-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Minju M Lee, Charles C Steidel, Gabriel Brammer, Natascha Förster-Schreiber, Alvio Renzini, Daizhong Liu, Rodrigo Herrera-Camus, Thorsten Naab, Sedona H Price, Hannah Übler, Sebastián Arriagada-Neira, Georgios Magdis, High dust content of a quiescent galaxy at z ∼ 2 revealed by deep ALMA observation, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 527, Issue 4, February 2024, Pages 9529–9547, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stad3718

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

We report the detection of cold dust in an apparently quiescent massive galaxy (log (M⋆/M⊙) ≈ 11) at z ∼ 2 (G4). The source is identified as a serendipitous 2 mm continuum source in a deep ALMA observation within the field of Q2343-BX610, a z = 2.21 massive star-forming disc galaxy. Available multiband photometry of G4 suggests redshift of z ∼ 2 and a low specific star formation rate (sSFR), log (SFR/M⋆)[yr−1] ≈ −10.2, corresponding to ≈1.2 dex below the z = 2 main sequence (MS). G4 appears to be a peculiar dust-rich quiescent galaxy for its stellar mass (log (Mdust/M⋆) = −2.71 ± 0.26), with its estimated mass-weighted age (∼1–2 Gyr). We compile z ≳ 1 quiescent galaxies in the literature and discuss their age–ΔMS and log (Mdust/M⋆)–age relations to investigate passive evolution and dust depletion scale. A long dust depletion time and its morphology suggest morphological quenching along with less efficient feedback that could have acted on G4. The estimated dust yield for G4 further supports this idea, requiring efficient survival of dust and/or grain growth, and rejuvenation (or additional accretion). Follow-up observations probing the stellar light and cold dust peak are necessary to understand the implication of these findings in the broader context of galaxy evolutionary studies and quenching in the early universe.

1 INTRODUCTION

The general picture drawn over the last two decades in galaxy evolutionary study is that galaxies show bimodality in their colours, morphologies, and star formation rates (SFRs). Star-forming galaxies are characterized by bluer colours and disc-like morphology, having rich cold interstellar medium (ISM). In comparison, quiescent galaxies have redder colours, spheroidal morphology (or higher fraction of bulge component) with less gas (e.g. Strateva et al. 2001; Kauffmann et al. 2003; Baldry et al. 2004; Balogh et al. 2004; Bell et al. 2004; Saintonge et al. 2011; Wuyts et al. 2011; Young et al. 2011). In line with this picture, extensive surveys of cold ISM in star-forming galaxies up to z ∼ 2 have shown that the cosmic star-formation activity (e.g. Madau & Dickinson 2014) is primarily governed by the available gas within (and outside that falls into) the galaxies (e.g. Tacconi, Genzel & Sternberg 2020; Walter et al. 2020; and references therein).

Therefore, it has been generally considered that a key aspect of quenching star formation is the reduction of cold ISM reservoirs. Theories and simulations proposed that it can be achieved by expulsion via outflows or depletion via star formation (e.g. Silk & Rees 1998; Di Matteo, Springel & Hernquist 2005; Springel, Di Matteo & Hernquist 2005). Active galactic nuclei (AGNs) have been regarded as a preferable agent of outflows in the high-mass (log (M⋆/M⊙) ≳ 10.7) regime, which is also observationally indicated at z ∼ 1−2 (e.g. Förster Schreiber et al. 2018 and references therein; Concas et al. 2022). Supernova feedback (outflow and shock) would be more efficient in sweeping the gas out of the galaxy in a low-mass regime (e.g. Dekel & Silk 1986; Efstathiou 2000). These two mechanisms were taken to explain the mismatch between the observed stellar mass function and halo mass function high-mass (AGN) and low-mass (supernovae) regimes early on in galaxy evolution studies (e.g. White & Rees 1978; White & Frenk 1991; Balogh et al. 2001; Springel & Hernquist 2003; see also reviews of Somerville & Davé 2015; Naab & Ostriker 2017). A remarkable consistency in the cosmic evolution of the black hole accretion activity further implies a possible role of AGN in the interplay of cosmic gas and star formation evolution. Additional mechanisms that may contribute to quenching without exhausting the available gas reservoir include heating of the halo gas (via virial shock or kinetic mode feedback from AGN) preventing further infall on to the galaxy by counteracting cooling (e.g. Rees & Ostriker 1977; Blumenthal et al. 1984; Birnboim & Dekel 2003; Bower et al. 2006; Croton et al. 2006; Somerville et al. 2008) or stabilization by a massive central mass component (e.g. Martig et al. 2009; Ceverino, Dekel & Bournaud 2010).

However, at z ≳ 1, when the most massive quiescent galaxies start to form (e.g. Thomas et al. 2005, 2010), observations provided inconclusive results to explain the connection between the removal of cold ISM and these potential quenching mechanisms. Stacking analysis studies found that there is a non-negligible amount of cold dust and gas in quiescent galaxies at z = 1−3 (Gobat et al. 2017; Magdis et al. 2021; Blánquez-Sesé et al. 2023), while individual observations on quiescent galaxies did not offer a convergence with cold gas and dust content in the high-redshift quiescent galaxies (Sargent et al. 2015; Hayashi et al. 2018; Belli et al. 2021; Caliendo et al. 2021; Kalita et al. 2021; Whitaker et al. 2021; Williams et al. 2021; Gobat et al. 2022; Morishita et al. 2022; Suzuki et al. 2022). The detection and non-detection of cold gas in post-starburst galaxies at z > 0.5 also raised a similar question germane to quenching at high redshift (Suess et al. 2017; Spilker et al. 2018; Bezanson et al. 2022; Woodrum et al. 2022). Overall, there is a large scatter of the observed dust and gas content in the individual quiescent and post-starburst galaxies at high redshift. These observational results perhaps indicate that quenching star formation may not occur from a single mechanism or cannot be explained with simplified bimodal origins, making the full picture of galaxy evolution more complicated.

Whatever the feedback mechanisms are, recent studies advocated the need for bimodal quenching paths in the time scales – slow and fast – both in observations (e.g. Barro et al. 2013; Schawinski et al. 2014; Yesuf et al. 2014; Barro et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2018; Belli, Newman & Ellis 2019; Carnall et al. 2019; Tacchella et al. 2022) and simulations (e.g. Rodríguez Montero et al. 2019). At z ≳ 2, spectroscopically confirmed massive, quiescent galaxies corroborated the fast quenching mode (e.g. Glazebrook et al. 2017; Forrest et al. 2020; Stockmann et al. 2020; Valentino et al. 2020). How do dust and cold ISM respond to this bimodal quenching time scale and especially fast quenching paths at high redshift? And what can we learn from the constraints of observed dust in high-redshift quiescent galaxies to understand galaxy evolution?

This work builds upon a very deep observation with ALMA (∼20 h in total) – one of the deepest images ever made with ALMA at this redshift – targeting a main-sequence galaxy at z = 2.21 (Q2343-BX610). We detect six continuum sources above peak signal-to-noise ratio (S/Npeak) of four, five of which were made serendipitously. This paper delivers the first analysis of these sources, focusing on the discovery of a candidate dust-rich quiescent galaxy at z ∼ 2. Comparing its properties with other high-redshift quiescent galaxies available, we allude to ideas to answer the questions above.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the ALMA observation, data analysis, and flux measurement of the continuum sources. Section 3 illustrates the multiwavelength (optical and near-infrared, opt/NIR) data (Section 3.1), and spectral energy distribution (SED) analysis of the quiescent galaxy candidate. It includes the photometric redshift estimate (Section 3.2), and SED fitting (Section 3.3). Section 4 describes overall SED fitting results, SFR constraints (Section 4.1), UVJ colour and stellar age (Section 4.2), dust mass measurements (Section 4.3). Section 5 delves into the details of the identified quiescent galaxy, by comparing it with respect to high redshift quiescent galaxies in terms of age and offset from the main-sequence (Section 5.1) and dust-to-stellar mass ratio at given age (Section 5.2). We present a discussion of the potential quenching mechanisms (Section 5.3) of G4, followed by the potential origin of the observed dust at z ≳ 1 (Section 5.4). Finally, we conclude and summarize our results in Section 6. We adopt a standard ΛCDM cosmology with H0 = 70 km s−1 Mpc−1 and Ωm = 0.3 and Chabrier initial mass function (IMF; Chabrier 2003).

2 OBSERVATIONS AND SOURCE DETECTION

The original programme aimed to study one of the well-studied, typical main-sequence galaxies at z = 2.21, Q2343-BX610 (hereafter BX610), at an angular resolution of 0.2 arcsec (ID: ADS/JAO.ALMA#2019.1.01362.S, PI: R. Herrera-Camus). Band 4 receivers were used to cover both CO (4−3) and [C i]|$\, (^3P_1\, -\, ^{3}P_0)$| (hereafter, [C i]) emissions to study the cold ISM properties and gas kinematics to resolve the inner structure of the galaxy down to ∼1.5 kpc scale, close to the Toomre length at this redshift. Therefore, antenna configuration was chosen to achieve ≈0.2 arcsec resolution, with baseline lengths ranging between 15 m and 3.7 km using 44–48 antennas. On-source time was 13.6 h (≃20 h in total including the overheads), which enables the characterization of the cold molecular gas kinematics including radial gas inflow in addition to the global ordered rotational motions for the target galaxy BX610. The detailed analyses on the main target, BX610, are presented by Genzel et al. (2023) and Arriagada-Neira et al. (in preparation). This deep integration then allowed us to detect other sources within the ALMA field of view (FoV) accordingly.

Four spectral windows (SPWs) are used, two of each placed in the upper and the lower sideband, respectively, to cover the lines and the underlying continuum. Two SPWs are set in the Frequency-Division Mode to detect the redshifted CO (4−3) and [C i] with a channel width of 3.906 MHz (∼8.2 km s−1) covering 1.875 GHz bandwidth. The remaining two SPWs are observed in the Time-Division Mode (TDM) with a 2.0-GHz bandwidth at the 15.6-MHz resolution to cover the dust continuum at 2 mm.

We used casa (McMullin et al. 2007) version 6.1.1.15 for the calibration of visibility data and imaging. For visibility calibration, we used the pipeline script provided by the ALMA Regional Center staff. Continuum and cube images are produced by casa task, |$\tt {tclean}$|, and deconvolved down to 2σ noise level, which is initially measured from the dirty map.

The continuum image is obtained using the line-free SPWs observed in the TDM mode. The synthesized beam is 0.23 arcsec × 0.22 arcsec, 0.22 arcsec × 0.20 arcsec, and 0.22 arcsec × 0.21 arcsec for CO (4−3), [C i] and 2 mm continuum with natural weighting, respectively. Tapered images are also created by setting uvtaper parameters of 0.15 arcsec and 0.35 arcsec in the |$\tt {tclean}$| task to check the presence of extended emissions. We then circularize the beam for these tapered maps, by specifying the restoringbeam parameter as 0.29 and 0.48 arcsec, respectively; so the final beams for the tapered images are 0.29 arcsec × 0.29 arcsec and 0.48 arcsec × 0.48 arcsec. With the natural weighting, the typical continuum noise level around the phase centre (BX610) is ≈3 μJy beam−1 and it goes up to ≈7 μJy beam−1 around the area close to the farthest continuum-detected source from the centre.

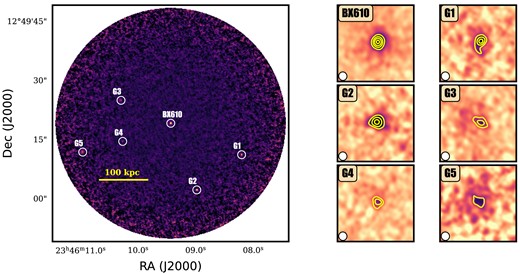

We identified six dust-continuum sources with an S/N of the peak flux greater than four in the ALMA map as shown in Fig. 1. The ALMA photometry is performed based on a fixed aperture and cross-checked by the result with the 2D Gaussian fitting using imfit and the growth curve. We took the aperture size of 1.0 arcsec, encompassing most of the emissions from the sources, which are compact. We list the continuum fluxes for the continuum-detected sources in Table 1.

The ALMA Band 4 continuum image near BX610, where we detect six continuum sources at 2 mm. In the left panel, we show the scale bar to indicate 100 kpc (physical) at z = 2.2, which corresponds to the redshift of BX610 and G1. The right panel size for each galaxy is 2 arcsec × 2 arcsec. The contours are shown from 3σ in steps of 2σ, and the beam (0.22 arcsec × 0.21 arcsec) is shown on the bottom left for the natural weighting clean map. −3σ contours would be shown as a dashed line, which we do not find around the sources.

| Source . | RA . | Dec. . | zphot . | zspec . | |$S_{\rm 2~mm, aperture}^{a}$| . | |$S_{\rm 2~mm, imfit}^{a}$| . | |$S_{\rm 1.2~mm, aperture}^{a,b}$| . | |$S_{\rm 1.2~mm, imfit}^{a,b}$| . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (deg) . | (deg) . | . | . | (mJy) . | (mJy) . | . | . |

| Q2343-BX610 | 356.53932 | 12.82202 | 2.05 | 2.2107 ± 0.0001 | 0.234 ± 0.010 | 0.205 ± 0.009 | 1.72 ± 0.06 | 1.48 ± 0.04 |

| G1 | 356.53419 | 12.81979 | 2.09 | 2.2093 ± 0.0001c | 0.119 ± 0.020 | 0.125 ± 0.021 | – | – |

| G2 | 356.53744 | 12.81731 | – | – | 0.173 ± 0.018 | 0.166 ± 0.017 | – | – |

| G3 | 356.54292 | 12.82363 | – | – | 0.077 ± 0.014 | 0.072 ± 0.016 | 0.50 ± 0.11 | 0.50 ± 0.15 |

| G4 | 356.5428 | 12.82073 | 2.13d | – | 0.037 ± 0.013 | 0.040 ± 0.009 | 0.13 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.09 |

| G5 | 356.54569 | 12.81998 | 0.17 | 3.01? | 0.141 ± 0.029 | 0.175 ± 0.061 | – | – |

| Source . | RA . | Dec. . | zphot . | zspec . | |$S_{\rm 2~mm, aperture}^{a}$| . | |$S_{\rm 2~mm, imfit}^{a}$| . | |$S_{\rm 1.2~mm, aperture}^{a,b}$| . | |$S_{\rm 1.2~mm, imfit}^{a,b}$| . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (deg) . | (deg) . | . | . | (mJy) . | (mJy) . | . | . |

| Q2343-BX610 | 356.53932 | 12.82202 | 2.05 | 2.2107 ± 0.0001 | 0.234 ± 0.010 | 0.205 ± 0.009 | 1.72 ± 0.06 | 1.48 ± 0.04 |

| G1 | 356.53419 | 12.81979 | 2.09 | 2.2093 ± 0.0001c | 0.119 ± 0.020 | 0.125 ± 0.021 | – | – |

| G2 | 356.53744 | 12.81731 | – | – | 0.173 ± 0.018 | 0.166 ± 0.017 | – | – |

| G3 | 356.54292 | 12.82363 | – | – | 0.077 ± 0.014 | 0.072 ± 0.016 | 0.50 ± 0.11 | 0.50 ± 0.15 |

| G4 | 356.5428 | 12.82073 | 2.13d | – | 0.037 ± 0.013 | 0.040 ± 0.009 | 0.13 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.09 |

| G5 | 356.54569 | 12.81998 | 0.17 | 3.01? | 0.141 ± 0.029 | 0.175 ± 0.061 | – | – |

aThe continuum flux is measured using the aperture of 1.00 arcsec in the natural weighting map either based on the aperture photometry and 2D Gaussian fitting using imfit function in casa.

bFor 1.2 mm, we used the ALMA archival data (project code: 2015.1.00250.S) with 0.32 arcsec × 0.29 arcsec resolution for G4 and G3. For Q2343-BX610, we used a tapered map at 0.40 arcsec × 0.37 arcsec based on the investigation of the growth curve.

cG1’s redshift is based on CO (4−3) and [C i], detections and more details of line emitting sources will be presented in Lee et al. (in preparation).

| Source . | RA . | Dec. . | zphot . | zspec . | |$S_{\rm 2~mm, aperture}^{a}$| . | |$S_{\rm 2~mm, imfit}^{a}$| . | |$S_{\rm 1.2~mm, aperture}^{a,b}$| . | |$S_{\rm 1.2~mm, imfit}^{a,b}$| . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (deg) . | (deg) . | . | . | (mJy) . | (mJy) . | . | . |

| Q2343-BX610 | 356.53932 | 12.82202 | 2.05 | 2.2107 ± 0.0001 | 0.234 ± 0.010 | 0.205 ± 0.009 | 1.72 ± 0.06 | 1.48 ± 0.04 |

| G1 | 356.53419 | 12.81979 | 2.09 | 2.2093 ± 0.0001c | 0.119 ± 0.020 | 0.125 ± 0.021 | – | – |

| G2 | 356.53744 | 12.81731 | – | – | 0.173 ± 0.018 | 0.166 ± 0.017 | – | – |

| G3 | 356.54292 | 12.82363 | – | – | 0.077 ± 0.014 | 0.072 ± 0.016 | 0.50 ± 0.11 | 0.50 ± 0.15 |

| G4 | 356.5428 | 12.82073 | 2.13d | – | 0.037 ± 0.013 | 0.040 ± 0.009 | 0.13 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.09 |

| G5 | 356.54569 | 12.81998 | 0.17 | 3.01? | 0.141 ± 0.029 | 0.175 ± 0.061 | – | – |

| Source . | RA . | Dec. . | zphot . | zspec . | |$S_{\rm 2~mm, aperture}^{a}$| . | |$S_{\rm 2~mm, imfit}^{a}$| . | |$S_{\rm 1.2~mm, aperture}^{a,b}$| . | |$S_{\rm 1.2~mm, imfit}^{a,b}$| . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (deg) . | (deg) . | . | . | (mJy) . | (mJy) . | . | . |

| Q2343-BX610 | 356.53932 | 12.82202 | 2.05 | 2.2107 ± 0.0001 | 0.234 ± 0.010 | 0.205 ± 0.009 | 1.72 ± 0.06 | 1.48 ± 0.04 |

| G1 | 356.53419 | 12.81979 | 2.09 | 2.2093 ± 0.0001c | 0.119 ± 0.020 | 0.125 ± 0.021 | – | – |

| G2 | 356.53744 | 12.81731 | – | – | 0.173 ± 0.018 | 0.166 ± 0.017 | – | – |

| G3 | 356.54292 | 12.82363 | – | – | 0.077 ± 0.014 | 0.072 ± 0.016 | 0.50 ± 0.11 | 0.50 ± 0.15 |

| G4 | 356.5428 | 12.82073 | 2.13d | – | 0.037 ± 0.013 | 0.040 ± 0.009 | 0.13 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.09 |

| G5 | 356.54569 | 12.81998 | 0.17 | 3.01? | 0.141 ± 0.029 | 0.175 ± 0.061 | – | – |

aThe continuum flux is measured using the aperture of 1.00 arcsec in the natural weighting map either based on the aperture photometry and 2D Gaussian fitting using imfit function in casa.

bFor 1.2 mm, we used the ALMA archival data (project code: 2015.1.00250.S) with 0.32 arcsec × 0.29 arcsec resolution for G4 and G3. For Q2343-BX610, we used a tapered map at 0.40 arcsec × 0.37 arcsec based on the investigation of the growth curve.

cG1’s redshift is based on CO (4−3) and [C i], detections and more details of line emitting sources will be presented in Lee et al. (in preparation).

We checked the publicly available data on the ALMA archive observed at shallower depths and different configurations (#2013.1.00059S, #2017.1.00856.S, #2017.1.01045.S) in Band 4. We confirmed that BX610’s flux values in those programmes are consistent with those reported here within the errors.1 We note that the BX610’s 2 mm continuum flux measured in Brisbin et al. (2019) is a factor of ∼2 larger than our measurement at the same frequency. Although it is unclear whether this difference can be attributed to calibration errors in the flux in the Plateau de Bure Interferometer (PdBI) observations, our flux estimate is the conservative estimate of the total flux. This ensures our later discussion on the dust mass and dust-to-stellar mass ratio for G4.

We also checked the ALMA archive if there is additional data available at higher frequencies, finding that two ALMA project (#2015.1.00250.S and #2019.1.00853.S) covers three galaxies (BX610, G3, and G4) at Band 6 (1.2 mm) within the field of view. G3 and G4 are on the edge of the coverage where the sensitivity is degraded by 50–60 per cent with respect to the central position. We find ≈5σ and ≈3σ peak features in G3 and G4, respectively, using #2015.1.00250.S. The resolution of #2019.1.00853.S’s Band 6 programme is 0.087 arcsec × 0.076 arcsec for natural weighting, where we do not find a noticeable signal at the position of G4 but G3. Photometry of Band 6 is also listed in Table 1 using the same method applied in the 2 mm map. We note, however, that the uncertainty of the photometry is larger due to the low S/Ns compared to the 2 mm detection that needs deeper follow-up observations.

This paper will focus on the analyses of G4. Counterpart identification is performed on all objects described in the next section. We defer the full discussions on other continuum and line-detected sources from the ALMA programme to another paper (Lee et al. in preparation). Instead, we present a summary of the spectroscopic redshift of the 2 mm-continuum-detected galaxies as follows and in Table 1. Among six ALMA continuum sources, CO and [C i], lines are detected in BX610 and G1, and one line for another (G5). The redshift of G1 is 2.21 based on CO (4−3) and [C i] line detections, confirming it being at the same redshift as BX610. With a single line and the photometric redshift described below, G5 is less likely associated with the BX610-G1 pair system and is rather a background source at z ≈ 3.01.

3 PHOTOMETRIC REDSHIFTS AND SED FITTING

3.1 Counterpart identification and photometry at shorter wavelengths

We gathered all available data from optical and near-/mid-infrared (NIR/MIR) observations from the ground (Un, G, |$\mathcal {R}_s$|, J, H, Ks) and space [Hubble Space Telescope (HST); F814W/F110W/F140W, Spitzer; IRAC Channel 2, MIPS 24 μm] and archival data from ALMA. Due to the very different point spread functions (PSFs; ranging from ≈0.15 arcsec to ≈5.5 arcsec) in different wavelengths, we choose to use different, reasonably large aperture sizes and correct it to recover the total fluxes (so that colour corrections have less effect on the photometry for the same aperture correction) described as follows.

Un, G, and |$\mathcal {R}_s$| band images were obtained by the Palomar telescope using the Large Format Camera (LFC) in 2001. The description of the data and analysis of the observations (Q2343 field) is available in Steidel et al. (2004) and the references therein. The Ks images are also from the Palomar 5 m telescope, taken with the Wide Field Infrared Camera (WIRC) in 2003 and 2004. We refer the readers to Erb et al. (2006) for the details of the observations and data analyses. We used J and H band images taken from Magellan/FourStar, obtained in 2013. The J image is a stack of the J2 and J3 intermediate bands, and the H band is a stack of H1 and H2. All of the Magellan data were taken by Gwen Rudie. All of the above photometry was performed using SExtractor, after matching the PSF in all bands (PSF ∼1 arcsec) using the Rs (for most objects) or H band (for very red objects) image as the detection band in ‘dual-band’ mode. This strategy is to optimize the source detection and the corresponding isophotal aperture given that UV colour-selected galaxies, the original main target of the observations, are better detected in the optical band than in the NIR, while the red objects, like G4, are conversely detected in the NIR bands with higher S/N. The magnitudes were corrected from isophotal to ‘total’ using the SExtractormag|$\_$|auto in the relevant detection band.

For HST, we obtained the imaging data from the MAST archive processed with Grizli2 pipeline (Brammer & Matharu 2021; Brammer et al. 2022). The original work using the WFC3/F110W image was presented in Tacchella et al. (2015). We used the Spitzer data from the golfir3 project (Brammer 2022) which generated the Spitzer mosaics from the pipeline processed data. The maps were corrected for the astrometry.

For the HST bands and IRAC 4.5 μm photometry, we used sep4 (version 1.2.0) to extract sources. For the same reason of different PSF, the source extraction and photometry measurement were done independently between the HST and Spitzer maps. For the HST bands, we used the longest wavelength [F110W (G1) or F140W (other galaxies)] available for source detection. We used an aperture of 0.7 arcsec for the photometry in all bands and corrected it to ‘total’ values within an elliptical Kron aperture (Kron 1980). The latter was calculated based on the longest HST bands (F140W or F110W), and the same amount of aperture correction is applied for all the other bands. Given the aperture size is large enough the colour correction is negligible. For the IRAC photometry, we used a larger aperture of 3.6 arcsec and applied the aperture correction that ranges between 10 and 18 per cent. We also checked the curve of growth of the detected galaxies in the IRAC map, confirming that the aperture correction and thus the estimated flux is reasonable.

The MIPS 24 μm data was taken in 2006 and the description of the data reduction is available in Reddy et al. (2010). The MIPS photometry was done using an aperture of 3 arscec centred at the 2 mm sources, and an aperture correction factor of 3.097 was applied based on the MIPS Instrument Handbook (v3.2.1) table 4.13. We obtained the errors based on the median value of standard deviation values given the same aperture taken from random, emission-free positions around the source.

Counterpart identification was performed based on the position of the 2 mm emission. We identified the optical/NIR/MIR counterpart at 0.10–0.24 arcsec offset from the 2 mm peak positions except for G2. Considering the beam and the point-spread function (PSF) sizes of ALMA and optical/NIR observations, and the S/N, we regard the offset as negligible to pin down the counterparts. The offsets would rather be originated from the internal structures and different levels of dust extinction across the galaxy. Finally, we note that there is no additional counterpart identified in the HST imaging within the IRAC and MIPS apertures that could contribute to the photometry.

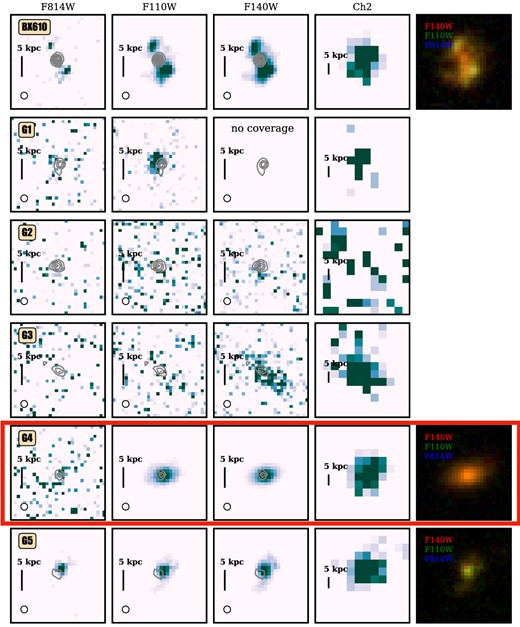

Fig. 2 shows the three HST filter and Spitzer/IRAC Ch2 (4.5 μm) maps overlaying the 2 mm ALMA continuum contours. G2 does not have clear counterparts in any of the bands which may be partly owing to the poor sensitivity (i.e. on the edge of the coverage) around the source. G3 starts to appear in the J, F140W maps and the longer wavelengths, which may imply either an obscured (indicated by the dust detection) or a Lyman/Balmer-break galaxy at higher redshift. G2 and G3 have insufficient data points to perform the full SED fitting and get a good photometric redshift estimate. Follow-up observations of these two are necessary to characterize these two optically dark/faint galaxies. Hereafter, we consider only G4 for further analyses.

Cutout images of HST/F814W, HST/F110W, HST/F140W, and Spitzer/IRAC/ch2 and false colour images (red: F140W, green: F110W, blue: F814W) for all galaxies detected in ALMA 2 mm continuum. The centres of individual images are all at the 2 mm peaks. The Spitzer image is zoomed out to afford the larger pixel size. A scale bar indicating 5 kpc at z = 2.21 is shown. Overlaid contours are ALMA 2 mm continuum detection (starting from 3σ in steps of 2σ) and the bottom left shows the beam size of the ALMA image (0.22 arcsec × 0.21 arcsec). G4 is highlighted in a red box.

3.2 Photometric redshift

We use eazy-py5 (Brammer, van Dokkum & Coppi 2008) to get a first handle on the photo-z estimate. Full details concerning eazy-py and the template set can be found in Brammer, van Dokkum & Coppi (2008) and Kokorev et al. (2022); see also Blanton & Roweis (2007) for the template creation algorithm. Briefly, the best-fitting photo-z is estimated from a linear combination of a set of 13 templates from the Flexible Stellar Populations Synthesis code (fsps; Conroy & Gunn 2010) and one additional template recently obtained from z = 8.5 – ID4590 from Carnall et al. (2023) (namely, carnall|$\_$|sfhz|$\_$|13 template in eazy-py).6 The first thirteen templates are constructed based on redshift-dependent star formation histories (SFHs; a combination of four SFHs) and 2–3 dust models. SFHs that start earlier than the age of the Universe are excluded at a given redshift. We note that there is a limitation of this set-up for eazy-py that there will be z-SFH degeneracies if there are an insufficient number of bands. We explore different SFHs using different SED fitting codes in Appendix A which does not alter our conclusion on G4. The set of thirteen templates is chosen based on an algorithm to reasonably cover the rest-frame colour space following the philosophy of Brammer, van Dokkum & Coppi (2008). The additional template can better explain the extremely strong emission lines seen in early JWST spectra of z>6 galaxies. Templates are constructed on the Chabrier (2003) IMF. Kriek & Conroy (2013) dust attenuation law (dust index δ = −0.1, RV = 3.1) is adopted and its maximum attenuation is set to be redshift dependent. On the fsps 13 templates, a fixed grid of nebular emission lines and continuum from cloudy (v13.03) models are added (metallicity: log (Z/Z⊙) ∈ [ −1.2, 0], ionization parameter log (U) ∈ [−1.64, −2]7; Byler 2018). Given the unconstrained nature of fixed parameters used in eazy-py, we will only use the photo-z information from eazy-py. Finally, a correction for the effect of dust in the Milky Way (E(B − V) = 0.0327) is applied to the templates within eazy-py, pulling the Galactic dust map by Schlafly & Finkbeiner (2011) from dustmaps (Green 2018). For the fitting process, we set minimum and maximum redshifts to 0.01 and 12, respectively, and the redshift step (z_step) to 0.01. Referring to Brammer, van Dokkum & Coppi (2008), we use the extended K-band prior (prior_K_extend.dat) to lower the weight of the low-redshift solution.

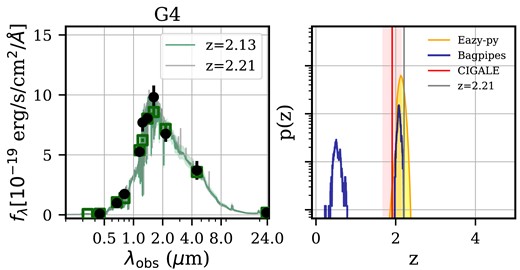

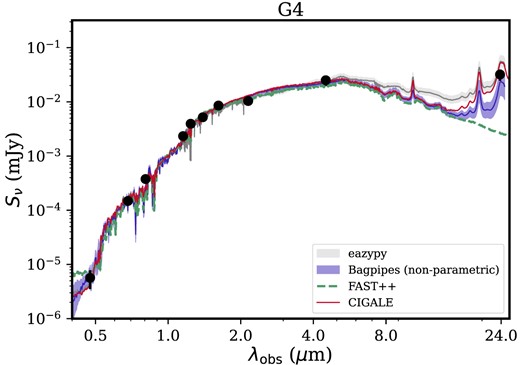

To gain more credentials of photo-z estimate from eazy-py, we also run bagpipes and cigale using different SFH. The details of the SED results and the set-up to fit redshift are summarized in Appendix A. In general, they agree well with each other, giving the best-fiting photometric redshift of z ≃ 2 for G4. We overlay the final results in Fig. 3 for the P(z) distribution from eazy-py, bagpipes, and cigale photo-z constraint. Hereafter, we consider G4 to be at z ∼ 2.

Photometric redshift estimation from SED fitting for G4. The best-fitting SED template fit from eazy-py is shown on its left panel, and the best-fitting redshift is indicated as green lines. The grey line is the best fit at a fixed redshift of z = 2.21, the spectroscopic redshift of BX610 and G1. Black-filled circles show the observed flux and open squares show the best-fitting model convolved with the filter response. On the right panel, P(z) distribution of the eazy-py (yellow shaded) and bagpieps (dark blue, uniform redshift prior), and cigale (red shaded) are shown. See also Table A1 in Appendix A.

3.3 SED fitting

Given the consistency between the estimated photo-z from different SED codes, we use bagpipes8 (Carnall et al. 2018), fast++ 9 (Kriek et al. 2009; Schreiber et al. 2018) and cigale10 (Boquien et al. 2019) by fixing the redshift based on the best-fitting photometric redshift from eazy-py (z = 2.13). The photometric data used for G4’s SED fitting is summarized in Table 2. We use three different codes to see if these codes are able to fit the G4’s photometry and thus strengthen the reliability of the overall results. We regard the results with fixed redshift as the best estimate from SED, which is summarized in Table 3. In Appexdix A, we explore the impact of fitting the photometry with the redshift left free to vary. The comparison indicates reasonable agreement between parameters derived with and without fixing the redshift, which does not alter the overall conclusion that G4 is a massive quiescent galaxy at z ∼ 2 with low specific star-formation rate log (sSFR/yr−1) ≲ −12.5.

| Photometric band . | Un . | G . | Rs . | f814w . | f110w . | J . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux (μJy) | – | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.149 ± 0.017 | 0.377 ± 0.044 | 2.333 ± 0.022 | 3.945 ± 0.381 |

| Photometric band | f140w | H | Ks | IRAC2 | MIPS24 | |

| Flux (μJy) | 5.200 ± 0.245 | 8.551 ± 0.825 | 10.375 ± 1.001 | 25.060 ± 5.250 | 32.000 ± 7.600 |

| Photometric band . | Un . | G . | Rs . | f814w . | f110w . | J . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux (μJy) | – | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.149 ± 0.017 | 0.377 ± 0.044 | 2.333 ± 0.022 | 3.945 ± 0.381 |

| Photometric band | f140w | H | Ks | IRAC2 | MIPS24 | |

| Flux (μJy) | 5.200 ± 0.245 | 8.551 ± 0.825 | 10.375 ± 1.001 | 25.060 ± 5.250 | 32.000 ± 7.600 |

| Photometric band . | Un . | G . | Rs . | f814w . | f110w . | J . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux (μJy) | – | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.149 ± 0.017 | 0.377 ± 0.044 | 2.333 ± 0.022 | 3.945 ± 0.381 |

| Photometric band | f140w | H | Ks | IRAC2 | MIPS24 | |

| Flux (μJy) | 5.200 ± 0.245 | 8.551 ± 0.825 | 10.375 ± 1.001 | 25.060 ± 5.250 | 32.000 ± 7.600 |

| Photometric band . | Un . | G . | Rs . | f814w . | f110w . | J . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux (μJy) | – | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.149 ± 0.017 | 0.377 ± 0.044 | 2.333 ± 0.022 | 3.945 ± 0.381 |

| Photometric band | f140w | H | Ks | IRAC2 | MIPS24 | |

| Flux (μJy) | 5.200 ± 0.245 | 8.551 ± 0.825 | 10.375 ± 1.001 | 25.060 ± 5.250 | 32.000 ± 7.600 |

| G4 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAST++ | Bagpipes | Bagpipes | CIGALE | |

| Redshift | 2.13a | 2.13a | 2.13a | 2.13a |

| log M⋆ | 10.99 ± 0.05 | 11.16 | 11.22 | 11.25 ± 0.10 |

| [11.10,11.21] | [11.17,11.30] | |||

| SFR|$_{\rm SED}^{\dagger }$|d | 0.02 | 0.00b | 0.01b | 1.3e−4 ± 7.04e−5b,c |

| [0.00,0.00] | [0.00,0.04] | |||

| log(ΔMS)d | −3.79 | −69.68 | −4.40 | −6.20 |

| log (age)e | 9.15 | 8.83 | 9.27 | 9.26 ± 0.20 |

| [8.79,8.97] | [9.20,9.30] | |||

| SFH | Delayed-τ | Double-power law | Non-parametric | Delayed-τ |

| AV | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.57 ± 0.10 |

| [0.50,0.93] | [0.33,0.72] | |||

| χ2f | 2.1 | 15.8 | 22.4 | 11.3 |

| G4 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAST++ | Bagpipes | Bagpipes | CIGALE | |

| Redshift | 2.13a | 2.13a | 2.13a | 2.13a |

| log M⋆ | 10.99 ± 0.05 | 11.16 | 11.22 | 11.25 ± 0.10 |

| [11.10,11.21] | [11.17,11.30] | |||

| SFR|$_{\rm SED}^{\dagger }$|d | 0.02 | 0.00b | 0.01b | 1.3e−4 ± 7.04e−5b,c |

| [0.00,0.00] | [0.00,0.04] | |||

| log(ΔMS)d | −3.79 | −69.68 | −4.40 | −6.20 |

| log (age)e | 9.15 | 8.83 | 9.27 | 9.26 ± 0.20 |

| [8.79,8.97] | [9.20,9.30] | |||

| SFH | Delayed-τ | Double-power law | Non-parametric | Delayed-τ |

| AV | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.57 ± 0.10 |

| [0.50,0.93] | [0.33,0.72] | |||

| χ2f | 2.1 | 15.8 | 22.4 | 11.3 |

aBest-fitting photo-z from eazy-py.bAveraged over 100 Myr. cIncluding the ALMA 2 mm data point. dWe note the limitation of the SFR from the SED which is likely to introduce an unrealistically low value of SFR and hence ΔMS especially for the parametric SFH models. The photometry (|$\mathcal {R}_s$|-band) and the best-fitting dust attenuation (AV) suggest the SFR of |$\sim 8\, {\rm M}_{\odot }$| yr−1 and log (ΔMS) ∼−1.6 (see also the main text in Section 4.1). eMass weighted.

fWe quote the absolute χ2 value, as the templates employed (as is the case for many SED fitting codes) are not independent of each other, and degrees of freedom are ill-defined (e.g. Smith et al. 2012).

| G4 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAST++ | Bagpipes | Bagpipes | CIGALE | |

| Redshift | 2.13a | 2.13a | 2.13a | 2.13a |

| log M⋆ | 10.99 ± 0.05 | 11.16 | 11.22 | 11.25 ± 0.10 |

| [11.10,11.21] | [11.17,11.30] | |||

| SFR|$_{\rm SED}^{\dagger }$|d | 0.02 | 0.00b | 0.01b | 1.3e−4 ± 7.04e−5b,c |

| [0.00,0.00] | [0.00,0.04] | |||

| log(ΔMS)d | −3.79 | −69.68 | −4.40 | −6.20 |

| log (age)e | 9.15 | 8.83 | 9.27 | 9.26 ± 0.20 |

| [8.79,8.97] | [9.20,9.30] | |||

| SFH | Delayed-τ | Double-power law | Non-parametric | Delayed-τ |

| AV | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.57 ± 0.10 |

| [0.50,0.93] | [0.33,0.72] | |||

| χ2f | 2.1 | 15.8 | 22.4 | 11.3 |

| G4 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAST++ | Bagpipes | Bagpipes | CIGALE | |

| Redshift | 2.13a | 2.13a | 2.13a | 2.13a |

| log M⋆ | 10.99 ± 0.05 | 11.16 | 11.22 | 11.25 ± 0.10 |

| [11.10,11.21] | [11.17,11.30] | |||

| SFR|$_{\rm SED}^{\dagger }$|d | 0.02 | 0.00b | 0.01b | 1.3e−4 ± 7.04e−5b,c |

| [0.00,0.00] | [0.00,0.04] | |||

| log(ΔMS)d | −3.79 | −69.68 | −4.40 | −6.20 |

| log (age)e | 9.15 | 8.83 | 9.27 | 9.26 ± 0.20 |

| [8.79,8.97] | [9.20,9.30] | |||

| SFH | Delayed-τ | Double-power law | Non-parametric | Delayed-τ |

| AV | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.57 ± 0.10 |

| [0.50,0.93] | [0.33,0.72] | |||

| χ2f | 2.1 | 15.8 | 22.4 | 11.3 |

aBest-fitting photo-z from eazy-py.bAveraged over 100 Myr. cIncluding the ALMA 2 mm data point. dWe note the limitation of the SFR from the SED which is likely to introduce an unrealistically low value of SFR and hence ΔMS especially for the parametric SFH models. The photometry (|$\mathcal {R}_s$|-band) and the best-fitting dust attenuation (AV) suggest the SFR of |$\sim 8\, {\rm M}_{\odot }$| yr−1 and log (ΔMS) ∼−1.6 (see also the main text in Section 4.1). eMass weighted.

fWe quote the absolute χ2 value, as the templates employed (as is the case for many SED fitting codes) are not independent of each other, and degrees of freedom are ill-defined (e.g. Smith et al. 2012).

3.3.1 BAGPIPES

We take into account two different types of parametric star formation histories (SFHs to fit the data points: double-power law SFH (SFR(t) ∝ [(t/τ)α + (t/τ)−β]−1) and non-parametric SFH. These two sets of SFH were chosen because an exponentially declining SFH (τ-model) model did not deliver a good fit for G4 using bagpipes giving high χ2 without reasonable convergence. Although the τ-model (e.g. Schmidt 1959; Conroy 2013) is the most popular model that has been extensively used in studies based on large surveys (e.g. Ilbert et al. 2013; Skelton et al. 2014; Stefanon et al. 2017) recent studies advocated the need for more complex or different models to explain the SFHs of galaxies (e.g. Maraston et al. 2010; Wuyts et al. 2011; Pacifici et al. 2016; Carnall et al. 2018; Leja et al. 2019a).

The double-power law SFH has more flexibility with an additional parameter (a total of 6 parameters) compared to a τ-model. We vary α and β values between 0.01 and 10000, with uniform priors in log space (‘log|$\_$|10’). The age of the Universe at the peak of star formation (τ) is sampled between 0.1 and 13.5 Gyr and the metallicity range is between 0 and 4.0 Z⊙. We adopt the reddening law of Calzetti et al. (2000) with the V-band attenuation (AV) between 0 and 4 magnitudes. Nebular emission is not taken into account for G4; we tested nebular emission with G4 and the nebular emission did not change our analysis. We allow the stellar mass formed by the assumed SFH in 7.0 < log (M⋆/M⊙) < 13.5.

We also test with non-parametric SFH with continuity prior using bagpipes to test if non-parametric SFH can produce better results. By its construction, the non-parametric continuity SFH priors can yield a better fit and may overfit because we have more free parameters to fit. To set the SFH bin, we follow the methodology described in Leja et al. (2019a) with six bins. The first two recent bins are set to 0–30, and 30–100 Myr, and the remaining four bins are equally spaced in logarithmic time. Leja et al. (2019a) showed that the number of bins in the mock analysis is insensitive as long as Nbins > 4. We also confirm that the number of bins has a negligible impact on stellar mass, age, and AV, and SFR for G4 for 4 < Nbins < 9. Therefore, we adopt the bin number Nbins = 6, which is computationally less expensive without excessively overfitting given the number of data points. For G4, we get the consistent stellar mass, and SFR, placing a galaxy far below the star-forming MS at z = 2, as summarized in Table 3.

3.3.2 FAST++

We run fast++ with the following assumptions: Bruzual & Charlot (2003) library (bc03) assuming Chabrier (Chabrier 2003) IMF. We assume a delayed-τ model for the sake of simplicity and to allow more flexibility than the τ model. The minimum e-folding time is set to log τmin = 8.0 (100 Myr) and maximum of log τmax = 10.1 (12.5 Gyr) in steps of log τ = 0.1 The minimum time since the onset of star formation is 50 Myr and the maximum is the age of the universe. The log (age) grid is made in steps of 0.05. Solar metallicity and the Calzetti dust attenuation law (Calzetti et al. 2000) are adopted with visual extinctions in the range of 0 < AV < 4.

3.3.3 CIGALE

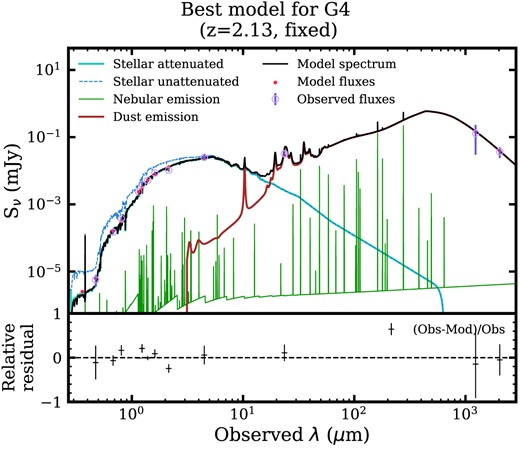

We use cigale (Boquien et al. 2019) in order to take into account the ALMA data points (2 and 1.2 mm) to avoid the potential underestimation of the SFR from optical to mid-IR photometry alone, especially for an obscured star-forming case. We adopt the delayed-τ model for the SFH. The other set-up is similar to those used in the other SED fitting process that we used Bruzual & Charlot (2003) library assuming Chabrier (Chabrier 2003) IMF and use the Calzetti dust attenuation law (Calzetti et al. 2000). As for the dust emission, we use the Draine et al. (2014) model constructed by varying the PAH mass fraction (qPAH = 1.12−3.90), minimum radiation field (Umin = 0.5−10), and power law slope (α = 1.0−2.0), which describes the distribution of the radiation field per mass. We also set the metallicity and nebular emission to vary. cigale fits G4’s SED well with reasonable χ2 ≈ 11.3 (Fig. 4).

4 RESULTS

4.1 Consistency in the SED fitting results and SFR from other methods

G4 is a massive galaxy with log (M⋆/M⊙) ≈ 11.0 based on the SED fitting. Best-fitting SED results of G4 are summarized in Table 3. The stellar masses between different codes are overall in good agreement. The agreement in the stellar mass between different models is consistent with earlier studies that stellar masses are the most robust parameter estimated from SED fitting for ‘normal’ (and not so blue) galaxies (e.g. Papovich, Dickinson & Ferguson 2001; Shapley et al. 2001; Conroy 2013; Pacifici et al. 2023).

All codes yield broadly consistent results favoring the quiescent nature of G4 though there are different levels of inactivity from the SED fitting. The multiple SED codes indicate that G4 is characterized as a quiescent galaxy with a low level of star-formation activity with log (sSFR/yr−1) ≲ −12.5, which is −3.5 dex lower than the star-forming MS at z = 2. The cigale fit, where we include the ALMA data points for the fitting with energy-balance assumption also gives a low level of star-formation and a quiescent solution for G4 with a reasonable χ2 value. The fitting results do not change with and without the 1.2 mm data point for G4. We show the best fit from cigale in Fig. 4 and the other best-fitting SED models in Appendix A.

However, the SFR from the SED could introduce artificially low SFR, especially for the parametric SFH models by its construction. In this regard, the attenuation corrected |$\mathcal {R}_s$|-band (i.e. rest-frame 2000 Å) magnitude suggests the SFR of |$\sim 8\, {\rm M}_{\odot }$| yr−1 and log (sSFR/yr−1) ∼-10.3 instead: we applied the implied extinction correction (AV ∼ 0.5) assuming the Calzetti law, i.e. A(2000 Å) ∼ 9 × E(B − V) ∼ 1.5 mag, which gives R ∼ 24.5 mag and converted this into SFR attributing the emission to UV continuum of young stars.

Given the different degrees of low SFR from the SED best fit and inferred SFR from the |$\mathcal {R}_s$|-band photometry, we estimate the SFR from three other different ways using 24 μm and 2 mm fluxes. These are more reliable tracers of SFR because they are not affected by dust obscuration. The estimated dust extinction (AV) is moderate, which can be attributed mainly to the old stellar population (≈0.4 in AV), but it is still good to check whether other different SFR measurements agree with each other. A summary of underlying estimates is presented in Table 4.

| Method . | 2 mm + MBBa . | Rest–8 μmb . | 24 μm scalingc . |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFR (M⊙ yr−1) | ∼2–136 | ∼30 (16–55) | ∼8–10 |

| Method . | 2 mm + MBBa . | Rest–8 μmb . | 24 μm scalingc . |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFR (M⊙ yr−1) | ∼2–136 | ∼30 (16–55) | ∼8–10 |

aAssuming β = 1.5−2.2, Td = 17–35 K for modified black body and using Kennicutt (1998) for LIR to SFR conversion. We note that the 1.2 mm data point gives a range of |$2-72\, {\rm M}_{\odot }$| yr−1, but the uncertainty is much larger if we take into account the photometry uncertainty.

bBased on Reddy et al. (2010) and the values in the parenthesis are taking the scatter of the relation between νLν and L(H α) (and SFR), not the 24 μm flux errors.

| Method . | 2 mm + MBBa . | Rest–8 μmb . | 24 μm scalingc . |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFR (M⊙ yr−1) | ∼2–136 | ∼30 (16–55) | ∼8–10 |

| Method . | 2 mm + MBBa . | Rest–8 μmb . | 24 μm scalingc . |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFR (M⊙ yr−1) | ∼2–136 | ∼30 (16–55) | ∼8–10 |

aAssuming β = 1.5−2.2, Td = 17–35 K for modified black body and using Kennicutt (1998) for LIR to SFR conversion. We note that the 1.2 mm data point gives a range of |$2-72\, {\rm M}_{\odot }$| yr−1, but the uncertainty is much larger if we take into account the photometry uncertainty.

bBased on Reddy et al. (2010) and the values in the parenthesis are taking the scatter of the relation between νLν and L(H α) (and SFR), not the 24 μm flux errors.

If we use the modified black body (MBB) and take the 2 mm flux, the obscured star formation can range |$\approx 2-136 \, {\rm M}_{\odot }$| yr−1 assuming Td = 17–35 K and β = 1.5–2.2, using Kennicutt (1998) to convert LIR to SFR and dividing it by 1.6 for Chabrier IMF (Madau & Dickinson 2014). Here, we assume no contribution from old stellar populations heating the dust. In general, however, there is a non-negligible contribution of the old stellar population in dust emission for quiescent galaxies, which could play another source of uncertainty constraining the SFR of G4 from LIR and in effect the SFR can be lower than this. Further, without constraining higher frequency near the dust SED peak and the dust temperature, there is considerable uncertainty in inferring the actual star-formation rate (Table 4). ALMA Band 4 covers the rest-frame 660μm at z ∼ 2, and should mainly trace the cold dust component rather than the SFR. Low S/N (≈1.5σ for total flux, Table 1) of the 1.2 mm data point does not provide a strong indication of extremely high star formation, giving a similar range of |$2-72\, {\rm M}_{\odot }$| yr−1. Future high-frequency observations at ALMA Band 9, and 10 tracing the dust peak will help to pin down the SFR.

Reddy et al. (2010) used the MIPS 24 μm flux for 〈z〉 ∼ 2 galaxies to constrain the relationship between the rest-frame 8 μm luminosity, which traces the emission from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and SFR. Using our 24 μm flux in Table 2 and equation (2) in Reddy et al. (2010), we get SFR of |$\sim 30 \, {\rm M}_{\odot }\, {\rm yr}^{-1}$| (total dust-corrected SFR). The scatter of this fit is about 0.24 dex, giving a range of 16–55 M⊙ yr−1 from the 24μm flux. However, the relationship between rest-frame 8μm and SFR is constructed based on galaxies forming stars at a higher rate, which might be a source of uncertainty playing a role in this conversion.

The third approach is to estimate SFR by scaling the 24μm flux with respect to Q2343-BX610, which has a better constraint with more photometric data points from UV-to-FIR, and use the latest SFR measurements of Q2343-BX610. Brisbin et al. (2019) measured the star-formation rate of BX610 to be 140 M⊙ yr−1 from their SED fitting including a few FIR data points. They estimated slightly higher than attenuation corrected SFR from UV-to-NIR (60 M⊙ yr−1) and H α (115 M⊙ yr−1) (Förster Schreiber et al. 2014, 2018). By taking the MIPS 24μm photometry for BX610 and G4, we estimate the G4’s SFR is ∼ 8–10 M⊙ yr−1.

SFR from different tracers can change by two orders of magnitude (or more; Schreiber et al. 2018; Belli, Newman & Ellis 2019; Man et al. 2021) between SFRSED, SFRIR + UV, and |$SFR_{\rm [OII]\, or\, H\beta }$| for high redshift quiescent galaxies. Based on multiple approaches to estimate the SFR, we suggest that the SFR of G4 from the scaling from the 24 μm point (the third method, SFR∼10 M⊙ yr−1) as the most reasonable (or robust) estimate with available data. Inferring SFR with only a single data point from 2 mm needs heavy interpolation and the conversion between rest-8 μm to SFR might have unknown systematics for low luminosity regime. This also minimizes our concern of potential underestimation of SFR from the SED fitting. This also agrees with the dust attenuation corrected SFR from the rest-frame UV magnitude. Finally, the adopted SFR of 10 M⊙ yr−1 also places the galaxy to be in (somewhat) better agreement with the observations and simulations in the age–ΔMS plane (Section 5.1).

With the SFR value of ∼10 M⊙ yr−1, G4 is a quiescent galaxy with lower sSFR (log (sSFR/yr−1) ≈ −10.2) at least by ≈1.2 dex from the z = 2 main-sequence, compared to main-sequence galaxies at z ∼ 2. We note that |$\log {({\rm sSFR}/{\rm yr}^{-1})} = -10.0\, (-10.5)$| at z ≈ 2 corresponds to the mass-doubling time being more than 3 (10) times the age of the universe at that redshift. One of the definitions of quiescent galaxies used in the literature is sSFR smaller than 0.3/tHubble (Franx et al. 2008), and G4 satisfies this. We use this sSFR (log (sSFR/yr−1) = −10.2) as a proxy of the galaxy’s quiescence.

We note that available data can not completely reject the possibility of a higher star-formation rate than currently best guessed. Future observations at higher frequencies at submm covering the dust SED peak are needed to highlight potential obscured star formation that we may still miss.

As for the other parameters, we take the bagpipes results using non-parametric SFH in the following discussions, because the results are close to the median values of four different SED fitting results. Also, the SFR of G4 from bagpipes non-parametric gives one of the highest star formation rates that we use as the upper limit constraint of the SFR (from the SED).

4.2 UVJ colour and stellar age

We investigate whether G4 also satisfies the selection criteria of quiescent galaxies using rest-frame U, V, J magnitudes, based on the best fit from bagpipes (non-parametric SFH). The U − V and V − J colours (hereafter UVJ colours) are widely used to distinguish quiescent galaxies from reddened dusty galaxies and star-forming galaxies as originally demonstrated by Labbé et al. (2005) and Wuyts et al. (2007); star-forming galaxies have bluer U − V colours than the other two classes, and dusty star-forming galaxies tend to have redder V − J colours than their quiescent counterpart. This idea has been further supported by simulations for z ∼ 2 galaxies (e.g. Donnari et al. 2019, but see Akins et al. 2022). The UVJ diagnostics become less reliable for z > 3 galaxies with decreasing purity both indicated by observations (e.g. Merlin et al. 2018; D’Eugenio et al. 2020; Forrest et al. 2020) and simulations (Lustig et al. 2021, 2023). Nevertheless, the UVJ colour selection works fairly well to select quiescent galaxies at z ∼ 2 observationally.

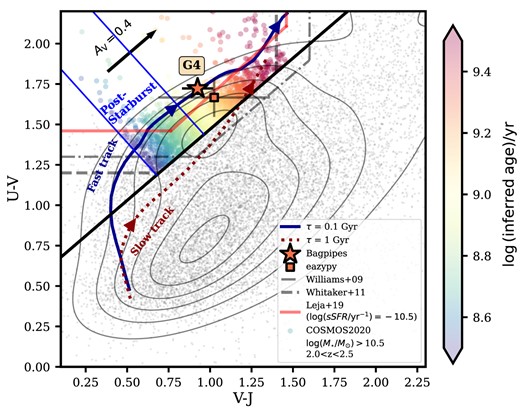

We adopt the UVJ colour selection of Whitaker et al. (2011) for 2 < z < 3.5 galaxies which are shown as a black diagonal line and a dashed line in Fig. 5. The diagonal black line separates the plane into two regions of quiescent and star-forming galaxies from their definition. Additional criteria of U − V > 1.2 and V − J < 1.4 (dashed line) distinguish unobscured and dusty star-forming galaxies, respectively. G4 is classified as a quiescent galaxy from these criteria. The UVJ colours based on eazy-py (filled square in Fig. 5) also show a good agreement. In Appendix A, we also list the best-fitting UVJ colours obtained from the best-fitting SED without fixing redshift. All but one SED best-fitting results give the rest-frame UVJ colours of the quiescent population. One exceptional case is in the bagpipes run with a flat redshift prior, using double-power law SFH, where the convergence was bad to reliably constrain the UVJ colours with large error bars (Table A1).

The rest-frame UVJ colours of G4 based on the bagpipes (non-parametric SFH) best-fit (star symbol), colour-coded by the mass-weighted age obtained from the SED fitting. The overlaying data points are log (M⋆/M⊙) > 10.5 galaxies at 2.0 < z < 2.5 in the COSMOS2020 catalogue (Weaver et al. 2022) and their number density distributions in contours. eazy-py best-fitting UVJ colours of G4 are shown as a square for a fair comparison with COSMOS2020. We define a quiescent region based on Whitaker et al. (2011). A thick solid diagonal line represents the definition by Whitaker et al. (2011) with additional cut in the U − V and V − J colours shown as a dashed line. COSOMOS2020 galaxies in the quiescent region are colour-coded with their expected stellar age based on the empirical age–colour relation derived by Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019) (for age >300 Myr). This shows a good match between age from the empirical relation and the one from the SED fitting for G4, giving a (mass-weighted) stellar age of 1−2 Gyr. A region corresponding to the stellar age between 300 and 800 Myr where most post-starburst galaxies would fall, is marked according to Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019). Two other different definitions of the quiescent region in the UVJ colour space are plotted: the dashed-dotted line is the definition suggested by Williams et al. (2009), and the red solid line represents the criteria by Leja, Tacchella & Conroy (2019b) for log (sSFR/yr−1) = −10.5. The dust attenuation direction and the amount are indicated as the arrow for AV = 0.4. We show two simple toy models of UVJ colour trajectory assuming the τ-model SFH, for different e-folding times, 100 Myr (dark blue solid, fast track) and 1 Gyr (dark red dotted, slow track) using fsps-py following Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019) (see Section 5.3 for details).

The UVJ colours of G4 also satisfy two other different quiescent galaxy criteria proposed by Williams et al. (2009) and Leja, Tacchella & Conroy (2019b). Williams et al. (2009) proposed a slightly different definition as a quiescence ridge line, U − V > 1.3, V − J < 1.6 and (U − V) > 0.88 × (V − J) + 0.49 for z ∼ 2 galaxies (a dashed-dotted line in Fig. 5). The solid red line in Fig. 5 is from Leja, Tacchella & Conroy (2019b) for log (sSFR/yr−1) = −10.5, in which the sample purity of quiescent galaxies is high enough (|$\gtrsim 92~{{\ \rm per\ cent}}$|) in the UVJ diagram using the 3D-HST galaxies. There is a tendency for galaxies with lower sSFR to be placed on the top left corners, more distantly perpendicular to the QG-SFG dividing line (thick solid black line in Fig. 5). However, the sSFR distribution saturates beyond this sSFR limit such that UVJ colours no longer give any further constraints.

Given that G4’s UVJ colours satisfy the quiescent criteria, we use this to infer the stellar age of the galaxy and compare it with the SED best fit. Calibrated with their deep spectroscopic observations, Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019) found a good correlation with the (median) stellar age (for >300 Myr) and the UVJ colours for 1.5 < z < 2.5 quiescent galaxies and the age distribution is along the diagonal quiescent ridge line. Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019) introduced a rotated coordinate system to calculate the age,

and the following median stellar age (t50) can be estimated by |$\log (t_{50}/\, {\rm yr})=7.03+1.12\cdot S_Q$|. This age-colour trend was also corroborated by (Carnall et al. 2020) based on the broad-band photometric data points for 2 < z < 5 quiescent galaxies.

The mass-weighted age from the SED matches well with the one from the empirical relation. The colour of G4’s symbol in Fig. 5 represents the mass-weighted age (∼1.9 Gyr) based on the SED fitting using bagpipes (non-parametric SFH), as listed in Table 3. The small grey dots in the background show log (M⋆/M⊙) > 10.5 galaxies at the redshift range of 2.0 < z < 2.5 from the COSMOS2020 catalogue (Weaver et al. 2022) by taking the rest-frame UVJ colours from their |${\small EAZY-PY}$| fit. The number density of them is also plotted as contours. For visual comparison, we colour-code the empirical age–colour relation proposed in Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019) using the COSMOS2020 galaxies within the quiescent region. The region marked in a blue box indicates the age range between 300 < age/Myr < 800, where post-starburst galaxies are expected to place according to Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019). Although we need spectroscopic confirmation to better constrain the stellar age, the SED-based mass-weighted ages (Table 3, ∼1−2 Gyr) and empirically derived age (≈1.2 Gyr) are broadly consistent within the errorbars.

Typical ages of quiescent galaxies with spectroscopic observations at z ∼ 2 are observed to be 1−2 Gyr, with a relatively large age spread (Kriek et al. 2006, 2009; Whitaker et al. 2013; van de Sande et al. 2013; Mendel et al. 2015; Onodera et al. 2015; Fumagalli et al. 2016; Belli, Newman & Ellis 2019; Estrada-Carpenter et al. 2020; Stockmann et al. 2020). This is also noticeable, although perhaps being much crude, by the inferred age and density distribution of COSMOS2020 galaxies in Fig. 5; the density peak of the ‘red cloud’ is at ∼1 Gyr but there are many galaxies younger and older than this. Considering the age distribution in the UVJ diagram, the estimated stellar age of the G4 (=1−2 Gyr) appears to be reasonable and common at z ∼ 2.

4.3 Dust-to-stellar mass ratio

We estimate the dust mass of G4 based on a single measurement at 2 mm, assuming a modified black body with

where β is the dust emissivity index, and κabs is the grain absorption cross section per unit mass, following the discussion in Bianchi (2013) and Berta et al. (2016). The lower dust temperature of a quiescent galaxy is indicated by Magdis et al. (2021), which performed the stacking analysis11 of the SED and obtained the best fit using Draine & Li (2007) templates. The adopted value of 23.5 K is the value for z ∼ 2 quiescent galaxies.12 The estimated dust mass of G4 is log (Md/M⊙) = 8.51 ± 0.24 where the error takes into account the photometric error only.

We note two caveats in our dust mass estimate: first, the inferred dust mass is a function of the assumed dust temperature, with higher Td corresponding to lower dust masses given an observed flux density. The dust-to-stellar mass ratio for G4, assuming Td = 23.5 K, is log(Md/M*) = −2.71 ± 0.26; if one instead assumes Td = 25 K, often adopted for normal star-forming galaxies (Scoville et al. 2016), the dust-to-stellar mass ratio reduces to log(Md/M*) = −2.75 – still at the high end of the range measured for quiescent galaxies (<−3); see also Fig. 6. Secondly, the modified black body assumption we have used is a conservative estimate of dust mass. It is known that it gives systematically lower values compared to estimates based on a fully sampled SED fitted with Draine & Li (2007) models. The current assumption of the β and the corresponding κ values mitigates this discrepancy (Bianchi 2013; Berta et al. 2016). The dust mass of G4 could become even higher if we adopt Draine & Li (2007) and once the SED is well sampled; if this is the case, it will strengthen the dust-rich nature of G4. As further support of our estimated dust mass, we note that the dust mass derived from cigale, where we assumed the Draine et al. (2014) model (an updated model from Draine & Li 2007), is log (Md/M⊙) = 8.62 ± 0.40, consistent with our measurement assuming the modified black-body.

Constraints on dust-to-stellar mass ratios as a function of redshift for z > 1 quiescent galaxies. G4 is indicated by a star symbol. Sources from the literature are indicated as circles if they are detected in dust emission; otherwise, inverted triangles indicate upper limits (3σ). ALMA.14 and ZF-COS-19589, two galaxies with high dust-to-stellar mass ratios comparable to G4, are also labelled. The colour of each source indicates the stellar mass of the galaxy. The stacking results by Magdis et al. (2021) for massive (log (M⋆/M⊙) > 10.8) quiescent galaxies at z ≲ 2 are shown as grey squares. Grey shaded region with a dotted curve is based on the functional form for the best fit at z < 1, μgas(= Mgas/M⋆) ∝ (1 + z)5, assuming a fixed gas-to-dust mass ratio of 92 and normalized at z = 1 with μgas = 8 per cent. For comparison to star-forming galaxies of similar mass, we calculated dust-to-stellar mass ratios using the scaling relation suggested by Tacconi et al. (2018), assuming a gas-to-dust mass ratio (GDR) of 100 for log (M⋆/M⊙) = 11.0 and 10.5 (red and blue shaded bands, respectively; more massive galaxies have smaller gas (and dust) at fixed GDR.

In Fig. 6, we show the dust-to-stellar mass ratio of G4 (log (Md/M⋆) = −2.71 ± 0.26) based on the above calculation and stellar mass from the SED fitting using bagpipes (non-parametric SFH). For comparison, we plot the stacking results of quiescent galaxies with 〈log (M⋆/M⊙)〉 ≈ 11.0 and 0 < z < 2 from Magdis et al. (2021) (grey shaded curve and square data points after factoring in ≈0.21 dex for converting Salpeter (Salpeter 1955) IMF to Chabrier IMF in stellar mass).

The Md/M⋆ value for G4 is comparable with those based on stacking analysis (Man et al. 2016; Gobat et al. 2018; Hayashi et al. 2018; Magdis et al. 2021; Blánquez-Sesé et al. 2023) and higher than most of the individual gravitationally lensed QGs (Caliendo et al. 2021; Whitaker et al. 2021) (Fig. 6). Whitaker et al. (2021) put an order of magnitude lower limit of dust-to-stellar mass ratio (<−4 dex) for non-detected sources, although one must be cautious interpreting non-detections for more spatially extended lensed sources (Gobat et al. 2022). Individual dust measurements and upper limits of non-lensed sources from Hayashi et al. (2018); Kalita et al. (2021); Suzuki et al. (2022) are also shown using the same modified blackbody model assumptions for β, κabs, and Td in equation (2). Most individual data points have dust-to-stellar mass ratios at least a factor of 3 lower than G4; the exceptions are ALMA.14 (z = 1.4; Hayashi et al. 2018) and ZF-COS-19589 (z = 3.7; Suzuki et al. 2022), which have inferred dust-to-stellar mass ratios comparable to or even higher than G4 (labelled in Fig. 6.)

ALMA.14 is located at the outer edge of the core region of a galaxy cluster at z = 1.4.13 It is detected in both CO (2−1) and [O ii] (narrow-band); while it has a low SFR ∼ 3 M⊙ yr−1 based on an SED fit to the optical/near-IR photometry (see Table B1), this estimate may significantly under-estimate the actual SFR, as we have discussed (Section 4.1). We recall that G4’s best-fitting SFR using the same SFH parametrization (τ model) and SED fitting code (fast++) suggested SFR∼0.01 M⊙ yr−1. Given the CO and [O ii] detections of ALMA.14, its status as a QG may be questionable.

ZF-COS-19589 has an inferred SFR comparable to our best estimate SFR of G4 (Section 4.1) based on a dust-corrected H β luminosity: |$10^{+28.5}_{-12.9}$| M⊙ yr−1; Schreiber et al. (2018). Its SFR inferred from an SED fit is |$0.00^{+4.41}_{-0.00}\,\, {\rm M}_{\odot }\, {\rm yr^{-1}}$|. Suzuki et al. (2021) estimated the SFRIR, extrapolated from a single continuum detection at an observed wavelength of 870 μm giving a range of 6−33 M⊙ yr−1 depending on the assumed dust temperatures (between 20 and 40 K). These inferences suggest that ZF-COS-19589 may have properties similar to G4, with M* smaller by ∼0.3−0.4 dex but with a comparable deviation (−1.2 dex) from the star-forming main sequence for its redshift.

In Fig. 6, we also plot the dust-to-stellar mass constraints of the star-forming main-sequence galaxies for different stellar mass bins of log (M⋆/M⊙) = 11.0 and 10.5. We used Tacconi et al. (2018) relation to get gas fraction and converted it to dust-to-stellar mass ratio assuming a fixed gas-to-dust mass ratio (GDR) of 100. The shaded region corresponds to ±0.3 dex scatter of the MS. The adopted GDR is reasonable for these two massive populations with high metallicity, e.g. Rémy-Ruyer et al. (2014). For a higher GDR, the shaded bands would go lower and vice versa.

If the Kennicutt–Schmidt relation is also applicable to this galaxy, we expect the gas-to-dust mass ratio of G4 should be higher than 100 to explain the observed dust-to-stellar mass ratio. A high gas-to-dust mass ratio for lensed (less massive) quiescent galaxies at z ∼ 2−3 was also advocated in Whitaker et al. (2021) based on simba simulation. To put it in a different way, the galaxy’s depletion time-scale is long (≳2.5 Gyr) at z ∼ 2 with the estimated SFR and observed dust at fixed gas-to-dust mass ratio. We will explore the dust-rich nature of the galaxy in the next section (Section 5.2).

Taking these all into account, G4 is highly dust-rich with a dust-to-stellar mass ratio of log (Md/M⋆) = −2.71 ± 0.26, compared to other high redshift quiescent galaxies reported in the literature, except for two and the stacked results. Considering its current star formation rate at a low level (log (sSFR/yr) ≲ −10.2), unless there is a process igniting star formation at later times, it is likely G4 will remain gas(dust)-rich while being ‘quenched’ for a long period of time (≳2.5 Gyr).

4.4 Morphology

The HST composite (Fig. 2) image shows that G4 has a central core-like component and an extended disc. Here, we quantify G4’s morphology by fitting the 2D light distribution with the Sérsic profile based on the F140W map for later discussion.

We use statmorph (Rodriguez-Gomez et al. 2019).14 and galfit (ver3.0; Peng et al. 2002, 2010). We fit the magnitude (m), half-light radius (re), Sérsic index (n), axis ratio (q), position angle (PA), and the central position. The initial guess parameters in the galfit are taken from the statmorph result. The fit gives n = 1.66 ± 0.03 (statmorph), where the error is estimated based on the bootstrapping after 1000 realization, and n = 1.66 ± 0.11 (galfit), respectively. The visual inspection of the residual images for both fits suggests the fit is reasonably good.

We also obtained Gini (Abraham, van den Bergh & Nair 2003) and M20 (Lotz, Primack & Madau 2004) non-parametric values from statmorph. They are 0.52 ± 0.01 and −1.85 ± 0.03, respectively. These values locate the galaxy close to the borderline between Sb/Sbc and E/S0/Sa classification based on Lotz et al. (2008).

5 A DUST-RICH QUIESCENT GALAXY IN DISTANT UNIVERSE

The available opt/NIR/MIR photometry and best-fitting UVJ colours (although these two are not independent measurements) suggest that G4 is a quiescent galaxy with low sSFR and mass-weighted age of ≈1−2 Gyr at z ≈ 2. Meanwhile, ALMA observations reveal that the galaxy has a high dust-to-stellar mass ratio, comparable to the stacked results which are (at least threefold) higher than most of the quiescent galaxies individually studied. In this section, we take advantage of these findings and compile available measurements in the literature to address the implication of G4’s properties in the context of quenching at high redshift.

5.1 Age–ΔMS relation: passive evolution at z > 1?

If galaxies evolve passively after the quenching, a negative correlation between the age and the distance from the MS is expected. With this idea, we first search for a signature of passive evolution at z ≳ 1 in the age–ΔMS relation. We gather the measurements of z ≳ 1 quiescent galaxies in the literature from Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019); Estrada-Carpenter et al. (2020) for z ∼ 1, Stockmann et al. (2020) for z ∼ 2, and Schreiber et al. (2018); D’Eugenio et al. (2020); Forrest et al. (2020); Valentino et al. (2020); Kubo et al. (2021) for z > 3 sources, all of which are plotted in Fig. 7.

![Age (mass-weighted) distribution as a function of the offset from the MS. G4 is plotted as star symbols, using different SFR estimates (24 μm flux scaling and SED); the fainter one is the best-fitting SED using bagpipes (non-parametric SFH) and see Section 4.1 for detailed discussions. We use the main-sequence definition from Speagle et al. (2014). Literature values are from Schreiber et al. (2018), Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019), D’Eugenio et al. (2020), Estrada-Carpenter et al. (2020), Stockmann et al. (2020), Valentino et al. (2020), and Kubo et al. (2021) for z ∼ 1−4 galaxies with constraints of the mass-weighted age, stellar mass, and star-formation rate. Here, we use SFR values from the SED fitting, except for two cases (ZF-COS-19589, D’Eugenio et al. 2020); for ZF-COS-19589, the 870 μm flux is used to calculate SFR(IR) assuming Td = 40 K taken from Suzuki et al. (2021). Eugenio et al. (2020) performed stacking analysis and we took the dust-corrected SFR from the (stacked) [O ii] line flux. The thick blue dashed line shows our best fit of age–ΔMS relation for z ∼ 1 quiescent galaxies using Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019) and Estrada-Carpenter et al. (2020) good-quality samples (see Section 5.1). High-z (z > 1) quiescent galaxies with dust/CO/[C i] observations are also plotted, taken from the various literature (see Section 5.2 and Table B1).](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/mnras/527/4/10.1093_mnras_stad3718/2/m_stad3718fig7.jpeg?Expires=1750181959&Signature=fuCd547GnD8iKms7Ig4XiXDzJ45btKjpXCB627Qe4hrcEid1kecxSzQGAyJziQFpc0lxZrvMg7ykP89K04uGtDbETVKR-Nn3v2SQY9EXCVe8s1Ihp6pdF4IUiwBxjdfznWFxHOX7rxSwDzXzgaJsRw0lOAoVfvXZc-sHrDY01yUcBOP2kbArgtvtuPwKrouGSjFZ1814uIJLfGoJ5anLKk4YD2pJMdqsNIIpj3fptpAOmpT8fSeXEJxBmn30IXOE4Ju2yirqvyAcJsaSh1iuPZaX7wRFe5jOz3Q7S0rmJ0HzaCsnHjXDSxa31sjhlKg8UcYMDG9n2MejLDmWUNe-qA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Age (mass-weighted) distribution as a function of the offset from the MS. G4 is plotted as star symbols, using different SFR estimates (24 μm flux scaling and SED); the fainter one is the best-fitting SED using bagpipes (non-parametric SFH) and see Section 4.1 for detailed discussions. We use the main-sequence definition from Speagle et al. (2014). Literature values are from Schreiber et al. (2018), Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019), D’Eugenio et al. (2020), Estrada-Carpenter et al. (2020), Stockmann et al. (2020), Valentino et al. (2020), and Kubo et al. (2021) for z ∼ 1−4 galaxies with constraints of the mass-weighted age, stellar mass, and star-formation rate. Here, we use SFR values from the SED fitting, except for two cases (ZF-COS-19589, D’Eugenio et al. 2020); for ZF-COS-19589, the 870 μm flux is used to calculate SFR(IR) assuming Td = 40 K taken from Suzuki et al. (2021). Eugenio et al. (2020) performed stacking analysis and we took the dust-corrected SFR from the (stacked) [O ii] line flux. The thick blue dashed line shows our best fit of age–ΔMS relation for z ∼ 1 quiescent galaxies using Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019) and Estrada-Carpenter et al. (2020) good-quality samples (see Section 5.1). High-z (z > 1) quiescent galaxies with dust/CO/[C i] observations are also plotted, taken from the various literature (see Section 5.2 and Table B1).

First, we investigate z ∼ 1 quiescent galaxies based on Estrada-Carpenter et al. (2020) and Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019) which provide 177 quiescent galaxies in total. The age (z50), stellar mass, and SFR measurements in these studies are estimated in a similar way, alleviating the systematic errors between the two. We choose a subset of good-quality data sets with the following criteria: galaxies having M⋆ errors within 0.2 dex with the stellar mass of log (M⋆/M⊙) > 10.5 and SFR errors within 0.6 dex. The adopted errors would sufficiently incorporate the potential systematic uncertainties in the different SED codes, as demonstrated by Pacifici et al. (2023). The final number used in the fitting is 147 in total. Galaxies with error bars in Fig. 7 show the subset and are used in the following fitting procedure.

With the following functional form, we perform the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo fitting using pymc (Salvatier, Wiecki & Fonnesbeck 2016), taking into account the errors:

We set the uniform prior around the best fit from the orthogonal distance regression (A = −0.26, B = −0.14) with dA = [1.5A, 0.5A], dB = [2B, −2B]. The best fit is A = −0.14 (confidence interval (CI) [3 per cent, 97 per cent] = [−0.19,−0.10]), B = 0.09 (CI = [−0.02,0.20]). The Spearman coefficient (with the good quality data) is −0.43 (thus negative) with p-value of 7e−8. Therefore, we confirm that the anticorrelation of mass-weighted stellar age and the deviation from the MS exists at z ∼ 1, indicating passive evolution. The best fit is shown as a dashed blue line in Fig. 7.

Compared to the situation at z ∼ 1, confirming the existence of age–ΔMS relation at z ≳ 2 is largely limited by the data. At z ∼ 2, Stockmann et al. (2020) provided mostly the upper limit constraints of SFR from the SED fitting. At least for those detected in 24 μm (table 2 in their paper), they are located close to G4 (i.e. log (sSFR) ≃ −10.2 and log (age) of ≃9.2). Higher redshift quiescent galaxies at z ≳ 3 (Schreiber et al. 2018; D’Eugenio et al. 2020; Forrest et al. 2020; Valentino et al. 2020; Kubo et al. 2021) are typically younger than G4 because the age of the universe gets younger. While there is a hint of negative correlation with lower normalization in z ∼ 3 quiescent galaxies from the visual inspection, substantiating the existence of the relation z ≳ 2 (as evidence of passive evolution) requires more observational data.

For completeness, in Fig. 7, we mark high-z quiescent galaxies with dust continuum and/or CO/[CI] line measurements by compiling all available information (M⋆, age, SFR, dust/CO/[C I]constraints) from the following papers: Onodera et al. (2012); Bezanson et al. (2013); Belli, Newman & Ellis (2015); Glazebrook et al. (2017); Hayashi et al. (2017); Rudnick et al. (2017); Suess et al. (2017); Hayashi et al. (2018); Newman et al. (2018a); Belli, Newman & Ellis (2019); Bezanson et al. (2019); Belli et al. (2021); Caliendo et al. (2021); Kalita et al. (2021); Whitaker et al. (2021); Williams et al. (2021); Gobat et al. (2022); Morishita et al. (2022); Suzuki et al. (2022); and Akhshik et al. (2023). We provide a summary in Table B1. Although it is tentative, it seems that many galaxies detected in dust and/or CO/[C I] are more scattered with respect to age–ΔMS relation. We investigate this more by connecting the dust-to-stellar mass ratio together with age and sSFR in Section 5.2.

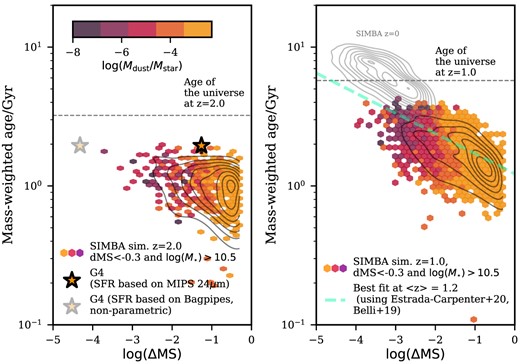

The anticorrelation at z ∼ 1 is also discernible in the cosmological simulation in simba simulations (Davé et al. 2019,15; Fig. 8), supporting our discovery based on the observational results. simba includes an on-the-fly dust production and destruction model (Li, Narayanan & Davé 2019) that no other large simulation boxes (|$\gtrsim (100\, h^{-1}$| Mpc)3 currently allow. The results are taken from the flagship run snapshots at three redshift bins (z = 2.0, 1.0, 0.0) with full simba physics in (100 h−1 Mpc)3 box using caesar.16 Fig. 8 shows the distribution of massive galaxies (log (M⋆/M⊙) > 10.5) below the main-sequence (log (ΔMS) < −0.3) on the age–log (ΔMS) plane.

Age–ΔMS relation in simba simulations at z = 2.0 (left) and z = 1.0 (right). Data points are for massive (log M⋆ > 10.5) quiescent galaxies (defined as log (ΔMS) < −0.3) colour-coded by the dust-to-stellar mass ratio. The distribution of z = 0 quiescent galaxies are also shown in grey contours on the right panel. We overlay G4’s position in star symbols for the z = 2.0 snapshot. The dashed line on the right panel is the best fit obtained from the observations of z ∼ 1 quiescent galaxies shown in Fig. 7.

Our best-fitting result of z ∼ 1 quiescent galaxies (dashed line) is shown in the z ∼ 1 snapshot (Fig. 8, right), which is comparable to the simulation result. The consistency in the observation and simulation at z = 1.0 and the evolution down to z = 0 (shown in grey contours) suggest that ΔMS–age relation is likely well established up to z ∼ 1 for quiescent galaxies.

The correlation at z = 2.0 is not clearly recognizable in the simulation (but a tail exists). Mendel et al. (2015), with their spectroscopic campaigns (VIRIAL survey), demonstrated that stellar ages of z ≲ 1 quiescent galaxies are reasonably explained by passive evolution while at z ≳ 2, galaxies’ pathways after the quenching (or while being quenched) and the evolution may not be simply a ‘passive’ evolution. The lack of age–ΔMS correlation at z ∼ 2 in the simulation perhaps corroborates the finding from the VIRIAL survey.

Meanwhile, simba simulations hardly find galaxies displaying similar properties of G4 for its given ΔMS and age and considering the associated uncertainties (see black contours in the left panel of Fig. 8). The distribution of G4 and available z ∼ 2 quiescent galaxies highly encourages more observations to check if there is any difference between the observation and simulation at z ≳ 2 and whether G4 is instead a rare population in the ΔMS–age relation. Finally, the SFR from 24 μm shows a better agreement with the distribution of simulated galaxies, providing indirect support for our choice of the SFR.

5.2 Long depletion time-scale

If galaxy quenching requires the removal/consumption of gas and dust, we can conjecture an additional correlation (that may not necessarily be linear) with the gas and dust content with the deviation from the MS (or sSFR) and age. Initial reduction/consumption of gas and dust (just after quenching) would have an imprint on the strength of the initial quenching mechanism, while the following evolution would give us a hint on additional mechanisms to remove/consume/supply gas and dust out of/to the galaxy.

Such a possibility is hinted at in the simba galaxies as shown in Fig. 8 where the colours represent the dust-to-stellar mass ratio at given ΔMS and age; we find a decrease of Md/M⋆ along the ‘passive evolutionary’ sequence identified in Section 5.1. Observations also found such a trend between Md/M⋆ and sSFR in the local galaxies (e.g. Cortese et al. 2012; De Vis et al. 2017). All these above lead us to connect the observed sSFR and age with the observed dust.

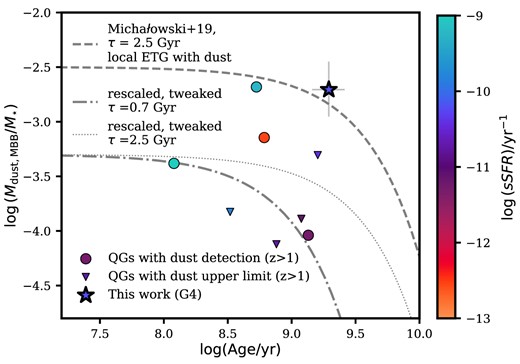

5.2.1 Dust depletion time-scale

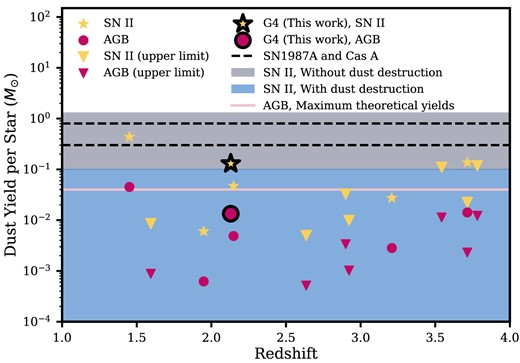

With the data set compiled in Table B1, we show the log (Md/M⋆) as a function of log (Age) in Fig. 9. Individual data points are from this work (G4), Gobat et al. (2022),17 Suzuki et al. (2022), and Kalita et al. (2021), giving nine sources in total. From this figure, the dust-richness of G4 at a given stellar age is a noticeable feature. It is also conceivable that there are two different subgroups in this plane: five out of nine galaxies display coherent decreasing sSFR with their age, while the remaining four do not with higher dust-to-stellar mass ratios including G4. In the following discussion, we call the former dust-poor quiescent galaxy and the latter dust-rich quiescent galaxy.

Dust-to-stellar mass ratio as a function of mass-weighted age. G4 is plotted as a star colour coded with its sSFR. We also plot other z > 1 quiescent galaxies with dust constraints from the literature (detection for circles, 3σ upper limit with upside-down triangles for non-detection; Kalita et al. 2021; Whitaker et al. 2021; Gobat et al. 2022; Suzuki et al. 2022). The three lines are inspired by Michałowski et al. (2019): dashed line is the fit based on the local Herschel selected early type galaxies, while the other two lines are tweaked and rescaled assuming τ = 0.7 Gyr (dash–dotted) and 2.5 Gyr (dotted) to guide our eye for dust-poor high-redshift quiescent galaxies. The colours represent the specific star formation rate of the galaxies.

We compare G4 with these high-redshift quiescent galaxies by taking the functional form (|$\frac{M_{\rm d}}{M_{\star }} = A \exp ({\rm -age/\tau })$|) described in Michałowski et al. (2019). Michałowski et al. (2019) used the Herschel-detected early type galaxies (ETG) in the local Universe (z < 0.1), and measured the e-folding time of τ = (2.5 ± 0.4) Gyr. This is shown as a dashed line in Fig. 9.