingement syndrome (1), De Quervain tendinopathy (1), Trigger finger (1) |

| Dermatological problems | 16 (12) | aOlaparib-induced EN (10), *Cutaneous irAEs (1), Drug eruption (1), DLE (1), aParaneoplastic dermatoses (1), Peripheral cyanosis (1), Unknown (1) | |

| Fever of unknown origin/Fever | 15 (11) | Self-limiting fever (6), Drug fever (2), MPA (2), SSI (1), aG-CSF–related aortitis (1), RA (1), CPPD (1), Chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection (1) | |

| Neurological problem | 2 (1.5) | aIntrathecal MTX-induced neurotoxicity (1), aChemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (1) | |

| Recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations | 2 (1.5) | aBehçet’s syndrome-associated with MDS (1), Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (1) | |

| Multiple lymphadenopathy | 1 (0.7) | Sarcoidosis (1) | |

| Finger deformity | 1 (0.7) | Jaccoud’s arthropathy (1) | |

| Laboratory findings | Positive for autoantibodies | 6 (4.4) | Asymptomatic anticentromere antibody carrier (2), Nonspecific antinuclear antibody positive (1), aANCA false positive due to malignancy (1), Antiphospholipid antibody carrier (1), Asymptomatic MDA-5 antibody carrier or false positive (1) |

| Elevation in creatine kinase | 2 (1.5) | Possible macro creatine kinase (1), Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 1 (0.7) | aMembranous nephropathy (1) | |

| Image and/or pathologic findings | Aortitis revealed by CT | 17 (12) | aG-CSF–related aortitis (14), Takayasu’s arteritis (1), aAortitis associated with MDS (1), Findings associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm (1) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 9 (6.6) | aLymphangiosis carcinomatosa (1), aPneumonitis associated with trastuzumab emtansine (1), Aspiration pneumonia (1), RA-associated interstitial lung disease (1), Interstitial pneumonia associated with a double-positive anti-MDA5 and anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibody (1), Antisynthetase syndrome (1), Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (1), ARDS (1), Atelectasis due to gravitational forces (1) | |

| Osteitis/osteomyelitis | 8 (5.8) | SAPHO syndrome (3), CRMO or CNO (2), Osteitis condensans ilii (2), aAML (1) | |

| Enthesitis | 1 (0.7) | SpA (1) | |

| Sacroiliac joint abnormalities | 1 (0.7) | SpA (1) | |

| Retroperitoneal fibrosis | 1 (0.7) | aRetroperitoneal bleeding related to malignancy (1) | |

| Multiple intra-abdominal masses | 1 (0.7) | Unknown (1) | |

| Dural thickness | 1 (0.7) | Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Muscle oedema | 1 (0.7) | aPost-radiation changes (1) | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (0.7) | aPulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy (1) | |

| Pericardial effusion | 2 (1.5) | aCarcinomatous pericardial effusion (1), SLE (1) | |

| Granulomatous disease | 2 (1.5) | Unknown (2) | |

| Combination of findings | Eosinophilia and pneumonia | 3 (2.2) | Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia (1), EGPA (1), Unknown (1) |

| Rash/muscle weakness | 2 (1.5) | aDermatomyositis (TIF-1γ antibody positive) (2) | |

| Pleural and pericardial effusion | 1 (0.7) | Systemic lupus erythematosus (1) | |

| Myalgia, renal disorder, ILD | 1 (0.7) | Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Low white blood cell count, anaemia | 1 (0.7) | Copper deficiency anaemia (1) | |

| Primary manifestations . | n (%) . | Final diagnosis (number of cases) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Arthralgia/arthritis/myalgia | 37 (27) | aSurgical menopause-associated arthralgia (10), Osteoarthritis (7), Gout (3), PMR (3), RA (2), SpA (2), aLemvatinib-associated arthralgia (1), aParaneoplastic polyarthritis (1), aPathological fracture (1), CPPD (1), Calcific tendinopathy of the shoulder (1), aEN due to Hodgkin lymphoma (1), Fibromyalgia (1), Subacromial impingement syndrome (1), De Quervain tendinopathy (1), Trigger finger (1) |

| Dermatological problems | 16 (12) | aOlaparib-induced EN (10), *Cutaneous irAEs (1), Drug eruption (1), DLE (1), aParaneoplastic dermatoses (1), Peripheral cyanosis (1), Unknown (1) | |

| Fever of unknown origin/Fever | 15 (11) | Self-limiting fever (6), Drug fever (2), MPA (2), SSI (1), aG-CSF–related aortitis (1), RA (1), CPPD (1), Chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection (1) | |

| Neurological problem | 2 (1.5) | aIntrathecal MTX-induced neurotoxicity (1), aChemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (1) | |

| Recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations | 2 (1.5) | aBehçet’s syndrome-associated with MDS (1), Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (1) | |

| Multiple lymphadenopathy | 1 (0.7) | Sarcoidosis (1) | |

| Finger deformity | 1 (0.7) | Jaccoud’s arthropathy (1) | |

| Laboratory findings | Positive for autoantibodies | 6 (4.4) | Asymptomatic anticentromere antibody carrier (2), Nonspecific antinuclear antibody positive (1), aANCA false positive due to malignancy (1), Antiphospholipid antibody carrier (1), Asymptomatic MDA-5 antibody carrier or false positive (1) |

| Elevation in creatine kinase | 2 (1.5) | Possible macro creatine kinase (1), Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 1 (0.7) | aMembranous nephropathy (1) | |

| Image and/or pathologic findings | Aortitis revealed by CT | 17 (12) | aG-CSF–related aortitis (14), Takayasu’s arteritis (1), aAortitis associated with MDS (1), Findings associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm (1) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 9 (6.6) | aLymphangiosis carcinomatosa (1), aPneumonitis associated with trastuzumab emtansine (1), Aspiration pneumonia (1), RA-associated interstitial lung disease (1), Interstitial pneumonia associated with a double-positive anti-MDA5 and anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibody (1), Antisynthetase syndrome (1), Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (1), ARDS (1), Atelectasis due to gravitational forces (1) | |

| Osteitis/osteomyelitis | 8 (5.8) | SAPHO syndrome (3), CRMO or CNO (2), Osteitis condensans ilii (2), aAML (1) | |

| Enthesitis | 1 (0.7) | SpA (1) | |

| Sacroiliac joint abnormalities | 1 (0.7) | SpA (1) | |

| Retroperitoneal fibrosis | 1 (0.7) | aRetroperitoneal bleeding related to malignancy (1) | |

| Multiple intra-abdominal masses | 1 (0.7) | Unknown (1) | |

| Dural thickness | 1 (0.7) | Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Muscle oedema | 1 (0.7) | aPost-radiation changes (1) | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (0.7) | aPulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy (1) | |

| Pericardial effusion | 2 (1.5) | aCarcinomatous pericardial effusion (1), SLE (1) | |

| Granulomatous disease | 2 (1.5) | Unknown (2) | |

| Combination of findings | Eosinophilia and pneumonia | 3 (2.2) | Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia (1), EGPA (1), Unknown (1) |

| Rash/muscle weakness | 2 (1.5) | aDermatomyositis (TIF-1γ antibody positive) (2) | |

| Pleural and pericardial effusion | 1 (0.7) | Systemic lupus erythematosus (1) | |

| Myalgia, renal disorder, ILD | 1 (0.7) | Nonspecific change (1) | |

| Low white blood cell count, anaemia | 1 (0.7) | Copper deficiency anaemia (1) | |

Those related to the malignant tumour itself or the treatment of the malignancy (a). ANCA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; MDA, melanoma differentiation-associated gene; CT, computed tomography; CPPD, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease; PMR, polymyalgia rheumatica; SpA, spondyloarthritis; EN, erythema nodosum; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; SSI, surgical site infection; DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; RNA, ribonucleic acid; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; TIF-1, transcription intermediary factor 1

Consultation on the management of underlying rheumatic diseases

Table 5 shows the underlying rheumatic diseases of the 42 patients consulted and the consultation details. RA was the most common underlying disease (18 patients, 43%). The consultation was classified into five patterns, with perioperative management being the most common (15 patients, 36%).

| Autoimmune diseases . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| RA | 18 (43) |

| Inflammatory myopathies | 6 (14) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease | 3 (7.1) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 3 (7.1) |

| SLE | 3 (7.1) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 2 (4.8) |

| SAPHO syndrome | 2 (4.8) |

| RS3PE syndrome | 1 (2.4) |

| Behçet’s syndrome | 1 (2.4) |

| Gout | 1 (2.4) |

| Paraneoplastic polyarthritis | 1 (2.4) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1 (2.4) |

| Types of consultations | |

| Perioperative precautions | 15 (36) |

| Treatment for worsening symptoms | 10 (24) |

| Precautions when using antineoplastic agents | 7 (17) |

| Adjustment of therapeutic agents as malignancy progresses | 5 (12) |

| General management questions | 5 (12) |

| Autoimmune diseases . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| RA | 18 (43) |

| Inflammatory myopathies | 6 (14) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease | 3 (7.1) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 3 (7.1) |

| SLE | 3 (7.1) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 2 (4.8) |

| SAPHO syndrome | 2 (4.8) |

| RS3PE syndrome | 1 (2.4) |

| Behçet’s syndrome | 1 (2.4) |

| Gout | 1 (2.4) |

| Paraneoplastic polyarthritis | 1 (2.4) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1 (2.4) |

| Types of consultations | |

| Perioperative precautions | 15 (36) |

| Treatment for worsening symptoms | 10 (24) |

| Precautions when using antineoplastic agents | 7 (17) |

| Adjustment of therapeutic agents as malignancy progresses | 5 (12) |

| General management questions | 5 (12) |

RS3PE, remitting seronegative symmetrical synovitis with pitting oedem.

| Autoimmune diseases . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| RA | 18 (43) |

| Inflammatory myopathies | 6 (14) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease | 3 (7.1) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 3 (7.1) |

| SLE | 3 (7.1) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 2 (4.8) |

| SAPHO syndrome | 2 (4.8) |

| RS3PE syndrome | 1 (2.4) |

| Behçet’s syndrome | 1 (2.4) |

| Gout | 1 (2.4) |

| Paraneoplastic polyarthritis | 1 (2.4) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1 (2.4) |

| Types of consultations | |

| Perioperative precautions | 15 (36) |

| Treatment for worsening symptoms | 10 (24) |

| Precautions when using antineoplastic agents | 7 (17) |

| Adjustment of therapeutic agents as malignancy progresses | 5 (12) |

| General management questions | 5 (12) |

| Autoimmune diseases . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| RA | 18 (43) |

| Inflammatory myopathies | 6 (14) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease | 3 (7.1) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 3 (7.1) |

| SLE | 3 (7.1) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 2 (4.8) |

| SAPHO syndrome | 2 (4.8) |

| RS3PE syndrome | 1 (2.4) |

| Behçet’s syndrome | 1 (2.4) |

| Gout | 1 (2.4) |

| Paraneoplastic polyarthritis | 1 (2.4) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1 (2.4) |

| Types of consultations | |

| Perioperative precautions | 15 (36) |

| Treatment for worsening symptoms | 10 (24) |

| Precautions when using antineoplastic agents | 7 (17) |

| Adjustment of therapeutic agents as malignancy progresses | 5 (12) |

| General management questions | 5 (12) |

RS3PE, remitting seronegative symmetrical synovitis with pitting oedem.

Discussion

A review of consultations by the Department of Onco-Rheumatology over 4 years, comprising 417 cases, revealed that consultations regarding irAEs, a complication of ICI therapy, were the most common, at 55%. Rheumatologists were not simply expected to manage rheumatic irAEs (e.g. arthritis, myositis, and polymyalgia rheumatica-like); they were expected to be involved in the evaluation and treatment of a wide variety of irAEs, such as hepatobiliary toxicities and colitis. Among the patients consulted for treatment of irAEs (other than endocrine irAEs), approximately 25% were treated with glucocorticoids plus one or more second-line therapies (mostly mycophenolate mofetil, biologics, or intravenous immunoglobulin).

During the study period, eight ICIs were available in Japan: two anti-CTLA-4 antibodies (ipilimumab and tremelimumab), three anti-PD-1 antibodies (nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and cemiplimab), and three anti-PD-L1 antibodies (atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab). These ICIs were newly prescribed for 457 patients in 2020, 582 patients in 2021, 811 patients in 2022, and 723 patients in 2023, respectively, at JFCR. With this increase in ICI use came an increase in irAEs, a characteristic side effect of ICIs [5].

Glucocorticoids are the first-line treatment for most irAEs. However, second-line therapies are essential for the management of glucocorticoid-refractory/relapsing irAEs, as previous reports have shown that approximately 20% of patients who developed irAEs requiring glucocorticoids also required additional immunosuppressive agents [6]. In fact, international guidelines provide a variety of second-line therapy options [7–10]. Oncologists may not be familiar with the use of immunosuppressive agents and biologics aside from glucocorticoids. They may also not be accustomed to choosing the most appropriate option in a given situation from among multiple alternatives. Appropriate management of irAEs is crucial not only to improve symptoms but also to consider restarting an ICI that has been interrupted by irAEs; unless an irAE is fatal, most patients can consider resuming an ICI when glucocorticoids are reduced to ≤10 mg prednisone-equivalent daily [10]. In 2018, Calabrese et al. stated that rheumatologists who are familiar with immunology and able to use traditional and biologic immune-based therapies for systemic, multisystem inflammatory conditions are expected to play a central role in the management of various irAEs [11]. The present study confirms this prediction. Despite these expectations, as of 2019, Kostine et al. reported that less than 10% of rheumatologists were confident in their ability to manage irAEs [12]. In the future, the field of oncology will require rheumatologists to become more knowledgeable about ICIs and irAEs.

The second most frequent (33%) reason for consultation after irAEs was for the possibility of rheumatologic disease in patients with undiagnosed conditions. The reasons for the consultations were similar to those standard in the field of rheumatology. However, the final diagnoses included diseases closely related to chemotherapy or surgery for malignant tumours. Of the 17 cases of aortitis revealed by computed tomography, 14 were G-CSF–related aortitis associated with pegfilgrastim, a pegylated form of filgrastim. In addition to these 14 cases, another case was identified following a consultation for unexplained fever, bringing the total number of G-CSF–related aortitis cases to 15. Aortitis is a well-documented side effect of G-CSF administration [13, 14]. Notably, pegfilgrastim has been reported to be associated with aortitis approximately six times more frequently than filgrastim, the conventional form of G-CSF [15]. Among the 15 cases, 14 patients (93%) experienced symptom resolution with either observation alone or treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). One patient, unable to receive NSAIDs because of renal impairment, was treated with glucocorticoids. This patient started with prednisolone at 60 mg 1 mg/kg/day and achieved a rapid taper within 2 weeks.

The findings from this study highlight an important clinical insight: when a patient with cancer exhibits symptoms of aortitis, G-CSF–related aortitis (particularly that associated with pegfilgrastim) should be strongly considered. Unlike giant cell arteritis or Takayasu’s arteritis, initial management should prioritise symptomatic treatment with NSAIDs, avoiding glucocorticoids when feasible. However, given the lack of international treatment guidelines for G-CSF–related aortitis, further studies are needed to validate this approach of avoiding glucocorticoids as initial treatment.

Ten of the 11 cases of erythema nodosum were induced by olaparib. Olaparib is a molecular-targeted drug classified as a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for ovarian cancer in 2014 and has since been used for ovarian, breast, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers [16]. Olaparib is not a common causative agent of erythema nodosum [17, 18] and may be unfamiliar to rheumatologists. However, erythema nodosum has recently been reported as a side effect of olaparib [19, 20], constituting a rheumatic side effect of a relatively new antineoplastic drug and a condition of which rheumatologists should be aware. Among 10 patients who developed olaparib-related erythema nodosum, 5 experienced persistent symptoms as long as olaparib treatment continued. In some of these cases, NSAIDs were attempted but showed limited effectiveness. However, upon initiation of colchicine at a dose of 0.5–1.0 mg/day, erythema nodosum resolved, allowing these patients to continue olaparib while maintaining colchicine therapy. In four other patients, NSAIDs or colchicine were used temporarily, and erythema nodosum did not recur despite ongoing olaparib administration. One patient achieved symptom resolution after switching from olaparib to another PARP inhibitor, niraparib. While the approach of continuing olaparib with maintenance colchicine therapy in cases of persistent or refractory erythema nodosum is not yet recognised as a standard treatment, we believe it warrants further investigation in a larger cohort to evaluate its potential benefits.

The most common cause of arthralgia associated with malignancy was surgical menopause-associated arthralgia. Surgical menopause is defined as bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (with or without concurrent hysterectomy) prior to menopause. Compared with women in natural menopause, women in surgical menopause experience more rapid decreases in the levels of oestradiol and other ovarian hormones. As a result, vasomotor symptoms (e.g. hot flashes and night sweats) are more severe, and arthralgia may occur, along with mood disorders, sleep disturbances, and sexual dysfunction [21]. In this study, patients diagnosed with surgical menopause-associated arthralgia had new-onset and prolonged arthralgia (especially in finger interphalangeal joints) after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. In addition to physical examination, some patients underwent musculoskeletal ultrasound; based on the absence of synovitis and the absence of X-ray findings suggestive of osteoarthritis, the exclusionary diagnosis of surgical menopause-associated arthralgia was made. It is not clear why there were no cases of arthralgia associated with antineoplastic drugs – including aromatase inhibitors, anti-androgens, tamoxifen, and taxanes such as paclitaxel – even though these drugs have been reported to be common causes of arthralgia [4, 22]. As arthralgia associated with antineoplastic drugs is a well-known side effect, oncologists may be accustomed to dealing with it themselves. Only one case of paraneoplastic polyarthritis was recorded in our consultations, and it is generally considered rare [23].

It is also noteworthy that rare autoinflammatory bone diseases, such as SAPHO syndrome, CRMO, and CNO, were diagnosed at frequencies similar to those of typical rheumatic diseases, such as RA, polymyalgia rheumatica, and SLE. It has been reported that these cases can be mistaken for bone tumours [24–27], and the present study also revealed that these cases may be referred to cancer centres without being diagnosed.

There were relatively few consultations regarding the management of underlying rheumatic diseases. This may be mainly because non-urgent problems – such as perioperative precautions, adjustment of treatment in case of gradual worsening of symptoms, and consultation on precautions when using antineoplastic drugs – can be resolved by contacting the rheumatologist whom the patient usually visits by phone or referral letter. As such, managing underlying rheumatic diseases may be a low priority for an onco-rheumatologist. However, understanding the guidelines for perioperative drug regimens [28] and being familiar with the characteristics of antineoplastic drugs are valuable for high-quality collaboration between rheumatologists and oncologists, and will be helpful in situations where immediate decisions are necessary.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the limited number of cases from a single institution may not represent a complete picture of the emerging field of onco-rheumatology. For example, although managing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)-related inflammatory and autoinflammatory diseases is an essential skill for onco-rheumatologists, we identified only one case of Behçet’s syndrome and one case of aortitis associated with MDS. Additionally, no cases of vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic mutation syndrome – an emerging topic in rheumatology [29] – were observed. Second, our findings reflect data from a specialised cancer hospital with unique characteristics. Like many cancer centres in Japan, our institution lacks specialists in autoimmune liver diseases and inflammatory bowel diseases, and we have limited access to neurologists. Consequently, the onco-rheumatologists often manage a broad range of nonrheumatic irAEs. In contrast, at institutions with a wider range of specialists, the role of an onco-rheumatologist in irAE management may be more limited. Nonetheless, given the occurrence of simultaneous or sequential multiorgan irAEs, we believe that the involvement of an onco-rheumatologist with expertise in systemic inflammatory diseases remains crucial. Third, the number of irAE consultations does not fully capture the overall incidence of irAEs at our institution because only patients referred to the Department of Onco-Rheumatology were included. For example, cutaneous irAEs managed with topical agents were often treated solely by oncologists and dermatologists, and pulmonary irAEs were often treated solely by oncologists and pulmonologists. Thus, the irAEs in this study may not reflect overall trends and frequencies at our institution. Fourth, the absence of a dedicated onco-rheumatology inpatient ward limited our ability to comprehensively manage certain cases. For instance, while managing malignancy-associated dermatomyositis, we primarily provided diagnostic consultations, with treatment often transferred to hospitals with dedicated rheumatology wards. This limitation hindered our development of strategies to balance cancer treatment and dermatomyositis management, a crucial skill for onco-rheumatologists. Finally, this study was not specifically designed to investigate the detailed aspects of irAEs, particularly the impact of rheumatic versus nonrheumatic irAEs on cancer prognosis. Future longitudinal studies are warranted to explore whether cancer outcomes are influenced by the nature of irAEs.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the content of consultations in a department specialising in onco-rheumatology. With the development of the new field of onco-rheumatology, it has become clear that progress in cancer immunotherapy has created exceptionally high expectations for rheumatologists to play a central role in the management of a wide range of irAEs that extend beyond rheumatic irAEs. Rheumatologists will be required to become familiar with ICIs and irAEs. Knowledge of autoimmune/rheumatologic conditions associated with oncotherapy, such as G-CSF–associated aortitis, olaparib-associated erythema nodosum, and surgical menopause-associated arthralgia, will be necessary for accurate diagnosis. We found that rare autoinflammatory bone diseases, such as SAPHO syndrome, CRMO, and CNO, may be referred to the cancer centre as bone tumour mimics.

In terms of future directions, investigating the potential for improved outcomes through onco-rheumatologist intervention may be valuable. Emphasising this area could offer important insights into the evolving role of onco-rheumatologists in patient care and help inform multidisciplinary approaches for managing cancer patients with concurrent rheumatologic complications.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Takeo Sato for useful advice and discussions. We also thank Amanda Holland, PhD, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Koichi Takeda: Conceptualisation, Formal analysis and investigation, Writing – original draft preparation, Resources. Taro Shiga: Writing – review and editing, Resources, Project administration and supervision.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.