-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Labanya K Guha, Raghunathan Srianand, Patrick Petitjean, Host galaxies of ultra-strong Mg ii absorbers at z ∼ 0.7, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 527, Issue 3, January 2024, Pages 5075–5092, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stad3489

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

We report spectroscopic identification of the host galaxies of 18 ultra-strong Mg ii systems (USMg ii) at 0.6 ≤ z ≤ 0.8. We created the largest sample by merging these with 20 host galaxies from our previous survey within 0.4 ≤ z ≤ 0.6. Using this sample, we confirm that the measured impact parameters (|$\rm 6.3\leqslant D[kpc] \leqslant 120$| with a median of 19 kpc) are much larger than expected, and the USMg ii host galaxies do not follow the canonical |$\rm {\it W}_{2796}-{\it D}$| anticorrelation. We show that the presence and significance of this anticorrelation may depend on the sample selection. The |$\rm {\it W}_{2796}-{\it D}$| anticorrelation seen for the general Mg ii absorbers show a mild evolution at low |$\rm W_{2796}$| end over the redshift range 0.4 ≤ z ≤ 1.5 with an increase of the impact parameters. Compared to the host galaxies of normal Mg ii absorbers, USMg ii host galaxies are brighter and more massive for a given impact parameter. While the USMg ii systems preferentially pick star-forming galaxies, they exhibit slightly lower ongoing star-forming rates compared to main sequence galaxies with the same stellar mass, suggesting a transition from star-forming to quiescent states. For a limiting magnitude of mr < 23.6, at least 29 per cent of the USMg ii host galaxies are isolated, and the width of the Mg ii absorption in these cases may originate from gas flows (infall/outflow) in isolated haloes of massive star forming but not starbursting galaxies. We associate more than one galaxy with the absorber in |$\ge 21~{{\ \rm per\ cent}}$| cases, where interactions may cause wide velocity spread.

1 INTRODUCTION

The formation and evolution of galaxies is one of the most fundamental problems in extragalactic astronomy. Galaxies evolution is thought to be governed by the joint action of accretion of pristine metal-poor gas from the intergalactic medium (IGM), in situ star formation in the galactic disc, and feedback from star-formation-driven metal-rich galactic winds – a complex process known as the ‘cosmic baryon cycle’ (Anglés-Alcázar et al. 2017; Péroux & Howk 2020). The interplay between galactic winds and gas accretion from the IGM creates a metal-enriched gaseous halo surrounding galaxies out to a few virial radii known as the circumgalactic medium (CGM). The kinematically complex, multiphase CGM, which serves as an interface between the galactic disc (interstellar medium, ISM) and the IGM, controls the competition between IGM inflow and galactic feedback processes, which in turn controls how the galaxy evolves (Tumlinson, Peeples & Werk 2017; Faucher-Giguere & Oh 2023).

Due to the low density of most of the gas in the CGM (see e.g. Zahedy et al. 2019), it is difficult to capture the physical processes taking place in the CGM using the emission from this gas. Diffuse Ly α emission is frequently detected from high-z (i.e. z ≥ 2) galaxies which provide important information on the gas density and velocity field around galaxies (Wisotzki et al. 2018). However, such studies are rare for low-z, although there has been a steady attempt to map the CGM in Mg ii emission either directly (Chisholm et al. 2020; Burchett et al. 2021) or in the stacked images (see e.g. Dutta et al. 2023). As a result, absorption line spectroscopy remains the best means to understand the gas kinematics and physical processes that take place in the CGM. While the existence of large-scale gas flows (inflows/outflows) in the starforming galaxies is well established by the ‘down-the-barrel’ studies (Tremonti, Moustakas & Diamond-Stanic 2007; Rubin et al. 2010, 2014), the distance of the flowing gas from the galaxy (which is crucial for deriving wind parameters such as mass outflow rate) cannot be precisely determined with respect to the stellar discs. In contrast, the projected distance of the absorbing gas from the host galaxy is well measured in CGM studies using bright background sources like galaxies and quasars. However, drawing a clear connection between star formation and gas absorption is challenging, particularly at large impact parameters.

Historically, Mg ii doublet absorption seen in the spectra of quasars is used to trace the metal-enriched CGM around low-z galaxies (Bergeron & Boissé 1991). Probing the physical condition of the gas around galaxies using background quasar sight lines at very low impact parameters (e.g. within the regions influenced by winds over a characteristic time-scale of star formation) can provide vital clues on the role played by large-scale winds in shaping the physical conditions of the CGM and how it regulates galaxy evolution. For the past couple of years, we have been carrying out a systematic study of the CGM of z ∼ 0.7 galaxies at low impact parameters by (i) searching for the host galaxies of Ultra-Strong Mg ii absorbers (USMg ii) and (ii) studying the nature of Mg ii galaxies that happen to lie within very small impact parameters (i.e. Galaxies On Top of Quasars; GOTOQs) to background quasars (see Guha et al. 2022; Guha & Srianand 2023).

Here, we concentrate on USMg ii systems again. Following Nestor et al. (2007), we define the USMg ii systems as the ones having the rest equivalent width of the Mg ii|$\lambda \, 2796$| line (W2796) more than or equal to 3 Å. Given the canonical anticorrelation between |$\rm W_{2796}$| and the impact parameter (D) for the general population of Mg ii absorbers (Chen et al. 2010; Nielsen, Churchill & Kacprzak 2013), the impact parameters for the USMgii host galaxies are expected to be extremely low (≲10 kpc). The measured W2796 using low-dispersion spectra is well known to be linked to the number of absorbing clouds and the velocity dispersion between them, rather than the column density (Petitjean & Bergeron 1990). For a fully saturated Mg ii line a 3 Å limit on W2796 corresponds to a minimum velocity width of 320 km s−1. Such large velocity spreads could be caused by (i) galactic-scale outflows (Nestor et al. 2011a), (ii) filamentary accretion on to galaxies (Rubin et al. 2012), and (iii) galaxy mergers (Rubin et al. 2010) and intra-group gas (Gauthier 2013; Zou et al. 2018; Nielsen et al. 2022). In such instances, one could use the measured metallicities (Lehner et al. 2013) and galaxy orientations relative to quasar sightlines to differentiate between the various possibilities (Kacprzak, Churchill & Nielsen 2012). To measure metallicity, one requires high-resolution spectra covering H i and metal absorption lines. For accurately measuring the orientation of host galaxies, one needs high spatial-resolution images.

In a previous paper (Guha et al. 2022), we studied the nature and environment of a well-defined sample of USMgii host galaxies at z ∼ 0.5. We find that the impact parameters are larger than that predicted by the |$\rm {W_{2796}}$| versus the D relationship of the general population of Mg ii absorbers. The USMg ii host galaxies seem to form a distinct population in the |$\rm W_{2796}-D$| plane. USMg ii host galaxies are found to be massive and bright compared to those of the relatively weak Mg ii absorption systems for the same impact parameters. At least 33 per cent of the USMg ii host galaxies (with a limiting magnitude of mr < 23.6) are isolated, and the large |$\rm W_{2796}$| in these cases may originate from gas flows (infall/outflow) in a single halo of a massive but not a starbursting galaxy. We also find galaxy interactions could be responsible for large velocity widths in at least 17 per cent of the cases.

In the present study, we proceed further with a slightly higher redshift (z ∼ 0.7) sample to identify any redshift evolution associated with these systems. This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we discuss our USMg ii sample at z ∼ 0.7. Section 3 discusses the observations and data reduction procedures. In Section 4, we describe the data analysis and the results from this survey. The discussions and summary & conclusions are provided in Sections 5 and 6, respectively. Throughout this paper, we assume a flat Lambda cold dark matter cosmology with |$H_0 = 70\,{\rm km\, s^{-1}\, Mpc^{-1}}$| and Ωm,0 = 0.3.

2 THE USMG ii SAMPLE AT |$z\, \sim \, 0.7$|

In this work, we extend our study of USMg ii absorbers (Guha et al. 2022, which focused on USMg ii absorbers at 0.4 ≤ z ≤ 0.6) to slightly higher redshifts. For this, we compiled a sample of USMgii absorption system candidates from the twelfth data release (DR12) of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS; York et al. 2000; Alam et al. 2015) Fe ii/Mg ii absorbers catalogue (Zhu & Ménard 2013) that are accessible to the South African Large Telescope (SALT; Buckley et al. 2005) (i.e. with declination, δ ≤ 10°) in the redshift range 0.6 ≤ zabs ≤ 0.8. Our preliminary search resulted in a total of 151 USMg ii absorption system candidates along the line of sight towards 148 different background quasars. However, a careful visual inspection of the SDSS spectrum of each of these 151 USMg ii absorption systems revealed that a total of 88 are basically C iv/Si iv broad absorption lines (BAL) misidentified as USMg ii systems. Additional 36 systems are wrongly identified as USMg ii because of line blendings, poor SNR, or false identification of Mg ii absorption doublets, leaving behind only 27 secure USMg ii systems in the redshift range 0.6 ≤ z!abs < 0.8 with δ ≤ 10°. Details of all these 151 absorption systems are provided in the Appendix (Table A1 of Appendix A), where we explicitly mention whether the absorption system is a secure USMg ii absorption system or falsely identified as a USMg ii absorption system.

To confirm that the selected 27 USMg ii systems are indeed bona fide USMg ii absorption systems, we measure the rest equivalent widths of the Mg ii|$\lambda \lambda \, 2796,\, 2803$| absorption lines. For W2796, we first approximate the continuum around the Mg ii absorption lines with a smooth polynomial and then fit the absorption doublet using a pair of Gaussian profiles on top of this smooth polynomial. While fitting, we impose the redshift and velocity width of both the Gaussian profiles to be the same. This exercise confirms that within 1σ uncertainty all the selected 27 systems are indeed USMg ii absorption systems. Similarly, we fit the associated Fe ii λ 2600 and Mg i λ 2853 absorption lines each with a single Gaussian profile in addition to a smooth polynomial continuum, and compute their rest equivalent widths. Upon visual inspection of the fitted profiles for five of the USMg ii systems (J0127 − 0550, J0150 + 0604, J0256 + 0110, J0908 + 0727, J0956 + 0018), even in the low-resolution SDSS spectra, we identify sub-structures in the absorption profiles of Mg ii and Fe ii. Subsequently, these absorption profiles are not very well characterized by a single Gaussian profile with velocity offsets between absorption components ranging from 100 to 300 km s−1. The details of these 27 USMg ii systems along the emission redshifts, absorption redshifts, and the obtained rest equivalent widths are given in Table 1. In the case of non-detections, we provide the 3σ upper limit on the REW.

Details of our USMg ii sample. Columns (2), (3), and (4), respectively, provide the quasar name, emission redshift (zqso), and the absorption redshift (zabs). Columns (5)–(8) provide the REW of Mg ii λ 2796, Mg ii λ 2803, Fe ii λ 2600, Mg i λ 2803 lines, respectively.

| No. . | Quasar . | zqso . | zabs . | |$W_{2796}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2803}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2600}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2853}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . |

| 1 | J001030.81 + 012203.43 | 2.197 | 0.6433 | 3.19 ± 0.45 | 3.22 ± 0.46 | 2.01 ± 0.56 | <0.60 |

| 2 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | 2.749 | 0.7700 | 3.18 ± 0.28 | 3.03 ± 0.27 | 2.11 ± 0.37 | 0.87 ± 0.21 |

| 3 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | 2.493 | 0.6565 | 3.33 ± 0.19 | 3.29 ± 0.19 | 2.93 ± 0.19 | 1.21 ± 0.37 |

| 4 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | 2.658 | 0.7188 | 3.80 ± 0.30 | 3.11 ± 0.24 | 1.35 ± 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.13 |

| 5 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | 2.363 | 0.7150 | 4.02 ± 0.67 | 3.80 ± 0.63 | 2.90 ± 0.89 | 1.74 ± 0.59 |

| 6 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | 1.078 | 0.6489 | 3.41 ± 0.21 | 2.87 ± 0.18 | 1.69 ± 0.17 | <0.48 |

| 7 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | 2.137 | 0.6838 | 3.19 ± 0.51 | 2.54 ± 0.40 | 3.52 ± 0.75 | <0.54 |

| 8 | J014115.32 − 000500.98 | 2.130 | 0.6106 | 2.77 ± 0.38 | 2.02 ± 0.27 | 1.05 ± 0.28 | <0.42 |

| 9 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | 0.981 | 0.7858 | 3.90 ± 0.26 | 3.27 ± 0.22 | 2.43 ± 0.15 | 0.82 ± 0.17 |

| 10 | J015007.91 − 003937.09 | 2.730 | 0.7749 | 4.34 ± 0.53 | 4.08 ± 0.50 | 3.04 ± 0.26 | <0.57 |

| 11 | J015049.39 + 060432.42 | 2.676 | 0.6707 | 3.34 ± 0.22 | 2.69 ± 0.18 | 2.38 ± 0.28 | 0.77 ± 0.12 |

| 12 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | 1.3490 | 0.7255 | 3.29 ± 0.20 | 2.91 ± 0.18 | 2.29 ± 0.33 | 0.82 ± 0.12 |

| 13 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | 2.414 | 0.6123 | 5.30 ± 0.58 | 4.38 ± 0.48 | 4.24 ± 0.94 | 1.45 ± 0.30 |

| 14 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | 2.172 | 0.7820 | 6.34 ± 0.46 | 6.35 ± 0.46 | 5.43 ± 0.55 | 2.23 ± 0.51 |

| 15 | J103325.92 + 012836.35 | 2.180 | 0.6709 | 3.11 ± 0.17 | 2.82 ± 0.15 | 1.53 ± 0.15 | 0.44 ± 0.08 |

| 16 | J104642.70 + 045731.96 | 2.542 | 0.7849 | 4.47 ± 0.66 | 4.40 ± 0.65 | 2.19 ± 0.22 | <0.42 |

| 17 | J111627.65 + 050049.96 | 2.571 | 0.7208 | 3.78 ± 0.48 | 3.47 ± 0.44 | 1.93 ± 0.27 | <0.41 |

| 18 | J115026.11 + 090048.40 | 2.492 | 0.7568 | 3.39 ± 0.24 | 2.76 ± 0.19 | 1.66 ± 0.34 | 1.13 ± 0.11 |

| 19 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | 1.205 | 0.6842 | 4.55 ± 0.18 | 4.08 ± 0.16 | 2.30 ± 0.24 | 0.83 ± 0.11 |

| 20 | J121727.80 − 011548.57 | 2.624 | 0.6642 | 4.02 ± 0.45 | 3.64 ± 0.41 | 2.88 ± 0.28 | 1.57 ± 0.44 |

| 21 | J132200.79 − 010755.70 | 2.160 | 0.7226 | 3.24 ± 0.24 | 3.20 ± 0.24 | 3.05 ± 0.30 | 1.09 ± 0.14 |

| 22 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | 2.531 | 0.7059 | 3.06 ± 0.09 | 2.86 ± 0.08 | 2.03 ± 0.10 | 0.69 ± 0.08 |

| 23 | J140017.69 − 014902.40 | 2.555 | 0.7928 | 4.23 ± 0.25 | 4.02 ± 0.24 | 3.45 ± 0.25 | 1.04 ± 0.34 |

| 24 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | 2.316 | 0.7250 | 3.30 ± 0.40 | 2.80 ± 0.34 | 1.52 ± 0.22 | 1.50 ± 0.40 |

| 25 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | 0.772 | 0.6620 | 3.66 ± 0.26 | 2.99 ± 0.21 | 1.37 ± 0.13 | <0.54 |

| 26 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | 2.390 | 0.7407 | 3.29 ± 0.25 | 2.96 ± 0.23 | 1.94 ± 0.31 | <0.62 |

| 27 | J235639.31 − 040614.47 | 2.880 | 0.7707 | 3.77 ± 0.48 | 3.68 ± 0.47 | 1.81 ± 0.21 | <0.68 |

| No. . | Quasar . | zqso . | zabs . | |$W_{2796}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2803}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2600}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2853}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . |

| 1 | J001030.81 + 012203.43 | 2.197 | 0.6433 | 3.19 ± 0.45 | 3.22 ± 0.46 | 2.01 ± 0.56 | <0.60 |

| 2 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | 2.749 | 0.7700 | 3.18 ± 0.28 | 3.03 ± 0.27 | 2.11 ± 0.37 | 0.87 ± 0.21 |

| 3 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | 2.493 | 0.6565 | 3.33 ± 0.19 | 3.29 ± 0.19 | 2.93 ± 0.19 | 1.21 ± 0.37 |

| 4 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | 2.658 | 0.7188 | 3.80 ± 0.30 | 3.11 ± 0.24 | 1.35 ± 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.13 |

| 5 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | 2.363 | 0.7150 | 4.02 ± 0.67 | 3.80 ± 0.63 | 2.90 ± 0.89 | 1.74 ± 0.59 |

| 6 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | 1.078 | 0.6489 | 3.41 ± 0.21 | 2.87 ± 0.18 | 1.69 ± 0.17 | <0.48 |

| 7 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | 2.137 | 0.6838 | 3.19 ± 0.51 | 2.54 ± 0.40 | 3.52 ± 0.75 | <0.54 |

| 8 | J014115.32 − 000500.98 | 2.130 | 0.6106 | 2.77 ± 0.38 | 2.02 ± 0.27 | 1.05 ± 0.28 | <0.42 |

| 9 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | 0.981 | 0.7858 | 3.90 ± 0.26 | 3.27 ± 0.22 | 2.43 ± 0.15 | 0.82 ± 0.17 |

| 10 | J015007.91 − 003937.09 | 2.730 | 0.7749 | 4.34 ± 0.53 | 4.08 ± 0.50 | 3.04 ± 0.26 | <0.57 |

| 11 | J015049.39 + 060432.42 | 2.676 | 0.6707 | 3.34 ± 0.22 | 2.69 ± 0.18 | 2.38 ± 0.28 | 0.77 ± 0.12 |

| 12 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | 1.3490 | 0.7255 | 3.29 ± 0.20 | 2.91 ± 0.18 | 2.29 ± 0.33 | 0.82 ± 0.12 |

| 13 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | 2.414 | 0.6123 | 5.30 ± 0.58 | 4.38 ± 0.48 | 4.24 ± 0.94 | 1.45 ± 0.30 |

| 14 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | 2.172 | 0.7820 | 6.34 ± 0.46 | 6.35 ± 0.46 | 5.43 ± 0.55 | 2.23 ± 0.51 |

| 15 | J103325.92 + 012836.35 | 2.180 | 0.6709 | 3.11 ± 0.17 | 2.82 ± 0.15 | 1.53 ± 0.15 | 0.44 ± 0.08 |

| 16 | J104642.70 + 045731.96 | 2.542 | 0.7849 | 4.47 ± 0.66 | 4.40 ± 0.65 | 2.19 ± 0.22 | <0.42 |

| 17 | J111627.65 + 050049.96 | 2.571 | 0.7208 | 3.78 ± 0.48 | 3.47 ± 0.44 | 1.93 ± 0.27 | <0.41 |

| 18 | J115026.11 + 090048.40 | 2.492 | 0.7568 | 3.39 ± 0.24 | 2.76 ± 0.19 | 1.66 ± 0.34 | 1.13 ± 0.11 |

| 19 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | 1.205 | 0.6842 | 4.55 ± 0.18 | 4.08 ± 0.16 | 2.30 ± 0.24 | 0.83 ± 0.11 |

| 20 | J121727.80 − 011548.57 | 2.624 | 0.6642 | 4.02 ± 0.45 | 3.64 ± 0.41 | 2.88 ± 0.28 | 1.57 ± 0.44 |

| 21 | J132200.79 − 010755.70 | 2.160 | 0.7226 | 3.24 ± 0.24 | 3.20 ± 0.24 | 3.05 ± 0.30 | 1.09 ± 0.14 |

| 22 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | 2.531 | 0.7059 | 3.06 ± 0.09 | 2.86 ± 0.08 | 2.03 ± 0.10 | 0.69 ± 0.08 |

| 23 | J140017.69 − 014902.40 | 2.555 | 0.7928 | 4.23 ± 0.25 | 4.02 ± 0.24 | 3.45 ± 0.25 | 1.04 ± 0.34 |

| 24 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | 2.316 | 0.7250 | 3.30 ± 0.40 | 2.80 ± 0.34 | 1.52 ± 0.22 | 1.50 ± 0.40 |

| 25 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | 0.772 | 0.6620 | 3.66 ± 0.26 | 2.99 ± 0.21 | 1.37 ± 0.13 | <0.54 |

| 26 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | 2.390 | 0.7407 | 3.29 ± 0.25 | 2.96 ± 0.23 | 1.94 ± 0.31 | <0.62 |

| 27 | J235639.31 − 040614.47 | 2.880 | 0.7707 | 3.77 ± 0.48 | 3.68 ± 0.47 | 1.81 ± 0.21 | <0.68 |

Details of our USMg ii sample. Columns (2), (3), and (4), respectively, provide the quasar name, emission redshift (zqso), and the absorption redshift (zabs). Columns (5)–(8) provide the REW of Mg ii λ 2796, Mg ii λ 2803, Fe ii λ 2600, Mg i λ 2803 lines, respectively.

| No. . | Quasar . | zqso . | zabs . | |$W_{2796}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2803}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2600}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2853}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . |

| 1 | J001030.81 + 012203.43 | 2.197 | 0.6433 | 3.19 ± 0.45 | 3.22 ± 0.46 | 2.01 ± 0.56 | <0.60 |

| 2 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | 2.749 | 0.7700 | 3.18 ± 0.28 | 3.03 ± 0.27 | 2.11 ± 0.37 | 0.87 ± 0.21 |

| 3 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | 2.493 | 0.6565 | 3.33 ± 0.19 | 3.29 ± 0.19 | 2.93 ± 0.19 | 1.21 ± 0.37 |

| 4 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | 2.658 | 0.7188 | 3.80 ± 0.30 | 3.11 ± 0.24 | 1.35 ± 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.13 |

| 5 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | 2.363 | 0.7150 | 4.02 ± 0.67 | 3.80 ± 0.63 | 2.90 ± 0.89 | 1.74 ± 0.59 |

| 6 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | 1.078 | 0.6489 | 3.41 ± 0.21 | 2.87 ± 0.18 | 1.69 ± 0.17 | <0.48 |

| 7 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | 2.137 | 0.6838 | 3.19 ± 0.51 | 2.54 ± 0.40 | 3.52 ± 0.75 | <0.54 |

| 8 | J014115.32 − 000500.98 | 2.130 | 0.6106 | 2.77 ± 0.38 | 2.02 ± 0.27 | 1.05 ± 0.28 | <0.42 |

| 9 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | 0.981 | 0.7858 | 3.90 ± 0.26 | 3.27 ± 0.22 | 2.43 ± 0.15 | 0.82 ± 0.17 |

| 10 | J015007.91 − 003937.09 | 2.730 | 0.7749 | 4.34 ± 0.53 | 4.08 ± 0.50 | 3.04 ± 0.26 | <0.57 |

| 11 | J015049.39 + 060432.42 | 2.676 | 0.6707 | 3.34 ± 0.22 | 2.69 ± 0.18 | 2.38 ± 0.28 | 0.77 ± 0.12 |

| 12 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | 1.3490 | 0.7255 | 3.29 ± 0.20 | 2.91 ± 0.18 | 2.29 ± 0.33 | 0.82 ± 0.12 |

| 13 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | 2.414 | 0.6123 | 5.30 ± 0.58 | 4.38 ± 0.48 | 4.24 ± 0.94 | 1.45 ± 0.30 |

| 14 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | 2.172 | 0.7820 | 6.34 ± 0.46 | 6.35 ± 0.46 | 5.43 ± 0.55 | 2.23 ± 0.51 |

| 15 | J103325.92 + 012836.35 | 2.180 | 0.6709 | 3.11 ± 0.17 | 2.82 ± 0.15 | 1.53 ± 0.15 | 0.44 ± 0.08 |

| 16 | J104642.70 + 045731.96 | 2.542 | 0.7849 | 4.47 ± 0.66 | 4.40 ± 0.65 | 2.19 ± 0.22 | <0.42 |

| 17 | J111627.65 + 050049.96 | 2.571 | 0.7208 | 3.78 ± 0.48 | 3.47 ± 0.44 | 1.93 ± 0.27 | <0.41 |

| 18 | J115026.11 + 090048.40 | 2.492 | 0.7568 | 3.39 ± 0.24 | 2.76 ± 0.19 | 1.66 ± 0.34 | 1.13 ± 0.11 |

| 19 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | 1.205 | 0.6842 | 4.55 ± 0.18 | 4.08 ± 0.16 | 2.30 ± 0.24 | 0.83 ± 0.11 |

| 20 | J121727.80 − 011548.57 | 2.624 | 0.6642 | 4.02 ± 0.45 | 3.64 ± 0.41 | 2.88 ± 0.28 | 1.57 ± 0.44 |

| 21 | J132200.79 − 010755.70 | 2.160 | 0.7226 | 3.24 ± 0.24 | 3.20 ± 0.24 | 3.05 ± 0.30 | 1.09 ± 0.14 |

| 22 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | 2.531 | 0.7059 | 3.06 ± 0.09 | 2.86 ± 0.08 | 2.03 ± 0.10 | 0.69 ± 0.08 |

| 23 | J140017.69 − 014902.40 | 2.555 | 0.7928 | 4.23 ± 0.25 | 4.02 ± 0.24 | 3.45 ± 0.25 | 1.04 ± 0.34 |

| 24 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | 2.316 | 0.7250 | 3.30 ± 0.40 | 2.80 ± 0.34 | 1.52 ± 0.22 | 1.50 ± 0.40 |

| 25 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | 0.772 | 0.6620 | 3.66 ± 0.26 | 2.99 ± 0.21 | 1.37 ± 0.13 | <0.54 |

| 26 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | 2.390 | 0.7407 | 3.29 ± 0.25 | 2.96 ± 0.23 | 1.94 ± 0.31 | <0.62 |

| 27 | J235639.31 − 040614.47 | 2.880 | 0.7707 | 3.77 ± 0.48 | 3.68 ± 0.47 | 1.81 ± 0.21 | <0.68 |

| No. . | Quasar . | zqso . | zabs . | |$W_{2796}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2803}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2600}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . | |$W_{2853}\, ({\mathring{\rm A}})$| . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . |

| 1 | J001030.81 + 012203.43 | 2.197 | 0.6433 | 3.19 ± 0.45 | 3.22 ± 0.46 | 2.01 ± 0.56 | <0.60 |

| 2 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | 2.749 | 0.7700 | 3.18 ± 0.28 | 3.03 ± 0.27 | 2.11 ± 0.37 | 0.87 ± 0.21 |

| 3 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | 2.493 | 0.6565 | 3.33 ± 0.19 | 3.29 ± 0.19 | 2.93 ± 0.19 | 1.21 ± 0.37 |

| 4 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | 2.658 | 0.7188 | 3.80 ± 0.30 | 3.11 ± 0.24 | 1.35 ± 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.13 |

| 5 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | 2.363 | 0.7150 | 4.02 ± 0.67 | 3.80 ± 0.63 | 2.90 ± 0.89 | 1.74 ± 0.59 |

| 6 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | 1.078 | 0.6489 | 3.41 ± 0.21 | 2.87 ± 0.18 | 1.69 ± 0.17 | <0.48 |

| 7 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | 2.137 | 0.6838 | 3.19 ± 0.51 | 2.54 ± 0.40 | 3.52 ± 0.75 | <0.54 |

| 8 | J014115.32 − 000500.98 | 2.130 | 0.6106 | 2.77 ± 0.38 | 2.02 ± 0.27 | 1.05 ± 0.28 | <0.42 |

| 9 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | 0.981 | 0.7858 | 3.90 ± 0.26 | 3.27 ± 0.22 | 2.43 ± 0.15 | 0.82 ± 0.17 |

| 10 | J015007.91 − 003937.09 | 2.730 | 0.7749 | 4.34 ± 0.53 | 4.08 ± 0.50 | 3.04 ± 0.26 | <0.57 |

| 11 | J015049.39 + 060432.42 | 2.676 | 0.6707 | 3.34 ± 0.22 | 2.69 ± 0.18 | 2.38 ± 0.28 | 0.77 ± 0.12 |

| 12 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | 1.3490 | 0.7255 | 3.29 ± 0.20 | 2.91 ± 0.18 | 2.29 ± 0.33 | 0.82 ± 0.12 |

| 13 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | 2.414 | 0.6123 | 5.30 ± 0.58 | 4.38 ± 0.48 | 4.24 ± 0.94 | 1.45 ± 0.30 |

| 14 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | 2.172 | 0.7820 | 6.34 ± 0.46 | 6.35 ± 0.46 | 5.43 ± 0.55 | 2.23 ± 0.51 |

| 15 | J103325.92 + 012836.35 | 2.180 | 0.6709 | 3.11 ± 0.17 | 2.82 ± 0.15 | 1.53 ± 0.15 | 0.44 ± 0.08 |

| 16 | J104642.70 + 045731.96 | 2.542 | 0.7849 | 4.47 ± 0.66 | 4.40 ± 0.65 | 2.19 ± 0.22 | <0.42 |

| 17 | J111627.65 + 050049.96 | 2.571 | 0.7208 | 3.78 ± 0.48 | 3.47 ± 0.44 | 1.93 ± 0.27 | <0.41 |

| 18 | J115026.11 + 090048.40 | 2.492 | 0.7568 | 3.39 ± 0.24 | 2.76 ± 0.19 | 1.66 ± 0.34 | 1.13 ± 0.11 |

| 19 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | 1.205 | 0.6842 | 4.55 ± 0.18 | 4.08 ± 0.16 | 2.30 ± 0.24 | 0.83 ± 0.11 |

| 20 | J121727.80 − 011548.57 | 2.624 | 0.6642 | 4.02 ± 0.45 | 3.64 ± 0.41 | 2.88 ± 0.28 | 1.57 ± 0.44 |

| 21 | J132200.79 − 010755.70 | 2.160 | 0.7226 | 3.24 ± 0.24 | 3.20 ± 0.24 | 3.05 ± 0.30 | 1.09 ± 0.14 |

| 22 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | 2.531 | 0.7059 | 3.06 ± 0.09 | 2.86 ± 0.08 | 2.03 ± 0.10 | 0.69 ± 0.08 |

| 23 | J140017.69 − 014902.40 | 2.555 | 0.7928 | 4.23 ± 0.25 | 4.02 ± 0.24 | 3.45 ± 0.25 | 1.04 ± 0.34 |

| 24 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | 2.316 | 0.7250 | 3.30 ± 0.40 | 2.80 ± 0.34 | 1.52 ± 0.22 | 1.50 ± 0.40 |

| 25 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | 0.772 | 0.6620 | 3.66 ± 0.26 | 2.99 ± 0.21 | 1.37 ± 0.13 | <0.54 |

| 26 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | 2.390 | 0.7407 | 3.29 ± 0.25 | 2.96 ± 0.23 | 1.94 ± 0.31 | <0.62 |

| 27 | J235639.31 − 040614.47 | 2.880 | 0.7707 | 3.77 ± 0.48 | 3.68 ± 0.47 | 1.81 ± 0.21 | <0.68 |

Combining these findings for USMg ii systems at z = 0.6−0.8 with that of Guha et al. (2022) for USMg ii systems at z = 0.4−0.6, we can summarize that there are 260 USMg ii candidates at δ < 10 deg in the catalogue of Zhu & Ménard (2013) with 0.4 ≤ z ≤ 0.8 and out of which we confirm only 54 of them to be secured USMg ii absorbers.

3 SALT OBSERVATIONS AND DATA REDUCTION

To identify the galaxy or the galaxy group giving rise to the USMg ii absorption along the quasar line of sights, we first identify all the galaxies from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument Legacy Imaging Survey (DESI-LIS; Dey et al. 2019, typically complete upto mr ≤ 23.6) within a projected distance of 100 kpc (at the photometric redshifts). Details of these galaxies are given in Table A2 of Appendix B. To optimize our spectroscopic identification process using long-slit spectroscopy, we mainly focus on the galaxies with photometric redshifts consistent within 1σ uncertainty with that of the USMg ii systems and lying within 50 kpc from the quasar line-of-sight at the absorption redshift (as indicated by the dotted circles in Fig. 1). Next, we get the spectra of these candidate galaxies using the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT). In addition, whenever possible, we also observed potential galaxy candidates with impact parameters in the range 50−100 kpc.

The DECaLS r-band images of the quasar fields with the quasar placed at the centre and marked with a red ‘⋆’. The slit configuration used is indicated with a pair of red dashed lines. The spectroscopically identified USMg ii host galaxies are marked with a red ‘+’. The blue dashed circle in each panel corresponds to the circle of projected radius of 50 kpc at the absorption redshift.

The SALT spectroscopic observations were performed using the Robert Stobie Spectrograph (RSS; Burgh et al. 2003; Kobulnicky et al. 2003) in long-slit mode from June 2020 to February 2023 (Program IDs: 2020-1-SCI-010, 2020-2-SCI-019, 2021-1-SCI-006, 2021-2-SCI-012, 2022-1-SCI-016, 2022-2-SCI-015). The slit orientation [quantified through the position angle (PA) used] for each USMg ii system is suitably chosen such that all the candidate galaxies and quasars are observed simultaneously. For all our observations, we use the PG0900 grating along with a long slit-width of width 1.5 arcsec and the grating angles are so chosen that the expected nebular lines ([O ii], [O iii], and H β) from the USMg ii host galaxies fall within the wavelength coverage of the spectrograph avoiding the CCD gaps. The details of the observations are provided in Table 2. Column 2 provides the names of the quasars observed. The date of observations, total exposure time, the position angle (PA) from the north, the grating angle, and the wavelength range covered are provided in the next five subsequent columns in that order.

The observational log. Column 2 corresponds to the USMg ii systems observed. The observations date, total exposure, the slit position angle from the north, the grating angle, and the wavelength range are provided in columns 3–7, respectively.

| No. . | Quasar . | Date . | Exposure (s) . | PA (deg.) . | Grating . | Wavelength . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | Angle (deg) . | Range (Å) . |

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . |

| 1 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | 2021-07-11 | 2400 | 17 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-08-03 | 2400 | 17 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | 2020-07-29 | 2560 | 124 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 |

| 2020-09-15 | 2560 | 124 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 2022-08-04 | 2560 | 67 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 | ||

| 3 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | 2020-06-24 | 2560 | 29 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2020-07-24 | 2560 | 29 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2021-07-16 | 2560 | 155 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2021-08-06 | 2280 | 155 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 4 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | 2021-08-10 | 2400 | 171 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 5 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | 2020-07-29 | 2560 | 141 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 |

| 2020-10-13 | 2560 | 141 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 | ||

| 2022-08-27 | 2560 | 106 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 6 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | 2020-07-01 | 2560 | 41 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2020-10-14 | 2560 | 41 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 2022-08-20 | 2560 | 68 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 7 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | 2021-09-12 | 2200 | 86 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2021-08-04 | 2000 | 86 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 8 | J015007.91 − 003937.09 | 2022-09-21 | 2560 | 0 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 9 | J015049.39 + 060432.42 | 2020-10-16 | 2360 | 90 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 2022-07-17 | 2360 | 90 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 2022-09-23 | 2360 | 146 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 10 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | 2020-11-12 | 2580 | 133 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-08-09 | 2560 | 133 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2022-09-03 | 2560 | 95 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2021-08-10 | 2560 | 133 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 11 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | 2021-02-05 | 2300 | 73 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 2021-02-06 | 2300 | 73 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 12 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | 2021-02-08 | 2580 | 135 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-04-07 | 2580 | 135 | 20.375 | 6410–9120 | ||

| 13 | J103325.92 + 012836.35 | 2022-02-07 | 2440 | 21 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 14 | J104642.70 + 045731.96 | 2021-04-14 | 2200 | 161 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 15 | J111627.65 + 050049.96 | 2022-02-07 | 2300 | 87 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 16 | J115026.11 + 090048.40 | 2022-02-06 | 2200 | 41 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 17 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | 2021-01-21 | 2300 | 149 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2021-04-12 | 2300 | 149 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 18 | J121727.80 − 011548.57 | 2021-03-12 | 2580 | 139.25 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2023-01-23 | 2560 | 139 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 19 | J132200.79 − 010755.70 | 2023-02-23 | 2560 | 132 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2023-02-24 | 2560 | 132 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 20 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | 2022-04-30 | 2200 | 162 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2023-02-22 | 2560 | 163 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 21 | J140017.69 − 014902.40 | 2021-05-13 | 2560 | 0 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2021-06-13 | 2560 | 90 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 | ||

| 22 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | 2021-04-18 | 2300 | 142 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-05-17 | 2400 | 132 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2021-06-13 | 2400 | 67 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 23 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | 2020-06-16 | 2560 | 180 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 |

| 2020-06-24 | 2560 | 180 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 24 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | 2020-07-22 | 2560 | 31 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-05-11 | 2560 | 61 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 25 | J235639.31 − 040614.47 | 2017-06-05 | 2500 | 45 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2017-08-19 | 2350 | 315 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 | ||

| 2020-09-08 | 2560 | 90 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| No. . | Quasar . | Date . | Exposure (s) . | PA (deg.) . | Grating . | Wavelength . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | Angle (deg) . | Range (Å) . |

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . |

| 1 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | 2021-07-11 | 2400 | 17 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-08-03 | 2400 | 17 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | 2020-07-29 | 2560 | 124 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 |

| 2020-09-15 | 2560 | 124 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 2022-08-04 | 2560 | 67 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 | ||

| 3 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | 2020-06-24 | 2560 | 29 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2020-07-24 | 2560 | 29 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2021-07-16 | 2560 | 155 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2021-08-06 | 2280 | 155 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 4 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | 2021-08-10 | 2400 | 171 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 5 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | 2020-07-29 | 2560 | 141 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 |

| 2020-10-13 | 2560 | 141 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 | ||

| 2022-08-27 | 2560 | 106 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 6 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | 2020-07-01 | 2560 | 41 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2020-10-14 | 2560 | 41 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 2022-08-20 | 2560 | 68 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 7 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | 2021-09-12 | 2200 | 86 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2021-08-04 | 2000 | 86 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 8 | J015007.91 − 003937.09 | 2022-09-21 | 2560 | 0 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 9 | J015049.39 + 060432.42 | 2020-10-16 | 2360 | 90 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 2022-07-17 | 2360 | 90 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 2022-09-23 | 2360 | 146 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 10 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | 2020-11-12 | 2580 | 133 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-08-09 | 2560 | 133 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2022-09-03 | 2560 | 95 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2021-08-10 | 2560 | 133 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 11 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | 2021-02-05 | 2300 | 73 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 2021-02-06 | 2300 | 73 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 12 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | 2021-02-08 | 2580 | 135 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-04-07 | 2580 | 135 | 20.375 | 6410–9120 | ||

| 13 | J103325.92 + 012836.35 | 2022-02-07 | 2440 | 21 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 14 | J104642.70 + 045731.96 | 2021-04-14 | 2200 | 161 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 15 | J111627.65 + 050049.96 | 2022-02-07 | 2300 | 87 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 16 | J115026.11 + 090048.40 | 2022-02-06 | 2200 | 41 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 17 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | 2021-01-21 | 2300 | 149 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2021-04-12 | 2300 | 149 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 18 | J121727.80 − 011548.57 | 2021-03-12 | 2580 | 139.25 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2023-01-23 | 2560 | 139 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 19 | J132200.79 − 010755.70 | 2023-02-23 | 2560 | 132 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2023-02-24 | 2560 | 132 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 20 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | 2022-04-30 | 2200 | 162 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2023-02-22 | 2560 | 163 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 21 | J140017.69 − 014902.40 | 2021-05-13 | 2560 | 0 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2021-06-13 | 2560 | 90 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 | ||

| 22 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | 2021-04-18 | 2300 | 142 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-05-17 | 2400 | 132 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2021-06-13 | 2400 | 67 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 23 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | 2020-06-16 | 2560 | 180 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 |

| 2020-06-24 | 2560 | 180 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 24 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | 2020-07-22 | 2560 | 31 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-05-11 | 2560 | 61 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 25 | J235639.31 − 040614.47 | 2017-06-05 | 2500 | 45 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2017-08-19 | 2350 | 315 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 | ||

| 2020-09-08 | 2560 | 90 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

The observational log. Column 2 corresponds to the USMg ii systems observed. The observations date, total exposure, the slit position angle from the north, the grating angle, and the wavelength range are provided in columns 3–7, respectively.

| No. . | Quasar . | Date . | Exposure (s) . | PA (deg.) . | Grating . | Wavelength . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | Angle (deg) . | Range (Å) . |

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . |

| 1 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | 2021-07-11 | 2400 | 17 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-08-03 | 2400 | 17 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | 2020-07-29 | 2560 | 124 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 |

| 2020-09-15 | 2560 | 124 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 2022-08-04 | 2560 | 67 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 | ||

| 3 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | 2020-06-24 | 2560 | 29 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2020-07-24 | 2560 | 29 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2021-07-16 | 2560 | 155 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2021-08-06 | 2280 | 155 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 4 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | 2021-08-10 | 2400 | 171 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 5 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | 2020-07-29 | 2560 | 141 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 |

| 2020-10-13 | 2560 | 141 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 | ||

| 2022-08-27 | 2560 | 106 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 6 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | 2020-07-01 | 2560 | 41 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2020-10-14 | 2560 | 41 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 2022-08-20 | 2560 | 68 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 7 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | 2021-09-12 | 2200 | 86 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2021-08-04 | 2000 | 86 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 8 | J015007.91 − 003937.09 | 2022-09-21 | 2560 | 0 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 9 | J015049.39 + 060432.42 | 2020-10-16 | 2360 | 90 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 2022-07-17 | 2360 | 90 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 2022-09-23 | 2360 | 146 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 10 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | 2020-11-12 | 2580 | 133 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-08-09 | 2560 | 133 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2022-09-03 | 2560 | 95 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2021-08-10 | 2560 | 133 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 11 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | 2021-02-05 | 2300 | 73 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 2021-02-06 | 2300 | 73 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 12 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | 2021-02-08 | 2580 | 135 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-04-07 | 2580 | 135 | 20.375 | 6410–9120 | ||

| 13 | J103325.92 + 012836.35 | 2022-02-07 | 2440 | 21 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 14 | J104642.70 + 045731.96 | 2021-04-14 | 2200 | 161 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 15 | J111627.65 + 050049.96 | 2022-02-07 | 2300 | 87 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 16 | J115026.11 + 090048.40 | 2022-02-06 | 2200 | 41 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 17 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | 2021-01-21 | 2300 | 149 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2021-04-12 | 2300 | 149 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 18 | J121727.80 − 011548.57 | 2021-03-12 | 2580 | 139.25 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2023-01-23 | 2560 | 139 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 19 | J132200.79 − 010755.70 | 2023-02-23 | 2560 | 132 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2023-02-24 | 2560 | 132 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 20 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | 2022-04-30 | 2200 | 162 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2023-02-22 | 2560 | 163 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 21 | J140017.69 − 014902.40 | 2021-05-13 | 2560 | 0 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2021-06-13 | 2560 | 90 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 | ||

| 22 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | 2021-04-18 | 2300 | 142 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-05-17 | 2400 | 132 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2021-06-13 | 2400 | 67 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 23 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | 2020-06-16 | 2560 | 180 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 |

| 2020-06-24 | 2560 | 180 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 24 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | 2020-07-22 | 2560 | 31 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-05-11 | 2560 | 61 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 25 | J235639.31 − 040614.47 | 2017-06-05 | 2500 | 45 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2017-08-19 | 2350 | 315 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 | ||

| 2020-09-08 | 2560 | 90 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| No. . | Quasar . | Date . | Exposure (s) . | PA (deg.) . | Grating . | Wavelength . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | Angle (deg) . | Range (Å) . |

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . |

| 1 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | 2021-07-11 | 2400 | 17 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-08-03 | 2400 | 17 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | 2020-07-29 | 2560 | 124 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 |

| 2020-09-15 | 2560 | 124 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 2022-08-04 | 2560 | 67 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 | ||

| 3 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | 2020-06-24 | 2560 | 29 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2020-07-24 | 2560 | 29 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2021-07-16 | 2560 | 155 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2021-08-06 | 2280 | 155 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 4 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | 2021-08-10 | 2400 | 171 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 5 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | 2020-07-29 | 2560 | 141 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 |

| 2020-10-13 | 2560 | 141 | 18.125 | 5310–8320 | ||

| 2022-08-27 | 2560 | 106 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 6 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | 2020-07-01 | 2560 | 41 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2020-10-14 | 2560 | 41 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 2022-08-20 | 2560 | 68 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 7 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | 2021-09-12 | 2200 | 86 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2021-08-04 | 2000 | 86 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 8 | J015007.91 − 003937.09 | 2022-09-21 | 2560 | 0 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 9 | J015049.39 + 060432.42 | 2020-10-16 | 2360 | 90 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 2022-07-17 | 2360 | 90 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 2022-09-23 | 2360 | 146 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 10 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | 2020-11-12 | 2580 | 133 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-08-09 | 2560 | 133 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2022-09-03 | 2560 | 95 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 2021-08-10 | 2560 | 133 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 11 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | 2021-02-05 | 2300 | 73 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 2021-02-06 | 2300 | 73 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 | ||

| 12 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | 2021-02-08 | 2580 | 135 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-04-07 | 2580 | 135 | 20.375 | 6410–9120 | ||

| 13 | J103325.92 + 012836.35 | 2022-02-07 | 2440 | 21 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 |

| 14 | J104642.70 + 045731.96 | 2021-04-14 | 2200 | 161 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 15 | J111627.65 + 050049.96 | 2022-02-07 | 2300 | 87 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 16 | J115026.11 + 090048.40 | 2022-02-06 | 2200 | 41 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 17 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | 2021-01-21 | 2300 | 149 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2021-04-12 | 2300 | 149 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 18 | J121727.80 − 011548.57 | 2021-03-12 | 2580 | 139.25 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 |

| 2023-01-23 | 2560 | 139 | 19.25 | 5865–8865 | ||

| 19 | J132200.79 − 010755.70 | 2023-02-23 | 2560 | 132 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2023-02-24 | 2560 | 132 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 20 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | 2022-04-30 | 2200 | 162 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 |

| 2023-02-22 | 2560 | 163 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 21 | J140017.69 − 014902.40 | 2021-05-13 | 2560 | 0 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2021-06-13 | 2560 | 90 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 | ||

| 22 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | 2021-04-18 | 2300 | 142 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-05-17 | 2400 | 132 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 2021-06-13 | 2400 | 67 | 20 | 6000–8985 | ||

| 23 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | 2020-06-16 | 2560 | 180 | 18.5 | 5450–8450 |

| 2020-06-24 | 2560 | 180 | 18.875 | 5585–8585 | ||

| 24 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | 2020-07-22 | 2560 | 31 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

| 2021-05-11 | 2560 | 61 | 19.625 | 5870–8850 | ||

| 25 | J235639.31 − 040614.47 | 2017-06-05 | 2500 | 45 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 |

| 2017-08-19 | 2350 | 315 | 20.375 | 6140–9120 | ||

| 2020-09-08 | 2560 | 90 | 20 | 6000–8985 |

The raw CCD frames obtained from the observations are first processed with the SALT data reduction pipelines (Crawford et al. 2010). Next, we use standard pyraf (Science Software Branch at STScI 2012) routines to obtain the wavelength and flux-calibrated spectra of the quasars as well as the candidate galaxies. In summary, the science frames were first flat-field corrected, cosmic ray zapped, and then wavelength calibrated against a standard lamp spectrum. Next, we corrected the extinction due to the Earth’s atmosphere, and then the 1D spectra of the quasar and the galaxy were extracted. These 1D spectra were then flux-calibrated against standard stars observed with the same settings as the quasar. Finally, we apply the air to vacuum wavelength transformation and correct for the heliocentric velocity.

4 ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

4.1 Identification of the USMg ii host galaxies

Spectroscopic observations of host-galaxy candidates were completed using SALT for 25 of the 27 USMg ii systems (i.e. excluding the USMg ii absorbers along J0010+0122 and J0141−0005) in our sample. The r-band images of the fields together with the slit orientations (parallel dashed lines in red) used, and the 50 kpc impact parameter at the redshift of the absorber (indicated by the dashed circle) are shown in Fig. 1. The spectroscopically confirmed USMg ii host galaxies are marked with a red ‘+’, and the quasar locations are marked with a red ‘⋆’. As can be seen from this figure and Table A2 of the Appendix (in the online material), there are ten cases where we do not find any galaxy with r < 23.6 mag within an impact parameter of 50 kpc to the quasar sightline at the redshift of the USMg ii system. These are, J0142+0949, J0150−0039, J0150+0604, J1046+0457, J1116+0500, J1217−0115, J1322−0107, J1400−0149, J1451−0138, and J2356−0406. The USMgii absorber towards J2356−0406 is a known GOTOQ (Joshi et al. 2017), and we obtained RSS spectra along three position angles to find the location of the host galaxy using triangulation (see Fig. C1 of Appendix C). In the case of J1046+0457 and J1400−0149, we detect [O ii] emission at the correct redshift in the spectrum of the quasar. We thus confirm the USMg ii host galaxies to be GOTOQs at low impact parameters (i.e. D < 10 kpc). In the case of J1046+0457, we identify the location of the galaxy from the extension seen in the DECaLS images (as discussed in Guha & Srianand 2023) and in the case of J1400−0149, we used the spectra obtained along two PAs.

In five cases (J0142+0949, J0150−0039, J1116+0500, J1217−0115, and J1322−0107), however, we do have a candidate galaxy within 50 kpc if we slightly relax our candidate galaxy selection criteria. Here, we consider the galaxies having photo-z consistent within ∼2σ uncertainty and allow them to be fainter than the limiting magnitude of mr = 23.6. The impact parameter of the candidate galaxies ranges from D ∼ 10 to 50 kpc. In these cases, slit PA is chosen to simultaneously observe the quasar and the galaxy candidate. In the case of J0142+0949, the targeted galaxy at D ∼ 30 kpc (zph ∼ 0.9) does not show any detectable nebular emission line in its spectrum. Still, we find a pair of absorption features consistent with the Ca ii|$\lambda \lambda \, 3935, 3970$| doublet at zgal = 0.786 (see Fig. B1 of Appendix B) and thus consistent with the redshift zabs = 0.7858 of the USMg ii system. Therefore, we consider this galaxy as the host galaxy of the USMg ii absorber.

In the case of J1451−0138, we find a few galaxies with a projected distance of less than 50 kpc from the quasar. However, none has a photometric redshift consistent with the USMgii absorption redshift. We covered three galaxies in our observations (using two slit orientations) plus other galaxies outside the 50 kpc distance. We confirm only one galaxy with correct spectroscopic redshift but at an impact parameter of 64.1 kpc (|$\rm m_r = 21.59$|). In the remaining three cases we do not detect [O ii] emission from the galaxy candidates (typical 3σ limiting [O ii] line flux of |$7\times 10^{-18}\, \rm {ergs\, cm^{-2}\, s^{-1}}$|). In the case of J0150+0604, no faint candidate galaxies are found within 50 kpc. We do not have any indication of a faint galaxy coinciding with the quasar image (i.e. GOTOQs) either in the available photometry or in our spectroscopic data.

In summary, out of the ten USMg ii systems discussed above, we confirm three (J1046+0457, J1400−0149, and J2356−0406) of them to be GOTOQs. For J0142+0949 (even though the identified host galaxy has photo-z inconsistent within 1σ uncertainty) and J1451−0138 (impact parameter is larger than 50 kpc), we spectroscopically confirm the USMgii host galaxies. In four (J0150−0039, J1116+0500, and J1217−0115, and J1322−0107) cases, we have candidate galaxies (either faint or consistent photo-z within 2σ uncertainty) without spectroscopic confirmation. For J0150+0604, we do not have any candidate galaxy present within 50 kpc.

In nine cases (J0028+0041, J0033+0138, J0055−0100, J0127−0550, J0908+0727, J1150+0900, J1336+0922, J1419+0346, and J1449−0116), we have only one galaxy with r < 23.6 mag with a consistent photometric redshift within 50 kpc. We could get spectra of 8 candidate galaxies (apart from the case of J1150+0900 where our SALT observation was not scheduled) and confirm their redshifts using nebular emission lines to be consistent with the corresponding USMg ii system. Therefore, our target completeness is 89 per cent for observations, and spectroscopic completeness is 100 per cent for cases with only one candidate galaxy within 50 kpc of the USMgii absorbers.

In the remaining six cases, there are two galaxies within 50 kpc with consistent photometric redshifts. In three cases (J0105+0040, J0256+0110, and J1201+0713), we could get spectra of both galaxies. We confirm both (one of) the candidate galaxies to have consistent spectroscopic redshifts in the case of J1201+0713 (J0105+0040 and J0256+0110). In the case of J1033+0128, while we got the spectra of one of the candidates, we were unable to confirm the redshift using nebular emission lines. In the last two cases (J0020+0002 and J0956+0018), we could observe only one of the candidate galaxies (with the closest impact parameter) each and confirm them to have consistent spectroscopic redshifts. Therefore, the overall target completeness is 75 per cent for observations, and spectroscopic completeness is 67 per cent for cases with one candidate galaxy (brighter than 23.6 mag) within 50 kpc to the USMg ii absorbers.

Among the 25 observed USMg ii systems, we have successfully identified the USMg ii host galaxies for 18 cases (16 based on [O ii] emission and two based on Ca ii absorption). The quasars (that show USMg ii absorption systems) and the associated USMg ii host galaxies are indicated in columns 2 and 3 of Table 3, respectively. Columns 4 and 5, respectively, provide the spectroscopic redshifts (zgal) and the impact parameters (D). For four systems (J0020+0002, J0105+0040, J0127−0550, and J1201+0713), we could identify another galaxy within 100 kpc having spectroscopic redshift consistent with zabs of the USMg ii system. For the case of J0055−0100, we find an additional galaxy having consistent spectroscopic redshift with the USMg ii absorption at an impact parameter of 120 kpc. Details of these additional galaxies are also provided in Table 3. Therefore, we confirm that at least in 5 out of 18 cases, the USMg ii absorber could be associated with more than one galaxy having correct spectroscopic redshifts and impact parameters less than 125 kpc.

Properties of the USMg ii host galaxies. Columns 2 and 3, respectively, indicate the quasars and corresponding USMg ii host galaxies. Quasars marked with ‘⋆’ belong to the GOTOQs. Columns 4 and 5 provide the [O ii] emission redshifts and the impact parameters of the host galaxies. Columns 6 and 7 provide the stellar masses and the rest frame absolute B band magnitude of the USMg ii host galaxies, respectively. The [O ii] fluxes are measured in the units of 10−17 erg cm−2 s−1 and are provided in Column 8. Column 9 corresponds to the star formation rates based on SED fitting analysis. The values in the parenthesis correspond to the star formation rates based on the [O ii] emission line luminosity. The typical errors associated are about one-third of the value.

| No. . | Quasar . | Galaxy . | zgal . | D . | log (M⋆/M⊙) . | M!B . | [O ii] Flux . | SFR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | (kpc) . | . | . | . | (|$M_\odot \, yr^{-1}$|) . |

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . | (9) . |

| 1 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | J002022.65 + 000230.68 | 0.7684 | 9.7 | – | – | 0.92 ± 0.18 | – (1.2) |

| J002022.58 + 000227.38 | 0.7700 | 35.2 | |$9.33^{+0.31}_{-0.24}$| | −19.08 ± 0.11 | 0.71 ± 0.23 | |$1.04^{+0.88}_{-0.31}$| (1.0) | ||

| 2 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | J002839.05 + 004104.58 | 0.6565 | 22.2 | |$10.70^{+0.12}_{-0.13}$| | −20.27 ± 0.09 | 0.94 ± 0.27 | |$11.56^{+10.80}_{-4.78}$| (0.3) |

| 3 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | J003336.24 + 013844.75 | 0.7178 | 50.3 | |$11.76^{+0.04}_{-0.06}$| | −22.46 ± 0.07 | 1.88 ± 0.42 | |$56.90^{+11.65}_{-16.15}$| (2.0) |

| 4 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | J005554.28 − 010102.72 | 0.7150 | 29.8 | |$11.49^{+0.04}_{-0.05}$| | −21.19 ± 0.07 | <1.06 | |$4.72^{+5.31}_{-2.65}$| (<0.4) |

| J005554.42 − 010115.20 | 0.7161 | 120.7 | |$10.03^{+0.18}_{-0.17}$| | −20.01 ± 0.10 | 0.80 ± 0.19 | |$3.47^{+3.66}_{-2.00}$| (0.5) | ||

| 5 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | J010543.67 + 004001.10 | 0.6490 | 24.6 | |$10.35^{+0.11}_{-0.12}$| | −20.90 ± 0.09 | 11.2 ± 1.0 | |$5.57^{+2.93}_{-2.04}$| (3.2) |

| J010543.97 + 003957.28 | 0.6489 | 65.7 | |$9.54^{+0.14}_{-0.13}$| | −20.14 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.21 | |$3.04^{+2.19}_{-0.99}$| (0.5) | ||

| 6 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | J012711.20 − 055019.01 | 0.6829 | 16.8 | |$10.48^{+0.16}_{-0.17}$| | −21.35 ± 0.12 | 3.82 ± 0.87 | |$7.93^{+5.71}_{-2.96}$| (2.6) |

| J012711.91 − 055016.45 | 0.6839 | 90.1 | |$10.77^{+0.11}_{-0.18}$| | −20.90 ± 0.10 | 1.73 ± 0.23 | |$9.91_{-2.94}^{+4.44}$| (1.1) | ||

| 7 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | J014258.56 + 094942.20 | 0.7860 | 30.0 | |$12.01^{+0.12}_{-0.14}$| | −21.68 ± 0.09 | <1.10 | – (<0.4) |

| 8 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | J025607.10 + 011039.80 | 0.7244 | 18.4 | |$11.04^{+0.14}_{-0.12}$| | −21.26 ± 0.10 | 1.46 ± 0.28 | |$36.18^{+44.52}_{-16.68}$| (1.5) |

| 9 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | J090805.91 + 072740.58 | 0.6127 | 16.5 | |$10.73^{+0.13}_{-0.14}$| | −20.57 ± 0.10 | 2.53 ± 0.33 | |$15.61^{+12.78}_{-7.19}$| (1.3) |

| 10 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | J095619.41 + 001802.00 | 0.7829 | 15.6 | |$10.72^{+0.14}_{-0.16}$| | −21.06 ± 0.13 | 6.89 ± 0.52 | |$14.42^{+20.12}_{-7.00}$| (16) |

| 11 | J104642.70 + 045731.96⋆ | J104642.62 + 045731.84 | 0.7848 | 8.9 | – | – | 0.88 ± 0.27 | – (1.6) |

| 12 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | J120139.41 + 071342.84 | 0.6854 | 36.3 | |$10.98^{+0.14}_{-0.11}$| | −21.43 ± 0.10 | 1.80 ± 0.37 | |$42.97^{+45.06}_{-24.86}$| (1.2) |

| J120139.77 + 071333.28 | 0.6842 | 41.3 | |$11.42^{+0.13}_{-0.11}$| | −21.50 ± 0.09 | 2.91 ± 0.50 | |$82.69_{-24.86}^{+85.06}$| (1.7) | ||

| 13 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | J133653.80 + 092217.96 | 0.7059 | 24.6 | |$10.47^{+0.16}_{-0.20}$| | −20.47 ± 0.14 | 3.05 ± 0.30 | |$6.07^{+4.73}_{-2.10}$| (2.1) |

| 14 | J140017.69 − 014902.40⋆ | – | 0.7933 | ≤8 | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | J141930.39 + 034639.86 | 0.7252 | 42.8 | |$10.97^{+0.16}_{-0.17}$| | −21.51 ± 0.12 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | |$23.29^{+17.46}_{-9.22}$| (2.7) |

| 16 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | J144936.20 − 011643.58 | 0.6618 | 48.1 | |$10.74^{+.13}_{-0.08}$| | −21.05 ± 0.10 | 4.73 ± 0.43 | |$21.06^{+56.17}_{-10.87}$| (3.0) |

| 17 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | J145108.24 − 013840.64 | 0.7414 | 64.1 | |$11.44^{+0.07}_{-0.10}$| | −21.94 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.24 | |$34.44^{+9.42}_{-9.25}$| (3.5) |

| 18 | J235639.31 − 040614.47⋆ | J235639.27 − 040413.80 | 0.7699 | 6.24 | – | – | 5.49 ± 0.43 | – (3.9) |

| No. . | Quasar . | Galaxy . | zgal . | D . | log (M⋆/M⊙) . | M!B . | [O ii] Flux . | SFR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | (kpc) . | . | . | . | (|$M_\odot \, yr^{-1}$|) . |

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . | (9) . |

| 1 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | J002022.65 + 000230.68 | 0.7684 | 9.7 | – | – | 0.92 ± 0.18 | – (1.2) |

| J002022.58 + 000227.38 | 0.7700 | 35.2 | |$9.33^{+0.31}_{-0.24}$| | −19.08 ± 0.11 | 0.71 ± 0.23 | |$1.04^{+0.88}_{-0.31}$| (1.0) | ||

| 2 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | J002839.05 + 004104.58 | 0.6565 | 22.2 | |$10.70^{+0.12}_{-0.13}$| | −20.27 ± 0.09 | 0.94 ± 0.27 | |$11.56^{+10.80}_{-4.78}$| (0.3) |

| 3 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | J003336.24 + 013844.75 | 0.7178 | 50.3 | |$11.76^{+0.04}_{-0.06}$| | −22.46 ± 0.07 | 1.88 ± 0.42 | |$56.90^{+11.65}_{-16.15}$| (2.0) |

| 4 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | J005554.28 − 010102.72 | 0.7150 | 29.8 | |$11.49^{+0.04}_{-0.05}$| | −21.19 ± 0.07 | <1.06 | |$4.72^{+5.31}_{-2.65}$| (<0.4) |

| J005554.42 − 010115.20 | 0.7161 | 120.7 | |$10.03^{+0.18}_{-0.17}$| | −20.01 ± 0.10 | 0.80 ± 0.19 | |$3.47^{+3.66}_{-2.00}$| (0.5) | ||

| 5 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | J010543.67 + 004001.10 | 0.6490 | 24.6 | |$10.35^{+0.11}_{-0.12}$| | −20.90 ± 0.09 | 11.2 ± 1.0 | |$5.57^{+2.93}_{-2.04}$| (3.2) |

| J010543.97 + 003957.28 | 0.6489 | 65.7 | |$9.54^{+0.14}_{-0.13}$| | −20.14 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.21 | |$3.04^{+2.19}_{-0.99}$| (0.5) | ||

| 6 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | J012711.20 − 055019.01 | 0.6829 | 16.8 | |$10.48^{+0.16}_{-0.17}$| | −21.35 ± 0.12 | 3.82 ± 0.87 | |$7.93^{+5.71}_{-2.96}$| (2.6) |

| J012711.91 − 055016.45 | 0.6839 | 90.1 | |$10.77^{+0.11}_{-0.18}$| | −20.90 ± 0.10 | 1.73 ± 0.23 | |$9.91_{-2.94}^{+4.44}$| (1.1) | ||

| 7 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | J014258.56 + 094942.20 | 0.7860 | 30.0 | |$12.01^{+0.12}_{-0.14}$| | −21.68 ± 0.09 | <1.10 | – (<0.4) |

| 8 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | J025607.10 + 011039.80 | 0.7244 | 18.4 | |$11.04^{+0.14}_{-0.12}$| | −21.26 ± 0.10 | 1.46 ± 0.28 | |$36.18^{+44.52}_{-16.68}$| (1.5) |

| 9 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | J090805.91 + 072740.58 | 0.6127 | 16.5 | |$10.73^{+0.13}_{-0.14}$| | −20.57 ± 0.10 | 2.53 ± 0.33 | |$15.61^{+12.78}_{-7.19}$| (1.3) |

| 10 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | J095619.41 + 001802.00 | 0.7829 | 15.6 | |$10.72^{+0.14}_{-0.16}$| | −21.06 ± 0.13 | 6.89 ± 0.52 | |$14.42^{+20.12}_{-7.00}$| (16) |

| 11 | J104642.70 + 045731.96⋆ | J104642.62 + 045731.84 | 0.7848 | 8.9 | – | – | 0.88 ± 0.27 | – (1.6) |

| 12 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | J120139.41 + 071342.84 | 0.6854 | 36.3 | |$10.98^{+0.14}_{-0.11}$| | −21.43 ± 0.10 | 1.80 ± 0.37 | |$42.97^{+45.06}_{-24.86}$| (1.2) |

| J120139.77 + 071333.28 | 0.6842 | 41.3 | |$11.42^{+0.13}_{-0.11}$| | −21.50 ± 0.09 | 2.91 ± 0.50 | |$82.69_{-24.86}^{+85.06}$| (1.7) | ||

| 13 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | J133653.80 + 092217.96 | 0.7059 | 24.6 | |$10.47^{+0.16}_{-0.20}$| | −20.47 ± 0.14 | 3.05 ± 0.30 | |$6.07^{+4.73}_{-2.10}$| (2.1) |

| 14 | J140017.69 − 014902.40⋆ | – | 0.7933 | ≤8 | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | J141930.39 + 034639.86 | 0.7252 | 42.8 | |$10.97^{+0.16}_{-0.17}$| | −21.51 ± 0.12 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | |$23.29^{+17.46}_{-9.22}$| (2.7) |

| 16 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | J144936.20 − 011643.58 | 0.6618 | 48.1 | |$10.74^{+.13}_{-0.08}$| | −21.05 ± 0.10 | 4.73 ± 0.43 | |$21.06^{+56.17}_{-10.87}$| (3.0) |

| 17 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | J145108.24 − 013840.64 | 0.7414 | 64.1 | |$11.44^{+0.07}_{-0.10}$| | −21.94 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.24 | |$34.44^{+9.42}_{-9.25}$| (3.5) |

| 18 | J235639.31 − 040614.47⋆ | J235639.27 − 040413.80 | 0.7699 | 6.24 | – | – | 5.49 ± 0.43 | – (3.9) |

Properties of the USMg ii host galaxies. Columns 2 and 3, respectively, indicate the quasars and corresponding USMg ii host galaxies. Quasars marked with ‘⋆’ belong to the GOTOQs. Columns 4 and 5 provide the [O ii] emission redshifts and the impact parameters of the host galaxies. Columns 6 and 7 provide the stellar masses and the rest frame absolute B band magnitude of the USMg ii host galaxies, respectively. The [O ii] fluxes are measured in the units of 10−17 erg cm−2 s−1 and are provided in Column 8. Column 9 corresponds to the star formation rates based on SED fitting analysis. The values in the parenthesis correspond to the star formation rates based on the [O ii] emission line luminosity. The typical errors associated are about one-third of the value.

| No. . | Quasar . | Galaxy . | zgal . | D . | log (M⋆/M⊙) . | M!B . | [O ii] Flux . | SFR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | (kpc) . | . | . | . | (|$M_\odot \, yr^{-1}$|) . |

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . | (9) . |

| 1 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | J002022.65 + 000230.68 | 0.7684 | 9.7 | – | – | 0.92 ± 0.18 | – (1.2) |

| J002022.58 + 000227.38 | 0.7700 | 35.2 | |$9.33^{+0.31}_{-0.24}$| | −19.08 ± 0.11 | 0.71 ± 0.23 | |$1.04^{+0.88}_{-0.31}$| (1.0) | ||

| 2 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | J002839.05 + 004104.58 | 0.6565 | 22.2 | |$10.70^{+0.12}_{-0.13}$| | −20.27 ± 0.09 | 0.94 ± 0.27 | |$11.56^{+10.80}_{-4.78}$| (0.3) |

| 3 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | J003336.24 + 013844.75 | 0.7178 | 50.3 | |$11.76^{+0.04}_{-0.06}$| | −22.46 ± 0.07 | 1.88 ± 0.42 | |$56.90^{+11.65}_{-16.15}$| (2.0) |

| 4 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | J005554.28 − 010102.72 | 0.7150 | 29.8 | |$11.49^{+0.04}_{-0.05}$| | −21.19 ± 0.07 | <1.06 | |$4.72^{+5.31}_{-2.65}$| (<0.4) |

| J005554.42 − 010115.20 | 0.7161 | 120.7 | |$10.03^{+0.18}_{-0.17}$| | −20.01 ± 0.10 | 0.80 ± 0.19 | |$3.47^{+3.66}_{-2.00}$| (0.5) | ||

| 5 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | J010543.67 + 004001.10 | 0.6490 | 24.6 | |$10.35^{+0.11}_{-0.12}$| | −20.90 ± 0.09 | 11.2 ± 1.0 | |$5.57^{+2.93}_{-2.04}$| (3.2) |

| J010543.97 + 003957.28 | 0.6489 | 65.7 | |$9.54^{+0.14}_{-0.13}$| | −20.14 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.21 | |$3.04^{+2.19}_{-0.99}$| (0.5) | ||

| 6 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | J012711.20 − 055019.01 | 0.6829 | 16.8 | |$10.48^{+0.16}_{-0.17}$| | −21.35 ± 0.12 | 3.82 ± 0.87 | |$7.93^{+5.71}_{-2.96}$| (2.6) |

| J012711.91 − 055016.45 | 0.6839 | 90.1 | |$10.77^{+0.11}_{-0.18}$| | −20.90 ± 0.10 | 1.73 ± 0.23 | |$9.91_{-2.94}^{+4.44}$| (1.1) | ||

| 7 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | J014258.56 + 094942.20 | 0.7860 | 30.0 | |$12.01^{+0.12}_{-0.14}$| | −21.68 ± 0.09 | <1.10 | – (<0.4) |

| 8 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | J025607.10 + 011039.80 | 0.7244 | 18.4 | |$11.04^{+0.14}_{-0.12}$| | −21.26 ± 0.10 | 1.46 ± 0.28 | |$36.18^{+44.52}_{-16.68}$| (1.5) |

| 9 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | J090805.91 + 072740.58 | 0.6127 | 16.5 | |$10.73^{+0.13}_{-0.14}$| | −20.57 ± 0.10 | 2.53 ± 0.33 | |$15.61^{+12.78}_{-7.19}$| (1.3) |

| 10 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | J095619.41 + 001802.00 | 0.7829 | 15.6 | |$10.72^{+0.14}_{-0.16}$| | −21.06 ± 0.13 | 6.89 ± 0.52 | |$14.42^{+20.12}_{-7.00}$| (16) |

| 11 | J104642.70 + 045731.96⋆ | J104642.62 + 045731.84 | 0.7848 | 8.9 | – | – | 0.88 ± 0.27 | – (1.6) |

| 12 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | J120139.41 + 071342.84 | 0.6854 | 36.3 | |$10.98^{+0.14}_{-0.11}$| | −21.43 ± 0.10 | 1.80 ± 0.37 | |$42.97^{+45.06}_{-24.86}$| (1.2) |

| J120139.77 + 071333.28 | 0.6842 | 41.3 | |$11.42^{+0.13}_{-0.11}$| | −21.50 ± 0.09 | 2.91 ± 0.50 | |$82.69_{-24.86}^{+85.06}$| (1.7) | ||

| 13 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | J133653.80 + 092217.96 | 0.7059 | 24.6 | |$10.47^{+0.16}_{-0.20}$| | −20.47 ± 0.14 | 3.05 ± 0.30 | |$6.07^{+4.73}_{-2.10}$| (2.1) |

| 14 | J140017.69 − 014902.40⋆ | – | 0.7933 | ≤8 | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | J141930.39 + 034639.86 | 0.7252 | 42.8 | |$10.97^{+0.16}_{-0.17}$| | −21.51 ± 0.12 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | |$23.29^{+17.46}_{-9.22}$| (2.7) |

| 16 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | J144936.20 − 011643.58 | 0.6618 | 48.1 | |$10.74^{+.13}_{-0.08}$| | −21.05 ± 0.10 | 4.73 ± 0.43 | |$21.06^{+56.17}_{-10.87}$| (3.0) |

| 17 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | J145108.24 − 013840.64 | 0.7414 | 64.1 | |$11.44^{+0.07}_{-0.10}$| | −21.94 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.24 | |$34.44^{+9.42}_{-9.25}$| (3.5) |

| 18 | J235639.31 − 040614.47⋆ | J235639.27 − 040413.80 | 0.7699 | 6.24 | – | – | 5.49 ± 0.43 | – (3.9) |

| No. . | Quasar . | Galaxy . | zgal . | D . | log (M⋆/M⊙) . | M!B . | [O ii] Flux . | SFR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | (kpc) . | . | . | . | (|$M_\odot \, yr^{-1}$|) . |

| (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . | (7) . | (8) . | (9) . |

| 1 | J002022.66 + 000231.98 | J002022.65 + 000230.68 | 0.7684 | 9.7 | – | – | 0.92 ± 0.18 | – (1.2) |

| J002022.58 + 000227.38 | 0.7700 | 35.2 | |$9.33^{+0.31}_{-0.24}$| | −19.08 ± 0.11 | 0.71 ± 0.23 | |$1.04^{+0.88}_{-0.31}$| (1.0) | ||

| 2 | J002839.24 + 004103.05 | J002839.05 + 004104.58 | 0.6565 | 22.2 | |$10.70^{+0.12}_{-0.13}$| | −20.27 ± 0.09 | 0.94 ± 0.27 | |$11.56^{+10.80}_{-4.78}$| (0.3) |

| 3 | J003336.04 + 013851.06 | J003336.24 + 013844.75 | 0.7178 | 50.3 | |$11.76^{+0.04}_{-0.06}$| | −22.46 ± 0.07 | 1.88 ± 0.42 | |$56.90^{+11.65}_{-16.15}$| (2.0) |

| 4 | J005554.25 − 010058.62 | J005554.28 − 010102.72 | 0.7150 | 29.8 | |$11.49^{+0.04}_{-0.05}$| | −21.19 ± 0.07 | <1.06 | |$4.72^{+5.31}_{-2.65}$| (<0.4) |

| J005554.42 − 010115.20 | 0.7161 | 120.7 | |$10.03^{+0.18}_{-0.17}$| | −20.01 ± 0.10 | 0.80 ± 0.19 | |$3.47^{+3.66}_{-2.00}$| (0.5) | ||

| 5 | J010543.52 + 004003.86 | J010543.67 + 004001.10 | 0.6490 | 24.6 | |$10.35^{+0.11}_{-0.12}$| | −20.90 ± 0.09 | 11.2 ± 1.0 | |$5.57^{+2.93}_{-2.04}$| (3.2) |

| J010543.97 + 003957.28 | 0.6489 | 65.7 | |$9.54^{+0.14}_{-0.13}$| | −20.14 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.21 | |$3.04^{+2.19}_{-0.99}$| (0.5) | ||

| 6 | J012711.11 − 055020.95 | J012711.20 − 055019.01 | 0.6829 | 16.8 | |$10.48^{+0.16}_{-0.17}$| | −21.35 ± 0.12 | 3.82 ± 0.87 | |$7.93^{+5.71}_{-2.96}$| (2.6) |

| J012711.91 − 055016.45 | 0.6839 | 90.1 | |$10.77^{+0.11}_{-0.18}$| | −20.90 ± 0.10 | 1.73 ± 0.23 | |$9.91_{-2.94}^{+4.44}$| (1.1) | ||

| 7 | J014258.83 + 094942.43 | J014258.56 + 094942.20 | 0.7860 | 30.0 | |$12.01^{+0.12}_{-0.14}$| | −21.68 ± 0.09 | <1.10 | – (<0.4) |

| 8 | J025607.25 + 011038.56 | J025607.10 + 011039.80 | 0.7244 | 18.4 | |$11.04^{+0.14}_{-0.12}$| | −21.26 ± 0.10 | 1.46 ± 0.28 | |$36.18^{+44.52}_{-16.68}$| (1.5) |

| 9 | J090805.76 + 072739.90 | J090805.91 + 072740.58 | 0.6127 | 16.5 | |$10.73^{+0.13}_{-0.14}$| | −20.57 ± 0.10 | 2.53 ± 0.33 | |$15.61^{+12.78}_{-7.19}$| (1.3) |

| 10 | J095619.49 + 001800.34 | J095619.41 + 001802.00 | 0.7829 | 15.6 | |$10.72^{+0.14}_{-0.16}$| | −21.06 ± 0.13 | 6.89 ± 0.52 | |$14.42^{+20.12}_{-7.00}$| (16) |

| 11 | J104642.70 + 045731.96⋆ | J104642.62 + 045731.84 | 0.7848 | 8.9 | – | – | 0.88 ± 0.27 | – (1.6) |

| 12 | J120139.57 + 071338.24 | J120139.41 + 071342.84 | 0.6854 | 36.3 | |$10.98^{+0.14}_{-0.11}$| | −21.43 ± 0.10 | 1.80 ± 0.37 | |$42.97^{+45.06}_{-24.86}$| (1.2) |

| J120139.77 + 071333.28 | 0.6842 | 41.3 | |$11.42^{+0.13}_{-0.11}$| | −21.50 ± 0.09 | 2.91 ± 0.50 | |$82.69_{-24.86}^{+85.06}$| (1.7) | ||

| 13 | J133653.73 + 092221.23 | J133653.80 + 092217.96 | 0.7059 | 24.6 | |$10.47^{+0.16}_{-0.20}$| | −20.47 ± 0.14 | 3.05 ± 0.30 | |$6.07^{+4.73}_{-2.10}$| (2.1) |

| 14 | J140017.69 − 014902.40⋆ | – | 0.7933 | ≤8 | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | J141930.09 + 034643.73 | J141930.39 + 034639.86 | 0.7252 | 42.8 | |$10.97^{+0.16}_{-0.17}$| | −21.51 ± 0.12 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | |$23.29^{+17.46}_{-9.22}$| (2.7) |

| 16 | J144936.18 − 011650.46 | J144936.20 − 011643.58 | 0.6618 | 48.1 | |$10.74^{+.13}_{-0.08}$| | −21.05 ± 0.10 | 4.73 ± 0.43 | |$21.06^{+56.17}_{-10.87}$| (3.0) |

| 17 | J145108.53 − 013833.06 | J145108.24 − 013840.64 | 0.7414 | 64.1 | |$11.44^{+0.07}_{-0.10}$| | −21.94 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.24 | |$34.44^{+9.42}_{-9.25}$| (3.5) |

| 18 | J235639.31 − 040614.47⋆ | J235639.27 − 040413.80 | 0.7699 | 6.24 | – | – | 5.49 ± 0.43 | – (3.9) |

Finally, for all the spectroscopically confirmed redshifts, we compare the photometric redshift and spectroscopic redshift (see Fig. C2 of Appendix C). We find that the two match well within 2σ uncertainty.

4.2 Properties of USMg ii host galaxies

Having identified the host galaxies of USMg ii absorbers, we estimate their properties, such as the stellar mass (M*), rest-frame absolute B-band magnitude (MB), and the ongoing star formation rate (SFR) using the available photometric and spectroscopic data and the spectral energy distribution (SED) modelling. As in Guha et al. (2022), we use the freely accessible python tool Bayesian Analysis of Galaxies for Physical Inference and Parameter EStimation (BAGPIPES; Carnall et al. 2018). BAGPIPES takes into account Bruzual & Charlot (2003) stellar population models, which were built assuming the Kroupa & Boily (2002) initial mass function (IMF) and most recently revised by Chevallard & Charlot (2016) to incorporate the MILES stellar spectrum library and an updated stellar evolutionary track (Marigo et al. 2013). The interstellar dust is assumed to follow Calzetti (1997) dust model.

During the fit, we keep the redshifts of the USMg ii host galaxies fixed to their spectroscopic redshifts. Although BAGPIPES can simultaneously fit photometric and spectroscopic data, we only use the DESI-LIS three broad-band photometric measurements to fit the SED as the SNR of individual pixels for the continuum regions in the spectra of most of the USMg ii host galaxies is quite poor (SNR < 3). We also assume that all the stars in the galaxy have the same metallicity and use a flat prior in the range 0.01Z⊙−2.5Z⊙. We parametrize the star formation histories with an exponential model (Carnall et al. 2019). We choose a uniform prior to the logarithm of the stellar mass in the range 0 ≤ log (M⋆/M⊙) ≤ 13. However, note that the parametric models impose strong priors on physical parameters and may bias the inferred galaxy properties. Although the stellar mass is less sensitive to such effects (typical offset of 0.1 dex from the true value), the offset for SFR can be as large as 0.3 dex (Carnall et al. 2019). The derived parameters for each galaxy are listed in Table 3.

Note galaxy properties could not be measured for four USMg ii systems as their host galaxy image is blended with the quasar image. For the same reason, we could measure the galaxy parameters only for 26 out of the 36 nearest host galaxies in our combined USMg ii sample. To enable easy comparison, we have also measured all these parameters for host galaxies in the MAGIICAT sample using the same technique (see Guha et al. 2022 for details).

4.2.1 [O ii] luminosity

As mentioned earlier, except for two cases, we detected [O ii] nebular emission from USMg ii host galaxies in our present sample. To obtain the spectroscopic redshifts, we fit the [O ii] emission line using a pair of Gaussian functions having the same redshifts and velocity widths with the centroids of the two Gaussian functions separated by the ratio of the rest wavelengths of the [O ii] |$\lambda \lambda \, 3729,\, 3727$| lines. While fitting, the amplitude ratio of these two Gaussian functions is allowed to vary between 0.3 and 1.5 (Osterbrock & Ferland 2006). In principle, this flux ratio can be used to constrain the electron density. However, due to the poor velocity resolution of the SALT spectra, the uncertainty in this ratio is large, which prevents us from constraining the electron density accurately.

The [O ii] line fluxes (combined flux of the doublet) obtained from simple integration over the line profile are given in column 8 of Table 3. The [O ii] nebular line fluxes are then converted to the [O ii] line luminosities (|$L_{[O\, {\small II}]}$|) based on their redshifts and the assumed background cosmology. Note that the measurements of [O ii] luminosity are affected by two factors – the slit-loss and the dust attenuation. To correct for the slit-loss, we assume that the slit-loss is independent of the observed wavelength. Thus, we scale the observed spectra to match the synthetic spectra obtained from the SED fitting of available photometric points using the least square minimization method. We then multiply this scale factor with |$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$| to correct for the slit-loss. However, to estimate the dust content in these galaxies, we would need either at least two H i Balmer lines in emission or good-quality continuum spectra of these galaxies with sufficient SNR. As for all the cases, we have neither, so we do not correct for dust attenuation.

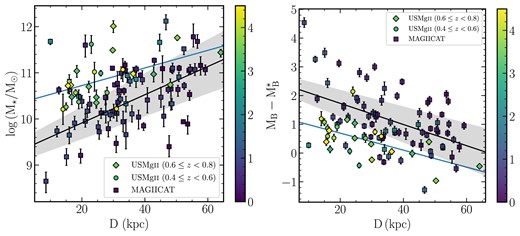

In Fig. 2, we show the scatter plot of W2796 versus the |$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$| of the associated Mg ii host galaxies. To account for the redshift evolution, we have scaled the |$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$| with respect to the characteristics [O ii] line luminosities (|$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$|, Comparat et al. 2016) at the host galaxy redshifts. The orange, green, purple, and blue points correspond to the Mg ii host galaxies from the GOTOQs (Joshi et al. 2017), MAGG survey (Dutta et al. 2020), MEGAFLOW survey (Schroetter et al. 2019), and the USMg ii host galaxies, respectively. The |$L_{[{\text O}\, {\small II}]}$| for the USMg ii host galaxies varies from |$0.05L_{[{\text O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$| to |$2.37L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$| with a median value of |$0.37L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$|. Using the lowest [O ii] line luminosity as the detection threshold (i.e. |$L_{\rm min} = 0.05L^\star _{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$|) and the [O ii] line luminosity function (Comparat et al. 2016) at z ∼ 0.6, we find that the total number of expected super-|$L^{\star }_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$| galaxies for a random population of galaxies are only about 3 per cent implying only one super-|$L^\star _{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$| galaxies among the detected USMg ii host galaxies. The expected median line luminosity for the random population of galaxies (at z ∼ 0.6) is |$\sim 0.1L^\star _{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$|. For our USMg ii sample, however, we have three super-|$L^{\star }_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$| galaxies and the median line luminosity (|$0.37L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$|) is also significantly high, even without correcting for dust extinction.

![Scatter plot of W2796 against the [O ii] line luminosity ($L_{[{\rm O}{\small II}]}$) of the associated Mg ii host galaxies. To correct for redshift evolution, we have scaled the $L_{[{\rm O}{\small II}]}$ according to the characteristic [O ii] line luminosity ($L_{[{\rm O}{\small II}]}^\star$) at that redshift. The orange, green, purple, and blue points (diamond/circle) correspond to the Mg ii host galaxies from the GOTOQs (Joshi et al. 2017), MAGG survey (Dutta et al. 2020), MEGAFLOW survey (Schroetter et al. 2019), and the USMg ii host galaxies (high redshift/low redshift), respectively. The horizontal and vertical black dashed lines correspond to the $W_{2796}^{cut}$ of USMg ii host galaxies and $L_{[{\rm O}{\small II}]}^\star$ galaxies, respectively.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/mnras/527/3/10.1093_mnras_stad3489/1/m_stad3489fig2.jpeg?Expires=1750457194&Signature=HNMXJrii6r8XR20rWm0pKhEBDmk7eEkHlysRl7bnbSCe4IHWxgcYXGZ0tUOjYaSjyUyQtjd-0ZQexfLLZoM24WBfugu2-lWW6ExQP5VwEeRTQEfaRayEq0pWhuoJiZmkzYYR1dCflDF0NIj612ksagQLyJ4wuHXUdkNnyj4Si4zzvJYEjsKx-NyE209dpG-5B8riPU-8a3oTQdAj1T7VrOPXwqVHJp~oP5h8fobY2KGOrrOMXJeUrnm-Oqa9imUTLZ7D2J13GSIomz6V0-qMUTb1Lg3LhKR3T6WWZsHM-yvqLjUBkFfftWtqfV-8662V2Blsk9jL9-~d7Um2BFpIdg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Scatter plot of W2796 against the [O ii] line luminosity (|$L_{[{\rm O}{\small II}]}$|) of the associated Mg ii host galaxies. To correct for redshift evolution, we have scaled the |$L_{[{\rm O}{\small II}]}$| according to the characteristic [O ii] line luminosity (|$L_{[{\rm O}{\small II}]}^\star$|) at that redshift. The orange, green, purple, and blue points (diamond/circle) correspond to the Mg ii host galaxies from the GOTOQs (Joshi et al. 2017), MAGG survey (Dutta et al. 2020), MEGAFLOW survey (Schroetter et al. 2019), and the USMg ii host galaxies (high redshift/low redshift), respectively. The horizontal and vertical black dashed lines correspond to the |$W_{2796}^{cut}$| of USMg ii host galaxies and |$L_{[{\rm O}{\small II}]}^\star$| galaxies, respectively.

Out of all the GOTOQs, only |$\sim 5~{{\ \rm per\ cent}}$| are super-|$L^\star _{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$| galaxies. If we restrict ourselves to GOTOQs that produce USMg ii absorption, we find |$\sim 15~{{\ \rm per\ cent}}$| of them are super-|$L^\star _{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$|. Like the USMg ii galaxies, the [O ii] luminosities of GOTOQs should be taken as lower limits as they are not corrected for fiber loss and dust extinction. For the MEGAFLOW sample, out of 26 Mg ii host galaxies, only two (|$\sim 8~{{\ \rm per\ cent}}$|) are super-|$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$| galaxies. Among the 53 galaxies associated with Mg ii absorption in the MAGG sample, only two (|$\sim 4~{{\ \rm per\ cent}}$|) are super-|$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$| galaxies. In the above two samples, there are only three USMg ii systems, and none of them are found to be a super-|$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$| galaxy. Therefore, when we combine all the USMg ii absorbers in different samples, we find ∼12 ± 4 per cent of the host galaxies have super-|$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$|. This, together with the high mean luminosity found above, confirms the early finding of Guha et al. (2022) that USMg ii absorbers are preferentially hosted by galaxies having higher-|$L_{[O\, {\small II}]}$| compared to field galaxies.

A Spearman rank correlation analysis between W2796 and |$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}/L_{[{\rm O}{\small II}]}^\star$| yields a significant correlation between these two quantities (rS = 0.28 and p-value ∼10−7), which is also reported in literature (Ménard et al. 2011; Joshi et al. 2018). However, this correlation is driven by weak Mg ii absorbers. The correlation gets weaker as we restrict ourselves to the stronger Mg ii absorbers (see Guha et al. 2022 for details). For example, for W2796 > 1 Å, Spearman rank correlation analysis gives rS = 0.16 and p-value = 0.008, while for W2796 > 2 Å, we get rS = 0.05 and p-value = 0.52. It is also clear from Fig. 2 that there is no clear trend among the USMg ii absorbers between W2796 and |$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}$|.

Next, we look for any redshift evolution in the [O ii] luminosity of USMg ii host galaxies over the redshift range 0.4 ≤ z ≤ 0.8. We do not find any redshift evolution in the [O ii] luminosities of the USMg ii host galaxies with a Spearman correlation coefficient rs = 0.07 with p-value of 0.68. This is contrary to the mild evolution shown by |$L_{[{\rm O}\, {\small II}]}^\star$| over the same redshift range (Comparat et al. 2016). It will be useful to confirm this with better quality spectra after applying appropriate dust corrections.

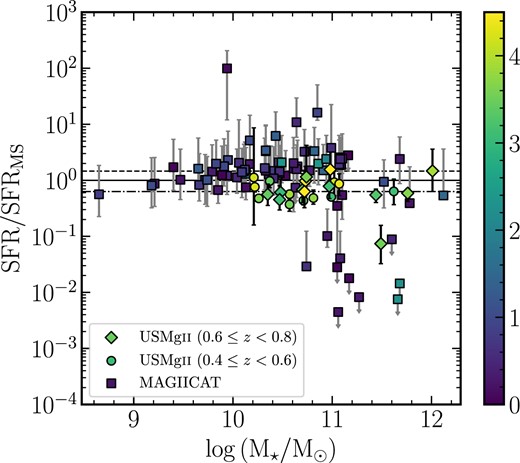

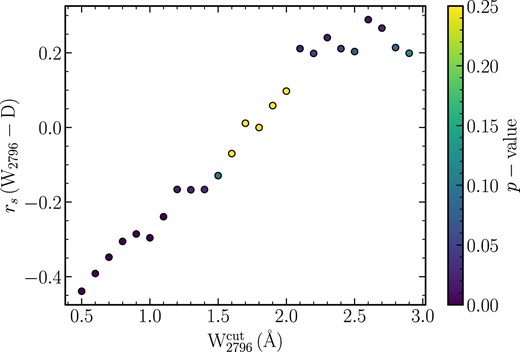

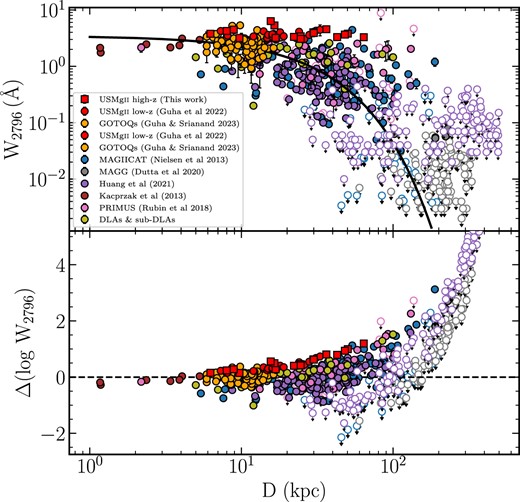

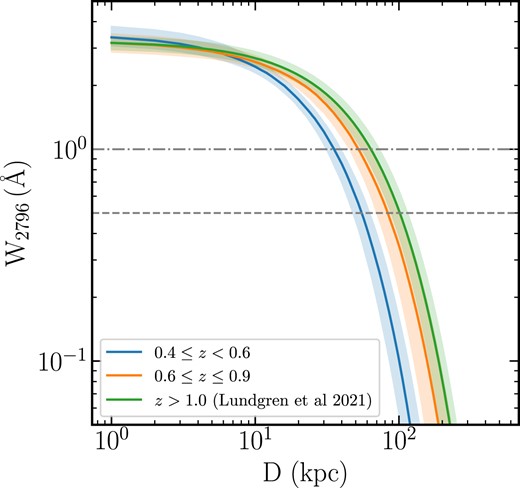

4.2.2 Star formation rates